User login

Mixing Paxlovid With Specific Immunosuppressants Risks Serious Adverse Reactions

The Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has issued a reminder to healthcare professionals regarding the potential serious adverse reactions associated with Paxlovid when administered in combination with specific immunosuppressants.

These immunosuppressants, encompassing calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and ciclosporin) and mTOR inhibitors (everolimus and sirolimus), possess a narrow safe dosage range. They are recognized for their role in diminishing the activity of the immune system and are typically prescribed for autoimmune conditions and organ transplant recipients.

The highlighted risk arises due to drug-drug interactions, which can compromise the body’s ability to eliminate these medicines effectively.

Paxlovid, also known as nirmatrelvir with ritonavir, is an antiviral medication used to treat COVID-19 in adults who do not require supplemental oxygen and who are at an increased risk of progressing to severe COVID-19. It should be administered as soon as possible after a diagnosis of COVID-19 has been made and within 5 days of symptom onset.

Conditional marketing authorization for Paxlovid was granted across the European Union (EU) on January 28, 2022, and subsequently transitioned to full marketing authorization on February 24, 2023.

Developed by Pfizer, Paxlovid exhibited an 89% reduction in the risk for hospitalization or death among unvaccinated individuals in a phase 2-3 clinical trial. This led the National Institutes of Health to prioritize Paxlovid over other COVID-19 treatments. Subsequent real-world studies have affirmed its effectiveness, even among the vaccinated.

When combining Paxlovid with tacrolimus, ciclosporin, everolimus, or sirolimus, healthcare professionals need to actively monitor their blood levels. This proactive approach is essential to mitigate the risk for drug-drug interactions and potential serious reactions. They should collaborate with a multidisciplinary team of specialists to navigate the complexities of administering these medications concurrently.

Further, Paxlovid must not be coadministered with medications highly reliant on CYP3A liver enzymes for elimination, such as the immunosuppressant voclosporin. When administered together, there is a risk for these drugs interfering with each other’s metabolism, potentially leading to altered blood levels, reduced effectiveness, or an increased risk for adverse reactions.

After a thorough review, PRAC has highlighted potential serious adverse reactions, including fatal cases, due to drug interactions between Paxlovid and specified immunosuppressants. Thus, it issued a direct healthcare professional communication (DHPC) to emphasize the recognized risk for these interactions, as previously outlined in Paxlovid’s product information.

The DHPC for Paxlovid will undergo further evaluation by EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use and, upon adoption, will be disseminated to healthcare professionals. The communication plan will include publication on the DHPCs page and in national registers across EU Member States.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has issued a reminder to healthcare professionals regarding the potential serious adverse reactions associated with Paxlovid when administered in combination with specific immunosuppressants.

These immunosuppressants, encompassing calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and ciclosporin) and mTOR inhibitors (everolimus and sirolimus), possess a narrow safe dosage range. They are recognized for their role in diminishing the activity of the immune system and are typically prescribed for autoimmune conditions and organ transplant recipients.

The highlighted risk arises due to drug-drug interactions, which can compromise the body’s ability to eliminate these medicines effectively.

Paxlovid, also known as nirmatrelvir with ritonavir, is an antiviral medication used to treat COVID-19 in adults who do not require supplemental oxygen and who are at an increased risk of progressing to severe COVID-19. It should be administered as soon as possible after a diagnosis of COVID-19 has been made and within 5 days of symptom onset.

Conditional marketing authorization for Paxlovid was granted across the European Union (EU) on January 28, 2022, and subsequently transitioned to full marketing authorization on February 24, 2023.

Developed by Pfizer, Paxlovid exhibited an 89% reduction in the risk for hospitalization or death among unvaccinated individuals in a phase 2-3 clinical trial. This led the National Institutes of Health to prioritize Paxlovid over other COVID-19 treatments. Subsequent real-world studies have affirmed its effectiveness, even among the vaccinated.

When combining Paxlovid with tacrolimus, ciclosporin, everolimus, or sirolimus, healthcare professionals need to actively monitor their blood levels. This proactive approach is essential to mitigate the risk for drug-drug interactions and potential serious reactions. They should collaborate with a multidisciplinary team of specialists to navigate the complexities of administering these medications concurrently.

Further, Paxlovid must not be coadministered with medications highly reliant on CYP3A liver enzymes for elimination, such as the immunosuppressant voclosporin. When administered together, there is a risk for these drugs interfering with each other’s metabolism, potentially leading to altered blood levels, reduced effectiveness, or an increased risk for adverse reactions.

After a thorough review, PRAC has highlighted potential serious adverse reactions, including fatal cases, due to drug interactions between Paxlovid and specified immunosuppressants. Thus, it issued a direct healthcare professional communication (DHPC) to emphasize the recognized risk for these interactions, as previously outlined in Paxlovid’s product information.

The DHPC for Paxlovid will undergo further evaluation by EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use and, upon adoption, will be disseminated to healthcare professionals. The communication plan will include publication on the DHPCs page and in national registers across EU Member States.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has issued a reminder to healthcare professionals regarding the potential serious adverse reactions associated with Paxlovid when administered in combination with specific immunosuppressants.

These immunosuppressants, encompassing calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and ciclosporin) and mTOR inhibitors (everolimus and sirolimus), possess a narrow safe dosage range. They are recognized for their role in diminishing the activity of the immune system and are typically prescribed for autoimmune conditions and organ transplant recipients.

The highlighted risk arises due to drug-drug interactions, which can compromise the body’s ability to eliminate these medicines effectively.

Paxlovid, also known as nirmatrelvir with ritonavir, is an antiviral medication used to treat COVID-19 in adults who do not require supplemental oxygen and who are at an increased risk of progressing to severe COVID-19. It should be administered as soon as possible after a diagnosis of COVID-19 has been made and within 5 days of symptom onset.

Conditional marketing authorization for Paxlovid was granted across the European Union (EU) on January 28, 2022, and subsequently transitioned to full marketing authorization on February 24, 2023.

Developed by Pfizer, Paxlovid exhibited an 89% reduction in the risk for hospitalization or death among unvaccinated individuals in a phase 2-3 clinical trial. This led the National Institutes of Health to prioritize Paxlovid over other COVID-19 treatments. Subsequent real-world studies have affirmed its effectiveness, even among the vaccinated.

When combining Paxlovid with tacrolimus, ciclosporin, everolimus, or sirolimus, healthcare professionals need to actively monitor their blood levels. This proactive approach is essential to mitigate the risk for drug-drug interactions and potential serious reactions. They should collaborate with a multidisciplinary team of specialists to navigate the complexities of administering these medications concurrently.

Further, Paxlovid must not be coadministered with medications highly reliant on CYP3A liver enzymes for elimination, such as the immunosuppressant voclosporin. When administered together, there is a risk for these drugs interfering with each other’s metabolism, potentially leading to altered blood levels, reduced effectiveness, or an increased risk for adverse reactions.

After a thorough review, PRAC has highlighted potential serious adverse reactions, including fatal cases, due to drug interactions between Paxlovid and specified immunosuppressants. Thus, it issued a direct healthcare professional communication (DHPC) to emphasize the recognized risk for these interactions, as previously outlined in Paxlovid’s product information.

The DHPC for Paxlovid will undergo further evaluation by EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use and, upon adoption, will be disseminated to healthcare professionals. The communication plan will include publication on the DHPCs page and in national registers across EU Member States.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

My Kidney Is Fine, Can’t You Cystatin C?

Clinicians usually measure renal function by using surrogate markers because directly measuring glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is not routinely feasible in a clinical setting.1,2 Creatinine (Cr) and cystatin C (CysC) are the 2 main surrogate molecules used to estimate GFR.3

Creatine is a molecule nonenzymatically converted into Cr, weighing only 113 Da in skeletal muscles.4 It is then filtered at the glomeruli and secreted at the proximal tubules of the kidneys. However, serum Cr (sCr) levels are affected by several factors, including age, biological sex, liver function, diet, and muscle mass.5 Historically, sCr levels also are affected by race.5 In an early study of factors affecting accurate GFR, researchers reported that self-identified African American patients had a 16% higher GFR than those who did not when using Cr.6 Despite this, the inclusion of Cr on a basic metabolic panel has allowed automatic reporting of an estimated GFR using sCr (eGFRCr) to be readily available.7

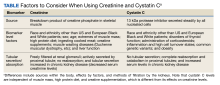

In comparison to Cr, CysC is an endogenous protein weighing 13 kDa produced by all nucleated cells.8,9 CysC is filtered by the kidney at the glomeruli and completely reabsorbed and catabolized by epithelial cells at the proximal tubule.9 Since production is not dependent on skeletal muscle, there are fewer physiological impacts on serum concentration of CysC. Levels of CysC may be elevated by factors shown in the Table.

Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rates

Multiple equations were developed to mitigate the impact of extraneous factors on the accuracy of an eGFRCr. The first widely used equation that included a variable adjustment for race was the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study, presented in 2006.10 The equation increased the accuracy of eGFRCr further by adjusting for sex and age. It was followed by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation in 2009, which was more accurate at higher GFR levels.11

CysC was simultaneously studied as an alternative to Cr with multiple equation iterations shown to be viable in various populations as early as 2003.12-15 However, it was not until 2012 that an equation for the use of CysC was offered for widespread use as an alternative to Cr alongside further refinement of the CKD-EPI equation for Cr.16 A new formula was presented in 2021 to use both sCr and serum CysC levels to obtain a more accurate estimation of GFR.17 Research continues its effort to accurately estimate GFR for diagnosing kidney disease and assessing comorbidities relating to decreased kidney function.3

All historical equations attempted to mitigate the potential impact of race on sCr level when calculating eGFRCrby assigning a separate variable for African American patients. As an unintended adverse effect, these equations may have led to discrimination by having a different equation for African American patients.18 Moreover, these Cr-based equations remain less accurate in patients with varied muscle mass, such as older patients, bodybuilders, athletes, and individuals with varied extremes of daily protein intake.1,8,9,19Several medications can also directly affect Cr clearance, reducing its ability to act as a surrogate for kidney function.1In this case report, we discuss an African American patient with high muscle mass and protein intake who was initially diagnosed with kidney disease based on an elevated Cr and found to be misdiagnosed based on the use of CysC for a more accurate GFR estimation.

Case Presentation

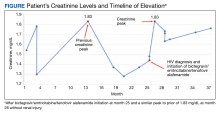

A 35-year-old African American man serving in the military and recently diagnosed with HIV was referred to a nephrology clinic for further evaluation of an acute elevation in sCr. Before treatment for HIV, a brief record review showed a baseline Cr of about 1.3 mg/dL, with an eGFRCr of 75 mL/min/1.73 m2.20 In the same month, the patient was prescribed bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, an HIV drug with nephrotoxic potential.21 The patient's total viral load remained low, and CD4 count remained > 500 after initiation of the HIV treatment. He was in his normal state of health and had no known contributory history before his HIV diagnosis. Cr readings peaked at 1.83 mg/dL after starting the HIV treatment and remained elevated to 1.73 mg/dL over the next few months, corresponding to CKD stage 3A. Because bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide is cleared by the kidneys and has a nephrotoxic profile, the clinical care team considered dosage adjustment or a medication switch given his observed elevated eGFRCr based on the CKD-EPI 2021 equation for Cr alone. It was also noted that the patient had a similar Cr spike to 1.83 mg/dL in 2018 without any identifiable renal insult or symptoms (Figure).

Diagnostic Evaluation

The primary care team ordered a renal ultrasound and referred the patient to the nephrology clinic. The nephrologist ordered the following laboratory studies: urine microalbumin to Cr ratio, basic metabolic panel (BMP), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), urinalysis, urine protein, urine Cr, parathyroid hormone level, hemoglobin A1c, complement component 3/4 panels, antinuclear and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies titers, glomerular basement membrane antibody titer, urine light chains, serum protein electrophoresis, κ/λ ratio, viral hepatitis panel, and rapid plasma reagin testing. Much of this laboratory evaluation served to rule out any secondary causes of kidney disease, including autoimmune disease, monoclonal or polyclonal gammopathies, diabetic nephropathy or glomerulosclerosis, and nephrotic or nephritic syndromes.

All laboratory studies returned within normal limits; no proteinuria was discovered on urinalysis, and no abnormalities were visualized on renal ultrasound. Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide nephrotoxicity was highest among the differential diagnoses due to the timing of Cr elevation coinciding with the initiation of the medications. The patient's CysC level was 0.85 mg/dL with a calculated eGFRCys of 125 mL/min/1.73 m2. The calculated sCR and serum cystatin C (eGFRCr-Cys) using the new 2021 equation and when adjusting for body surface area placed his eGFR at 92 mL/min/1.73 m2.20

The patient’s eGFRCysreassured the care team that the patient’s renal function was not acutely or chronically impacted by bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, resulting in avoidance of unnecessary dosage adjustment or discontinuation of the HIV treatment. The patient reported a chronic habit of protein and creatine supplementation and bodybuilding, which likely further compounded the discrepancy between eGFRCr and eGFRCys and explained his previous elevation in Cr in 2018.

Follow-up

The patient underwent serial monitoring that revealed a stable Cr and unremarkable eGFR, ruling out CKD. There has been no evidence of worsening kidney disease to date, and the patient remained on his initial HIV regimen.

Discussion

This case shows the importance of using CysC as an alternative or confirmatory marker compared with sCr to estimate GFR in patients with high muscle mass and/or high creatine intake, such as many in the US Department of Defense (DoD) and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) patient populations. In the presented case, recorded Cr levels climbed from baseline Cr with the initiation of bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide. This raised the concern that HIV treatment was leading to the development of kidney damage.22

Diagnosis of kidney disease as opposed to the normal decline of eGFR with age in individuals without intrinsic CKD requires GFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 with kidney damage (proteinuria or radiological abnormalities, etc) or GFR < 135 to 140 mL/min/1.73 m2minus the patient’s age in years.23 The patient’s Cr peak at 1.83 mg/dL in 2018 led to an inappropriate diagnosis of kidney disease stage 3a based on an eGFRCr (2021 equation) of 52 mL/min/1.73 m2 when not corrected for body surface area.20 However, using the new 2021 equation using both Cr and CysC, the patient’s eGFRCr-Cyswas 92 mL/min/1.73 m2 after a correction for body surface area.

The 2009 CKD-EPI recommended the calculation of eGFR based on SCr concentration using age, sex, and race while the 2021 CKD-EPI recommended the exclusion of race.3 Both equations are less accurate in African American patients, individuals taking medications that interfere with Cr secretion and assay, and patients taking creatine supplements, high daily protein intake, or with high muscle mass.7 These settings result in a decreased eGFRCr without corresponding eGFRCys changes. Using SCr and CysC together, the eGFRCr-Cys yields improved concordance to measured GFR across race groups compared to GFR estimation based on Cr alone, which can avoid unnecessary expensive diagnostic workup, inappropriate kidney disease diagnosis, incorrect dosing of drugs, and accurately represent the military readiness of patients. Interestingly, in African American patients with recently diagnosed HIV, CKD-EPI using both Cr and CysC without race inclusion led to only a 2.9% overestimation of GFR and was the only equation with no statistically significant bias compared with measured GFR.24

A March 2023 case involving an otherwise healthy 26-year-old male active-duty US Navy member with a history of excessive protein supplement intake and intense exercise < 24 hours before laboratory work was diagnosed with CKD after a measured Cr of 16 mg/dL and an eGFRCr of 4 mL/min/1.73 m2 without any other evidence of kidney disease. His CysC remained within normal limits, resulting in a normal eGFRCys of 121 mL/min/1.73 m2, indicating no CKD. His Cr and eGFR recovered 10 days after his clinic visit and cessation of his supplement intake. These findings may not be uncommon given that 65% of active-duty military use protein supplements and 38% use other performance-enhancing supplements, such as creatine, according to a study.25

Unfortunately, the BMP/CMP traditionally used at VA centers use the eGFRCr equation, and it is unknown how many primary care practitioners recognize the limitations of these metabolic panels on accurate estimation of kidney function. However, in 2022 an expert panel including VA physicians recommended the immediate use of eGFRCr-Cys or eGFRCys for confirmatory testing and potentially screening of CKD.26 A small number of VAs have since adopted this recommendation, which should lead to fewer misdiagnoses among US military members as clinicians should now have access to more accurate measurements of GFR.

The VA spends about $18 billion (excluding dialysis) for care for 1.1 to 2.5 million VA patients with CKD.27 The majority of these diagnoses were undoubtedly made using the eGFRCr equation, raising the question of how many may be misdiagnosed. Assessment with CysC is currently relatively expensive, but it will likely become more affordable as the use of CysC as a confirmatory test increases.5 The cost of a sCr test is about $2.50, while CysC costs about $10.60, with variation from laboratory to laboratory.28 By comparison, a renal ultrasound costs $99 to $140 for uninsured patients.29 Furthermore, the cost of CysC testing is likely to trend downward as more facilities adopt the use of CysC measurements, which can be run on the same analytical equipment currently used for Cr measurements. Currently, most laboratories do not have established assays to use in-house and thus require CysC to be sent out to a laboratory, which increases result time and makes Cr a more attractive option. As more laboratories adopt assays for CysC, the cost of reagents will further decrease.

Given such considerations, confirmation testing of kidney function with CysC in specific patient populations with decreased eGFRCr without other features of CKD can offer great medical and financial benefits. A 2023 KDIGO report noted that many individuals may be mistakenly diagnosed with CKD when using eGFRCr.3 KDIGO noted that a 2013 meta-analysis of 90,000 individuals found that with a Cr-based eGFR of 45 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2 (42%) had a CysC-based eGFR of ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. An eGFRCr of 45 to 59 represents 54% of all patients with CKD, amounting to millions of people (including current and former military personnel).3,29-31 Correcting a misdiagnosis of CKD would bring significant relief to patients and save millions in health care spending.

Conclusions

In patients who meet CKD criteria using eGFRCr but without other features of CKD, we recommend using confirmatory CysC levels and the eGFRCr-Cys equation. This will align care with the KDIGO guidelines and could be a cost-effective step toward improving military patient care. Further work in this area should focus on determining the knowledge gaps in primary care practitioners’ understanding of the limits of eGFRCr, the potential mitigation of concomitant CysC testing in equivocal CKD cases, and the cost-effectiveness and increased utilization of CysC.

1. Gabriel R. Time to scrap creatinine clearance? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293(6555):1119-1120. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6555.1119

2. Swan SK. The search continues—an ideal marker of GFR. Clin Chem. 1997;43(6):913-914.doi:10.1093/clinchem/43.6.913 3. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(1).

4. Wyss M, Kaddurah-Daouk R. Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(3):1107-1213. doi:10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1107

5. Ferguson TW, Komenda P, Tangri N. Cystatin C as a biomarker for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24(3):295-300. doi:10.1097/mnh.0000000000000115

6. Levey AS, Titan SM, Powe NR, Coresh J, Inker LA. Kidney disease, race, and GFR estimation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(8):1203-1212. doi:10.2215/cjn.12791019

7. Shlipak MG, Tummalapalli SL, Boulware LE, et al; Conference Participants. The case for early identification and intervention of chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2021;99(1):34-47. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.012

8. O’Riordan SE, Webb MC, Stowe HJ, et al. Cystatin C improves the detection of mild renal dysfunction in older patients. Ann Clin Biochem. 2003;40(pt 6):648-655. doi:10.1258/000456303770367243

9. Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, et al. Factors other than glomerular filtration rate affect serum cystatin C levels. Kidney Int. 2009;75(6):652-660. doi:10.1038/ki.2008.638

10. Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):247-254. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004

11. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604-612. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006

12. Pöge U, Gerhardt T, Stoffel-Wagner B, Klehr HU, Sauerbruch T, Woitas RP. Calculation of glomerular filtration rate based on cystatin C in cirrhotic patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(3):660-664. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfi305

13. Larsson A, Malm J, Grubb A, Hansson LO. Calculation of glomerular filtration rate expressed in mL/min from plasma cystatin C values in mg/L. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2004;64(1):25-30. doi:10.1080/00365510410003723.

14. Macisaac RJ, Tsalamandris C, Thomas MC, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate in diabetes: a comparison of cystatin-C- and creatinine-based methods. Diabetologia. 2006;49(7):1686-1689. doi:10.1007/s00125-006-0275-7

15. Rule AD, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Bergert J, Larson TS. Glomerular filtration rate estimated by cystatin C among different clinical presentations. Kidney Int. 2006;69(2):399-405. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5000073

16. Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Investigators. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):20-29. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1114248

17. Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Ärnlöv J, et al; CKD Prognosis Consortium. Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(10):932-943. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214234

18. Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. New creatinine- and cystatin C–Based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1737-1749. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2102953

19. Oterdoom LH, Gansevoort RT, Schouten JP, de Jong PE, Gans ROB, Bakker SJL. Urinary creatinine excretion, an indirect measure of muscle mass, is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the general population. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207(2):534-540. doi.10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.05.010

20. National Kidney Foundation Inc. eGFR calculator. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/gfr_calculator

21. Ueaphongsukkit T, Gatechompol S, Avihingsanon A, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide nephrotoxicity: a case report and literature review. AIDS Res Ther. 2021;18(1):53. doi:10.1186/s12981-021-00380-w

22. D’Agati V, Appel GB. Renal pathology of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Semin Nephrol. 1998;18(4):406-421.

23. Glassock RJ, Winearls C. Ageing and the glomerular filtration rate: truths and consequences. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2009;120:419-428.

24. Seape T, Gounden V, van Deventer HE, Candy GP, George JA. Cystatin C- and creatinine-based equations in the assessment of renal function in HIV-positive patients prior to commencing highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ann Clin Biochem. 2016;53(pt 1):58-66. doi:10.1177/0004563215579695

25. Tobin TW, Thurlow JS, Yuan CM. A healthy active duty soldier with an elevated serum creatinine. Mil Med. 2023;188(3-4):e866-e869. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab163

26. Delgado C, Baweja M, Crews DC, et al. A unifying approach for GFR estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN Task Force on Reassessing the Inclusion of Race in Diagnosing Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79(2):268-288.e1. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.08.003

27. Saran R, Pearson A, Tilea A, et al; VA-REINS Steering Committee; VA Advisory Board. Burden and cost of caring for us veterans with CKD: initial findings from the VA Renal Information System (VA-REINS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(3):397-405. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.07.013

28. Zoler ML. Nephrologists make the case for cystatin C-based eGFR. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/951335#vp_2

29. Versaw N. How much does an ultrasound cost? Updated February 2022. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.compare.com/health/healthcare-resources/how-much-does-an-ultrasound-cost

30. Levey AS, Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9811):165-180. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60178-5

31. Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Ärnlöv J, et al; CKD Prognosis Consortium. Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(10):932-943. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214234

Clinicians usually measure renal function by using surrogate markers because directly measuring glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is not routinely feasible in a clinical setting.1,2 Creatinine (Cr) and cystatin C (CysC) are the 2 main surrogate molecules used to estimate GFR.3

Creatine is a molecule nonenzymatically converted into Cr, weighing only 113 Da in skeletal muscles.4 It is then filtered at the glomeruli and secreted at the proximal tubules of the kidneys. However, serum Cr (sCr) levels are affected by several factors, including age, biological sex, liver function, diet, and muscle mass.5 Historically, sCr levels also are affected by race.5 In an early study of factors affecting accurate GFR, researchers reported that self-identified African American patients had a 16% higher GFR than those who did not when using Cr.6 Despite this, the inclusion of Cr on a basic metabolic panel has allowed automatic reporting of an estimated GFR using sCr (eGFRCr) to be readily available.7

In comparison to Cr, CysC is an endogenous protein weighing 13 kDa produced by all nucleated cells.8,9 CysC is filtered by the kidney at the glomeruli and completely reabsorbed and catabolized by epithelial cells at the proximal tubule.9 Since production is not dependent on skeletal muscle, there are fewer physiological impacts on serum concentration of CysC. Levels of CysC may be elevated by factors shown in the Table.

Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rates

Multiple equations were developed to mitigate the impact of extraneous factors on the accuracy of an eGFRCr. The first widely used equation that included a variable adjustment for race was the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study, presented in 2006.10 The equation increased the accuracy of eGFRCr further by adjusting for sex and age. It was followed by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation in 2009, which was more accurate at higher GFR levels.11

CysC was simultaneously studied as an alternative to Cr with multiple equation iterations shown to be viable in various populations as early as 2003.12-15 However, it was not until 2012 that an equation for the use of CysC was offered for widespread use as an alternative to Cr alongside further refinement of the CKD-EPI equation for Cr.16 A new formula was presented in 2021 to use both sCr and serum CysC levels to obtain a more accurate estimation of GFR.17 Research continues its effort to accurately estimate GFR for diagnosing kidney disease and assessing comorbidities relating to decreased kidney function.3

All historical equations attempted to mitigate the potential impact of race on sCr level when calculating eGFRCrby assigning a separate variable for African American patients. As an unintended adverse effect, these equations may have led to discrimination by having a different equation for African American patients.18 Moreover, these Cr-based equations remain less accurate in patients with varied muscle mass, such as older patients, bodybuilders, athletes, and individuals with varied extremes of daily protein intake.1,8,9,19Several medications can also directly affect Cr clearance, reducing its ability to act as a surrogate for kidney function.1In this case report, we discuss an African American patient with high muscle mass and protein intake who was initially diagnosed with kidney disease based on an elevated Cr and found to be misdiagnosed based on the use of CysC for a more accurate GFR estimation.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old African American man serving in the military and recently diagnosed with HIV was referred to a nephrology clinic for further evaluation of an acute elevation in sCr. Before treatment for HIV, a brief record review showed a baseline Cr of about 1.3 mg/dL, with an eGFRCr of 75 mL/min/1.73 m2.20 In the same month, the patient was prescribed bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, an HIV drug with nephrotoxic potential.21 The patient's total viral load remained low, and CD4 count remained > 500 after initiation of the HIV treatment. He was in his normal state of health and had no known contributory history before his HIV diagnosis. Cr readings peaked at 1.83 mg/dL after starting the HIV treatment and remained elevated to 1.73 mg/dL over the next few months, corresponding to CKD stage 3A. Because bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide is cleared by the kidneys and has a nephrotoxic profile, the clinical care team considered dosage adjustment or a medication switch given his observed elevated eGFRCr based on the CKD-EPI 2021 equation for Cr alone. It was also noted that the patient had a similar Cr spike to 1.83 mg/dL in 2018 without any identifiable renal insult or symptoms (Figure).

Diagnostic Evaluation

The primary care team ordered a renal ultrasound and referred the patient to the nephrology clinic. The nephrologist ordered the following laboratory studies: urine microalbumin to Cr ratio, basic metabolic panel (BMP), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), urinalysis, urine protein, urine Cr, parathyroid hormone level, hemoglobin A1c, complement component 3/4 panels, antinuclear and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies titers, glomerular basement membrane antibody titer, urine light chains, serum protein electrophoresis, κ/λ ratio, viral hepatitis panel, and rapid plasma reagin testing. Much of this laboratory evaluation served to rule out any secondary causes of kidney disease, including autoimmune disease, monoclonal or polyclonal gammopathies, diabetic nephropathy or glomerulosclerosis, and nephrotic or nephritic syndromes.

All laboratory studies returned within normal limits; no proteinuria was discovered on urinalysis, and no abnormalities were visualized on renal ultrasound. Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide nephrotoxicity was highest among the differential diagnoses due to the timing of Cr elevation coinciding with the initiation of the medications. The patient's CysC level was 0.85 mg/dL with a calculated eGFRCys of 125 mL/min/1.73 m2. The calculated sCR and serum cystatin C (eGFRCr-Cys) using the new 2021 equation and when adjusting for body surface area placed his eGFR at 92 mL/min/1.73 m2.20

The patient’s eGFRCysreassured the care team that the patient’s renal function was not acutely or chronically impacted by bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, resulting in avoidance of unnecessary dosage adjustment or discontinuation of the HIV treatment. The patient reported a chronic habit of protein and creatine supplementation and bodybuilding, which likely further compounded the discrepancy between eGFRCr and eGFRCys and explained his previous elevation in Cr in 2018.

Follow-up

The patient underwent serial monitoring that revealed a stable Cr and unremarkable eGFR, ruling out CKD. There has been no evidence of worsening kidney disease to date, and the patient remained on his initial HIV regimen.

Discussion

This case shows the importance of using CysC as an alternative or confirmatory marker compared with sCr to estimate GFR in patients with high muscle mass and/or high creatine intake, such as many in the US Department of Defense (DoD) and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) patient populations. In the presented case, recorded Cr levels climbed from baseline Cr with the initiation of bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide. This raised the concern that HIV treatment was leading to the development of kidney damage.22

Diagnosis of kidney disease as opposed to the normal decline of eGFR with age in individuals without intrinsic CKD requires GFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 with kidney damage (proteinuria or radiological abnormalities, etc) or GFR < 135 to 140 mL/min/1.73 m2minus the patient’s age in years.23 The patient’s Cr peak at 1.83 mg/dL in 2018 led to an inappropriate diagnosis of kidney disease stage 3a based on an eGFRCr (2021 equation) of 52 mL/min/1.73 m2 when not corrected for body surface area.20 However, using the new 2021 equation using both Cr and CysC, the patient’s eGFRCr-Cyswas 92 mL/min/1.73 m2 after a correction for body surface area.

The 2009 CKD-EPI recommended the calculation of eGFR based on SCr concentration using age, sex, and race while the 2021 CKD-EPI recommended the exclusion of race.3 Both equations are less accurate in African American patients, individuals taking medications that interfere with Cr secretion and assay, and patients taking creatine supplements, high daily protein intake, or with high muscle mass.7 These settings result in a decreased eGFRCr without corresponding eGFRCys changes. Using SCr and CysC together, the eGFRCr-Cys yields improved concordance to measured GFR across race groups compared to GFR estimation based on Cr alone, which can avoid unnecessary expensive diagnostic workup, inappropriate kidney disease diagnosis, incorrect dosing of drugs, and accurately represent the military readiness of patients. Interestingly, in African American patients with recently diagnosed HIV, CKD-EPI using both Cr and CysC without race inclusion led to only a 2.9% overestimation of GFR and was the only equation with no statistically significant bias compared with measured GFR.24

A March 2023 case involving an otherwise healthy 26-year-old male active-duty US Navy member with a history of excessive protein supplement intake and intense exercise < 24 hours before laboratory work was diagnosed with CKD after a measured Cr of 16 mg/dL and an eGFRCr of 4 mL/min/1.73 m2 without any other evidence of kidney disease. His CysC remained within normal limits, resulting in a normal eGFRCys of 121 mL/min/1.73 m2, indicating no CKD. His Cr and eGFR recovered 10 days after his clinic visit and cessation of his supplement intake. These findings may not be uncommon given that 65% of active-duty military use protein supplements and 38% use other performance-enhancing supplements, such as creatine, according to a study.25

Unfortunately, the BMP/CMP traditionally used at VA centers use the eGFRCr equation, and it is unknown how many primary care practitioners recognize the limitations of these metabolic panels on accurate estimation of kidney function. However, in 2022 an expert panel including VA physicians recommended the immediate use of eGFRCr-Cys or eGFRCys for confirmatory testing and potentially screening of CKD.26 A small number of VAs have since adopted this recommendation, which should lead to fewer misdiagnoses among US military members as clinicians should now have access to more accurate measurements of GFR.

The VA spends about $18 billion (excluding dialysis) for care for 1.1 to 2.5 million VA patients with CKD.27 The majority of these diagnoses were undoubtedly made using the eGFRCr equation, raising the question of how many may be misdiagnosed. Assessment with CysC is currently relatively expensive, but it will likely become more affordable as the use of CysC as a confirmatory test increases.5 The cost of a sCr test is about $2.50, while CysC costs about $10.60, with variation from laboratory to laboratory.28 By comparison, a renal ultrasound costs $99 to $140 for uninsured patients.29 Furthermore, the cost of CysC testing is likely to trend downward as more facilities adopt the use of CysC measurements, which can be run on the same analytical equipment currently used for Cr measurements. Currently, most laboratories do not have established assays to use in-house and thus require CysC to be sent out to a laboratory, which increases result time and makes Cr a more attractive option. As more laboratories adopt assays for CysC, the cost of reagents will further decrease.

Given such considerations, confirmation testing of kidney function with CysC in specific patient populations with decreased eGFRCr without other features of CKD can offer great medical and financial benefits. A 2023 KDIGO report noted that many individuals may be mistakenly diagnosed with CKD when using eGFRCr.3 KDIGO noted that a 2013 meta-analysis of 90,000 individuals found that with a Cr-based eGFR of 45 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2 (42%) had a CysC-based eGFR of ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. An eGFRCr of 45 to 59 represents 54% of all patients with CKD, amounting to millions of people (including current and former military personnel).3,29-31 Correcting a misdiagnosis of CKD would bring significant relief to patients and save millions in health care spending.

Conclusions

In patients who meet CKD criteria using eGFRCr but without other features of CKD, we recommend using confirmatory CysC levels and the eGFRCr-Cys equation. This will align care with the KDIGO guidelines and could be a cost-effective step toward improving military patient care. Further work in this area should focus on determining the knowledge gaps in primary care practitioners’ understanding of the limits of eGFRCr, the potential mitigation of concomitant CysC testing in equivocal CKD cases, and the cost-effectiveness and increased utilization of CysC.

Clinicians usually measure renal function by using surrogate markers because directly measuring glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is not routinely feasible in a clinical setting.1,2 Creatinine (Cr) and cystatin C (CysC) are the 2 main surrogate molecules used to estimate GFR.3

Creatine is a molecule nonenzymatically converted into Cr, weighing only 113 Da in skeletal muscles.4 It is then filtered at the glomeruli and secreted at the proximal tubules of the kidneys. However, serum Cr (sCr) levels are affected by several factors, including age, biological sex, liver function, diet, and muscle mass.5 Historically, sCr levels also are affected by race.5 In an early study of factors affecting accurate GFR, researchers reported that self-identified African American patients had a 16% higher GFR than those who did not when using Cr.6 Despite this, the inclusion of Cr on a basic metabolic panel has allowed automatic reporting of an estimated GFR using sCr (eGFRCr) to be readily available.7

In comparison to Cr, CysC is an endogenous protein weighing 13 kDa produced by all nucleated cells.8,9 CysC is filtered by the kidney at the glomeruli and completely reabsorbed and catabolized by epithelial cells at the proximal tubule.9 Since production is not dependent on skeletal muscle, there are fewer physiological impacts on serum concentration of CysC. Levels of CysC may be elevated by factors shown in the Table.

Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rates

Multiple equations were developed to mitigate the impact of extraneous factors on the accuracy of an eGFRCr. The first widely used equation that included a variable adjustment for race was the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study, presented in 2006.10 The equation increased the accuracy of eGFRCr further by adjusting for sex and age. It was followed by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation in 2009, which was more accurate at higher GFR levels.11

CysC was simultaneously studied as an alternative to Cr with multiple equation iterations shown to be viable in various populations as early as 2003.12-15 However, it was not until 2012 that an equation for the use of CysC was offered for widespread use as an alternative to Cr alongside further refinement of the CKD-EPI equation for Cr.16 A new formula was presented in 2021 to use both sCr and serum CysC levels to obtain a more accurate estimation of GFR.17 Research continues its effort to accurately estimate GFR for diagnosing kidney disease and assessing comorbidities relating to decreased kidney function.3

All historical equations attempted to mitigate the potential impact of race on sCr level when calculating eGFRCrby assigning a separate variable for African American patients. As an unintended adverse effect, these equations may have led to discrimination by having a different equation for African American patients.18 Moreover, these Cr-based equations remain less accurate in patients with varied muscle mass, such as older patients, bodybuilders, athletes, and individuals with varied extremes of daily protein intake.1,8,9,19Several medications can also directly affect Cr clearance, reducing its ability to act as a surrogate for kidney function.1In this case report, we discuss an African American patient with high muscle mass and protein intake who was initially diagnosed with kidney disease based on an elevated Cr and found to be misdiagnosed based on the use of CysC for a more accurate GFR estimation.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old African American man serving in the military and recently diagnosed with HIV was referred to a nephrology clinic for further evaluation of an acute elevation in sCr. Before treatment for HIV, a brief record review showed a baseline Cr of about 1.3 mg/dL, with an eGFRCr of 75 mL/min/1.73 m2.20 In the same month, the patient was prescribed bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, an HIV drug with nephrotoxic potential.21 The patient's total viral load remained low, and CD4 count remained > 500 after initiation of the HIV treatment. He was in his normal state of health and had no known contributory history before his HIV diagnosis. Cr readings peaked at 1.83 mg/dL after starting the HIV treatment and remained elevated to 1.73 mg/dL over the next few months, corresponding to CKD stage 3A. Because bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide is cleared by the kidneys and has a nephrotoxic profile, the clinical care team considered dosage adjustment or a medication switch given his observed elevated eGFRCr based on the CKD-EPI 2021 equation for Cr alone. It was also noted that the patient had a similar Cr spike to 1.83 mg/dL in 2018 without any identifiable renal insult or symptoms (Figure).

Diagnostic Evaluation

The primary care team ordered a renal ultrasound and referred the patient to the nephrology clinic. The nephrologist ordered the following laboratory studies: urine microalbumin to Cr ratio, basic metabolic panel (BMP), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), urinalysis, urine protein, urine Cr, parathyroid hormone level, hemoglobin A1c, complement component 3/4 panels, antinuclear and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies titers, glomerular basement membrane antibody titer, urine light chains, serum protein electrophoresis, κ/λ ratio, viral hepatitis panel, and rapid plasma reagin testing. Much of this laboratory evaluation served to rule out any secondary causes of kidney disease, including autoimmune disease, monoclonal or polyclonal gammopathies, diabetic nephropathy or glomerulosclerosis, and nephrotic or nephritic syndromes.

All laboratory studies returned within normal limits; no proteinuria was discovered on urinalysis, and no abnormalities were visualized on renal ultrasound. Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide nephrotoxicity was highest among the differential diagnoses due to the timing of Cr elevation coinciding with the initiation of the medications. The patient's CysC level was 0.85 mg/dL with a calculated eGFRCys of 125 mL/min/1.73 m2. The calculated sCR and serum cystatin C (eGFRCr-Cys) using the new 2021 equation and when adjusting for body surface area placed his eGFR at 92 mL/min/1.73 m2.20

The patient’s eGFRCysreassured the care team that the patient’s renal function was not acutely or chronically impacted by bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, resulting in avoidance of unnecessary dosage adjustment or discontinuation of the HIV treatment. The patient reported a chronic habit of protein and creatine supplementation and bodybuilding, which likely further compounded the discrepancy between eGFRCr and eGFRCys and explained his previous elevation in Cr in 2018.

Follow-up

The patient underwent serial monitoring that revealed a stable Cr and unremarkable eGFR, ruling out CKD. There has been no evidence of worsening kidney disease to date, and the patient remained on his initial HIV regimen.

Discussion

This case shows the importance of using CysC as an alternative or confirmatory marker compared with sCr to estimate GFR in patients with high muscle mass and/or high creatine intake, such as many in the US Department of Defense (DoD) and US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) patient populations. In the presented case, recorded Cr levels climbed from baseline Cr with the initiation of bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide. This raised the concern that HIV treatment was leading to the development of kidney damage.22

Diagnosis of kidney disease as opposed to the normal decline of eGFR with age in individuals without intrinsic CKD requires GFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 with kidney damage (proteinuria or radiological abnormalities, etc) or GFR < 135 to 140 mL/min/1.73 m2minus the patient’s age in years.23 The patient’s Cr peak at 1.83 mg/dL in 2018 led to an inappropriate diagnosis of kidney disease stage 3a based on an eGFRCr (2021 equation) of 52 mL/min/1.73 m2 when not corrected for body surface area.20 However, using the new 2021 equation using both Cr and CysC, the patient’s eGFRCr-Cyswas 92 mL/min/1.73 m2 after a correction for body surface area.

The 2009 CKD-EPI recommended the calculation of eGFR based on SCr concentration using age, sex, and race while the 2021 CKD-EPI recommended the exclusion of race.3 Both equations are less accurate in African American patients, individuals taking medications that interfere with Cr secretion and assay, and patients taking creatine supplements, high daily protein intake, or with high muscle mass.7 These settings result in a decreased eGFRCr without corresponding eGFRCys changes. Using SCr and CysC together, the eGFRCr-Cys yields improved concordance to measured GFR across race groups compared to GFR estimation based on Cr alone, which can avoid unnecessary expensive diagnostic workup, inappropriate kidney disease diagnosis, incorrect dosing of drugs, and accurately represent the military readiness of patients. Interestingly, in African American patients with recently diagnosed HIV, CKD-EPI using both Cr and CysC without race inclusion led to only a 2.9% overestimation of GFR and was the only equation with no statistically significant bias compared with measured GFR.24

A March 2023 case involving an otherwise healthy 26-year-old male active-duty US Navy member with a history of excessive protein supplement intake and intense exercise < 24 hours before laboratory work was diagnosed with CKD after a measured Cr of 16 mg/dL and an eGFRCr of 4 mL/min/1.73 m2 without any other evidence of kidney disease. His CysC remained within normal limits, resulting in a normal eGFRCys of 121 mL/min/1.73 m2, indicating no CKD. His Cr and eGFR recovered 10 days after his clinic visit and cessation of his supplement intake. These findings may not be uncommon given that 65% of active-duty military use protein supplements and 38% use other performance-enhancing supplements, such as creatine, according to a study.25

Unfortunately, the BMP/CMP traditionally used at VA centers use the eGFRCr equation, and it is unknown how many primary care practitioners recognize the limitations of these metabolic panels on accurate estimation of kidney function. However, in 2022 an expert panel including VA physicians recommended the immediate use of eGFRCr-Cys or eGFRCys for confirmatory testing and potentially screening of CKD.26 A small number of VAs have since adopted this recommendation, which should lead to fewer misdiagnoses among US military members as clinicians should now have access to more accurate measurements of GFR.

The VA spends about $18 billion (excluding dialysis) for care for 1.1 to 2.5 million VA patients with CKD.27 The majority of these diagnoses were undoubtedly made using the eGFRCr equation, raising the question of how many may be misdiagnosed. Assessment with CysC is currently relatively expensive, but it will likely become more affordable as the use of CysC as a confirmatory test increases.5 The cost of a sCr test is about $2.50, while CysC costs about $10.60, with variation from laboratory to laboratory.28 By comparison, a renal ultrasound costs $99 to $140 for uninsured patients.29 Furthermore, the cost of CysC testing is likely to trend downward as more facilities adopt the use of CysC measurements, which can be run on the same analytical equipment currently used for Cr measurements. Currently, most laboratories do not have established assays to use in-house and thus require CysC to be sent out to a laboratory, which increases result time and makes Cr a more attractive option. As more laboratories adopt assays for CysC, the cost of reagents will further decrease.

Given such considerations, confirmation testing of kidney function with CysC in specific patient populations with decreased eGFRCr without other features of CKD can offer great medical and financial benefits. A 2023 KDIGO report noted that many individuals may be mistakenly diagnosed with CKD when using eGFRCr.3 KDIGO noted that a 2013 meta-analysis of 90,000 individuals found that with a Cr-based eGFR of 45 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2 (42%) had a CysC-based eGFR of ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. An eGFRCr of 45 to 59 represents 54% of all patients with CKD, amounting to millions of people (including current and former military personnel).3,29-31 Correcting a misdiagnosis of CKD would bring significant relief to patients and save millions in health care spending.

Conclusions

In patients who meet CKD criteria using eGFRCr but without other features of CKD, we recommend using confirmatory CysC levels and the eGFRCr-Cys equation. This will align care with the KDIGO guidelines and could be a cost-effective step toward improving military patient care. Further work in this area should focus on determining the knowledge gaps in primary care practitioners’ understanding of the limits of eGFRCr, the potential mitigation of concomitant CysC testing in equivocal CKD cases, and the cost-effectiveness and increased utilization of CysC.

1. Gabriel R. Time to scrap creatinine clearance? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293(6555):1119-1120. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6555.1119

2. Swan SK. The search continues—an ideal marker of GFR. Clin Chem. 1997;43(6):913-914.doi:10.1093/clinchem/43.6.913 3. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(1).

4. Wyss M, Kaddurah-Daouk R. Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(3):1107-1213. doi:10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1107

5. Ferguson TW, Komenda P, Tangri N. Cystatin C as a biomarker for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24(3):295-300. doi:10.1097/mnh.0000000000000115

6. Levey AS, Titan SM, Powe NR, Coresh J, Inker LA. Kidney disease, race, and GFR estimation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(8):1203-1212. doi:10.2215/cjn.12791019

7. Shlipak MG, Tummalapalli SL, Boulware LE, et al; Conference Participants. The case for early identification and intervention of chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2021;99(1):34-47. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.012

8. O’Riordan SE, Webb MC, Stowe HJ, et al. Cystatin C improves the detection of mild renal dysfunction in older patients. Ann Clin Biochem. 2003;40(pt 6):648-655. doi:10.1258/000456303770367243

9. Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, et al. Factors other than glomerular filtration rate affect serum cystatin C levels. Kidney Int. 2009;75(6):652-660. doi:10.1038/ki.2008.638

10. Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):247-254. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004

11. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604-612. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006

12. Pöge U, Gerhardt T, Stoffel-Wagner B, Klehr HU, Sauerbruch T, Woitas RP. Calculation of glomerular filtration rate based on cystatin C in cirrhotic patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(3):660-664. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfi305

13. Larsson A, Malm J, Grubb A, Hansson LO. Calculation of glomerular filtration rate expressed in mL/min from plasma cystatin C values in mg/L. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2004;64(1):25-30. doi:10.1080/00365510410003723.

14. Macisaac RJ, Tsalamandris C, Thomas MC, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate in diabetes: a comparison of cystatin-C- and creatinine-based methods. Diabetologia. 2006;49(7):1686-1689. doi:10.1007/s00125-006-0275-7

15. Rule AD, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Bergert J, Larson TS. Glomerular filtration rate estimated by cystatin C among different clinical presentations. Kidney Int. 2006;69(2):399-405. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5000073

16. Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Investigators. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):20-29. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1114248

17. Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Ärnlöv J, et al; CKD Prognosis Consortium. Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(10):932-943. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214234

18. Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. New creatinine- and cystatin C–Based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1737-1749. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2102953

19. Oterdoom LH, Gansevoort RT, Schouten JP, de Jong PE, Gans ROB, Bakker SJL. Urinary creatinine excretion, an indirect measure of muscle mass, is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the general population. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207(2):534-540. doi.10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.05.010

20. National Kidney Foundation Inc. eGFR calculator. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/gfr_calculator

21. Ueaphongsukkit T, Gatechompol S, Avihingsanon A, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide nephrotoxicity: a case report and literature review. AIDS Res Ther. 2021;18(1):53. doi:10.1186/s12981-021-00380-w

22. D’Agati V, Appel GB. Renal pathology of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Semin Nephrol. 1998;18(4):406-421.

23. Glassock RJ, Winearls C. Ageing and the glomerular filtration rate: truths and consequences. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2009;120:419-428.

24. Seape T, Gounden V, van Deventer HE, Candy GP, George JA. Cystatin C- and creatinine-based equations in the assessment of renal function in HIV-positive patients prior to commencing highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ann Clin Biochem. 2016;53(pt 1):58-66. doi:10.1177/0004563215579695

25. Tobin TW, Thurlow JS, Yuan CM. A healthy active duty soldier with an elevated serum creatinine. Mil Med. 2023;188(3-4):e866-e869. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab163

26. Delgado C, Baweja M, Crews DC, et al. A unifying approach for GFR estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN Task Force on Reassessing the Inclusion of Race in Diagnosing Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79(2):268-288.e1. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.08.003

27. Saran R, Pearson A, Tilea A, et al; VA-REINS Steering Committee; VA Advisory Board. Burden and cost of caring for us veterans with CKD: initial findings from the VA Renal Information System (VA-REINS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(3):397-405. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.07.013

28. Zoler ML. Nephrologists make the case for cystatin C-based eGFR. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/951335#vp_2

29. Versaw N. How much does an ultrasound cost? Updated February 2022. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.compare.com/health/healthcare-resources/how-much-does-an-ultrasound-cost

30. Levey AS, Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9811):165-180. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60178-5

31. Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Ärnlöv J, et al; CKD Prognosis Consortium. Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(10):932-943. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214234

1. Gabriel R. Time to scrap creatinine clearance? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293(6555):1119-1120. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6555.1119

2. Swan SK. The search continues—an ideal marker of GFR. Clin Chem. 1997;43(6):913-914.doi:10.1093/clinchem/43.6.913 3. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(1).

4. Wyss M, Kaddurah-Daouk R. Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(3):1107-1213. doi:10.1152/physrev.2000.80.3.1107

5. Ferguson TW, Komenda P, Tangri N. Cystatin C as a biomarker for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24(3):295-300. doi:10.1097/mnh.0000000000000115

6. Levey AS, Titan SM, Powe NR, Coresh J, Inker LA. Kidney disease, race, and GFR estimation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(8):1203-1212. doi:10.2215/cjn.12791019

7. Shlipak MG, Tummalapalli SL, Boulware LE, et al; Conference Participants. The case for early identification and intervention of chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2021;99(1):34-47. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.012

8. O’Riordan SE, Webb MC, Stowe HJ, et al. Cystatin C improves the detection of mild renal dysfunction in older patients. Ann Clin Biochem. 2003;40(pt 6):648-655. doi:10.1258/000456303770367243

9. Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, et al. Factors other than glomerular filtration rate affect serum cystatin C levels. Kidney Int. 2009;75(6):652-660. doi:10.1038/ki.2008.638

10. Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):247-254. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004

11. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604-612. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006

12. Pöge U, Gerhardt T, Stoffel-Wagner B, Klehr HU, Sauerbruch T, Woitas RP. Calculation of glomerular filtration rate based on cystatin C in cirrhotic patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(3):660-664. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfi305

13. Larsson A, Malm J, Grubb A, Hansson LO. Calculation of glomerular filtration rate expressed in mL/min from plasma cystatin C values in mg/L. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2004;64(1):25-30. doi:10.1080/00365510410003723.

14. Macisaac RJ, Tsalamandris C, Thomas MC, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate in diabetes: a comparison of cystatin-C- and creatinine-based methods. Diabetologia. 2006;49(7):1686-1689. doi:10.1007/s00125-006-0275-7

15. Rule AD, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Bergert J, Larson TS. Glomerular filtration rate estimated by cystatin C among different clinical presentations. Kidney Int. 2006;69(2):399-405. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5000073

16. Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Investigators. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):20-29. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1114248

17. Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Ärnlöv J, et al; CKD Prognosis Consortium. Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(10):932-943. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214234

18. Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, et al; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration. New creatinine- and cystatin C–Based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1737-1749. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2102953

19. Oterdoom LH, Gansevoort RT, Schouten JP, de Jong PE, Gans ROB, Bakker SJL. Urinary creatinine excretion, an indirect measure of muscle mass, is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease and mortality in the general population. Atherosclerosis. 2009;207(2):534-540. doi.10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.05.010

20. National Kidney Foundation Inc. eGFR calculator. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/gfr_calculator

21. Ueaphongsukkit T, Gatechompol S, Avihingsanon A, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide nephrotoxicity: a case report and literature review. AIDS Res Ther. 2021;18(1):53. doi:10.1186/s12981-021-00380-w

22. D’Agati V, Appel GB. Renal pathology of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Semin Nephrol. 1998;18(4):406-421.

23. Glassock RJ, Winearls C. Ageing and the glomerular filtration rate: truths and consequences. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2009;120:419-428.

24. Seape T, Gounden V, van Deventer HE, Candy GP, George JA. Cystatin C- and creatinine-based equations in the assessment of renal function in HIV-positive patients prior to commencing highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ann Clin Biochem. 2016;53(pt 1):58-66. doi:10.1177/0004563215579695

25. Tobin TW, Thurlow JS, Yuan CM. A healthy active duty soldier with an elevated serum creatinine. Mil Med. 2023;188(3-4):e866-e869. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab163

26. Delgado C, Baweja M, Crews DC, et al. A unifying approach for GFR estimation: recommendations of the NKF-ASN Task Force on Reassessing the Inclusion of Race in Diagnosing Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79(2):268-288.e1. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.08.003

27. Saran R, Pearson A, Tilea A, et al; VA-REINS Steering Committee; VA Advisory Board. Burden and cost of caring for us veterans with CKD: initial findings from the VA Renal Information System (VA-REINS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(3):397-405. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.07.013

28. Zoler ML. Nephrologists make the case for cystatin C-based eGFR. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/951335#vp_2

29. Versaw N. How much does an ultrasound cost? Updated February 2022. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://www.compare.com/health/healthcare-resources/how-much-does-an-ultrasound-cost

30. Levey AS, Coresh J. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9811):165-180. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60178-5

31. Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Ärnlöv J, et al; CKD Prognosis Consortium. Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(10):932-943. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1214234

Sodium vs Potassium for Lowering Blood Pressure?

A pair of dueling editorials in the journal Hypertension debate whether our focus should be on sodium or its often neglected partner, potassium.

A meta-analysis of 85 trials showed a consistent and linear. It may also depend on where you live and whether your concern is treating individuals or implementing effective food policy.

The Case for Sodium Restriction

Stephen Juraschek, MD, PhD, of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, co-author of one editorial, told me in a zoom interview that he believes his side of the debate clearly has the stronger argument. Of the two cations in question, there has been infinitely more ink spilled about sodium.

Studies such as INTERSALT, the DASH diet, and TOHP may be the most well-known, but there are many, many intervention studies of sodium restriction’s effect on blood pressure. A meta-analysis of 85 trials of showed a consistent and linear relationship between sodium reduction and blood pressure. In contrast, the evidence base for potassium is more limited and less consistent. There are half as many trials with potassium, and its ability to lower blood pressure may depend on how much sodium is present in the diet.

An outlier in the sodium restriction evidence base is the PURE study, which suggested that extreme sodium restriction could increase cardiovascular mortality, but the trial suffered from two potential issues. First, it used a single spot urine specimen to measure sodium rather than the generally accepted more accurate 24-hour urine collection. A reanalysis of the TOHP study using a spot urine rather than a 24-hour urine collection changed the relationship between sodium intake and mortality and possibly explained the U-shaped association observed in PURE. Second, PURE was an observational cohort and was prone to confounding, or in this case, reverse causation. Why did people who consumed very little salt have an increased risk for cardiovascular disease? It is very possible that people with a high risk for cardiovascular disease were told to consume less salt to begin with. Hence B led to A rather than A leading to B.

The debate on sodium restriction has been bitter at times. Opposing camps formed, and people took sides in the “salt wars.” A group of researchers, termed the Jackson 6, met and decided to end the controversy by running a randomized trial in US prisons (having discounted the options of long-term care homes and military bases). They detailed their plan in an editorial in Hypertension. The study never came to fruition for two reasons: the obvious ethical problems of experimenting on prisoners and the revelation of undisclosed salt industry funding.

More recent studies have mercifully been more conventional. The SSaSS study, a randomized controlled trial of a salt substitute, provided the cardiovascular outcomes data that many were waiting for. And CARDIA-SSBP, a cross-over randomized trial recently presented at the American Heart Association meeting, showed that reducing dietary sodium was on par with medication when it came to lowering blood pressure.

For Dr. Juraschek, the evidence is clear: “If you were going to choose one, I would say the weight of the evidence is still really heavily on the sodium side.”

The Case for Potassium Supplementation

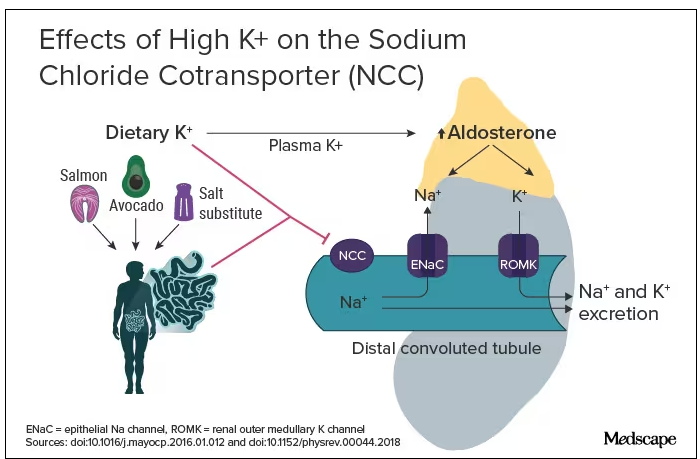

The evidence for salt restriction notwithstanding, Swapnil Hiremath, MD, MPH, from the University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, argued in his editorial that potassium supplementation has gotten short shrift. Though he admits the studies for potassium supplementation have been smaller and sometimes rely on observational evidence, the evidence is there. In the distal convoluted tubule, the sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC), aka the potassium switch, is turned on by low potassium levels and leads to sodium reabsorption by the kidney even in settings of high sodium intake (Figure). To nonnephrologists, renal physiology may be a black box. But if you quickly brush up on the mechanism of action of thiazide diuretics, the preceding descriptor will make more sense.

Dr. Hiremath points out that the DASH diet study also got patients to increase their potassium intake by eating more fruits and vegetables. Furthermore, the SSaSS study tested a salt substitute that was 25% potassium (and 75% sodium).

How much blood pressure lowering is due to sodium restriction vs potassium supplementation is a complex question because lowering sodium intake will invariably lead to more potassium intake. “It’s very hard to untangle the relationship,” Dr. Hiremath said in an interview. “It’s sort of synergistic but it’s not completely additive. It’s not as if you add four and four and get eight.” But he maintains there is more evidence regarding the benefit of potassium supplementation than many realize.

Realistic Diets and Taste Issues

“We know that increasing potassium, decreasing sodium is useful. The question is how do we do that?” says Dr. Hiremath. Should we encourage fruit and vegetable consumption in a healthy diet, give potassium supplements, or encourage the use of low-sodium salt substitutes?

Recommending a healthier diet with more fruits and vegetables is a no-brainer. But getting people to do it is hard. In a world where fruit is more expensive than junk food is, economic realities may drive food choice regardless of our best efforts. The 4700 mg of potassium in the DASH eating plan is the equivalent of eleven bananas daily; although not impossible, it would require a substantive shift in eating patterns for most people.

Given that we prescribe iron, vitamin B12, calcium, and vitamin D to patients who need them, why not potassium tablets to help with blood pressure? Granted, there are concerns about inducing hyperkalemia. Also, why not just prescribe a proven anti-hypertensive, such as ramipril, which has the added benefit of helping with renal protection or cardiac remodeling? Dr. Hiremath points out that patients are far less reluctant to take dietary supplements. Medication is something you take when sick. A supplement is seen as “natural” and “healthy” and might be more attractive to people resistant to prescription meds.

Another drawback of oral potassium supplementation is taste. In a Consumer Reports taste test, potassium chloride fared poorly. It was bitter and had a metallic aftertaste. At least one tester wouldn’t ever consume it again. Potassium citrate is slightly more palpable.

Salt substitutes, like the 75:25 ratio of sodium to potassium used in SSaSS, may be as high as you can go for potassium in any low-sodium salt alternative. If you go any higher than that, the taste will just turn people off, suggests Dr. Hiremath.

But SsaSS, which was done in China, may not be relevant to North America. In China, most sodium is added during cooking at home, and the consumption of processed foods is low. For the typical North American, roughly three quarters of the sodium eaten is added to their food by someone else; only about 15% is added during cooking at home or at the dinner table. If you aren’t someone who cooks, buying a salt substitute is probably not going to have much impact.

Given that reality, Dr. Juraschek thinks we need to target the sodium in processed foods. “There’s just so much sodium in so many products,” he says. “When you think about public policy, it’s most expeditious for there to be more regulation about how much is added to our food supply vs trying to get people to consume eight to 12 servings of fruit.”

No Salt War Here

Despite their different editorial takes, Dr. Hiremath and Dr. Juraschek largely agree on the broad strokes of the problem. This isn’t X (or Twitter) after all. Potassium supplementation may be useful in some parts of the world but may not address the underlying problem in countries where processed foods are the source of most dietary sodium.

The CARDIA-SSBP trial showed that a very low–sodium diet had the same blood pressure–lowering effect as a first-line antihypertensive, but most people will not be able to limit themselves to 500 mg of dietary sodium per day. In CARDIA-SSBP, just as in DASH, participants were provided with meals from study kitchens. They were not just told to eat less salt, which would almost certainly have failed.

“We should aim for stuff that is practical and doable rather than aim for stuff that cannot be done,” according to Dr. Hiremath. Whether that should be salt substitutes or policy change may depend on which part of the planet you live on.

One recent positive change may herald the beginning of a policy change, at least in the United States. In March 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration proposed a rule change to allow salt substitutes to be labeled as salt. This would make it easier for food manufacturers to swap out sodium chloride for a low-sodium alternative and reduce the amount of sodium in the US diet without having a large impact on taste and consumer uptake. Both Dr. Hiremath and Dr. Juraschek agree that it may not be enough on its own but that it’s a start.

Christopher Labos is a cardiologist with a degree in epidemiology. He spends most of his time doing things that he doesn’t get paid for, like research, teaching, and podcasting. Occasionally, he finds time to practice cardiology to pay the rent. He realizes that half of his research findings will be disproved in 5 years; he just doesn’t know which half. He is a regular contributor to the Montreal Gazette, CJAD radio, and CTV television in Montreal, and is host of the award-winning podcast The Body of Evidence.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A pair of dueling editorials in the journal Hypertension debate whether our focus should be on sodium or its often neglected partner, potassium.

A meta-analysis of 85 trials showed a consistent and linear. It may also depend on where you live and whether your concern is treating individuals or implementing effective food policy.

The Case for Sodium Restriction

Stephen Juraschek, MD, PhD, of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, co-author of one editorial, told me in a zoom interview that he believes his side of the debate clearly has the stronger argument. Of the two cations in question, there has been infinitely more ink spilled about sodium.

Studies such as INTERSALT, the DASH diet, and TOHP may be the most well-known, but there are many, many intervention studies of sodium restriction’s effect on blood pressure. A meta-analysis of 85 trials of showed a consistent and linear relationship between sodium reduction and blood pressure. In contrast, the evidence base for potassium is more limited and less consistent. There are half as many trials with potassium, and its ability to lower blood pressure may depend on how much sodium is present in the diet.