User login

‘Empathy fatigue’ in clinicians rises with latest COVID-19 surge

Heidi Erickson, MD, is tired. As a pulmonary and critical care physician at Hennepin Healthcare in Minneapolis, she has been providing care for patients with COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic.

It was exhausting from the beginning, as she and her colleagues scrambled to understand how to deal with this new disease. But lately, she has noticed a different kind of exhaustion arising from the knowledge that with vaccines widely available, the latest surge was preventable.

Her intensive care unit is currently as full as it has ever been with COVID-19 patients, many of them young adults and most of them unvaccinated. After the recent death of one patient, an unvaccinated man with teenage children, she had to face his family’s questions about why ivermectin, an antiparasitic medication that was falsely promoted as a COVID-19 treatment, was not administered.

“I’m fatigued because I’m working more than ever, but more people don’t have to die,” Dr. Erickson said in an interview . “It’s been very hard physically, mentally, emotionally.”

Amid yet another surge in COVID-19 cases around the United States, clinicians are speaking out about their growing frustration with this preventable crisis.

Some are using the terms “empathy fatigue” and “compassion fatigue” – a sense that they are losing empathy for unvaccinated individuals who are fueling the pandemic.

Dr. Erickson says she is frustrated not by individual patients but by a system that has allowed disinformation to proliferate. Experts say these types of feelings fit into a widespread pattern of physician burnout that has taken a new turn at this stage of the pandemic.

Paradoxical choices

Empathy is a cornerstone of what clinicians do, and the ability to understand and share a patient’s feelings is an essential skill for providing effective care, says Kaz Nelson, MD, a psychiatrist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Practitioners face paradoxical situations all the time, she notes. These include individuals who break bones and go skydiving again, people who have high cholesterol but continue to eat fried foods, and those with advanced lung cancer who continue to smoke.

To treat patients with compassion, practitioners learn to set aside judgment by acknowledging the complexity of human behavior. They may lament the addictive nature of nicotine and advertising that targets children, for example, while still listening and caring.

Empathy requires high-level brain function, but as stress levels rise, brain function that drives empathy tends to shut down. It’s a survival mechanism, Dr. Nelson says.

When health care workers feel overwhelmed, trapped, or threatened by patients demanding unproven treatments or by ICUs with more patients than ventilators, they may experience a fight-or-flight response that makes them defensive, frustrated, angry, or uncaring, notes Mona Masood, DO, a Philadelphia-area psychiatrist and founder of Physician Support Line, a free mental health hotline for doctors.

Some clinicians have taken to Twitter and other social media platforms to post about these types of experiences.

These feelings, which have been brewing for months, have been exacerbated by the complexity of the current situation. Clinicians see a disconnect between what is and what could be, Dr. Nelson notes.

“Prior to vaccines, there weren’t other options, and so we had toxic stress and we had fatigue, but we could still maintain little bits of empathy by saying, ‘You know, people didn’t choose to get infected, and we are in a pandemic.’ We could kind of hate the virus. Now with access to vaccines, that last connection to empathy is removed for many people,” she says.

Self-preservation vs. empathy

Compassion fatigue or empathy fatigue is just one reaction to feeling completely maxed out and overstressed, Dr. Nelson says. Anger at society, such as what Dr. Erickson experienced, is another response.

Practitioners may also feel as if they are just going through the motions of their job, or they might disassociate, ceasing to feel that their patients are human. Plenty of doctors and nurses have cried in their cars after shifts and have posted tearful videos on social media.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Masood says, physicians who called the support hotline expressed sadness and grief. Now, she had her colleagues hear frustration and anger, along with guilt and shame for having feelings they believe they shouldn’t be having, especially toward patients. They may feel unprofessional or worse – unworthy of being physicians, she says.

One recent caller to the hotline was a long-time ICU physician who had been told so many times by patients that ivermectin was the only medicine that would cure them that he began to doubt himself, says Dr. Masood. This caller needed to be reassured by another physician that he was doing the right thing.

Another emergency department physician told Dr. Masood about a young child who had arrived at the hospital with COVID-19 symptoms. When asked whether the family had been exposed to anyone with COVID-19, the child’s parent lied so that they could be triaged faster.

The physician, who needed to step away from the situation, reached out to Dr. Masood to express her frustration so that she wouldn’t “let it out” on the patient.

“It’s hard to have empathy for people who, for all intents and purposes, are very self-centered,” Dr. Masood says. “We’re at a place where we’re having to choose between self-preservation and empathy.”

How to cope

To help practitioners cope, Dr. Masood offers words that describe what they’re experiencing. She often hears clinicians say things such as, “This is a type of burnout that I feel to my bones,” or “This makes me want to quit,” or “I feel like I’m at the end of my rope.”

She encourages them to consider the terms “empathy fatigue,” and “moral injury” in order to reconcile how their sense of responsibility to take care of people is compromised by factors outside of their control.

It is not shameful to acknowledge that they experience emotions, including difficult ones such as frustration, anger, sadness, and anxiety, Dr. Masood adds.

Being frustrated with a patient doesn’t make someone a bad doctor, and admitting those emotions is the first step toward dealing with them, she says.

before they cause a sense of callousness or other consequences that become harder to heal from as time goes on.

“We’re trained to just go, go, go and sometimes not pause and check in,” she says. Clinicians who open up are likely to find they are not the only ones feeling tired or frustrated right now, she adds.

“Connect with peers and colleagues, because chances are, they can relate,” Dr. Nelson says.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Heidi Erickson, MD, is tired. As a pulmonary and critical care physician at Hennepin Healthcare in Minneapolis, she has been providing care for patients with COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic.

It was exhausting from the beginning, as she and her colleagues scrambled to understand how to deal with this new disease. But lately, she has noticed a different kind of exhaustion arising from the knowledge that with vaccines widely available, the latest surge was preventable.

Her intensive care unit is currently as full as it has ever been with COVID-19 patients, many of them young adults and most of them unvaccinated. After the recent death of one patient, an unvaccinated man with teenage children, she had to face his family’s questions about why ivermectin, an antiparasitic medication that was falsely promoted as a COVID-19 treatment, was not administered.

“I’m fatigued because I’m working more than ever, but more people don’t have to die,” Dr. Erickson said in an interview . “It’s been very hard physically, mentally, emotionally.”

Amid yet another surge in COVID-19 cases around the United States, clinicians are speaking out about their growing frustration with this preventable crisis.

Some are using the terms “empathy fatigue” and “compassion fatigue” – a sense that they are losing empathy for unvaccinated individuals who are fueling the pandemic.

Dr. Erickson says she is frustrated not by individual patients but by a system that has allowed disinformation to proliferate. Experts say these types of feelings fit into a widespread pattern of physician burnout that has taken a new turn at this stage of the pandemic.

Paradoxical choices

Empathy is a cornerstone of what clinicians do, and the ability to understand and share a patient’s feelings is an essential skill for providing effective care, says Kaz Nelson, MD, a psychiatrist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Practitioners face paradoxical situations all the time, she notes. These include individuals who break bones and go skydiving again, people who have high cholesterol but continue to eat fried foods, and those with advanced lung cancer who continue to smoke.

To treat patients with compassion, practitioners learn to set aside judgment by acknowledging the complexity of human behavior. They may lament the addictive nature of nicotine and advertising that targets children, for example, while still listening and caring.

Empathy requires high-level brain function, but as stress levels rise, brain function that drives empathy tends to shut down. It’s a survival mechanism, Dr. Nelson says.

When health care workers feel overwhelmed, trapped, or threatened by patients demanding unproven treatments or by ICUs with more patients than ventilators, they may experience a fight-or-flight response that makes them defensive, frustrated, angry, or uncaring, notes Mona Masood, DO, a Philadelphia-area psychiatrist and founder of Physician Support Line, a free mental health hotline for doctors.

Some clinicians have taken to Twitter and other social media platforms to post about these types of experiences.

These feelings, which have been brewing for months, have been exacerbated by the complexity of the current situation. Clinicians see a disconnect between what is and what could be, Dr. Nelson notes.

“Prior to vaccines, there weren’t other options, and so we had toxic stress and we had fatigue, but we could still maintain little bits of empathy by saying, ‘You know, people didn’t choose to get infected, and we are in a pandemic.’ We could kind of hate the virus. Now with access to vaccines, that last connection to empathy is removed for many people,” she says.

Self-preservation vs. empathy

Compassion fatigue or empathy fatigue is just one reaction to feeling completely maxed out and overstressed, Dr. Nelson says. Anger at society, such as what Dr. Erickson experienced, is another response.

Practitioners may also feel as if they are just going through the motions of their job, or they might disassociate, ceasing to feel that their patients are human. Plenty of doctors and nurses have cried in their cars after shifts and have posted tearful videos on social media.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Masood says, physicians who called the support hotline expressed sadness and grief. Now, she had her colleagues hear frustration and anger, along with guilt and shame for having feelings they believe they shouldn’t be having, especially toward patients. They may feel unprofessional or worse – unworthy of being physicians, she says.

One recent caller to the hotline was a long-time ICU physician who had been told so many times by patients that ivermectin was the only medicine that would cure them that he began to doubt himself, says Dr. Masood. This caller needed to be reassured by another physician that he was doing the right thing.

Another emergency department physician told Dr. Masood about a young child who had arrived at the hospital with COVID-19 symptoms. When asked whether the family had been exposed to anyone with COVID-19, the child’s parent lied so that they could be triaged faster.

The physician, who needed to step away from the situation, reached out to Dr. Masood to express her frustration so that she wouldn’t “let it out” on the patient.

“It’s hard to have empathy for people who, for all intents and purposes, are very self-centered,” Dr. Masood says. “We’re at a place where we’re having to choose between self-preservation and empathy.”

How to cope

To help practitioners cope, Dr. Masood offers words that describe what they’re experiencing. She often hears clinicians say things such as, “This is a type of burnout that I feel to my bones,” or “This makes me want to quit,” or “I feel like I’m at the end of my rope.”

She encourages them to consider the terms “empathy fatigue,” and “moral injury” in order to reconcile how their sense of responsibility to take care of people is compromised by factors outside of their control.

It is not shameful to acknowledge that they experience emotions, including difficult ones such as frustration, anger, sadness, and anxiety, Dr. Masood adds.

Being frustrated with a patient doesn’t make someone a bad doctor, and admitting those emotions is the first step toward dealing with them, she says.

before they cause a sense of callousness or other consequences that become harder to heal from as time goes on.

“We’re trained to just go, go, go and sometimes not pause and check in,” she says. Clinicians who open up are likely to find they are not the only ones feeling tired or frustrated right now, she adds.

“Connect with peers and colleagues, because chances are, they can relate,” Dr. Nelson says.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Heidi Erickson, MD, is tired. As a pulmonary and critical care physician at Hennepin Healthcare in Minneapolis, she has been providing care for patients with COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic.

It was exhausting from the beginning, as she and her colleagues scrambled to understand how to deal with this new disease. But lately, she has noticed a different kind of exhaustion arising from the knowledge that with vaccines widely available, the latest surge was preventable.

Her intensive care unit is currently as full as it has ever been with COVID-19 patients, many of them young adults and most of them unvaccinated. After the recent death of one patient, an unvaccinated man with teenage children, she had to face his family’s questions about why ivermectin, an antiparasitic medication that was falsely promoted as a COVID-19 treatment, was not administered.

“I’m fatigued because I’m working more than ever, but more people don’t have to die,” Dr. Erickson said in an interview . “It’s been very hard physically, mentally, emotionally.”

Amid yet another surge in COVID-19 cases around the United States, clinicians are speaking out about their growing frustration with this preventable crisis.

Some are using the terms “empathy fatigue” and “compassion fatigue” – a sense that they are losing empathy for unvaccinated individuals who are fueling the pandemic.

Dr. Erickson says she is frustrated not by individual patients but by a system that has allowed disinformation to proliferate. Experts say these types of feelings fit into a widespread pattern of physician burnout that has taken a new turn at this stage of the pandemic.

Paradoxical choices

Empathy is a cornerstone of what clinicians do, and the ability to understand and share a patient’s feelings is an essential skill for providing effective care, says Kaz Nelson, MD, a psychiatrist at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Practitioners face paradoxical situations all the time, she notes. These include individuals who break bones and go skydiving again, people who have high cholesterol but continue to eat fried foods, and those with advanced lung cancer who continue to smoke.

To treat patients with compassion, practitioners learn to set aside judgment by acknowledging the complexity of human behavior. They may lament the addictive nature of nicotine and advertising that targets children, for example, while still listening and caring.

Empathy requires high-level brain function, but as stress levels rise, brain function that drives empathy tends to shut down. It’s a survival mechanism, Dr. Nelson says.

When health care workers feel overwhelmed, trapped, or threatened by patients demanding unproven treatments or by ICUs with more patients than ventilators, they may experience a fight-or-flight response that makes them defensive, frustrated, angry, or uncaring, notes Mona Masood, DO, a Philadelphia-area psychiatrist and founder of Physician Support Line, a free mental health hotline for doctors.

Some clinicians have taken to Twitter and other social media platforms to post about these types of experiences.

These feelings, which have been brewing for months, have been exacerbated by the complexity of the current situation. Clinicians see a disconnect between what is and what could be, Dr. Nelson notes.

“Prior to vaccines, there weren’t other options, and so we had toxic stress and we had fatigue, but we could still maintain little bits of empathy by saying, ‘You know, people didn’t choose to get infected, and we are in a pandemic.’ We could kind of hate the virus. Now with access to vaccines, that last connection to empathy is removed for many people,” she says.

Self-preservation vs. empathy

Compassion fatigue or empathy fatigue is just one reaction to feeling completely maxed out and overstressed, Dr. Nelson says. Anger at society, such as what Dr. Erickson experienced, is another response.

Practitioners may also feel as if they are just going through the motions of their job, or they might disassociate, ceasing to feel that their patients are human. Plenty of doctors and nurses have cried in their cars after shifts and have posted tearful videos on social media.

Early in the pandemic, Dr. Masood says, physicians who called the support hotline expressed sadness and grief. Now, she had her colleagues hear frustration and anger, along with guilt and shame for having feelings they believe they shouldn’t be having, especially toward patients. They may feel unprofessional or worse – unworthy of being physicians, she says.

One recent caller to the hotline was a long-time ICU physician who had been told so many times by patients that ivermectin was the only medicine that would cure them that he began to doubt himself, says Dr. Masood. This caller needed to be reassured by another physician that he was doing the right thing.

Another emergency department physician told Dr. Masood about a young child who had arrived at the hospital with COVID-19 symptoms. When asked whether the family had been exposed to anyone with COVID-19, the child’s parent lied so that they could be triaged faster.

The physician, who needed to step away from the situation, reached out to Dr. Masood to express her frustration so that she wouldn’t “let it out” on the patient.

“It’s hard to have empathy for people who, for all intents and purposes, are very self-centered,” Dr. Masood says. “We’re at a place where we’re having to choose between self-preservation and empathy.”

How to cope

To help practitioners cope, Dr. Masood offers words that describe what they’re experiencing. She often hears clinicians say things such as, “This is a type of burnout that I feel to my bones,” or “This makes me want to quit,” or “I feel like I’m at the end of my rope.”

She encourages them to consider the terms “empathy fatigue,” and “moral injury” in order to reconcile how their sense of responsibility to take care of people is compromised by factors outside of their control.

It is not shameful to acknowledge that they experience emotions, including difficult ones such as frustration, anger, sadness, and anxiety, Dr. Masood adds.

Being frustrated with a patient doesn’t make someone a bad doctor, and admitting those emotions is the first step toward dealing with them, she says.

before they cause a sense of callousness or other consequences that become harder to heal from as time goes on.

“We’re trained to just go, go, go and sometimes not pause and check in,” she says. Clinicians who open up are likely to find they are not the only ones feeling tired or frustrated right now, she adds.

“Connect with peers and colleagues, because chances are, they can relate,” Dr. Nelson says.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Online mental health treatment: Is this the answer we’ve been waiting for?

If you haven’t noticed yet, there has been an explosion of new online companies specializing in slicing off some little sliver of health care and leaving traditional medicine to take care of the rest of the patient. Lately, many of these startups involve mental health care, traditionally a difficult area to make profitable unless one caters just to the wealthy. Many pediatricians have been unsure exactly what to make of these new efforts. Are these the rescuers we’ve been waiting for to fill what seems like an enormous and growing unmet need? Are they just another means to extract money from desperate people and leave the real work to someone else? Something in-between? This article outlines some points to consider when evaluating this new frontier.

Case vignette

A 12-year-old girl presents with her parents for an annual exam. She has been struggling with her mood and anxiety over the past 2 years along with occasional superficial cutting. You have started treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and have recommended that she see a mental health professional but the parents report that one attempt with a therapist was a poor fit and nobody in the area seems to be accepting new patients. The parents state that they saw an advertisement on TV for a company that offers online psychotherapy by video appointments or text. They think this might be an option to pursue but are a little skeptical of the whole idea. They look for your opinion on this topic.

Most of these companies operate by having subscribers pay a monthly fee for different levels of services such as videoconference therapy sessions, supportive text messages, or even some psychopharmacological care. Many also offer the ability to switch rapidly between clinicians if you don’t like the one you have.

These arrangements sound great as the world grows increasingly comfortable with online communication and the mental health needs of children and adolescents increase with the seemingly endless COVID pandemic. Further, research generally finds that online mental health treatment is just as effective as services delivered in person, although the data on therapy by text are less robust.

Nevertheless, a lot of skepticism remains about online mental health treatment, particularly among those involved in more traditionally delivered mental health care. Some of the concerns that often get brought up include the following:

- Cost. Most of these online groups, especially the big national companies, don’t interact directly with insurance companies, leaving a lot of out-of-pocket expenses or the need for families to work things out directly with their insurance provider.

- Care fragmentation. In many ways, the online mental health care surge seems at odds with the growing “integrated care” movement that is trying to embed more behavioral care within primary care practices. From this lens, outsourcing someone’s mental health treatment to a therapist across the country that the patient has never actually met seems like a step in the wrong direction. Further, concerns arise about how much these folks will know about local resources in the community.

- The corporate model in mental health care. While being able to shop for a therapist like you would for a pillow sounds great on the surface, there are many times where a patient may need to be supportively confronted by their therapist or told no when asking about things like certain medications. The “customer is always right” principle often falls short when it comes to good mental health treatment.

- Depth and type of treatment. It is probably fair to say that most online therapy could be described as supportive psychotherapy. This type of therapy can be quite helpful for many but may lack the depth or specific techniques that some people need. For youth, some of the most effective types of psychotherapy, like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), can be harder to find, and implement, online.

- Emergencies. While many online companies claim to offer round-the-clock support for paying customers, they can quickly punt to “call your doctor” or even “call 911” if there is any real mental health crisis.

Balancing these potential benefits and pitfalls of online therapy, here are a few questions your patients may want to consider before signing onto a long-term contract with an online therapy company.

- Would the online clinician have any knowledge of my community? In some cases, this may not matter that much, while for others it could be quite important.

- What happens in an emergency? Would the regular online therapist be available to help through a crisis or would things revert back to local resources?

- What about privacy and collaboration? Effective communication between a patient’s primary care clinician and their therapist can be crucial to good care, and asking the patient always to be the intermediary can be fraught with difficulty.

- How long is the contract? Just like those gym memberships, these companies bank on individuals who sign up but then don’t really use the service.

- What kind of training do the therapists at the site have? Is it possible to receive specific types of therapy, like CBT or parent training? Otherwise, pediatricians might be quite likely to hear back from the family wondering about medications after therapy “isn’t helping.”

Overall, mental health treatment delivered by telehealth is here to stay whether we like it or not. For some families, it is likely to provide new access to services not easily obtainable locally, while for others it could end up being a costly and ineffective enterprise. For families who use these services, a key challenge for pediatricians that may be important to overcome is finding a way for these clinicians to integrate into the overall medical team rather than being a detached island unto themselves.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. His book, “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows About the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021). Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

If you haven’t noticed yet, there has been an explosion of new online companies specializing in slicing off some little sliver of health care and leaving traditional medicine to take care of the rest of the patient. Lately, many of these startups involve mental health care, traditionally a difficult area to make profitable unless one caters just to the wealthy. Many pediatricians have been unsure exactly what to make of these new efforts. Are these the rescuers we’ve been waiting for to fill what seems like an enormous and growing unmet need? Are they just another means to extract money from desperate people and leave the real work to someone else? Something in-between? This article outlines some points to consider when evaluating this new frontier.

Case vignette

A 12-year-old girl presents with her parents for an annual exam. She has been struggling with her mood and anxiety over the past 2 years along with occasional superficial cutting. You have started treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and have recommended that she see a mental health professional but the parents report that one attempt with a therapist was a poor fit and nobody in the area seems to be accepting new patients. The parents state that they saw an advertisement on TV for a company that offers online psychotherapy by video appointments or text. They think this might be an option to pursue but are a little skeptical of the whole idea. They look for your opinion on this topic.

Most of these companies operate by having subscribers pay a monthly fee for different levels of services such as videoconference therapy sessions, supportive text messages, or even some psychopharmacological care. Many also offer the ability to switch rapidly between clinicians if you don’t like the one you have.

These arrangements sound great as the world grows increasingly comfortable with online communication and the mental health needs of children and adolescents increase with the seemingly endless COVID pandemic. Further, research generally finds that online mental health treatment is just as effective as services delivered in person, although the data on therapy by text are less robust.

Nevertheless, a lot of skepticism remains about online mental health treatment, particularly among those involved in more traditionally delivered mental health care. Some of the concerns that often get brought up include the following:

- Cost. Most of these online groups, especially the big national companies, don’t interact directly with insurance companies, leaving a lot of out-of-pocket expenses or the need for families to work things out directly with their insurance provider.

- Care fragmentation. In many ways, the online mental health care surge seems at odds with the growing “integrated care” movement that is trying to embed more behavioral care within primary care practices. From this lens, outsourcing someone’s mental health treatment to a therapist across the country that the patient has never actually met seems like a step in the wrong direction. Further, concerns arise about how much these folks will know about local resources in the community.

- The corporate model in mental health care. While being able to shop for a therapist like you would for a pillow sounds great on the surface, there are many times where a patient may need to be supportively confronted by their therapist or told no when asking about things like certain medications. The “customer is always right” principle often falls short when it comes to good mental health treatment.

- Depth and type of treatment. It is probably fair to say that most online therapy could be described as supportive psychotherapy. This type of therapy can be quite helpful for many but may lack the depth or specific techniques that some people need. For youth, some of the most effective types of psychotherapy, like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), can be harder to find, and implement, online.

- Emergencies. While many online companies claim to offer round-the-clock support for paying customers, they can quickly punt to “call your doctor” or even “call 911” if there is any real mental health crisis.

Balancing these potential benefits and pitfalls of online therapy, here are a few questions your patients may want to consider before signing onto a long-term contract with an online therapy company.

- Would the online clinician have any knowledge of my community? In some cases, this may not matter that much, while for others it could be quite important.

- What happens in an emergency? Would the regular online therapist be available to help through a crisis or would things revert back to local resources?

- What about privacy and collaboration? Effective communication between a patient’s primary care clinician and their therapist can be crucial to good care, and asking the patient always to be the intermediary can be fraught with difficulty.

- How long is the contract? Just like those gym memberships, these companies bank on individuals who sign up but then don’t really use the service.

- What kind of training do the therapists at the site have? Is it possible to receive specific types of therapy, like CBT or parent training? Otherwise, pediatricians might be quite likely to hear back from the family wondering about medications after therapy “isn’t helping.”

Overall, mental health treatment delivered by telehealth is here to stay whether we like it or not. For some families, it is likely to provide new access to services not easily obtainable locally, while for others it could end up being a costly and ineffective enterprise. For families who use these services, a key challenge for pediatricians that may be important to overcome is finding a way for these clinicians to integrate into the overall medical team rather than being a detached island unto themselves.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. His book, “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows About the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021). Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

If you haven’t noticed yet, there has been an explosion of new online companies specializing in slicing off some little sliver of health care and leaving traditional medicine to take care of the rest of the patient. Lately, many of these startups involve mental health care, traditionally a difficult area to make profitable unless one caters just to the wealthy. Many pediatricians have been unsure exactly what to make of these new efforts. Are these the rescuers we’ve been waiting for to fill what seems like an enormous and growing unmet need? Are they just another means to extract money from desperate people and leave the real work to someone else? Something in-between? This article outlines some points to consider when evaluating this new frontier.

Case vignette

A 12-year-old girl presents with her parents for an annual exam. She has been struggling with her mood and anxiety over the past 2 years along with occasional superficial cutting. You have started treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and have recommended that she see a mental health professional but the parents report that one attempt with a therapist was a poor fit and nobody in the area seems to be accepting new patients. The parents state that they saw an advertisement on TV for a company that offers online psychotherapy by video appointments or text. They think this might be an option to pursue but are a little skeptical of the whole idea. They look for your opinion on this topic.

Most of these companies operate by having subscribers pay a monthly fee for different levels of services such as videoconference therapy sessions, supportive text messages, or even some psychopharmacological care. Many also offer the ability to switch rapidly between clinicians if you don’t like the one you have.

These arrangements sound great as the world grows increasingly comfortable with online communication and the mental health needs of children and adolescents increase with the seemingly endless COVID pandemic. Further, research generally finds that online mental health treatment is just as effective as services delivered in person, although the data on therapy by text are less robust.

Nevertheless, a lot of skepticism remains about online mental health treatment, particularly among those involved in more traditionally delivered mental health care. Some of the concerns that often get brought up include the following:

- Cost. Most of these online groups, especially the big national companies, don’t interact directly with insurance companies, leaving a lot of out-of-pocket expenses or the need for families to work things out directly with their insurance provider.

- Care fragmentation. In many ways, the online mental health care surge seems at odds with the growing “integrated care” movement that is trying to embed more behavioral care within primary care practices. From this lens, outsourcing someone’s mental health treatment to a therapist across the country that the patient has never actually met seems like a step in the wrong direction. Further, concerns arise about how much these folks will know about local resources in the community.

- The corporate model in mental health care. While being able to shop for a therapist like you would for a pillow sounds great on the surface, there are many times where a patient may need to be supportively confronted by their therapist or told no when asking about things like certain medications. The “customer is always right” principle often falls short when it comes to good mental health treatment.

- Depth and type of treatment. It is probably fair to say that most online therapy could be described as supportive psychotherapy. This type of therapy can be quite helpful for many but may lack the depth or specific techniques that some people need. For youth, some of the most effective types of psychotherapy, like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), can be harder to find, and implement, online.

- Emergencies. While many online companies claim to offer round-the-clock support for paying customers, they can quickly punt to “call your doctor” or even “call 911” if there is any real mental health crisis.

Balancing these potential benefits and pitfalls of online therapy, here are a few questions your patients may want to consider before signing onto a long-term contract with an online therapy company.

- Would the online clinician have any knowledge of my community? In some cases, this may not matter that much, while for others it could be quite important.

- What happens in an emergency? Would the regular online therapist be available to help through a crisis or would things revert back to local resources?

- What about privacy and collaboration? Effective communication between a patient’s primary care clinician and their therapist can be crucial to good care, and asking the patient always to be the intermediary can be fraught with difficulty.

- How long is the contract? Just like those gym memberships, these companies bank on individuals who sign up but then don’t really use the service.

- What kind of training do the therapists at the site have? Is it possible to receive specific types of therapy, like CBT or parent training? Otherwise, pediatricians might be quite likely to hear back from the family wondering about medications after therapy “isn’t helping.”

Overall, mental health treatment delivered by telehealth is here to stay whether we like it or not. For some families, it is likely to provide new access to services not easily obtainable locally, while for others it could end up being a costly and ineffective enterprise. For families who use these services, a key challenge for pediatricians that may be important to overcome is finding a way for these clinicians to integrate into the overall medical team rather than being a detached island unto themselves.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. His book, “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows About the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021). Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Opioid overdoses tied to lasting cognitive impairment

Opioid overdoses usually aren’t fatal, but a new review of numerous studies, mostly case reports and case series, suggests that they can have long-lasting effects on cognition, possibly because of hypoxia resulting from respiratory depression.

Erin L. Winstanley, PhD, MA, and associates noted in the review that opioids cause about 80% of worldwide deaths from illicit drug use, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s provisional August 2021 number of more than 88,000 opioid-caused deaths in the United States is the highest ever recorded – a 27% increase over what was reported last December. That number suggests that the opioid epidemic continues to rage, but the study results also show that the neurological consequences of nonfatal overdoses are an important public health problem.

And that’s something that may be overlooked, according to Mark S. Gold, MD, who was not involved with the study and was asked to comment on the review, which was published in the Journal of Addiction Science.

“Assuming that an overdose has no effect on the brain, mood, and behavior is not supported by experience or the literature. He is a University of Florida, Gainesville, Emeritus Eminent Scholar, adjunct professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis, and a member of the clinical council of Washington University’s Public Health Institute.

A common pattern among patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) is that they undergo treatment with medication-assisted therapy (MAT), only to drop out of treatment and then repeat the treatment at a later date. That suggests that physicians should take a harder look at the limitations of MAT and other treatments, Dr. Gold said.

Although the review found some associations between neurocognitive deficits and opioid overdose, the authors point out that it is difficult to make direct comparisons because of biases and differences in methodology among the included studies. They were not able to reach conclusions about the prevalence of brain injuries following nonfatal opioid overdoses. Few included studies controlled for confounding factors that might contribute to or explain neurocognitive impairments, reported Dr. Winstanley, associate professor in the department of behavioral medicine and psychiatry at the University of West Virginia, Morgantown, and associates.

Still, distinct patterns emerged from the analysis of almost 3,500 subjects in 79 studies in 21 countries. Twenty-nine studies reported diagnoses of leukoencephalopathy, which affects white matter. Spongiform leukoencephalopathy is known to occur secondarily after exposure to a variety of toxic agents, including carbon monoxide poisoning and drugs of abuse. The damage can lead to erosion of higher cerebral function. The condition can occur from 2 to 180 days after a hypoxic brain injury, potentially complicating efforts to attribute it specifically to an opioid overdose. Amnestic syndrome was also reported in some studies. One study found that about 39% of people seeking buprenorphine treatment suffered from neurocognitive impairment.

Dr. Gold called the study’s findings novel and of public health importance. “Each overdose takes a toll on the body, and especially the brain,” he said.

Better documentation needed

The variability in symptoms, as well as their timing, present challenges to initial treatment, which often occur before a patient reaches the hospital. This is a vital window because the length of time of inadequate respiration because of opioid overdose is likely to predict the extent of brain injury. The duration of inadequate respiration may not be captured in electronic medical records, and emergency departments don’t typically collect toxicology information, which may lead health care providers to attribute neurocognitive impairments to ongoing drug use rather than an acute anoxic or hypoxic episode. Further neurocognitive damage may have a delayed onset, and better documentation of these events could help physicians determine whether those symptoms stem from the acute event.

Dr. Winstanley and associates called for more research, including prospective case-control studies to identify brain changes following opioid-related overdose.

The authors also suggested that physicians might want to consider screening patients who experience prolonged anoxia or hypoxia for neurocognitive impairments and brain injuries. Dr. Gold agreed.

“Clinicians working with OUD patients should take these data to heart and take a comprehensive history of previous overdoses, loss of consciousness, head trauma, and following up on the history with neuropsychological and other tests of brain function,” Dr. Gold said. “After an assessment, rehabilitation and treatment might then be more personalized and effective.”

Dr. Gold had no relevant financial disclosures.

Opioid overdoses usually aren’t fatal, but a new review of numerous studies, mostly case reports and case series, suggests that they can have long-lasting effects on cognition, possibly because of hypoxia resulting from respiratory depression.

Erin L. Winstanley, PhD, MA, and associates noted in the review that opioids cause about 80% of worldwide deaths from illicit drug use, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s provisional August 2021 number of more than 88,000 opioid-caused deaths in the United States is the highest ever recorded – a 27% increase over what was reported last December. That number suggests that the opioid epidemic continues to rage, but the study results also show that the neurological consequences of nonfatal overdoses are an important public health problem.

And that’s something that may be overlooked, according to Mark S. Gold, MD, who was not involved with the study and was asked to comment on the review, which was published in the Journal of Addiction Science.

“Assuming that an overdose has no effect on the brain, mood, and behavior is not supported by experience or the literature. He is a University of Florida, Gainesville, Emeritus Eminent Scholar, adjunct professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis, and a member of the clinical council of Washington University’s Public Health Institute.

A common pattern among patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) is that they undergo treatment with medication-assisted therapy (MAT), only to drop out of treatment and then repeat the treatment at a later date. That suggests that physicians should take a harder look at the limitations of MAT and other treatments, Dr. Gold said.

Although the review found some associations between neurocognitive deficits and opioid overdose, the authors point out that it is difficult to make direct comparisons because of biases and differences in methodology among the included studies. They were not able to reach conclusions about the prevalence of brain injuries following nonfatal opioid overdoses. Few included studies controlled for confounding factors that might contribute to or explain neurocognitive impairments, reported Dr. Winstanley, associate professor in the department of behavioral medicine and psychiatry at the University of West Virginia, Morgantown, and associates.

Still, distinct patterns emerged from the analysis of almost 3,500 subjects in 79 studies in 21 countries. Twenty-nine studies reported diagnoses of leukoencephalopathy, which affects white matter. Spongiform leukoencephalopathy is known to occur secondarily after exposure to a variety of toxic agents, including carbon monoxide poisoning and drugs of abuse. The damage can lead to erosion of higher cerebral function. The condition can occur from 2 to 180 days after a hypoxic brain injury, potentially complicating efforts to attribute it specifically to an opioid overdose. Amnestic syndrome was also reported in some studies. One study found that about 39% of people seeking buprenorphine treatment suffered from neurocognitive impairment.

Dr. Gold called the study’s findings novel and of public health importance. “Each overdose takes a toll on the body, and especially the brain,” he said.

Better documentation needed

The variability in symptoms, as well as their timing, present challenges to initial treatment, which often occur before a patient reaches the hospital. This is a vital window because the length of time of inadequate respiration because of opioid overdose is likely to predict the extent of brain injury. The duration of inadequate respiration may not be captured in electronic medical records, and emergency departments don’t typically collect toxicology information, which may lead health care providers to attribute neurocognitive impairments to ongoing drug use rather than an acute anoxic or hypoxic episode. Further neurocognitive damage may have a delayed onset, and better documentation of these events could help physicians determine whether those symptoms stem from the acute event.

Dr. Winstanley and associates called for more research, including prospective case-control studies to identify brain changes following opioid-related overdose.

The authors also suggested that physicians might want to consider screening patients who experience prolonged anoxia or hypoxia for neurocognitive impairments and brain injuries. Dr. Gold agreed.

“Clinicians working with OUD patients should take these data to heart and take a comprehensive history of previous overdoses, loss of consciousness, head trauma, and following up on the history with neuropsychological and other tests of brain function,” Dr. Gold said. “After an assessment, rehabilitation and treatment might then be more personalized and effective.”

Dr. Gold had no relevant financial disclosures.

Opioid overdoses usually aren’t fatal, but a new review of numerous studies, mostly case reports and case series, suggests that they can have long-lasting effects on cognition, possibly because of hypoxia resulting from respiratory depression.

Erin L. Winstanley, PhD, MA, and associates noted in the review that opioids cause about 80% of worldwide deaths from illicit drug use, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s provisional August 2021 number of more than 88,000 opioid-caused deaths in the United States is the highest ever recorded – a 27% increase over what was reported last December. That number suggests that the opioid epidemic continues to rage, but the study results also show that the neurological consequences of nonfatal overdoses are an important public health problem.

And that’s something that may be overlooked, according to Mark S. Gold, MD, who was not involved with the study and was asked to comment on the review, which was published in the Journal of Addiction Science.

“Assuming that an overdose has no effect on the brain, mood, and behavior is not supported by experience or the literature. He is a University of Florida, Gainesville, Emeritus Eminent Scholar, adjunct professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis, and a member of the clinical council of Washington University’s Public Health Institute.

A common pattern among patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) is that they undergo treatment with medication-assisted therapy (MAT), only to drop out of treatment and then repeat the treatment at a later date. That suggests that physicians should take a harder look at the limitations of MAT and other treatments, Dr. Gold said.

Although the review found some associations between neurocognitive deficits and opioid overdose, the authors point out that it is difficult to make direct comparisons because of biases and differences in methodology among the included studies. They were not able to reach conclusions about the prevalence of brain injuries following nonfatal opioid overdoses. Few included studies controlled for confounding factors that might contribute to or explain neurocognitive impairments, reported Dr. Winstanley, associate professor in the department of behavioral medicine and psychiatry at the University of West Virginia, Morgantown, and associates.

Still, distinct patterns emerged from the analysis of almost 3,500 subjects in 79 studies in 21 countries. Twenty-nine studies reported diagnoses of leukoencephalopathy, which affects white matter. Spongiform leukoencephalopathy is known to occur secondarily after exposure to a variety of toxic agents, including carbon monoxide poisoning and drugs of abuse. The damage can lead to erosion of higher cerebral function. The condition can occur from 2 to 180 days after a hypoxic brain injury, potentially complicating efforts to attribute it specifically to an opioid overdose. Amnestic syndrome was also reported in some studies. One study found that about 39% of people seeking buprenorphine treatment suffered from neurocognitive impairment.

Dr. Gold called the study’s findings novel and of public health importance. “Each overdose takes a toll on the body, and especially the brain,” he said.

Better documentation needed

The variability in symptoms, as well as their timing, present challenges to initial treatment, which often occur before a patient reaches the hospital. This is a vital window because the length of time of inadequate respiration because of opioid overdose is likely to predict the extent of brain injury. The duration of inadequate respiration may not be captured in electronic medical records, and emergency departments don’t typically collect toxicology information, which may lead health care providers to attribute neurocognitive impairments to ongoing drug use rather than an acute anoxic or hypoxic episode. Further neurocognitive damage may have a delayed onset, and better documentation of these events could help physicians determine whether those symptoms stem from the acute event.

Dr. Winstanley and associates called for more research, including prospective case-control studies to identify brain changes following opioid-related overdose.

The authors also suggested that physicians might want to consider screening patients who experience prolonged anoxia or hypoxia for neurocognitive impairments and brain injuries. Dr. Gold agreed.

“Clinicians working with OUD patients should take these data to heart and take a comprehensive history of previous overdoses, loss of consciousness, head trauma, and following up on the history with neuropsychological and other tests of brain function,” Dr. Gold said. “After an assessment, rehabilitation and treatment might then be more personalized and effective.”

Dr. Gold had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ADDICTION SCIENCE

The role of probiotics in mental health

In 1950, at Staten Island’s Sea View Hospital, a group of patients with terminal tuberculosis were given a new antibiotic called isoniazid, which caused some unexpected side effects. The patients reported euphoria, mental stimulation, and improved sleep, and even began socializing with more vigor. The press was all over the case, writing about the sick “dancing in the halls tho’ they had holes in their lungs.” Soon doctors started prescribing isoniazid as the first-ever antidepressant.

The Sea View Hospital experiment was an early hint that changing the composition of the gut microbiome – in this case, via antibiotics – might affect our mental health. Yet only in the last 2 decades has research into connections between what we ingest and psychiatric disorders really taken off. In 2004, a landmark study showed that germ-free mice (born in such sterile conditions that they lacked a microbiome) had an exaggerated stress response. The effects were reversed, however, if the mice were fed a bacterial strain, Bifidobacterium infantis, a probiotic. This sparked academic interest, and thousands of research papers followed.

According to Stephen Ilardi, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, focusing on the etiology and treatment of depression, now is the “time of exciting discovery” in the field of probiotics and psychiatric disorders, although, admittedly, a lot still remains unknown.

Gut microbiome profiles in mental health disorders

We humans have about 100 trillion microbes residing in our guts. Some of these are archaea, some fungi, some protozoans and even viruses, but most are bacteria. Things like diet, sleep, and stress can all impact the composition of our gut microbiome. When the microbiome differs considerably from the typical, doctors and researchers describe it as dysbiosis, or imbalance. Studies have uncovered dysbiosis in patients with depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

“I think there is now pretty good evidence that the gut microbiome is actually an important factor in a number of psychiatric disorders,” says Allan Young, MBChB, clinical psychiatrist at King’s College London. The gut microbiome composition does seem to differ between psychiatric patients and the healthy. In depression, for example, a recent review of nine studies found an increase on the genus level in Streptococcus and Oscillibacter and low abundance of Lactobacillus and Coprococcus, among others. In generalized anxiety disorder, meanwhile, there appears to be an increase in Fusobacteria and Escherichia/Shigella .

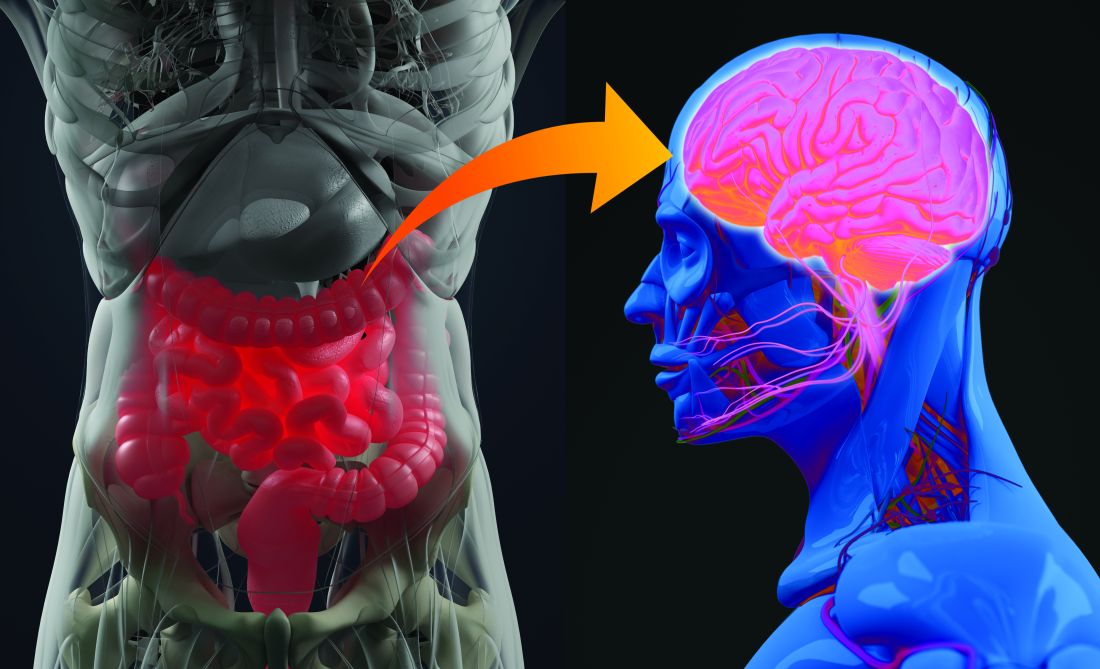

For Dr. Ilardi, the next important question is whether there are plausible mechanisms that could explain how gut microbiota may influence brain function. And, it appears there are.

“The microbes in the gut can release neurotransmitters into blood that cross into the brain and influence brain function. They can release hormones into the blood that again cross into the brain. They’ve got a lot of tricks up their sleeve,” he says.

One particularly important pathway runs through the vagus nerve – the longest nerve that emerges directly from the brain, connecting it to the gut. Another is the immune pathway. Gut bacteria can interact with immune cells and reduce cytokine production, which in turn can reduce systemic inflammation. Inflammatory processes have been implicated in both depression and bipolar disorder. What’s more, gut microbes can upregulate the expression of a protein called BDNF – brain-derived neurotrophic factor – which helps the development and survival of nerve cells in the brain.

Probiotics’ promise varies for different conditions

As the pathways by which gut dysbiosis may influence psychiatric disorders become clearer, the next logical step is to try to influence the composition of the microbiome to prevent and treat depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia. That’s where probiotics come in.

The evidence for the effects of probiotics – live microorganisms which, when ingested in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit – so far is the strongest for depression, says Viktoriya Nikolova, MRes, MSc, a PhD student and researcher at King’s College London. In their 2021 meta-analysis of seven trials, Mr. Nikolova and colleagues revealed that probiotics can significantly reduce depressive symptoms after just 8 weeks. There was a caveat, however – the probiotics only worked when used in addition to an approved antidepressant. Another meta-analysis, published in 2018, also showed that probiotics, when compared with placebo, improve mood in people with depressive symptoms (here, no antidepressant treatment was necessary).

Roumen Milev, MD, PhD, a neuroscientist at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and coauthor of a review on probiotics and depression published in the Annals of General Psychiatry, warns, however, that the research is still in its infancy. “,” he says.

When it comes to using probiotics to relieve anxiety, “the evidence in the animal literature is really compelling,” says Dr. Ilardi. Human studies are less convincing, however, which Dr. Dr. Ilardi showed in his 2018 review and meta-analysis involving 743 animals and 1,527 humans. “Studies are small for the most part, and some of them aren’t terribly well conducted, and they often use very low doses of probiotics,” he says. One of the larger double-blind and placebo-controlled trials showed that supplementation with Lactobacillus plantarum helps reduce stress and anxiety, while the levels of proinflammatory cytokines go down. Another meta-analysis, published in June, revealed that, when it comes to reducing stress and anxiety in youth, the results are mixed.

Evidence of probiotics’ efficiency in schizophrenia is emerging, yet also limited. A 2019 review concluded that currently available results only “hint” at a possibility that probiotics could make a difference in schizophrenia. Similarly, a 2020 review summed up that the role of probiotics in bipolar disorder “remains unclear and underexplored.”

Better studies, remaining questions

Apart from small samples, one issue with research on probiotics is that they generally tend to use varied doses of different strains of bacteria, or even multistrain mixtures, making it tough to compare results. Although there are hundreds of species of bacteria in the human gut, only a few have been evaluated for their antidepressant or antianxiety effects.

“To make it even worse, it’s almost certainly the case that depending on a person’s actual genetics or maybe their epigenetics, a strain that is helpful for one person may not be helpful for another. There is almost certainly no one-size-fits-all probiotic formulation,” says Dr. Ilardi.

Another critical question that remains to be answered is that of potential side effects.

“Probiotics are often seen as food supplements, so they don’t follow under the same regulations as drugs would,” says Mr. Nikolova. “They don’t necessarily have to follow the pattern of drug trials in many countries, which means that the monitoring of side effects is not the requirement.”

That’s something that worries King’s College psychiatrist Young too. “If you are giving it to modulate how the brain works, you could potentially induce psychiatric symptoms or a psychiatric disorder. There could be allergic reactions. There could be lots of different things,” he says.

When you search the web for “probiotics,” chances are you will come across sites boasting amazing effects that such products can have on cardiovascular heath, the immune system, and yes, mental well-being. Many also sell various probiotic supplements “formulated” for your gut health or improved moods. However, many such commercially available strains have never been actually tested in clinical trials. What’s more, according to Kathrin Cohen Kadosh, PhD, a neuroscientist at University of Surrey (England), “it is not always clear whether the different strains actually reach the gut intact.”

For now, considering the limited research evidence, a safer bet is to try to improve gut health through consumption of fermented foods that naturally contain probiotics, such as miso, kefir, or sauerkraut. Alternatively, you could reach for prebiotics, such as foods containing fiber (prebiotics enhance the growth of beneficial gut microbes). This, Dr. Kadosh says, could be “a gentler way of improving gut health” than popping a pill. Whether an improved mental well-being might follow still remains to be seen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 1950, at Staten Island’s Sea View Hospital, a group of patients with terminal tuberculosis were given a new antibiotic called isoniazid, which caused some unexpected side effects. The patients reported euphoria, mental stimulation, and improved sleep, and even began socializing with more vigor. The press was all over the case, writing about the sick “dancing in the halls tho’ they had holes in their lungs.” Soon doctors started prescribing isoniazid as the first-ever antidepressant.

The Sea View Hospital experiment was an early hint that changing the composition of the gut microbiome – in this case, via antibiotics – might affect our mental health. Yet only in the last 2 decades has research into connections between what we ingest and psychiatric disorders really taken off. In 2004, a landmark study showed that germ-free mice (born in such sterile conditions that they lacked a microbiome) had an exaggerated stress response. The effects were reversed, however, if the mice were fed a bacterial strain, Bifidobacterium infantis, a probiotic. This sparked academic interest, and thousands of research papers followed.

According to Stephen Ilardi, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, focusing on the etiology and treatment of depression, now is the “time of exciting discovery” in the field of probiotics and psychiatric disorders, although, admittedly, a lot still remains unknown.

Gut microbiome profiles in mental health disorders

We humans have about 100 trillion microbes residing in our guts. Some of these are archaea, some fungi, some protozoans and even viruses, but most are bacteria. Things like diet, sleep, and stress can all impact the composition of our gut microbiome. When the microbiome differs considerably from the typical, doctors and researchers describe it as dysbiosis, or imbalance. Studies have uncovered dysbiosis in patients with depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

“I think there is now pretty good evidence that the gut microbiome is actually an important factor in a number of psychiatric disorders,” says Allan Young, MBChB, clinical psychiatrist at King’s College London. The gut microbiome composition does seem to differ between psychiatric patients and the healthy. In depression, for example, a recent review of nine studies found an increase on the genus level in Streptococcus and Oscillibacter and low abundance of Lactobacillus and Coprococcus, among others. In generalized anxiety disorder, meanwhile, there appears to be an increase in Fusobacteria and Escherichia/Shigella .

For Dr. Ilardi, the next important question is whether there are plausible mechanisms that could explain how gut microbiota may influence brain function. And, it appears there are.

“The microbes in the gut can release neurotransmitters into blood that cross into the brain and influence brain function. They can release hormones into the blood that again cross into the brain. They’ve got a lot of tricks up their sleeve,” he says.

One particularly important pathway runs through the vagus nerve – the longest nerve that emerges directly from the brain, connecting it to the gut. Another is the immune pathway. Gut bacteria can interact with immune cells and reduce cytokine production, which in turn can reduce systemic inflammation. Inflammatory processes have been implicated in both depression and bipolar disorder. What’s more, gut microbes can upregulate the expression of a protein called BDNF – brain-derived neurotrophic factor – which helps the development and survival of nerve cells in the brain.

Probiotics’ promise varies for different conditions

As the pathways by which gut dysbiosis may influence psychiatric disorders become clearer, the next logical step is to try to influence the composition of the microbiome to prevent and treat depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia. That’s where probiotics come in.

The evidence for the effects of probiotics – live microorganisms which, when ingested in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit – so far is the strongest for depression, says Viktoriya Nikolova, MRes, MSc, a PhD student and researcher at King’s College London. In their 2021 meta-analysis of seven trials, Mr. Nikolova and colleagues revealed that probiotics can significantly reduce depressive symptoms after just 8 weeks. There was a caveat, however – the probiotics only worked when used in addition to an approved antidepressant. Another meta-analysis, published in 2018, also showed that probiotics, when compared with placebo, improve mood in people with depressive symptoms (here, no antidepressant treatment was necessary).

Roumen Milev, MD, PhD, a neuroscientist at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and coauthor of a review on probiotics and depression published in the Annals of General Psychiatry, warns, however, that the research is still in its infancy. “,” he says.

When it comes to using probiotics to relieve anxiety, “the evidence in the animal literature is really compelling,” says Dr. Ilardi. Human studies are less convincing, however, which Dr. Dr. Ilardi showed in his 2018 review and meta-analysis involving 743 animals and 1,527 humans. “Studies are small for the most part, and some of them aren’t terribly well conducted, and they often use very low doses of probiotics,” he says. One of the larger double-blind and placebo-controlled trials showed that supplementation with Lactobacillus plantarum helps reduce stress and anxiety, while the levels of proinflammatory cytokines go down. Another meta-analysis, published in June, revealed that, when it comes to reducing stress and anxiety in youth, the results are mixed.

Evidence of probiotics’ efficiency in schizophrenia is emerging, yet also limited. A 2019 review concluded that currently available results only “hint” at a possibility that probiotics could make a difference in schizophrenia. Similarly, a 2020 review summed up that the role of probiotics in bipolar disorder “remains unclear and underexplored.”

Better studies, remaining questions

Apart from small samples, one issue with research on probiotics is that they generally tend to use varied doses of different strains of bacteria, or even multistrain mixtures, making it tough to compare results. Although there are hundreds of species of bacteria in the human gut, only a few have been evaluated for their antidepressant or antianxiety effects.

“To make it even worse, it’s almost certainly the case that depending on a person’s actual genetics or maybe their epigenetics, a strain that is helpful for one person may not be helpful for another. There is almost certainly no one-size-fits-all probiotic formulation,” says Dr. Ilardi.

Another critical question that remains to be answered is that of potential side effects.

“Probiotics are often seen as food supplements, so they don’t follow under the same regulations as drugs would,” says Mr. Nikolova. “They don’t necessarily have to follow the pattern of drug trials in many countries, which means that the monitoring of side effects is not the requirement.”

That’s something that worries King’s College psychiatrist Young too. “If you are giving it to modulate how the brain works, you could potentially induce psychiatric symptoms or a psychiatric disorder. There could be allergic reactions. There could be lots of different things,” he says.

When you search the web for “probiotics,” chances are you will come across sites boasting amazing effects that such products can have on cardiovascular heath, the immune system, and yes, mental well-being. Many also sell various probiotic supplements “formulated” for your gut health or improved moods. However, many such commercially available strains have never been actually tested in clinical trials. What’s more, according to Kathrin Cohen Kadosh, PhD, a neuroscientist at University of Surrey (England), “it is not always clear whether the different strains actually reach the gut intact.”

For now, considering the limited research evidence, a safer bet is to try to improve gut health through consumption of fermented foods that naturally contain probiotics, such as miso, kefir, or sauerkraut. Alternatively, you could reach for prebiotics, such as foods containing fiber (prebiotics enhance the growth of beneficial gut microbes). This, Dr. Kadosh says, could be “a gentler way of improving gut health” than popping a pill. Whether an improved mental well-being might follow still remains to be seen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 1950, at Staten Island’s Sea View Hospital, a group of patients with terminal tuberculosis were given a new antibiotic called isoniazid, which caused some unexpected side effects. The patients reported euphoria, mental stimulation, and improved sleep, and even began socializing with more vigor. The press was all over the case, writing about the sick “dancing in the halls tho’ they had holes in their lungs.” Soon doctors started prescribing isoniazid as the first-ever antidepressant.

The Sea View Hospital experiment was an early hint that changing the composition of the gut microbiome – in this case, via antibiotics – might affect our mental health. Yet only in the last 2 decades has research into connections between what we ingest and psychiatric disorders really taken off. In 2004, a landmark study showed that germ-free mice (born in such sterile conditions that they lacked a microbiome) had an exaggerated stress response. The effects were reversed, however, if the mice were fed a bacterial strain, Bifidobacterium infantis, a probiotic. This sparked academic interest, and thousands of research papers followed.

According to Stephen Ilardi, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, focusing on the etiology and treatment of depression, now is the “time of exciting discovery” in the field of probiotics and psychiatric disorders, although, admittedly, a lot still remains unknown.

Gut microbiome profiles in mental health disorders

We humans have about 100 trillion microbes residing in our guts. Some of these are archaea, some fungi, some protozoans and even viruses, but most are bacteria. Things like diet, sleep, and stress can all impact the composition of our gut microbiome. When the microbiome differs considerably from the typical, doctors and researchers describe it as dysbiosis, or imbalance. Studies have uncovered dysbiosis in patients with depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

“I think there is now pretty good evidence that the gut microbiome is actually an important factor in a number of psychiatric disorders,” says Allan Young, MBChB, clinical psychiatrist at King’s College London. The gut microbiome composition does seem to differ between psychiatric patients and the healthy. In depression, for example, a recent review of nine studies found an increase on the genus level in Streptococcus and Oscillibacter and low abundance of Lactobacillus and Coprococcus, among others. In generalized anxiety disorder, meanwhile, there appears to be an increase in Fusobacteria and Escherichia/Shigella .

For Dr. Ilardi, the next important question is whether there are plausible mechanisms that could explain how gut microbiota may influence brain function. And, it appears there are.

“The microbes in the gut can release neurotransmitters into blood that cross into the brain and influence brain function. They can release hormones into the blood that again cross into the brain. They’ve got a lot of tricks up their sleeve,” he says.

One particularly important pathway runs through the vagus nerve – the longest nerve that emerges directly from the brain, connecting it to the gut. Another is the immune pathway. Gut bacteria can interact with immune cells and reduce cytokine production, which in turn can reduce systemic inflammation. Inflammatory processes have been implicated in both depression and bipolar disorder. What’s more, gut microbes can upregulate the expression of a protein called BDNF – brain-derived neurotrophic factor – which helps the development and survival of nerve cells in the brain.

Probiotics’ promise varies for different conditions

As the pathways by which gut dysbiosis may influence psychiatric disorders become clearer, the next logical step is to try to influence the composition of the microbiome to prevent and treat depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia. That’s where probiotics come in.

The evidence for the effects of probiotics – live microorganisms which, when ingested in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit – so far is the strongest for depression, says Viktoriya Nikolova, MRes, MSc, a PhD student and researcher at King’s College London. In their 2021 meta-analysis of seven trials, Mr. Nikolova and colleagues revealed that probiotics can significantly reduce depressive symptoms after just 8 weeks. There was a caveat, however – the probiotics only worked when used in addition to an approved antidepressant. Another meta-analysis, published in 2018, also showed that probiotics, when compared with placebo, improve mood in people with depressive symptoms (here, no antidepressant treatment was necessary).

Roumen Milev, MD, PhD, a neuroscientist at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., and coauthor of a review on probiotics and depression published in the Annals of General Psychiatry, warns, however, that the research is still in its infancy. “,” he says.

When it comes to using probiotics to relieve anxiety, “the evidence in the animal literature is really compelling,” says Dr. Ilardi. Human studies are less convincing, however, which Dr. Dr. Ilardi showed in his 2018 review and meta-analysis involving 743 animals and 1,527 humans. “Studies are small for the most part, and some of them aren’t terribly well conducted, and they often use very low doses of probiotics,” he says. One of the larger double-blind and placebo-controlled trials showed that supplementation with Lactobacillus plantarum helps reduce stress and anxiety, while the levels of proinflammatory cytokines go down. Another meta-analysis, published in June, revealed that, when it comes to reducing stress and anxiety in youth, the results are mixed.

Evidence of probiotics’ efficiency in schizophrenia is emerging, yet also limited. A 2019 review concluded that currently available results only “hint” at a possibility that probiotics could make a difference in schizophrenia. Similarly, a 2020 review summed up that the role of probiotics in bipolar disorder “remains unclear and underexplored.”

Better studies, remaining questions

Apart from small samples, one issue with research on probiotics is that they generally tend to use varied doses of different strains of bacteria, or even multistrain mixtures, making it tough to compare results. Although there are hundreds of species of bacteria in the human gut, only a few have been evaluated for their antidepressant or antianxiety effects.

“To make it even worse, it’s almost certainly the case that depending on a person’s actual genetics or maybe their epigenetics, a strain that is helpful for one person may not be helpful for another. There is almost certainly no one-size-fits-all probiotic formulation,” says Dr. Ilardi.

Another critical question that remains to be answered is that of potential side effects.

“Probiotics are often seen as food supplements, so they don’t follow under the same regulations as drugs would,” says Mr. Nikolova. “They don’t necessarily have to follow the pattern of drug trials in many countries, which means that the monitoring of side effects is not the requirement.”

That’s something that worries King’s College psychiatrist Young too. “If you are giving it to modulate how the brain works, you could potentially induce psychiatric symptoms or a psychiatric disorder. There could be allergic reactions. There could be lots of different things,” he says.