User login

The Rise of Positive Psychiatry (and How Pediatrics Can Join the Effort)

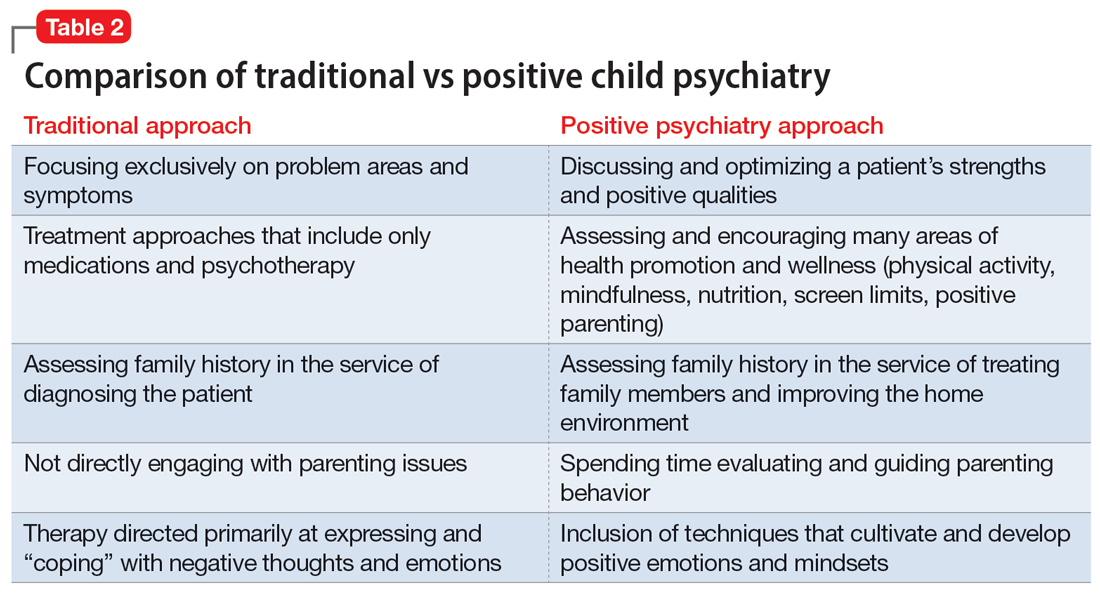

Psychiatry, like all medical disciplines, changes over time. For many decades, psychiatrists were primarily psychotherapists. As medications slowly became available, these became a second tool for treatment — so much so that by the 21st century many, if not most, psychiatrists saw themselves primarily as psychopharmacologists and diagnosticians who were skilled at identifying various forms of mental illness and using medications in the hopes of inducing a clinically meaningful “response” in symptoms. While still belonging to the umbrella category of a mental health professional, more and more psychiatrists trained and practiced as mental illness professionals.

Slowly, however, there have been stirrings within the field by many who have found the identity of the psychiatrist as a “prescriber” to be too narrow, and the current “med check” model of treatment too confining. This change was partly inspired by our colleagues in clinical psychology who were challenged in the 1990s by then American Psychological Association President Martin Seligman, PhD, to develop knowledge and expertise not only in alleviating mental suffering but also in promoting true mental well-being, a construct that still was often vaguely defined. One framework of well-being that was advanced at the time was the PERMA model, representing the five well-being dimensions of Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment.1

While there have always been those in psychiatry who have advocated for a broad emphasis that incorporates the full spectrum of mental health, there has been a surge of interest in the past 10-15 years, urging a focus on well-being and the tools that can help a person achieve it. This trend has variably been referred to as positive psychiatry, lifestyle psychiatry, and other terms.2 As one might expect, child and adolescent psychiatry has been particularly fertile ground for such principles, and models such as the Vermont Family Based Approach have expanded the concept beyond the individual to the family and even community.3

It is important to note here that embracing the concept of well-being in treatment does not in any way require one to abandon the idea that genetic or environmental factors can lead to negative outcomes in brain development, nor does it mandate that one leaves behind important treatment modalities such as traditional psychotherapy and medication treatment. Further, this approach should not be confused with some “wellness” activities that offer quick fixes and lack scientific rigor. Positive psychiatry does, however, offer a third pathway to advance positive emotional behavioral growth, namely through health promotion activities ranging from exercise to good nutrition to positive parenting in ways that have been shown to benefit both those who are already doing fairly well as well as those who are actively struggling with significant psychiatric disorders.4

Primary care clinicians already have extensive familiarity talking about these kinds of health promoting activities with families. That said, it’s been my observation from many years of doing consultations and reviewing notes that these conversations happen almost exclusively during well-check visits and can get forgotten when a child presents with emotional behavioral challenges.

So how can the primary care clinician who is interested in more fully incorporating the burgeoning science on well-being work these principles into routine practice? Here are three suggestions.

Ask Some New Questions

It’s difficult to treat things that aren’t assessed. To best incorporate true mental health within one’s work with families, it can be very helpful to expand the regular questions one asks to include those that address some of the PERMA and health promotion areas described above. Some examples could include the following:

- Hopes. What would a perfect life look like for you when you’re older?

- Connection. Is there anything that you just love doing, so much so that time sometimes just seems to go away?

- Strengths. What are you good at? What good things would your friends say about you?

- Parenting. What are you most proud of as a parent, and where are your biggest challenges?

- Nutrition. What does a typical school day breakfast look like for you?

- Screens. Do you have any restrictions related to what you do on screens?

- Sleep. Tell me about your typical bedtime routine.

Add Some New Interventions

Counseling and medications can be powerful ways to bring improvement in a child’s life, but thinking about health promotion opens up a whole new avenue for intervention. This domain includes areas like physical activity, nutrition, sleep practices, parenting, participation in music and the arts, practicing kindness towards others, and mindfulness, among others.

For someone newly diagnosed with ADHD, for example, consider expanding your treatment plan to include not only medications but also specific guidance to exercise more, limit screen usage, practice good bedtime routines, eat a real breakfast, and reduce the helicopter parenting. Monitor these areas over time.

Another example relates to common sleep problems. Before making that melatonin recommendation, ask yourself if you understand what is happening in that child’s environment at night. Are they allowed to play video games until 2 a.m.? Are they taking naps during the day because they have nothing to do? Are they downing caffeinated drinks with dinner? Does the child get zero physical activity outside of the PE class? Maybe you still will need the melatonin, but perhaps other areas need to be addressed first.

Find Some New Colleagues

While it can be challenging sometimes to find anyone in mental health who sees new patients, there is value is finding out the approach and methodology that psychiatric clinicians and therapists apply in their practice. Working collaboratively with those who value a well-being orientation and who can work productively with the whole family to increase health promotion can yield benefits for a patient’s long-term physical and mental health.

The renewed interest and attention on well-being and health promotion activities that can optimize brain growth are a welcome and overdue development in mental health treatment. Pediatricians and other primary care clinicians can be a critical part of this growing initiative by gaining knowledge about youth well-being, applying this knowledge in day-to-day practice, and working collaboratively with those who share a similar perspective.

Dr. Rettew is a child & adolescent psychiatrist and medical director of Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Oregon. He is on the psychiatry faculty at Oregon Health & Science University. You can follow him on Facebook and X @PediPsych. His latest book is Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.

References

1. Seligman, MEP. Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2011.

2. Jeste DV, Palmer BW. (Eds.). Positive psychiatry: a clinical handbook. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9781615370818.

3. Hudziak J, Ivanova MY. The Vermont family based approach: Family based health promotion, illness prevention, and intervention. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016 Apr;25(2):167-78. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2015.11.002.

4. Rettew DC. Incorporating positive psychiatry with children and adolescents. Current Psychiatry. 2022 November;21(11):12-16,45. doi: 10.12788/cp.0303.

Psychiatry, like all medical disciplines, changes over time. For many decades, psychiatrists were primarily psychotherapists. As medications slowly became available, these became a second tool for treatment — so much so that by the 21st century many, if not most, psychiatrists saw themselves primarily as psychopharmacologists and diagnosticians who were skilled at identifying various forms of mental illness and using medications in the hopes of inducing a clinically meaningful “response” in symptoms. While still belonging to the umbrella category of a mental health professional, more and more psychiatrists trained and practiced as mental illness professionals.

Slowly, however, there have been stirrings within the field by many who have found the identity of the psychiatrist as a “prescriber” to be too narrow, and the current “med check” model of treatment too confining. This change was partly inspired by our colleagues in clinical psychology who were challenged in the 1990s by then American Psychological Association President Martin Seligman, PhD, to develop knowledge and expertise not only in alleviating mental suffering but also in promoting true mental well-being, a construct that still was often vaguely defined. One framework of well-being that was advanced at the time was the PERMA model, representing the five well-being dimensions of Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment.1

While there have always been those in psychiatry who have advocated for a broad emphasis that incorporates the full spectrum of mental health, there has been a surge of interest in the past 10-15 years, urging a focus on well-being and the tools that can help a person achieve it. This trend has variably been referred to as positive psychiatry, lifestyle psychiatry, and other terms.2 As one might expect, child and adolescent psychiatry has been particularly fertile ground for such principles, and models such as the Vermont Family Based Approach have expanded the concept beyond the individual to the family and even community.3

It is important to note here that embracing the concept of well-being in treatment does not in any way require one to abandon the idea that genetic or environmental factors can lead to negative outcomes in brain development, nor does it mandate that one leaves behind important treatment modalities such as traditional psychotherapy and medication treatment. Further, this approach should not be confused with some “wellness” activities that offer quick fixes and lack scientific rigor. Positive psychiatry does, however, offer a third pathway to advance positive emotional behavioral growth, namely through health promotion activities ranging from exercise to good nutrition to positive parenting in ways that have been shown to benefit both those who are already doing fairly well as well as those who are actively struggling with significant psychiatric disorders.4

Primary care clinicians already have extensive familiarity talking about these kinds of health promoting activities with families. That said, it’s been my observation from many years of doing consultations and reviewing notes that these conversations happen almost exclusively during well-check visits and can get forgotten when a child presents with emotional behavioral challenges.

So how can the primary care clinician who is interested in more fully incorporating the burgeoning science on well-being work these principles into routine practice? Here are three suggestions.

Ask Some New Questions

It’s difficult to treat things that aren’t assessed. To best incorporate true mental health within one’s work with families, it can be very helpful to expand the regular questions one asks to include those that address some of the PERMA and health promotion areas described above. Some examples could include the following:

- Hopes. What would a perfect life look like for you when you’re older?

- Connection. Is there anything that you just love doing, so much so that time sometimes just seems to go away?

- Strengths. What are you good at? What good things would your friends say about you?

- Parenting. What are you most proud of as a parent, and where are your biggest challenges?

- Nutrition. What does a typical school day breakfast look like for you?

- Screens. Do you have any restrictions related to what you do on screens?

- Sleep. Tell me about your typical bedtime routine.

Add Some New Interventions

Counseling and medications can be powerful ways to bring improvement in a child’s life, but thinking about health promotion opens up a whole new avenue for intervention. This domain includes areas like physical activity, nutrition, sleep practices, parenting, participation in music and the arts, practicing kindness towards others, and mindfulness, among others.

For someone newly diagnosed with ADHD, for example, consider expanding your treatment plan to include not only medications but also specific guidance to exercise more, limit screen usage, practice good bedtime routines, eat a real breakfast, and reduce the helicopter parenting. Monitor these areas over time.

Another example relates to common sleep problems. Before making that melatonin recommendation, ask yourself if you understand what is happening in that child’s environment at night. Are they allowed to play video games until 2 a.m.? Are they taking naps during the day because they have nothing to do? Are they downing caffeinated drinks with dinner? Does the child get zero physical activity outside of the PE class? Maybe you still will need the melatonin, but perhaps other areas need to be addressed first.

Find Some New Colleagues

While it can be challenging sometimes to find anyone in mental health who sees new patients, there is value is finding out the approach and methodology that psychiatric clinicians and therapists apply in their practice. Working collaboratively with those who value a well-being orientation and who can work productively with the whole family to increase health promotion can yield benefits for a patient’s long-term physical and mental health.

The renewed interest and attention on well-being and health promotion activities that can optimize brain growth are a welcome and overdue development in mental health treatment. Pediatricians and other primary care clinicians can be a critical part of this growing initiative by gaining knowledge about youth well-being, applying this knowledge in day-to-day practice, and working collaboratively with those who share a similar perspective.

Dr. Rettew is a child & adolescent psychiatrist and medical director of Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Oregon. He is on the psychiatry faculty at Oregon Health & Science University. You can follow him on Facebook and X @PediPsych. His latest book is Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.

References

1. Seligman, MEP. Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2011.

2. Jeste DV, Palmer BW. (Eds.). Positive psychiatry: a clinical handbook. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9781615370818.

3. Hudziak J, Ivanova MY. The Vermont family based approach: Family based health promotion, illness prevention, and intervention. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016 Apr;25(2):167-78. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2015.11.002.

4. Rettew DC. Incorporating positive psychiatry with children and adolescents. Current Psychiatry. 2022 November;21(11):12-16,45. doi: 10.12788/cp.0303.

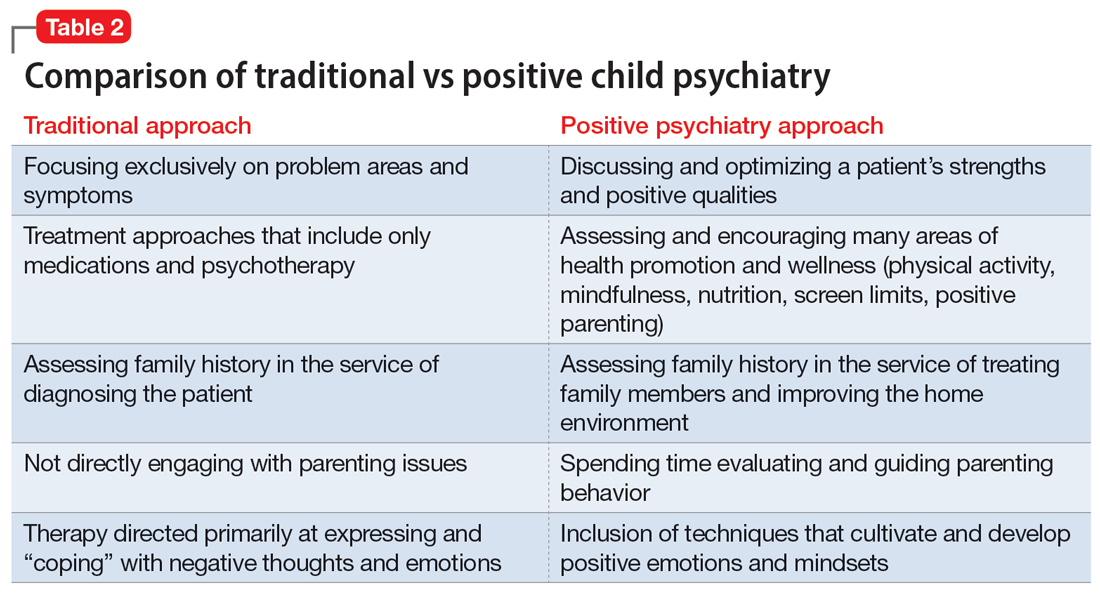

Psychiatry, like all medical disciplines, changes over time. For many decades, psychiatrists were primarily psychotherapists. As medications slowly became available, these became a second tool for treatment — so much so that by the 21st century many, if not most, psychiatrists saw themselves primarily as psychopharmacologists and diagnosticians who were skilled at identifying various forms of mental illness and using medications in the hopes of inducing a clinically meaningful “response” in symptoms. While still belonging to the umbrella category of a mental health professional, more and more psychiatrists trained and practiced as mental illness professionals.

Slowly, however, there have been stirrings within the field by many who have found the identity of the psychiatrist as a “prescriber” to be too narrow, and the current “med check” model of treatment too confining. This change was partly inspired by our colleagues in clinical psychology who were challenged in the 1990s by then American Psychological Association President Martin Seligman, PhD, to develop knowledge and expertise not only in alleviating mental suffering but also in promoting true mental well-being, a construct that still was often vaguely defined. One framework of well-being that was advanced at the time was the PERMA model, representing the five well-being dimensions of Positive emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment.1

While there have always been those in psychiatry who have advocated for a broad emphasis that incorporates the full spectrum of mental health, there has been a surge of interest in the past 10-15 years, urging a focus on well-being and the tools that can help a person achieve it. This trend has variably been referred to as positive psychiatry, lifestyle psychiatry, and other terms.2 As one might expect, child and adolescent psychiatry has been particularly fertile ground for such principles, and models such as the Vermont Family Based Approach have expanded the concept beyond the individual to the family and even community.3

It is important to note here that embracing the concept of well-being in treatment does not in any way require one to abandon the idea that genetic or environmental factors can lead to negative outcomes in brain development, nor does it mandate that one leaves behind important treatment modalities such as traditional psychotherapy and medication treatment. Further, this approach should not be confused with some “wellness” activities that offer quick fixes and lack scientific rigor. Positive psychiatry does, however, offer a third pathway to advance positive emotional behavioral growth, namely through health promotion activities ranging from exercise to good nutrition to positive parenting in ways that have been shown to benefit both those who are already doing fairly well as well as those who are actively struggling with significant psychiatric disorders.4

Primary care clinicians already have extensive familiarity talking about these kinds of health promoting activities with families. That said, it’s been my observation from many years of doing consultations and reviewing notes that these conversations happen almost exclusively during well-check visits and can get forgotten when a child presents with emotional behavioral challenges.

So how can the primary care clinician who is interested in more fully incorporating the burgeoning science on well-being work these principles into routine practice? Here are three suggestions.

Ask Some New Questions

It’s difficult to treat things that aren’t assessed. To best incorporate true mental health within one’s work with families, it can be very helpful to expand the regular questions one asks to include those that address some of the PERMA and health promotion areas described above. Some examples could include the following:

- Hopes. What would a perfect life look like for you when you’re older?

- Connection. Is there anything that you just love doing, so much so that time sometimes just seems to go away?

- Strengths. What are you good at? What good things would your friends say about you?

- Parenting. What are you most proud of as a parent, and where are your biggest challenges?

- Nutrition. What does a typical school day breakfast look like for you?

- Screens. Do you have any restrictions related to what you do on screens?

- Sleep. Tell me about your typical bedtime routine.

Add Some New Interventions

Counseling and medications can be powerful ways to bring improvement in a child’s life, but thinking about health promotion opens up a whole new avenue for intervention. This domain includes areas like physical activity, nutrition, sleep practices, parenting, participation in music and the arts, practicing kindness towards others, and mindfulness, among others.

For someone newly diagnosed with ADHD, for example, consider expanding your treatment plan to include not only medications but also specific guidance to exercise more, limit screen usage, practice good bedtime routines, eat a real breakfast, and reduce the helicopter parenting. Monitor these areas over time.

Another example relates to common sleep problems. Before making that melatonin recommendation, ask yourself if you understand what is happening in that child’s environment at night. Are they allowed to play video games until 2 a.m.? Are they taking naps during the day because they have nothing to do? Are they downing caffeinated drinks with dinner? Does the child get zero physical activity outside of the PE class? Maybe you still will need the melatonin, but perhaps other areas need to be addressed first.

Find Some New Colleagues

While it can be challenging sometimes to find anyone in mental health who sees new patients, there is value is finding out the approach and methodology that psychiatric clinicians and therapists apply in their practice. Working collaboratively with those who value a well-being orientation and who can work productively with the whole family to increase health promotion can yield benefits for a patient’s long-term physical and mental health.

The renewed interest and attention on well-being and health promotion activities that can optimize brain growth are a welcome and overdue development in mental health treatment. Pediatricians and other primary care clinicians can be a critical part of this growing initiative by gaining knowledge about youth well-being, applying this knowledge in day-to-day practice, and working collaboratively with those who share a similar perspective.

Dr. Rettew is a child & adolescent psychiatrist and medical director of Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Oregon. He is on the psychiatry faculty at Oregon Health & Science University. You can follow him on Facebook and X @PediPsych. His latest book is Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.

References

1. Seligman, MEP. Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2011.

2. Jeste DV, Palmer BW. (Eds.). Positive psychiatry: a clinical handbook. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9781615370818.

3. Hudziak J, Ivanova MY. The Vermont family based approach: Family based health promotion, illness prevention, and intervention. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016 Apr;25(2):167-78. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2015.11.002.

4. Rettew DC. Incorporating positive psychiatry with children and adolescents. Current Psychiatry. 2022 November;21(11):12-16,45. doi: 10.12788/cp.0303.

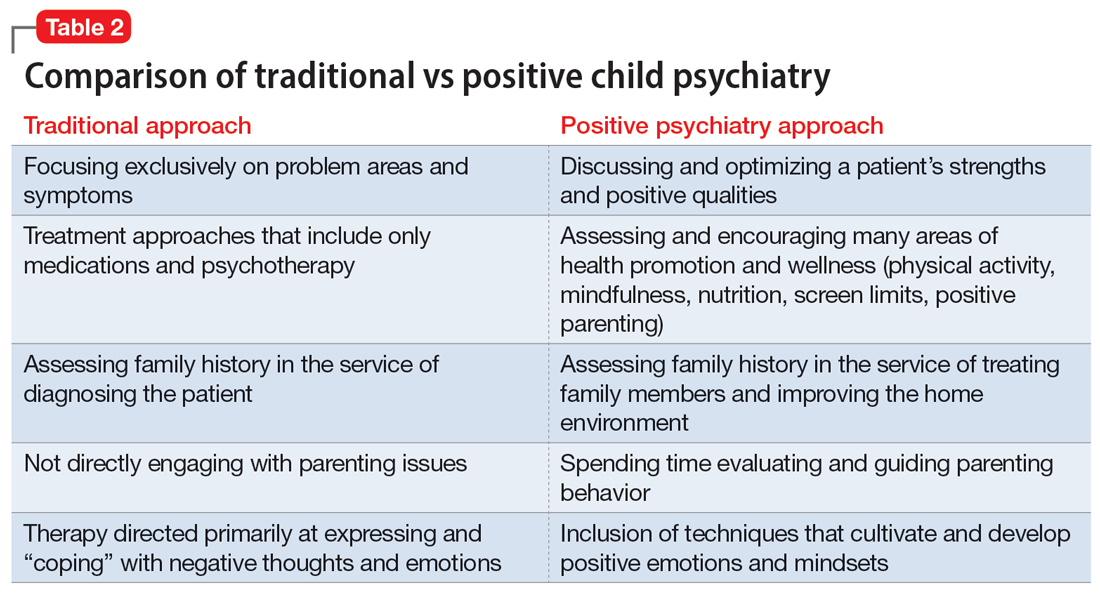

Just gas? New study on colic suggests some longer-term implications

Pediatricians commonly are asked to see infants presenting with symptoms of colic. The frequent and intense crying associated with colic is understandably quite distressing to parents, who often worry about a serious underlying medical cause. There also is the stress of trying to soothe an irritable infant who often does not seem to respond to the typical interventions.

Conventional wisdom about colic has been that the behaviors are the result of some gastrointestinal problem that, while not perfectly understood, tends to be mercifully self-limited and not predictive of future medical or mental health problems. This perspective then leads to pediatricians typically offering mainly sympathy and reassurance at these visits.

A new study,1 however, challenges some of this traditional thinking. The data come from a remarkable longitudinal study called the Generation R Study (R being Rotterdam in the Netherlands) that has prospectively studied a group of nearly 5,000 children from before birth into adolescence. Colic symptoms were briefly assessed when infants were about 3 months old and emotional-behavioral problems have been prospectively measured at multiple time points subsequently using well-validated rating scales.

The main finding of the study was and, to a lesser extent, in adolescence. This held for both internalizing problems (like anxiety and depressive symptoms) and externalizing problems (like defiance and aggressive behavior). At age 10, participants also underwent an MRI scan and those who were excessive criers as infants were found to have a smaller amygdala, a region known for being important in regulating emotions.

The authors concluded that colicky behavior in infancy may reflect some underlying temperamental vulnerabilities and may have more predictive value than previously thought. The connection between excessive crying and a measurable brain region difference later in life is also interesting, although these kinds of brain imaging findings have been notoriously difficult to interpret clinically.

Overall, this is a solid study that deserves to be considered. Colic may reflect a bit more than most of us have been taught and shouldn’t necessarily be “shrugged off,” as the authors state in their discussion.

At the same time, however, it is important not to overinterpret the findings. The magnitude of the effects were on the small side (about 0.2 of a standard deviation) and most children with excessive crying in early infancy did not manifest high levels of mental health problems later in life. The mothers of high crying infants also had slightly higher levels of mental health problems themselves so there could be other mechanisms at work here, such as genetic differences between the two groups.

So how could a pediatrician best use this new information without taking things too far? Regardless of the question of whether the excessive crying infancy is a true risk factor for later behavior problems (in the causal sense) or whether it represents more of a marker for something else, its presence so early in life offers an opportunity. Primary care clinicians would still likely want to provide the reassurance that has typically been given in these visits but perhaps with the caveat that some of these kids go on to struggle a bit more with mental health and that they might benefit from some additional support. We are not talking about prophylactic medications here, but something like additional parenting skills. Especially if you, as the pediatrician, suspect that the parents might benefit from expanding their parenting toolkit already, here is a nice opportunity to invite them to learn some new approaches and skills — framed in a way that focuses on the temperament of the child rather than any “deficits” you perceive in the parents. Some parents may be more receptive and less defensive to the idea of participating in parent training under the framework that they are doing this because they have a temperamentally more challenging child (rather than feeling that they are deficient in basic parenting skills).

It’s always a good idea to know about what resources are available in the community when it comes to teaching parenting skills. In addition to scientifically supported books and podcasts, there has been a steady increase in reliable websites, apps, and other digital platforms related to parenting, as well as standard in-person groups and classes. This could also be a great use of an integrated behavioral health professional for practices fortunate enough to have one.

In summary, there is some new evidence that colic can represent a little more than “just gas,” and while we shouldn’t take this one study to the extreme, there may be some good opportunities here to discuss and support good parenting practices in general.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His latest book is “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.” You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

Reference

1. Sammallahti S et al. Excessive crying, behavior problems, and amygdala volume: A study from infancy to adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023 Jun;62(6):675-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2023.01.014.

Pediatricians commonly are asked to see infants presenting with symptoms of colic. The frequent and intense crying associated with colic is understandably quite distressing to parents, who often worry about a serious underlying medical cause. There also is the stress of trying to soothe an irritable infant who often does not seem to respond to the typical interventions.

Conventional wisdom about colic has been that the behaviors are the result of some gastrointestinal problem that, while not perfectly understood, tends to be mercifully self-limited and not predictive of future medical or mental health problems. This perspective then leads to pediatricians typically offering mainly sympathy and reassurance at these visits.

A new study,1 however, challenges some of this traditional thinking. The data come from a remarkable longitudinal study called the Generation R Study (R being Rotterdam in the Netherlands) that has prospectively studied a group of nearly 5,000 children from before birth into adolescence. Colic symptoms were briefly assessed when infants were about 3 months old and emotional-behavioral problems have been prospectively measured at multiple time points subsequently using well-validated rating scales.

The main finding of the study was and, to a lesser extent, in adolescence. This held for both internalizing problems (like anxiety and depressive symptoms) and externalizing problems (like defiance and aggressive behavior). At age 10, participants also underwent an MRI scan and those who were excessive criers as infants were found to have a smaller amygdala, a region known for being important in regulating emotions.

The authors concluded that colicky behavior in infancy may reflect some underlying temperamental vulnerabilities and may have more predictive value than previously thought. The connection between excessive crying and a measurable brain region difference later in life is also interesting, although these kinds of brain imaging findings have been notoriously difficult to interpret clinically.

Overall, this is a solid study that deserves to be considered. Colic may reflect a bit more than most of us have been taught and shouldn’t necessarily be “shrugged off,” as the authors state in their discussion.

At the same time, however, it is important not to overinterpret the findings. The magnitude of the effects were on the small side (about 0.2 of a standard deviation) and most children with excessive crying in early infancy did not manifest high levels of mental health problems later in life. The mothers of high crying infants also had slightly higher levels of mental health problems themselves so there could be other mechanisms at work here, such as genetic differences between the two groups.

So how could a pediatrician best use this new information without taking things too far? Regardless of the question of whether the excessive crying infancy is a true risk factor for later behavior problems (in the causal sense) or whether it represents more of a marker for something else, its presence so early in life offers an opportunity. Primary care clinicians would still likely want to provide the reassurance that has typically been given in these visits but perhaps with the caveat that some of these kids go on to struggle a bit more with mental health and that they might benefit from some additional support. We are not talking about prophylactic medications here, but something like additional parenting skills. Especially if you, as the pediatrician, suspect that the parents might benefit from expanding their parenting toolkit already, here is a nice opportunity to invite them to learn some new approaches and skills — framed in a way that focuses on the temperament of the child rather than any “deficits” you perceive in the parents. Some parents may be more receptive and less defensive to the idea of participating in parent training under the framework that they are doing this because they have a temperamentally more challenging child (rather than feeling that they are deficient in basic parenting skills).

It’s always a good idea to know about what resources are available in the community when it comes to teaching parenting skills. In addition to scientifically supported books and podcasts, there has been a steady increase in reliable websites, apps, and other digital platforms related to parenting, as well as standard in-person groups and classes. This could also be a great use of an integrated behavioral health professional for practices fortunate enough to have one.

In summary, there is some new evidence that colic can represent a little more than “just gas,” and while we shouldn’t take this one study to the extreme, there may be some good opportunities here to discuss and support good parenting practices in general.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His latest book is “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.” You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

Reference

1. Sammallahti S et al. Excessive crying, behavior problems, and amygdala volume: A study from infancy to adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023 Jun;62(6):675-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2023.01.014.

Pediatricians commonly are asked to see infants presenting with symptoms of colic. The frequent and intense crying associated with colic is understandably quite distressing to parents, who often worry about a serious underlying medical cause. There also is the stress of trying to soothe an irritable infant who often does not seem to respond to the typical interventions.

Conventional wisdom about colic has been that the behaviors are the result of some gastrointestinal problem that, while not perfectly understood, tends to be mercifully self-limited and not predictive of future medical or mental health problems. This perspective then leads to pediatricians typically offering mainly sympathy and reassurance at these visits.

A new study,1 however, challenges some of this traditional thinking. The data come from a remarkable longitudinal study called the Generation R Study (R being Rotterdam in the Netherlands) that has prospectively studied a group of nearly 5,000 children from before birth into adolescence. Colic symptoms were briefly assessed when infants were about 3 months old and emotional-behavioral problems have been prospectively measured at multiple time points subsequently using well-validated rating scales.

The main finding of the study was and, to a lesser extent, in adolescence. This held for both internalizing problems (like anxiety and depressive symptoms) and externalizing problems (like defiance and aggressive behavior). At age 10, participants also underwent an MRI scan and those who were excessive criers as infants were found to have a smaller amygdala, a region known for being important in regulating emotions.

The authors concluded that colicky behavior in infancy may reflect some underlying temperamental vulnerabilities and may have more predictive value than previously thought. The connection between excessive crying and a measurable brain region difference later in life is also interesting, although these kinds of brain imaging findings have been notoriously difficult to interpret clinically.

Overall, this is a solid study that deserves to be considered. Colic may reflect a bit more than most of us have been taught and shouldn’t necessarily be “shrugged off,” as the authors state in their discussion.

At the same time, however, it is important not to overinterpret the findings. The magnitude of the effects were on the small side (about 0.2 of a standard deviation) and most children with excessive crying in early infancy did not manifest high levels of mental health problems later in life. The mothers of high crying infants also had slightly higher levels of mental health problems themselves so there could be other mechanisms at work here, such as genetic differences between the two groups.

So how could a pediatrician best use this new information without taking things too far? Regardless of the question of whether the excessive crying infancy is a true risk factor for later behavior problems (in the causal sense) or whether it represents more of a marker for something else, its presence so early in life offers an opportunity. Primary care clinicians would still likely want to provide the reassurance that has typically been given in these visits but perhaps with the caveat that some of these kids go on to struggle a bit more with mental health and that they might benefit from some additional support. We are not talking about prophylactic medications here, but something like additional parenting skills. Especially if you, as the pediatrician, suspect that the parents might benefit from expanding their parenting toolkit already, here is a nice opportunity to invite them to learn some new approaches and skills — framed in a way that focuses on the temperament of the child rather than any “deficits” you perceive in the parents. Some parents may be more receptive and less defensive to the idea of participating in parent training under the framework that they are doing this because they have a temperamentally more challenging child (rather than feeling that they are deficient in basic parenting skills).

It’s always a good idea to know about what resources are available in the community when it comes to teaching parenting skills. In addition to scientifically supported books and podcasts, there has been a steady increase in reliable websites, apps, and other digital platforms related to parenting, as well as standard in-person groups and classes. This could also be a great use of an integrated behavioral health professional for practices fortunate enough to have one.

In summary, there is some new evidence that colic can represent a little more than “just gas,” and while we shouldn’t take this one study to the extreme, there may be some good opportunities here to discuss and support good parenting practices in general.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His latest book is “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.” You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

Reference

1. Sammallahti S et al. Excessive crying, behavior problems, and amygdala volume: A study from infancy to adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023 Jun;62(6):675-83. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2023.01.014.

Integrating mental health and primary care: From dipping a toe to taking a plunge

In case anybody hasn’t noticed, the good ole days are long gone in which pediatric patients with mental health challenges could be simply referred out to be promptly assessed and treated by specialists. Due to a shortage of psychiatrists coupled with large increases in the number of youth presenting with emotional-behavioral difficulties, primary care clinicians are now called upon to fill in much of this gap, with professional organizations like the AAP articulating that .1

To meet this need, new models of integrated or collaborative care between primary care and mental health clinicians have been attempted and tested. While these initiatives have certainly been a welcome advance to many pediatricians, the large numbers of different models and initiatives out there have made for a rather confusing landscape that many busy primary care clinicians have found difficult to navigate.

In an attempt to offer some guidance on the subject, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recently published a clinical update on pediatric collaborative care.2 The report is rich with resources and ideas. One of the main points of the document is that there are different levels of integration that exist. Kind of like the situation with recycling and household waste reduction, it is possible to make valuable improvements at any level of participation, although evidence suggests that more extensive efforts offer the most benefits. At one end of the spectrum, psychiatrists and primary care clinicians maintain separate practices and medical records and occasionally discuss mutual patients. Middle levels may include “colocation” with mental health and primary care professionals sharing a building and/or being part of the same overall system but continuing to work mainly independently. At the highest levels of integration, there is a coordinated and collaborative team that supports an intentional system of care with consistent communication about individual patients and general workflows. These approaches vary in the amount that the following four core areas of integrated care are incorporated.

- Direct service. Many integrated care initiatives heavily rely on the services of an on-site mental health care manager or behavioral health consultant who can provide a number of important functions such as overseeing of the integrated care program, conducting brief therapy with youth and parents, overseeing mental health screenings at the clinic, and providing general mental health promotion guidance.

- Care coordination. Helping patients and families find needed mental health, social services, and educational resources is a key component of integrated care. This task can fall to the practice’s behavioral health consultant, if there is one, but more general care coordinators can also be trained for this important role. The University of Washington’s Center for Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions has some published guidelines in this area.3

- Consultation. More advanced integrated care models often have established relationships to specific child psychiatric clinicians who are able to meet with the primary care team to discuss cases and general approaches to various problems. Alternatively, a number of states have implemented what are called Child Psychiatry Access Programs that give primary care clinicians a phone number to an organization (often affiliated with an academic medical center) that can provide quick and even immediate access to a child psychiatry provider for specific questions. Recent federal grants have led to many if not most states now having one of these programs in place, and a website listing these programs and their contact information is available.4

- Education. As mental health training was traditionally not part of a typical pediatrics residency, there have been a number of strategies introduced to help primary care clinicians increase their proficiency and comfort level when it comes to assessing and treating emotional-behavioral problems. These include specific conferences, online programs, and case-based training through mechanisms like the ECHO program.5,6 The AAP itself has released a number of toolkits and training materials related to mental health care that are available.7

The report also outlines some obstacles that continue to get in the way of more extensive integrative care efforts. Chief among them are financial concerns, including how to pay for what often are traditionally nonbillable efforts, particularly those that involve the communication of two expensive health care professionals. Some improvements have been made, however, such as the creation of some relatively new codes (such as 99451 and 99452) that can be submitted by both a primary care and mental health professional when there is a consultation that occurs that does not involve an actual face-to-face encounter.

One area that, in my view, has not received the level of attention it deserves when it comes to integrated care is the degree to which these programs have the potential not only to improve the care of children and adolescents already struggling with mental health challenges but also to serve as a powerful prevention tool to lower the risk of being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder in the future and generally to improve levels of well-being. Thus far, however, research on various integrated programs has shown promising results that indicate that overall care for patients with mental health challenges improves.8 Further, when it comes to costs, there is some evidence to suggest that some of the biggest financial gains associated with integrated care has to do with reduced nonpsychiatric medical expenses of patients.9 This, then, suggests that practices that participate in capitated or accountable care organization structures could particularly benefit both clinically and financially from these collaborations.

If your practice has been challenged with the level of mental health care you are now expected to provide and has been contemplating even some small moves toward integrated care, now may the time to put those thoughts into action.

References

1. Foy JM et al. American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement. Mental health competencies for pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20192757.

2. AACAP Committee on Collaborative and Integrated Care and AACAP Committee on Quality Issues. Clinical update: Collaborative mental health care for children and adolescents in pediatric primary care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62(2):91-119.

3. Behavioral health care managers. AIMS Center, University of Washington. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://aims.uw.edu/online-bhcm-modules.

4. National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://www.nncpap.org/.

5. Project Echo Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://hsc.unm.edu/echo.

6. Project TEACH. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://projectteachny.org.

7. Earls MF et al. Addressing mental health concerns in pediatrics: A practical resource toolkit for clinicians, 2nd edition. Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021.

8. Asarnow JR et al. Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: A meta analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):929-37.

9. Unutzer J et al. Long-term costs effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008.14(2):95-100.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His latest book is “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.” You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

In case anybody hasn’t noticed, the good ole days are long gone in which pediatric patients with mental health challenges could be simply referred out to be promptly assessed and treated by specialists. Due to a shortage of psychiatrists coupled with large increases in the number of youth presenting with emotional-behavioral difficulties, primary care clinicians are now called upon to fill in much of this gap, with professional organizations like the AAP articulating that .1

To meet this need, new models of integrated or collaborative care between primary care and mental health clinicians have been attempted and tested. While these initiatives have certainly been a welcome advance to many pediatricians, the large numbers of different models and initiatives out there have made for a rather confusing landscape that many busy primary care clinicians have found difficult to navigate.

In an attempt to offer some guidance on the subject, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recently published a clinical update on pediatric collaborative care.2 The report is rich with resources and ideas. One of the main points of the document is that there are different levels of integration that exist. Kind of like the situation with recycling and household waste reduction, it is possible to make valuable improvements at any level of participation, although evidence suggests that more extensive efforts offer the most benefits. At one end of the spectrum, psychiatrists and primary care clinicians maintain separate practices and medical records and occasionally discuss mutual patients. Middle levels may include “colocation” with mental health and primary care professionals sharing a building and/or being part of the same overall system but continuing to work mainly independently. At the highest levels of integration, there is a coordinated and collaborative team that supports an intentional system of care with consistent communication about individual patients and general workflows. These approaches vary in the amount that the following four core areas of integrated care are incorporated.

- Direct service. Many integrated care initiatives heavily rely on the services of an on-site mental health care manager or behavioral health consultant who can provide a number of important functions such as overseeing of the integrated care program, conducting brief therapy with youth and parents, overseeing mental health screenings at the clinic, and providing general mental health promotion guidance.

- Care coordination. Helping patients and families find needed mental health, social services, and educational resources is a key component of integrated care. This task can fall to the practice’s behavioral health consultant, if there is one, but more general care coordinators can also be trained for this important role. The University of Washington’s Center for Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions has some published guidelines in this area.3

- Consultation. More advanced integrated care models often have established relationships to specific child psychiatric clinicians who are able to meet with the primary care team to discuss cases and general approaches to various problems. Alternatively, a number of states have implemented what are called Child Psychiatry Access Programs that give primary care clinicians a phone number to an organization (often affiliated with an academic medical center) that can provide quick and even immediate access to a child psychiatry provider for specific questions. Recent federal grants have led to many if not most states now having one of these programs in place, and a website listing these programs and their contact information is available.4

- Education. As mental health training was traditionally not part of a typical pediatrics residency, there have been a number of strategies introduced to help primary care clinicians increase their proficiency and comfort level when it comes to assessing and treating emotional-behavioral problems. These include specific conferences, online programs, and case-based training through mechanisms like the ECHO program.5,6 The AAP itself has released a number of toolkits and training materials related to mental health care that are available.7

The report also outlines some obstacles that continue to get in the way of more extensive integrative care efforts. Chief among them are financial concerns, including how to pay for what often are traditionally nonbillable efforts, particularly those that involve the communication of two expensive health care professionals. Some improvements have been made, however, such as the creation of some relatively new codes (such as 99451 and 99452) that can be submitted by both a primary care and mental health professional when there is a consultation that occurs that does not involve an actual face-to-face encounter.

One area that, in my view, has not received the level of attention it deserves when it comes to integrated care is the degree to which these programs have the potential not only to improve the care of children and adolescents already struggling with mental health challenges but also to serve as a powerful prevention tool to lower the risk of being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder in the future and generally to improve levels of well-being. Thus far, however, research on various integrated programs has shown promising results that indicate that overall care for patients with mental health challenges improves.8 Further, when it comes to costs, there is some evidence to suggest that some of the biggest financial gains associated with integrated care has to do with reduced nonpsychiatric medical expenses of patients.9 This, then, suggests that practices that participate in capitated or accountable care organization structures could particularly benefit both clinically and financially from these collaborations.

If your practice has been challenged with the level of mental health care you are now expected to provide and has been contemplating even some small moves toward integrated care, now may the time to put those thoughts into action.

References

1. Foy JM et al. American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement. Mental health competencies for pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20192757.

2. AACAP Committee on Collaborative and Integrated Care and AACAP Committee on Quality Issues. Clinical update: Collaborative mental health care for children and adolescents in pediatric primary care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62(2):91-119.

3. Behavioral health care managers. AIMS Center, University of Washington. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://aims.uw.edu/online-bhcm-modules.

4. National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://www.nncpap.org/.

5. Project Echo Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://hsc.unm.edu/echo.

6. Project TEACH. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://projectteachny.org.

7. Earls MF et al. Addressing mental health concerns in pediatrics: A practical resource toolkit for clinicians, 2nd edition. Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021.

8. Asarnow JR et al. Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: A meta analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):929-37.

9. Unutzer J et al. Long-term costs effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008.14(2):95-100.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His latest book is “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.” You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

In case anybody hasn’t noticed, the good ole days are long gone in which pediatric patients with mental health challenges could be simply referred out to be promptly assessed and treated by specialists. Due to a shortage of psychiatrists coupled with large increases in the number of youth presenting with emotional-behavioral difficulties, primary care clinicians are now called upon to fill in much of this gap, with professional organizations like the AAP articulating that .1

To meet this need, new models of integrated or collaborative care between primary care and mental health clinicians have been attempted and tested. While these initiatives have certainly been a welcome advance to many pediatricians, the large numbers of different models and initiatives out there have made for a rather confusing landscape that many busy primary care clinicians have found difficult to navigate.

In an attempt to offer some guidance on the subject, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recently published a clinical update on pediatric collaborative care.2 The report is rich with resources and ideas. One of the main points of the document is that there are different levels of integration that exist. Kind of like the situation with recycling and household waste reduction, it is possible to make valuable improvements at any level of participation, although evidence suggests that more extensive efforts offer the most benefits. At one end of the spectrum, psychiatrists and primary care clinicians maintain separate practices and medical records and occasionally discuss mutual patients. Middle levels may include “colocation” with mental health and primary care professionals sharing a building and/or being part of the same overall system but continuing to work mainly independently. At the highest levels of integration, there is a coordinated and collaborative team that supports an intentional system of care with consistent communication about individual patients and general workflows. These approaches vary in the amount that the following four core areas of integrated care are incorporated.

- Direct service. Many integrated care initiatives heavily rely on the services of an on-site mental health care manager or behavioral health consultant who can provide a number of important functions such as overseeing of the integrated care program, conducting brief therapy with youth and parents, overseeing mental health screenings at the clinic, and providing general mental health promotion guidance.

- Care coordination. Helping patients and families find needed mental health, social services, and educational resources is a key component of integrated care. This task can fall to the practice’s behavioral health consultant, if there is one, but more general care coordinators can also be trained for this important role. The University of Washington’s Center for Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions has some published guidelines in this area.3

- Consultation. More advanced integrated care models often have established relationships to specific child psychiatric clinicians who are able to meet with the primary care team to discuss cases and general approaches to various problems. Alternatively, a number of states have implemented what are called Child Psychiatry Access Programs that give primary care clinicians a phone number to an organization (often affiliated with an academic medical center) that can provide quick and even immediate access to a child psychiatry provider for specific questions. Recent federal grants have led to many if not most states now having one of these programs in place, and a website listing these programs and their contact information is available.4

- Education. As mental health training was traditionally not part of a typical pediatrics residency, there have been a number of strategies introduced to help primary care clinicians increase their proficiency and comfort level when it comes to assessing and treating emotional-behavioral problems. These include specific conferences, online programs, and case-based training through mechanisms like the ECHO program.5,6 The AAP itself has released a number of toolkits and training materials related to mental health care that are available.7

The report also outlines some obstacles that continue to get in the way of more extensive integrative care efforts. Chief among them are financial concerns, including how to pay for what often are traditionally nonbillable efforts, particularly those that involve the communication of two expensive health care professionals. Some improvements have been made, however, such as the creation of some relatively new codes (such as 99451 and 99452) that can be submitted by both a primary care and mental health professional when there is a consultation that occurs that does not involve an actual face-to-face encounter.

One area that, in my view, has not received the level of attention it deserves when it comes to integrated care is the degree to which these programs have the potential not only to improve the care of children and adolescents already struggling with mental health challenges but also to serve as a powerful prevention tool to lower the risk of being diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder in the future and generally to improve levels of well-being. Thus far, however, research on various integrated programs has shown promising results that indicate that overall care for patients with mental health challenges improves.8 Further, when it comes to costs, there is some evidence to suggest that some of the biggest financial gains associated with integrated care has to do with reduced nonpsychiatric medical expenses of patients.9 This, then, suggests that practices that participate in capitated or accountable care organization structures could particularly benefit both clinically and financially from these collaborations.

If your practice has been challenged with the level of mental health care you are now expected to provide and has been contemplating even some small moves toward integrated care, now may the time to put those thoughts into action.

References

1. Foy JM et al. American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement. Mental health competencies for pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20192757.

2. AACAP Committee on Collaborative and Integrated Care and AACAP Committee on Quality Issues. Clinical update: Collaborative mental health care for children and adolescents in pediatric primary care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62(2):91-119.

3. Behavioral health care managers. AIMS Center, University of Washington. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://aims.uw.edu/online-bhcm-modules.

4. National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. Available at https://www.nncpap.org/.

5. Project Echo Programs. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://hsc.unm.edu/echo.

6. Project TEACH. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://projectteachny.org.

7. Earls MF et al. Addressing mental health concerns in pediatrics: A practical resource toolkit for clinicians, 2nd edition. Itasca, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021.

8. Asarnow JR et al. Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavioral health: A meta analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):929-37.

9. Unutzer J et al. Long-term costs effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008.14(2):95-100.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His latest book is “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows about the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.” You can follow him on Twitter and Facebook @PediPsych.

AAP vs. AED on obesity treatment: Is there a middle ground?

While there is little controversy that both obesity and eating disorders represent important public health concerns, each deserving of clinical attention, how best to address one without worsening the other has been the crux of the discussion.

Sparking the dispute was a recent publication from the American Academy of Pediatrics that outlines the scope of the obesity problem and makes specific recommendations for assessment and treatment.1 The ambitious 100-page document, with 801 citations, puts new emphasis on the medical and psychological costs associated with obesity and advocates that pediatric primary care clinicians be more assertive in its treatment. While the guidelines certainly don’t urge the use of medications or surgery options as first-line treatment, the new recommendations do put them on the table as options.

In response, the Academy of Eating Disorders issued a public statement outlining several concerns regarding these guidelines that centered around a lack of a detailed plan to screen and address eating disorders; concerns that pediatricians don’t have the level of training and “skills” to conduct these conversations with patients and families with enough sensitivity; and worries about the premature use of antiobesity medications and surgeries in this population.2

It is fair to say that the critique was sharply worded, invoking physicians’ Hippocratic oath, criticizing their training, and suggesting that the guidelines could be biased by pharmaceutical industry influence (of note, the authors of the guidelines reported no ties to any pharmaceutical company). The AED urged that the guidelines be “revised” after consultation with other groups, including them.

Not unexpectedly, this response, especially coming from a group whose leadership and members are primarily nonphysicians, triggered its own sharp rebukes, including a recent commentary that counter-accused some of the eating disorder clinicians of being more concerned with their pet diets than actual health improvements.3

After everyone takes some deep breaths, it’s worth looking to see if there is some middle ground to explore here. The AAP document, to my reading, shows some important acknowledgments of the stigma associated with being overweight, even coming from pediatricians themselves. One passage reads, “Pediatricians and other PHCPs [primary health care providers] have been – and remain – a source of weight bias. They first need to uncover and address their own attitudes regarding children with obesity. Understanding weight stigma and bias, and learning how to reduce it in the clinical setting, sets the stage for productive discussions and improved relationships between families and pediatricians or other PHCPs.”

The guidelines also include some suggestions for how to talk to youth and families about obesity in less stigmatizing ways and offer a fairly lengthy summary of motivational interviewing techniques as they might apply to obesity discussions and lifestyle change. There is also a section on the interface between obesity and eating disorders with suggestions for further reading on their assessment and management.4

Indeed, research has looked specifically at how to minimize the triggering of eating disorders when addressing weight problems, a concern that has been raised by pediatricians themselves as documented in a qualitative study that also invoked the “do no harm” principle.5 One study asked more than 2,000 teens about how various conversations about weight affected their behavior.6 A main finding from that study was that conversations that focused on healthy eating rather than weight per se were less likely to be associated with unhealthy weight control behaviors. This message was emphasized in a publication that came from the AAP itself; it addresses the interaction between eating disorders and obesity.7 Strangely, however, the suggestion to try to minimize the focus on weight in discussions with patients isn’t well emphasized in the publication.

Overall, though, the AAP guidelines offer a well-informed and balanced approach to helping overweight youth. Pediatricians and other pediatric primary care clinicians are frequently called upon to engage in extremely sensitive and difficult discussions with patients and families on a wide variety of topics and most do so quite skillfully, especially when given the proper time and tools. While it is an area in which many of us, including mental health professionals, could do better, it’s no surprise that the AED’s disparaging of pediatricians’ communication competence came off as insulting. Similarly, productive dialogue would be likely enhanced if both sides avoided unfounded speculation about bias and motive and worked from a good faith perspective that all of us are engaged in this important discussion because of a desire to improve the lives of kids.

From my reading, it is quite a stretch to conclude that this document is urging a hasty and financially driven descent into GLP-1 analogues and bariatric surgery. That said, this wouldn’t be the first time a professional organization issues detailed, thoughtful, and nuanced care guidelines only to have them “condensed” within the practical confines of a busy office practice. Leaders would do well to remember that there remains much work to do to empower clinicians to be able to follow these guidelines as intended.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His latest book is “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows About the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.”

References

1. Hampl SE et al. Pediatrics. 2023;151(2):e2022060640.

2. Academy of Eating Disorders. Jan. 26, 2023. Accessed February 2, 2023. Available at The Academy for Eating Disorders Releases a Statement on the Recent American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guideline for Weight-Related Care: First, Do No Harm (newswise.com).

3. Freedhoff Y. MDedge Pediatrics 2023. Available at https://www.mdedge.com/pediatrics/article/260894/obesity/weight-bias-affects-views-kids-obesity-recommendations?channel=52.

4. Hornberger LL, Lane MA et al. Pediatrics. 2021;147(1):e202004027989.

5. Loth KA, Lebow J et al. Global Pediatric Health. 2021;8:1-9.

6. Berge JM et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167(8):746-53.

7. Golden NH et al. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161649.

While there is little controversy that both obesity and eating disorders represent important public health concerns, each deserving of clinical attention, how best to address one without worsening the other has been the crux of the discussion.

Sparking the dispute was a recent publication from the American Academy of Pediatrics that outlines the scope of the obesity problem and makes specific recommendations for assessment and treatment.1 The ambitious 100-page document, with 801 citations, puts new emphasis on the medical and psychological costs associated with obesity and advocates that pediatric primary care clinicians be more assertive in its treatment. While the guidelines certainly don’t urge the use of medications or surgery options as first-line treatment, the new recommendations do put them on the table as options.

In response, the Academy of Eating Disorders issued a public statement outlining several concerns regarding these guidelines that centered around a lack of a detailed plan to screen and address eating disorders; concerns that pediatricians don’t have the level of training and “skills” to conduct these conversations with patients and families with enough sensitivity; and worries about the premature use of antiobesity medications and surgeries in this population.2

It is fair to say that the critique was sharply worded, invoking physicians’ Hippocratic oath, criticizing their training, and suggesting that the guidelines could be biased by pharmaceutical industry influence (of note, the authors of the guidelines reported no ties to any pharmaceutical company). The AED urged that the guidelines be “revised” after consultation with other groups, including them.

Not unexpectedly, this response, especially coming from a group whose leadership and members are primarily nonphysicians, triggered its own sharp rebukes, including a recent commentary that counter-accused some of the eating disorder clinicians of being more concerned with their pet diets than actual health improvements.3

After everyone takes some deep breaths, it’s worth looking to see if there is some middle ground to explore here. The AAP document, to my reading, shows some important acknowledgments of the stigma associated with being overweight, even coming from pediatricians themselves. One passage reads, “Pediatricians and other PHCPs [primary health care providers] have been – and remain – a source of weight bias. They first need to uncover and address their own attitudes regarding children with obesity. Understanding weight stigma and bias, and learning how to reduce it in the clinical setting, sets the stage for productive discussions and improved relationships between families and pediatricians or other PHCPs.”

The guidelines also include some suggestions for how to talk to youth and families about obesity in less stigmatizing ways and offer a fairly lengthy summary of motivational interviewing techniques as they might apply to obesity discussions and lifestyle change. There is also a section on the interface between obesity and eating disorders with suggestions for further reading on their assessment and management.4

Indeed, research has looked specifically at how to minimize the triggering of eating disorders when addressing weight problems, a concern that has been raised by pediatricians themselves as documented in a qualitative study that also invoked the “do no harm” principle.5 One study asked more than 2,000 teens about how various conversations about weight affected their behavior.6 A main finding from that study was that conversations that focused on healthy eating rather than weight per se were less likely to be associated with unhealthy weight control behaviors. This message was emphasized in a publication that came from the AAP itself; it addresses the interaction between eating disorders and obesity.7 Strangely, however, the suggestion to try to minimize the focus on weight in discussions with patients isn’t well emphasized in the publication.

Overall, though, the AAP guidelines offer a well-informed and balanced approach to helping overweight youth. Pediatricians and other pediatric primary care clinicians are frequently called upon to engage in extremely sensitive and difficult discussions with patients and families on a wide variety of topics and most do so quite skillfully, especially when given the proper time and tools. While it is an area in which many of us, including mental health professionals, could do better, it’s no surprise that the AED’s disparaging of pediatricians’ communication competence came off as insulting. Similarly, productive dialogue would be likely enhanced if both sides avoided unfounded speculation about bias and motive and worked from a good faith perspective that all of us are engaged in this important discussion because of a desire to improve the lives of kids.

From my reading, it is quite a stretch to conclude that this document is urging a hasty and financially driven descent into GLP-1 analogues and bariatric surgery. That said, this wouldn’t be the first time a professional organization issues detailed, thoughtful, and nuanced care guidelines only to have them “condensed” within the practical confines of a busy office practice. Leaders would do well to remember that there remains much work to do to empower clinicians to be able to follow these guidelines as intended.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist with Lane County Behavioral Health in Eugene, Ore., and Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. His latest book is “Parenting Made Complicated: What Science Really Knows About the Greatest Debates of Early Childhood.”

References

1. Hampl SE et al. Pediatrics. 2023;151(2):e2022060640.

2. Academy of Eating Disorders. Jan. 26, 2023. Accessed February 2, 2023. Available at The Academy for Eating Disorders Releases a Statement on the Recent American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guideline for Weight-Related Care: First, Do No Harm (newswise.com).

3. Freedhoff Y. MDedge Pediatrics 2023. Available at https://www.mdedge.com/pediatrics/article/260894/obesity/weight-bias-affects-views-kids-obesity-recommendations?channel=52.

4. Hornberger LL, Lane MA et al. Pediatrics. 2021;147(1):e202004027989.

5. Loth KA, Lebow J et al. Global Pediatric Health. 2021;8:1-9.

6. Berge JM et al. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167(8):746-53.

7. Golden NH et al. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161649.

While there is little controversy that both obesity and eating disorders represent important public health concerns, each deserving of clinical attention, how best to address one without worsening the other has been the crux of the discussion.

Sparking the dispute was a recent publication from the American Academy of Pediatrics that outlines the scope of the obesity problem and makes specific recommendations for assessment and treatment.1 The ambitious 100-page document, with 801 citations, puts new emphasis on the medical and psychological costs associated with obesity and advocates that pediatric primary care clinicians be more assertive in its treatment. While the guidelines certainly don’t urge the use of medications or surgery options as first-line treatment, the new recommendations do put them on the table as options.

In response, the Academy of Eating Disorders issued a public statement outlining several concerns regarding these guidelines that centered around a lack of a detailed plan to screen and address eating disorders; concerns that pediatricians don’t have the level of training and “skills” to conduct these conversations with patients and families with enough sensitivity; and worries about the premature use of antiobesity medications and surgeries in this population.2

It is fair to say that the critique was sharply worded, invoking physicians’ Hippocratic oath, criticizing their training, and suggesting that the guidelines could be biased by pharmaceutical industry influence (of note, the authors of the guidelines reported no ties to any pharmaceutical company). The AED urged that the guidelines be “revised” after consultation with other groups, including them.

Not unexpectedly, this response, especially coming from a group whose leadership and members are primarily nonphysicians, triggered its own sharp rebukes, including a recent commentary that counter-accused some of the eating disorder clinicians of being more concerned with their pet diets than actual health improvements.3

After everyone takes some deep breaths, it’s worth looking to see if there is some middle ground to explore here. The AAP document, to my reading, shows some important acknowledgments of the stigma associated with being overweight, even coming from pediatricians themselves. One passage reads, “Pediatricians and other PHCPs [primary health care providers] have been – and remain – a source of weight bias. They first need to uncover and address their own attitudes regarding children with obesity. Understanding weight stigma and bias, and learning how to reduce it in the clinical setting, sets the stage for productive discussions and improved relationships between families and pediatricians or other PHCPs.”

The guidelines also include some suggestions for how to talk to youth and families about obesity in less stigmatizing ways and offer a fairly lengthy summary of motivational interviewing techniques as they might apply to obesity discussions and lifestyle change. There is also a section on the interface between obesity and eating disorders with suggestions for further reading on their assessment and management.4