User login

A Facility-Wide Plan to Increase Access to Medication for Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care and General Mental Health Settings

In the United States, opioid use disorder (OUD) is a major public health challenge. In 2018 drug overdose deaths were 4 times higher than they were in 1999.1 This increase highlights a critical need to expand treatment access. Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, improves outcomes for patients retained in care.2 Compared with the general population, veterans, particularly those with co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, are more likely to receive higher dosages of opioid medications and experience opioid-related adverse outcomes (eg, overdose, OUD).3,4 As a risk reduction strategy, patients receiving potentially dangerous full-dose agonist opioid medication who are unable to taper to safer dosages may be eligible to transition to buprenorphine.5

Buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed in office-based settings or in addiction, primary care, mental health, and pain clinics. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B) expands access to patients who are not reached by addiction treatment programs.6,7 This is particularly true in rural settings, where addiction care services are typically scarce.8 OBOT-B prevents relapse and maintains opioid-free days and may increase patient engagement by reducing stigma and providing treatment within an existing clinical care team.9 For many patients, OBOT-B results in good retention with just medical monitoring and minimal or no ancillary addiction counseling.10,11

Successful implementation of OBOT-B has occurred through a variety of care models in selected community health care settings.8,12,13 Historically in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), MOUD has been prescribed in substance use disorder clinics by mental health practitioners. Currently, more than 44% of veterans with OUD are on MOUD.14

The VHA has invested significant resources to improve access to MOUD. In 2018, the Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative launched, with the aim to improve access within primary care, mental health, and pain clinics.15 SCOUTT emphasizes stepped-care treatment, with patients engaging in the step of care most appropriate to their needs. Step 0 is self-directed care/self-management, including mutual support groups; step-1 environments include office-based primary care, mental health, and pain clinics; and step-2 environments are specialty care settings. Through a series of remote webinars, an in-person national 2-day conference, and external facilitation, SCOUTT engaged 18 teams representing each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) across the country to assist in implementing MOUD within 2 step-1 clinics. These teams have developed several models of providing step-1 care, including an interdisciplinary team-based primary care delivery model as well as a pharmacist care manager model.16, 17

US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Health Care System (VACHS), which delivers care to approximately 58,000 veterans, was chosen to be a phase 1 SCOUTT site. Though all patients in VACHS have access to specialty care step-2 clinics, including methadone and buprenorphine programs, there remained many patients not yet on MOUD who could benefit from it. Baseline data (fiscal year [FY] 2018 4th quarter), obtained through electronic health record (EHR) database dashboards indicated that 710 (56%) patients with an OUD diagnosis were not receiving MOUD. International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision codes are the foundation for VA population management dashboards, and based their data on codes for opioid abuse and opioid dependence. These tools are limited by the accuracy of coding in EHRs. Additionally, 366 patients receiving long-term opioid prescriptions were identified as moderate, high, or very high risk for overdose or death based on an algorithm that considered prescribed medications, sociodemographics, and comorbid conditions, as characterized in the VA EHR (Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation [STORM] report).18

This article describes the VACHSquality-improvement effort to extend OBOT-B into step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics. Our objectives are to (1) outline the process for initiating SCOUTT within VACHS; (2) examine barriers to implementation and the SCOUTT team response; (3) review VACHS patient and prescriber data at baseline and 1 year after implementation; and (4) explore future implementation strategies.

SCOUTT Team

A VACHS interdisciplinary team was formed and attended the national SCOUTT kickoff conference in 2018.15 Similar to other SCOUTT teams, the team consisted of VISN leadership (in primary care, mental health, and addiction care), pharmacists, and a team of health care practitioners (HCPs) from step-2 clinics (including 2 addiction psychiatrists, and an advanced practice registered nurse, a registered nurse specializing in addiction care), and a team of HCPs from prospective step-1 clinics (including a clinical psychologist and 2 primary care physicians). An external facilitator was provided from outside the VISN who met remotely with the team to assist in facilitation. Our team met monthly, with the goal to identify local barriers and facilitators to OBOT-B and implement interventions to enhance prescribing in step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics.

Implementation Steps

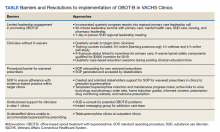

The team identified multiple barriers to dissemination of OBOT-B in target clinics (Table). The 3 main barriers were limited leadership engagement in promoting OBOT-B in target clinics, inadequate number of HCPs with active X-waivered prescribing status in the targeted clinics, and the need for standardized processes and tools to facilitate prescribing and follow-up.

To address leadership engagement, the SCOUTT team held quarterly presentations of SCOUTT goals and progress on target clinic leadership calls (usually 15 minutes) and arranged a 90-minute multidisciplinary leadership summit with key leadership representation from primary care, general mental health, specialty addiction care, nursing, and pharmacy. To enhance X-waivered prescribers in target clinics, the SCOUTT team sent quarterly emails with brief education points on MOUD and links to waiver trainings. At the time of implementation, in order to prescribe buprenorphine and meet qualifications to treat OUD, prescribers were required to complete specialized training as necessitated by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000. X-waivered status can now be obtained without requiring training

The SCOUTT team advocated for X-waivered status to be incentivized by performance pay for primary care practitioners and held quarterly case-based education sessions during preexisting allotted time. The onboarding process for new waivered prescribers to navigate from waiver training to active prescribing within the EHR was standardized via development of a standard operating procedure (SOP).

The SCOUTT team also assisted in the development of standardized processes and tools for prescribing in target clinics, including implementation of a standard operating procedure regarding prescribing (both initiation of buprenorphine, and maintenance) in target clinics. This procedure specifies that target clinic HCPs prescribe for patients requiring less intensive management, and who are appropriate for office-based treatment based on specific criteria (eAppendix

Templated progress notes were created for buprenorphine initiation and buprenorphine maintenance with links to recommended laboratory tests and urine toxicology test ordering, home induction guides, prescription drug monitoring database, naloxone prescribing, and pharmacy order sets. Communication with specialty HCPs was facilitated by development of e-consultation within the EHR and instant messaging options within the local intranet. In the SCOUTT team model, the prescriber independently completed assessment/follow-up without nursing or clinical pharmacy support.

Analysis

We examined changes in MOUD receipt and prescriber characteristics at baseline (FY 2018 4th quarter) and 1 year after implementation (FY 2019 4th quarter). Patient data were extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which contains data from all VHA EHRs. The VA STORM, is a CDW tool that automatically flags patients prescribed opioids who are at risk for overdose and suicide. Prescriber data were obtained from the Buprenorphine/X-Waivered Provider Report, a VA Academic Detailing Service database that provides details on HCP type, X-waivered status, and prescribing by location. χ2 analyses were conducted on before and after measures when total values were available.

Results

There was a 4% increase in patients with an OUD diagnosis receiving MOUD, from 552 (44%) to 582 (48%) (P = .04), over this time. The number of waivered prescribers increased from 67 to 131, the number of prescribers of buprenorphine in a 6-month span increased from 35 to 52, and the percentage of HCPs capable of prescribing within the EHR increased from 75% to 89% (P =.01).

Initially, addiction HCPs prescribed to about 68% of patients on buprenorphine, with target clinic HCPs prescribing to 24% (with the remaining coming from other specialty HCPs). On follow-up, addiction professionals prescribed to 63%, with target clinic clincians prescribing to 32%.

Interpretation

SCOUTT team interventions succeeded in increasing the number of patients receiving MOUD, a substantial increase in waivered HCPs, an increase in the number of waivered HCPs prescribing MOUD, and an increase in the proportion of patients receiving MOUD in step-1 target clinics. It is important to note that within the quality-improvement framework and goals of our SCOUTT team that the data were not collected as part of a research study but to assess impact of our interventions. Within this framework, it is not possible to directly attribute the increase in eligible patients receiving MOUD solely to SCOUTT team interventions, as other factors may have contributed, including improved awareness of HCPs.

Summary and Future Directions

Since implementation of SCOUTT in August 2018, VACHS has identified several barriers to buprenorphine prescribing in step-1 clinics and implemented strategies to overcome them. Describing our approach will hopefully inform other large health care systems (VA or non-VA) on changes required in order to scale up implementation of OBOT-B. The VACHS SCOUTT team was successful at enhancing a ready workforce in step-1 clinics, though noted a delay in changing prescribing practice and culture.

We recommend utilizing academic detailing to work with clinics and individual HCPs to identify and overcome barriers to prescribing. Also, we recommend implementation of a nursing or clinical pharmacy collaborative care model in target step-1 clinics (rather than the HCP-driven model). A collaborative care model reflects the patient aligned care team (PACT) principle of team-based efficient care, and PACT nurses or clinical pharmacists should be able to provide the minimal quarterly follow-up of clinically stable patients on MOUD within the step-1 clinics. Templated notes for assessment, initiation, and follow-up of patients on MOUD are now available from the SCOUTT national program and should be broadly implemented to facilitate adoption of the collaborative model in target clinics. In order to accomplish a full collaborative model, the VHA would need to enhance appropriate staffing to support this model, broaden access to telehealth, and expand incentives to teams/clinicians who prescribe in these settings.

Acknowledgments/Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, Veterans Health Administration; the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Partnered Evaluation Initiative (PEC) grants #19-001. Supporting organizations had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the epidemic. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

2. Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1760-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2

3. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan [published correction appears in JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2489]. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.234

4. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, et al. Trends and regional variation in opioid overdose mortality among Veterans Health Administration patients, fiscal year 2001 to 2009. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):605-612. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000011

5. US Department of Health and Human Services, Working Group on Patient-Centered Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-term Opioid Analgesics. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of Long-term opioid analgesics. Published October 2019. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf

6. Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113-116. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008

7. LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010

8. Rubin R. Rural veterans less likely to get medication for opioid use disorder. JAMA. 2020;323(4):300. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21856

9. Kahan M, Srivastava A, Ordean A, Cirone S. Buprenorphine: new treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):281-289.

10. Fiellin DA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, et al. Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: results at 2-5 years. Am J Addict. 2008;17(2):116-120. doi:10.1080/10550490701860971

11. Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055255

12. Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Integrating buprenorphine maintenance therapy into federally qualified health centers: real-world substance abuse treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):127-135. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.008

13. Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171-176. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1

14. Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: Historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):139-144. doi:10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327

15. Gordon AJ, Drexler K, Hawkins EJ, et al. Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative: Expanding access to medication treatment for opioid use disorder within Veterans Health Administration facilities. Subst Abus. 2020;41(3):275-282. doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1787299

16. Codell N, Kelley AT, Jones AL, et al. Aims, development, and early results of an interdisciplinary primary care initiative to address patient vulnerabilities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(2):160-169. doi:10.1080/00952990.2020.1832507

17. DeRonne BM, Wong KR, Schultz E, Jones E, Krebs EE. Implementation of a pharmacist care manager model to expand availability of medications for opioid use disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):354-359. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa405

18. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

19. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Published February 2017. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/resources/docs/mental-health/substance-abuse/VA_DoD-CLINICAL-PRACTICE-GUIDELINE-FOR-OPIOID-THERAPY-FOR-CHRONIC-PAIN-508.pdf

In the United States, opioid use disorder (OUD) is a major public health challenge. In 2018 drug overdose deaths were 4 times higher than they were in 1999.1 This increase highlights a critical need to expand treatment access. Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, improves outcomes for patients retained in care.2 Compared with the general population, veterans, particularly those with co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, are more likely to receive higher dosages of opioid medications and experience opioid-related adverse outcomes (eg, overdose, OUD).3,4 As a risk reduction strategy, patients receiving potentially dangerous full-dose agonist opioid medication who are unable to taper to safer dosages may be eligible to transition to buprenorphine.5

Buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed in office-based settings or in addiction, primary care, mental health, and pain clinics. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B) expands access to patients who are not reached by addiction treatment programs.6,7 This is particularly true in rural settings, where addiction care services are typically scarce.8 OBOT-B prevents relapse and maintains opioid-free days and may increase patient engagement by reducing stigma and providing treatment within an existing clinical care team.9 For many patients, OBOT-B results in good retention with just medical monitoring and minimal or no ancillary addiction counseling.10,11

Successful implementation of OBOT-B has occurred through a variety of care models in selected community health care settings.8,12,13 Historically in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), MOUD has been prescribed in substance use disorder clinics by mental health practitioners. Currently, more than 44% of veterans with OUD are on MOUD.14

The VHA has invested significant resources to improve access to MOUD. In 2018, the Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative launched, with the aim to improve access within primary care, mental health, and pain clinics.15 SCOUTT emphasizes stepped-care treatment, with patients engaging in the step of care most appropriate to their needs. Step 0 is self-directed care/self-management, including mutual support groups; step-1 environments include office-based primary care, mental health, and pain clinics; and step-2 environments are specialty care settings. Through a series of remote webinars, an in-person national 2-day conference, and external facilitation, SCOUTT engaged 18 teams representing each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) across the country to assist in implementing MOUD within 2 step-1 clinics. These teams have developed several models of providing step-1 care, including an interdisciplinary team-based primary care delivery model as well as a pharmacist care manager model.16, 17

US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Health Care System (VACHS), which delivers care to approximately 58,000 veterans, was chosen to be a phase 1 SCOUTT site. Though all patients in VACHS have access to specialty care step-2 clinics, including methadone and buprenorphine programs, there remained many patients not yet on MOUD who could benefit from it. Baseline data (fiscal year [FY] 2018 4th quarter), obtained through electronic health record (EHR) database dashboards indicated that 710 (56%) patients with an OUD diagnosis were not receiving MOUD. International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision codes are the foundation for VA population management dashboards, and based their data on codes for opioid abuse and opioid dependence. These tools are limited by the accuracy of coding in EHRs. Additionally, 366 patients receiving long-term opioid prescriptions were identified as moderate, high, or very high risk for overdose or death based on an algorithm that considered prescribed medications, sociodemographics, and comorbid conditions, as characterized in the VA EHR (Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation [STORM] report).18

This article describes the VACHSquality-improvement effort to extend OBOT-B into step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics. Our objectives are to (1) outline the process for initiating SCOUTT within VACHS; (2) examine barriers to implementation and the SCOUTT team response; (3) review VACHS patient and prescriber data at baseline and 1 year after implementation; and (4) explore future implementation strategies.

SCOUTT Team

A VACHS interdisciplinary team was formed and attended the national SCOUTT kickoff conference in 2018.15 Similar to other SCOUTT teams, the team consisted of VISN leadership (in primary care, mental health, and addiction care), pharmacists, and a team of health care practitioners (HCPs) from step-2 clinics (including 2 addiction psychiatrists, and an advanced practice registered nurse, a registered nurse specializing in addiction care), and a team of HCPs from prospective step-1 clinics (including a clinical psychologist and 2 primary care physicians). An external facilitator was provided from outside the VISN who met remotely with the team to assist in facilitation. Our team met monthly, with the goal to identify local barriers and facilitators to OBOT-B and implement interventions to enhance prescribing in step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics.

Implementation Steps

The team identified multiple barriers to dissemination of OBOT-B in target clinics (Table). The 3 main barriers were limited leadership engagement in promoting OBOT-B in target clinics, inadequate number of HCPs with active X-waivered prescribing status in the targeted clinics, and the need for standardized processes and tools to facilitate prescribing and follow-up.

To address leadership engagement, the SCOUTT team held quarterly presentations of SCOUTT goals and progress on target clinic leadership calls (usually 15 minutes) and arranged a 90-minute multidisciplinary leadership summit with key leadership representation from primary care, general mental health, specialty addiction care, nursing, and pharmacy. To enhance X-waivered prescribers in target clinics, the SCOUTT team sent quarterly emails with brief education points on MOUD and links to waiver trainings. At the time of implementation, in order to prescribe buprenorphine and meet qualifications to treat OUD, prescribers were required to complete specialized training as necessitated by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000. X-waivered status can now be obtained without requiring training

The SCOUTT team advocated for X-waivered status to be incentivized by performance pay for primary care practitioners and held quarterly case-based education sessions during preexisting allotted time. The onboarding process for new waivered prescribers to navigate from waiver training to active prescribing within the EHR was standardized via development of a standard operating procedure (SOP).

The SCOUTT team also assisted in the development of standardized processes and tools for prescribing in target clinics, including implementation of a standard operating procedure regarding prescribing (both initiation of buprenorphine, and maintenance) in target clinics. This procedure specifies that target clinic HCPs prescribe for patients requiring less intensive management, and who are appropriate for office-based treatment based on specific criteria (eAppendix

Templated progress notes were created for buprenorphine initiation and buprenorphine maintenance with links to recommended laboratory tests and urine toxicology test ordering, home induction guides, prescription drug monitoring database, naloxone prescribing, and pharmacy order sets. Communication with specialty HCPs was facilitated by development of e-consultation within the EHR and instant messaging options within the local intranet. In the SCOUTT team model, the prescriber independently completed assessment/follow-up without nursing or clinical pharmacy support.

Analysis

We examined changes in MOUD receipt and prescriber characteristics at baseline (FY 2018 4th quarter) and 1 year after implementation (FY 2019 4th quarter). Patient data were extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which contains data from all VHA EHRs. The VA STORM, is a CDW tool that automatically flags patients prescribed opioids who are at risk for overdose and suicide. Prescriber data were obtained from the Buprenorphine/X-Waivered Provider Report, a VA Academic Detailing Service database that provides details on HCP type, X-waivered status, and prescribing by location. χ2 analyses were conducted on before and after measures when total values were available.

Results

There was a 4% increase in patients with an OUD diagnosis receiving MOUD, from 552 (44%) to 582 (48%) (P = .04), over this time. The number of waivered prescribers increased from 67 to 131, the number of prescribers of buprenorphine in a 6-month span increased from 35 to 52, and the percentage of HCPs capable of prescribing within the EHR increased from 75% to 89% (P =.01).

Initially, addiction HCPs prescribed to about 68% of patients on buprenorphine, with target clinic HCPs prescribing to 24% (with the remaining coming from other specialty HCPs). On follow-up, addiction professionals prescribed to 63%, with target clinic clincians prescribing to 32%.

Interpretation

SCOUTT team interventions succeeded in increasing the number of patients receiving MOUD, a substantial increase in waivered HCPs, an increase in the number of waivered HCPs prescribing MOUD, and an increase in the proportion of patients receiving MOUD in step-1 target clinics. It is important to note that within the quality-improvement framework and goals of our SCOUTT team that the data were not collected as part of a research study but to assess impact of our interventions. Within this framework, it is not possible to directly attribute the increase in eligible patients receiving MOUD solely to SCOUTT team interventions, as other factors may have contributed, including improved awareness of HCPs.

Summary and Future Directions

Since implementation of SCOUTT in August 2018, VACHS has identified several barriers to buprenorphine prescribing in step-1 clinics and implemented strategies to overcome them. Describing our approach will hopefully inform other large health care systems (VA or non-VA) on changes required in order to scale up implementation of OBOT-B. The VACHS SCOUTT team was successful at enhancing a ready workforce in step-1 clinics, though noted a delay in changing prescribing practice and culture.

We recommend utilizing academic detailing to work with clinics and individual HCPs to identify and overcome barriers to prescribing. Also, we recommend implementation of a nursing or clinical pharmacy collaborative care model in target step-1 clinics (rather than the HCP-driven model). A collaborative care model reflects the patient aligned care team (PACT) principle of team-based efficient care, and PACT nurses or clinical pharmacists should be able to provide the minimal quarterly follow-up of clinically stable patients on MOUD within the step-1 clinics. Templated notes for assessment, initiation, and follow-up of patients on MOUD are now available from the SCOUTT national program and should be broadly implemented to facilitate adoption of the collaborative model in target clinics. In order to accomplish a full collaborative model, the VHA would need to enhance appropriate staffing to support this model, broaden access to telehealth, and expand incentives to teams/clinicians who prescribe in these settings.

Acknowledgments/Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, Veterans Health Administration; the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Partnered Evaluation Initiative (PEC) grants #19-001. Supporting organizations had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

In the United States, opioid use disorder (OUD) is a major public health challenge. In 2018 drug overdose deaths were 4 times higher than they were in 1999.1 This increase highlights a critical need to expand treatment access. Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, improves outcomes for patients retained in care.2 Compared with the general population, veterans, particularly those with co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, are more likely to receive higher dosages of opioid medications and experience opioid-related adverse outcomes (eg, overdose, OUD).3,4 As a risk reduction strategy, patients receiving potentially dangerous full-dose agonist opioid medication who are unable to taper to safer dosages may be eligible to transition to buprenorphine.5

Buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed in office-based settings or in addiction, primary care, mental health, and pain clinics. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B) expands access to patients who are not reached by addiction treatment programs.6,7 This is particularly true in rural settings, where addiction care services are typically scarce.8 OBOT-B prevents relapse and maintains opioid-free days and may increase patient engagement by reducing stigma and providing treatment within an existing clinical care team.9 For many patients, OBOT-B results in good retention with just medical monitoring and minimal or no ancillary addiction counseling.10,11

Successful implementation of OBOT-B has occurred through a variety of care models in selected community health care settings.8,12,13 Historically in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), MOUD has been prescribed in substance use disorder clinics by mental health practitioners. Currently, more than 44% of veterans with OUD are on MOUD.14

The VHA has invested significant resources to improve access to MOUD. In 2018, the Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative launched, with the aim to improve access within primary care, mental health, and pain clinics.15 SCOUTT emphasizes stepped-care treatment, with patients engaging in the step of care most appropriate to their needs. Step 0 is self-directed care/self-management, including mutual support groups; step-1 environments include office-based primary care, mental health, and pain clinics; and step-2 environments are specialty care settings. Through a series of remote webinars, an in-person national 2-day conference, and external facilitation, SCOUTT engaged 18 teams representing each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) across the country to assist in implementing MOUD within 2 step-1 clinics. These teams have developed several models of providing step-1 care, including an interdisciplinary team-based primary care delivery model as well as a pharmacist care manager model.16, 17

US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Health Care System (VACHS), which delivers care to approximately 58,000 veterans, was chosen to be a phase 1 SCOUTT site. Though all patients in VACHS have access to specialty care step-2 clinics, including methadone and buprenorphine programs, there remained many patients not yet on MOUD who could benefit from it. Baseline data (fiscal year [FY] 2018 4th quarter), obtained through electronic health record (EHR) database dashboards indicated that 710 (56%) patients with an OUD diagnosis were not receiving MOUD. International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision codes are the foundation for VA population management dashboards, and based their data on codes for opioid abuse and opioid dependence. These tools are limited by the accuracy of coding in EHRs. Additionally, 366 patients receiving long-term opioid prescriptions were identified as moderate, high, or very high risk for overdose or death based on an algorithm that considered prescribed medications, sociodemographics, and comorbid conditions, as characterized in the VA EHR (Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation [STORM] report).18

This article describes the VACHSquality-improvement effort to extend OBOT-B into step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics. Our objectives are to (1) outline the process for initiating SCOUTT within VACHS; (2) examine barriers to implementation and the SCOUTT team response; (3) review VACHS patient and prescriber data at baseline and 1 year after implementation; and (4) explore future implementation strategies.

SCOUTT Team

A VACHS interdisciplinary team was formed and attended the national SCOUTT kickoff conference in 2018.15 Similar to other SCOUTT teams, the team consisted of VISN leadership (in primary care, mental health, and addiction care), pharmacists, and a team of health care practitioners (HCPs) from step-2 clinics (including 2 addiction psychiatrists, and an advanced practice registered nurse, a registered nurse specializing in addiction care), and a team of HCPs from prospective step-1 clinics (including a clinical psychologist and 2 primary care physicians). An external facilitator was provided from outside the VISN who met remotely with the team to assist in facilitation. Our team met monthly, with the goal to identify local barriers and facilitators to OBOT-B and implement interventions to enhance prescribing in step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics.

Implementation Steps

The team identified multiple barriers to dissemination of OBOT-B in target clinics (Table). The 3 main barriers were limited leadership engagement in promoting OBOT-B in target clinics, inadequate number of HCPs with active X-waivered prescribing status in the targeted clinics, and the need for standardized processes and tools to facilitate prescribing and follow-up.

To address leadership engagement, the SCOUTT team held quarterly presentations of SCOUTT goals and progress on target clinic leadership calls (usually 15 minutes) and arranged a 90-minute multidisciplinary leadership summit with key leadership representation from primary care, general mental health, specialty addiction care, nursing, and pharmacy. To enhance X-waivered prescribers in target clinics, the SCOUTT team sent quarterly emails with brief education points on MOUD and links to waiver trainings. At the time of implementation, in order to prescribe buprenorphine and meet qualifications to treat OUD, prescribers were required to complete specialized training as necessitated by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000. X-waivered status can now be obtained without requiring training

The SCOUTT team advocated for X-waivered status to be incentivized by performance pay for primary care practitioners and held quarterly case-based education sessions during preexisting allotted time. The onboarding process for new waivered prescribers to navigate from waiver training to active prescribing within the EHR was standardized via development of a standard operating procedure (SOP).

The SCOUTT team also assisted in the development of standardized processes and tools for prescribing in target clinics, including implementation of a standard operating procedure regarding prescribing (both initiation of buprenorphine, and maintenance) in target clinics. This procedure specifies that target clinic HCPs prescribe for patients requiring less intensive management, and who are appropriate for office-based treatment based on specific criteria (eAppendix

Templated progress notes were created for buprenorphine initiation and buprenorphine maintenance with links to recommended laboratory tests and urine toxicology test ordering, home induction guides, prescription drug monitoring database, naloxone prescribing, and pharmacy order sets. Communication with specialty HCPs was facilitated by development of e-consultation within the EHR and instant messaging options within the local intranet. In the SCOUTT team model, the prescriber independently completed assessment/follow-up without nursing or clinical pharmacy support.

Analysis

We examined changes in MOUD receipt and prescriber characteristics at baseline (FY 2018 4th quarter) and 1 year after implementation (FY 2019 4th quarter). Patient data were extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which contains data from all VHA EHRs. The VA STORM, is a CDW tool that automatically flags patients prescribed opioids who are at risk for overdose and suicide. Prescriber data were obtained from the Buprenorphine/X-Waivered Provider Report, a VA Academic Detailing Service database that provides details on HCP type, X-waivered status, and prescribing by location. χ2 analyses were conducted on before and after measures when total values were available.

Results

There was a 4% increase in patients with an OUD diagnosis receiving MOUD, from 552 (44%) to 582 (48%) (P = .04), over this time. The number of waivered prescribers increased from 67 to 131, the number of prescribers of buprenorphine in a 6-month span increased from 35 to 52, and the percentage of HCPs capable of prescribing within the EHR increased from 75% to 89% (P =.01).

Initially, addiction HCPs prescribed to about 68% of patients on buprenorphine, with target clinic HCPs prescribing to 24% (with the remaining coming from other specialty HCPs). On follow-up, addiction professionals prescribed to 63%, with target clinic clincians prescribing to 32%.

Interpretation

SCOUTT team interventions succeeded in increasing the number of patients receiving MOUD, a substantial increase in waivered HCPs, an increase in the number of waivered HCPs prescribing MOUD, and an increase in the proportion of patients receiving MOUD in step-1 target clinics. It is important to note that within the quality-improvement framework and goals of our SCOUTT team that the data were not collected as part of a research study but to assess impact of our interventions. Within this framework, it is not possible to directly attribute the increase in eligible patients receiving MOUD solely to SCOUTT team interventions, as other factors may have contributed, including improved awareness of HCPs.

Summary and Future Directions

Since implementation of SCOUTT in August 2018, VACHS has identified several barriers to buprenorphine prescribing in step-1 clinics and implemented strategies to overcome them. Describing our approach will hopefully inform other large health care systems (VA or non-VA) on changes required in order to scale up implementation of OBOT-B. The VACHS SCOUTT team was successful at enhancing a ready workforce in step-1 clinics, though noted a delay in changing prescribing practice and culture.

We recommend utilizing academic detailing to work with clinics and individual HCPs to identify and overcome barriers to prescribing. Also, we recommend implementation of a nursing or clinical pharmacy collaborative care model in target step-1 clinics (rather than the HCP-driven model). A collaborative care model reflects the patient aligned care team (PACT) principle of team-based efficient care, and PACT nurses or clinical pharmacists should be able to provide the minimal quarterly follow-up of clinically stable patients on MOUD within the step-1 clinics. Templated notes for assessment, initiation, and follow-up of patients on MOUD are now available from the SCOUTT national program and should be broadly implemented to facilitate adoption of the collaborative model in target clinics. In order to accomplish a full collaborative model, the VHA would need to enhance appropriate staffing to support this model, broaden access to telehealth, and expand incentives to teams/clinicians who prescribe in these settings.

Acknowledgments/Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, Veterans Health Administration; the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Partnered Evaluation Initiative (PEC) grants #19-001. Supporting organizations had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the epidemic. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

2. Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1760-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2

3. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan [published correction appears in JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2489]. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.234

4. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, et al. Trends and regional variation in opioid overdose mortality among Veterans Health Administration patients, fiscal year 2001 to 2009. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):605-612. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000011

5. US Department of Health and Human Services, Working Group on Patient-Centered Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-term Opioid Analgesics. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of Long-term opioid analgesics. Published October 2019. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf

6. Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113-116. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008

7. LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010

8. Rubin R. Rural veterans less likely to get medication for opioid use disorder. JAMA. 2020;323(4):300. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21856

9. Kahan M, Srivastava A, Ordean A, Cirone S. Buprenorphine: new treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):281-289.

10. Fiellin DA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, et al. Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: results at 2-5 years. Am J Addict. 2008;17(2):116-120. doi:10.1080/10550490701860971

11. Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055255

12. Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Integrating buprenorphine maintenance therapy into federally qualified health centers: real-world substance abuse treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):127-135. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.008

13. Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171-176. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1

14. Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: Historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):139-144. doi:10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327

15. Gordon AJ, Drexler K, Hawkins EJ, et al. Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative: Expanding access to medication treatment for opioid use disorder within Veterans Health Administration facilities. Subst Abus. 2020;41(3):275-282. doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1787299

16. Codell N, Kelley AT, Jones AL, et al. Aims, development, and early results of an interdisciplinary primary care initiative to address patient vulnerabilities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(2):160-169. doi:10.1080/00952990.2020.1832507

17. DeRonne BM, Wong KR, Schultz E, Jones E, Krebs EE. Implementation of a pharmacist care manager model to expand availability of medications for opioid use disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):354-359. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa405

18. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

19. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Published February 2017. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/resources/docs/mental-health/substance-abuse/VA_DoD-CLINICAL-PRACTICE-GUIDELINE-FOR-OPIOID-THERAPY-FOR-CHRONIC-PAIN-508.pdf

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the epidemic. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

2. Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1760-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2

3. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan [published correction appears in JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2489]. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.234

4. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, et al. Trends and regional variation in opioid overdose mortality among Veterans Health Administration patients, fiscal year 2001 to 2009. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):605-612. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000011

5. US Department of Health and Human Services, Working Group on Patient-Centered Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-term Opioid Analgesics. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of Long-term opioid analgesics. Published October 2019. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf

6. Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113-116. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008

7. LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010

8. Rubin R. Rural veterans less likely to get medication for opioid use disorder. JAMA. 2020;323(4):300. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21856

9. Kahan M, Srivastava A, Ordean A, Cirone S. Buprenorphine: new treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):281-289.

10. Fiellin DA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, et al. Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: results at 2-5 years. Am J Addict. 2008;17(2):116-120. doi:10.1080/10550490701860971

11. Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055255

12. Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Integrating buprenorphine maintenance therapy into federally qualified health centers: real-world substance abuse treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):127-135. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.008

13. Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171-176. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1

14. Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: Historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):139-144. doi:10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327

15. Gordon AJ, Drexler K, Hawkins EJ, et al. Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative: Expanding access to medication treatment for opioid use disorder within Veterans Health Administration facilities. Subst Abus. 2020;41(3):275-282. doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1787299

16. Codell N, Kelley AT, Jones AL, et al. Aims, development, and early results of an interdisciplinary primary care initiative to address patient vulnerabilities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(2):160-169. doi:10.1080/00952990.2020.1832507

17. DeRonne BM, Wong KR, Schultz E, Jones E, Krebs EE. Implementation of a pharmacist care manager model to expand availability of medications for opioid use disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):354-359. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa405

18. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

19. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Published February 2017. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/resources/docs/mental-health/substance-abuse/VA_DoD-CLINICAL-PRACTICE-GUIDELINE-FOR-OPIOID-THERAPY-FOR-CHRONIC-PAIN-508.pdf

Depression rates up threefold since start of COVID-19

A year into the COVID-19 pandemic, the share of the U.S. adult population reporting symptoms of elevated depression had more than tripled from prepandemic levels and worsened significantly since restrictions went into effect, a study of more than 1,000 adults surveyed at the start of the pandemic and 1 year into it has reported.

The study also found that younger adults, people with lower incomes and savings, unmarried people, and those exposed to multiple stress factors were most vulnerable to elevated levels of depression through the first year of the pandemic.

“The pandemic has been an ongoing exposure,” lead author Catherine K. Ettman, a PhD candidate at Brown University, Providence, R.I., said in an interview. “Mental health is sensitive to economic and social conditions. While living conditions have improved for some people over the last 12 months, the pandemic has been disruptive to life and economic well-being for many,” said Ms. Ettman, who is also chief of staff and director of strategic initiatives in the office of the dean at Boston University. Her study was published in Lancet Regional Health – Americas.

Ms. Ettman and coauthors reported that 32.8% (95% confidence interval, 29.1%-36.8%) of surveyed adults had elevated depressive symptoms in 2021, compared with 27.8% (95% CI, 24.9%-30.9%) in the early months of the pandemic in 2020 (P = .0016). That compares with a rate of 8.5% before the pandemic, a figure based on a prepandemic sample of 5,065 patients from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reported previously by Ms. Ettman and associates.

“The COVID-19 pandemic and its economic consequences have displaced social networks, created ongoing stressors, and reduced access to the resources that protect mental health,” Ms. Ettman said.

Four groups most affected

In this latest research, a longitudinal panel study of a nationally representative group of U.S. adults, the researchers surveyed participants in March and April 2020 (n = 1,414) and the same group again in March and April 2021 (n = 1,161). The participants completed the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and were enrolled in the COVID-19 and Life Stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-Being study.

The study found that elevated depressive symptoms were most prevalent in four groups:

- Younger patients, with 43.9% of patients aged 18-39 years self-reporting elevated depressive symptoms, compared with 32.4% of those aged 40-59, and 19.1% of patients aged 60 and older.

- People with lower incomes, with 58.1% of people making $19,999 or less reporting elevated symptoms, compared with 41.3% of those making $20,000-$44,999, 31.4% of people making $45,000-$74,999, and 14.1% of those making $75,000 or more.

- People with less than $5,000 in family savings, with a rate of 51.1%, compared with 24.2% of those with more than that.

- People never married, with a rate of 39.8% versus 37.7% of those living with a partner; 31.5% widowed, divorced, or separated; and 18.3% married.

The study also found correlations between the number of self-reported stressors and elevated depression symptoms: a rate of 51.1% in people with four or more stressors; 25.8% in those with two or three stressors; and 17% in people with one or no stressors.

Among the groups reporting the lowest rates of depressive symptoms in 2021 were people making more than $75,000 a year; those with one or no COVID-19 stressors; and non-Hispanic Asian persons.

“Stressors such as difficulties finding childcare, difficulties paying for housing, and job loss were associated with greater depression 12 months into the COVID-19 pandemic,” Ms. Ettman said. “Efforts to address stressors and improve access to childcare, housing, employment, and fair wages can improve mental health.”

The duration of the pandemic is another explanation for the significant rise in depressive symptoms, senior author Sandro Galea, MD, MPH, DrPH, said in an interview. Dr. Galea added. “Unlike acute traumatic events, the COVID-19 pandemic has been ongoing.”

He said clinicians, public health officials, and policy makers need to be aware of the impact COVID-19 has had on mental health. “We can take steps as a society to treat and prevent depression and create conditions that allow all populations to be healthy,” said Dr. Galea, who is dean and a professor of family medicine at Boston University.

Age of sample cited as limitation

The study builds on existing evidence linking depression trends and the COVID-19 pandemic, David Puder, MD, a medical director at Loma Linda (Calif.) University, said in an interview. However, he noted it had some limitations. “The age range is only 18 and older, so we don’t get to see what is happening with a highly impacted group of students who have not been able to go to school and be with their friends during COVID,” said Dr. Puder, who also hosts the podcast “Psychiatry & Psychotherapy.” “Further, the PHQ-9 is often a screening tool for depression and is not best used for changes in mental health over time.”

At the same time, Dr. Puder said, one of the study’s strengths was that it showed how depressive symptoms increased during the COVID lockdown. “It shows certain groups are at higher risk, including those with less financial resources and those with higher amounts of stress,” Dr. Puder said.

Ms. Ettman, Dr. Galea, and Dr. Puder reported no relevant disclosures.

A year into the COVID-19 pandemic, the share of the U.S. adult population reporting symptoms of elevated depression had more than tripled from prepandemic levels and worsened significantly since restrictions went into effect, a study of more than 1,000 adults surveyed at the start of the pandemic and 1 year into it has reported.

The study also found that younger adults, people with lower incomes and savings, unmarried people, and those exposed to multiple stress factors were most vulnerable to elevated levels of depression through the first year of the pandemic.

“The pandemic has been an ongoing exposure,” lead author Catherine K. Ettman, a PhD candidate at Brown University, Providence, R.I., said in an interview. “Mental health is sensitive to economic and social conditions. While living conditions have improved for some people over the last 12 months, the pandemic has been disruptive to life and economic well-being for many,” said Ms. Ettman, who is also chief of staff and director of strategic initiatives in the office of the dean at Boston University. Her study was published in Lancet Regional Health – Americas.

Ms. Ettman and coauthors reported that 32.8% (95% confidence interval, 29.1%-36.8%) of surveyed adults had elevated depressive symptoms in 2021, compared with 27.8% (95% CI, 24.9%-30.9%) in the early months of the pandemic in 2020 (P = .0016). That compares with a rate of 8.5% before the pandemic, a figure based on a prepandemic sample of 5,065 patients from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reported previously by Ms. Ettman and associates.

“The COVID-19 pandemic and its economic consequences have displaced social networks, created ongoing stressors, and reduced access to the resources that protect mental health,” Ms. Ettman said.

Four groups most affected

In this latest research, a longitudinal panel study of a nationally representative group of U.S. adults, the researchers surveyed participants in March and April 2020 (n = 1,414) and the same group again in March and April 2021 (n = 1,161). The participants completed the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and were enrolled in the COVID-19 and Life Stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-Being study.

The study found that elevated depressive symptoms were most prevalent in four groups:

- Younger patients, with 43.9% of patients aged 18-39 years self-reporting elevated depressive symptoms, compared with 32.4% of those aged 40-59, and 19.1% of patients aged 60 and older.

- People with lower incomes, with 58.1% of people making $19,999 or less reporting elevated symptoms, compared with 41.3% of those making $20,000-$44,999, 31.4% of people making $45,000-$74,999, and 14.1% of those making $75,000 or more.

- People with less than $5,000 in family savings, with a rate of 51.1%, compared with 24.2% of those with more than that.

- People never married, with a rate of 39.8% versus 37.7% of those living with a partner; 31.5% widowed, divorced, or separated; and 18.3% married.

The study also found correlations between the number of self-reported stressors and elevated depression symptoms: a rate of 51.1% in people with four or more stressors; 25.8% in those with two or three stressors; and 17% in people with one or no stressors.

Among the groups reporting the lowest rates of depressive symptoms in 2021 were people making more than $75,000 a year; those with one or no COVID-19 stressors; and non-Hispanic Asian persons.

“Stressors such as difficulties finding childcare, difficulties paying for housing, and job loss were associated with greater depression 12 months into the COVID-19 pandemic,” Ms. Ettman said. “Efforts to address stressors and improve access to childcare, housing, employment, and fair wages can improve mental health.”

The duration of the pandemic is another explanation for the significant rise in depressive symptoms, senior author Sandro Galea, MD, MPH, DrPH, said in an interview. Dr. Galea added. “Unlike acute traumatic events, the COVID-19 pandemic has been ongoing.”

He said clinicians, public health officials, and policy makers need to be aware of the impact COVID-19 has had on mental health. “We can take steps as a society to treat and prevent depression and create conditions that allow all populations to be healthy,” said Dr. Galea, who is dean and a professor of family medicine at Boston University.

Age of sample cited as limitation

The study builds on existing evidence linking depression trends and the COVID-19 pandemic, David Puder, MD, a medical director at Loma Linda (Calif.) University, said in an interview. However, he noted it had some limitations. “The age range is only 18 and older, so we don’t get to see what is happening with a highly impacted group of students who have not been able to go to school and be with their friends during COVID,” said Dr. Puder, who also hosts the podcast “Psychiatry & Psychotherapy.” “Further, the PHQ-9 is often a screening tool for depression and is not best used for changes in mental health over time.”

At the same time, Dr. Puder said, one of the study’s strengths was that it showed how depressive symptoms increased during the COVID lockdown. “It shows certain groups are at higher risk, including those with less financial resources and those with higher amounts of stress,” Dr. Puder said.

Ms. Ettman, Dr. Galea, and Dr. Puder reported no relevant disclosures.

A year into the COVID-19 pandemic, the share of the U.S. adult population reporting symptoms of elevated depression had more than tripled from prepandemic levels and worsened significantly since restrictions went into effect, a study of more than 1,000 adults surveyed at the start of the pandemic and 1 year into it has reported.

The study also found that younger adults, people with lower incomes and savings, unmarried people, and those exposed to multiple stress factors were most vulnerable to elevated levels of depression through the first year of the pandemic.

“The pandemic has been an ongoing exposure,” lead author Catherine K. Ettman, a PhD candidate at Brown University, Providence, R.I., said in an interview. “Mental health is sensitive to economic and social conditions. While living conditions have improved for some people over the last 12 months, the pandemic has been disruptive to life and economic well-being for many,” said Ms. Ettman, who is also chief of staff and director of strategic initiatives in the office of the dean at Boston University. Her study was published in Lancet Regional Health – Americas.

Ms. Ettman and coauthors reported that 32.8% (95% confidence interval, 29.1%-36.8%) of surveyed adults had elevated depressive symptoms in 2021, compared with 27.8% (95% CI, 24.9%-30.9%) in the early months of the pandemic in 2020 (P = .0016). That compares with a rate of 8.5% before the pandemic, a figure based on a prepandemic sample of 5,065 patients from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reported previously by Ms. Ettman and associates.

“The COVID-19 pandemic and its economic consequences have displaced social networks, created ongoing stressors, and reduced access to the resources that protect mental health,” Ms. Ettman said.

Four groups most affected

In this latest research, a longitudinal panel study of a nationally representative group of U.S. adults, the researchers surveyed participants in March and April 2020 (n = 1,414) and the same group again in March and April 2021 (n = 1,161). The participants completed the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9) and were enrolled in the COVID-19 and Life Stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-Being study.

The study found that elevated depressive symptoms were most prevalent in four groups:

- Younger patients, with 43.9% of patients aged 18-39 years self-reporting elevated depressive symptoms, compared with 32.4% of those aged 40-59, and 19.1% of patients aged 60 and older.

- People with lower incomes, with 58.1% of people making $19,999 or less reporting elevated symptoms, compared with 41.3% of those making $20,000-$44,999, 31.4% of people making $45,000-$74,999, and 14.1% of those making $75,000 or more.

- People with less than $5,000 in family savings, with a rate of 51.1%, compared with 24.2% of those with more than that.

- People never married, with a rate of 39.8% versus 37.7% of those living with a partner; 31.5% widowed, divorced, or separated; and 18.3% married.

The study also found correlations between the number of self-reported stressors and elevated depression symptoms: a rate of 51.1% in people with four or more stressors; 25.8% in those with two or three stressors; and 17% in people with one or no stressors.

Among the groups reporting the lowest rates of depressive symptoms in 2021 were people making more than $75,000 a year; those with one or no COVID-19 stressors; and non-Hispanic Asian persons.

“Stressors such as difficulties finding childcare, difficulties paying for housing, and job loss were associated with greater depression 12 months into the COVID-19 pandemic,” Ms. Ettman said. “Efforts to address stressors and improve access to childcare, housing, employment, and fair wages can improve mental health.”

The duration of the pandemic is another explanation for the significant rise in depressive symptoms, senior author Sandro Galea, MD, MPH, DrPH, said in an interview. Dr. Galea added. “Unlike acute traumatic events, the COVID-19 pandemic has been ongoing.”

He said clinicians, public health officials, and policy makers need to be aware of the impact COVID-19 has had on mental health. “We can take steps as a society to treat and prevent depression and create conditions that allow all populations to be healthy,” said Dr. Galea, who is dean and a professor of family medicine at Boston University.

Age of sample cited as limitation

The study builds on existing evidence linking depression trends and the COVID-19 pandemic, David Puder, MD, a medical director at Loma Linda (Calif.) University, said in an interview. However, he noted it had some limitations. “The age range is only 18 and older, so we don’t get to see what is happening with a highly impacted group of students who have not been able to go to school and be with their friends during COVID,” said Dr. Puder, who also hosts the podcast “Psychiatry & Psychotherapy.” “Further, the PHQ-9 is often a screening tool for depression and is not best used for changes in mental health over time.”

At the same time, Dr. Puder said, one of the study’s strengths was that it showed how depressive symptoms increased during the COVID lockdown. “It shows certain groups are at higher risk, including those with less financial resources and those with higher amounts of stress,” Dr. Puder said.

Ms. Ettman, Dr. Galea, and Dr. Puder reported no relevant disclosures.

FROM LANCET REGIONAL HEALTH – AMERICAS

Old wives’ tales, traditional medicine, and science

Sixteen-year-old Ana and is sitting on the bench with her science teacher, Ms. Tehrani, waiting for the bus to take them back to their village after school. Ana wants to hear her science teacher’s opinion about her grandmother.

Do you respect your grandmother?

Why yes, of course, why to do you ask?

So you think my grandmother is wise when she tells me old wife tales?

Like what?

Well, she says not to take my medicine because it will have bad effects and that I should take her remedies instead.

What else does she tell you?

Well, she says that people are born how they are and that they belong to either God or the Devil, not to their parents.

What else?

She thinks I am a fay child; she has always said that about me.

What does that mean?

It means that I have my own ways, fairy ways, and that I should go out in the forest and listen.

Do you?

Yes.

What do you hear?

I hear about my destiny.

What do you hear?

I hear that I must wash in witch hazel. My grandmother taught me how to find it and how to prepare it. She said I should sit in the forest and wait for a sign.

What sign?

I don’t know.

Well, what do you think about your grandmother?

I love her but …

But what?

I think she might be wrong about all of this, you know, science and all that.

But you do it, anyway?

Yes.

Why?

Aren’t we supposed to respect our elders, and aren’t they supposed to be wise?

Ms. Tehrani is in a bind. What to say? She has no ready answer, feeling caught between two beliefs: the unscientific basis of ineffective old wives’ treatments and the purported wisdom of our elders. She knows Ana’s family and that there are women in that family going back generations who are identified as medicine women or women with the special powers of the forest.

Ana wants to study science but she is being groomed as the family wise mother. Ana is caught between the ways of the past and the ways of the future. She sees that to go with the future is to devalue her family tradition. If she chooses to study medicine, can she keep the balance between magical ways and the ways of science?

Ms. Tehrani decides to expose her class to Indigenous and preindustrial cultural practices and what science has to say. She describes how knowledge is passed down through the generations, and how some of this knowledge has now been proved correct by science, such as the use of opium for pain management and how some knowledge has been corrected by science. She asks the class: What myths have been passed down in your family that science has shown to be effective or ineffective? What does science have to say about how we live our lives?

After a baby in the village dies, Ms. Tehrani asks the local health center to think about implementing a teaching course on caring for babies, a course that will discuss tradition and science. She is well aware of the fact that Black mothers tend not to follow the advice of the pediatricians who now recommend that parents put babies to sleep on their backs. Black women trust the advice of their paternal and maternal grandmothers more than the advice of health care providers, research by Deborah Stiffler, PhD, RN, CNM, shows (J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2018 Apr;23[2]:e12213). While new Black mothers feel that they have limited knowledge and are eager to learn about safe sleep practices, their grandmothers were skeptical – and the grandmothers often won that argument. Black mothers believed that their own mothers knew best, based on their experience raising infants.

In Dr. Stiffler’s study, one grandmother commented: “Girls today need a mother to help them take care of their babies. They don’t know how to do anything. When I was growing up, our moms helped us.”

One new mother said: I “listen more to the elderly people because like the social workers and stuff some of them don’t have kids. They just go by the book … so I feel like I listen more to like my grandparents.”

Integrating traditions

When Ana enters medical school she is faced with the task of integration of traditional practice and Western medicine. Ana looks to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), the U.S. government’s lead agency for scientific research on complementary and integrative health approaches for support in her task. The NCCIH was established in 1998 with the mission of determining the usefulness and safety of complementary and integrative health approaches, and their roles in improving health and health care.

The NCCIH notes that more than 30% of adults use health care approaches that are not part of conventional medical care or that have origins outside of usual Western practice, and 17.7% of American adults had used a dietary supplement other than vitamins and minerals in the past year, most commonly fish oil. This agency notes that large rigorous research studies extend to only a few dietary supplements, with results showing that the products didn’t work for the conditions studied. The work of the NCCIH is mirrored worldwide.

The 2008 Beijing Declaration called on World Health Organization member states and other stakeholders to integrate traditional medicine and complementary alternative medicines into national health care systems. The WHO Congress on Traditional Medicine recognizes that traditional medicine (TM) may be more affordable and accessible than Western medicine, and that it plays an important role in meeting the demands of primary health care in many developing countries. From 70% to 80% of the population in India and Ethiopia depend on TM for primary health care, and 70% of the population in Canada and 80% in Germany are reported to have used TM as complementary and/or alternative medical treatment.

After graduation and residency, Ana returns to her village and helps her science teacher consider how best to shape the intergenerational transmission of knowledge, so that it is both honored by the elders and also shaped by the science of medicine.

Every village, regardless of where it is in the world, has to contend with finding the balance between the traditional medical knowledge that is passed down through the family and the discoveries of science. When it comes to practicing medicine and psychiatry, a respect for family tradition must be weighed against the application of science: this is a long conversation that is well worth its time.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). Dr. Heru has no conflicts of interest. Contact Dr. Heru at alison.heru@cuanschutz.edu.

Sixteen-year-old Ana and is sitting on the bench with her science teacher, Ms. Tehrani, waiting for the bus to take them back to their village after school. Ana wants to hear her science teacher’s opinion about her grandmother.

Do you respect your grandmother?

Why yes, of course, why to do you ask?

So you think my grandmother is wise when she tells me old wife tales?

Like what?

Well, she says not to take my medicine because it will have bad effects and that I should take her remedies instead.

What else does she tell you?

Well, she says that people are born how they are and that they belong to either God or the Devil, not to their parents.

What else?

She thinks I am a fay child; she has always said that about me.

What does that mean?

It means that I have my own ways, fairy ways, and that I should go out in the forest and listen.

Do you?

Yes.

What do you hear?

I hear about my destiny.

What do you hear?

I hear that I must wash in witch hazel. My grandmother taught me how to find it and how to prepare it. She said I should sit in the forest and wait for a sign.

What sign?

I don’t know.

Well, what do you think about your grandmother?

I love her but …

But what?

I think she might be wrong about all of this, you know, science and all that.

But you do it, anyway?

Yes.

Why?

Aren’t we supposed to respect our elders, and aren’t they supposed to be wise?

Ms. Tehrani is in a bind. What to say? She has no ready answer, feeling caught between two beliefs: the unscientific basis of ineffective old wives’ treatments and the purported wisdom of our elders. She knows Ana’s family and that there are women in that family going back generations who are identified as medicine women or women with the special powers of the forest.

Ana wants to study science but she is being groomed as the family wise mother. Ana is caught between the ways of the past and the ways of the future. She sees that to go with the future is to devalue her family tradition. If she chooses to study medicine, can she keep the balance between magical ways and the ways of science?

Ms. Tehrani decides to expose her class to Indigenous and preindustrial cultural practices and what science has to say. She describes how knowledge is passed down through the generations, and how some of this knowledge has now been proved correct by science, such as the use of opium for pain management and how some knowledge has been corrected by science. She asks the class: What myths have been passed down in your family that science has shown to be effective or ineffective? What does science have to say about how we live our lives?

After a baby in the village dies, Ms. Tehrani asks the local health center to think about implementing a teaching course on caring for babies, a course that will discuss tradition and science. She is well aware of the fact that Black mothers tend not to follow the advice of the pediatricians who now recommend that parents put babies to sleep on their backs. Black women trust the advice of their paternal and maternal grandmothers more than the advice of health care providers, research by Deborah Stiffler, PhD, RN, CNM, shows (J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2018 Apr;23[2]:e12213). While new Black mothers feel that they have limited knowledge and are eager to learn about safe sleep practices, their grandmothers were skeptical – and the grandmothers often won that argument. Black mothers believed that their own mothers knew best, based on their experience raising infants.

In Dr. Stiffler’s study, one grandmother commented: “Girls today need a mother to help them take care of their babies. They don’t know how to do anything. When I was growing up, our moms helped us.”

One new mother said: I “listen more to the elderly people because like the social workers and stuff some of them don’t have kids. They just go by the book … so I feel like I listen more to like my grandparents.”

Integrating traditions

When Ana enters medical school she is faced with the task of integration of traditional practice and Western medicine. Ana looks to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), the U.S. government’s lead agency for scientific research on complementary and integrative health approaches for support in her task. The NCCIH was established in 1998 with the mission of determining the usefulness and safety of complementary and integrative health approaches, and their roles in improving health and health care.