User login

A Facility-Wide Plan to Increase Access to Medication for Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care and General Mental Health Settings

In the United States, opioid use disorder (OUD) is a major public health challenge. In 2018 drug overdose deaths were 4 times higher than they were in 1999.1 This increase highlights a critical need to expand treatment access. Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, improves outcomes for patients retained in care.2 Compared with the general population, veterans, particularly those with co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, are more likely to receive higher dosages of opioid medications and experience opioid-related adverse outcomes (eg, overdose, OUD).3,4 As a risk reduction strategy, patients receiving potentially dangerous full-dose agonist opioid medication who are unable to taper to safer dosages may be eligible to transition to buprenorphine.5

Buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed in office-based settings or in addiction, primary care, mental health, and pain clinics. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B) expands access to patients who are not reached by addiction treatment programs.6,7 This is particularly true in rural settings, where addiction care services are typically scarce.8 OBOT-B prevents relapse and maintains opioid-free days and may increase patient engagement by reducing stigma and providing treatment within an existing clinical care team.9 For many patients, OBOT-B results in good retention with just medical monitoring and minimal or no ancillary addiction counseling.10,11

Successful implementation of OBOT-B has occurred through a variety of care models in selected community health care settings.8,12,13 Historically in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), MOUD has been prescribed in substance use disorder clinics by mental health practitioners. Currently, more than 44% of veterans with OUD are on MOUD.14

The VHA has invested significant resources to improve access to MOUD. In 2018, the Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative launched, with the aim to improve access within primary care, mental health, and pain clinics.15 SCOUTT emphasizes stepped-care treatment, with patients engaging in the step of care most appropriate to their needs. Step 0 is self-directed care/self-management, including mutual support groups; step-1 environments include office-based primary care, mental health, and pain clinics; and step-2 environments are specialty care settings. Through a series of remote webinars, an in-person national 2-day conference, and external facilitation, SCOUTT engaged 18 teams representing each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) across the country to assist in implementing MOUD within 2 step-1 clinics. These teams have developed several models of providing step-1 care, including an interdisciplinary team-based primary care delivery model as well as a pharmacist care manager model.16, 17

US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Health Care System (VACHS), which delivers care to approximately 58,000 veterans, was chosen to be a phase 1 SCOUTT site. Though all patients in VACHS have access to specialty care step-2 clinics, including methadone and buprenorphine programs, there remained many patients not yet on MOUD who could benefit from it. Baseline data (fiscal year [FY] 2018 4th quarter), obtained through electronic health record (EHR) database dashboards indicated that 710 (56%) patients with an OUD diagnosis were not receiving MOUD. International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision codes are the foundation for VA population management dashboards, and based their data on codes for opioid abuse and opioid dependence. These tools are limited by the accuracy of coding in EHRs. Additionally, 366 patients receiving long-term opioid prescriptions were identified as moderate, high, or very high risk for overdose or death based on an algorithm that considered prescribed medications, sociodemographics, and comorbid conditions, as characterized in the VA EHR (Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation [STORM] report).18

This article describes the VACHSquality-improvement effort to extend OBOT-B into step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics. Our objectives are to (1) outline the process for initiating SCOUTT within VACHS; (2) examine barriers to implementation and the SCOUTT team response; (3) review VACHS patient and prescriber data at baseline and 1 year after implementation; and (4) explore future implementation strategies.

SCOUTT Team

A VACHS interdisciplinary team was formed and attended the national SCOUTT kickoff conference in 2018.15 Similar to other SCOUTT teams, the team consisted of VISN leadership (in primary care, mental health, and addiction care), pharmacists, and a team of health care practitioners (HCPs) from step-2 clinics (including 2 addiction psychiatrists, and an advanced practice registered nurse, a registered nurse specializing in addiction care), and a team of HCPs from prospective step-1 clinics (including a clinical psychologist and 2 primary care physicians). An external facilitator was provided from outside the VISN who met remotely with the team to assist in facilitation. Our team met monthly, with the goal to identify local barriers and facilitators to OBOT-B and implement interventions to enhance prescribing in step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics.

Implementation Steps

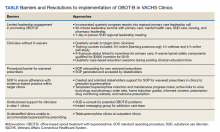

The team identified multiple barriers to dissemination of OBOT-B in target clinics (Table). The 3 main barriers were limited leadership engagement in promoting OBOT-B in target clinics, inadequate number of HCPs with active X-waivered prescribing status in the targeted clinics, and the need for standardized processes and tools to facilitate prescribing and follow-up.

To address leadership engagement, the SCOUTT team held quarterly presentations of SCOUTT goals and progress on target clinic leadership calls (usually 15 minutes) and arranged a 90-minute multidisciplinary leadership summit with key leadership representation from primary care, general mental health, specialty addiction care, nursing, and pharmacy. To enhance X-waivered prescribers in target clinics, the SCOUTT team sent quarterly emails with brief education points on MOUD and links to waiver trainings. At the time of implementation, in order to prescribe buprenorphine and meet qualifications to treat OUD, prescribers were required to complete specialized training as necessitated by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000. X-waivered status can now be obtained without requiring training

The SCOUTT team advocated for X-waivered status to be incentivized by performance pay for primary care practitioners and held quarterly case-based education sessions during preexisting allotted time. The onboarding process for new waivered prescribers to navigate from waiver training to active prescribing within the EHR was standardized via development of a standard operating procedure (SOP).

The SCOUTT team also assisted in the development of standardized processes and tools for prescribing in target clinics, including implementation of a standard operating procedure regarding prescribing (both initiation of buprenorphine, and maintenance) in target clinics. This procedure specifies that target clinic HCPs prescribe for patients requiring less intensive management, and who are appropriate for office-based treatment based on specific criteria (eAppendix

Templated progress notes were created for buprenorphine initiation and buprenorphine maintenance with links to recommended laboratory tests and urine toxicology test ordering, home induction guides, prescription drug monitoring database, naloxone prescribing, and pharmacy order sets. Communication with specialty HCPs was facilitated by development of e-consultation within the EHR and instant messaging options within the local intranet. In the SCOUTT team model, the prescriber independently completed assessment/follow-up without nursing or clinical pharmacy support.

Analysis

We examined changes in MOUD receipt and prescriber characteristics at baseline (FY 2018 4th quarter) and 1 year after implementation (FY 2019 4th quarter). Patient data were extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which contains data from all VHA EHRs. The VA STORM, is a CDW tool that automatically flags patients prescribed opioids who are at risk for overdose and suicide. Prescriber data were obtained from the Buprenorphine/X-Waivered Provider Report, a VA Academic Detailing Service database that provides details on HCP type, X-waivered status, and prescribing by location. χ2 analyses were conducted on before and after measures when total values were available.

Results

There was a 4% increase in patients with an OUD diagnosis receiving MOUD, from 552 (44%) to 582 (48%) (P = .04), over this time. The number of waivered prescribers increased from 67 to 131, the number of prescribers of buprenorphine in a 6-month span increased from 35 to 52, and the percentage of HCPs capable of prescribing within the EHR increased from 75% to 89% (P =.01).

Initially, addiction HCPs prescribed to about 68% of patients on buprenorphine, with target clinic HCPs prescribing to 24% (with the remaining coming from other specialty HCPs). On follow-up, addiction professionals prescribed to 63%, with target clinic clincians prescribing to 32%.

Interpretation

SCOUTT team interventions succeeded in increasing the number of patients receiving MOUD, a substantial increase in waivered HCPs, an increase in the number of waivered HCPs prescribing MOUD, and an increase in the proportion of patients receiving MOUD in step-1 target clinics. It is important to note that within the quality-improvement framework and goals of our SCOUTT team that the data were not collected as part of a research study but to assess impact of our interventions. Within this framework, it is not possible to directly attribute the increase in eligible patients receiving MOUD solely to SCOUTT team interventions, as other factors may have contributed, including improved awareness of HCPs.

Summary and Future Directions

Since implementation of SCOUTT in August 2018, VACHS has identified several barriers to buprenorphine prescribing in step-1 clinics and implemented strategies to overcome them. Describing our approach will hopefully inform other large health care systems (VA or non-VA) on changes required in order to scale up implementation of OBOT-B. The VACHS SCOUTT team was successful at enhancing a ready workforce in step-1 clinics, though noted a delay in changing prescribing practice and culture.

We recommend utilizing academic detailing to work with clinics and individual HCPs to identify and overcome barriers to prescribing. Also, we recommend implementation of a nursing or clinical pharmacy collaborative care model in target step-1 clinics (rather than the HCP-driven model). A collaborative care model reflects the patient aligned care team (PACT) principle of team-based efficient care, and PACT nurses or clinical pharmacists should be able to provide the minimal quarterly follow-up of clinically stable patients on MOUD within the step-1 clinics. Templated notes for assessment, initiation, and follow-up of patients on MOUD are now available from the SCOUTT national program and should be broadly implemented to facilitate adoption of the collaborative model in target clinics. In order to accomplish a full collaborative model, the VHA would need to enhance appropriate staffing to support this model, broaden access to telehealth, and expand incentives to teams/clinicians who prescribe in these settings.

Acknowledgments/Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, Veterans Health Administration; the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Partnered Evaluation Initiative (PEC) grants #19-001. Supporting organizations had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the epidemic. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

2. Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1760-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2

3. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan [published correction appears in JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2489]. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.234

4. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, et al. Trends and regional variation in opioid overdose mortality among Veterans Health Administration patients, fiscal year 2001 to 2009. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):605-612. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000011

5. US Department of Health and Human Services, Working Group on Patient-Centered Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-term Opioid Analgesics. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of Long-term opioid analgesics. Published October 2019. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf

6. Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113-116. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008

7. LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010

8. Rubin R. Rural veterans less likely to get medication for opioid use disorder. JAMA. 2020;323(4):300. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21856

9. Kahan M, Srivastava A, Ordean A, Cirone S. Buprenorphine: new treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):281-289.

10. Fiellin DA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, et al. Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: results at 2-5 years. Am J Addict. 2008;17(2):116-120. doi:10.1080/10550490701860971

11. Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055255

12. Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Integrating buprenorphine maintenance therapy into federally qualified health centers: real-world substance abuse treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):127-135. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.008

13. Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171-176. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1

14. Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: Historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):139-144. doi:10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327

15. Gordon AJ, Drexler K, Hawkins EJ, et al. Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative: Expanding access to medication treatment for opioid use disorder within Veterans Health Administration facilities. Subst Abus. 2020;41(3):275-282. doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1787299

16. Codell N, Kelley AT, Jones AL, et al. Aims, development, and early results of an interdisciplinary primary care initiative to address patient vulnerabilities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(2):160-169. doi:10.1080/00952990.2020.1832507

17. DeRonne BM, Wong KR, Schultz E, Jones E, Krebs EE. Implementation of a pharmacist care manager model to expand availability of medications for opioid use disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):354-359. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa405

18. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

19. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Published February 2017. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/resources/docs/mental-health/substance-abuse/VA_DoD-CLINICAL-PRACTICE-GUIDELINE-FOR-OPIOID-THERAPY-FOR-CHRONIC-PAIN-508.pdf

In the United States, opioid use disorder (OUD) is a major public health challenge. In 2018 drug overdose deaths were 4 times higher than they were in 1999.1 This increase highlights a critical need to expand treatment access. Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, improves outcomes for patients retained in care.2 Compared with the general population, veterans, particularly those with co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, are more likely to receive higher dosages of opioid medications and experience opioid-related adverse outcomes (eg, overdose, OUD).3,4 As a risk reduction strategy, patients receiving potentially dangerous full-dose agonist opioid medication who are unable to taper to safer dosages may be eligible to transition to buprenorphine.5

Buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed in office-based settings or in addiction, primary care, mental health, and pain clinics. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B) expands access to patients who are not reached by addiction treatment programs.6,7 This is particularly true in rural settings, where addiction care services are typically scarce.8 OBOT-B prevents relapse and maintains opioid-free days and may increase patient engagement by reducing stigma and providing treatment within an existing clinical care team.9 For many patients, OBOT-B results in good retention with just medical monitoring and minimal or no ancillary addiction counseling.10,11

Successful implementation of OBOT-B has occurred through a variety of care models in selected community health care settings.8,12,13 Historically in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), MOUD has been prescribed in substance use disorder clinics by mental health practitioners. Currently, more than 44% of veterans with OUD are on MOUD.14

The VHA has invested significant resources to improve access to MOUD. In 2018, the Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative launched, with the aim to improve access within primary care, mental health, and pain clinics.15 SCOUTT emphasizes stepped-care treatment, with patients engaging in the step of care most appropriate to their needs. Step 0 is self-directed care/self-management, including mutual support groups; step-1 environments include office-based primary care, mental health, and pain clinics; and step-2 environments are specialty care settings. Through a series of remote webinars, an in-person national 2-day conference, and external facilitation, SCOUTT engaged 18 teams representing each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) across the country to assist in implementing MOUD within 2 step-1 clinics. These teams have developed several models of providing step-1 care, including an interdisciplinary team-based primary care delivery model as well as a pharmacist care manager model.16, 17

US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Health Care System (VACHS), which delivers care to approximately 58,000 veterans, was chosen to be a phase 1 SCOUTT site. Though all patients in VACHS have access to specialty care step-2 clinics, including methadone and buprenorphine programs, there remained many patients not yet on MOUD who could benefit from it. Baseline data (fiscal year [FY] 2018 4th quarter), obtained through electronic health record (EHR) database dashboards indicated that 710 (56%) patients with an OUD diagnosis were not receiving MOUD. International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision codes are the foundation for VA population management dashboards, and based their data on codes for opioid abuse and opioid dependence. These tools are limited by the accuracy of coding in EHRs. Additionally, 366 patients receiving long-term opioid prescriptions were identified as moderate, high, or very high risk for overdose or death based on an algorithm that considered prescribed medications, sociodemographics, and comorbid conditions, as characterized in the VA EHR (Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation [STORM] report).18

This article describes the VACHSquality-improvement effort to extend OBOT-B into step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics. Our objectives are to (1) outline the process for initiating SCOUTT within VACHS; (2) examine barriers to implementation and the SCOUTT team response; (3) review VACHS patient and prescriber data at baseline and 1 year after implementation; and (4) explore future implementation strategies.

SCOUTT Team

A VACHS interdisciplinary team was formed and attended the national SCOUTT kickoff conference in 2018.15 Similar to other SCOUTT teams, the team consisted of VISN leadership (in primary care, mental health, and addiction care), pharmacists, and a team of health care practitioners (HCPs) from step-2 clinics (including 2 addiction psychiatrists, and an advanced practice registered nurse, a registered nurse specializing in addiction care), and a team of HCPs from prospective step-1 clinics (including a clinical psychologist and 2 primary care physicians). An external facilitator was provided from outside the VISN who met remotely with the team to assist in facilitation. Our team met monthly, with the goal to identify local barriers and facilitators to OBOT-B and implement interventions to enhance prescribing in step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics.

Implementation Steps

The team identified multiple barriers to dissemination of OBOT-B in target clinics (Table). The 3 main barriers were limited leadership engagement in promoting OBOT-B in target clinics, inadequate number of HCPs with active X-waivered prescribing status in the targeted clinics, and the need for standardized processes and tools to facilitate prescribing and follow-up.

To address leadership engagement, the SCOUTT team held quarterly presentations of SCOUTT goals and progress on target clinic leadership calls (usually 15 minutes) and arranged a 90-minute multidisciplinary leadership summit with key leadership representation from primary care, general mental health, specialty addiction care, nursing, and pharmacy. To enhance X-waivered prescribers in target clinics, the SCOUTT team sent quarterly emails with brief education points on MOUD and links to waiver trainings. At the time of implementation, in order to prescribe buprenorphine and meet qualifications to treat OUD, prescribers were required to complete specialized training as necessitated by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000. X-waivered status can now be obtained without requiring training

The SCOUTT team advocated for X-waivered status to be incentivized by performance pay for primary care practitioners and held quarterly case-based education sessions during preexisting allotted time. The onboarding process for new waivered prescribers to navigate from waiver training to active prescribing within the EHR was standardized via development of a standard operating procedure (SOP).

The SCOUTT team also assisted in the development of standardized processes and tools for prescribing in target clinics, including implementation of a standard operating procedure regarding prescribing (both initiation of buprenorphine, and maintenance) in target clinics. This procedure specifies that target clinic HCPs prescribe for patients requiring less intensive management, and who are appropriate for office-based treatment based on specific criteria (eAppendix

Templated progress notes were created for buprenorphine initiation and buprenorphine maintenance with links to recommended laboratory tests and urine toxicology test ordering, home induction guides, prescription drug monitoring database, naloxone prescribing, and pharmacy order sets. Communication with specialty HCPs was facilitated by development of e-consultation within the EHR and instant messaging options within the local intranet. In the SCOUTT team model, the prescriber independently completed assessment/follow-up without nursing or clinical pharmacy support.

Analysis

We examined changes in MOUD receipt and prescriber characteristics at baseline (FY 2018 4th quarter) and 1 year after implementation (FY 2019 4th quarter). Patient data were extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which contains data from all VHA EHRs. The VA STORM, is a CDW tool that automatically flags patients prescribed opioids who are at risk for overdose and suicide. Prescriber data were obtained from the Buprenorphine/X-Waivered Provider Report, a VA Academic Detailing Service database that provides details on HCP type, X-waivered status, and prescribing by location. χ2 analyses were conducted on before and after measures when total values were available.

Results

There was a 4% increase in patients with an OUD diagnosis receiving MOUD, from 552 (44%) to 582 (48%) (P = .04), over this time. The number of waivered prescribers increased from 67 to 131, the number of prescribers of buprenorphine in a 6-month span increased from 35 to 52, and the percentage of HCPs capable of prescribing within the EHR increased from 75% to 89% (P =.01).

Initially, addiction HCPs prescribed to about 68% of patients on buprenorphine, with target clinic HCPs prescribing to 24% (with the remaining coming from other specialty HCPs). On follow-up, addiction professionals prescribed to 63%, with target clinic clincians prescribing to 32%.

Interpretation

SCOUTT team interventions succeeded in increasing the number of patients receiving MOUD, a substantial increase in waivered HCPs, an increase in the number of waivered HCPs prescribing MOUD, and an increase in the proportion of patients receiving MOUD in step-1 target clinics. It is important to note that within the quality-improvement framework and goals of our SCOUTT team that the data were not collected as part of a research study but to assess impact of our interventions. Within this framework, it is not possible to directly attribute the increase in eligible patients receiving MOUD solely to SCOUTT team interventions, as other factors may have contributed, including improved awareness of HCPs.

Summary and Future Directions

Since implementation of SCOUTT in August 2018, VACHS has identified several barriers to buprenorphine prescribing in step-1 clinics and implemented strategies to overcome them. Describing our approach will hopefully inform other large health care systems (VA or non-VA) on changes required in order to scale up implementation of OBOT-B. The VACHS SCOUTT team was successful at enhancing a ready workforce in step-1 clinics, though noted a delay in changing prescribing practice and culture.

We recommend utilizing academic detailing to work with clinics and individual HCPs to identify and overcome barriers to prescribing. Also, we recommend implementation of a nursing or clinical pharmacy collaborative care model in target step-1 clinics (rather than the HCP-driven model). A collaborative care model reflects the patient aligned care team (PACT) principle of team-based efficient care, and PACT nurses or clinical pharmacists should be able to provide the minimal quarterly follow-up of clinically stable patients on MOUD within the step-1 clinics. Templated notes for assessment, initiation, and follow-up of patients on MOUD are now available from the SCOUTT national program and should be broadly implemented to facilitate adoption of the collaborative model in target clinics. In order to accomplish a full collaborative model, the VHA would need to enhance appropriate staffing to support this model, broaden access to telehealth, and expand incentives to teams/clinicians who prescribe in these settings.

Acknowledgments/Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, Veterans Health Administration; the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Partnered Evaluation Initiative (PEC) grants #19-001. Supporting organizations had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

In the United States, opioid use disorder (OUD) is a major public health challenge. In 2018 drug overdose deaths were 4 times higher than they were in 1999.1 This increase highlights a critical need to expand treatment access. Medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), including methadone, naltrexone, and buprenorphine, improves outcomes for patients retained in care.2 Compared with the general population, veterans, particularly those with co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or depression, are more likely to receive higher dosages of opioid medications and experience opioid-related adverse outcomes (eg, overdose, OUD).3,4 As a risk reduction strategy, patients receiving potentially dangerous full-dose agonist opioid medication who are unable to taper to safer dosages may be eligible to transition to buprenorphine.5

Buprenorphine and naltrexone can be prescribed in office-based settings or in addiction, primary care, mental health, and pain clinics. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B) expands access to patients who are not reached by addiction treatment programs.6,7 This is particularly true in rural settings, where addiction care services are typically scarce.8 OBOT-B prevents relapse and maintains opioid-free days and may increase patient engagement by reducing stigma and providing treatment within an existing clinical care team.9 For many patients, OBOT-B results in good retention with just medical monitoring and minimal or no ancillary addiction counseling.10,11

Successful implementation of OBOT-B has occurred through a variety of care models in selected community health care settings.8,12,13 Historically in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), MOUD has been prescribed in substance use disorder clinics by mental health practitioners. Currently, more than 44% of veterans with OUD are on MOUD.14

The VHA has invested significant resources to improve access to MOUD. In 2018, the Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative launched, with the aim to improve access within primary care, mental health, and pain clinics.15 SCOUTT emphasizes stepped-care treatment, with patients engaging in the step of care most appropriate to their needs. Step 0 is self-directed care/self-management, including mutual support groups; step-1 environments include office-based primary care, mental health, and pain clinics; and step-2 environments are specialty care settings. Through a series of remote webinars, an in-person national 2-day conference, and external facilitation, SCOUTT engaged 18 teams representing each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) across the country to assist in implementing MOUD within 2 step-1 clinics. These teams have developed several models of providing step-1 care, including an interdisciplinary team-based primary care delivery model as well as a pharmacist care manager model.16, 17

US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Health Care System (VACHS), which delivers care to approximately 58,000 veterans, was chosen to be a phase 1 SCOUTT site. Though all patients in VACHS have access to specialty care step-2 clinics, including methadone and buprenorphine programs, there remained many patients not yet on MOUD who could benefit from it. Baseline data (fiscal year [FY] 2018 4th quarter), obtained through electronic health record (EHR) database dashboards indicated that 710 (56%) patients with an OUD diagnosis were not receiving MOUD. International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision codes are the foundation for VA population management dashboards, and based their data on codes for opioid abuse and opioid dependence. These tools are limited by the accuracy of coding in EHRs. Additionally, 366 patients receiving long-term opioid prescriptions were identified as moderate, high, or very high risk for overdose or death based on an algorithm that considered prescribed medications, sociodemographics, and comorbid conditions, as characterized in the VA EHR (Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation [STORM] report).18

This article describes the VACHSquality-improvement effort to extend OBOT-B into step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics. Our objectives are to (1) outline the process for initiating SCOUTT within VACHS; (2) examine barriers to implementation and the SCOUTT team response; (3) review VACHS patient and prescriber data at baseline and 1 year after implementation; and (4) explore future implementation strategies.

SCOUTT Team

A VACHS interdisciplinary team was formed and attended the national SCOUTT kickoff conference in 2018.15 Similar to other SCOUTT teams, the team consisted of VISN leadership (in primary care, mental health, and addiction care), pharmacists, and a team of health care practitioners (HCPs) from step-2 clinics (including 2 addiction psychiatrists, and an advanced practice registered nurse, a registered nurse specializing in addiction care), and a team of HCPs from prospective step-1 clinics (including a clinical psychologist and 2 primary care physicians). An external facilitator was provided from outside the VISN who met remotely with the team to assist in facilitation. Our team met monthly, with the goal to identify local barriers and facilitators to OBOT-B and implement interventions to enhance prescribing in step-1 primary care and general mental health clinics.

Implementation Steps

The team identified multiple barriers to dissemination of OBOT-B in target clinics (Table). The 3 main barriers were limited leadership engagement in promoting OBOT-B in target clinics, inadequate number of HCPs with active X-waivered prescribing status in the targeted clinics, and the need for standardized processes and tools to facilitate prescribing and follow-up.

To address leadership engagement, the SCOUTT team held quarterly presentations of SCOUTT goals and progress on target clinic leadership calls (usually 15 minutes) and arranged a 90-minute multidisciplinary leadership summit with key leadership representation from primary care, general mental health, specialty addiction care, nursing, and pharmacy. To enhance X-waivered prescribers in target clinics, the SCOUTT team sent quarterly emails with brief education points on MOUD and links to waiver trainings. At the time of implementation, in order to prescribe buprenorphine and meet qualifications to treat OUD, prescribers were required to complete specialized training as necessitated by the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000. X-waivered status can now be obtained without requiring training

The SCOUTT team advocated for X-waivered status to be incentivized by performance pay for primary care practitioners and held quarterly case-based education sessions during preexisting allotted time. The onboarding process for new waivered prescribers to navigate from waiver training to active prescribing within the EHR was standardized via development of a standard operating procedure (SOP).

The SCOUTT team also assisted in the development of standardized processes and tools for prescribing in target clinics, including implementation of a standard operating procedure regarding prescribing (both initiation of buprenorphine, and maintenance) in target clinics. This procedure specifies that target clinic HCPs prescribe for patients requiring less intensive management, and who are appropriate for office-based treatment based on specific criteria (eAppendix

Templated progress notes were created for buprenorphine initiation and buprenorphine maintenance with links to recommended laboratory tests and urine toxicology test ordering, home induction guides, prescription drug monitoring database, naloxone prescribing, and pharmacy order sets. Communication with specialty HCPs was facilitated by development of e-consultation within the EHR and instant messaging options within the local intranet. In the SCOUTT team model, the prescriber independently completed assessment/follow-up without nursing or clinical pharmacy support.

Analysis

We examined changes in MOUD receipt and prescriber characteristics at baseline (FY 2018 4th quarter) and 1 year after implementation (FY 2019 4th quarter). Patient data were extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), which contains data from all VHA EHRs. The VA STORM, is a CDW tool that automatically flags patients prescribed opioids who are at risk for overdose and suicide. Prescriber data were obtained from the Buprenorphine/X-Waivered Provider Report, a VA Academic Detailing Service database that provides details on HCP type, X-waivered status, and prescribing by location. χ2 analyses were conducted on before and after measures when total values were available.

Results

There was a 4% increase in patients with an OUD diagnosis receiving MOUD, from 552 (44%) to 582 (48%) (P = .04), over this time. The number of waivered prescribers increased from 67 to 131, the number of prescribers of buprenorphine in a 6-month span increased from 35 to 52, and the percentage of HCPs capable of prescribing within the EHR increased from 75% to 89% (P =.01).

Initially, addiction HCPs prescribed to about 68% of patients on buprenorphine, with target clinic HCPs prescribing to 24% (with the remaining coming from other specialty HCPs). On follow-up, addiction professionals prescribed to 63%, with target clinic clincians prescribing to 32%.

Interpretation

SCOUTT team interventions succeeded in increasing the number of patients receiving MOUD, a substantial increase in waivered HCPs, an increase in the number of waivered HCPs prescribing MOUD, and an increase in the proportion of patients receiving MOUD in step-1 target clinics. It is important to note that within the quality-improvement framework and goals of our SCOUTT team that the data were not collected as part of a research study but to assess impact of our interventions. Within this framework, it is not possible to directly attribute the increase in eligible patients receiving MOUD solely to SCOUTT team interventions, as other factors may have contributed, including improved awareness of HCPs.

Summary and Future Directions

Since implementation of SCOUTT in August 2018, VACHS has identified several barriers to buprenorphine prescribing in step-1 clinics and implemented strategies to overcome them. Describing our approach will hopefully inform other large health care systems (VA or non-VA) on changes required in order to scale up implementation of OBOT-B. The VACHS SCOUTT team was successful at enhancing a ready workforce in step-1 clinics, though noted a delay in changing prescribing practice and culture.

We recommend utilizing academic detailing to work with clinics and individual HCPs to identify and overcome barriers to prescribing. Also, we recommend implementation of a nursing or clinical pharmacy collaborative care model in target step-1 clinics (rather than the HCP-driven model). A collaborative care model reflects the patient aligned care team (PACT) principle of team-based efficient care, and PACT nurses or clinical pharmacists should be able to provide the minimal quarterly follow-up of clinically stable patients on MOUD within the step-1 clinics. Templated notes for assessment, initiation, and follow-up of patients on MOUD are now available from the SCOUTT national program and should be broadly implemented to facilitate adoption of the collaborative model in target clinics. In order to accomplish a full collaborative model, the VHA would need to enhance appropriate staffing to support this model, broaden access to telehealth, and expand incentives to teams/clinicians who prescribe in these settings.

Acknowledgments/Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, Veterans Health Administration; the VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) Partnered Evaluation Initiative (PEC) grants #19-001. Supporting organizations had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the epidemic. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

2. Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1760-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2

3. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan [published correction appears in JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2489]. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.234

4. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, et al. Trends and regional variation in opioid overdose mortality among Veterans Health Administration patients, fiscal year 2001 to 2009. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):605-612. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000011

5. US Department of Health and Human Services, Working Group on Patient-Centered Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-term Opioid Analgesics. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of Long-term opioid analgesics. Published October 2019. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf

6. Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113-116. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008

7. LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010

8. Rubin R. Rural veterans less likely to get medication for opioid use disorder. JAMA. 2020;323(4):300. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21856

9. Kahan M, Srivastava A, Ordean A, Cirone S. Buprenorphine: new treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):281-289.

10. Fiellin DA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, et al. Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: results at 2-5 years. Am J Addict. 2008;17(2):116-120. doi:10.1080/10550490701860971

11. Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055255

12. Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Integrating buprenorphine maintenance therapy into federally qualified health centers: real-world substance abuse treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):127-135. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.008

13. Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171-176. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1

14. Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: Historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):139-144. doi:10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327

15. Gordon AJ, Drexler K, Hawkins EJ, et al. Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative: Expanding access to medication treatment for opioid use disorder within Veterans Health Administration facilities. Subst Abus. 2020;41(3):275-282. doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1787299

16. Codell N, Kelley AT, Jones AL, et al. Aims, development, and early results of an interdisciplinary primary care initiative to address patient vulnerabilities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(2):160-169. doi:10.1080/00952990.2020.1832507

17. DeRonne BM, Wong KR, Schultz E, Jones E, Krebs EE. Implementation of a pharmacist care manager model to expand availability of medications for opioid use disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):354-359. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa405

18. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

19. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Published February 2017. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/resources/docs/mental-health/substance-abuse/VA_DoD-CLINICAL-PRACTICE-GUIDELINE-FOR-OPIOID-THERAPY-FOR-CHRONIC-PAIN-508.pdf

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding the epidemic. Updated March 17, 2021. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

2. Blanco C, Volkow ND. Management of opioid use disorder in the USA: present status and future directions. Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1760-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33078-2

3. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan [published correction appears in JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2489]. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.234

4. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, et al. Trends and regional variation in opioid overdose mortality among Veterans Health Administration patients, fiscal year 2001 to 2009. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(7):605-612. doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000011

5. US Department of Health and Human Services, Working Group on Patient-Centered Reduction or Discontinuation of Long-term Opioid Analgesics. HHS guide for clinicians on the appropriate dosage reduction or discontinuation of Long-term opioid analgesics. Published October 2019. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2019-10/Dosage_Reduction_Discontinuation.pdf

6. Sullivan LE, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS, Fiellin DA. The practice of office-based buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: is it associated with new patients entering into treatment?. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79(1):113-116. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.008

7. LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6-13. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010

8. Rubin R. Rural veterans less likely to get medication for opioid use disorder. JAMA. 2020;323(4):300. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21856

9. Kahan M, Srivastava A, Ordean A, Cirone S. Buprenorphine: new treatment of opioid addiction in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):281-289.

10. Fiellin DA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, et al. Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: results at 2-5 years. Am J Addict. 2008;17(2):116-120. doi:10.1080/10550490701860971

11. Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365-374. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055255

12. Haddad MS, Zelenev A, Altice FL. Integrating buprenorphine maintenance therapy into federally qualified health centers: real-world substance abuse treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):127-135. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.008

13. Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, et al. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(2):171-176. doi:10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1

14. Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: Historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):139-144. doi:10.1080/08897077.2018.1452327

15. Gordon AJ, Drexler K, Hawkins EJ, et al. Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder Train the Trainer (SCOUTT) initiative: Expanding access to medication treatment for opioid use disorder within Veterans Health Administration facilities. Subst Abus. 2020;41(3):275-282. doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1787299

16. Codell N, Kelley AT, Jones AL, et al. Aims, development, and early results of an interdisciplinary primary care initiative to address patient vulnerabilities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(2):160-169. doi:10.1080/00952990.2020.1832507

17. DeRonne BM, Wong KR, Schultz E, Jones E, Krebs EE. Implementation of a pharmacist care manager model to expand availability of medications for opioid use disorder. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):354-359. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa405

18. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

19. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for opioid therapy for chronic pain. Published February 2017. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/resources/docs/mental-health/substance-abuse/VA_DoD-CLINICAL-PRACTICE-GUIDELINE-FOR-OPIOID-THERAPY-FOR-CHRONIC-PAIN-508.pdf

Virtual Respiratory Urgent Clinics for COVID-19 Symptoms

Virtual care (VC) has emerged as an effective mode of health care delivery especially in settings where significant barriers to traditional in-person visits exist; a large systematic review supports feasibility of telemedicine in primary care and suggests that telemedicine is at least as effective as traditional care.1 Nevertheless, broad adoption of VC into practice has lagged, impeded by government and private insurance reimbursement requirements as well as the persistent belief that care can best be delivered in person.2-4 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, states that enacted parity legislation that required private insurance companies to provide reimbursement coverage for telehealth services saw a significant increase in the number of outpatient telehealth visits (about ≥ 30% odds compared with nonparity states).3

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person medical appointments were converted to VC visits to reduce increased exposure risks to patients and health care workers.5 Prior government and private sector policies were suspended, and payment restrictions lifted, enabling adoption of VC modalities to rapidly accommodate the emergent need and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for virtual care.6-11

The CDC guidelines on managing operations during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need to provide care in the safest way for patients and health care personnel and emphasized the importance of optimizing telehealth services. The federal government facilitated telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic via temporary measures under the COVID-19 public health emergency declaration. This included Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act flexibility to use everyday technology for VC visits, regulatory changes to deliver services to Medicare and Medicaid patients, permission of telehealth services across state lines, and prescribing of controlled substances via telehealth without an in-person medical evaluation.7

In response, health care providers (HCPs) and health care organizations created or expanded on existing telehealth infrastructure, developing virtual urgent care centers and telephone-based programs to evaluate patients remotely via screening questions that triaged them to a correct level of response, with possible subsequent virtual physician evaluation if indicated.12,13

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) also shifted to a VC model in response to COVID-19 guided by a unique perspective from a well-developed prior VC experience.14-16 As a federally funded system, the VHA depends on workload documentation for budgeting. Since 2015, the VHA has provided workload credit and incentivized HCPs (via pay for performance) for the use of VC, including telephone visits, video visits, and secure messaging. These incentives resulted in higher rates of telehealth utilization before the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the private sector (with 4.2% and 0.7% of visits within the VHA being telephone and video visits, respectively, compared with telehealth utilization rates of 1.0% for Medicare recipients and 1.1% in an all-payer database).16

Historically, VHA care has successfully transitioned from in-person care models to exclusively virtual modalities to prevent suspension of medical services during natural disasters. Studies performed during these periods, specifically during the 2017 hurricane season (during which multiple VHA hospitals were closed or had limited in-person service available), supported telehealth as an efficient health care delivery method, and even recommended expanding telehealth services within non-VHA environments to accommodate needs of the general public during crises and postdisaster health care delivery.17

Armed with both a well-established telehealth infrastructure and prior knowledge gained from successful systemwide implementation of virtual care during times of disaster, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) primary care quickly transitioned to a VC model in response to COVID-19.16 Early in the pandemic, a rapid transition to virtual care (RTVC) model was developed, including implementation of virtual respiratory urgent clinics (VRUCs), defined as virtual respiratory symptom triage clinics, staffed by primary care providers (PCPs) aimed at minimizing patient and health care worker exposure risk.

Methods

VACHS consists of 8 primary care sites, including a major tertiary care center, a smaller medical center with full ambulatory services, and 6 community-based outpatient clinics with only primary care and mental health. There are 80 individual PCPs delivering care to 58,058 veterans. VRUCs were established during the COVID-19 pandemic to cover patients across the entire health care system, using a rotational schedule of VA PCPs.

COVID-19 Urgent Clinics Program

Within the first few weeks of the pandemic, VACHS primary care established VRUCS to provide expeditious virtual assessment of respiratory or flu-like symptoms. Using the established telehealth system, the intervention aimed to provide emergent screening, testing, and care to those with potential COVID-19 infections. The model also was designed to minimize exposures to the health care workforce and patients.

Retrospective analysis was performed using information obtained from the electronic health record (EHR) database to describe the characteristics of patients who received care through the VRUCs, such as demographics, era of military service, COVID-19 testing rates and results, as well as subsequent emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions. A secondary aim included collection of additional qualitative data via a random sample chart review.

Virtual clinics were established January 22, 2020, and data were analyzed over the next 3 months. Data were retrieved and analyzed from the EHR, and codes were used to categorize the VRUCs.

Results

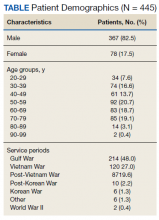

A total of 445 unique patients used these clinics during this period. Unique patients were defined as individual patients (some may have used a clinic more than once but were counted only once). Of this group, 82% were male, and 48% served in the Gulf War era (1990 to present). A total of 51% of patients received a COVID-19 test (clinics began before wide testing availability), and 10% tested positive. Of all patients using the clinics, approximately 5% were admitted to the hospital, and 18% had at least 1 subsequent ED visit (Table).

A secondary aim included review of a random sample of 99 patient charts to gain additional information regarding whether the patient was given appropriate isolation precautions, was in a high-exposure occupation (eg, could expose a large number of people), and whether there was appropriate documentation of goals of care, health care proxy or referral to social work to discuss advance directives. In addition, we calculated the average length of time between patients’ initial contact with the health care system call center and the return call by the PCP (wait time).Of charts reviewed, the majority (71%) had documentation of appropriate isolation precautions. Although 25% of patients had documentation of a high-risk profession with potential to expose many people, more than half of the patients had no documentation of occupation. Most patients (86%) had no updated documentation regarding goals of care, health care proxy, or advance directives in their urgent care VC visit. The average time between the patient initiating contact with the health care system call center and a return call to the patient from a PCP was 104 minutes (excluding calls received after 3:30

Discussion

This analysis adds to the growing literature on use of VC during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we describe the population of patients who used VRUCs within a large health care system in a RTVC. This analysis was limited by lack of available testing during the initial phase of the pandemic, which contributed to the lower than expected rates of testing and test positivity in patients managed via VRUCs. In addition, chart review data are limited as the data includes only what was documented during the visit and not the entire discussion during the encounter.

Several important outcomes from this analysis can be applied to interventions in the future, which may have large public health implications: Several hundred patients who reported respiratory symptoms were expeditiously evaluated by a PCP using VC. The average wait time to full clinical assessment was about 1.5 hours. This short duration between contact and evaluation permitted early education about isolation precautions, which may have minimized spread. In addition, this innovation kept patients out of the medical center, eliminating chains of transmission to other vulnerable patients and health care workers.

Our retrospective chart review also revealed that more than half the patients were not queried about their occupation, but of those that were asked, a significant number were in high-risk professions potentially exposing large numbers of people. This would be an important aspect to add to future templated notes to minimize work-related exposures. Also, we identified that few HCPs discussed goals of care with patients. Given the nature of COVID-19 and potential for rapid decompensation especially in vulnerable patients, this also would be important to include in the future.

Conclusions

VC urgent care clinics to address possible COVID-19 symptoms facilitated expeditious PCP assessment while keeping potentially contagious patients outside of high-risk health care environments. Streamlining and optimizing clinical VC assessments will be imperative to future management of COVID-19 and potentially to other future infectious pandemics. This includes development of templated notes incorporating counseling regarding appropriate isolation, questions about high-contact occupations, and goals of care discussions.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Robert F. Walsh, MHA.

1. Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(5):342-375. doi:10.1089/tmj.2016.0045

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Using telehealth to expand access to essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Updated June 10, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/telehealth.html

3. Harvey JB, Valenta S, Simpson K, Lyles M, McElligott J. Utilization of outpatient telehealth services in parity and nonparity states 2010-2015. Telemed J E Health. 2019;25(2):132-136. doi:10.1089/tmj.2017.0265

4. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-161. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1601705

5. Rockwell KL, Gilroy AS. Incorporating telemedicine as part of COVID-19 outbreak response systems. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(4):147-148. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2020.42784

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare facility guidance. Updated April 17, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care.html

7. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. Policy changes during COVID-19. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/policy-changes-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency

8. Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriation Act of 2020. 134 Stat. 146. Published February 2, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CREC-2021-02-02/html/CREC-2021-02-02-pt1-PgS226.htm

9. US Department of Health and Human Services. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. Updated January 20, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html

10. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Coverage and payment related to COVID-19 Medicare. 2020. Published March 23, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/03052020-medicare-covid-19-fact-sheet.pdf

11. American Telemedicine Association. ATA commends 2020 Congress for giving HHS authority to waive restrictions on telehealth for Medicare beneficiaries in response to the COVID-19 outbreak [press release]. Published March 5, 2020. Accessed August 20, 2021. https://www.americantelemed.org/press-releases/ata-commends-congress-for-waiving-restrictions-on-telehealth-for-medicare-beneficiaries-in-response-to-the-covid-19-outbreak

12. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679-1681. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2003539

13. Khairat S, Meng C, Xu Y, Edson B, Gianforcaro R. Interpreting COVID-19 and Virtual Care Trends: Cohort Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18811. Published 2020 Apr 15. doi:10.2196/18811

14. Ferguson JM, Jacobs J, Yefimova M, Greene L, Heyworth L, Zulman DM. Virtual care expansion in the Veterans Health Administration during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical services and patient characteristics associated with utilization. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(3):453-462. doi:10.1093/jamia/ocaa284

15. Baum A, Kaboli PJ, Schwartz MD. Reduced in-person and increased telehealth outpatient visits during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(1):129-131. doi:10.7326/M20-3026

16. Spelman JF, Brienza R, Walsh RF, et al. A model for rapid transition to virtual care, VA Connecticut primary care response to COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):3073-3076. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06041-4

17. Der-Martirosian C, Chu K, Dobalian A. Use of telehealth to improve access to care at the United States Department of Veterans Affairs during the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 13]. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;1-5. doi:10.1017/dmp.2020.88

Virtual care (VC) has emerged as an effective mode of health care delivery especially in settings where significant barriers to traditional in-person visits exist; a large systematic review supports feasibility of telemedicine in primary care and suggests that telemedicine is at least as effective as traditional care.1 Nevertheless, broad adoption of VC into practice has lagged, impeded by government and private insurance reimbursement requirements as well as the persistent belief that care can best be delivered in person.2-4 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, states that enacted parity legislation that required private insurance companies to provide reimbursement coverage for telehealth services saw a significant increase in the number of outpatient telehealth visits (about ≥ 30% odds compared with nonparity states).3

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person medical appointments were converted to VC visits to reduce increased exposure risks to patients and health care workers.5 Prior government and private sector policies were suspended, and payment restrictions lifted, enabling adoption of VC modalities to rapidly accommodate the emergent need and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for virtual care.6-11

The CDC guidelines on managing operations during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need to provide care in the safest way for patients and health care personnel and emphasized the importance of optimizing telehealth services. The federal government facilitated telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic via temporary measures under the COVID-19 public health emergency declaration. This included Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act flexibility to use everyday technology for VC visits, regulatory changes to deliver services to Medicare and Medicaid patients, permission of telehealth services across state lines, and prescribing of controlled substances via telehealth without an in-person medical evaluation.7

In response, health care providers (HCPs) and health care organizations created or expanded on existing telehealth infrastructure, developing virtual urgent care centers and telephone-based programs to evaluate patients remotely via screening questions that triaged them to a correct level of response, with possible subsequent virtual physician evaluation if indicated.12,13

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) also shifted to a VC model in response to COVID-19 guided by a unique perspective from a well-developed prior VC experience.14-16 As a federally funded system, the VHA depends on workload documentation for budgeting. Since 2015, the VHA has provided workload credit and incentivized HCPs (via pay for performance) for the use of VC, including telephone visits, video visits, and secure messaging. These incentives resulted in higher rates of telehealth utilization before the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the private sector (with 4.2% and 0.7% of visits within the VHA being telephone and video visits, respectively, compared with telehealth utilization rates of 1.0% for Medicare recipients and 1.1% in an all-payer database).16

Historically, VHA care has successfully transitioned from in-person care models to exclusively virtual modalities to prevent suspension of medical services during natural disasters. Studies performed during these periods, specifically during the 2017 hurricane season (during which multiple VHA hospitals were closed or had limited in-person service available), supported telehealth as an efficient health care delivery method, and even recommended expanding telehealth services within non-VHA environments to accommodate needs of the general public during crises and postdisaster health care delivery.17

Armed with both a well-established telehealth infrastructure and prior knowledge gained from successful systemwide implementation of virtual care during times of disaster, US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) primary care quickly transitioned to a VC model in response to COVID-19.16 Early in the pandemic, a rapid transition to virtual care (RTVC) model was developed, including implementation of virtual respiratory urgent clinics (VRUCs), defined as virtual respiratory symptom triage clinics, staffed by primary care providers (PCPs) aimed at minimizing patient and health care worker exposure risk.

Methods

VACHS consists of 8 primary care sites, including a major tertiary care center, a smaller medical center with full ambulatory services, and 6 community-based outpatient clinics with only primary care and mental health. There are 80 individual PCPs delivering care to 58,058 veterans. VRUCs were established during the COVID-19 pandemic to cover patients across the entire health care system, using a rotational schedule of VA PCPs.

COVID-19 Urgent Clinics Program

Within the first few weeks of the pandemic, VACHS primary care established VRUCS to provide expeditious virtual assessment of respiratory or flu-like symptoms. Using the established telehealth system, the intervention aimed to provide emergent screening, testing, and care to those with potential COVID-19 infections. The model also was designed to minimize exposures to the health care workforce and patients.

Retrospective analysis was performed using information obtained from the electronic health record (EHR) database to describe the characteristics of patients who received care through the VRUCs, such as demographics, era of military service, COVID-19 testing rates and results, as well as subsequent emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions. A secondary aim included collection of additional qualitative data via a random sample chart review.

Virtual clinics were established January 22, 2020, and data were analyzed over the next 3 months. Data were retrieved and analyzed from the EHR, and codes were used to categorize the VRUCs.

Results

A total of 445 unique patients used these clinics during this period. Unique patients were defined as individual patients (some may have used a clinic more than once but were counted only once). Of this group, 82% were male, and 48% served in the Gulf War era (1990 to present). A total of 51% of patients received a COVID-19 test (clinics began before wide testing availability), and 10% tested positive. Of all patients using the clinics, approximately 5% were admitted to the hospital, and 18% had at least 1 subsequent ED visit (Table).

A secondary aim included review of a random sample of 99 patient charts to gain additional information regarding whether the patient was given appropriate isolation precautions, was in a high-exposure occupation (eg, could expose a large number of people), and whether there was appropriate documentation of goals of care, health care proxy or referral to social work to discuss advance directives. In addition, we calculated the average length of time between patients’ initial contact with the health care system call center and the return call by the PCP (wait time).Of charts reviewed, the majority (71%) had documentation of appropriate isolation precautions. Although 25% of patients had documentation of a high-risk profession with potential to expose many people, more than half of the patients had no documentation of occupation. Most patients (86%) had no updated documentation regarding goals of care, health care proxy, or advance directives in their urgent care VC visit. The average time between the patient initiating contact with the health care system call center and a return call to the patient from a PCP was 104 minutes (excluding calls received after 3:30

Discussion

This analysis adds to the growing literature on use of VC during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we describe the population of patients who used VRUCs within a large health care system in a RTVC. This analysis was limited by lack of available testing during the initial phase of the pandemic, which contributed to the lower than expected rates of testing and test positivity in patients managed via VRUCs. In addition, chart review data are limited as the data includes only what was documented during the visit and not the entire discussion during the encounter.

Several important outcomes from this analysis can be applied to interventions in the future, which may have large public health implications: Several hundred patients who reported respiratory symptoms were expeditiously evaluated by a PCP using VC. The average wait time to full clinical assessment was about 1.5 hours. This short duration between contact and evaluation permitted early education about isolation precautions, which may have minimized spread. In addition, this innovation kept patients out of the medical center, eliminating chains of transmission to other vulnerable patients and health care workers.

Our retrospective chart review also revealed that more than half the patients were not queried about their occupation, but of those that were asked, a significant number were in high-risk professions potentially exposing large numbers of people. This would be an important aspect to add to future templated notes to minimize work-related exposures. Also, we identified that few HCPs discussed goals of care with patients. Given the nature of COVID-19 and potential for rapid decompensation especially in vulnerable patients, this also would be important to include in the future.

Conclusions

VC urgent care clinics to address possible COVID-19 symptoms facilitated expeditious PCP assessment while keeping potentially contagious patients outside of high-risk health care environments. Streamlining and optimizing clinical VC assessments will be imperative to future management of COVID-19 and potentially to other future infectious pandemics. This includes development of templated notes incorporating counseling regarding appropriate isolation, questions about high-contact occupations, and goals of care discussions.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Robert F. Walsh, MHA.

Virtual care (VC) has emerged as an effective mode of health care delivery especially in settings where significant barriers to traditional in-person visits exist; a large systematic review supports feasibility of telemedicine in primary care and suggests that telemedicine is at least as effective as traditional care.1 Nevertheless, broad adoption of VC into practice has lagged, impeded by government and private insurance reimbursement requirements as well as the persistent belief that care can best be delivered in person.2-4 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, states that enacted parity legislation that required private insurance companies to provide reimbursement coverage for telehealth services saw a significant increase in the number of outpatient telehealth visits (about ≥ 30% odds compared with nonparity states).3

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person medical appointments were converted to VC visits to reduce increased exposure risks to patients and health care workers.5 Prior government and private sector policies were suspended, and payment restrictions lifted, enabling adoption of VC modalities to rapidly accommodate the emergent need and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for virtual care.6-11

The CDC guidelines on managing operations during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need to provide care in the safest way for patients and health care personnel and emphasized the importance of optimizing telehealth services. The federal government facilitated telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic via temporary measures under the COVID-19 public health emergency declaration. This included Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act flexibility to use everyday technology for VC visits, regulatory changes to deliver services to Medicare and Medicaid patients, permission of telehealth services across state lines, and prescribing of controlled substances via telehealth without an in-person medical evaluation.7

In response, health care providers (HCPs) and health care organizations created or expanded on existing telehealth infrastructure, developing virtual urgent care centers and telephone-based programs to evaluate patients remotely via screening questions that triaged them to a correct level of response, with possible subsequent virtual physician evaluation if indicated.12,13

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) also shifted to a VC model in response to COVID-19 guided by a unique perspective from a well-developed prior VC experience.14-16 As a federally funded system, the VHA depends on workload documentation for budgeting. Since 2015, the VHA has provided workload credit and incentivized HCPs (via pay for performance) for the use of VC, including telephone visits, video visits, and secure messaging. These incentives resulted in higher rates of telehealth utilization before the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the private sector (with 4.2% and 0.7% of visits within the VHA being telephone and video visits, respectively, compared with telehealth utilization rates of 1.0% for Medicare recipients and 1.1% in an all-payer database).16

Historically, VHA care has successfully transitioned from in-person care models to exclusively virtual modalities to prevent suspension of medical services during natural disasters. Studies performed during these periods, specifically during the 2017 hurricane season (during which multiple VHA hospitals were closed or had limited in-person service available), supported telehealth as an efficient health care delivery method, and even recommended expanding telehealth services within non-VHA environments to accommodate needs of the general public during crises and postdisaster health care delivery.17