User login

Biometric changes on fitness trackers, smartwatches detect COVID-19

A smartphone app that combines passively collected physiologic data from wearable devices, such as fitness trackers, and self-reported symptoms can discriminate between COVID-19–positive and –negative individuals among those who report symptoms, new data suggest.

After analyzing data from more than 30,000 participants, researchers from the Digital Engagement and Tracking for Early Control and Treatment (DETECT) study concluded that adding individual changes in sensor data improves models based on symptoms alone for differentiating symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 positive and symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 negative.

The combination can potentially identify infection clusters before wider community spread occurs, Giorgio Quer, PhD, and colleagues report in an article published online Oct. 29 in Nature Medicine. DETECT investigators note that marrying participant-reported symptoms with personal sensor data, such as deviation from normal sleep duration and resting heart rate, resulted in an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.80 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.73-0.86) for differentiating between symptomatic individuals who were positive and those who were negative for COVID-19.

“By better characterizing each individual’s unique baseline, you can then identify changes that may indicate that someone has a viral illness,” said Dr. Quer, director of artificial intelligence at Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. “In previous research, we found that the proportion of individuals with elevated resting heart rate and sleep duration compared with their normal could significantly improve real-time detection of influenza-like illness rates at the state level,” he said in an interview.

Thus, continuous passively captured data may be a useful adjunct to bricks-and-mortar site testing, which is generally a one-off or infrequent sampling assay and is not always easily accessible, he added. Furthermore, traditional screening with temperature and symptom reporting is inadequate. An elevation in temperature is not as common as frequently believed for people who test positive for COVID-19, Dr. Quer continued. “Early identification via sensor variables of those who are presymptomatic or even asymptomatic would be especially valuable, as people may potentially be infectious during this period, and early detection is the ultimate goal,” Dr. Quer said.

According to his group, adding these physiologic changes from baseline values significantly outperformed detection (P < .01) using a British model described in an earlier study by by Cristina Menni, PhD, and associates. That method, in which symptoms were considered alone, yielded an AUC of 0.71 (IQR, 0.63-0.79).

According to Dr. Quer, one in five Americans currently wear an electronic device. “If we could enroll even a small percentage of these individuals, we’d be able to potentially identify clusters before they have the opportunity to spread,” he said.

DETECT study details

During the period March 15 to June 7, 2020, the study enrolled 30,529 participants from all 50 states. They ranged in age from younger than 35 years (23.1%) to older than 65 years (12.8%); the majority (63.5%) were aged 35-65 years, and 62% were women. Sensor devices in use by the cohort included Fitbit activity trackers (78.4%) and Apple HealthKit (31.2%).

Participants downloaded an app called MyDataHelps, which collects smartwatch and activity tracker information, including self-reported symptoms and diagnostic testing results. The app also monitors changes from baseline in resting heart rate, sleep duration, and physical activity, as measured by steps.

Overall, 3,811 participants reported having at least one symptom of some kind (e.g., fatigue, cough, dyspnea, loss of taste or smell). Of these, 54 reported testing positive for COVID-19, and 279 reported testing negative.

Sleep and activity were significantly different for the positive and negative groups, with an AUC of 0.68 (IQR, 0.57-0.79) for the sleep metric and 0.69 (IQR, 0.61-0.77) for the activity metric, suggesting that these parameters were more affected in COVID-19–positive participants.

When the investigators combined resting heart rate, sleep, and activity into a single metric, predictive performance improved to an AUC of 0.72 (IQR, 0.64-0.80).

The next step, Dr. Quer said, is to include an alert to notify users of possible infection.

Alerting users to possible COVID-19 infection

In a similar study, an alert feature was already incorporated. The study, led by Michael P. Snyder, PhD, director of the Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, will soon be published online in Nature Biomedical Engineering. In that study, presymptomatic detection of COVID-19 was achieved in more than 80% of participants using resting heart rate.

“The median is 4 days prior to symptom formation,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “We have an alarm system to notify people when their heart rate is elevated. So a positive signal from a smartwatch can be used to follow up by polymerase chain reaction [testing].”

Dr. Snyder said these approaches offer a roadmap to containing widespread infections. “Public health authorities need to be open to these technologies and begin incorporating them into their tracking,” he said. “Right now, people do temperature checks, which are of limited value. Resting heart rate is much better information.”

Although the DETECT researchers have not yet received feedback on their results, they believe public health authorities could recommend the use of such apps. “These are devices that people routinely wear for tracking their fitness and sleep, so it would be relatively easy to use the data for viral illness tracking,” said co–lead author Jennifer Radin, PhD, an epidemiologist at Scripps. “Testing resources are still limited and don’t allow for routine serial testing of individuals who may be asymptomatic or presymptomatic. Wearables can offer a different way to routinely monitor and screen people for changes in their data that may indicate COVID-19.”

The marshaling of data through consumer digital platforms to fight the coronavirus is gaining ground. New York State and New Jersey are already embracing smartphone apps to alert individuals to possible exposure to the virus.

More than 710,000 New Yorkers have downloaded the COVID NY Alert app, launched in October to help protect individuals and communities from COVID-19 by sending alerts without compromising privacy or personal information. “Upon receiving a notification about a potential exposure, users are then able to self-quarantine, get tested, and reduce the potential exposure risk to family, friends, coworkers, and others,” Jonah Bruno, a spokesperson for the New York State Department of Health, said in an interview.

And recently the Mayo Clinic and Safe Health Systems launched a platform to store COVID-19 testing and vaccination data.

Both the Scripps and Stanford platforms are part of a global technologic response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospective studies, led by device manufacturers and academic institutions, allow individuals to voluntarily share sensor and clinical data to address the crisis. Similar approaches have been used to track COVID-19 in large populations in Germany via the Corona Data Donation app.

The study by Dr. Quer and colleagues was funded by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported grants from Janssen and personal fees from Otsuka and Livongo outside of the submitted work. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Snyder has ties to Personalis, Qbio, January, SensOmics, Protos, Mirvie, and Oralome.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A smartphone app that combines passively collected physiologic data from wearable devices, such as fitness trackers, and self-reported symptoms can discriminate between COVID-19–positive and –negative individuals among those who report symptoms, new data suggest.

After analyzing data from more than 30,000 participants, researchers from the Digital Engagement and Tracking for Early Control and Treatment (DETECT) study concluded that adding individual changes in sensor data improves models based on symptoms alone for differentiating symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 positive and symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 negative.

The combination can potentially identify infection clusters before wider community spread occurs, Giorgio Quer, PhD, and colleagues report in an article published online Oct. 29 in Nature Medicine. DETECT investigators note that marrying participant-reported symptoms with personal sensor data, such as deviation from normal sleep duration and resting heart rate, resulted in an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.80 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.73-0.86) for differentiating between symptomatic individuals who were positive and those who were negative for COVID-19.

“By better characterizing each individual’s unique baseline, you can then identify changes that may indicate that someone has a viral illness,” said Dr. Quer, director of artificial intelligence at Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. “In previous research, we found that the proportion of individuals with elevated resting heart rate and sleep duration compared with their normal could significantly improve real-time detection of influenza-like illness rates at the state level,” he said in an interview.

Thus, continuous passively captured data may be a useful adjunct to bricks-and-mortar site testing, which is generally a one-off or infrequent sampling assay and is not always easily accessible, he added. Furthermore, traditional screening with temperature and symptom reporting is inadequate. An elevation in temperature is not as common as frequently believed for people who test positive for COVID-19, Dr. Quer continued. “Early identification via sensor variables of those who are presymptomatic or even asymptomatic would be especially valuable, as people may potentially be infectious during this period, and early detection is the ultimate goal,” Dr. Quer said.

According to his group, adding these physiologic changes from baseline values significantly outperformed detection (P < .01) using a British model described in an earlier study by by Cristina Menni, PhD, and associates. That method, in which symptoms were considered alone, yielded an AUC of 0.71 (IQR, 0.63-0.79).

According to Dr. Quer, one in five Americans currently wear an electronic device. “If we could enroll even a small percentage of these individuals, we’d be able to potentially identify clusters before they have the opportunity to spread,” he said.

DETECT study details

During the period March 15 to June 7, 2020, the study enrolled 30,529 participants from all 50 states. They ranged in age from younger than 35 years (23.1%) to older than 65 years (12.8%); the majority (63.5%) were aged 35-65 years, and 62% were women. Sensor devices in use by the cohort included Fitbit activity trackers (78.4%) and Apple HealthKit (31.2%).

Participants downloaded an app called MyDataHelps, which collects smartwatch and activity tracker information, including self-reported symptoms and diagnostic testing results. The app also monitors changes from baseline in resting heart rate, sleep duration, and physical activity, as measured by steps.

Overall, 3,811 participants reported having at least one symptom of some kind (e.g., fatigue, cough, dyspnea, loss of taste or smell). Of these, 54 reported testing positive for COVID-19, and 279 reported testing negative.

Sleep and activity were significantly different for the positive and negative groups, with an AUC of 0.68 (IQR, 0.57-0.79) for the sleep metric and 0.69 (IQR, 0.61-0.77) for the activity metric, suggesting that these parameters were more affected in COVID-19–positive participants.

When the investigators combined resting heart rate, sleep, and activity into a single metric, predictive performance improved to an AUC of 0.72 (IQR, 0.64-0.80).

The next step, Dr. Quer said, is to include an alert to notify users of possible infection.

Alerting users to possible COVID-19 infection

In a similar study, an alert feature was already incorporated. The study, led by Michael P. Snyder, PhD, director of the Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, will soon be published online in Nature Biomedical Engineering. In that study, presymptomatic detection of COVID-19 was achieved in more than 80% of participants using resting heart rate.

“The median is 4 days prior to symptom formation,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “We have an alarm system to notify people when their heart rate is elevated. So a positive signal from a smartwatch can be used to follow up by polymerase chain reaction [testing].”

Dr. Snyder said these approaches offer a roadmap to containing widespread infections. “Public health authorities need to be open to these technologies and begin incorporating them into their tracking,” he said. “Right now, people do temperature checks, which are of limited value. Resting heart rate is much better information.”

Although the DETECT researchers have not yet received feedback on their results, they believe public health authorities could recommend the use of such apps. “These are devices that people routinely wear for tracking their fitness and sleep, so it would be relatively easy to use the data for viral illness tracking,” said co–lead author Jennifer Radin, PhD, an epidemiologist at Scripps. “Testing resources are still limited and don’t allow for routine serial testing of individuals who may be asymptomatic or presymptomatic. Wearables can offer a different way to routinely monitor and screen people for changes in their data that may indicate COVID-19.”

The marshaling of data through consumer digital platforms to fight the coronavirus is gaining ground. New York State and New Jersey are already embracing smartphone apps to alert individuals to possible exposure to the virus.

More than 710,000 New Yorkers have downloaded the COVID NY Alert app, launched in October to help protect individuals and communities from COVID-19 by sending alerts without compromising privacy or personal information. “Upon receiving a notification about a potential exposure, users are then able to self-quarantine, get tested, and reduce the potential exposure risk to family, friends, coworkers, and others,” Jonah Bruno, a spokesperson for the New York State Department of Health, said in an interview.

And recently the Mayo Clinic and Safe Health Systems launched a platform to store COVID-19 testing and vaccination data.

Both the Scripps and Stanford platforms are part of a global technologic response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospective studies, led by device manufacturers and academic institutions, allow individuals to voluntarily share sensor and clinical data to address the crisis. Similar approaches have been used to track COVID-19 in large populations in Germany via the Corona Data Donation app.

The study by Dr. Quer and colleagues was funded by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported grants from Janssen and personal fees from Otsuka and Livongo outside of the submitted work. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Snyder has ties to Personalis, Qbio, January, SensOmics, Protos, Mirvie, and Oralome.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A smartphone app that combines passively collected physiologic data from wearable devices, such as fitness trackers, and self-reported symptoms can discriminate between COVID-19–positive and –negative individuals among those who report symptoms, new data suggest.

After analyzing data from more than 30,000 participants, researchers from the Digital Engagement and Tracking for Early Control and Treatment (DETECT) study concluded that adding individual changes in sensor data improves models based on symptoms alone for differentiating symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 positive and symptomatic persons who are COVID-19 negative.

The combination can potentially identify infection clusters before wider community spread occurs, Giorgio Quer, PhD, and colleagues report in an article published online Oct. 29 in Nature Medicine. DETECT investigators note that marrying participant-reported symptoms with personal sensor data, such as deviation from normal sleep duration and resting heart rate, resulted in an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.80 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.73-0.86) for differentiating between symptomatic individuals who were positive and those who were negative for COVID-19.

“By better characterizing each individual’s unique baseline, you can then identify changes that may indicate that someone has a viral illness,” said Dr. Quer, director of artificial intelligence at Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, Calif. “In previous research, we found that the proportion of individuals with elevated resting heart rate and sleep duration compared with their normal could significantly improve real-time detection of influenza-like illness rates at the state level,” he said in an interview.

Thus, continuous passively captured data may be a useful adjunct to bricks-and-mortar site testing, which is generally a one-off or infrequent sampling assay and is not always easily accessible, he added. Furthermore, traditional screening with temperature and symptom reporting is inadequate. An elevation in temperature is not as common as frequently believed for people who test positive for COVID-19, Dr. Quer continued. “Early identification via sensor variables of those who are presymptomatic or even asymptomatic would be especially valuable, as people may potentially be infectious during this period, and early detection is the ultimate goal,” Dr. Quer said.

According to his group, adding these physiologic changes from baseline values significantly outperformed detection (P < .01) using a British model described in an earlier study by by Cristina Menni, PhD, and associates. That method, in which symptoms were considered alone, yielded an AUC of 0.71 (IQR, 0.63-0.79).

According to Dr. Quer, one in five Americans currently wear an electronic device. “If we could enroll even a small percentage of these individuals, we’d be able to potentially identify clusters before they have the opportunity to spread,” he said.

DETECT study details

During the period March 15 to June 7, 2020, the study enrolled 30,529 participants from all 50 states. They ranged in age from younger than 35 years (23.1%) to older than 65 years (12.8%); the majority (63.5%) were aged 35-65 years, and 62% were women. Sensor devices in use by the cohort included Fitbit activity trackers (78.4%) and Apple HealthKit (31.2%).

Participants downloaded an app called MyDataHelps, which collects smartwatch and activity tracker information, including self-reported symptoms and diagnostic testing results. The app also monitors changes from baseline in resting heart rate, sleep duration, and physical activity, as measured by steps.

Overall, 3,811 participants reported having at least one symptom of some kind (e.g., fatigue, cough, dyspnea, loss of taste or smell). Of these, 54 reported testing positive for COVID-19, and 279 reported testing negative.

Sleep and activity were significantly different for the positive and negative groups, with an AUC of 0.68 (IQR, 0.57-0.79) for the sleep metric and 0.69 (IQR, 0.61-0.77) for the activity metric, suggesting that these parameters were more affected in COVID-19–positive participants.

When the investigators combined resting heart rate, sleep, and activity into a single metric, predictive performance improved to an AUC of 0.72 (IQR, 0.64-0.80).

The next step, Dr. Quer said, is to include an alert to notify users of possible infection.

Alerting users to possible COVID-19 infection

In a similar study, an alert feature was already incorporated. The study, led by Michael P. Snyder, PhD, director of the Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University, will soon be published online in Nature Biomedical Engineering. In that study, presymptomatic detection of COVID-19 was achieved in more than 80% of participants using resting heart rate.

“The median is 4 days prior to symptom formation,” Dr. Snyder said in an interview. “We have an alarm system to notify people when their heart rate is elevated. So a positive signal from a smartwatch can be used to follow up by polymerase chain reaction [testing].”

Dr. Snyder said these approaches offer a roadmap to containing widespread infections. “Public health authorities need to be open to these technologies and begin incorporating them into their tracking,” he said. “Right now, people do temperature checks, which are of limited value. Resting heart rate is much better information.”

Although the DETECT researchers have not yet received feedback on their results, they believe public health authorities could recommend the use of such apps. “These are devices that people routinely wear for tracking their fitness and sleep, so it would be relatively easy to use the data for viral illness tracking,” said co–lead author Jennifer Radin, PhD, an epidemiologist at Scripps. “Testing resources are still limited and don’t allow for routine serial testing of individuals who may be asymptomatic or presymptomatic. Wearables can offer a different way to routinely monitor and screen people for changes in their data that may indicate COVID-19.”

The marshaling of data through consumer digital platforms to fight the coronavirus is gaining ground. New York State and New Jersey are already embracing smartphone apps to alert individuals to possible exposure to the virus.

More than 710,000 New Yorkers have downloaded the COVID NY Alert app, launched in October to help protect individuals and communities from COVID-19 by sending alerts without compromising privacy or personal information. “Upon receiving a notification about a potential exposure, users are then able to self-quarantine, get tested, and reduce the potential exposure risk to family, friends, coworkers, and others,” Jonah Bruno, a spokesperson for the New York State Department of Health, said in an interview.

And recently the Mayo Clinic and Safe Health Systems launched a platform to store COVID-19 testing and vaccination data.

Both the Scripps and Stanford platforms are part of a global technologic response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospective studies, led by device manufacturers and academic institutions, allow individuals to voluntarily share sensor and clinical data to address the crisis. Similar approaches have been used to track COVID-19 in large populations in Germany via the Corona Data Donation app.

The study by Dr. Quer and colleagues was funded by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported grants from Janssen and personal fees from Otsuka and Livongo outside of the submitted work. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Snyder has ties to Personalis, Qbio, January, SensOmics, Protos, Mirvie, and Oralome.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Black patients less likely to receive H. pylori eradication testing

Black patients may be significantly less likely to receive eradication testing after treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection than patients of other races/ethnic groups, based on a retrospective analysis of more than 1,700 individuals.

This disparity may exacerbate the already increased burden of H. pylori infection and gastric cancer among Black individuals, according to principal author David A. Leiman, MD, MSHP, of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.

“H. pylori infection disproportionately affects racial/ethnic minorities and those of lower socioeconomic status,” Dr. Leiman, coauthor Julius Wilder, MD, PhD, of Duke University in Durham, and colleagues wrote in their abstract presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “ACG guidelines recommend treatment for H. pylori infection followed by confirmation of cure. Adherence to these recommendations varies and its impact on practice patterns is unclear. This study characterizes the management of H. pylori infection and predictors of guideline adherence.”

The investigators analyzed electronic medical records from 1,711 patients diagnosed with H. pylori infection through the Duke University Health System between June 2016 and June 2018, most often (71%) via serum antibody test. Approximately two-thirds of those diagnosed were non-White (66%) and female (63%). Out of 1,711 patients, 622 (36%) underwent eradication testing, of whom 559 (90%) were cured.

Despite publication of the ACG H. pylori guideline midway through the study (February 2017), testing rates dropped significantly from 43.1% in 2016 to 35.9% in 2017, and finally 25.5% in 2018 (P < .0001).

“These findings are consistent with other work that has shown low rates of testing to confirm cure in patients treated for H. pylori,” Dr. Leiman said. “There remains a disappointingly low number of patients who are tested for cure.”

Across the entire study period, patients were significantly more likely to undergo eradication testing if they were treated in the gastroenterology department (52.4%), compared with rates ranging from 33% to 34.6% for internal medicine, family medicine, and other departments (P < .001).

Across all departments, Black patients underwent eradication testing significantly less often than patients of other races/ethnicities, at a rate of 30.5% versus 32.2% for White patients, 35.1% for Asian patients, and 36.7% for patients who were of other backgrounds (P < .001). Compared with White patients, Black patients were 38% less likely to undergo eradication testing (odds ratio, 0.62; 95% confidence interval, 0.48-0.79).

Dr. Leiman noted that these findings contrast with a study by Dr. Shria Kumar and colleagues from earlier this year, which found no racial disparity in eradication testing within a Veterans Health Affairs cohort.

“Black patients are significantly less likely to undergo testing for eradication than [patients of other races/ethnicities],” Dr. Leiman said. “More work is needed to understand the mechanisms driving this disparity.” He suggested a number of possible contributing factors, including provider knowledge gaps, fragmented care, and social determinants of health.

“It is clear that a greater emphasis on characterizing and addressing the social determinants of health, including poverty, education, and location, are needed,” Dr. Leiman said. “Although health systems are not solely responsible for the known and ongoing observations of disparities in care, interventions must be identified and implemented to mitigate these issues.” Such interventions would likely require broad participation, he said, including policy makers, health systems, and individual practitioners.

“We plan to perform a prospective mixed methods study to contextualize which social determinants are associated with a decreased likelihood of receiving appropriate eradication testing by exploring barriers at patient, practitioner, and health-system levels,” Dr. Leiman said. “Ultimately, we aim to leverage these findings to develop an evidence-based intervention to circumnavigate those identified barriers, thereby eliminating the observed disparities in H. pylori care.”

According to Gregory L. Hall, MD, of Northeast Ohio Medical University, Rootstown, and Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and codirector of the Partnership for Urban Health Research, Atlanta, the higher rate of H. pylori infection in Black individuals may stem partly from genetic factors.

“Studies have shown that African Americans with a higher proportion of African ancestry have higher rates of H. pylori, suggesting a genetic component to this increased risk,” he said.

Still, Dr. Hall, who is the author of the book Patient-Centered Clinical Care for African Americans, went on to emphasize appropriate H. pylori management and recognition of racial disparities in medicine.

“The ability to test for, treat, and confirm eradication of H. pylori infections represents a great opportunity to improve quality of life through decreased gastritis, gastric ulcers, and gastric cancer,” he said. “[The present findings] show yet another disparity in our clinical care of African Americans that needs increased awareness among providers to these communities.”

Rotonya Carr, MD, of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and lead author of a recent publication addressing racism and health disparities in gastroenterology, said the findings of the present study add weight to a known equity gap.

“These data are concerning in view of the twofold higher prevalence of H. pylori seropositivity and twofold higher incidence of gastric cancer in Black patients, compared with White patients,” Dr. Carr said. “These and other data support a comprehensive approach to reduce GI disparities that includes targeted education of both GI specialists and referring providers.”

According to Dr. Leiman, individual practitioners may work toward more equitable outcomes through a comprehensive clinical approach, regardless of patient race or ethnicity.

“Clinicians should consider H. pylori therapy an episode of care that spans diagnosis, treatment, and confirmation of cure,” he said. “Closing the loop in that episode by ensuring eradication is vital to conforming with best practices, and to reduce patients’ long-term risks.”The investigators disclosed relationships with Exact Sciences, Guardant Health, and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Hall and Dr. Carr reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Reichstein J et al. ACG 2020. Abstract S1332.

Black patients may be significantly less likely to receive eradication testing after treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection than patients of other races/ethnic groups, based on a retrospective analysis of more than 1,700 individuals.

This disparity may exacerbate the already increased burden of H. pylori infection and gastric cancer among Black individuals, according to principal author David A. Leiman, MD, MSHP, of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.

“H. pylori infection disproportionately affects racial/ethnic minorities and those of lower socioeconomic status,” Dr. Leiman, coauthor Julius Wilder, MD, PhD, of Duke University in Durham, and colleagues wrote in their abstract presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “ACG guidelines recommend treatment for H. pylori infection followed by confirmation of cure. Adherence to these recommendations varies and its impact on practice patterns is unclear. This study characterizes the management of H. pylori infection and predictors of guideline adherence.”

The investigators analyzed electronic medical records from 1,711 patients diagnosed with H. pylori infection through the Duke University Health System between June 2016 and June 2018, most often (71%) via serum antibody test. Approximately two-thirds of those diagnosed were non-White (66%) and female (63%). Out of 1,711 patients, 622 (36%) underwent eradication testing, of whom 559 (90%) were cured.

Despite publication of the ACG H. pylori guideline midway through the study (February 2017), testing rates dropped significantly from 43.1% in 2016 to 35.9% in 2017, and finally 25.5% in 2018 (P < .0001).

“These findings are consistent with other work that has shown low rates of testing to confirm cure in patients treated for H. pylori,” Dr. Leiman said. “There remains a disappointingly low number of patients who are tested for cure.”

Across the entire study period, patients were significantly more likely to undergo eradication testing if they were treated in the gastroenterology department (52.4%), compared with rates ranging from 33% to 34.6% for internal medicine, family medicine, and other departments (P < .001).

Across all departments, Black patients underwent eradication testing significantly less often than patients of other races/ethnicities, at a rate of 30.5% versus 32.2% for White patients, 35.1% for Asian patients, and 36.7% for patients who were of other backgrounds (P < .001). Compared with White patients, Black patients were 38% less likely to undergo eradication testing (odds ratio, 0.62; 95% confidence interval, 0.48-0.79).

Dr. Leiman noted that these findings contrast with a study by Dr. Shria Kumar and colleagues from earlier this year, which found no racial disparity in eradication testing within a Veterans Health Affairs cohort.

“Black patients are significantly less likely to undergo testing for eradication than [patients of other races/ethnicities],” Dr. Leiman said. “More work is needed to understand the mechanisms driving this disparity.” He suggested a number of possible contributing factors, including provider knowledge gaps, fragmented care, and social determinants of health.

“It is clear that a greater emphasis on characterizing and addressing the social determinants of health, including poverty, education, and location, are needed,” Dr. Leiman said. “Although health systems are not solely responsible for the known and ongoing observations of disparities in care, interventions must be identified and implemented to mitigate these issues.” Such interventions would likely require broad participation, he said, including policy makers, health systems, and individual practitioners.

“We plan to perform a prospective mixed methods study to contextualize which social determinants are associated with a decreased likelihood of receiving appropriate eradication testing by exploring barriers at patient, practitioner, and health-system levels,” Dr. Leiman said. “Ultimately, we aim to leverage these findings to develop an evidence-based intervention to circumnavigate those identified barriers, thereby eliminating the observed disparities in H. pylori care.”

According to Gregory L. Hall, MD, of Northeast Ohio Medical University, Rootstown, and Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and codirector of the Partnership for Urban Health Research, Atlanta, the higher rate of H. pylori infection in Black individuals may stem partly from genetic factors.

“Studies have shown that African Americans with a higher proportion of African ancestry have higher rates of H. pylori, suggesting a genetic component to this increased risk,” he said.

Still, Dr. Hall, who is the author of the book Patient-Centered Clinical Care for African Americans, went on to emphasize appropriate H. pylori management and recognition of racial disparities in medicine.

“The ability to test for, treat, and confirm eradication of H. pylori infections represents a great opportunity to improve quality of life through decreased gastritis, gastric ulcers, and gastric cancer,” he said. “[The present findings] show yet another disparity in our clinical care of African Americans that needs increased awareness among providers to these communities.”

Rotonya Carr, MD, of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and lead author of a recent publication addressing racism and health disparities in gastroenterology, said the findings of the present study add weight to a known equity gap.

“These data are concerning in view of the twofold higher prevalence of H. pylori seropositivity and twofold higher incidence of gastric cancer in Black patients, compared with White patients,” Dr. Carr said. “These and other data support a comprehensive approach to reduce GI disparities that includes targeted education of both GI specialists and referring providers.”

According to Dr. Leiman, individual practitioners may work toward more equitable outcomes through a comprehensive clinical approach, regardless of patient race or ethnicity.

“Clinicians should consider H. pylori therapy an episode of care that spans diagnosis, treatment, and confirmation of cure,” he said. “Closing the loop in that episode by ensuring eradication is vital to conforming with best practices, and to reduce patients’ long-term risks.”The investigators disclosed relationships with Exact Sciences, Guardant Health, and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Hall and Dr. Carr reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Reichstein J et al. ACG 2020. Abstract S1332.

Black patients may be significantly less likely to receive eradication testing after treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection than patients of other races/ethnic groups, based on a retrospective analysis of more than 1,700 individuals.

This disparity may exacerbate the already increased burden of H. pylori infection and gastric cancer among Black individuals, according to principal author David A. Leiman, MD, MSHP, of Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C.

“H. pylori infection disproportionately affects racial/ethnic minorities and those of lower socioeconomic status,” Dr. Leiman, coauthor Julius Wilder, MD, PhD, of Duke University in Durham, and colleagues wrote in their abstract presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “ACG guidelines recommend treatment for H. pylori infection followed by confirmation of cure. Adherence to these recommendations varies and its impact on practice patterns is unclear. This study characterizes the management of H. pylori infection and predictors of guideline adherence.”

The investigators analyzed electronic medical records from 1,711 patients diagnosed with H. pylori infection through the Duke University Health System between June 2016 and June 2018, most often (71%) via serum antibody test. Approximately two-thirds of those diagnosed were non-White (66%) and female (63%). Out of 1,711 patients, 622 (36%) underwent eradication testing, of whom 559 (90%) were cured.

Despite publication of the ACG H. pylori guideline midway through the study (February 2017), testing rates dropped significantly from 43.1% in 2016 to 35.9% in 2017, and finally 25.5% in 2018 (P < .0001).

“These findings are consistent with other work that has shown low rates of testing to confirm cure in patients treated for H. pylori,” Dr. Leiman said. “There remains a disappointingly low number of patients who are tested for cure.”

Across the entire study period, patients were significantly more likely to undergo eradication testing if they were treated in the gastroenterology department (52.4%), compared with rates ranging from 33% to 34.6% for internal medicine, family medicine, and other departments (P < .001).

Across all departments, Black patients underwent eradication testing significantly less often than patients of other races/ethnicities, at a rate of 30.5% versus 32.2% for White patients, 35.1% for Asian patients, and 36.7% for patients who were of other backgrounds (P < .001). Compared with White patients, Black patients were 38% less likely to undergo eradication testing (odds ratio, 0.62; 95% confidence interval, 0.48-0.79).

Dr. Leiman noted that these findings contrast with a study by Dr. Shria Kumar and colleagues from earlier this year, which found no racial disparity in eradication testing within a Veterans Health Affairs cohort.

“Black patients are significantly less likely to undergo testing for eradication than [patients of other races/ethnicities],” Dr. Leiman said. “More work is needed to understand the mechanisms driving this disparity.” He suggested a number of possible contributing factors, including provider knowledge gaps, fragmented care, and social determinants of health.

“It is clear that a greater emphasis on characterizing and addressing the social determinants of health, including poverty, education, and location, are needed,” Dr. Leiman said. “Although health systems are not solely responsible for the known and ongoing observations of disparities in care, interventions must be identified and implemented to mitigate these issues.” Such interventions would likely require broad participation, he said, including policy makers, health systems, and individual practitioners.

“We plan to perform a prospective mixed methods study to contextualize which social determinants are associated with a decreased likelihood of receiving appropriate eradication testing by exploring barriers at patient, practitioner, and health-system levels,” Dr. Leiman said. “Ultimately, we aim to leverage these findings to develop an evidence-based intervention to circumnavigate those identified barriers, thereby eliminating the observed disparities in H. pylori care.”

According to Gregory L. Hall, MD, of Northeast Ohio Medical University, Rootstown, and Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and codirector of the Partnership for Urban Health Research, Atlanta, the higher rate of H. pylori infection in Black individuals may stem partly from genetic factors.

“Studies have shown that African Americans with a higher proportion of African ancestry have higher rates of H. pylori, suggesting a genetic component to this increased risk,” he said.

Still, Dr. Hall, who is the author of the book Patient-Centered Clinical Care for African Americans, went on to emphasize appropriate H. pylori management and recognition of racial disparities in medicine.

“The ability to test for, treat, and confirm eradication of H. pylori infections represents a great opportunity to improve quality of life through decreased gastritis, gastric ulcers, and gastric cancer,” he said. “[The present findings] show yet another disparity in our clinical care of African Americans that needs increased awareness among providers to these communities.”

Rotonya Carr, MD, of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and lead author of a recent publication addressing racism and health disparities in gastroenterology, said the findings of the present study add weight to a known equity gap.

“These data are concerning in view of the twofold higher prevalence of H. pylori seropositivity and twofold higher incidence of gastric cancer in Black patients, compared with White patients,” Dr. Carr said. “These and other data support a comprehensive approach to reduce GI disparities that includes targeted education of both GI specialists and referring providers.”

According to Dr. Leiman, individual practitioners may work toward more equitable outcomes through a comprehensive clinical approach, regardless of patient race or ethnicity.

“Clinicians should consider H. pylori therapy an episode of care that spans diagnosis, treatment, and confirmation of cure,” he said. “Closing the loop in that episode by ensuring eradication is vital to conforming with best practices, and to reduce patients’ long-term risks.”The investigators disclosed relationships with Exact Sciences, Guardant Health, and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Hall and Dr. Carr reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Reichstein J et al. ACG 2020. Abstract S1332.

FROM ACG 2020

Dermatologists as Social Media Contributors During the COVID-19 Pandemic

On December 31, 2019, cases of a severe pneumonia in patients in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, were reported to the World Health Organization.1,2 The novel coronavirus—severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2—was identified, and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) became a public health emergency of international concern.1 In March 2020, the World Health Organization officially characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic.3 As of October 2020, more than 42.3 million cases and 1.1 million deaths from COVID-19 have been confirmed worldwide.4

As more understanding of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 develops, various cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 are being uncovered.5 The most common cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 reported in the literature are maculopapular or morbilliform exanthem (36.1% of cutaneous manifestations), papulovesicular rash (34.7%), painful acral red purple papules (15.3%), urticaria (9.7%), livedo reticularis lesions (2.8%), and petechiae (1.4%).5

Interestingly, a series of unique cases was identified in April 2020 by a group of dermatologists in Spain. Most patients were children (median age, 13 years) or young adults (median age, 31 years; average age, 36 years; adult age range, 18–91 years).1 Reporting on a representative sample of 6 patients in that series, the group noted that lesions, initially reddish, papular, and resembling chilblains (pernio), progressively became purpuric and flattened in the course of 1 week. Although the lesions presented with some referred discomfort or pain with palpation, they were not highly symptomatic, and no signs of ischemia or Raynaud syndrome were identified. Over time, lesions self-resolved without intervention. Most patients also did not present with what are considered classic COVID-19 signs or symptoms. Only the oldest patient (aged 91 years) presented with a notable respiratory condition; the remaining patients generally were in good health.1 Dermatologists in Italy, France, and the United States also have witnessed these COVID-19–associated cutaneous manifestations.

Scientific understanding of COVID-19 and its associated dermatologic symptoms is evolving. Attention has turned to social media to inform and provide possible health solutions during this unprecedented medical crisis.6 Strict physical distancing measures have made patients and providers alike reliant on global digital social networks, such as Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, to facilitate information sharing about COVID-19.7 The abundance of nonexpert advice and misinformation on social media makes communication of unbiased expert information difficult.8,9 Furthermore, there is a need for dermatologists to provide medical information to patients regarding COVID-19, such as dermatologic manifestations, and clear guidance on immunobiologic or systemic medications during this unprecedented time.9

In recent years, dermatologists have established a growing presence on social media, with many recognized as social media influencers with the ability to affect patients’ health-related behavior.10 Social media frequently has been used by patients to solicit advice regarding skin concerns.9,10 Many individuals, in fact, never see a physician after consulting social media for medical concerns or professional advice.9

In addition, as of March 2020, more than 61% of health care workers were found to use social media as a source of COVID-19–related information.11 Therefore, dermatologists should utilize social media as a platform to share evidence-based information with the public and other health care workers.

Through social media, dermatologists can post high-quality images with clear descriptions to fully characterize skin manifestations in patients with COVID-19. The process of capturing and posting images to the virtual world using a smartphone allows practitioners to gain advice from peers and consultants, share findings with colleagues, and inform the public.12 Social media posts of many deidentified clinical images of rashes in COVID-19–infected patients already have enabled rapid recognition of skin signs by dermatologists.13

Social media sites also are resources where organizations can post updated, evidence-based findings from academic journals. For example, the American Academy of Dermatology and its official journal, the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, had more than 22,000 and 27,000 Instagram followers, respectively, as of a March 2020 analysis.14 Recent online forums and social media posts contain accessible, graphical, patient-friendly images and information on evidence-based treatments for skin disease during the COVID-19 pandemic.13

We should consider initiatives that empower dermatologists to use social media to post unbiased, evidence-based information regarding manifestations of COVID-19 and guidelines for treatment of skin disease during this medical crisis. We hope that dermatologists will help lead the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic and contribute to the evolving knowledge base by characterizing COVID-19–related rashes, understanding their implications, and determining the best evidence for treatment.

- Landa N, Mendieta-Eckert M, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Chilblain-like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:739-743.

- Phelan AL, Katz R, Gostin LO. The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: challenges for global health governance. JAMA. 2020;323:709-710.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation Report – 133. WHO Website. June 1, 2020. www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200601-covid-19-sitrep-133.pdf?sfvrsn=9a56f2ac_4. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at John Hopkins University. John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center website. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed October 24, 2020.

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatolog Sci. 2020;98:75-81.

- Kapoor A, Guha S, Kanti Das M, et al. Digital healthcare: the only solution for better healthcare during COVID-19 pandemic? Indian Heart J. 2020;72:61-64.

- Limaye RJ, Sauer M, Ali J, et al. Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:E277-E278.

- Chawla S. COVID-19: challenges and opportunities for dermatology response. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:326-326.

- Schoenberg E, Shalabi D, Wang JV, et al. Public social media consultations for dermatologic conditions: an online survey. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:6.

- DeBord LC, Patel V, Braun TL, et al. Social media in dermatology: clinical relevance, academic value, and trends across platforms. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:511-518.

- Bhagavathula AS, Aldhaleei WA, Rahmani J, et al. Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among health care workers: cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:E19160.

- Ashique KT, Kaliyadan F, Aurangabadkar SJ. Clinical photography in dermatology using smartphones: an overview. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:158-163.

- Madigan LM, Micheletti RG, Shinkai K. How dermatologists can learn and contribute at the leading edge of the COVID-19 global pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:733-734.

- Guzman AK, Barbieri JS. Response to: “Dermatologists in social media: a study on top influencers, posts, and user engagement” [published online April 20, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.118.

On December 31, 2019, cases of a severe pneumonia in patients in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, were reported to the World Health Organization.1,2 The novel coronavirus—severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2—was identified, and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) became a public health emergency of international concern.1 In March 2020, the World Health Organization officially characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic.3 As of October 2020, more than 42.3 million cases and 1.1 million deaths from COVID-19 have been confirmed worldwide.4

As more understanding of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 develops, various cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 are being uncovered.5 The most common cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 reported in the literature are maculopapular or morbilliform exanthem (36.1% of cutaneous manifestations), papulovesicular rash (34.7%), painful acral red purple papules (15.3%), urticaria (9.7%), livedo reticularis lesions (2.8%), and petechiae (1.4%).5

Interestingly, a series of unique cases was identified in April 2020 by a group of dermatologists in Spain. Most patients were children (median age, 13 years) or young adults (median age, 31 years; average age, 36 years; adult age range, 18–91 years).1 Reporting on a representative sample of 6 patients in that series, the group noted that lesions, initially reddish, papular, and resembling chilblains (pernio), progressively became purpuric and flattened in the course of 1 week. Although the lesions presented with some referred discomfort or pain with palpation, they were not highly symptomatic, and no signs of ischemia or Raynaud syndrome were identified. Over time, lesions self-resolved without intervention. Most patients also did not present with what are considered classic COVID-19 signs or symptoms. Only the oldest patient (aged 91 years) presented with a notable respiratory condition; the remaining patients generally were in good health.1 Dermatologists in Italy, France, and the United States also have witnessed these COVID-19–associated cutaneous manifestations.

Scientific understanding of COVID-19 and its associated dermatologic symptoms is evolving. Attention has turned to social media to inform and provide possible health solutions during this unprecedented medical crisis.6 Strict physical distancing measures have made patients and providers alike reliant on global digital social networks, such as Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, to facilitate information sharing about COVID-19.7 The abundance of nonexpert advice and misinformation on social media makes communication of unbiased expert information difficult.8,9 Furthermore, there is a need for dermatologists to provide medical information to patients regarding COVID-19, such as dermatologic manifestations, and clear guidance on immunobiologic or systemic medications during this unprecedented time.9

In recent years, dermatologists have established a growing presence on social media, with many recognized as social media influencers with the ability to affect patients’ health-related behavior.10 Social media frequently has been used by patients to solicit advice regarding skin concerns.9,10 Many individuals, in fact, never see a physician after consulting social media for medical concerns or professional advice.9

In addition, as of March 2020, more than 61% of health care workers were found to use social media as a source of COVID-19–related information.11 Therefore, dermatologists should utilize social media as a platform to share evidence-based information with the public and other health care workers.

Through social media, dermatologists can post high-quality images with clear descriptions to fully characterize skin manifestations in patients with COVID-19. The process of capturing and posting images to the virtual world using a smartphone allows practitioners to gain advice from peers and consultants, share findings with colleagues, and inform the public.12 Social media posts of many deidentified clinical images of rashes in COVID-19–infected patients already have enabled rapid recognition of skin signs by dermatologists.13

Social media sites also are resources where organizations can post updated, evidence-based findings from academic journals. For example, the American Academy of Dermatology and its official journal, the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, had more than 22,000 and 27,000 Instagram followers, respectively, as of a March 2020 analysis.14 Recent online forums and social media posts contain accessible, graphical, patient-friendly images and information on evidence-based treatments for skin disease during the COVID-19 pandemic.13

We should consider initiatives that empower dermatologists to use social media to post unbiased, evidence-based information regarding manifestations of COVID-19 and guidelines for treatment of skin disease during this medical crisis. We hope that dermatologists will help lead the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic and contribute to the evolving knowledge base by characterizing COVID-19–related rashes, understanding their implications, and determining the best evidence for treatment.

On December 31, 2019, cases of a severe pneumonia in patients in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, were reported to the World Health Organization.1,2 The novel coronavirus—severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2—was identified, and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) became a public health emergency of international concern.1 In March 2020, the World Health Organization officially characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic.3 As of October 2020, more than 42.3 million cases and 1.1 million deaths from COVID-19 have been confirmed worldwide.4

As more understanding of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 develops, various cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 are being uncovered.5 The most common cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 reported in the literature are maculopapular or morbilliform exanthem (36.1% of cutaneous manifestations), papulovesicular rash (34.7%), painful acral red purple papules (15.3%), urticaria (9.7%), livedo reticularis lesions (2.8%), and petechiae (1.4%).5

Interestingly, a series of unique cases was identified in April 2020 by a group of dermatologists in Spain. Most patients were children (median age, 13 years) or young adults (median age, 31 years; average age, 36 years; adult age range, 18–91 years).1 Reporting on a representative sample of 6 patients in that series, the group noted that lesions, initially reddish, papular, and resembling chilblains (pernio), progressively became purpuric and flattened in the course of 1 week. Although the lesions presented with some referred discomfort or pain with palpation, they were not highly symptomatic, and no signs of ischemia or Raynaud syndrome were identified. Over time, lesions self-resolved without intervention. Most patients also did not present with what are considered classic COVID-19 signs or symptoms. Only the oldest patient (aged 91 years) presented with a notable respiratory condition; the remaining patients generally were in good health.1 Dermatologists in Italy, France, and the United States also have witnessed these COVID-19–associated cutaneous manifestations.

Scientific understanding of COVID-19 and its associated dermatologic symptoms is evolving. Attention has turned to social media to inform and provide possible health solutions during this unprecedented medical crisis.6 Strict physical distancing measures have made patients and providers alike reliant on global digital social networks, such as Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, to facilitate information sharing about COVID-19.7 The abundance of nonexpert advice and misinformation on social media makes communication of unbiased expert information difficult.8,9 Furthermore, there is a need for dermatologists to provide medical information to patients regarding COVID-19, such as dermatologic manifestations, and clear guidance on immunobiologic or systemic medications during this unprecedented time.9

In recent years, dermatologists have established a growing presence on social media, with many recognized as social media influencers with the ability to affect patients’ health-related behavior.10 Social media frequently has been used by patients to solicit advice regarding skin concerns.9,10 Many individuals, in fact, never see a physician after consulting social media for medical concerns or professional advice.9

In addition, as of March 2020, more than 61% of health care workers were found to use social media as a source of COVID-19–related information.11 Therefore, dermatologists should utilize social media as a platform to share evidence-based information with the public and other health care workers.

Through social media, dermatologists can post high-quality images with clear descriptions to fully characterize skin manifestations in patients with COVID-19. The process of capturing and posting images to the virtual world using a smartphone allows practitioners to gain advice from peers and consultants, share findings with colleagues, and inform the public.12 Social media posts of many deidentified clinical images of rashes in COVID-19–infected patients already have enabled rapid recognition of skin signs by dermatologists.13

Social media sites also are resources where organizations can post updated, evidence-based findings from academic journals. For example, the American Academy of Dermatology and its official journal, the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, had more than 22,000 and 27,000 Instagram followers, respectively, as of a March 2020 analysis.14 Recent online forums and social media posts contain accessible, graphical, patient-friendly images and information on evidence-based treatments for skin disease during the COVID-19 pandemic.13

We should consider initiatives that empower dermatologists to use social media to post unbiased, evidence-based information regarding manifestations of COVID-19 and guidelines for treatment of skin disease during this medical crisis. We hope that dermatologists will help lead the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic and contribute to the evolving knowledge base by characterizing COVID-19–related rashes, understanding their implications, and determining the best evidence for treatment.

- Landa N, Mendieta-Eckert M, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Chilblain-like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:739-743.

- Phelan AL, Katz R, Gostin LO. The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: challenges for global health governance. JAMA. 2020;323:709-710.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation Report – 133. WHO Website. June 1, 2020. www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200601-covid-19-sitrep-133.pdf?sfvrsn=9a56f2ac_4. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at John Hopkins University. John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center website. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed October 24, 2020.

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatolog Sci. 2020;98:75-81.

- Kapoor A, Guha S, Kanti Das M, et al. Digital healthcare: the only solution for better healthcare during COVID-19 pandemic? Indian Heart J. 2020;72:61-64.

- Limaye RJ, Sauer M, Ali J, et al. Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:E277-E278.

- Chawla S. COVID-19: challenges and opportunities for dermatology response. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:326-326.

- Schoenberg E, Shalabi D, Wang JV, et al. Public social media consultations for dermatologic conditions: an online survey. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:6.

- DeBord LC, Patel V, Braun TL, et al. Social media in dermatology: clinical relevance, academic value, and trends across platforms. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:511-518.

- Bhagavathula AS, Aldhaleei WA, Rahmani J, et al. Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among health care workers: cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:E19160.

- Ashique KT, Kaliyadan F, Aurangabadkar SJ. Clinical photography in dermatology using smartphones: an overview. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:158-163.

- Madigan LM, Micheletti RG, Shinkai K. How dermatologists can learn and contribute at the leading edge of the COVID-19 global pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:733-734.

- Guzman AK, Barbieri JS. Response to: “Dermatologists in social media: a study on top influencers, posts, and user engagement” [published online April 20, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.118.

- Landa N, Mendieta-Eckert M, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Chilblain-like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:739-743.

- Phelan AL, Katz R, Gostin LO. The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: challenges for global health governance. JAMA. 2020;323:709-710.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation Report – 133. WHO Website. June 1, 2020. www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200601-covid-19-sitrep-133.pdf?sfvrsn=9a56f2ac_4. Accessed October 14, 2020.

- COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at John Hopkins University. John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center website. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed October 24, 2020.

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatolog Sci. 2020;98:75-81.

- Kapoor A, Guha S, Kanti Das M, et al. Digital healthcare: the only solution for better healthcare during COVID-19 pandemic? Indian Heart J. 2020;72:61-64.

- Limaye RJ, Sauer M, Ali J, et al. Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2:E277-E278.

- Chawla S. COVID-19: challenges and opportunities for dermatology response. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:326-326.

- Schoenberg E, Shalabi D, Wang JV, et al. Public social media consultations for dermatologic conditions: an online survey. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:6.

- DeBord LC, Patel V, Braun TL, et al. Social media in dermatology: clinical relevance, academic value, and trends across platforms. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:511-518.

- Bhagavathula AS, Aldhaleei WA, Rahmani J, et al. Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among health care workers: cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:E19160.

- Ashique KT, Kaliyadan F, Aurangabadkar SJ. Clinical photography in dermatology using smartphones: an overview. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:158-163.

- Madigan LM, Micheletti RG, Shinkai K. How dermatologists can learn and contribute at the leading edge of the COVID-19 global pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:733-734.

- Guzman AK, Barbieri JS. Response to: “Dermatologists in social media: a study on top influencers, posts, and user engagement” [published online April 20, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.118.

Practice Points

- With the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, strict physical distancing measures have made patients and providers alike reliant on global digital social networks such as Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook to facilitate information sharing about COVID-19.

- Dermatologists should utilize social media as a platform to post unbiased, evidence-based information regarding manifestations of COVID-19 and guidelines for treatment of skin disease during the global pandemic.

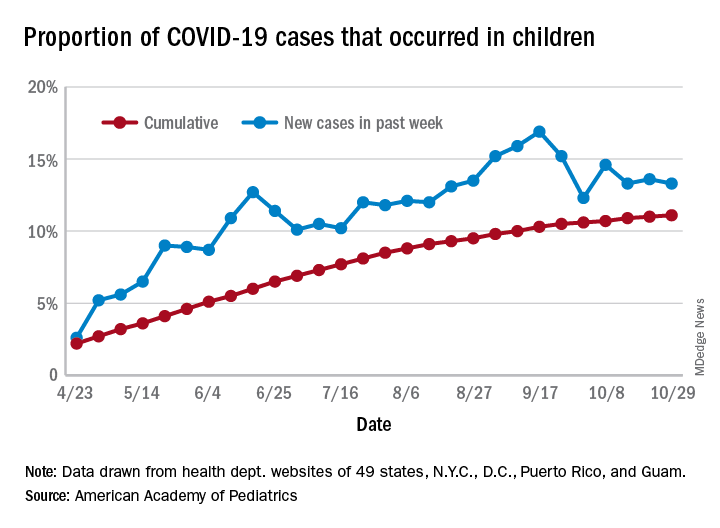

COVID-19: U.S. sets new weekly high in children

the American Academy of Pediatrics announced Nov. 2.

For the week, over 61,000 cases were reported in children, bringing the number of COVID-19 cases for the month of October to nearly 200,000 and the total since the start of the pandemic to over 853,000, the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly report.

“These numbers reflect a disturbing increase in cases throughout most of the United States in all populations, especially among young adults,” Yvonne Maldonado, MD, chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, said in a separate statement. “We are entering a heightened wave of infections around the country. We would encourage family holiday gatherings to be avoided if possible, especially if there are high-risk individuals in the household.”

For the week ending Oct. 29, children represented 13.3% of all cases, possibly constituting a minitrend of stability over the past 3 weeks. For the full length of the pandemic, 11.1% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, although severe illness is much less common: 1.7% of all hospitalizations (data from 24 states and New York City) and 0.06% of all deaths (data from 42 states and New York City), the AAP and CHA report said.

Other data show that 1,134 per 100,000 children in the United States have been infected by the coronavirus, up from 1,053 the previous week, with state rates ranging from 221 per 100,000 in Vermont to 3,321 in North Dakota. In Wyoming, 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, the highest of any state, while New Jersey has the lowest rate at 4.9%, the AAP/CHA report showed.

In the 10 states making testing data available, children represent the lowest percentage of tests in Iowa (5.0%) and the highest in Indiana (16.9%). Iowa, however, has the highest positivity rate for children at 14.6%, along with Nevada, while West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%, the AAP and CHA said in the report.

These numbers, however, may not be telling the whole story. “The number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is likely an undercount because children’s symptoms are often mild and they may not be tested for every illness,” the AAP said in its statement.

“We urge policy makers to listen to doctors and public health experts rather than level baseless accusations against them. Physicians, nurses and other health care professionals have put their lives on the line to protect our communities. We can all do our part to protect them, and our communities, by wearing masks, practicing physical distancing, and getting our flu immunizations,” AAP President Sally Goza, MD, said in the AAP statement.

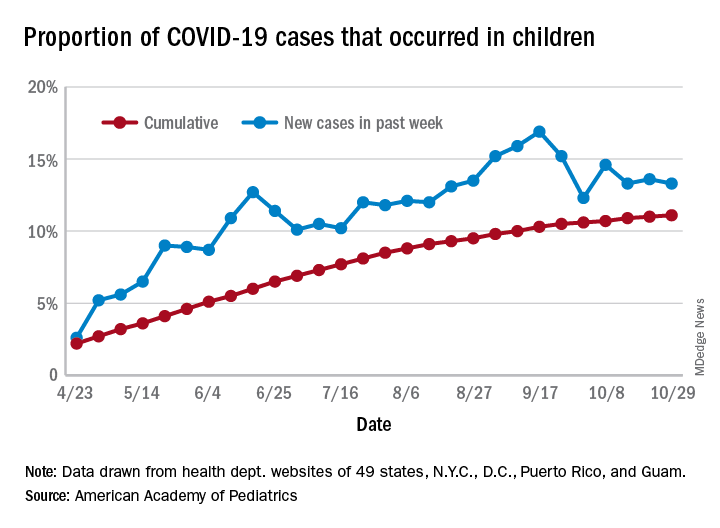

the American Academy of Pediatrics announced Nov. 2.

For the week, over 61,000 cases were reported in children, bringing the number of COVID-19 cases for the month of October to nearly 200,000 and the total since the start of the pandemic to over 853,000, the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly report.

“These numbers reflect a disturbing increase in cases throughout most of the United States in all populations, especially among young adults,” Yvonne Maldonado, MD, chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, said in a separate statement. “We are entering a heightened wave of infections around the country. We would encourage family holiday gatherings to be avoided if possible, especially if there are high-risk individuals in the household.”

For the week ending Oct. 29, children represented 13.3% of all cases, possibly constituting a minitrend of stability over the past 3 weeks. For the full length of the pandemic, 11.1% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, although severe illness is much less common: 1.7% of all hospitalizations (data from 24 states and New York City) and 0.06% of all deaths (data from 42 states and New York City), the AAP and CHA report said.

Other data show that 1,134 per 100,000 children in the United States have been infected by the coronavirus, up from 1,053 the previous week, with state rates ranging from 221 per 100,000 in Vermont to 3,321 in North Dakota. In Wyoming, 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, the highest of any state, while New Jersey has the lowest rate at 4.9%, the AAP/CHA report showed.

In the 10 states making testing data available, children represent the lowest percentage of tests in Iowa (5.0%) and the highest in Indiana (16.9%). Iowa, however, has the highest positivity rate for children at 14.6%, along with Nevada, while West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%, the AAP and CHA said in the report.

These numbers, however, may not be telling the whole story. “The number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is likely an undercount because children’s symptoms are often mild and they may not be tested for every illness,” the AAP said in its statement.

“We urge policy makers to listen to doctors and public health experts rather than level baseless accusations against them. Physicians, nurses and other health care professionals have put their lives on the line to protect our communities. We can all do our part to protect them, and our communities, by wearing masks, practicing physical distancing, and getting our flu immunizations,” AAP President Sally Goza, MD, said in the AAP statement.

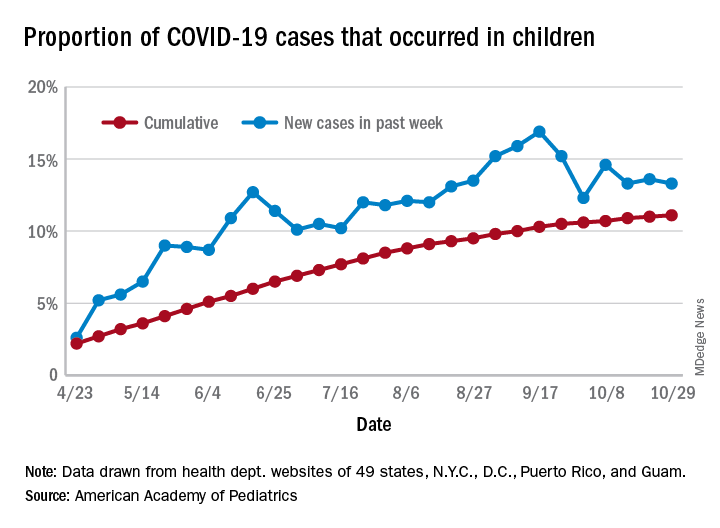

the American Academy of Pediatrics announced Nov. 2.

For the week, over 61,000 cases were reported in children, bringing the number of COVID-19 cases for the month of October to nearly 200,000 and the total since the start of the pandemic to over 853,000, the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly report.

“These numbers reflect a disturbing increase in cases throughout most of the United States in all populations, especially among young adults,” Yvonne Maldonado, MD, chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, said in a separate statement. “We are entering a heightened wave of infections around the country. We would encourage family holiday gatherings to be avoided if possible, especially if there are high-risk individuals in the household.”

For the week ending Oct. 29, children represented 13.3% of all cases, possibly constituting a minitrend of stability over the past 3 weeks. For the full length of the pandemic, 11.1% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, although severe illness is much less common: 1.7% of all hospitalizations (data from 24 states and New York City) and 0.06% of all deaths (data from 42 states and New York City), the AAP and CHA report said.

Other data show that 1,134 per 100,000 children in the United States have been infected by the coronavirus, up from 1,053 the previous week, with state rates ranging from 221 per 100,000 in Vermont to 3,321 in North Dakota. In Wyoming, 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, the highest of any state, while New Jersey has the lowest rate at 4.9%, the AAP/CHA report showed.

In the 10 states making testing data available, children represent the lowest percentage of tests in Iowa (5.0%) and the highest in Indiana (16.9%). Iowa, however, has the highest positivity rate for children at 14.6%, along with Nevada, while West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%, the AAP and CHA said in the report.

These numbers, however, may not be telling the whole story. “The number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is likely an undercount because children’s symptoms are often mild and they may not be tested for every illness,” the AAP said in its statement.

“We urge policy makers to listen to doctors and public health experts rather than level baseless accusations against them. Physicians, nurses and other health care professionals have put their lives on the line to protect our communities. We can all do our part to protect them, and our communities, by wearing masks, practicing physical distancing, and getting our flu immunizations,” AAP President Sally Goza, MD, said in the AAP statement.

OTC topical ivermectin lotion earns FDA approval for head lice

in patients aged 6 months and older.

Ivermectin was approved as a prescription treatment for head lice in February 2012, according to an FDA press release, and is now approved as an over-the-counter treatment through an “Rx-to-OTC” switch process. The approval was granted to Arbor Pharmaceuticals.

The expanded approval for ivermectin increases access to effective care for head lice, which is estimated to affect between 6 million and 12 million children each year in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The Rx-to-OTC switch process aims to promote public health by increasing consumer access to drugs that would otherwise only be available by prescription,” Theresa Michele, MD, acting director of the Office of Nonprescription Drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

The FDA also noted in the press release that “Sklice, and its active ingredient ivermectin, have not been shown to be safe or effective for the treatment or prevention of COVID-19 and they are not FDA-approved for this use.”

The drug is approved only for treating head lice, and should be used on the scalp and dry hair, according to the labeling. In the wake of the approval, ivermectin will no longer be available as a prescription drug, according to the FDA, and patients currently using prescription versions should contact their health care providers.

An Rx-to-OTC switch is contingent on the manufacturer’s data showing that the drug is safe and effective when used as directed. In addition, “the manufacturer must show that consumers can understand how to use the drug safely and effectively without the supervision of a health care professional,” according to the FDA.

in patients aged 6 months and older.

Ivermectin was approved as a prescription treatment for head lice in February 2012, according to an FDA press release, and is now approved as an over-the-counter treatment through an “Rx-to-OTC” switch process. The approval was granted to Arbor Pharmaceuticals.

The expanded approval for ivermectin increases access to effective care for head lice, which is estimated to affect between 6 million and 12 million children each year in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The Rx-to-OTC switch process aims to promote public health by increasing consumer access to drugs that would otherwise only be available by prescription,” Theresa Michele, MD, acting director of the Office of Nonprescription Drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the press release.

The FDA also noted in the press release that “Sklice, and its active ingredient ivermectin, have not been shown to be safe or effective for the treatment or prevention of COVID-19 and they are not FDA-approved for this use.”

The drug is approved only for treating head lice, and should be used on the scalp and dry hair, according to the labeling. In the wake of the approval, ivermectin will no longer be available as a prescription drug, according to the FDA, and patients currently using prescription versions should contact their health care providers.

An Rx-to-OTC switch is contingent on the manufacturer’s data showing that the drug is safe and effective when used as directed. In addition, “the manufacturer must show that consumers can understand how to use the drug safely and effectively without the supervision of a health care professional,” according to the FDA.

in patients aged 6 months and older.

Ivermectin was approved as a prescription treatment for head lice in February 2012, according to an FDA press release, and is now approved as an over-the-counter treatment through an “Rx-to-OTC” switch process. The approval was granted to Arbor Pharmaceuticals.