User login

Biologic mesh safe, effective for prevention of parastomal hernia recurrence

at 18.9%.

Theadore Hufford, MD, of the University of Illinois at Chicago and his colleagues conducted a study to look at the effects of placement and type of mesh on postop morbidity and recurrence of parastomal hernia (PSH). The study was a retrospective analysis of 58 patients who had undergone local PSH repair with biological mesh between July 2006 and July 2015 at a single medical center.

All procedures were conducted by three board-certified surgeons at a tertiary medical center, and decisions such as the mesh type, placement and incision type were determined by the attending surgeon’s operative preferences.

In the study group, mesh placement (overlay, underlay, or sandwich technique) was found to have a statistically significant effect on recurrence. Of the patients who received an underlay of biologic mesh, 33% had a recurrence, compared with 25% of those who had overlays. The sandwich technique (a combination of overlay and underlay) was found to have the lowest rate of recurrence at 6.7%. The type of mesh (human origin, bovine, or porcine) and type of stoma (colostomy vs. ileostomy) had no statistically significant effect on the rate of recurrence.

Total recurrences in the study patients was 18.9%, a figure consistent with the current literature on parastomal hernia repair, the investigators wrote.

A key factor in recurrence was type of incision. Keyhole incisions had a much lower rate of recurrence than did circular incisions (32% vs. 9.1%; P = .042).

In the study group, “one patient was readmitted for mesh infection within 30 days of the repair and required mesh removal. Even with the biologic mesh in place there was an overlying skin infection that warranted reoperation that resulted in the stoma being moved to a new site altogether,” the investigators wrote.

The limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of the research and the difficulty in diagnosing PSH, which is often asymptomatic, the investigators mentioned. In addition, the techniques for local PSH repair with biologic mesh are not fully standardized. Mesh type and location decisions are often made on a case-by-case basis which limits the applicability of the study data for general PSH repairs.

Dr. Hufford and his associates wrote, “Our results suggest local parastomal hernia repair with biological mesh is both a safe and effective method, especially when used with the sandwich technique for mesh placement, for definitive treatment of parastomal hernias with very low morbidity, and acceptable recurrence rate.”

The investigators reported no disclosures.

at 18.9%.

Theadore Hufford, MD, of the University of Illinois at Chicago and his colleagues conducted a study to look at the effects of placement and type of mesh on postop morbidity and recurrence of parastomal hernia (PSH). The study was a retrospective analysis of 58 patients who had undergone local PSH repair with biological mesh between July 2006 and July 2015 at a single medical center.

All procedures were conducted by three board-certified surgeons at a tertiary medical center, and decisions such as the mesh type, placement and incision type were determined by the attending surgeon’s operative preferences.

In the study group, mesh placement (overlay, underlay, or sandwich technique) was found to have a statistically significant effect on recurrence. Of the patients who received an underlay of biologic mesh, 33% had a recurrence, compared with 25% of those who had overlays. The sandwich technique (a combination of overlay and underlay) was found to have the lowest rate of recurrence at 6.7%. The type of mesh (human origin, bovine, or porcine) and type of stoma (colostomy vs. ileostomy) had no statistically significant effect on the rate of recurrence.

Total recurrences in the study patients was 18.9%, a figure consistent with the current literature on parastomal hernia repair, the investigators wrote.

A key factor in recurrence was type of incision. Keyhole incisions had a much lower rate of recurrence than did circular incisions (32% vs. 9.1%; P = .042).

In the study group, “one patient was readmitted for mesh infection within 30 days of the repair and required mesh removal. Even with the biologic mesh in place there was an overlying skin infection that warranted reoperation that resulted in the stoma being moved to a new site altogether,” the investigators wrote.

The limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of the research and the difficulty in diagnosing PSH, which is often asymptomatic, the investigators mentioned. In addition, the techniques for local PSH repair with biologic mesh are not fully standardized. Mesh type and location decisions are often made on a case-by-case basis which limits the applicability of the study data for general PSH repairs.

Dr. Hufford and his associates wrote, “Our results suggest local parastomal hernia repair with biological mesh is both a safe and effective method, especially when used with the sandwich technique for mesh placement, for definitive treatment of parastomal hernias with very low morbidity, and acceptable recurrence rate.”

The investigators reported no disclosures.

at 18.9%.

Theadore Hufford, MD, of the University of Illinois at Chicago and his colleagues conducted a study to look at the effects of placement and type of mesh on postop morbidity and recurrence of parastomal hernia (PSH). The study was a retrospective analysis of 58 patients who had undergone local PSH repair with biological mesh between July 2006 and July 2015 at a single medical center.

All procedures were conducted by three board-certified surgeons at a tertiary medical center, and decisions such as the mesh type, placement and incision type were determined by the attending surgeon’s operative preferences.

In the study group, mesh placement (overlay, underlay, or sandwich technique) was found to have a statistically significant effect on recurrence. Of the patients who received an underlay of biologic mesh, 33% had a recurrence, compared with 25% of those who had overlays. The sandwich technique (a combination of overlay and underlay) was found to have the lowest rate of recurrence at 6.7%. The type of mesh (human origin, bovine, or porcine) and type of stoma (colostomy vs. ileostomy) had no statistically significant effect on the rate of recurrence.

Total recurrences in the study patients was 18.9%, a figure consistent with the current literature on parastomal hernia repair, the investigators wrote.

A key factor in recurrence was type of incision. Keyhole incisions had a much lower rate of recurrence than did circular incisions (32% vs. 9.1%; P = .042).

In the study group, “one patient was readmitted for mesh infection within 30 days of the repair and required mesh removal. Even with the biologic mesh in place there was an overlying skin infection that warranted reoperation that resulted in the stoma being moved to a new site altogether,” the investigators wrote.

The limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of the research and the difficulty in diagnosing PSH, which is often asymptomatic, the investigators mentioned. In addition, the techniques for local PSH repair with biologic mesh are not fully standardized. Mesh type and location decisions are often made on a case-by-case basis which limits the applicability of the study data for general PSH repairs.

Dr. Hufford and his associates wrote, “Our results suggest local parastomal hernia repair with biological mesh is both a safe and effective method, especially when used with the sandwich technique for mesh placement, for definitive treatment of parastomal hernias with very low morbidity, and acceptable recurrence rate.”

The investigators reported no disclosures.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: In a comparison of the biologic meshes and placement techniques, the sandwich technique was most successful in preventing recurrence.

Major finding: Rate of recurrence of parastomal hernia was 33% with underlay surgical mesh placement, 25% with overlay placement, and 6.7% with sandwich placement.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 58 patients who had undergone local parastomal hernia repair with biological mesh at a single medical center.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no disclosures.

Source: Hufford T et al. Am J Surg. 2018 Jan. 215(1):88-90.

Withholding elective surgery in smokers, obese patients

No one will argue that obesity and tobacco aren’t serious public health issues, underlying many causes of morbidity and mortality. As a result, they’re driving factors behind a fair amount of health care spending.

In England, the county of Hertfordshire recently adopted a new approach to this: a ban on routine, nonurgent surgeries for both. Those with a body mass index of 30-40 kg/m2 must lose 10% of their weight over 9 months to qualify for a procedure, while those with a BMI above 40 must lose 15%. Smokers have to go 8 weeks without a cigarette and take breath tests to prove it.

The group that formulated the plan noted that resources to help these groups achieve such goals are (and will continue to be) freely available.

Not unexpectedly, the plan is controversial. Robert West, MD, a professor of health psychology and director of tobacco studies at the University College London, told CNN that “rationing treatment on the basis of unhealthy behaviors betrays an extraordinary naivety about what drives those behaviors.”

Of course, this debate is nothing new. In December 2014, I wrote about surgeons in the United States who were refusing to do elective hernia repairs on smokers because of their higher complication rates.

A lot of this is framed in terms of money, since that’s the driving factor. Obese patients and smokers do have higher rates of surgical complications in general, with longer recoveries and, hence, higher costs. This policy tries to put greater responsibility on patients to maintain their own health and well-being. After all, financial resources are a finite, shared commodity.

Like everything in modern health care, there’s no easy answer. Insurers and doctors try to balance better outcomes vs. greater good and cost savings.

Medicine is, and always will be, an ongoing experiment, where some things work, some don’t, and we learn from time and experience.

Unfortunately, patients and their doctors are often caught in the middle, trapped between market and political forces on one side and caring for those who need us on the other. That’s never good, or easy, for those directly involved with individual patients on the front lines of medical care.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

No one will argue that obesity and tobacco aren’t serious public health issues, underlying many causes of morbidity and mortality. As a result, they’re driving factors behind a fair amount of health care spending.

In England, the county of Hertfordshire recently adopted a new approach to this: a ban on routine, nonurgent surgeries for both. Those with a body mass index of 30-40 kg/m2 must lose 10% of their weight over 9 months to qualify for a procedure, while those with a BMI above 40 must lose 15%. Smokers have to go 8 weeks without a cigarette and take breath tests to prove it.

The group that formulated the plan noted that resources to help these groups achieve such goals are (and will continue to be) freely available.

Not unexpectedly, the plan is controversial. Robert West, MD, a professor of health psychology and director of tobacco studies at the University College London, told CNN that “rationing treatment on the basis of unhealthy behaviors betrays an extraordinary naivety about what drives those behaviors.”

Of course, this debate is nothing new. In December 2014, I wrote about surgeons in the United States who were refusing to do elective hernia repairs on smokers because of their higher complication rates.

A lot of this is framed in terms of money, since that’s the driving factor. Obese patients and smokers do have higher rates of surgical complications in general, with longer recoveries and, hence, higher costs. This policy tries to put greater responsibility on patients to maintain their own health and well-being. After all, financial resources are a finite, shared commodity.

Like everything in modern health care, there’s no easy answer. Insurers and doctors try to balance better outcomes vs. greater good and cost savings.

Medicine is, and always will be, an ongoing experiment, where some things work, some don’t, and we learn from time and experience.

Unfortunately, patients and their doctors are often caught in the middle, trapped between market and political forces on one side and caring for those who need us on the other. That’s never good, or easy, for those directly involved with individual patients on the front lines of medical care.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

No one will argue that obesity and tobacco aren’t serious public health issues, underlying many causes of morbidity and mortality. As a result, they’re driving factors behind a fair amount of health care spending.

In England, the county of Hertfordshire recently adopted a new approach to this: a ban on routine, nonurgent surgeries for both. Those with a body mass index of 30-40 kg/m2 must lose 10% of their weight over 9 months to qualify for a procedure, while those with a BMI above 40 must lose 15%. Smokers have to go 8 weeks without a cigarette and take breath tests to prove it.

The group that formulated the plan noted that resources to help these groups achieve such goals are (and will continue to be) freely available.

Not unexpectedly, the plan is controversial. Robert West, MD, a professor of health psychology and director of tobacco studies at the University College London, told CNN that “rationing treatment on the basis of unhealthy behaviors betrays an extraordinary naivety about what drives those behaviors.”

Of course, this debate is nothing new. In December 2014, I wrote about surgeons in the United States who were refusing to do elective hernia repairs on smokers because of their higher complication rates.

A lot of this is framed in terms of money, since that’s the driving factor. Obese patients and smokers do have higher rates of surgical complications in general, with longer recoveries and, hence, higher costs. This policy tries to put greater responsibility on patients to maintain their own health and well-being. After all, financial resources are a finite, shared commodity.

Like everything in modern health care, there’s no easy answer. Insurers and doctors try to balance better outcomes vs. greater good and cost savings.

Medicine is, and always will be, an ongoing experiment, where some things work, some don’t, and we learn from time and experience.

Unfortunately, patients and their doctors are often caught in the middle, trapped between market and political forces on one side and caring for those who need us on the other. That’s never good, or easy, for those directly involved with individual patients on the front lines of medical care.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Clinical trial: The Role of the Robotic Platform in Inguinal Hernia Repair Surgery

The Role of the Robotic Platform in Inguinal Hernia Repair Surgery is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients who require inguinal hernia repair surgery.

The trial will compare postoperative pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery repair or robotic inguinal hernia repair surgery. The laparoscopic approach has been used frequently and has several advantages. However, it has several disadvantages that the robotic approach may address. As such, the study investigators have hypothesized that the robotic approach will result in less postoperative pain than the laparoscopic approach.

The primary outcome measure is the difference in postoperative pain between patients who undergo robotic inguinal hernia repair and those who undergo laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair during the 2 years following surgery. Secondary outcome measures include differences in surgeon ergonomics between the two approaches, institution cost analysis, and long-term recurrence rate differences, all within 2 years of surgery.

The study will end in May 2019. About 100 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information on the study page at Clinicaltrials.gov.

SOURCE: Clinicaltrials.gov. NCT02816658.

The Role of the Robotic Platform in Inguinal Hernia Repair Surgery is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients who require inguinal hernia repair surgery.

The trial will compare postoperative pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery repair or robotic inguinal hernia repair surgery. The laparoscopic approach has been used frequently and has several advantages. However, it has several disadvantages that the robotic approach may address. As such, the study investigators have hypothesized that the robotic approach will result in less postoperative pain than the laparoscopic approach.

The primary outcome measure is the difference in postoperative pain between patients who undergo robotic inguinal hernia repair and those who undergo laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair during the 2 years following surgery. Secondary outcome measures include differences in surgeon ergonomics between the two approaches, institution cost analysis, and long-term recurrence rate differences, all within 2 years of surgery.

The study will end in May 2019. About 100 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information on the study page at Clinicaltrials.gov.

SOURCE: Clinicaltrials.gov. NCT02816658.

The Role of the Robotic Platform in Inguinal Hernia Repair Surgery is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients who require inguinal hernia repair surgery.

The trial will compare postoperative pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery repair or robotic inguinal hernia repair surgery. The laparoscopic approach has been used frequently and has several advantages. However, it has several disadvantages that the robotic approach may address. As such, the study investigators have hypothesized that the robotic approach will result in less postoperative pain than the laparoscopic approach.

The primary outcome measure is the difference in postoperative pain between patients who undergo robotic inguinal hernia repair and those who undergo laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair during the 2 years following surgery. Secondary outcome measures include differences in surgeon ergonomics between the two approaches, institution cost analysis, and long-term recurrence rate differences, all within 2 years of surgery.

The study will end in May 2019. About 100 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information on the study page at Clinicaltrials.gov.

SOURCE: Clinicaltrials.gov. NCT02816658.

FROM CLINICALTRIALS.GOV

Frailty, not age, predicted complications after ambulatory surgery

Frailty was associated with a significant increase in 30-day complications after ambulatory hernia repair or ambulatory surgery of the breast, thyroid, or parathyroid, according to the results of a large retrospective cohort study.

The findings reinforce prior work indicating that frailty, not chronologic age, should be a primary factor when deciding about and preparing for surgery, Carolyn D. Seib, MD, and her associates at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in JAMA Surgery. “Informed consent should be adjusted based on frailty to ensure that patients have an accurate assessment of their risk when making decisions about whether to undergo surgery,” the researchers said.

To test the hypothesis that frailty predicts morbidity and mortality after ambulatory general surgery, the researchers studied 140,828 patients older than 40 years from the 2007-2010 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (JAMA Surg. 2017 Oct 11. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4007). Nearly 2,500 (1.7%) patients experienced perioperative complications, and 0.7% had serious complications, the researchers said. After controlling for age sex, race or ethnicity, smoking, type of anesthesia, and corticosteroid use, patients with an intermediate (0.18-0.35) frailty score had a 70% higher odds of any complication (odds ratio, 1.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-1.9) and a 100% higher odds of serious complications (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.7-2.3), compared with patients with a low frailty score.

An intermediate score reflected the presence of two to three frailty traits, such as impaired functional status, history of diabetes, pneumonia, chronic cardiovascular or lung disease, or impaired sensorium, the investigators noted. Notably, having a high modified frailty index (four or more frailty traits) was associated with 3.3-fold higher odds of any complication and with nearly 4-fold higher odds of serious complications, even after controlling for potential confounders.

Among modifiable risk factors, only the use of local and monitored anesthesia was associated with a significant decrease in the likelihood of serious 30-day complications (adjusted OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.53-0.81). Single-center studies of elderly patients undergoing inguinal hernia repair have reported similar findings, the researchers said. “For frail patients who choose to undergo hernia repair, local and monitored anesthesia care should be used whenever possible,” they wrote. “The use of local with monitored anesthesia care may be challenging in complex surgical procedures for breast cancer, such as modified radical mastectomy or axillary dissection, but it should be considered for patients with increased anesthesia risk who are undergoing ambulatory breast surgery.”

The National Institute on Aging provided partial funding. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Frailty was associated with a significant increase in 30-day complications after ambulatory hernia repair or ambulatory surgery of the breast, thyroid, or parathyroid, according to the results of a large retrospective cohort study.

The findings reinforce prior work indicating that frailty, not chronologic age, should be a primary factor when deciding about and preparing for surgery, Carolyn D. Seib, MD, and her associates at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in JAMA Surgery. “Informed consent should be adjusted based on frailty to ensure that patients have an accurate assessment of their risk when making decisions about whether to undergo surgery,” the researchers said.

To test the hypothesis that frailty predicts morbidity and mortality after ambulatory general surgery, the researchers studied 140,828 patients older than 40 years from the 2007-2010 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (JAMA Surg. 2017 Oct 11. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4007). Nearly 2,500 (1.7%) patients experienced perioperative complications, and 0.7% had serious complications, the researchers said. After controlling for age sex, race or ethnicity, smoking, type of anesthesia, and corticosteroid use, patients with an intermediate (0.18-0.35) frailty score had a 70% higher odds of any complication (odds ratio, 1.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-1.9) and a 100% higher odds of serious complications (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.7-2.3), compared with patients with a low frailty score.

An intermediate score reflected the presence of two to three frailty traits, such as impaired functional status, history of diabetes, pneumonia, chronic cardiovascular or lung disease, or impaired sensorium, the investigators noted. Notably, having a high modified frailty index (four or more frailty traits) was associated with 3.3-fold higher odds of any complication and with nearly 4-fold higher odds of serious complications, even after controlling for potential confounders.

Among modifiable risk factors, only the use of local and monitored anesthesia was associated with a significant decrease in the likelihood of serious 30-day complications (adjusted OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.53-0.81). Single-center studies of elderly patients undergoing inguinal hernia repair have reported similar findings, the researchers said. “For frail patients who choose to undergo hernia repair, local and monitored anesthesia care should be used whenever possible,” they wrote. “The use of local with monitored anesthesia care may be challenging in complex surgical procedures for breast cancer, such as modified radical mastectomy or axillary dissection, but it should be considered for patients with increased anesthesia risk who are undergoing ambulatory breast surgery.”

The National Institute on Aging provided partial funding. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Frailty was associated with a significant increase in 30-day complications after ambulatory hernia repair or ambulatory surgery of the breast, thyroid, or parathyroid, according to the results of a large retrospective cohort study.

The findings reinforce prior work indicating that frailty, not chronologic age, should be a primary factor when deciding about and preparing for surgery, Carolyn D. Seib, MD, and her associates at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in JAMA Surgery. “Informed consent should be adjusted based on frailty to ensure that patients have an accurate assessment of their risk when making decisions about whether to undergo surgery,” the researchers said.

To test the hypothesis that frailty predicts morbidity and mortality after ambulatory general surgery, the researchers studied 140,828 patients older than 40 years from the 2007-2010 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (JAMA Surg. 2017 Oct 11. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4007). Nearly 2,500 (1.7%) patients experienced perioperative complications, and 0.7% had serious complications, the researchers said. After controlling for age sex, race or ethnicity, smoking, type of anesthesia, and corticosteroid use, patients with an intermediate (0.18-0.35) frailty score had a 70% higher odds of any complication (odds ratio, 1.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.5-1.9) and a 100% higher odds of serious complications (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.7-2.3), compared with patients with a low frailty score.

An intermediate score reflected the presence of two to three frailty traits, such as impaired functional status, history of diabetes, pneumonia, chronic cardiovascular or lung disease, or impaired sensorium, the investigators noted. Notably, having a high modified frailty index (four or more frailty traits) was associated with 3.3-fold higher odds of any complication and with nearly 4-fold higher odds of serious complications, even after controlling for potential confounders.

Among modifiable risk factors, only the use of local and monitored anesthesia was associated with a significant decrease in the likelihood of serious 30-day complications (adjusted OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.53-0.81). Single-center studies of elderly patients undergoing inguinal hernia repair have reported similar findings, the researchers said. “For frail patients who choose to undergo hernia repair, local and monitored anesthesia care should be used whenever possible,” they wrote. “The use of local with monitored anesthesia care may be challenging in complex surgical procedures for breast cancer, such as modified radical mastectomy or axillary dissection, but it should be considered for patients with increased anesthesia risk who are undergoing ambulatory breast surgery.”

The National Institute on Aging provided partial funding. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Frailty was an independent risk factor for 30-day complications of ambulatory surgery, independent of age and other correlates.

Major finding: Having an intermediate (0.18-0.35) frailty score increased the odds of any complication by 70% (OR, 1.7).

Data source: A single-center retrospective cohort study of 140,828 patients older than 40 years from the 2007-2010 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Disclosures: The investigators had no disclosures.

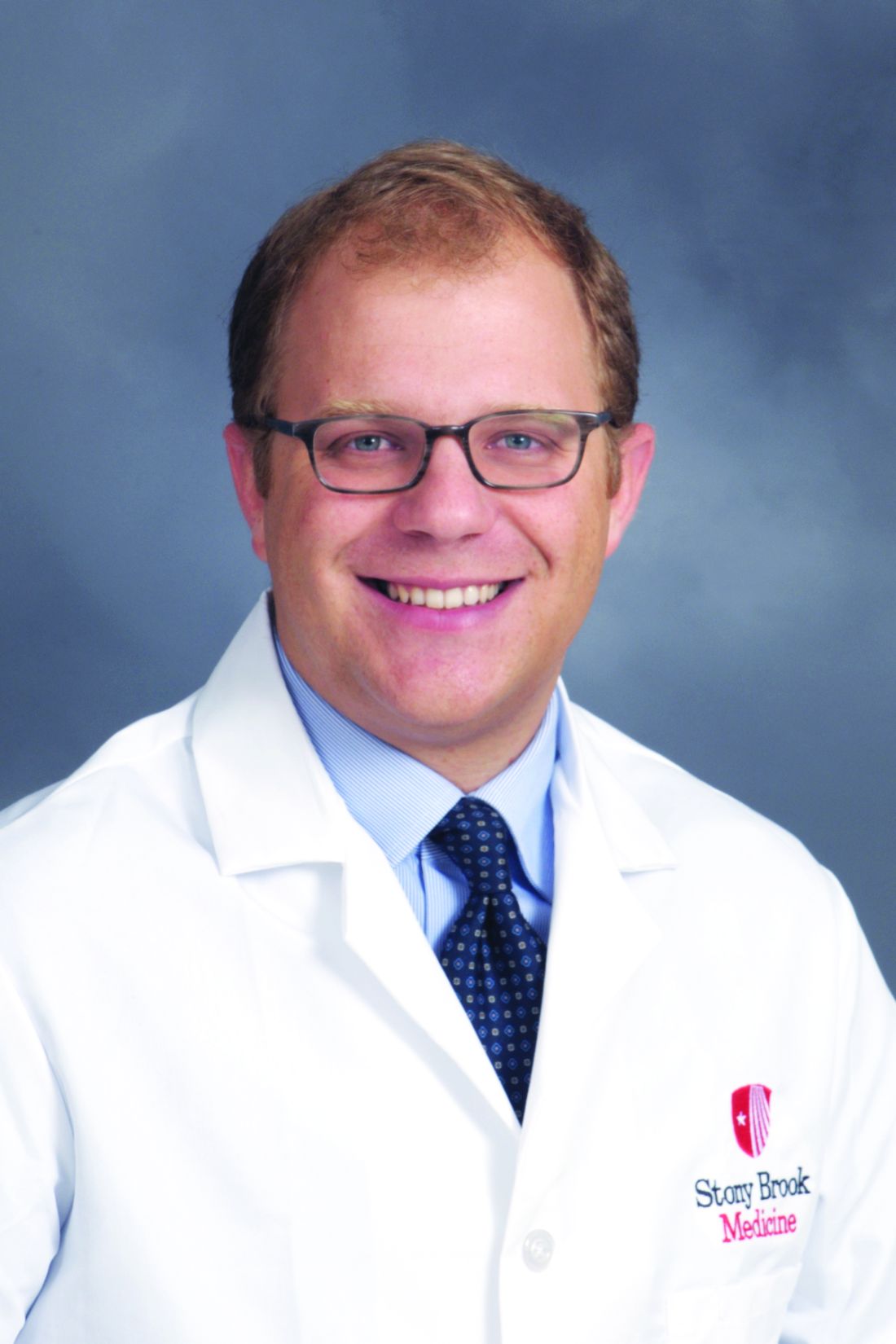

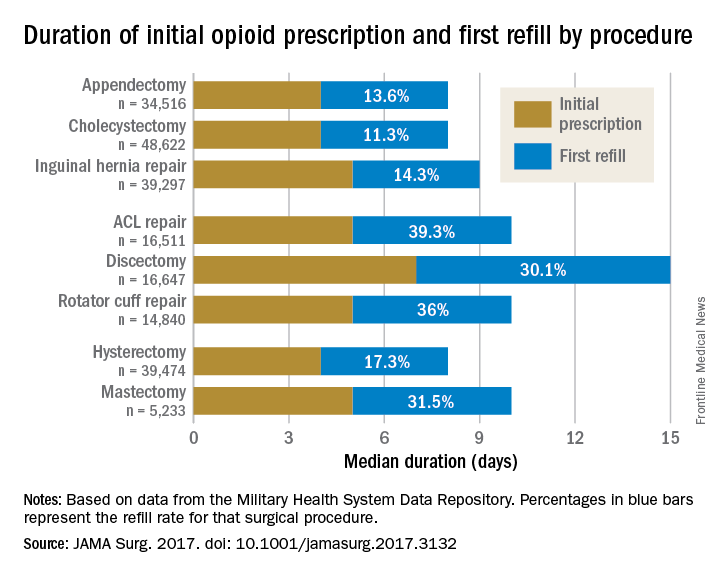

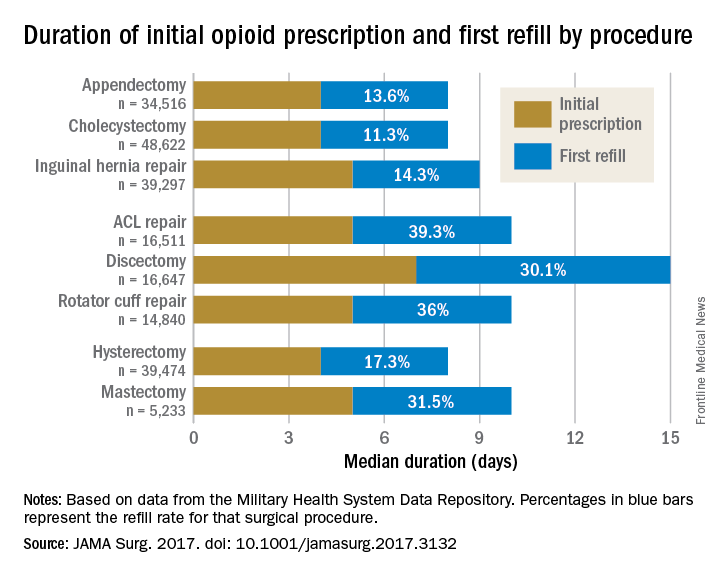

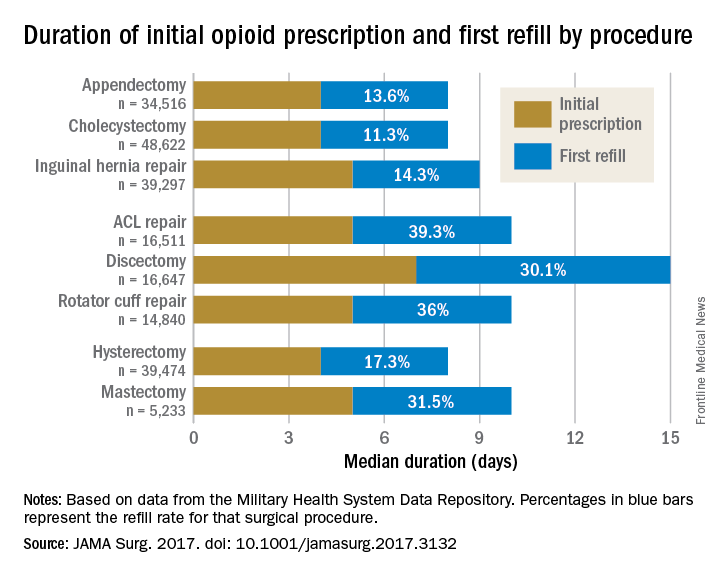

Seven days of opioids adequate for most hernia and other general surgery procedures

A 7-day limit on the initial opioid prescription may be sufficient for many common general surgery procedures, including hernia surgery and gynecologic procedures, findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Rebecca E. Scully, MD, of the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her associates examined opioid pain medication prescriptions and refills from records of the Military Health System Data Repository and the TRICARE insurance program of 215,140 opioid-naive patients. These patients were aged 18-64 years who underwent either cholecystectomy, appendectomy, inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, rotator cuff tear repair, discectomy, mastectomy, or hysterectomy (JAMA Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3132). Only 20% of the covered individuals are active members of the U.S. military. The mean age was 40 years; 50% were male, and 60% were white.

For appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and hysterectomy, the prescription was a median 4 days. For inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament repair, rotator cuff repair, and mastectomy, the initial prescription was for 5 days. For discectomy, the median was 7 days.

Refill rates were the least at 11.3% for cholecystectomy and the most at 39.3% after anterior cruciate ligament repair. The time after the initial prescription until a refill was a median 6 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and inguinal hernia repair, compared with a median 10 days for discectomy. The median duration of a refill prescription was 4 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, hernia repair, and hysterectomy versus 8 days for discectomy.

“Although 7 days appears to be more than adequate for many patients undergoing common general surgery and gynecologic procedures, prescription lengths likely should be extended to 10 days, particularly after common neurosurgical and musculoskeletal procedures, recognizing that as many as 40% of patients may still require one refill at a 7-day limit,” Dr. Scully and her associates said.

Although this study did not include rates of unused prescriptions or use of nonopioid pain relievers such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs, it did include a large population considered to be nationally representative “in many respects,” and it included a variety of procedures for which patients are commonly discharged to home, the researchers said.

The study was funded in part by the Department of Defense/Henry M. Jackson Foundation. The investigators had no conflict of interests. Adil H. Haider, MD, MPH, is deputy editor of JAMA Surgery, but he was not involved in any of the decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

A 7-day limit on the initial opioid prescription may be sufficient for many common general surgery procedures, including hernia surgery and gynecologic procedures, findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Rebecca E. Scully, MD, of the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her associates examined opioid pain medication prescriptions and refills from records of the Military Health System Data Repository and the TRICARE insurance program of 215,140 opioid-naive patients. These patients were aged 18-64 years who underwent either cholecystectomy, appendectomy, inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, rotator cuff tear repair, discectomy, mastectomy, or hysterectomy (JAMA Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3132). Only 20% of the covered individuals are active members of the U.S. military. The mean age was 40 years; 50% were male, and 60% were white.

For appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and hysterectomy, the prescription was a median 4 days. For inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament repair, rotator cuff repair, and mastectomy, the initial prescription was for 5 days. For discectomy, the median was 7 days.

Refill rates were the least at 11.3% for cholecystectomy and the most at 39.3% after anterior cruciate ligament repair. The time after the initial prescription until a refill was a median 6 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and inguinal hernia repair, compared with a median 10 days for discectomy. The median duration of a refill prescription was 4 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, hernia repair, and hysterectomy versus 8 days for discectomy.

“Although 7 days appears to be more than adequate for many patients undergoing common general surgery and gynecologic procedures, prescription lengths likely should be extended to 10 days, particularly after common neurosurgical and musculoskeletal procedures, recognizing that as many as 40% of patients may still require one refill at a 7-day limit,” Dr. Scully and her associates said.

Although this study did not include rates of unused prescriptions or use of nonopioid pain relievers such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs, it did include a large population considered to be nationally representative “in many respects,” and it included a variety of procedures for which patients are commonly discharged to home, the researchers said.

The study was funded in part by the Department of Defense/Henry M. Jackson Foundation. The investigators had no conflict of interests. Adil H. Haider, MD, MPH, is deputy editor of JAMA Surgery, but he was not involved in any of the decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

A 7-day limit on the initial opioid prescription may be sufficient for many common general surgery procedures, including hernia surgery and gynecologic procedures, findings of a large retrospective study suggest.

Rebecca E. Scully, MD, of the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and her associates examined opioid pain medication prescriptions and refills from records of the Military Health System Data Repository and the TRICARE insurance program of 215,140 opioid-naive patients. These patients were aged 18-64 years who underwent either cholecystectomy, appendectomy, inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, rotator cuff tear repair, discectomy, mastectomy, or hysterectomy (JAMA Surg. 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.3132). Only 20% of the covered individuals are active members of the U.S. military. The mean age was 40 years; 50% were male, and 60% were white.

For appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and hysterectomy, the prescription was a median 4 days. For inguinal hernia repair, anterior cruciate ligament repair, rotator cuff repair, and mastectomy, the initial prescription was for 5 days. For discectomy, the median was 7 days.

Refill rates were the least at 11.3% for cholecystectomy and the most at 39.3% after anterior cruciate ligament repair. The time after the initial prescription until a refill was a median 6 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and inguinal hernia repair, compared with a median 10 days for discectomy. The median duration of a refill prescription was 4 days for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, hernia repair, and hysterectomy versus 8 days for discectomy.

“Although 7 days appears to be more than adequate for many patients undergoing common general surgery and gynecologic procedures, prescription lengths likely should be extended to 10 days, particularly after common neurosurgical and musculoskeletal procedures, recognizing that as many as 40% of patients may still require one refill at a 7-day limit,” Dr. Scully and her associates said.

Although this study did not include rates of unused prescriptions or use of nonopioid pain relievers such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs, it did include a large population considered to be nationally representative “in many respects,” and it included a variety of procedures for which patients are commonly discharged to home, the researchers said.

The study was funded in part by the Department of Defense/Henry M. Jackson Foundation. The investigators had no conflict of interests. Adil H. Haider, MD, MPH, is deputy editor of JAMA Surgery, but he was not involved in any of the decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The initial opioid prescription was a median 4 days for appendectomy and cholecystectomy, a median 5 days for inguinal hernia repair and anterior cruciate ligament and rotator cuff repair, and a median 7 days for discectomy.

Data source: A study of opioid prescriptions in 215,140 surgery patients aged 18-64 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded in part by the Department of Defense/Henry M. Jackson Foundation. The investigators had no conflict of interests. Adil H. Haider, MD, MPH, is deputy editor of JAMA Surgery, but he was not involved in any of the decisions regarding review of the manuscript or its acceptance.

Hiatal hernia repair more common at time of sleeve gastrectomy, compared with RYGB

SAN DIEGO – Concomitant hiatal hernia repair is significantly more common at the time of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, compared with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, according to a retrospective analysis.

“GERD [gastroesophageal reflux disease] is common in patients with a high body mass index,” lead study author Dino Spaniolas, MD, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. “In fact, 35%-40% of patients who undergo bariatric surgery are diagnosed with a hiatal hernia, and the majority of them are diagnosed during surgery.”

In an effort to assess the differences in practice patterns in the performance of hiatal hernia repair during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), the researchers evaluated the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program public use files from 2015. They limited the analysis to LSG and LRYGB and also excluded revision procedures and patients with a history of foregut surgery.

In all, 130,686 patients were included in the study. Their mean age was 45 years, 79% were female, 75% were Caucasian, and their mean body mass index was 45.7 kg/m2. Most (70%) underwent LSG, while the remainder underwent LRYGB.

At baseline, a greater proportion of the LRYGB patients had a history of GERD than did LSG patients (37.2% vs. 28.6%, respectively; P less than .0001). They were also more likely to have hypertension (54.1% vs. 47.9%; P less than .0001), hyperlipidemia (29.9% vs. 23.2%; P less than .0001), and diabetes (35.5% vs. 23.3%; P less than .0001). Overall, about 15% of patients had a concomitant hiatal hernia repair in addition to their bariatric surgery.

Next, the investigators found what Dr. Spaniolas termed “the GERD paradox”: Although the LRYGB patients were more likely to have GERD before surgery, they were much less likely to undergo a hiatal hernia repair in addition to their bariatric procedure. Specifically, concomitant hiatal hernia repair was performed in 21% of LSG patients, compared with only 10.8% of LRYGB patients (P less than .0001). After investigators controlled for baseline BMI, preoperative GERD, and other patient characteristics, they found that LSG patients were 2.14 times more likely to undergo concomitant hiatal hernia repair, compared with LRYGB patients.

“This is a retrospective review, but nevertheless, I think we can conclude that these findings suggest that concomitant hiatal hernia repair is significantly more common after LSG, compared with LRYGB, despite having less GERD preoperatively,” Dr. Spaniolas said. “This suggests that there is a nationwide difference in the intraoperative management of hiatal hernia based on the type of planned bariatric procedure. This practice pattern needs to be considered while retrospectively assessing GERD-related outcomes of bariatric surgery in the future.”

Dr. Spaniolas disclosed that he has received research support from Merck and that he is a consultant for Mallinckrodt.

SAN DIEGO – Concomitant hiatal hernia repair is significantly more common at the time of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, compared with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, according to a retrospective analysis.

“GERD [gastroesophageal reflux disease] is common in patients with a high body mass index,” lead study author Dino Spaniolas, MD, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. “In fact, 35%-40% of patients who undergo bariatric surgery are diagnosed with a hiatal hernia, and the majority of them are diagnosed during surgery.”

In an effort to assess the differences in practice patterns in the performance of hiatal hernia repair during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), the researchers evaluated the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program public use files from 2015. They limited the analysis to LSG and LRYGB and also excluded revision procedures and patients with a history of foregut surgery.

In all, 130,686 patients were included in the study. Their mean age was 45 years, 79% were female, 75% were Caucasian, and their mean body mass index was 45.7 kg/m2. Most (70%) underwent LSG, while the remainder underwent LRYGB.

At baseline, a greater proportion of the LRYGB patients had a history of GERD than did LSG patients (37.2% vs. 28.6%, respectively; P less than .0001). They were also more likely to have hypertension (54.1% vs. 47.9%; P less than .0001), hyperlipidemia (29.9% vs. 23.2%; P less than .0001), and diabetes (35.5% vs. 23.3%; P less than .0001). Overall, about 15% of patients had a concomitant hiatal hernia repair in addition to their bariatric surgery.

Next, the investigators found what Dr. Spaniolas termed “the GERD paradox”: Although the LRYGB patients were more likely to have GERD before surgery, they were much less likely to undergo a hiatal hernia repair in addition to their bariatric procedure. Specifically, concomitant hiatal hernia repair was performed in 21% of LSG patients, compared with only 10.8% of LRYGB patients (P less than .0001). After investigators controlled for baseline BMI, preoperative GERD, and other patient characteristics, they found that LSG patients were 2.14 times more likely to undergo concomitant hiatal hernia repair, compared with LRYGB patients.

“This is a retrospective review, but nevertheless, I think we can conclude that these findings suggest that concomitant hiatal hernia repair is significantly more common after LSG, compared with LRYGB, despite having less GERD preoperatively,” Dr. Spaniolas said. “This suggests that there is a nationwide difference in the intraoperative management of hiatal hernia based on the type of planned bariatric procedure. This practice pattern needs to be considered while retrospectively assessing GERD-related outcomes of bariatric surgery in the future.”

Dr. Spaniolas disclosed that he has received research support from Merck and that he is a consultant for Mallinckrodt.

SAN DIEGO – Concomitant hiatal hernia repair is significantly more common at the time of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, compared with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, according to a retrospective analysis.

“GERD [gastroesophageal reflux disease] is common in patients with a high body mass index,” lead study author Dino Spaniolas, MD, said at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons. “In fact, 35%-40% of patients who undergo bariatric surgery are diagnosed with a hiatal hernia, and the majority of them are diagnosed during surgery.”

In an effort to assess the differences in practice patterns in the performance of hiatal hernia repair during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), the researchers evaluated the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program public use files from 2015. They limited the analysis to LSG and LRYGB and also excluded revision procedures and patients with a history of foregut surgery.

In all, 130,686 patients were included in the study. Their mean age was 45 years, 79% were female, 75% were Caucasian, and their mean body mass index was 45.7 kg/m2. Most (70%) underwent LSG, while the remainder underwent LRYGB.

At baseline, a greater proportion of the LRYGB patients had a history of GERD than did LSG patients (37.2% vs. 28.6%, respectively; P less than .0001). They were also more likely to have hypertension (54.1% vs. 47.9%; P less than .0001), hyperlipidemia (29.9% vs. 23.2%; P less than .0001), and diabetes (35.5% vs. 23.3%; P less than .0001). Overall, about 15% of patients had a concomitant hiatal hernia repair in addition to their bariatric surgery.

Next, the investigators found what Dr. Spaniolas termed “the GERD paradox”: Although the LRYGB patients were more likely to have GERD before surgery, they were much less likely to undergo a hiatal hernia repair in addition to their bariatric procedure. Specifically, concomitant hiatal hernia repair was performed in 21% of LSG patients, compared with only 10.8% of LRYGB patients (P less than .0001). After investigators controlled for baseline BMI, preoperative GERD, and other patient characteristics, they found that LSG patients were 2.14 times more likely to undergo concomitant hiatal hernia repair, compared with LRYGB patients.

“This is a retrospective review, but nevertheless, I think we can conclude that these findings suggest that concomitant hiatal hernia repair is significantly more common after LSG, compared with LRYGB, despite having less GERD preoperatively,” Dr. Spaniolas said. “This suggests that there is a nationwide difference in the intraoperative management of hiatal hernia based on the type of planned bariatric procedure. This practice pattern needs to be considered while retrospectively assessing GERD-related outcomes of bariatric surgery in the future.”

Dr. Spaniolas disclosed that he has received research support from Merck and that he is a consultant for Mallinckrodt.

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: LSG patients are more likely to undergo concomitant hiatal hernia repair, compared with LRYGB patients.

Major finding: According to multivariate analysis, LSG patients were more likely to undergo concomitant HH repair (odds ratio, 2.14).

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 130,686 patients who underwent bariatric surgery in 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Spaniolas disclosed that he has received research support from Merck and that he is a consultant for Mallinckrodt.

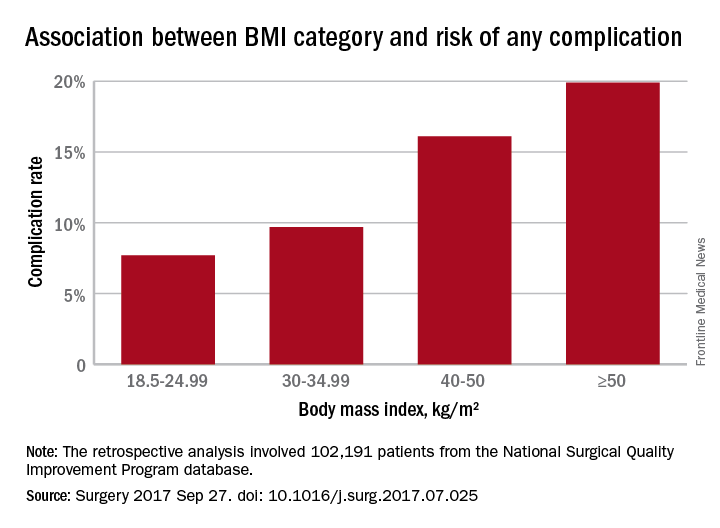

Obesity increases risk of complications with hernia repair

Both obese and underweight patients undergoing ventral hernia repair have a significantly greater risk of complications, particularly if they have strangulated/reducible hernias, according to data published online in Surgery.

In a retrospective analysis, researchers examined data from 102,191 patients – 58.5% of whom were obese – who underwent ventral hernia repair, and found a J-shaped curve in the association between complication rates and body mass index.

Underweight patients with a BMI less than 18.5kg/m2 had a 10% risk of complications, while those of normal BMI (18.5-24.99) had the lowest complication risk: 7.7%. Complication rates then increased steadily with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese (Surgery 2017, Sep 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.07.025).

Analysis by individual medical complications showed that postoperative pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, and urinary tract infection were all statistically significantly more common with increasing BMI. The risk of myocardial infarction did not differ significantly with BMI.

The researchers also examined the effects of different hernia types. The 70.3% of patients who had reducible hernias had lower complication rates overall, as well as lower rates of complications in each category of operative, medical, and respiratory, compared with the 29.7% of patients with strangulated/incarcerated hernias.

Nearly one-quarter of the patients in the study were undergoing recurrent ventral hernia repair, and these patients were more likely to have a higher BMI.

After taking into account variables such as age, smoking comorbidities, type of hernia, and type of repair, the authors concluded that the odds of having any complication increased significantly above a BMI of 30 kg/m2, using normal weight BMI as a reference. The odds were 22% higher in those with BMIs in the 30-34.99 range, 54% higher for those in the 35-39.99 range, twofold higher for those with a BMI between 40 and 50, and 2.6-fold higher above 50 kg/m2.

“Surgeons are presented with increasing numbers of obese patients, and the best way to manage ventral hernias in this population remains unclear,” the authors wrote, although they raised the possibility that laparoscopic procedures reduce the risk of some complications.

“Although the majority of VHRs performed utilize an open technique, studies have found decreased duration of stay, morbidity, and, in selected studies, even decreased recurrence using the laparoscopic approach.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Both obese and underweight patients undergoing ventral hernia repair have a significantly greater risk of complications, particularly if they have strangulated/reducible hernias, according to data published online in Surgery.

In a retrospective analysis, researchers examined data from 102,191 patients – 58.5% of whom were obese – who underwent ventral hernia repair, and found a J-shaped curve in the association between complication rates and body mass index.

Underweight patients with a BMI less than 18.5kg/m2 had a 10% risk of complications, while those of normal BMI (18.5-24.99) had the lowest complication risk: 7.7%. Complication rates then increased steadily with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese (Surgery 2017, Sep 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.07.025).

Analysis by individual medical complications showed that postoperative pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, and urinary tract infection were all statistically significantly more common with increasing BMI. The risk of myocardial infarction did not differ significantly with BMI.

The researchers also examined the effects of different hernia types. The 70.3% of patients who had reducible hernias had lower complication rates overall, as well as lower rates of complications in each category of operative, medical, and respiratory, compared with the 29.7% of patients with strangulated/incarcerated hernias.

Nearly one-quarter of the patients in the study were undergoing recurrent ventral hernia repair, and these patients were more likely to have a higher BMI.

After taking into account variables such as age, smoking comorbidities, type of hernia, and type of repair, the authors concluded that the odds of having any complication increased significantly above a BMI of 30 kg/m2, using normal weight BMI as a reference. The odds were 22% higher in those with BMIs in the 30-34.99 range, 54% higher for those in the 35-39.99 range, twofold higher for those with a BMI between 40 and 50, and 2.6-fold higher above 50 kg/m2.

“Surgeons are presented with increasing numbers of obese patients, and the best way to manage ventral hernias in this population remains unclear,” the authors wrote, although they raised the possibility that laparoscopic procedures reduce the risk of some complications.

“Although the majority of VHRs performed utilize an open technique, studies have found decreased duration of stay, morbidity, and, in selected studies, even decreased recurrence using the laparoscopic approach.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Both obese and underweight patients undergoing ventral hernia repair have a significantly greater risk of complications, particularly if they have strangulated/reducible hernias, according to data published online in Surgery.

In a retrospective analysis, researchers examined data from 102,191 patients – 58.5% of whom were obese – who underwent ventral hernia repair, and found a J-shaped curve in the association between complication rates and body mass index.

Underweight patients with a BMI less than 18.5kg/m2 had a 10% risk of complications, while those of normal BMI (18.5-24.99) had the lowest complication risk: 7.7%. Complication rates then increased steadily with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese (Surgery 2017, Sep 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.07.025).

Analysis by individual medical complications showed that postoperative pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, acute renal failure, and urinary tract infection were all statistically significantly more common with increasing BMI. The risk of myocardial infarction did not differ significantly with BMI.

The researchers also examined the effects of different hernia types. The 70.3% of patients who had reducible hernias had lower complication rates overall, as well as lower rates of complications in each category of operative, medical, and respiratory, compared with the 29.7% of patients with strangulated/incarcerated hernias.

Nearly one-quarter of the patients in the study were undergoing recurrent ventral hernia repair, and these patients were more likely to have a higher BMI.

After taking into account variables such as age, smoking comorbidities, type of hernia, and type of repair, the authors concluded that the odds of having any complication increased significantly above a BMI of 30 kg/m2, using normal weight BMI as a reference. The odds were 22% higher in those with BMIs in the 30-34.99 range, 54% higher for those in the 35-39.99 range, twofold higher for those with a BMI between 40 and 50, and 2.6-fold higher above 50 kg/m2.

“Surgeons are presented with increasing numbers of obese patients, and the best way to manage ventral hernias in this population remains unclear,” the authors wrote, although they raised the possibility that laparoscopic procedures reduce the risk of some complications.

“Although the majority of VHRs performed utilize an open technique, studies have found decreased duration of stay, morbidity, and, in selected studies, even decreased recurrence using the laparoscopic approach.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM SURGERY

Key clinical point: Obesity, as well as underweight, are associated with significantly higher rates of complications with ventral repair.

Major finding: Complication rates increased with increasing BMI; 8.2% for overweight patients, 9.7% for the obese, 12.2% for the severely obese, 16.1% for the morbidly obese, and 19.9% for the super obese.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 102,191 patients who underwent ventral hernia repair.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Clinical trial: Mesh weights compared for ventral hernia repair

A clinical trial comparing heavy- and medium-weight surgical mesh for ventral hernia repairs is recruiting patients.

The Long-term Results of Heavy Weight Versus Medium Weight Mesh in Ventral Hernia Repair trial will determine if mesh weight has an impact on postoperative pain, ventral hernia recurrence, incidence of deep wound infection, and overall quality of life following ventral hernia repair with mesh.

Patients will be included if they have a ventral hernia, are 18 years of age or older, have a defect classified as CDC wound class 1, are able to achieve midline fascial closure, have a hernia defect width less than or equal to 20 cm, can tolerate general anesthesia, and can give informed consent. Patients will be excluded if they have undergone emergent ventral hernia repair, undergone laparoscopic or robotic ventral hernia repair, undergone staged repair of their ventral hernia, or are pregnant at the time of the surgery.

The primary outcome of this trial is pain that will be measured via the NIH Promis 3A Pain instrument in 1 year postoperatively. Other outcomes include hernia recurrence, to be determined via the Ventral Hernia Recurrence Inventory; the occurrence of a deep wound infection, to be determined by physical examination and/or computed tomography scanning; and quality of life measured by the HerQLes questionnaire.

Find more information at clinicaltrials.gov.

A clinical trial comparing heavy- and medium-weight surgical mesh for ventral hernia repairs is recruiting patients.

The Long-term Results of Heavy Weight Versus Medium Weight Mesh in Ventral Hernia Repair trial will determine if mesh weight has an impact on postoperative pain, ventral hernia recurrence, incidence of deep wound infection, and overall quality of life following ventral hernia repair with mesh.

Patients will be included if they have a ventral hernia, are 18 years of age or older, have a defect classified as CDC wound class 1, are able to achieve midline fascial closure, have a hernia defect width less than or equal to 20 cm, can tolerate general anesthesia, and can give informed consent. Patients will be excluded if they have undergone emergent ventral hernia repair, undergone laparoscopic or robotic ventral hernia repair, undergone staged repair of their ventral hernia, or are pregnant at the time of the surgery.

The primary outcome of this trial is pain that will be measured via the NIH Promis 3A Pain instrument in 1 year postoperatively. Other outcomes include hernia recurrence, to be determined via the Ventral Hernia Recurrence Inventory; the occurrence of a deep wound infection, to be determined by physical examination and/or computed tomography scanning; and quality of life measured by the HerQLes questionnaire.

Find more information at clinicaltrials.gov.

A clinical trial comparing heavy- and medium-weight surgical mesh for ventral hernia repairs is recruiting patients.

The Long-term Results of Heavy Weight Versus Medium Weight Mesh in Ventral Hernia Repair trial will determine if mesh weight has an impact on postoperative pain, ventral hernia recurrence, incidence of deep wound infection, and overall quality of life following ventral hernia repair with mesh.

Patients will be included if they have a ventral hernia, are 18 years of age or older, have a defect classified as CDC wound class 1, are able to achieve midline fascial closure, have a hernia defect width less than or equal to 20 cm, can tolerate general anesthesia, and can give informed consent. Patients will be excluded if they have undergone emergent ventral hernia repair, undergone laparoscopic or robotic ventral hernia repair, undergone staged repair of their ventral hernia, or are pregnant at the time of the surgery.

The primary outcome of this trial is pain that will be measured via the NIH Promis 3A Pain instrument in 1 year postoperatively. Other outcomes include hernia recurrence, to be determined via the Ventral Hernia Recurrence Inventory; the occurrence of a deep wound infection, to be determined by physical examination and/or computed tomography scanning; and quality of life measured by the HerQLes questionnaire.

Find more information at clinicaltrials.gov.

FROM CLINICALTRIALS.GOV

Clinical trial: Complex VHR using biologic or synthetic mesh

The Study Comparing the Efficacy, Safety, and Cost of a Permanent, Synthetic Prosthetic Versus a Biologic Prosthetic in the One-Stage Repair of Ventral Hernias in Clean and Contaminated Wounds is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients with ventral hernias.

The trial will compare results of ventral hernia repair in patients who have received a biologic mesh made from pig skin with those who received a synthetic mesh made in a laboratory. Both study groups will include patients with and without infection near the hernia. Synthetic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of early postoperative infection, while biologic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of recurrence.

Patients will be included in the trial if they have a ventral hernia; are older than 21 years; are not pregnant; and have no allergic, religious, or ethical objections to polypropylene or porcine prosthetics. Reasons for exclusion include severe malnutrition, pre-existing parenchymal liver disease, immunocompromisation, and refractory ascites.

The primary outcome measure is recurrence within 24 months of surgery, and the secondary outcome measure is wound events within 24 months of surgery. Other outcome measures include early postoperative complications within 1 month of surgery and quality of life, pain, activity level, and overall cost with 24 months of surgery.

The study will end in June 2019. About 330 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information at the study page on Clinicaltrials.gov.

The Study Comparing the Efficacy, Safety, and Cost of a Permanent, Synthetic Prosthetic Versus a Biologic Prosthetic in the One-Stage Repair of Ventral Hernias in Clean and Contaminated Wounds is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients with ventral hernias.

The trial will compare results of ventral hernia repair in patients who have received a biologic mesh made from pig skin with those who received a synthetic mesh made in a laboratory. Both study groups will include patients with and without infection near the hernia. Synthetic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of early postoperative infection, while biologic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of recurrence.

Patients will be included in the trial if they have a ventral hernia; are older than 21 years; are not pregnant; and have no allergic, religious, or ethical objections to polypropylene or porcine prosthetics. Reasons for exclusion include severe malnutrition, pre-existing parenchymal liver disease, immunocompromisation, and refractory ascites.

The primary outcome measure is recurrence within 24 months of surgery, and the secondary outcome measure is wound events within 24 months of surgery. Other outcome measures include early postoperative complications within 1 month of surgery and quality of life, pain, activity level, and overall cost with 24 months of surgery.

The study will end in June 2019. About 330 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information at the study page on Clinicaltrials.gov.

The Study Comparing the Efficacy, Safety, and Cost of a Permanent, Synthetic Prosthetic Versus a Biologic Prosthetic in the One-Stage Repair of Ventral Hernias in Clean and Contaminated Wounds is an interventional trial currently recruiting patients with ventral hernias.

The trial will compare results of ventral hernia repair in patients who have received a biologic mesh made from pig skin with those who received a synthetic mesh made in a laboratory. Both study groups will include patients with and without infection near the hernia. Synthetic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of early postoperative infection, while biologic mesh is hypothesized to have a higher rate of recurrence.

Patients will be included in the trial if they have a ventral hernia; are older than 21 years; are not pregnant; and have no allergic, religious, or ethical objections to polypropylene or porcine prosthetics. Reasons for exclusion include severe malnutrition, pre-existing parenchymal liver disease, immunocompromisation, and refractory ascites.

The primary outcome measure is recurrence within 24 months of surgery, and the secondary outcome measure is wound events within 24 months of surgery. Other outcome measures include early postoperative complications within 1 month of surgery and quality of life, pain, activity level, and overall cost with 24 months of surgery.

The study will end in June 2019. About 330 people are expected to be included in the final analysis.

Find more information at the study page on Clinicaltrials.gov.

SUMMARY FROM CLINICALTRIALS.GOV

Fewer complications, lower mortality with minimally invasive hernia repair

Minimally invasive surgical techniques are now used in nearly 80% of operations for paraesophageal hernia repair (PEH) and are associated with many outcome improvements, in comparison with open surgery, according to a retrospective study of data from nearly 100,000 cases.

“Many studies have shown improved perioperative outcomes in paraesophageal hernia repair with MIS [minimally invasive surgery] approaches, but the optimal approach is still debated,” wrote Patrick J. McLaren, MD, and his colleagues from the division of gastrointestinal and general surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. “In addition, the extent to which MIS has been adopted on the national level for PEH repair is unknown.” Their research letter was published online Aug. 23 in JAMA Surgery.

They found that the proportion of repair conducted using minimally invasive techniques increased from 9.8% in 2002 to 79.6% in 2012. At the same time, in-hospital mortality associated with paraesophageal hernia repair declined from 3.5% to 1.2%, and the rates of complications dropped from 29.8% to 20.6%.

Compared with open-repair procedures, minimally invasive surgery was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality (0.6% vs. 3%; P less than .001); wound complications (0.4% vs. 2.9%; P less than .001); septic complications (0.9% vs. 3.9%; P less than .001); and bleeding complications (0.6% vs. 1.8%; P less than .001), as well as urinary, respiratory, and cardiac complications, and intraoperative injury. No significant differences were seen between the two groups in the incidence of thromboembolic complications.

The mean length of hospital stay was 4.2 days in patients who underwent surgery using minimally invasive techniques, compared with 8.5 days in those who had open surgery.

The authors noted that early research on MIS for PEH raised the question of a possible higher risk of recurrence. While the study did not examine the incidence of hernia recurrence, the authors cited data showing that improvements in minimally invasive surgical techniques have been linked to a reduction in hiatal hernia recurrences.

“Studies have found that recurrences requiring reoperation after MIS repairs are low at 2.2%-6%,” the authors wrote. “Regardless, a role remains for open PEH repairs in cases of multiple prior abdominal operations and acute strangulation and in patients with an unstable condition.”

The study was funded by the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

This article was updated August 23, 2017.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques are now used in nearly 80% of operations for paraesophageal hernia repair (PEH) and are associated with many outcome improvements, in comparison with open surgery, according to a retrospective study of data from nearly 100,000 cases.

“Many studies have shown improved perioperative outcomes in paraesophageal hernia repair with MIS [minimally invasive surgery] approaches, but the optimal approach is still debated,” wrote Patrick J. McLaren, MD, and his colleagues from the division of gastrointestinal and general surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. “In addition, the extent to which MIS has been adopted on the national level for PEH repair is unknown.” Their research letter was published online Aug. 23 in JAMA Surgery.

They found that the proportion of repair conducted using minimally invasive techniques increased from 9.8% in 2002 to 79.6% in 2012. At the same time, in-hospital mortality associated with paraesophageal hernia repair declined from 3.5% to 1.2%, and the rates of complications dropped from 29.8% to 20.6%.

Compared with open-repair procedures, minimally invasive surgery was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality (0.6% vs. 3%; P less than .001); wound complications (0.4% vs. 2.9%; P less than .001); septic complications (0.9% vs. 3.9%; P less than .001); and bleeding complications (0.6% vs. 1.8%; P less than .001), as well as urinary, respiratory, and cardiac complications, and intraoperative injury. No significant differences were seen between the two groups in the incidence of thromboembolic complications.

The mean length of hospital stay was 4.2 days in patients who underwent surgery using minimally invasive techniques, compared with 8.5 days in those who had open surgery.

The authors noted that early research on MIS for PEH raised the question of a possible higher risk of recurrence. While the study did not examine the incidence of hernia recurrence, the authors cited data showing that improvements in minimally invasive surgical techniques have been linked to a reduction in hiatal hernia recurrences.

“Studies have found that recurrences requiring reoperation after MIS repairs are low at 2.2%-6%,” the authors wrote. “Regardless, a role remains for open PEH repairs in cases of multiple prior abdominal operations and acute strangulation and in patients with an unstable condition.”

The study was funded by the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

This article was updated August 23, 2017.

Minimally invasive surgical techniques are now used in nearly 80% of operations for paraesophageal hernia repair (PEH) and are associated with many outcome improvements, in comparison with open surgery, according to a retrospective study of data from nearly 100,000 cases.

“Many studies have shown improved perioperative outcomes in paraesophageal hernia repair with MIS [minimally invasive surgery] approaches, but the optimal approach is still debated,” wrote Patrick J. McLaren, MD, and his colleagues from the division of gastrointestinal and general surgery at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. “In addition, the extent to which MIS has been adopted on the national level for PEH repair is unknown.” Their research letter was published online Aug. 23 in JAMA Surgery.

They found that the proportion of repair conducted using minimally invasive techniques increased from 9.8% in 2002 to 79.6% in 2012. At the same time, in-hospital mortality associated with paraesophageal hernia repair declined from 3.5% to 1.2%, and the rates of complications dropped from 29.8% to 20.6%.

Compared with open-repair procedures, minimally invasive surgery was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality (0.6% vs. 3%; P less than .001); wound complications (0.4% vs. 2.9%; P less than .001); septic complications (0.9% vs. 3.9%; P less than .001); and bleeding complications (0.6% vs. 1.8%; P less than .001), as well as urinary, respiratory, and cardiac complications, and intraoperative injury. No significant differences were seen between the two groups in the incidence of thromboembolic complications.

The mean length of hospital stay was 4.2 days in patients who underwent surgery using minimally invasive techniques, compared with 8.5 days in those who had open surgery.

The authors noted that early research on MIS for PEH raised the question of a possible higher risk of recurrence. While the study did not examine the incidence of hernia recurrence, the authors cited data showing that improvements in minimally invasive surgical techniques have been linked to a reduction in hiatal hernia recurrences.

“Studies have found that recurrences requiring reoperation after MIS repairs are low at 2.2%-6%,” the authors wrote. “Regardless, a role remains for open PEH repairs in cases of multiple prior abdominal operations and acute strangulation and in patients with an unstable condition.”

The study was funded by the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

This article was updated August 23, 2017.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Minimally invasive surgery for paraesophageal hernia repair is associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality and complication rates than open repair.

Major finding: Compared with open-repair procedures, minimally invasive paraesophageal hernia repair was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality, wound, septic, bleeding, urinary, respiratory, and cardiac complications, and intraoperative injury.

Data source: A retrospective review of 97,393 inpatient admissions for paraesophageal hernia repair between 2002 and 2012.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.