User login

Lower abdominal pain and dehydration

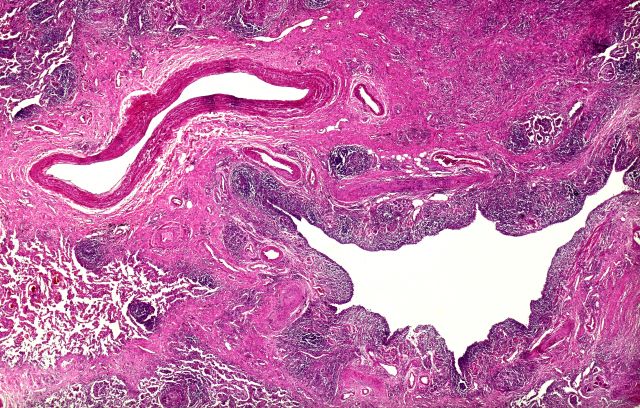

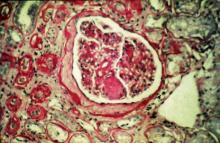

The diagnosis in this patient is ulcerative colitis (UC) on the basis of physical examination, laboratory values, and endoscopy. However, this patient has the most extensive form, pancolitis, which means that inflammation and damage extend the entire length of the colon.

The diagnosis of UC is best made with endoscopy and mucosal biopsy for histopathology. Characteristic findings are abnormal erythematous mucosa, with or without ulceration, extending from the rectum to a part or all of the colon and uniform inflammation, without intervening areas of normal mucosa (skip lesions tend to characterize Crohn disease). Contact bleeding may also be observed, with mucus identified in the lumen of the bowel.

The bowel wall is thin or of normal thickness, but edema, accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give it the appearance of a thickened bowel wall. The disease is largely confined to the mucosa and, to a lesser extent, the submucosa.

Laboratory studies are helpful to exclude other diagnoses and assess the patient's nutritional status, and serologic markers aid in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Radiographic imaging has an important role in differentiation of UC from Crohn disease. Fistulas or the presence of small bowel disease are seen only in Crohn disease.

According the American Gastroenterological Association, drug classes for the long-term management of moderate to severe UC include tumor necrosis factor–alpha antagonists, anti-integrin agent (vedolizumab), Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib), interleukin 12/23 antagonist (ustekinumab), and immunomodulators (thiopurines, methotrexate). Most drugs that are initiated for the induction of remission are continued as maintenance therapy if they are effective. This is not the case, however, if corticosteroids or cyclosporine are necessary to induce remission.

This patient's pancolitis presentation is also acute and severe, defined as more than 6 bloody bowel movements per day plus one of the following: fever > 100.4 °F, hemoglobin level < 10.5 g/dL, heart rate > 90 beats/min, erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 30 mm/h, or C-reactive protein level > 30 mg/dL). This requires hospitalization and treatment with intravenous corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 400 mg/d or methylprednisolone 60 mg/d). Considered a medical emergency, the situation requires prompt recognition and multidisciplinary management. In patients who fail therapy with 3-5 days of intravenous corticosteroids, medical rescue therapy is indicated with either infliximab or cyclosporine. If all measures fail, the patient may need emergency surgery.

Hospitalized patients with acute severe UC have short-term colectomy rates of 25%-30%.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The diagnosis in this patient is ulcerative colitis (UC) on the basis of physical examination, laboratory values, and endoscopy. However, this patient has the most extensive form, pancolitis, which means that inflammation and damage extend the entire length of the colon.

The diagnosis of UC is best made with endoscopy and mucosal biopsy for histopathology. Characteristic findings are abnormal erythematous mucosa, with or without ulceration, extending from the rectum to a part or all of the colon and uniform inflammation, without intervening areas of normal mucosa (skip lesions tend to characterize Crohn disease). Contact bleeding may also be observed, with mucus identified in the lumen of the bowel.

The bowel wall is thin or of normal thickness, but edema, accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give it the appearance of a thickened bowel wall. The disease is largely confined to the mucosa and, to a lesser extent, the submucosa.

Laboratory studies are helpful to exclude other diagnoses and assess the patient's nutritional status, and serologic markers aid in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Radiographic imaging has an important role in differentiation of UC from Crohn disease. Fistulas or the presence of small bowel disease are seen only in Crohn disease.

According the American Gastroenterological Association, drug classes for the long-term management of moderate to severe UC include tumor necrosis factor–alpha antagonists, anti-integrin agent (vedolizumab), Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib), interleukin 12/23 antagonist (ustekinumab), and immunomodulators (thiopurines, methotrexate). Most drugs that are initiated for the induction of remission are continued as maintenance therapy if they are effective. This is not the case, however, if corticosteroids or cyclosporine are necessary to induce remission.

This patient's pancolitis presentation is also acute and severe, defined as more than 6 bloody bowel movements per day plus one of the following: fever > 100.4 °F, hemoglobin level < 10.5 g/dL, heart rate > 90 beats/min, erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 30 mm/h, or C-reactive protein level > 30 mg/dL). This requires hospitalization and treatment with intravenous corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 400 mg/d or methylprednisolone 60 mg/d). Considered a medical emergency, the situation requires prompt recognition and multidisciplinary management. In patients who fail therapy with 3-5 days of intravenous corticosteroids, medical rescue therapy is indicated with either infliximab or cyclosporine. If all measures fail, the patient may need emergency surgery.

Hospitalized patients with acute severe UC have short-term colectomy rates of 25%-30%.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The diagnosis in this patient is ulcerative colitis (UC) on the basis of physical examination, laboratory values, and endoscopy. However, this patient has the most extensive form, pancolitis, which means that inflammation and damage extend the entire length of the colon.

The diagnosis of UC is best made with endoscopy and mucosal biopsy for histopathology. Characteristic findings are abnormal erythematous mucosa, with or without ulceration, extending from the rectum to a part or all of the colon and uniform inflammation, without intervening areas of normal mucosa (skip lesions tend to characterize Crohn disease). Contact bleeding may also be observed, with mucus identified in the lumen of the bowel.

The bowel wall is thin or of normal thickness, but edema, accumulation of fat, and hypertrophy of the muscle layer may give it the appearance of a thickened bowel wall. The disease is largely confined to the mucosa and, to a lesser extent, the submucosa.

Laboratory studies are helpful to exclude other diagnoses and assess the patient's nutritional status, and serologic markers aid in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Radiographic imaging has an important role in differentiation of UC from Crohn disease. Fistulas or the presence of small bowel disease are seen only in Crohn disease.

According the American Gastroenterological Association, drug classes for the long-term management of moderate to severe UC include tumor necrosis factor–alpha antagonists, anti-integrin agent (vedolizumab), Janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib), interleukin 12/23 antagonist (ustekinumab), and immunomodulators (thiopurines, methotrexate). Most drugs that are initiated for the induction of remission are continued as maintenance therapy if they are effective. This is not the case, however, if corticosteroids or cyclosporine are necessary to induce remission.

This patient's pancolitis presentation is also acute and severe, defined as more than 6 bloody bowel movements per day plus one of the following: fever > 100.4 °F, hemoglobin level < 10.5 g/dL, heart rate > 90 beats/min, erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 30 mm/h, or C-reactive protein level > 30 mg/dL). This requires hospitalization and treatment with intravenous corticosteroids (hydrocortisone 400 mg/d or methylprednisolone 60 mg/d). Considered a medical emergency, the situation requires prompt recognition and multidisciplinary management. In patients who fail therapy with 3-5 days of intravenous corticosteroids, medical rescue therapy is indicated with either infliximab or cyclosporine. If all measures fail, the patient may need emergency surgery.

Hospitalized patients with acute severe UC have short-term colectomy rates of 25%-30%.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 76-year-old man presents with complaints of severe lower abdominal pain and dehydration. He reports bloody diarrhea of 2 weeks' duration and an unintentional 12-lb weight loss. Dietary alterations and loperamide have not helped. He has a fever of 102.1 °F. Medications include naproxen 440 mg/d for osteoarthritis, losartan 50 mg/d and amlodipine 5 mg/d for hypertension, and simvastatin 20 mg/d for dyslipidemia.

Physical examination reveals tenderness, particularly at the left lower quadrant of the abdomen, without rebound tenderness or guarding. Bowel sounds are active. He has a purulent rectal discharge. Stool cultures for the pathogens are negative. He has hypoalbuminemia (2.5 g/dL). He is positive for perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen test is negative. C-reactive protein is 32 mg/dL.

The patient is admitted to the hospital and receives intravenous fluids. Colonoscopy reveals inflammation and visible ulcers in the mucosa throughout the entire length of the colon.

Episodes of visual disturbance

On the basis of the history, examination, and investigations, retinal migraine was diagnosed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (1.2 migraine with aura; 1.2.4 retinal migraine). This classification system describes retinal migraine as a subtype of migraine with aura.

Retinal migraine (also called ophthalmic or ocular migraine) is relatively rare but is sometimes a cause of transient monocular blindness in young adults. It manifests as recurrent attacks of unilateral visual disturbance (positive symptoms) or blindness (negative symptoms) lasting from minutes to 1 hour, associated with minimal or no headache.

Some patients describe a positive visual symptom/disturbance in a mosaic pattern of scotomata that gradually enlarge, producing total or near-total unilateral visual loss. Precipitating factors may include emotional stress, hypertension, and hormonal contraceptive pills, as well as exercise, high altitude, dehydration, smoking, hypoglycemia, and hyperthermia.

Retinal migraine is believed to result from transient vasospasm of the choroidal or retinal arteries. A history of recurrent attacks of transient monocular visual disturbance or blindness, with or without a headache and without other neurologic symptoms, can suggest retinal migraine. A personal or family history of migraine can confirm the diagnosis.

Ruling out eye disease or vascular causes, especially when risk factors for arteriosclerosis exist, is important; that is, the condition must be differentiated from ocular or vascular causes of transient monocular blindness, mainly carotid artery disease.

Carotid duplex ultrasonography, transcranial Doppler ultrasonography, magnetic resonance angiography, or CT angiography of the brain may be helpful. Fluorescein or cerebral angiography is rarely necessary. A hypercoagulability workup and evaluation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be useful in excluding other coagulation disorders associated with retinal vasculopathy.

Regarding management, calcium-channel blockers have shown some efficacy. Even in patients with low blood pressure, nifedipine 10-20 mg/d is generally tolerated. From the available literature on treatment of this condition, it is recommended that triptans, ergots, and beta-blockers be used with caution or avoided in patients with retinal migraine owing to the potential for exacerbating vasoconstriction of the retinal artery. Transient vision loss in retinal migraine has been associated with future onset of permanent vision loss from occlusive conditions such as central retinal artery occlusion and branch retinal artery occlusion.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the history, examination, and investigations, retinal migraine was diagnosed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (1.2 migraine with aura; 1.2.4 retinal migraine). This classification system describes retinal migraine as a subtype of migraine with aura.

Retinal migraine (also called ophthalmic or ocular migraine) is relatively rare but is sometimes a cause of transient monocular blindness in young adults. It manifests as recurrent attacks of unilateral visual disturbance (positive symptoms) or blindness (negative symptoms) lasting from minutes to 1 hour, associated with minimal or no headache.

Some patients describe a positive visual symptom/disturbance in a mosaic pattern of scotomata that gradually enlarge, producing total or near-total unilateral visual loss. Precipitating factors may include emotional stress, hypertension, and hormonal contraceptive pills, as well as exercise, high altitude, dehydration, smoking, hypoglycemia, and hyperthermia.

Retinal migraine is believed to result from transient vasospasm of the choroidal or retinal arteries. A history of recurrent attacks of transient monocular visual disturbance or blindness, with or without a headache and without other neurologic symptoms, can suggest retinal migraine. A personal or family history of migraine can confirm the diagnosis.

Ruling out eye disease or vascular causes, especially when risk factors for arteriosclerosis exist, is important; that is, the condition must be differentiated from ocular or vascular causes of transient monocular blindness, mainly carotid artery disease.

Carotid duplex ultrasonography, transcranial Doppler ultrasonography, magnetic resonance angiography, or CT angiography of the brain may be helpful. Fluorescein or cerebral angiography is rarely necessary. A hypercoagulability workup and evaluation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be useful in excluding other coagulation disorders associated with retinal vasculopathy.

Regarding management, calcium-channel blockers have shown some efficacy. Even in patients with low blood pressure, nifedipine 10-20 mg/d is generally tolerated. From the available literature on treatment of this condition, it is recommended that triptans, ergots, and beta-blockers be used with caution or avoided in patients with retinal migraine owing to the potential for exacerbating vasoconstriction of the retinal artery. Transient vision loss in retinal migraine has been associated with future onset of permanent vision loss from occlusive conditions such as central retinal artery occlusion and branch retinal artery occlusion.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the history, examination, and investigations, retinal migraine was diagnosed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (1.2 migraine with aura; 1.2.4 retinal migraine). This classification system describes retinal migraine as a subtype of migraine with aura.

Retinal migraine (also called ophthalmic or ocular migraine) is relatively rare but is sometimes a cause of transient monocular blindness in young adults. It manifests as recurrent attacks of unilateral visual disturbance (positive symptoms) or blindness (negative symptoms) lasting from minutes to 1 hour, associated with minimal or no headache.

Some patients describe a positive visual symptom/disturbance in a mosaic pattern of scotomata that gradually enlarge, producing total or near-total unilateral visual loss. Precipitating factors may include emotional stress, hypertension, and hormonal contraceptive pills, as well as exercise, high altitude, dehydration, smoking, hypoglycemia, and hyperthermia.

Retinal migraine is believed to result from transient vasospasm of the choroidal or retinal arteries. A history of recurrent attacks of transient monocular visual disturbance or blindness, with or without a headache and without other neurologic symptoms, can suggest retinal migraine. A personal or family history of migraine can confirm the diagnosis.

Ruling out eye disease or vascular causes, especially when risk factors for arteriosclerosis exist, is important; that is, the condition must be differentiated from ocular or vascular causes of transient monocular blindness, mainly carotid artery disease.

Carotid duplex ultrasonography, transcranial Doppler ultrasonography, magnetic resonance angiography, or CT angiography of the brain may be helpful. Fluorescein or cerebral angiography is rarely necessary. A hypercoagulability workup and evaluation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be useful in excluding other coagulation disorders associated with retinal vasculopathy.

Regarding management, calcium-channel blockers have shown some efficacy. Even in patients with low blood pressure, nifedipine 10-20 mg/d is generally tolerated. From the available literature on treatment of this condition, it is recommended that triptans, ergots, and beta-blockers be used with caution or avoided in patients with retinal migraine owing to the potential for exacerbating vasoconstriction of the retinal artery. Transient vision loss in retinal migraine has been associated with future onset of permanent vision loss from occlusive conditions such as central retinal artery occlusion and branch retinal artery occlusion.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 23-year-old woman presents with sudden recurrent episodes of visual disturbance (extreme blurriness and partial blindness) in her right eye. She had seven or eight episodes over 30 hours; each episode lasted for 5-7 minutes, with spontaneous and full recovery. These were not associated with flashes of light, tingling, numbness, fever, or headache. She was asymptomatic between episodes.

She had normal vision in her left eye during these episodes, which she checked by covering both eyes alternately with her hands. The only significant history was four episodes of migraine with aura 3 years ago, which resolved spontaneously and did not recur. Family history was noncontributory. She had no history of illicit drug use or alcohol use.

On examination, her vital signs were normal. Blood pressure was 110/80 mm Hg, pulse 85 beats/min, and respiratory rate 16 breaths/min. There was no lymphadenopathy, and jugular venous pressure was not elevated. Visual acuity was 6/6, with normal visual fields and perimetry. Fundoscopy was normal. Complete blood count, liver function tests, renal function tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, antineutrophil antibodies, electrocardiography, transthoracic echocardiography, carotid Doppler, and MRI of the brain with contrast were all normal. She is taking no medications.

Flickering sensation in eyes

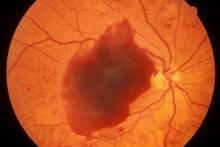

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) position statement on diabetic retinopathy states that hyperglycemia has been the most consistently associated risk factor for retinopathy. A large and consistent set of observational studies and clinical trials confirms the association of poor glucose control and retinopathy.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), a randomized controlled clinical trial of intensive glycemic control vs conventional glycemic control in people with type 1 diabetes (T1D), demonstrated that intensive therapy reduced the development or progression of diabetic retinopathy by 34%-76%. The DCCT also demonstrated a definitive relationship between hyperglycemia and diabetic microvascular complications, including retinopathy. Early treatment with intensive therapy was effective.

The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) of patients with newly diagnosed T2D conclusively demonstrated that improved blood glucose control reduced the risk for retinopathy and nephropathy and, possibly, neuropathy. The overall microvascular complication rate was decreased by 25% in patients receiving intensive therapy vs conventional therapy. Epidemiologic analysis of the UKPDS data showed a continuous relationship between the risk for microvascular complications and glycemia, such that every percentage-point decrease in A1c (eg, 9% to 8%) was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk for microvascular complications.

More recently, the ACCORD trial of medical therapies demonstrated that intensive glycemic control reduced the risk for progression of diabetic retinopathy in people with T2D of 10 years' duration. This study included 2856 ACCORD participants enrolled in the ACCORD Eye Study and followed for 4 years.

The ADA recommends screening by an ophthalmologist for diabetic retinopathy within 5 years of the diagnosis of T1D and at the time of diagnosis of T2D. Women with preexisting diabetes who are planning pregnancy or who have become pregnant should be screened before pregnancy or in the first trimester.

While optimization of blood glucose, blood pressure, and serum lipid levels in conjunction with appropriately scheduled dilated eye examinations can substantially decrease the risk for vision loss from diabetic retinopathy, a significant proportion of those affected with diabetes develop diabetic macular edema or proliferative changes that require intervention. ADA treatment recommendations are:

• Refer patients with any level of macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (a precursor of proliferative diabetic retinopathy), or proliferative diabetic retinopathy to an ophthalmologist knowledgeable and experienced in the management and treatment of diabetic retinopathy.

• Laser photocoagulation therapy reduces the risk for vision loss in patients with high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy and, in some cases, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy.

• Intravitreous injections of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor are indicated for central-involved diabetic macular edema, which occurs beneath the foveal center and may threaten reading vision.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) position statement on diabetic retinopathy states that hyperglycemia has been the most consistently associated risk factor for retinopathy. A large and consistent set of observational studies and clinical trials confirms the association of poor glucose control and retinopathy.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), a randomized controlled clinical trial of intensive glycemic control vs conventional glycemic control in people with type 1 diabetes (T1D), demonstrated that intensive therapy reduced the development or progression of diabetic retinopathy by 34%-76%. The DCCT also demonstrated a definitive relationship between hyperglycemia and diabetic microvascular complications, including retinopathy. Early treatment with intensive therapy was effective.

The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) of patients with newly diagnosed T2D conclusively demonstrated that improved blood glucose control reduced the risk for retinopathy and nephropathy and, possibly, neuropathy. The overall microvascular complication rate was decreased by 25% in patients receiving intensive therapy vs conventional therapy. Epidemiologic analysis of the UKPDS data showed a continuous relationship between the risk for microvascular complications and glycemia, such that every percentage-point decrease in A1c (eg, 9% to 8%) was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk for microvascular complications.

More recently, the ACCORD trial of medical therapies demonstrated that intensive glycemic control reduced the risk for progression of diabetic retinopathy in people with T2D of 10 years' duration. This study included 2856 ACCORD participants enrolled in the ACCORD Eye Study and followed for 4 years.

The ADA recommends screening by an ophthalmologist for diabetic retinopathy within 5 years of the diagnosis of T1D and at the time of diagnosis of T2D. Women with preexisting diabetes who are planning pregnancy or who have become pregnant should be screened before pregnancy or in the first trimester.

While optimization of blood glucose, blood pressure, and serum lipid levels in conjunction with appropriately scheduled dilated eye examinations can substantially decrease the risk for vision loss from diabetic retinopathy, a significant proportion of those affected with diabetes develop diabetic macular edema or proliferative changes that require intervention. ADA treatment recommendations are:

• Refer patients with any level of macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (a precursor of proliferative diabetic retinopathy), or proliferative diabetic retinopathy to an ophthalmologist knowledgeable and experienced in the management and treatment of diabetic retinopathy.

• Laser photocoagulation therapy reduces the risk for vision loss in patients with high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy and, in some cases, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy.

• Intravitreous injections of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor are indicated for central-involved diabetic macular edema, which occurs beneath the foveal center and may threaten reading vision.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) position statement on diabetic retinopathy states that hyperglycemia has been the most consistently associated risk factor for retinopathy. A large and consistent set of observational studies and clinical trials confirms the association of poor glucose control and retinopathy.

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), a randomized controlled clinical trial of intensive glycemic control vs conventional glycemic control in people with type 1 diabetes (T1D), demonstrated that intensive therapy reduced the development or progression of diabetic retinopathy by 34%-76%. The DCCT also demonstrated a definitive relationship between hyperglycemia and diabetic microvascular complications, including retinopathy. Early treatment with intensive therapy was effective.

The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) of patients with newly diagnosed T2D conclusively demonstrated that improved blood glucose control reduced the risk for retinopathy and nephropathy and, possibly, neuropathy. The overall microvascular complication rate was decreased by 25% in patients receiving intensive therapy vs conventional therapy. Epidemiologic analysis of the UKPDS data showed a continuous relationship between the risk for microvascular complications and glycemia, such that every percentage-point decrease in A1c (eg, 9% to 8%) was associated with a 35% reduction in the risk for microvascular complications.

More recently, the ACCORD trial of medical therapies demonstrated that intensive glycemic control reduced the risk for progression of diabetic retinopathy in people with T2D of 10 years' duration. This study included 2856 ACCORD participants enrolled in the ACCORD Eye Study and followed for 4 years.

The ADA recommends screening by an ophthalmologist for diabetic retinopathy within 5 years of the diagnosis of T1D and at the time of diagnosis of T2D. Women with preexisting diabetes who are planning pregnancy or who have become pregnant should be screened before pregnancy or in the first trimester.

While optimization of blood glucose, blood pressure, and serum lipid levels in conjunction with appropriately scheduled dilated eye examinations can substantially decrease the risk for vision loss from diabetic retinopathy, a significant proportion of those affected with diabetes develop diabetic macular edema or proliferative changes that require intervention. ADA treatment recommendations are:

• Refer patients with any level of macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (a precursor of proliferative diabetic retinopathy), or proliferative diabetic retinopathy to an ophthalmologist knowledgeable and experienced in the management and treatment of diabetic retinopathy.

• Laser photocoagulation therapy reduces the risk for vision loss in patients with high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy and, in some cases, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy.

• Intravitreous injections of anti–vascular endothelial growth factor are indicated for central-involved diabetic macular edema, which occurs beneath the foveal center and may threaten reading vision.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 48-year-old Black man with type 2 diabetes (T2D) presented with complaints of a "flickering" sensation and a decrease in brightness of colors in both eyes as well as floaters in his left eye for several weeks. He reported that his symptoms fluctuate with changes in his blood glucose levels. His last eye examination was 2 years ago and his ocular history was unremarkable. His medical history was significant with a history of hypertension and T2D requiring insulin. His most recent glycated hemoglobin (A1c), 2 months ago, was 8.4%. His BMI was 31.2. The patient's medications were dulaglutide 0.75 mg injection pen, glargine insulin 42 units, losartan 100 mg, and amlodipine 10 mg.

On examination, his best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left eye. Confrontation fields were intact, extraocular movements were full and extensive, and both pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light without afferent pupillary defects. Anterior segment examination was unremarkable in both eyes, without iris neovascularization. Intraocular pressures were 17 mm Hg in the right eye and 16 mm Hg in the left eye. On dilated fundus examination, the cup-to-disc ratio was 0.45 horizontally and vertically, with the presence of 1/4 disc diameters of neovascularization of the disc in the right eye and 2/3 disc diameters of neovascularization of the disc in the left eye.

Posterior segment findings were significant for scattered microaneurysms and dot/blot hemorrhages in the maculae. In the periphery of both eyes, there were tortuous vessels, scatter microaneurysms with dot/blot hemorrhages, and multiple areas of neovascularization elsewhere, with several foci of vitreous traction. There was no vitreous hemorrhage or tractional retinal detachment of either eye.

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography revealed an epiretinal membrane in the right eye and a blunted foveal contour with parafoveal cystic spaces, probably secondary to vitreomacular contraction. The left eye also had an epiretinal membrane and blunted foveal contour secondary to vitreomacular adhesion. The patient was diagnosed with bilateral high-risk proliferative diabetic retinopathy.

Pain and photophobia

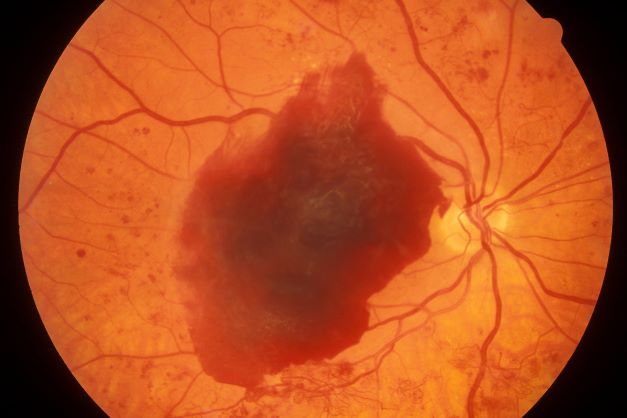

On the basis of the patient's medical history and presentation, this is probably a case of uveitis, a common extra-articular manifestation of psoriatic disease. In fact, the presence of uveitis can help distinguish PsA from osteoarthritis. Uveitis is characterized by inflammation of the uvea tract, with the retina, optic nerve, vitreous body, and sclera potentially becoming inflamed as well. Among patients with PsA, the prevalence of uveitis rises with ongoing disease duration, though the condition may also precede the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis, and is common among patients with severe psoriatic disease in Western and Asian populations. Overall, the prevalence of uveitis has been estimated to be 6%-9%. HLA-B27 genotype is strongly associated with uveitis in patients with concomitant PsA.

Symptoms of uveitis, as seen in the present case, include blurred vision, photophobia, pain, and ciliary flush. The condition is classified as anterior, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis, with the majority of cases diagnosed as anterior. In anterior uveitis, the inflamed pupil may become constricted or take on an irregular shape caused by iris adhesions to the anterior lens capsule. Uveitis in PsA is bilateral and has a chronic relapsing course. Onset is typically insidious.

Workup for uveitis should comprise visual acuity testing, slit lamp biomicroscopy, measurement of intraocular pressures, and a dilated eye exam. Conditions in the differential which threaten a patient's sight include retinal vasculitis, vitritis, cystoid macular edema, Behçet disease, and tubulo-interstitial nephritis. Other autoimmune diseases which can cause uveitis with systemic manifestations (multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, lupus) should be investigated. Infectious causes must also be eliminated. However, considering this patient's history of psoriatic disease, uveitis should be highly suspected.

Uveitis demands urgent treatment to control ocular inflammation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are the recommended first-line and second-line treatment for PsA, including in patients with complications such as uveitis. However, etanercept should not be used as it is less effective than adalimumab or other TNF inhibitors for uveitis. Because uveitis may sometimes respond to MTX therapy, patients with severe PsA may use a biologic agent in combination with MTX if they have had a partial response to current MTX therapy, as recommended by the American College of Rheumatology.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's medical history and presentation, this is probably a case of uveitis, a common extra-articular manifestation of psoriatic disease. In fact, the presence of uveitis can help distinguish PsA from osteoarthritis. Uveitis is characterized by inflammation of the uvea tract, with the retina, optic nerve, vitreous body, and sclera potentially becoming inflamed as well. Among patients with PsA, the prevalence of uveitis rises with ongoing disease duration, though the condition may also precede the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis, and is common among patients with severe psoriatic disease in Western and Asian populations. Overall, the prevalence of uveitis has been estimated to be 6%-9%. HLA-B27 genotype is strongly associated with uveitis in patients with concomitant PsA.

Symptoms of uveitis, as seen in the present case, include blurred vision, photophobia, pain, and ciliary flush. The condition is classified as anterior, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis, with the majority of cases diagnosed as anterior. In anterior uveitis, the inflamed pupil may become constricted or take on an irregular shape caused by iris adhesions to the anterior lens capsule. Uveitis in PsA is bilateral and has a chronic relapsing course. Onset is typically insidious.

Workup for uveitis should comprise visual acuity testing, slit lamp biomicroscopy, measurement of intraocular pressures, and a dilated eye exam. Conditions in the differential which threaten a patient's sight include retinal vasculitis, vitritis, cystoid macular edema, Behçet disease, and tubulo-interstitial nephritis. Other autoimmune diseases which can cause uveitis with systemic manifestations (multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, lupus) should be investigated. Infectious causes must also be eliminated. However, considering this patient's history of psoriatic disease, uveitis should be highly suspected.

Uveitis demands urgent treatment to control ocular inflammation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are the recommended first-line and second-line treatment for PsA, including in patients with complications such as uveitis. However, etanercept should not be used as it is less effective than adalimumab or other TNF inhibitors for uveitis. Because uveitis may sometimes respond to MTX therapy, patients with severe PsA may use a biologic agent in combination with MTX if they have had a partial response to current MTX therapy, as recommended by the American College of Rheumatology.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's medical history and presentation, this is probably a case of uveitis, a common extra-articular manifestation of psoriatic disease. In fact, the presence of uveitis can help distinguish PsA from osteoarthritis. Uveitis is characterized by inflammation of the uvea tract, with the retina, optic nerve, vitreous body, and sclera potentially becoming inflamed as well. Among patients with PsA, the prevalence of uveitis rises with ongoing disease duration, though the condition may also precede the development of PsA in patients with psoriasis, and is common among patients with severe psoriatic disease in Western and Asian populations. Overall, the prevalence of uveitis has been estimated to be 6%-9%. HLA-B27 genotype is strongly associated with uveitis in patients with concomitant PsA.

Symptoms of uveitis, as seen in the present case, include blurred vision, photophobia, pain, and ciliary flush. The condition is classified as anterior, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis, with the majority of cases diagnosed as anterior. In anterior uveitis, the inflamed pupil may become constricted or take on an irregular shape caused by iris adhesions to the anterior lens capsule. Uveitis in PsA is bilateral and has a chronic relapsing course. Onset is typically insidious.

Workup for uveitis should comprise visual acuity testing, slit lamp biomicroscopy, measurement of intraocular pressures, and a dilated eye exam. Conditions in the differential which threaten a patient's sight include retinal vasculitis, vitritis, cystoid macular edema, Behçet disease, and tubulo-interstitial nephritis. Other autoimmune diseases which can cause uveitis with systemic manifestations (multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, lupus) should be investigated. Infectious causes must also be eliminated. However, considering this patient's history of psoriatic disease, uveitis should be highly suspected.

Uveitis demands urgent treatment to control ocular inflammation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are the recommended first-line and second-line treatment for PsA, including in patients with complications such as uveitis. However, etanercept should not be used as it is less effective than adalimumab or other TNF inhibitors for uveitis. Because uveitis may sometimes respond to MTX therapy, patients with severe PsA may use a biologic agent in combination with MTX if they have had a partial response to current MTX therapy, as recommended by the American College of Rheumatology.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, Professor of Medicine (retired), Temple University School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh; Chairman, Department of Medicine Emeritus, Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, PA.

Herbert S. Diamond, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 48-year-old male patient presents with blurred vision, pain, and photophobia. He recently had a routine visit with an ophthalmologist, which was normal. The affected pupil appears irregular in shape. The anterior chamber appears foggy. Local ciliary flush is observed on slit lamp exam. The physical examination is also notable for axial arthropathy. The patient has an 11-year history of moderate to severe psoriatic arthritis (PsA) which he typically manages with methotrexate (MTX) therapy, to which he has had a partial response. He was initially diagnosed when he presented with worsening psoriasis and enthesitis on the insertion sites of the plantar fascia, as well as dactylitis.

Dry cough and dyspnea

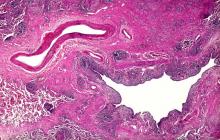

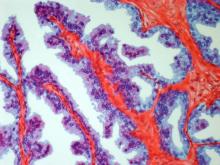

Based on the patient's presentation and workup, the likely diagnosis is adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, a relatively rare subtype of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Adenosquamous carcinoma displays qualities of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma; for definitive diagnosis, the cancer must contain 10% of each of these major NSCLC subtypes. Maeda and colleagues concluded that adenosquamous carcinoma occurs more frequently among men and that the age at the time of diagnosis is higher among such cancers compared with adenocarcinoma. Several studies have confirmed that adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung is also more prevalent among smokers.

Though a diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma may be suspected after small biopsies, cytology, or excisional biopsies, definitive diagnosis necessitates a resection specimen. If any adenocarcinoma component is observed in a biopsy specimen that is otherwise squamous, as in the present case, this finding is an indication for molecular testing. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations may be present in adenosquamous carcinoma cancers, despite a majority of cancers with EGFR mutations being among nonsmokers or former light smokers with adenocarcinoma histology. In addition, even for patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma should be considered if genetic testing suggests EGFR mutations.

Relative to adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma has higher grade malignancy, more advanced postoperative stage, and stronger lymph nodal invasiveness. In terms of treatment, surgical resection is the curative option for adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, with lobectomy with lymphadenectomy considered for first-line treatment. Though the most beneficial chemotherapy regimen for patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung remains the subject of investigation, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the current standard treatment option. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be an effective option for EGFR-positive patients.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on the patient's presentation and workup, the likely diagnosis is adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, a relatively rare subtype of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Adenosquamous carcinoma displays qualities of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma; for definitive diagnosis, the cancer must contain 10% of each of these major NSCLC subtypes. Maeda and colleagues concluded that adenosquamous carcinoma occurs more frequently among men and that the age at the time of diagnosis is higher among such cancers compared with adenocarcinoma. Several studies have confirmed that adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung is also more prevalent among smokers.

Though a diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma may be suspected after small biopsies, cytology, or excisional biopsies, definitive diagnosis necessitates a resection specimen. If any adenocarcinoma component is observed in a biopsy specimen that is otherwise squamous, as in the present case, this finding is an indication for molecular testing. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations may be present in adenosquamous carcinoma cancers, despite a majority of cancers with EGFR mutations being among nonsmokers or former light smokers with adenocarcinoma histology. In addition, even for patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma should be considered if genetic testing suggests EGFR mutations.

Relative to adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma has higher grade malignancy, more advanced postoperative stage, and stronger lymph nodal invasiveness. In terms of treatment, surgical resection is the curative option for adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, with lobectomy with lymphadenectomy considered for first-line treatment. Though the most beneficial chemotherapy regimen for patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung remains the subject of investigation, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the current standard treatment option. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be an effective option for EGFR-positive patients.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Based on the patient's presentation and workup, the likely diagnosis is adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, a relatively rare subtype of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Adenosquamous carcinoma displays qualities of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma; for definitive diagnosis, the cancer must contain 10% of each of these major NSCLC subtypes. Maeda and colleagues concluded that adenosquamous carcinoma occurs more frequently among men and that the age at the time of diagnosis is higher among such cancers compared with adenocarcinoma. Several studies have confirmed that adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung is also more prevalent among smokers.

Though a diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma may be suspected after small biopsies, cytology, or excisional biopsies, definitive diagnosis necessitates a resection specimen. If any adenocarcinoma component is observed in a biopsy specimen that is otherwise squamous, as in the present case, this finding is an indication for molecular testing. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations may be present in adenosquamous carcinoma cancers, despite a majority of cancers with EGFR mutations being among nonsmokers or former light smokers with adenocarcinoma histology. In addition, even for patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma should be considered if genetic testing suggests EGFR mutations.

Relative to adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma has higher grade malignancy, more advanced postoperative stage, and stronger lymph nodal invasiveness. In terms of treatment, surgical resection is the curative option for adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung, with lobectomy with lymphadenectomy considered for first-line treatment. Though the most beneficial chemotherapy regimen for patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung remains the subject of investigation, platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is the current standard treatment option. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be an effective option for EGFR-positive patients.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 58-year-old man with a 20-year–pack history of smoking initially presented with a persistent dry cough and dyspnea. Clubbing was noted on physical examination and breath sounds in the right upper lung were weak. Other than hypertension, which the patient manages with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, medical history is unremarkable. The patient notes that this medication has always made him cough, but dyspnea has only developed over the past 6 weeks. Respiratory symptoms prompted a chest radiograph which revealed a mass in the upper lobe of the right lung. Transbronchial lung biopsy of the right lung reveals components of adenocarcinoma; the specimen is otherwise squamous.

Diarrhea and weight loss

On the basis of the patient's presentation and history, this is probably a case of Crohn disease. Considering that the age of onset of Crohn disease has a bimodal distribution, this case is representative of late-onset disease. Among patients diagnosed with Crohn disease, the first peak is seen between 15 and 30 years of age, whereas the second peak, occurring in up to 15% of diagnoses, is observed mainly in women between 60 and 70 years of age. A significant proportion of Crohn disease cases are heritable. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing the condition than any other ethnic group.

According to American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be considered in older patients who present with diarrhea, rectal bleeding, urgency, abdominal pain, or weight loss. Fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin measurement may help identify patients who warrant further endoscopic evaluation. Colonoscopy is indicated for patients presenting with chronic diarrhea or hematochezia due to suspected IBD, microscopic colitis, or colorectal neoplasia.

Upon further workup for IBD, signs that suggest Crohn disease rather than ulcerative colitis (UC) are sparing of the rectum; discontinuous involvement with skip areas, deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Antiglycan antibodies are more prevalent in Crohn disease than in ulcerative colitis, but they are not sensitive. Weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are common in Crohn disease but uncommon in UC.

In treating Crohn disease among older adults, systemic corticosteroids are not indicated for maintenance therapy, though they may be used for induction therapy. When possible, nonsystemic corticosteroids should be used, or, if the phenotype prevents their use, early biological therapy. The decision to treat a patient with immunosuppressive drugs should be based on age, functional status, and comorbidities. Immunomodulatory treatments with lower risks for infection and cancer may be safer for patients with late-onset disease. For maintenance of remission, thiopurine monotherapy may be used, with consideration given to its risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers and lymphoma in older patients.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation and history, this is probably a case of Crohn disease. Considering that the age of onset of Crohn disease has a bimodal distribution, this case is representative of late-onset disease. Among patients diagnosed with Crohn disease, the first peak is seen between 15 and 30 years of age, whereas the second peak, occurring in up to 15% of diagnoses, is observed mainly in women between 60 and 70 years of age. A significant proportion of Crohn disease cases are heritable. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing the condition than any other ethnic group.

According to American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be considered in older patients who present with diarrhea, rectal bleeding, urgency, abdominal pain, or weight loss. Fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin measurement may help identify patients who warrant further endoscopic evaluation. Colonoscopy is indicated for patients presenting with chronic diarrhea or hematochezia due to suspected IBD, microscopic colitis, or colorectal neoplasia.

Upon further workup for IBD, signs that suggest Crohn disease rather than ulcerative colitis (UC) are sparing of the rectum; discontinuous involvement with skip areas, deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Antiglycan antibodies are more prevalent in Crohn disease than in ulcerative colitis, but they are not sensitive. Weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are common in Crohn disease but uncommon in UC.

In treating Crohn disease among older adults, systemic corticosteroids are not indicated for maintenance therapy, though they may be used for induction therapy. When possible, nonsystemic corticosteroids should be used, or, if the phenotype prevents their use, early biological therapy. The decision to treat a patient with immunosuppressive drugs should be based on age, functional status, and comorbidities. Immunomodulatory treatments with lower risks for infection and cancer may be safer for patients with late-onset disease. For maintenance of remission, thiopurine monotherapy may be used, with consideration given to its risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers and lymphoma in older patients.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation and history, this is probably a case of Crohn disease. Considering that the age of onset of Crohn disease has a bimodal distribution, this case is representative of late-onset disease. Among patients diagnosed with Crohn disease, the first peak is seen between 15 and 30 years of age, whereas the second peak, occurring in up to 15% of diagnoses, is observed mainly in women between 60 and 70 years of age. A significant proportion of Crohn disease cases are heritable. Patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are at higher risk of developing the condition than any other ethnic group.

According to American Gastroenterological Association guidelines, a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) should be considered in older patients who present with diarrhea, rectal bleeding, urgency, abdominal pain, or weight loss. Fecal calprotectin or lactoferrin measurement may help identify patients who warrant further endoscopic evaluation. Colonoscopy is indicated for patients presenting with chronic diarrhea or hematochezia due to suspected IBD, microscopic colitis, or colorectal neoplasia.

Upon further workup for IBD, signs that suggest Crohn disease rather than ulcerative colitis (UC) are sparing of the rectum; discontinuous involvement with skip areas, deep, linear, or serpiginous ulcers of the colon; strictures; fistulas; or granulomatous inflammation. Antiglycan antibodies are more prevalent in Crohn disease than in ulcerative colitis, but they are not sensitive. Weight loss, perineal disease, fistulae, and obstruction are common in Crohn disease but uncommon in UC.

In treating Crohn disease among older adults, systemic corticosteroids are not indicated for maintenance therapy, though they may be used for induction therapy. When possible, nonsystemic corticosteroids should be used, or, if the phenotype prevents their use, early biological therapy. The decision to treat a patient with immunosuppressive drugs should be based on age, functional status, and comorbidities. Immunomodulatory treatments with lower risks for infection and cancer may be safer for patients with late-onset disease. For maintenance of remission, thiopurine monotherapy may be used, with consideration given to its risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers and lymphoma in older patients.

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, Professor, Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

Bhupinder S. Anand, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 65-year-old woman presents with diarrhea which began several months ago, abdominal pain, and a 10-lb weight loss. Height is 5 ft 3 in and weight is 120 lb (BMI 21.3). The patient notes that she typically does not have a sensitive stomach and is concerned by the onset of symptoms. Current medications are levothyroxine, alendronic acid, and hydrochlorothiazide. Family history is notable for pancreatic cancer on her mother's side; her daughter has celiac disease. She is of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Body temperature is 100.2 °F and hemoglobin level is 12.9 g/dL. Colonoscopy shows ileitis with skip areas. Lab analysis is remarkable for antiglycan antibodies.

Severe ipsilateral headache

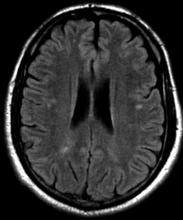

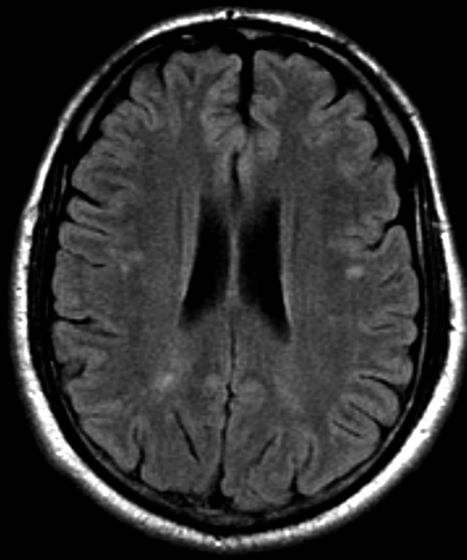

On the basis of the patient's presentation, family history, and personal history of headache, she seems to be presenting with hemiplegic migraine, an uncommon migraine subtype characterized by recurrent headaches associated with temporary unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia. The hemiparesis may resolve before the headache, as seen in the present case, or it may persist for days to weeks. These episodes are sometimes accompanied by ipsilateral numbness, tingling, or paresthesia, with or without a speech disturbance. Visual defects (ie, scintillating scotoma and hemianopia) and aphasia may occur.

Hemiplegic migraine can be sporadic or familial. Familial hemiplegic migraine is the only migraine subtype for which an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance has been identified. The onset is generally in adolescence between 12 and 17 years of age, with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%. Female patients are more likely to have these types of migraines.

Diagnosis of hemiplegic migraine is centered on exclusion of other possible causes of headache with motor weakness. When a patient presents with motor deficit, these symptoms can also be the result of a secondary headache rather than a primary headache disorder. Because of this neurologic aspect of presentation, the differential diagnosis is broad and should span other migraine subtypes, inflammatory or metabolic disorders, and mitochondrial diseases, as well as any condition that shows neurologic deficits without radiologic alterations. Pediatric patients with hemiplegic migraine are often misdiagnosed with epilepsy. Compared with hemiplegic migraine, seizures are much more brief, and any associated hemiparesis is usually characterized by limb jerking, head turning, and loss of consciousness. Of note, up to 7% of patients with familial hemiplegic migraine do eventually develop epilepsy. Although there are no telltale pathognomonic clinical, laboratory, or radiologic findings of hemiplegic migraine, electroencephalography may show asymmetric slow-wave activity contralateral to the hemiparesis.

In hemiplegic migraine, acute treatment options include antiemetics, NSAIDs, and nonnarcotic pain relievers; triptans and ergotamine preparations are contraindicated in this setting because of their potential vasoconstrictive effects. Even if episode frequency is low, the American Headache Society advises that prophylactic treatment should also be considered in the management of uncommon migraine subtypes such as this one.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation, family history, and personal history of headache, she seems to be presenting with hemiplegic migraine, an uncommon migraine subtype characterized by recurrent headaches associated with temporary unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia. The hemiparesis may resolve before the headache, as seen in the present case, or it may persist for days to weeks. These episodes are sometimes accompanied by ipsilateral numbness, tingling, or paresthesia, with or without a speech disturbance. Visual defects (ie, scintillating scotoma and hemianopia) and aphasia may occur.

Hemiplegic migraine can be sporadic or familial. Familial hemiplegic migraine is the only migraine subtype for which an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance has been identified. The onset is generally in adolescence between 12 and 17 years of age, with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%. Female patients are more likely to have these types of migraines.

Diagnosis of hemiplegic migraine is centered on exclusion of other possible causes of headache with motor weakness. When a patient presents with motor deficit, these symptoms can also be the result of a secondary headache rather than a primary headache disorder. Because of this neurologic aspect of presentation, the differential diagnosis is broad and should span other migraine subtypes, inflammatory or metabolic disorders, and mitochondrial diseases, as well as any condition that shows neurologic deficits without radiologic alterations. Pediatric patients with hemiplegic migraine are often misdiagnosed with epilepsy. Compared with hemiplegic migraine, seizures are much more brief, and any associated hemiparesis is usually characterized by limb jerking, head turning, and loss of consciousness. Of note, up to 7% of patients with familial hemiplegic migraine do eventually develop epilepsy. Although there are no telltale pathognomonic clinical, laboratory, or radiologic findings of hemiplegic migraine, electroencephalography may show asymmetric slow-wave activity contralateral to the hemiparesis.

In hemiplegic migraine, acute treatment options include antiemetics, NSAIDs, and nonnarcotic pain relievers; triptans and ergotamine preparations are contraindicated in this setting because of their potential vasoconstrictive effects. Even if episode frequency is low, the American Headache Society advises that prophylactic treatment should also be considered in the management of uncommon migraine subtypes such as this one.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation, family history, and personal history of headache, she seems to be presenting with hemiplegic migraine, an uncommon migraine subtype characterized by recurrent headaches associated with temporary unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia. The hemiparesis may resolve before the headache, as seen in the present case, or it may persist for days to weeks. These episodes are sometimes accompanied by ipsilateral numbness, tingling, or paresthesia, with or without a speech disturbance. Visual defects (ie, scintillating scotoma and hemianopia) and aphasia may occur.

Hemiplegic migraine can be sporadic or familial. Familial hemiplegic migraine is the only migraine subtype for which an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance has been identified. The onset is generally in adolescence between 12 and 17 years of age, with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%. Female patients are more likely to have these types of migraines.

Diagnosis of hemiplegic migraine is centered on exclusion of other possible causes of headache with motor weakness. When a patient presents with motor deficit, these symptoms can also be the result of a secondary headache rather than a primary headache disorder. Because of this neurologic aspect of presentation, the differential diagnosis is broad and should span other migraine subtypes, inflammatory or metabolic disorders, and mitochondrial diseases, as well as any condition that shows neurologic deficits without radiologic alterations. Pediatric patients with hemiplegic migraine are often misdiagnosed with epilepsy. Compared with hemiplegic migraine, seizures are much more brief, and any associated hemiparesis is usually characterized by limb jerking, head turning, and loss of consciousness. Of note, up to 7% of patients with familial hemiplegic migraine do eventually develop epilepsy. Although there are no telltale pathognomonic clinical, laboratory, or radiologic findings of hemiplegic migraine, electroencephalography may show asymmetric slow-wave activity contralateral to the hemiparesis.

In hemiplegic migraine, acute treatment options include antiemetics, NSAIDs, and nonnarcotic pain relievers; triptans and ergotamine preparations are contraindicated in this setting because of their potential vasoconstrictive effects. Even if episode frequency is low, the American Headache Society advises that prophylactic treatment should also be considered in the management of uncommon migraine subtypes such as this one.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 16-year-old female patient presents with a severe ipsilateral headache. She describes that before the onset of head pain, she felt like she could not control her facial muscles on one side, and she was unable to speak in full sentences. She reports that these symptoms probably lasted an hour or so, and she was worried that she was experiencing an allergic reaction, though she reports no known allergies. In terms of family history, the patient explains that she does not have a close relationship with her father, but she recalls that he experienced similar episodes. She notes a history of frequent and recurrent headaches, varying in severity, for which she usually takes a high dose of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Pruritus and pitting edema

The 2020 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) diabetes management in CKD guideline states that most patients with diabetic nephropathy and an eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 benefit from treatment with both metformin and a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, which have been demonstrated to offer substantial benefits in reducing the risks for diabetic nephropathy and cardiovascular disease.

In patients who do not reach individualized targets with metformin and an SGLT2 inhibitor, or who are unable to use these medications, a long-acting glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor antagonist may be used.

Metformin should be administered with caution to patients with CKD because it may increase the risk for lactic acidosis. It is contraindicated in patients with an eGFR < 30, but this patient's eGFR is adequate. Many clinicians might use a lower metformin dosage (1500 mg) as a precaution. Given how high his A1c is, adding a GLP-1 receptor antagonist is probably going to be needed because an SGLT2 inhibitor is only intermediate in terms of glucose reduction.

For control of his hypertension, the American Diabetes Association recommends either an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) as first-line treatment. However, one agent alone is unlikely to control this patient's hypertension. At his level of eGFR, a thiazide diuretic is unlikely to be very effective. Therefore, a loop diuretic should be initiated with the ACE inhibitor or ARB, especially because he has edema.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The 2020 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) diabetes management in CKD guideline states that most patients with diabetic nephropathy and an eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 benefit from treatment with both metformin and a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, which have been demonstrated to offer substantial benefits in reducing the risks for diabetic nephropathy and cardiovascular disease.

In patients who do not reach individualized targets with metformin and an SGLT2 inhibitor, or who are unable to use these medications, a long-acting glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor antagonist may be used.

Metformin should be administered with caution to patients with CKD because it may increase the risk for lactic acidosis. It is contraindicated in patients with an eGFR < 30, but this patient's eGFR is adequate. Many clinicians might use a lower metformin dosage (1500 mg) as a precaution. Given how high his A1c is, adding a GLP-1 receptor antagonist is probably going to be needed because an SGLT2 inhibitor is only intermediate in terms of glucose reduction.

For control of his hypertension, the American Diabetes Association recommends either an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) as first-line treatment. However, one agent alone is unlikely to control this patient's hypertension. At his level of eGFR, a thiazide diuretic is unlikely to be very effective. Therefore, a loop diuretic should be initiated with the ACE inhibitor or ARB, especially because he has edema.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The 2020 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) diabetes management in CKD guideline states that most patients with diabetic nephropathy and an eGFR ≥ 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 benefit from treatment with both metformin and a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, which have been demonstrated to offer substantial benefits in reducing the risks for diabetic nephropathy and cardiovascular disease.

In patients who do not reach individualized targets with metformin and an SGLT2 inhibitor, or who are unable to use these medications, a long-acting glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor antagonist may be used.

Metformin should be administered with caution to patients with CKD because it may increase the risk for lactic acidosis. It is contraindicated in patients with an eGFR < 30, but this patient's eGFR is adequate. Many clinicians might use a lower metformin dosage (1500 mg) as a precaution. Given how high his A1c is, adding a GLP-1 receptor antagonist is probably going to be needed because an SGLT2 inhibitor is only intermediate in terms of glucose reduction.

For control of his hypertension, the American Diabetes Association recommends either an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) as first-line treatment. However, one agent alone is unlikely to control this patient's hypertension. At his level of eGFR, a thiazide diuretic is unlikely to be very effective. Therefore, a loop diuretic should be initiated with the ACE inhibitor or ARB, especially because he has edema.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 47-year-old Black man presents with shortness of breath, pruritus, and pitting edema of the bilateral extremities, which have been present for 6 weeks. He has a 7-year history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, as well as a 30–pack-year history of smoking. His blood pressure is 160/95 mm Hg, heart rate is 97 beats/min (regular rate and rhythm), and respiration is 26 breaths/min. He also has proliferative retinopathy. He is 5 ft 10 in and weighs 220 lb (BMI 31.6). He is taking metformin 2550 mg/d. Other medications include simvastatin 20 mg, amlodipine 10 mg, and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg. He admits to being nonadherent to his medication regimen. A year ago, his estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 66 mL/min/1.73 m2 and he had 1+ proteinuria.

Laboratory tests reveal hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL, creatinine of 3.4 g/dL, eGFR of 32 mL/min/1.73 m2, serum albumin of 3.3 g/dL, A1c of 8.8%, low-density lipoprotein of 143 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein of 43 mg/dL, random glucose of 186 mg/dL, albumin-creatinine ratio of 3250 mg/g, calcium of 8.7 mg/dL, phosphorus of 4.2 mg/dL, plasma parathyroid hormone of 77 pg/mL, and C-reactive protein of 12.

In summary, this patient has normal albumin levels and increased proteinuria with decreased eGFR. His glucose level and A1c are not controlled. In addition, he has anemia, a low serum albumin level, and edema.

This patient has diabetic nephropathy and is at risk for a cardiovascular event because of his eGFR and long history of diabetes, hypertension, tobacco use, and hyperlipidemia. Intervention to control these risk factors should start immediately to prevent progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Urinating multiple times per night

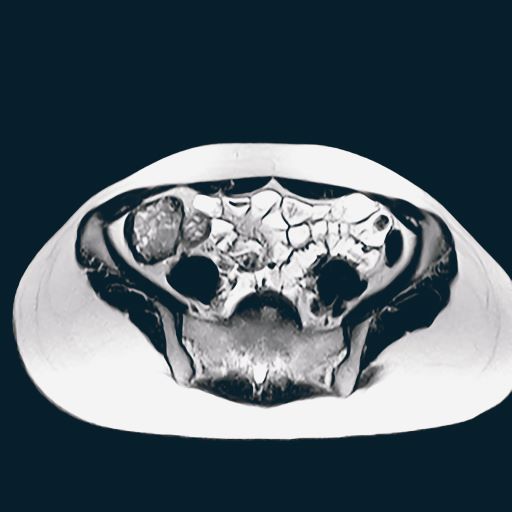

On the basis of the patient's history and presentation, this is likely a case of adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Although most patients with prostate cancer are diagnosed on screening, when localized symptoms do occur, they may include urinary frequency, decreased urine stream, urinary urgency, and hematuria. In some cases, these signs and symptoms may well be related to age-associated prostate enlargement or other conditions; benign prostatic hyperplasia, for example, can manifest in urinary symptoms and even elevate PSA (but because this patient does not report pain, nonbacterial prostatitis is unlikely). Symptomatic patients older than 50 years, such as the one in this case, should be screened for prostate cancer. Those with a PSA > 10 ng/mL are more than 50% likely to have prostate cancer.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines advise that needle biopsy of the prostate is indicated for tissue diagnosis in those with elevated PSA levels, preferably via a transrectal ultrasound. MRI can be used to assess lesions that are concerning for prostate cancer prior to biopsy. Lesions are then assigned Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PI-RADS) scores depending on their location within the prostatic zones. A pathologic evaluation of the biopsy specimen will determine the patient's Gleason score. PSA density and PSA doubling time should be collected as well. The clinician should ask about high-risk germline mutations and estimate life expectancy because course of treatment is largely based on risk assessment.