User login

Primary livedo reticularis of the abdomen

Livedo reticularis can be the manifestation of a wide range of conditions: hematologic and hypercoagulable states, embolic events, connective tissue disease, infection, vasculitis, malignancy, neurologic and endocrine conditions, and medication effects.1 Our patient had no recent history of vascular procedures or peripheral eosinophilia to suggest cholesterol embolization, and he had not recently started taking any new medications. His current medications included aspirin 81 mg, atorvastatin 40 mg, amlodipine 10 mg, and insulin glargine 20 units. Tests for cryoglobulin and antiphospholipid antibodies were negative. There was no evidence of malignancy, and evaluations for infectious and autoimmune diseases were negative.

Biopsy study of a skin lesion showed features consistent with livedo reticularis, with no evidence of vasculitis. The lesions resolved without definitive therapy by hospital day 3. This, in addition to other features of the lesions (eg, uniformity, unbroken reticular segments) and the extensive negative workup for systemic disease, suggested primary livedo reticularis.

CAUSES, TYPES, SUBTYPES

Livedo reticularis results from changes in the cutaneous microvasculature, composed of central arterioles that drain into an interconnecting, netlike venous plexus.1,2 Conditions such as arteriolar deoxygenation and venous plexus venodilation that result in a prominent venous plexus can give rise to clinical livedo reticularis.3

Primary livedo reticularis is thought to occur from spontaneous arteriolar vasospasm. It is a diagnosis of exclusion. An evaluation for underlying disease is important, as livedo reticularis can be associated with the range of conditions listed above.

In our patient, methamphetamine was considered a possible cause, but the findings of livedo reticularis were delayed and persisted longer than expected if they were drug-related.

Livedo racemosa

Distinguishing livedo reticularis from livedo racemosa is important. Livedo racemosa is always secondary and is often associated with antiphospholipid syndrome. It is present in 25% of cases of primary antiphospholipid syndrome and in up to 70% of cases of antiphospholipid syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.5 The reticular pattern of livedo racemosa is permanent and often has irregular and incomplete segments of reticular lattice, with a distribution that is more generalized, involving the trunk or buttocks (or both) in addition to the extremities.3,4 Consequently, a thorough history and physical examination are needed to guide additional workup.

- Gibbs MB, English JC 3rd, Zirwas MJ. Livedo reticularis: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:1009–1019.

- Kraemer M, Linden D, Berlit P. The spectrum of differential diagnosis in neurological patients with livedo reticularis and livedo racemosa. A literature review. J Neurol 2005; 252:1155–1166.

- Uthman IW, Khamashta MA. Livedo racemosa: a striking dermatological sign for the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:2379–2382.

- Dean SM. Livedo reticularis and related disorders. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2011; 13:179–191.

- Chadachan V, Dean SM, Eberhardt RT. Cutaneous changes in peripheral arterial vascular disease. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, Wolff K, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012.

Livedo reticularis can be the manifestation of a wide range of conditions: hematologic and hypercoagulable states, embolic events, connective tissue disease, infection, vasculitis, malignancy, neurologic and endocrine conditions, and medication effects.1 Our patient had no recent history of vascular procedures or peripheral eosinophilia to suggest cholesterol embolization, and he had not recently started taking any new medications. His current medications included aspirin 81 mg, atorvastatin 40 mg, amlodipine 10 mg, and insulin glargine 20 units. Tests for cryoglobulin and antiphospholipid antibodies were negative. There was no evidence of malignancy, and evaluations for infectious and autoimmune diseases were negative.

Biopsy study of a skin lesion showed features consistent with livedo reticularis, with no evidence of vasculitis. The lesions resolved without definitive therapy by hospital day 3. This, in addition to other features of the lesions (eg, uniformity, unbroken reticular segments) and the extensive negative workup for systemic disease, suggested primary livedo reticularis.

CAUSES, TYPES, SUBTYPES

Livedo reticularis results from changes in the cutaneous microvasculature, composed of central arterioles that drain into an interconnecting, netlike venous plexus.1,2 Conditions such as arteriolar deoxygenation and venous plexus venodilation that result in a prominent venous plexus can give rise to clinical livedo reticularis.3

Primary livedo reticularis is thought to occur from spontaneous arteriolar vasospasm. It is a diagnosis of exclusion. An evaluation for underlying disease is important, as livedo reticularis can be associated with the range of conditions listed above.

In our patient, methamphetamine was considered a possible cause, but the findings of livedo reticularis were delayed and persisted longer than expected if they were drug-related.

Livedo racemosa

Distinguishing livedo reticularis from livedo racemosa is important. Livedo racemosa is always secondary and is often associated with antiphospholipid syndrome. It is present in 25% of cases of primary antiphospholipid syndrome and in up to 70% of cases of antiphospholipid syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.5 The reticular pattern of livedo racemosa is permanent and often has irregular and incomplete segments of reticular lattice, with a distribution that is more generalized, involving the trunk or buttocks (or both) in addition to the extremities.3,4 Consequently, a thorough history and physical examination are needed to guide additional workup.

Livedo reticularis can be the manifestation of a wide range of conditions: hematologic and hypercoagulable states, embolic events, connective tissue disease, infection, vasculitis, malignancy, neurologic and endocrine conditions, and medication effects.1 Our patient had no recent history of vascular procedures or peripheral eosinophilia to suggest cholesterol embolization, and he had not recently started taking any new medications. His current medications included aspirin 81 mg, atorvastatin 40 mg, amlodipine 10 mg, and insulin glargine 20 units. Tests for cryoglobulin and antiphospholipid antibodies were negative. There was no evidence of malignancy, and evaluations for infectious and autoimmune diseases were negative.

Biopsy study of a skin lesion showed features consistent with livedo reticularis, with no evidence of vasculitis. The lesions resolved without definitive therapy by hospital day 3. This, in addition to other features of the lesions (eg, uniformity, unbroken reticular segments) and the extensive negative workup for systemic disease, suggested primary livedo reticularis.

CAUSES, TYPES, SUBTYPES

Livedo reticularis results from changes in the cutaneous microvasculature, composed of central arterioles that drain into an interconnecting, netlike venous plexus.1,2 Conditions such as arteriolar deoxygenation and venous plexus venodilation that result in a prominent venous plexus can give rise to clinical livedo reticularis.3

Primary livedo reticularis is thought to occur from spontaneous arteriolar vasospasm. It is a diagnosis of exclusion. An evaluation for underlying disease is important, as livedo reticularis can be associated with the range of conditions listed above.

In our patient, methamphetamine was considered a possible cause, but the findings of livedo reticularis were delayed and persisted longer than expected if they were drug-related.

Livedo racemosa

Distinguishing livedo reticularis from livedo racemosa is important. Livedo racemosa is always secondary and is often associated with antiphospholipid syndrome. It is present in 25% of cases of primary antiphospholipid syndrome and in up to 70% of cases of antiphospholipid syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.5 The reticular pattern of livedo racemosa is permanent and often has irregular and incomplete segments of reticular lattice, with a distribution that is more generalized, involving the trunk or buttocks (or both) in addition to the extremities.3,4 Consequently, a thorough history and physical examination are needed to guide additional workup.

- Gibbs MB, English JC 3rd, Zirwas MJ. Livedo reticularis: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:1009–1019.

- Kraemer M, Linden D, Berlit P. The spectrum of differential diagnosis in neurological patients with livedo reticularis and livedo racemosa. A literature review. J Neurol 2005; 252:1155–1166.

- Uthman IW, Khamashta MA. Livedo racemosa: a striking dermatological sign for the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:2379–2382.

- Dean SM. Livedo reticularis and related disorders. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2011; 13:179–191.

- Chadachan V, Dean SM, Eberhardt RT. Cutaneous changes in peripheral arterial vascular disease. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, Wolff K, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012.

- Gibbs MB, English JC 3rd, Zirwas MJ. Livedo reticularis: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:1009–1019.

- Kraemer M, Linden D, Berlit P. The spectrum of differential diagnosis in neurological patients with livedo reticularis and livedo racemosa. A literature review. J Neurol 2005; 252:1155–1166.

- Uthman IW, Khamashta MA. Livedo racemosa: a striking dermatological sign for the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:2379–2382.

- Dean SM. Livedo reticularis and related disorders. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2011; 13:179–191.

- Chadachan V, Dean SM, Eberhardt RT. Cutaneous changes in peripheral arterial vascular disease. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, Wolff K, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012.

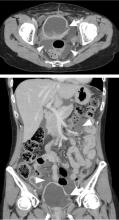

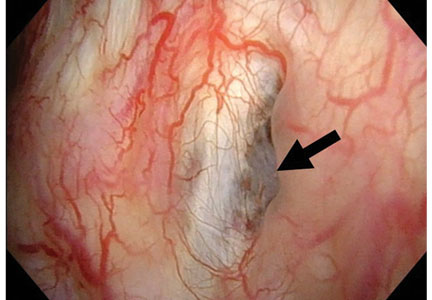

Ascites from intraperitoneal urine leakage after pelvic radiation

A 44-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for the second time in 2 months with acute onset of severe abdominal pain. She had a history of cervical cancer treated with total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy at age 38.

LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF RADIATION ON THE BLADDER

Urinary ascites from intraperitoneal urine leakage is a rare but clinically important sequel to bladder fistula or bladder wall rupture. Fistula or rupture can be caused by pelvic irradiation, blunt trauma, or surgical procedures, but may also be spontaneous.2

When the total radiation dose to the bladder exceeds 60 Gy, radiation cystitis may occur, leading to bladder fistula.3 Effects of radiation on the bladder are usually seen within 2 to 4 years3 but may occur long after the completion of radiation therapy—10 years2 or even 30 to 40 years later.4 Therefore, ascites of unknown origin in a patient with a history of pelvic radiation therapy should lead to an evaluation for late radiation cystitis and urinary ascites from bladder rupture.

- Ramcharan K, Poon-King TM, Indar R. Spontaneous intraperitoneal rupture of a neurogenic bladder; the importance of ascitic fluid urea and electrolytes in diagnosis. Postgrad Med J 1987; 63:999–1000.

- Matsumura M, Ando N, Kumabe A, Dhaliwal G. Pseudo-renal failure: bladder rupture with urinary ascites. BMJ Case Rep 2015; pii:bcr2015212671.

- Shi F, Wang T, Wang J, et al. Peritoneal bladder fistula following radiotherapy for cervical cancer: a case report. Oncol Lett 2016; 12:2008–2010.

- Hayashi W, Nishino T, Namie S, Obata Y, Furukawa M, Kohno S. Spontaneous bladder rupture diagnosis based on urinary appearance of mesothelial cells: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8:46.

A 44-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for the second time in 2 months with acute onset of severe abdominal pain. She had a history of cervical cancer treated with total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy at age 38.

LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF RADIATION ON THE BLADDER

Urinary ascites from intraperitoneal urine leakage is a rare but clinically important sequel to bladder fistula or bladder wall rupture. Fistula or rupture can be caused by pelvic irradiation, blunt trauma, or surgical procedures, but may also be spontaneous.2

When the total radiation dose to the bladder exceeds 60 Gy, radiation cystitis may occur, leading to bladder fistula.3 Effects of radiation on the bladder are usually seen within 2 to 4 years3 but may occur long after the completion of radiation therapy—10 years2 or even 30 to 40 years later.4 Therefore, ascites of unknown origin in a patient with a history of pelvic radiation therapy should lead to an evaluation for late radiation cystitis and urinary ascites from bladder rupture.

A 44-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital for the second time in 2 months with acute onset of severe abdominal pain. She had a history of cervical cancer treated with total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy at age 38.

LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF RADIATION ON THE BLADDER

Urinary ascites from intraperitoneal urine leakage is a rare but clinically important sequel to bladder fistula or bladder wall rupture. Fistula or rupture can be caused by pelvic irradiation, blunt trauma, or surgical procedures, but may also be spontaneous.2

When the total radiation dose to the bladder exceeds 60 Gy, radiation cystitis may occur, leading to bladder fistula.3 Effects of radiation on the bladder are usually seen within 2 to 4 years3 but may occur long after the completion of radiation therapy—10 years2 or even 30 to 40 years later.4 Therefore, ascites of unknown origin in a patient with a history of pelvic radiation therapy should lead to an evaluation for late radiation cystitis and urinary ascites from bladder rupture.

- Ramcharan K, Poon-King TM, Indar R. Spontaneous intraperitoneal rupture of a neurogenic bladder; the importance of ascitic fluid urea and electrolytes in diagnosis. Postgrad Med J 1987; 63:999–1000.

- Matsumura M, Ando N, Kumabe A, Dhaliwal G. Pseudo-renal failure: bladder rupture with urinary ascites. BMJ Case Rep 2015; pii:bcr2015212671.

- Shi F, Wang T, Wang J, et al. Peritoneal bladder fistula following radiotherapy for cervical cancer: a case report. Oncol Lett 2016; 12:2008–2010.

- Hayashi W, Nishino T, Namie S, Obata Y, Furukawa M, Kohno S. Spontaneous bladder rupture diagnosis based on urinary appearance of mesothelial cells: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8:46.

- Ramcharan K, Poon-King TM, Indar R. Spontaneous intraperitoneal rupture of a neurogenic bladder; the importance of ascitic fluid urea and electrolytes in diagnosis. Postgrad Med J 1987; 63:999–1000.

- Matsumura M, Ando N, Kumabe A, Dhaliwal G. Pseudo-renal failure: bladder rupture with urinary ascites. BMJ Case Rep 2015; pii:bcr2015212671.

- Shi F, Wang T, Wang J, et al. Peritoneal bladder fistula following radiotherapy for cervical cancer: a case report. Oncol Lett 2016; 12:2008–2010.

- Hayashi W, Nishino T, Namie S, Obata Y, Furukawa M, Kohno S. Spontaneous bladder rupture diagnosis based on urinary appearance of mesothelial cells: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2014; 8:46.

Methemoglobinemia in an HIV patient

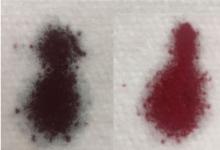

A 45-year-old man with known human immunodeficiency virus infection presented with a 5-day history of dyspnea. When his dyspnea had become symptomatic, he had restarted his home dapsone prophylaxis, but his dyspnea had progressively worsened, and his urine became dark.

Based on these test results, the patient’s dapsone was stopped and replaced with atovaquone. Intravenous infusion of methylene blue was started, with subsequent improvement of the hypoxia and cyanosis (Figure 1). His urine became green, but it returned to a normal color in a matter of hours. He was ultimately diagnosed with P jirovecii pneumonia and completed a course of atovaquone with total resolution of his symptoms.

THE MECHANISMS BEHIND METHEMOGLOBINEMIA

Heme iron is normally in the ferrous state (Fe2+), which allows for hemoglobin to carry oxygen and release it to tissues.1 Exposure to an oxidative stress can lead to methemoglobinemia from an increase in abnormal hemoglobin that contains iron in a ferric state (Fe3+).1,2

Methemoglobin reduces oxygen-carrying capacity in two ways: it is unable to carry oxygen, and its presence shifts the oxygen dissociation curve to the left, causing any remaining normal hemoglobin to be unable to release oxygen to the tissues.1,2

Causes of acquired methemoglobinemia include topical anesthetics (eg, benzocaine, lidocaine) and antibiotics (eg, dapsone).2,3 Signs and symptoms include cyanosis, headache, fatigue, dyspnea, lethargy, respiratory distress, and dark-colored urine.1,2

MANAGEMENT

Treatment consists of intravenous methylene blue, which reduces the hemoglobin from a ferric state to a ferrous state.1–4 Methylene blue is a water-soluble dye excreted primarily in the urine, and common side effects include dizziness, nausea, and green urine.5–7 The blue pigments from methylene blue combine with urobilin (a yellow pigment in the urine), producing a green color.7 This is not pathological and requires no treatment, as the urine returns to normal color after the body fully excretes the dye.5–7

If intravenous methylene blue fails to produce a response, other treatments to consider include hemodialysis, blood transfusion, exchange transfusion, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

- Umbreit J. Methemoglobin—it’s not just blue: a concise review. Am J Hematol 2007; 82:134–144.

- Ash-Bernal R, Wise R, Wright SM. Acquired methemoglobinemia: a retrospective series of 138 cases at 2 teaching hospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004; 83:265–273.

- Coleman MD, Coleman NA. Drug-induced methaemoglobinaemia. Treatment issues. Drug Saf 1996; 14:394–405.

- Sikka P, Bindra VK, Kapoor S, Jain V, Saxena KK. Blue cures blue but be cautious. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2011; 3:543–545.

- Stratta P, Barbe MC. Images in clinical medicine. Green urine. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:e12.

- Miri-Aliabad G. Green urine secondary to methylene blue. Indian J Pediatr 2014; 81:1255–1256.

- Prakash S, Saini S, Mullick P, Pawar M. Green urine: a cause for concern? J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2017; 33:128–130.

A 45-year-old man with known human immunodeficiency virus infection presented with a 5-day history of dyspnea. When his dyspnea had become symptomatic, he had restarted his home dapsone prophylaxis, but his dyspnea had progressively worsened, and his urine became dark.

Based on these test results, the patient’s dapsone was stopped and replaced with atovaquone. Intravenous infusion of methylene blue was started, with subsequent improvement of the hypoxia and cyanosis (Figure 1). His urine became green, but it returned to a normal color in a matter of hours. He was ultimately diagnosed with P jirovecii pneumonia and completed a course of atovaquone with total resolution of his symptoms.

THE MECHANISMS BEHIND METHEMOGLOBINEMIA

Heme iron is normally in the ferrous state (Fe2+), which allows for hemoglobin to carry oxygen and release it to tissues.1 Exposure to an oxidative stress can lead to methemoglobinemia from an increase in abnormal hemoglobin that contains iron in a ferric state (Fe3+).1,2

Methemoglobin reduces oxygen-carrying capacity in two ways: it is unable to carry oxygen, and its presence shifts the oxygen dissociation curve to the left, causing any remaining normal hemoglobin to be unable to release oxygen to the tissues.1,2

Causes of acquired methemoglobinemia include topical anesthetics (eg, benzocaine, lidocaine) and antibiotics (eg, dapsone).2,3 Signs and symptoms include cyanosis, headache, fatigue, dyspnea, lethargy, respiratory distress, and dark-colored urine.1,2

MANAGEMENT

Treatment consists of intravenous methylene blue, which reduces the hemoglobin from a ferric state to a ferrous state.1–4 Methylene blue is a water-soluble dye excreted primarily in the urine, and common side effects include dizziness, nausea, and green urine.5–7 The blue pigments from methylene blue combine with urobilin (a yellow pigment in the urine), producing a green color.7 This is not pathological and requires no treatment, as the urine returns to normal color after the body fully excretes the dye.5–7

If intravenous methylene blue fails to produce a response, other treatments to consider include hemodialysis, blood transfusion, exchange transfusion, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

A 45-year-old man with known human immunodeficiency virus infection presented with a 5-day history of dyspnea. When his dyspnea had become symptomatic, he had restarted his home dapsone prophylaxis, but his dyspnea had progressively worsened, and his urine became dark.

Based on these test results, the patient’s dapsone was stopped and replaced with atovaquone. Intravenous infusion of methylene blue was started, with subsequent improvement of the hypoxia and cyanosis (Figure 1). His urine became green, but it returned to a normal color in a matter of hours. He was ultimately diagnosed with P jirovecii pneumonia and completed a course of atovaquone with total resolution of his symptoms.

THE MECHANISMS BEHIND METHEMOGLOBINEMIA

Heme iron is normally in the ferrous state (Fe2+), which allows for hemoglobin to carry oxygen and release it to tissues.1 Exposure to an oxidative stress can lead to methemoglobinemia from an increase in abnormal hemoglobin that contains iron in a ferric state (Fe3+).1,2

Methemoglobin reduces oxygen-carrying capacity in two ways: it is unable to carry oxygen, and its presence shifts the oxygen dissociation curve to the left, causing any remaining normal hemoglobin to be unable to release oxygen to the tissues.1,2

Causes of acquired methemoglobinemia include topical anesthetics (eg, benzocaine, lidocaine) and antibiotics (eg, dapsone).2,3 Signs and symptoms include cyanosis, headache, fatigue, dyspnea, lethargy, respiratory distress, and dark-colored urine.1,2

MANAGEMENT

Treatment consists of intravenous methylene blue, which reduces the hemoglobin from a ferric state to a ferrous state.1–4 Methylene blue is a water-soluble dye excreted primarily in the urine, and common side effects include dizziness, nausea, and green urine.5–7 The blue pigments from methylene blue combine with urobilin (a yellow pigment in the urine), producing a green color.7 This is not pathological and requires no treatment, as the urine returns to normal color after the body fully excretes the dye.5–7

If intravenous methylene blue fails to produce a response, other treatments to consider include hemodialysis, blood transfusion, exchange transfusion, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

- Umbreit J. Methemoglobin—it’s not just blue: a concise review. Am J Hematol 2007; 82:134–144.

- Ash-Bernal R, Wise R, Wright SM. Acquired methemoglobinemia: a retrospective series of 138 cases at 2 teaching hospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004; 83:265–273.

- Coleman MD, Coleman NA. Drug-induced methaemoglobinaemia. Treatment issues. Drug Saf 1996; 14:394–405.

- Sikka P, Bindra VK, Kapoor S, Jain V, Saxena KK. Blue cures blue but be cautious. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2011; 3:543–545.

- Stratta P, Barbe MC. Images in clinical medicine. Green urine. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:e12.

- Miri-Aliabad G. Green urine secondary to methylene blue. Indian J Pediatr 2014; 81:1255–1256.

- Prakash S, Saini S, Mullick P, Pawar M. Green urine: a cause for concern? J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2017; 33:128–130.

- Umbreit J. Methemoglobin—it’s not just blue: a concise review. Am J Hematol 2007; 82:134–144.

- Ash-Bernal R, Wise R, Wright SM. Acquired methemoglobinemia: a retrospective series of 138 cases at 2 teaching hospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 2004; 83:265–273.

- Coleman MD, Coleman NA. Drug-induced methaemoglobinaemia. Treatment issues. Drug Saf 1996; 14:394–405.

- Sikka P, Bindra VK, Kapoor S, Jain V, Saxena KK. Blue cures blue but be cautious. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2011; 3:543–545.

- Stratta P, Barbe MC. Images in clinical medicine. Green urine. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:e12.

- Miri-Aliabad G. Green urine secondary to methylene blue. Indian J Pediatr 2014; 81:1255–1256.

- Prakash S, Saini S, Mullick P, Pawar M. Green urine: a cause for concern? J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2017; 33:128–130.

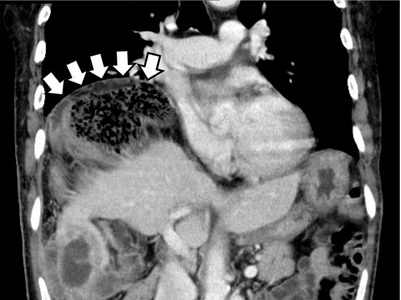

Gas under the right diaphragm

A 66-year-old man presented to the hospital with 3 days of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. He had come to the emergency department several times during this period, but the cause of his symptoms had not been determined.

The patient was successfully treated with urgent right hemicolectomy.

THE CHILAIDITI SIGN AND SYNDROME

The Chilaiditi sign is an infrequent anomaly found incidentally on chest or abdominal radiography as a colonic interposition between the liver and right hemidiaphragm.1 It is often asymptomatic but is sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and constipation, ie, Chilaiditi syndrome.

Generally, after conservative treatment with fasting and pain control, symptoms may subside and follow-up should be sufficient. However, nasogastric decompression and laxatives are occasionally needed and are often effective in patients with Chilaiditi syndrome. Urgent abdominal surgery is indicated for patients with symptoms of volvulus of the colon, stomach, or small intestine.2

DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS

The Chilaiditi sign is often confused with pneumoperitoneum, which usually requires urgent abdominal surgery. But the presence of haustration or valvulae conniventes (folds in the small bowel mucosa) in the hepatodiaphragmatic space helps distinguish between intraluminal gas and free air. If the patient presents with abdominal pain without signs of peritonitis, and if imaging indicates the Chilaiditi sign, then supplementary imaging (eg, decubitus radiography, chest CT, abdominal CT) is recommended to make the definitive diagnosis and to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Gas under the diaphragm on standing chest radiography without signs of peritonitis may also be seen after laparotomy and after scuba diving as well as in cases of biliary enteric fistula, incompetent sphincter of Oddi, gallstone ileus, and pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. The incidence rate of the Chilaiditi sign detected by radiography is between 0.025% and 0.28%.3

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

The cause of the Chilaiditi sign remains unknown. Predisposing factors can be categorized as diaphragmatic (diaphragmatic thinning, phrenic nerve injury, expanded thoracic cavity), intestinal (megacolon, increased intra-abdominal pressure), and hepatic (hepatic atrophy, cirrhosis, ascites).

In healthy people, Chilaiditi syndrome is usually attributed to a congenital abnormal lengthening of the colon or to undue looseness of ligaments of the colon and liver.

Recognizing the Chilaiditi sign is particularly important in patients scheduled to undergo a percutaneous transhepatic procedure or colonoscopic examination, as these procedures increase the risk of perforation.

- Chilaiditi D. Zur Frage der Hepatoptose und Ptose im allegemeinen im Anschluss an drei Fälle von temporärer, partieller Leberverlagerung. Fortschritte auf dem Gebiete der Röntgenstrahlen 1910; 16:173–208.

- Williams A, Cox R, Palaniappan B, Woodward A. Chilaiditi’s syndrome associated with colonic volvulus and intestinal malrotation—a rare case. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014; 5:335–338.

- Orangio GR, Fazio VW, Winkelman E, McGonagle BA. The Chilaiditi syndrome and associated volvulus of the transverse colon. An indication for surgical therapy. Dis Colon Rectum 1986; 29:653-656.

A 66-year-old man presented to the hospital with 3 days of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. He had come to the emergency department several times during this period, but the cause of his symptoms had not been determined.

The patient was successfully treated with urgent right hemicolectomy.

THE CHILAIDITI SIGN AND SYNDROME

The Chilaiditi sign is an infrequent anomaly found incidentally on chest or abdominal radiography as a colonic interposition between the liver and right hemidiaphragm.1 It is often asymptomatic but is sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and constipation, ie, Chilaiditi syndrome.

Generally, after conservative treatment with fasting and pain control, symptoms may subside and follow-up should be sufficient. However, nasogastric decompression and laxatives are occasionally needed and are often effective in patients with Chilaiditi syndrome. Urgent abdominal surgery is indicated for patients with symptoms of volvulus of the colon, stomach, or small intestine.2

DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS

The Chilaiditi sign is often confused with pneumoperitoneum, which usually requires urgent abdominal surgery. But the presence of haustration or valvulae conniventes (folds in the small bowel mucosa) in the hepatodiaphragmatic space helps distinguish between intraluminal gas and free air. If the patient presents with abdominal pain without signs of peritonitis, and if imaging indicates the Chilaiditi sign, then supplementary imaging (eg, decubitus radiography, chest CT, abdominal CT) is recommended to make the definitive diagnosis and to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Gas under the diaphragm on standing chest radiography without signs of peritonitis may also be seen after laparotomy and after scuba diving as well as in cases of biliary enteric fistula, incompetent sphincter of Oddi, gallstone ileus, and pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. The incidence rate of the Chilaiditi sign detected by radiography is between 0.025% and 0.28%.3

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

The cause of the Chilaiditi sign remains unknown. Predisposing factors can be categorized as diaphragmatic (diaphragmatic thinning, phrenic nerve injury, expanded thoracic cavity), intestinal (megacolon, increased intra-abdominal pressure), and hepatic (hepatic atrophy, cirrhosis, ascites).

In healthy people, Chilaiditi syndrome is usually attributed to a congenital abnormal lengthening of the colon or to undue looseness of ligaments of the colon and liver.

Recognizing the Chilaiditi sign is particularly important in patients scheduled to undergo a percutaneous transhepatic procedure or colonoscopic examination, as these procedures increase the risk of perforation.

A 66-year-old man presented to the hospital with 3 days of nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. He had come to the emergency department several times during this period, but the cause of his symptoms had not been determined.

The patient was successfully treated with urgent right hemicolectomy.

THE CHILAIDITI SIGN AND SYNDROME

The Chilaiditi sign is an infrequent anomaly found incidentally on chest or abdominal radiography as a colonic interposition between the liver and right hemidiaphragm.1 It is often asymptomatic but is sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and constipation, ie, Chilaiditi syndrome.

Generally, after conservative treatment with fasting and pain control, symptoms may subside and follow-up should be sufficient. However, nasogastric decompression and laxatives are occasionally needed and are often effective in patients with Chilaiditi syndrome. Urgent abdominal surgery is indicated for patients with symptoms of volvulus of the colon, stomach, or small intestine.2

DISTINGUISHING CHARACTERISTICS

The Chilaiditi sign is often confused with pneumoperitoneum, which usually requires urgent abdominal surgery. But the presence of haustration or valvulae conniventes (folds in the small bowel mucosa) in the hepatodiaphragmatic space helps distinguish between intraluminal gas and free air. If the patient presents with abdominal pain without signs of peritonitis, and if imaging indicates the Chilaiditi sign, then supplementary imaging (eg, decubitus radiography, chest CT, abdominal CT) is recommended to make the definitive diagnosis and to avoid unnecessary surgery.

Gas under the diaphragm on standing chest radiography without signs of peritonitis may also be seen after laparotomy and after scuba diving as well as in cases of biliary enteric fistula, incompetent sphincter of Oddi, gallstone ileus, and pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis. The incidence rate of the Chilaiditi sign detected by radiography is between 0.025% and 0.28%.3

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

The cause of the Chilaiditi sign remains unknown. Predisposing factors can be categorized as diaphragmatic (diaphragmatic thinning, phrenic nerve injury, expanded thoracic cavity), intestinal (megacolon, increased intra-abdominal pressure), and hepatic (hepatic atrophy, cirrhosis, ascites).

In healthy people, Chilaiditi syndrome is usually attributed to a congenital abnormal lengthening of the colon or to undue looseness of ligaments of the colon and liver.

Recognizing the Chilaiditi sign is particularly important in patients scheduled to undergo a percutaneous transhepatic procedure or colonoscopic examination, as these procedures increase the risk of perforation.

- Chilaiditi D. Zur Frage der Hepatoptose und Ptose im allegemeinen im Anschluss an drei Fälle von temporärer, partieller Leberverlagerung. Fortschritte auf dem Gebiete der Röntgenstrahlen 1910; 16:173–208.

- Williams A, Cox R, Palaniappan B, Woodward A. Chilaiditi’s syndrome associated with colonic volvulus and intestinal malrotation—a rare case. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014; 5:335–338.

- Orangio GR, Fazio VW, Winkelman E, McGonagle BA. The Chilaiditi syndrome and associated volvulus of the transverse colon. An indication for surgical therapy. Dis Colon Rectum 1986; 29:653-656.

- Chilaiditi D. Zur Frage der Hepatoptose und Ptose im allegemeinen im Anschluss an drei Fälle von temporärer, partieller Leberverlagerung. Fortschritte auf dem Gebiete der Röntgenstrahlen 1910; 16:173–208.

- Williams A, Cox R, Palaniappan B, Woodward A. Chilaiditi’s syndrome associated with colonic volvulus and intestinal malrotation—a rare case. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014; 5:335–338.

- Orangio GR, Fazio VW, Winkelman E, McGonagle BA. The Chilaiditi syndrome and associated volvulus of the transverse colon. An indication for surgical therapy. Dis Colon Rectum 1986; 29:653-656.

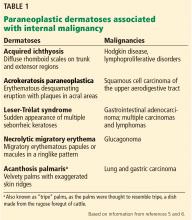

Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome

A 66-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with pain and bluish discoloration of her left great toe for the past 2 days. She had no history of trauma to the toe or of peripheral vascular disease. She also complained of intermittent abdominal pain for the last 5 months and unintentional weight loss of 8 pounds.

Vascular disease was suspected, and the patient was started on systemic anticoagulation. However, chest computed tomography (CT) and conventional angiography showed no aortic disease; vessels were of normal caliber, and no distal filling defects were noted.

A routine evaluation with complete blood cell count, peripheral smear, renal function testing, and urinalysis with eosinophil smear was also unrevealing. An extensive investigation followed, including serum complement testing, assays for antinuclear, antineutrophil cytoplasmic, and anti-Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, cryoglobulin testing, and hepatitis B and C virus serology, as well as screening for syphilis and lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, and beta-2 glycoprotein antibodies. The results for all these tests were also unremarkable.

Results of coagulation testing and venous duplex ultrasonography of the legs were normal, and electrocardiography and echocardiography showed no signs of valvular vegetation, myxoma, or patent foramen ovale.

Given our patient’s age, abdominal pain, and weight loss but negative vascular evaluation, we considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome. Abdominal CT revealed a tumor of the pancreatic head with multiple liver lesions, and cytologic study confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

DISTANT MARKERS OF MALIGNANCY

Causes of blue toe syndrome to consider in the differential diagnosis include arterial thromboembolism, vasoconstrictive drug use or disorders, vasculitis, and venous thrombosis.1 These are common and deserve prompt investigation. However, if they are ruled out, a peripheral acral vascular syndrome should be considered. These syndromes present as Raynaud phenomenon, gangrene, or acrocyanosis of the fingers or toes with underlying neoplasia. Unusual features such as sudden onset in a patient over age 50, an acral distribution, and associated symptoms such as unrelated pain and weight loss should spark concern for underlying malignancy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are defined as signs and symptoms that present distant from the site of malignancy. Dermatoses as markers of internal malignancy are well-established but perplexing clinical entities whose exact causes remain unknown.2

Paraneoplastic dermatoses are well recognized as harbingers of metastatic disease.5,6 Our patient’s story demonstrates need for a thorough diagnostic investigation.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60:1–20.

- Naschitz JE, Rosner I, Rozenbaum M, Zuckerman E, Yeshurun D. Rheumatic syndromes: clues to occult neoplasia. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1999; 29:43–55.

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, Orcel B, Emmerich J, Dubertret L. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47:47–52.

- DeCross AJ, Sahasrabudhe DM. Paraneoplastic Raynaud's phenomenon. Am J Med 1992; 92:571–572.

- Ramos-E-Silva M, Carvalho JC, Carneiro SC. Cutaneous paraneoplasia. Clin Dermatol 2011; 29:541–547.

- Chung VQ, Moschella SL, Zembowicz A, Liu V. Clinical and pathologic findings of paraneoplastic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54:745–762.

A 66-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with pain and bluish discoloration of her left great toe for the past 2 days. She had no history of trauma to the toe or of peripheral vascular disease. She also complained of intermittent abdominal pain for the last 5 months and unintentional weight loss of 8 pounds.

Vascular disease was suspected, and the patient was started on systemic anticoagulation. However, chest computed tomography (CT) and conventional angiography showed no aortic disease; vessels were of normal caliber, and no distal filling defects were noted.

A routine evaluation with complete blood cell count, peripheral smear, renal function testing, and urinalysis with eosinophil smear was also unrevealing. An extensive investigation followed, including serum complement testing, assays for antinuclear, antineutrophil cytoplasmic, and anti-Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, cryoglobulin testing, and hepatitis B and C virus serology, as well as screening for syphilis and lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, and beta-2 glycoprotein antibodies. The results for all these tests were also unremarkable.

Results of coagulation testing and venous duplex ultrasonography of the legs were normal, and electrocardiography and echocardiography showed no signs of valvular vegetation, myxoma, or patent foramen ovale.

Given our patient’s age, abdominal pain, and weight loss but negative vascular evaluation, we considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome. Abdominal CT revealed a tumor of the pancreatic head with multiple liver lesions, and cytologic study confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

DISTANT MARKERS OF MALIGNANCY

Causes of blue toe syndrome to consider in the differential diagnosis include arterial thromboembolism, vasoconstrictive drug use or disorders, vasculitis, and venous thrombosis.1 These are common and deserve prompt investigation. However, if they are ruled out, a peripheral acral vascular syndrome should be considered. These syndromes present as Raynaud phenomenon, gangrene, or acrocyanosis of the fingers or toes with underlying neoplasia. Unusual features such as sudden onset in a patient over age 50, an acral distribution, and associated symptoms such as unrelated pain and weight loss should spark concern for underlying malignancy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are defined as signs and symptoms that present distant from the site of malignancy. Dermatoses as markers of internal malignancy are well-established but perplexing clinical entities whose exact causes remain unknown.2

Paraneoplastic dermatoses are well recognized as harbingers of metastatic disease.5,6 Our patient’s story demonstrates need for a thorough diagnostic investigation.

A 66-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with pain and bluish discoloration of her left great toe for the past 2 days. She had no history of trauma to the toe or of peripheral vascular disease. She also complained of intermittent abdominal pain for the last 5 months and unintentional weight loss of 8 pounds.

Vascular disease was suspected, and the patient was started on systemic anticoagulation. However, chest computed tomography (CT) and conventional angiography showed no aortic disease; vessels were of normal caliber, and no distal filling defects were noted.

A routine evaluation with complete blood cell count, peripheral smear, renal function testing, and urinalysis with eosinophil smear was also unrevealing. An extensive investigation followed, including serum complement testing, assays for antinuclear, antineutrophil cytoplasmic, and anti-Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, cryoglobulin testing, and hepatitis B and C virus serology, as well as screening for syphilis and lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, and beta-2 glycoprotein antibodies. The results for all these tests were also unremarkable.

Results of coagulation testing and venous duplex ultrasonography of the legs were normal, and electrocardiography and echocardiography showed no signs of valvular vegetation, myxoma, or patent foramen ovale.

Given our patient’s age, abdominal pain, and weight loss but negative vascular evaluation, we considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome. Abdominal CT revealed a tumor of the pancreatic head with multiple liver lesions, and cytologic study confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

DISTANT MARKERS OF MALIGNANCY

Causes of blue toe syndrome to consider in the differential diagnosis include arterial thromboembolism, vasoconstrictive drug use or disorders, vasculitis, and venous thrombosis.1 These are common and deserve prompt investigation. However, if they are ruled out, a peripheral acral vascular syndrome should be considered. These syndromes present as Raynaud phenomenon, gangrene, or acrocyanosis of the fingers or toes with underlying neoplasia. Unusual features such as sudden onset in a patient over age 50, an acral distribution, and associated symptoms such as unrelated pain and weight loss should spark concern for underlying malignancy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are defined as signs and symptoms that present distant from the site of malignancy. Dermatoses as markers of internal malignancy are well-established but perplexing clinical entities whose exact causes remain unknown.2

Paraneoplastic dermatoses are well recognized as harbingers of metastatic disease.5,6 Our patient’s story demonstrates need for a thorough diagnostic investigation.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60:1–20.

- Naschitz JE, Rosner I, Rozenbaum M, Zuckerman E, Yeshurun D. Rheumatic syndromes: clues to occult neoplasia. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1999; 29:43–55.

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, Orcel B, Emmerich J, Dubertret L. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47:47–52.

- DeCross AJ, Sahasrabudhe DM. Paraneoplastic Raynaud's phenomenon. Am J Med 1992; 92:571–572.

- Ramos-E-Silva M, Carvalho JC, Carneiro SC. Cutaneous paraneoplasia. Clin Dermatol 2011; 29:541–547.

- Chung VQ, Moschella SL, Zembowicz A, Liu V. Clinical and pathologic findings of paraneoplastic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54:745–762.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60:1–20.

- Naschitz JE, Rosner I, Rozenbaum M, Zuckerman E, Yeshurun D. Rheumatic syndromes: clues to occult neoplasia. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1999; 29:43–55.

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, Orcel B, Emmerich J, Dubertret L. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47:47–52.

- DeCross AJ, Sahasrabudhe DM. Paraneoplastic Raynaud's phenomenon. Am J Med 1992; 92:571–572.

- Ramos-E-Silva M, Carvalho JC, Carneiro SC. Cutaneous paraneoplasia. Clin Dermatol 2011; 29:541–547.

- Chung VQ, Moschella SL, Zembowicz A, Liu V. Clinical and pathologic findings of paraneoplastic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54:745–762.

Erythema ab igne

A 42-year-old man presented to his primary care physician with chief complaints of fatigue and worsening of severe chronic thoracic and lumbar back pain that he attributed to routine daily activity at his job, not to any specific antecedent trauma. Over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and analgesics had provided moderate pain relief. A heating pad, which he had been using daily, often for several hours at a time, offered significant pain relief.

AN UNCOMMON CAUSE OF HYPERPIGMENTATION

Erythema ab igne is an uncommon thermally induced eruption associated with periods of repeated exposure of the skin to warm stimuli. It has been reported after holding a kerosene stove between the knees1 and after balancing a laptop computer on the thighs,2 but hot water bottles and heating pads3 are the most commonly reported causes.

Clinical findings and a compatible history are critical to the diagnosis. The involved area should have a history of heat exposure, followed by the development of asymptomatic persistent erythema and, in long-standing cases, hyperpigmentation in a distinct reticulate (netlike) distribution. Telangiectasias and atrophy may occur in advanced disease. In extreme presentations, bullae may develop.4

OTHER POTENTIAL CAUSES

Based on the history and findings on physical examination, conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis can include reticular eruptions such as livedo reticularis (associated with cold temperature changes), hypercoagulable states (antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, Sneddon syndrome), and connective tissue diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus).

Other causes of hyperpigmentation such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (associated with a prior eruption) and stasis dermatitis (found in areas of poor venous drainage) may also be considered.

The frequent application of an external agent such as a drug or lotion, or even the use of a heating pad if it is made from rubber or is finished with an allergenic dye, raises the possibility of allergic contact dermatitis, but this was not likely in our patient because of the lack of pruritus and active dermatitis. Repeated application of a stimulus such as a heating pad with frequent rubbing can also precipitate lichen simplex chronicus, with thickened, hyperkeratotic skin. Another cause of hyperpigmentation on the back is notalgia paresthetica, which is typically unilateral, over the shoulder blades, and is associated with pain, pruritus, or other neurologic symptoms. Again, these were not present in our patient.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

The first-line treatment for erythema ab igne is to stop exposure to the offending heat source. The hyperpigmentation may slowly fade over several years. Cosmetic treatments such as laser therapy and depigmenting creams can be tried for persistent hyperpigmentation. Patients may be monitored for the small increased risk of cutaneous malignancies—particularly squamous cell carcinoma—arising within regions of erythema ab igne, particularly if atrophic or nonhealing in nature.

Clinicians should recognize the differential diagnosis of erythema ab igne in the appropriate clinical setting and provide the patient counseling regarding this preventable dermatosis.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics 2010; 126:e1227–e1230.

- Milgrom Y, Sabag T, Zlotogorski A, Heyman SN. Erythema ab igne of shins: a kerosene stove-induced prototype in diabetics. J Postgrad Med 2013; 59:56–57.

- Waldorf DS, Rast MF, Garofalo VJ. Heating-pad erythematous dermatitis ‘erythema ab igne.’ JAMA 1971; 218:1704.

- Asilian A, Abtahi-Naeini B, Pourazizi M, Rakhshanpour M. Rapid onset of bullous erythema ab igne: a case report of atypical presentation. Indian J Dermatol 2015; 60:325.

A 42-year-old man presented to his primary care physician with chief complaints of fatigue and worsening of severe chronic thoracic and lumbar back pain that he attributed to routine daily activity at his job, not to any specific antecedent trauma. Over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and analgesics had provided moderate pain relief. A heating pad, which he had been using daily, often for several hours at a time, offered significant pain relief.

AN UNCOMMON CAUSE OF HYPERPIGMENTATION

Erythema ab igne is an uncommon thermally induced eruption associated with periods of repeated exposure of the skin to warm stimuli. It has been reported after holding a kerosene stove between the knees1 and after balancing a laptop computer on the thighs,2 but hot water bottles and heating pads3 are the most commonly reported causes.

Clinical findings and a compatible history are critical to the diagnosis. The involved area should have a history of heat exposure, followed by the development of asymptomatic persistent erythema and, in long-standing cases, hyperpigmentation in a distinct reticulate (netlike) distribution. Telangiectasias and atrophy may occur in advanced disease. In extreme presentations, bullae may develop.4

OTHER POTENTIAL CAUSES

Based on the history and findings on physical examination, conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis can include reticular eruptions such as livedo reticularis (associated with cold temperature changes), hypercoagulable states (antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, Sneddon syndrome), and connective tissue diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus).

Other causes of hyperpigmentation such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (associated with a prior eruption) and stasis dermatitis (found in areas of poor venous drainage) may also be considered.

The frequent application of an external agent such as a drug or lotion, or even the use of a heating pad if it is made from rubber or is finished with an allergenic dye, raises the possibility of allergic contact dermatitis, but this was not likely in our patient because of the lack of pruritus and active dermatitis. Repeated application of a stimulus such as a heating pad with frequent rubbing can also precipitate lichen simplex chronicus, with thickened, hyperkeratotic skin. Another cause of hyperpigmentation on the back is notalgia paresthetica, which is typically unilateral, over the shoulder blades, and is associated with pain, pruritus, or other neurologic symptoms. Again, these were not present in our patient.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

The first-line treatment for erythema ab igne is to stop exposure to the offending heat source. The hyperpigmentation may slowly fade over several years. Cosmetic treatments such as laser therapy and depigmenting creams can be tried for persistent hyperpigmentation. Patients may be monitored for the small increased risk of cutaneous malignancies—particularly squamous cell carcinoma—arising within regions of erythema ab igne, particularly if atrophic or nonhealing in nature.

Clinicians should recognize the differential diagnosis of erythema ab igne in the appropriate clinical setting and provide the patient counseling regarding this preventable dermatosis.

A 42-year-old man presented to his primary care physician with chief complaints of fatigue and worsening of severe chronic thoracic and lumbar back pain that he attributed to routine daily activity at his job, not to any specific antecedent trauma. Over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and analgesics had provided moderate pain relief. A heating pad, which he had been using daily, often for several hours at a time, offered significant pain relief.

AN UNCOMMON CAUSE OF HYPERPIGMENTATION

Erythema ab igne is an uncommon thermally induced eruption associated with periods of repeated exposure of the skin to warm stimuli. It has been reported after holding a kerosene stove between the knees1 and after balancing a laptop computer on the thighs,2 but hot water bottles and heating pads3 are the most commonly reported causes.

Clinical findings and a compatible history are critical to the diagnosis. The involved area should have a history of heat exposure, followed by the development of asymptomatic persistent erythema and, in long-standing cases, hyperpigmentation in a distinct reticulate (netlike) distribution. Telangiectasias and atrophy may occur in advanced disease. In extreme presentations, bullae may develop.4

OTHER POTENTIAL CAUSES

Based on the history and findings on physical examination, conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis can include reticular eruptions such as livedo reticularis (associated with cold temperature changes), hypercoagulable states (antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, Sneddon syndrome), and connective tissue diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus).

Other causes of hyperpigmentation such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (associated with a prior eruption) and stasis dermatitis (found in areas of poor venous drainage) may also be considered.

The frequent application of an external agent such as a drug or lotion, or even the use of a heating pad if it is made from rubber or is finished with an allergenic dye, raises the possibility of allergic contact dermatitis, but this was not likely in our patient because of the lack of pruritus and active dermatitis. Repeated application of a stimulus such as a heating pad with frequent rubbing can also precipitate lichen simplex chronicus, with thickened, hyperkeratotic skin. Another cause of hyperpigmentation on the back is notalgia paresthetica, which is typically unilateral, over the shoulder blades, and is associated with pain, pruritus, or other neurologic symptoms. Again, these were not present in our patient.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

The first-line treatment for erythema ab igne is to stop exposure to the offending heat source. The hyperpigmentation may slowly fade over several years. Cosmetic treatments such as laser therapy and depigmenting creams can be tried for persistent hyperpigmentation. Patients may be monitored for the small increased risk of cutaneous malignancies—particularly squamous cell carcinoma—arising within regions of erythema ab igne, particularly if atrophic or nonhealing in nature.

Clinicians should recognize the differential diagnosis of erythema ab igne in the appropriate clinical setting and provide the patient counseling regarding this preventable dermatosis.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics 2010; 126:e1227–e1230.

- Milgrom Y, Sabag T, Zlotogorski A, Heyman SN. Erythema ab igne of shins: a kerosene stove-induced prototype in diabetics. J Postgrad Med 2013; 59:56–57.

- Waldorf DS, Rast MF, Garofalo VJ. Heating-pad erythematous dermatitis ‘erythema ab igne.’ JAMA 1971; 218:1704.

- Asilian A, Abtahi-Naeini B, Pourazizi M, Rakhshanpour M. Rapid onset of bullous erythema ab igne: a case report of atypical presentation. Indian J Dermatol 2015; 60:325.

- Arnold AW, Itin PH. Laptop computer-induced erythema ab igne in a child and review of the literature. Pediatrics 2010; 126:e1227–e1230.

- Milgrom Y, Sabag T, Zlotogorski A, Heyman SN. Erythema ab igne of shins: a kerosene stove-induced prototype in diabetics. J Postgrad Med 2013; 59:56–57.

- Waldorf DS, Rast MF, Garofalo VJ. Heating-pad erythematous dermatitis ‘erythema ab igne.’ JAMA 1971; 218:1704.

- Asilian A, Abtahi-Naeini B, Pourazizi M, Rakhshanpour M. Rapid onset of bullous erythema ab igne: a case report of atypical presentation. Indian J Dermatol 2015; 60:325.

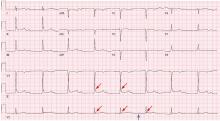

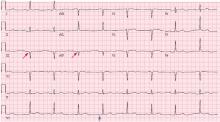

Hypothermia and severe first-degree heart block

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.