User login

A Smoky Dilemma

A 23-year-old woman presented to the emergency department complaining of “feeling terrible” for the past week. She described subjective fevers, chills, nonproductive cough, myalgias, and nausea. Her symptoms worsened on the day of presentation, with drenching night sweats, worsening myalgias, and generalized fatigue. She was unable to tolerate oral intake due to persistent nausea and had one episode of emesis.

While the initial constellation of symptoms suggests a viral syndrome, its progression over a week raises concern for something more ominous. Of her relatively nonspecific symptoms, prominent myalgias accompanied by a febrile illness may be most helpful. Fever, myalgias, and nonproductive cough are typical of seasonal influenza, although the presence of nausea and vomiting is atypical in adults. (Though this patient presented for care prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19] pandemic, depending on the timing of this presentation, COVID-19 should be considered.) Acute viral myositis can complicate many viral illnesses, such as influenza, coxsackie, and Epstein-Barr virus infections. Other infectious causes of myositis include systemic bacterial infections, spirochete diseases, and other viral infections, including dengue fever. Myalgias can also be a prominent feature of noninfectious systemic inflammatory conditions, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, polymyositis, and systemic vasculitis. Night sweats, while concerning, can be present in myriad conditions, and are not usually a discriminating symptom.

Her past medical history included depression, nephrolithiasis, frequent urinary tract infections, bladder spasms, and recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infection. Her medications included bupropion, microgestin, mirabegron, and valacyclovir. Her father had emphysema.

The patient was employed as a physical therapy assistant in a geriatric care center. Two weeks prior to presentation, she traveled from her home in North Carolina to visit a friend in Atlanta, Georgia. Shortly after the patient returned home, her friend in Atlanta became ill and was treated empirically for Legionella infection because of a recent outbreak in the area. One week prior to presentation, the patient and her boyfriend went on a day hike in the Smoky Mountains in North Carolina, but the patient did not recall any insect or tick bites. Her boyfriend had not been ill.

This history elucidates several potentially relevant medication and environmental exposures. Although bupropion can cause myalgias, neither it nor the other medications she is taking are likely to cause her constellation of symptoms. Her travel history to Atlanta suggests possible, though unconfirmed, exposure to Legionella pneumophila. Notably, she would have had to be exposed to the same source as her friend, since transmission of Legionella occurs via contaminated water and soil, not by human-to-human contact. Legionella infection typically causes a pneumonic process as described here, but her prominent myalgias would not be typical.

Her hike in the Smoky Mountains could have exposed her to several vector-borne diseases. Mosquito-borne dengue in North Carolina is extremely rare, but West Nile virus and eastern equine virus are found within that region. West Nile virus could cause a similar illness, although the cough and lack of neurologic symptoms would be unusual. Eastern equine virus can also cause similar symptoms but is quite rare.

Tick-borne illnesses that should be considered for this region include Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), ehrlichiosis, and babesiosis. These tend to present with nonspecific symptoms, but myalgias and fever are consistent features. Lyme disease this close to tick exposure usually presents with the characteristic erythema migrans rash, present in 80% of cases, with or without an influenza-like illness. Approximately 80% of patients do not recall a tick bite, even though a tick must be attached for 36 to 48 hours to transmit the spirochete. RMSF often presents with fever and myalgias, with arthralgias and headache, which are lacking in this case. The common, characteristic rash of blanching erythematous macules that convert to petechiae, starting at the ankles and wrists and spreading to the trunk, is often absent at presentation, showing up at days 3 to 5 in most patients.

Ehrlichiosis presents with an influenza-like illness, but up to half of patients also have nausea and cough. It can also present with a macular and petechial rash in a minority of patients. Lastly, babesiosis presents with an influenza-like illness and less often with cough or nausea. At this juncture, RMSF and ehrlichiosis are possibilities given the hiking history and symptoms, although the absence of a rash points more to ehrlichiosis.

The patient did not smoke cigarettes but had used a JUUL© vaporizer daily for the prior 2 years. Her last use was 1 week prior to admission. She used tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) pods purchased online in the vaporizer on a few occasions 1month prior but had not used THC since that time. She denied alcohol or other drug use.

Until recently, this important detail about vaping use would have been passed over without much consideration. Though reports of acute lung injury from vaping were published as early as 2017, it first came to national attention in August 2019 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention posted a Health Advisory about severe lung injury associated with e-cigarette use. Of note, this advisory and subsequent published case series outline that e-cigarette, or vaping, use-associated lung injury (EVALI) may present with more than just respiratory symptoms. Most patients have respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, cough, or pleurisy, but many have gastrointestinal symptoms which may include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.1 Constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, or weight loss, may also predominate.2 In some cases, the gastrointestinal symptoms precede the pulmonary symptoms. This patient’s symptoms warrant consideration of EVALI starting with a chest x-ray (CXR), which is usually abnormal in this disease.2

Physical examination revealed that the patient was alert, diaphoretic, and in mild respiratory distress. Temperature was 103.6 °F, blood pressure 129/75 mm Hg, pulse 130 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 per minute, and oxygen saturation 97% while breathing ambient air. Cardiac examination revealed tachycardia without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Lung exam revealed scattered rhonchi over the left posterior lower chest without egophony or dullness to percussion. Findings from abdominal, skin, neurologic, lymph node, and musculoskeletal exams were unremarkable.

Her fever, tachycardia, and respiratory distress point to a pulmonary process such as pneumonia or EVALI, even though she does not have definitive physical exam evidence of pneumonia. She presents with systemic inflammatory response syndrome without significant hypoxia and with borderline tachypnea, which could be related to sepsis or lactic acidosis from a systemic infection other than pneumonia. Her symptom complex could also be compatible with severe influenza infection. The absence of rash makes RMSF less likely.

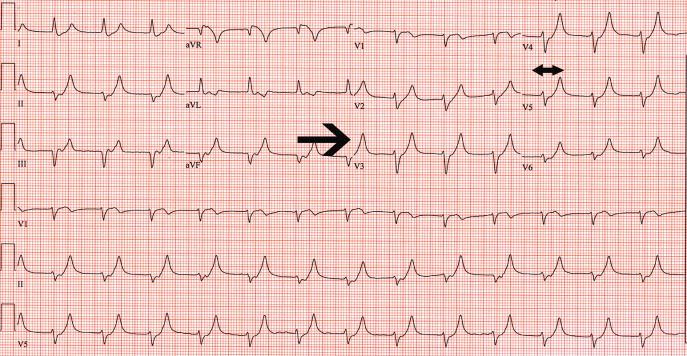

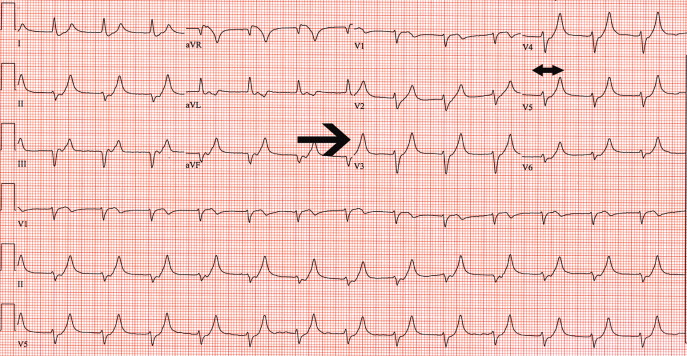

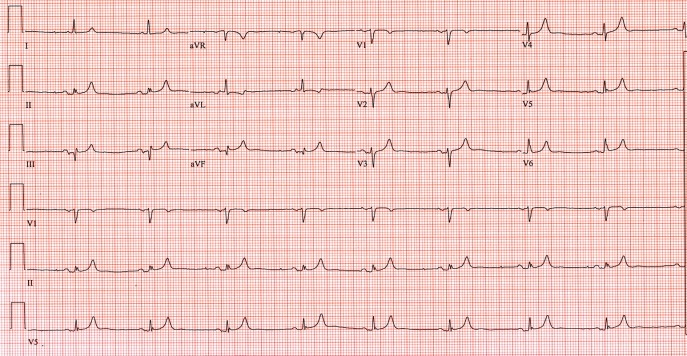

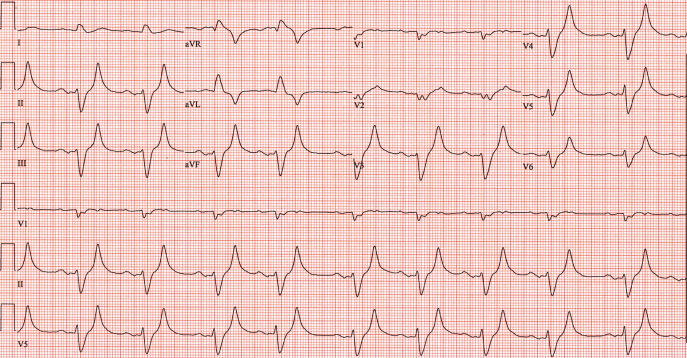

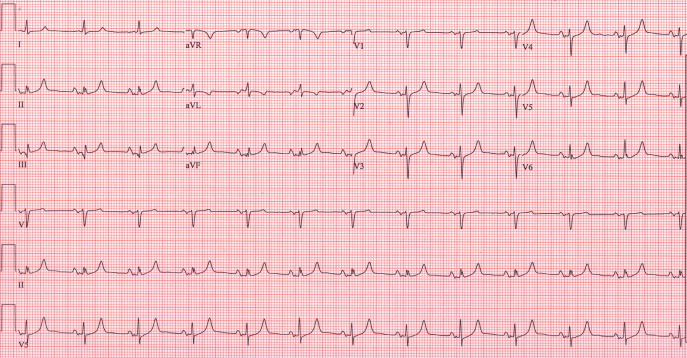

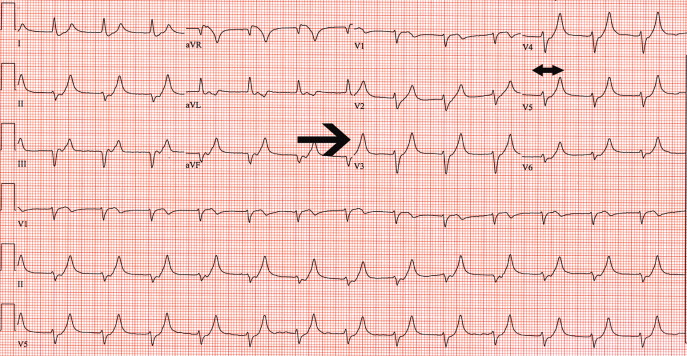

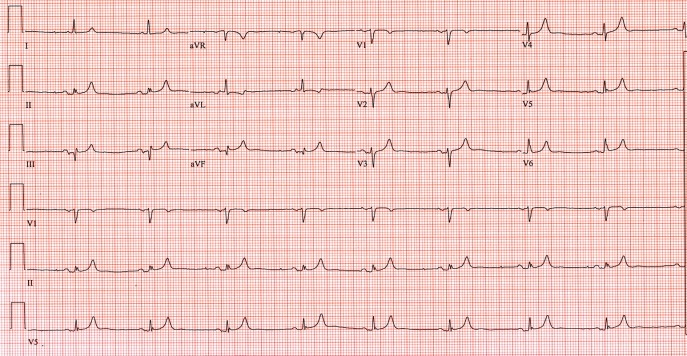

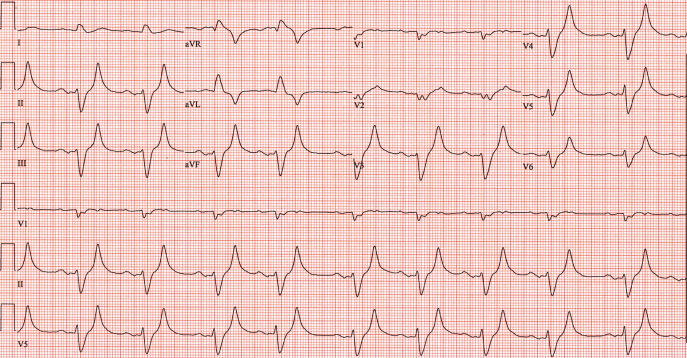

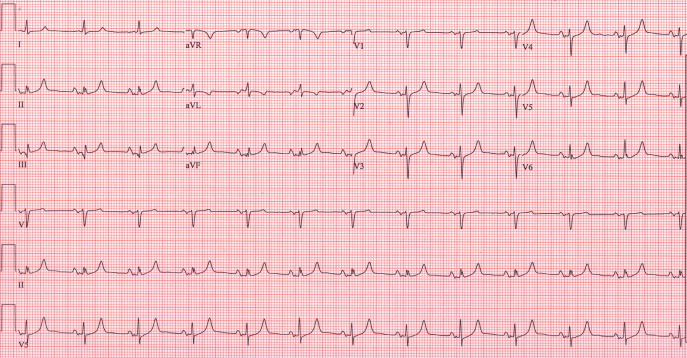

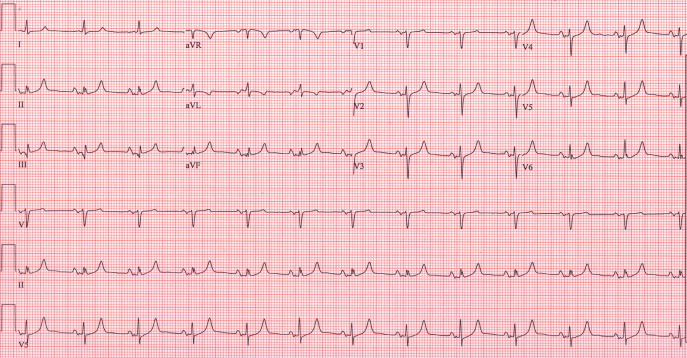

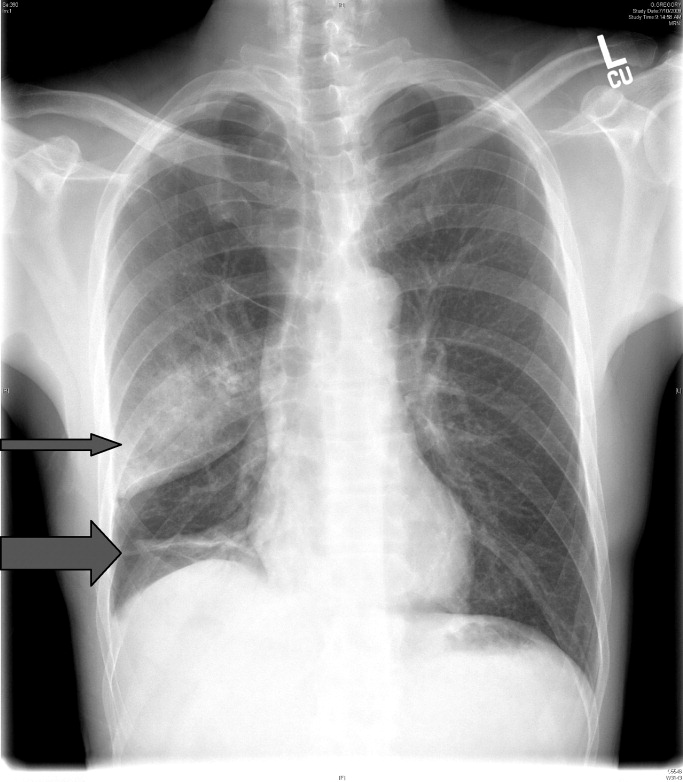

Results of a complete blood count demonstrated a white blood cell count of 12,600/µL with 87% neutrophils. Results of a metabolic panel were normal, and a urine pregnancy test was negative. The electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia without other abnormalities. A CXR showed no evidence of acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities.

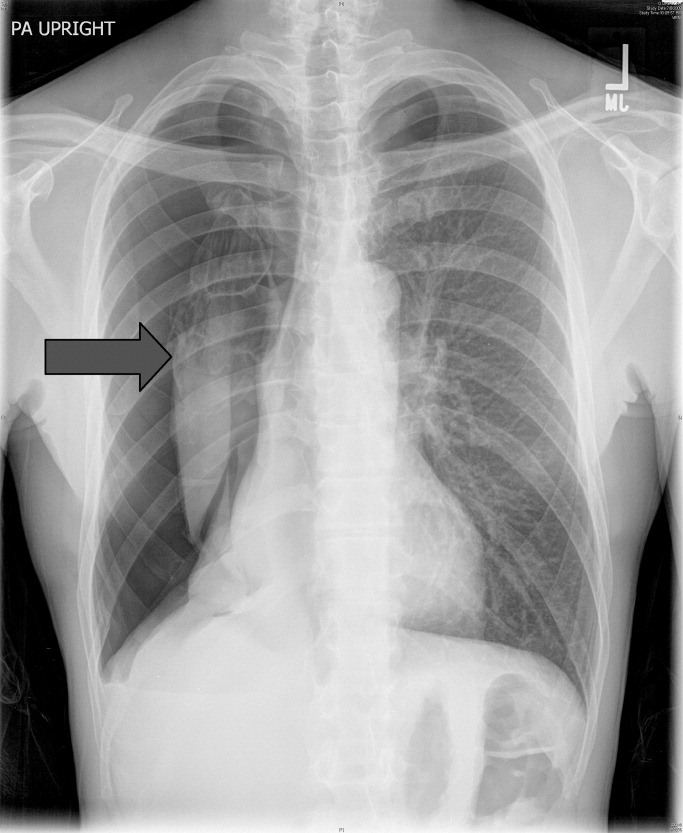

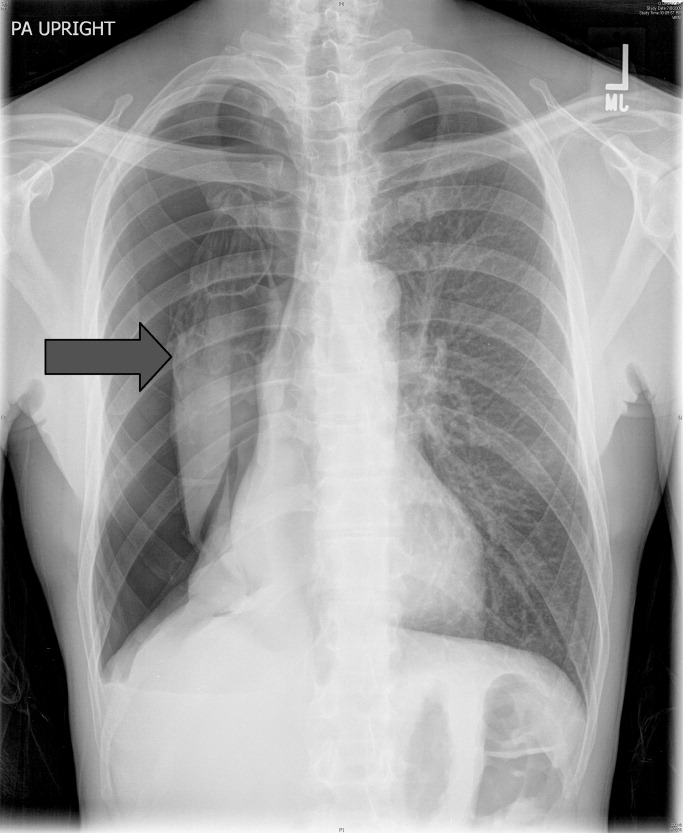

Her lab studies lack thrombocytopenia, which is often found in ehrlichiosis and RMSF. Leukopenia is also absent, which can be seen in Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis. The mild leukocytosis could be consistent with pneumonia, influenza, and EVALI and is not discriminating. The normal CXR goes against pneumonia or EVALI; however, 9% of patients with EVALI in one case series had a normal CXR, while computed tomography (CT) of the chest demonstrated bilateral ground-glass opacities.3 Chest CT is indicated in this case given the poor correlation of the CXR findings and this patient’s pronounced respiratory symptoms.

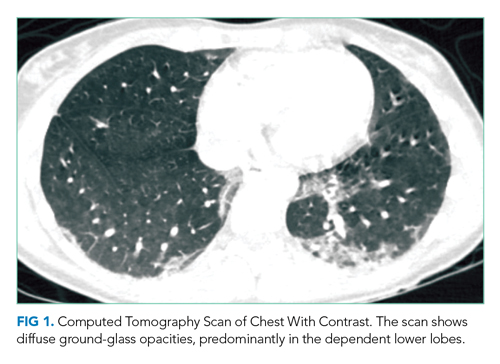

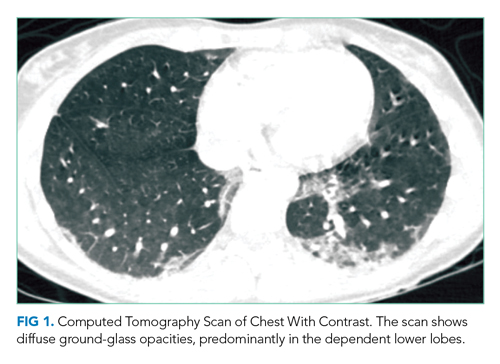

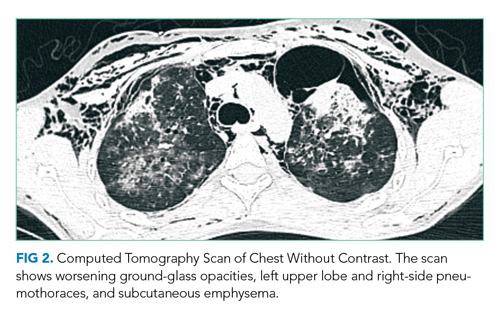

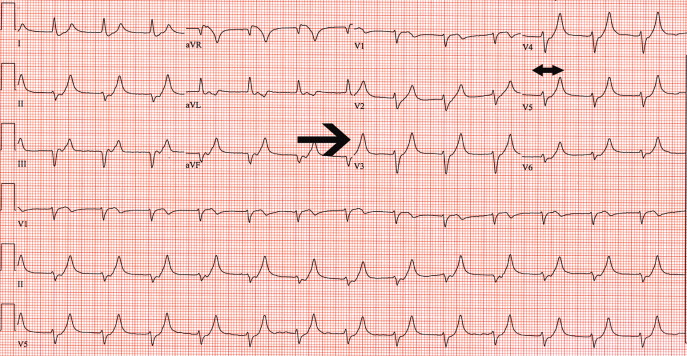

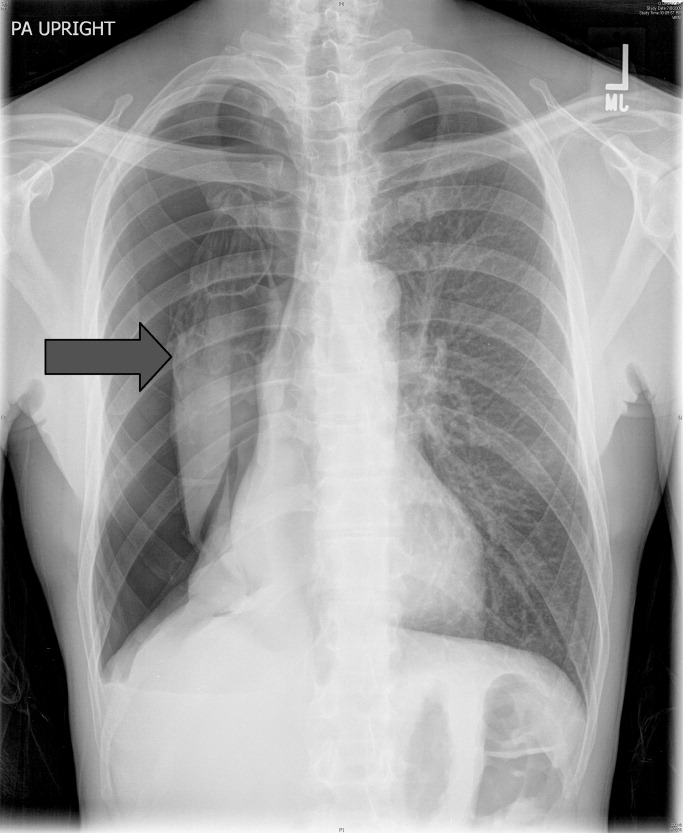

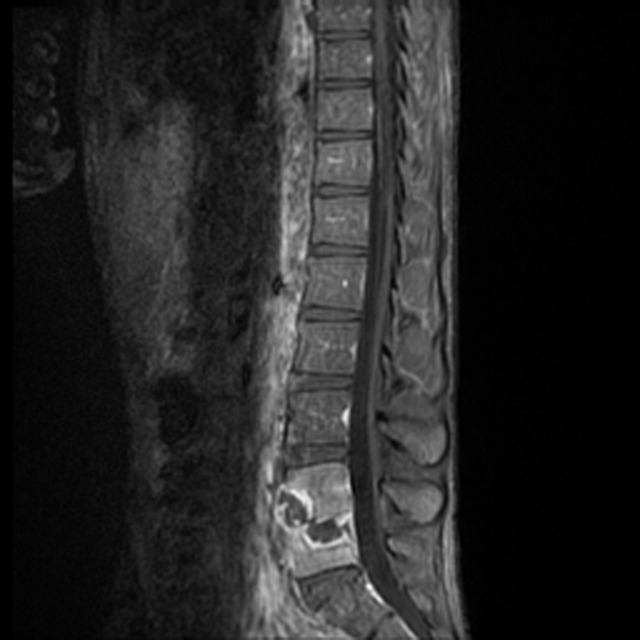

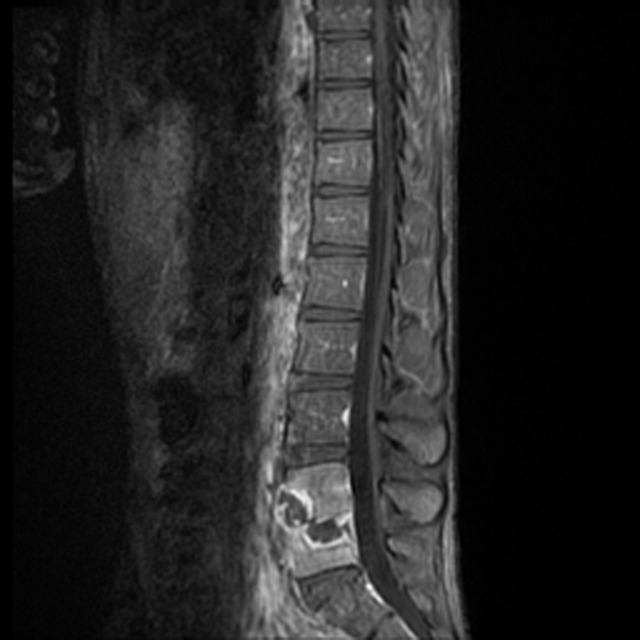

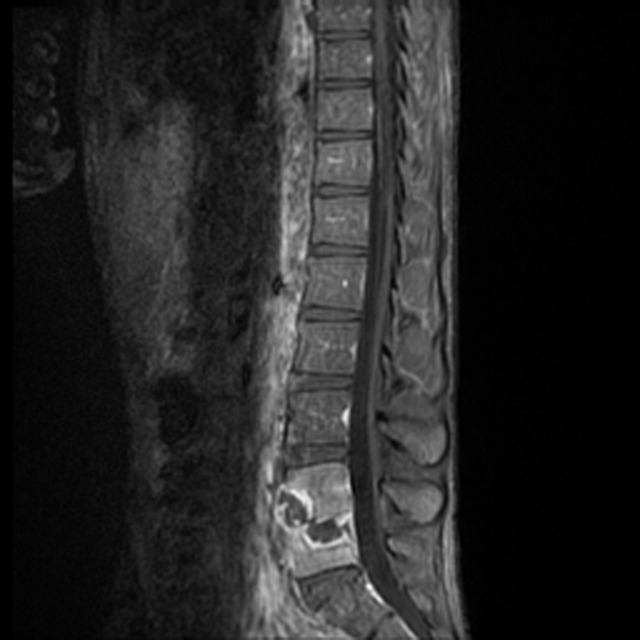

CT of the chest with contrast did not show a pulmonary embolism but revealed diffuse ground-glass opacities, predominantly in the dependent lower lobes (Figure 1).

Acute conditions with diffuse ground-glass opacities include mycoplasma, Pneumocystis jiroveci and viral pneumonias, pulmonary hemorrhage and edema, acute interstitial pneumonia, eosinophilic lung diseases, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Diffuse ground-glass opacities are also seen in almost all patients with EVALI. Though less likely, RMSF, babesiosis, and ehrlichiosis are not ruled out by these chest CT findings, since these disease entities can sometimes cause pulmonary manifestations, including pneumonia, pulmonary edema, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).4

In addition to Legionella and pneumococcal urinary antigen tests, respiratory viral panel, and blood cultures, it would be judicious to obtain HIV, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) testing; these last two tests are often markedly elevated in EVALI. The utility of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in suspected EVALI cases is not clearly defined, but should be considered in this case to ensure that infectious etiologies are not missed.2 Because of her potential environmental exposures, serologic testing for RMSF and ehrlichiosis should be sent.

Given the overlap in signs and symptoms of EVALI with various, potentially life-threatening infections, she should be empirically treated with antibiotics to cover for community-acquired pneumonia. Adding or even substituting doxycycline for a macrolide antibiotic in this regimen should be considered given that it would treat both RMSF and ehrlichiosis pending further test results. Delay in treating RMSF is associated with worse outcomes. If she is presenting during influenza season, she should also be treated with a neuraminidase inhibitor while awaiting influenza test results. Though the pathophysiology of EVALI is not entirely known, it appears to be inflammatory in nature. Most presumed cases have responded to corticosteroids, with improvement in oxygenation.2 Therefore, treatment with corticosteroids may be warranted to improve oxygenation while ruling out infectious processes.

The patient was admitted to the general medicine wards and started on ceftriaxone and azithromycin for empiric treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. On hospital day 2, a respiratory viral panel returned negative. Procalcitonin, HIV, and blood cultures all returned negative. An ESR was elevated at 86 mm/h. The patient continued to have daily fevers and developed erythematous, blanching macules on the neck, chest, back, and arms, which were noted to occur during febrile periods. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin were discontinued, and doxycycline was started. By hospital day 4, the patient’s oxygen saturation worsened to 86% on ambient air. She continued to have fevers and her cough worsened, with occasional blood-streaked sputum. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for closer monitoring.

On hospital day 5, she required intubation for worsening hypoxia. Bronchoscopy was performed, which revealed small mucosal crypts along the left mainstem bronchus. A small amount of bleeding after transbronchial biopsy of the left lower lobe was noted, which resolved with occlusion using the bronchoscope. BAL was performed, which revealed red, cloudy aspirate with 1,100 white blood cells (85% neutrophils) and 22,400 red blood cells. No bacteria were identified.

The patient has developed hypoxic respiratory failure despite appropriate antibiotics and negative cultures, increasing the likelihood of a noninfectious etiology. Her rash is not typical for RMSF, which usually starts as a macular or petechial rash at the ankles and wrists, and spreads centrally to the trunk. Rash is not typically associated with EVALI, and in this case, may represent miliaria caused by her fever.

The mucosal crypts seen on bronchoscopy are nonspecific, likely indicating inflammation from vaping. The BAL otherwise suggests diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), although sequential BAL aliquots are needed to confirm this diagnosis. DAH is usually caused by pulmonary capillaritis from vasculitis, Goodpasture disease, rheumatic diseases, or diffuse alveolar damage from toxins, infections, rheumatic diseases, or interstitial or organizing pneumonias. Diffuse alveolar damage is the pathologic finding of ARDS, which can be seen in severe cases of many of the conditions discussed, including EVALI, ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, sepsis, and community-acquired pneumonia.4

The BAL is most consistent with EVALI, which often shows elevated neutrophils. DAH due to vaping has also been reported.5 In patients with EVALI, varied pathologic findings of acute lung injury have been reported, including diffuse alveolar damage.6 At this point, laboratory evaluation for rheumatologic diseases and vasculitis should be obtained, and lung biopsy results reviewed. Given her clinical deterioration, treatment with intravenous corticosteroids for presumed EVALI is warranted.

Urine Legionella and Streptococcal pneumoniae antigen tests were negative. The patient was started on methylprednisolone 40 mg intravenously every 8 hours. Further testing included antinuclear antibodies, which was positive at 1:320, with a dense, fine speckled pattern. Perinuclear antineutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody, cytoplasmic antineutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody, myeloperoxidase, proteinase 3, double-stranded DNA, and glomerular basement membrane IgG were all negative. Transbronchial lung biopsy revealed severe acute lung injury consistent with diffuse alveolar damage. The pulmonary interstitium was mildly expanded by edema, with a moderate number of eosinophilic hyaline membranes. There were no eosinophils or evidence of hemorrhage, granulomas, or giant cells. These changes, within this clinical context, were diagnostic for EVALI.

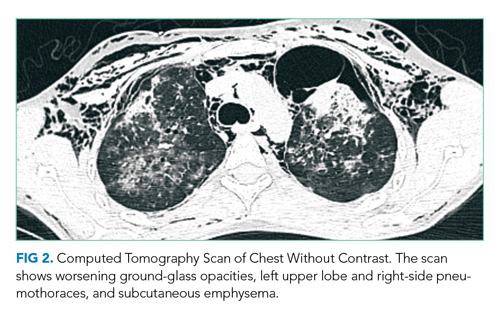

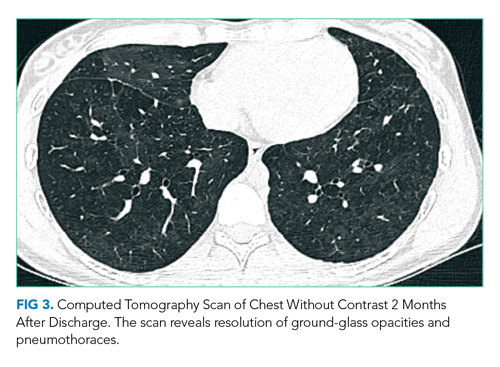

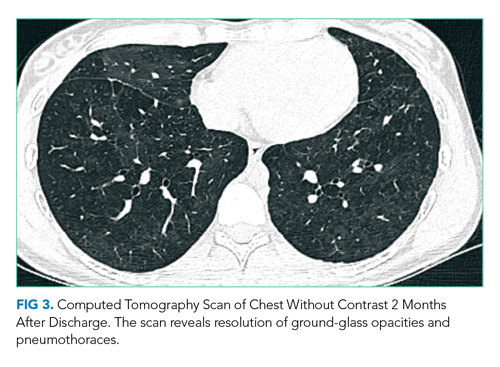

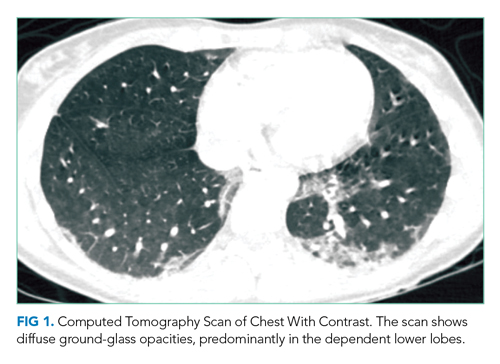

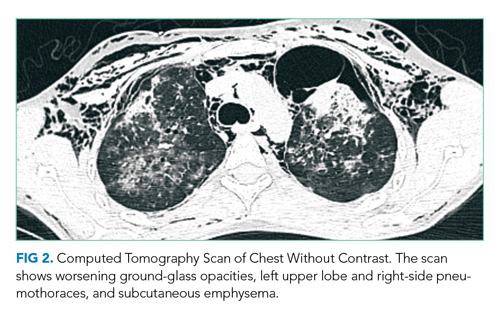

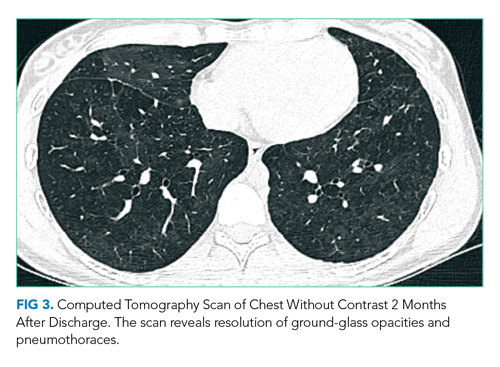

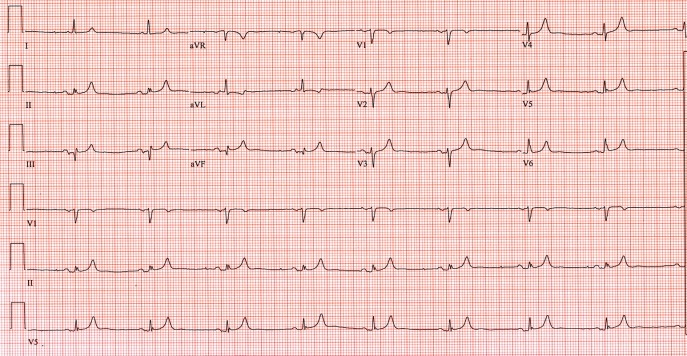

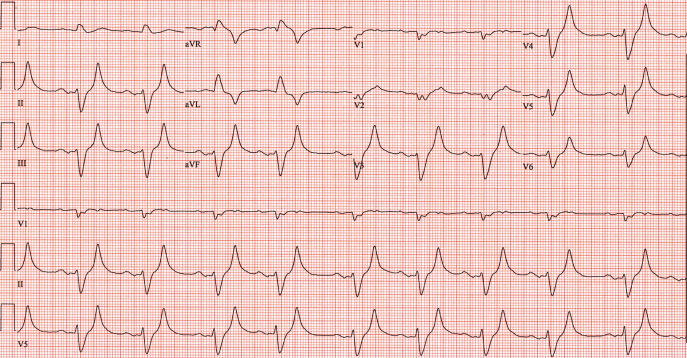

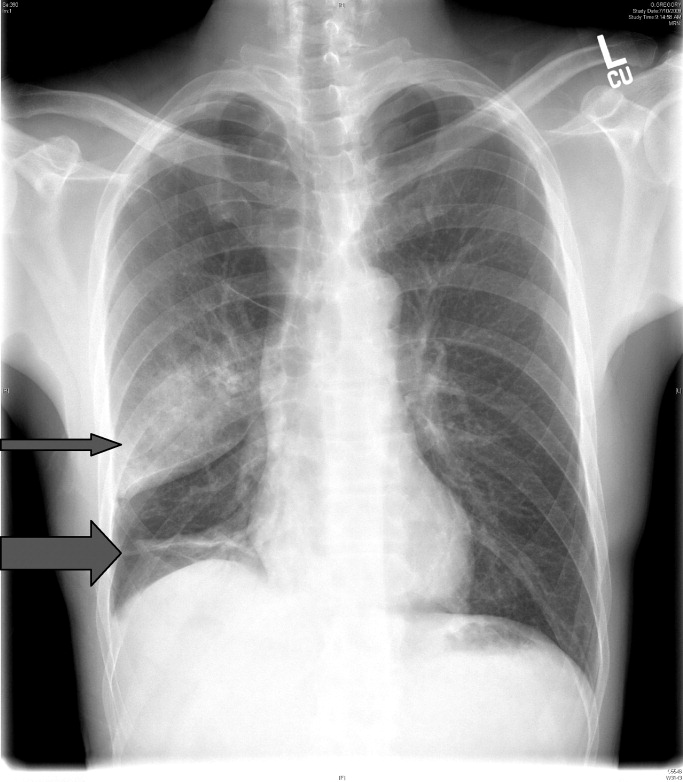

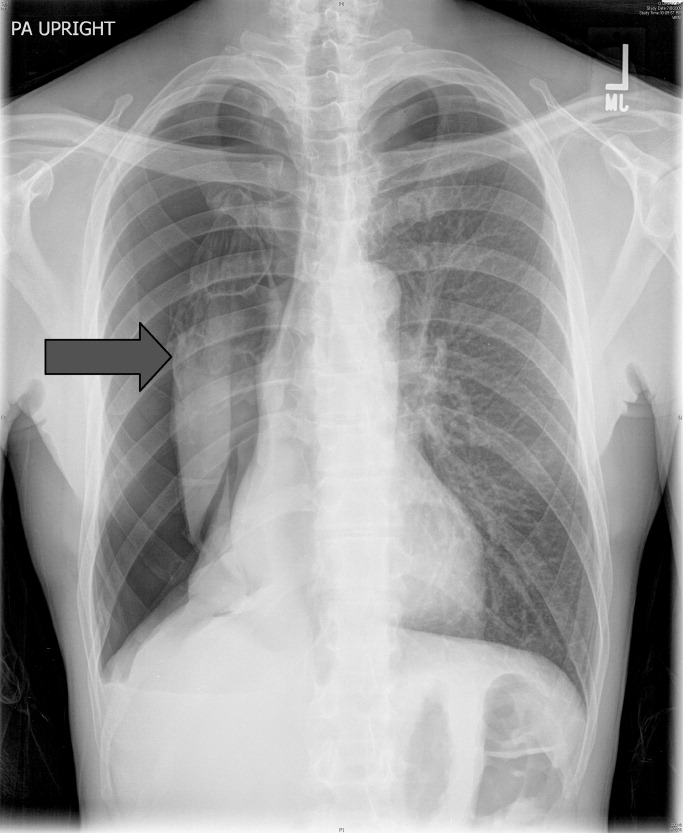

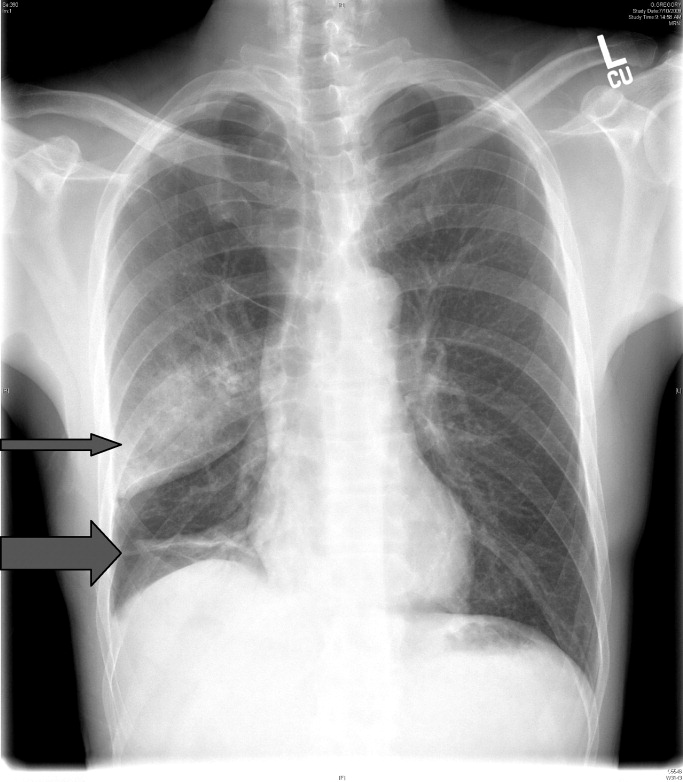

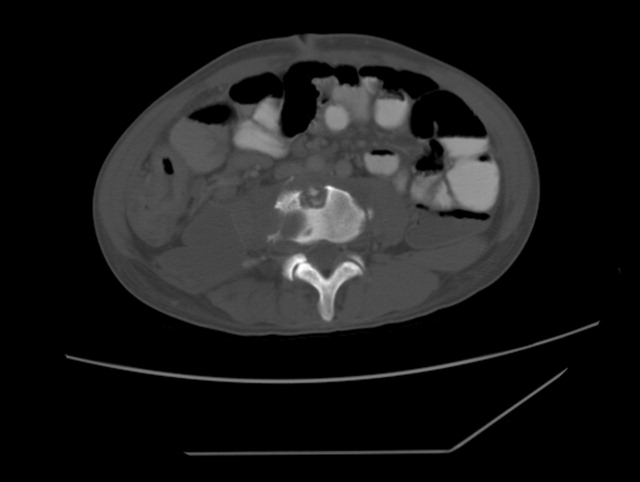

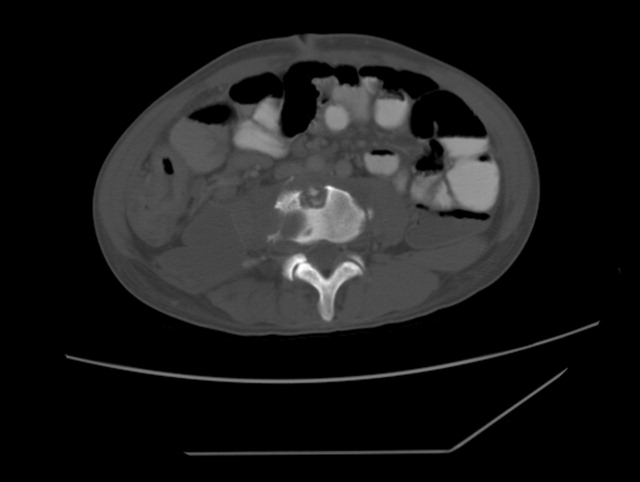

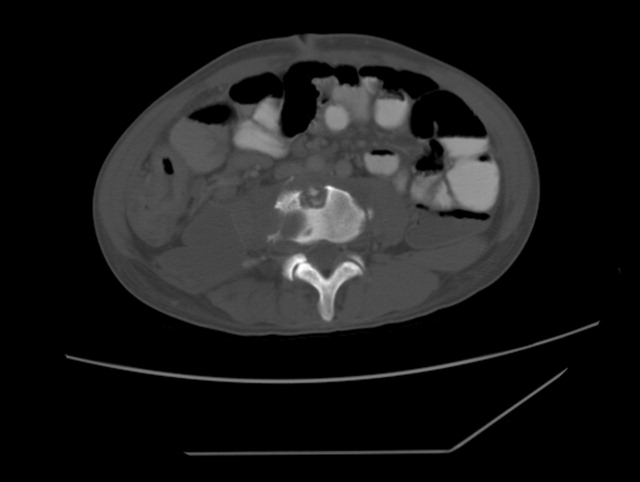

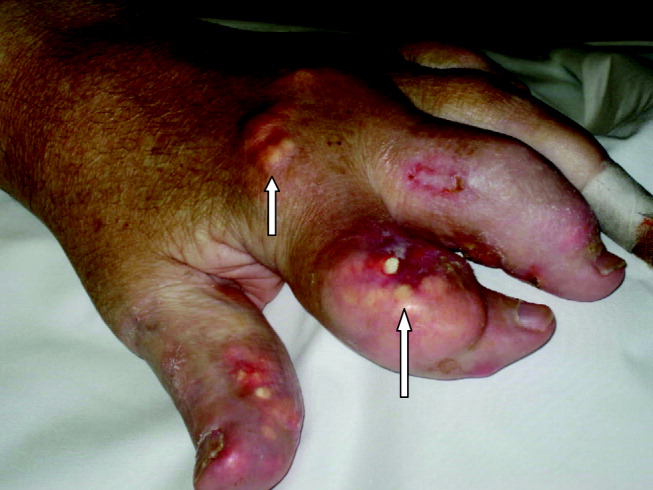

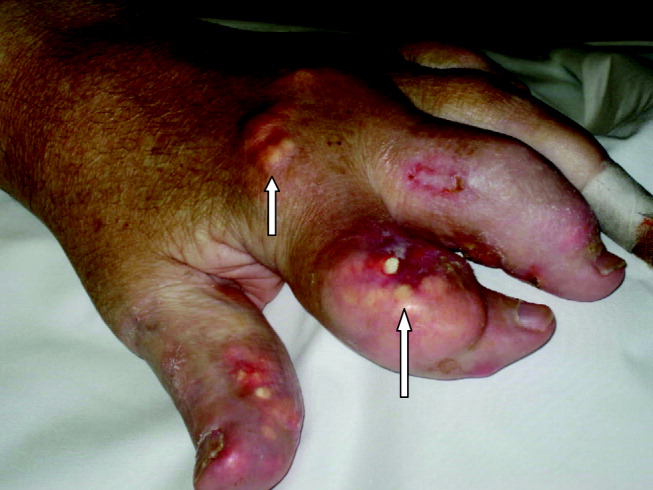

The patient was intubated for 4 days and completed a course of empiric antibiotics as well as a 10-day course of prednisone. She was discharged on hospital day 17 on 2 L continuous oxygen via nasal cannula. Two days after discharge, she developed worsening dyspnea and chest pain and was readmitted with worsening ground-glass opacities, left upper lobe and right- sided pneumothoraces, and subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 2). She was treated with continuous oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation at 100% and eventually discharged home 3 days later on 3 L continuous oxygen. She attended pulmonary rehabilitation and was weaned off oxygen 2 months later, with marked improvement in aeration of both lungs (Figure 3). She continued to abstain from tobacco and THC products.

DISCUSSION

The first electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) device was developed in 2003 by a Chinese pharmacist and introduced to the American market in 2007.7 E-cigarettes produce an inhalable aerosol by heating a liquid containing a variety of chemicals, nicotine, and flavors, with or without other additives. Originally promoted as a safer nontobacco and cessation device by producers, e-cigarette sales grew at an annual rate of 115% between 2009 and 2012.8 E-cigarettes can also be used to deliver THC, the psychoactive component of cannabis.

Since the advent of e-cigarettes, their safety has been a topic of concern. In August 2019, the CDC announced 215 possible cases of severe pulmonary disease associated with the use of e-cigarette products that were reported by 25 state health departments.1 By February 2020, EVALI had affected more than 2,800 patients hospitalized across the United States.9

The presenting symptoms of EVALI are varied and nonspecific. The largest EVALI case series, published by Layden et al in 2020, included 98 patients who had a median duration of 6 days of symptoms prior to presentation.3 Respiratory symptoms occurred in 97% of patients, including shortness of breath, any chest pain, pleuritic chest pain, cough, and hemoptysis.3 Presentations also included a variety of gastrointestinal (77%) and constitutional (100%) symptoms, which most commonly included nausea, vomiting, and fever.3 Additional case series have supported a specific pattern of presentation, most commonly including pleuritic chest pain, nonproductive cough, or shortness of breath occurring days to weeks prior to presentation. Associated fatigue, fever, and tachycardia may be present, as well as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain, and in some cases, these have preceded respiratory symptoms.3,10,11

The vital signs and physical examination, laboratory, and imaging results associated with EVALI are also fairly nonspecific. The most common reason for hospitalization in EVALI is hypoxia, which can progress to acute respiratory failure requiring supplemental oxygen or, as in this case, mechanical ventilation. The most common laboratory finding is leukocytosis greater than 11,000/µL, with more than 80% neutrophils and an ESR greater than 30 mm/hr. In the Layden et al case series, 83% of patients had an abnormal CXR. All patients who underwent CT scan of the chest had bilateral ground-glass opacities, often with subpleural sparing.3 A minority of patients were found to have a pneumothorax, generally a late finding.3,12 Accordingly, the CDC now defines confirmed EVALI as use of e-cigarettes during the 90 days before symptom onset with the presence of pulmonary infiltrates (opacities on CXR or ground-glass opacities on chest CT), negative results on testing for all clinically indicated respiratory infections including respiratory viral panel and influenza PCR, and no alternative plausible diagnoses.13

The presumed etiology of EVALI is chemical exposure because no consistent infectious etiology has been identified.6 No consistent e-cigarette product, substance, or additive has been identified in all cases, nor has one product been directly linked to EVALI. However, the CDC recently announced that vitamin E acetate in vaping products appears to be associated with EVALI.9 In December 2019, Blount et al identified vitamin E acetate in BAL fluid samples from 48 of 51 EVALI patients.14 Additionally, while no other toxins were identified, 94% of samples contained THC or its metabolites or patients had reported vaping THC within 90 days preceding illness.14

The most effective treatment strategy for EVALI is still unknown. It is recommended to treat with empiric antibiotics for at least 48 hours (and antivirals during influenza season) if the history is unclear or if the patient is intubated or has severe hypoxemia.2 If antibiotic and/or antiviral therapies do not lead to clinical improvement, corticosteroids should be added, as they lead to improved oxygenation in many patients.2 Kalininskiy et al recommend initial administration of methylprednisolone 40 mg every 8 hours, with transition to oral prednisone to complete a 2-week course.2 Given rates of rehospitalization (2.7%) and death (2%) in EVALI, the CDC advises that patients should be clinically stable for 24 to 48 hours prior to discharge; that follow-up visits should be arranged within 48 hours of discharge; and that cases of EVALI should be reported to the state and local health departments.15 As seen in the case presented here, with time and continued abstinence from e-cigarette use, the pulmonary effects of EVALI can improve, but long-term outcomes remain unclear. Clinicians must now consider EVALI in patients presenting with respiratory, constitutional, and gastrointestinal complaints when a history of e-cigarette use is present.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- EVALI presents most commonly with a combination of respiratory, gastrointestinal, and constitutional symptoms. including shortness of breath, cough, nausea, vomiting, and fever.

- When considering EVALI, evaluate and treat for potential infectious causes of disease first.

- Corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy in EVALI, leading to improvement in oxygenation in many patients.

- Most of the reported cases of EVALI have occurred in patients who have vaped THC-containing products.

1. Schier JG, Meiman JG, Layden J, et al. Severe pulmonary disease associated with electronic-cigarette-product use – Interim guidance. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68(36):787-790. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6836e2

2. Kalininskiy A, Bach CT, Nacca NE, et al. E-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI): case series and diagnostic approach. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(12):1017-1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(19)30415-1

3. Layden JE, Ghinai I, Pray I, et al. Pulmonary illness related to e-cigarette use in Illiniois and Wisconsin – final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):903-916. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1911614

4. Faul JL, Doyle RL, Kao PN, Ruoss SJ. Tick-borne pulmonary disease: update on diagnosis and management. Chest. 1999;116(1):222-230. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.116.1.222

5. Agustin M, Yamamoto M, Cabrera F, Eusebio R. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage induced by vaping. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2018;2018:9724530. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9724530

6. Butt YM, Smith ML, Tazelaar HD, et al. Pathology of vaping-associated lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1780-1781. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc1913069

7. Office of the Surgeon General. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults. Chapter 1. Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2016. Accessed January 22, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/e-cigarettes/index.htm

8. Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. Background Paper on E-cigarettes (Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems). UCSF: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education; 2013. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/13p2b72n

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping. December 12, 2019. Updated February 25, 2020. Accessed January 22, 2020 and July 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

10. Davidson K, Brancato A, Heetkerks P, et al. Outbreak of e-cigarette-associated acute lipoid pneumonia—North Carolina, July-August 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(36);784-786. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6836e1

11. Maddock SD, Cirulis MM, Callahan SJ, et al. Pulmonary lipid-laden macrophages and vaping. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1488-1489. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc1912038

12. Henry TS, Kanne JP, Klingerman SJ. Imaging of vaping-associated lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1486-1487. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc1911995

13. Smoking and Tobacco Use: For State, Local, Territorial, and Tribal Health Departments. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed Jan 24, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease/health-departments/index.html

14. Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, et al. Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):697-705. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1916433

15. Evans ME, Twentyman E, Click ES, et al. Update: Interim guidance for health care professionals evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury and for reducing the risk for rehospitalization and death following hospital discharge — United States, December 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;68(5152):1189-1194. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm685152e2

A 23-year-old woman presented to the emergency department complaining of “feeling terrible” for the past week. She described subjective fevers, chills, nonproductive cough, myalgias, and nausea. Her symptoms worsened on the day of presentation, with drenching night sweats, worsening myalgias, and generalized fatigue. She was unable to tolerate oral intake due to persistent nausea and had one episode of emesis.

While the initial constellation of symptoms suggests a viral syndrome, its progression over a week raises concern for something more ominous. Of her relatively nonspecific symptoms, prominent myalgias accompanied by a febrile illness may be most helpful. Fever, myalgias, and nonproductive cough are typical of seasonal influenza, although the presence of nausea and vomiting is atypical in adults. (Though this patient presented for care prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19] pandemic, depending on the timing of this presentation, COVID-19 should be considered.) Acute viral myositis can complicate many viral illnesses, such as influenza, coxsackie, and Epstein-Barr virus infections. Other infectious causes of myositis include systemic bacterial infections, spirochete diseases, and other viral infections, including dengue fever. Myalgias can also be a prominent feature of noninfectious systemic inflammatory conditions, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, polymyositis, and systemic vasculitis. Night sweats, while concerning, can be present in myriad conditions, and are not usually a discriminating symptom.

Her past medical history included depression, nephrolithiasis, frequent urinary tract infections, bladder spasms, and recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infection. Her medications included bupropion, microgestin, mirabegron, and valacyclovir. Her father had emphysema.

The patient was employed as a physical therapy assistant in a geriatric care center. Two weeks prior to presentation, she traveled from her home in North Carolina to visit a friend in Atlanta, Georgia. Shortly after the patient returned home, her friend in Atlanta became ill and was treated empirically for Legionella infection because of a recent outbreak in the area. One week prior to presentation, the patient and her boyfriend went on a day hike in the Smoky Mountains in North Carolina, but the patient did not recall any insect or tick bites. Her boyfriend had not been ill.

This history elucidates several potentially relevant medication and environmental exposures. Although bupropion can cause myalgias, neither it nor the other medications she is taking are likely to cause her constellation of symptoms. Her travel history to Atlanta suggests possible, though unconfirmed, exposure to Legionella pneumophila. Notably, she would have had to be exposed to the same source as her friend, since transmission of Legionella occurs via contaminated water and soil, not by human-to-human contact. Legionella infection typically causes a pneumonic process as described here, but her prominent myalgias would not be typical.

Her hike in the Smoky Mountains could have exposed her to several vector-borne diseases. Mosquito-borne dengue in North Carolina is extremely rare, but West Nile virus and eastern equine virus are found within that region. West Nile virus could cause a similar illness, although the cough and lack of neurologic symptoms would be unusual. Eastern equine virus can also cause similar symptoms but is quite rare.

Tick-borne illnesses that should be considered for this region include Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), ehrlichiosis, and babesiosis. These tend to present with nonspecific symptoms, but myalgias and fever are consistent features. Lyme disease this close to tick exposure usually presents with the characteristic erythema migrans rash, present in 80% of cases, with or without an influenza-like illness. Approximately 80% of patients do not recall a tick bite, even though a tick must be attached for 36 to 48 hours to transmit the spirochete. RMSF often presents with fever and myalgias, with arthralgias and headache, which are lacking in this case. The common, characteristic rash of blanching erythematous macules that convert to petechiae, starting at the ankles and wrists and spreading to the trunk, is often absent at presentation, showing up at days 3 to 5 in most patients.

Ehrlichiosis presents with an influenza-like illness, but up to half of patients also have nausea and cough. It can also present with a macular and petechial rash in a minority of patients. Lastly, babesiosis presents with an influenza-like illness and less often with cough or nausea. At this juncture, RMSF and ehrlichiosis are possibilities given the hiking history and symptoms, although the absence of a rash points more to ehrlichiosis.

The patient did not smoke cigarettes but had used a JUUL© vaporizer daily for the prior 2 years. Her last use was 1 week prior to admission. She used tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) pods purchased online in the vaporizer on a few occasions 1month prior but had not used THC since that time. She denied alcohol or other drug use.

Until recently, this important detail about vaping use would have been passed over without much consideration. Though reports of acute lung injury from vaping were published as early as 2017, it first came to national attention in August 2019 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention posted a Health Advisory about severe lung injury associated with e-cigarette use. Of note, this advisory and subsequent published case series outline that e-cigarette, or vaping, use-associated lung injury (EVALI) may present with more than just respiratory symptoms. Most patients have respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, cough, or pleurisy, but many have gastrointestinal symptoms which may include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.1 Constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, or weight loss, may also predominate.2 In some cases, the gastrointestinal symptoms precede the pulmonary symptoms. This patient’s symptoms warrant consideration of EVALI starting with a chest x-ray (CXR), which is usually abnormal in this disease.2

Physical examination revealed that the patient was alert, diaphoretic, and in mild respiratory distress. Temperature was 103.6 °F, blood pressure 129/75 mm Hg, pulse 130 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 per minute, and oxygen saturation 97% while breathing ambient air. Cardiac examination revealed tachycardia without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Lung exam revealed scattered rhonchi over the left posterior lower chest without egophony or dullness to percussion. Findings from abdominal, skin, neurologic, lymph node, and musculoskeletal exams were unremarkable.

Her fever, tachycardia, and respiratory distress point to a pulmonary process such as pneumonia or EVALI, even though she does not have definitive physical exam evidence of pneumonia. She presents with systemic inflammatory response syndrome without significant hypoxia and with borderline tachypnea, which could be related to sepsis or lactic acidosis from a systemic infection other than pneumonia. Her symptom complex could also be compatible with severe influenza infection. The absence of rash makes RMSF less likely.

Results of a complete blood count demonstrated a white blood cell count of 12,600/µL with 87% neutrophils. Results of a metabolic panel were normal, and a urine pregnancy test was negative. The electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia without other abnormalities. A CXR showed no evidence of acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities.

Her lab studies lack thrombocytopenia, which is often found in ehrlichiosis and RMSF. Leukopenia is also absent, which can be seen in Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis. The mild leukocytosis could be consistent with pneumonia, influenza, and EVALI and is not discriminating. The normal CXR goes against pneumonia or EVALI; however, 9% of patients with EVALI in one case series had a normal CXR, while computed tomography (CT) of the chest demonstrated bilateral ground-glass opacities.3 Chest CT is indicated in this case given the poor correlation of the CXR findings and this patient’s pronounced respiratory symptoms.

CT of the chest with contrast did not show a pulmonary embolism but revealed diffuse ground-glass opacities, predominantly in the dependent lower lobes (Figure 1).

Acute conditions with diffuse ground-glass opacities include mycoplasma, Pneumocystis jiroveci and viral pneumonias, pulmonary hemorrhage and edema, acute interstitial pneumonia, eosinophilic lung diseases, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Diffuse ground-glass opacities are also seen in almost all patients with EVALI. Though less likely, RMSF, babesiosis, and ehrlichiosis are not ruled out by these chest CT findings, since these disease entities can sometimes cause pulmonary manifestations, including pneumonia, pulmonary edema, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).4

In addition to Legionella and pneumococcal urinary antigen tests, respiratory viral panel, and blood cultures, it would be judicious to obtain HIV, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) testing; these last two tests are often markedly elevated in EVALI. The utility of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in suspected EVALI cases is not clearly defined, but should be considered in this case to ensure that infectious etiologies are not missed.2 Because of her potential environmental exposures, serologic testing for RMSF and ehrlichiosis should be sent.

Given the overlap in signs and symptoms of EVALI with various, potentially life-threatening infections, she should be empirically treated with antibiotics to cover for community-acquired pneumonia. Adding or even substituting doxycycline for a macrolide antibiotic in this regimen should be considered given that it would treat both RMSF and ehrlichiosis pending further test results. Delay in treating RMSF is associated with worse outcomes. If she is presenting during influenza season, she should also be treated with a neuraminidase inhibitor while awaiting influenza test results. Though the pathophysiology of EVALI is not entirely known, it appears to be inflammatory in nature. Most presumed cases have responded to corticosteroids, with improvement in oxygenation.2 Therefore, treatment with corticosteroids may be warranted to improve oxygenation while ruling out infectious processes.

The patient was admitted to the general medicine wards and started on ceftriaxone and azithromycin for empiric treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. On hospital day 2, a respiratory viral panel returned negative. Procalcitonin, HIV, and blood cultures all returned negative. An ESR was elevated at 86 mm/h. The patient continued to have daily fevers and developed erythematous, blanching macules on the neck, chest, back, and arms, which were noted to occur during febrile periods. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin were discontinued, and doxycycline was started. By hospital day 4, the patient’s oxygen saturation worsened to 86% on ambient air. She continued to have fevers and her cough worsened, with occasional blood-streaked sputum. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for closer monitoring.

On hospital day 5, she required intubation for worsening hypoxia. Bronchoscopy was performed, which revealed small mucosal crypts along the left mainstem bronchus. A small amount of bleeding after transbronchial biopsy of the left lower lobe was noted, which resolved with occlusion using the bronchoscope. BAL was performed, which revealed red, cloudy aspirate with 1,100 white blood cells (85% neutrophils) and 22,400 red blood cells. No bacteria were identified.

The patient has developed hypoxic respiratory failure despite appropriate antibiotics and negative cultures, increasing the likelihood of a noninfectious etiology. Her rash is not typical for RMSF, which usually starts as a macular or petechial rash at the ankles and wrists, and spreads centrally to the trunk. Rash is not typically associated with EVALI, and in this case, may represent miliaria caused by her fever.

The mucosal crypts seen on bronchoscopy are nonspecific, likely indicating inflammation from vaping. The BAL otherwise suggests diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), although sequential BAL aliquots are needed to confirm this diagnosis. DAH is usually caused by pulmonary capillaritis from vasculitis, Goodpasture disease, rheumatic diseases, or diffuse alveolar damage from toxins, infections, rheumatic diseases, or interstitial or organizing pneumonias. Diffuse alveolar damage is the pathologic finding of ARDS, which can be seen in severe cases of many of the conditions discussed, including EVALI, ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, sepsis, and community-acquired pneumonia.4

The BAL is most consistent with EVALI, which often shows elevated neutrophils. DAH due to vaping has also been reported.5 In patients with EVALI, varied pathologic findings of acute lung injury have been reported, including diffuse alveolar damage.6 At this point, laboratory evaluation for rheumatologic diseases and vasculitis should be obtained, and lung biopsy results reviewed. Given her clinical deterioration, treatment with intravenous corticosteroids for presumed EVALI is warranted.

Urine Legionella and Streptococcal pneumoniae antigen tests were negative. The patient was started on methylprednisolone 40 mg intravenously every 8 hours. Further testing included antinuclear antibodies, which was positive at 1:320, with a dense, fine speckled pattern. Perinuclear antineutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody, cytoplasmic antineutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody, myeloperoxidase, proteinase 3, double-stranded DNA, and glomerular basement membrane IgG were all negative. Transbronchial lung biopsy revealed severe acute lung injury consistent with diffuse alveolar damage. The pulmonary interstitium was mildly expanded by edema, with a moderate number of eosinophilic hyaline membranes. There were no eosinophils or evidence of hemorrhage, granulomas, or giant cells. These changes, within this clinical context, were diagnostic for EVALI.

The patient was intubated for 4 days and completed a course of empiric antibiotics as well as a 10-day course of prednisone. She was discharged on hospital day 17 on 2 L continuous oxygen via nasal cannula. Two days after discharge, she developed worsening dyspnea and chest pain and was readmitted with worsening ground-glass opacities, left upper lobe and right- sided pneumothoraces, and subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 2). She was treated with continuous oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation at 100% and eventually discharged home 3 days later on 3 L continuous oxygen. She attended pulmonary rehabilitation and was weaned off oxygen 2 months later, with marked improvement in aeration of both lungs (Figure 3). She continued to abstain from tobacco and THC products.

DISCUSSION

The first electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) device was developed in 2003 by a Chinese pharmacist and introduced to the American market in 2007.7 E-cigarettes produce an inhalable aerosol by heating a liquid containing a variety of chemicals, nicotine, and flavors, with or without other additives. Originally promoted as a safer nontobacco and cessation device by producers, e-cigarette sales grew at an annual rate of 115% between 2009 and 2012.8 E-cigarettes can also be used to deliver THC, the psychoactive component of cannabis.

Since the advent of e-cigarettes, their safety has been a topic of concern. In August 2019, the CDC announced 215 possible cases of severe pulmonary disease associated with the use of e-cigarette products that were reported by 25 state health departments.1 By February 2020, EVALI had affected more than 2,800 patients hospitalized across the United States.9

The presenting symptoms of EVALI are varied and nonspecific. The largest EVALI case series, published by Layden et al in 2020, included 98 patients who had a median duration of 6 days of symptoms prior to presentation.3 Respiratory symptoms occurred in 97% of patients, including shortness of breath, any chest pain, pleuritic chest pain, cough, and hemoptysis.3 Presentations also included a variety of gastrointestinal (77%) and constitutional (100%) symptoms, which most commonly included nausea, vomiting, and fever.3 Additional case series have supported a specific pattern of presentation, most commonly including pleuritic chest pain, nonproductive cough, or shortness of breath occurring days to weeks prior to presentation. Associated fatigue, fever, and tachycardia may be present, as well as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain, and in some cases, these have preceded respiratory symptoms.3,10,11

The vital signs and physical examination, laboratory, and imaging results associated with EVALI are also fairly nonspecific. The most common reason for hospitalization in EVALI is hypoxia, which can progress to acute respiratory failure requiring supplemental oxygen or, as in this case, mechanical ventilation. The most common laboratory finding is leukocytosis greater than 11,000/µL, with more than 80% neutrophils and an ESR greater than 30 mm/hr. In the Layden et al case series, 83% of patients had an abnormal CXR. All patients who underwent CT scan of the chest had bilateral ground-glass opacities, often with subpleural sparing.3 A minority of patients were found to have a pneumothorax, generally a late finding.3,12 Accordingly, the CDC now defines confirmed EVALI as use of e-cigarettes during the 90 days before symptom onset with the presence of pulmonary infiltrates (opacities on CXR or ground-glass opacities on chest CT), negative results on testing for all clinically indicated respiratory infections including respiratory viral panel and influenza PCR, and no alternative plausible diagnoses.13

The presumed etiology of EVALI is chemical exposure because no consistent infectious etiology has been identified.6 No consistent e-cigarette product, substance, or additive has been identified in all cases, nor has one product been directly linked to EVALI. However, the CDC recently announced that vitamin E acetate in vaping products appears to be associated with EVALI.9 In December 2019, Blount et al identified vitamin E acetate in BAL fluid samples from 48 of 51 EVALI patients.14 Additionally, while no other toxins were identified, 94% of samples contained THC or its metabolites or patients had reported vaping THC within 90 days preceding illness.14

The most effective treatment strategy for EVALI is still unknown. It is recommended to treat with empiric antibiotics for at least 48 hours (and antivirals during influenza season) if the history is unclear or if the patient is intubated or has severe hypoxemia.2 If antibiotic and/or antiviral therapies do not lead to clinical improvement, corticosteroids should be added, as they lead to improved oxygenation in many patients.2 Kalininskiy et al recommend initial administration of methylprednisolone 40 mg every 8 hours, with transition to oral prednisone to complete a 2-week course.2 Given rates of rehospitalization (2.7%) and death (2%) in EVALI, the CDC advises that patients should be clinically stable for 24 to 48 hours prior to discharge; that follow-up visits should be arranged within 48 hours of discharge; and that cases of EVALI should be reported to the state and local health departments.15 As seen in the case presented here, with time and continued abstinence from e-cigarette use, the pulmonary effects of EVALI can improve, but long-term outcomes remain unclear. Clinicians must now consider EVALI in patients presenting with respiratory, constitutional, and gastrointestinal complaints when a history of e-cigarette use is present.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- EVALI presents most commonly with a combination of respiratory, gastrointestinal, and constitutional symptoms. including shortness of breath, cough, nausea, vomiting, and fever.

- When considering EVALI, evaluate and treat for potential infectious causes of disease first.

- Corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy in EVALI, leading to improvement in oxygenation in many patients.

- Most of the reported cases of EVALI have occurred in patients who have vaped THC-containing products.

A 23-year-old woman presented to the emergency department complaining of “feeling terrible” for the past week. She described subjective fevers, chills, nonproductive cough, myalgias, and nausea. Her symptoms worsened on the day of presentation, with drenching night sweats, worsening myalgias, and generalized fatigue. She was unable to tolerate oral intake due to persistent nausea and had one episode of emesis.

While the initial constellation of symptoms suggests a viral syndrome, its progression over a week raises concern for something more ominous. Of her relatively nonspecific symptoms, prominent myalgias accompanied by a febrile illness may be most helpful. Fever, myalgias, and nonproductive cough are typical of seasonal influenza, although the presence of nausea and vomiting is atypical in adults. (Though this patient presented for care prior to the coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19] pandemic, depending on the timing of this presentation, COVID-19 should be considered.) Acute viral myositis can complicate many viral illnesses, such as influenza, coxsackie, and Epstein-Barr virus infections. Other infectious causes of myositis include systemic bacterial infections, spirochete diseases, and other viral infections, including dengue fever. Myalgias can also be a prominent feature of noninfectious systemic inflammatory conditions, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, polymyositis, and systemic vasculitis. Night sweats, while concerning, can be present in myriad conditions, and are not usually a discriminating symptom.

Her past medical history included depression, nephrolithiasis, frequent urinary tract infections, bladder spasms, and recurrent genital herpes simplex virus infection. Her medications included bupropion, microgestin, mirabegron, and valacyclovir. Her father had emphysema.

The patient was employed as a physical therapy assistant in a geriatric care center. Two weeks prior to presentation, she traveled from her home in North Carolina to visit a friend in Atlanta, Georgia. Shortly after the patient returned home, her friend in Atlanta became ill and was treated empirically for Legionella infection because of a recent outbreak in the area. One week prior to presentation, the patient and her boyfriend went on a day hike in the Smoky Mountains in North Carolina, but the patient did not recall any insect or tick bites. Her boyfriend had not been ill.

This history elucidates several potentially relevant medication and environmental exposures. Although bupropion can cause myalgias, neither it nor the other medications she is taking are likely to cause her constellation of symptoms. Her travel history to Atlanta suggests possible, though unconfirmed, exposure to Legionella pneumophila. Notably, she would have had to be exposed to the same source as her friend, since transmission of Legionella occurs via contaminated water and soil, not by human-to-human contact. Legionella infection typically causes a pneumonic process as described here, but her prominent myalgias would not be typical.

Her hike in the Smoky Mountains could have exposed her to several vector-borne diseases. Mosquito-borne dengue in North Carolina is extremely rare, but West Nile virus and eastern equine virus are found within that region. West Nile virus could cause a similar illness, although the cough and lack of neurologic symptoms would be unusual. Eastern equine virus can also cause similar symptoms but is quite rare.

Tick-borne illnesses that should be considered for this region include Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), ehrlichiosis, and babesiosis. These tend to present with nonspecific symptoms, but myalgias and fever are consistent features. Lyme disease this close to tick exposure usually presents with the characteristic erythema migrans rash, present in 80% of cases, with or without an influenza-like illness. Approximately 80% of patients do not recall a tick bite, even though a tick must be attached for 36 to 48 hours to transmit the spirochete. RMSF often presents with fever and myalgias, with arthralgias and headache, which are lacking in this case. The common, characteristic rash of blanching erythematous macules that convert to petechiae, starting at the ankles and wrists and spreading to the trunk, is often absent at presentation, showing up at days 3 to 5 in most patients.

Ehrlichiosis presents with an influenza-like illness, but up to half of patients also have nausea and cough. It can also present with a macular and petechial rash in a minority of patients. Lastly, babesiosis presents with an influenza-like illness and less often with cough or nausea. At this juncture, RMSF and ehrlichiosis are possibilities given the hiking history and symptoms, although the absence of a rash points more to ehrlichiosis.

The patient did not smoke cigarettes but had used a JUUL© vaporizer daily for the prior 2 years. Her last use was 1 week prior to admission. She used tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) pods purchased online in the vaporizer on a few occasions 1month prior but had not used THC since that time. She denied alcohol or other drug use.

Until recently, this important detail about vaping use would have been passed over without much consideration. Though reports of acute lung injury from vaping were published as early as 2017, it first came to national attention in August 2019 when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention posted a Health Advisory about severe lung injury associated with e-cigarette use. Of note, this advisory and subsequent published case series outline that e-cigarette, or vaping, use-associated lung injury (EVALI) may present with more than just respiratory symptoms. Most patients have respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, cough, or pleurisy, but many have gastrointestinal symptoms which may include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.1 Constitutional symptoms, including fever, chills, or weight loss, may also predominate.2 In some cases, the gastrointestinal symptoms precede the pulmonary symptoms. This patient’s symptoms warrant consideration of EVALI starting with a chest x-ray (CXR), which is usually abnormal in this disease.2

Physical examination revealed that the patient was alert, diaphoretic, and in mild respiratory distress. Temperature was 103.6 °F, blood pressure 129/75 mm Hg, pulse 130 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 per minute, and oxygen saturation 97% while breathing ambient air. Cardiac examination revealed tachycardia without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Lung exam revealed scattered rhonchi over the left posterior lower chest without egophony or dullness to percussion. Findings from abdominal, skin, neurologic, lymph node, and musculoskeletal exams were unremarkable.

Her fever, tachycardia, and respiratory distress point to a pulmonary process such as pneumonia or EVALI, even though she does not have definitive physical exam evidence of pneumonia. She presents with systemic inflammatory response syndrome without significant hypoxia and with borderline tachypnea, which could be related to sepsis or lactic acidosis from a systemic infection other than pneumonia. Her symptom complex could also be compatible with severe influenza infection. The absence of rash makes RMSF less likely.

Results of a complete blood count demonstrated a white blood cell count of 12,600/µL with 87% neutrophils. Results of a metabolic panel were normal, and a urine pregnancy test was negative. The electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia without other abnormalities. A CXR showed no evidence of acute cardiopulmonary abnormalities.

Her lab studies lack thrombocytopenia, which is often found in ehrlichiosis and RMSF. Leukopenia is also absent, which can be seen in Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis. The mild leukocytosis could be consistent with pneumonia, influenza, and EVALI and is not discriminating. The normal CXR goes against pneumonia or EVALI; however, 9% of patients with EVALI in one case series had a normal CXR, while computed tomography (CT) of the chest demonstrated bilateral ground-glass opacities.3 Chest CT is indicated in this case given the poor correlation of the CXR findings and this patient’s pronounced respiratory symptoms.

CT of the chest with contrast did not show a pulmonary embolism but revealed diffuse ground-glass opacities, predominantly in the dependent lower lobes (Figure 1).

Acute conditions with diffuse ground-glass opacities include mycoplasma, Pneumocystis jiroveci and viral pneumonias, pulmonary hemorrhage and edema, acute interstitial pneumonia, eosinophilic lung diseases, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Diffuse ground-glass opacities are also seen in almost all patients with EVALI. Though less likely, RMSF, babesiosis, and ehrlichiosis are not ruled out by these chest CT findings, since these disease entities can sometimes cause pulmonary manifestations, including pneumonia, pulmonary edema, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).4

In addition to Legionella and pneumococcal urinary antigen tests, respiratory viral panel, and blood cultures, it would be judicious to obtain HIV, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) testing; these last two tests are often markedly elevated in EVALI. The utility of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in suspected EVALI cases is not clearly defined, but should be considered in this case to ensure that infectious etiologies are not missed.2 Because of her potential environmental exposures, serologic testing for RMSF and ehrlichiosis should be sent.

Given the overlap in signs and symptoms of EVALI with various, potentially life-threatening infections, she should be empirically treated with antibiotics to cover for community-acquired pneumonia. Adding or even substituting doxycycline for a macrolide antibiotic in this regimen should be considered given that it would treat both RMSF and ehrlichiosis pending further test results. Delay in treating RMSF is associated with worse outcomes. If she is presenting during influenza season, she should also be treated with a neuraminidase inhibitor while awaiting influenza test results. Though the pathophysiology of EVALI is not entirely known, it appears to be inflammatory in nature. Most presumed cases have responded to corticosteroids, with improvement in oxygenation.2 Therefore, treatment with corticosteroids may be warranted to improve oxygenation while ruling out infectious processes.

The patient was admitted to the general medicine wards and started on ceftriaxone and azithromycin for empiric treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. On hospital day 2, a respiratory viral panel returned negative. Procalcitonin, HIV, and blood cultures all returned negative. An ESR was elevated at 86 mm/h. The patient continued to have daily fevers and developed erythematous, blanching macules on the neck, chest, back, and arms, which were noted to occur during febrile periods. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin were discontinued, and doxycycline was started. By hospital day 4, the patient’s oxygen saturation worsened to 86% on ambient air. She continued to have fevers and her cough worsened, with occasional blood-streaked sputum. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for closer monitoring.

On hospital day 5, she required intubation for worsening hypoxia. Bronchoscopy was performed, which revealed small mucosal crypts along the left mainstem bronchus. A small amount of bleeding after transbronchial biopsy of the left lower lobe was noted, which resolved with occlusion using the bronchoscope. BAL was performed, which revealed red, cloudy aspirate with 1,100 white blood cells (85% neutrophils) and 22,400 red blood cells. No bacteria were identified.

The patient has developed hypoxic respiratory failure despite appropriate antibiotics and negative cultures, increasing the likelihood of a noninfectious etiology. Her rash is not typical for RMSF, which usually starts as a macular or petechial rash at the ankles and wrists, and spreads centrally to the trunk. Rash is not typically associated with EVALI, and in this case, may represent miliaria caused by her fever.

The mucosal crypts seen on bronchoscopy are nonspecific, likely indicating inflammation from vaping. The BAL otherwise suggests diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), although sequential BAL aliquots are needed to confirm this diagnosis. DAH is usually caused by pulmonary capillaritis from vasculitis, Goodpasture disease, rheumatic diseases, or diffuse alveolar damage from toxins, infections, rheumatic diseases, or interstitial or organizing pneumonias. Diffuse alveolar damage is the pathologic finding of ARDS, which can be seen in severe cases of many of the conditions discussed, including EVALI, ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, sepsis, and community-acquired pneumonia.4

The BAL is most consistent with EVALI, which often shows elevated neutrophils. DAH due to vaping has also been reported.5 In patients with EVALI, varied pathologic findings of acute lung injury have been reported, including diffuse alveolar damage.6 At this point, laboratory evaluation for rheumatologic diseases and vasculitis should be obtained, and lung biopsy results reviewed. Given her clinical deterioration, treatment with intravenous corticosteroids for presumed EVALI is warranted.

Urine Legionella and Streptococcal pneumoniae antigen tests were negative. The patient was started on methylprednisolone 40 mg intravenously every 8 hours. Further testing included antinuclear antibodies, which was positive at 1:320, with a dense, fine speckled pattern. Perinuclear antineutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody, cytoplasmic antineutrophilic cytoplasmic autoantibody, myeloperoxidase, proteinase 3, double-stranded DNA, and glomerular basement membrane IgG were all negative. Transbronchial lung biopsy revealed severe acute lung injury consistent with diffuse alveolar damage. The pulmonary interstitium was mildly expanded by edema, with a moderate number of eosinophilic hyaline membranes. There were no eosinophils or evidence of hemorrhage, granulomas, or giant cells. These changes, within this clinical context, were diagnostic for EVALI.

The patient was intubated for 4 days and completed a course of empiric antibiotics as well as a 10-day course of prednisone. She was discharged on hospital day 17 on 2 L continuous oxygen via nasal cannula. Two days after discharge, she developed worsening dyspnea and chest pain and was readmitted with worsening ground-glass opacities, left upper lobe and right- sided pneumothoraces, and subcutaneous emphysema (Figure 2). She was treated with continuous oxygen to maintain oxygen saturation at 100% and eventually discharged home 3 days later on 3 L continuous oxygen. She attended pulmonary rehabilitation and was weaned off oxygen 2 months later, with marked improvement in aeration of both lungs (Figure 3). She continued to abstain from tobacco and THC products.

DISCUSSION

The first electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) device was developed in 2003 by a Chinese pharmacist and introduced to the American market in 2007.7 E-cigarettes produce an inhalable aerosol by heating a liquid containing a variety of chemicals, nicotine, and flavors, with or without other additives. Originally promoted as a safer nontobacco and cessation device by producers, e-cigarette sales grew at an annual rate of 115% between 2009 and 2012.8 E-cigarettes can also be used to deliver THC, the psychoactive component of cannabis.

Since the advent of e-cigarettes, their safety has been a topic of concern. In August 2019, the CDC announced 215 possible cases of severe pulmonary disease associated with the use of e-cigarette products that were reported by 25 state health departments.1 By February 2020, EVALI had affected more than 2,800 patients hospitalized across the United States.9

The presenting symptoms of EVALI are varied and nonspecific. The largest EVALI case series, published by Layden et al in 2020, included 98 patients who had a median duration of 6 days of symptoms prior to presentation.3 Respiratory symptoms occurred in 97% of patients, including shortness of breath, any chest pain, pleuritic chest pain, cough, and hemoptysis.3 Presentations also included a variety of gastrointestinal (77%) and constitutional (100%) symptoms, which most commonly included nausea, vomiting, and fever.3 Additional case series have supported a specific pattern of presentation, most commonly including pleuritic chest pain, nonproductive cough, or shortness of breath occurring days to weeks prior to presentation. Associated fatigue, fever, and tachycardia may be present, as well as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain, and in some cases, these have preceded respiratory symptoms.3,10,11

The vital signs and physical examination, laboratory, and imaging results associated with EVALI are also fairly nonspecific. The most common reason for hospitalization in EVALI is hypoxia, which can progress to acute respiratory failure requiring supplemental oxygen or, as in this case, mechanical ventilation. The most common laboratory finding is leukocytosis greater than 11,000/µL, with more than 80% neutrophils and an ESR greater than 30 mm/hr. In the Layden et al case series, 83% of patients had an abnormal CXR. All patients who underwent CT scan of the chest had bilateral ground-glass opacities, often with subpleural sparing.3 A minority of patients were found to have a pneumothorax, generally a late finding.3,12 Accordingly, the CDC now defines confirmed EVALI as use of e-cigarettes during the 90 days before symptom onset with the presence of pulmonary infiltrates (opacities on CXR or ground-glass opacities on chest CT), negative results on testing for all clinically indicated respiratory infections including respiratory viral panel and influenza PCR, and no alternative plausible diagnoses.13

The presumed etiology of EVALI is chemical exposure because no consistent infectious etiology has been identified.6 No consistent e-cigarette product, substance, or additive has been identified in all cases, nor has one product been directly linked to EVALI. However, the CDC recently announced that vitamin E acetate in vaping products appears to be associated with EVALI.9 In December 2019, Blount et al identified vitamin E acetate in BAL fluid samples from 48 of 51 EVALI patients.14 Additionally, while no other toxins were identified, 94% of samples contained THC or its metabolites or patients had reported vaping THC within 90 days preceding illness.14

The most effective treatment strategy for EVALI is still unknown. It is recommended to treat with empiric antibiotics for at least 48 hours (and antivirals during influenza season) if the history is unclear or if the patient is intubated or has severe hypoxemia.2 If antibiotic and/or antiviral therapies do not lead to clinical improvement, corticosteroids should be added, as they lead to improved oxygenation in many patients.2 Kalininskiy et al recommend initial administration of methylprednisolone 40 mg every 8 hours, with transition to oral prednisone to complete a 2-week course.2 Given rates of rehospitalization (2.7%) and death (2%) in EVALI, the CDC advises that patients should be clinically stable for 24 to 48 hours prior to discharge; that follow-up visits should be arranged within 48 hours of discharge; and that cases of EVALI should be reported to the state and local health departments.15 As seen in the case presented here, with time and continued abstinence from e-cigarette use, the pulmonary effects of EVALI can improve, but long-term outcomes remain unclear. Clinicians must now consider EVALI in patients presenting with respiratory, constitutional, and gastrointestinal complaints when a history of e-cigarette use is present.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- EVALI presents most commonly with a combination of respiratory, gastrointestinal, and constitutional symptoms. including shortness of breath, cough, nausea, vomiting, and fever.

- When considering EVALI, evaluate and treat for potential infectious causes of disease first.

- Corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy in EVALI, leading to improvement in oxygenation in many patients.

- Most of the reported cases of EVALI have occurred in patients who have vaped THC-containing products.

1. Schier JG, Meiman JG, Layden J, et al. Severe pulmonary disease associated with electronic-cigarette-product use – Interim guidance. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68(36):787-790. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6836e2

2. Kalininskiy A, Bach CT, Nacca NE, et al. E-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI): case series and diagnostic approach. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(12):1017-1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(19)30415-1

3. Layden JE, Ghinai I, Pray I, et al. Pulmonary illness related to e-cigarette use in Illiniois and Wisconsin – final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):903-916. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1911614

4. Faul JL, Doyle RL, Kao PN, Ruoss SJ. Tick-borne pulmonary disease: update on diagnosis and management. Chest. 1999;116(1):222-230. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.116.1.222

5. Agustin M, Yamamoto M, Cabrera F, Eusebio R. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage induced by vaping. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2018;2018:9724530. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9724530

6. Butt YM, Smith ML, Tazelaar HD, et al. Pathology of vaping-associated lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1780-1781. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc1913069

7. Office of the Surgeon General. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults. Chapter 1. Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2016. Accessed January 22, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/e-cigarettes/index.htm

8. Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. Background Paper on E-cigarettes (Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems). UCSF: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education; 2013. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/13p2b72n

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping. December 12, 2019. Updated February 25, 2020. Accessed January 22, 2020 and July 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

10. Davidson K, Brancato A, Heetkerks P, et al. Outbreak of e-cigarette-associated acute lipoid pneumonia—North Carolina, July-August 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(36);784-786. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6836e1

11. Maddock SD, Cirulis MM, Callahan SJ, et al. Pulmonary lipid-laden macrophages and vaping. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1488-1489. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc1912038

12. Henry TS, Kanne JP, Klingerman SJ. Imaging of vaping-associated lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1486-1487. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc1911995

13. Smoking and Tobacco Use: For State, Local, Territorial, and Tribal Health Departments. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed Jan 24, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease/health-departments/index.html

14. Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, et al. Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):697-705. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1916433

15. Evans ME, Twentyman E, Click ES, et al. Update: Interim guidance for health care professionals evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury and for reducing the risk for rehospitalization and death following hospital discharge — United States, December 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;68(5152):1189-1194. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm685152e2

1. Schier JG, Meiman JG, Layden J, et al. Severe pulmonary disease associated with electronic-cigarette-product use – Interim guidance. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019; 68(36):787-790. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6836e2

2. Kalininskiy A, Bach CT, Nacca NE, et al. E-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury (EVALI): case series and diagnostic approach. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(12):1017-1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(19)30415-1

3. Layden JE, Ghinai I, Pray I, et al. Pulmonary illness related to e-cigarette use in Illiniois and Wisconsin – final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):903-916. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1911614

4. Faul JL, Doyle RL, Kao PN, Ruoss SJ. Tick-borne pulmonary disease: update on diagnosis and management. Chest. 1999;116(1):222-230. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.116.1.222

5. Agustin M, Yamamoto M, Cabrera F, Eusebio R. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage induced by vaping. Case Rep Pulmonol. 2018;2018:9724530. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9724530

6. Butt YM, Smith ML, Tazelaar HD, et al. Pathology of vaping-associated lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1780-1781. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc1913069

7. Office of the Surgeon General. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults. Chapter 1. Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2016. Accessed January 22, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/e-cigarettes/index.htm

8. Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. Background Paper on E-cigarettes (Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems). UCSF: Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education; 2013. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/13p2b72n

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of lung injury associated with e-cigarette use, or vaping. December 12, 2019. Updated February 25, 2020. Accessed January 22, 2020 and July 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

10. Davidson K, Brancato A, Heetkerks P, et al. Outbreak of e-cigarette-associated acute lipoid pneumonia—North Carolina, July-August 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(36);784-786. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6836e1

11. Maddock SD, Cirulis MM, Callahan SJ, et al. Pulmonary lipid-laden macrophages and vaping. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1488-1489. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc1912038

12. Henry TS, Kanne JP, Klingerman SJ. Imaging of vaping-associated lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(15):1486-1487. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc1911995

13. Smoking and Tobacco Use: For State, Local, Territorial, and Tribal Health Departments. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed Jan 24, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease/health-departments/index.html

14. Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, et al. Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):697-705. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1916433

15. Evans ME, Twentyman E, Click ES, et al. Update: Interim guidance for health care professionals evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury and for reducing the risk for rehospitalization and death following hospital discharge — United States, December 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;68(5152):1189-1194. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm685152e2

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

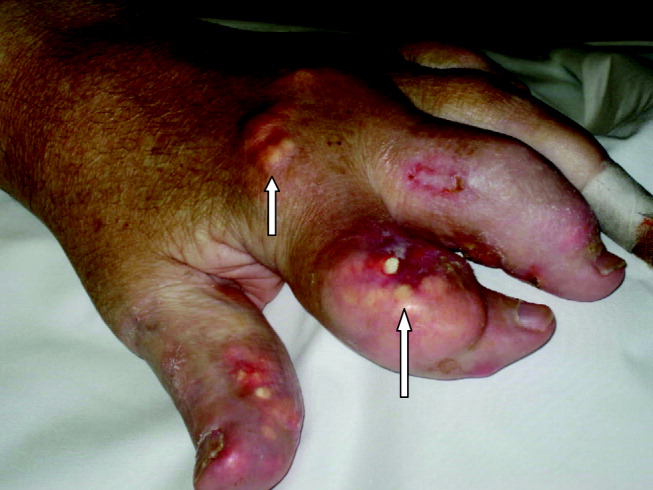

Primary livedo reticularis of the abdomen

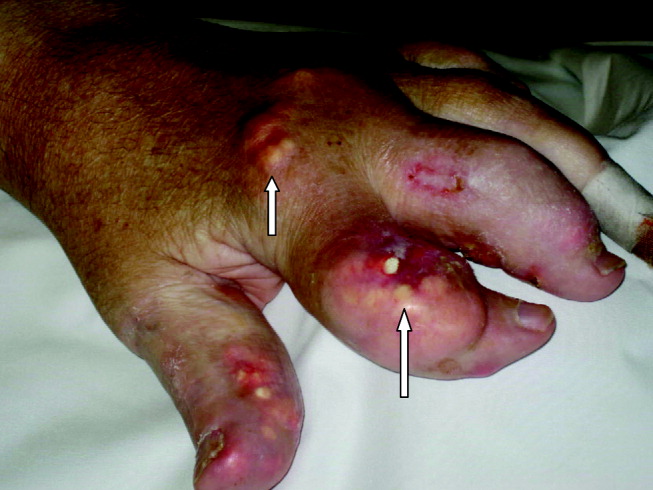

Livedo reticularis can be the manifestation of a wide range of conditions: hematologic and hypercoagulable states, embolic events, connective tissue disease, infection, vasculitis, malignancy, neurologic and endocrine conditions, and medication effects.1 Our patient had no recent history of vascular procedures or peripheral eosinophilia to suggest cholesterol embolization, and he had not recently started taking any new medications. His current medications included aspirin 81 mg, atorvastatin 40 mg, amlodipine 10 mg, and insulin glargine 20 units. Tests for cryoglobulin and antiphospholipid antibodies were negative. There was no evidence of malignancy, and evaluations for infectious and autoimmune diseases were negative.

Biopsy study of a skin lesion showed features consistent with livedo reticularis, with no evidence of vasculitis. The lesions resolved without definitive therapy by hospital day 3. This, in addition to other features of the lesions (eg, uniformity, unbroken reticular segments) and the extensive negative workup for systemic disease, suggested primary livedo reticularis.

CAUSES, TYPES, SUBTYPES

Livedo reticularis results from changes in the cutaneous microvasculature, composed of central arterioles that drain into an interconnecting, netlike venous plexus.1,2 Conditions such as arteriolar deoxygenation and venous plexus venodilation that result in a prominent venous plexus can give rise to clinical livedo reticularis.3

Primary livedo reticularis is thought to occur from spontaneous arteriolar vasospasm. It is a diagnosis of exclusion. An evaluation for underlying disease is important, as livedo reticularis can be associated with the range of conditions listed above.

In our patient, methamphetamine was considered a possible cause, but the findings of livedo reticularis were delayed and persisted longer than expected if they were drug-related.

Livedo racemosa

Distinguishing livedo reticularis from livedo racemosa is important. Livedo racemosa is always secondary and is often associated with antiphospholipid syndrome. It is present in 25% of cases of primary antiphospholipid syndrome and in up to 70% of cases of antiphospholipid syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.5 The reticular pattern of livedo racemosa is permanent and often has irregular and incomplete segments of reticular lattice, with a distribution that is more generalized, involving the trunk or buttocks (or both) in addition to the extremities.3,4 Consequently, a thorough history and physical examination are needed to guide additional workup.

- Gibbs MB, English JC 3rd, Zirwas MJ. Livedo reticularis: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:1009–1019.

- Kraemer M, Linden D, Berlit P. The spectrum of differential diagnosis in neurological patients with livedo reticularis and livedo racemosa. A literature review. J Neurol 2005; 252:1155–1166.

- Uthman IW, Khamashta MA. Livedo racemosa: a striking dermatological sign for the antiphospholipid syndrome. J Rheumatol 2006; 33:2379–2382.

- Dean SM. Livedo reticularis and related disorders. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2011; 13:179–191.

- Chadachan V, Dean SM, Eberhardt RT. Cutaneous changes in peripheral arterial vascular disease. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, Wolff K, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012.

Livedo reticularis can be the manifestation of a wide range of conditions: hematologic and hypercoagulable states, embolic events, connective tissue disease, infection, vasculitis, malignancy, neurologic and endocrine conditions, and medication effects.1 Our patient had no recent history of vascular procedures or peripheral eosinophilia to suggest cholesterol embolization, and he had not recently started taking any new medications. His current medications included aspirin 81 mg, atorvastatin 40 mg, amlodipine 10 mg, and insulin glargine 20 units. Tests for cryoglobulin and antiphospholipid antibodies were negative. There was no evidence of malignancy, and evaluations for infectious and autoimmune diseases were negative.

Biopsy study of a skin lesion showed features consistent with livedo reticularis, with no evidence of vasculitis. The lesions resolved without definitive therapy by hospital day 3. This, in addition to other features of the lesions (eg, uniformity, unbroken reticular segments) and the extensive negative workup for systemic disease, suggested primary livedo reticularis.

CAUSES, TYPES, SUBTYPES

Livedo reticularis results from changes in the cutaneous microvasculature, composed of central arterioles that drain into an interconnecting, netlike venous plexus.1,2 Conditions such as arteriolar deoxygenation and venous plexus venodilation that result in a prominent venous plexus can give rise to clinical livedo reticularis.3

Primary livedo reticularis is thought to occur from spontaneous arteriolar vasospasm. It is a diagnosis of exclusion. An evaluation for underlying disease is important, as livedo reticularis can be associated with the range of conditions listed above.

In our patient, methamphetamine was considered a possible cause, but the findings of livedo reticularis were delayed and persisted longer than expected if they were drug-related.

Livedo racemosa

Distinguishing livedo reticularis from livedo racemosa is important. Livedo racemosa is always secondary and is often associated with antiphospholipid syndrome. It is present in 25% of cases of primary antiphospholipid syndrome and in up to 70% of cases of antiphospholipid syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.5 The reticular pattern of livedo racemosa is permanent and often has irregular and incomplete segments of reticular lattice, with a distribution that is more generalized, involving the trunk or buttocks (or both) in addition to the extremities.3,4 Consequently, a thorough history and physical examination are needed to guide additional workup.

Livedo reticularis can be the manifestation of a wide range of conditions: hematologic and hypercoagulable states, embolic events, connective tissue disease, infection, vasculitis, malignancy, neurologic and endocrine conditions, and medication effects.1 Our patient had no recent history of vascular procedures or peripheral eosinophilia to suggest cholesterol embolization, and he had not recently started taking any new medications. His current medications included aspirin 81 mg, atorvastatin 40 mg, amlodipine 10 mg, and insulin glargine 20 units. Tests for cryoglobulin and antiphospholipid antibodies were negative. There was no evidence of malignancy, and evaluations for infectious and autoimmune diseases were negative.

Biopsy study of a skin lesion showed features consistent with livedo reticularis, with no evidence of vasculitis. The lesions resolved without definitive therapy by hospital day 3. This, in addition to other features of the lesions (eg, uniformity, unbroken reticular segments) and the extensive negative workup for systemic disease, suggested primary livedo reticularis.

CAUSES, TYPES, SUBTYPES

Livedo reticularis results from changes in the cutaneous microvasculature, composed of central arterioles that drain into an interconnecting, netlike venous plexus.1,2 Conditions such as arteriolar deoxygenation and venous plexus venodilation that result in a prominent venous plexus can give rise to clinical livedo reticularis.3

Primary livedo reticularis is thought to occur from spontaneous arteriolar vasospasm. It is a diagnosis of exclusion. An evaluation for underlying disease is important, as livedo reticularis can be associated with the range of conditions listed above.