User login

A Meal to Remember

A previously healthy 50‐year‐old man was eating a meal of rigatoni and shrimp at his favorite San Francisco restaurant when he suddenly developed severe pain in his throat followed a short time later by pleuritic chest pain localized to the anterior right chest. He completed his meal and then sought medical attention in the Emergency Department. He was in mild distress secondary to pain but his physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. His laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 15,300/mm3 with 86% neutrophils. A chest X‐ray, electrocardiogram, cardiac enzymes, and ventilation/perfusion scan were all normal. Because there was suspicion of an ingested foreign body, an abdominal radiograph was obtained which revealed a 2‐cm trapezoidal foreign body in the right lower quadrant (Figure 1; arrow). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed air in the mediastinum consistent with esophageal perforation (Figure 2). One day after admission a Hypaque esophagram showed trauma to the posterior cervical region of the esophagus, but no leak of contrast material into the mediastinum. The patient was managed conservatively with intravenous (IV) antibiotics and nothing by mouth. Stools were screened and 48 hours after admission the patient (painlessly) passed a piece of glass with a very sharp point (Figure 3) correlating in size and shape to the foreign body seen on the previous abdominal radiograph. The glass had apparently fallen into the patient's restaurant meal the night of admission. The patient did well and was discharged 6 days after admission. He asked the manager of his favorite restaurant to reimburse him the $200 copayment required for hospitalization required under his Preferred Provider Plan; the request was immediately honored.

Esophageal perforation is an emergency because of its high mortality rate. The most frequent cause is iatrogenic with instrumentation from endoscopic procedures. Other causes include foreign body ingestion (as in this case), trauma, operative injury, and tumor.1 Aggressive surgical intervention vs. conservative nonsurgical management remains a controversial topic.2 Early‐contained perforations can be managed successfully by limiting oral intake and giving parenteral antibiotics.3, 4 Any signs of sepsis, deterioration in the patient's condition, or uncontained rupture warrants immediate surgical intervention.14

- ,,, et al.Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation.Ann Thorac Surg.2004;77:1475–1483.

- ,,,.Esophageal perforation in adults.Ann Surg.2005;241(6):1016–1023.

- ,,.Esophageal perforation: emphasis of management.Ann Thorac Surg.1996;61:1447–1452

- ,,,.Nonoperative management of esophageal perforations.Ann Surg.1997;225(4):415–421.

A previously healthy 50‐year‐old man was eating a meal of rigatoni and shrimp at his favorite San Francisco restaurant when he suddenly developed severe pain in his throat followed a short time later by pleuritic chest pain localized to the anterior right chest. He completed his meal and then sought medical attention in the Emergency Department. He was in mild distress secondary to pain but his physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. His laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 15,300/mm3 with 86% neutrophils. A chest X‐ray, electrocardiogram, cardiac enzymes, and ventilation/perfusion scan were all normal. Because there was suspicion of an ingested foreign body, an abdominal radiograph was obtained which revealed a 2‐cm trapezoidal foreign body in the right lower quadrant (Figure 1; arrow). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed air in the mediastinum consistent with esophageal perforation (Figure 2). One day after admission a Hypaque esophagram showed trauma to the posterior cervical region of the esophagus, but no leak of contrast material into the mediastinum. The patient was managed conservatively with intravenous (IV) antibiotics and nothing by mouth. Stools were screened and 48 hours after admission the patient (painlessly) passed a piece of glass with a very sharp point (Figure 3) correlating in size and shape to the foreign body seen on the previous abdominal radiograph. The glass had apparently fallen into the patient's restaurant meal the night of admission. The patient did well and was discharged 6 days after admission. He asked the manager of his favorite restaurant to reimburse him the $200 copayment required for hospitalization required under his Preferred Provider Plan; the request was immediately honored.

Esophageal perforation is an emergency because of its high mortality rate. The most frequent cause is iatrogenic with instrumentation from endoscopic procedures. Other causes include foreign body ingestion (as in this case), trauma, operative injury, and tumor.1 Aggressive surgical intervention vs. conservative nonsurgical management remains a controversial topic.2 Early‐contained perforations can be managed successfully by limiting oral intake and giving parenteral antibiotics.3, 4 Any signs of sepsis, deterioration in the patient's condition, or uncontained rupture warrants immediate surgical intervention.14

A previously healthy 50‐year‐old man was eating a meal of rigatoni and shrimp at his favorite San Francisco restaurant when he suddenly developed severe pain in his throat followed a short time later by pleuritic chest pain localized to the anterior right chest. He completed his meal and then sought medical attention in the Emergency Department. He was in mild distress secondary to pain but his physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. His laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 15,300/mm3 with 86% neutrophils. A chest X‐ray, electrocardiogram, cardiac enzymes, and ventilation/perfusion scan were all normal. Because there was suspicion of an ingested foreign body, an abdominal radiograph was obtained which revealed a 2‐cm trapezoidal foreign body in the right lower quadrant (Figure 1; arrow). A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed air in the mediastinum consistent with esophageal perforation (Figure 2). One day after admission a Hypaque esophagram showed trauma to the posterior cervical region of the esophagus, but no leak of contrast material into the mediastinum. The patient was managed conservatively with intravenous (IV) antibiotics and nothing by mouth. Stools were screened and 48 hours after admission the patient (painlessly) passed a piece of glass with a very sharp point (Figure 3) correlating in size and shape to the foreign body seen on the previous abdominal radiograph. The glass had apparently fallen into the patient's restaurant meal the night of admission. The patient did well and was discharged 6 days after admission. He asked the manager of his favorite restaurant to reimburse him the $200 copayment required for hospitalization required under his Preferred Provider Plan; the request was immediately honored.

Esophageal perforation is an emergency because of its high mortality rate. The most frequent cause is iatrogenic with instrumentation from endoscopic procedures. Other causes include foreign body ingestion (as in this case), trauma, operative injury, and tumor.1 Aggressive surgical intervention vs. conservative nonsurgical management remains a controversial topic.2 Early‐contained perforations can be managed successfully by limiting oral intake and giving parenteral antibiotics.3, 4 Any signs of sepsis, deterioration in the patient's condition, or uncontained rupture warrants immediate surgical intervention.14

- ,,, et al.Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation.Ann Thorac Surg.2004;77:1475–1483.

- ,,,.Esophageal perforation in adults.Ann Surg.2005;241(6):1016–1023.

- ,,.Esophageal perforation: emphasis of management.Ann Thorac Surg.1996;61:1447–1452

- ,,,.Nonoperative management of esophageal perforations.Ann Surg.1997;225(4):415–421.

- ,,, et al.Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation.Ann Thorac Surg.2004;77:1475–1483.

- ,,,.Esophageal perforation in adults.Ann Surg.2005;241(6):1016–1023.

- ,,.Esophageal perforation: emphasis of management.Ann Thorac Surg.1996;61:1447–1452

- ,,,.Nonoperative management of esophageal perforations.Ann Surg.1997;225(4):415–421.

TB with Pott's Disease and Psoas Abscess

A 22‐year‐old man was referred from an outside hospital with 2 weeks of generalized weakness and difficulty ambulating. He also reported a 6‐month history of abdominal pain, right‐sided lumbar back pain, malaise, night sweats, cough, and weight loss of 30 kg. The patient was born in Mexico but had lived in the US for 10 years, working as a construction worker in northern California. He had had no prior medical care. On examination, the patient had a temperature of 40C, a heart rate of 109, and a respiratory rate of 20. His oxygen saturation was 97% on room air, and lung fields were clear bilaterally. Strength was slightly decreased in the right leg, with tenderness in the posterolateral aspect of the right thigh and thoracic lumbar spine.

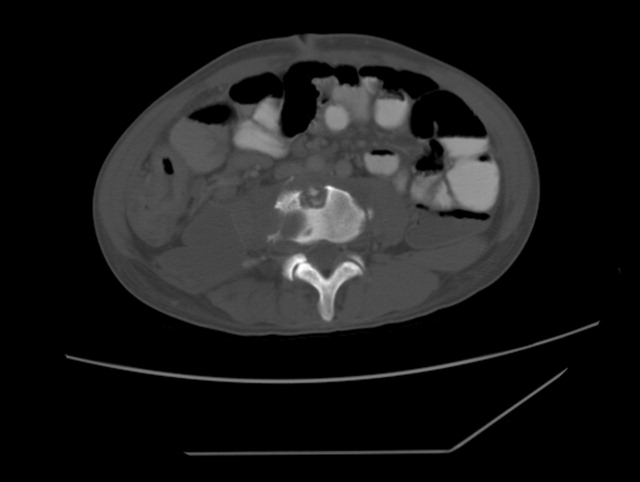

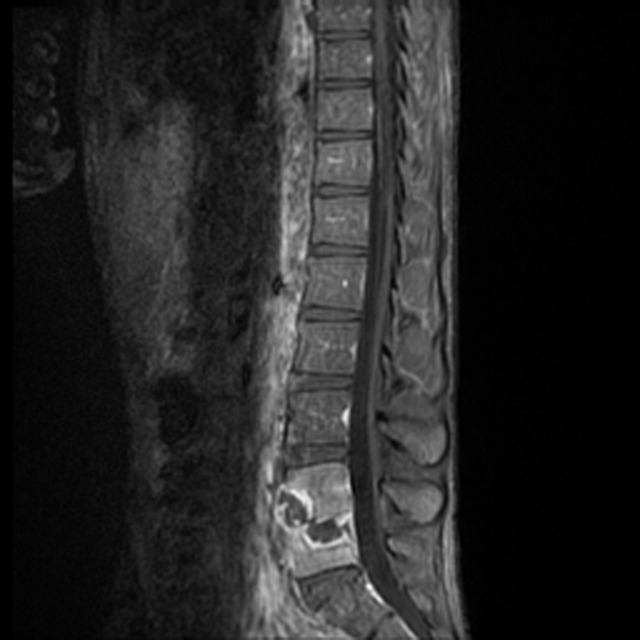

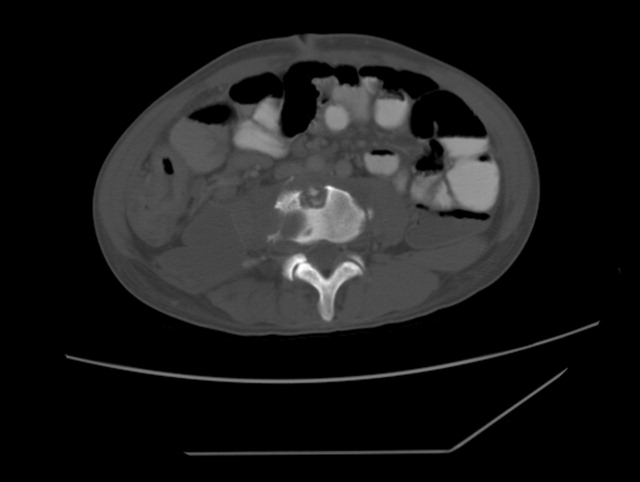

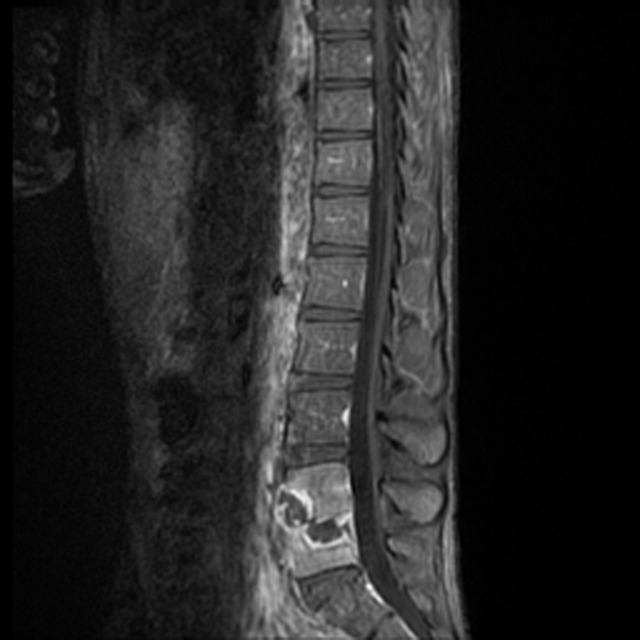

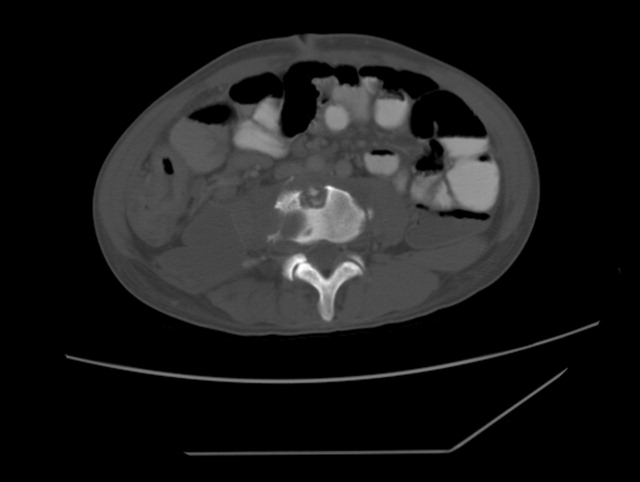

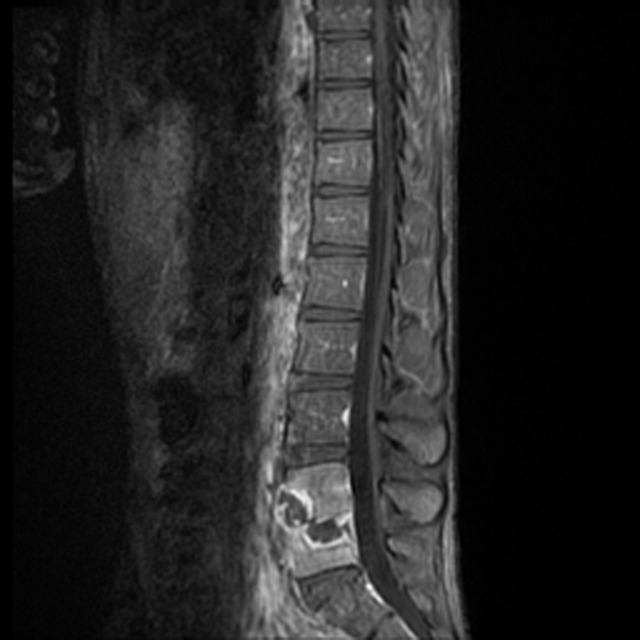

Radiograph of the chest showed bilateral upper lobe reticulonodular infiltrates, cavitation, and pleural thickening (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed innumerable pulmonary nodules throughout the mid and lower lungs, a loss of disc space between L4 and L5, and a large multiloculated abscess of the right iliacus and psoas muscles that extended into the right thigh (Figure 2). Longitudinal relaxation time (T1)‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine revealed vertebral destruction of L4 and L5 (Figure 3).

The patient underwent vertebrectomy of L4 and L5, anterior/posterior fixation and fusion from L4 to S1, and drainage of a large right‐sided psoas abscess. Acid‐fast bacilli were seen in abscess fluid and vertebral bone. Subsequently, the intraoperative cultures and 6 sequential sputum cultures all grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was begun on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol with a good clinical response, and subsequently transferred back to his referring hospital for continued medical care and rehabilitation.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis should be suspected in patients from a tuberculosis‐endemic country of origin. Bone and joint tuberculosis account for up to 35% of cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease) most commonly involves the anteroinferior aspect of vertebral bodies in the thoracic spine. Tuberculosis is a disease with diverse manifestations and can elude even the most astute physician if it is not considered as a diagnosis.

A 22‐year‐old man was referred from an outside hospital with 2 weeks of generalized weakness and difficulty ambulating. He also reported a 6‐month history of abdominal pain, right‐sided lumbar back pain, malaise, night sweats, cough, and weight loss of 30 kg. The patient was born in Mexico but had lived in the US for 10 years, working as a construction worker in northern California. He had had no prior medical care. On examination, the patient had a temperature of 40C, a heart rate of 109, and a respiratory rate of 20. His oxygen saturation was 97% on room air, and lung fields were clear bilaterally. Strength was slightly decreased in the right leg, with tenderness in the posterolateral aspect of the right thigh and thoracic lumbar spine.

Radiograph of the chest showed bilateral upper lobe reticulonodular infiltrates, cavitation, and pleural thickening (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed innumerable pulmonary nodules throughout the mid and lower lungs, a loss of disc space between L4 and L5, and a large multiloculated abscess of the right iliacus and psoas muscles that extended into the right thigh (Figure 2). Longitudinal relaxation time (T1)‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine revealed vertebral destruction of L4 and L5 (Figure 3).

The patient underwent vertebrectomy of L4 and L5, anterior/posterior fixation and fusion from L4 to S1, and drainage of a large right‐sided psoas abscess. Acid‐fast bacilli were seen in abscess fluid and vertebral bone. Subsequently, the intraoperative cultures and 6 sequential sputum cultures all grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was begun on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol with a good clinical response, and subsequently transferred back to his referring hospital for continued medical care and rehabilitation.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis should be suspected in patients from a tuberculosis‐endemic country of origin. Bone and joint tuberculosis account for up to 35% of cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease) most commonly involves the anteroinferior aspect of vertebral bodies in the thoracic spine. Tuberculosis is a disease with diverse manifestations and can elude even the most astute physician if it is not considered as a diagnosis.

A 22‐year‐old man was referred from an outside hospital with 2 weeks of generalized weakness and difficulty ambulating. He also reported a 6‐month history of abdominal pain, right‐sided lumbar back pain, malaise, night sweats, cough, and weight loss of 30 kg. The patient was born in Mexico but had lived in the US for 10 years, working as a construction worker in northern California. He had had no prior medical care. On examination, the patient had a temperature of 40C, a heart rate of 109, and a respiratory rate of 20. His oxygen saturation was 97% on room air, and lung fields were clear bilaterally. Strength was slightly decreased in the right leg, with tenderness in the posterolateral aspect of the right thigh and thoracic lumbar spine.

Radiograph of the chest showed bilateral upper lobe reticulonodular infiltrates, cavitation, and pleural thickening (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed innumerable pulmonary nodules throughout the mid and lower lungs, a loss of disc space between L4 and L5, and a large multiloculated abscess of the right iliacus and psoas muscles that extended into the right thigh (Figure 2). Longitudinal relaxation time (T1)‐weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine revealed vertebral destruction of L4 and L5 (Figure 3).

The patient underwent vertebrectomy of L4 and L5, anterior/posterior fixation and fusion from L4 to S1, and drainage of a large right‐sided psoas abscess. Acid‐fast bacilli were seen in abscess fluid and vertebral bone. Subsequently, the intraoperative cultures and 6 sequential sputum cultures all grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The patient was begun on rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol with a good clinical response, and subsequently transferred back to his referring hospital for continued medical care and rehabilitation.

Extrapulmonary manifestations of tuberculosis should be suspected in patients from a tuberculosis‐endemic country of origin. Bone and joint tuberculosis account for up to 35% of cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Spinal tuberculosis (Pott's disease) most commonly involves the anteroinferior aspect of vertebral bodies in the thoracic spine. Tuberculosis is a disease with diverse manifestations and can elude even the most astute physician if it is not considered as a diagnosis.