User login

Desquamating pustular rash

A 66-year-old man presented with burning pain and erythema over the left axilla, and pustules that had ruptured and crusted over. The rash also involved the right axilla, trunk, abdomen, and face.

He said the symptoms had developed 3 days after starting to use ciprofloxacin eye drops for eye redness and purulent discharge that had been diagnosed as bacterial conjunctivitis. He was taking no other new medications. He was afebrile.

The ciprofloxacin drops were stopped. The skin lesions were treated with emollients, topical steroids, and topical mupirocin. Improvement was noted 3 days into the hospitalization, as the lesions started to crust over and dry up and no new lesions were forming. The conjunctivitis improved with topical bacitracin ointment and prednisolone drops.

ACUTE GENERALIZED EXANTHEMATOUS PUSTULOSIS

The differential diagnosis of drug-related acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis includes Stevens-Johnson syndrome, pustular psoriasis, folliculitis, and varicella infection. The characteristic features of the rash and lesions and the temporal relationship between the start of ciprofloxacin eye drops and the development of symptoms, combined with rapid resolution of symptoms within days after discontinuing the drops, accompanied by skin biopsy study showing diffuse spongiosis with scattered eosinophils and a subcorneal pustule, confirmed the diagnosis of AGEP.

Key features of AGEP include numerous small, sterile, nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background with associated fever and sometimes neutrophilia and eosinophilia.1 It usually begins on the face or in the intertriginous areas and then spreads to the trunk and lower limbs with rare mucosal involvement.1 It can be associated with viral infections, but most reported cases are related to drug reactions.2

Our patient’s case was unusual because AGEP triggered by topical medications is rarely reported, especially with ophthalmic medications.3 Drugs most commonly implicated are antibiotics including penicillins, sulfonamides, and quinolones, but other drugs such as terbinafine, diltiazem, and hydroxychloroquine have also been associated.2

AGEP may present with extensive skin desquamation, as in our patient, sometimes with bullae formation and skin sloughing manifesting as AGEP with overlapping toxic epidermal necrolysis.4

Diagnosis entails a careful review of medications, attention to lesion morphology, compatible disease course, and a high index of suspicion. Treatment is supportive and consists of stopping the offending agent, wound care, and antipyretics. Evidence for the use of steroids is weak.5

TAKE-HOME POINTS

AGEP should be considered in sudden-onset pustular desquamating erythematous rash related to use of a new medication. It is important to be aware that topical and ophthalmic medications are possible triggers. A thorough medication review should be done. Antibiotics are the most commonly implicated medications. An alternative medication should be tried. Treatment is supportive, as the condition is usually self-limiting once the offending medication is discontinued. Rarely, extensive desquamation and bullae formation may occur, which may be a manifestation of overlap features with toxic epidermal necrolysis.

- Speeckaert MM, Speeckaert R, Lambert J, Brochez L. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: an overview of the clinical, immunological and diagnostic concepts. Eur J Dermatol 2010; 20(4):425–433. doi:10.1684/ejd.2010.0932

- Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—results of a multinational case–control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dermatol 2007; 157(5):989–996. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08156.x

- Beltran C, Vergier B, Doutre MS, Beylot C, Beylot-Barry M. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical application of Algipan. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2009; 136(10):709–712. French. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2008.10.042

- Peermohamed S, Haber RM. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis simulating toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 2011; 147(6):697–701. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.147

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17(8). pii:E1214. doi:10.3390/ijms17081214

A 66-year-old man presented with burning pain and erythema over the left axilla, and pustules that had ruptured and crusted over. The rash also involved the right axilla, trunk, abdomen, and face.

He said the symptoms had developed 3 days after starting to use ciprofloxacin eye drops for eye redness and purulent discharge that had been diagnosed as bacterial conjunctivitis. He was taking no other new medications. He was afebrile.

The ciprofloxacin drops were stopped. The skin lesions were treated with emollients, topical steroids, and topical mupirocin. Improvement was noted 3 days into the hospitalization, as the lesions started to crust over and dry up and no new lesions were forming. The conjunctivitis improved with topical bacitracin ointment and prednisolone drops.

ACUTE GENERALIZED EXANTHEMATOUS PUSTULOSIS

The differential diagnosis of drug-related acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis includes Stevens-Johnson syndrome, pustular psoriasis, folliculitis, and varicella infection. The characteristic features of the rash and lesions and the temporal relationship between the start of ciprofloxacin eye drops and the development of symptoms, combined with rapid resolution of symptoms within days after discontinuing the drops, accompanied by skin biopsy study showing diffuse spongiosis with scattered eosinophils and a subcorneal pustule, confirmed the diagnosis of AGEP.

Key features of AGEP include numerous small, sterile, nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background with associated fever and sometimes neutrophilia and eosinophilia.1 It usually begins on the face or in the intertriginous areas and then spreads to the trunk and lower limbs with rare mucosal involvement.1 It can be associated with viral infections, but most reported cases are related to drug reactions.2

Our patient’s case was unusual because AGEP triggered by topical medications is rarely reported, especially with ophthalmic medications.3 Drugs most commonly implicated are antibiotics including penicillins, sulfonamides, and quinolones, but other drugs such as terbinafine, diltiazem, and hydroxychloroquine have also been associated.2

AGEP may present with extensive skin desquamation, as in our patient, sometimes with bullae formation and skin sloughing manifesting as AGEP with overlapping toxic epidermal necrolysis.4

Diagnosis entails a careful review of medications, attention to lesion morphology, compatible disease course, and a high index of suspicion. Treatment is supportive and consists of stopping the offending agent, wound care, and antipyretics. Evidence for the use of steroids is weak.5

TAKE-HOME POINTS

AGEP should be considered in sudden-onset pustular desquamating erythematous rash related to use of a new medication. It is important to be aware that topical and ophthalmic medications are possible triggers. A thorough medication review should be done. Antibiotics are the most commonly implicated medications. An alternative medication should be tried. Treatment is supportive, as the condition is usually self-limiting once the offending medication is discontinued. Rarely, extensive desquamation and bullae formation may occur, which may be a manifestation of overlap features with toxic epidermal necrolysis.

A 66-year-old man presented with burning pain and erythema over the left axilla, and pustules that had ruptured and crusted over. The rash also involved the right axilla, trunk, abdomen, and face.

He said the symptoms had developed 3 days after starting to use ciprofloxacin eye drops for eye redness and purulent discharge that had been diagnosed as bacterial conjunctivitis. He was taking no other new medications. He was afebrile.

The ciprofloxacin drops were stopped. The skin lesions were treated with emollients, topical steroids, and topical mupirocin. Improvement was noted 3 days into the hospitalization, as the lesions started to crust over and dry up and no new lesions were forming. The conjunctivitis improved with topical bacitracin ointment and prednisolone drops.

ACUTE GENERALIZED EXANTHEMATOUS PUSTULOSIS

The differential diagnosis of drug-related acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis includes Stevens-Johnson syndrome, pustular psoriasis, folliculitis, and varicella infection. The characteristic features of the rash and lesions and the temporal relationship between the start of ciprofloxacin eye drops and the development of symptoms, combined with rapid resolution of symptoms within days after discontinuing the drops, accompanied by skin biopsy study showing diffuse spongiosis with scattered eosinophils and a subcorneal pustule, confirmed the diagnosis of AGEP.

Key features of AGEP include numerous small, sterile, nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background with associated fever and sometimes neutrophilia and eosinophilia.1 It usually begins on the face or in the intertriginous areas and then spreads to the trunk and lower limbs with rare mucosal involvement.1 It can be associated with viral infections, but most reported cases are related to drug reactions.2

Our patient’s case was unusual because AGEP triggered by topical medications is rarely reported, especially with ophthalmic medications.3 Drugs most commonly implicated are antibiotics including penicillins, sulfonamides, and quinolones, but other drugs such as terbinafine, diltiazem, and hydroxychloroquine have also been associated.2

AGEP may present with extensive skin desquamation, as in our patient, sometimes with bullae formation and skin sloughing manifesting as AGEP with overlapping toxic epidermal necrolysis.4

Diagnosis entails a careful review of medications, attention to lesion morphology, compatible disease course, and a high index of suspicion. Treatment is supportive and consists of stopping the offending agent, wound care, and antipyretics. Evidence for the use of steroids is weak.5

TAKE-HOME POINTS

AGEP should be considered in sudden-onset pustular desquamating erythematous rash related to use of a new medication. It is important to be aware that topical and ophthalmic medications are possible triggers. A thorough medication review should be done. Antibiotics are the most commonly implicated medications. An alternative medication should be tried. Treatment is supportive, as the condition is usually self-limiting once the offending medication is discontinued. Rarely, extensive desquamation and bullae formation may occur, which may be a manifestation of overlap features with toxic epidermal necrolysis.

- Speeckaert MM, Speeckaert R, Lambert J, Brochez L. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: an overview of the clinical, immunological and diagnostic concepts. Eur J Dermatol 2010; 20(4):425–433. doi:10.1684/ejd.2010.0932

- Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—results of a multinational case–control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dermatol 2007; 157(5):989–996. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08156.x

- Beltran C, Vergier B, Doutre MS, Beylot C, Beylot-Barry M. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical application of Algipan. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2009; 136(10):709–712. French. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2008.10.042

- Peermohamed S, Haber RM. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis simulating toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 2011; 147(6):697–701. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.147

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17(8). pii:E1214. doi:10.3390/ijms17081214

- Speeckaert MM, Speeckaert R, Lambert J, Brochez L. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: an overview of the clinical, immunological and diagnostic concepts. Eur J Dermatol 2010; 20(4):425–433. doi:10.1684/ejd.2010.0932

- Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—results of a multinational case–control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dermatol 2007; 157(5):989–996. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08156.x

- Beltran C, Vergier B, Doutre MS, Beylot C, Beylot-Barry M. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical application of Algipan. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2009; 136(10):709–712. French. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2008.10.042

- Peermohamed S, Haber RM. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis simulating toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 2011; 147(6):697–701. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.147

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17(8). pii:E1214. doi:10.3390/ijms17081214

Hypothermia and severe first-degree heart block

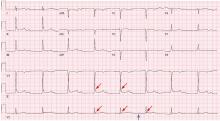

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

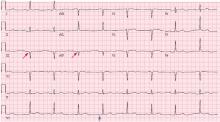

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.