User login

Hypothermia and severe first-degree heart block

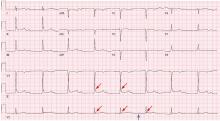

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

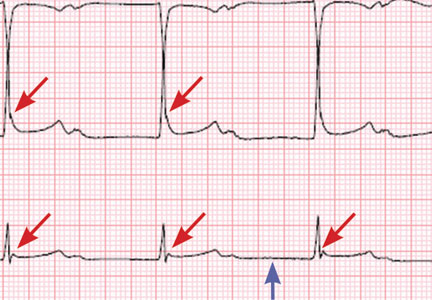

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

A 96-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes, and dementia was found unresponsive in her nursing home and was transferred to the hospital.

At presentation to the hospital, her blood pressure was 76/43 mm Hg, heart rate 42 beats per minute, rectal temperature 31.6°C (88.8°F), and blood glucose 36 mg/dL.

Causes of secondary hypothermia were sought. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the head showed no acute intracranial abnormalities. Tests for adrenal insufficiency and hypothyroidism were negative.

HYPOTHERMIA AND THE ECG

Hypothermia can produce a number of changes on the ECG. At the start of hypothermia, a stress reaction is induced, resulting in sinus tachycardia. But when the temperature goes below 32°C, sinus bradycardia ensues,1 resulting in various degrees of heart block.2 In our patient, a severely prolonged PR interval resulted in first-degree heart block.

Other findings on ECG associated with hypothermia include atrial fibrillation, widening of the P and T waves, prolonging of the QT interval, and widening of the QRS interval. Progressive widening of the QRS interval can predispose to ventricular fibrillation.1,3

An Osborn or J wave is a wave found between the end of the QRS and the beginning of the ST segment and is usually seen on the inferior and lateral precordial leads. It is found in as many as 80% of patients when the body temperature is below 30°C.1,3,4

Although Osborn waves are a common finding in hypothermia, they are also seen in electrolyte imbalances such as hypercalcemia and in central nervous system diseases.5,6 Hypothermia-associated changes on ECG are usually readily reversible with rewarming.1

TAKE-HOME MESSAGES

The ECG should always be interpreted in the proper clinical context and, whenever possible, compared with a previous ECG. It is prudent to always consider potentially reversible triggers of hypothermia other than environmental exposure such as hypothyroidism, infection, adrenal insufficiency, ketoacidosis, medication side effects, and alcohol use.

Hypothermia, especially in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, can lead to bradycardia and varying degrees of heart block.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.

- Alhaddad IA, Khalil M, Brown EJ Jr. Osborn waves of hypothermia. Circulation 2000; 101:E233–E244.

- Bashour TT, Gualberto A, Ryan C. Atrioventricular block in accidental hypothermia—a case report. Angiology 1989; 40:63–66.

- Okada M, Nishimura F, Yoshino H, Kimura M, Ogino T. The J wave in accidental hypothermia. J Electrocardiol 1983; 16:23–28.

- Kukla P, Baranchuk A, Jastrzebski M, Zabojszcz M, Bryniarski L. Electrocardiographic landmarks of hypothermia. Kardiol Pol 2013; 71:1188–1189.

- Maruyama M, Kobayashi Y, Kodani E, et al. Osborn waves: history and significance. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2004; 4:33–39.

- Sheikh AM, Hurst JW. Osborn waves in the electrocardiogram, hypothermia not due to exposure, and death due to diabetic ketoacidosis. Clin Cardiol 2003; 26:555–560.