User login

Osmotic demyelination syndrome due to hyperosmolar hyperglycemia

A 55-year-old man with a 20-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital after presenting to the emergency department with an acute change in mental status. Three days earlier, he had begun to feel abdominal discomfort and dizziness, which gradually worsened.

On presentation, his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 13 out of 15 (eye-opening response 3 of 4, verbal response 4 of 5, motor response 6 of 6), his blood pressure was 221/114 mm Hg, and other vital signs were normal. Physical examination including a neurologic examination was normal. No gait abnormality or ataxia was noted.

When asked about current medications, he said that 2 years earlier he had missed an appointment with his primary care physician and so had never obtained refills of his diabetes medications.

Results of laboratory testing were as follows:

- Blood glucose 1,011 mg/dL (reference range 65–110)

- Hemoglobin A1c 17.8% (4%–5.6%)

- Sodium 126 mmol/L (135–145)

- Sodium corrected for serum glucose 141 mmol/L

- Potassium 3.2 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Blood urea nitrogen 43.8 mg/dL (8–21)

- Calculated serum osmolality 324 mosm/kg (275–295).

Blood gas analysis showed no acidosis. Tests for urinary and serum ketones were negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast was normal.

Based on the results of the evaluation, the patient’s condition was diagnosed as a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, presumably from dehydration and noncompliance with diabetes medications. His altered mental status was also attributed to this diagnosis. He was started on aggressive hydration and insulin infusion to correct the blood glucose level. Repeat laboratory testing 7 hours after admission revealed a blood glucose of 49 mg/dL, sodium 148 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 43 mg/dL, and calculated serum osmolality 290 mosm/kg.

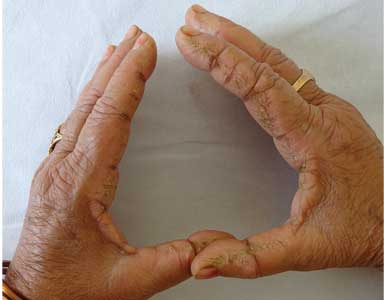

The insulin infusion was suspended, and glucose infusion was started. With this treatment, his blood glucose level stabilized, but his Glasgow Coma Scale score was unchanged from the time of presentation. A neurologic examination at this time showed bilateral dysmetria. Cranial nerves were normal. Motor examination showed normal tone with a Medical Research Council score of 5 of 5 in all extremities. Sensory examination revealed a glove-and-stocking pattern of loss of vibratory sensation. Tendon reflexes were normal except for diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses.

OSMOTIC DEMYELINATION SYNDROME

Central pontine myelinolysis is a pivotal manifestation of the syndrome and is characterized by progressive lethargy, quadriparesis, dysarthria, ophthalmoplegia, dysphasia, ataxia, and reflex changes. Clinical symptoms of extrapontine myelinolysis are variable.4

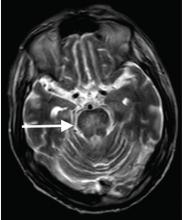

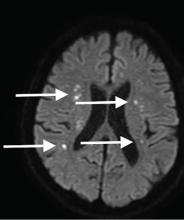

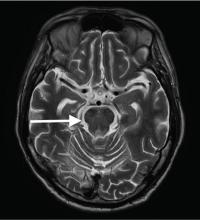

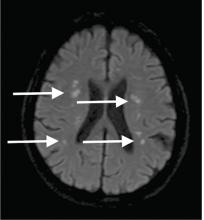

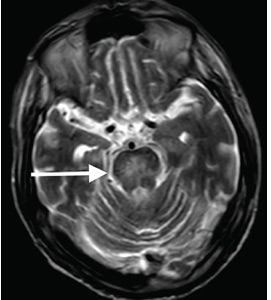

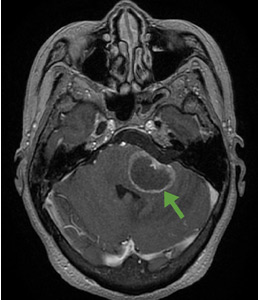

Although CT may underestimate osmotic demyelination syndrome, the typical radiologic findings on brain MRI are hyperintense lesions in the central pons or associated extrapontine structures on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences.4

A precise definition of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia does not exist. The Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care suggested the following features: a measured osmolality of 320 mosm/kg or higher, a blood glucose level of 541 mg/dL or higher, severe dehydration, and feeling unwell.5

Our patient’s clinical course and high hemoglobin A1c suggested prolonged hyperglycemia and high serum osmolality before his admission. After his admission, aggressive hydration and insulin therapy corrected the hyperglycemia and serum osmolality too rapidly for his brain cells to adjust to the change. It was reasonable to suspect a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state as one of the main causes of his mental status change and ataxia. This, along with lack of improvement in his impaired metal status and new-onset ataxia despite treatment, led to suspicion of osmotic demyelination syndrome. His diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses more likely represented diabetic neuropathy rather than osmotic demyelination syndrome.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome has seldom been reported as a complication of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia.6–13 And extrapontine myelinolysis with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia is extremely rare, with only 2 reports to date to the best of our knowledge.6,10

There is no specific treatment for osmotic demyelination syndrome except for supportive care and treatment of coexisting conditions. Once an osmotic derangement is identified, we recommend correcting chronically elevated serum glucose values gradually to avoid overtreatment, just as we would do with elevated serum sodium levels. Changes in neurologic findings, serum blood glucose level, and serum osmolality should be followed closely. A review showed that a favorable recovery from osmotic demyelination syndrome is possible even with severe neurologic deficits.4

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome is a rare but severe complication of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

- Physicians should be aware not only of changes in serum sodium, but also of changes in serum osmolality and serum glucose.

- When a new-onset neurologic deficit is found during treatment of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, suspect osmotic demyelination syndrome, monitor changes in serum osmolality, and consider brain MRI.

- Brown WD. Osmotic demyelination disorders: central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis. Curr Opin Neurol 2000; 13(6):691–697. pmid:11148672

- Laureno R, Karp BI. Myelinolysis after correction of hyponatraemia. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126(1):57–62. pmid:8992924

- Adams RD, Victor M, Mancall EL. Central pontine myelinolysis: a hitherto undescribed disease occurring in alcoholic and malnourished patients. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1959; 81(2):154–172. pmid:13616772

- Singh TD, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2014; 21(12):1443–1450. doi:10.1111/ene.12571

- Scott AR; Joint British Diabetes Societies (JBDS) for Inpatient Care; JBDS Hyperosmolar Hyperglycaemic Guidelines Group. Management of hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state in adults with diabetes. Diabet Med 2015; 32(6):714–724. doi:10.1111/dme.12757

- McComb RD, Pfeiffer RF, Casey JH, Wolcott G, Till DJ. Lateral pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis associated with hypernatremia and hyperglycemia. Clin Neuropathol 1989; 8(6):284–288. pmid:2695277

- O’Malley G, Moran C, Draman MS, et al. Central pontine myelinolysis complicating treatment of the hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2008; 45(pt 4):440–443. doi:10.1258/acb.2008.007171

- Burns JD, Kosa SC, Wijdicks EF. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia and consistently normal serum sodium. Neurocrit Care 2009; 11(2):251–254. doi:10.1007/s12028-009-9241-9

- Mao S, Liu Z, Ding M. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with epilepsia partialis continua and hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2011; 48(pt 1):79–82. doi:10.1258/acb.2010.010152. Epub 2010 Nov 23.

- Guerrero WR, Dababneh H, Nadeau SE. Hemiparesis, encephalopathy, and extrapontine osmotic myelinolysis in the setting of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20(6):894–896. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2012.05.045

- Hegazi MO, Mashankar A. Central pontine myelinolysis in the hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state. Med Princ Pract 2013; 22(1):96–99. doi:10.1159/000341718

- Rodríguez-Velver KV, Soto-Garcia AJ, Zapata-Rivera MA, Montes-Villarreal J, Villarreal-Pérez JZ, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R. Osmotic demyelination syndrome as the initial manifestation of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. Case Rep Neurol Med 2014; 2014:652523. doi:10.1155/2014/652523

- Chang YM. Central pontine myelinolysis associated with diabetic hyperglycemia. JSM Clin Case Rep 2014; 2(6):1059.

A 55-year-old man with a 20-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital after presenting to the emergency department with an acute change in mental status. Three days earlier, he had begun to feel abdominal discomfort and dizziness, which gradually worsened.

On presentation, his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 13 out of 15 (eye-opening response 3 of 4, verbal response 4 of 5, motor response 6 of 6), his blood pressure was 221/114 mm Hg, and other vital signs were normal. Physical examination including a neurologic examination was normal. No gait abnormality or ataxia was noted.

When asked about current medications, he said that 2 years earlier he had missed an appointment with his primary care physician and so had never obtained refills of his diabetes medications.

Results of laboratory testing were as follows:

- Blood glucose 1,011 mg/dL (reference range 65–110)

- Hemoglobin A1c 17.8% (4%–5.6%)

- Sodium 126 mmol/L (135–145)

- Sodium corrected for serum glucose 141 mmol/L

- Potassium 3.2 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Blood urea nitrogen 43.8 mg/dL (8–21)

- Calculated serum osmolality 324 mosm/kg (275–295).

Blood gas analysis showed no acidosis. Tests for urinary and serum ketones were negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast was normal.

Based on the results of the evaluation, the patient’s condition was diagnosed as a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, presumably from dehydration and noncompliance with diabetes medications. His altered mental status was also attributed to this diagnosis. He was started on aggressive hydration and insulin infusion to correct the blood glucose level. Repeat laboratory testing 7 hours after admission revealed a blood glucose of 49 mg/dL, sodium 148 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 43 mg/dL, and calculated serum osmolality 290 mosm/kg.

The insulin infusion was suspended, and glucose infusion was started. With this treatment, his blood glucose level stabilized, but his Glasgow Coma Scale score was unchanged from the time of presentation. A neurologic examination at this time showed bilateral dysmetria. Cranial nerves were normal. Motor examination showed normal tone with a Medical Research Council score of 5 of 5 in all extremities. Sensory examination revealed a glove-and-stocking pattern of loss of vibratory sensation. Tendon reflexes were normal except for diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses.

OSMOTIC DEMYELINATION SYNDROME

Central pontine myelinolysis is a pivotal manifestation of the syndrome and is characterized by progressive lethargy, quadriparesis, dysarthria, ophthalmoplegia, dysphasia, ataxia, and reflex changes. Clinical symptoms of extrapontine myelinolysis are variable.4

Although CT may underestimate osmotic demyelination syndrome, the typical radiologic findings on brain MRI are hyperintense lesions in the central pons or associated extrapontine structures on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences.4

A precise definition of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia does not exist. The Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care suggested the following features: a measured osmolality of 320 mosm/kg or higher, a blood glucose level of 541 mg/dL or higher, severe dehydration, and feeling unwell.5

Our patient’s clinical course and high hemoglobin A1c suggested prolonged hyperglycemia and high serum osmolality before his admission. After his admission, aggressive hydration and insulin therapy corrected the hyperglycemia and serum osmolality too rapidly for his brain cells to adjust to the change. It was reasonable to suspect a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state as one of the main causes of his mental status change and ataxia. This, along with lack of improvement in his impaired metal status and new-onset ataxia despite treatment, led to suspicion of osmotic demyelination syndrome. His diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses more likely represented diabetic neuropathy rather than osmotic demyelination syndrome.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome has seldom been reported as a complication of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia.6–13 And extrapontine myelinolysis with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia is extremely rare, with only 2 reports to date to the best of our knowledge.6,10

There is no specific treatment for osmotic demyelination syndrome except for supportive care and treatment of coexisting conditions. Once an osmotic derangement is identified, we recommend correcting chronically elevated serum glucose values gradually to avoid overtreatment, just as we would do with elevated serum sodium levels. Changes in neurologic findings, serum blood glucose level, and serum osmolality should be followed closely. A review showed that a favorable recovery from osmotic demyelination syndrome is possible even with severe neurologic deficits.4

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome is a rare but severe complication of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

- Physicians should be aware not only of changes in serum sodium, but also of changes in serum osmolality and serum glucose.

- When a new-onset neurologic deficit is found during treatment of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, suspect osmotic demyelination syndrome, monitor changes in serum osmolality, and consider brain MRI.

A 55-year-old man with a 20-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital after presenting to the emergency department with an acute change in mental status. Three days earlier, he had begun to feel abdominal discomfort and dizziness, which gradually worsened.

On presentation, his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 13 out of 15 (eye-opening response 3 of 4, verbal response 4 of 5, motor response 6 of 6), his blood pressure was 221/114 mm Hg, and other vital signs were normal. Physical examination including a neurologic examination was normal. No gait abnormality or ataxia was noted.

When asked about current medications, he said that 2 years earlier he had missed an appointment with his primary care physician and so had never obtained refills of his diabetes medications.

Results of laboratory testing were as follows:

- Blood glucose 1,011 mg/dL (reference range 65–110)

- Hemoglobin A1c 17.8% (4%–5.6%)

- Sodium 126 mmol/L (135–145)

- Sodium corrected for serum glucose 141 mmol/L

- Potassium 3.2 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Blood urea nitrogen 43.8 mg/dL (8–21)

- Calculated serum osmolality 324 mosm/kg (275–295).

Blood gas analysis showed no acidosis. Tests for urinary and serum ketones were negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the head without contrast was normal.

Based on the results of the evaluation, the patient’s condition was diagnosed as a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, presumably from dehydration and noncompliance with diabetes medications. His altered mental status was also attributed to this diagnosis. He was started on aggressive hydration and insulin infusion to correct the blood glucose level. Repeat laboratory testing 7 hours after admission revealed a blood glucose of 49 mg/dL, sodium 148 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 43 mg/dL, and calculated serum osmolality 290 mosm/kg.

The insulin infusion was suspended, and glucose infusion was started. With this treatment, his blood glucose level stabilized, but his Glasgow Coma Scale score was unchanged from the time of presentation. A neurologic examination at this time showed bilateral dysmetria. Cranial nerves were normal. Motor examination showed normal tone with a Medical Research Council score of 5 of 5 in all extremities. Sensory examination revealed a glove-and-stocking pattern of loss of vibratory sensation. Tendon reflexes were normal except for diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses.

OSMOTIC DEMYELINATION SYNDROME

Central pontine myelinolysis is a pivotal manifestation of the syndrome and is characterized by progressive lethargy, quadriparesis, dysarthria, ophthalmoplegia, dysphasia, ataxia, and reflex changes. Clinical symptoms of extrapontine myelinolysis are variable.4

Although CT may underestimate osmotic demyelination syndrome, the typical radiologic findings on brain MRI are hyperintense lesions in the central pons or associated extrapontine structures on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences.4

A precise definition of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia does not exist. The Joint British Diabetes Societies for Inpatient Care suggested the following features: a measured osmolality of 320 mosm/kg or higher, a blood glucose level of 541 mg/dL or higher, severe dehydration, and feeling unwell.5

Our patient’s clinical course and high hemoglobin A1c suggested prolonged hyperglycemia and high serum osmolality before his admission. After his admission, aggressive hydration and insulin therapy corrected the hyperglycemia and serum osmolality too rapidly for his brain cells to adjust to the change. It was reasonable to suspect a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state as one of the main causes of his mental status change and ataxia. This, along with lack of improvement in his impaired metal status and new-onset ataxia despite treatment, led to suspicion of osmotic demyelination syndrome. His diminished bilateral knee-jerk and ankle-jerk responses more likely represented diabetic neuropathy rather than osmotic demyelination syndrome.

Osmotic demyelination syndrome has seldom been reported as a complication of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia.6–13 And extrapontine myelinolysis with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia is extremely rare, with only 2 reports to date to the best of our knowledge.6,10

There is no specific treatment for osmotic demyelination syndrome except for supportive care and treatment of coexisting conditions. Once an osmotic derangement is identified, we recommend correcting chronically elevated serum glucose values gradually to avoid overtreatment, just as we would do with elevated serum sodium levels. Changes in neurologic findings, serum blood glucose level, and serum osmolality should be followed closely. A review showed that a favorable recovery from osmotic demyelination syndrome is possible even with severe neurologic deficits.4

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

- Osmotic demyelination syndrome is a rare but severe complication of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state.

- Physicians should be aware not only of changes in serum sodium, but also of changes in serum osmolality and serum glucose.

- When a new-onset neurologic deficit is found during treatment of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, suspect osmotic demyelination syndrome, monitor changes in serum osmolality, and consider brain MRI.

- Brown WD. Osmotic demyelination disorders: central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis. Curr Opin Neurol 2000; 13(6):691–697. pmid:11148672

- Laureno R, Karp BI. Myelinolysis after correction of hyponatraemia. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126(1):57–62. pmid:8992924

- Adams RD, Victor M, Mancall EL. Central pontine myelinolysis: a hitherto undescribed disease occurring in alcoholic and malnourished patients. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1959; 81(2):154–172. pmid:13616772

- Singh TD, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2014; 21(12):1443–1450. doi:10.1111/ene.12571

- Scott AR; Joint British Diabetes Societies (JBDS) for Inpatient Care; JBDS Hyperosmolar Hyperglycaemic Guidelines Group. Management of hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state in adults with diabetes. Diabet Med 2015; 32(6):714–724. doi:10.1111/dme.12757

- McComb RD, Pfeiffer RF, Casey JH, Wolcott G, Till DJ. Lateral pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis associated with hypernatremia and hyperglycemia. Clin Neuropathol 1989; 8(6):284–288. pmid:2695277

- O’Malley G, Moran C, Draman MS, et al. Central pontine myelinolysis complicating treatment of the hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2008; 45(pt 4):440–443. doi:10.1258/acb.2008.007171

- Burns JD, Kosa SC, Wijdicks EF. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia and consistently normal serum sodium. Neurocrit Care 2009; 11(2):251–254. doi:10.1007/s12028-009-9241-9

- Mao S, Liu Z, Ding M. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with epilepsia partialis continua and hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2011; 48(pt 1):79–82. doi:10.1258/acb.2010.010152. Epub 2010 Nov 23.

- Guerrero WR, Dababneh H, Nadeau SE. Hemiparesis, encephalopathy, and extrapontine osmotic myelinolysis in the setting of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20(6):894–896. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2012.05.045

- Hegazi MO, Mashankar A. Central pontine myelinolysis in the hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state. Med Princ Pract 2013; 22(1):96–99. doi:10.1159/000341718

- Rodríguez-Velver KV, Soto-Garcia AJ, Zapata-Rivera MA, Montes-Villarreal J, Villarreal-Pérez JZ, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R. Osmotic demyelination syndrome as the initial manifestation of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. Case Rep Neurol Med 2014; 2014:652523. doi:10.1155/2014/652523

- Chang YM. Central pontine myelinolysis associated with diabetic hyperglycemia. JSM Clin Case Rep 2014; 2(6):1059.

- Brown WD. Osmotic demyelination disorders: central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis. Curr Opin Neurol 2000; 13(6):691–697. pmid:11148672

- Laureno R, Karp BI. Myelinolysis after correction of hyponatraemia. Ann Intern Med 1997; 126(1):57–62. pmid:8992924

- Adams RD, Victor M, Mancall EL. Central pontine myelinolysis: a hitherto undescribed disease occurring in alcoholic and malnourished patients. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1959; 81(2):154–172. pmid:13616772

- Singh TD, Fugate JE, Rabinstein AA. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2014; 21(12):1443–1450. doi:10.1111/ene.12571

- Scott AR; Joint British Diabetes Societies (JBDS) for Inpatient Care; JBDS Hyperosmolar Hyperglycaemic Guidelines Group. Management of hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state in adults with diabetes. Diabet Med 2015; 32(6):714–724. doi:10.1111/dme.12757

- McComb RD, Pfeiffer RF, Casey JH, Wolcott G, Till DJ. Lateral pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis associated with hypernatremia and hyperglycemia. Clin Neuropathol 1989; 8(6):284–288. pmid:2695277

- O’Malley G, Moran C, Draman MS, et al. Central pontine myelinolysis complicating treatment of the hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2008; 45(pt 4):440–443. doi:10.1258/acb.2008.007171

- Burns JD, Kosa SC, Wijdicks EF. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with hyperosmolar hyperglycemia and consistently normal serum sodium. Neurocrit Care 2009; 11(2):251–254. doi:10.1007/s12028-009-9241-9

- Mao S, Liu Z, Ding M. Central pontine myelinolysis in a patient with epilepsia partialis continua and hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state. Ann Clin Biochem 2011; 48(pt 1):79–82. doi:10.1258/acb.2010.010152. Epub 2010 Nov 23.

- Guerrero WR, Dababneh H, Nadeau SE. Hemiparesis, encephalopathy, and extrapontine osmotic myelinolysis in the setting of hyperosmolar hyperglycemia. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20(6):894–896. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2012.05.045

- Hegazi MO, Mashankar A. Central pontine myelinolysis in the hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state. Med Princ Pract 2013; 22(1):96–99. doi:10.1159/000341718

- Rodríguez-Velver KV, Soto-Garcia AJ, Zapata-Rivera MA, Montes-Villarreal J, Villarreal-Pérez JZ, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R. Osmotic demyelination syndrome as the initial manifestation of a hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state. Case Rep Neurol Med 2014; 2014:652523. doi:10.1155/2014/652523

- Chang YM. Central pontine myelinolysis associated with diabetic hyperglycemia. JSM Clin Case Rep 2014; 2(6):1059.

Aortic dissection presenting as ischemic limb

A 40-year-old man with a history of hypertension and alcohol abuse presented with acute onset of mild chest tightness, left leg pain, and increasing agitation, which prevented us from obtaining additional meaningful information from him.

On admission, his heart rate was 120 beats per minute, blood pressure 211/122 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 per minute, and oxygen saturation 92% on room air. Given his history of alcohol abuse, we checked his blood ethanol level, which was less than 0.01%, well below the legal limit for intoxication.

We gave the patient intravenous lorazepam for possible alcohol withdrawal and started labetalol by intravenous infusion to lower his blood pressure.

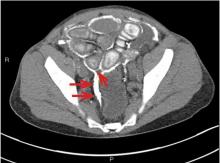

On physical examination, his left lower extremity was cold and without pulses, including the femoral pulse. Suspecting acute arterial thrombosis, we ordered immediate computed tomographic (CT) angiography of the abdomen and pelvis with left lower extremity runoff. The images showed dissection of the abdominal aorta with extension to both the left and right common iliac arteries and the origin of the right external iliac artery. There was resultant occlusion of the left external iliac artery (Figure 1).

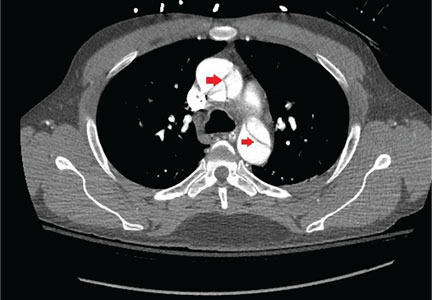

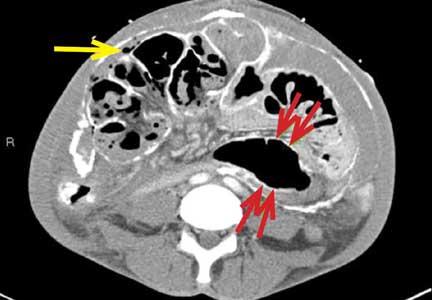

Immediate CT angiography of the chest was then performed, which revealed dissection of the thoracic aorta as well, starting superior to the aortic valve annulus and involving the ascending aorta, aortic arch, and the entire descending thoracic aorta (Figure 2).

The patient underwent emergency surgical repair of the aortic root, ascending aorta, and aortic arch. Residual dissection of the descending aorta was managed conservatively with blood pressure control using intravenous labetalol initially, which was then switched to oral carvedilol, and the pulses returned in his left lower extremity. He had an unremarkable postoperative recovery and was discharged after 1 week.

AORTIC DISSECTION AND MALPERFUSION SYNDROME

Aortic dissection is most often associated with acute onset of sharp chest pain and upper back pain. On rare occasions, it can have an atypical presentation such as stroke, paraplegia, mesenteric ischemia, or lower limb malperfusion.1

Extension of aortic dissection into the iliac and femoral arteries can cause impaired or absent blood flow to the lower extremity. These pulse deficits are a part of limb malperfusion syndrome. Symptoms of malperfusion syndrome vary greatly and depend on the vessels involved. Malperfusion of the branches of the aortic arch can result in stroke or altered sensorium. Compromise of intra-abdominal vessels due to dissection can involve the mesenteric bed, the renal arteries, or both, resulting in laboratory derangements such as lactic acidosis and renal failure.

How aortic dissection and malperfusion syndrome occur

Over time, shear forces on the aortic wall result in degeneration of the tunica intima and media. Dissection occurs when deterioration of the intima causes propagation of blood through a cleavage plane into the outer portion of the diseased media, forming a false lumen.

Anterograde or retrograde progression of dissection depends on the balance of the pressure gradient between true and false lumens.2 With every systolic ventricular contraction, a fluid and pressure wave travels down both lumens (true and false). However, the pressure gradient between the false and true lumens allows the more pliable intimal flap to bulge into the true lumen and ostia of branch vessels, resulting in static or dynamic obstruction.

Static obstruction occurs when the false lumen projects completely into the branch vessel and there is resultant thrombosis. As the name implies, dynamic obstruction is intermittent and is responsible for 80% of the cases of malperfusion syndrome.3 Dynamic obstruction has 2 distinct mechanisms: hypoperfusion through the true lumen due to impaired flow, and prolapse of the false lumen into a branch vessel.

Factors that exacerbate hypoperfusion through the true lumen and make obliteration by the false lumen more likely include large circumference of the dissected aorta, rapid heart rate, and high systolic pressure.4 Therefore, it is important to control the heart rate and blood pressure using beta-blockers in cases of aortic dissection with malperfusion syndrome. This treatment may resolve the dynamic obstruction through expansion and resumption of perfusion through the true lumen.5

MANAGEMENT OF MALPERFUSION SYNDROME

Aortic dissection can be classified as either Stanford type A (involving the ascending aorta) or type B (involving the descending aorta). Type B dissection associated with malperfusion syndrome is termed “complicated” type B aortic dissection. Our patient had both Stanford type A and complicated type B aortic dissection.

Unlike type A aortic dissection, which requires definitive open surgical repair, complicated type B aortic dissection occasionally responds to medical management alone. A plausible explanation for resolution of limb malperfusion with optimal blood pressure control is expansion of the true lumen and obliteration of the false lumen, as was likely the case in our patient.

In most cases, however, limb malperfusion persists despite optimal medical management. In such patients, endovascular graft stenting or open surgical repair may be needed. Open surgical repair procedures like bypass grafting or surgical fenestration are associated with significant rates of mortality and morbidity.5 Therefore, an endovascular approach rather than conventional surgical repair for complicated type B aortic dissection is advocated after optimal medical management.6 Endovascular repair also promotes favorable aortic remodeling without the morbidity associated with open surgical repair.

- Namana V, Balasubramanian R, Kariyanna PT, Sarasam R, Namana S, Shetty V. Aortic dissection with hemopericardium and thrombosed left common iliac artery presenting as acute limb ischemia: a case report and review. Am J Med Case Rep 2015; 3(10):338–343. doi:10.12691/ajmcr-3-10-9

- Crawford TC, Beaulieu RJ, Ehlert BA, Ratchford EV, Black JH 3rd. Malperfusion syndromes in aortic dissections. Vasc Med 2016; 21(3):264–273. doi:10.1177/1358863X15625371

- Williams DM, Lee DY, Hamilton BH, et al. The dissected aorta: percutaneous treatment of ischemic complications—principles and results. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1997; 8(4):605–625. pmid:9232578

- Chung JW, Elkins C, Sakai T, et al. True-lumen collapse in aortic dissection: part II. Evaluation of treatment methods in phantoms with pulsatile flow. Radiology 2000; 214(1):99–106. doi:10.1148/radiology.214.1.r00ja3499

- Gargiulo M, Bianchini Massoni C, Gallitto E, et al. Lower limb malperfusion in type B aortic dissection: a systematic review. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2014; 3(4):351–367. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2014.07.05

- Dake MD, Kato N, Mitchell RS, et al. Endovascular stent-graft placement for the treatment of acute aortic dissection. N Engl J Med 1999; 340(20):1546–1552. doi:10.1056/NEJM199905203402004

A 40-year-old man with a history of hypertension and alcohol abuse presented with acute onset of mild chest tightness, left leg pain, and increasing agitation, which prevented us from obtaining additional meaningful information from him.

On admission, his heart rate was 120 beats per minute, blood pressure 211/122 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 per minute, and oxygen saturation 92% on room air. Given his history of alcohol abuse, we checked his blood ethanol level, which was less than 0.01%, well below the legal limit for intoxication.

We gave the patient intravenous lorazepam for possible alcohol withdrawal and started labetalol by intravenous infusion to lower his blood pressure.

On physical examination, his left lower extremity was cold and without pulses, including the femoral pulse. Suspecting acute arterial thrombosis, we ordered immediate computed tomographic (CT) angiography of the abdomen and pelvis with left lower extremity runoff. The images showed dissection of the abdominal aorta with extension to both the left and right common iliac arteries and the origin of the right external iliac artery. There was resultant occlusion of the left external iliac artery (Figure 1).

Immediate CT angiography of the chest was then performed, which revealed dissection of the thoracic aorta as well, starting superior to the aortic valve annulus and involving the ascending aorta, aortic arch, and the entire descending thoracic aorta (Figure 2).

The patient underwent emergency surgical repair of the aortic root, ascending aorta, and aortic arch. Residual dissection of the descending aorta was managed conservatively with blood pressure control using intravenous labetalol initially, which was then switched to oral carvedilol, and the pulses returned in his left lower extremity. He had an unremarkable postoperative recovery and was discharged after 1 week.

AORTIC DISSECTION AND MALPERFUSION SYNDROME

Aortic dissection is most often associated with acute onset of sharp chest pain and upper back pain. On rare occasions, it can have an atypical presentation such as stroke, paraplegia, mesenteric ischemia, or lower limb malperfusion.1

Extension of aortic dissection into the iliac and femoral arteries can cause impaired or absent blood flow to the lower extremity. These pulse deficits are a part of limb malperfusion syndrome. Symptoms of malperfusion syndrome vary greatly and depend on the vessels involved. Malperfusion of the branches of the aortic arch can result in stroke or altered sensorium. Compromise of intra-abdominal vessels due to dissection can involve the mesenteric bed, the renal arteries, or both, resulting in laboratory derangements such as lactic acidosis and renal failure.

How aortic dissection and malperfusion syndrome occur

Over time, shear forces on the aortic wall result in degeneration of the tunica intima and media. Dissection occurs when deterioration of the intima causes propagation of blood through a cleavage plane into the outer portion of the diseased media, forming a false lumen.

Anterograde or retrograde progression of dissection depends on the balance of the pressure gradient between true and false lumens.2 With every systolic ventricular contraction, a fluid and pressure wave travels down both lumens (true and false). However, the pressure gradient between the false and true lumens allows the more pliable intimal flap to bulge into the true lumen and ostia of branch vessels, resulting in static or dynamic obstruction.

Static obstruction occurs when the false lumen projects completely into the branch vessel and there is resultant thrombosis. As the name implies, dynamic obstruction is intermittent and is responsible for 80% of the cases of malperfusion syndrome.3 Dynamic obstruction has 2 distinct mechanisms: hypoperfusion through the true lumen due to impaired flow, and prolapse of the false lumen into a branch vessel.

Factors that exacerbate hypoperfusion through the true lumen and make obliteration by the false lumen more likely include large circumference of the dissected aorta, rapid heart rate, and high systolic pressure.4 Therefore, it is important to control the heart rate and blood pressure using beta-blockers in cases of aortic dissection with malperfusion syndrome. This treatment may resolve the dynamic obstruction through expansion and resumption of perfusion through the true lumen.5

MANAGEMENT OF MALPERFUSION SYNDROME

Aortic dissection can be classified as either Stanford type A (involving the ascending aorta) or type B (involving the descending aorta). Type B dissection associated with malperfusion syndrome is termed “complicated” type B aortic dissection. Our patient had both Stanford type A and complicated type B aortic dissection.

Unlike type A aortic dissection, which requires definitive open surgical repair, complicated type B aortic dissection occasionally responds to medical management alone. A plausible explanation for resolution of limb malperfusion with optimal blood pressure control is expansion of the true lumen and obliteration of the false lumen, as was likely the case in our patient.

In most cases, however, limb malperfusion persists despite optimal medical management. In such patients, endovascular graft stenting or open surgical repair may be needed. Open surgical repair procedures like bypass grafting or surgical fenestration are associated with significant rates of mortality and morbidity.5 Therefore, an endovascular approach rather than conventional surgical repair for complicated type B aortic dissection is advocated after optimal medical management.6 Endovascular repair also promotes favorable aortic remodeling without the morbidity associated with open surgical repair.

A 40-year-old man with a history of hypertension and alcohol abuse presented with acute onset of mild chest tightness, left leg pain, and increasing agitation, which prevented us from obtaining additional meaningful information from him.

On admission, his heart rate was 120 beats per minute, blood pressure 211/122 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 per minute, and oxygen saturation 92% on room air. Given his history of alcohol abuse, we checked his blood ethanol level, which was less than 0.01%, well below the legal limit for intoxication.

We gave the patient intravenous lorazepam for possible alcohol withdrawal and started labetalol by intravenous infusion to lower his blood pressure.

On physical examination, his left lower extremity was cold and without pulses, including the femoral pulse. Suspecting acute arterial thrombosis, we ordered immediate computed tomographic (CT) angiography of the abdomen and pelvis with left lower extremity runoff. The images showed dissection of the abdominal aorta with extension to both the left and right common iliac arteries and the origin of the right external iliac artery. There was resultant occlusion of the left external iliac artery (Figure 1).

Immediate CT angiography of the chest was then performed, which revealed dissection of the thoracic aorta as well, starting superior to the aortic valve annulus and involving the ascending aorta, aortic arch, and the entire descending thoracic aorta (Figure 2).

The patient underwent emergency surgical repair of the aortic root, ascending aorta, and aortic arch. Residual dissection of the descending aorta was managed conservatively with blood pressure control using intravenous labetalol initially, which was then switched to oral carvedilol, and the pulses returned in his left lower extremity. He had an unremarkable postoperative recovery and was discharged after 1 week.

AORTIC DISSECTION AND MALPERFUSION SYNDROME

Aortic dissection is most often associated with acute onset of sharp chest pain and upper back pain. On rare occasions, it can have an atypical presentation such as stroke, paraplegia, mesenteric ischemia, or lower limb malperfusion.1

Extension of aortic dissection into the iliac and femoral arteries can cause impaired or absent blood flow to the lower extremity. These pulse deficits are a part of limb malperfusion syndrome. Symptoms of malperfusion syndrome vary greatly and depend on the vessels involved. Malperfusion of the branches of the aortic arch can result in stroke or altered sensorium. Compromise of intra-abdominal vessels due to dissection can involve the mesenteric bed, the renal arteries, or both, resulting in laboratory derangements such as lactic acidosis and renal failure.

How aortic dissection and malperfusion syndrome occur

Over time, shear forces on the aortic wall result in degeneration of the tunica intima and media. Dissection occurs when deterioration of the intima causes propagation of blood through a cleavage plane into the outer portion of the diseased media, forming a false lumen.

Anterograde or retrograde progression of dissection depends on the balance of the pressure gradient between true and false lumens.2 With every systolic ventricular contraction, a fluid and pressure wave travels down both lumens (true and false). However, the pressure gradient between the false and true lumens allows the more pliable intimal flap to bulge into the true lumen and ostia of branch vessels, resulting in static or dynamic obstruction.

Static obstruction occurs when the false lumen projects completely into the branch vessel and there is resultant thrombosis. As the name implies, dynamic obstruction is intermittent and is responsible for 80% of the cases of malperfusion syndrome.3 Dynamic obstruction has 2 distinct mechanisms: hypoperfusion through the true lumen due to impaired flow, and prolapse of the false lumen into a branch vessel.

Factors that exacerbate hypoperfusion through the true lumen and make obliteration by the false lumen more likely include large circumference of the dissected aorta, rapid heart rate, and high systolic pressure.4 Therefore, it is important to control the heart rate and blood pressure using beta-blockers in cases of aortic dissection with malperfusion syndrome. This treatment may resolve the dynamic obstruction through expansion and resumption of perfusion through the true lumen.5

MANAGEMENT OF MALPERFUSION SYNDROME

Aortic dissection can be classified as either Stanford type A (involving the ascending aorta) or type B (involving the descending aorta). Type B dissection associated with malperfusion syndrome is termed “complicated” type B aortic dissection. Our patient had both Stanford type A and complicated type B aortic dissection.

Unlike type A aortic dissection, which requires definitive open surgical repair, complicated type B aortic dissection occasionally responds to medical management alone. A plausible explanation for resolution of limb malperfusion with optimal blood pressure control is expansion of the true lumen and obliteration of the false lumen, as was likely the case in our patient.

In most cases, however, limb malperfusion persists despite optimal medical management. In such patients, endovascular graft stenting or open surgical repair may be needed. Open surgical repair procedures like bypass grafting or surgical fenestration are associated with significant rates of mortality and morbidity.5 Therefore, an endovascular approach rather than conventional surgical repair for complicated type B aortic dissection is advocated after optimal medical management.6 Endovascular repair also promotes favorable aortic remodeling without the morbidity associated with open surgical repair.

- Namana V, Balasubramanian R, Kariyanna PT, Sarasam R, Namana S, Shetty V. Aortic dissection with hemopericardium and thrombosed left common iliac artery presenting as acute limb ischemia: a case report and review. Am J Med Case Rep 2015; 3(10):338–343. doi:10.12691/ajmcr-3-10-9

- Crawford TC, Beaulieu RJ, Ehlert BA, Ratchford EV, Black JH 3rd. Malperfusion syndromes in aortic dissections. Vasc Med 2016; 21(3):264–273. doi:10.1177/1358863X15625371

- Williams DM, Lee DY, Hamilton BH, et al. The dissected aorta: percutaneous treatment of ischemic complications—principles and results. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1997; 8(4):605–625. pmid:9232578

- Chung JW, Elkins C, Sakai T, et al. True-lumen collapse in aortic dissection: part II. Evaluation of treatment methods in phantoms with pulsatile flow. Radiology 2000; 214(1):99–106. doi:10.1148/radiology.214.1.r00ja3499

- Gargiulo M, Bianchini Massoni C, Gallitto E, et al. Lower limb malperfusion in type B aortic dissection: a systematic review. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2014; 3(4):351–367. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2014.07.05

- Dake MD, Kato N, Mitchell RS, et al. Endovascular stent-graft placement for the treatment of acute aortic dissection. N Engl J Med 1999; 340(20):1546–1552. doi:10.1056/NEJM199905203402004

- Namana V, Balasubramanian R, Kariyanna PT, Sarasam R, Namana S, Shetty V. Aortic dissection with hemopericardium and thrombosed left common iliac artery presenting as acute limb ischemia: a case report and review. Am J Med Case Rep 2015; 3(10):338–343. doi:10.12691/ajmcr-3-10-9

- Crawford TC, Beaulieu RJ, Ehlert BA, Ratchford EV, Black JH 3rd. Malperfusion syndromes in aortic dissections. Vasc Med 2016; 21(3):264–273. doi:10.1177/1358863X15625371

- Williams DM, Lee DY, Hamilton BH, et al. The dissected aorta: percutaneous treatment of ischemic complications—principles and results. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1997; 8(4):605–625. pmid:9232578

- Chung JW, Elkins C, Sakai T, et al. True-lumen collapse in aortic dissection: part II. Evaluation of treatment methods in phantoms with pulsatile flow. Radiology 2000; 214(1):99–106. doi:10.1148/radiology.214.1.r00ja3499

- Gargiulo M, Bianchini Massoni C, Gallitto E, et al. Lower limb malperfusion in type B aortic dissection: a systematic review. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2014; 3(4):351–367. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2014.07.05

- Dake MD, Kato N, Mitchell RS, et al. Endovascular stent-graft placement for the treatment of acute aortic dissection. N Engl J Med 1999; 340(20):1546–1552. doi:10.1056/NEJM199905203402004

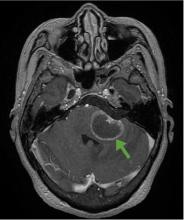

Central nervous system lymphoma mimicking Bell palsy

A 59-year-old woman presented with drooling out of the left side of her mouth and inability to close her left eye. She had no ear pain, hearing loss, or skin rash. The facial palsy affected all branches of the left facial nerve. This explained her inability to close her left eyelid and the generalized weakness of the left side of the face, including her forehead and angle of the mouth. No other signs of pontine dysfunction were noted.

The symptoms had begun 2 months earlier, and computed tomography (CT) of the head performed at a nearby clinic 3 days after the onset of symptoms showed no abnormalities. She was given a diagnosis of incomplete Bell palsy and was prescribed prednisolone and valacyclovir. However, her symptoms had not improved after 2 months of treatment, and so she presented to our hospital.

Physical examination revealed moderate nerve dysfunction (House-Brackmann grade III, with grade I normal and grade VI total paralysis) and generalized weakness on the left side of her face including her forehead.1 She had no loss in facial sensation or hearing and no ataxia or ocular motility disorders.

BELL PALSY

Peripheral facial nerve palsy is classified either as Bell palsy, which is idiopathic, or as secondary facial nerve palsy. Because Bell palsy accounts for 60% to 70% of all cases,2 treatment with oral steroids is indicated when no abnormal findings other than lateral peripheral facial nerve palsy are observed. Antiviral drugs may provide added benefit, although academic societies do not currently recommend combined therapy.3 However, 85% of patients with Bell palsy improve within 3 weeks without treatment, and 94% of patients with incomplete Bell palsy—defined by normal to severe dysfunction, ie, not total paralysis, based on House-Brackmann score—eventually achieve complete remission.2

Therefore, although progression of symptoms or lack of improvement at 2 months does not rule out Bell palsy, it should prompt a detailed imaging evaluation to rule out an underlying condition such as tumor (in the pons, cerebellopontine angle, parotid gland, middle ear, or petrosal bone), infection (herpes simplex, varicella zoster, Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, or otitis media), trauma, or systemic disease (diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, or systemic lupus erythematosus).4

According to a review of common causes of facial nerve palsy, the most common finding in 224 patients misdiagnosed with Bell palsy was tumor (38%).5 This indicates the value of magnetic resonance imaging of the head rather than CT when secondary facial nerve palsy is suspected, as CT is not sensitive to brainstem lesions.

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck 1985; 93(2):146–147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202

- Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002; suppl 549:4–30. pmid:12482166

- De Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 302(9):985–993. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1243

- Alaani A, Hogg R, Saravanappa N, Irving RM. An analysis of diagnostic delay in unilateral facial paralysis. J Laryngol Otol 2005; 119(3):184–188. pmid:15845188

- May M, Klein SR. Differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991; 24(3):613–645. pmid:1762779

A 59-year-old woman presented with drooling out of the left side of her mouth and inability to close her left eye. She had no ear pain, hearing loss, or skin rash. The facial palsy affected all branches of the left facial nerve. This explained her inability to close her left eyelid and the generalized weakness of the left side of the face, including her forehead and angle of the mouth. No other signs of pontine dysfunction were noted.

The symptoms had begun 2 months earlier, and computed tomography (CT) of the head performed at a nearby clinic 3 days after the onset of symptoms showed no abnormalities. She was given a diagnosis of incomplete Bell palsy and was prescribed prednisolone and valacyclovir. However, her symptoms had not improved after 2 months of treatment, and so she presented to our hospital.

Physical examination revealed moderate nerve dysfunction (House-Brackmann grade III, with grade I normal and grade VI total paralysis) and generalized weakness on the left side of her face including her forehead.1 She had no loss in facial sensation or hearing and no ataxia or ocular motility disorders.

BELL PALSY

Peripheral facial nerve palsy is classified either as Bell palsy, which is idiopathic, or as secondary facial nerve palsy. Because Bell palsy accounts for 60% to 70% of all cases,2 treatment with oral steroids is indicated when no abnormal findings other than lateral peripheral facial nerve palsy are observed. Antiviral drugs may provide added benefit, although academic societies do not currently recommend combined therapy.3 However, 85% of patients with Bell palsy improve within 3 weeks without treatment, and 94% of patients with incomplete Bell palsy—defined by normal to severe dysfunction, ie, not total paralysis, based on House-Brackmann score—eventually achieve complete remission.2

Therefore, although progression of symptoms or lack of improvement at 2 months does not rule out Bell palsy, it should prompt a detailed imaging evaluation to rule out an underlying condition such as tumor (in the pons, cerebellopontine angle, parotid gland, middle ear, or petrosal bone), infection (herpes simplex, varicella zoster, Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, or otitis media), trauma, or systemic disease (diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, or systemic lupus erythematosus).4

According to a review of common causes of facial nerve palsy, the most common finding in 224 patients misdiagnosed with Bell palsy was tumor (38%).5 This indicates the value of magnetic resonance imaging of the head rather than CT when secondary facial nerve palsy is suspected, as CT is not sensitive to brainstem lesions.

A 59-year-old woman presented with drooling out of the left side of her mouth and inability to close her left eye. She had no ear pain, hearing loss, or skin rash. The facial palsy affected all branches of the left facial nerve. This explained her inability to close her left eyelid and the generalized weakness of the left side of the face, including her forehead and angle of the mouth. No other signs of pontine dysfunction were noted.

The symptoms had begun 2 months earlier, and computed tomography (CT) of the head performed at a nearby clinic 3 days after the onset of symptoms showed no abnormalities. She was given a diagnosis of incomplete Bell palsy and was prescribed prednisolone and valacyclovir. However, her symptoms had not improved after 2 months of treatment, and so she presented to our hospital.

Physical examination revealed moderate nerve dysfunction (House-Brackmann grade III, with grade I normal and grade VI total paralysis) and generalized weakness on the left side of her face including her forehead.1 She had no loss in facial sensation or hearing and no ataxia or ocular motility disorders.

BELL PALSY

Peripheral facial nerve palsy is classified either as Bell palsy, which is idiopathic, or as secondary facial nerve palsy. Because Bell palsy accounts for 60% to 70% of all cases,2 treatment with oral steroids is indicated when no abnormal findings other than lateral peripheral facial nerve palsy are observed. Antiviral drugs may provide added benefit, although academic societies do not currently recommend combined therapy.3 However, 85% of patients with Bell palsy improve within 3 weeks without treatment, and 94% of patients with incomplete Bell palsy—defined by normal to severe dysfunction, ie, not total paralysis, based on House-Brackmann score—eventually achieve complete remission.2

Therefore, although progression of symptoms or lack of improvement at 2 months does not rule out Bell palsy, it should prompt a detailed imaging evaluation to rule out an underlying condition such as tumor (in the pons, cerebellopontine angle, parotid gland, middle ear, or petrosal bone), infection (herpes simplex, varicella zoster, Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, or otitis media), trauma, or systemic disease (diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, or systemic lupus erythematosus).4

According to a review of common causes of facial nerve palsy, the most common finding in 224 patients misdiagnosed with Bell palsy was tumor (38%).5 This indicates the value of magnetic resonance imaging of the head rather than CT when secondary facial nerve palsy is suspected, as CT is not sensitive to brainstem lesions.

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck 1985; 93(2):146–147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202

- Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002; suppl 549:4–30. pmid:12482166

- De Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 302(9):985–993. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1243

- Alaani A, Hogg R, Saravanappa N, Irving RM. An analysis of diagnostic delay in unilateral facial paralysis. J Laryngol Otol 2005; 119(3):184–188. pmid:15845188

- May M, Klein SR. Differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991; 24(3):613–645. pmid:1762779

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck 1985; 93(2):146–147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202

- Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002; suppl 549:4–30. pmid:12482166

- De Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 302(9):985–993. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1243

- Alaani A, Hogg R, Saravanappa N, Irving RM. An analysis of diagnostic delay in unilateral facial paralysis. J Laryngol Otol 2005; 119(3):184–188. pmid:15845188

- May M, Klein SR. Differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991; 24(3):613–645. pmid:1762779

Necrotizing fasciitis after a watercraft accident

A 57-year-old man was transferred to our hospital with leg pain and confusion. His family reported that he had injured his leg while launching a motorized personal watercraft at the North Carolina seashore 2 days before. He had a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C and alcohol abuse.

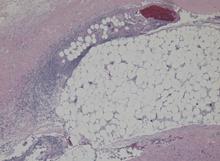

Blood and wound cultures eventually grew V vulnificus, and surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis (Figure 2).

RISE IN V VULNIFICUS INFECTIONS IS ATTRIBUTED TO GLOBAL WARMING

V vulnificus infection occurs most commonly from consuming raw shellfish, especially oysters, but it also occurs after exposure of an open wound to contaminated salt water. The pathogen is a gram-negative bacterium that resides in coastal waters worldwide, but in the United States it is usually seen on the Pacific and Gulf coasts1 during the summer.2

Although only 58 cases of V vulnificus infection were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1997, the number more than doubled to 124 in 2014.1 This rise is suspected to be due in part to warmer coastal waters associated with global warming.2

Various marine pathogens can cause wound infections, but V vulnificus is most commonly implicated in deaths and hospitalizations.2 Immunocompromised patients and those with liver disease are at particularly high risk of rapid progression to septic shock.

First-line antibiotics are doxycycline plus a third-generation cephalosporin.3 Studies have shown a direct correlation between delay of antibiotics and death,4 and early surgery is critical.5

Given the rising incidence of V vulnificus infection, it is increasingly important for providers across the United States to be aware of this infection.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National enteric disease surveillance: COVIS annual summary, 2014. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2014. www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/pdfs/covis-annual-summary-2014-508c.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Newton A, Kendall M, Vugia DJ, Henao OL, Mahon BE. Increasing rates of vibriosis in the United States, 1996–2010: review of surveillance data from 2 systems. Clinl Infect Dis 2012; 54(suppl 5):S391–S395. doi:10.1093/cid/cis243

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59(2):147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444

- Klontz KC, Lieb S, Schreiber M, Janowski HT, Baldy LM, Gunn RA. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida cases, 1981-1987. Ann Intern Med 1988; 109:318–323. pmid:3260760

- Chao WN, Tsai CF, Chang HR, et al. Impact of timing of surgery on outcome of Vibrio vulnificus-related necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg 2013; 206(1):32–39. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.08.008

A 57-year-old man was transferred to our hospital with leg pain and confusion. His family reported that he had injured his leg while launching a motorized personal watercraft at the North Carolina seashore 2 days before. He had a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C and alcohol abuse.

Blood and wound cultures eventually grew V vulnificus, and surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis (Figure 2).

RISE IN V VULNIFICUS INFECTIONS IS ATTRIBUTED TO GLOBAL WARMING

V vulnificus infection occurs most commonly from consuming raw shellfish, especially oysters, but it also occurs after exposure of an open wound to contaminated salt water. The pathogen is a gram-negative bacterium that resides in coastal waters worldwide, but in the United States it is usually seen on the Pacific and Gulf coasts1 during the summer.2

Although only 58 cases of V vulnificus infection were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1997, the number more than doubled to 124 in 2014.1 This rise is suspected to be due in part to warmer coastal waters associated with global warming.2

Various marine pathogens can cause wound infections, but V vulnificus is most commonly implicated in deaths and hospitalizations.2 Immunocompromised patients and those with liver disease are at particularly high risk of rapid progression to septic shock.

First-line antibiotics are doxycycline plus a third-generation cephalosporin.3 Studies have shown a direct correlation between delay of antibiotics and death,4 and early surgery is critical.5

Given the rising incidence of V vulnificus infection, it is increasingly important for providers across the United States to be aware of this infection.

A 57-year-old man was transferred to our hospital with leg pain and confusion. His family reported that he had injured his leg while launching a motorized personal watercraft at the North Carolina seashore 2 days before. He had a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C and alcohol abuse.

Blood and wound cultures eventually grew V vulnificus, and surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis (Figure 2).

RISE IN V VULNIFICUS INFECTIONS IS ATTRIBUTED TO GLOBAL WARMING

V vulnificus infection occurs most commonly from consuming raw shellfish, especially oysters, but it also occurs after exposure of an open wound to contaminated salt water. The pathogen is a gram-negative bacterium that resides in coastal waters worldwide, but in the United States it is usually seen on the Pacific and Gulf coasts1 during the summer.2

Although only 58 cases of V vulnificus infection were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1997, the number more than doubled to 124 in 2014.1 This rise is suspected to be due in part to warmer coastal waters associated with global warming.2

Various marine pathogens can cause wound infections, but V vulnificus is most commonly implicated in deaths and hospitalizations.2 Immunocompromised patients and those with liver disease are at particularly high risk of rapid progression to septic shock.

First-line antibiotics are doxycycline plus a third-generation cephalosporin.3 Studies have shown a direct correlation between delay of antibiotics and death,4 and early surgery is critical.5

Given the rising incidence of V vulnificus infection, it is increasingly important for providers across the United States to be aware of this infection.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National enteric disease surveillance: COVIS annual summary, 2014. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2014. www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/pdfs/covis-annual-summary-2014-508c.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Newton A, Kendall M, Vugia DJ, Henao OL, Mahon BE. Increasing rates of vibriosis in the United States, 1996–2010: review of surveillance data from 2 systems. Clinl Infect Dis 2012; 54(suppl 5):S391–S395. doi:10.1093/cid/cis243

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59(2):147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444

- Klontz KC, Lieb S, Schreiber M, Janowski HT, Baldy LM, Gunn RA. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida cases, 1981-1987. Ann Intern Med 1988; 109:318–323. pmid:3260760

- Chao WN, Tsai CF, Chang HR, et al. Impact of timing of surgery on outcome of Vibrio vulnificus-related necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg 2013; 206(1):32–39. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.08.008

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National enteric disease surveillance: COVIS annual summary, 2014. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2014. www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/pdfs/covis-annual-summary-2014-508c.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Newton A, Kendall M, Vugia DJ, Henao OL, Mahon BE. Increasing rates of vibriosis in the United States, 1996–2010: review of surveillance data from 2 systems. Clinl Infect Dis 2012; 54(suppl 5):S391–S395. doi:10.1093/cid/cis243

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59(2):147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444

- Klontz KC, Lieb S, Schreiber M, Janowski HT, Baldy LM, Gunn RA. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida cases, 1981-1987. Ann Intern Med 1988; 109:318–323. pmid:3260760

- Chao WN, Tsai CF, Chang HR, et al. Impact of timing of surgery on outcome of Vibrio vulnificus-related necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg 2013; 206(1):32–39. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.08.008

Eyes of the mimicker

Lumbar puncture study revealed 34 nucleated cells/µL (94% lymphocytes), protein 58 mg/dL, and glucose 62 mg/dL. Cerebrospinal fluid Venereal Disease Research Laboratory and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption tests were reactive, confirming a diagnosis of ocular syphilis.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment with intravenous penicillin G. After 5 days, he was discharged with instructions to complete a 10-day course of intravenous ceftriaxone (chosen for its ease of administration), for a total of 14 days of antibiotic therapy. His vision improved with treatment.

He continued to follow up with ophthalmology and infectious disease. Subsequent dilated fundus examinations showed resolution of pathology in the left eye, resolution of Roth spots in the right eye, and resolution of the subhyaloid hemorrhage. Repeat cerebrospinal fluid study examination was planned if the serum rapid plasma reagin had not become nonreactive 24 months after treatment.

RECOGNIZING AND MANAGING OCULAR SYPHILIS AND NEUROSYPHILIS

In addition to ocular syphilis and neurosyphilis, the differential diagnosis for Roth spots and disc edema on dilated funduscopy includes endocarditis, viral retinitis, and autoimmune or inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis and vasculitis.

In our patient, infectious endocarditis was considered, given his history of intermittent fevers and rigors, but it was ultimately ruled out by negative blood cultures and the absence of valvular vegetations on echocardiography.

The large subhyaloid hemorrhage raised suspicion of leukemia, but this was ruled out by the normal total white blood cell count and differential. HIV, herpetic retinitis, and toxoplasmosis were also considered, but laboratory tests for these infections were negative.

Typically, retinal precipitates are more characteristic of syphilitic retinitis and distinguish it from other infectious causes such as herpetic retinitis and toxoplasmosis.1 Additionally, ocular syphilis more commonly manifests as uveitis or panuveitis.1,2 Our patient’s ocular syphilis presented with white-centered retinal hemorrhages, subhyaloid hemorrhage, and optic disc edema.

Who is at highest risk?

About 90% of syphilis cases occur in men, and 81% occur in men who have sex with men. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) thus recommends annual syphilis testing for men who have sex with men.3

Classically, syphilis was called “the great imitator” because it mimicked manifestations of other diseases. Patients with ocular manifestations of syphilis may not have other neurologic symptoms.4,5 Nevertheless, cerebrospinal fluid examination should be done in all instances of ocular syphilis, as many patients with ocular syphilis have evidence of neurosyphilis on testing.2 The CDC also recommends follow-up cerebrospinal fluid analysis to assess treatment response.2 This was planned in our patient.

- Fu EX, Geraets RL, Dodds EM, et al. Superficial retinal precipitates in patients with syphilitic retinitis. Retina 2010; 30(7):1135–1143. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181cdf3ae

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Clinical Advisory: Ocular Syphilis in the United States, March 24, 2016. www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/clinicaladvisoryos2015.htm. Accessed March 28, 2018.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2015. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/std-surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2018.

- Rishi E, Govindarajan MV, Biswas J, Agarwal M, Sudharshan S, Rishi P. Syphilitic uveitis as the presenting feature of HIV. Indian J Ophthalmol 2016; 64(2):149–150. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.179714

- Zhang R, Qian J, Guo J, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes of syphilitic uveitis in a Chinese population. J Ophthalmol 2016; 2016:2797028. doi:10.1155/2016/2797028

Lumbar puncture study revealed 34 nucleated cells/µL (94% lymphocytes), protein 58 mg/dL, and glucose 62 mg/dL. Cerebrospinal fluid Venereal Disease Research Laboratory and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption tests were reactive, confirming a diagnosis of ocular syphilis.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment with intravenous penicillin G. After 5 days, he was discharged with instructions to complete a 10-day course of intravenous ceftriaxone (chosen for its ease of administration), for a total of 14 days of antibiotic therapy. His vision improved with treatment.

He continued to follow up with ophthalmology and infectious disease. Subsequent dilated fundus examinations showed resolution of pathology in the left eye, resolution of Roth spots in the right eye, and resolution of the subhyaloid hemorrhage. Repeat cerebrospinal fluid study examination was planned if the serum rapid plasma reagin had not become nonreactive 24 months after treatment.

RECOGNIZING AND MANAGING OCULAR SYPHILIS AND NEUROSYPHILIS

In addition to ocular syphilis and neurosyphilis, the differential diagnosis for Roth spots and disc edema on dilated funduscopy includes endocarditis, viral retinitis, and autoimmune or inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis and vasculitis.

In our patient, infectious endocarditis was considered, given his history of intermittent fevers and rigors, but it was ultimately ruled out by negative blood cultures and the absence of valvular vegetations on echocardiography.

The large subhyaloid hemorrhage raised suspicion of leukemia, but this was ruled out by the normal total white blood cell count and differential. HIV, herpetic retinitis, and toxoplasmosis were also considered, but laboratory tests for these infections were negative.

Typically, retinal precipitates are more characteristic of syphilitic retinitis and distinguish it from other infectious causes such as herpetic retinitis and toxoplasmosis.1 Additionally, ocular syphilis more commonly manifests as uveitis or panuveitis.1,2 Our patient’s ocular syphilis presented with white-centered retinal hemorrhages, subhyaloid hemorrhage, and optic disc edema.

Who is at highest risk?

About 90% of syphilis cases occur in men, and 81% occur in men who have sex with men. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) thus recommends annual syphilis testing for men who have sex with men.3

Classically, syphilis was called “the great imitator” because it mimicked manifestations of other diseases. Patients with ocular manifestations of syphilis may not have other neurologic symptoms.4,5 Nevertheless, cerebrospinal fluid examination should be done in all instances of ocular syphilis, as many patients with ocular syphilis have evidence of neurosyphilis on testing.2 The CDC also recommends follow-up cerebrospinal fluid analysis to assess treatment response.2 This was planned in our patient.

Lumbar puncture study revealed 34 nucleated cells/µL (94% lymphocytes), protein 58 mg/dL, and glucose 62 mg/dL. Cerebrospinal fluid Venereal Disease Research Laboratory and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption tests were reactive, confirming a diagnosis of ocular syphilis.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for treatment with intravenous penicillin G. After 5 days, he was discharged with instructions to complete a 10-day course of intravenous ceftriaxone (chosen for its ease of administration), for a total of 14 days of antibiotic therapy. His vision improved with treatment.

He continued to follow up with ophthalmology and infectious disease. Subsequent dilated fundus examinations showed resolution of pathology in the left eye, resolution of Roth spots in the right eye, and resolution of the subhyaloid hemorrhage. Repeat cerebrospinal fluid study examination was planned if the serum rapid plasma reagin had not become nonreactive 24 months after treatment.

RECOGNIZING AND MANAGING OCULAR SYPHILIS AND NEUROSYPHILIS

In addition to ocular syphilis and neurosyphilis, the differential diagnosis for Roth spots and disc edema on dilated funduscopy includes endocarditis, viral retinitis, and autoimmune or inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis and vasculitis.

In our patient, infectious endocarditis was considered, given his history of intermittent fevers and rigors, but it was ultimately ruled out by negative blood cultures and the absence of valvular vegetations on echocardiography.

The large subhyaloid hemorrhage raised suspicion of leukemia, but this was ruled out by the normal total white blood cell count and differential. HIV, herpetic retinitis, and toxoplasmosis were also considered, but laboratory tests for these infections were negative.

Typically, retinal precipitates are more characteristic of syphilitic retinitis and distinguish it from other infectious causes such as herpetic retinitis and toxoplasmosis.1 Additionally, ocular syphilis more commonly manifests as uveitis or panuveitis.1,2 Our patient’s ocular syphilis presented with white-centered retinal hemorrhages, subhyaloid hemorrhage, and optic disc edema.

Who is at highest risk?

About 90% of syphilis cases occur in men, and 81% occur in men who have sex with men. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) thus recommends annual syphilis testing for men who have sex with men.3

Classically, syphilis was called “the great imitator” because it mimicked manifestations of other diseases. Patients with ocular manifestations of syphilis may not have other neurologic symptoms.4,5 Nevertheless, cerebrospinal fluid examination should be done in all instances of ocular syphilis, as many patients with ocular syphilis have evidence of neurosyphilis on testing.2 The CDC also recommends follow-up cerebrospinal fluid analysis to assess treatment response.2 This was planned in our patient.

- Fu EX, Geraets RL, Dodds EM, et al. Superficial retinal precipitates in patients with syphilitic retinitis. Retina 2010; 30(7):1135–1143. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181cdf3ae

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Clinical Advisory: Ocular Syphilis in the United States, March 24, 2016. www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/clinicaladvisoryos2015.htm. Accessed March 28, 2018.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2015. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/std-surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2018.

- Rishi E, Govindarajan MV, Biswas J, Agarwal M, Sudharshan S, Rishi P. Syphilitic uveitis as the presenting feature of HIV. Indian J Ophthalmol 2016; 64(2):149–150. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.179714

- Zhang R, Qian J, Guo J, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes of syphilitic uveitis in a Chinese population. J Ophthalmol 2016; 2016:2797028. doi:10.1155/2016/2797028

- Fu EX, Geraets RL, Dodds EM, et al. Superficial retinal precipitates in patients with syphilitic retinitis. Retina 2010; 30(7):1135–1143. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181cdf3ae

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Clinical Advisory: Ocular Syphilis in the United States, March 24, 2016. www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/clinicaladvisoryos2015.htm. Accessed March 28, 2018.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2015. www.cdc.gov/std/stats15/std-surveillance-2015-print.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2018.

- Rishi E, Govindarajan MV, Biswas J, Agarwal M, Sudharshan S, Rishi P. Syphilitic uveitis as the presenting feature of HIV. Indian J Ophthalmol 2016; 64(2):149–150. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.179714

- Zhang R, Qian J, Guo J, et al. Clinical manifestations and treatment outcomes of syphilitic uveitis in a Chinese population. J Ophthalmol 2016; 2016:2797028. doi:10.1155/2016/2797028

An unusual complication of peritoneal dialysis

A 45-year-old man with end-stage renal disease secondary to hypertension presented with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He had been on peritoneal dialysis for 15 years.

Results of initial laboratory testing were as follows:

- Sodium 137 mmol/L (reference range 136–144)

- Potassium 3.7 mmol/L (3.5–5.0)

- Bicarbonate 31 mmol/L (22–30)

- Creatinine 17.5 mg/dL (0.58–0.96)

- Blood urea nitrogen 57 mg/dL (7–21)

- Lactic acid 1.7 mmol/L (0.5–2.2)

- White blood cell count 14.34 × 109/L (3.70–11.0).

Blood cultures were negative. Peritoneal fluid analysis showed a white blood cell count of 1.2 × 109/L (reference range < 0.5 × 109/L) with 89% neutrophils, and an amylase level less than 3 U/L (reference range < 100). Fluid cultures were positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus epidermidis.

CAUSES AND CLINICAL FEATURES

Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a devastating complication of peritoneal dialysis, occurring in 3% of patients on peritoneal dialysis. The mortality rate is above 40%.1,2 It is characterized by an initial inflammatory phase followed by extensive intraperitoneal fibrosis and encasement of bowel. Causes include prolonged exposure to peritoneal dialysis or glucose degradation products, a history of severe peritonitis, use of acetate as a dialysate buffer, and reaction to medications such as beta-blockers.3

Clinical features result from inflammation, ileus, and peritoneal adhesions and include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A high peritoneal transport rate, which often heralds development of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, leads to failure of ultrafiltration and to fluid retention.

CT is recommended for diagnosis and demonstrates peritoneal calcification with bowel thickening and dilation.

TREATMENT

Treatment entails stopping peritoneal dialysis, changing to hemodialysis, bowel rest, and corticosteroids. Successful treatment has been reported with a combination of corticosteroids and azathioprine.4,5 A retrospective study showed that adding the antifibrotic agent tamoxifen was associated with a decrease in the mortality rate.6 Bowel obstruction is a common complication, and surgery may be indicated. Enterolysis is a new surgical technique that has shown improved outcomes.7

- Kawaguchi Y, Saito A, Kawanishi H, et al. Recommendations on the management of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan, 2005: diagnosis, predictive markers, treatment, and preventive measures. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S83–S95. pmid:16300277

- Lee HY, Kim BS, Choi HY, et al. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis as a complication of long-term continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Korea. Nephrology (Carlton) 2003; 8(suppl 2):S33–S39. doi:10.1046/J.1440-1797.8.S.11.X

- Kawaguchi Y, Tranaeus A. A historical review of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int 2005; 25(suppl 4):S7–S13. pmid:16300267