User login

Central nervous system lymphoma mimicking Bell palsy

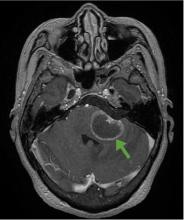

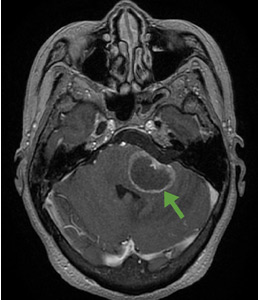

A 59-year-old woman presented with drooling out of the left side of her mouth and inability to close her left eye. She had no ear pain, hearing loss, or skin rash. The facial palsy affected all branches of the left facial nerve. This explained her inability to close her left eyelid and the generalized weakness of the left side of the face, including her forehead and angle of the mouth. No other signs of pontine dysfunction were noted.

The symptoms had begun 2 months earlier, and computed tomography (CT) of the head performed at a nearby clinic 3 days after the onset of symptoms showed no abnormalities. She was given a diagnosis of incomplete Bell palsy and was prescribed prednisolone and valacyclovir. However, her symptoms had not improved after 2 months of treatment, and so she presented to our hospital.

Physical examination revealed moderate nerve dysfunction (House-Brackmann grade III, with grade I normal and grade VI total paralysis) and generalized weakness on the left side of her face including her forehead.1 She had no loss in facial sensation or hearing and no ataxia or ocular motility disorders.

BELL PALSY

Peripheral facial nerve palsy is classified either as Bell palsy, which is idiopathic, or as secondary facial nerve palsy. Because Bell palsy accounts for 60% to 70% of all cases,2 treatment with oral steroids is indicated when no abnormal findings other than lateral peripheral facial nerve palsy are observed. Antiviral drugs may provide added benefit, although academic societies do not currently recommend combined therapy.3 However, 85% of patients with Bell palsy improve within 3 weeks without treatment, and 94% of patients with incomplete Bell palsy—defined by normal to severe dysfunction, ie, not total paralysis, based on House-Brackmann score—eventually achieve complete remission.2

Therefore, although progression of symptoms or lack of improvement at 2 months does not rule out Bell palsy, it should prompt a detailed imaging evaluation to rule out an underlying condition such as tumor (in the pons, cerebellopontine angle, parotid gland, middle ear, or petrosal bone), infection (herpes simplex, varicella zoster, Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, or otitis media), trauma, or systemic disease (diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, or systemic lupus erythematosus).4

According to a review of common causes of facial nerve palsy, the most common finding in 224 patients misdiagnosed with Bell palsy was tumor (38%).5 This indicates the value of magnetic resonance imaging of the head rather than CT when secondary facial nerve palsy is suspected, as CT is not sensitive to brainstem lesions.

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck 1985; 93(2):146–147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202

- Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002; suppl 549:4–30. pmid:12482166

- De Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 302(9):985–993. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1243

- Alaani A, Hogg R, Saravanappa N, Irving RM. An analysis of diagnostic delay in unilateral facial paralysis. J Laryngol Otol 2005; 119(3):184–188. pmid:15845188

- May M, Klein SR. Differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991; 24(3):613–645. pmid:1762779

A 59-year-old woman presented with drooling out of the left side of her mouth and inability to close her left eye. She had no ear pain, hearing loss, or skin rash. The facial palsy affected all branches of the left facial nerve. This explained her inability to close her left eyelid and the generalized weakness of the left side of the face, including her forehead and angle of the mouth. No other signs of pontine dysfunction were noted.

The symptoms had begun 2 months earlier, and computed tomography (CT) of the head performed at a nearby clinic 3 days after the onset of symptoms showed no abnormalities. She was given a diagnosis of incomplete Bell palsy and was prescribed prednisolone and valacyclovir. However, her symptoms had not improved after 2 months of treatment, and so she presented to our hospital.

Physical examination revealed moderate nerve dysfunction (House-Brackmann grade III, with grade I normal and grade VI total paralysis) and generalized weakness on the left side of her face including her forehead.1 She had no loss in facial sensation or hearing and no ataxia or ocular motility disorders.

BELL PALSY

Peripheral facial nerve palsy is classified either as Bell palsy, which is idiopathic, or as secondary facial nerve palsy. Because Bell palsy accounts for 60% to 70% of all cases,2 treatment with oral steroids is indicated when no abnormal findings other than lateral peripheral facial nerve palsy are observed. Antiviral drugs may provide added benefit, although academic societies do not currently recommend combined therapy.3 However, 85% of patients with Bell palsy improve within 3 weeks without treatment, and 94% of patients with incomplete Bell palsy—defined by normal to severe dysfunction, ie, not total paralysis, based on House-Brackmann score—eventually achieve complete remission.2

Therefore, although progression of symptoms or lack of improvement at 2 months does not rule out Bell palsy, it should prompt a detailed imaging evaluation to rule out an underlying condition such as tumor (in the pons, cerebellopontine angle, parotid gland, middle ear, or petrosal bone), infection (herpes simplex, varicella zoster, Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, or otitis media), trauma, or systemic disease (diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, or systemic lupus erythematosus).4

According to a review of common causes of facial nerve palsy, the most common finding in 224 patients misdiagnosed with Bell palsy was tumor (38%).5 This indicates the value of magnetic resonance imaging of the head rather than CT when secondary facial nerve palsy is suspected, as CT is not sensitive to brainstem lesions.

A 59-year-old woman presented with drooling out of the left side of her mouth and inability to close her left eye. She had no ear pain, hearing loss, or skin rash. The facial palsy affected all branches of the left facial nerve. This explained her inability to close her left eyelid and the generalized weakness of the left side of the face, including her forehead and angle of the mouth. No other signs of pontine dysfunction were noted.

The symptoms had begun 2 months earlier, and computed tomography (CT) of the head performed at a nearby clinic 3 days after the onset of symptoms showed no abnormalities. She was given a diagnosis of incomplete Bell palsy and was prescribed prednisolone and valacyclovir. However, her symptoms had not improved after 2 months of treatment, and so she presented to our hospital.

Physical examination revealed moderate nerve dysfunction (House-Brackmann grade III, with grade I normal and grade VI total paralysis) and generalized weakness on the left side of her face including her forehead.1 She had no loss in facial sensation or hearing and no ataxia or ocular motility disorders.

BELL PALSY

Peripheral facial nerve palsy is classified either as Bell palsy, which is idiopathic, or as secondary facial nerve palsy. Because Bell palsy accounts for 60% to 70% of all cases,2 treatment with oral steroids is indicated when no abnormal findings other than lateral peripheral facial nerve palsy are observed. Antiviral drugs may provide added benefit, although academic societies do not currently recommend combined therapy.3 However, 85% of patients with Bell palsy improve within 3 weeks without treatment, and 94% of patients with incomplete Bell palsy—defined by normal to severe dysfunction, ie, not total paralysis, based on House-Brackmann score—eventually achieve complete remission.2

Therefore, although progression of symptoms or lack of improvement at 2 months does not rule out Bell palsy, it should prompt a detailed imaging evaluation to rule out an underlying condition such as tumor (in the pons, cerebellopontine angle, parotid gland, middle ear, or petrosal bone), infection (herpes simplex, varicella zoster, Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, or otitis media), trauma, or systemic disease (diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, or systemic lupus erythematosus).4

According to a review of common causes of facial nerve palsy, the most common finding in 224 patients misdiagnosed with Bell palsy was tumor (38%).5 This indicates the value of magnetic resonance imaging of the head rather than CT when secondary facial nerve palsy is suspected, as CT is not sensitive to brainstem lesions.

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck 1985; 93(2):146–147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202

- Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002; suppl 549:4–30. pmid:12482166

- De Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 302(9):985–993. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1243

- Alaani A, Hogg R, Saravanappa N, Irving RM. An analysis of diagnostic delay in unilateral facial paralysis. J Laryngol Otol 2005; 119(3):184–188. pmid:15845188

- May M, Klein SR. Differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991; 24(3):613–645. pmid:1762779

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck 1985; 93(2):146–147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202

- Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002; suppl 549:4–30. pmid:12482166

- De Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009; 302(9):985–993. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1243

- Alaani A, Hogg R, Saravanappa N, Irving RM. An analysis of diagnostic delay in unilateral facial paralysis. J Laryngol Otol 2005; 119(3):184–188. pmid:15845188

- May M, Klein SR. Differential diagnosis of facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991; 24(3):613–645. pmid:1762779

Swelling of both arms and chest after push-ups

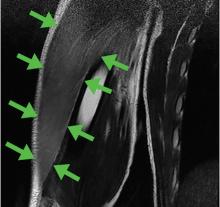

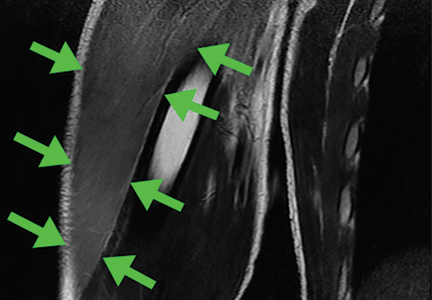

A healthy 16-year-old boy presented with muscle pain and weakness in the chest and both arms after performing 50 push-ups daily for 3 days, and the symptoms did not seem to improve after 3 days.

EXERCISE-INDUCED RHABDOMYOLYSIS

Approximately 50% of patients with rhabdomyolysis present with the characteristic triad of myalgia (84%), muscle weakness (73%), and dark urine (80%), and 8.1% to 52% present with muscle swelling.1 Rhabdomyolysis may be caused by exercise,2 and risk factors include physical deconditioning, high ambient temperature, high humidity, impaired sweating (due to anticholinergic drugs), sickle cell trait, and hypokalemia from sweating.2 Pain and swelling of the affected focal muscles is the chief complaint.3

Although acute renal failure in exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis is rare, failure to recognize rhabdomyolysis can cause diagnostic delay and inappropriate treatment.4

In healthy people, exercise-induced muscle damage begins to resolve within 1 to 3 days.5,6 Physicians should suspect exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis in patients with prolonged muscle swelling and tenderness in affected muscles that lasts longer than expected.7

- Nance JR, Mammen AL. Diagnostic evaluation of rhabdomyolysis. Muscle Nerve 2015; 51:793–810.

- Sayers SP, Clarkson PM. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. Curr Sports Med Rep 2002; 1:59–60.

- Have L, Drouet A. Isolated exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis of brachialis and brachioradialis muscles: an atypical clinical case. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2011; 54:525–529.

- Keah SH, Chng K. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure after strenuous push-ups. Malays Fam Physician 2009; 4:37–39.

- Nosaka K, Clarkson PM. Changes in indicators of inflammation after eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996; 28:953–961.

- Peake J, Nosaka K, Suzuki K. Characterization of inflammatory responses to eccentric exercise in humans. Exerc Immunol Rev 2005; 11:64–85.

- Lee G. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. R I Med J (2013) 2014; 97:22–24.

A healthy 16-year-old boy presented with muscle pain and weakness in the chest and both arms after performing 50 push-ups daily for 3 days, and the symptoms did not seem to improve after 3 days.

EXERCISE-INDUCED RHABDOMYOLYSIS

Approximately 50% of patients with rhabdomyolysis present with the characteristic triad of myalgia (84%), muscle weakness (73%), and dark urine (80%), and 8.1% to 52% present with muscle swelling.1 Rhabdomyolysis may be caused by exercise,2 and risk factors include physical deconditioning, high ambient temperature, high humidity, impaired sweating (due to anticholinergic drugs), sickle cell trait, and hypokalemia from sweating.2 Pain and swelling of the affected focal muscles is the chief complaint.3

Although acute renal failure in exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis is rare, failure to recognize rhabdomyolysis can cause diagnostic delay and inappropriate treatment.4

In healthy people, exercise-induced muscle damage begins to resolve within 1 to 3 days.5,6 Physicians should suspect exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis in patients with prolonged muscle swelling and tenderness in affected muscles that lasts longer than expected.7

A healthy 16-year-old boy presented with muscle pain and weakness in the chest and both arms after performing 50 push-ups daily for 3 days, and the symptoms did not seem to improve after 3 days.

EXERCISE-INDUCED RHABDOMYOLYSIS

Approximately 50% of patients with rhabdomyolysis present with the characteristic triad of myalgia (84%), muscle weakness (73%), and dark urine (80%), and 8.1% to 52% present with muscle swelling.1 Rhabdomyolysis may be caused by exercise,2 and risk factors include physical deconditioning, high ambient temperature, high humidity, impaired sweating (due to anticholinergic drugs), sickle cell trait, and hypokalemia from sweating.2 Pain and swelling of the affected focal muscles is the chief complaint.3

Although acute renal failure in exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis is rare, failure to recognize rhabdomyolysis can cause diagnostic delay and inappropriate treatment.4

In healthy people, exercise-induced muscle damage begins to resolve within 1 to 3 days.5,6 Physicians should suspect exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis in patients with prolonged muscle swelling and tenderness in affected muscles that lasts longer than expected.7

- Nance JR, Mammen AL. Diagnostic evaluation of rhabdomyolysis. Muscle Nerve 2015; 51:793–810.

- Sayers SP, Clarkson PM. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. Curr Sports Med Rep 2002; 1:59–60.

- Have L, Drouet A. Isolated exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis of brachialis and brachioradialis muscles: an atypical clinical case. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2011; 54:525–529.

- Keah SH, Chng K. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure after strenuous push-ups. Malays Fam Physician 2009; 4:37–39.

- Nosaka K, Clarkson PM. Changes in indicators of inflammation after eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996; 28:953–961.

- Peake J, Nosaka K, Suzuki K. Characterization of inflammatory responses to eccentric exercise in humans. Exerc Immunol Rev 2005; 11:64–85.

- Lee G. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. R I Med J (2013) 2014; 97:22–24.

- Nance JR, Mammen AL. Diagnostic evaluation of rhabdomyolysis. Muscle Nerve 2015; 51:793–810.

- Sayers SP, Clarkson PM. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. Curr Sports Med Rep 2002; 1:59–60.

- Have L, Drouet A. Isolated exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis of brachialis and brachioradialis muscles: an atypical clinical case. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2011; 54:525–529.

- Keah SH, Chng K. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure after strenuous push-ups. Malays Fam Physician 2009; 4:37–39.

- Nosaka K, Clarkson PM. Changes in indicators of inflammation after eccentric exercise of the elbow flexors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996; 28:953–961.

- Peake J, Nosaka K, Suzuki K. Characterization of inflammatory responses to eccentric exercise in humans. Exerc Immunol Rev 2005; 11:64–85.

- Lee G. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. R I Med J (2013) 2014; 97:22–24.

A 68-year-old man with a blue toe

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

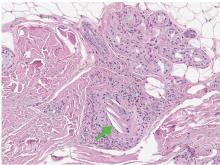

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.