User login

A 68-year-old man with a blue toe

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

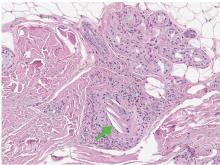

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

A 68-year-old man presented with concern about a bluish toe. Several months earlier he had undergone total aortic arch replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting. Since then his renal function had declined and he had been losing weight.

He had hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and a 20-pack-year smoking history. Physical examination confirmed that his right great toe was indeed bluish (Figure 1). Peripheral, neck, and abdominal vascular examinations were normal. Laboratory testing revealed:

- Serum creatinine concentration 5.15 mg/dL (reference range 0.61–1.04)

- C-reactive protein level 1.5 mg/dL (0–0.3)

- Eosinophil count 0.58 × 109/L (0–0.50)

- Serum complement level normal

- Urine sediment unremarkable.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no evidence of vegetation, and a series of blood cultures were negative. The right toe was biopsied, and study revealed cholesterol clefts (Figure 2), confirming the diagnosis of cholesterol crystal embolism.

He was treated with prednisolone 20 mg/day, and his weight loss and renal function improved.

CHOLESTEROL CRYSTAL EMBOLISM

Cholesterol embolization typically occurs after arteriography, cardiac catheterization, vascular surgery, or anticoagulant use in men over age 55 with atherosclerosis.1 It presents with renal failure, abdominal pain, systemic symptoms, or, most commonly (in 88% of cases), skin findings.2

“Blue-toe syndrome,” characterized by tissue ischemia, is seen in 65% of patients.2 Lesions can appear anywhere on the body, but most commonly on the lower extremities. Most are painful due to ischemia. The condition can progress to necrosis.

Patients may have elevated C-reactive protein, hypocomplementemia (39%), and eosinophilia (80%).3,4 The diagnosis is confirmed only with histopathologic findings of intravascular cholesterol crystals, seen as cholesterol clefts.

The differential diagnosis includes contrast nephropathy and infectious endocarditis. However, contrast nephropathy begins to recover within several days and is not accompanied by skin lesions. Repeated blood cultures and echocardiography are useful to rule out infectious endocarditis.

Treatment includes managing cardiovascular risk factors and end-organ ischemia and preventing recurrent embolization. Surgical or endovascular treatment has been shown to be effective in decreasing the rate of further embolism.2 Corticosteroid therapy is assumed to control the secondary inflammation associated with cholesterol crystal embolism.1,5

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.

- Paraskevas KI, Koutsias S, Mikhailidis DP, Giannoukas AD. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a possible complication of peripheral endovascular interventions. J Endovasc Ther 2008; 15:614–625.

- Jucgla A, Moreso F, Muniesa C, Moreno A, Vidaller A. Cholesterol embolism: still an unrecognized entity with a high mortality rate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55:786–793.

- Kronzon I, Saric M. Cholesterol embolization syndrome. Circulation 2010; 122:631–641.

- Lye WC, Cheah JS, Sinniah R. Renal cholesterol embolic disease. Case report and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol 1993; 13:489–493.

- Nakayama M, Izumaru K, Nagata M, et al. The effect of low-dose corticosteroids on short- and long-term renal outcome in patients with cholesterol crystal embolism. Ren Fail 2011; 33:298–306.