User login

Necrotizing fasciitis after a watercraft accident

A 57-year-old man was transferred to our hospital with leg pain and confusion. His family reported that he had injured his leg while launching a motorized personal watercraft at the North Carolina seashore 2 days before. He had a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C and alcohol abuse.

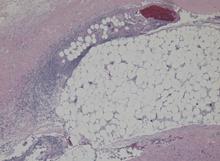

Blood and wound cultures eventually grew V vulnificus, and surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis (Figure 2).

RISE IN V VULNIFICUS INFECTIONS IS ATTRIBUTED TO GLOBAL WARMING

V vulnificus infection occurs most commonly from consuming raw shellfish, especially oysters, but it also occurs after exposure of an open wound to contaminated salt water. The pathogen is a gram-negative bacterium that resides in coastal waters worldwide, but in the United States it is usually seen on the Pacific and Gulf coasts1 during the summer.2

Although only 58 cases of V vulnificus infection were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1997, the number more than doubled to 124 in 2014.1 This rise is suspected to be due in part to warmer coastal waters associated with global warming.2

Various marine pathogens can cause wound infections, but V vulnificus is most commonly implicated in deaths and hospitalizations.2 Immunocompromised patients and those with liver disease are at particularly high risk of rapid progression to septic shock.

First-line antibiotics are doxycycline plus a third-generation cephalosporin.3 Studies have shown a direct correlation between delay of antibiotics and death,4 and early surgery is critical.5

Given the rising incidence of V vulnificus infection, it is increasingly important for providers across the United States to be aware of this infection.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National enteric disease surveillance: COVIS annual summary, 2014. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2014. www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/pdfs/covis-annual-summary-2014-508c.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Newton A, Kendall M, Vugia DJ, Henao OL, Mahon BE. Increasing rates of vibriosis in the United States, 1996–2010: review of surveillance data from 2 systems. Clinl Infect Dis 2012; 54(suppl 5):S391–S395. doi:10.1093/cid/cis243

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59(2):147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444

- Klontz KC, Lieb S, Schreiber M, Janowski HT, Baldy LM, Gunn RA. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida cases, 1981-1987. Ann Intern Med 1988; 109:318–323. pmid:3260760

- Chao WN, Tsai CF, Chang HR, et al. Impact of timing of surgery on outcome of Vibrio vulnificus-related necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg 2013; 206(1):32–39. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.08.008

A 57-year-old man was transferred to our hospital with leg pain and confusion. His family reported that he had injured his leg while launching a motorized personal watercraft at the North Carolina seashore 2 days before. He had a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C and alcohol abuse.

Blood and wound cultures eventually grew V vulnificus, and surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis (Figure 2).

RISE IN V VULNIFICUS INFECTIONS IS ATTRIBUTED TO GLOBAL WARMING

V vulnificus infection occurs most commonly from consuming raw shellfish, especially oysters, but it also occurs after exposure of an open wound to contaminated salt water. The pathogen is a gram-negative bacterium that resides in coastal waters worldwide, but in the United States it is usually seen on the Pacific and Gulf coasts1 during the summer.2

Although only 58 cases of V vulnificus infection were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1997, the number more than doubled to 124 in 2014.1 This rise is suspected to be due in part to warmer coastal waters associated with global warming.2

Various marine pathogens can cause wound infections, but V vulnificus is most commonly implicated in deaths and hospitalizations.2 Immunocompromised patients and those with liver disease are at particularly high risk of rapid progression to septic shock.

First-line antibiotics are doxycycline plus a third-generation cephalosporin.3 Studies have shown a direct correlation between delay of antibiotics and death,4 and early surgery is critical.5

Given the rising incidence of V vulnificus infection, it is increasingly important for providers across the United States to be aware of this infection.

A 57-year-old man was transferred to our hospital with leg pain and confusion. His family reported that he had injured his leg while launching a motorized personal watercraft at the North Carolina seashore 2 days before. He had a history of cirrhosis secondary to hepatitis C and alcohol abuse.

Blood and wound cultures eventually grew V vulnificus, and surgical pathology confirmed the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis (Figure 2).

RISE IN V VULNIFICUS INFECTIONS IS ATTRIBUTED TO GLOBAL WARMING

V vulnificus infection occurs most commonly from consuming raw shellfish, especially oysters, but it also occurs after exposure of an open wound to contaminated salt water. The pathogen is a gram-negative bacterium that resides in coastal waters worldwide, but in the United States it is usually seen on the Pacific and Gulf coasts1 during the summer.2

Although only 58 cases of V vulnificus infection were reported to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 1997, the number more than doubled to 124 in 2014.1 This rise is suspected to be due in part to warmer coastal waters associated with global warming.2

Various marine pathogens can cause wound infections, but V vulnificus is most commonly implicated in deaths and hospitalizations.2 Immunocompromised patients and those with liver disease are at particularly high risk of rapid progression to septic shock.

First-line antibiotics are doxycycline plus a third-generation cephalosporin.3 Studies have shown a direct correlation between delay of antibiotics and death,4 and early surgery is critical.5

Given the rising incidence of V vulnificus infection, it is increasingly important for providers across the United States to be aware of this infection.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National enteric disease surveillance: COVIS annual summary, 2014. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2014. www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/pdfs/covis-annual-summary-2014-508c.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Newton A, Kendall M, Vugia DJ, Henao OL, Mahon BE. Increasing rates of vibriosis in the United States, 1996–2010: review of surveillance data from 2 systems. Clinl Infect Dis 2012; 54(suppl 5):S391–S395. doi:10.1093/cid/cis243

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59(2):147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444

- Klontz KC, Lieb S, Schreiber M, Janowski HT, Baldy LM, Gunn RA. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida cases, 1981-1987. Ann Intern Med 1988; 109:318–323. pmid:3260760

- Chao WN, Tsai CF, Chang HR, et al. Impact of timing of surgery on outcome of Vibrio vulnificus-related necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg 2013; 206(1):32–39. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.08.008

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National enteric disease surveillance: COVIS annual summary, 2014. US Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2014. www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/pdfs/covis-annual-summary-2014-508c.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2018.

- Newton A, Kendall M, Vugia DJ, Henao OL, Mahon BE. Increasing rates of vibriosis in the United States, 1996–2010: review of surveillance data from 2 systems. Clinl Infect Dis 2012; 54(suppl 5):S391–S395. doi:10.1093/cid/cis243

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59(2):147-159. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444

- Klontz KC, Lieb S, Schreiber M, Janowski HT, Baldy LM, Gunn RA. Syndromes of Vibrio vulnificus infections. Clinical and epidemiologic features in Florida cases, 1981-1987. Ann Intern Med 1988; 109:318–323. pmid:3260760

- Chao WN, Tsai CF, Chang HR, et al. Impact of timing of surgery on outcome of Vibrio vulnificus-related necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg 2013; 206(1):32–39. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.08.008