User login

Atypical Intrathoracic Manifestations of Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Case Series

Atypical Intrathoracic Manifestations of Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Case Series

Prostate cancer is the most common noncutaneous cancer in men, accounting for 29% of all incident cancer cases.1 Typically, prostate cancer metastasizes to bone and regional lymph nodes.2 However, intrathoracic manifestation may occur. This report presents 3 cases of rare intrathoracic manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer with a review of the current literature.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

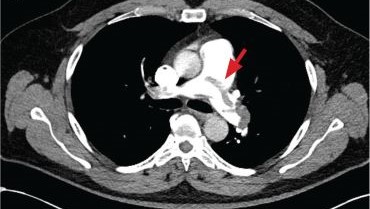

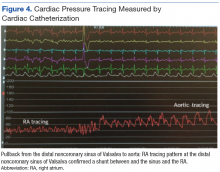

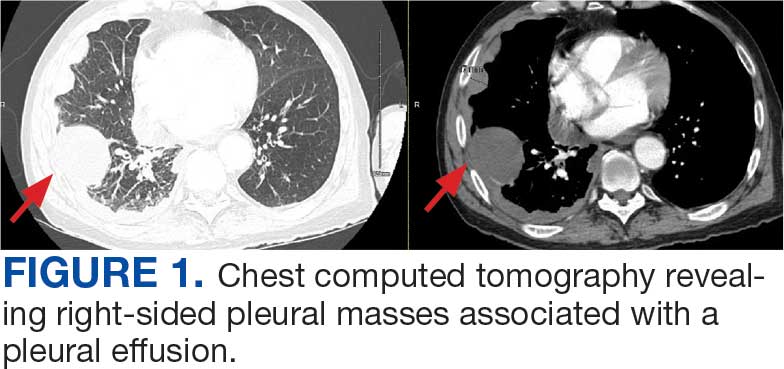

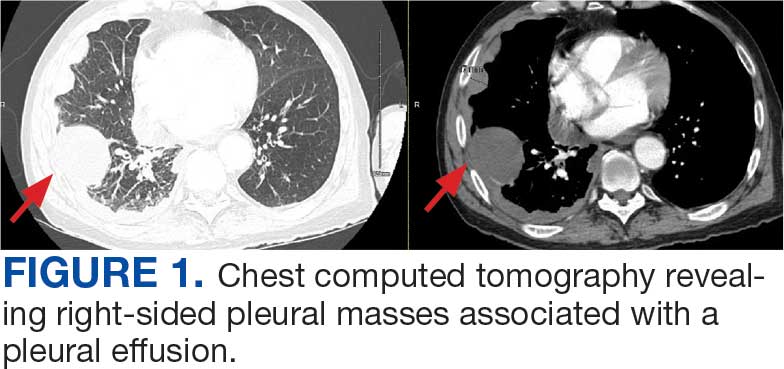

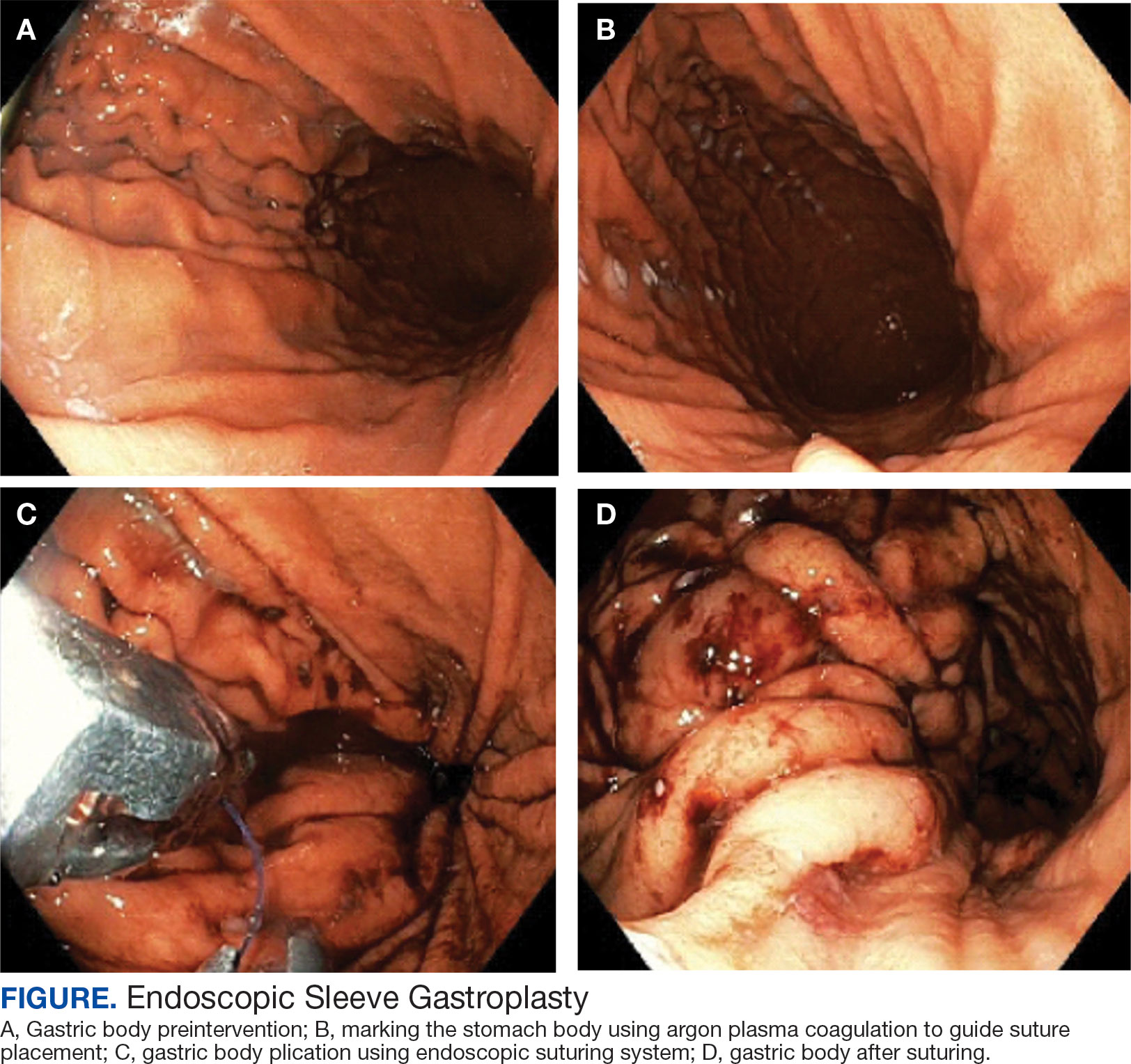

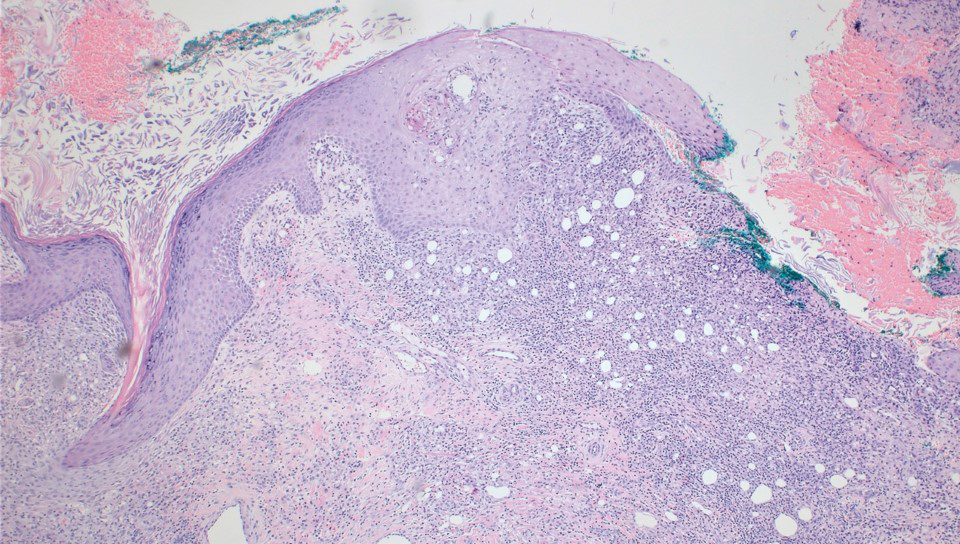

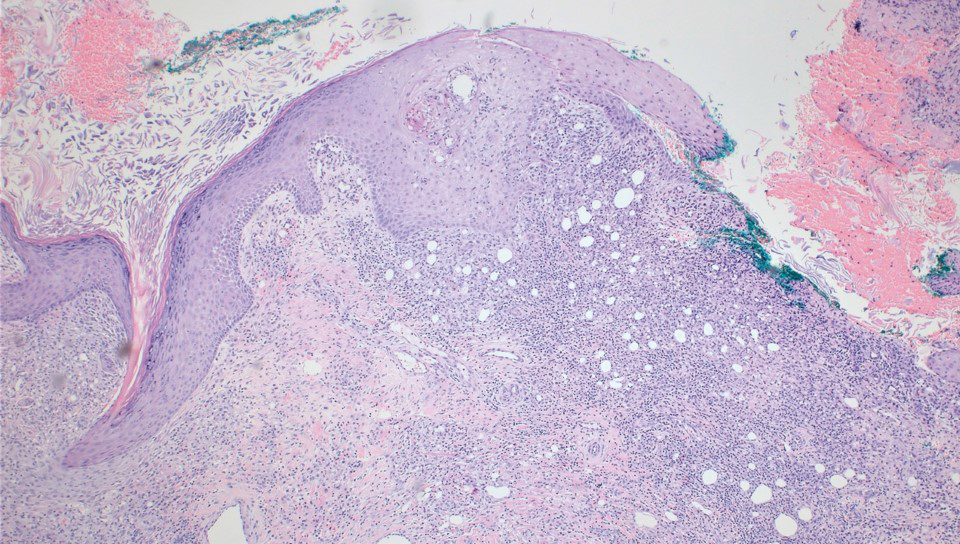

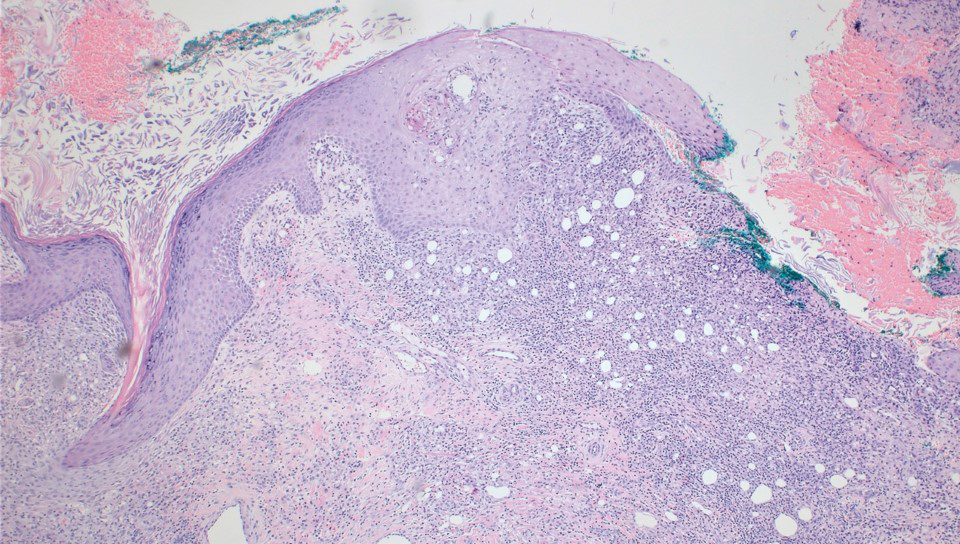

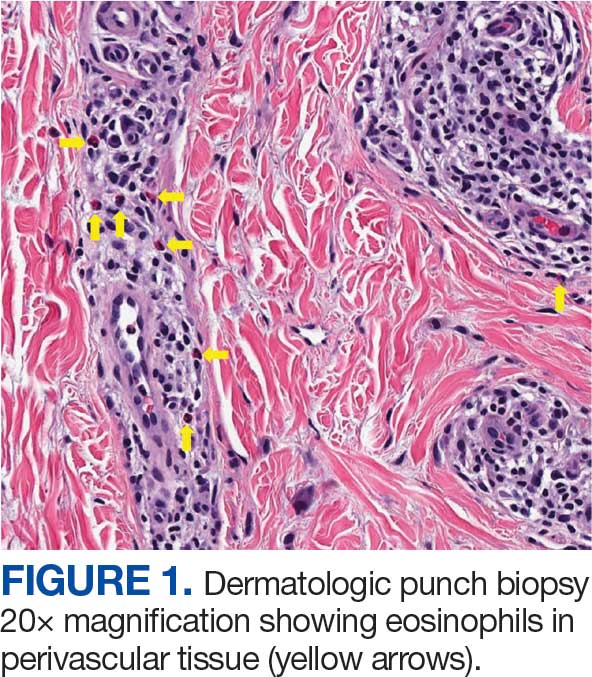

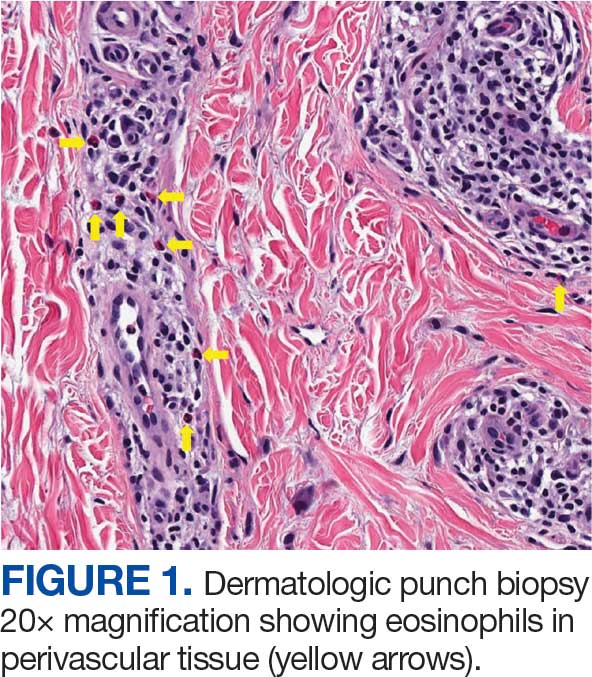

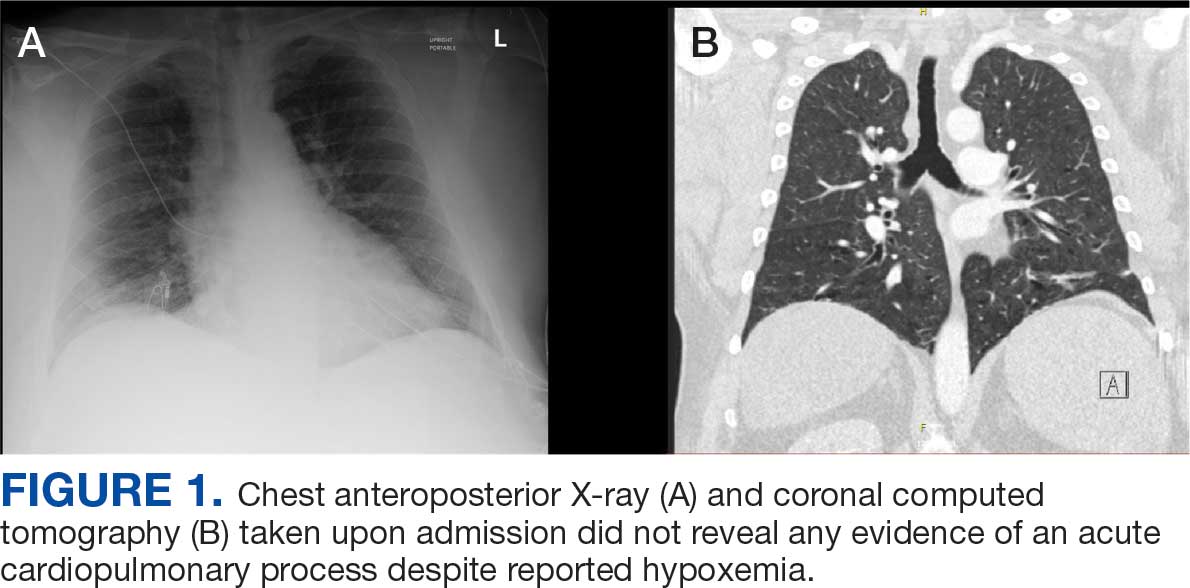

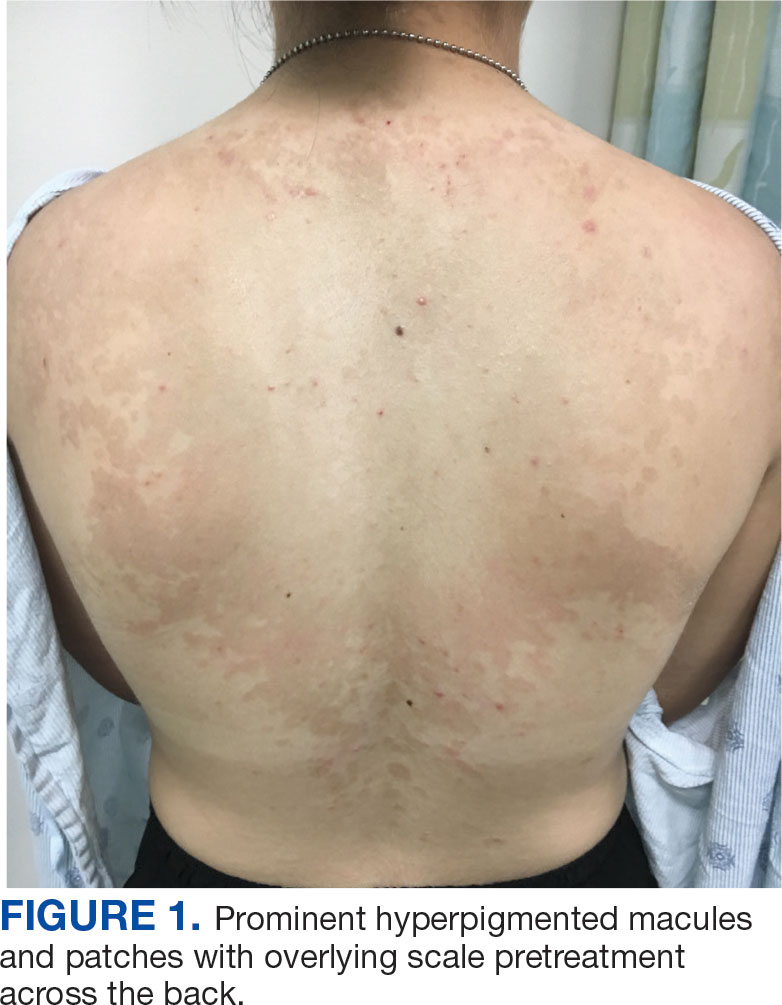

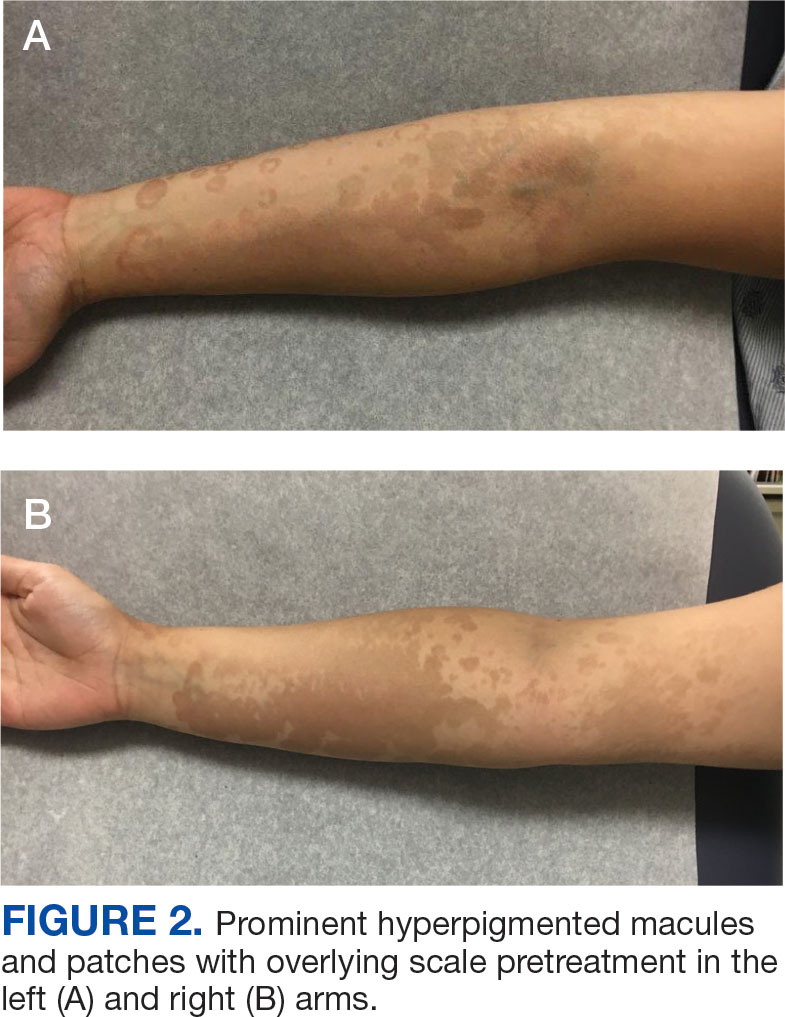

A 71-year-old male who was an active smoker and a long-standing employment as a plumber was diagnosed with rectal cancer in 2022. He completed neoadjuvant capecitabine and radiation therapy followed by a rectosigmoidectomy. Several weeks after surgery, the patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with a dry cough and worsening shortness of breath. Point-of-care ultrasound of the lungs revealed a moderate right pleural effusion with several nodular pleural masses. A chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed these findings (Figure 1). A CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed prostatomegaly with the medial lobe of the prostate protruding into the bladder; however, no enlarged retroperitoneal, mesenteric or pelvic lymph nodes were noted. The patient underwent a right pleural fluid drainage and pleural mass biopsy. Pleural mass histomorphology as well as immunohistochemical (IHC) stains were consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. The pleural fluid cytology also was consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma.

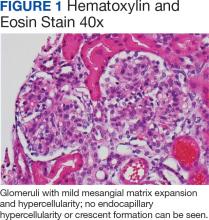

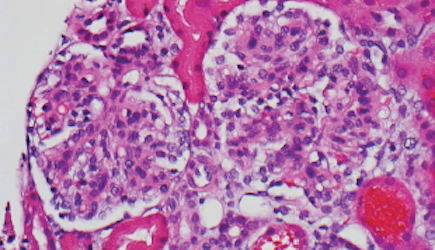

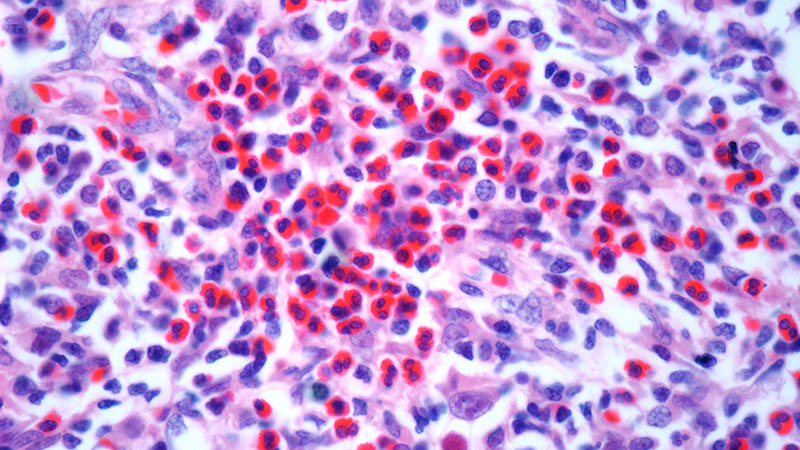

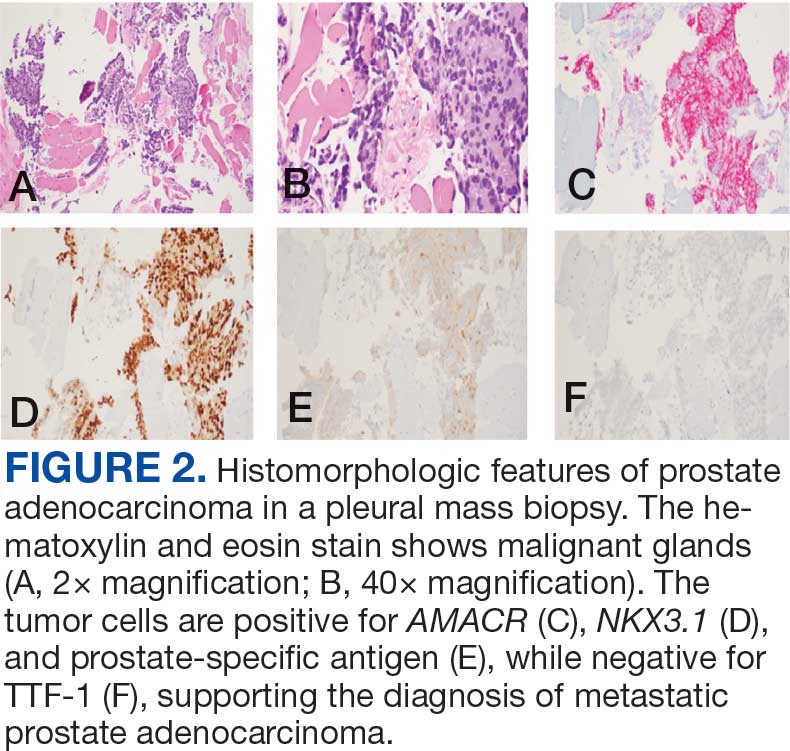

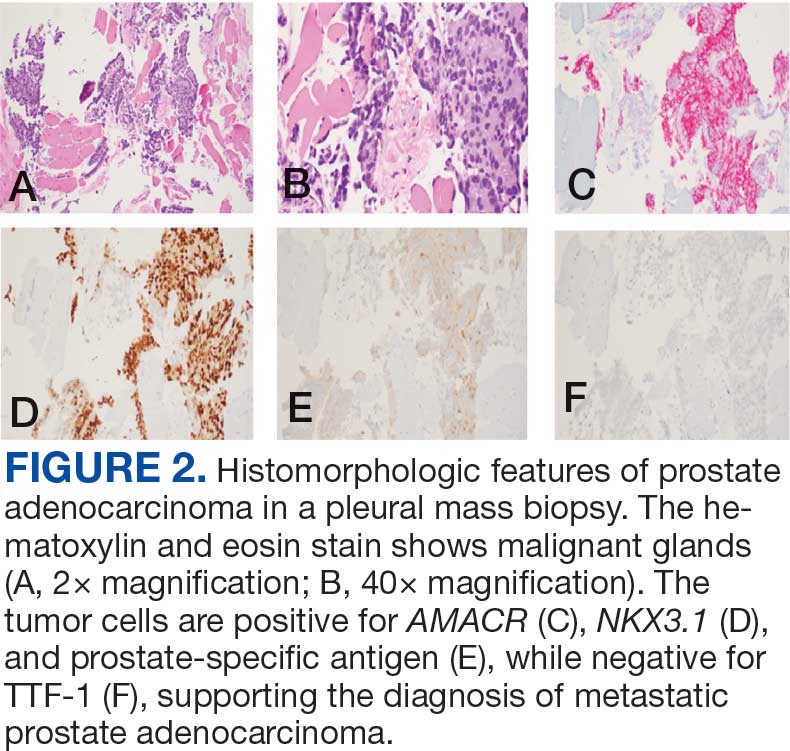

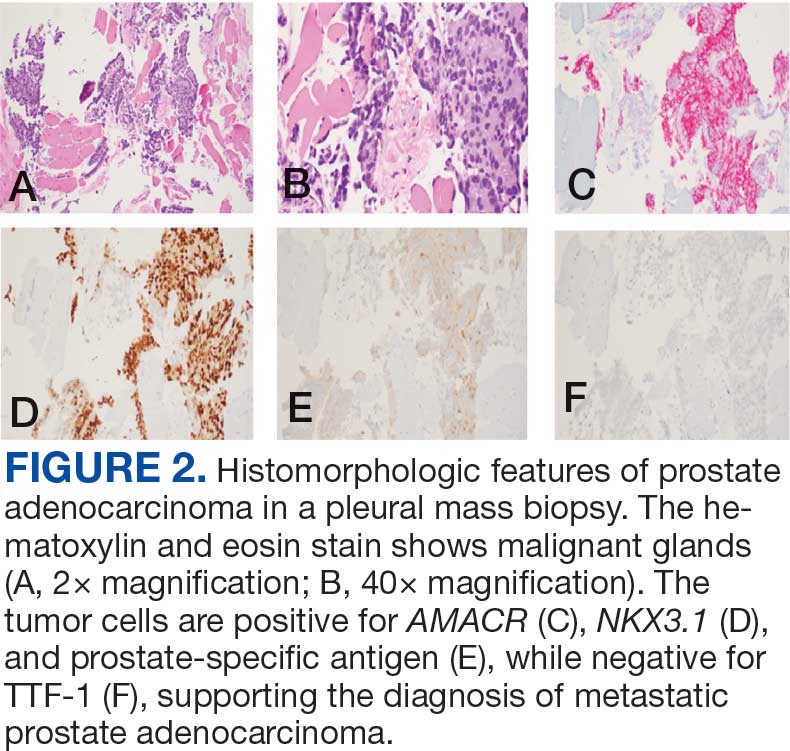

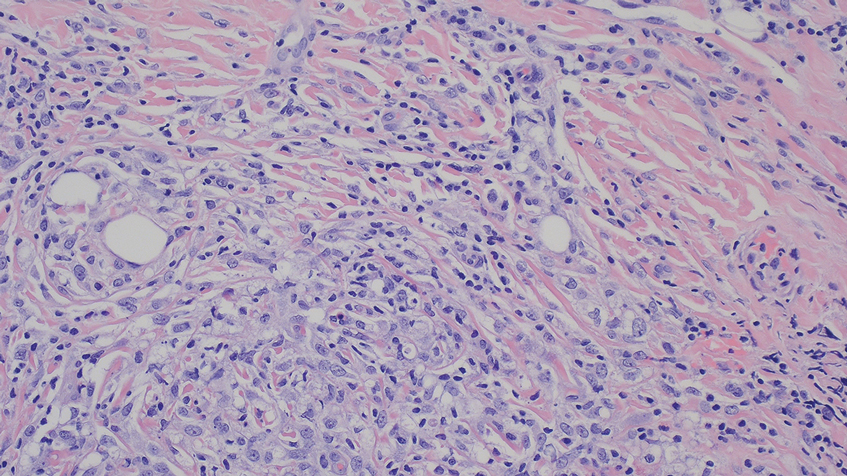

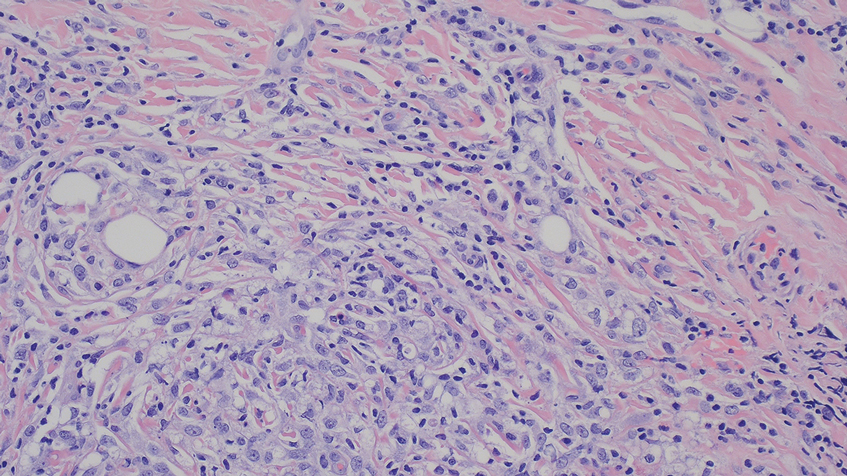

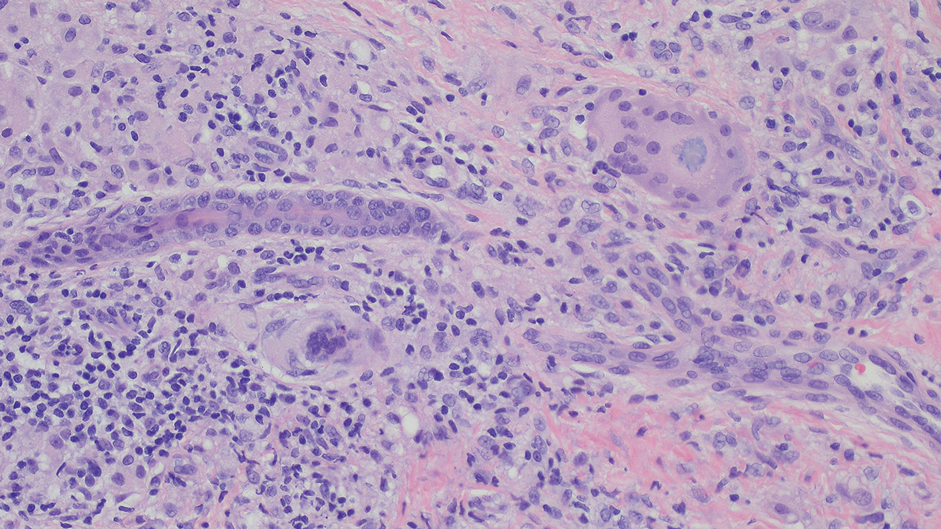

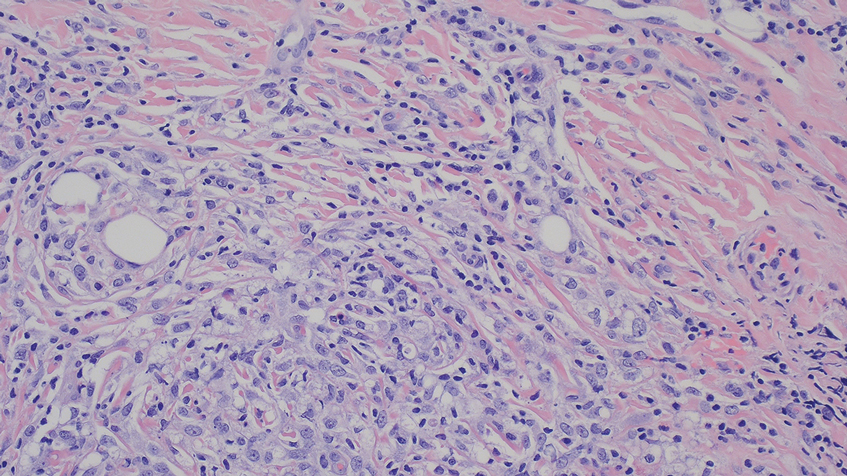

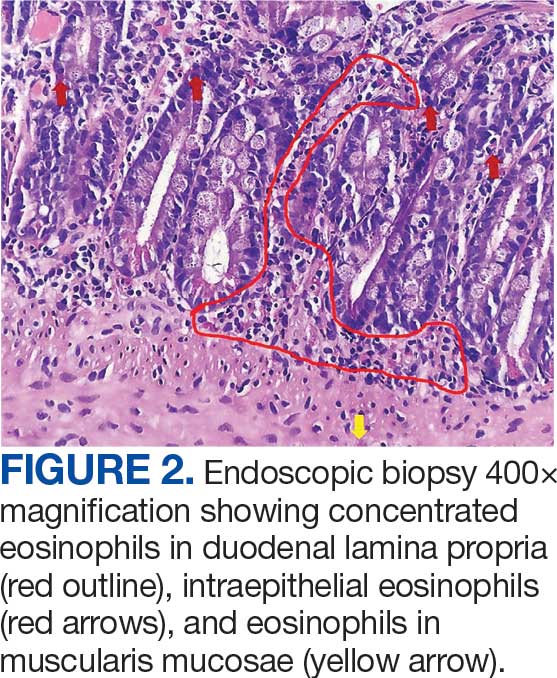

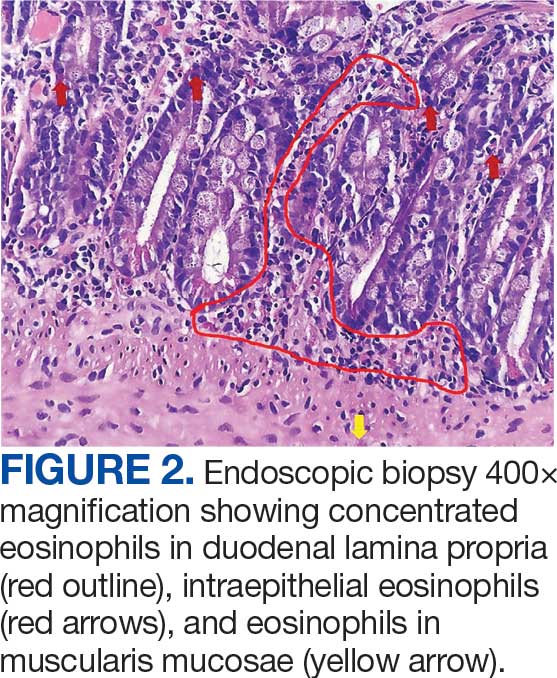

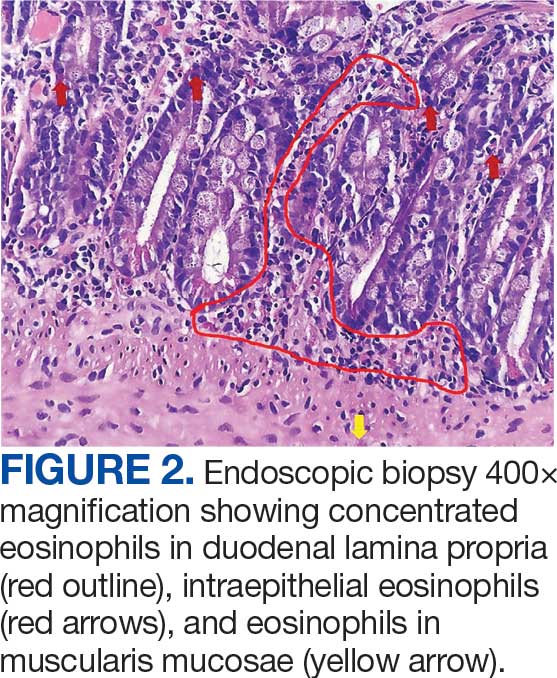

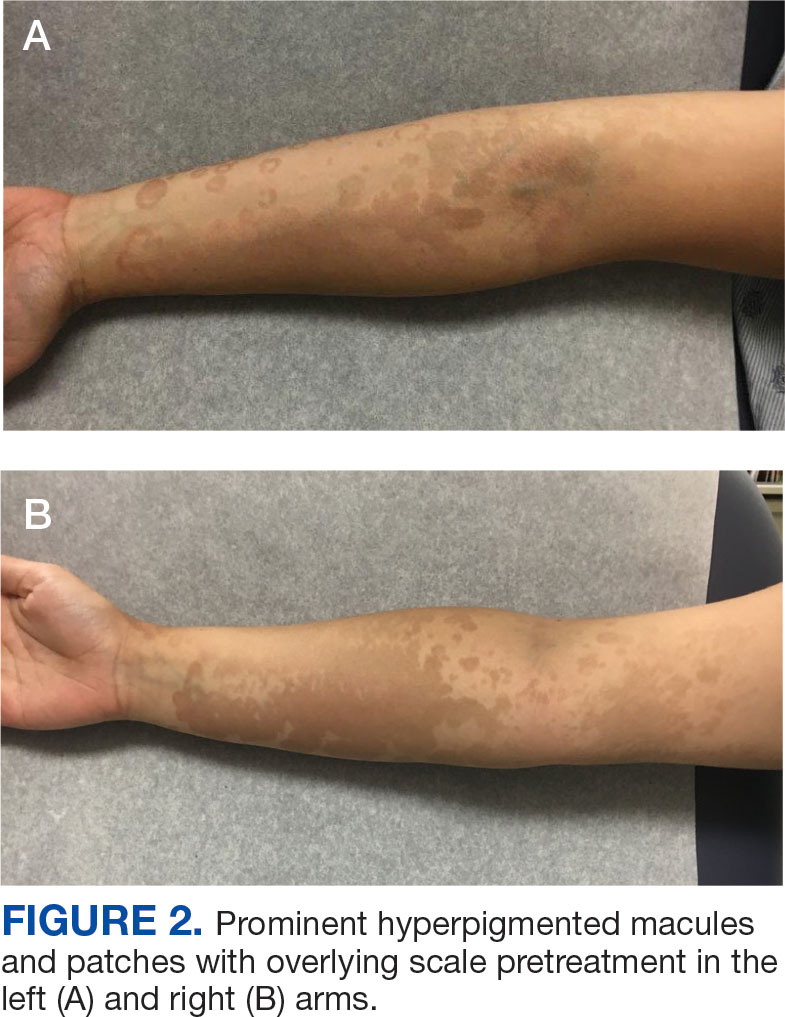

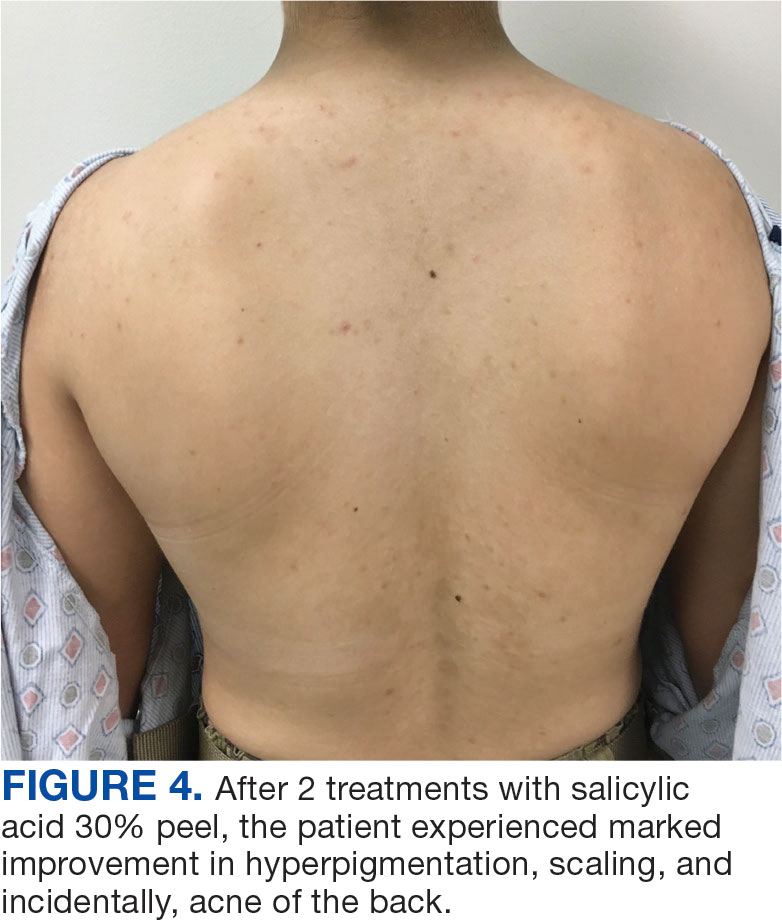

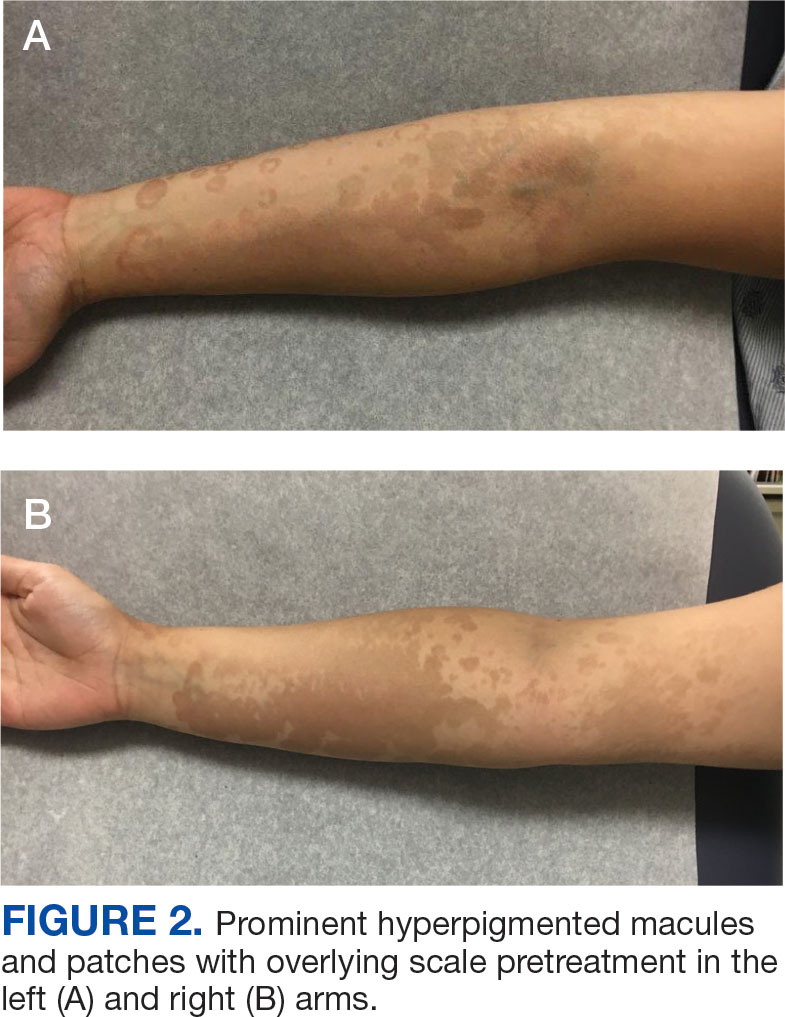

Immunohistochemistry showed weak positive staining for prostate-specific NK3 homeobox 1 gene (NKX3.1), alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase gene (AMACR), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), keratin-20, and caudal type homeobox 2 gene (CDX2) (Figure 2) 2). The patient's prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was found to be elevated at 33.9 ng/mL (reference range, < 4 ng/mL).

Case 2

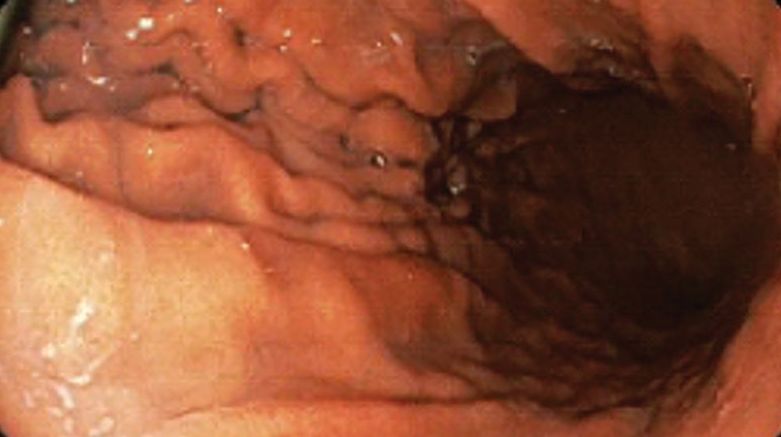

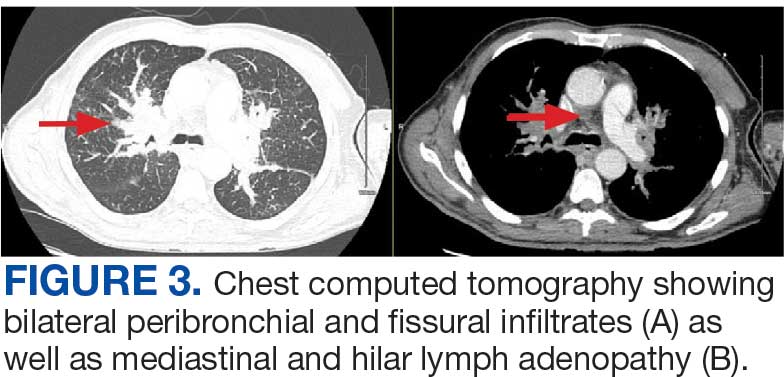

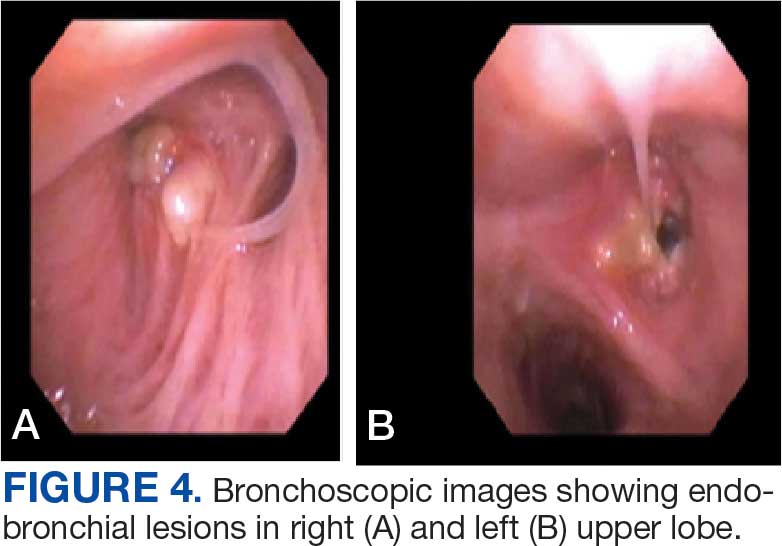

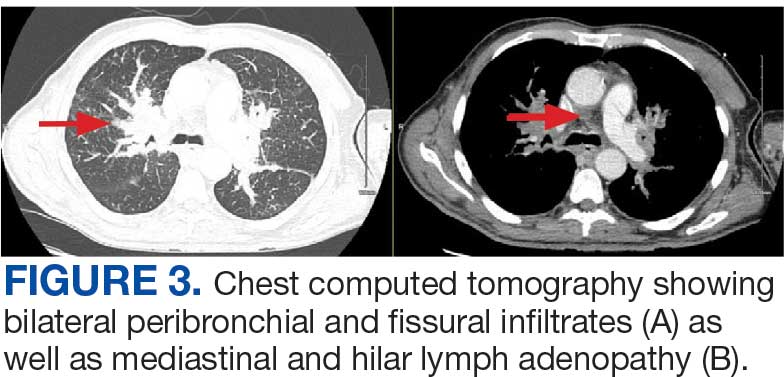

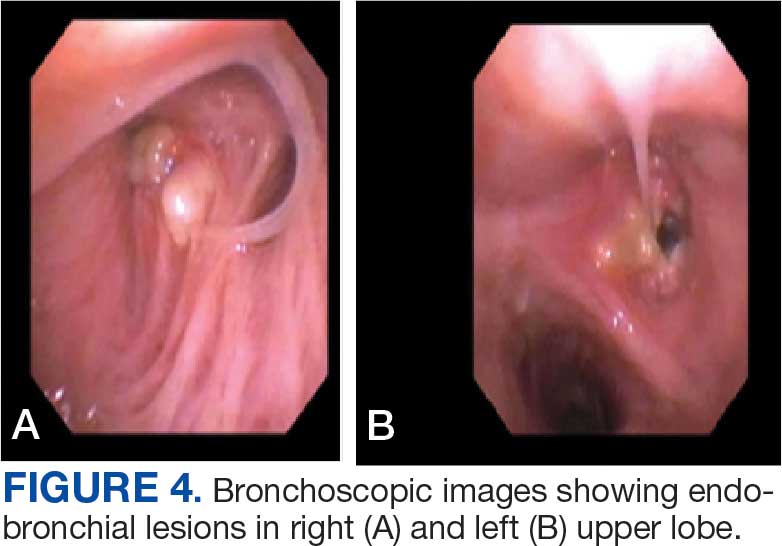

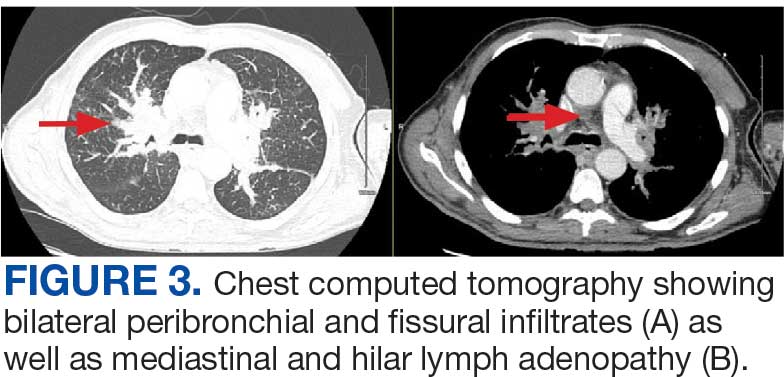

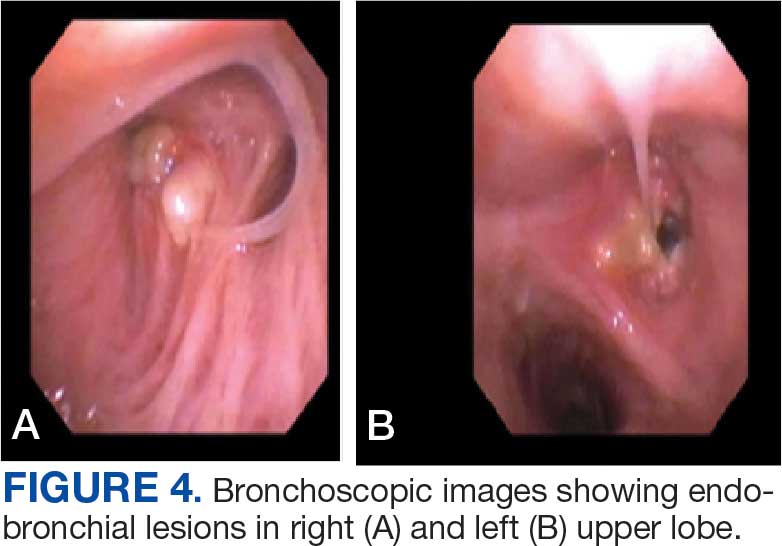

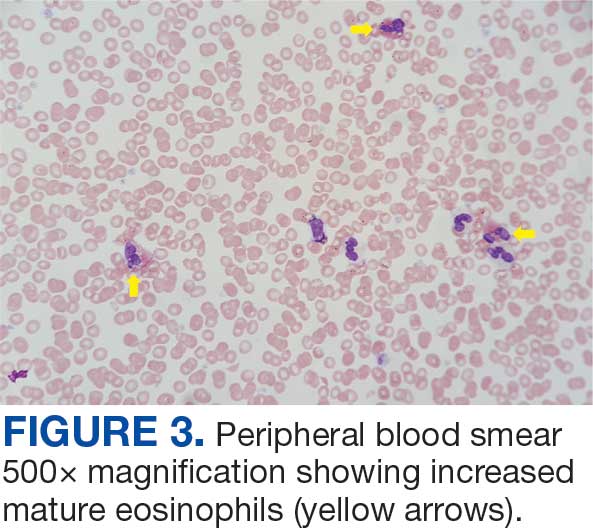

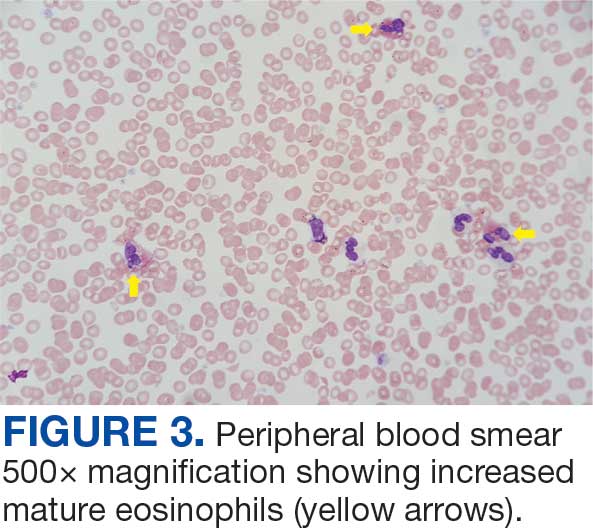

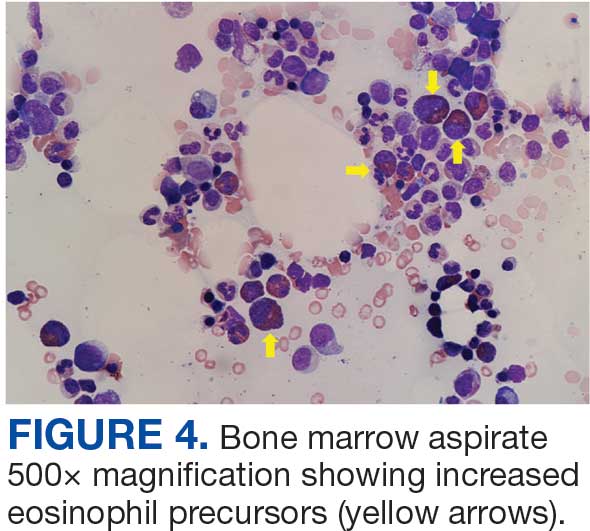

A 71-year-old male with a history of alcohol use disorder and a 30-year smoking history presented to the ED with worsening dyspnea on exertion. The patient’s baseline exercise tolerance decreased to walking for only 1 block. He reported unintentional weight loss of about 30 pounds over the prior year, no recent respiratory infections, no prior breathing problems, and no personal or family history of cancer. Chest CT revealed findings of bilateral peribronchial opacities as well as mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy (Figure 3). The patient developed hypoxic respiratory failure necessitating intubation, mechanical ventilation, and management in the medical intensive care unit, where he was treated for postobstructive pneumonia. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed endobronchial lesions in the right and left upper lobe that were partially obstructing the airway (Figure 4).

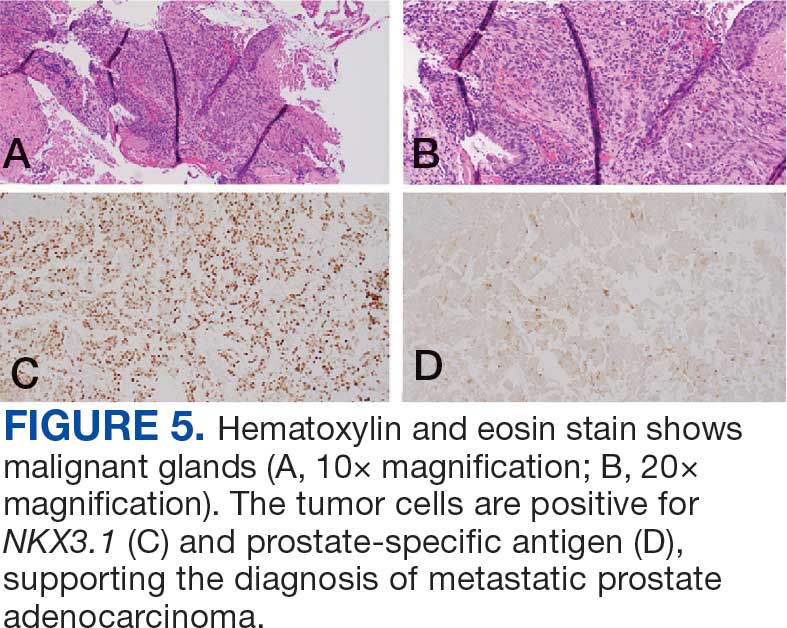

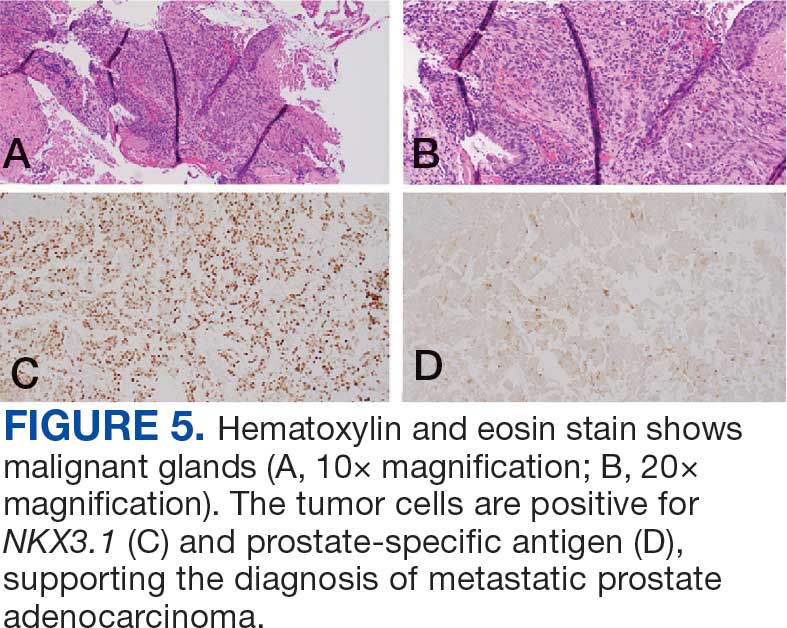

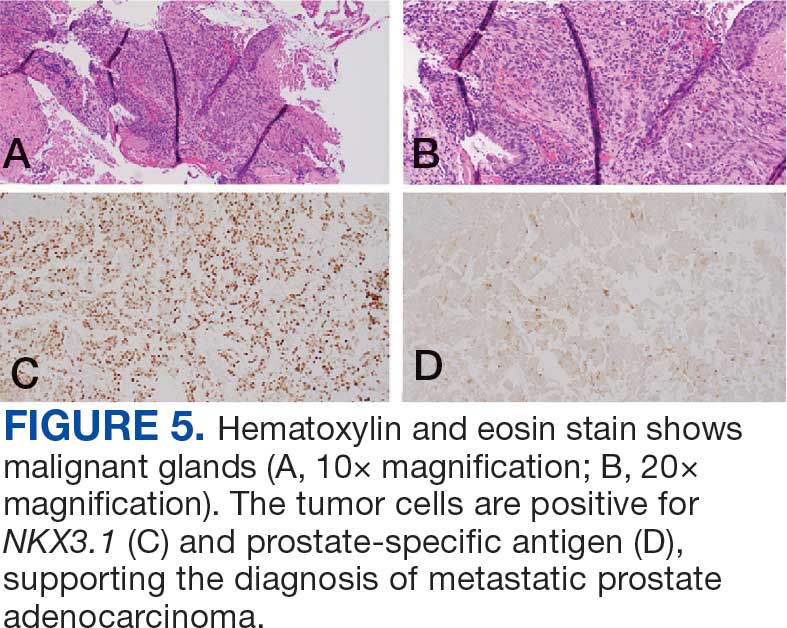

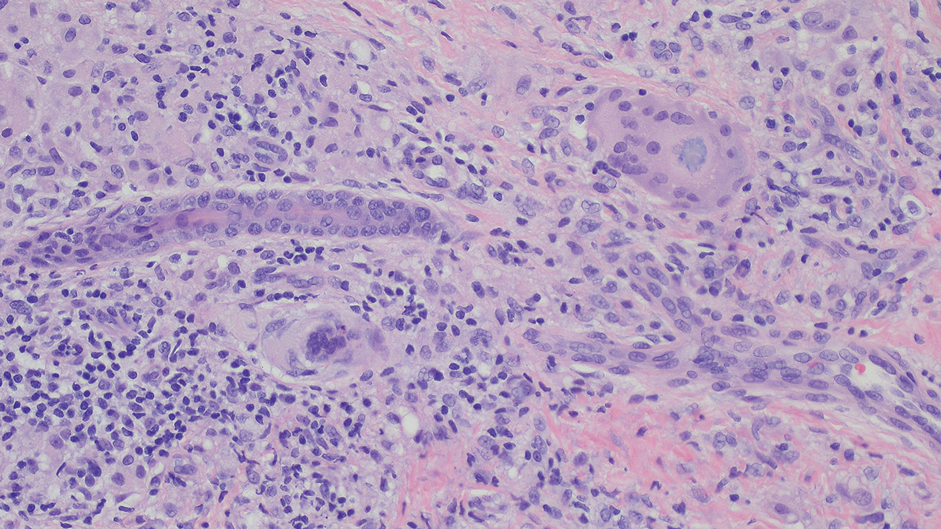

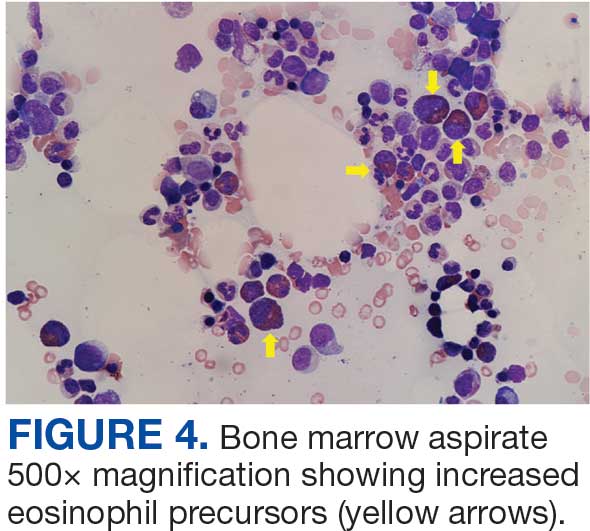

The endobronchial masses were debulked using forceps, and samples were sent for surgical pathology evaluation. Staging was completed using linear endobronchial ultrasound, which revealed an enlarged subcarinal lymph node (S7). The surgical pathology of the endobronchial mass and the subcarinal lymph node cytology were consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate. The tumor cells were positive for AE1/AE3, PSA, and NKX3.1, but were negative for CK7 and TTF-1 (Figure 5). Further imaging revealed an enlarged heterogeneous prostate gland, prominent pelvic nodes, and left retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, as well as sclerotic foci within the T10 vertebral body and right inferior pubic ramus. PSA was also found to be significantly elevated at 700 ng/mL.

Case 3

An 80-year-old male veteran with a history of prostate cancer and recently diagnosed T2N1M0 head and neck squamous cell carcinoma was referred to the Pulmonary service for evaluation of a pulmonary nodule. His medical history was notable for prostate cancer diagnosed 12 years earlier, with an unknown Gleason score. Initial treatment included prostatectomy followed by whole pelvic radiation therapy a year after, due to elevated PSA in surveillance monitoring. This treatment led to remission. After establishing remission for > 10 years, the patient was started on low-dose testosterone replacement therapy to address complications of radiation therapy, namely hypogonadism.

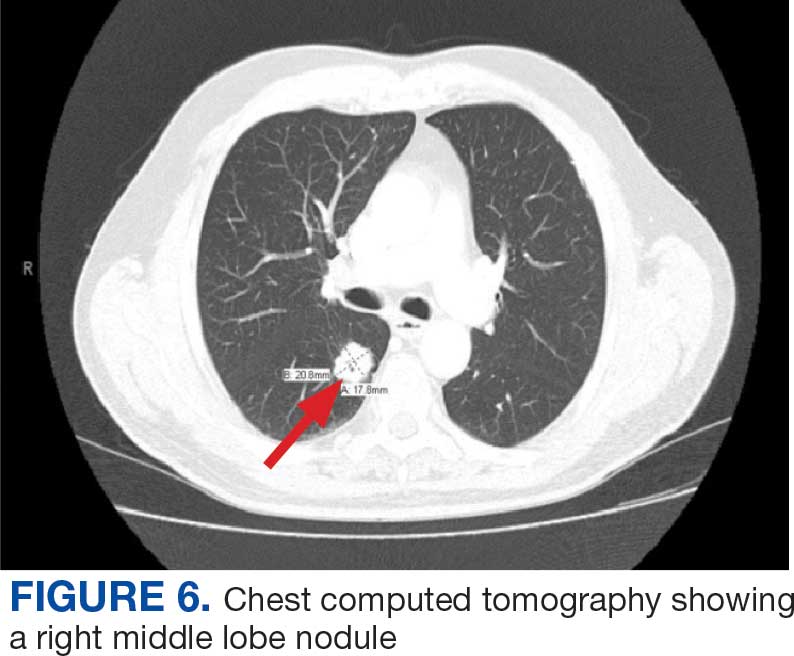

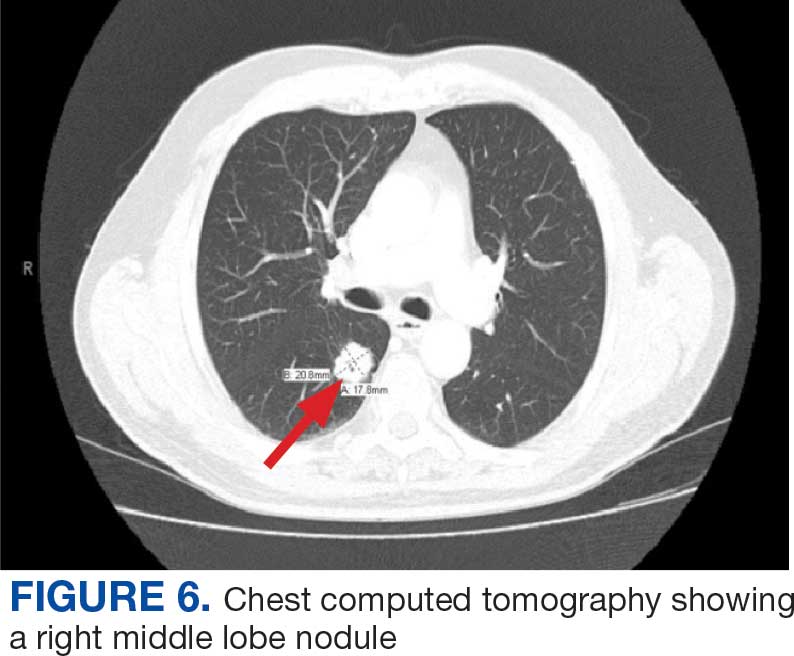

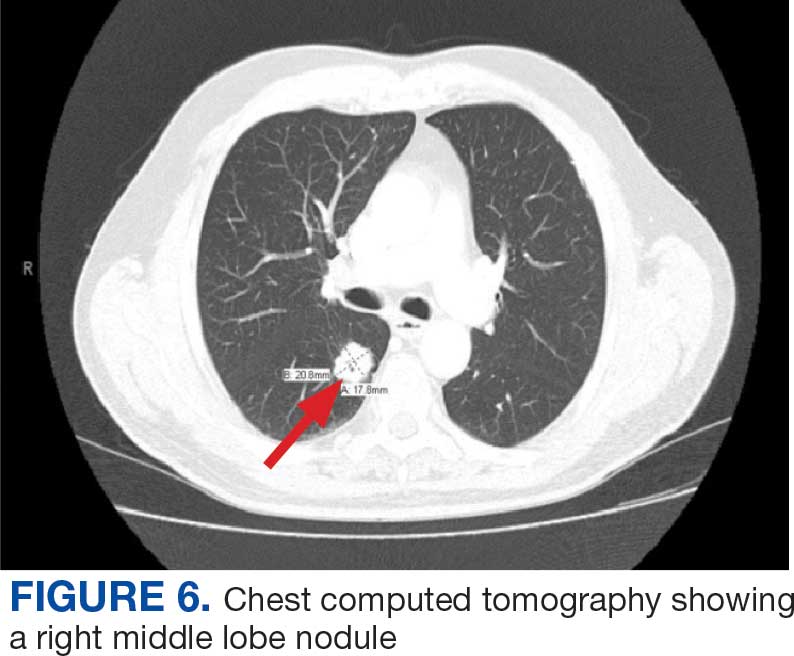

On evaluation, a chest CT was significant for a large 2-cm right middle lobe nodule (Figure 6). At that time, PSA was noted to be borderline elevated at 4.2 ng/mL, and whole-body imaging did not reveal any lesions elsewhere, specifically no bone metastasis. Biopsies of the right middle lobe lung nodule revealed adenocarcinoma consistent with metastatic prostate cancer. Testosterone therapy was promptly discontinued.

The patient initially refused androgen deprivation therapy owing to the antiandrogenic adverse effects. However, subsequent chest CTs revealed growing lung nodules, which convinced him to proceed with androgen deprivation therapy followed by palliative radiation, and chemotherapy and management of malignant pleural effusion with indwelling small bore pleural catheter for about 10 years. He died from COVID-19 during the pandemic.

DISCUSSION

These cases highlight the importance of including prostate cancer in the differential diagnoses of male patients with intrathoracic abnormalities, even in the absence of metastasis to the more common sites. In a large cohort study of 74,826 patients with metastatic prostate cancer, Gandaglia et al found that the most frequent sites of metastasis were bone (84.0%) and distant lymph nodes (10.6%).2 However, thoracic involvement was observed in 9.1% of cases, with isolated thoracic metastasis being rare. The cases described in this report exemplify exceptionally uncommon occurrences within that 9.1%.

Pleural metastases, as observed in Case 1, are a particularly rare manifestation. In a 10-year retrospective assessment, Vinjamoori et al discovered pleural nodules or masses in only 6 of 82 patients (7.3%) with atypical metastases.3 Adrenal and liver metastases accounted for 15% and 37% of cases with atypical distribution. As such, isolated pleural disease is rare even in atypical presentations.3

As seen in Case 2, endobronchial metastases producing airway obstruction are also rare, with the most common primary cancers associated with endobronchial metastasis being breast, colon, and renal cancer.4 The available literature on this presentation is confined to case reports. Hameed et al reported a case of synchronous biopsy-proven endobronchial metastasis from prostate cancer.5 These cases highlight the importance of maintaining a high level of clinical awareness when encountering endobronchial lesions in patients with prostate cancer.

Case 3 presents a unique situation of lung metastases without any involvement of the bones. It is well known—and was confirmed by Heidenreich et al—that lung metastases in prostate adenocarcinoma usually coincide with extensive osseous disease.6 This instance highlights the importance of watchful monitoring for unusual patterns of cancer recurrence.

Immunohistochemistry stains that are specific to prostate cancer include antibodies against PSA. Prostate-specific membrane antigen is another marker that is far more present in malignant than in benign prostate tissue.

The NKX3.1 gene encodes a homeobox protein, which is a transcription factor and tumor suppressor. In prostate cancer, there is loss of heterozygosity of the gene and stains for the IHC antibody to NKX3.1.7

On the other hand, lung cells stain positive for TTF-1, which is produced by surfactant-producing type 2 pneumocytes and club cells in the lung. Antibodies to TTF-1, a common IHC stain, are used to identify adenocarcinoma of lung origin and may carry a prognostic value.7

The immunohistochemistry profiles, specifically the presence of prostate-specific markers such as PSA and NKX3.1, played a vital role in making the diagnosis.

In Case 1, weak TTF-1 positivity was noted, an unusual finding in metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Marak et al documented a rare case of TTF-1–positive metastatic prostate cancer, illustrating the potential for diagnostic confusion with primary lung malignancies.8

The 3 cases described in this report demonstrate the importance of clinical consideration, serial follow-up of PSA levels, using more prostate-specific positron emission tomography tracers (eg, Pylarify) alongside traditional imaging, and tissue biopsy to detect unusual metastases.

CONCLUSIONS

Although thoracic metastases from prostate cancer are rare, these presentations highlight the importance of clinical awareness regarding atypical cases. Pleural disease, endobronchial lesions, and isolated pulmonary nodules might be the first clinical manifestation of metastatic prostate cancer. A high index of suspicion, appropriate imaging, and judicious use of immunohistochemistry are important to ensure accurate diagnosis and optimal patient management.

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12-49. doi:10.3322/caac.21820

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74(2):210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Vinjamoori AH, Jagannathan JP, Shinagare AB, et al. Atypical metastases from prostate cancer: 10-year experience at a single institution. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(2):367-372. doi:10.2214/AJR.11.7533

- Salud A, Porcel JM, Rovirosa A, Bellmunt J. Endobronchial metastatic disease: analysis of 32 cases. J Surg Oncol. 1996;62(4):249-252. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096- 9098(199608)62:4<249::AID-JSO4>3.0.CO;2-6

- Hameed M, Haq IU, Yousaf M, Hussein M, Rashid U, Al-Bozom I. Endobronchial metastases secondary to prostate cancer: a case report and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020;32:101326. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101326

- Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al; for the European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration- resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65(2):467- 479. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.002

- Schallenberg S, Dernbach G, Dragomir MP, et al. TTF-1 status in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma is an independent predictor of relapse and survival superior to tumor grading. Eur J Cancer. 2024;197:113474. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113474

- Marak C, Guddati AK, Ashraf A, Smith J, Kaushik P. Prostate adenocarcinoma with atypical immunohistochemistry presenting with a Cheerio sign. AIM Clinical Cases. 2023;1:e220508. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0508

Prostate cancer is the most common noncutaneous cancer in men, accounting for 29% of all incident cancer cases.1 Typically, prostate cancer metastasizes to bone and regional lymph nodes.2 However, intrathoracic manifestation may occur. This report presents 3 cases of rare intrathoracic manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer with a review of the current literature.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

A 71-year-old male who was an active smoker and a long-standing employment as a plumber was diagnosed with rectal cancer in 2022. He completed neoadjuvant capecitabine and radiation therapy followed by a rectosigmoidectomy. Several weeks after surgery, the patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with a dry cough and worsening shortness of breath. Point-of-care ultrasound of the lungs revealed a moderate right pleural effusion with several nodular pleural masses. A chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed these findings (Figure 1). A CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed prostatomegaly with the medial lobe of the prostate protruding into the bladder; however, no enlarged retroperitoneal, mesenteric or pelvic lymph nodes were noted. The patient underwent a right pleural fluid drainage and pleural mass biopsy. Pleural mass histomorphology as well as immunohistochemical (IHC) stains were consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. The pleural fluid cytology also was consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma.

Immunohistochemistry showed weak positive staining for prostate-specific NK3 homeobox 1 gene (NKX3.1), alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase gene (AMACR), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), keratin-20, and caudal type homeobox 2 gene (CDX2) (Figure 2) 2). The patient's prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was found to be elevated at 33.9 ng/mL (reference range, < 4 ng/mL).

Case 2

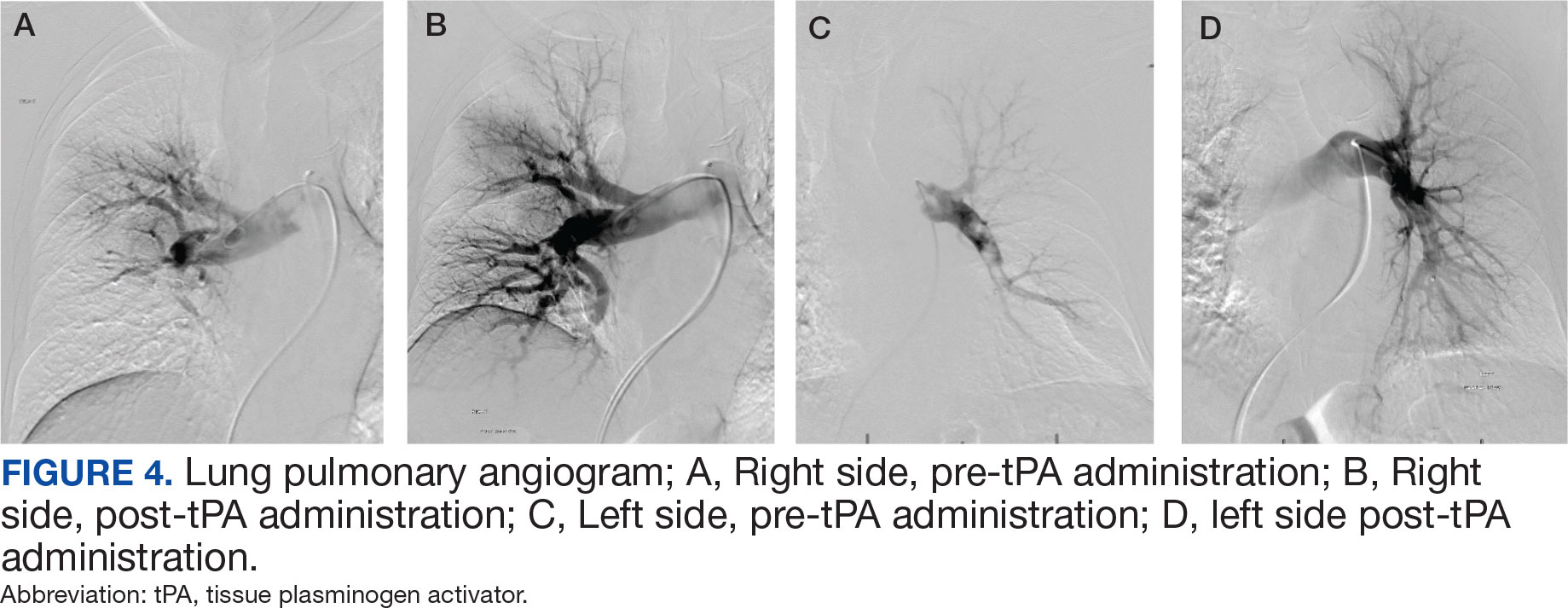

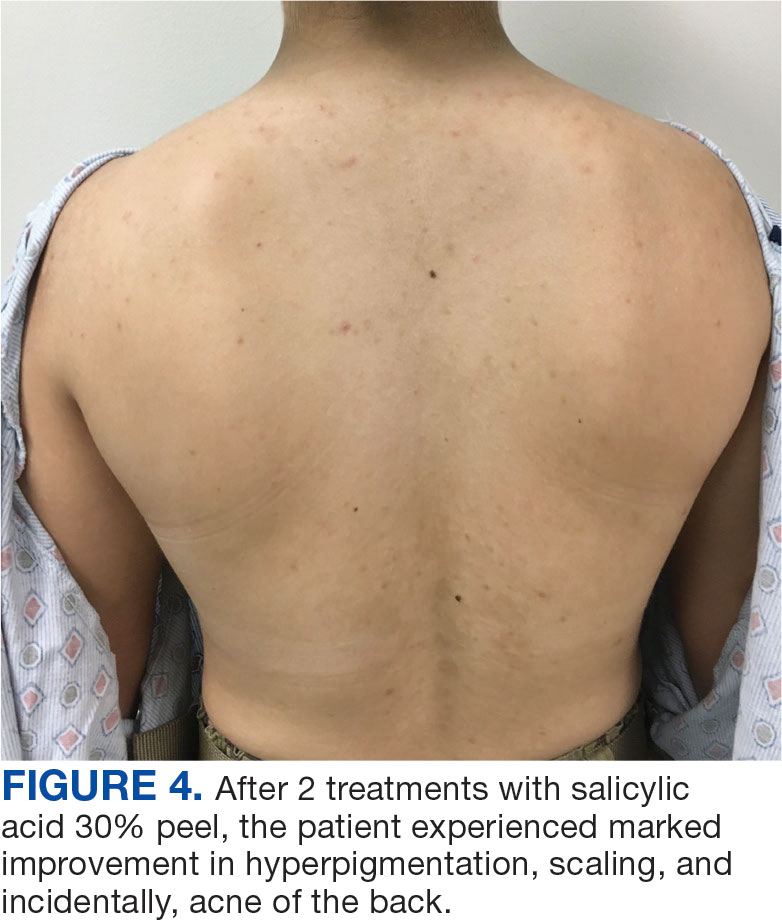

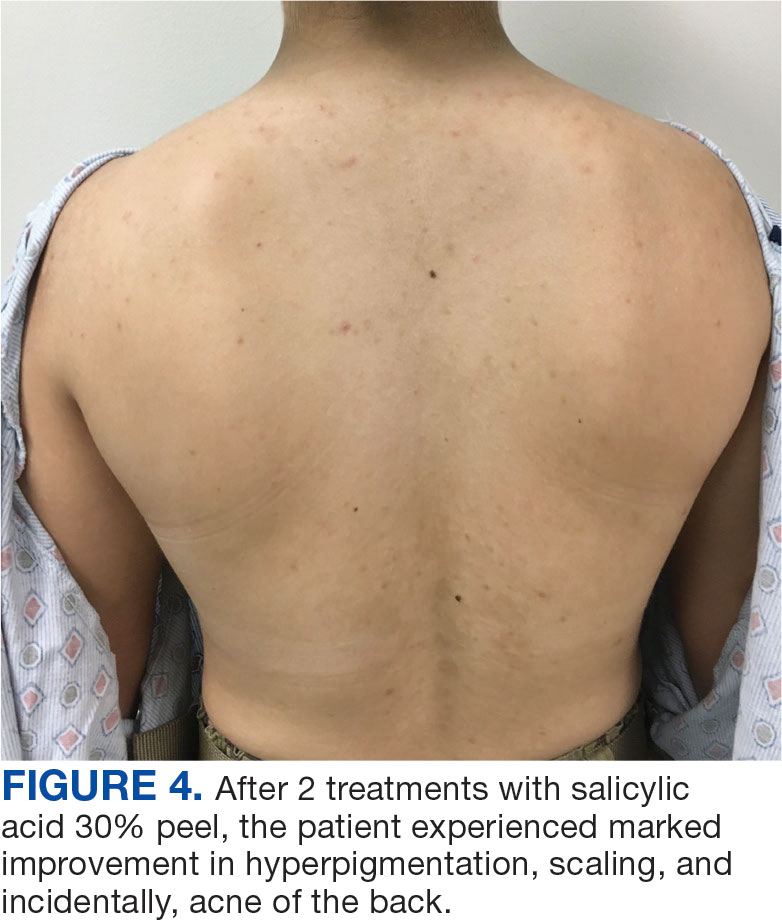

A 71-year-old male with a history of alcohol use disorder and a 30-year smoking history presented to the ED with worsening dyspnea on exertion. The patient’s baseline exercise tolerance decreased to walking for only 1 block. He reported unintentional weight loss of about 30 pounds over the prior year, no recent respiratory infections, no prior breathing problems, and no personal or family history of cancer. Chest CT revealed findings of bilateral peribronchial opacities as well as mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy (Figure 3). The patient developed hypoxic respiratory failure necessitating intubation, mechanical ventilation, and management in the medical intensive care unit, where he was treated for postobstructive pneumonia. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed endobronchial lesions in the right and left upper lobe that were partially obstructing the airway (Figure 4).

The endobronchial masses were debulked using forceps, and samples were sent for surgical pathology evaluation. Staging was completed using linear endobronchial ultrasound, which revealed an enlarged subcarinal lymph node (S7). The surgical pathology of the endobronchial mass and the subcarinal lymph node cytology were consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate. The tumor cells were positive for AE1/AE3, PSA, and NKX3.1, but were negative for CK7 and TTF-1 (Figure 5). Further imaging revealed an enlarged heterogeneous prostate gland, prominent pelvic nodes, and left retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, as well as sclerotic foci within the T10 vertebral body and right inferior pubic ramus. PSA was also found to be significantly elevated at 700 ng/mL.

Case 3

An 80-year-old male veteran with a history of prostate cancer and recently diagnosed T2N1M0 head and neck squamous cell carcinoma was referred to the Pulmonary service for evaluation of a pulmonary nodule. His medical history was notable for prostate cancer diagnosed 12 years earlier, with an unknown Gleason score. Initial treatment included prostatectomy followed by whole pelvic radiation therapy a year after, due to elevated PSA in surveillance monitoring. This treatment led to remission. After establishing remission for > 10 years, the patient was started on low-dose testosterone replacement therapy to address complications of radiation therapy, namely hypogonadism.

On evaluation, a chest CT was significant for a large 2-cm right middle lobe nodule (Figure 6). At that time, PSA was noted to be borderline elevated at 4.2 ng/mL, and whole-body imaging did not reveal any lesions elsewhere, specifically no bone metastasis. Biopsies of the right middle lobe lung nodule revealed adenocarcinoma consistent with metastatic prostate cancer. Testosterone therapy was promptly discontinued.

The patient initially refused androgen deprivation therapy owing to the antiandrogenic adverse effects. However, subsequent chest CTs revealed growing lung nodules, which convinced him to proceed with androgen deprivation therapy followed by palliative radiation, and chemotherapy and management of malignant pleural effusion with indwelling small bore pleural catheter for about 10 years. He died from COVID-19 during the pandemic.

DISCUSSION

These cases highlight the importance of including prostate cancer in the differential diagnoses of male patients with intrathoracic abnormalities, even in the absence of metastasis to the more common sites. In a large cohort study of 74,826 patients with metastatic prostate cancer, Gandaglia et al found that the most frequent sites of metastasis were bone (84.0%) and distant lymph nodes (10.6%).2 However, thoracic involvement was observed in 9.1% of cases, with isolated thoracic metastasis being rare. The cases described in this report exemplify exceptionally uncommon occurrences within that 9.1%.

Pleural metastases, as observed in Case 1, are a particularly rare manifestation. In a 10-year retrospective assessment, Vinjamoori et al discovered pleural nodules or masses in only 6 of 82 patients (7.3%) with atypical metastases.3 Adrenal and liver metastases accounted for 15% and 37% of cases with atypical distribution. As such, isolated pleural disease is rare even in atypical presentations.3

As seen in Case 2, endobronchial metastases producing airway obstruction are also rare, with the most common primary cancers associated with endobronchial metastasis being breast, colon, and renal cancer.4 The available literature on this presentation is confined to case reports. Hameed et al reported a case of synchronous biopsy-proven endobronchial metastasis from prostate cancer.5 These cases highlight the importance of maintaining a high level of clinical awareness when encountering endobronchial lesions in patients with prostate cancer.

Case 3 presents a unique situation of lung metastases without any involvement of the bones. It is well known—and was confirmed by Heidenreich et al—that lung metastases in prostate adenocarcinoma usually coincide with extensive osseous disease.6 This instance highlights the importance of watchful monitoring for unusual patterns of cancer recurrence.

Immunohistochemistry stains that are specific to prostate cancer include antibodies against PSA. Prostate-specific membrane antigen is another marker that is far more present in malignant than in benign prostate tissue.

The NKX3.1 gene encodes a homeobox protein, which is a transcription factor and tumor suppressor. In prostate cancer, there is loss of heterozygosity of the gene and stains for the IHC antibody to NKX3.1.7

On the other hand, lung cells stain positive for TTF-1, which is produced by surfactant-producing type 2 pneumocytes and club cells in the lung. Antibodies to TTF-1, a common IHC stain, are used to identify adenocarcinoma of lung origin and may carry a prognostic value.7

The immunohistochemistry profiles, specifically the presence of prostate-specific markers such as PSA and NKX3.1, played a vital role in making the diagnosis.

In Case 1, weak TTF-1 positivity was noted, an unusual finding in metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Marak et al documented a rare case of TTF-1–positive metastatic prostate cancer, illustrating the potential for diagnostic confusion with primary lung malignancies.8

The 3 cases described in this report demonstrate the importance of clinical consideration, serial follow-up of PSA levels, using more prostate-specific positron emission tomography tracers (eg, Pylarify) alongside traditional imaging, and tissue biopsy to detect unusual metastases.

CONCLUSIONS

Although thoracic metastases from prostate cancer are rare, these presentations highlight the importance of clinical awareness regarding atypical cases. Pleural disease, endobronchial lesions, and isolated pulmonary nodules might be the first clinical manifestation of metastatic prostate cancer. A high index of suspicion, appropriate imaging, and judicious use of immunohistochemistry are important to ensure accurate diagnosis and optimal patient management.

Prostate cancer is the most common noncutaneous cancer in men, accounting for 29% of all incident cancer cases.1 Typically, prostate cancer metastasizes to bone and regional lymph nodes.2 However, intrathoracic manifestation may occur. This report presents 3 cases of rare intrathoracic manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer with a review of the current literature.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

A 71-year-old male who was an active smoker and a long-standing employment as a plumber was diagnosed with rectal cancer in 2022. He completed neoadjuvant capecitabine and radiation therapy followed by a rectosigmoidectomy. Several weeks after surgery, the patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with a dry cough and worsening shortness of breath. Point-of-care ultrasound of the lungs revealed a moderate right pleural effusion with several nodular pleural masses. A chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed these findings (Figure 1). A CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed prostatomegaly with the medial lobe of the prostate protruding into the bladder; however, no enlarged retroperitoneal, mesenteric or pelvic lymph nodes were noted. The patient underwent a right pleural fluid drainage and pleural mass biopsy. Pleural mass histomorphology as well as immunohistochemical (IHC) stains were consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. The pleural fluid cytology also was consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma.

Immunohistochemistry showed weak positive staining for prostate-specific NK3 homeobox 1 gene (NKX3.1), alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase gene (AMACR), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), keratin-20, and caudal type homeobox 2 gene (CDX2) (Figure 2) 2). The patient's prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was found to be elevated at 33.9 ng/mL (reference range, < 4 ng/mL).

Case 2

A 71-year-old male with a history of alcohol use disorder and a 30-year smoking history presented to the ED with worsening dyspnea on exertion. The patient’s baseline exercise tolerance decreased to walking for only 1 block. He reported unintentional weight loss of about 30 pounds over the prior year, no recent respiratory infections, no prior breathing problems, and no personal or family history of cancer. Chest CT revealed findings of bilateral peribronchial opacities as well as mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy (Figure 3). The patient developed hypoxic respiratory failure necessitating intubation, mechanical ventilation, and management in the medical intensive care unit, where he was treated for postobstructive pneumonia. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed endobronchial lesions in the right and left upper lobe that were partially obstructing the airway (Figure 4).

The endobronchial masses were debulked using forceps, and samples were sent for surgical pathology evaluation. Staging was completed using linear endobronchial ultrasound, which revealed an enlarged subcarinal lymph node (S7). The surgical pathology of the endobronchial mass and the subcarinal lymph node cytology were consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate. The tumor cells were positive for AE1/AE3, PSA, and NKX3.1, but were negative for CK7 and TTF-1 (Figure 5). Further imaging revealed an enlarged heterogeneous prostate gland, prominent pelvic nodes, and left retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, as well as sclerotic foci within the T10 vertebral body and right inferior pubic ramus. PSA was also found to be significantly elevated at 700 ng/mL.

Case 3

An 80-year-old male veteran with a history of prostate cancer and recently diagnosed T2N1M0 head and neck squamous cell carcinoma was referred to the Pulmonary service for evaluation of a pulmonary nodule. His medical history was notable for prostate cancer diagnosed 12 years earlier, with an unknown Gleason score. Initial treatment included prostatectomy followed by whole pelvic radiation therapy a year after, due to elevated PSA in surveillance monitoring. This treatment led to remission. After establishing remission for > 10 years, the patient was started on low-dose testosterone replacement therapy to address complications of radiation therapy, namely hypogonadism.

On evaluation, a chest CT was significant for a large 2-cm right middle lobe nodule (Figure 6). At that time, PSA was noted to be borderline elevated at 4.2 ng/mL, and whole-body imaging did not reveal any lesions elsewhere, specifically no bone metastasis. Biopsies of the right middle lobe lung nodule revealed adenocarcinoma consistent with metastatic prostate cancer. Testosterone therapy was promptly discontinued.

The patient initially refused androgen deprivation therapy owing to the antiandrogenic adverse effects. However, subsequent chest CTs revealed growing lung nodules, which convinced him to proceed with androgen deprivation therapy followed by palliative radiation, and chemotherapy and management of malignant pleural effusion with indwelling small bore pleural catheter for about 10 years. He died from COVID-19 during the pandemic.

DISCUSSION

These cases highlight the importance of including prostate cancer in the differential diagnoses of male patients with intrathoracic abnormalities, even in the absence of metastasis to the more common sites. In a large cohort study of 74,826 patients with metastatic prostate cancer, Gandaglia et al found that the most frequent sites of metastasis were bone (84.0%) and distant lymph nodes (10.6%).2 However, thoracic involvement was observed in 9.1% of cases, with isolated thoracic metastasis being rare. The cases described in this report exemplify exceptionally uncommon occurrences within that 9.1%.

Pleural metastases, as observed in Case 1, are a particularly rare manifestation. In a 10-year retrospective assessment, Vinjamoori et al discovered pleural nodules or masses in only 6 of 82 patients (7.3%) with atypical metastases.3 Adrenal and liver metastases accounted for 15% and 37% of cases with atypical distribution. As such, isolated pleural disease is rare even in atypical presentations.3

As seen in Case 2, endobronchial metastases producing airway obstruction are also rare, with the most common primary cancers associated with endobronchial metastasis being breast, colon, and renal cancer.4 The available literature on this presentation is confined to case reports. Hameed et al reported a case of synchronous biopsy-proven endobronchial metastasis from prostate cancer.5 These cases highlight the importance of maintaining a high level of clinical awareness when encountering endobronchial lesions in patients with prostate cancer.

Case 3 presents a unique situation of lung metastases without any involvement of the bones. It is well known—and was confirmed by Heidenreich et al—that lung metastases in prostate adenocarcinoma usually coincide with extensive osseous disease.6 This instance highlights the importance of watchful monitoring for unusual patterns of cancer recurrence.

Immunohistochemistry stains that are specific to prostate cancer include antibodies against PSA. Prostate-specific membrane antigen is another marker that is far more present in malignant than in benign prostate tissue.

The NKX3.1 gene encodes a homeobox protein, which is a transcription factor and tumor suppressor. In prostate cancer, there is loss of heterozygosity of the gene and stains for the IHC antibody to NKX3.1.7

On the other hand, lung cells stain positive for TTF-1, which is produced by surfactant-producing type 2 pneumocytes and club cells in the lung. Antibodies to TTF-1, a common IHC stain, are used to identify adenocarcinoma of lung origin and may carry a prognostic value.7

The immunohistochemistry profiles, specifically the presence of prostate-specific markers such as PSA and NKX3.1, played a vital role in making the diagnosis.

In Case 1, weak TTF-1 positivity was noted, an unusual finding in metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Marak et al documented a rare case of TTF-1–positive metastatic prostate cancer, illustrating the potential for diagnostic confusion with primary lung malignancies.8

The 3 cases described in this report demonstrate the importance of clinical consideration, serial follow-up of PSA levels, using more prostate-specific positron emission tomography tracers (eg, Pylarify) alongside traditional imaging, and tissue biopsy to detect unusual metastases.

CONCLUSIONS

Although thoracic metastases from prostate cancer are rare, these presentations highlight the importance of clinical awareness regarding atypical cases. Pleural disease, endobronchial lesions, and isolated pulmonary nodules might be the first clinical manifestation of metastatic prostate cancer. A high index of suspicion, appropriate imaging, and judicious use of immunohistochemistry are important to ensure accurate diagnosis and optimal patient management.

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12-49. doi:10.3322/caac.21820

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74(2):210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Vinjamoori AH, Jagannathan JP, Shinagare AB, et al. Atypical metastases from prostate cancer: 10-year experience at a single institution. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(2):367-372. doi:10.2214/AJR.11.7533

- Salud A, Porcel JM, Rovirosa A, Bellmunt J. Endobronchial metastatic disease: analysis of 32 cases. J Surg Oncol. 1996;62(4):249-252. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096- 9098(199608)62:4<249::AID-JSO4>3.0.CO;2-6

- Hameed M, Haq IU, Yousaf M, Hussein M, Rashid U, Al-Bozom I. Endobronchial metastases secondary to prostate cancer: a case report and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020;32:101326. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101326

- Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al; for the European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration- resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65(2):467- 479. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.002

- Schallenberg S, Dernbach G, Dragomir MP, et al. TTF-1 status in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma is an independent predictor of relapse and survival superior to tumor grading. Eur J Cancer. 2024;197:113474. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113474

- Marak C, Guddati AK, Ashraf A, Smith J, Kaushik P. Prostate adenocarcinoma with atypical immunohistochemistry presenting with a Cheerio sign. AIM Clinical Cases. 2023;1:e220508. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0508

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12-49. doi:10.3322/caac.21820

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74(2):210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Vinjamoori AH, Jagannathan JP, Shinagare AB, et al. Atypical metastases from prostate cancer: 10-year experience at a single institution. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(2):367-372. doi:10.2214/AJR.11.7533

- Salud A, Porcel JM, Rovirosa A, Bellmunt J. Endobronchial metastatic disease: analysis of 32 cases. J Surg Oncol. 1996;62(4):249-252. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096- 9098(199608)62:4<249::AID-JSO4>3.0.CO;2-6

- Hameed M, Haq IU, Yousaf M, Hussein M, Rashid U, Al-Bozom I. Endobronchial metastases secondary to prostate cancer: a case report and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020;32:101326. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101326

- Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al; for the European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration- resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65(2):467- 479. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.002

- Schallenberg S, Dernbach G, Dragomir MP, et al. TTF-1 status in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma is an independent predictor of relapse and survival superior to tumor grading. Eur J Cancer. 2024;197:113474. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113474

- Marak C, Guddati AK, Ashraf A, Smith J, Kaushik P. Prostate adenocarcinoma with atypical immunohistochemistry presenting with a Cheerio sign. AIM Clinical Cases. 2023;1:e220508. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0508

Atypical Intrathoracic Manifestations of Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Case Series

Atypical Intrathoracic Manifestations of Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Case Series

The Need for a Multidisciplinary Approach for Successful High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism Treatment

The Need for a Multidisciplinary Approach for Successful High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism Treatment

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in the general population.1 The incidence of PE has been reported to range from 39 to 115 per 100,000 persons per year and has remained stable.2 Although mortality rates have declined, they remain high.3 The clinical presentation is nonspecific, making diagnosis and management challenging. A crucial and difficult aspect in the management of patients with PE is weighing the risks vs benefits of treatment, including thrombolytic therapy and other invasive procedures, which carry inherent risks. These factors have led to the development of PE response teams (PERTs) in some hospitals to implement effective multidisciplinary protocols that facilitate prompt diagnosis, management, and follow-up.4

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

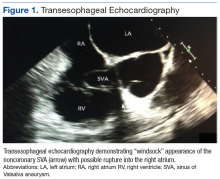

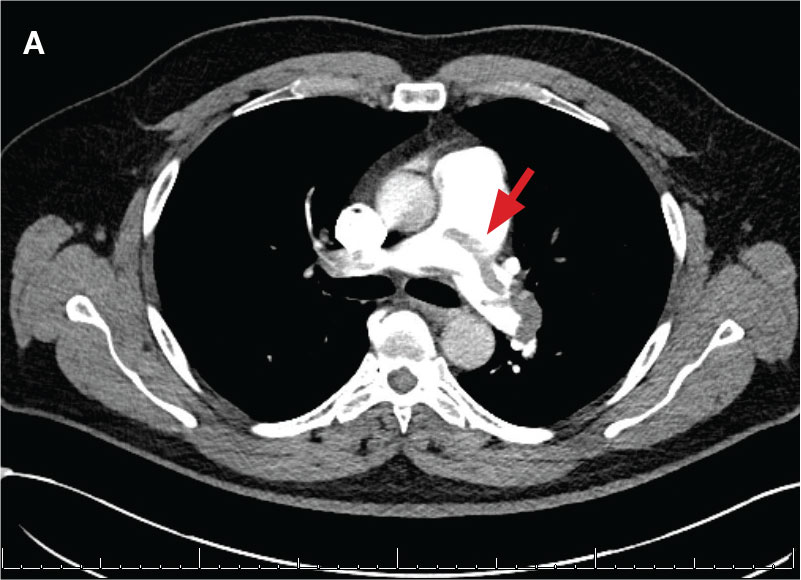

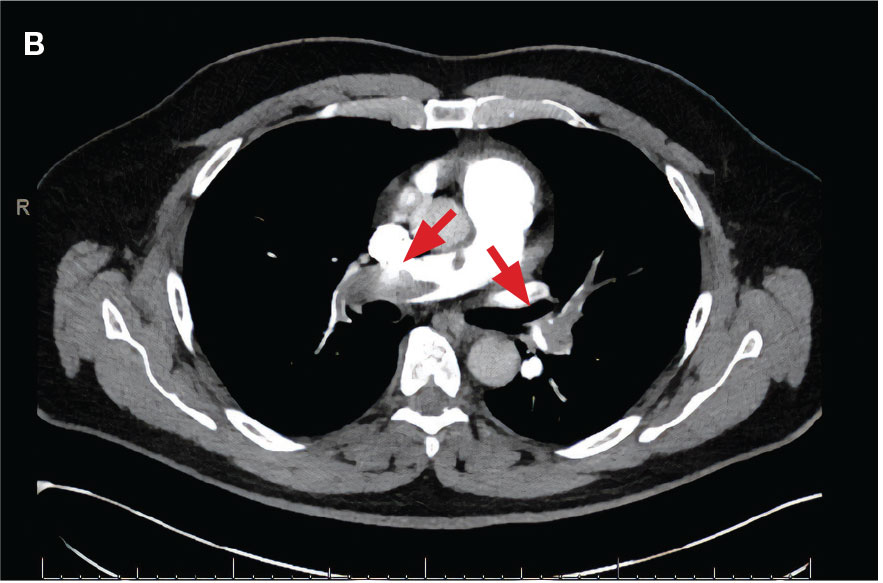

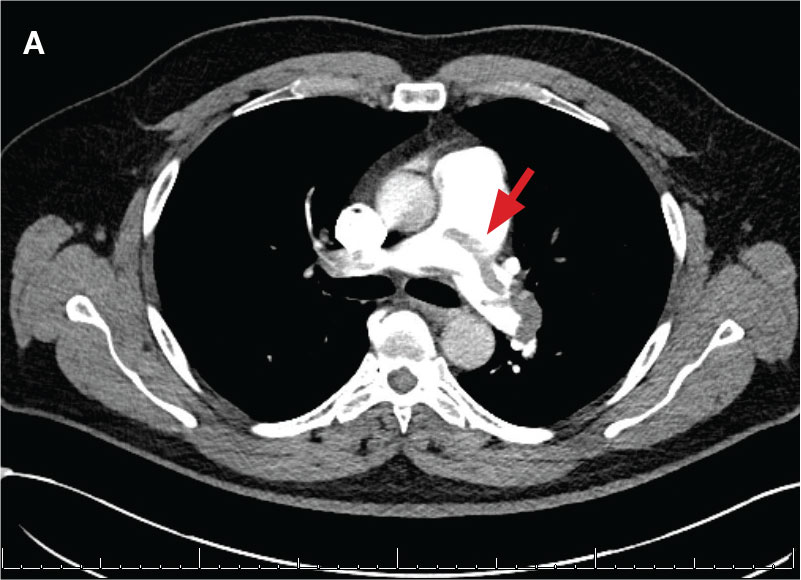

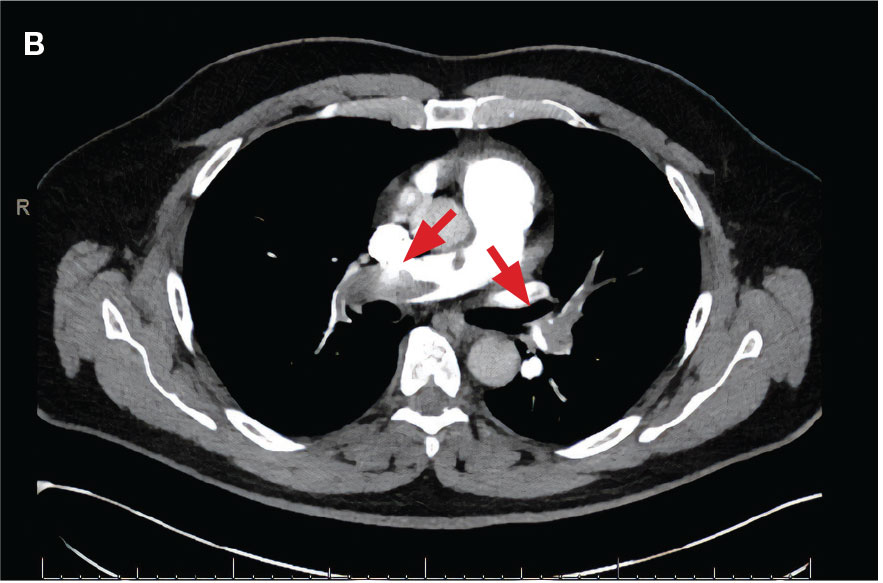

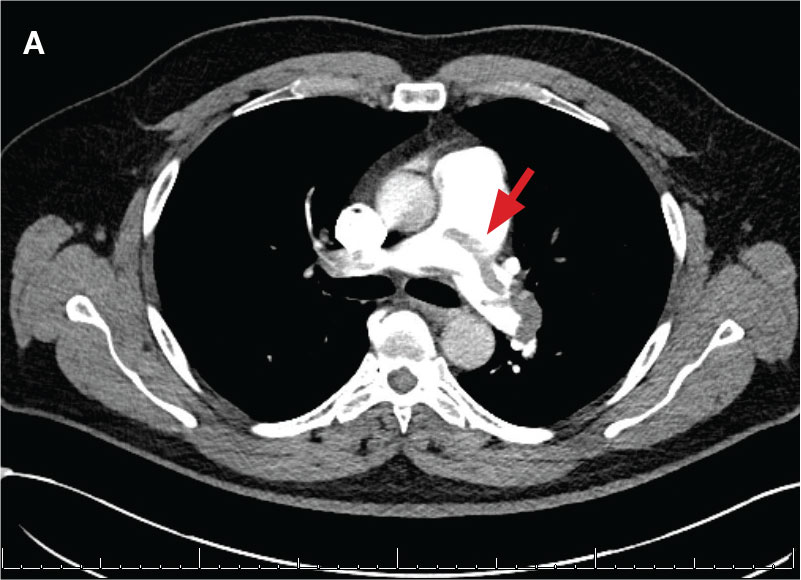

New onset seizures and cardiac arrest in the treatment of saddle PE. A 54-year-old male who worked as a draftsman and truck driver with a history of hypertension and nephrolithiasis presented to the emergency department (ED) with progressive shortness of breath for 2 weeks. On the morning of ED presentation the patient experienced an episode of severe shortness of breath, lightheadedness, and chest pressure. He reported no other symptoms such as palpitations, nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, or extremity pain or swelling. He reported no recent travel, immunization, falls, or surgery. Upon evaluation, the patient was found to be in no acute distress, with stable vital signs and laboratory results except for 2 elevated results: > 20 μg/mL D-dimer (reference range, < 0.5 μg/mL) and N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (proBNP) level, 3455 pg/mL (reference range, < 125 pg/mL for patients aged < 75 years). Electrocardiogram showed T-wave inversions in leads V2 to V4. Imaging revealed a saddle PE and left popliteal deep venous thrombosis (Figure 1). The patient received an anticoagulation loading dose and was started on heparin drip upon admission to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) for further management and monitoring. The Interventional Radiology Service recommended full anticoagulation with consideration of reperfusion therapies if deterioration developed.

indicated by arrows in the pulmonary trunk extending to the left pulmonary artery (A),

and obliterating right pulmonary artery and branches of left pulmonary artery (B).

indicated by arrows in the pulmonary trunk extending to the left pulmonary artery (A),

and obliterating right pulmonary artery and branches of left pulmonary artery (B).

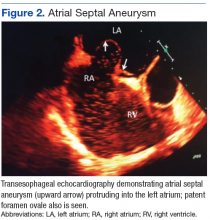

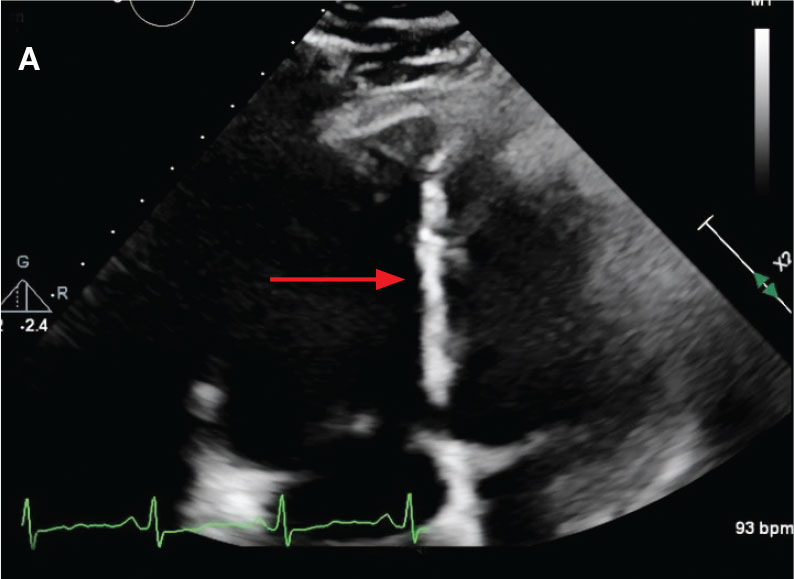

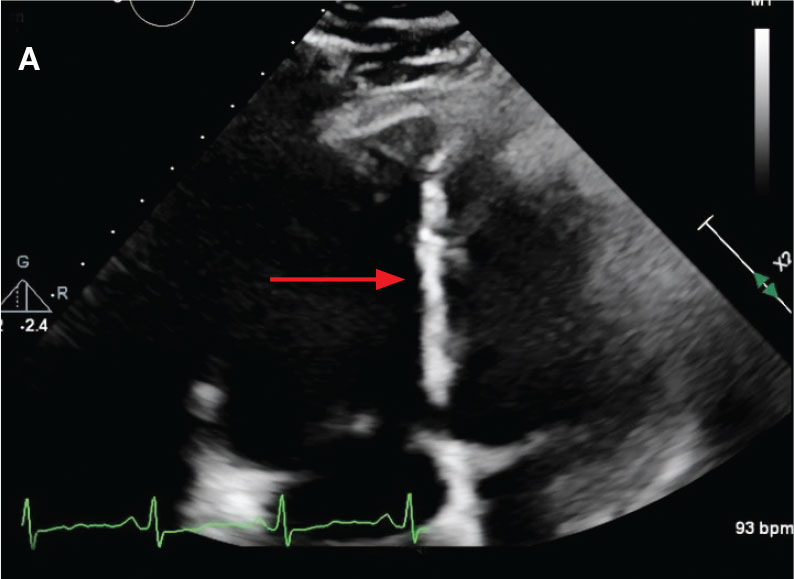

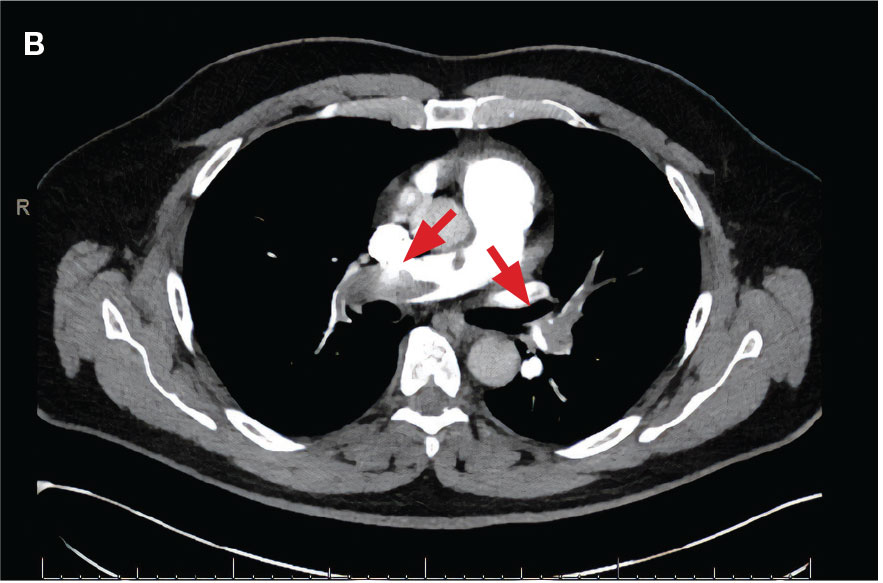

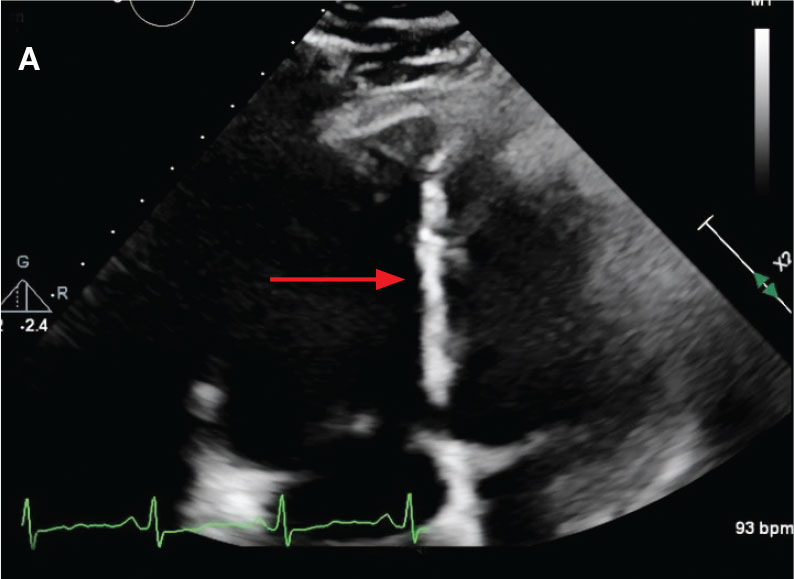

While in the MICU, point-of-care ultrasound findings were confirmed with official echocardiogram by the cardiology service, which demonstrated a preserved ejection fraction of 60% to 65%, a D-shaped left ventricle with septal wall hypokinesis secondary to right heart strain (Figure 2), a markedly elevated right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) of 73 mm Hg, and a mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) of 38 mm Hg. The patient’s blood pressure progressively decreased, heart rate increased, and he required increased oxygen supplementation. The case was discussed with the Pharmacy Service, and since the patient had no contraindications to thrombolytic therapy, the appropriate dosage was calculated and 100 mg intravenous (IV) tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was administered over 2 hours.

flattening and deviation to left in direction (A) and septal deviation to left with

formation of D-sign (B).

flattening and deviation to left in direction (A) and septal deviation to left with

formation of D-sign (B).

About 40 minutes into tPA infusion, the patient suddenly experienced marked shortness of breath, diaphoresis, and anxiety with seizure-like involuntary movements; as a result, the infusion was stopped. He also had episodes of posturing, mental status decline, and briefly going in and out of consciousness, which lasted about 3 minutes before he lost consciousness and pulse. High-quality advanced cardiac life support was initiated, followed by endotracheal intubation. Despite a secured airway and return of spontaneous circulation, the patient remained hypotensive and continued to have seizure-like activity.

The patient was administered a total of 8 mg of lorazepam, sedated with propofol, initiated at 5 μg/kg/min, titrated to stop seizure activity at 15μg/kg/min, and later maintained at 10 μg/kg/min, for a RASS of -1, and started on norepinephrine 0.1 μg/kg/min for acute stabilization. Head computed tomography without contrast showed no acute intracranial pathology as etiology of seizures. Seizure etiology differential at this time was broad; however, hypoxemia due to PE and medication adverse effects were strongly suspected.

The patient’s condition improved, and vasopressor therapy was tapered off the next day. Four days later, the patient was weaned from mechanical ventilation and transferred to the step-down unit. Echocardiogram obtained 48 hours after tPA infusion showed essentially normal left ventricular function (60%-65%), a RVSP of 17 mm Hg and mPAP of 13 mm Hg. The patient’s ProBNP levels markedly decreased to 137 pg/mL. Postextubation, the neurologic examination was at baseline. The Neurology Service recommended temporary treatment with levetiracetam, 1000 mg every 12 hours, and the Hematology Service recommended transitioning to direct oral anticoagulation with follow-up. The patient presented significant clinical and respiratory improvement and was referred for home-based physical rehabilitation as recommended by the physical medicine and rehabilitation service before being discharged.

Case 2

Localized tPA infusion for bilateral PEs via infusion catheters. A 91-year-old male with no history of smoking and a medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, prostate cancer (> 20 years postradiotherapy) and severe osteoarthritis was receiving treatment in the medical ward for medication-induced liver injury secondary to an antibiotic for a urinary tract infection. During the night the patient developed hypotension (86/46 mm Hg), shortness of breath, tachypnea, desaturation, nonradiating retrosternal chest pain, and tachycardia. The hypotension resolved after a 500-mL 0.9 normal saline bolus, and hypoxemia improved with supplemental oxygen via Venturi mask. Chest computed tomography angiography was performed immediately and revealed extensive bilateral acute PE, located most proximally in the right main pulmonary artery (PA) and on the left in the proximal lobar branches, with associated right heart strain. The patient was started on IV heparin with a bolus of 5000 units (80 u/kg) followed by a drip with a partial thromboplastin time goal of 62-103 seconds and transferred to MICU.

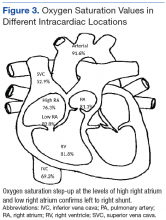

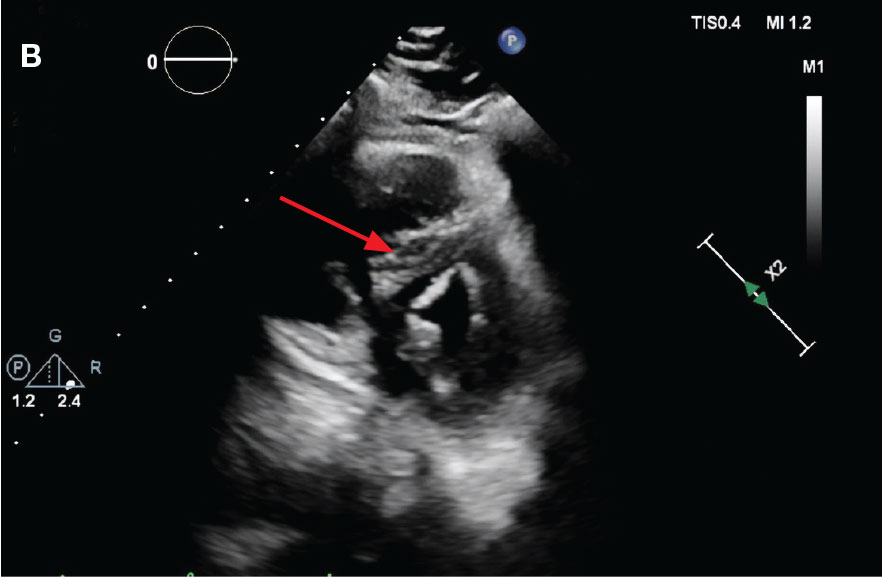

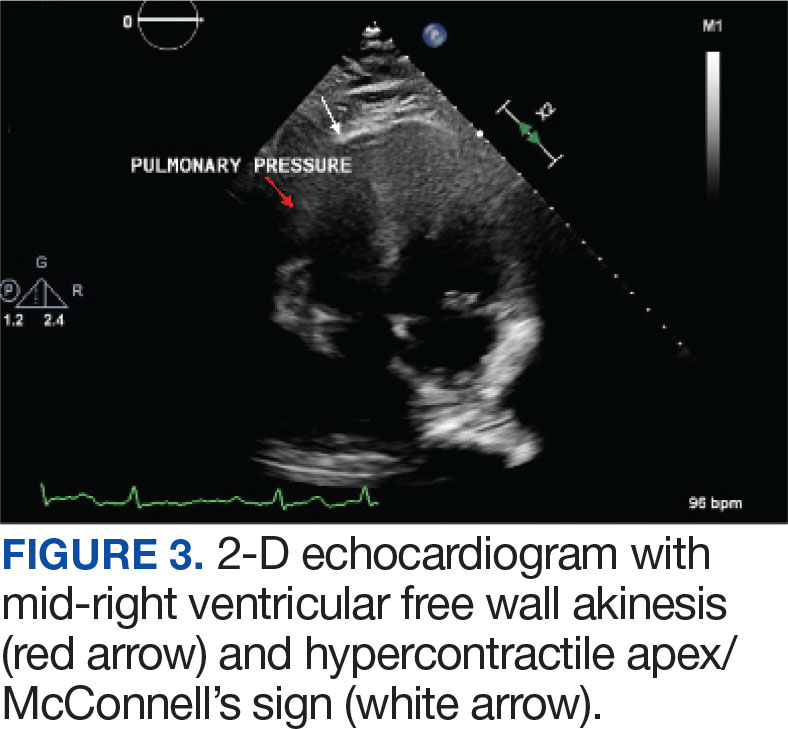

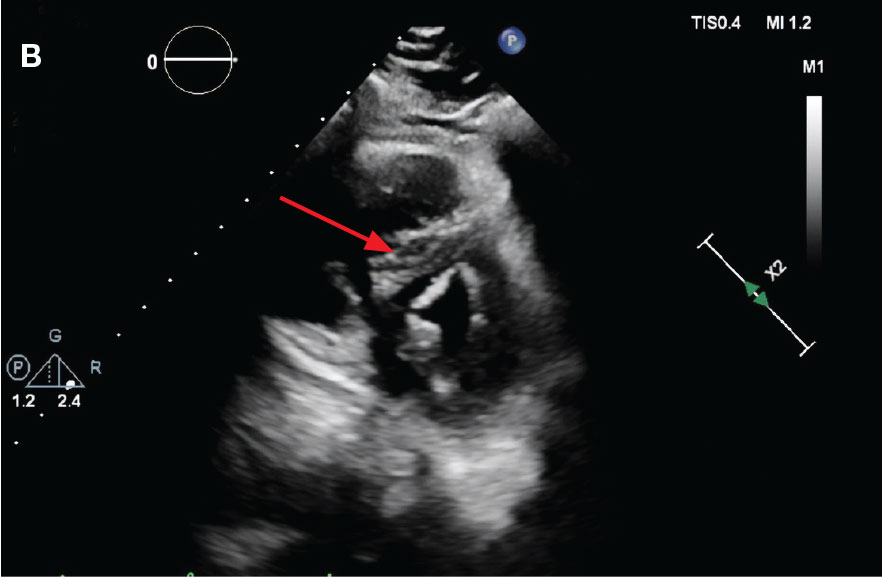

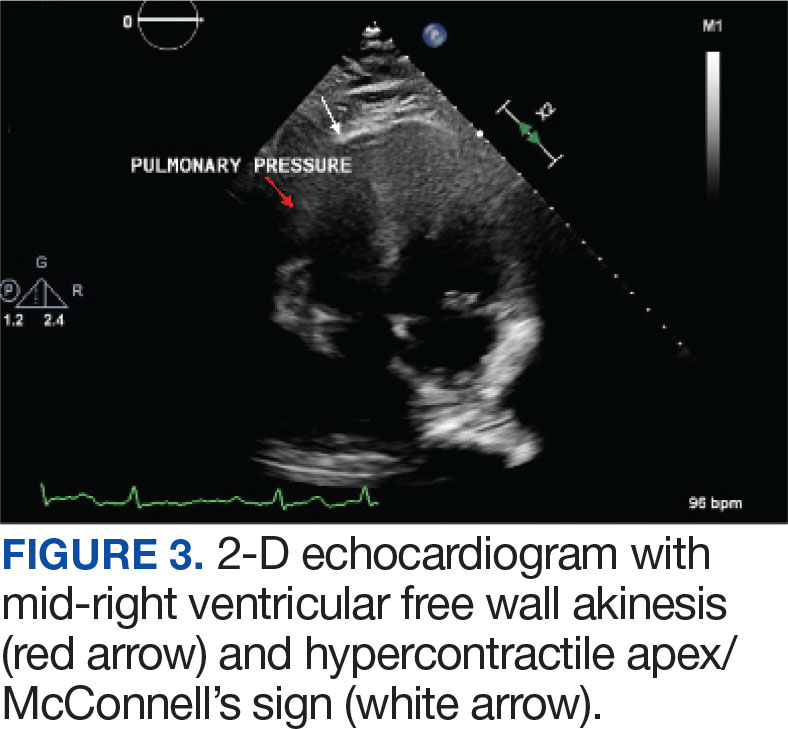

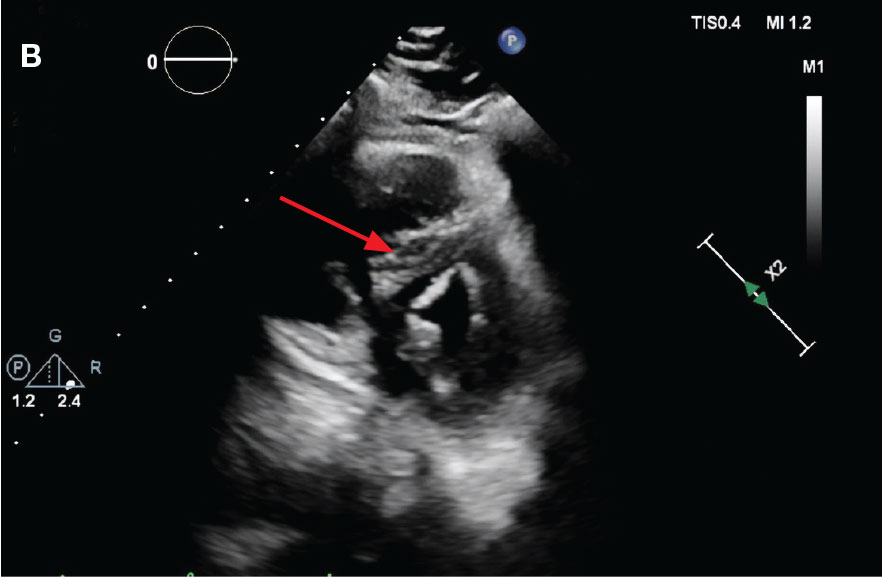

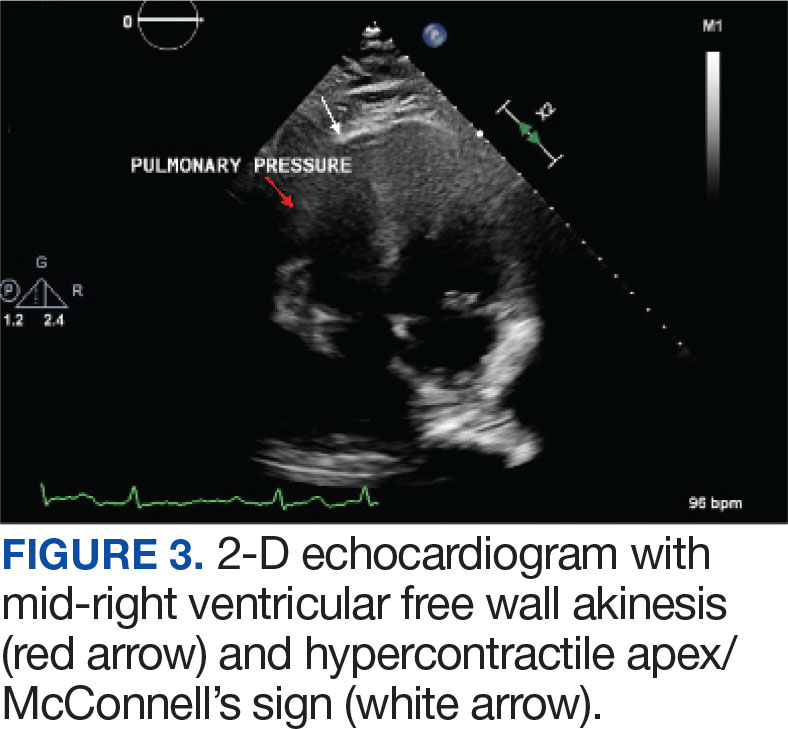

Laboratory findings were notable for proBNP that increased from 115 pg/mL to 4470 pg/mL (reference range, < 450 pg/mL for patients aged 75 years) and elevated troponin levels at 218 ng/L to 295 ng/L (reference range, < 22 ng/L), exhibiting chemical evidence of right heart strain. Initial echocardiogram showed mid-right ventricular free wall akinesis with a hypercontractile apex, suggestive of PE (McConnell’s sign) (Figure 3). Interventional Radiology Service was consulted and recommended tPA infusion given that the patient had bilateral PEs and stable blood pressure.

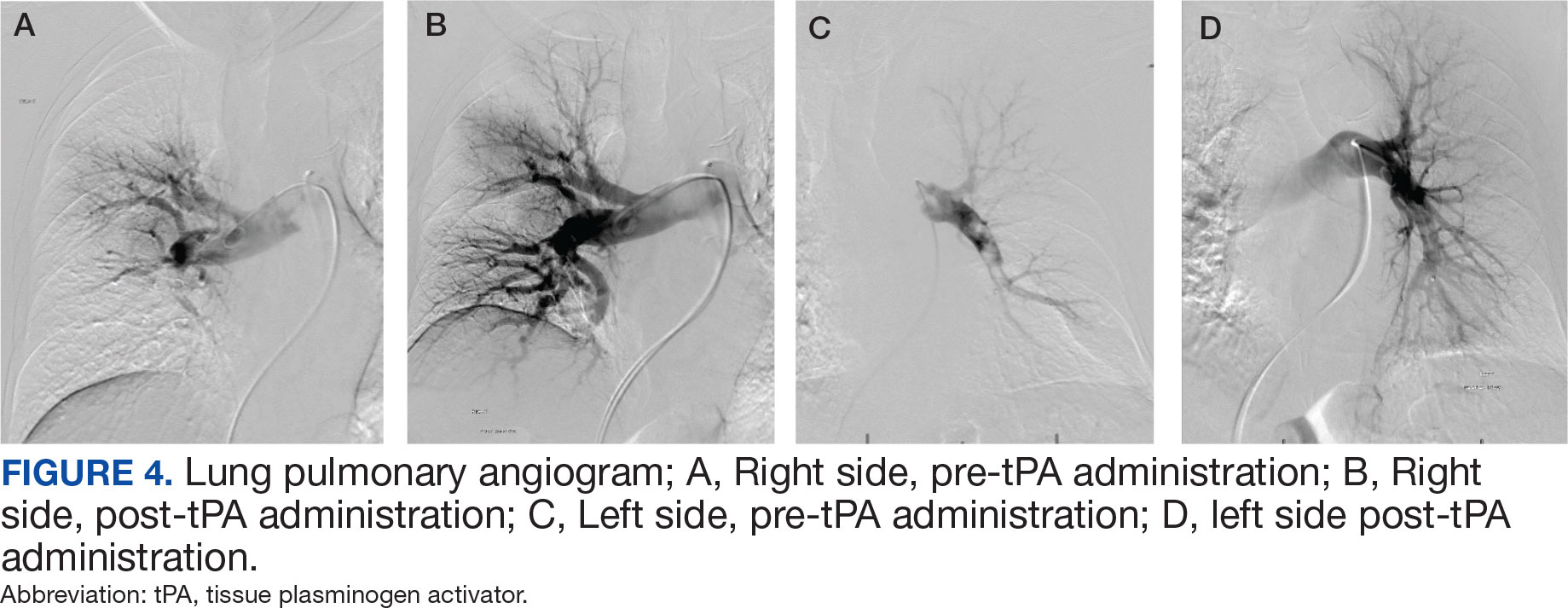

Pulmonary angiogram showed elevated pressures in the right PA of 64/21 mm Hg and the left PA pressures of 63/20 mm Hg. Mechanical disruption of the larger right lower PA thrombus was achieved via a pigtail catheter followed by bilateral catheter bolus infusions of 2 mg tPA (alteplase) and a continuous tPA infusion 0.5 mg/h for 24 hours, in conjunction with a heparin infusion.

After 24 hours of tPA infusion, the catheters were removed, with posttreatment pulmonary angiography demonstrating right and left PA pressures of 42/15 mm Hg and 40/16 mm Hg, respectively. Pre- and postlocalized tPA infusion treatment images are provided for visual comparison (Figure 4). An echocardiogram performed after tPA infusion showed no signs of pulmonary hypertension. The Hematology Service provided recommendations regarding anticoagulation, and after completion of tPA infusion, the patient was transitioned to an unfractioned heparin infusion and subsequently to direct oral anticoagulation prior to transfer back to the medical ward, hemodynamically stable and asymptomatic.

DISCUSSION

PE management can be a straightforward decision when the patient meets criteria for hemodynamic instability, or with small PE burden. In contrast, management can be more challenging in intermediate-risk (submassive) PE when patients remain hemodynamically stable but show signs of cardiopulmonary stress, such as right heart strain, elevated troponins, or increased proBNP levels.2 In these situations, case-by- case evaluation is warranted. A PERT can assess the most beneficial treatment approach by considering factors such as right ventricular dysfunction, hemodynamic status, clot burden, and clinical deterioration despite appropriate anticoagulation. The evidence supporting the benefits these organized teams can provide is growing. These case reports emphasize the need for a multidisciplinary and systematic approach in these complex cases, especially in the management of intermediate-risk PE patients.

Currently, the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System does not have an organized PERT, although a multidisciplinary approach was applied in the management of these patients. A systematic, structured team could have decreased time to interventions and alleviated the burden of physician decision-making. Having such a team would streamline the diagnostic pathway for patients presenting from a ward or emergency department with suspected PE.

We present 2 cases of patients found to have a high clot burden from PEs. The patients were initially hemodynamically stable (intermediate-risk PE), but later required systemic or localized thrombolysis due to hemodynamic deterioration despite adequate anticoagulation. Despite similar diagnoses and etiologies, these patients were successfully managed using different approaches, yielding positive outcomes. This reflects the complexity and variability in diagnosing and managing intermediate-risk PE in patients with different comorbidities and clot burden effects. In Case 1, our multidisciplinary approach was obtained via consults to selected services such as interventional radiology, cardiology, and direct involvement of pharmacy. An organized PERT conceivably would have allowed quicker discussions among these services, including hematology, to provide recommendations and collaborative support upon the patient’s arrival to the ED. Additionally, with a PERT team, a systematic approach to these patients could have allowed for an earlier official echocardiogram report for evaluation of right heart strain and develop an adequate therapeutic plan in a timely manner.

In Case 2, consultation with the Interventional Radiology Service yielded a better therapeutic plan, utilizing localized tPA infusion for this older adult patient with increased risk of bleeding with systemic tPA infusion. Having a PERT presents an opportunity to optimize PE management through early recognition, diagnosis, and treatment by institutional consensus from an interdisciplinary team.5,6 These response teams may improve outcomes and prognosis for patients with PE, especially where diagnosis and management is not clear.

The definite etiology of seizure activity in the first case pre- and postcardiac arrest, in the context of no acute intracranial process, remains unknown. Reports have emerged about postreperfusion seizures in acute ischemic stroke, as well as cases of seizures masquerading as PE as the primary presentation. 7,8 However, there were no reports of patients developing seizures post tPA infusion for the treatment of PE. This report may shed light into possible complications secondary to tPA infusion, raising awareness among physicians and encouraging further investigation into its possible etiologies.

CONCLUSIONS

Management of PE can be challenging in patients that meet criteria for intermediate risk. PERTs are a tool that allow for a multidisciplinary, standardized and systematic approach with a diagnostic and treatment algorithm that conceivably would result in a better consensus and therapeutic approach.

- Thompson BT, Kabrhel C. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of acute pulmonary embolism in adults. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Updated December 4, 2023. Accessed February 26, 2025. https://www.uptodate.cn/contents/epidemiology-and-pathogenesis-of-acute-pulmonary-embolism-in-adults

- Kulka HC, Zeller A, Fornaro J, Wuillemin WA, Konstantinides S, Christ M. Acute pulmonary embolism– its diagnosis and treatment from a multidisciplinary viewpoint. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118(37):618-628. doi:10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0226

- Zghouzi M, Mwansa H, Shore S, et al. Sex, racial, and geographic disparities in pulmonary embolism-related mortality nationwide. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023;20(11):1571-1577. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202302-091OC

- Channick RN. The pulmonary embolism response team: why and how? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;42(2):212-217. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1722963

- Rosovsky R, Zhao K, Sista A, Rivera-Lebron B, Kabrhel C. Pulmonary embolism response teams: purpose, evidence for efficacy, and future research directions. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2019;3(3):315-330. doi:10.1002/rth2.12216

- Glazier JJ, Patiño-Velasquez S, Oviedo C. The pulmonary embolism response team: rationale, operation, and outcomes. Int J Angiol. 2022;31(3):198-202. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1750328

- Lekoubou A, Fox J, Ssentongo P. Incidence and association of reperfusion therapies with poststroke seizures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2020;51(9):2715-2723.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.119. 028899

- Alemany M, Nuñez A, Falip M, et al. Acute symptomatic seizures and epilepsy after mechanical thrombectomy. A prospective long-term follow-up study. Seizure. 2021;89:5-9. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2021.04.011

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in the general population.1 The incidence of PE has been reported to range from 39 to 115 per 100,000 persons per year and has remained stable.2 Although mortality rates have declined, they remain high.3 The clinical presentation is nonspecific, making diagnosis and management challenging. A crucial and difficult aspect in the management of patients with PE is weighing the risks vs benefits of treatment, including thrombolytic therapy and other invasive procedures, which carry inherent risks. These factors have led to the development of PE response teams (PERTs) in some hospitals to implement effective multidisciplinary protocols that facilitate prompt diagnosis, management, and follow-up.4

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

New onset seizures and cardiac arrest in the treatment of saddle PE. A 54-year-old male who worked as a draftsman and truck driver with a history of hypertension and nephrolithiasis presented to the emergency department (ED) with progressive shortness of breath for 2 weeks. On the morning of ED presentation the patient experienced an episode of severe shortness of breath, lightheadedness, and chest pressure. He reported no other symptoms such as palpitations, nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, or extremity pain or swelling. He reported no recent travel, immunization, falls, or surgery. Upon evaluation, the patient was found to be in no acute distress, with stable vital signs and laboratory results except for 2 elevated results: > 20 μg/mL D-dimer (reference range, < 0.5 μg/mL) and N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (proBNP) level, 3455 pg/mL (reference range, < 125 pg/mL for patients aged < 75 years). Electrocardiogram showed T-wave inversions in leads V2 to V4. Imaging revealed a saddle PE and left popliteal deep venous thrombosis (Figure 1). The patient received an anticoagulation loading dose and was started on heparin drip upon admission to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) for further management and monitoring. The Interventional Radiology Service recommended full anticoagulation with consideration of reperfusion therapies if deterioration developed.

indicated by arrows in the pulmonary trunk extending to the left pulmonary artery (A),

and obliterating right pulmonary artery and branches of left pulmonary artery (B).

indicated by arrows in the pulmonary trunk extending to the left pulmonary artery (A),

and obliterating right pulmonary artery and branches of left pulmonary artery (B).

While in the MICU, point-of-care ultrasound findings were confirmed with official echocardiogram by the cardiology service, which demonstrated a preserved ejection fraction of 60% to 65%, a D-shaped left ventricle with septal wall hypokinesis secondary to right heart strain (Figure 2), a markedly elevated right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) of 73 mm Hg, and a mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) of 38 mm Hg. The patient’s blood pressure progressively decreased, heart rate increased, and he required increased oxygen supplementation. The case was discussed with the Pharmacy Service, and since the patient had no contraindications to thrombolytic therapy, the appropriate dosage was calculated and 100 mg intravenous (IV) tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was administered over 2 hours.

flattening and deviation to left in direction (A) and septal deviation to left with

formation of D-sign (B).

flattening and deviation to left in direction (A) and septal deviation to left with

formation of D-sign (B).

About 40 minutes into tPA infusion, the patient suddenly experienced marked shortness of breath, diaphoresis, and anxiety with seizure-like involuntary movements; as a result, the infusion was stopped. He also had episodes of posturing, mental status decline, and briefly going in and out of consciousness, which lasted about 3 minutes before he lost consciousness and pulse. High-quality advanced cardiac life support was initiated, followed by endotracheal intubation. Despite a secured airway and return of spontaneous circulation, the patient remained hypotensive and continued to have seizure-like activity.

The patient was administered a total of 8 mg of lorazepam, sedated with propofol, initiated at 5 μg/kg/min, titrated to stop seizure activity at 15μg/kg/min, and later maintained at 10 μg/kg/min, for a RASS of -1, and started on norepinephrine 0.1 μg/kg/min for acute stabilization. Head computed tomography without contrast showed no acute intracranial pathology as etiology of seizures. Seizure etiology differential at this time was broad; however, hypoxemia due to PE and medication adverse effects were strongly suspected.

The patient’s condition improved, and vasopressor therapy was tapered off the next day. Four days later, the patient was weaned from mechanical ventilation and transferred to the step-down unit. Echocardiogram obtained 48 hours after tPA infusion showed essentially normal left ventricular function (60%-65%), a RVSP of 17 mm Hg and mPAP of 13 mm Hg. The patient’s ProBNP levels markedly decreased to 137 pg/mL. Postextubation, the neurologic examination was at baseline. The Neurology Service recommended temporary treatment with levetiracetam, 1000 mg every 12 hours, and the Hematology Service recommended transitioning to direct oral anticoagulation with follow-up. The patient presented significant clinical and respiratory improvement and was referred for home-based physical rehabilitation as recommended by the physical medicine and rehabilitation service before being discharged.

Case 2

Localized tPA infusion for bilateral PEs via infusion catheters. A 91-year-old male with no history of smoking and a medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, prostate cancer (> 20 years postradiotherapy) and severe osteoarthritis was receiving treatment in the medical ward for medication-induced liver injury secondary to an antibiotic for a urinary tract infection. During the night the patient developed hypotension (86/46 mm Hg), shortness of breath, tachypnea, desaturation, nonradiating retrosternal chest pain, and tachycardia. The hypotension resolved after a 500-mL 0.9 normal saline bolus, and hypoxemia improved with supplemental oxygen via Venturi mask. Chest computed tomography angiography was performed immediately and revealed extensive bilateral acute PE, located most proximally in the right main pulmonary artery (PA) and on the left in the proximal lobar branches, with associated right heart strain. The patient was started on IV heparin with a bolus of 5000 units (80 u/kg) followed by a drip with a partial thromboplastin time goal of 62-103 seconds and transferred to MICU.

Laboratory findings were notable for proBNP that increased from 115 pg/mL to 4470 pg/mL (reference range, < 450 pg/mL for patients aged 75 years) and elevated troponin levels at 218 ng/L to 295 ng/L (reference range, < 22 ng/L), exhibiting chemical evidence of right heart strain. Initial echocardiogram showed mid-right ventricular free wall akinesis with a hypercontractile apex, suggestive of PE (McConnell’s sign) (Figure 3). Interventional Radiology Service was consulted and recommended tPA infusion given that the patient had bilateral PEs and stable blood pressure.

Pulmonary angiogram showed elevated pressures in the right PA of 64/21 mm Hg and the left PA pressures of 63/20 mm Hg. Mechanical disruption of the larger right lower PA thrombus was achieved via a pigtail catheter followed by bilateral catheter bolus infusions of 2 mg tPA (alteplase) and a continuous tPA infusion 0.5 mg/h for 24 hours, in conjunction with a heparin infusion.

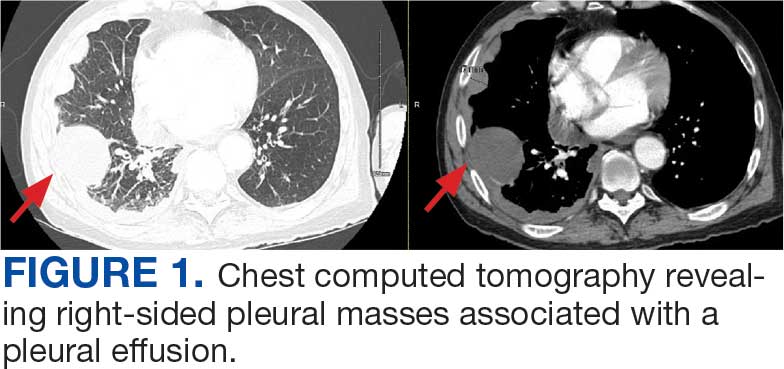

After 24 hours of tPA infusion, the catheters were removed, with posttreatment pulmonary angiography demonstrating right and left PA pressures of 42/15 mm Hg and 40/16 mm Hg, respectively. Pre- and postlocalized tPA infusion treatment images are provided for visual comparison (Figure 4). An echocardiogram performed after tPA infusion showed no signs of pulmonary hypertension. The Hematology Service provided recommendations regarding anticoagulation, and after completion of tPA infusion, the patient was transitioned to an unfractioned heparin infusion and subsequently to direct oral anticoagulation prior to transfer back to the medical ward, hemodynamically stable and asymptomatic.

DISCUSSION

PE management can be a straightforward decision when the patient meets criteria for hemodynamic instability, or with small PE burden. In contrast, management can be more challenging in intermediate-risk (submassive) PE when patients remain hemodynamically stable but show signs of cardiopulmonary stress, such as right heart strain, elevated troponins, or increased proBNP levels.2 In these situations, case-by- case evaluation is warranted. A PERT can assess the most beneficial treatment approach by considering factors such as right ventricular dysfunction, hemodynamic status, clot burden, and clinical deterioration despite appropriate anticoagulation. The evidence supporting the benefits these organized teams can provide is growing. These case reports emphasize the need for a multidisciplinary and systematic approach in these complex cases, especially in the management of intermediate-risk PE patients.

Currently, the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System does not have an organized PERT, although a multidisciplinary approach was applied in the management of these patients. A systematic, structured team could have decreased time to interventions and alleviated the burden of physician decision-making. Having such a team would streamline the diagnostic pathway for patients presenting from a ward or emergency department with suspected PE.

We present 2 cases of patients found to have a high clot burden from PEs. The patients were initially hemodynamically stable (intermediate-risk PE), but later required systemic or localized thrombolysis due to hemodynamic deterioration despite adequate anticoagulation. Despite similar diagnoses and etiologies, these patients were successfully managed using different approaches, yielding positive outcomes. This reflects the complexity and variability in diagnosing and managing intermediate-risk PE in patients with different comorbidities and clot burden effects. In Case 1, our multidisciplinary approach was obtained via consults to selected services such as interventional radiology, cardiology, and direct involvement of pharmacy. An organized PERT conceivably would have allowed quicker discussions among these services, including hematology, to provide recommendations and collaborative support upon the patient’s arrival to the ED. Additionally, with a PERT team, a systematic approach to these patients could have allowed for an earlier official echocardiogram report for evaluation of right heart strain and develop an adequate therapeutic plan in a timely manner.

In Case 2, consultation with the Interventional Radiology Service yielded a better therapeutic plan, utilizing localized tPA infusion for this older adult patient with increased risk of bleeding with systemic tPA infusion. Having a PERT presents an opportunity to optimize PE management through early recognition, diagnosis, and treatment by institutional consensus from an interdisciplinary team.5,6 These response teams may improve outcomes and prognosis for patients with PE, especially where diagnosis and management is not clear.

The definite etiology of seizure activity in the first case pre- and postcardiac arrest, in the context of no acute intracranial process, remains unknown. Reports have emerged about postreperfusion seizures in acute ischemic stroke, as well as cases of seizures masquerading as PE as the primary presentation. 7,8 However, there were no reports of patients developing seizures post tPA infusion for the treatment of PE. This report may shed light into possible complications secondary to tPA infusion, raising awareness among physicians and encouraging further investigation into its possible etiologies.

CONCLUSIONS

Management of PE can be challenging in patients that meet criteria for intermediate risk. PERTs are a tool that allow for a multidisciplinary, standardized and systematic approach with a diagnostic and treatment algorithm that conceivably would result in a better consensus and therapeutic approach.

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in the general population.1 The incidence of PE has been reported to range from 39 to 115 per 100,000 persons per year and has remained stable.2 Although mortality rates have declined, they remain high.3 The clinical presentation is nonspecific, making diagnosis and management challenging. A crucial and difficult aspect in the management of patients with PE is weighing the risks vs benefits of treatment, including thrombolytic therapy and other invasive procedures, which carry inherent risks. These factors have led to the development of PE response teams (PERTs) in some hospitals to implement effective multidisciplinary protocols that facilitate prompt diagnosis, management, and follow-up.4

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

New onset seizures and cardiac arrest in the treatment of saddle PE. A 54-year-old male who worked as a draftsman and truck driver with a history of hypertension and nephrolithiasis presented to the emergency department (ED) with progressive shortness of breath for 2 weeks. On the morning of ED presentation the patient experienced an episode of severe shortness of breath, lightheadedness, and chest pressure. He reported no other symptoms such as palpitations, nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, or extremity pain or swelling. He reported no recent travel, immunization, falls, or surgery. Upon evaluation, the patient was found to be in no acute distress, with stable vital signs and laboratory results except for 2 elevated results: > 20 μg/mL D-dimer (reference range, < 0.5 μg/mL) and N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (proBNP) level, 3455 pg/mL (reference range, < 125 pg/mL for patients aged < 75 years). Electrocardiogram showed T-wave inversions in leads V2 to V4. Imaging revealed a saddle PE and left popliteal deep venous thrombosis (Figure 1). The patient received an anticoagulation loading dose and was started on heparin drip upon admission to the medical intensive care unit (MICU) for further management and monitoring. The Interventional Radiology Service recommended full anticoagulation with consideration of reperfusion therapies if deterioration developed.

indicated by arrows in the pulmonary trunk extending to the left pulmonary artery (A),

and obliterating right pulmonary artery and branches of left pulmonary artery (B).

indicated by arrows in the pulmonary trunk extending to the left pulmonary artery (A),

and obliterating right pulmonary artery and branches of left pulmonary artery (B).

While in the MICU, point-of-care ultrasound findings were confirmed with official echocardiogram by the cardiology service, which demonstrated a preserved ejection fraction of 60% to 65%, a D-shaped left ventricle with septal wall hypokinesis secondary to right heart strain (Figure 2), a markedly elevated right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) of 73 mm Hg, and a mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) of 38 mm Hg. The patient’s blood pressure progressively decreased, heart rate increased, and he required increased oxygen supplementation. The case was discussed with the Pharmacy Service, and since the patient had no contraindications to thrombolytic therapy, the appropriate dosage was calculated and 100 mg intravenous (IV) tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was administered over 2 hours.

flattening and deviation to left in direction (A) and septal deviation to left with

formation of D-sign (B).

flattening and deviation to left in direction (A) and septal deviation to left with

formation of D-sign (B).

About 40 minutes into tPA infusion, the patient suddenly experienced marked shortness of breath, diaphoresis, and anxiety with seizure-like involuntary movements; as a result, the infusion was stopped. He also had episodes of posturing, mental status decline, and briefly going in and out of consciousness, which lasted about 3 minutes before he lost consciousness and pulse. High-quality advanced cardiac life support was initiated, followed by endotracheal intubation. Despite a secured airway and return of spontaneous circulation, the patient remained hypotensive and continued to have seizure-like activity.

The patient was administered a total of 8 mg of lorazepam, sedated with propofol, initiated at 5 μg/kg/min, titrated to stop seizure activity at 15μg/kg/min, and later maintained at 10 μg/kg/min, for a RASS of -1, and started on norepinephrine 0.1 μg/kg/min for acute stabilization. Head computed tomography without contrast showed no acute intracranial pathology as etiology of seizures. Seizure etiology differential at this time was broad; however, hypoxemia due to PE and medication adverse effects were strongly suspected.

The patient’s condition improved, and vasopressor therapy was tapered off the next day. Four days later, the patient was weaned from mechanical ventilation and transferred to the step-down unit. Echocardiogram obtained 48 hours after tPA infusion showed essentially normal left ventricular function (60%-65%), a RVSP of 17 mm Hg and mPAP of 13 mm Hg. The patient’s ProBNP levels markedly decreased to 137 pg/mL. Postextubation, the neurologic examination was at baseline. The Neurology Service recommended temporary treatment with levetiracetam, 1000 mg every 12 hours, and the Hematology Service recommended transitioning to direct oral anticoagulation with follow-up. The patient presented significant clinical and respiratory improvement and was referred for home-based physical rehabilitation as recommended by the physical medicine and rehabilitation service before being discharged.

Case 2

Localized tPA infusion for bilateral PEs via infusion catheters. A 91-year-old male with no history of smoking and a medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, prostate cancer (> 20 years postradiotherapy) and severe osteoarthritis was receiving treatment in the medical ward for medication-induced liver injury secondary to an antibiotic for a urinary tract infection. During the night the patient developed hypotension (86/46 mm Hg), shortness of breath, tachypnea, desaturation, nonradiating retrosternal chest pain, and tachycardia. The hypotension resolved after a 500-mL 0.9 normal saline bolus, and hypoxemia improved with supplemental oxygen via Venturi mask. Chest computed tomography angiography was performed immediately and revealed extensive bilateral acute PE, located most proximally in the right main pulmonary artery (PA) and on the left in the proximal lobar branches, with associated right heart strain. The patient was started on IV heparin with a bolus of 5000 units (80 u/kg) followed by a drip with a partial thromboplastin time goal of 62-103 seconds and transferred to MICU.

Laboratory findings were notable for proBNP that increased from 115 pg/mL to 4470 pg/mL (reference range, < 450 pg/mL for patients aged 75 years) and elevated troponin levels at 218 ng/L to 295 ng/L (reference range, < 22 ng/L), exhibiting chemical evidence of right heart strain. Initial echocardiogram showed mid-right ventricular free wall akinesis with a hypercontractile apex, suggestive of PE (McConnell’s sign) (Figure 3). Interventional Radiology Service was consulted and recommended tPA infusion given that the patient had bilateral PEs and stable blood pressure.

Pulmonary angiogram showed elevated pressures in the right PA of 64/21 mm Hg and the left PA pressures of 63/20 mm Hg. Mechanical disruption of the larger right lower PA thrombus was achieved via a pigtail catheter followed by bilateral catheter bolus infusions of 2 mg tPA (alteplase) and a continuous tPA infusion 0.5 mg/h for 24 hours, in conjunction with a heparin infusion.

After 24 hours of tPA infusion, the catheters were removed, with posttreatment pulmonary angiography demonstrating right and left PA pressures of 42/15 mm Hg and 40/16 mm Hg, respectively. Pre- and postlocalized tPA infusion treatment images are provided for visual comparison (Figure 4). An echocardiogram performed after tPA infusion showed no signs of pulmonary hypertension. The Hematology Service provided recommendations regarding anticoagulation, and after completion of tPA infusion, the patient was transitioned to an unfractioned heparin infusion and subsequently to direct oral anticoagulation prior to transfer back to the medical ward, hemodynamically stable and asymptomatic.

DISCUSSION

PE management can be a straightforward decision when the patient meets criteria for hemodynamic instability, or with small PE burden. In contrast, management can be more challenging in intermediate-risk (submassive) PE when patients remain hemodynamically stable but show signs of cardiopulmonary stress, such as right heart strain, elevated troponins, or increased proBNP levels.2 In these situations, case-by- case evaluation is warranted. A PERT can assess the most beneficial treatment approach by considering factors such as right ventricular dysfunction, hemodynamic status, clot burden, and clinical deterioration despite appropriate anticoagulation. The evidence supporting the benefits these organized teams can provide is growing. These case reports emphasize the need for a multidisciplinary and systematic approach in these complex cases, especially in the management of intermediate-risk PE patients.

Currently, the Veterans Affairs Caribbean Healthcare System does not have an organized PERT, although a multidisciplinary approach was applied in the management of these patients. A systematic, structured team could have decreased time to interventions and alleviated the burden of physician decision-making. Having such a team would streamline the diagnostic pathway for patients presenting from a ward or emergency department with suspected PE.

We present 2 cases of patients found to have a high clot burden from PEs. The patients were initially hemodynamically stable (intermediate-risk PE), but later required systemic or localized thrombolysis due to hemodynamic deterioration despite adequate anticoagulation. Despite similar diagnoses and etiologies, these patients were successfully managed using different approaches, yielding positive outcomes. This reflects the complexity and variability in diagnosing and managing intermediate-risk PE in patients with different comorbidities and clot burden effects. In Case 1, our multidisciplinary approach was obtained via consults to selected services such as interventional radiology, cardiology, and direct involvement of pharmacy. An organized PERT conceivably would have allowed quicker discussions among these services, including hematology, to provide recommendations and collaborative support upon the patient’s arrival to the ED. Additionally, with a PERT team, a systematic approach to these patients could have allowed for an earlier official echocardiogram report for evaluation of right heart strain and develop an adequate therapeutic plan in a timely manner.

In Case 2, consultation with the Interventional Radiology Service yielded a better therapeutic plan, utilizing localized tPA infusion for this older adult patient with increased risk of bleeding with systemic tPA infusion. Having a PERT presents an opportunity to optimize PE management through early recognition, diagnosis, and treatment by institutional consensus from an interdisciplinary team.5,6 These response teams may improve outcomes and prognosis for patients with PE, especially where diagnosis and management is not clear.

The definite etiology of seizure activity in the first case pre- and postcardiac arrest, in the context of no acute intracranial process, remains unknown. Reports have emerged about postreperfusion seizures in acute ischemic stroke, as well as cases of seizures masquerading as PE as the primary presentation. 7,8 However, there were no reports of patients developing seizures post tPA infusion for the treatment of PE. This report may shed light into possible complications secondary to tPA infusion, raising awareness among physicians and encouraging further investigation into its possible etiologies.

CONCLUSIONS

Management of PE can be challenging in patients that meet criteria for intermediate risk. PERTs are a tool that allow for a multidisciplinary, standardized and systematic approach with a diagnostic and treatment algorithm that conceivably would result in a better consensus and therapeutic approach.

- Thompson BT, Kabrhel C. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of acute pulmonary embolism in adults. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Updated December 4, 2023. Accessed February 26, 2025. https://www.uptodate.cn/contents/epidemiology-and-pathogenesis-of-acute-pulmonary-embolism-in-adults

- Kulka HC, Zeller A, Fornaro J, Wuillemin WA, Konstantinides S, Christ M. Acute pulmonary embolism– its diagnosis and treatment from a multidisciplinary viewpoint. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118(37):618-628. doi:10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0226

- Zghouzi M, Mwansa H, Shore S, et al. Sex, racial, and geographic disparities in pulmonary embolism-related mortality nationwide. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023;20(11):1571-1577. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202302-091OC

- Channick RN. The pulmonary embolism response team: why and how? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;42(2):212-217. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1722963

- Rosovsky R, Zhao K, Sista A, Rivera-Lebron B, Kabrhel C. Pulmonary embolism response teams: purpose, evidence for efficacy, and future research directions. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2019;3(3):315-330. doi:10.1002/rth2.12216

- Glazier JJ, Patiño-Velasquez S, Oviedo C. The pulmonary embolism response team: rationale, operation, and outcomes. Int J Angiol. 2022;31(3):198-202. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1750328

- Lekoubou A, Fox J, Ssentongo P. Incidence and association of reperfusion therapies with poststroke seizures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2020;51(9):2715-2723.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.119. 028899

- Alemany M, Nuñez A, Falip M, et al. Acute symptomatic seizures and epilepsy after mechanical thrombectomy. A prospective long-term follow-up study. Seizure. 2021;89:5-9. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2021.04.011

- Thompson BT, Kabrhel C. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of acute pulmonary embolism in adults. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Updated December 4, 2023. Accessed February 26, 2025. https://www.uptodate.cn/contents/epidemiology-and-pathogenesis-of-acute-pulmonary-embolism-in-adults

- Kulka HC, Zeller A, Fornaro J, Wuillemin WA, Konstantinides S, Christ M. Acute pulmonary embolism– its diagnosis and treatment from a multidisciplinary viewpoint. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118(37):618-628. doi:10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0226

- Zghouzi M, Mwansa H, Shore S, et al. Sex, racial, and geographic disparities in pulmonary embolism-related mortality nationwide. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023;20(11):1571-1577. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202302-091OC

- Channick RN. The pulmonary embolism response team: why and how? Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;42(2):212-217. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1722963

- Rosovsky R, Zhao K, Sista A, Rivera-Lebron B, Kabrhel C. Pulmonary embolism response teams: purpose, evidence for efficacy, and future research directions. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2019;3(3):315-330. doi:10.1002/rth2.12216

- Glazier JJ, Patiño-Velasquez S, Oviedo C. The pulmonary embolism response team: rationale, operation, and outcomes. Int J Angiol. 2022;31(3):198-202. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1750328

- Lekoubou A, Fox J, Ssentongo P. Incidence and association of reperfusion therapies with poststroke seizures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2020;51(9):2715-2723.doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.119. 028899

- Alemany M, Nuñez A, Falip M, et al. Acute symptomatic seizures and epilepsy after mechanical thrombectomy. A prospective long-term follow-up study. Seizure. 2021;89:5-9. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2021.04.011

The Need for a Multidisciplinary Approach for Successful High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism Treatment

The Need for a Multidisciplinary Approach for Successful High-Risk Pulmonary Embolism Treatment

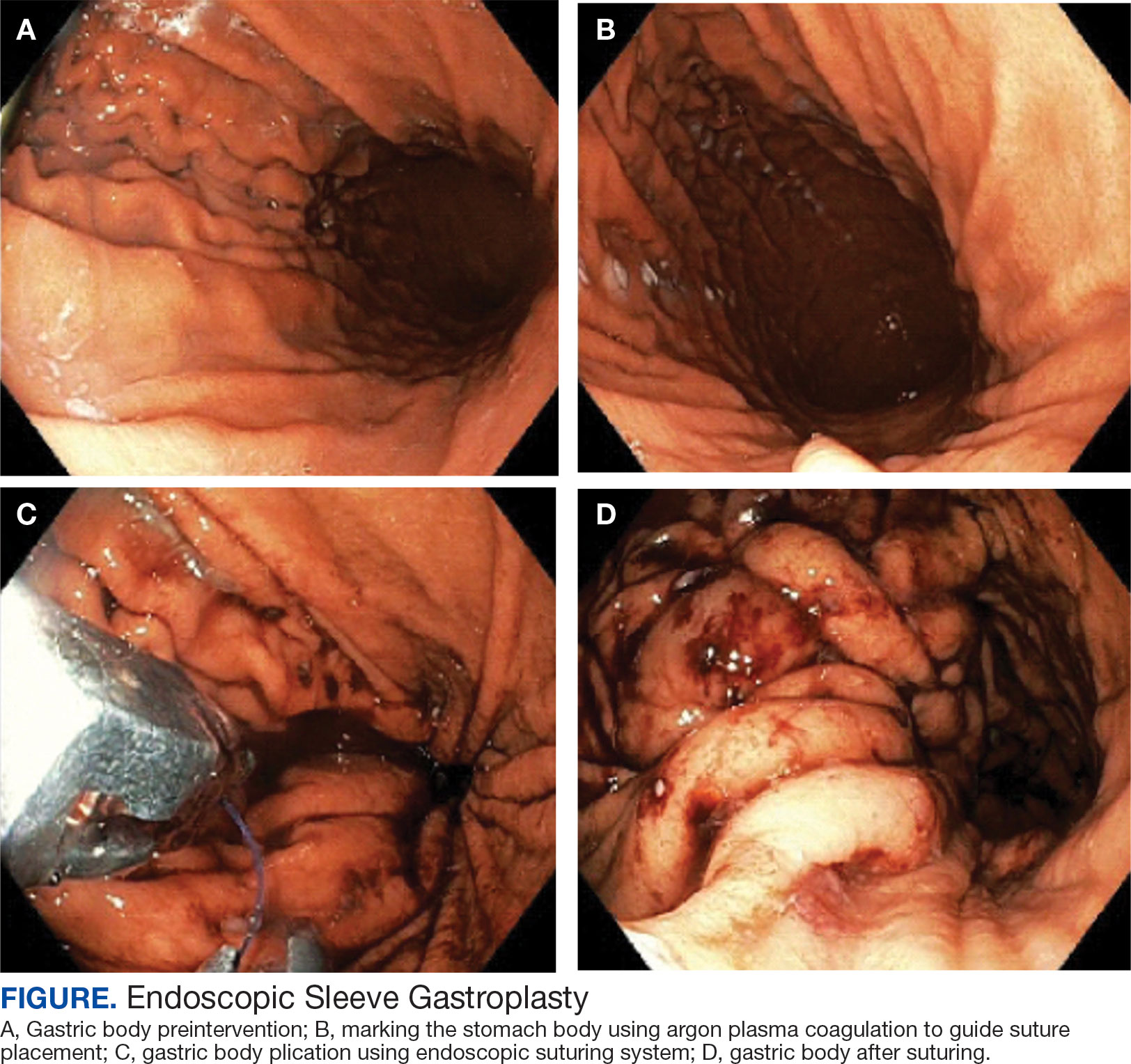

Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty is an Effective Treatment for Obesity in a Veteran With Metabolic and Psychiatric Comorbidities

Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty is an Effective Treatment for Obesity in a Veteran With Metabolic and Psychiatric Comorbidities

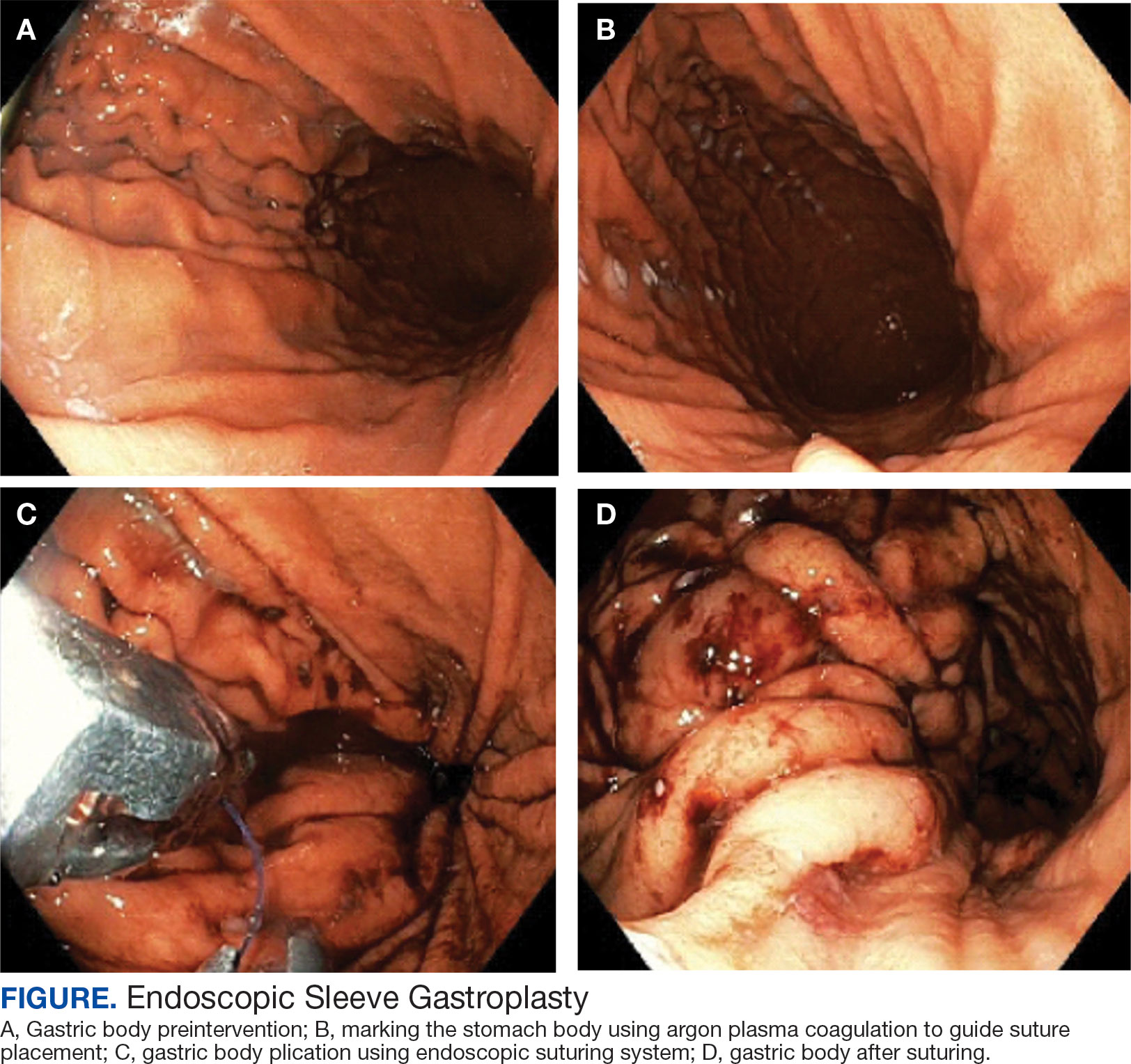

Obesity is a growing worldwide epidemic with significant implications for individual health and public health care costs. It is also associated with several medical conditions, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mental health disorders.1 Comprehensive lifestyle intervention is a first-line therapy for obesity consisting of dietary and exercise interventions. Despite initial success, long-term results and durability of weight loss with lifestyle modifications are limited. 2 Bariatric surgery, including sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass surgery, is a more invasive approach that is highly effective in weight loss. However, these operations are not reversible, and patients may not be eligible for or may not desire surgery. Overall, bariatric surgery is widely underutilized, with < 1% of eligible patients ultimately undergoing surgery.3,4

Endoscopic bariatric therapies are increasingly popular procedures that address the need for additional treatments for obesity among individuals who have not had success with lifestyle changes and are not surgical candidates. The most common procedure is the endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG), which applies full-thickness sutures in the stomach to reduce gastric volume, delay gastric emptying, and limit food intake while keeping the fundus intact compared with sleeve gastrectomy. This procedure is typically considered in patients with body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30, who do not qualify for or do not want traditional bariatric surgery. The literature supports robust outcomes after ESG, with studies demonstrating significant and sustained total body weight loss of up to 14% to 16% at 5 years and significant improvement in ≥ 1 metabolic comorbidities in 80% of patients.5,6 ESG adverse events (AEs) include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting that are typically self-limited to 1 week. Rarer but more serious AEs include bleeding, perforation, or infection, and occur in 2% of cases based on large trial data.5,7

Although the weight loss benefits of ESG are well established, to date, there are limited data on the effects of endoscopic bariatric therapies like ESG on mental health conditions. Here, we describe a case of a veteran with a history of mental health disorders that prevented him from completing bariatric surgery. The patient underwent ESG and had a successful clinical course.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 59-year-old male veteran with a medical history of class III obesity (42.4 BMI), obstructive sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and a large ventral hernia was referred to the MOVE! (Management of Overweight/ Obese Veterans Everywhere!) multidisciplinary high-intensity weight loss program at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) West Los Angeles VA Medical Center (WLAVAMC). His psychiatric history included generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and panic disorder, managed by the Psychiatry Service and treated with sertraline 25 mg daily, lorazepam 0.5 mg twice daily, and hydroxyzine 20 mg nightly. He had previously implemented lifestyle changes and attended MOVE! classes and nutrition coaching for 1 year but was unsuccessful in losing weight. He had also tried liraglutide 3 mg daily for weight loss but was unable to tolerate it and reported worsening medication-related anxiety.