User login

Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Treatment for Glomerulopathy: Case Report and Review of Literature

Podocytes are terminally differentiated, highly specialized cells located in juxtaposition to the basement membrane over the abluminal surfaces of endothelial cells within the glomerular tuft. This triad structure is the site of the filtration barrier, which forms highly delicate and tightly regulated architecture to carry out the ultrafiltration function of the kidney.1 The filtration barrier is characterized by foot processes that are connected by specialized junctions called slit diaphragms.

Insults to components of the filtration barrier can initiate cascading events and perpetuate structural alterations that may eventually result in sclerotic changes.2 Common causes among children include minimal change disease (MCD) with the collapse of foot processes resulting in proteinuria, Alport syndrome due to mutation of collagen fibers within the basement membrane leading to hematuria and proteinuria, immune complex mediated nephropathy following common infections or autoimmune diseases, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) that can show variable histopathology toward eventual glomerular scarring.3,4 These children often clinically have minimal, if any, signs of systemic inflammation.3-5 This has been a limiting factor for the commitment to immunomodulatory treatment, except for steroids for the treatment of MCD.6 Although prolonged steroid treatment may be efficacious, adverse effects are significant in a growing child. Alternative treatments, such as tacrolimus and rituximab have been suggested as second-line steroid-sparing agents.7,8 Not uncommonly, however, these cases are managed by supportive measures only during the progression of the natural course of the disease, which may eventually lead to renal failure, requiring transplant for survival.8,9

This case report highlights a child with a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in genes involved in Alport syndrome and FSGS who developed an abrupt onset of proteinuria and hematuria after a respiratory illness. To our knowledge, he represents the youngest case demonstrating the benefit of targeted treatment against tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for glomerulopathy using biologic response modifiers.

Case Description

This is currently a 7-year-old male patient who was born at 39 weeks gestation to gravida 3 para 3 following induced labor due to elevated maternal blood pressure. During the first 2 years of life, his growth and development were normal and his immunizations were up to date. The patient's medical history included upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), respiratory syncytial virus, as well as 3 bouts of pneumonia and multiple otitis media that resulted in 18 rounds of antibiotics. The child was also allergic to nuts and milk protein. The patient’s parents are of Northern European and Native American descent. There is no known family history of eye, ear, or kidney diseases.

Renal concerns were first noted at the age of 2 years and 6 months when he presented to an emergency department in Fall 2019 (week 0) for several weeks of intermittent dark-colored urine. His mother reported that the discoloration recently progressed in intensity to cola-colored, along with the onset of persistent vomiting without any fever or diarrhea. On physical examination, the patient had normal vitals: weight 14.8 kg (68th percentile), height 91 cm (24th percentile), and body surface area 0.6 m2. There was no edema, rash, or lymphadenopathy, but he appeared pale.

The patient’s initial laboratory results included: complete blood count with white blood cells (WBC) 10 x 103/L (reference range, 4.5-13.5 x 103/L); differential lymphocytes 69%; neutrophils 21%; hemoglobin 10 g/dL (reference range, 12-16 g/dL); hematocrit, 30%; (reference range, 37%-45%); platelets 437 103/L (reference range, 150-450 x 103/L); serum creatinine 0.46 mg/dL (reference range, 0.5-0.9 mg/dL); and albumin 3.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.5-5.2 g/dL). Serum electrolyte levels and liver enzymes were normal. A urine analysis revealed 3+ protein and 3+ blood with dysmorphic red blood cells (RBC) and RBC casts without WBC. The patient's spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 4.3 and his renal ultrasound was normal. The patient was referred to Nephrology.

During the next 2 weeks, his protein-to-creatinine ratio progressed to 5.9 and serum albumin fell to 2.7 g/dL. His urine remained red colored, and a microscopic examination with RBC > 500 and WBC up to 10 on a high powered field. His workup was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antistreptolysin-O (ASO) and anti-DNase B. Serum C3 was low at 81 mg/dL (reference range, 90-180 mg/dL), C4 was 13.3 mg/dL (reference range, 10-40 mg/dL), and immunoglobulin G was low at 452 mg/dL (reference range 719-1475 mg/dL). A baseline audiology test revealed normal hearing.

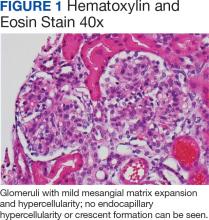

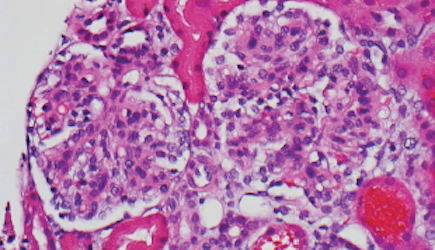

Percutaneous renal biopsy yielded about 12 glomeruli, all exhibiting mild mesangial matrix expansion and hypercellularity (Figure 1). One glomerulus had prominent parietal epithelial cells without endocapillary hypercellularity or crescent formation. There was no interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy. Immunofluorescence studies showed no evidence of immune complex deposition with negative staining for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains, C3 and C1q. Staining for α 2 and α 5 units of collagen was normal. Electron microscopy showed patchy areas of severe basement membrane thinning with frequent foci of mild to moderate lamina densa splitting and associated visceral epithelial cell foot process effacement (Figure 2).

These were reported as concerning findings for possible Alport syndrome by 3 independent pathology teams. The genetic testing was submitted at a commercial laboratory to screen 17 mutations, including COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5. Results showed the presence of a heterozygous VUS in the COL4A4 gene (c.1055C > T; p.Pro352Leu; dbSNP ID: rs371717486; PolyPhen-2: Probably Damaging; SIFT: Deleterious) as well as the presence of a heterozygous VUS in TRPC6 gene (c2463A>T; p.Lys821Asn; dbSNP ID: rs199948731; PolyPhen-2: Benign; SIFT: Tolerated). Further genetic investigation by whole exome sequencing on approximately 20,000 genes through MNG Laboratories showed a new heterozygous VUS in the OSGEP gene [c.328T>C; p.Cys110Arg]. Additional studies ruled out mitochondrial disease, CoQ10 deficiency, and metabolic disorders upon normal findings for mitochondrial DNA, urine amino acids, plasma acylcarnitine profile, orotic acid, ammonia, and homocysteine levels.

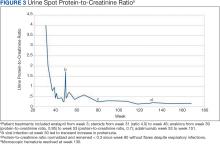

Figure 3 summarizes the patient’s treatment response during 170 weeks of follow-up (Fall 2019 to Summer 2023). The patient was started on enalapril 0.6 mg/kg daily at week 3, which continued throughout treatment. Following a rheumatology consult at week 30, the patient was started on prednisolone 3 mg/mL to assess the role of inflammation through the treatment response. An initial dose of 2 mg/kg daily (9 mL) for 1 month was followed by every other day treatment that was tapered off by week 48. To control mild but noticeably increasing proteinuria in the interim, subcutaneous anakinra 50 mg (3 mg/kg daily) was added as a steroid

DISCUSSION

This case describes a child with rapidly progressive proteinuria and hematuria following a URI who was found to have VUS mutations in 3 different genes associated with chronic kidney disease. Serology tests on the patient were negative for streptococcal antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, ruling out poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. His renal biopsy findings were concerning for altered podocytes, mesangial cells, and basement membrane without inflammatory infiltrate, immune complex, complements, immunoglobulin A, or vasculopathy. His blood inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were normal when his care team initiated daily steroids.

Overall, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathology findings were suggestive of Alport syndrome or thin basement membrane nephropathy with a high potential to progress into FSGS.10-12 Alport syndrome affects 1 in 5000 to 10,000 children annually due to S-linked inheritance of COL4A5, or autosomal recessive inheritance of COL4A3 or COL4A4 genes. It presents with hematuria and hearing loss.10 Our patient had a single copy COL4A4 gene mutation that was classified as VUS. He also had 2 additional VUS affecting the TRPC6 and OSGEP genes. TRPC6 gene mutation can be associated with FSGS through autosomal dominant inheritance. Both COL4A4 and TRPC6 gene mutations were paternally inherited. Although the patient’s father not having renal disease argues against the clinical significance of these findings, there is literature on the potential role of heterozygous COL4A4 variant mimicking thin basement membrane nephropathy that can lead to renal impairment upon copresence of superimposed conditions.13 The patient’s rapidly progressing hematuria and changes in the basement membrane were worrisome for emerging FSGS. Furthermore, VUS of TRPC6 has been reported in late onset autosomal dominant FSGS and can be associated with early onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (NS) in children.14 This concern was voiced by 3 nephrology consultants during the initial evaluation, leading to the consensus that steroid treatment for podocytopathy would not alter the patient’s long-term outcomes (ie, progression to FSGS).

Immunomodulation

Our rationale for immunomodulatory treatment was based on the abrupt onset of renal concerns following a URI, suggesting the importance of an inflammatory trigger causing altered homeostasis in a genetically susceptible host. Preclinical models show that microbial products such as lipopolysaccharides can lead to podocytopathy by several mechanisms through activation of toll-like receptor signaling. It can directly cause apoptosis by downregulation of the intracellular Akt survival pathway.15 Lipopolysaccharide can also activate the NF-αB pathway and upregulate the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and TNF-α in mesangial cells.16,17

Both cytokines can promote mesangial cell proliferation.18 Through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, proinflammatory cytokines can further perpetuate somatic tissue changes and contribute to the development of podocytopathy. For instance, TNF-α can promote podocyte injury and proteinuria by downregulation of the slit diaphragm protein expression (ie, nephrin, ezrin, or podocin), and disruption of podocyte cytoskeleton.19,20 TNF-α promotes the influx and activation of macrophages and inflammatory cells. It is actively involved in chronic alterations within the glomeruli by the upregulation of matrix metalloproteases by integrins, as well as activation of myofibroblast progenitors and extracellular matrix deposition in crosstalk with transforming growth factor and other key mediators.17,21,22

For the patient described in this case report, initial improvement on steroids encouraged the pursuit of additional treatment to downregulate inflammatory pathways within the glomerular milieu. However, within the COVID-19 environment, escalating the patient’s treatment using traditional immunomodulators (ie, calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil) was not favored due to the risk of infection. Initially, anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, was preferred as a steroid-sparing agent for its short life and safety profile during the pandemic. At first, the patient responded well to anakinra and was allowed a steroid wean when the dose was titrated up to 6 mg/kg daily. However, anakinra did not prevent the escalation of proteinuria following a URI. After the treatment was changed to adalimumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, the patient continued to improve and reach full remission despite experiencing a cold and the flu in the following months.

Literature Review

There is a paucity of literature on applications of biological response modifiers for idiopathic NS and FSGS.23,24 Angeletti and colleagues reported that 3 patients with severe long-standing FSGS benefited from anakinra 4 mg/kg daily to reduce proteinuria and improve kidney function. All the patients had positive C3 staining in renal biopsy and treatment response, which supported the role of C3a in inducing podocyte injury through upregulated expression of IL-1 and IL-1R.23 Trachtman and colleagues reported on the phase II FONT trial that included 14 of 21 patients aged < 18 years with advanced FSGS who were treated with adalimumab 24 mg/m2, or ≤ 40 mg every other week.24 Although, during a 6-month period, none of the 7 patients met the endpoint of reduced proteinuria by ≥ 50%, and the authors suggested that careful patient selection may improve the treatment response in future trials.24

A recent study involving transcriptomics on renal tissue samples combined with available pathology (fibrosis), urinary markers, and clinical characteristics on 285 patients with MCD or FSGS from 3 different continents identified 3 distinct clusters. Patients with evidence of activated kidney TNF pathway (n = 72, aged > 18 years) were found to have poor clinical outcomes.25 The study identified 2 urine markers associated with the TNF pathway (ie, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), which aligns with the preclinical findings previously mentioned.25

Conclusions

The patient’s condition in this case illustrates the complex nature of biologically predetermined cascading events in the emergence of glomerular disease upon environmental triggers under the influence of genetic factors.

Chronic kidney disease affects 7.7% of veterans annually, illustrating the need for new therapeutics.26 Based on our experience and literature review, upregulation of TNF-α is a root cause of glomerulopathy; further studies are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of anti-TNF biologic response modifiers for the treatment of these patients. Long-term postmarketing safety profile and steroid-sparing properties of adalimumab should allow inclusion of pediatric cases in future trials. Results may also contribute to identifying new predictive biomarkers related to the basement membrane when combined with precision nephrology to further advance patient selection and targeted treatment.25,27

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient’s mother for providing consent to allow publication of this case report.

1. Arif E, Nihalani D. Glomerular filtration barrier assembly: an insight. Postdoc J. 2013;1(4):33-45.

2. Garg PA. Review of podocyte biology. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47(suppl 1):3-13. doi:10.1159/000481633SUPPL

3. Warady BA, Agarwal R, Bangalore S, et al. Alport syndrome classification and management. Kidney Med. 2020;2(5):639-649. doi:10.1016/j.xkme.2020.05.014

4. Angioi A, Pani A. FSGS: from pathogenesis to the histological lesion. J Nephrol. 2016;29(4):517-523. doi:10.1007/s40620-016-0333-2

5. Roca N, Martinez C, Jatem E, Madrid A, Lopez M, Segarra A. Activation of the acute inflammatory phase response in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: association with clinicopathological phenotypes and with response to corticosteroids. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(4):1207-1215. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfaa247

6. Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F. Minimal change disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):332-345.

7. Medjeral-Thomas NR, Lawrence C, Condon M, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of tacrolimus and prednisolone monotherapy for adults with De Novo minimal change disease: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(2):209-218. doi:10.2215/CJN.06290420

8. Ye Q, Lan B, Liu H, Persson PB, Lai EY, Mao J. A critical role of the podocyte cytoskeleton in the pathogenesis of glomerular proteinuria and autoimmune podocytopathies. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2022;235(4):e13850. doi:10.1111/apha.13850

9. Trautmann A, Schnaidt S, Lipska-Ziμtkiewicz BS, et al. Long-term outcome of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3055-3065. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016101121

10. Kashtan CE, Gross O. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alport syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults-an update for 2020. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(3):711-719. doi:10.1007/s00467-020-04819-6

11. Savige J, Rana K, Tonna S, Buzza M, Dagher H, Wang YY. Thin basement membrane nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64(4):1169-78. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00234.x

12. Rosenberg AZ, Kopp JB. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(3):502-517. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960616

13. Savige J. Should we diagnose autosomal dominant Alport syndrome when there is a pathogenic heterozygous COL4A3 or COL4A4 variant? Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(6):1239-1241. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2018.08.002

14. Gigante M, Caridi G, Montemurno E, et al. TRPC6 mutations in children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and atypical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1626-1634. doi:10.2215/CJN.07830910

15. Saurus P, Kuusela S, Lehtonen E, et al. Podocyte apoptosis is prevented by blocking the toll-like receptor pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(5):e1752. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.125

16. Baud L, Oudinet JP, Bens M, et al. Production of tumor necrosis factor by rat mesangial cells in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Kidney Int. 1989;35(5):1111-1118. doi:10.1038/ki.1989.98

17. White S, Lin L, Hu K. NF-κB and tPA signaling in kidney and other diseases. Cells. 2020;9(6):1348. doi:10.3390/cells9061348

18. Tesch GH, Lan HY, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Role of interleukin-1 in mesangial cell proliferation and matrix deposition in experimental mesangioproliferative nephritis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(1):141-150.

19. Lai KN, Leung JCK, Chan LYY, et al. Podocyte injury induced by mesangial-derived cytokines in IgA Nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):62-72. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn441

20. Saleem MA, Kobayashi Y. Cell biology and genetics of minimal change disease. F1000 Res. 2016;5: F1000 Faculty Rev-412. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7300.1

21. Kim KP, Williams CE, Lemmon CA. Cell-matrix interactions in renal fibrosis. Kidney Dial. 2022;2(4):607-624. doi:10.3390/kidneydial2040055

22. Zvaifler NJ. Relevance of the stroma and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) for the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):210. doi:10.1186/ar1963

23. Angeletti A, Magnasco A, Trivelli A, et al. Refractory minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis treated with Anakinra. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;7(1):121-124. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.018

24. Trachtman H, Vento S, Herreshoff E, et al. Efficacy of galactose and adalimumab in patients with resistant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: report of the font clinical trial group. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:111. doi:10.1186/s12882-015-0094-5

25. Mariani LH, Eddy S, AlAkwaa FM, et al. Precision nephrology identified tumor necrosis factor activation variability in minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2023;103(3):565-579. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2022.10.023

26. Korshak L, Washington DL, Powell J, Nylen E, Kokkinos P. Kidney Disease in Veterans. US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

27. Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G, et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1253-1259. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.305

Podocytes are terminally differentiated, highly specialized cells located in juxtaposition to the basement membrane over the abluminal surfaces of endothelial cells within the glomerular tuft. This triad structure is the site of the filtration barrier, which forms highly delicate and tightly regulated architecture to carry out the ultrafiltration function of the kidney.1 The filtration barrier is characterized by foot processes that are connected by specialized junctions called slit diaphragms.

Insults to components of the filtration barrier can initiate cascading events and perpetuate structural alterations that may eventually result in sclerotic changes.2 Common causes among children include minimal change disease (MCD) with the collapse of foot processes resulting in proteinuria, Alport syndrome due to mutation of collagen fibers within the basement membrane leading to hematuria and proteinuria, immune complex mediated nephropathy following common infections or autoimmune diseases, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) that can show variable histopathology toward eventual glomerular scarring.3,4 These children often clinically have minimal, if any, signs of systemic inflammation.3-5 This has been a limiting factor for the commitment to immunomodulatory treatment, except for steroids for the treatment of MCD.6 Although prolonged steroid treatment may be efficacious, adverse effects are significant in a growing child. Alternative treatments, such as tacrolimus and rituximab have been suggested as second-line steroid-sparing agents.7,8 Not uncommonly, however, these cases are managed by supportive measures only during the progression of the natural course of the disease, which may eventually lead to renal failure, requiring transplant for survival.8,9

This case report highlights a child with a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in genes involved in Alport syndrome and FSGS who developed an abrupt onset of proteinuria and hematuria after a respiratory illness. To our knowledge, he represents the youngest case demonstrating the benefit of targeted treatment against tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for glomerulopathy using biologic response modifiers.

Case Description

This is currently a 7-year-old male patient who was born at 39 weeks gestation to gravida 3 para 3 following induced labor due to elevated maternal blood pressure. During the first 2 years of life, his growth and development were normal and his immunizations were up to date. The patient's medical history included upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), respiratory syncytial virus, as well as 3 bouts of pneumonia and multiple otitis media that resulted in 18 rounds of antibiotics. The child was also allergic to nuts and milk protein. The patient’s parents are of Northern European and Native American descent. There is no known family history of eye, ear, or kidney diseases.

Renal concerns were first noted at the age of 2 years and 6 months when he presented to an emergency department in Fall 2019 (week 0) for several weeks of intermittent dark-colored urine. His mother reported that the discoloration recently progressed in intensity to cola-colored, along with the onset of persistent vomiting without any fever or diarrhea. On physical examination, the patient had normal vitals: weight 14.8 kg (68th percentile), height 91 cm (24th percentile), and body surface area 0.6 m2. There was no edema, rash, or lymphadenopathy, but he appeared pale.

The patient’s initial laboratory results included: complete blood count with white blood cells (WBC) 10 x 103/L (reference range, 4.5-13.5 x 103/L); differential lymphocytes 69%; neutrophils 21%; hemoglobin 10 g/dL (reference range, 12-16 g/dL); hematocrit, 30%; (reference range, 37%-45%); platelets 437 103/L (reference range, 150-450 x 103/L); serum creatinine 0.46 mg/dL (reference range, 0.5-0.9 mg/dL); and albumin 3.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.5-5.2 g/dL). Serum electrolyte levels and liver enzymes were normal. A urine analysis revealed 3+ protein and 3+ blood with dysmorphic red blood cells (RBC) and RBC casts without WBC. The patient's spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 4.3 and his renal ultrasound was normal. The patient was referred to Nephrology.

During the next 2 weeks, his protein-to-creatinine ratio progressed to 5.9 and serum albumin fell to 2.7 g/dL. His urine remained red colored, and a microscopic examination with RBC > 500 and WBC up to 10 on a high powered field. His workup was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antistreptolysin-O (ASO) and anti-DNase B. Serum C3 was low at 81 mg/dL (reference range, 90-180 mg/dL), C4 was 13.3 mg/dL (reference range, 10-40 mg/dL), and immunoglobulin G was low at 452 mg/dL (reference range 719-1475 mg/dL). A baseline audiology test revealed normal hearing.

Percutaneous renal biopsy yielded about 12 glomeruli, all exhibiting mild mesangial matrix expansion and hypercellularity (Figure 1). One glomerulus had prominent parietal epithelial cells without endocapillary hypercellularity or crescent formation. There was no interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy. Immunofluorescence studies showed no evidence of immune complex deposition with negative staining for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains, C3 and C1q. Staining for α 2 and α 5 units of collagen was normal. Electron microscopy showed patchy areas of severe basement membrane thinning with frequent foci of mild to moderate lamina densa splitting and associated visceral epithelial cell foot process effacement (Figure 2).

These were reported as concerning findings for possible Alport syndrome by 3 independent pathology teams. The genetic testing was submitted at a commercial laboratory to screen 17 mutations, including COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5. Results showed the presence of a heterozygous VUS in the COL4A4 gene (c.1055C > T; p.Pro352Leu; dbSNP ID: rs371717486; PolyPhen-2: Probably Damaging; SIFT: Deleterious) as well as the presence of a heterozygous VUS in TRPC6 gene (c2463A>T; p.Lys821Asn; dbSNP ID: rs199948731; PolyPhen-2: Benign; SIFT: Tolerated). Further genetic investigation by whole exome sequencing on approximately 20,000 genes through MNG Laboratories showed a new heterozygous VUS in the OSGEP gene [c.328T>C; p.Cys110Arg]. Additional studies ruled out mitochondrial disease, CoQ10 deficiency, and metabolic disorders upon normal findings for mitochondrial DNA, urine amino acids, plasma acylcarnitine profile, orotic acid, ammonia, and homocysteine levels.

Figure 3 summarizes the patient’s treatment response during 170 weeks of follow-up (Fall 2019 to Summer 2023). The patient was started on enalapril 0.6 mg/kg daily at week 3, which continued throughout treatment. Following a rheumatology consult at week 30, the patient was started on prednisolone 3 mg/mL to assess the role of inflammation through the treatment response. An initial dose of 2 mg/kg daily (9 mL) for 1 month was followed by every other day treatment that was tapered off by week 48. To control mild but noticeably increasing proteinuria in the interim, subcutaneous anakinra 50 mg (3 mg/kg daily) was added as a steroid

DISCUSSION

This case describes a child with rapidly progressive proteinuria and hematuria following a URI who was found to have VUS mutations in 3 different genes associated with chronic kidney disease. Serology tests on the patient were negative for streptococcal antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, ruling out poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. His renal biopsy findings were concerning for altered podocytes, mesangial cells, and basement membrane without inflammatory infiltrate, immune complex, complements, immunoglobulin A, or vasculopathy. His blood inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were normal when his care team initiated daily steroids.

Overall, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathology findings were suggestive of Alport syndrome or thin basement membrane nephropathy with a high potential to progress into FSGS.10-12 Alport syndrome affects 1 in 5000 to 10,000 children annually due to S-linked inheritance of COL4A5, or autosomal recessive inheritance of COL4A3 or COL4A4 genes. It presents with hematuria and hearing loss.10 Our patient had a single copy COL4A4 gene mutation that was classified as VUS. He also had 2 additional VUS affecting the TRPC6 and OSGEP genes. TRPC6 gene mutation can be associated with FSGS through autosomal dominant inheritance. Both COL4A4 and TRPC6 gene mutations were paternally inherited. Although the patient’s father not having renal disease argues against the clinical significance of these findings, there is literature on the potential role of heterozygous COL4A4 variant mimicking thin basement membrane nephropathy that can lead to renal impairment upon copresence of superimposed conditions.13 The patient’s rapidly progressing hematuria and changes in the basement membrane were worrisome for emerging FSGS. Furthermore, VUS of TRPC6 has been reported in late onset autosomal dominant FSGS and can be associated with early onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (NS) in children.14 This concern was voiced by 3 nephrology consultants during the initial evaluation, leading to the consensus that steroid treatment for podocytopathy would not alter the patient’s long-term outcomes (ie, progression to FSGS).

Immunomodulation

Our rationale for immunomodulatory treatment was based on the abrupt onset of renal concerns following a URI, suggesting the importance of an inflammatory trigger causing altered homeostasis in a genetically susceptible host. Preclinical models show that microbial products such as lipopolysaccharides can lead to podocytopathy by several mechanisms through activation of toll-like receptor signaling. It can directly cause apoptosis by downregulation of the intracellular Akt survival pathway.15 Lipopolysaccharide can also activate the NF-αB pathway and upregulate the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and TNF-α in mesangial cells.16,17

Both cytokines can promote mesangial cell proliferation.18 Through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, proinflammatory cytokines can further perpetuate somatic tissue changes and contribute to the development of podocytopathy. For instance, TNF-α can promote podocyte injury and proteinuria by downregulation of the slit diaphragm protein expression (ie, nephrin, ezrin, or podocin), and disruption of podocyte cytoskeleton.19,20 TNF-α promotes the influx and activation of macrophages and inflammatory cells. It is actively involved in chronic alterations within the glomeruli by the upregulation of matrix metalloproteases by integrins, as well as activation of myofibroblast progenitors and extracellular matrix deposition in crosstalk with transforming growth factor and other key mediators.17,21,22

For the patient described in this case report, initial improvement on steroids encouraged the pursuit of additional treatment to downregulate inflammatory pathways within the glomerular milieu. However, within the COVID-19 environment, escalating the patient’s treatment using traditional immunomodulators (ie, calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil) was not favored due to the risk of infection. Initially, anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, was preferred as a steroid-sparing agent for its short life and safety profile during the pandemic. At first, the patient responded well to anakinra and was allowed a steroid wean when the dose was titrated up to 6 mg/kg daily. However, anakinra did not prevent the escalation of proteinuria following a URI. After the treatment was changed to adalimumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, the patient continued to improve and reach full remission despite experiencing a cold and the flu in the following months.

Literature Review

There is a paucity of literature on applications of biological response modifiers for idiopathic NS and FSGS.23,24 Angeletti and colleagues reported that 3 patients with severe long-standing FSGS benefited from anakinra 4 mg/kg daily to reduce proteinuria and improve kidney function. All the patients had positive C3 staining in renal biopsy and treatment response, which supported the role of C3a in inducing podocyte injury through upregulated expression of IL-1 and IL-1R.23 Trachtman and colleagues reported on the phase II FONT trial that included 14 of 21 patients aged < 18 years with advanced FSGS who were treated with adalimumab 24 mg/m2, or ≤ 40 mg every other week.24 Although, during a 6-month period, none of the 7 patients met the endpoint of reduced proteinuria by ≥ 50%, and the authors suggested that careful patient selection may improve the treatment response in future trials.24

A recent study involving transcriptomics on renal tissue samples combined with available pathology (fibrosis), urinary markers, and clinical characteristics on 285 patients with MCD or FSGS from 3 different continents identified 3 distinct clusters. Patients with evidence of activated kidney TNF pathway (n = 72, aged > 18 years) were found to have poor clinical outcomes.25 The study identified 2 urine markers associated with the TNF pathway (ie, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), which aligns with the preclinical findings previously mentioned.25

Conclusions

The patient’s condition in this case illustrates the complex nature of biologically predetermined cascading events in the emergence of glomerular disease upon environmental triggers under the influence of genetic factors.

Chronic kidney disease affects 7.7% of veterans annually, illustrating the need for new therapeutics.26 Based on our experience and literature review, upregulation of TNF-α is a root cause of glomerulopathy; further studies are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of anti-TNF biologic response modifiers for the treatment of these patients. Long-term postmarketing safety profile and steroid-sparing properties of adalimumab should allow inclusion of pediatric cases in future trials. Results may also contribute to identifying new predictive biomarkers related to the basement membrane when combined with precision nephrology to further advance patient selection and targeted treatment.25,27

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient’s mother for providing consent to allow publication of this case report.

Podocytes are terminally differentiated, highly specialized cells located in juxtaposition to the basement membrane over the abluminal surfaces of endothelial cells within the glomerular tuft. This triad structure is the site of the filtration barrier, which forms highly delicate and tightly regulated architecture to carry out the ultrafiltration function of the kidney.1 The filtration barrier is characterized by foot processes that are connected by specialized junctions called slit diaphragms.

Insults to components of the filtration barrier can initiate cascading events and perpetuate structural alterations that may eventually result in sclerotic changes.2 Common causes among children include minimal change disease (MCD) with the collapse of foot processes resulting in proteinuria, Alport syndrome due to mutation of collagen fibers within the basement membrane leading to hematuria and proteinuria, immune complex mediated nephropathy following common infections or autoimmune diseases, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) that can show variable histopathology toward eventual glomerular scarring.3,4 These children often clinically have minimal, if any, signs of systemic inflammation.3-5 This has been a limiting factor for the commitment to immunomodulatory treatment, except for steroids for the treatment of MCD.6 Although prolonged steroid treatment may be efficacious, adverse effects are significant in a growing child. Alternative treatments, such as tacrolimus and rituximab have been suggested as second-line steroid-sparing agents.7,8 Not uncommonly, however, these cases are managed by supportive measures only during the progression of the natural course of the disease, which may eventually lead to renal failure, requiring transplant for survival.8,9

This case report highlights a child with a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in genes involved in Alport syndrome and FSGS who developed an abrupt onset of proteinuria and hematuria after a respiratory illness. To our knowledge, he represents the youngest case demonstrating the benefit of targeted treatment against tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for glomerulopathy using biologic response modifiers.

Case Description

This is currently a 7-year-old male patient who was born at 39 weeks gestation to gravida 3 para 3 following induced labor due to elevated maternal blood pressure. During the first 2 years of life, his growth and development were normal and his immunizations were up to date. The patient's medical history included upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), respiratory syncytial virus, as well as 3 bouts of pneumonia and multiple otitis media that resulted in 18 rounds of antibiotics. The child was also allergic to nuts and milk protein. The patient’s parents are of Northern European and Native American descent. There is no known family history of eye, ear, or kidney diseases.

Renal concerns were first noted at the age of 2 years and 6 months when he presented to an emergency department in Fall 2019 (week 0) for several weeks of intermittent dark-colored urine. His mother reported that the discoloration recently progressed in intensity to cola-colored, along with the onset of persistent vomiting without any fever or diarrhea. On physical examination, the patient had normal vitals: weight 14.8 kg (68th percentile), height 91 cm (24th percentile), and body surface area 0.6 m2. There was no edema, rash, or lymphadenopathy, but he appeared pale.

The patient’s initial laboratory results included: complete blood count with white blood cells (WBC) 10 x 103/L (reference range, 4.5-13.5 x 103/L); differential lymphocytes 69%; neutrophils 21%; hemoglobin 10 g/dL (reference range, 12-16 g/dL); hematocrit, 30%; (reference range, 37%-45%); platelets 437 103/L (reference range, 150-450 x 103/L); serum creatinine 0.46 mg/dL (reference range, 0.5-0.9 mg/dL); and albumin 3.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.5-5.2 g/dL). Serum electrolyte levels and liver enzymes were normal. A urine analysis revealed 3+ protein and 3+ blood with dysmorphic red blood cells (RBC) and RBC casts without WBC. The patient's spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 4.3 and his renal ultrasound was normal. The patient was referred to Nephrology.

During the next 2 weeks, his protein-to-creatinine ratio progressed to 5.9 and serum albumin fell to 2.7 g/dL. His urine remained red colored, and a microscopic examination with RBC > 500 and WBC up to 10 on a high powered field. His workup was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antistreptolysin-O (ASO) and anti-DNase B. Serum C3 was low at 81 mg/dL (reference range, 90-180 mg/dL), C4 was 13.3 mg/dL (reference range, 10-40 mg/dL), and immunoglobulin G was low at 452 mg/dL (reference range 719-1475 mg/dL). A baseline audiology test revealed normal hearing.

Percutaneous renal biopsy yielded about 12 glomeruli, all exhibiting mild mesangial matrix expansion and hypercellularity (Figure 1). One glomerulus had prominent parietal epithelial cells without endocapillary hypercellularity or crescent formation. There was no interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy. Immunofluorescence studies showed no evidence of immune complex deposition with negative staining for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains, C3 and C1q. Staining for α 2 and α 5 units of collagen was normal. Electron microscopy showed patchy areas of severe basement membrane thinning with frequent foci of mild to moderate lamina densa splitting and associated visceral epithelial cell foot process effacement (Figure 2).

These were reported as concerning findings for possible Alport syndrome by 3 independent pathology teams. The genetic testing was submitted at a commercial laboratory to screen 17 mutations, including COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5. Results showed the presence of a heterozygous VUS in the COL4A4 gene (c.1055C > T; p.Pro352Leu; dbSNP ID: rs371717486; PolyPhen-2: Probably Damaging; SIFT: Deleterious) as well as the presence of a heterozygous VUS in TRPC6 gene (c2463A>T; p.Lys821Asn; dbSNP ID: rs199948731; PolyPhen-2: Benign; SIFT: Tolerated). Further genetic investigation by whole exome sequencing on approximately 20,000 genes through MNG Laboratories showed a new heterozygous VUS in the OSGEP gene [c.328T>C; p.Cys110Arg]. Additional studies ruled out mitochondrial disease, CoQ10 deficiency, and metabolic disorders upon normal findings for mitochondrial DNA, urine amino acids, plasma acylcarnitine profile, orotic acid, ammonia, and homocysteine levels.

Figure 3 summarizes the patient’s treatment response during 170 weeks of follow-up (Fall 2019 to Summer 2023). The patient was started on enalapril 0.6 mg/kg daily at week 3, which continued throughout treatment. Following a rheumatology consult at week 30, the patient was started on prednisolone 3 mg/mL to assess the role of inflammation through the treatment response. An initial dose of 2 mg/kg daily (9 mL) for 1 month was followed by every other day treatment that was tapered off by week 48. To control mild but noticeably increasing proteinuria in the interim, subcutaneous anakinra 50 mg (3 mg/kg daily) was added as a steroid

DISCUSSION

This case describes a child with rapidly progressive proteinuria and hematuria following a URI who was found to have VUS mutations in 3 different genes associated with chronic kidney disease. Serology tests on the patient were negative for streptococcal antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, ruling out poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. His renal biopsy findings were concerning for altered podocytes, mesangial cells, and basement membrane without inflammatory infiltrate, immune complex, complements, immunoglobulin A, or vasculopathy. His blood inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were normal when his care team initiated daily steroids.

Overall, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathology findings were suggestive of Alport syndrome or thin basement membrane nephropathy with a high potential to progress into FSGS.10-12 Alport syndrome affects 1 in 5000 to 10,000 children annually due to S-linked inheritance of COL4A5, or autosomal recessive inheritance of COL4A3 or COL4A4 genes. It presents with hematuria and hearing loss.10 Our patient had a single copy COL4A4 gene mutation that was classified as VUS. He also had 2 additional VUS affecting the TRPC6 and OSGEP genes. TRPC6 gene mutation can be associated with FSGS through autosomal dominant inheritance. Both COL4A4 and TRPC6 gene mutations were paternally inherited. Although the patient’s father not having renal disease argues against the clinical significance of these findings, there is literature on the potential role of heterozygous COL4A4 variant mimicking thin basement membrane nephropathy that can lead to renal impairment upon copresence of superimposed conditions.13 The patient’s rapidly progressing hematuria and changes in the basement membrane were worrisome for emerging FSGS. Furthermore, VUS of TRPC6 has been reported in late onset autosomal dominant FSGS and can be associated with early onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (NS) in children.14 This concern was voiced by 3 nephrology consultants during the initial evaluation, leading to the consensus that steroid treatment for podocytopathy would not alter the patient’s long-term outcomes (ie, progression to FSGS).

Immunomodulation

Our rationale for immunomodulatory treatment was based on the abrupt onset of renal concerns following a URI, suggesting the importance of an inflammatory trigger causing altered homeostasis in a genetically susceptible host. Preclinical models show that microbial products such as lipopolysaccharides can lead to podocytopathy by several mechanisms through activation of toll-like receptor signaling. It can directly cause apoptosis by downregulation of the intracellular Akt survival pathway.15 Lipopolysaccharide can also activate the NF-αB pathway and upregulate the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and TNF-α in mesangial cells.16,17

Both cytokines can promote mesangial cell proliferation.18 Through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, proinflammatory cytokines can further perpetuate somatic tissue changes and contribute to the development of podocytopathy. For instance, TNF-α can promote podocyte injury and proteinuria by downregulation of the slit diaphragm protein expression (ie, nephrin, ezrin, or podocin), and disruption of podocyte cytoskeleton.19,20 TNF-α promotes the influx and activation of macrophages and inflammatory cells. It is actively involved in chronic alterations within the glomeruli by the upregulation of matrix metalloproteases by integrins, as well as activation of myofibroblast progenitors and extracellular matrix deposition in crosstalk with transforming growth factor and other key mediators.17,21,22

For the patient described in this case report, initial improvement on steroids encouraged the pursuit of additional treatment to downregulate inflammatory pathways within the glomerular milieu. However, within the COVID-19 environment, escalating the patient’s treatment using traditional immunomodulators (ie, calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil) was not favored due to the risk of infection. Initially, anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, was preferred as a steroid-sparing agent for its short life and safety profile during the pandemic. At first, the patient responded well to anakinra and was allowed a steroid wean when the dose was titrated up to 6 mg/kg daily. However, anakinra did not prevent the escalation of proteinuria following a URI. After the treatment was changed to adalimumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, the patient continued to improve and reach full remission despite experiencing a cold and the flu in the following months.

Literature Review

There is a paucity of literature on applications of biological response modifiers for idiopathic NS and FSGS.23,24 Angeletti and colleagues reported that 3 patients with severe long-standing FSGS benefited from anakinra 4 mg/kg daily to reduce proteinuria and improve kidney function. All the patients had positive C3 staining in renal biopsy and treatment response, which supported the role of C3a in inducing podocyte injury through upregulated expression of IL-1 and IL-1R.23 Trachtman and colleagues reported on the phase II FONT trial that included 14 of 21 patients aged < 18 years with advanced FSGS who were treated with adalimumab 24 mg/m2, or ≤ 40 mg every other week.24 Although, during a 6-month period, none of the 7 patients met the endpoint of reduced proteinuria by ≥ 50%, and the authors suggested that careful patient selection may improve the treatment response in future trials.24

A recent study involving transcriptomics on renal tissue samples combined with available pathology (fibrosis), urinary markers, and clinical characteristics on 285 patients with MCD or FSGS from 3 different continents identified 3 distinct clusters. Patients with evidence of activated kidney TNF pathway (n = 72, aged > 18 years) were found to have poor clinical outcomes.25 The study identified 2 urine markers associated with the TNF pathway (ie, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), which aligns with the preclinical findings previously mentioned.25

Conclusions

The patient’s condition in this case illustrates the complex nature of biologically predetermined cascading events in the emergence of glomerular disease upon environmental triggers under the influence of genetic factors.

Chronic kidney disease affects 7.7% of veterans annually, illustrating the need for new therapeutics.26 Based on our experience and literature review, upregulation of TNF-α is a root cause of glomerulopathy; further studies are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of anti-TNF biologic response modifiers for the treatment of these patients. Long-term postmarketing safety profile and steroid-sparing properties of adalimumab should allow inclusion of pediatric cases in future trials. Results may also contribute to identifying new predictive biomarkers related to the basement membrane when combined with precision nephrology to further advance patient selection and targeted treatment.25,27

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient’s mother for providing consent to allow publication of this case report.

1. Arif E, Nihalani D. Glomerular filtration barrier assembly: an insight. Postdoc J. 2013;1(4):33-45.

2. Garg PA. Review of podocyte biology. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47(suppl 1):3-13. doi:10.1159/000481633SUPPL

3. Warady BA, Agarwal R, Bangalore S, et al. Alport syndrome classification and management. Kidney Med. 2020;2(5):639-649. doi:10.1016/j.xkme.2020.05.014

4. Angioi A, Pani A. FSGS: from pathogenesis to the histological lesion. J Nephrol. 2016;29(4):517-523. doi:10.1007/s40620-016-0333-2

5. Roca N, Martinez C, Jatem E, Madrid A, Lopez M, Segarra A. Activation of the acute inflammatory phase response in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: association with clinicopathological phenotypes and with response to corticosteroids. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(4):1207-1215. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfaa247

6. Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F. Minimal change disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):332-345.

7. Medjeral-Thomas NR, Lawrence C, Condon M, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of tacrolimus and prednisolone monotherapy for adults with De Novo minimal change disease: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(2):209-218. doi:10.2215/CJN.06290420

8. Ye Q, Lan B, Liu H, Persson PB, Lai EY, Mao J. A critical role of the podocyte cytoskeleton in the pathogenesis of glomerular proteinuria and autoimmune podocytopathies. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2022;235(4):e13850. doi:10.1111/apha.13850

9. Trautmann A, Schnaidt S, Lipska-Ziμtkiewicz BS, et al. Long-term outcome of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3055-3065. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016101121

10. Kashtan CE, Gross O. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alport syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults-an update for 2020. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(3):711-719. doi:10.1007/s00467-020-04819-6

11. Savige J, Rana K, Tonna S, Buzza M, Dagher H, Wang YY. Thin basement membrane nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64(4):1169-78. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00234.x

12. Rosenberg AZ, Kopp JB. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(3):502-517. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960616

13. Savige J. Should we diagnose autosomal dominant Alport syndrome when there is a pathogenic heterozygous COL4A3 or COL4A4 variant? Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(6):1239-1241. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2018.08.002

14. Gigante M, Caridi G, Montemurno E, et al. TRPC6 mutations in children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and atypical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1626-1634. doi:10.2215/CJN.07830910

15. Saurus P, Kuusela S, Lehtonen E, et al. Podocyte apoptosis is prevented by blocking the toll-like receptor pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(5):e1752. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.125

16. Baud L, Oudinet JP, Bens M, et al. Production of tumor necrosis factor by rat mesangial cells in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Kidney Int. 1989;35(5):1111-1118. doi:10.1038/ki.1989.98

17. White S, Lin L, Hu K. NF-κB and tPA signaling in kidney and other diseases. Cells. 2020;9(6):1348. doi:10.3390/cells9061348

18. Tesch GH, Lan HY, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Role of interleukin-1 in mesangial cell proliferation and matrix deposition in experimental mesangioproliferative nephritis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(1):141-150.

19. Lai KN, Leung JCK, Chan LYY, et al. Podocyte injury induced by mesangial-derived cytokines in IgA Nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):62-72. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn441

20. Saleem MA, Kobayashi Y. Cell biology and genetics of minimal change disease. F1000 Res. 2016;5: F1000 Faculty Rev-412. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7300.1

21. Kim KP, Williams CE, Lemmon CA. Cell-matrix interactions in renal fibrosis. Kidney Dial. 2022;2(4):607-624. doi:10.3390/kidneydial2040055

22. Zvaifler NJ. Relevance of the stroma and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) for the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):210. doi:10.1186/ar1963

23. Angeletti A, Magnasco A, Trivelli A, et al. Refractory minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis treated with Anakinra. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;7(1):121-124. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.018

24. Trachtman H, Vento S, Herreshoff E, et al. Efficacy of galactose and adalimumab in patients with resistant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: report of the font clinical trial group. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:111. doi:10.1186/s12882-015-0094-5

25. Mariani LH, Eddy S, AlAkwaa FM, et al. Precision nephrology identified tumor necrosis factor activation variability in minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2023;103(3):565-579. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2022.10.023

26. Korshak L, Washington DL, Powell J, Nylen E, Kokkinos P. Kidney Disease in Veterans. US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

27. Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G, et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1253-1259. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.305

1. Arif E, Nihalani D. Glomerular filtration barrier assembly: an insight. Postdoc J. 2013;1(4):33-45.

2. Garg PA. Review of podocyte biology. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47(suppl 1):3-13. doi:10.1159/000481633SUPPL

3. Warady BA, Agarwal R, Bangalore S, et al. Alport syndrome classification and management. Kidney Med. 2020;2(5):639-649. doi:10.1016/j.xkme.2020.05.014

4. Angioi A, Pani A. FSGS: from pathogenesis to the histological lesion. J Nephrol. 2016;29(4):517-523. doi:10.1007/s40620-016-0333-2

5. Roca N, Martinez C, Jatem E, Madrid A, Lopez M, Segarra A. Activation of the acute inflammatory phase response in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: association with clinicopathological phenotypes and with response to corticosteroids. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(4):1207-1215. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfaa247

6. Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F. Minimal change disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):332-345.

7. Medjeral-Thomas NR, Lawrence C, Condon M, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of tacrolimus and prednisolone monotherapy for adults with De Novo minimal change disease: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(2):209-218. doi:10.2215/CJN.06290420

8. Ye Q, Lan B, Liu H, Persson PB, Lai EY, Mao J. A critical role of the podocyte cytoskeleton in the pathogenesis of glomerular proteinuria and autoimmune podocytopathies. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2022;235(4):e13850. doi:10.1111/apha.13850

9. Trautmann A, Schnaidt S, Lipska-Ziμtkiewicz BS, et al. Long-term outcome of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3055-3065. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016101121

10. Kashtan CE, Gross O. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alport syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults-an update for 2020. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(3):711-719. doi:10.1007/s00467-020-04819-6

11. Savige J, Rana K, Tonna S, Buzza M, Dagher H, Wang YY. Thin basement membrane nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64(4):1169-78. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00234.x

12. Rosenberg AZ, Kopp JB. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(3):502-517. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960616

13. Savige J. Should we diagnose autosomal dominant Alport syndrome when there is a pathogenic heterozygous COL4A3 or COL4A4 variant? Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(6):1239-1241. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2018.08.002

14. Gigante M, Caridi G, Montemurno E, et al. TRPC6 mutations in children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and atypical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1626-1634. doi:10.2215/CJN.07830910

15. Saurus P, Kuusela S, Lehtonen E, et al. Podocyte apoptosis is prevented by blocking the toll-like receptor pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(5):e1752. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.125

16. Baud L, Oudinet JP, Bens M, et al. Production of tumor necrosis factor by rat mesangial cells in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Kidney Int. 1989;35(5):1111-1118. doi:10.1038/ki.1989.98

17. White S, Lin L, Hu K. NF-κB and tPA signaling in kidney and other diseases. Cells. 2020;9(6):1348. doi:10.3390/cells9061348

18. Tesch GH, Lan HY, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Role of interleukin-1 in mesangial cell proliferation and matrix deposition in experimental mesangioproliferative nephritis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(1):141-150.

19. Lai KN, Leung JCK, Chan LYY, et al. Podocyte injury induced by mesangial-derived cytokines in IgA Nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):62-72. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn441

20. Saleem MA, Kobayashi Y. Cell biology and genetics of minimal change disease. F1000 Res. 2016;5: F1000 Faculty Rev-412. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7300.1

21. Kim KP, Williams CE, Lemmon CA. Cell-matrix interactions in renal fibrosis. Kidney Dial. 2022;2(4):607-624. doi:10.3390/kidneydial2040055

22. Zvaifler NJ. Relevance of the stroma and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) for the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):210. doi:10.1186/ar1963

23. Angeletti A, Magnasco A, Trivelli A, et al. Refractory minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis treated with Anakinra. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;7(1):121-124. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.018

24. Trachtman H, Vento S, Herreshoff E, et al. Efficacy of galactose and adalimumab in patients with resistant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: report of the font clinical trial group. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:111. doi:10.1186/s12882-015-0094-5

25. Mariani LH, Eddy S, AlAkwaa FM, et al. Precision nephrology identified tumor necrosis factor activation variability in minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2023;103(3):565-579. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2022.10.023

26. Korshak L, Washington DL, Powell J, Nylen E, Kokkinos P. Kidney Disease in Veterans. US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

27. Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G, et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1253-1259. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.305

A Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Incidence Surveillance Report Among DoD Beneficiaries During the COVID-19 Pandemic

A Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Incidence Surveillance Report Among DoD Beneficiaries During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or lupus, is a rare autoimmune disease estimated to occur in about 5.1 cases per 100,000 person-years in the United States in 2018.1 The disease predominantly affects females, with an incidence of 8.7 cases per 100,000 person-years vs 1.2 cases per 100,000 person-years in males, and is most common in patients aged 15 to 44 years.1,2

Lupus presents with a constellation of clinical signs and symptoms that evolve, along with hallmark laboratory findings indicative of immune dysregulation and polyclonal B-cell activation. Consequently, a wide array of autoantibodies may be produced, although the combination of epitope specificity can vary from patient to patient.3 Nevertheless, > 98% of individuals diagnosed with lupus produce antinuclear antibodies (ANA), making ANA positivity a near-universal serologic feature at the time of diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of lupus is complex. Research from the past 5 decades supports the role of certain viral infections—such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus—as potential triggers.4 These viruses are thought to initiate disease through mechanisms including activation of interferon pathways, exposure of cryptic intracellular antigens, molecular mimicry, and epitope spreading. Subsequent clonal expansion and autoantibody production occur to varying degrees, influenced by viral load and host susceptibility factors.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became evident that SARS-CoV-2 exerts profound effects on immune regulation, influencing infection outcomes through mechanisms such as hyperactivation of innate immunity, especially in the lungs, leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 has been associated with polyclonal B-cell activation and the generation of autoantibodies. This association gained attention after Bastard et al identified anti–type I interferon antibodies in patients with severe COVID-19, predominantly among males with a genetic predisposition. These autoantibodies were shown to impair antiviral defenses and contribute to life-threatening pneumonia.5

Subsequent studies demonstrated the production of a wide spectrum of functional autoantibodies, including ANA, in patients with COVID-19.6,7 These findings were attributed to the acute expansion of autoreactive clones among naïve-derived immunoglobulin G1 antibody-secreting cells during the early stages of infection, with the degree of expansion correlating with disease severity.8,9 Although longitudinal data up to 15 months postinfection suggest this serologic abnormality resolves in more than two-thirds of patients, the number of individuals infected globally has raised serious public health concerns regarding the potential long-term sequelae, including the onset of lupus or other autoimmune diseases in COVID-19 survivors.6-9 A limited number of case reports describing the onset of lupus following SARS-CoV-2 infection support this hypothesis.10

This surveillance analysis investigates lupus incidence among patients within the Military Health System (MHS), encompassing all TRICARE beneficiaries, from January 2018 to December 2022. The objective of this analysis was to examine lupus incidence trends throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, stratified by sex, age, and active-duty status.

Methods

The MHS provides health care services to about 9.5 million US Department of Defense (DoD) beneficiaries. Outpatient health records and laboratory results for individuals receiving care at military treatment facilities (MTFs) between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2022, were obtained from the Comprehensive Ambulatory/ Professional Encounter Record and MHS GENESIS. For beneficiaries receiving care in the private sector, data were sourced from the TRICARE Encounter Data—Non-Institutional database.

Laboratory test results, including ANA testing, were available only for individuals receiving care at MTFs. These laboratory data were extracted from the Composite Health Care System Chemistry database and MHS GENESIS laboratory systems for the same time frame. Inpatient data were not included in this analysis. Data from 2017 were used solely as a look-back (or washout) period to identify and exclude prevalent lupus cases diagnosed before 2018 and were not included in the final results.

Lupus cases were identified by the presence of a positive ANA test and appropriate International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes. A positive ANA result was defined as either a qualitative result marked positive or a titer ≥ 1:80. The ICD-10-CM codes considered indicative of lupus included variations of M32, L93, or H01.12.

M32, L93, or H01.12. For cases with a positive ANA test, a lupus diagnosis required the presence of ≥ 2 lupus related ICD-10-CM codes. In the absence of ANA test results, a stricter criterion was applied: ≥ 4 lupus ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes recorded on separate days were required for inclusion.

Beneficiaries were excluded if they had a negative ANA result, only 1 lupus ICD- 10-CM diagnosis code, 1 positive ANA with only 1 corresponding ICD-10-CM code, or if their diagnosis occurred outside the defined study period. Patients and members of the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination of this study.

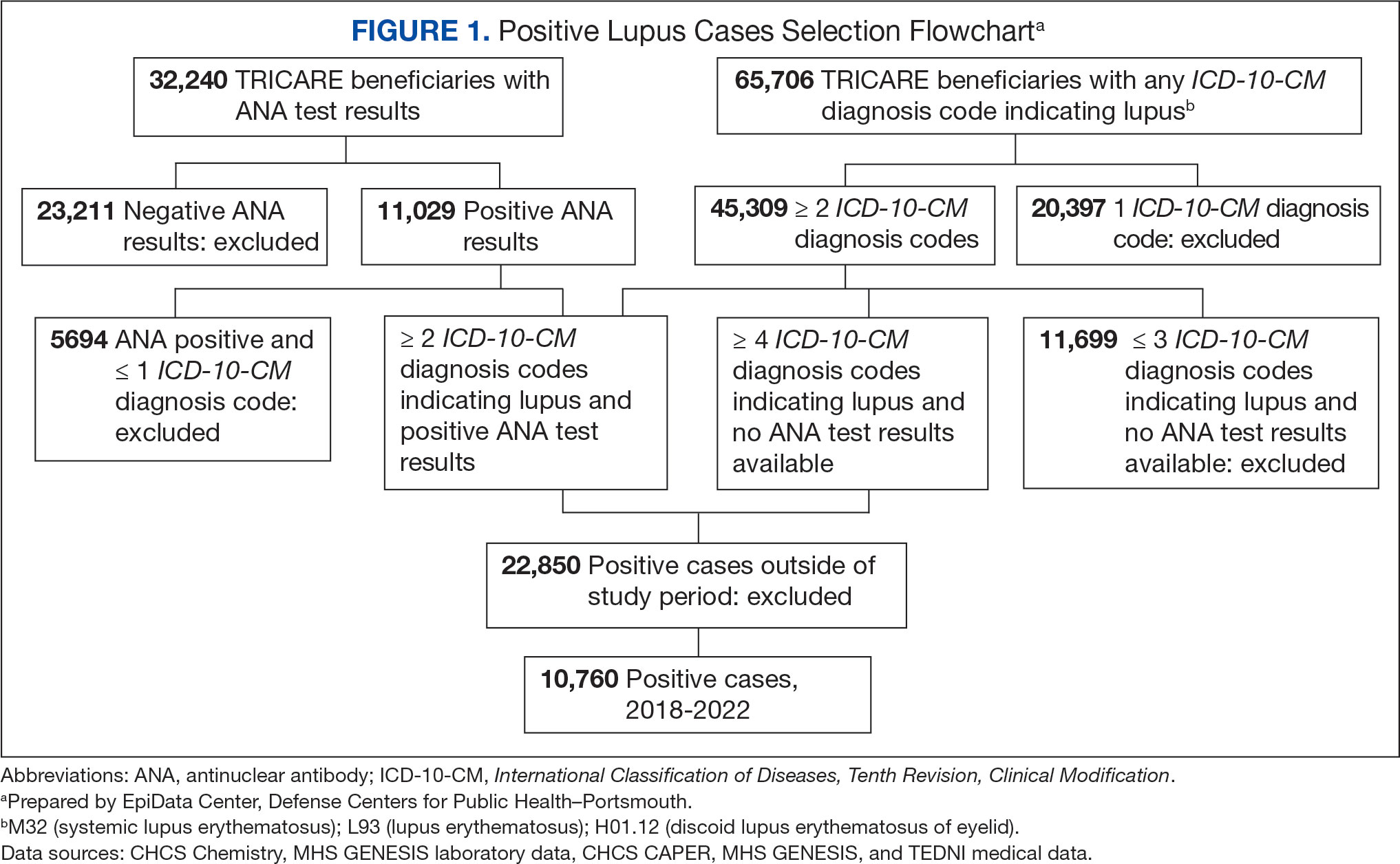

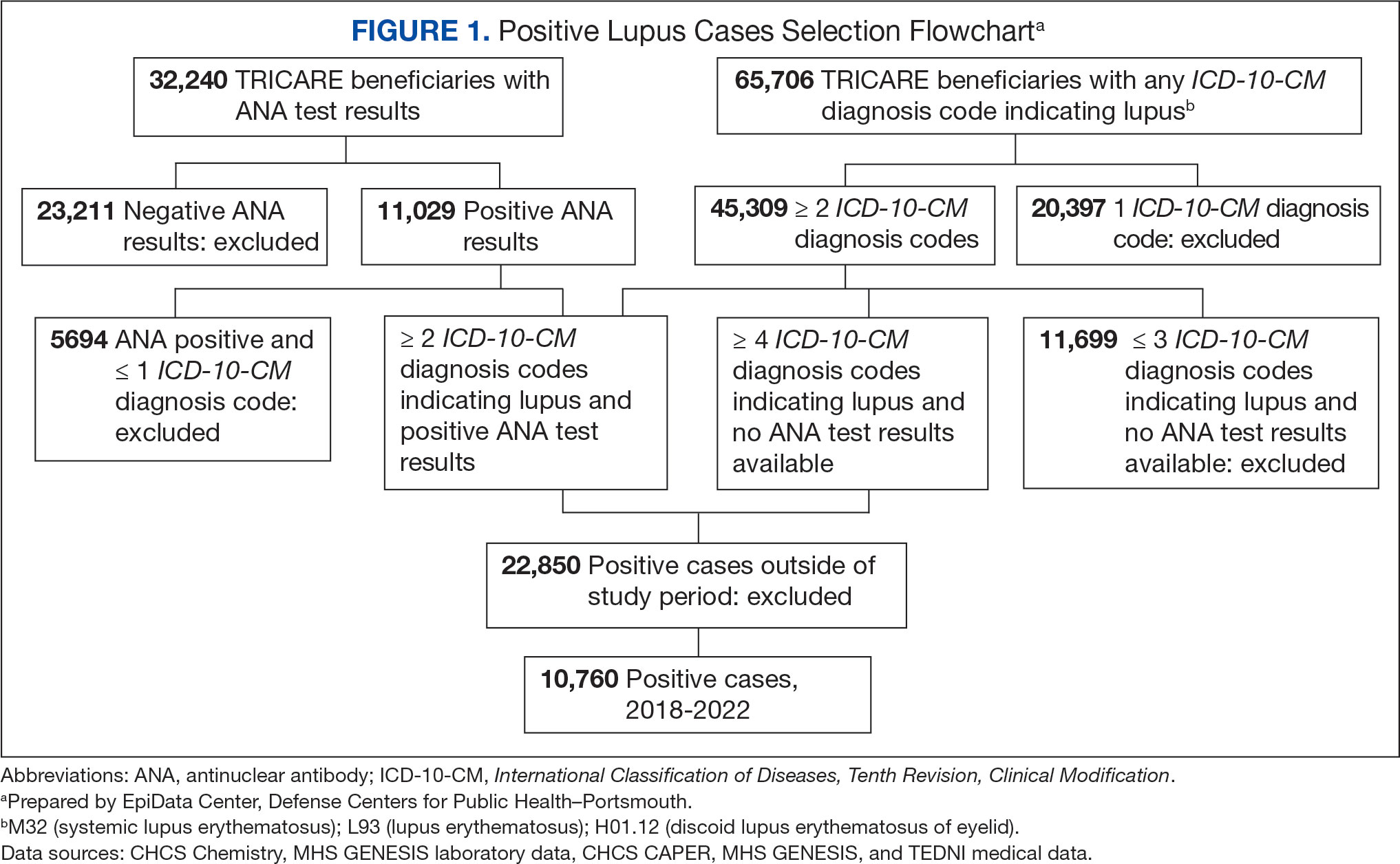

Results

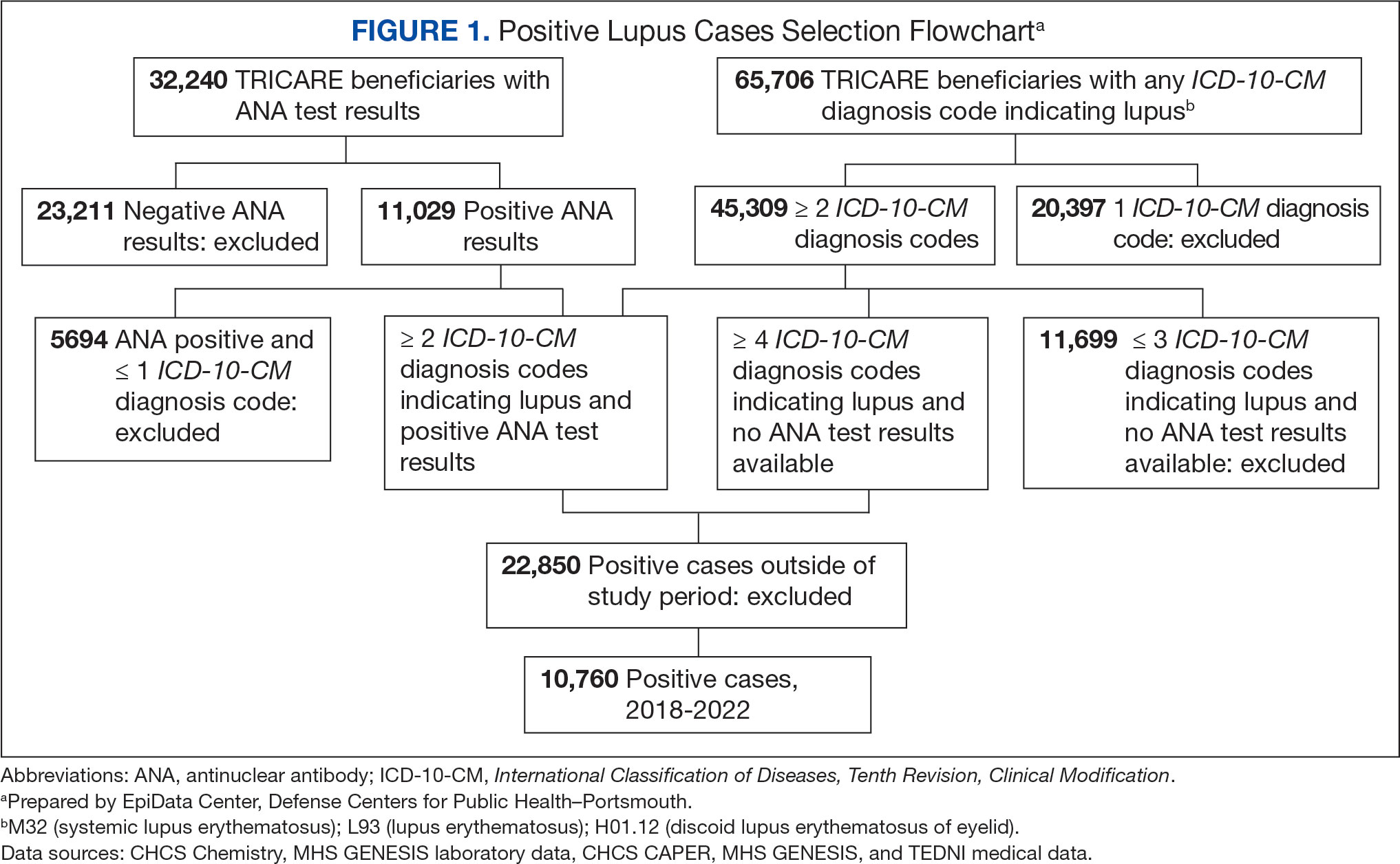

Between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2022, 99,946 TRICARE beneficiaries had some indication of lupus testing or diagnosis in their health records (Figure 1). Of these beneficiaries, 5335 had a positive ANA result and ≥ 2 ICD-10-CM lupus diagnosis codes. An additional 28,275 beneficiaries had ≥ 4 ICD-10-CM lupus diagnosis codes but no ANA test results. From these groups, the final sample included 10,760 beneficiaries who met the incident case definitions for SLE during the study period (2018 through 2022).

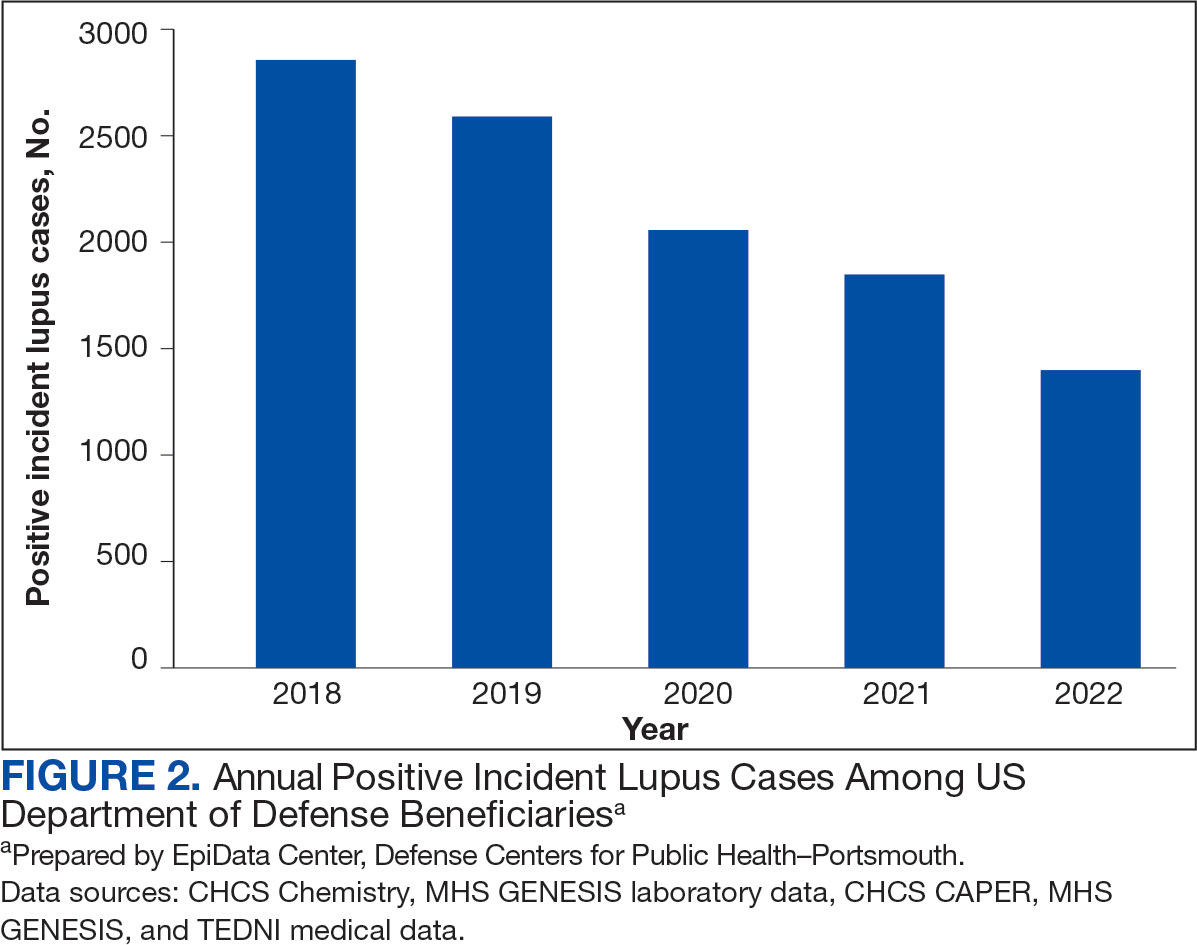

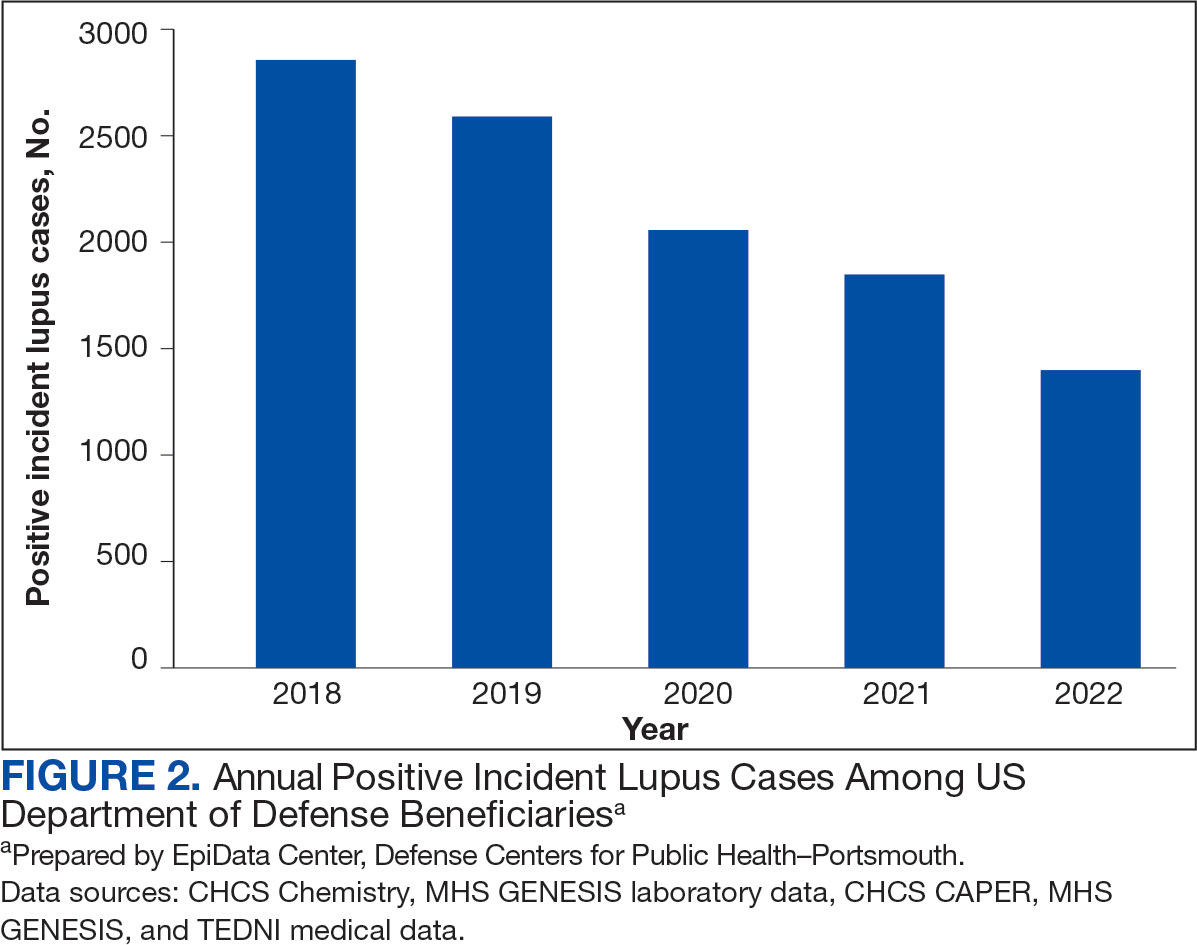

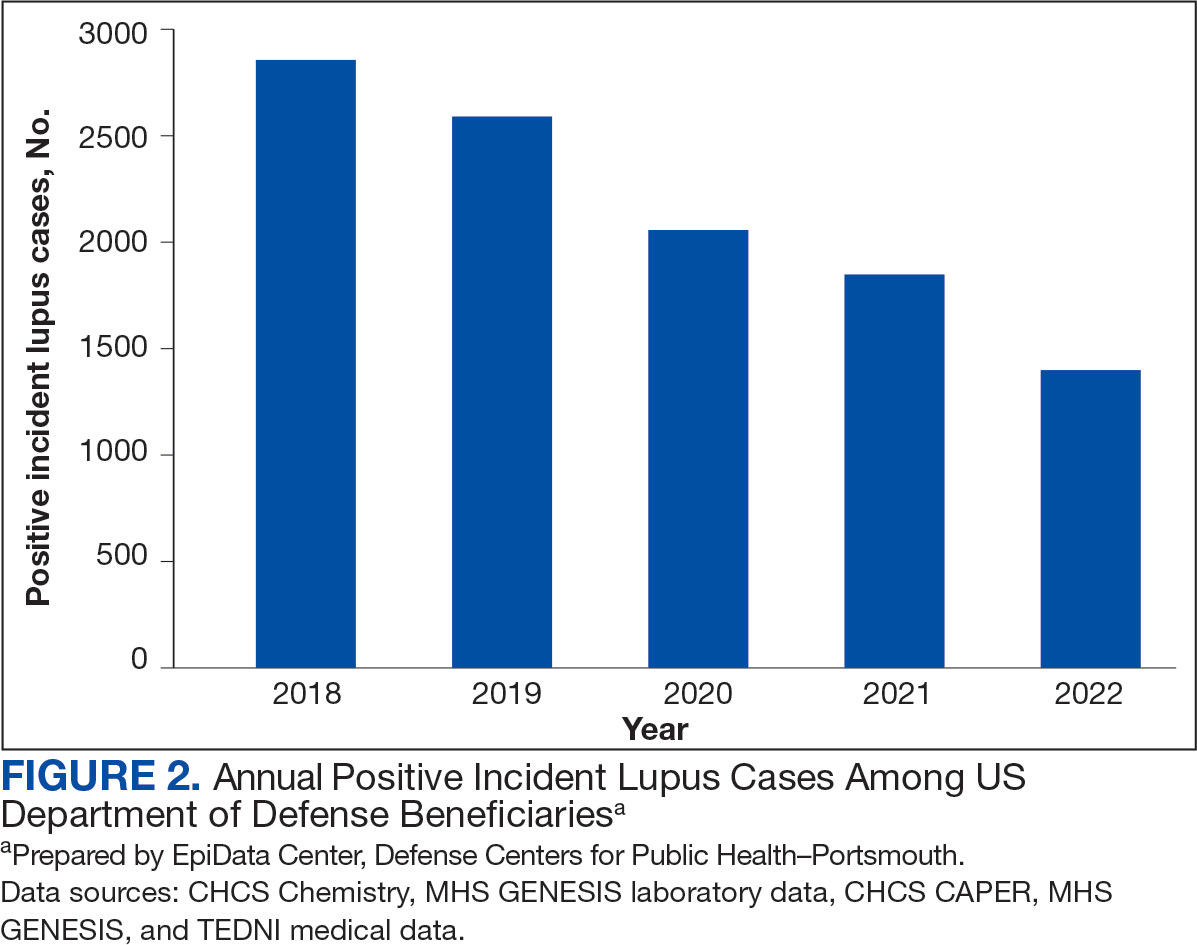

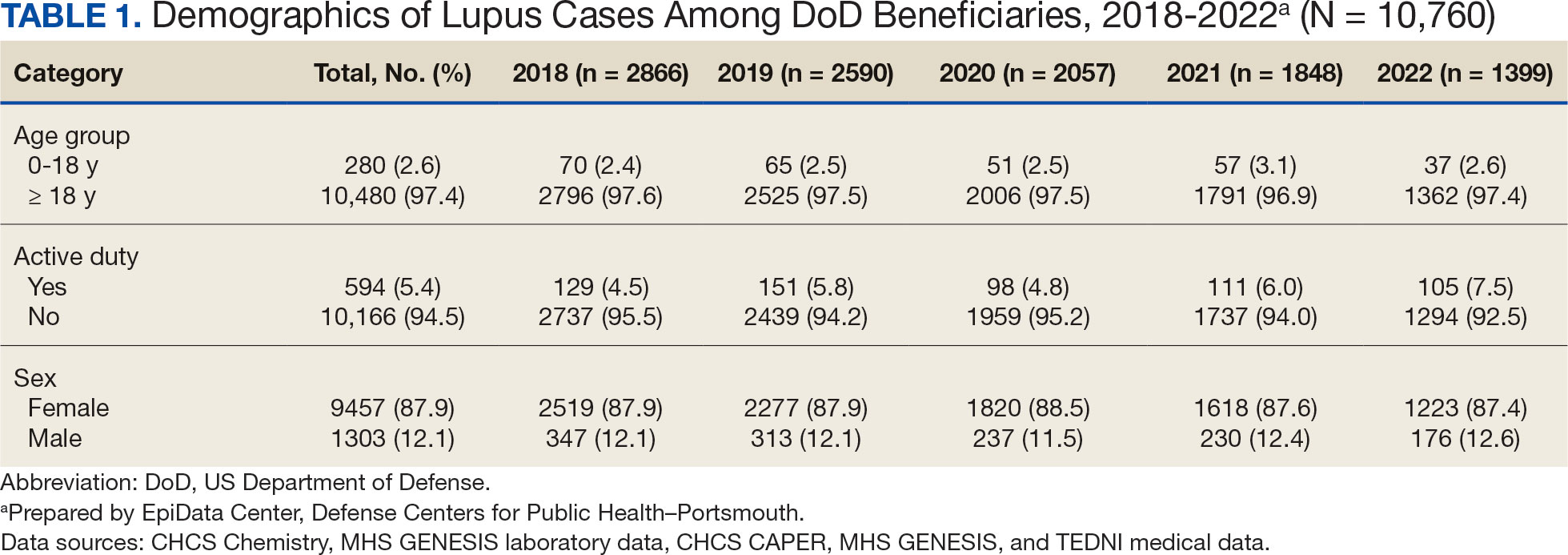

Most cases (85.1%, n = 9157) were diagnosed through TRICARE claims, while 1205 (11.2%) were diagnosed within the MHS. Another 398 (3.7%) had documentation of care both within and outside the MHS. Incident SLE cases declined by an average of 16% annually during the study period (Figure 2). This trend amounted to an overall reduction of 48.2%, from 2866 cases in 2018 to 1399 cases in 2022. This decline occurred despite total medical encounters among DoD beneficiaries remaining relatively stable during the pandemic years, with only a 3.5% change between 2018 and 2022.

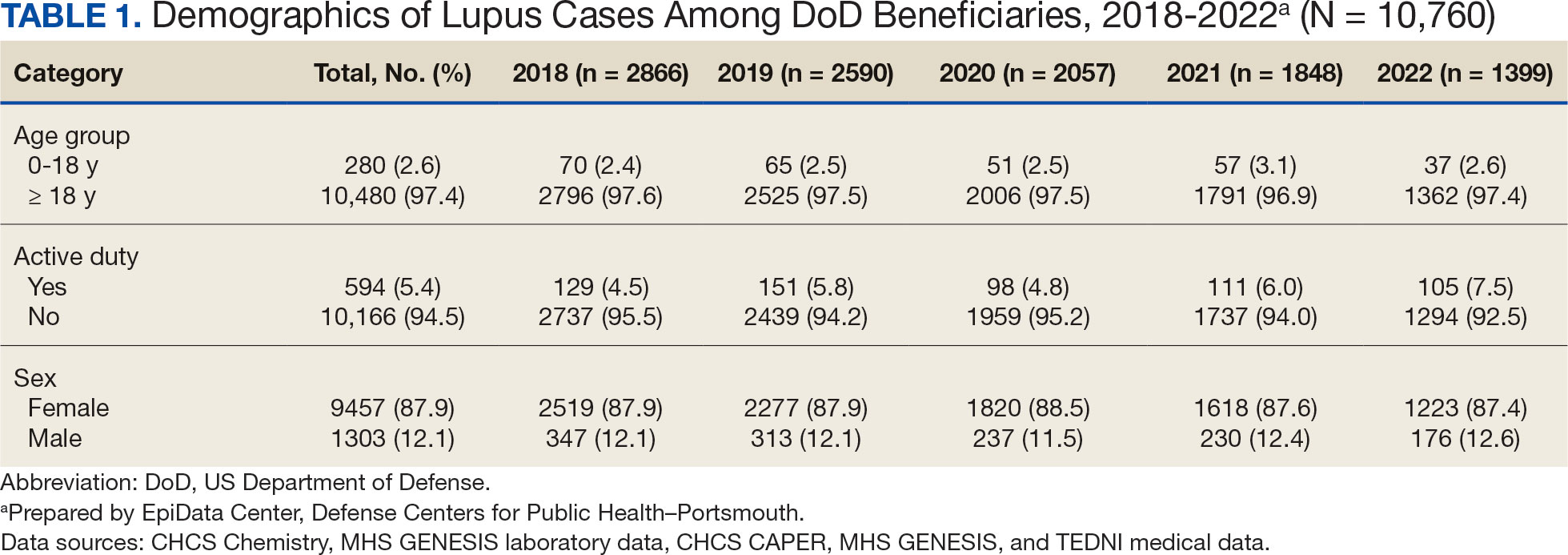

The disease was more prevalent among female beneficiaries, with a female to- male ratio of 7:1 (Table 1). Among women, the number of new cases declined from 2519 in 2018 to 1223 in 2022, while the number of cases among men remained consistently < 350 annually. Similar trends were observed across other strata. Incident SLE cases were more common among nonactive-duty beneficiaries than active-duty service members, with a ratio of 18:1. New cases among active-duty members remained < 155 per year. Age-stratified data revealed that SLE was diagnosed predominantly in individuals aged ≥ 18 years, with a ratio of 37:1 compared with individuals aged < 18 years. Among children, the number of new cases remained < 75 per year throughout the study period.

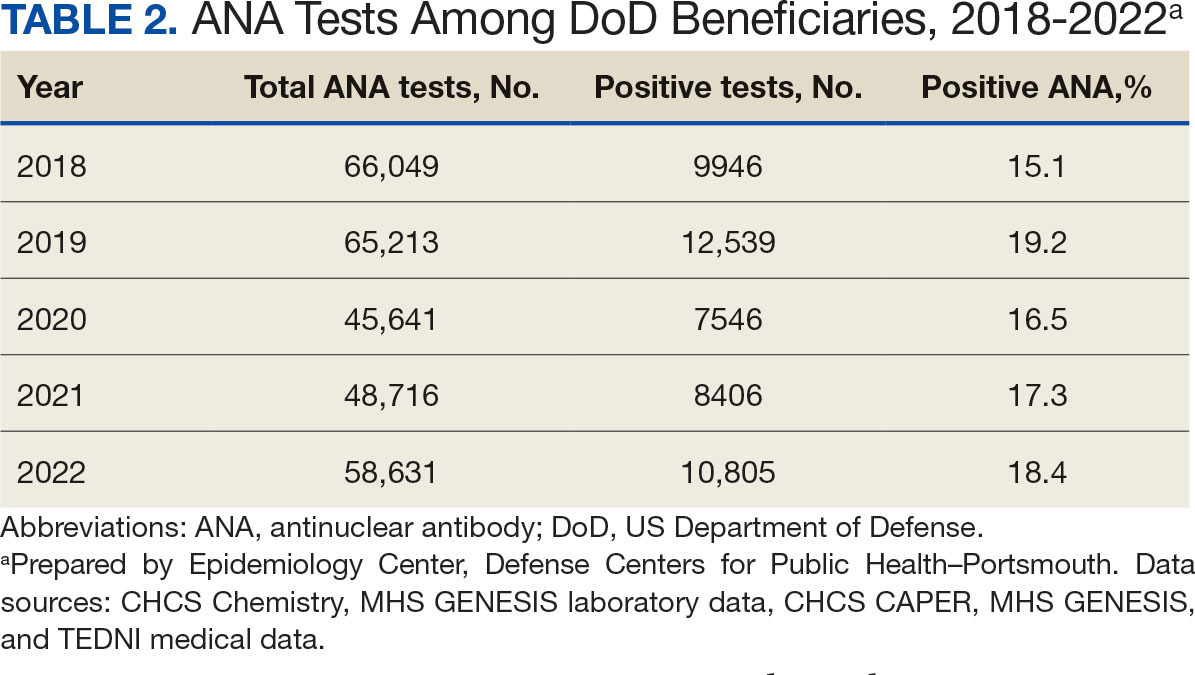

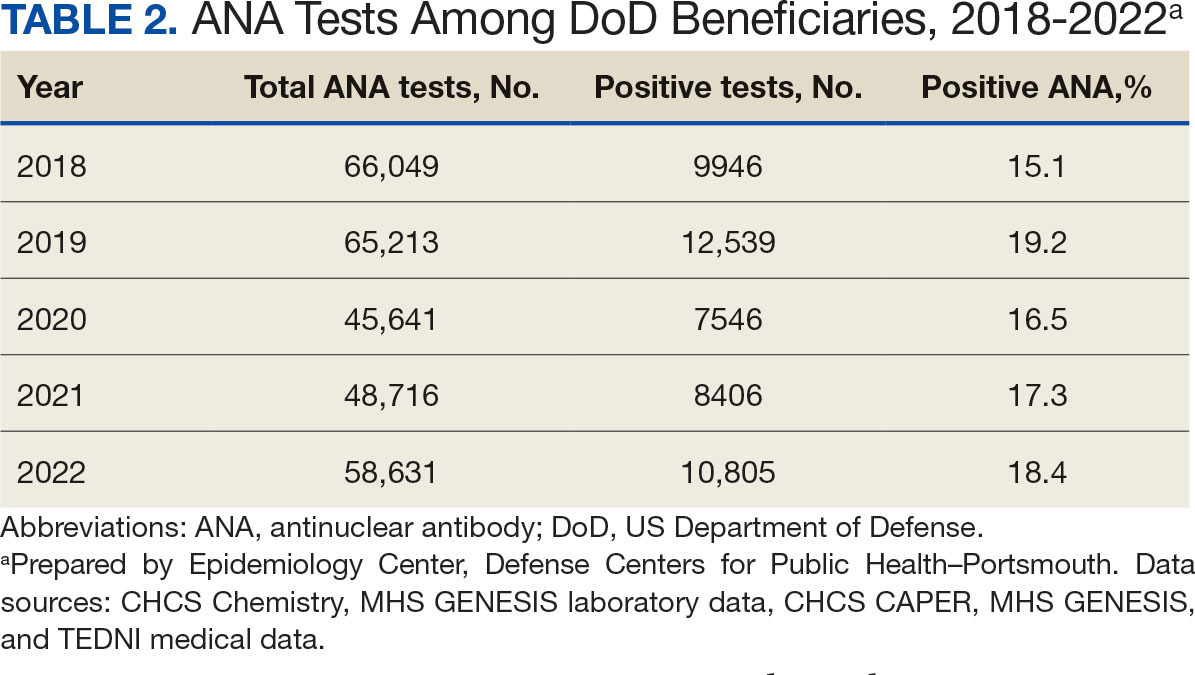

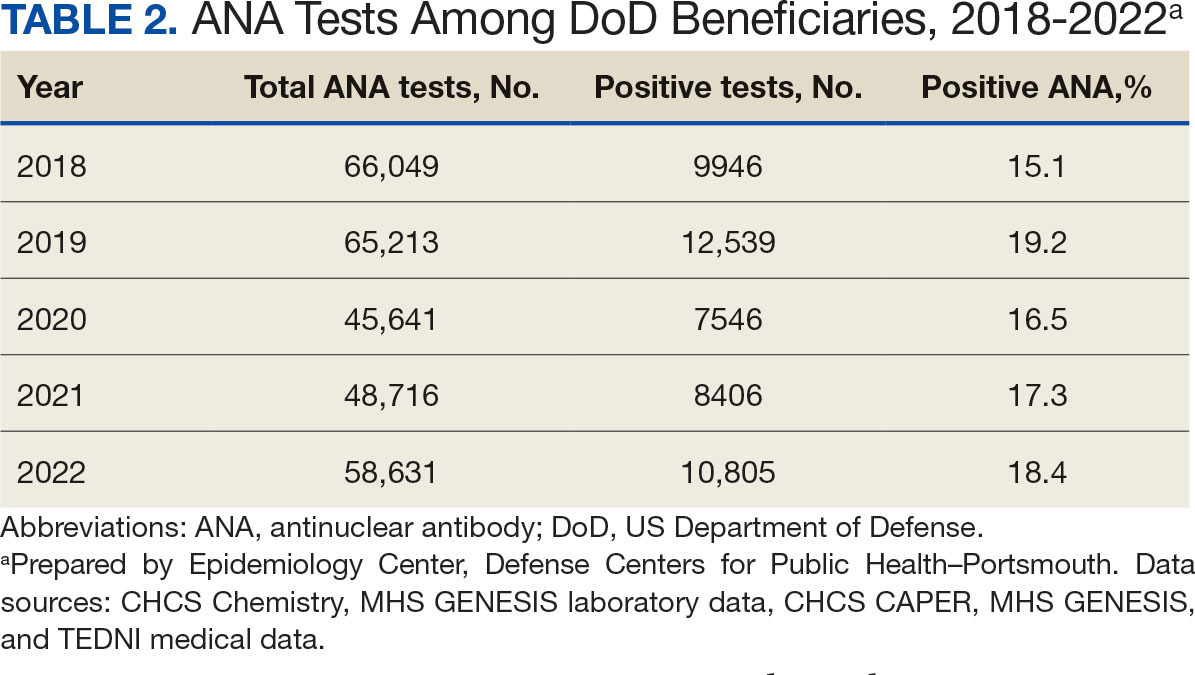

A mean 56,850 ANA tests were conducted annually in centralized laboratories using standardized protocols (Table 2). The mean ANA positivity rate was 17.3%, which remained relatively stable from 2018 through 2022.

Discussion

This study examined the annual incidence of newly diagnosed SLE cases among all TRICARE beneficiaries from January 1, 2018, through December 31, 2022, covering both before and during the peak years of the COVID-19 pandemic. This analysis revealed a steady decline in SLE cases during this period. The reliability of these findings is reinforced by the comprehensiveness of the MHS, one of the largest US health care delivery systems, which maintains near-complete medical data capture for about 9.5 million DoD TRICARE beneficiaries across domestic and international settings.

SLE is a rare autoimmune disorder that presents a diagnostic challenge due to its wide range of nonspecific symptoms, many of which resemble other conditions. To reduce the likelihood of false-positive results and ensure diagnostic accuracy, this study adopted a stringent case definition. Incident cases were identified by the presence of ANA testing in conjunction with lupus-specific ICD-10-CM codes and required ≥ 4 lupus related diagnostic entries. This criterion was necessary due to the absence of ANA test results in data from private sector care settings. Our case definition aligns with established literature. For example, a Vanderbilt University chart review study demonstrated that combining ANA positivity with ≥ 4 lupus related ICD-10-CM codes achieves a positive predictive value of 100%, albeit with a sensitivity of 45%.11 Other studies similarly affirm the diagnostic validity of using recurrent ICD-10-CM codes to improve specificity in identifying lupus cases.12,13

The primary objective of this study was to examine the temporal trend in newly diagnosed lupus cases, rather than derive precise incidence rates. Although the TRICARE system includes about 9.5 million beneficiaries, this number represents a dynamic population with continual inflow and outflow. Accurate incidence rate calculation would require access to detailed denominator data, which were not readily available. In comparison with our findings, a study limited to active-duty service members reported fewer lupus cases. This discrepancy likely reflects differences in case definitions—specifically, the absence of laboratory data, the restricted range of diagnostic codes, and the requirement that diagnoses be rendered by specialists.14 Despite these differences, demographic patterns were consistent, with higher incidence observed in females and individuals aged ≥ 20 years.

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study of lupus incidence in the general population also reported lower case counts.1 However, the CDC estimates were based on 5 state-level registries, which rely on clinician-reported cases and therefore may underestimate true disease burden. Moreover, the DoD beneficiary population differs markedly from the general population: it includes a large cohort of retirees, ensuring an older demographic; all members have comprehensive health care access; and active-duty personnel are subject to pre-enlistment medical screening. Taken together, these factors suggest this study may offer a more complete and systematically captured profile of lupus incidence.

We observed a marked decline of newly diagnosed SLE cases during the study period, which coincided with the widespread circulation of COVID-19. This decrease is unlikely to be attributable to reduced access to care during the pandemic. The MHS operates under a single-payer model, and the total number of patient encounters remained relatively stable throughout the pandemic.

To our knowledge, this is the only study to monitor lupus incidence in a large US population over the 5-year period encompassing before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, only 4 large-scale surveillance studies have addressed similar questions. 14-17 Our findings are consistent with the most recent of these reports: an analysis limited to active-duty members of the US Armed Forces identified 1127 patients with newly diagnosed lupus between 2000 and 2022 and reported stable incidence trends throughout the pandemic.14 The other 3 studies adopted a different approach, comparing the emergence of autoimmune diseases, including lupus, between individuals with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection and those without. Each of these trials concluded that COVID-19 increases the risk of various autoimmune conditions, although the findings specific to lupus were inconsistent.15-17

Chang et al reported a significant increase in new lupus diagnoses (n = 2,926,016), with an adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of 2.99 (95% CI, 2.68-3.34), spanning all ages and both sexes. The highest incidence was observed in individuals of Asian descent.15 Using German routine health care data from 2020, Tesch et al identified a heightened risk of autoimmune diseases, including lupus, among patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection (n = 641,407; 9.4% children, 57.3% female, 6.4% hospitalized), compared with matched infection-naïve controls (n = 1,560,357).16 Both studies excluded vaccinated individuals.

These 2 studies diverged in their assessment of the relationship between COVID-19 severity and subsequent autoimmune risk. Chang et al found a higher incidence among nonhospitalized ambulatory patients, while Tesch et al reported that increased risk was associated with patients requiring intensive care unit admission.15,16

In contrast, based on a cohort of 4,197,188 individuals, Peng et al found no significant difference in lupus incidence among patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection (aHR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.79-1.39).17 Notably, within the infected group, the incidence of SLE was significantly lower among vaccinated individuals compared with the unvaccinated group (aHR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.18-0.47). Similar protective associations were observed for other antibody-mediated autoimmune disorders, including pemphigoid, Graves’ disease, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

Limitations

Due to fundamental differences in study design, we were unable to directly reconcile our findings with those reported in the literature. This study lacked access to reliable documentation of COVID-19 infection status, primarily due to the widespread use of home testing among TRICARE beneficiaries. Additionally, the dataset did not include inpatient records and therefore did not permit evaluation of disease severity. Despite these constraints, it is plausible that the overall burden of COVID-19 infection within the study population was lower than that observed in the general US population.

As of December 2022, the DoD had reported about 750,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases among military personnel, civilian employees, dependents, and DoD contractors.18 Given that TRICARE beneficiaries represent about 2.8% of the total US population—and that > 90 million US individuals were infected between 2020 and 2022—the implied infection rate in our cohort appears to be about one-third of what might be expected.19 This discrepancy may be due to higher adherence to mitigation measures, such as social distancing and mask usage, among DoD-affiliated populations. COVID-19 vaccination was mandated for all active-duty service members, who constitute 5.4% of the study population. The remaining TRICARE beneficiaries also had access to guaranteed health care and vaccination coverage, likely contributing to high overall vaccination rates.

Because > 80% of the study population was composed of individuals from diverse civilian backgrounds, we expect the distribution of infection severity within the DoD beneficiary population to approximate that of the general US population.

Future Directions

The findings of this study offer circumstantial yet real-time evidence of the complexity underlying immune dysregulation at the intersection of host susceptibility and environmental exposures. The stability in ANA positivity rates during the study period mitigates concerns regarding undiagnosed subclinical lupus and may suggest that, overall, immune homeostasis was preserved among DoD beneficiaries.

It is noteworthy that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence of several common infections—such as influenza and EBV—declined markedly, likely as a result of widespread social distancing and other public health interventions.20 Mitigation strategies implemented within the military may have conferred protection not only against COVID-19 but also against other community-acquired pathogens.

In light of these observations, we hypothesize that for COVID-19 to act as a trigger for SLE, a prolonged or repeated disruption of immune equilibrium may be required—potentially mediated by recurrent infections or sustained inflammatory states. The association between viral infections and autoimmunity is well established. Immune dysregulation leading to autoantibody production has been observed not only in the context of SARS-CoV-2 but also following infections with EBV, cytomegalovirus, enteroviruses, hepatitis B and C viruses, HIV, and parvovirus B19.21

This dysregulation is often transient, accompanied by compensatory immune regulatory responses. However, in individuals subjected to successive or overlapping infections, these regulatory mechanisms may become compromised or overwhelmed, due to emergent patterns of immune interference of varying severity. In such cases, a transient immune perturbation may progress into a bona fide autoimmune disease, contingent upon individual risk factors such as genetic predisposition, preexisting immune memory, and regenerative capacity.21

Therefore, we believe the significance of this study is 2-fold. First, lupus is known to develop gradually and may require 3 to 5 years to clinically manifest after the initial break in immunological tolerance.3 Continued public health surveillance represents a more pragmatic strategy than retrospective cohort construction, especially as histories of COVID-19 infection become increasingly complete and definitive. Our findings provide a valuable baseline reference point for future longitudinal studies.

The interpretation of surveillance outcomes—whether indicating an upward trend, a stable baseline, or a downward trend—offers distinct analytical value. Within this study population, we observed neither an upward trajectory that might suggest a direct causal link, nor a flat trend that would imply absence of association between COVID-19 and lupus pathogenesis. Instead, the observation of a downward trend invites consideration of nonlinear or protective influences. From this perspective, we recommend that future investigations adopt a holistic framework when assessing environmental contributions to immune dysregulation—particularly when evaluating the long-term immunopathological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on lupus and related autoimmune conditions.

Conclusions

This study identified a declining trend in incident lupus cases during the COVID-19 pandemic among the DoD beneficiary population. Further investigation is warranted to elucidate the underlying factors contributing to this decline. Conducting longitudinal epidemiologic studies and applying multivariable regression analyses will be essential to determine whether incidence rates revert to prepandemic baselines and how these trends may be influenced by evolving environmental factors within the general population.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or lupus, is a rare autoimmune disease estimated to occur in about 5.1 cases per 100,000 person-years in the United States in 2018.1 The disease predominantly affects females, with an incidence of 8.7 cases per 100,000 person-years vs 1.2 cases per 100,000 person-years in males, and is most common in patients aged 15 to 44 years.1,2

Lupus presents with a constellation of clinical signs and symptoms that evolve, along with hallmark laboratory findings indicative of immune dysregulation and polyclonal B-cell activation. Consequently, a wide array of autoantibodies may be produced, although the combination of epitope specificity can vary from patient to patient.3 Nevertheless, > 98% of individuals diagnosed with lupus produce antinuclear antibodies (ANA), making ANA positivity a near-universal serologic feature at the time of diagnosis.