User login

Atypical Intrathoracic Manifestations of Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Case Series

Atypical Intrathoracic Manifestations of Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Case Series

Prostate cancer is the most common noncutaneous cancer in men, accounting for 29% of all incident cancer cases.1 Typically, prostate cancer metastasizes to bone and regional lymph nodes.2 However, intrathoracic manifestation may occur. This report presents 3 cases of rare intrathoracic manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer with a review of the current literature.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

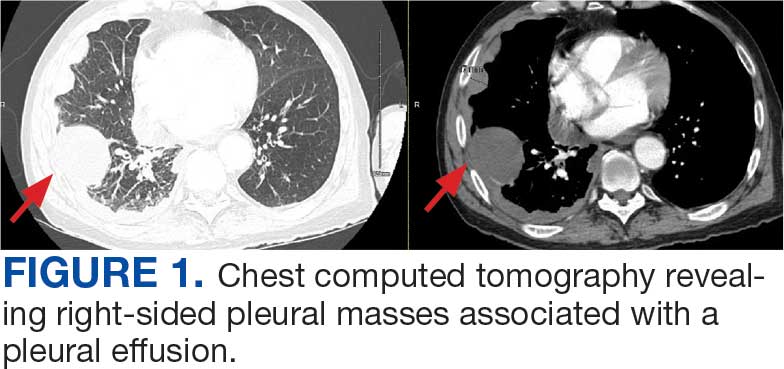

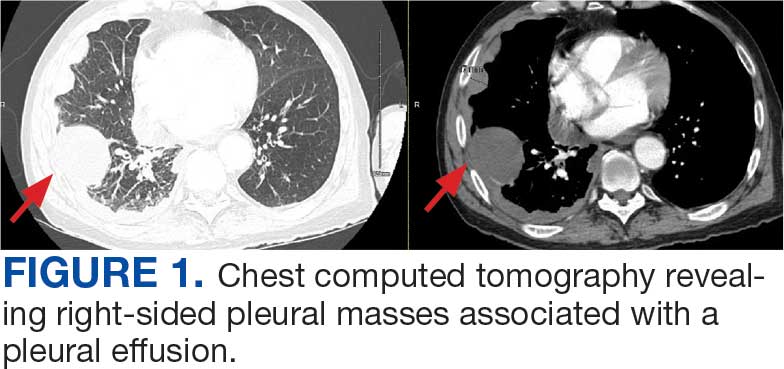

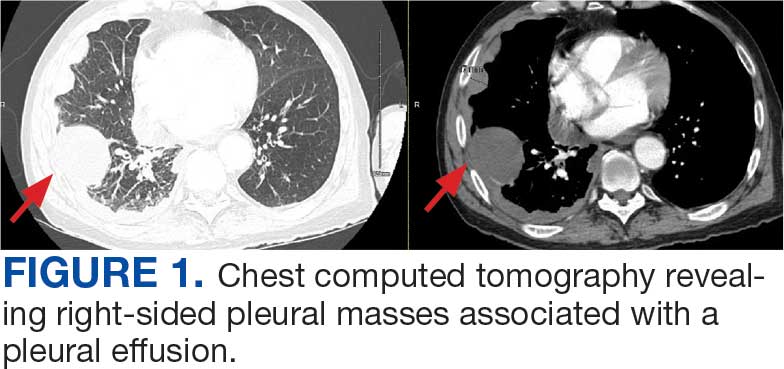

A 71-year-old male who was an active smoker and a long-standing employment as a plumber was diagnosed with rectal cancer in 2022. He completed neoadjuvant capecitabine and radiation therapy followed by a rectosigmoidectomy. Several weeks after surgery, the patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with a dry cough and worsening shortness of breath. Point-of-care ultrasound of the lungs revealed a moderate right pleural effusion with several nodular pleural masses. A chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed these findings (Figure 1). A CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed prostatomegaly with the medial lobe of the prostate protruding into the bladder; however, no enlarged retroperitoneal, mesenteric or pelvic lymph nodes were noted. The patient underwent a right pleural fluid drainage and pleural mass biopsy. Pleural mass histomorphology as well as immunohistochemical (IHC) stains were consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. The pleural fluid cytology also was consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma.

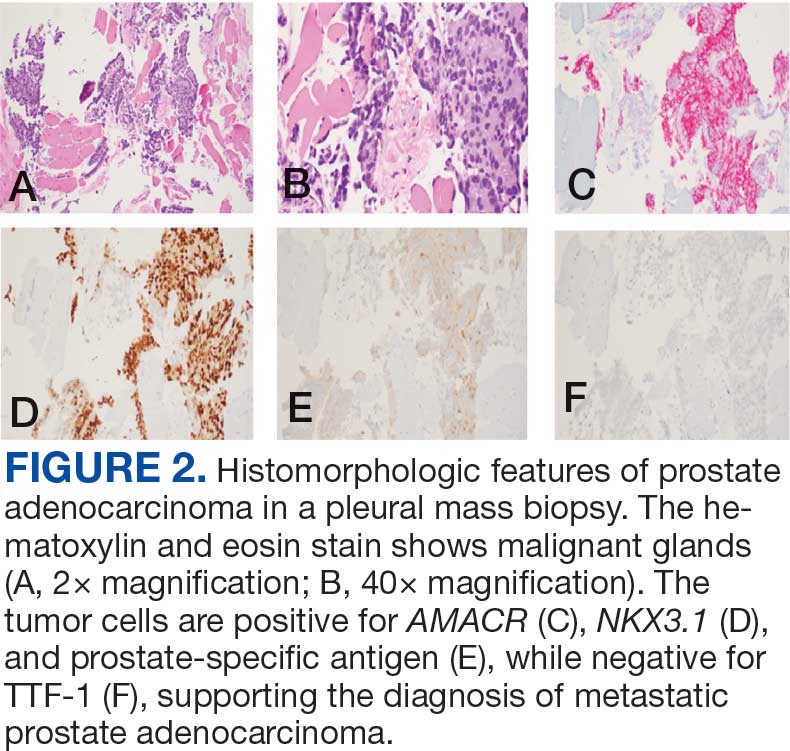

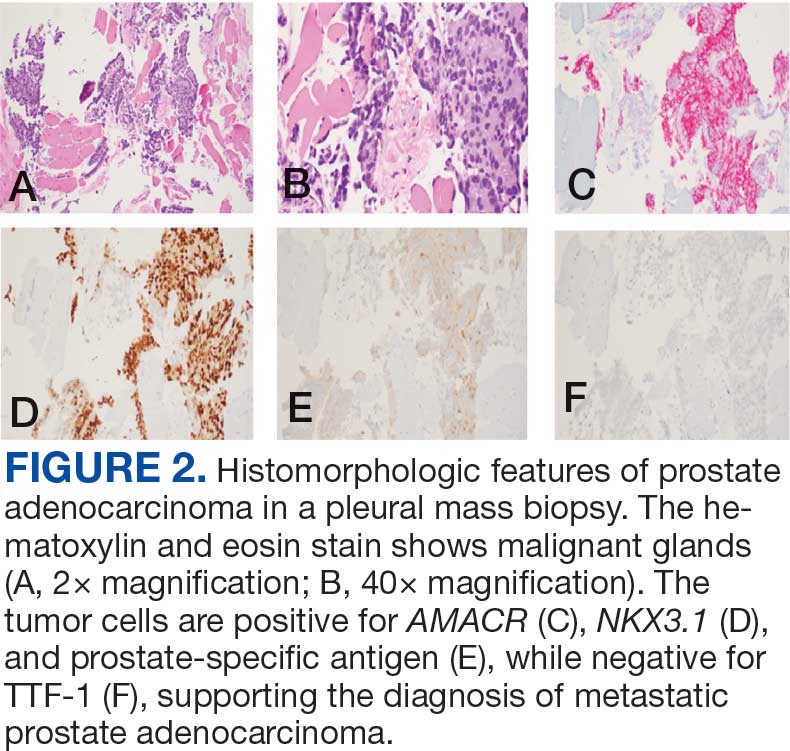

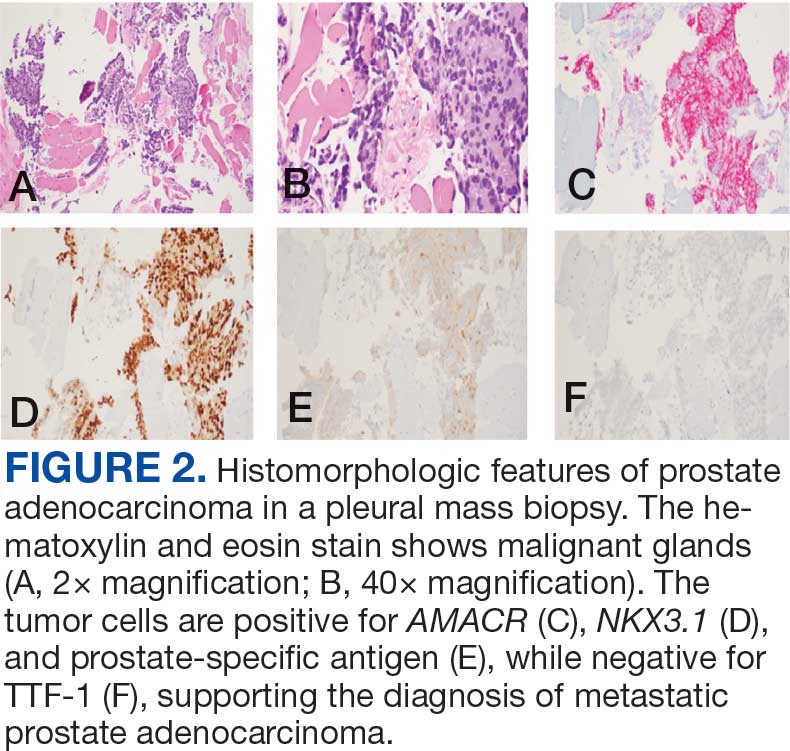

Immunohistochemistry showed weak positive staining for prostate-specific NK3 homeobox 1 gene (NKX3.1), alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase gene (AMACR), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), keratin-20, and caudal type homeobox 2 gene (CDX2) (Figure 2) 2). The patient's prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was found to be elevated at 33.9 ng/mL (reference range, < 4 ng/mL).

Case 2

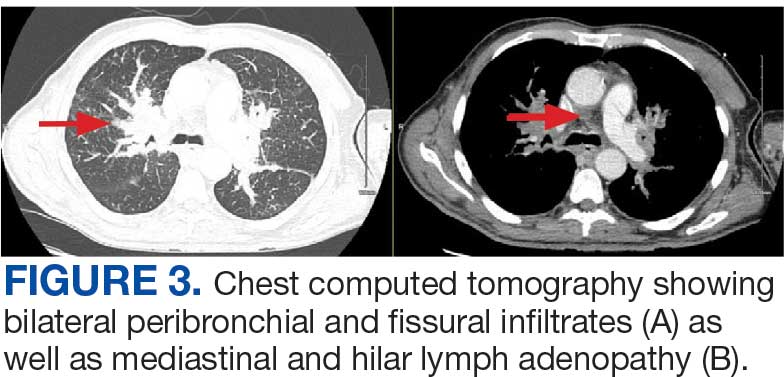

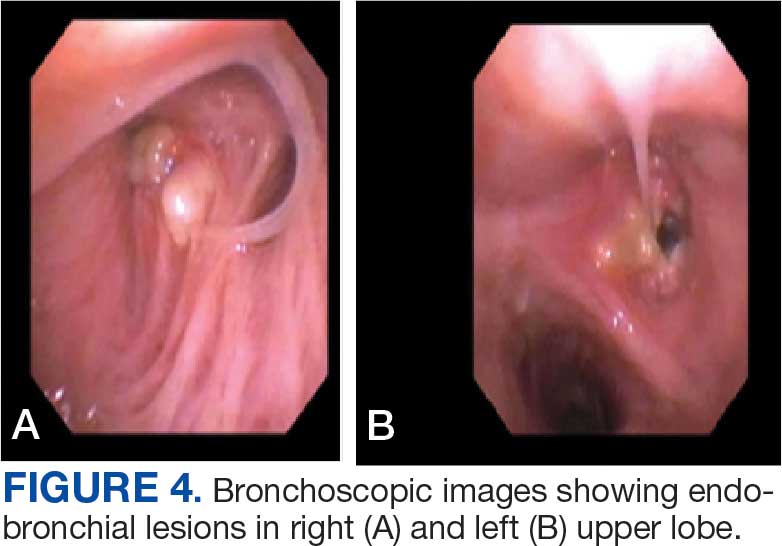

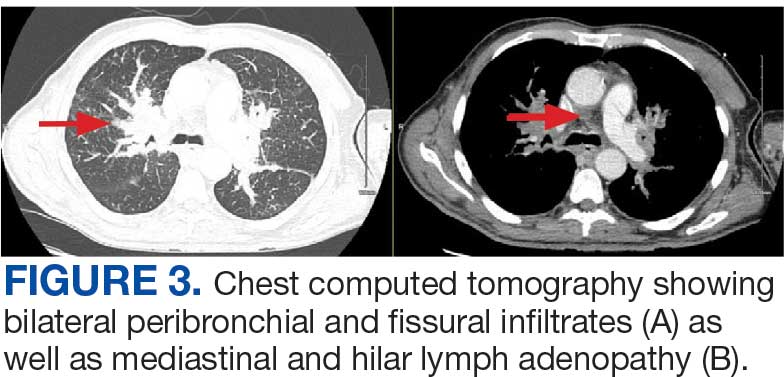

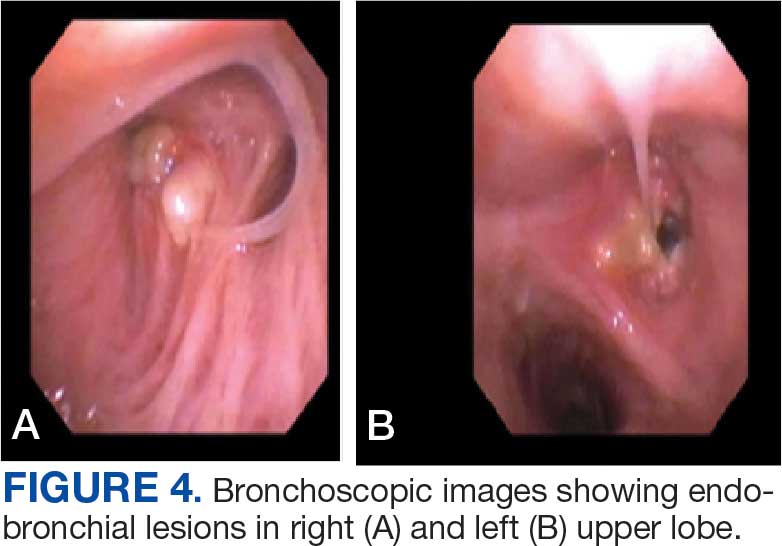

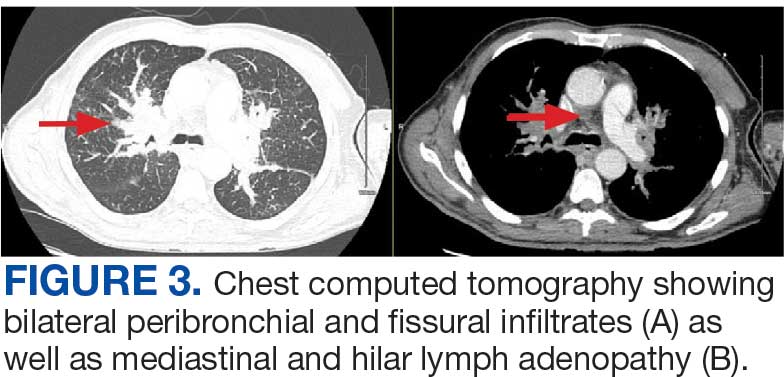

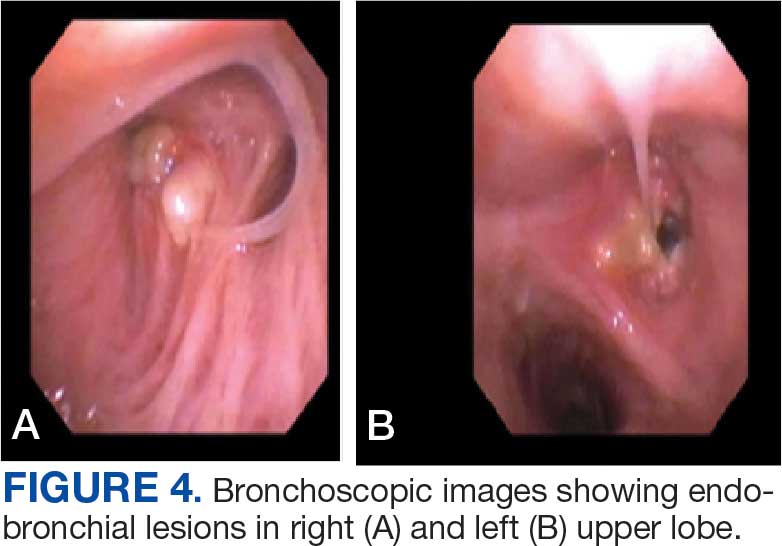

A 71-year-old male with a history of alcohol use disorder and a 30-year smoking history presented to the ED with worsening dyspnea on exertion. The patient’s baseline exercise tolerance decreased to walking for only 1 block. He reported unintentional weight loss of about 30 pounds over the prior year, no recent respiratory infections, no prior breathing problems, and no personal or family history of cancer. Chest CT revealed findings of bilateral peribronchial opacities as well as mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy (Figure 3). The patient developed hypoxic respiratory failure necessitating intubation, mechanical ventilation, and management in the medical intensive care unit, where he was treated for postobstructive pneumonia. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed endobronchial lesions in the right and left upper lobe that were partially obstructing the airway (Figure 4).

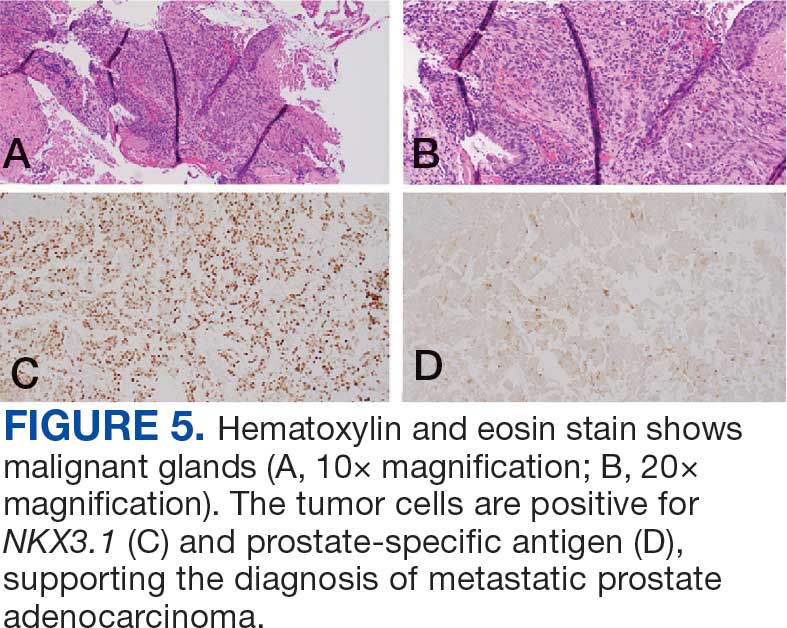

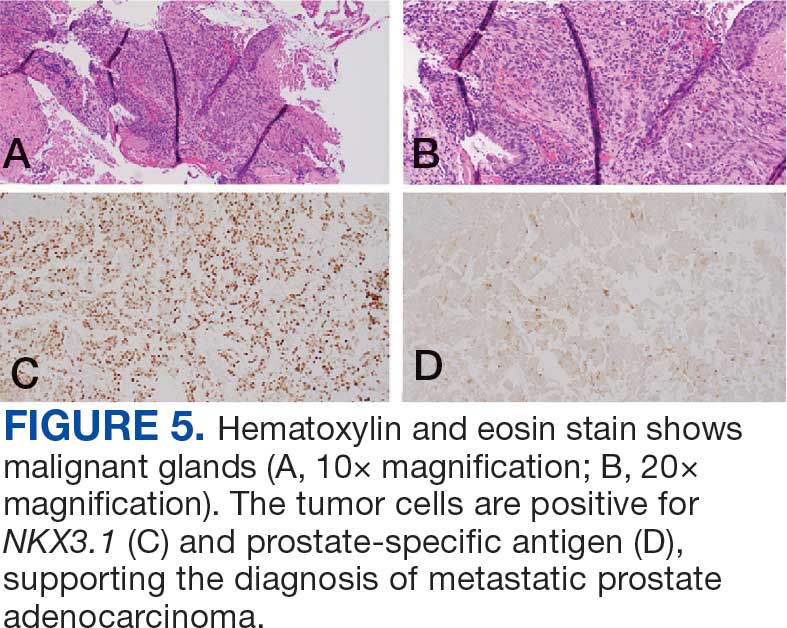

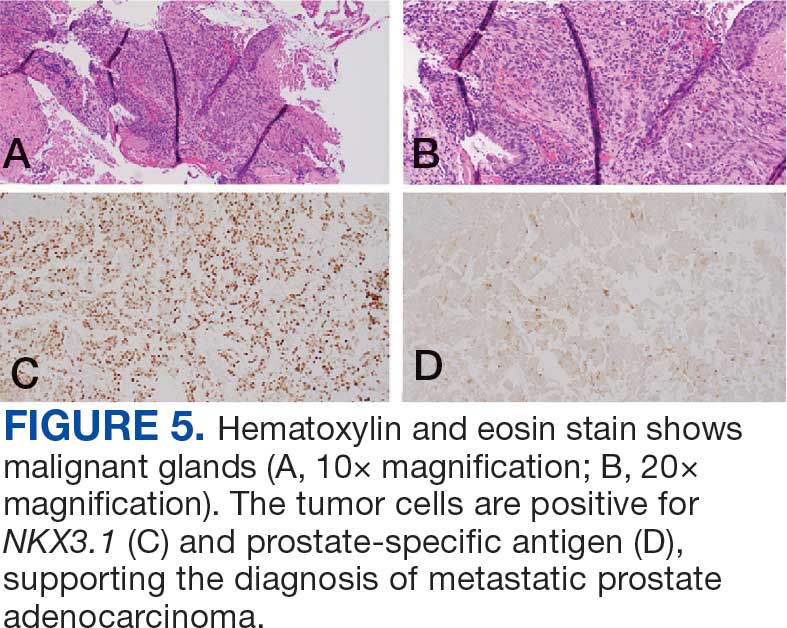

The endobronchial masses were debulked using forceps, and samples were sent for surgical pathology evaluation. Staging was completed using linear endobronchial ultrasound, which revealed an enlarged subcarinal lymph node (S7). The surgical pathology of the endobronchial mass and the subcarinal lymph node cytology were consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate. The tumor cells were positive for AE1/AE3, PSA, and NKX3.1, but were negative for CK7 and TTF-1 (Figure 5). Further imaging revealed an enlarged heterogeneous prostate gland, prominent pelvic nodes, and left retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, as well as sclerotic foci within the T10 vertebral body and right inferior pubic ramus. PSA was also found to be significantly elevated at 700 ng/mL.

Case 3

An 80-year-old male veteran with a history of prostate cancer and recently diagnosed T2N1M0 head and neck squamous cell carcinoma was referred to the Pulmonary service for evaluation of a pulmonary nodule. His medical history was notable for prostate cancer diagnosed 12 years earlier, with an unknown Gleason score. Initial treatment included prostatectomy followed by whole pelvic radiation therapy a year after, due to elevated PSA in surveillance monitoring. This treatment led to remission. After establishing remission for > 10 years, the patient was started on low-dose testosterone replacement therapy to address complications of radiation therapy, namely hypogonadism.

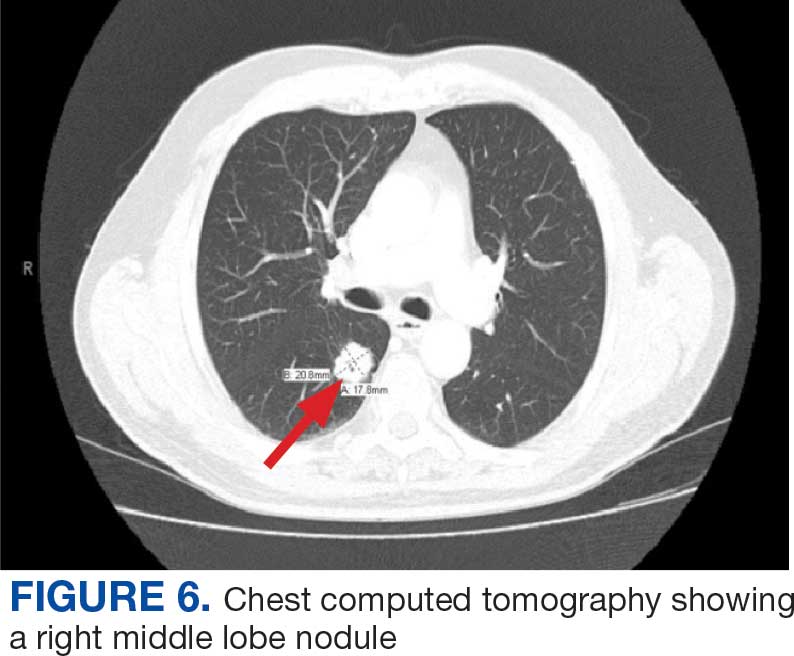

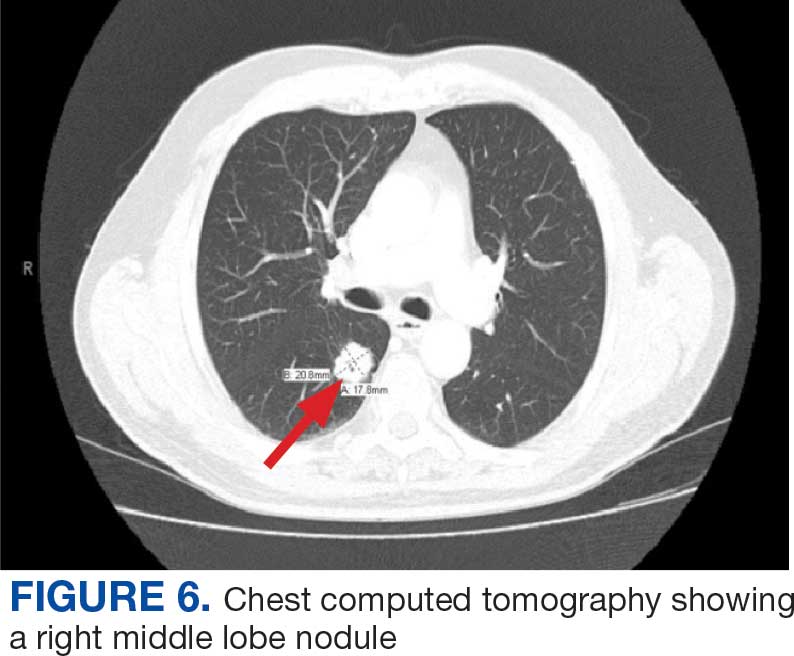

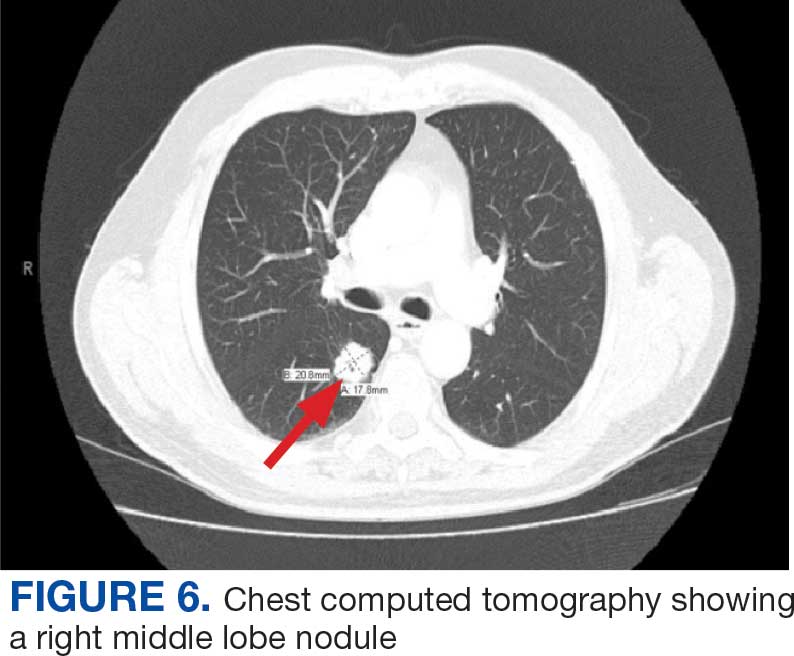

On evaluation, a chest CT was significant for a large 2-cm right middle lobe nodule (Figure 6). At that time, PSA was noted to be borderline elevated at 4.2 ng/mL, and whole-body imaging did not reveal any lesions elsewhere, specifically no bone metastasis. Biopsies of the right middle lobe lung nodule revealed adenocarcinoma consistent with metastatic prostate cancer. Testosterone therapy was promptly discontinued.

The patient initially refused androgen deprivation therapy owing to the antiandrogenic adverse effects. However, subsequent chest CTs revealed growing lung nodules, which convinced him to proceed with androgen deprivation therapy followed by palliative radiation, and chemotherapy and management of malignant pleural effusion with indwelling small bore pleural catheter for about 10 years. He died from COVID-19 during the pandemic.

DISCUSSION

These cases highlight the importance of including prostate cancer in the differential diagnoses of male patients with intrathoracic abnormalities, even in the absence of metastasis to the more common sites. In a large cohort study of 74,826 patients with metastatic prostate cancer, Gandaglia et al found that the most frequent sites of metastasis were bone (84.0%) and distant lymph nodes (10.6%).2 However, thoracic involvement was observed in 9.1% of cases, with isolated thoracic metastasis being rare. The cases described in this report exemplify exceptionally uncommon occurrences within that 9.1%.

Pleural metastases, as observed in Case 1, are a particularly rare manifestation. In a 10-year retrospective assessment, Vinjamoori et al discovered pleural nodules or masses in only 6 of 82 patients (7.3%) with atypical metastases.3 Adrenal and liver metastases accounted for 15% and 37% of cases with atypical distribution. As such, isolated pleural disease is rare even in atypical presentations.3

As seen in Case 2, endobronchial metastases producing airway obstruction are also rare, with the most common primary cancers associated with endobronchial metastasis being breast, colon, and renal cancer.4 The available literature on this presentation is confined to case reports. Hameed et al reported a case of synchronous biopsy-proven endobronchial metastasis from prostate cancer.5 These cases highlight the importance of maintaining a high level of clinical awareness when encountering endobronchial lesions in patients with prostate cancer.

Case 3 presents a unique situation of lung metastases without any involvement of the bones. It is well known—and was confirmed by Heidenreich et al—that lung metastases in prostate adenocarcinoma usually coincide with extensive osseous disease.6 This instance highlights the importance of watchful monitoring for unusual patterns of cancer recurrence.

Immunohistochemistry stains that are specific to prostate cancer include antibodies against PSA. Prostate-specific membrane antigen is another marker that is far more present in malignant than in benign prostate tissue.

The NKX3.1 gene encodes a homeobox protein, which is a transcription factor and tumor suppressor. In prostate cancer, there is loss of heterozygosity of the gene and stains for the IHC antibody to NKX3.1.7

On the other hand, lung cells stain positive for TTF-1, which is produced by surfactant-producing type 2 pneumocytes and club cells in the lung. Antibodies to TTF-1, a common IHC stain, are used to identify adenocarcinoma of lung origin and may carry a prognostic value.7

The immunohistochemistry profiles, specifically the presence of prostate-specific markers such as PSA and NKX3.1, played a vital role in making the diagnosis.

In Case 1, weak TTF-1 positivity was noted, an unusual finding in metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Marak et al documented a rare case of TTF-1–positive metastatic prostate cancer, illustrating the potential for diagnostic confusion with primary lung malignancies.8

The 3 cases described in this report demonstrate the importance of clinical consideration, serial follow-up of PSA levels, using more prostate-specific positron emission tomography tracers (eg, Pylarify) alongside traditional imaging, and tissue biopsy to detect unusual metastases.

CONCLUSIONS

Although thoracic metastases from prostate cancer are rare, these presentations highlight the importance of clinical awareness regarding atypical cases. Pleural disease, endobronchial lesions, and isolated pulmonary nodules might be the first clinical manifestation of metastatic prostate cancer. A high index of suspicion, appropriate imaging, and judicious use of immunohistochemistry are important to ensure accurate diagnosis and optimal patient management.

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12-49. doi:10.3322/caac.21820

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74(2):210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Vinjamoori AH, Jagannathan JP, Shinagare AB, et al. Atypical metastases from prostate cancer: 10-year experience at a single institution. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(2):367-372. doi:10.2214/AJR.11.7533

- Salud A, Porcel JM, Rovirosa A, Bellmunt J. Endobronchial metastatic disease: analysis of 32 cases. J Surg Oncol. 1996;62(4):249-252. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096- 9098(199608)62:4<249::AID-JSO4>3.0.CO;2-6

- Hameed M, Haq IU, Yousaf M, Hussein M, Rashid U, Al-Bozom I. Endobronchial metastases secondary to prostate cancer: a case report and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020;32:101326. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101326

- Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al; for the European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration- resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65(2):467- 479. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.002

- Schallenberg S, Dernbach G, Dragomir MP, et al. TTF-1 status in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma is an independent predictor of relapse and survival superior to tumor grading. Eur J Cancer. 2024;197:113474. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113474

- Marak C, Guddati AK, Ashraf A, Smith J, Kaushik P. Prostate adenocarcinoma with atypical immunohistochemistry presenting with a Cheerio sign. AIM Clinical Cases. 2023;1:e220508. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0508

Prostate cancer is the most common noncutaneous cancer in men, accounting for 29% of all incident cancer cases.1 Typically, prostate cancer metastasizes to bone and regional lymph nodes.2 However, intrathoracic manifestation may occur. This report presents 3 cases of rare intrathoracic manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer with a review of the current literature.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

A 71-year-old male who was an active smoker and a long-standing employment as a plumber was diagnosed with rectal cancer in 2022. He completed neoadjuvant capecitabine and radiation therapy followed by a rectosigmoidectomy. Several weeks after surgery, the patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with a dry cough and worsening shortness of breath. Point-of-care ultrasound of the lungs revealed a moderate right pleural effusion with several nodular pleural masses. A chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed these findings (Figure 1). A CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed prostatomegaly with the medial lobe of the prostate protruding into the bladder; however, no enlarged retroperitoneal, mesenteric or pelvic lymph nodes were noted. The patient underwent a right pleural fluid drainage and pleural mass biopsy. Pleural mass histomorphology as well as immunohistochemical (IHC) stains were consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. The pleural fluid cytology also was consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma.

Immunohistochemistry showed weak positive staining for prostate-specific NK3 homeobox 1 gene (NKX3.1), alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase gene (AMACR), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), keratin-20, and caudal type homeobox 2 gene (CDX2) (Figure 2) 2). The patient's prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was found to be elevated at 33.9 ng/mL (reference range, < 4 ng/mL).

Case 2

A 71-year-old male with a history of alcohol use disorder and a 30-year smoking history presented to the ED with worsening dyspnea on exertion. The patient’s baseline exercise tolerance decreased to walking for only 1 block. He reported unintentional weight loss of about 30 pounds over the prior year, no recent respiratory infections, no prior breathing problems, and no personal or family history of cancer. Chest CT revealed findings of bilateral peribronchial opacities as well as mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy (Figure 3). The patient developed hypoxic respiratory failure necessitating intubation, mechanical ventilation, and management in the medical intensive care unit, where he was treated for postobstructive pneumonia. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed endobronchial lesions in the right and left upper lobe that were partially obstructing the airway (Figure 4).

The endobronchial masses were debulked using forceps, and samples were sent for surgical pathology evaluation. Staging was completed using linear endobronchial ultrasound, which revealed an enlarged subcarinal lymph node (S7). The surgical pathology of the endobronchial mass and the subcarinal lymph node cytology were consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate. The tumor cells were positive for AE1/AE3, PSA, and NKX3.1, but were negative for CK7 and TTF-1 (Figure 5). Further imaging revealed an enlarged heterogeneous prostate gland, prominent pelvic nodes, and left retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, as well as sclerotic foci within the T10 vertebral body and right inferior pubic ramus. PSA was also found to be significantly elevated at 700 ng/mL.

Case 3

An 80-year-old male veteran with a history of prostate cancer and recently diagnosed T2N1M0 head and neck squamous cell carcinoma was referred to the Pulmonary service for evaluation of a pulmonary nodule. His medical history was notable for prostate cancer diagnosed 12 years earlier, with an unknown Gleason score. Initial treatment included prostatectomy followed by whole pelvic radiation therapy a year after, due to elevated PSA in surveillance monitoring. This treatment led to remission. After establishing remission for > 10 years, the patient was started on low-dose testosterone replacement therapy to address complications of radiation therapy, namely hypogonadism.

On evaluation, a chest CT was significant for a large 2-cm right middle lobe nodule (Figure 6). At that time, PSA was noted to be borderline elevated at 4.2 ng/mL, and whole-body imaging did not reveal any lesions elsewhere, specifically no bone metastasis. Biopsies of the right middle lobe lung nodule revealed adenocarcinoma consistent with metastatic prostate cancer. Testosterone therapy was promptly discontinued.

The patient initially refused androgen deprivation therapy owing to the antiandrogenic adverse effects. However, subsequent chest CTs revealed growing lung nodules, which convinced him to proceed with androgen deprivation therapy followed by palliative radiation, and chemotherapy and management of malignant pleural effusion with indwelling small bore pleural catheter for about 10 years. He died from COVID-19 during the pandemic.

DISCUSSION

These cases highlight the importance of including prostate cancer in the differential diagnoses of male patients with intrathoracic abnormalities, even in the absence of metastasis to the more common sites. In a large cohort study of 74,826 patients with metastatic prostate cancer, Gandaglia et al found that the most frequent sites of metastasis were bone (84.0%) and distant lymph nodes (10.6%).2 However, thoracic involvement was observed in 9.1% of cases, with isolated thoracic metastasis being rare. The cases described in this report exemplify exceptionally uncommon occurrences within that 9.1%.

Pleural metastases, as observed in Case 1, are a particularly rare manifestation. In a 10-year retrospective assessment, Vinjamoori et al discovered pleural nodules or masses in only 6 of 82 patients (7.3%) with atypical metastases.3 Adrenal and liver metastases accounted for 15% and 37% of cases with atypical distribution. As such, isolated pleural disease is rare even in atypical presentations.3

As seen in Case 2, endobronchial metastases producing airway obstruction are also rare, with the most common primary cancers associated with endobronchial metastasis being breast, colon, and renal cancer.4 The available literature on this presentation is confined to case reports. Hameed et al reported a case of synchronous biopsy-proven endobronchial metastasis from prostate cancer.5 These cases highlight the importance of maintaining a high level of clinical awareness when encountering endobronchial lesions in patients with prostate cancer.

Case 3 presents a unique situation of lung metastases without any involvement of the bones. It is well known—and was confirmed by Heidenreich et al—that lung metastases in prostate adenocarcinoma usually coincide with extensive osseous disease.6 This instance highlights the importance of watchful monitoring for unusual patterns of cancer recurrence.

Immunohistochemistry stains that are specific to prostate cancer include antibodies against PSA. Prostate-specific membrane antigen is another marker that is far more present in malignant than in benign prostate tissue.

The NKX3.1 gene encodes a homeobox protein, which is a transcription factor and tumor suppressor. In prostate cancer, there is loss of heterozygosity of the gene and stains for the IHC antibody to NKX3.1.7

On the other hand, lung cells stain positive for TTF-1, which is produced by surfactant-producing type 2 pneumocytes and club cells in the lung. Antibodies to TTF-1, a common IHC stain, are used to identify adenocarcinoma of lung origin and may carry a prognostic value.7

The immunohistochemistry profiles, specifically the presence of prostate-specific markers such as PSA and NKX3.1, played a vital role in making the diagnosis.

In Case 1, weak TTF-1 positivity was noted, an unusual finding in metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Marak et al documented a rare case of TTF-1–positive metastatic prostate cancer, illustrating the potential for diagnostic confusion with primary lung malignancies.8

The 3 cases described in this report demonstrate the importance of clinical consideration, serial follow-up of PSA levels, using more prostate-specific positron emission tomography tracers (eg, Pylarify) alongside traditional imaging, and tissue biopsy to detect unusual metastases.

CONCLUSIONS

Although thoracic metastases from prostate cancer are rare, these presentations highlight the importance of clinical awareness regarding atypical cases. Pleural disease, endobronchial lesions, and isolated pulmonary nodules might be the first clinical manifestation of metastatic prostate cancer. A high index of suspicion, appropriate imaging, and judicious use of immunohistochemistry are important to ensure accurate diagnosis and optimal patient management.

Prostate cancer is the most common noncutaneous cancer in men, accounting for 29% of all incident cancer cases.1 Typically, prostate cancer metastasizes to bone and regional lymph nodes.2 However, intrathoracic manifestation may occur. This report presents 3 cases of rare intrathoracic manifestations of metastatic prostate cancer with a review of the current literature.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

A 71-year-old male who was an active smoker and a long-standing employment as a plumber was diagnosed with rectal cancer in 2022. He completed neoadjuvant capecitabine and radiation therapy followed by a rectosigmoidectomy. Several weeks after surgery, the patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with a dry cough and worsening shortness of breath. Point-of-care ultrasound of the lungs revealed a moderate right pleural effusion with several nodular pleural masses. A chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed these findings (Figure 1). A CT of the abdomen and pelvis revealed prostatomegaly with the medial lobe of the prostate protruding into the bladder; however, no enlarged retroperitoneal, mesenteric or pelvic lymph nodes were noted. The patient underwent a right pleural fluid drainage and pleural mass biopsy. Pleural mass histomorphology as well as immunohistochemical (IHC) stains were consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. The pleural fluid cytology also was consistent with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma.

Immunohistochemistry showed weak positive staining for prostate-specific NK3 homeobox 1 gene (NKX3.1), alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase gene (AMACR), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), and prosaposin, and negative transcription termination factor (TTF-1), keratin-7 (CK7), keratin-20, and caudal type homeobox 2 gene (CDX2) (Figure 2) 2). The patient's prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was found to be elevated at 33.9 ng/mL (reference range, < 4 ng/mL).

Case 2

A 71-year-old male with a history of alcohol use disorder and a 30-year smoking history presented to the ED with worsening dyspnea on exertion. The patient’s baseline exercise tolerance decreased to walking for only 1 block. He reported unintentional weight loss of about 30 pounds over the prior year, no recent respiratory infections, no prior breathing problems, and no personal or family history of cancer. Chest CT revealed findings of bilateral peribronchial opacities as well as mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy (Figure 3). The patient developed hypoxic respiratory failure necessitating intubation, mechanical ventilation, and management in the medical intensive care unit, where he was treated for postobstructive pneumonia. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed endobronchial lesions in the right and left upper lobe that were partially obstructing the airway (Figure 4).

The endobronchial masses were debulked using forceps, and samples were sent for surgical pathology evaluation. Staging was completed using linear endobronchial ultrasound, which revealed an enlarged subcarinal lymph node (S7). The surgical pathology of the endobronchial mass and the subcarinal lymph node cytology were consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate. The tumor cells were positive for AE1/AE3, PSA, and NKX3.1, but were negative for CK7 and TTF-1 (Figure 5). Further imaging revealed an enlarged heterogeneous prostate gland, prominent pelvic nodes, and left retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, as well as sclerotic foci within the T10 vertebral body and right inferior pubic ramus. PSA was also found to be significantly elevated at 700 ng/mL.

Case 3

An 80-year-old male veteran with a history of prostate cancer and recently diagnosed T2N1M0 head and neck squamous cell carcinoma was referred to the Pulmonary service for evaluation of a pulmonary nodule. His medical history was notable for prostate cancer diagnosed 12 years earlier, with an unknown Gleason score. Initial treatment included prostatectomy followed by whole pelvic radiation therapy a year after, due to elevated PSA in surveillance monitoring. This treatment led to remission. After establishing remission for > 10 years, the patient was started on low-dose testosterone replacement therapy to address complications of radiation therapy, namely hypogonadism.

On evaluation, a chest CT was significant for a large 2-cm right middle lobe nodule (Figure 6). At that time, PSA was noted to be borderline elevated at 4.2 ng/mL, and whole-body imaging did not reveal any lesions elsewhere, specifically no bone metastasis. Biopsies of the right middle lobe lung nodule revealed adenocarcinoma consistent with metastatic prostate cancer. Testosterone therapy was promptly discontinued.

The patient initially refused androgen deprivation therapy owing to the antiandrogenic adverse effects. However, subsequent chest CTs revealed growing lung nodules, which convinced him to proceed with androgen deprivation therapy followed by palliative radiation, and chemotherapy and management of malignant pleural effusion with indwelling small bore pleural catheter for about 10 years. He died from COVID-19 during the pandemic.

DISCUSSION

These cases highlight the importance of including prostate cancer in the differential diagnoses of male patients with intrathoracic abnormalities, even in the absence of metastasis to the more common sites. In a large cohort study of 74,826 patients with metastatic prostate cancer, Gandaglia et al found that the most frequent sites of metastasis were bone (84.0%) and distant lymph nodes (10.6%).2 However, thoracic involvement was observed in 9.1% of cases, with isolated thoracic metastasis being rare. The cases described in this report exemplify exceptionally uncommon occurrences within that 9.1%.

Pleural metastases, as observed in Case 1, are a particularly rare manifestation. In a 10-year retrospective assessment, Vinjamoori et al discovered pleural nodules or masses in only 6 of 82 patients (7.3%) with atypical metastases.3 Adrenal and liver metastases accounted for 15% and 37% of cases with atypical distribution. As such, isolated pleural disease is rare even in atypical presentations.3

As seen in Case 2, endobronchial metastases producing airway obstruction are also rare, with the most common primary cancers associated with endobronchial metastasis being breast, colon, and renal cancer.4 The available literature on this presentation is confined to case reports. Hameed et al reported a case of synchronous biopsy-proven endobronchial metastasis from prostate cancer.5 These cases highlight the importance of maintaining a high level of clinical awareness when encountering endobronchial lesions in patients with prostate cancer.

Case 3 presents a unique situation of lung metastases without any involvement of the bones. It is well known—and was confirmed by Heidenreich et al—that lung metastases in prostate adenocarcinoma usually coincide with extensive osseous disease.6 This instance highlights the importance of watchful monitoring for unusual patterns of cancer recurrence.

Immunohistochemistry stains that are specific to prostate cancer include antibodies against PSA. Prostate-specific membrane antigen is another marker that is far more present in malignant than in benign prostate tissue.

The NKX3.1 gene encodes a homeobox protein, which is a transcription factor and tumor suppressor. In prostate cancer, there is loss of heterozygosity of the gene and stains for the IHC antibody to NKX3.1.7

On the other hand, lung cells stain positive for TTF-1, which is produced by surfactant-producing type 2 pneumocytes and club cells in the lung. Antibodies to TTF-1, a common IHC stain, are used to identify adenocarcinoma of lung origin and may carry a prognostic value.7

The immunohistochemistry profiles, specifically the presence of prostate-specific markers such as PSA and NKX3.1, played a vital role in making the diagnosis.

In Case 1, weak TTF-1 positivity was noted, an unusual finding in metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma. Marak et al documented a rare case of TTF-1–positive metastatic prostate cancer, illustrating the potential for diagnostic confusion with primary lung malignancies.8

The 3 cases described in this report demonstrate the importance of clinical consideration, serial follow-up of PSA levels, using more prostate-specific positron emission tomography tracers (eg, Pylarify) alongside traditional imaging, and tissue biopsy to detect unusual metastases.

CONCLUSIONS

Although thoracic metastases from prostate cancer are rare, these presentations highlight the importance of clinical awareness regarding atypical cases. Pleural disease, endobronchial lesions, and isolated pulmonary nodules might be the first clinical manifestation of metastatic prostate cancer. A high index of suspicion, appropriate imaging, and judicious use of immunohistochemistry are important to ensure accurate diagnosis and optimal patient management.

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12-49. doi:10.3322/caac.21820

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74(2):210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Vinjamoori AH, Jagannathan JP, Shinagare AB, et al. Atypical metastases from prostate cancer: 10-year experience at a single institution. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(2):367-372. doi:10.2214/AJR.11.7533

- Salud A, Porcel JM, Rovirosa A, Bellmunt J. Endobronchial metastatic disease: analysis of 32 cases. J Surg Oncol. 1996;62(4):249-252. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096- 9098(199608)62:4<249::AID-JSO4>3.0.CO;2-6

- Hameed M, Haq IU, Yousaf M, Hussein M, Rashid U, Al-Bozom I. Endobronchial metastases secondary to prostate cancer: a case report and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020;32:101326. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101326

- Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al; for the European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration- resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65(2):467- 479. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.002

- Schallenberg S, Dernbach G, Dragomir MP, et al. TTF-1 status in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma is an independent predictor of relapse and survival superior to tumor grading. Eur J Cancer. 2024;197:113474. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113474

- Marak C, Guddati AK, Ashraf A, Smith J, Kaushik P. Prostate adenocarcinoma with atypical immunohistochemistry presenting with a Cheerio sign. AIM Clinical Cases. 2023;1:e220508. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0508

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12-49. doi:10.3322/caac.21820

- Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74(2):210-216. doi:10.1002/pros.22742

- Vinjamoori AH, Jagannathan JP, Shinagare AB, et al. Atypical metastases from prostate cancer: 10-year experience at a single institution. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(2):367-372. doi:10.2214/AJR.11.7533

- Salud A, Porcel JM, Rovirosa A, Bellmunt J. Endobronchial metastatic disease: analysis of 32 cases. J Surg Oncol. 1996;62(4):249-252. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096- 9098(199608)62:4<249::AID-JSO4>3.0.CO;2-6

- Hameed M, Haq IU, Yousaf M, Hussein M, Rashid U, Al-Bozom I. Endobronchial metastases secondary to prostate cancer: a case report and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020;32:101326. doi:10.1016/j.rmcr.2020.101326

- Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, et al; for the European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration- resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65(2):467- 479. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.002

- Schallenberg S, Dernbach G, Dragomir MP, et al. TTF-1 status in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma is an independent predictor of relapse and survival superior to tumor grading. Eur J Cancer. 2024;197:113474. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113474

- Marak C, Guddati AK, Ashraf A, Smith J, Kaushik P. Prostate adenocarcinoma with atypical immunohistochemistry presenting with a Cheerio sign. AIM Clinical Cases. 2023;1:e220508. doi:10.7326/aimcc.2022.0508

Atypical Intrathoracic Manifestations of Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Case Series

Atypical Intrathoracic Manifestations of Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Case Series