User login

Biotin interference a concern in hormonal assays

Biotin supplementation showed signs of interference with biotinylated assays in a crossover trial.

The proposed benefits of biotin (vitamin B7), including stimulating hair growth and assisting in the treatment of various forms of diabetes, have made it a popular supplement. Supplementation generally leads to artificially high levels of biotin, which was shown to cause inaccurate results in biotinylated assays, according to Danni Li, PhD, of the advanced research and diagnostic laboratory at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and her colleagues.

They analyzed the results of both biotinylated and nonbiotinylated assays of six patients – two women and four men – who ingested 10 mg/day of biotin supplement for 7 days. Two blood samples were obtained in the course of the study: one prior to starting biotin supplementation as a baseline and one a week ofter biotin supplementation had ended. The assays tested the presence of nine hormones and two nonhormones using multiple diagnostic systems to run the assays. In total, 37 immunoassays were conducted on each sample (JAMA. 2017;318[12]:1150-60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13705).

Two immunoassay testing techniques were used in the diagnostic assays. The sandwich technique was used in testing TSH, parathyroid hormone (PTH), prolactin, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), PSA, and ferritin and competitive technique was used in testing total T4, total T3, free T4, free T3, and 25-OHD. In assays utilizing competitive techniques, false highs were reported in three Roche cobas e602 machines and one Siemens Vista Dimension 1500 machine.

Assays utilizing the sandwich technique experienced false decreases in TSH, PTH, and NT-proBNP when compared with baseline measurements in Roche cobas e602 and OCD Vitros 5600 machines. A predominance of the falsely low results were present in the assays conducted by the OCD Vitros machine, with significant changes from baseline measurements. TSH experienced a 94% decrease of 1.67 mIU/L, PTH experienced a 61% decrease of 25.8 pg/mL, and NT-proBNP falsely decreased by more than 13.9 pg/mL. In Roche cobas e602 assays, TSH levels were falsely low and measurements decreased by 0.72 mIU/L (37%) when compared with baseline measurements.

Biotin did not interfere in all biotinylated assays and was only observed in 9 of the 23 (39%) of the assays conducted. Specifically, 4 of 15 (27%) sandwich immunoassays were falsely decreased while five of eight (63%) competitive binding assays were falsely increased.

“Among the 23 biotinylated assays studied, biotin interference was of greatest clinical significance in the OCD Vitros TSH assay, where falsely decreased TSH concentrations (to less than 0.15 mU/L) could have resulted in misdiagnosis of thyrotoxicosis in otherwise euthyroid individuals,” according to Dr. Li and her associates, “Likewise, falsely decreased OCD Vitros NT-proBNP, to lower than assay detection limits, could possibly result in failure to identify congestive heart failure.”

One investigator received funding and nonfinanical support from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, one reported receiving financial support from Abbott Laboratories, and another reported receiving personal fees from Roche and Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Li and the other researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

Biotin supplementation showed signs of interference with biotinylated assays in a crossover trial.

The proposed benefits of biotin (vitamin B7), including stimulating hair growth and assisting in the treatment of various forms of diabetes, have made it a popular supplement. Supplementation generally leads to artificially high levels of biotin, which was shown to cause inaccurate results in biotinylated assays, according to Danni Li, PhD, of the advanced research and diagnostic laboratory at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and her colleagues.

They analyzed the results of both biotinylated and nonbiotinylated assays of six patients – two women and four men – who ingested 10 mg/day of biotin supplement for 7 days. Two blood samples were obtained in the course of the study: one prior to starting biotin supplementation as a baseline and one a week ofter biotin supplementation had ended. The assays tested the presence of nine hormones and two nonhormones using multiple diagnostic systems to run the assays. In total, 37 immunoassays were conducted on each sample (JAMA. 2017;318[12]:1150-60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13705).

Two immunoassay testing techniques were used in the diagnostic assays. The sandwich technique was used in testing TSH, parathyroid hormone (PTH), prolactin, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), PSA, and ferritin and competitive technique was used in testing total T4, total T3, free T4, free T3, and 25-OHD. In assays utilizing competitive techniques, false highs were reported in three Roche cobas e602 machines and one Siemens Vista Dimension 1500 machine.

Assays utilizing the sandwich technique experienced false decreases in TSH, PTH, and NT-proBNP when compared with baseline measurements in Roche cobas e602 and OCD Vitros 5600 machines. A predominance of the falsely low results were present in the assays conducted by the OCD Vitros machine, with significant changes from baseline measurements. TSH experienced a 94% decrease of 1.67 mIU/L, PTH experienced a 61% decrease of 25.8 pg/mL, and NT-proBNP falsely decreased by more than 13.9 pg/mL. In Roche cobas e602 assays, TSH levels were falsely low and measurements decreased by 0.72 mIU/L (37%) when compared with baseline measurements.

Biotin did not interfere in all biotinylated assays and was only observed in 9 of the 23 (39%) of the assays conducted. Specifically, 4 of 15 (27%) sandwich immunoassays were falsely decreased while five of eight (63%) competitive binding assays were falsely increased.

“Among the 23 biotinylated assays studied, biotin interference was of greatest clinical significance in the OCD Vitros TSH assay, where falsely decreased TSH concentrations (to less than 0.15 mU/L) could have resulted in misdiagnosis of thyrotoxicosis in otherwise euthyroid individuals,” according to Dr. Li and her associates, “Likewise, falsely decreased OCD Vitros NT-proBNP, to lower than assay detection limits, could possibly result in failure to identify congestive heart failure.”

One investigator received funding and nonfinanical support from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, one reported receiving financial support from Abbott Laboratories, and another reported receiving personal fees from Roche and Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Li and the other researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

Biotin supplementation showed signs of interference with biotinylated assays in a crossover trial.

The proposed benefits of biotin (vitamin B7), including stimulating hair growth and assisting in the treatment of various forms of diabetes, have made it a popular supplement. Supplementation generally leads to artificially high levels of biotin, which was shown to cause inaccurate results in biotinylated assays, according to Danni Li, PhD, of the advanced research and diagnostic laboratory at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and her colleagues.

They analyzed the results of both biotinylated and nonbiotinylated assays of six patients – two women and four men – who ingested 10 mg/day of biotin supplement for 7 days. Two blood samples were obtained in the course of the study: one prior to starting biotin supplementation as a baseline and one a week ofter biotin supplementation had ended. The assays tested the presence of nine hormones and two nonhormones using multiple diagnostic systems to run the assays. In total, 37 immunoassays were conducted on each sample (JAMA. 2017;318[12]:1150-60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13705).

Two immunoassay testing techniques were used in the diagnostic assays. The sandwich technique was used in testing TSH, parathyroid hormone (PTH), prolactin, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), PSA, and ferritin and competitive technique was used in testing total T4, total T3, free T4, free T3, and 25-OHD. In assays utilizing competitive techniques, false highs were reported in three Roche cobas e602 machines and one Siemens Vista Dimension 1500 machine.

Assays utilizing the sandwich technique experienced false decreases in TSH, PTH, and NT-proBNP when compared with baseline measurements in Roche cobas e602 and OCD Vitros 5600 machines. A predominance of the falsely low results were present in the assays conducted by the OCD Vitros machine, with significant changes from baseline measurements. TSH experienced a 94% decrease of 1.67 mIU/L, PTH experienced a 61% decrease of 25.8 pg/mL, and NT-proBNP falsely decreased by more than 13.9 pg/mL. In Roche cobas e602 assays, TSH levels were falsely low and measurements decreased by 0.72 mIU/L (37%) when compared with baseline measurements.

Biotin did not interfere in all biotinylated assays and was only observed in 9 of the 23 (39%) of the assays conducted. Specifically, 4 of 15 (27%) sandwich immunoassays were falsely decreased while five of eight (63%) competitive binding assays were falsely increased.

“Among the 23 biotinylated assays studied, biotin interference was of greatest clinical significance in the OCD Vitros TSH assay, where falsely decreased TSH concentrations (to less than 0.15 mU/L) could have resulted in misdiagnosis of thyrotoxicosis in otherwise euthyroid individuals,” according to Dr. Li and her associates, “Likewise, falsely decreased OCD Vitros NT-proBNP, to lower than assay detection limits, could possibly result in failure to identify congestive heart failure.”

One investigator received funding and nonfinanical support from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, one reported receiving financial support from Abbott Laboratories, and another reported receiving personal fees from Roche and Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Li and the other researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: 9 of 23 biotinylated (39%) showed signs of interference from biotin ingestion.

Data source: Nonrandomized crossover trial of six participants at an academic medical center.

Disclosures: One investigator received funding and nonfinanical support from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, one reported receiving financial support from Abbott Laboratories, and another reported receiving personal fees from Roche and Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Li and the other researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

It’s a beautiful day to discuss inflammatory bowel disease

Uma Mahadevan, MD, AGAF, and I moderated this session on IBD, and we were fortunate enough to secure four of the best IBD educators in the AGA.

David Rubin, MD, AGAF, opened with “Selecting the correct therapy for your outpatients with IBD: From mesalamine to biologics.” Treatment goals have evolved from symptom control to remission based on measures of inflammation (e.g., serum C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, or endoscopy). For ulcerative colitis (UC), high-risk markers include extensive disease, deep ulcers, younger age at diagnosis, elevated biomarkers, and early need for steroids or hospitalization. For Crohn’s disease (CD), these include younger age, extensive involvement, and fistulizing disease. The 5-aminosalicylate drugs remain a backbone in mild to moderate UC. Judicious use of corticosteroids is reasonable, but we need an exit strategy. The thiopurines are decent drugs, but studies have called into question their efficacy as monotherapy, and safety issues persist. Methotrexate is underutilized. The anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) biologics are excellent therapies but controversies persist as to whether these drugs require combination therapy or if they can be managed as “optimized monotherapy” with therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). There are now two infliximab biosimilars available in the U.S.. Vedolizumab is an efficacious gut-selective anti-integrin (for both CD and UC). Ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/23 antibody, is now available for moderate to severe CD, and has a favorable safety profile.

Fernando Velayos, MD, AGAF, discussed “Surveillance for dysplasia: What is the standard of care in 2017?” General principles for surveillance colonoscopy in IBD include having quiescent disease, since inflammation can reduce ability to detect lesions, and good colonic preparation. The three U.S. society guidelines recommend starting surveillance after 8 years of disease. Patients with concomitant primary schlerosing cholangitis should begin surveillance immediately. Frequency of surveillance ranges every 1-3 years depending on histology. A meta-analysis showed a higher incremental dysplasia yield with chromoendoscopy compared to standard white-light colonoscopy. If visible dysplasia can be endoscopically resected, then continued surveillance rather than colectomy is recommended.

Sunanda Kane, MD, AGAF, discussed “Managing special populations: the transitioning adolescent, the gravid, and the elderly.” The transition from pediatric to adult IBD care is a high-risk time because the patient may be lost to follow-up or not adhere to the medical regimen, resulting in increased risk of flare. Successful transition requires developmental maturity of the patient, a certain style of parental involvement, and care coordination of the medical team. For women with IBD considering pregnancy, active IBD at the time of conception significantly increases the risk of flare. Women with CD who have no history of perianal disease don’t have an increased risk of perianal disease with vaginal delivery. A meta-analysis of the risk of congenital malformations with thiopurines found no significant association. Infliximab levels were likely to rise in the mother during the second and third trimesters (versus no increase with adalimumab), so one could consider TDM to guide dosing. In the PIANO study, anti-TNF therapy in the third trimester was neither associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes nor with infections up to 1 year for children. Patients who develop IBD later in life are more likely to have colonic inflammation. Elderly UC patients are more likely to require surgery, and postop mortality is higher for both CD and UC.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the AGA Postgraduate Courses held at DDW 2017. Dr. Loftus is a professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Uma Mahadevan, MD, AGAF, and I moderated this session on IBD, and we were fortunate enough to secure four of the best IBD educators in the AGA.

David Rubin, MD, AGAF, opened with “Selecting the correct therapy for your outpatients with IBD: From mesalamine to biologics.” Treatment goals have evolved from symptom control to remission based on measures of inflammation (e.g., serum C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, or endoscopy). For ulcerative colitis (UC), high-risk markers include extensive disease, deep ulcers, younger age at diagnosis, elevated biomarkers, and early need for steroids or hospitalization. For Crohn’s disease (CD), these include younger age, extensive involvement, and fistulizing disease. The 5-aminosalicylate drugs remain a backbone in mild to moderate UC. Judicious use of corticosteroids is reasonable, but we need an exit strategy. The thiopurines are decent drugs, but studies have called into question their efficacy as monotherapy, and safety issues persist. Methotrexate is underutilized. The anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) biologics are excellent therapies but controversies persist as to whether these drugs require combination therapy or if they can be managed as “optimized monotherapy” with therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). There are now two infliximab biosimilars available in the U.S.. Vedolizumab is an efficacious gut-selective anti-integrin (for both CD and UC). Ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/23 antibody, is now available for moderate to severe CD, and has a favorable safety profile.

Fernando Velayos, MD, AGAF, discussed “Surveillance for dysplasia: What is the standard of care in 2017?” General principles for surveillance colonoscopy in IBD include having quiescent disease, since inflammation can reduce ability to detect lesions, and good colonic preparation. The three U.S. society guidelines recommend starting surveillance after 8 years of disease. Patients with concomitant primary schlerosing cholangitis should begin surveillance immediately. Frequency of surveillance ranges every 1-3 years depending on histology. A meta-analysis showed a higher incremental dysplasia yield with chromoendoscopy compared to standard white-light colonoscopy. If visible dysplasia can be endoscopically resected, then continued surveillance rather than colectomy is recommended.

Sunanda Kane, MD, AGAF, discussed “Managing special populations: the transitioning adolescent, the gravid, and the elderly.” The transition from pediatric to adult IBD care is a high-risk time because the patient may be lost to follow-up or not adhere to the medical regimen, resulting in increased risk of flare. Successful transition requires developmental maturity of the patient, a certain style of parental involvement, and care coordination of the medical team. For women with IBD considering pregnancy, active IBD at the time of conception significantly increases the risk of flare. Women with CD who have no history of perianal disease don’t have an increased risk of perianal disease with vaginal delivery. A meta-analysis of the risk of congenital malformations with thiopurines found no significant association. Infliximab levels were likely to rise in the mother during the second and third trimesters (versus no increase with adalimumab), so one could consider TDM to guide dosing. In the PIANO study, anti-TNF therapy in the third trimester was neither associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes nor with infections up to 1 year for children. Patients who develop IBD later in life are more likely to have colonic inflammation. Elderly UC patients are more likely to require surgery, and postop mortality is higher for both CD and UC.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the AGA Postgraduate Courses held at DDW 2017. Dr. Loftus is a professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Uma Mahadevan, MD, AGAF, and I moderated this session on IBD, and we were fortunate enough to secure four of the best IBD educators in the AGA.

David Rubin, MD, AGAF, opened with “Selecting the correct therapy for your outpatients with IBD: From mesalamine to biologics.” Treatment goals have evolved from symptom control to remission based on measures of inflammation (e.g., serum C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, or endoscopy). For ulcerative colitis (UC), high-risk markers include extensive disease, deep ulcers, younger age at diagnosis, elevated biomarkers, and early need for steroids or hospitalization. For Crohn’s disease (CD), these include younger age, extensive involvement, and fistulizing disease. The 5-aminosalicylate drugs remain a backbone in mild to moderate UC. Judicious use of corticosteroids is reasonable, but we need an exit strategy. The thiopurines are decent drugs, but studies have called into question their efficacy as monotherapy, and safety issues persist. Methotrexate is underutilized. The anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) biologics are excellent therapies but controversies persist as to whether these drugs require combination therapy or if they can be managed as “optimized monotherapy” with therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). There are now two infliximab biosimilars available in the U.S.. Vedolizumab is an efficacious gut-selective anti-integrin (for both CD and UC). Ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/23 antibody, is now available for moderate to severe CD, and has a favorable safety profile.

Fernando Velayos, MD, AGAF, discussed “Surveillance for dysplasia: What is the standard of care in 2017?” General principles for surveillance colonoscopy in IBD include having quiescent disease, since inflammation can reduce ability to detect lesions, and good colonic preparation. The three U.S. society guidelines recommend starting surveillance after 8 years of disease. Patients with concomitant primary schlerosing cholangitis should begin surveillance immediately. Frequency of surveillance ranges every 1-3 years depending on histology. A meta-analysis showed a higher incremental dysplasia yield with chromoendoscopy compared to standard white-light colonoscopy. If visible dysplasia can be endoscopically resected, then continued surveillance rather than colectomy is recommended.

Sunanda Kane, MD, AGAF, discussed “Managing special populations: the transitioning adolescent, the gravid, and the elderly.” The transition from pediatric to adult IBD care is a high-risk time because the patient may be lost to follow-up or not adhere to the medical regimen, resulting in increased risk of flare. Successful transition requires developmental maturity of the patient, a certain style of parental involvement, and care coordination of the medical team. For women with IBD considering pregnancy, active IBD at the time of conception significantly increases the risk of flare. Women with CD who have no history of perianal disease don’t have an increased risk of perianal disease with vaginal delivery. A meta-analysis of the risk of congenital malformations with thiopurines found no significant association. Infliximab levels were likely to rise in the mother during the second and third trimesters (versus no increase with adalimumab), so one could consider TDM to guide dosing. In the PIANO study, anti-TNF therapy in the third trimester was neither associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes nor with infections up to 1 year for children. Patients who develop IBD later in life are more likely to have colonic inflammation. Elderly UC patients are more likely to require surgery, and postop mortality is higher for both CD and UC.

This is a summary provided by the moderator of one of the AGA Postgraduate Courses held at DDW 2017. Dr. Loftus is a professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

Cultivating competencies for value-based care

It is my privilege this month to assume responsibility for the “Practice Management: The Road Ahead” section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. I am honored to join an impressive board of editors led by Dr Fasiha Kanwal, and anchored by global leaders in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology. This board of editors promises to continue the high level of excellence that has propelled the journal to its preeminent position among clinical journals. I am confident that the practice management section will uphold that tradition and continue to meet the expectation of our readers. I would like to mark this transition by acknowledging the history of the practice management section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and outlining a vision for the future.

The section was introduced in 2010 under the leadership of Dr. Joel V. Brill. The section, titled “Practice Management: Opportunities and Challenges,” aimed to help practices navigate the disparate issues facing the field. Some of these issues included use of capnography in endoscopy, the importance of registries for quality reporting, and the burdens of meaningful use on physician practices. Dr Brill introduced this section in a video in May 2010 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8FMsc2Wl5E8). Dr. Brill’s reference to these “interesting and challenging times” in gastroenterology resonates even more loudly today.

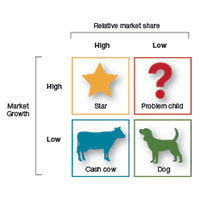

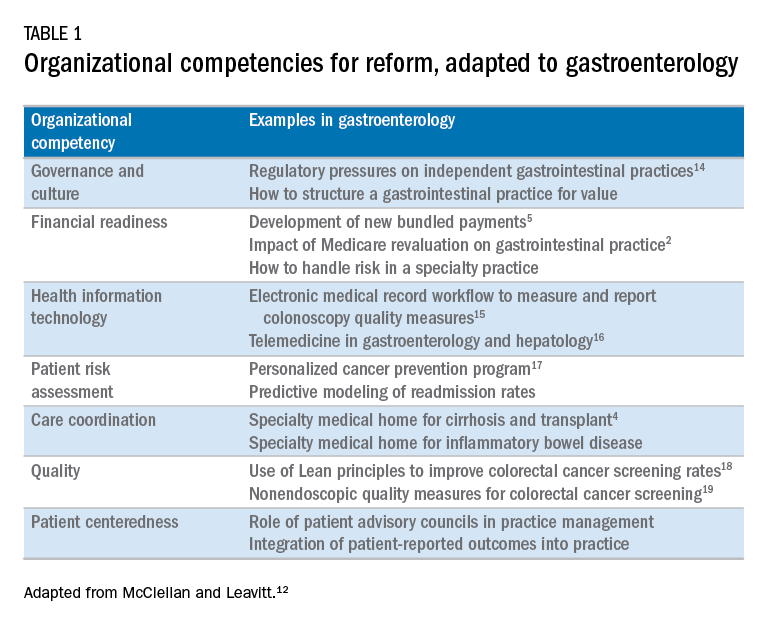

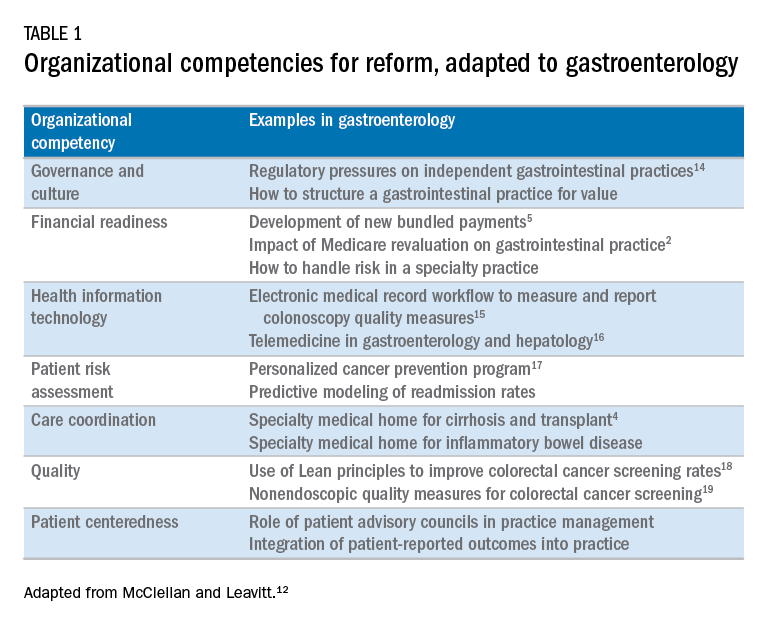

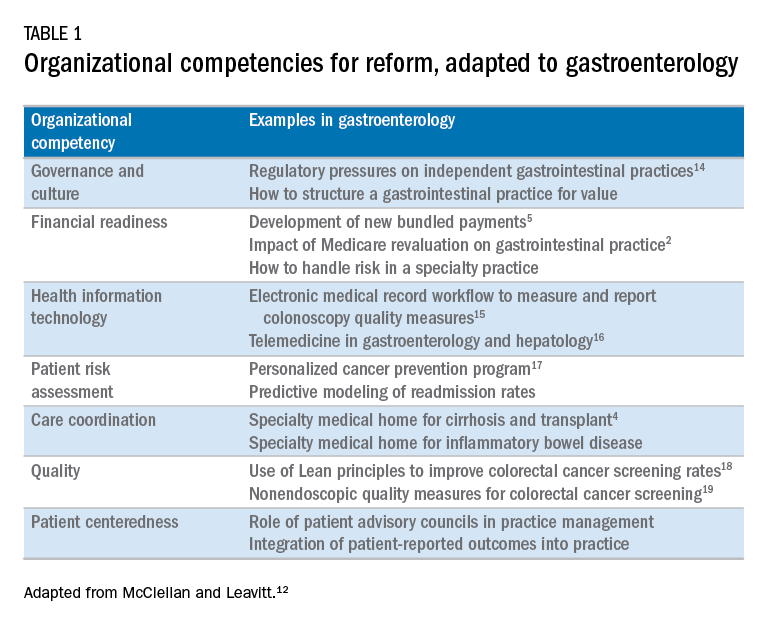

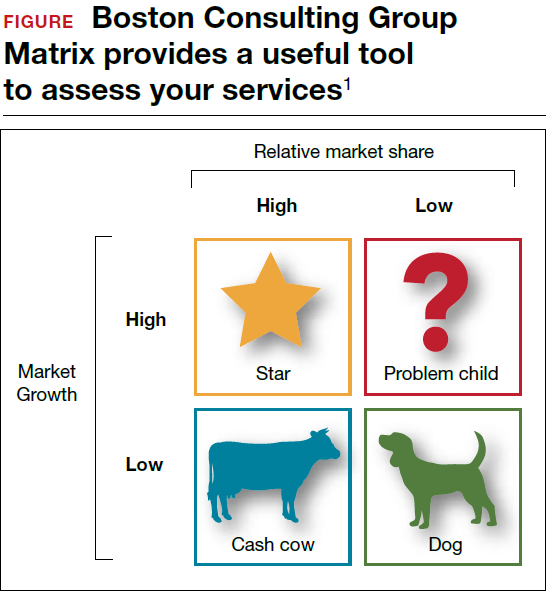

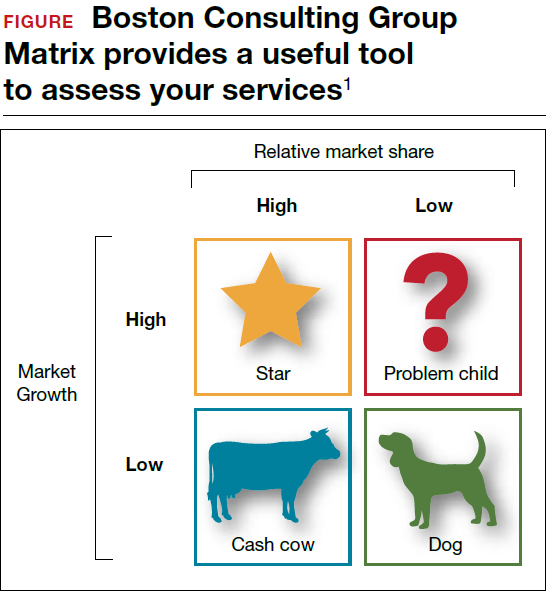

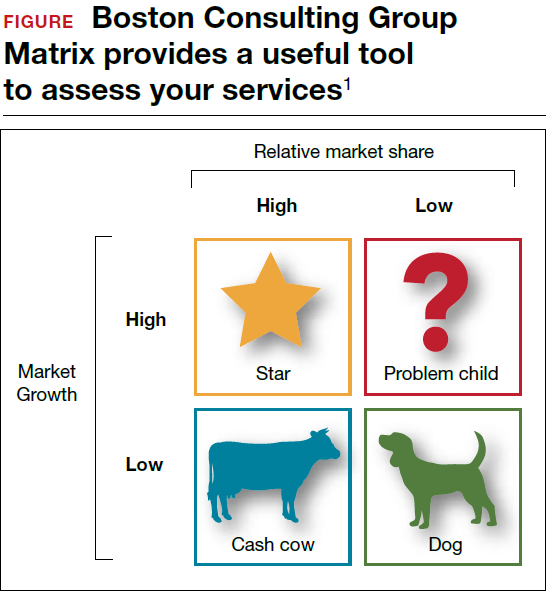

Over the next 5 years, the Road Ahead section will continue and strengthen its focus on the current and emerging issues facing gastroenterology and hepatology practices. I believe that high-value care will continue to be a high priority for patients and payers alike. Early results with payment reform around value have been mixed, in large part because of challenges in health systems and practices developing the competencies required for such reform.12 These competencies include governance and culture, financial readiness, health information technology, patient risk assessment, care coordination, quality, and patient centeredness. I will use this conceptual framework of organizational competencies, and their application in gastroenterology and hepatology, to help curate the Road Ahead section (Table 1). Key themes will include the following:

- • Governance and culture: The structure of health delivery systems, as conceptualized by Donabedian,13 is a key determinant of quality. Structural attributes include regulatory requirements on gastrointestinal practices, such as the rules governing use of anesthesia providers in ambulatory surgical settings; role of allied health professionals in clinical settings; and the impact of financial incentives in driving provider behavior.

- • Financial readiness: Value-based reimbursement, accountable care, medical homes, reference pricing, and physician tiering are some of the new terms in this era of value-based medicine. It is important for practices to assess patient costs longitudinally and manage financial risks. The Road Ahead section will continue to include papers that describe the impact of these reforms on gastroenterology and hepatology practices while providing guidance on implementation of these new models of care. Some examples include papers on the effect of payment policy on specialty practices, the development of a medical home in inflammatory bowel disease, and the physician experience with episode-based payments for colonoscopy.

- • Health information technology: All of the organizational competencies required for reform rely on a robust information technology platform that collects meaningful data and harnesses that data for analytic purposes. These platforms can be enterprise systems deployed by large health delivery systems or smaller, more nimble platforms, created by innovative start-up companies. The Road Ahead will include papers that share best practices in the use of these platforms to provide high-quality and cost-efficient care. In addition, the Road Ahead will continue to explore the use of health information technology to expand the reach of clinicians beyond brick and mortar clinics.

- • Patient risk assessment: Tailoring interventions to high-risk patients is necessary to deploy limited resources in a cost-effective manner. Risk assessment is also needed to more accurately and effectively personalize care for patients with chronic conditions. The Road Ahead will include papers that evaluate risk assessment tools and/or describe real-life implementation of these tools in different contexts.

- • Care coordination: The ability to provide team-based longitudinal care across the continuum of care will be integral to providing high value health care. The Road Ahead will serve as a means to disseminate best practices and innovative methods to care for increasingly complex patients, especially those with chronic diseases, such as cirrhosis and inflammatory bowel disease. For example, papers will explore the implementation of specialty medical homes, patient navigators, community-based care services, and involvement of patients in their own care.

- • Quality improvement: Providing high-value care by definition will require clinicians to accurately measure the quality of care provided to patients and use data to guide process improvement. The Road Ahead will continue to serve as an educational resource for clinicians with papers that discuss challenges and opportunities in quality measurement and improvement. Similarly, this section will present data on novel or impactful quality-improvement initiatives.

- • Patient centeredness: Patient experience measures and patient-reported outcomes are becoming increasingly important as meaningful indicators of quality. These measures are designed to ensure that patient perspectives are incorporated into the governance, design, and delivery of health care. The Road Ahead will serve as a dissemination mechanism for sharing best practices in developing, validating, implementing, and tracking patient-reported outcomes.

I consider Dr. Brill and Dr. Allen as mentors who have taught me tremendously about the business of medicine and the importance of physician leadership. I had the opportunity to coauthor several papers and book chapters with them. More recently, I have had the privilege to work closely with them in my role as the Chair of the American Gastroenterological Association Quality Measures Committee. It is an honor to now join their league as the editor for the Road Ahead section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. These are indeed big shoes to fill. The section will retain the “Road Ahead” title in an acknowledgement of the continued importance of the issues outlined by Dr Allen. We will build on this theme to focus on not just the destination, but also the bumps in the road, the unexpected curves, the rest areas, beautiful vistas, and the indulgent road food. Hopefully no accidents along the way!

References

1. Allen, J.I. The road ahead. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:692-6.

2. Dorn, S.D., Vesy, C.J. Medicare’s revaluation of gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: implications for academic and community-based practices. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:924-8.

3. Dorn, S.D. The road ahead 3.0: changing payments, changing practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:785-9.

4. Meier, S.K., Shah, N.D., Talwalkar, J.A. Adapting the patient-centered specialty practice model for populations with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:492-6.

5. Mehta, S.J. Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1681-4.

6. Weizman, A.V., Mosko, J., Bollegala, N., et al. Quality improvement primer series: launching a quality improvement initiative. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:1067-71.

7. Bernstein, M., Hou, J.K., Weizman, A.V., et al. Quality improvement primer series: how to sustain a quality improvement effort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:1371-5.

8. Bollegala, N., Patel, K., Mosko, J.D., et al. Quality improvement primer series: the plan-do-study-act cycle and data display. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1230-3.

9. Adams, M.A. Covert recording by patients of encounters with gastroenterology providers: path to empowerment or breach of trust?. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:13-6.

10. Oza, V.M., El-Dika, S., and Adams, M.A. Reaching safe harbor: legal implications of clinical practice guidelines. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:172-4.

11. Lin, M., Pappas, S.C., Sellin, J., et al. Curbside consultations: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:2-4.

12. McClellan, M.B., Leavitt, M.O. Competencies and tools to shift payments from volume to value. JAMA. 2016; 316: 1655–1656

13. Donabedian, A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q. 1966;44:166-203.

14. Rosenberg, F.B., Kim, L.S., Ketover, S.R. Challenges facing independent integrated gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:335-8.

15. Leiman, D.A., Metz, D.C., Ginsberg, G.G., et al. A novel electronic medical record-based workflow to measure and report colonoscopy quality measures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:333-7.

16. Cross, R.K., Kane, S. Integration of telemedicine into clinical gastroenterology and hepatology Practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:175-81.

17. Llor, X. Building a cancer genetics and prevention program. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1516-20.

18. Patel, K.K., Cummings, S., Sellin, J., et al. Applying Lean design principles to a gastrointestinal endoscopy program for uninsured patients improves health care utilization. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1556-9.

19. Saini, S.D., Adams, M.A., Brill, J.V., et al. Colorectal cancer screening quality measures: beyond colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:644-7.

Dr. Gellad is an associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Durham VA Medical Center, Durham, N.C.; and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C. He reports a consulting relationship with Merck & Co. and he is also a cofounder and equity holder in Higgs Boson, LLC. He is funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award (CDA 14-158 ).

It is my privilege this month to assume responsibility for the “Practice Management: The Road Ahead” section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. I am honored to join an impressive board of editors led by Dr Fasiha Kanwal, and anchored by global leaders in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology. This board of editors promises to continue the high level of excellence that has propelled the journal to its preeminent position among clinical journals. I am confident that the practice management section will uphold that tradition and continue to meet the expectation of our readers. I would like to mark this transition by acknowledging the history of the practice management section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and outlining a vision for the future.

The section was introduced in 2010 under the leadership of Dr. Joel V. Brill. The section, titled “Practice Management: Opportunities and Challenges,” aimed to help practices navigate the disparate issues facing the field. Some of these issues included use of capnography in endoscopy, the importance of registries for quality reporting, and the burdens of meaningful use on physician practices. Dr Brill introduced this section in a video in May 2010 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8FMsc2Wl5E8). Dr. Brill’s reference to these “interesting and challenging times” in gastroenterology resonates even more loudly today.

Over the next 5 years, the Road Ahead section will continue and strengthen its focus on the current and emerging issues facing gastroenterology and hepatology practices. I believe that high-value care will continue to be a high priority for patients and payers alike. Early results with payment reform around value have been mixed, in large part because of challenges in health systems and practices developing the competencies required for such reform.12 These competencies include governance and culture, financial readiness, health information technology, patient risk assessment, care coordination, quality, and patient centeredness. I will use this conceptual framework of organizational competencies, and their application in gastroenterology and hepatology, to help curate the Road Ahead section (Table 1). Key themes will include the following:

- • Governance and culture: The structure of health delivery systems, as conceptualized by Donabedian,13 is a key determinant of quality. Structural attributes include regulatory requirements on gastrointestinal practices, such as the rules governing use of anesthesia providers in ambulatory surgical settings; role of allied health professionals in clinical settings; and the impact of financial incentives in driving provider behavior.

- • Financial readiness: Value-based reimbursement, accountable care, medical homes, reference pricing, and physician tiering are some of the new terms in this era of value-based medicine. It is important for practices to assess patient costs longitudinally and manage financial risks. The Road Ahead section will continue to include papers that describe the impact of these reforms on gastroenterology and hepatology practices while providing guidance on implementation of these new models of care. Some examples include papers on the effect of payment policy on specialty practices, the development of a medical home in inflammatory bowel disease, and the physician experience with episode-based payments for colonoscopy.

- • Health information technology: All of the organizational competencies required for reform rely on a robust information technology platform that collects meaningful data and harnesses that data for analytic purposes. These platforms can be enterprise systems deployed by large health delivery systems or smaller, more nimble platforms, created by innovative start-up companies. The Road Ahead will include papers that share best practices in the use of these platforms to provide high-quality and cost-efficient care. In addition, the Road Ahead will continue to explore the use of health information technology to expand the reach of clinicians beyond brick and mortar clinics.

- • Patient risk assessment: Tailoring interventions to high-risk patients is necessary to deploy limited resources in a cost-effective manner. Risk assessment is also needed to more accurately and effectively personalize care for patients with chronic conditions. The Road Ahead will include papers that evaluate risk assessment tools and/or describe real-life implementation of these tools in different contexts.

- • Care coordination: The ability to provide team-based longitudinal care across the continuum of care will be integral to providing high value health care. The Road Ahead will serve as a means to disseminate best practices and innovative methods to care for increasingly complex patients, especially those with chronic diseases, such as cirrhosis and inflammatory bowel disease. For example, papers will explore the implementation of specialty medical homes, patient navigators, community-based care services, and involvement of patients in their own care.

- • Quality improvement: Providing high-value care by definition will require clinicians to accurately measure the quality of care provided to patients and use data to guide process improvement. The Road Ahead will continue to serve as an educational resource for clinicians with papers that discuss challenges and opportunities in quality measurement and improvement. Similarly, this section will present data on novel or impactful quality-improvement initiatives.

- • Patient centeredness: Patient experience measures and patient-reported outcomes are becoming increasingly important as meaningful indicators of quality. These measures are designed to ensure that patient perspectives are incorporated into the governance, design, and delivery of health care. The Road Ahead will serve as a dissemination mechanism for sharing best practices in developing, validating, implementing, and tracking patient-reported outcomes.

I consider Dr. Brill and Dr. Allen as mentors who have taught me tremendously about the business of medicine and the importance of physician leadership. I had the opportunity to coauthor several papers and book chapters with them. More recently, I have had the privilege to work closely with them in my role as the Chair of the American Gastroenterological Association Quality Measures Committee. It is an honor to now join their league as the editor for the Road Ahead section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. These are indeed big shoes to fill. The section will retain the “Road Ahead” title in an acknowledgement of the continued importance of the issues outlined by Dr Allen. We will build on this theme to focus on not just the destination, but also the bumps in the road, the unexpected curves, the rest areas, beautiful vistas, and the indulgent road food. Hopefully no accidents along the way!

References

1. Allen, J.I. The road ahead. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:692-6.

2. Dorn, S.D., Vesy, C.J. Medicare’s revaluation of gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: implications for academic and community-based practices. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:924-8.

3. Dorn, S.D. The road ahead 3.0: changing payments, changing practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:785-9.

4. Meier, S.K., Shah, N.D., Talwalkar, J.A. Adapting the patient-centered specialty practice model for populations with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:492-6.

5. Mehta, S.J. Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1681-4.

6. Weizman, A.V., Mosko, J., Bollegala, N., et al. Quality improvement primer series: launching a quality improvement initiative. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:1067-71.

7. Bernstein, M., Hou, J.K., Weizman, A.V., et al. Quality improvement primer series: how to sustain a quality improvement effort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:1371-5.

8. Bollegala, N., Patel, K., Mosko, J.D., et al. Quality improvement primer series: the plan-do-study-act cycle and data display. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1230-3.

9. Adams, M.A. Covert recording by patients of encounters with gastroenterology providers: path to empowerment or breach of trust?. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:13-6.

10. Oza, V.M., El-Dika, S., and Adams, M.A. Reaching safe harbor: legal implications of clinical practice guidelines. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:172-4.

11. Lin, M., Pappas, S.C., Sellin, J., et al. Curbside consultations: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:2-4.

12. McClellan, M.B., Leavitt, M.O. Competencies and tools to shift payments from volume to value. JAMA. 2016; 316: 1655–1656

13. Donabedian, A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q. 1966;44:166-203.

14. Rosenberg, F.B., Kim, L.S., Ketover, S.R. Challenges facing independent integrated gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:335-8.

15. Leiman, D.A., Metz, D.C., Ginsberg, G.G., et al. A novel electronic medical record-based workflow to measure and report colonoscopy quality measures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:333-7.

16. Cross, R.K., Kane, S. Integration of telemedicine into clinical gastroenterology and hepatology Practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:175-81.

17. Llor, X. Building a cancer genetics and prevention program. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1516-20.

18. Patel, K.K., Cummings, S., Sellin, J., et al. Applying Lean design principles to a gastrointestinal endoscopy program for uninsured patients improves health care utilization. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1556-9.

19. Saini, S.D., Adams, M.A., Brill, J.V., et al. Colorectal cancer screening quality measures: beyond colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:644-7.

Dr. Gellad is an associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Durham VA Medical Center, Durham, N.C.; and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C. He reports a consulting relationship with Merck & Co. and he is also a cofounder and equity holder in Higgs Boson, LLC. He is funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award (CDA 14-158 ).

It is my privilege this month to assume responsibility for the “Practice Management: The Road Ahead” section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. I am honored to join an impressive board of editors led by Dr Fasiha Kanwal, and anchored by global leaders in the field of gastroenterology and hepatology. This board of editors promises to continue the high level of excellence that has propelled the journal to its preeminent position among clinical journals. I am confident that the practice management section will uphold that tradition and continue to meet the expectation of our readers. I would like to mark this transition by acknowledging the history of the practice management section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and outlining a vision for the future.

The section was introduced in 2010 under the leadership of Dr. Joel V. Brill. The section, titled “Practice Management: Opportunities and Challenges,” aimed to help practices navigate the disparate issues facing the field. Some of these issues included use of capnography in endoscopy, the importance of registries for quality reporting, and the burdens of meaningful use on physician practices. Dr Brill introduced this section in a video in May 2010 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8FMsc2Wl5E8). Dr. Brill’s reference to these “interesting and challenging times” in gastroenterology resonates even more loudly today.

Over the next 5 years, the Road Ahead section will continue and strengthen its focus on the current and emerging issues facing gastroenterology and hepatology practices. I believe that high-value care will continue to be a high priority for patients and payers alike. Early results with payment reform around value have been mixed, in large part because of challenges in health systems and practices developing the competencies required for such reform.12 These competencies include governance and culture, financial readiness, health information technology, patient risk assessment, care coordination, quality, and patient centeredness. I will use this conceptual framework of organizational competencies, and their application in gastroenterology and hepatology, to help curate the Road Ahead section (Table 1). Key themes will include the following:

- • Governance and culture: The structure of health delivery systems, as conceptualized by Donabedian,13 is a key determinant of quality. Structural attributes include regulatory requirements on gastrointestinal practices, such as the rules governing use of anesthesia providers in ambulatory surgical settings; role of allied health professionals in clinical settings; and the impact of financial incentives in driving provider behavior.

- • Financial readiness: Value-based reimbursement, accountable care, medical homes, reference pricing, and physician tiering are some of the new terms in this era of value-based medicine. It is important for practices to assess patient costs longitudinally and manage financial risks. The Road Ahead section will continue to include papers that describe the impact of these reforms on gastroenterology and hepatology practices while providing guidance on implementation of these new models of care. Some examples include papers on the effect of payment policy on specialty practices, the development of a medical home in inflammatory bowel disease, and the physician experience with episode-based payments for colonoscopy.

- • Health information technology: All of the organizational competencies required for reform rely on a robust information technology platform that collects meaningful data and harnesses that data for analytic purposes. These platforms can be enterprise systems deployed by large health delivery systems or smaller, more nimble platforms, created by innovative start-up companies. The Road Ahead will include papers that share best practices in the use of these platforms to provide high-quality and cost-efficient care. In addition, the Road Ahead will continue to explore the use of health information technology to expand the reach of clinicians beyond brick and mortar clinics.

- • Patient risk assessment: Tailoring interventions to high-risk patients is necessary to deploy limited resources in a cost-effective manner. Risk assessment is also needed to more accurately and effectively personalize care for patients with chronic conditions. The Road Ahead will include papers that evaluate risk assessment tools and/or describe real-life implementation of these tools in different contexts.

- • Care coordination: The ability to provide team-based longitudinal care across the continuum of care will be integral to providing high value health care. The Road Ahead will serve as a means to disseminate best practices and innovative methods to care for increasingly complex patients, especially those with chronic diseases, such as cirrhosis and inflammatory bowel disease. For example, papers will explore the implementation of specialty medical homes, patient navigators, community-based care services, and involvement of patients in their own care.

- • Quality improvement: Providing high-value care by definition will require clinicians to accurately measure the quality of care provided to patients and use data to guide process improvement. The Road Ahead will continue to serve as an educational resource for clinicians with papers that discuss challenges and opportunities in quality measurement and improvement. Similarly, this section will present data on novel or impactful quality-improvement initiatives.

- • Patient centeredness: Patient experience measures and patient-reported outcomes are becoming increasingly important as meaningful indicators of quality. These measures are designed to ensure that patient perspectives are incorporated into the governance, design, and delivery of health care. The Road Ahead will serve as a dissemination mechanism for sharing best practices in developing, validating, implementing, and tracking patient-reported outcomes.

I consider Dr. Brill and Dr. Allen as mentors who have taught me tremendously about the business of medicine and the importance of physician leadership. I had the opportunity to coauthor several papers and book chapters with them. More recently, I have had the privilege to work closely with them in my role as the Chair of the American Gastroenterological Association Quality Measures Committee. It is an honor to now join their league as the editor for the Road Ahead section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. These are indeed big shoes to fill. The section will retain the “Road Ahead” title in an acknowledgement of the continued importance of the issues outlined by Dr Allen. We will build on this theme to focus on not just the destination, but also the bumps in the road, the unexpected curves, the rest areas, beautiful vistas, and the indulgent road food. Hopefully no accidents along the way!

References

1. Allen, J.I. The road ahead. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:692-6.

2. Dorn, S.D., Vesy, C.J. Medicare’s revaluation of gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: implications for academic and community-based practices. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:924-8.

3. Dorn, S.D. The road ahead 3.0: changing payments, changing practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:785-9.

4. Meier, S.K., Shah, N.D., Talwalkar, J.A. Adapting the patient-centered specialty practice model for populations with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:492-6.

5. Mehta, S.J. Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1681-4.

6. Weizman, A.V., Mosko, J., Bollegala, N., et al. Quality improvement primer series: launching a quality improvement initiative. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:1067-71.

7. Bernstein, M., Hou, J.K., Weizman, A.V., et al. Quality improvement primer series: how to sustain a quality improvement effort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:1371-5.

8. Bollegala, N., Patel, K., Mosko, J.D., et al. Quality improvement primer series: the plan-do-study-act cycle and data display. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1230-3.

9. Adams, M.A. Covert recording by patients of encounters with gastroenterology providers: path to empowerment or breach of trust?. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:13-6.

10. Oza, V.M., El-Dika, S., and Adams, M.A. Reaching safe harbor: legal implications of clinical practice guidelines. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:172-4.

11. Lin, M., Pappas, S.C., Sellin, J., et al. Curbside consultations: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:2-4.

12. McClellan, M.B., Leavitt, M.O. Competencies and tools to shift payments from volume to value. JAMA. 2016; 316: 1655–1656

13. Donabedian, A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q. 1966;44:166-203.

14. Rosenberg, F.B., Kim, L.S., Ketover, S.R. Challenges facing independent integrated gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:335-8.

15. Leiman, D.A., Metz, D.C., Ginsberg, G.G., et al. A novel electronic medical record-based workflow to measure and report colonoscopy quality measures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:333-7.

16. Cross, R.K., Kane, S. Integration of telemedicine into clinical gastroenterology and hepatology Practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:175-81.

17. Llor, X. Building a cancer genetics and prevention program. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1516-20.

18. Patel, K.K., Cummings, S., Sellin, J., et al. Applying Lean design principles to a gastrointestinal endoscopy program for uninsured patients improves health care utilization. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1556-9.

19. Saini, S.D., Adams, M.A., Brill, J.V., et al. Colorectal cancer screening quality measures: beyond colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:644-7.

Dr. Gellad is an associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at Durham VA Medical Center, Durham, N.C.; and Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C. He reports a consulting relationship with Merck & Co. and he is also a cofounder and equity holder in Higgs Boson, LLC. He is funded by Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Career Development Award (CDA 14-158 ).

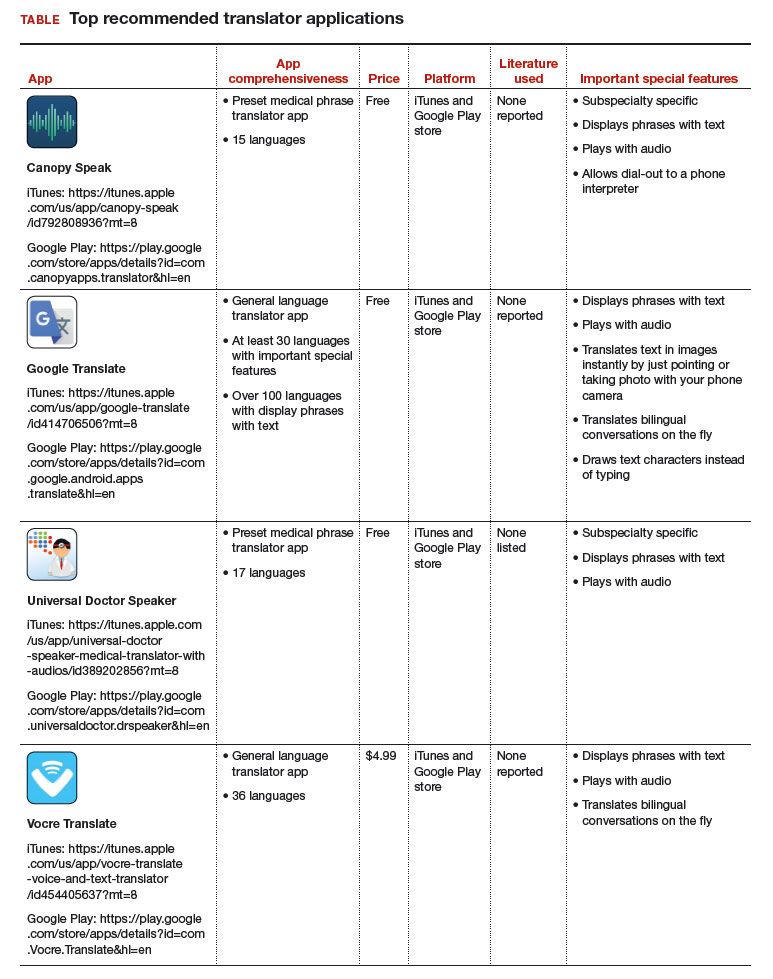

Top translator apps can help you communicate with patients who have limited English proficiency

As the population of patients with limited English proficiency increases throughout English-speaking countries, health care providers often need translator services. Medical translator smartphone applications (apps) are useful tools that can provide ad hoc translator services.

According to the US Census Bureau in 2015, more than 60 million individuals — about 19% of Americans — reported speaking a language other than English at home, and more than 25 million said that they speak English “less than very well.”1,2 The top 5 non-English languages spoken at home were Spanish, French, Chinese, Tagalog, and Vietnamese, encompassing 72% of non-English speakers.

In the health care sector, translator services are essential for providing accurate and culturally competent care. Current options for translator services include face-to-face interpreters, phone-based translator services, and translator apps on mobile devices. In settings where face-to-face interpreters or phone-based translator services are not available, translator apps may provide reasonable alternatives. My colleagues, Dr. Amrin Khander and Dr. Sara Farag, and I identified and evaluated medical translator apps that are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores to aid clinicians in using such apps during clinical encounters.3

Three types of translator apps

Preset medical phrase translator apps require the user to search for or find a question or statement in order to facilitate a conversation. With these types of apps, a health care provider can choose fully conjugated sentences, which then can be played or read back to the patient in the chosen translated language. Within this group of apps, Canopy Speak and Universal Doctor Speaker are highly accessible, since both apps are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores and both are free.

Medical dictionary apps require the user to search for a medical term in one language to receive a translation in another language. These apps are less useful, but they can help providers find and define specific terms in a given language.

General language translator apps require the user to enter a term, statement, or question in one language and then provide a translation in another language. Google Translate and Vocre Translate are examples.

The top recommended translator apps are listed in the TABLE alphabetically and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features).4 I hope the apps described here will help you enhance communication with your patients who have limited English proficiency.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- United States Census Bureau. Detailed language spoken at home and ability to speak English for the population 5 years and over: 2009–2013. http://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html. Published October 2015. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- United States Census Bureau. US population world clock. http://www.census.gov/popclock/?intcmp=home_pop. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- Khander A, Farag S, Chen KT. Identification and rating of medical translator mobile applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system [abstract 321]. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(5 suppl):101S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000514971.96123.20

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478–1483.

As the population of patients with limited English proficiency increases throughout English-speaking countries, health care providers often need translator services. Medical translator smartphone applications (apps) are useful tools that can provide ad hoc translator services.

According to the US Census Bureau in 2015, more than 60 million individuals — about 19% of Americans — reported speaking a language other than English at home, and more than 25 million said that they speak English “less than very well.”1,2 The top 5 non-English languages spoken at home were Spanish, French, Chinese, Tagalog, and Vietnamese, encompassing 72% of non-English speakers.

In the health care sector, translator services are essential for providing accurate and culturally competent care. Current options for translator services include face-to-face interpreters, phone-based translator services, and translator apps on mobile devices. In settings where face-to-face interpreters or phone-based translator services are not available, translator apps may provide reasonable alternatives. My colleagues, Dr. Amrin Khander and Dr. Sara Farag, and I identified and evaluated medical translator apps that are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores to aid clinicians in using such apps during clinical encounters.3

Three types of translator apps

Preset medical phrase translator apps require the user to search for or find a question or statement in order to facilitate a conversation. With these types of apps, a health care provider can choose fully conjugated sentences, which then can be played or read back to the patient in the chosen translated language. Within this group of apps, Canopy Speak and Universal Doctor Speaker are highly accessible, since both apps are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores and both are free.

Medical dictionary apps require the user to search for a medical term in one language to receive a translation in another language. These apps are less useful, but they can help providers find and define specific terms in a given language.

General language translator apps require the user to enter a term, statement, or question in one language and then provide a translation in another language. Google Translate and Vocre Translate are examples.

The top recommended translator apps are listed in the TABLE alphabetically and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features).4 I hope the apps described here will help you enhance communication with your patients who have limited English proficiency.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

As the population of patients with limited English proficiency increases throughout English-speaking countries, health care providers often need translator services. Medical translator smartphone applications (apps) are useful tools that can provide ad hoc translator services.

According to the US Census Bureau in 2015, more than 60 million individuals — about 19% of Americans — reported speaking a language other than English at home, and more than 25 million said that they speak English “less than very well.”1,2 The top 5 non-English languages spoken at home were Spanish, French, Chinese, Tagalog, and Vietnamese, encompassing 72% of non-English speakers.

In the health care sector, translator services are essential for providing accurate and culturally competent care. Current options for translator services include face-to-face interpreters, phone-based translator services, and translator apps on mobile devices. In settings where face-to-face interpreters or phone-based translator services are not available, translator apps may provide reasonable alternatives. My colleagues, Dr. Amrin Khander and Dr. Sara Farag, and I identified and evaluated medical translator apps that are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores to aid clinicians in using such apps during clinical encounters.3

Three types of translator apps

Preset medical phrase translator apps require the user to search for or find a question or statement in order to facilitate a conversation. With these types of apps, a health care provider can choose fully conjugated sentences, which then can be played or read back to the patient in the chosen translated language. Within this group of apps, Canopy Speak and Universal Doctor Speaker are highly accessible, since both apps are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores and both are free.

Medical dictionary apps require the user to search for a medical term in one language to receive a translation in another language. These apps are less useful, but they can help providers find and define specific terms in a given language.

General language translator apps require the user to enter a term, statement, or question in one language and then provide a translation in another language. Google Translate and Vocre Translate are examples.

The top recommended translator apps are listed in the TABLE alphabetically and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features).4 I hope the apps described here will help you enhance communication with your patients who have limited English proficiency.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- United States Census Bureau. Detailed language spoken at home and ability to speak English for the population 5 years and over: 2009–2013. http://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html. Published October 2015. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- United States Census Bureau. US population world clock. http://www.census.gov/popclock/?intcmp=home_pop. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- Khander A, Farag S, Chen KT. Identification and rating of medical translator mobile applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system [abstract 321]. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(5 suppl):101S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000514971.96123.20

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478–1483.

- United States Census Bureau. Detailed language spoken at home and ability to speak English for the population 5 years and over: 2009–2013. http://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html. Published October 2015. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- United States Census Bureau. US population world clock. http://www.census.gov/popclock/?intcmp=home_pop. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- Khander A, Farag S, Chen KT. Identification and rating of medical translator mobile applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system [abstract 321]. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(5 suppl):101S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000514971.96123.20

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478–1483.

No benefit seen for routine low-dose oxygen after stroke

Routine use of low-dose oxygen supplementation in the first days after stroke doesn’t improve overall survival or reduce disability, according to a large new study.

The poststroke death and disability odds ratio was 0.97 for those receiving one of two continuous low-dose oxygen protocols, compared with the control group (95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.05; P = .47).

Participants, who were not hypoxic at enrollment, were randomized 1:1:1 to receive continuous oxygen supplementation for the first 72 hours after stroke, to receive supplementation only at night, or to receive oxygen when indicated by usual care protocols. The average participant age was 72 years and 55% were men in all study arms, and all stroke severity levels were included in the study.

Patients in the two intervention arms received 2 L of oxygen by nasal cannula when their baseline oxygen saturation was greater than 93%, and 3 L when oxygen saturation at baseline was 93% or less. Participation in the study did not preclude more intensive respiratory support when clinically indicated.

Nocturnal supplementation was included as a study arm for two reasons: Poststroke hypoxia is more common at night, and night-only supplementation would avoid any interference with early rehabilitation caused by cumbersome oxygen apparatus and tubing.

Not only was no benefit seen for patients in the pooled intervention arm cohorts, but no benefit was seen for night-time versus continuous oxygen as well. The odds ratio for a better outcome was 1.03 when comparing those receiving continuous oxygen to those who only received nocturnal supplementation (95% CI, 0.93-1.13; P = .61).

First author Christine Roffe, MD, and her collaborators in the Stroke Oxygen Study Collaborative Group also performed subgroup analyses and did not see benefit of oxygen supplementation for older or younger patients, or for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, or more severe strokes.

“Supplemental oxygen could improve outcomes by preventing hypoxia and secondary brain damage but could also have adverse effects,” according to Dr. Roffe, consultant at Keele (England) University and her collaborators.

A much smaller SOS pilot study, they said, had shown improved early neurologic recovery for patients who received supplemental oxygen after stroke, but the pilot also “suggested that oxygen might adversely affect outcome in patients with mild strokes, possibly through formation of toxic free radicals,” wrote the investigators.

These were effects not seen in the larger SO2S study, which was designed to have statistical power to detect even small differences and to do detailed subgroup analysis. For patients like those included in the study, “These findings do not support low-dose oxygen in this setting,” wrote Dr. Roffe and her collaborators.

Dr. Roffe reported receiving compensation from Air Liquide. The study was funded by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health Research.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

Routine use of low-dose oxygen supplementation in the first days after stroke doesn’t improve overall survival or reduce disability, according to a large new study.

The poststroke death and disability odds ratio was 0.97 for those receiving one of two continuous low-dose oxygen protocols, compared with the control group (95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.05; P = .47).

Participants, who were not hypoxic at enrollment, were randomized 1:1:1 to receive continuous oxygen supplementation for the first 72 hours after stroke, to receive supplementation only at night, or to receive oxygen when indicated by usual care protocols. The average participant age was 72 years and 55% were men in all study arms, and all stroke severity levels were included in the study.

Patients in the two intervention arms received 2 L of oxygen by nasal cannula when their baseline oxygen saturation was greater than 93%, and 3 L when oxygen saturation at baseline was 93% or less. Participation in the study did not preclude more intensive respiratory support when clinically indicated.

Nocturnal supplementation was included as a study arm for two reasons: Poststroke hypoxia is more common at night, and night-only supplementation would avoid any interference with early rehabilitation caused by cumbersome oxygen apparatus and tubing.

Not only was no benefit seen for patients in the pooled intervention arm cohorts, but no benefit was seen for night-time versus continuous oxygen as well. The odds ratio for a better outcome was 1.03 when comparing those receiving continuous oxygen to those who only received nocturnal supplementation (95% CI, 0.93-1.13; P = .61).

First author Christine Roffe, MD, and her collaborators in the Stroke Oxygen Study Collaborative Group also performed subgroup analyses and did not see benefit of oxygen supplementation for older or younger patients, or for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, or more severe strokes.

“Supplemental oxygen could improve outcomes by preventing hypoxia and secondary brain damage but could also have adverse effects,” according to Dr. Roffe, consultant at Keele (England) University and her collaborators.

A much smaller SOS pilot study, they said, had shown improved early neurologic recovery for patients who received supplemental oxygen after stroke, but the pilot also “suggested that oxygen might adversely affect outcome in patients with mild strokes, possibly through formation of toxic free radicals,” wrote the investigators.

These were effects not seen in the larger SO2S study, which was designed to have statistical power to detect even small differences and to do detailed subgroup analysis. For patients like those included in the study, “These findings do not support low-dose oxygen in this setting,” wrote Dr. Roffe and her collaborators.

Dr. Roffe reported receiving compensation from Air Liquide. The study was funded by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health Research.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

Routine use of low-dose oxygen supplementation in the first days after stroke doesn’t improve overall survival or reduce disability, according to a large new study.

The poststroke death and disability odds ratio was 0.97 for those receiving one of two continuous low-dose oxygen protocols, compared with the control group (95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.05; P = .47).

Participants, who were not hypoxic at enrollment, were randomized 1:1:1 to receive continuous oxygen supplementation for the first 72 hours after stroke, to receive supplementation only at night, or to receive oxygen when indicated by usual care protocols. The average participant age was 72 years and 55% were men in all study arms, and all stroke severity levels were included in the study.

Patients in the two intervention arms received 2 L of oxygen by nasal cannula when their baseline oxygen saturation was greater than 93%, and 3 L when oxygen saturation at baseline was 93% or less. Participation in the study did not preclude more intensive respiratory support when clinically indicated.

Nocturnal supplementation was included as a study arm for two reasons: Poststroke hypoxia is more common at night, and night-only supplementation would avoid any interference with early rehabilitation caused by cumbersome oxygen apparatus and tubing.

Not only was no benefit seen for patients in the pooled intervention arm cohorts, but no benefit was seen for night-time versus continuous oxygen as well. The odds ratio for a better outcome was 1.03 when comparing those receiving continuous oxygen to those who only received nocturnal supplementation (95% CI, 0.93-1.13; P = .61).

First author Christine Roffe, MD, and her collaborators in the Stroke Oxygen Study Collaborative Group also performed subgroup analyses and did not see benefit of oxygen supplementation for older or younger patients, or for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, or more severe strokes.

“Supplemental oxygen could improve outcomes by preventing hypoxia and secondary brain damage but could also have adverse effects,” according to Dr. Roffe, consultant at Keele (England) University and her collaborators.

A much smaller SOS pilot study, they said, had shown improved early neurologic recovery for patients who received supplemental oxygen after stroke, but the pilot also “suggested that oxygen might adversely affect outcome in patients with mild strokes, possibly through formation of toxic free radicals,” wrote the investigators.

These were effects not seen in the larger SO2S study, which was designed to have statistical power to detect even small differences and to do detailed subgroup analysis. For patients like those included in the study, “These findings do not support low-dose oxygen in this setting,” wrote Dr. Roffe and her collaborators.

Dr. Roffe reported receiving compensation from Air Liquide. The study was funded by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health Research.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The poststroke death and disability odds ratio was 0.97 for those receiving continuous low-dose oxygen, compared with controls.

Data source: Single-blind, multisite, randomized, controlled trial of 8,003 patients admitted with acute stroke.

Disclosures: Dr. Roffe reported receiving compensation from Air Liquide. The study was funded by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health Research.

Sen. Collins deals likely fatal blow to GOP’s health bill

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) became the third GOP senator to confirm a no vote on the latest Republican attempt to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA), a move that likely seals the bill’s fate.

The bill has the support of President Trump and many GOP leaders but has been roundly criticized by medical groups for insuring fewer Americans, failing to provide adequate protections for people with preexisting conditions, and barring Planned Parenthood from Medicaid participation.

“Sweeping reforms to our health care system and to Medicaid can’t be done well in a compressed time frame, especially when the actual bill is a moving target,” Sen. Collins said in a Sept. 25 statement announcing her opposition to a bill sponsored by Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-La.), Sen. Dean Heller (R-Nev.), and Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.).

Since its introduction in mid September, the bill has undergone at least four published revisions, including providing additional funding to Maine and Alaska in an effort to flip Sen. Collins and Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) to the yes column. Both were no votes that helped kill a previous ACA repeal and replace effort.

“The fact is, Maine still loses money under whichever version of the Graham-Cassidy bill we consider because the bill uses what could be described as a ‘give with one hand, take with the other’ distribution model” to maintain the budget neutrality of the Medicaid block grants sent to states, Sen. Collins said. “Huge Medicaid cuts down the road more than offset any short-term influx of money.”

Sen. Collins’ opposition came on the heels of a damaging analysis from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). The preliminary analysis looked at an earlier version of the bill and found that the number of people with comprehensive health insurance would be reduced by millions and the impact would be particularly large starting in 2020, when the bill would make changes to Medicaid funding and the nongroup insurance market.

Since Senate Republicans are using the budget reconciliation process to pass this legislation, they only need 50 votes to pass the legislation, with Vice President Mike Pence providing the tie-breaking vote. But with a slim 52-seat majority, there was little margin for error. Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) had already announced his opposition to the Graham-Cassidy bill on Sept. 22, primarily on process grounds.

“We should not be content to pass health care legislation on a party-line basis, as Democrats did when they rammed Obamacare through Congress in 2009. If we do, our success could be as short-lived as theirs, when the political winds shift, as they regularly do,” Sen. McCain said in a statement. “The issue is too important, and too many lives are at risk, for us to leave the American people guessing from one election to the next whether and how they will acquire health insurance. A bill of this impact requires a bipartisan approach.”

He praised the work of Senate Health, Education, Labor & Pensions Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) and Ranking Member Patty Murray (D-Wash.), who have been working together on a small, focused package aimed at stabilizing the individual insurance market.

“Senators Alexander and Murray have been negotiating in good faith to fix some of the problems with Obamacare,” Sen. McCain said. “But I fear that the prospect of one last attempt at a strictly Republican bill has left the impression that their efforts cannot succeed. I hope they will resume their work should this last attempt at a partisan solution fail.”

Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) also came out publicly against the Graham-Cassidy bill, though his opposition stems from it not going far enough in repealing elements of the ACA.

During a Sept. 25 Senate Finance Committee hearing on the Graham-Cassidy bill, Teresa Miller, acting secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, testified that the real problem – the cost of health care – is getting pushed aside as everyone focuses on the coverage issue.

“This whole debate, for the last several years, has been about coverage and we haven’t been talking about the cost of health care,” Ms. Miller told the committee. “At the end of the day, insurance is a reflection of the cost of health care. So if we don’t have a debate in this county and discussion about how we get at the underlying cost of care, we have a major problem. That’s really the debate we should be having.”

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has not signaled whether he would still bring Graham-Cassidy to a vote, given that it appears not to have the votes needed for passage. If he chooses to move forward with the bill, the vote would need to happen before the end of the day on Sept. 30 to use the budget reconciliation process and gain passage with a simple majority.

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) became the third GOP senator to confirm a no vote on the latest Republican attempt to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA), a move that likely seals the bill’s fate.