User login

Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome

To the Editor:

A 55-year-old man presented with hyperpigmented brown macules on the lips, hands, and fingertips of 6 years’ duration. The spots were persistent, asymptomatic, and had not changed in size. The patient denied a history of alopecia or dystrophic nails. He also denied a family history of similar skin findings. He had no personal history of cancer and a colonoscopy performed 5 years prior revealed no notable abnormalities. His medications included amlodipine and hydrocodone-acetaminophen. His mother died of “abdominal bleeding” at 74 years of age and his father died of a brain tumor at 64 years of age. Physical examination demonstrated numerous well-defined, dark brown macules of variable size distributed on the lower and upper mucosal lips (Figure 1A), buccal mucosa, hard palate, and gingiva, as well as the dorsal aspect of the fingers (Figure 1B) and volar aspect of the fingertips (Figure 1C).

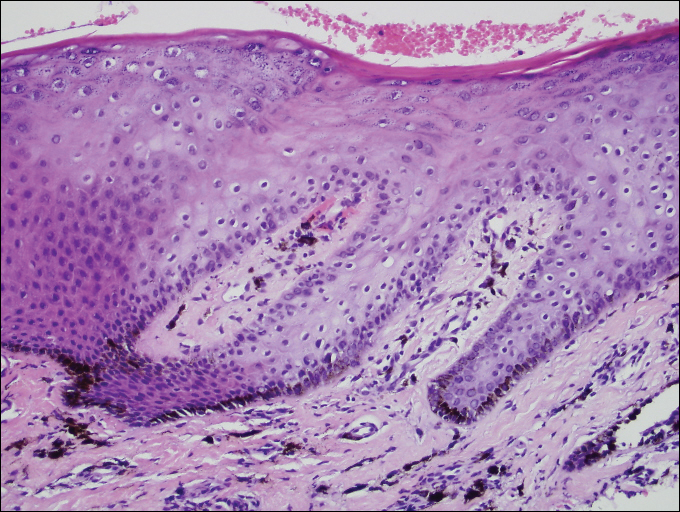

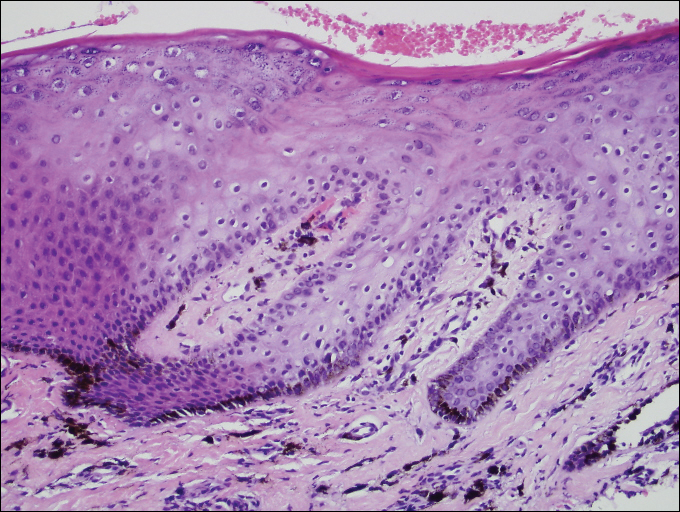

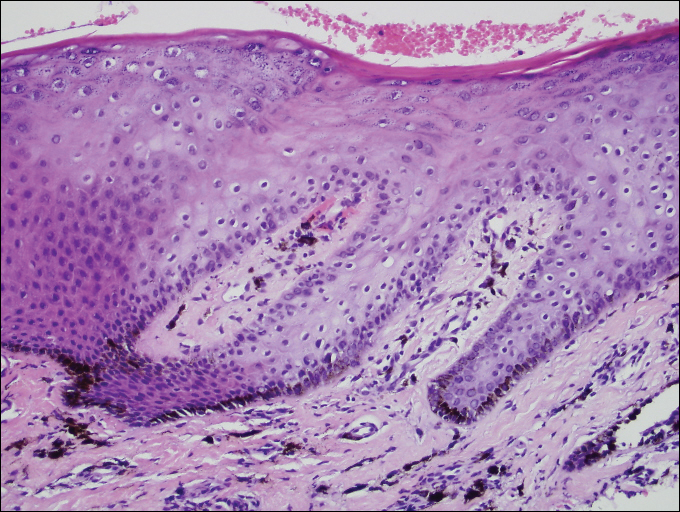

A shave biopsy of a dark brown macule from the lower lip (Figure 2) was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed pigmentation of the basal layer of the epidermis with pigment-laden cells in the dermis immediately deep to the surface epithelium. Immunoperoxidase stains showed a normal number and distribution of melanocytes.

A diagnosis of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome (LHS) was made given the age of onset; distribution of pigmentation; and lack of pathologic colonoscopic findings, personal history of cancer, or gastrointestinal tract symptoms.

Benign hyperpigmentation of the lips and fingers has been reported.1 The average age of onset of LHS is 52 years, and it typically is diagnosed in white adults.1,2 In LHS, pigmentation is most commonly distributed on the lips, especially the lower lips and oral mucosa.2 Pigmentation of the nails in the form of longitudinal melanonychia is present in approximately half of cases.2,3 There also may be pigmentation of the neck; thorax; abdomen; and acral surfaces, especially the fingertips.1-3 Rarely, pigmented macules can occur on the genitalia or sclera.1,2 Unlike Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, the diagnosis of LHS does not result from a germline mutation and carries no risk of gastrointestinal polyposis or internal malignancy.3,4 The histopathology of a pigmented macule of LHS shows a normal number and morphology of melanocytes. Epidermal basement membrane pigmentation is common, with pigment-laden macrophages evident in the papillary dermis.3

RELATED ARTICLE: Asymptomatic Lower Lip Hyperpigmentation From Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome

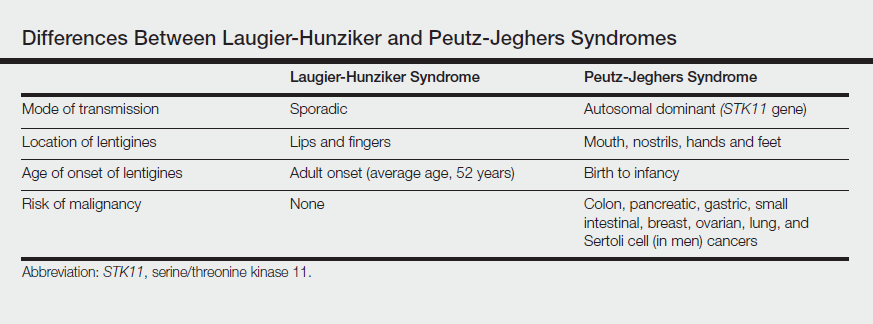

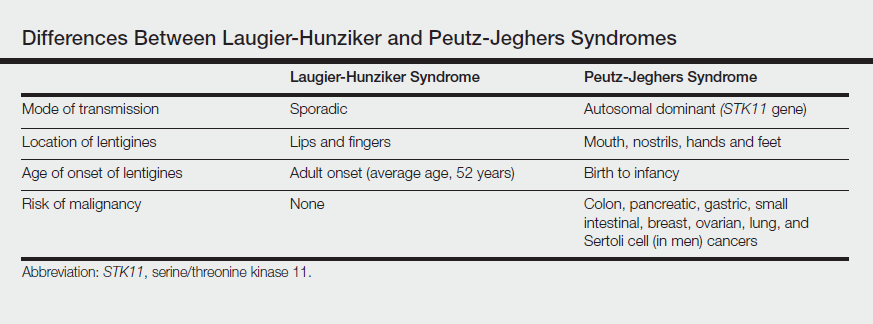

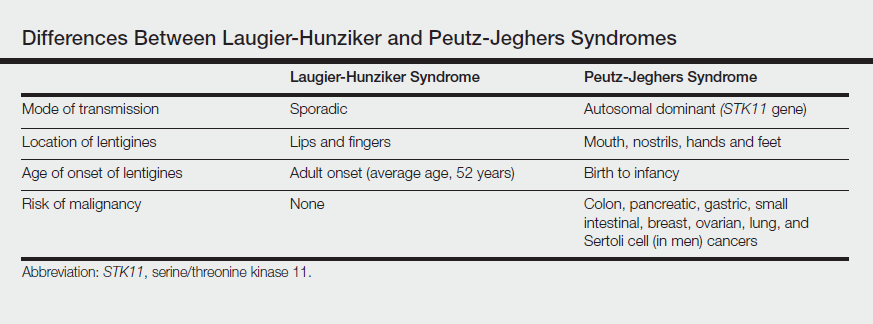

The differential diagnosis of multiple lentigines is broad and includes Peutz-Jeghers syndrome; LEOPARD (lentigines, electrocardiographic conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, deafness) syndrome; Carney complexes, including LAMB (lentigines, atrial myxoma, mucocutaneous myxoma, blue nevi) and NAME (nevi, atrial myxoma, myxoid neurofibroma, ephelide) syndromes5; primary adrenocortical insufficiency (Addison disease); and idiopathic melanoplakia.2 Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, an autosomal-dominant syndrome with mucocutaneous lentigines, has a similar clinical appearance to LHS; therefore, it is necessary to exclude this diagnosis due to its association with intestinal hamartomatous polyps and internal malignancies (Table).3,6,7

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is characterized by mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation and intestinal hamartomatous polyposis and is associated with internal malignancies of the colon, breast, pancreas, stomach, small intestines, ovaries, lung, and Sertoli cells in men.6,7 Associated gastrointestinal tract malignancies in descending order of frequency are colon (39%), pancreatic (36%), gastric (29%), and small intestine (13%).1 It is caused by a germ line mutation of the serine/threonine kinase 11 gene, STK11. Although the appearance and distribution of the mucocutaneous lentigines is similar to individuals with LHS, by contrast the lentiginosis in individuals with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is present from birth or develops during infancy.6 Aggressive cancer screening guidelines aid in early detection and begin at 8 years of age with a baseline colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy; future screening is dictated by the presence or absence of polyps. If no polyps are detected at 8 years of age, a colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy are repeated at 18 years of age and then every 3 years until 50 years of age.8

In an adult patient, the diagnosis of LHS can be made clinically and a correct diagnosis prevents frequent and unpleasant gastrointestinal tract cancer screening examinations. Lampe et al2 described a man with LHS who was incorrectly diagnosed with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and experienced a colonic perforation as a complication of a screening colonoscopy. Their case report underscores the importance of making the correct diagnosis of LHS to avoid undertaking unnecessary aggressive cancer screening regimens.2

Although LHS is a benign condition that does not require treatment, Q-switched alexandrite or erbium:YAG laser therapy has been shown to improve the pigmentary findings associated with LHS.9,10 It has been suggested that LHS should be renamed Laugier-Hunziker pigmentation2 or mucocutaneous lentiginosis of Laugier and Hunziker1 to differentiate LHS as simply a disorder of pigmentation rather than a potentially morbid genetic defect, as in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

- Moore RT, Chae KA, Rhodes AR. Laugier and Hunziker pigmentation: a lentiginous proliferation of melanocytes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S70-S74.

- Lampe AK, Hampton PJ, Woodford-Richens K, et al. Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome: an important differential diagnosis for Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. J Med Genet. 2003;40:E77.

- Baran R. Longitudinal melanotic streaks as a clue for Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1148-1149.

- Grimes P, Nordlund JJ, Pandya AG, et al. Increasing our understanding of pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5 suppl 2):S255-S261.

- Bertherat J. Carney complex (CNC). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:21.

- Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersemette AC, et al. Very high risk of cancer in Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1447-1453.

- Brosens LA, van Hattem WA, Jansen M, et al. Gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:29-46.

- Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

- Zuo YG, Ma DL, Jin HZ, et al. Treatment of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome with the Q-switched alexandrite laser in 22 Chinese patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:125-130.

- Ergun S, Saruhanog˘lu A, Migliari DA, et al. Refractory pigmentation associated with Laugier-Hunziker syndrome following Er:YAG laser treatment [published online December 3, 2013]. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:561040.

To the Editor:

A 55-year-old man presented with hyperpigmented brown macules on the lips, hands, and fingertips of 6 years’ duration. The spots were persistent, asymptomatic, and had not changed in size. The patient denied a history of alopecia or dystrophic nails. He also denied a family history of similar skin findings. He had no personal history of cancer and a colonoscopy performed 5 years prior revealed no notable abnormalities. His medications included amlodipine and hydrocodone-acetaminophen. His mother died of “abdominal bleeding” at 74 years of age and his father died of a brain tumor at 64 years of age. Physical examination demonstrated numerous well-defined, dark brown macules of variable size distributed on the lower and upper mucosal lips (Figure 1A), buccal mucosa, hard palate, and gingiva, as well as the dorsal aspect of the fingers (Figure 1B) and volar aspect of the fingertips (Figure 1C).

A shave biopsy of a dark brown macule from the lower lip (Figure 2) was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed pigmentation of the basal layer of the epidermis with pigment-laden cells in the dermis immediately deep to the surface epithelium. Immunoperoxidase stains showed a normal number and distribution of melanocytes.

A diagnosis of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome (LHS) was made given the age of onset; distribution of pigmentation; and lack of pathologic colonoscopic findings, personal history of cancer, or gastrointestinal tract symptoms.

Benign hyperpigmentation of the lips and fingers has been reported.1 The average age of onset of LHS is 52 years, and it typically is diagnosed in white adults.1,2 In LHS, pigmentation is most commonly distributed on the lips, especially the lower lips and oral mucosa.2 Pigmentation of the nails in the form of longitudinal melanonychia is present in approximately half of cases.2,3 There also may be pigmentation of the neck; thorax; abdomen; and acral surfaces, especially the fingertips.1-3 Rarely, pigmented macules can occur on the genitalia or sclera.1,2 Unlike Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, the diagnosis of LHS does not result from a germline mutation and carries no risk of gastrointestinal polyposis or internal malignancy.3,4 The histopathology of a pigmented macule of LHS shows a normal number and morphology of melanocytes. Epidermal basement membrane pigmentation is common, with pigment-laden macrophages evident in the papillary dermis.3

RELATED ARTICLE: Asymptomatic Lower Lip Hyperpigmentation From Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome

The differential diagnosis of multiple lentigines is broad and includes Peutz-Jeghers syndrome; LEOPARD (lentigines, electrocardiographic conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, deafness) syndrome; Carney complexes, including LAMB (lentigines, atrial myxoma, mucocutaneous myxoma, blue nevi) and NAME (nevi, atrial myxoma, myxoid neurofibroma, ephelide) syndromes5; primary adrenocortical insufficiency (Addison disease); and idiopathic melanoplakia.2 Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, an autosomal-dominant syndrome with mucocutaneous lentigines, has a similar clinical appearance to LHS; therefore, it is necessary to exclude this diagnosis due to its association with intestinal hamartomatous polyps and internal malignancies (Table).3,6,7

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is characterized by mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation and intestinal hamartomatous polyposis and is associated with internal malignancies of the colon, breast, pancreas, stomach, small intestines, ovaries, lung, and Sertoli cells in men.6,7 Associated gastrointestinal tract malignancies in descending order of frequency are colon (39%), pancreatic (36%), gastric (29%), and small intestine (13%).1 It is caused by a germ line mutation of the serine/threonine kinase 11 gene, STK11. Although the appearance and distribution of the mucocutaneous lentigines is similar to individuals with LHS, by contrast the lentiginosis in individuals with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is present from birth or develops during infancy.6 Aggressive cancer screening guidelines aid in early detection and begin at 8 years of age with a baseline colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy; future screening is dictated by the presence or absence of polyps. If no polyps are detected at 8 years of age, a colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy are repeated at 18 years of age and then every 3 years until 50 years of age.8

In an adult patient, the diagnosis of LHS can be made clinically and a correct diagnosis prevents frequent and unpleasant gastrointestinal tract cancer screening examinations. Lampe et al2 described a man with LHS who was incorrectly diagnosed with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and experienced a colonic perforation as a complication of a screening colonoscopy. Their case report underscores the importance of making the correct diagnosis of LHS to avoid undertaking unnecessary aggressive cancer screening regimens.2

Although LHS is a benign condition that does not require treatment, Q-switched alexandrite or erbium:YAG laser therapy has been shown to improve the pigmentary findings associated with LHS.9,10 It has been suggested that LHS should be renamed Laugier-Hunziker pigmentation2 or mucocutaneous lentiginosis of Laugier and Hunziker1 to differentiate LHS as simply a disorder of pigmentation rather than a potentially morbid genetic defect, as in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

To the Editor:

A 55-year-old man presented with hyperpigmented brown macules on the lips, hands, and fingertips of 6 years’ duration. The spots were persistent, asymptomatic, and had not changed in size. The patient denied a history of alopecia or dystrophic nails. He also denied a family history of similar skin findings. He had no personal history of cancer and a colonoscopy performed 5 years prior revealed no notable abnormalities. His medications included amlodipine and hydrocodone-acetaminophen. His mother died of “abdominal bleeding” at 74 years of age and his father died of a brain tumor at 64 years of age. Physical examination demonstrated numerous well-defined, dark brown macules of variable size distributed on the lower and upper mucosal lips (Figure 1A), buccal mucosa, hard palate, and gingiva, as well as the dorsal aspect of the fingers (Figure 1B) and volar aspect of the fingertips (Figure 1C).

A shave biopsy of a dark brown macule from the lower lip (Figure 2) was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed pigmentation of the basal layer of the epidermis with pigment-laden cells in the dermis immediately deep to the surface epithelium. Immunoperoxidase stains showed a normal number and distribution of melanocytes.

A diagnosis of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome (LHS) was made given the age of onset; distribution of pigmentation; and lack of pathologic colonoscopic findings, personal history of cancer, or gastrointestinal tract symptoms.

Benign hyperpigmentation of the lips and fingers has been reported.1 The average age of onset of LHS is 52 years, and it typically is diagnosed in white adults.1,2 In LHS, pigmentation is most commonly distributed on the lips, especially the lower lips and oral mucosa.2 Pigmentation of the nails in the form of longitudinal melanonychia is present in approximately half of cases.2,3 There also may be pigmentation of the neck; thorax; abdomen; and acral surfaces, especially the fingertips.1-3 Rarely, pigmented macules can occur on the genitalia or sclera.1,2 Unlike Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, the diagnosis of LHS does not result from a germline mutation and carries no risk of gastrointestinal polyposis or internal malignancy.3,4 The histopathology of a pigmented macule of LHS shows a normal number and morphology of melanocytes. Epidermal basement membrane pigmentation is common, with pigment-laden macrophages evident in the papillary dermis.3

RELATED ARTICLE: Asymptomatic Lower Lip Hyperpigmentation From Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome

The differential diagnosis of multiple lentigines is broad and includes Peutz-Jeghers syndrome; LEOPARD (lentigines, electrocardiographic conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of genitalia, retardation of growth, deafness) syndrome; Carney complexes, including LAMB (lentigines, atrial myxoma, mucocutaneous myxoma, blue nevi) and NAME (nevi, atrial myxoma, myxoid neurofibroma, ephelide) syndromes5; primary adrenocortical insufficiency (Addison disease); and idiopathic melanoplakia.2 Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, an autosomal-dominant syndrome with mucocutaneous lentigines, has a similar clinical appearance to LHS; therefore, it is necessary to exclude this diagnosis due to its association with intestinal hamartomatous polyps and internal malignancies (Table).3,6,7

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is characterized by mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation and intestinal hamartomatous polyposis and is associated with internal malignancies of the colon, breast, pancreas, stomach, small intestines, ovaries, lung, and Sertoli cells in men.6,7 Associated gastrointestinal tract malignancies in descending order of frequency are colon (39%), pancreatic (36%), gastric (29%), and small intestine (13%).1 It is caused by a germ line mutation of the serine/threonine kinase 11 gene, STK11. Although the appearance and distribution of the mucocutaneous lentigines is similar to individuals with LHS, by contrast the lentiginosis in individuals with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is present from birth or develops during infancy.6 Aggressive cancer screening guidelines aid in early detection and begin at 8 years of age with a baseline colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy; future screening is dictated by the presence or absence of polyps. If no polyps are detected at 8 years of age, a colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy are repeated at 18 years of age and then every 3 years until 50 years of age.8

In an adult patient, the diagnosis of LHS can be made clinically and a correct diagnosis prevents frequent and unpleasant gastrointestinal tract cancer screening examinations. Lampe et al2 described a man with LHS who was incorrectly diagnosed with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and experienced a colonic perforation as a complication of a screening colonoscopy. Their case report underscores the importance of making the correct diagnosis of LHS to avoid undertaking unnecessary aggressive cancer screening regimens.2

Although LHS is a benign condition that does not require treatment, Q-switched alexandrite or erbium:YAG laser therapy has been shown to improve the pigmentary findings associated with LHS.9,10 It has been suggested that LHS should be renamed Laugier-Hunziker pigmentation2 or mucocutaneous lentiginosis of Laugier and Hunziker1 to differentiate LHS as simply a disorder of pigmentation rather than a potentially morbid genetic defect, as in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

- Moore RT, Chae KA, Rhodes AR. Laugier and Hunziker pigmentation: a lentiginous proliferation of melanocytes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S70-S74.

- Lampe AK, Hampton PJ, Woodford-Richens K, et al. Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome: an important differential diagnosis for Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. J Med Genet. 2003;40:E77.

- Baran R. Longitudinal melanotic streaks as a clue for Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1148-1149.

- Grimes P, Nordlund JJ, Pandya AG, et al. Increasing our understanding of pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5 suppl 2):S255-S261.

- Bertherat J. Carney complex (CNC). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:21.

- Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersemette AC, et al. Very high risk of cancer in Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1447-1453.

- Brosens LA, van Hattem WA, Jansen M, et al. Gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:29-46.

- Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

- Zuo YG, Ma DL, Jin HZ, et al. Treatment of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome with the Q-switched alexandrite laser in 22 Chinese patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:125-130.

- Ergun S, Saruhanog˘lu A, Migliari DA, et al. Refractory pigmentation associated with Laugier-Hunziker syndrome following Er:YAG laser treatment [published online December 3, 2013]. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:561040.

- Moore RT, Chae KA, Rhodes AR. Laugier and Hunziker pigmentation: a lentiginous proliferation of melanocytes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(5 suppl):S70-S74.

- Lampe AK, Hampton PJ, Woodford-Richens K, et al. Laugier-Hunziker Syndrome: an important differential diagnosis for Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. J Med Genet. 2003;40:E77.

- Baran R. Longitudinal melanotic streaks as a clue for Laugier-Hunziker syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1148-1149.

- Grimes P, Nordlund JJ, Pandya AG, et al. Increasing our understanding of pigmentary disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(5 suppl 2):S255-S261.

- Bertherat J. Carney complex (CNC). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:21.

- Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersemette AC, et al. Very high risk of cancer in Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1447-1453.

- Brosens LA, van Hattem WA, Jansen M, et al. Gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:29-46.

- Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

- Zuo YG, Ma DL, Jin HZ, et al. Treatment of Laugier-Hunziker syndrome with the Q-switched alexandrite laser in 22 Chinese patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:125-130.

- Ergun S, Saruhanog˘lu A, Migliari DA, et al. Refractory pigmentation associated with Laugier-Hunziker syndrome following Er:YAG laser treatment [published online December 3, 2013]. Case Rep Dent. 2013;2013:561040.

Practice Points

- Laugier-Hunziker syndrome (LHS) comprises benign mucosal pigmentation in the absence of gastrointestinal pathology.

- Differentiating LHS from Peutz-Jeghers syndrome can prevent unnecessary aggressive cancer screening protocols.

- The average age of onset of LHS is 52 years and typically occurs in white adults.

- Pigmentation in LHS is most commonly distributed on the lower lips and oral mucosa.

Robot-assisted abdominoperineal resection outperforms open or laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancers

MADRID – The automaton uprising continues: Robot-assisted abdominoperineal resection (APR) can be safely performed in patients with rectal cancers within 5 cm of the anal verge, with surgical results equivalent to those seen with open or laparoscopic APR, investigators say.

Robot-assisted procedures were associated with a significantly lower rate of postoperative complications and with faster functional recovery than either laparoscopic or open surgery in a randomized trial, reported Jianmin Xu, MD, PhD., from Fudan University in Shanghai, China, and colleagues in a scientific poster presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

“Retrospective studies have showed that robotic surgery was better than laparoscopic surgery in ensuring radical resection, reducing complications, and promoting recovery. However, there is no clinical trial reported for robotic surgery for rectal cancer. Thus, we conduct this randomized controlled trial to compare the safety and efficacy of robotic, laparoscopic, and open surgery for low rectal cancer,” they wrote.

Dr. Xu and colleagues enrolled 506 patients from 18 to 75 years of age with clinical stage T1 to T3 cancers within 5 cm of the anal verge and no distant metastases and randomly assigned them to resection with either a robot-assisted, laparoscopic, or open APR technique. Three of the 506 patients randomized did not undergo resection, leaving 503 for the per-protocol analysis presented here.

For the primary endpoint of complications rates within 30 days following surgery, the investigators found that patients assigned to robotic-assisted surgery (173 patients) had a total complication rate of 10.4%, compared with 18.8% for 176 patients assigned to laparoscopy (P = .027), and 26% for 154 assigned to open APR (P less than .001). The latter group included four patients assigned to laparoscopy whose procedures were converted to open surgery.

Among patients without complications, robot-assisted procedures were also associated with faster recovery, as measured by days to first flatus, at a median of 1 vs. 2 for laparoscopy and 3 for open procedures (P less than .001 for robots vs. each other surgery type). The robotic surgery was also significantly associated with fewer days to first automatic urination (median 2 vs. 4 for each of the other procedures; P less than .001), and with fewer days to discharge (median 5 vs. 7 for the other procedures; P less than .001).

"These are excellent postoperative complication rates reported, especially for the robotic treatment group, commented Thomas Gruenberger, MD, an oncologic surgeon at Rudolf Hospital in Vienna, in a poster discussion session.

“We all are now favoring laparoscopic surgery for these kinds of patients. The robot is a nice thing to have; however, we cannot use it in every hospital because it’s still quite expensive,” he said.

“We require – and this is a secondary endpoint of the study – long-term follow-up for local and distant outcomes,” he added,

The investigators did not report a funding source. All authors declared having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gruenberger disclosed research funding, speakers bureau participation, and/or advisory roles with several companies.

MADRID – The automaton uprising continues: Robot-assisted abdominoperineal resection (APR) can be safely performed in patients with rectal cancers within 5 cm of the anal verge, with surgical results equivalent to those seen with open or laparoscopic APR, investigators say.

Robot-assisted procedures were associated with a significantly lower rate of postoperative complications and with faster functional recovery than either laparoscopic or open surgery in a randomized trial, reported Jianmin Xu, MD, PhD., from Fudan University in Shanghai, China, and colleagues in a scientific poster presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

“Retrospective studies have showed that robotic surgery was better than laparoscopic surgery in ensuring radical resection, reducing complications, and promoting recovery. However, there is no clinical trial reported for robotic surgery for rectal cancer. Thus, we conduct this randomized controlled trial to compare the safety and efficacy of robotic, laparoscopic, and open surgery for low rectal cancer,” they wrote.

Dr. Xu and colleagues enrolled 506 patients from 18 to 75 years of age with clinical stage T1 to T3 cancers within 5 cm of the anal verge and no distant metastases and randomly assigned them to resection with either a robot-assisted, laparoscopic, or open APR technique. Three of the 506 patients randomized did not undergo resection, leaving 503 for the per-protocol analysis presented here.

For the primary endpoint of complications rates within 30 days following surgery, the investigators found that patients assigned to robotic-assisted surgery (173 patients) had a total complication rate of 10.4%, compared with 18.8% for 176 patients assigned to laparoscopy (P = .027), and 26% for 154 assigned to open APR (P less than .001). The latter group included four patients assigned to laparoscopy whose procedures were converted to open surgery.

Among patients without complications, robot-assisted procedures were also associated with faster recovery, as measured by days to first flatus, at a median of 1 vs. 2 for laparoscopy and 3 for open procedures (P less than .001 for robots vs. each other surgery type). The robotic surgery was also significantly associated with fewer days to first automatic urination (median 2 vs. 4 for each of the other procedures; P less than .001), and with fewer days to discharge (median 5 vs. 7 for the other procedures; P less than .001).

"These are excellent postoperative complication rates reported, especially for the robotic treatment group, commented Thomas Gruenberger, MD, an oncologic surgeon at Rudolf Hospital in Vienna, in a poster discussion session.

“We all are now favoring laparoscopic surgery for these kinds of patients. The robot is a nice thing to have; however, we cannot use it in every hospital because it’s still quite expensive,” he said.

“We require – and this is a secondary endpoint of the study – long-term follow-up for local and distant outcomes,” he added,

The investigators did not report a funding source. All authors declared having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gruenberger disclosed research funding, speakers bureau participation, and/or advisory roles with several companies.

MADRID – The automaton uprising continues: Robot-assisted abdominoperineal resection (APR) can be safely performed in patients with rectal cancers within 5 cm of the anal verge, with surgical results equivalent to those seen with open or laparoscopic APR, investigators say.

Robot-assisted procedures were associated with a significantly lower rate of postoperative complications and with faster functional recovery than either laparoscopic or open surgery in a randomized trial, reported Jianmin Xu, MD, PhD., from Fudan University in Shanghai, China, and colleagues in a scientific poster presented at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

“Retrospective studies have showed that robotic surgery was better than laparoscopic surgery in ensuring radical resection, reducing complications, and promoting recovery. However, there is no clinical trial reported for robotic surgery for rectal cancer. Thus, we conduct this randomized controlled trial to compare the safety and efficacy of robotic, laparoscopic, and open surgery for low rectal cancer,” they wrote.

Dr. Xu and colleagues enrolled 506 patients from 18 to 75 years of age with clinical stage T1 to T3 cancers within 5 cm of the anal verge and no distant metastases and randomly assigned them to resection with either a robot-assisted, laparoscopic, or open APR technique. Three of the 506 patients randomized did not undergo resection, leaving 503 for the per-protocol analysis presented here.

For the primary endpoint of complications rates within 30 days following surgery, the investigators found that patients assigned to robotic-assisted surgery (173 patients) had a total complication rate of 10.4%, compared with 18.8% for 176 patients assigned to laparoscopy (P = .027), and 26% for 154 assigned to open APR (P less than .001). The latter group included four patients assigned to laparoscopy whose procedures were converted to open surgery.

Among patients without complications, robot-assisted procedures were also associated with faster recovery, as measured by days to first flatus, at a median of 1 vs. 2 for laparoscopy and 3 for open procedures (P less than .001 for robots vs. each other surgery type). The robotic surgery was also significantly associated with fewer days to first automatic urination (median 2 vs. 4 for each of the other procedures; P less than .001), and with fewer days to discharge (median 5 vs. 7 for the other procedures; P less than .001).

"These are excellent postoperative complication rates reported, especially for the robotic treatment group, commented Thomas Gruenberger, MD, an oncologic surgeon at Rudolf Hospital in Vienna, in a poster discussion session.

“We all are now favoring laparoscopic surgery for these kinds of patients. The robot is a nice thing to have; however, we cannot use it in every hospital because it’s still quite expensive,” he said.

“We require – and this is a secondary endpoint of the study – long-term follow-up for local and distant outcomes,” he added,

The investigators did not report a funding source. All authors declared having no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gruenberger disclosed research funding, speakers bureau participation, and/or advisory roles with several companies.

AT ESMO 2017

Launch of adalimumab biosimilar Amjevita postponed

Amgen, maker of the adalimumab biosimilar Amjevita (adalimumab-atto) has reached an agreement with AbbVie, manufacturer of the originator adalimumab Humira, that halts marketing of Amjevita in the United States until 2023 and in Europe until 2018, according to a company statement.

The deal between the two manufacturers settles a patent infringement lawsuit that AbbVie brought against Amgen after it received Food and Drug Administration approval in September 2016 for seven of Humira’s nine indications: rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, plaque psoriasis, and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Amjevita is not approved for two of Humira’s indications, hidradenitis suppurativa and uveitis.

Amgen said in its statement that AbbVie will grant patent licenses for the use and sale of Amjevita worldwide, on a country-by-country basis, with current expectations that marketing will begin in Europe on Oct. 16, 2018, and in the United States on Jan. 31, 2023. Amjevita is named Amgevita in Europe.

Amgen, maker of the adalimumab biosimilar Amjevita (adalimumab-atto) has reached an agreement with AbbVie, manufacturer of the originator adalimumab Humira, that halts marketing of Amjevita in the United States until 2023 and in Europe until 2018, according to a company statement.

The deal between the two manufacturers settles a patent infringement lawsuit that AbbVie brought against Amgen after it received Food and Drug Administration approval in September 2016 for seven of Humira’s nine indications: rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, plaque psoriasis, and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Amjevita is not approved for two of Humira’s indications, hidradenitis suppurativa and uveitis.

Amgen said in its statement that AbbVie will grant patent licenses for the use and sale of Amjevita worldwide, on a country-by-country basis, with current expectations that marketing will begin in Europe on Oct. 16, 2018, and in the United States on Jan. 31, 2023. Amjevita is named Amgevita in Europe.

Amgen, maker of the adalimumab biosimilar Amjevita (adalimumab-atto) has reached an agreement with AbbVie, manufacturer of the originator adalimumab Humira, that halts marketing of Amjevita in the United States until 2023 and in Europe until 2018, according to a company statement.

The deal between the two manufacturers settles a patent infringement lawsuit that AbbVie brought against Amgen after it received Food and Drug Administration approval in September 2016 for seven of Humira’s nine indications: rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, plaque psoriasis, and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Amjevita is not approved for two of Humira’s indications, hidradenitis suppurativa and uveitis.

Amgen said in its statement that AbbVie will grant patent licenses for the use and sale of Amjevita worldwide, on a country-by-country basis, with current expectations that marketing will begin in Europe on Oct. 16, 2018, and in the United States on Jan. 31, 2023. Amjevita is named Amgevita in Europe.

Under our noses

If you graduated from medical school after 1990, you may be surprised to learn that there was a time when the typical general pediatrician could go through an entire day of seeing patients and not write a single prescription for a stimulant medication. In fact, he or she could go for several months without writing for any controlled substance.

ADHD is a modern phenomenon. There always have been children with “ants in their pants” who couldn’t sit still. And there always were “daydreamers” who didn’t pay attention in school. But in the 1970s, the number of children who might now be labeled as having ADHD was nowhere near the 11% often quoted for the prevalence in the current pediatric population.

Could there be some genetic selection process that is favoring the birth and survival of hyperactive and distractible children? In the last decade or two, biologists have discovered evolutionary changes in some animals occurring at pace far faster than had been previously imagined. However, a Darwinian explanation seems unlikely in the case of the emergence of ADHD.

Could it be a diet laced with high fructose sugars or artificial dyes and food coloring? While there continues to be a significant number of parents whose anecdotal observations point to a relationship between diet and behavior, to date controlled studies have not supported a dietary cause for the ADHD phenomenon.

Within a few years of beginning my dual careers as parent and pediatrician, I began to notice that children who were sleep deprived often were distractible and inattentive. Some also were hyperactive, an observation that initially seemed counterintuitive. Over the ensuing four decades, I have become more convinced that a substantial driver of the emergence of the ADHD phenomenon is the fact that the North American lifestyle places sleep so far down on its priority list that a significant percentage of both the pediatric and adult populations are sleep deprived.

I freely admit that my initial anecdotal observations have evolved to the point of an obsession. Of course, I look at the data that show that children are getting less sleep than they did a century ago and suspect that this decline must somehow be reflected in their behavior (“Never enough sleep: A brief history of sleep recommendations for children” by Matricciani et al. Pediatrics. 2012 Mar;129[3]:548-56). And, of course, I wonder whether the success and popularity of stimulant medication to treat ADHD is just chance or whether it simply could be waking up a bunch of children who aren’t getting enough sleep.

At times, it has been a lonely several decades, trying to convince parents and other pediatricians that sleep may be the answer. I can’t point to my own research because I have been too busy doing general pediatrics. I can only point to the observations of others that fit into my construct.

You can imagine the warm glow that swept over me when I came across an article in the Washington Post titled “Could some ADHD be a type of sleep disorder? That would fundamentally change how we treat it” (A.E. Cha, Sep. 20, 2017). The studies referred to in the article are not terribly earth shaking. But it was nice to read some quotes in a national newspaper from scientists who share my suspicions about sleep deprivation as a major contributor to the ADHD phenomenon. I instantly felt less lonely.

Unfortunately, it is still a long way from this token recognition in the Washington Post to convincing parents and pediatricians to do the heavy lifting that will be required to undo decades of our society’s sleep-unfriendly norms. It’s so much easier to pull out a prescription pad and write for a stimulant.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

If you graduated from medical school after 1990, you may be surprised to learn that there was a time when the typical general pediatrician could go through an entire day of seeing patients and not write a single prescription for a stimulant medication. In fact, he or she could go for several months without writing for any controlled substance.

ADHD is a modern phenomenon. There always have been children with “ants in their pants” who couldn’t sit still. And there always were “daydreamers” who didn’t pay attention in school. But in the 1970s, the number of children who might now be labeled as having ADHD was nowhere near the 11% often quoted for the prevalence in the current pediatric population.

Could there be some genetic selection process that is favoring the birth and survival of hyperactive and distractible children? In the last decade or two, biologists have discovered evolutionary changes in some animals occurring at pace far faster than had been previously imagined. However, a Darwinian explanation seems unlikely in the case of the emergence of ADHD.

Could it be a diet laced with high fructose sugars or artificial dyes and food coloring? While there continues to be a significant number of parents whose anecdotal observations point to a relationship between diet and behavior, to date controlled studies have not supported a dietary cause for the ADHD phenomenon.

Within a few years of beginning my dual careers as parent and pediatrician, I began to notice that children who were sleep deprived often were distractible and inattentive. Some also were hyperactive, an observation that initially seemed counterintuitive. Over the ensuing four decades, I have become more convinced that a substantial driver of the emergence of the ADHD phenomenon is the fact that the North American lifestyle places sleep so far down on its priority list that a significant percentage of both the pediatric and adult populations are sleep deprived.

I freely admit that my initial anecdotal observations have evolved to the point of an obsession. Of course, I look at the data that show that children are getting less sleep than they did a century ago and suspect that this decline must somehow be reflected in their behavior (“Never enough sleep: A brief history of sleep recommendations for children” by Matricciani et al. Pediatrics. 2012 Mar;129[3]:548-56). And, of course, I wonder whether the success and popularity of stimulant medication to treat ADHD is just chance or whether it simply could be waking up a bunch of children who aren’t getting enough sleep.

At times, it has been a lonely several decades, trying to convince parents and other pediatricians that sleep may be the answer. I can’t point to my own research because I have been too busy doing general pediatrics. I can only point to the observations of others that fit into my construct.

You can imagine the warm glow that swept over me when I came across an article in the Washington Post titled “Could some ADHD be a type of sleep disorder? That would fundamentally change how we treat it” (A.E. Cha, Sep. 20, 2017). The studies referred to in the article are not terribly earth shaking. But it was nice to read some quotes in a national newspaper from scientists who share my suspicions about sleep deprivation as a major contributor to the ADHD phenomenon. I instantly felt less lonely.

Unfortunately, it is still a long way from this token recognition in the Washington Post to convincing parents and pediatricians to do the heavy lifting that will be required to undo decades of our society’s sleep-unfriendly norms. It’s so much easier to pull out a prescription pad and write for a stimulant.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

If you graduated from medical school after 1990, you may be surprised to learn that there was a time when the typical general pediatrician could go through an entire day of seeing patients and not write a single prescription for a stimulant medication. In fact, he or she could go for several months without writing for any controlled substance.

ADHD is a modern phenomenon. There always have been children with “ants in their pants” who couldn’t sit still. And there always were “daydreamers” who didn’t pay attention in school. But in the 1970s, the number of children who might now be labeled as having ADHD was nowhere near the 11% often quoted for the prevalence in the current pediatric population.

Could there be some genetic selection process that is favoring the birth and survival of hyperactive and distractible children? In the last decade or two, biologists have discovered evolutionary changes in some animals occurring at pace far faster than had been previously imagined. However, a Darwinian explanation seems unlikely in the case of the emergence of ADHD.

Could it be a diet laced with high fructose sugars or artificial dyes and food coloring? While there continues to be a significant number of parents whose anecdotal observations point to a relationship between diet and behavior, to date controlled studies have not supported a dietary cause for the ADHD phenomenon.

Within a few years of beginning my dual careers as parent and pediatrician, I began to notice that children who were sleep deprived often were distractible and inattentive. Some also were hyperactive, an observation that initially seemed counterintuitive. Over the ensuing four decades, I have become more convinced that a substantial driver of the emergence of the ADHD phenomenon is the fact that the North American lifestyle places sleep so far down on its priority list that a significant percentage of both the pediatric and adult populations are sleep deprived.

I freely admit that my initial anecdotal observations have evolved to the point of an obsession. Of course, I look at the data that show that children are getting less sleep than they did a century ago and suspect that this decline must somehow be reflected in their behavior (“Never enough sleep: A brief history of sleep recommendations for children” by Matricciani et al. Pediatrics. 2012 Mar;129[3]:548-56). And, of course, I wonder whether the success and popularity of stimulant medication to treat ADHD is just chance or whether it simply could be waking up a bunch of children who aren’t getting enough sleep.

At times, it has been a lonely several decades, trying to convince parents and other pediatricians that sleep may be the answer. I can’t point to my own research because I have been too busy doing general pediatrics. I can only point to the observations of others that fit into my construct.

You can imagine the warm glow that swept over me when I came across an article in the Washington Post titled “Could some ADHD be a type of sleep disorder? That would fundamentally change how we treat it” (A.E. Cha, Sep. 20, 2017). The studies referred to in the article are not terribly earth shaking. But it was nice to read some quotes in a national newspaper from scientists who share my suspicions about sleep deprivation as a major contributor to the ADHD phenomenon. I instantly felt less lonely.

Unfortunately, it is still a long way from this token recognition in the Washington Post to convincing parents and pediatricians to do the heavy lifting that will be required to undo decades of our society’s sleep-unfriendly norms. It’s so much easier to pull out a prescription pad and write for a stimulant.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Transoral robotic surgery assessed for oral lesions

A single-arm study is being conducted at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, to assess transoral robotic surgery (TORS) for oral and laryngopharyngeal benign and malignant lesions using the da Vinci Robotic Surgical System.

The study started in 2007, and the estimated completion date is December 2020. Investigators hope to enroll 360 adults.

Patients are scheduled for regular postop visits to assess quality of life and other matters. Those unable to return to Ohio State University are contacted by phone or provided with the questionnaire by mail.

A single-arm study is being conducted at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, to assess transoral robotic surgery (TORS) for oral and laryngopharyngeal benign and malignant lesions using the da Vinci Robotic Surgical System.

The study started in 2007, and the estimated completion date is December 2020. Investigators hope to enroll 360 adults.

Patients are scheduled for regular postop visits to assess quality of life and other matters. Those unable to return to Ohio State University are contacted by phone or provided with the questionnaire by mail.

A single-arm study is being conducted at the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, to assess transoral robotic surgery (TORS) for oral and laryngopharyngeal benign and malignant lesions using the da Vinci Robotic Surgical System.

The study started in 2007, and the estimated completion date is December 2020. Investigators hope to enroll 360 adults.

Patients are scheduled for regular postop visits to assess quality of life and other matters. Those unable to return to Ohio State University are contacted by phone or provided with the questionnaire by mail.

‘Without clinical prodrome’

For the most part pediatricians are insulated from death. Our little patients are surprisingly resilient. Once past that anxiety-provoking transition from placental dependence to air breathing, children will thrive in an environment that includes immunizations, potable water, and adequate nutrition. But pediatric deaths do occur infrequently in North America, and they are particularly unsettling to us because we are so unaccustomed to processing the emotions that swirl around the end of life. Did I miss something at the last health maintenance visit? Should I have taken more seriously that call last week about what sounded like a simple viral prodrome? Should I have asked that mother to make an appointment?

Their approach, which has been labeled the Robert’s Program, is particularly appealing because it is careful to address the families’ concerns about their surviving and future children. I found the inclusion of the dead child’s pediatrician and the office of the chief medical examiner in the summation of the investigation especially appealing.

However, I have trouble envisioning how this novel approach, funded by several philanthropic organizations, could be rolled out on a larger scale. Here in Maine and in many other smaller cash-strapped communities, the medical examiner’s office is overburdened with opioid overdoses and traumatic deaths. The police and sheriffs’ departments may lack sufficient training and experience to do careful scene investigations.

In reviewing the summary of the 17 deaths included in the article, I was struck by the inclusion of 3 cases in which the final cause of death was meningitis or encephalitis “without clinical prodrome.”

While a thorough investigation did eventually unearth the cause of death in these three cases, it is in that devilish prodrome that the seeds of guilt can continue to germinate. Parents and physicians will continue to wonder whether someone else with more sensitive antennae might have picked up those early signs of impending disaster. The answer is that there probably wasn’t anyone with better antennae, but there may have been someone with better luck.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

For the most part pediatricians are insulated from death. Our little patients are surprisingly resilient. Once past that anxiety-provoking transition from placental dependence to air breathing, children will thrive in an environment that includes immunizations, potable water, and adequate nutrition. But pediatric deaths do occur infrequently in North America, and they are particularly unsettling to us because we are so unaccustomed to processing the emotions that swirl around the end of life. Did I miss something at the last health maintenance visit? Should I have taken more seriously that call last week about what sounded like a simple viral prodrome? Should I have asked that mother to make an appointment?

Their approach, which has been labeled the Robert’s Program, is particularly appealing because it is careful to address the families’ concerns about their surviving and future children. I found the inclusion of the dead child’s pediatrician and the office of the chief medical examiner in the summation of the investigation especially appealing.

However, I have trouble envisioning how this novel approach, funded by several philanthropic organizations, could be rolled out on a larger scale. Here in Maine and in many other smaller cash-strapped communities, the medical examiner’s office is overburdened with opioid overdoses and traumatic deaths. The police and sheriffs’ departments may lack sufficient training and experience to do careful scene investigations.

In reviewing the summary of the 17 deaths included in the article, I was struck by the inclusion of 3 cases in which the final cause of death was meningitis or encephalitis “without clinical prodrome.”

While a thorough investigation did eventually unearth the cause of death in these three cases, it is in that devilish prodrome that the seeds of guilt can continue to germinate. Parents and physicians will continue to wonder whether someone else with more sensitive antennae might have picked up those early signs of impending disaster. The answer is that there probably wasn’t anyone with better antennae, but there may have been someone with better luck.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

For the most part pediatricians are insulated from death. Our little patients are surprisingly resilient. Once past that anxiety-provoking transition from placental dependence to air breathing, children will thrive in an environment that includes immunizations, potable water, and adequate nutrition. But pediatric deaths do occur infrequently in North America, and they are particularly unsettling to us because we are so unaccustomed to processing the emotions that swirl around the end of life. Did I miss something at the last health maintenance visit? Should I have taken more seriously that call last week about what sounded like a simple viral prodrome? Should I have asked that mother to make an appointment?

Their approach, which has been labeled the Robert’s Program, is particularly appealing because it is careful to address the families’ concerns about their surviving and future children. I found the inclusion of the dead child’s pediatrician and the office of the chief medical examiner in the summation of the investigation especially appealing.

However, I have trouble envisioning how this novel approach, funded by several philanthropic organizations, could be rolled out on a larger scale. Here in Maine and in many other smaller cash-strapped communities, the medical examiner’s office is overburdened with opioid overdoses and traumatic deaths. The police and sheriffs’ departments may lack sufficient training and experience to do careful scene investigations.

In reviewing the summary of the 17 deaths included in the article, I was struck by the inclusion of 3 cases in which the final cause of death was meningitis or encephalitis “without clinical prodrome.”

While a thorough investigation did eventually unearth the cause of death in these three cases, it is in that devilish prodrome that the seeds of guilt can continue to germinate. Parents and physicians will continue to wonder whether someone else with more sensitive antennae might have picked up those early signs of impending disaster. The answer is that there probably wasn’t anyone with better antennae, but there may have been someone with better luck.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Robotic surgery technologies have unique learning curves for trainees

Training surgeons to use robotic technology involves learning curves, and a study has found that robotic technologies have unique learning curve profiles that have implications for the time and number of procedures needed to achieve competence.

Giorgio Mazzon, MD, of the Institute of Urology at University College Hospital, London, and his colleagues reviewed the literature on training surgeons in the use of a variety of technologies for urological procedures. They analyzed learning curves for virtual reality robotic simulators, robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (RALP), robot-assisted radical cystectomy (RARC), and robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) (Curr Urol Rep. 2017 Sep 23;18:89).

RARC learning curves are more rapid than RALP, but this may be due to the fact that most surgeons practice RALP before learning RARC. It is estimated that it takes 21 procedures for operating time to plateau and 30 patients for proper lymph node yield and positive surgical margins of less than 5% to occur (Eur Urol. 2010 Aug;58[2]:197-202).Safety and competence in RAPN is usually defined by operating times, warm ischemic time, positive surgical margin, and complication rates. It has been reported that RAPN can be safely performed with completion of 25-30 cases (Eur Urol. 2010 Jul;58[1]:127-32).The results of the review “should inform trainers and trainees on what outcomes are expected at a given stage of training,” according to the investigators.

They reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Training surgeons to use robotic technology involves learning curves, and a study has found that robotic technologies have unique learning curve profiles that have implications for the time and number of procedures needed to achieve competence.

Giorgio Mazzon, MD, of the Institute of Urology at University College Hospital, London, and his colleagues reviewed the literature on training surgeons in the use of a variety of technologies for urological procedures. They analyzed learning curves for virtual reality robotic simulators, robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (RALP), robot-assisted radical cystectomy (RARC), and robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) (Curr Urol Rep. 2017 Sep 23;18:89).

RARC learning curves are more rapid than RALP, but this may be due to the fact that most surgeons practice RALP before learning RARC. It is estimated that it takes 21 procedures for operating time to plateau and 30 patients for proper lymph node yield and positive surgical margins of less than 5% to occur (Eur Urol. 2010 Aug;58[2]:197-202).Safety and competence in RAPN is usually defined by operating times, warm ischemic time, positive surgical margin, and complication rates. It has been reported that RAPN can be safely performed with completion of 25-30 cases (Eur Urol. 2010 Jul;58[1]:127-32).The results of the review “should inform trainers and trainees on what outcomes are expected at a given stage of training,” according to the investigators.

They reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Training surgeons to use robotic technology involves learning curves, and a study has found that robotic technologies have unique learning curve profiles that have implications for the time and number of procedures needed to achieve competence.

Giorgio Mazzon, MD, of the Institute of Urology at University College Hospital, London, and his colleagues reviewed the literature on training surgeons in the use of a variety of technologies for urological procedures. They analyzed learning curves for virtual reality robotic simulators, robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (RALP), robot-assisted radical cystectomy (RARC), and robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) (Curr Urol Rep. 2017 Sep 23;18:89).

RARC learning curves are more rapid than RALP, but this may be due to the fact that most surgeons practice RALP before learning RARC. It is estimated that it takes 21 procedures for operating time to plateau and 30 patients for proper lymph node yield and positive surgical margins of less than 5% to occur (Eur Urol. 2010 Aug;58[2]:197-202).Safety and competence in RAPN is usually defined by operating times, warm ischemic time, positive surgical margin, and complication rates. It has been reported that RAPN can be safely performed with completion of 25-30 cases (Eur Urol. 2010 Jul;58[1]:127-32).The results of the review “should inform trainers and trainees on what outcomes are expected at a given stage of training,” according to the investigators.

They reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM CURRENT UROLOGY REPORTS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: For virtual reality training programs, recommendations for achieving safety and competence is between 4 and 12 hours of training in a simulator.

Data source: Review of studies of learning curves in robotic urological surgery.

Disclosures: The researchers reported no financial disclosures.

Biophysical properties of HCV evolve over course of infection

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) particles are of lowest density and most infectious early in the course of infection, based on findings from a study of chimeric mice.

Over time, however, viral density became more heterogeneous and infectivity fell, reported Ursula Andreo, PhD, of Rockefeller University, New York, with her coinvestigators. A diet of 10% sucrose, which in rats induces hepatic secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), caused HCV particles to become slightly lower density and more infectious in the mice, the researchers reported. Although the shift was “minor,” it “correlated with a trend toward enhanced triglyceride and cholesterol levels in the same fractions,” they wrote. They recommended studying high-fat diets to determine whether altering the VLDL secretion pathway affects the biophysical properties of HCV. “A high-fat diet might have a more significant impact on the lipoprotein profile in this humanized mouse model,” they wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017 Jul;4[3]:405-17).

Because HCV tends to associate with lipoproteins, it shows a range of buoyant densities in the blood of infected patients. The “entry, replication, and assembly [of the virion] are linked closely to host lipid and lipoprotein metabolism,” wrote Dr. Andreo and her colleagues.

They created an in vivo model to study the buoyant density and infectivity of HCV particles, as well as their interaction with lipoproteins, by grafting human hepatocytes into the livers of immunodeficient mice that were homozygous recessive for fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase. Next, they infected 13 of these chimeric mice with J6-JFH1, an HCV strain that can establish long-term infections in mice that have human liver grafts (Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103[10]:3805-9). The human liver xenograft reconstituted the FAH gene, restoring triglycerides to normal levels in the chimeric mice and creating a suitable “humanlike” model of lipoprotein metabolism, the investigators wrote.

Density fractionation of infectious mouse serum revealed higher infectivity in the low-density fractions soon after infection, which also has been observed in a human liver chimeric mouse model of severe combined immunodeficiency disease, they added. In the HCV model, the human liver grafts were conserved 5 weeks after infection, and the mice had a lower proportion of lighter, infectious HCV particles.

The researchers lacked sufficient material to directly study the composition of virions or detect viral proteins in the various density fractions. However, they determined that apolipoprotein C1 was the lightest fraction and that apolipoprotein E was mainly found in the five lightest fractions. Both these apolipoproteins are “essential factors of HCV infectivity,” and neither redistributed over time, they said. They suggested using immunoelectron microscopy or mass spectrometry to study the nature and infectivity of viral particles further.

In humans, ingesting a high-fat milkshake increases detectable HCV RNA in the VLDL fraction, the researchers noted. In rodents, a sucrose diet also has been found to increase VLDL lipidation and secretion, so they gave five of the infected chimeric mice drinking water containing 10% sucrose. After 5 weeks, these mice had increased infectivity and higher levels of triglycerides and cholesterol, but the effect was small and disappeared after the sucrose was withdrawn.

HCV “circulates as a population of particles of light, as well as dense, buoyant densities, and both are infectious,” the researchers concluded. “Changes in diet, as well as conditions such as fasting and feeding, affect the distribution of HCV buoyant density gradients.”

Funders included the National Institutes of Health and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The investigators disclosed no conflicts.

A hallmark of HCV infection is the association of virus particles with lipoproteins. The HCV virion (lipo-viro particle, LVP) is composed of nucleocapsid and envelope glycoproteins associated with very-low- and low-density lipoproteins, cholesterol, and apolipoproteins. The lipid components determine the size, density, hepatotropism, and infectivity of LVPs and play a role in cell entry, morphogenesis, release, and viral escape mechanisms. LVPs undergo dynamic changes during infection, and dietary triglycerides induce alterations in their biophysical properties and infectivity.

Dr. Andreo and colleagues used humanized Fah–/– mice to analyze the evolution of HCV particles during infection. As previously reported, two viral populations of different densities were detected in mice sera, with higher infectivity observed for the low-density population. The proportions and infectivity of these populations varied during infection, reflecting changes in biochemical features of the virus. Sucrose diet influenced the properties of virus particles; these properties’ changes correlated with a redistribution of triglycerides and cholesterol among lipoproteins.

Changes in biochemical features of the virus during infection represent a fascinating aspect of the structural heterogeneity, which influences HCV infectivity and evolution of the disease. Further studies in experimental models that reproduce the lipoprotein-dependent morphogenesis and release of virus particles, maturation, and intravascular remodeling of HCV-associated lipoproteins would help to develop novel lipid-targeting inhibitors to improve existing therapies.

Agata Budkowska, PhD, is scientific advisor for the department of international affairs at the Institut Pasteur, Paris. She has no conflicts of interest.

A hallmark of HCV infection is the association of virus particles with lipoproteins. The HCV virion (lipo-viro particle, LVP) is composed of nucleocapsid and envelope glycoproteins associated with very-low- and low-density lipoproteins, cholesterol, and apolipoproteins. The lipid components determine the size, density, hepatotropism, and infectivity of LVPs and play a role in cell entry, morphogenesis, release, and viral escape mechanisms. LVPs undergo dynamic changes during infection, and dietary triglycerides induce alterations in their biophysical properties and infectivity.

Dr. Andreo and colleagues used humanized Fah–/– mice to analyze the evolution of HCV particles during infection. As previously reported, two viral populations of different densities were detected in mice sera, with higher infectivity observed for the low-density population. The proportions and infectivity of these populations varied during infection, reflecting changes in biochemical features of the virus. Sucrose diet influenced the properties of virus particles; these properties’ changes correlated with a redistribution of triglycerides and cholesterol among lipoproteins.

Changes in biochemical features of the virus during infection represent a fascinating aspect of the structural heterogeneity, which influences HCV infectivity and evolution of the disease. Further studies in experimental models that reproduce the lipoprotein-dependent morphogenesis and release of virus particles, maturation, and intravascular remodeling of HCV-associated lipoproteins would help to develop novel lipid-targeting inhibitors to improve existing therapies.

Agata Budkowska, PhD, is scientific advisor for the department of international affairs at the Institut Pasteur, Paris. She has no conflicts of interest.

A hallmark of HCV infection is the association of virus particles with lipoproteins. The HCV virion (lipo-viro particle, LVP) is composed of nucleocapsid and envelope glycoproteins associated with very-low- and low-density lipoproteins, cholesterol, and apolipoproteins. The lipid components determine the size, density, hepatotropism, and infectivity of LVPs and play a role in cell entry, morphogenesis, release, and viral escape mechanisms. LVPs undergo dynamic changes during infection, and dietary triglycerides induce alterations in their biophysical properties and infectivity.

Dr. Andreo and colleagues used humanized Fah–/– mice to analyze the evolution of HCV particles during infection. As previously reported, two viral populations of different densities were detected in mice sera, with higher infectivity observed for the low-density population. The proportions and infectivity of these populations varied during infection, reflecting changes in biochemical features of the virus. Sucrose diet influenced the properties of virus particles; these properties’ changes correlated with a redistribution of triglycerides and cholesterol among lipoproteins.

Changes in biochemical features of the virus during infection represent a fascinating aspect of the structural heterogeneity, which influences HCV infectivity and evolution of the disease. Further studies in experimental models that reproduce the lipoprotein-dependent morphogenesis and release of virus particles, maturation, and intravascular remodeling of HCV-associated lipoproteins would help to develop novel lipid-targeting inhibitors to improve existing therapies.

Agata Budkowska, PhD, is scientific advisor for the department of international affairs at the Institut Pasteur, Paris. She has no conflicts of interest.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) particles are of lowest density and most infectious early in the course of infection, based on findings from a study of chimeric mice.

Over time, however, viral density became more heterogeneous and infectivity fell, reported Ursula Andreo, PhD, of Rockefeller University, New York, with her coinvestigators. A diet of 10% sucrose, which in rats induces hepatic secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), caused HCV particles to become slightly lower density and more infectious in the mice, the researchers reported. Although the shift was “minor,” it “correlated with a trend toward enhanced triglyceride and cholesterol levels in the same fractions,” they wrote. They recommended studying high-fat diets to determine whether altering the VLDL secretion pathway affects the biophysical properties of HCV. “A high-fat diet might have a more significant impact on the lipoprotein profile in this humanized mouse model,” they wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017 Jul;4[3]:405-17).

Because HCV tends to associate with lipoproteins, it shows a range of buoyant densities in the blood of infected patients. The “entry, replication, and assembly [of the virion] are linked closely to host lipid and lipoprotein metabolism,” wrote Dr. Andreo and her colleagues.

They created an in vivo model to study the buoyant density and infectivity of HCV particles, as well as their interaction with lipoproteins, by grafting human hepatocytes into the livers of immunodeficient mice that were homozygous recessive for fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase. Next, they infected 13 of these chimeric mice with J6-JFH1, an HCV strain that can establish long-term infections in mice that have human liver grafts (Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103[10]:3805-9). The human liver xenograft reconstituted the FAH gene, restoring triglycerides to normal levels in the chimeric mice and creating a suitable “humanlike” model of lipoprotein metabolism, the investigators wrote.

Density fractionation of infectious mouse serum revealed higher infectivity in the low-density fractions soon after infection, which also has been observed in a human liver chimeric mouse model of severe combined immunodeficiency disease, they added. In the HCV model, the human liver grafts were conserved 5 weeks after infection, and the mice had a lower proportion of lighter, infectious HCV particles.

The researchers lacked sufficient material to directly study the composition of virions or detect viral proteins in the various density fractions. However, they determined that apolipoprotein C1 was the lightest fraction and that apolipoprotein E was mainly found in the five lightest fractions. Both these apolipoproteins are “essential factors of HCV infectivity,” and neither redistributed over time, they said. They suggested using immunoelectron microscopy or mass spectrometry to study the nature and infectivity of viral particles further.

In humans, ingesting a high-fat milkshake increases detectable HCV RNA in the VLDL fraction, the researchers noted. In rodents, a sucrose diet also has been found to increase VLDL lipidation and secretion, so they gave five of the infected chimeric mice drinking water containing 10% sucrose. After 5 weeks, these mice had increased infectivity and higher levels of triglycerides and cholesterol, but the effect was small and disappeared after the sucrose was withdrawn.

HCV “circulates as a population of particles of light, as well as dense, buoyant densities, and both are infectious,” the researchers concluded. “Changes in diet, as well as conditions such as fasting and feeding, affect the distribution of HCV buoyant density gradients.”

Funders included the National Institutes of Health and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The investigators disclosed no conflicts.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) particles are of lowest density and most infectious early in the course of infection, based on findings from a study of chimeric mice.

Over time, however, viral density became more heterogeneous and infectivity fell, reported Ursula Andreo, PhD, of Rockefeller University, New York, with her coinvestigators. A diet of 10% sucrose, which in rats induces hepatic secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), caused HCV particles to become slightly lower density and more infectious in the mice, the researchers reported. Although the shift was “minor,” it “correlated with a trend toward enhanced triglyceride and cholesterol levels in the same fractions,” they wrote. They recommended studying high-fat diets to determine whether altering the VLDL secretion pathway affects the biophysical properties of HCV. “A high-fat diet might have a more significant impact on the lipoprotein profile in this humanized mouse model,” they wrote in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017 Jul;4[3]:405-17).

Because HCV tends to associate with lipoproteins, it shows a range of buoyant densities in the blood of infected patients. The “entry, replication, and assembly [of the virion] are linked closely to host lipid and lipoprotein metabolism,” wrote Dr. Andreo and her colleagues.

They created an in vivo model to study the buoyant density and infectivity of HCV particles, as well as their interaction with lipoproteins, by grafting human hepatocytes into the livers of immunodeficient mice that were homozygous recessive for fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase. Next, they infected 13 of these chimeric mice with J6-JFH1, an HCV strain that can establish long-term infections in mice that have human liver grafts (Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103[10]:3805-9). The human liver xenograft reconstituted the FAH gene, restoring triglycerides to normal levels in the chimeric mice and creating a suitable “humanlike” model of lipoprotein metabolism, the investigators wrote.

Density fractionation of infectious mouse serum revealed higher infectivity in the low-density fractions soon after infection, which also has been observed in a human liver chimeric mouse model of severe combined immunodeficiency disease, they added. In the HCV model, the human liver grafts were conserved 5 weeks after infection, and the mice had a lower proportion of lighter, infectious HCV particles.

The researchers lacked sufficient material to directly study the composition of virions or detect viral proteins in the various density fractions. However, they determined that apolipoprotein C1 was the lightest fraction and that apolipoprotein E was mainly found in the five lightest fractions. Both these apolipoproteins are “essential factors of HCV infectivity,” and neither redistributed over time, they said. They suggested using immunoelectron microscopy or mass spectrometry to study the nature and infectivity of viral particles further.

In humans, ingesting a high-fat milkshake increases detectable HCV RNA in the VLDL fraction, the researchers noted. In rodents, a sucrose diet also has been found to increase VLDL lipidation and secretion, so they gave five of the infected chimeric mice drinking water containing 10% sucrose. After 5 weeks, these mice had increased infectivity and higher levels of triglycerides and cholesterol, but the effect was small and disappeared after the sucrose was withdrawn.

HCV “circulates as a population of particles of light, as well as dense, buoyant densities, and both are infectious,” the researchers concluded. “Changes in diet, as well as conditions such as fasting and feeding, affect the distribution of HCV buoyant density gradients.”

Funders included the National Institutes of Health and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The investigators disclosed no conflicts.

FROM CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The biophysical properties of the hepatitis C virus evolve during the course of infection and shift with dietary changes.

Major finding: Density fractionation of infectious mouse serum showed higher infectivity in the low-density fractions soon after infection, but heterogeneity subsequently increased while infectivity decreased. A 5-week diet of 10% sucrose produced a minor shift toward infectivity that correlated with redistribution of triglycerides and cholesterol.

Data source: A study of 13 human liver chimeric mice.

Disclosures: Funders included the National Institutes of Health and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The investigators disclosed no conflicts.

Personality changes may not occur before Alzheimer’s onset

Personality changes do not presage dementia, at least when examined through the lens of self-report, a large retrospective study has determined.

Dementia patients do show personality characteristics that are different from those of their cognitively normal peers, wrote Antonio Terracciano, PhD (JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Sep 20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2816). Notably, they tend to be more neurotic and less conscientious, he noted. But among more than 2,000 older adults with up to 36 years of data, no temporal associations were found between these traits and the onset of cognitive difficulty, even within a few years of the onset of dementia symptoms.

“From a clinical perspective, these findings suggest that tracking change in self-rated personality as an early indicator of dementia is unlikely to be fruitful, while a single assessment provides reliable information on the personality traits that increase resilience [e.g., conscientiousness] or vulnerability [e.g., neuroticism] to clinical dementia,” wrote Dr. Terracciano of Florida State University, Tallahassee, and his coauthors.