User login

When should you consider combining 2 long-acting injectable antipsychotics?

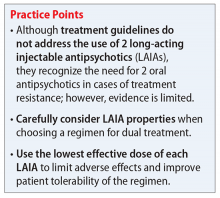

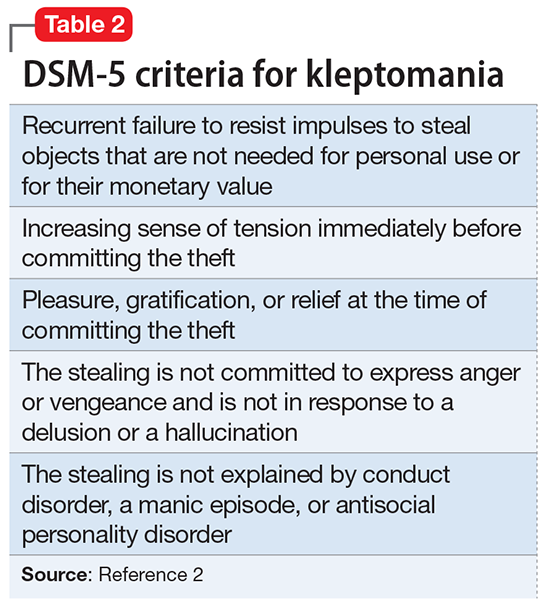

Ms. S, age 39, with a 15-year history of schizophrenia and severe paranoid delusions, is admitted after physically assaulting a staff member at a group home. She is receiving paliperidone palmitate, 234 mg every 4 weeks. This has reduced the severity of her symptoms, but she continues to have persistent delusions that affect her ability to accept redirection from staff. Ms. S frequently accuses staff and peers of sexual assault, says that she is pregnant, and does not adhere to treatment recommendations for laboratory monitoring because the “staff uses her blood for experiments.”

Ms. S frequently requires administration of oral and IM haloperidol, as needed, when she becomes aggressive with the staff. She has poor insight into her mental illness and does not believe that she needs medication. Ms. S has a long history of stopping her oral antipsychotic after a few days, reporting that it is “harming her baby.” Monotherapy has been tried with various long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIAs), but she still exhibits persistent delusions. The treatment team decides to add a second LAIA, haloperidol decanoate, 200 mg every 4 weeks, to her regimen.

Ladds et al.7 A 49-year-old woman with schizophrenia who was hospitalized for aggressive and bizarre behavior and had been institutionalized for 20 years stopped taking her medication regimen.7 She started taking 8-hour showers with bleach, talking incoherently, and believing that someone was poisoning her. She had poor response to oral risperidone monotherapy; however, 2 months after adding oral fluphenazine and benztropine to her regimen, her symptoms substantially improved (doses not reported). Because she had impaired insight into the need for daily medication, she was started on depot fluphenazine decanoate and risperidone microspheres (doses not reported) before discharge. No substantial adverse effects were noted with this regimen.

Wartelsteiner and Hofer.8 A man who had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia at age 20 presented with thought blocking, incoherence, persecutory delusions, and uncontrolled self-damaging behavior.8 He had been admitted 27 times over 7 years; during this time he received many antipsychotic monotherapies and combination regimens. A total of 8 oral antipsychotics (including clozapine) and 5 LAIAs had been administered during these trials. He significantly improved with the combination of olanzapine and risperidone. Both medications were switched to LAIA formulations to address medication nonadherence. His symptoms remained stable with risperidone microspheres, 100 mg, and olanzapine pamoate, 300 mg, each administered every 2 weeks. He did not experience any adverse effects with this combination therapy.

Scangos et al.9 A 26-year-old Vietnamese man with schizophrenia and an extensive history of unprovoked, psychotically driven assaults was given multiple antipsychotics (including clozapine) during hospitalizations, and his medication regimen consistently included 2 antipsychotics. After contracting viral gastroenteritis, he refused oral medications and required short-acting IM administration of both haloperidol, 5 mg, twice a day, and olanzapine, 10 mg, twice a day. Because of concerns about continuing this regimen, he was switched to haloperidol decanoate (dose not reported) and olanzapine pamoate, 405 mg, administered once per month. The injections were scheduled to alternate so that the patient would receive 1 injection every 2 weeks. The patient’s assaultive behavior was significantly reduced, and no adverse effects were reported.

Ross and Fabian.11 An African American man, age 44, was receiving haloperidol decanoate, 400 mg every 2 weeks, and oral haloperidol, 20 mg/d.11 Because of residual symptoms, a history of nonadherence, and concerns about increasing the haloperidol decanoate dose or frequency, oral haloperidol was discontinued and paliperidone palmitate, 156 mg every 4 weeks, was started. The patient was able to transition into a step-down unit, and no adverse effects were reported.

What to consider before initiating dual LAIA treatment

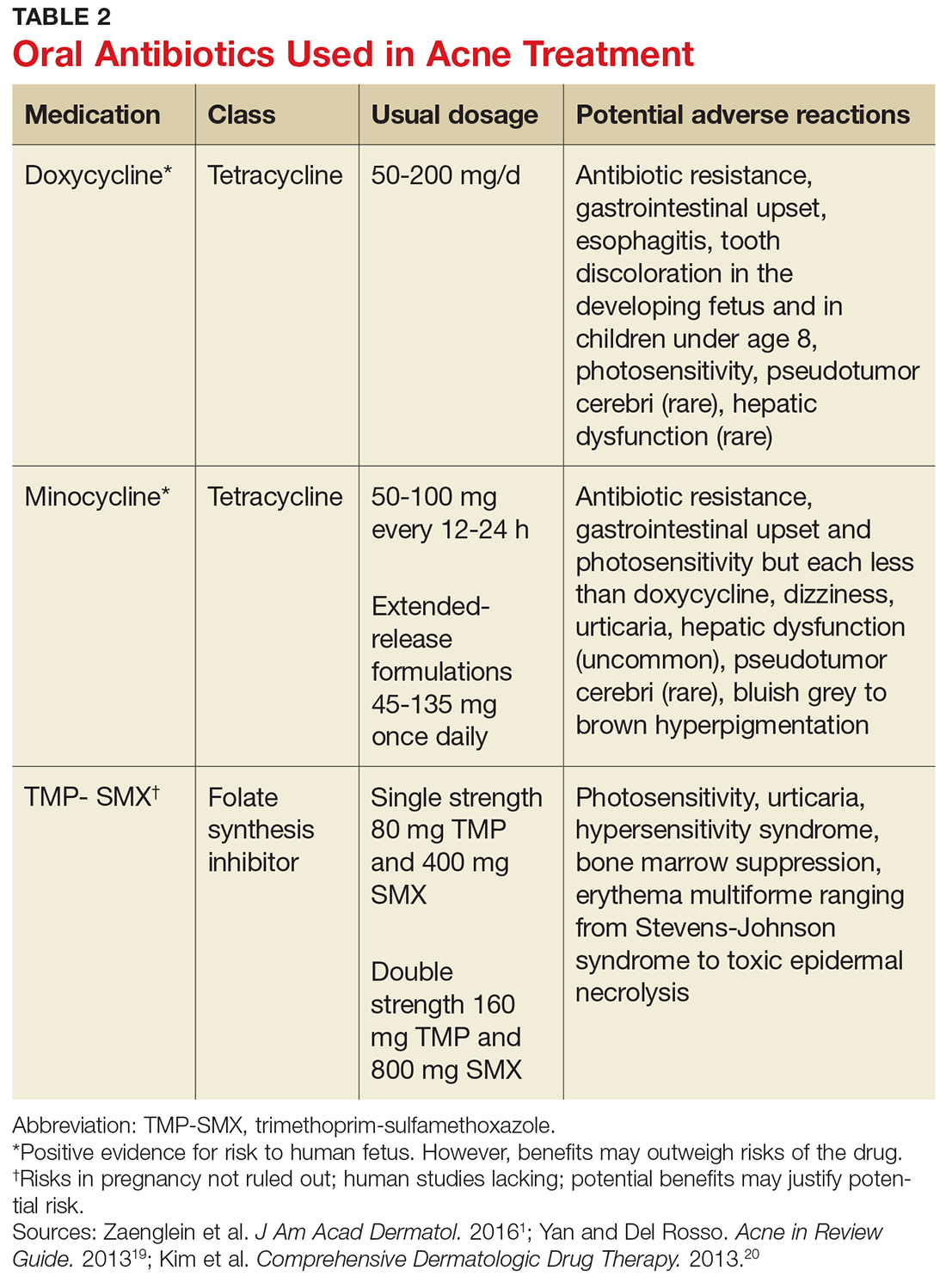

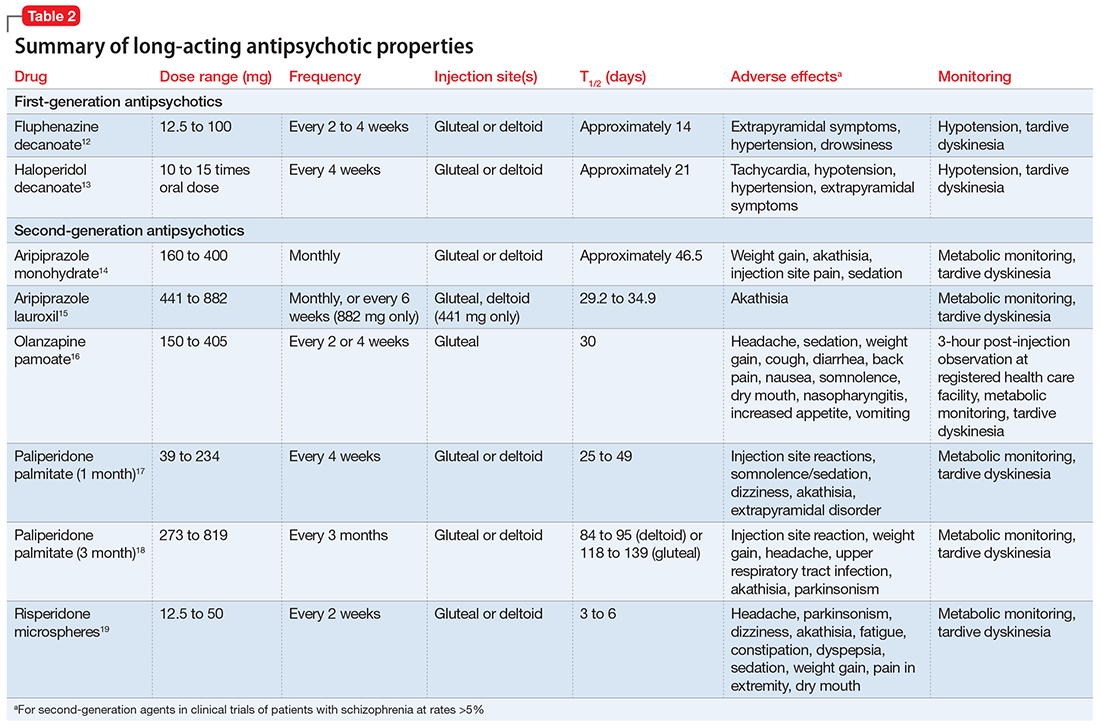

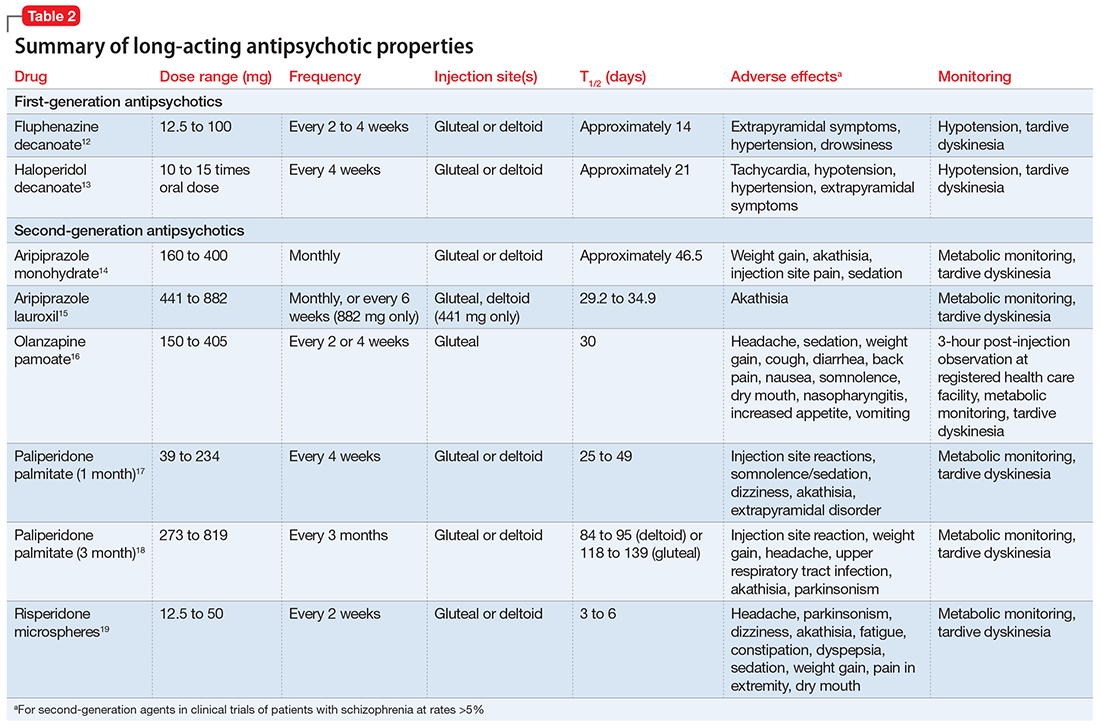

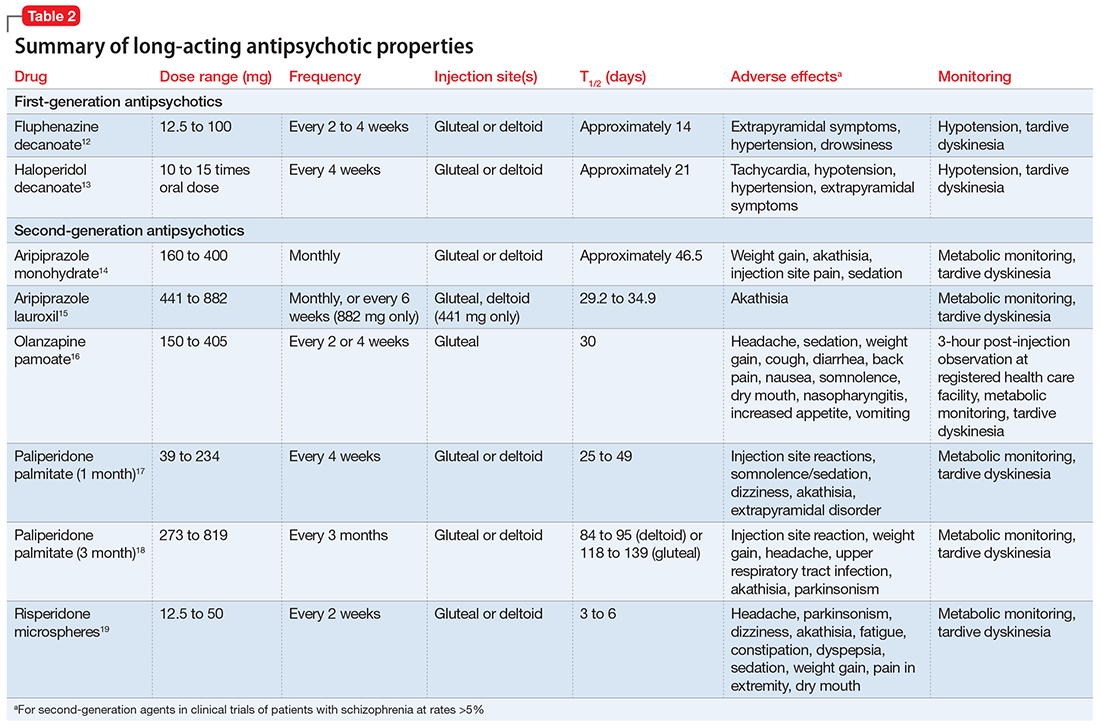

Evaluate the frequency of administration, flexibility of dosing, administration site, adverse effects, and monitoring requirements of each LAIA (Table 212-19) to ensure the patient’s optimal tolerability of the regimen. Previous tolerability of each medication must be confirmed by evaluating the patient’s medication history or oral or IM administration of each agent prior to initiating the LAIA.

When choosing 2 agents that are each administered once every 4 weeks, consider administering the medications together every 4 weeks or alternating administration so that the patient receives an injection every 2 weeks. Receiving an injection once every 2 weeks might be beneficial for patients who need close follow-up or are more sensitive to injection site reactions, whereas a regimen of once every 4 weeks might be beneficial for patients who are more resistant to receiving the injections, so there is potentially less time spent agitated or anxious leading up to the date of the injection.

Use the lowest effective dose of each LAIA to limit adverse effects and improve tolerability of the regimen. Monitor patients closely for adverse reactions and discontinue the regimen as soon as possible if a severe adverse reaction occurs.

Cost may influence the decision to use 2 LAIAs. The majority of LAIAs in the United States are available only as branded formulations. Insurance companies may require prior authorization for the use of 2 LAIAs.

Although there are no treatment guidelines for combining 2 LAIAs, this practice has been used. A few case reports have described successful use of dual LAIA treatment, but one should consider the risk of the publication’s bias. Overall, the decision to use 2 LAIAs is difficult because there is lack of a large evidence base supporting the practice or direction from treatment guidelines. Because of this, dual LAIA treatment should not be used for most patients. In cases of treatment-resistant schizophrenia where clozapine is not an option and adherence is a concern, it is reasonable to consider this strategy on a case-by-case basis.

1. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(9):789-796.

2. Lehman A, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

3. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al; the WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13(5):318-78.

4. Barnes TR; Schizophrenia Consensus Group of British Association for Psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(5):567-620. 5. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14(1):2-44.

6. Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, et al; Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):94-103.

7. Ladds B, Cosme R, Rivera F. Concurrent use of two depot antipsychotic medications in schizophrenia. The Internet Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;1(1):1-3.

8. Wartelsteiner F, Hofer A. Treating schizophrenia with 2 long-acting injectable antipsychotic drugs: a case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(4):474-475.

9. Scangos KW, Caton M, Newman WJ. Multiple long-acting injectable antipsychotics for treatment-resistant schizophrenia: case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(3):283-285.

10. Yazdi K, Rosenleitner J, Pischinger B. Combination of two depot antipsychotic drugs [in German]. Nervenarzt. 2014;85(7):870-871.

11. Ross C, Fabian T. High dose haloperidol decanoate augmentation with paliperidone palmitate. Presented at: College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists 16th Annual Meeting; April 21-24, 2013; Colorado Springs, CO.

12. Fluphenazine decanoate [package insert]. Schaumburg, IL: APP Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2010.

13. Haloperidol decanoate [package insert]. Rockford, IL: Mylan; 2014.

14. Abilify Maintena [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; 2016.

15. Aristada [package insert]. Waltham, MA: Alkermes; 2016.

16. Zyprexa Relprevv [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Lilly USA, LLC; 2016.

17. Invega Sustenna [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2009.

18. Invega Trinza [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2015.

19. Risperdal Consta [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2007.

Ms. S, age 39, with a 15-year history of schizophrenia and severe paranoid delusions, is admitted after physically assaulting a staff member at a group home. She is receiving paliperidone palmitate, 234 mg every 4 weeks. This has reduced the severity of her symptoms, but she continues to have persistent delusions that affect her ability to accept redirection from staff. Ms. S frequently accuses staff and peers of sexual assault, says that she is pregnant, and does not adhere to treatment recommendations for laboratory monitoring because the “staff uses her blood for experiments.”

Ms. S frequently requires administration of oral and IM haloperidol, as needed, when she becomes aggressive with the staff. She has poor insight into her mental illness and does not believe that she needs medication. Ms. S has a long history of stopping her oral antipsychotic after a few days, reporting that it is “harming her baby.” Monotherapy has been tried with various long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIAs), but she still exhibits persistent delusions. The treatment team decides to add a second LAIA, haloperidol decanoate, 200 mg every 4 weeks, to her regimen.

Ladds et al.7 A 49-year-old woman with schizophrenia who was hospitalized for aggressive and bizarre behavior and had been institutionalized for 20 years stopped taking her medication regimen.7 She started taking 8-hour showers with bleach, talking incoherently, and believing that someone was poisoning her. She had poor response to oral risperidone monotherapy; however, 2 months after adding oral fluphenazine and benztropine to her regimen, her symptoms substantially improved (doses not reported). Because she had impaired insight into the need for daily medication, she was started on depot fluphenazine decanoate and risperidone microspheres (doses not reported) before discharge. No substantial adverse effects were noted with this regimen.

Wartelsteiner and Hofer.8 A man who had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia at age 20 presented with thought blocking, incoherence, persecutory delusions, and uncontrolled self-damaging behavior.8 He had been admitted 27 times over 7 years; during this time he received many antipsychotic monotherapies and combination regimens. A total of 8 oral antipsychotics (including clozapine) and 5 LAIAs had been administered during these trials. He significantly improved with the combination of olanzapine and risperidone. Both medications were switched to LAIA formulations to address medication nonadherence. His symptoms remained stable with risperidone microspheres, 100 mg, and olanzapine pamoate, 300 mg, each administered every 2 weeks. He did not experience any adverse effects with this combination therapy.

Scangos et al.9 A 26-year-old Vietnamese man with schizophrenia and an extensive history of unprovoked, psychotically driven assaults was given multiple antipsychotics (including clozapine) during hospitalizations, and his medication regimen consistently included 2 antipsychotics. After contracting viral gastroenteritis, he refused oral medications and required short-acting IM administration of both haloperidol, 5 mg, twice a day, and olanzapine, 10 mg, twice a day. Because of concerns about continuing this regimen, he was switched to haloperidol decanoate (dose not reported) and olanzapine pamoate, 405 mg, administered once per month. The injections were scheduled to alternate so that the patient would receive 1 injection every 2 weeks. The patient’s assaultive behavior was significantly reduced, and no adverse effects were reported.

Ross and Fabian.11 An African American man, age 44, was receiving haloperidol decanoate, 400 mg every 2 weeks, and oral haloperidol, 20 mg/d.11 Because of residual symptoms, a history of nonadherence, and concerns about increasing the haloperidol decanoate dose or frequency, oral haloperidol was discontinued and paliperidone palmitate, 156 mg every 4 weeks, was started. The patient was able to transition into a step-down unit, and no adverse effects were reported.

What to consider before initiating dual LAIA treatment

Evaluate the frequency of administration, flexibility of dosing, administration site, adverse effects, and monitoring requirements of each LAIA (Table 212-19) to ensure the patient’s optimal tolerability of the regimen. Previous tolerability of each medication must be confirmed by evaluating the patient’s medication history or oral or IM administration of each agent prior to initiating the LAIA.

When choosing 2 agents that are each administered once every 4 weeks, consider administering the medications together every 4 weeks or alternating administration so that the patient receives an injection every 2 weeks. Receiving an injection once every 2 weeks might be beneficial for patients who need close follow-up or are more sensitive to injection site reactions, whereas a regimen of once every 4 weeks might be beneficial for patients who are more resistant to receiving the injections, so there is potentially less time spent agitated or anxious leading up to the date of the injection.

Use the lowest effective dose of each LAIA to limit adverse effects and improve tolerability of the regimen. Monitor patients closely for adverse reactions and discontinue the regimen as soon as possible if a severe adverse reaction occurs.

Cost may influence the decision to use 2 LAIAs. The majority of LAIAs in the United States are available only as branded formulations. Insurance companies may require prior authorization for the use of 2 LAIAs.

Although there are no treatment guidelines for combining 2 LAIAs, this practice has been used. A few case reports have described successful use of dual LAIA treatment, but one should consider the risk of the publication’s bias. Overall, the decision to use 2 LAIAs is difficult because there is lack of a large evidence base supporting the practice or direction from treatment guidelines. Because of this, dual LAIA treatment should not be used for most patients. In cases of treatment-resistant schizophrenia where clozapine is not an option and adherence is a concern, it is reasonable to consider this strategy on a case-by-case basis.

Ms. S, age 39, with a 15-year history of schizophrenia and severe paranoid delusions, is admitted after physically assaulting a staff member at a group home. She is receiving paliperidone palmitate, 234 mg every 4 weeks. This has reduced the severity of her symptoms, but she continues to have persistent delusions that affect her ability to accept redirection from staff. Ms. S frequently accuses staff and peers of sexual assault, says that she is pregnant, and does not adhere to treatment recommendations for laboratory monitoring because the “staff uses her blood for experiments.”

Ms. S frequently requires administration of oral and IM haloperidol, as needed, when she becomes aggressive with the staff. She has poor insight into her mental illness and does not believe that she needs medication. Ms. S has a long history of stopping her oral antipsychotic after a few days, reporting that it is “harming her baby.” Monotherapy has been tried with various long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIAs), but she still exhibits persistent delusions. The treatment team decides to add a second LAIA, haloperidol decanoate, 200 mg every 4 weeks, to her regimen.

Ladds et al.7 A 49-year-old woman with schizophrenia who was hospitalized for aggressive and bizarre behavior and had been institutionalized for 20 years stopped taking her medication regimen.7 She started taking 8-hour showers with bleach, talking incoherently, and believing that someone was poisoning her. She had poor response to oral risperidone monotherapy; however, 2 months after adding oral fluphenazine and benztropine to her regimen, her symptoms substantially improved (doses not reported). Because she had impaired insight into the need for daily medication, she was started on depot fluphenazine decanoate and risperidone microspheres (doses not reported) before discharge. No substantial adverse effects were noted with this regimen.

Wartelsteiner and Hofer.8 A man who had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia at age 20 presented with thought blocking, incoherence, persecutory delusions, and uncontrolled self-damaging behavior.8 He had been admitted 27 times over 7 years; during this time he received many antipsychotic monotherapies and combination regimens. A total of 8 oral antipsychotics (including clozapine) and 5 LAIAs had been administered during these trials. He significantly improved with the combination of olanzapine and risperidone. Both medications were switched to LAIA formulations to address medication nonadherence. His symptoms remained stable with risperidone microspheres, 100 mg, and olanzapine pamoate, 300 mg, each administered every 2 weeks. He did not experience any adverse effects with this combination therapy.

Scangos et al.9 A 26-year-old Vietnamese man with schizophrenia and an extensive history of unprovoked, psychotically driven assaults was given multiple antipsychotics (including clozapine) during hospitalizations, and his medication regimen consistently included 2 antipsychotics. After contracting viral gastroenteritis, he refused oral medications and required short-acting IM administration of both haloperidol, 5 mg, twice a day, and olanzapine, 10 mg, twice a day. Because of concerns about continuing this regimen, he was switched to haloperidol decanoate (dose not reported) and olanzapine pamoate, 405 mg, administered once per month. The injections were scheduled to alternate so that the patient would receive 1 injection every 2 weeks. The patient’s assaultive behavior was significantly reduced, and no adverse effects were reported.

Ross and Fabian.11 An African American man, age 44, was receiving haloperidol decanoate, 400 mg every 2 weeks, and oral haloperidol, 20 mg/d.11 Because of residual symptoms, a history of nonadherence, and concerns about increasing the haloperidol decanoate dose or frequency, oral haloperidol was discontinued and paliperidone palmitate, 156 mg every 4 weeks, was started. The patient was able to transition into a step-down unit, and no adverse effects were reported.

What to consider before initiating dual LAIA treatment

Evaluate the frequency of administration, flexibility of dosing, administration site, adverse effects, and monitoring requirements of each LAIA (Table 212-19) to ensure the patient’s optimal tolerability of the regimen. Previous tolerability of each medication must be confirmed by evaluating the patient’s medication history or oral or IM administration of each agent prior to initiating the LAIA.

When choosing 2 agents that are each administered once every 4 weeks, consider administering the medications together every 4 weeks or alternating administration so that the patient receives an injection every 2 weeks. Receiving an injection once every 2 weeks might be beneficial for patients who need close follow-up or are more sensitive to injection site reactions, whereas a regimen of once every 4 weeks might be beneficial for patients who are more resistant to receiving the injections, so there is potentially less time spent agitated or anxious leading up to the date of the injection.

Use the lowest effective dose of each LAIA to limit adverse effects and improve tolerability of the regimen. Monitor patients closely for adverse reactions and discontinue the regimen as soon as possible if a severe adverse reaction occurs.

Cost may influence the decision to use 2 LAIAs. The majority of LAIAs in the United States are available only as branded formulations. Insurance companies may require prior authorization for the use of 2 LAIAs.

Although there are no treatment guidelines for combining 2 LAIAs, this practice has been used. A few case reports have described successful use of dual LAIA treatment, but one should consider the risk of the publication’s bias. Overall, the decision to use 2 LAIAs is difficult because there is lack of a large evidence base supporting the practice or direction from treatment guidelines. Because of this, dual LAIA treatment should not be used for most patients. In cases of treatment-resistant schizophrenia where clozapine is not an option and adherence is a concern, it is reasonable to consider this strategy on a case-by-case basis.

1. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(9):789-796.

2. Lehman A, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

3. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al; the WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13(5):318-78.

4. Barnes TR; Schizophrenia Consensus Group of British Association for Psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(5):567-620. 5. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14(1):2-44.

6. Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, et al; Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):94-103.

7. Ladds B, Cosme R, Rivera F. Concurrent use of two depot antipsychotic medications in schizophrenia. The Internet Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;1(1):1-3.

8. Wartelsteiner F, Hofer A. Treating schizophrenia with 2 long-acting injectable antipsychotic drugs: a case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(4):474-475.

9. Scangos KW, Caton M, Newman WJ. Multiple long-acting injectable antipsychotics for treatment-resistant schizophrenia: case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(3):283-285.

10. Yazdi K, Rosenleitner J, Pischinger B. Combination of two depot antipsychotic drugs [in German]. Nervenarzt. 2014;85(7):870-871.

11. Ross C, Fabian T. High dose haloperidol decanoate augmentation with paliperidone palmitate. Presented at: College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists 16th Annual Meeting; April 21-24, 2013; Colorado Springs, CO.

12. Fluphenazine decanoate [package insert]. Schaumburg, IL: APP Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2010.

13. Haloperidol decanoate [package insert]. Rockford, IL: Mylan; 2014.

14. Abilify Maintena [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; 2016.

15. Aristada [package insert]. Waltham, MA: Alkermes; 2016.

16. Zyprexa Relprevv [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Lilly USA, LLC; 2016.

17. Invega Sustenna [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2009.

18. Invega Trinza [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2015.

19. Risperdal Consta [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2007.

1. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic. A double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(9):789-796.

2. Lehman A, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

3. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al; the WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 1: update 2012 on the acute treatment of schizophrenia and management of treatment resistance. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13(5):318-78.

4. Barnes TR; Schizophrenia Consensus Group of British Association for Psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(5):567-620. 5. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al; WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Schizophrenia. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14(1):2-44.

6. Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, et al; Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2009. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):94-103.

7. Ladds B, Cosme R, Rivera F. Concurrent use of two depot antipsychotic medications in schizophrenia. The Internet Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;1(1):1-3.

8. Wartelsteiner F, Hofer A. Treating schizophrenia with 2 long-acting injectable antipsychotic drugs: a case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(4):474-475.

9. Scangos KW, Caton M, Newman WJ. Multiple long-acting injectable antipsychotics for treatment-resistant schizophrenia: case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(3):283-285.

10. Yazdi K, Rosenleitner J, Pischinger B. Combination of two depot antipsychotic drugs [in German]. Nervenarzt. 2014;85(7):870-871.

11. Ross C, Fabian T. High dose haloperidol decanoate augmentation with paliperidone palmitate. Presented at: College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists 16th Annual Meeting; April 21-24, 2013; Colorado Springs, CO.

12. Fluphenazine decanoate [package insert]. Schaumburg, IL: APP Pharmaceuticals, LLC; 2010.

13. Haloperidol decanoate [package insert]. Rockford, IL: Mylan; 2014.

14. Abilify Maintena [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; 2016.

15. Aristada [package insert]. Waltham, MA: Alkermes; 2016.

16. Zyprexa Relprevv [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Lilly USA, LLC; 2016.

17. Invega Sustenna [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2009.

18. Invega Trinza [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2015.

19. Risperdal Consta [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2007.

The girl who couldn’t stop stealing

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

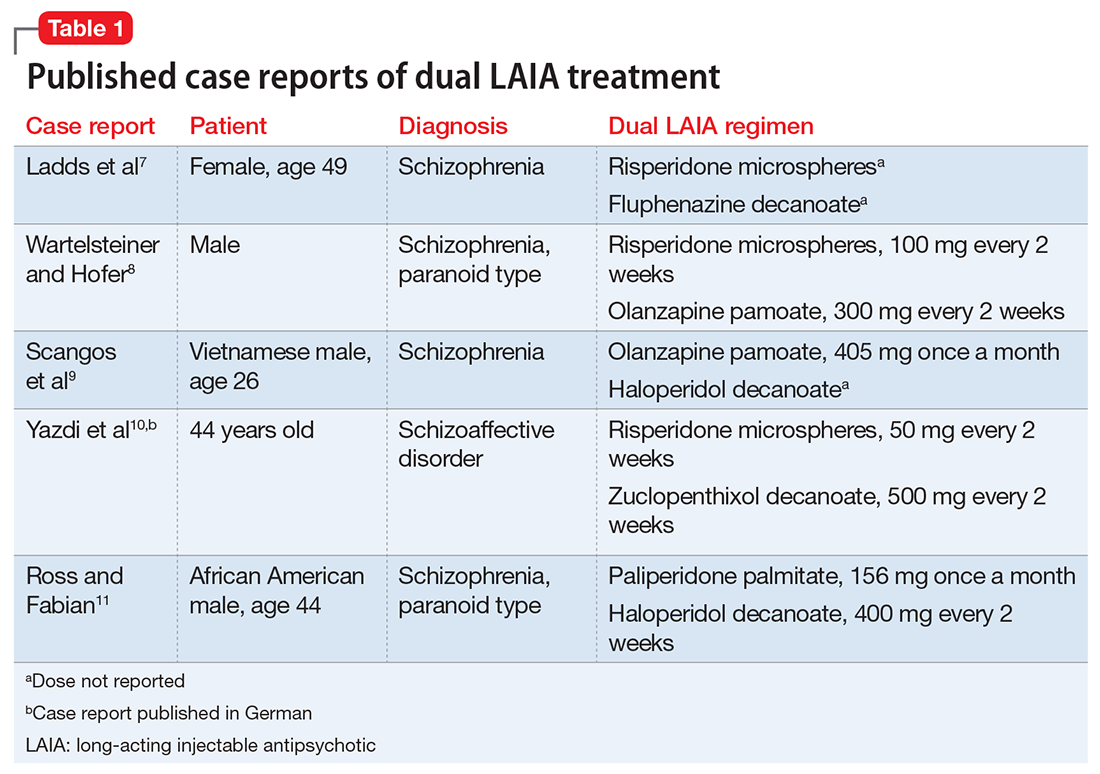

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

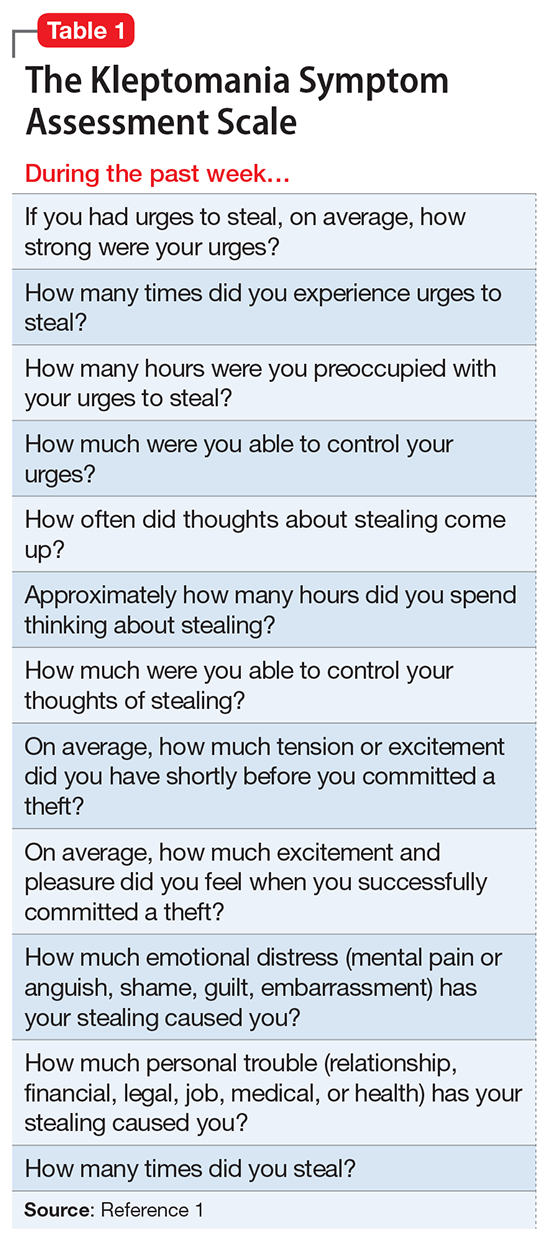

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.

Physician impairment

Most physicians are likely familiar with guidelines relating to physician impairment, but they may not be aware that these guidelines typically conflict with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which protects all employees against unwarranted requests for mental health information or evaluations.

Under the ADA, employers cannot request mental health information from their employees or refer them for mental health evaluations without objective evidence showing that either the employee:

- is unable to perform essential job functions because of a mental health condition

- poses a high risk of substantial, imminent harm to himself (herself) or others in the workplace because of a mental health condition.1

Employers cannot rely on speculative evidence or generalizations about these conditions when making these determinations,1 and common mental disorders (eg, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, specific learning disorders, etc.) should almost never form the basis of such requests.2

In contrast, the American Medical Association (AMA) does not distinguish between the presence of a mental health condition and physician impairment,3,4 which may result in unwarranted requests and referrals for mental health evaluations. Some state laws on impairment, which all derive from AMA policies,5 even state outright that, “‘Impaired’ or ‘impairment’ means the presence of the diseases of alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental illness”6 and directly discriminate against physicians with these conditions.

State physician health programs (PHPs) also may describe impairment in problematic ways (eg, “Involvement in litigation against hospital”).7 Their descriptions also are overly inclusive in that they could be used to describe most physicians (N.D.L., J.W.B., unpublished data, 2017), and they rarely represent sufficient legal indications for a mental health evaluation under the ADA (N.D.L., J.W.B., unpublished data, 2017). Even the APA’s Clinical Guide to Psychiatric Ethics describes physician impairment as synonymous with mental illness.8

Requests for mental health information or evaluations not only can include referrals to state PHPs but also “suggestions” to see a psychologist, professional job coach, or any provider who may ask for mental health information. Under the ADA's guidelines, obtaining “voluntary” consent from an employee who could be fired for not cooperating does not change the involuntary nature of these requests.2,9

Employers who hire psychiatrists, physicians, and medical residents should comply with the ADA and disregard the AMA’s policies, state laws, PHPs, other institutional guidelines,10 and guidance from some articles published in

1. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. EEOC enforcement guidance on the Americans with Disabilities Act and psychiatric disabilities. No. 915.002. http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/psych.html. Updated March 9, 2009. Accessed July 20, 2017.

2. Lawson ND, Kalet AL. The administrative psychiatric evaluation. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(1):14-17.

3. American Medical Association. Physician impairment H-95.955: Drug Abuse. https://policy search.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/physician%20impairment?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-5334.xml. Updated 2009. Accessed April 20, 2017.

4. Myers MF, Gabbard GO. The physician as patient: a clinical handbook for mental health professionals. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2008.

5. Sargent DA. The impaired physician movement: an interim report. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1985;36(3):294-297.

6. Arkansas State Medical Board. Arkansas medical practices act and regulations. http://www.armedicalboard.org/professionals/pdf/mpa.pdf. Revised March 2017. Accessed July 11, 2017.

7. Oklahoma Health Professionals Program. Chemical dependency. https://www.okhpp.org/chemical-dependency. Accessed September 15, 2017.

8. Trockel M, Miller MN, Roberts LW. Clinician well-being and impairment. In: Roberts LW, ed. A clinical guide to psychiatric ethics. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2016:223-236.

9. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Regulations under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Federal Register. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-05-17/pdf/2016-11558.pdf. Published May 17, 2016. Accessed August 2

10. Lawson ND. Comply with federal laws before checking institutional guidelines on resident referrals for psychiatric evaluations. J Grad Med Educ. In press.

11. Bright RP, Krahn L. Impaired physicians: how to recognize, when to report, and where to refer. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):11-20.

12. Mossman D, Farrell HM. Physician impairment: when should you report? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(9):67-71.

Most physicians are likely familiar with guidelines relating to physician impairment, but they may not be aware that these guidelines typically conflict with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which protects all employees against unwarranted requests for mental health information or evaluations.

Under the ADA, employers cannot request mental health information from their employees or refer them for mental health evaluations without objective evidence showing that either the employee:

- is unable to perform essential job functions because of a mental health condition

- poses a high risk of substantial, imminent harm to himself (herself) or others in the workplace because of a mental health condition.1

Employers cannot rely on speculative evidence or generalizations about these conditions when making these determinations,1 and common mental disorders (eg, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, specific learning disorders, etc.) should almost never form the basis of such requests.2

In contrast, the American Medical Association (AMA) does not distinguish between the presence of a mental health condition and physician impairment,3,4 which may result in unwarranted requests and referrals for mental health evaluations. Some state laws on impairment, which all derive from AMA policies,5 even state outright that, “‘Impaired’ or ‘impairment’ means the presence of the diseases of alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental illness”6 and directly discriminate against physicians with these conditions.

State physician health programs (PHPs) also may describe impairment in problematic ways (eg, “Involvement in litigation against hospital”).7 Their descriptions also are overly inclusive in that they could be used to describe most physicians (N.D.L., J.W.B., unpublished data, 2017), and they rarely represent sufficient legal indications for a mental health evaluation under the ADA (N.D.L., J.W.B., unpublished data, 2017). Even the APA’s Clinical Guide to Psychiatric Ethics describes physician impairment as synonymous with mental illness.8

Requests for mental health information or evaluations not only can include referrals to state PHPs but also “suggestions” to see a psychologist, professional job coach, or any provider who may ask for mental health information. Under the ADA's guidelines, obtaining “voluntary” consent from an employee who could be fired for not cooperating does not change the involuntary nature of these requests.2,9

Employers who hire psychiatrists, physicians, and medical residents should comply with the ADA and disregard the AMA’s policies, state laws, PHPs, other institutional guidelines,10 and guidance from some articles published in

Most physicians are likely familiar with guidelines relating to physician impairment, but they may not be aware that these guidelines typically conflict with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which protects all employees against unwarranted requests for mental health information or evaluations.

Under the ADA, employers cannot request mental health information from their employees or refer them for mental health evaluations without objective evidence showing that either the employee:

- is unable to perform essential job functions because of a mental health condition

- poses a high risk of substantial, imminent harm to himself (herself) or others in the workplace because of a mental health condition.1

Employers cannot rely on speculative evidence or generalizations about these conditions when making these determinations,1 and common mental disorders (eg, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, specific learning disorders, etc.) should almost never form the basis of such requests.2

In contrast, the American Medical Association (AMA) does not distinguish between the presence of a mental health condition and physician impairment,3,4 which may result in unwarranted requests and referrals for mental health evaluations. Some state laws on impairment, which all derive from AMA policies,5 even state outright that, “‘Impaired’ or ‘impairment’ means the presence of the diseases of alcoholism, drug abuse, or mental illness”6 and directly discriminate against physicians with these conditions.

State physician health programs (PHPs) also may describe impairment in problematic ways (eg, “Involvement in litigation against hospital”).7 Their descriptions also are overly inclusive in that they could be used to describe most physicians (N.D.L., J.W.B., unpublished data, 2017), and they rarely represent sufficient legal indications for a mental health evaluation under the ADA (N.D.L., J.W.B., unpublished data, 2017). Even the APA’s Clinical Guide to Psychiatric Ethics describes physician impairment as synonymous with mental illness.8

Requests for mental health information or evaluations not only can include referrals to state PHPs but also “suggestions” to see a psychologist, professional job coach, or any provider who may ask for mental health information. Under the ADA's guidelines, obtaining “voluntary” consent from an employee who could be fired for not cooperating does not change the involuntary nature of these requests.2,9

Employers who hire psychiatrists, physicians, and medical residents should comply with the ADA and disregard the AMA’s policies, state laws, PHPs, other institutional guidelines,10 and guidance from some articles published in

1. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. EEOC enforcement guidance on the Americans with Disabilities Act and psychiatric disabilities. No. 915.002. http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/psych.html. Updated March 9, 2009. Accessed July 20, 2017.

2. Lawson ND, Kalet AL. The administrative psychiatric evaluation. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(1):14-17.

3. American Medical Association. Physician impairment H-95.955: Drug Abuse. https://policy search.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/physician%20impairment?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-5334.xml. Updated 2009. Accessed April 20, 2017.

4. Myers MF, Gabbard GO. The physician as patient: a clinical handbook for mental health professionals. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2008.

5. Sargent DA. The impaired physician movement: an interim report. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1985;36(3):294-297.

6. Arkansas State Medical Board. Arkansas medical practices act and regulations. http://www.armedicalboard.org/professionals/pdf/mpa.pdf. Revised March 2017. Accessed July 11, 2017.

7. Oklahoma Health Professionals Program. Chemical dependency. https://www.okhpp.org/chemical-dependency. Accessed September 15, 2017.

8. Trockel M, Miller MN, Roberts LW. Clinician well-being and impairment. In: Roberts LW, ed. A clinical guide to psychiatric ethics. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2016:223-236.

9. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Regulations under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Federal Register. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-05-17/pdf/2016-11558.pdf. Published May 17, 2016. Accessed August 2

10. Lawson ND. Comply with federal laws before checking institutional guidelines on resident referrals for psychiatric evaluations. J Grad Med Educ. In press.

11. Bright RP, Krahn L. Impaired physicians: how to recognize, when to report, and where to refer. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):11-20.

12. Mossman D, Farrell HM. Physician impairment: when should you report? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(9):67-71.

1. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. EEOC enforcement guidance on the Americans with Disabilities Act and psychiatric disabilities. No. 915.002. http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/psych.html. Updated March 9, 2009. Accessed July 20, 2017.

2. Lawson ND, Kalet AL. The administrative psychiatric evaluation. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(1):14-17.

3. American Medical Association. Physician impairment H-95.955: Drug Abuse. https://policy search.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/physician%20impairment?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-5334.xml. Updated 2009. Accessed April 20, 2017.

4. Myers MF, Gabbard GO. The physician as patient: a clinical handbook for mental health professionals. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2008.

5. Sargent DA. The impaired physician movement: an interim report. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1985;36(3):294-297.

6. Arkansas State Medical Board. Arkansas medical practices act and regulations. http://www.armedicalboard.org/professionals/pdf/mpa.pdf. Revised March 2017. Accessed July 11, 2017.

7. Oklahoma Health Professionals Program. Chemical dependency. https://www.okhpp.org/chemical-dependency. Accessed September 15, 2017.

8. Trockel M, Miller MN, Roberts LW. Clinician well-being and impairment. In: Roberts LW, ed. A clinical guide to psychiatric ethics. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2016:223-236.

9. U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Regulations under the Americans with Disabilities Act. Federal Register. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-05-17/pdf/2016-11558.pdf. Published May 17, 2016. Accessed August 2

10. Lawson ND. Comply with federal laws before checking institutional guidelines on resident referrals for psychiatric evaluations. J Grad Med Educ. In press.

11. Bright RP, Krahn L. Impaired physicians: how to recognize, when to report, and where to refer. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(6):11-20.

12. Mossman D, Farrell HM. Physician impairment: when should you report? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(9):67-71.

Self-disclosure as therapy: The benefits of expressive writing

As psychiatrists, we often provide our patients with a prescription in the hope that the medication will alleviate their symptoms. Perhaps we engage our patients in psychotherapy, encouraging them to reflect on their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions to alter their cognitions. We may remark that our goal is for the patient to “become their own therapist.” What if we encouraged our patients to express themselves in a less structured manner and become their own therapists through writing?

Benefits of expressive writing

Writing about an experienced traumatic event—specifically, to express emotions related to the event—has been associated with improved health outcomes.1,2 Many of these improvements are related to somatic health and basic function, including decreased use of health services, improved immune functioning, and a boost in grades or occupational performance.1 Patients who participate in expressive writing also have demonstrated improvements in distress, negative affect, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.1,2 Although improvement in PTSD symptoms with expressive writing has varied across studies, it appears that patients with PTSD who score high in trait negative emotion may receive the most benefit from the practice.3

Why does it work?

There are several theories regarding why expressive writing is an effective therapy. Originally, it was believed that the active inhibition of not talking about traumatic events was a form of physiological work and a long-term, low-lying stressor, and that writing about such events could reduce this stress. However, newer studies offer various explanations for its efficacy, including:

- repeat exposure to stressful or traumatic memories and consequent self-distancing

- creation of a narrative around the stressful event

- labeling of emotions

- self-affirmation and meaning-making related to the negative event.4

Rx writing

Encouraging your patients to use expressive writing is simple. You might ask a patient struggling with distress and negative affect following a traumatic experience to write about his (her) thoughts and feelings regarding the incident. For example:

Spend about 15 minutes writing your deepest thoughts and feelings about going through this traumatic experience. Discuss the ways it affected different areas of your life, including relationships with family and friends, school or work, or self-confidence and self-esteem. Don’t worry about spelling, grammar, or sentence structure.

Assure patients that you do not need to review their writing, but would like to hear about their experience writing. Many studies on expressive writing instructed participants to write for 3 to 5 consecutive days, 15 to 30 minutes each day.1,2 Patients may disclose a dramatic spectrum and intensity of experience and often are willing to do so.

Expressive writing is a simple, low-risk exercise that benefits many people. Perhaps by prescribing a course of writing, you will find your patients can benefit as well.

1. Baikie KA, Geerligs L, Wilhelm K. Expressive writing and positive writing for participants with mood disorders: an online randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):310-319.

2. Krpan KM, Kross E, Berman MG, et al. An everyday activity as a treatment for depression: the benefits of expressive writing for people diagnosed with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):1148-1151.

3. Hoyt T, Yeater EA. The effects of negative emotion and expressive writing on posttraumatic stress symptoms. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;30:549-569.

4. Niles AN, Byrne Haltom KE, Lieberman MD, et al. Writing content predicts benefit from written expressive disclosure: evidence for repeated exposure and self-affirmation. Cogn Emot. 2016;30(2):258-274.

As psychiatrists, we often provide our patients with a prescription in the hope that the medication will alleviate their symptoms. Perhaps we engage our patients in psychotherapy, encouraging them to reflect on their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions to alter their cognitions. We may remark that our goal is for the patient to “become their own therapist.” What if we encouraged our patients to express themselves in a less structured manner and become their own therapists through writing?

Benefits of expressive writing

Writing about an experienced traumatic event—specifically, to express emotions related to the event—has been associated with improved health outcomes.1,2 Many of these improvements are related to somatic health and basic function, including decreased use of health services, improved immune functioning, and a boost in grades or occupational performance.1 Patients who participate in expressive writing also have demonstrated improvements in distress, negative affect, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.1,2 Although improvement in PTSD symptoms with expressive writing has varied across studies, it appears that patients with PTSD who score high in trait negative emotion may receive the most benefit from the practice.3

Why does it work?

There are several theories regarding why expressive writing is an effective therapy. Originally, it was believed that the active inhibition of not talking about traumatic events was a form of physiological work and a long-term, low-lying stressor, and that writing about such events could reduce this stress. However, newer studies offer various explanations for its efficacy, including:

- repeat exposure to stressful or traumatic memories and consequent self-distancing

- creation of a narrative around the stressful event

- labeling of emotions

- self-affirmation and meaning-making related to the negative event.4

Rx writing

Encouraging your patients to use expressive writing is simple. You might ask a patient struggling with distress and negative affect following a traumatic experience to write about his (her) thoughts and feelings regarding the incident. For example:

Spend about 15 minutes writing your deepest thoughts and feelings about going through this traumatic experience. Discuss the ways it affected different areas of your life, including relationships with family and friends, school or work, or self-confidence and self-esteem. Don’t worry about spelling, grammar, or sentence structure.

Assure patients that you do not need to review their writing, but would like to hear about their experience writing. Many studies on expressive writing instructed participants to write for 3 to 5 consecutive days, 15 to 30 minutes each day.1,2 Patients may disclose a dramatic spectrum and intensity of experience and often are willing to do so.

Expressive writing is a simple, low-risk exercise that benefits many people. Perhaps by prescribing a course of writing, you will find your patients can benefit as well.

As psychiatrists, we often provide our patients with a prescription in the hope that the medication will alleviate their symptoms. Perhaps we engage our patients in psychotherapy, encouraging them to reflect on their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions to alter their cognitions. We may remark that our goal is for the patient to “become their own therapist.” What if we encouraged our patients to express themselves in a less structured manner and become their own therapists through writing?

Benefits of expressive writing

Writing about an experienced traumatic event—specifically, to express emotions related to the event—has been associated with improved health outcomes.1,2 Many of these improvements are related to somatic health and basic function, including decreased use of health services, improved immune functioning, and a boost in grades or occupational performance.1 Patients who participate in expressive writing also have demonstrated improvements in distress, negative affect, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.1,2 Although improvement in PTSD symptoms with expressive writing has varied across studies, it appears that patients with PTSD who score high in trait negative emotion may receive the most benefit from the practice.3

Why does it work?