User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Serious Mental Illness Tied to Multiple Physical Illnesses

Serious mental illness (SMI), including bipolar disorder or schizophrenia spectrum disorders, is associated with a twofold increased risk for comorbid physical illness, results of a new meta-analysis showed.

“Although treatment of physical and mental health remains siloed in many health services globally, the high prevalence of physical multimorbidity attests to the urgent need for integrated care models that address both physical and mental health outcomes in people with severe mental illness,” the authors, led by Sean Halstead, MD, of The University of Queensland Medical School in Brisbane, Australia, wrote.

The findings were published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

Shorter Lifespan?

SMI is associated with reduced life expectancy, and experts speculate that additional chronic illnesses — whether physical or psychiatric — may underlie this association.

While previous research has paired SMI with comorbid physical illnesses, the researchers noted that this study is the first to focus on both physical and psychiatric multimorbidity in individuals with SMI.

The investigators conducted a meta-analysis of 82 observational studies comprising 1.6 million individuals with SMI and 13.2 million control subjects to determine the risk for physical or psychiatric multimorbidity.

Studies were included if participants were diagnosed with either a schizophrenia spectrum disorder or bipolar disorder, and the study assessed either physical multimorbidity (at least two physical health conditions) or psychiatric multimorbidity (at least three psychiatric conditions), including the initial SMI.

Investigators found that individuals with SMI had more than a twofold increased risk for physical multimorbidity than those without SMI (odds ratio [OR], 2.40; 95% CI, 1.57-3.65; P = .0009).

Physical multimorbidity, which included cardiovascular, endocrine, neurological rental, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and infectious disorders, was prevalent at similar rates in both schizophrenia spectrum disorder and bipolar disorder.

The ratio of physical multimorbidity was about four times higher in younger populations with SMI (mean age ≤ 40; OR, 3.99; 95% CI, 1.43-11.10) than in older populations (mean age > 40; OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 0.96-2.51; subgroup differences, P = .0013).

In terms of absolute prevalence, 25% of those with SMI had a physical multimorbidity, and 14% had a psychiatric multimorbidity, which were primarily anxiety and substance use disorders.

Investigators speculated that physical multimorbidity in SMI could stem from side effects of psychotropic medications, which are known to cause rapid cardiometabolic changes, including weight gain. In addition, lifestyle factors or nonmodifiable risk factors could also contribute to physical multimorbidity.

The study’s limitations included its small sample sizes for subgroup analyses and insufficient analysis for significant covariates, including smoking rates and symptom severity.

“While health services and treatment guidelines often operate on the assumption that individuals have a single principal diagnosis, these results attest to the clinical complexity many people with severe mental illness face in relation to burden of chronic disease,” the investigators wrote. They added that a greater understanding of the epidemiological manifestations of multimorbidity in SMI is “imperative.”

There was no source of funding for this study. Dr. Halstead is supported by the Australian Research Training Program scholarship. Other disclosures were noted in the original article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Serious mental illness (SMI), including bipolar disorder or schizophrenia spectrum disorders, is associated with a twofold increased risk for comorbid physical illness, results of a new meta-analysis showed.

“Although treatment of physical and mental health remains siloed in many health services globally, the high prevalence of physical multimorbidity attests to the urgent need for integrated care models that address both physical and mental health outcomes in people with severe mental illness,” the authors, led by Sean Halstead, MD, of The University of Queensland Medical School in Brisbane, Australia, wrote.

The findings were published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

Shorter Lifespan?

SMI is associated with reduced life expectancy, and experts speculate that additional chronic illnesses — whether physical or psychiatric — may underlie this association.

While previous research has paired SMI with comorbid physical illnesses, the researchers noted that this study is the first to focus on both physical and psychiatric multimorbidity in individuals with SMI.

The investigators conducted a meta-analysis of 82 observational studies comprising 1.6 million individuals with SMI and 13.2 million control subjects to determine the risk for physical or psychiatric multimorbidity.

Studies were included if participants were diagnosed with either a schizophrenia spectrum disorder or bipolar disorder, and the study assessed either physical multimorbidity (at least two physical health conditions) or psychiatric multimorbidity (at least three psychiatric conditions), including the initial SMI.

Investigators found that individuals with SMI had more than a twofold increased risk for physical multimorbidity than those without SMI (odds ratio [OR], 2.40; 95% CI, 1.57-3.65; P = .0009).

Physical multimorbidity, which included cardiovascular, endocrine, neurological rental, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and infectious disorders, was prevalent at similar rates in both schizophrenia spectrum disorder and bipolar disorder.

The ratio of physical multimorbidity was about four times higher in younger populations with SMI (mean age ≤ 40; OR, 3.99; 95% CI, 1.43-11.10) than in older populations (mean age > 40; OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 0.96-2.51; subgroup differences, P = .0013).

In terms of absolute prevalence, 25% of those with SMI had a physical multimorbidity, and 14% had a psychiatric multimorbidity, which were primarily anxiety and substance use disorders.

Investigators speculated that physical multimorbidity in SMI could stem from side effects of psychotropic medications, which are known to cause rapid cardiometabolic changes, including weight gain. In addition, lifestyle factors or nonmodifiable risk factors could also contribute to physical multimorbidity.

The study’s limitations included its small sample sizes for subgroup analyses and insufficient analysis for significant covariates, including smoking rates and symptom severity.

“While health services and treatment guidelines often operate on the assumption that individuals have a single principal diagnosis, these results attest to the clinical complexity many people with severe mental illness face in relation to burden of chronic disease,” the investigators wrote. They added that a greater understanding of the epidemiological manifestations of multimorbidity in SMI is “imperative.”

There was no source of funding for this study. Dr. Halstead is supported by the Australian Research Training Program scholarship. Other disclosures were noted in the original article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Serious mental illness (SMI), including bipolar disorder or schizophrenia spectrum disorders, is associated with a twofold increased risk for comorbid physical illness, results of a new meta-analysis showed.

“Although treatment of physical and mental health remains siloed in many health services globally, the high prevalence of physical multimorbidity attests to the urgent need for integrated care models that address both physical and mental health outcomes in people with severe mental illness,” the authors, led by Sean Halstead, MD, of The University of Queensland Medical School in Brisbane, Australia, wrote.

The findings were published online in The Lancet Psychiatry.

Shorter Lifespan?

SMI is associated with reduced life expectancy, and experts speculate that additional chronic illnesses — whether physical or psychiatric — may underlie this association.

While previous research has paired SMI with comorbid physical illnesses, the researchers noted that this study is the first to focus on both physical and psychiatric multimorbidity in individuals with SMI.

The investigators conducted a meta-analysis of 82 observational studies comprising 1.6 million individuals with SMI and 13.2 million control subjects to determine the risk for physical or psychiatric multimorbidity.

Studies were included if participants were diagnosed with either a schizophrenia spectrum disorder or bipolar disorder, and the study assessed either physical multimorbidity (at least two physical health conditions) or psychiatric multimorbidity (at least three psychiatric conditions), including the initial SMI.

Investigators found that individuals with SMI had more than a twofold increased risk for physical multimorbidity than those without SMI (odds ratio [OR], 2.40; 95% CI, 1.57-3.65; P = .0009).

Physical multimorbidity, which included cardiovascular, endocrine, neurological rental, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and infectious disorders, was prevalent at similar rates in both schizophrenia spectrum disorder and bipolar disorder.

The ratio of physical multimorbidity was about four times higher in younger populations with SMI (mean age ≤ 40; OR, 3.99; 95% CI, 1.43-11.10) than in older populations (mean age > 40; OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 0.96-2.51; subgroup differences, P = .0013).

In terms of absolute prevalence, 25% of those with SMI had a physical multimorbidity, and 14% had a psychiatric multimorbidity, which were primarily anxiety and substance use disorders.

Investigators speculated that physical multimorbidity in SMI could stem from side effects of psychotropic medications, which are known to cause rapid cardiometabolic changes, including weight gain. In addition, lifestyle factors or nonmodifiable risk factors could also contribute to physical multimorbidity.

The study’s limitations included its small sample sizes for subgroup analyses and insufficient analysis for significant covariates, including smoking rates and symptom severity.

“While health services and treatment guidelines often operate on the assumption that individuals have a single principal diagnosis, these results attest to the clinical complexity many people with severe mental illness face in relation to burden of chronic disease,” the investigators wrote. They added that a greater understanding of the epidemiological manifestations of multimorbidity in SMI is “imperative.”

There was no source of funding for this study. Dr. Halstead is supported by the Australian Research Training Program scholarship. Other disclosures were noted in the original article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

FROM THE LANCET PSYCHIATRY

CPAP Underperforms: The Sequel

A few months ago, I posted a column on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with the title, “CPAP Oversells and Underperforms.” To date, it has 299 likes and 90 comments, which are almost all negative. I’m glad to see that it’s generated interest, and I’d like to address some of the themes expressed in the posts.

Most comments were personal testimonies to the miracles of CPAP. These are important, and the point deserves emphasis. CPAP can provide significant improvements in daytime sleepiness and quality of life. I closed the original piece by acknowledging this important fact. Readers can be forgiven for missing it given that the title and text were otherwise disparaging of CPAP.

But several comments warrant a more in-depth discussion. The original piece focuses on CPAP and cardiovascular (CV) outcomes but made no mention of atrial fibrillation (AF) or ejection fraction (EF). The effects of CPAP on each are touted by cardiologists and PAP-pushers alike and are drivers of frequent referrals. It›s my fault for omitting them from the discussion.

AF is easy. The data is identical to all other things CPAP and CV. Based on biologic plausibility alone, the likelihood of a relationship between AF and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is similar to the odds that the Celtics raise an 18th banner come June. There’s hypoxia, intrathoracic pressure swings, sympathetic surges, and sleep state disruptions. It’s easy to get from there to arrhythmogenesis. There’s lots of observational noise, too, but no randomized proof that CPAP alters this relationship.

I found four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested CPAP’s effect on AF. I’ll save you the suspense; they were all negative. One even found a signal for more adverse events in the CPAP group. These studies have several positive qualities: They enrolled patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and high oxygen desaturation indices, adherence averaged more than 4 hours across all groups in all trials, and the methods for assessing the AF outcomes differed slightly. There’s also a lot not to like: The sample sizes were small, only one trial enrolled “sleepy” patients (as assessed by the Epworth Sleepiness Score), and follow-up was short.

To paraphrase Carl Sagan, “absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence.” As a statistician would say, type II error cannot be excluded by these RCTs. In medicine, however, the burden of proof falls on demonstrating efficacy. If we treat before concluding that a therapy works, we risk wasting time, money, medical resources, and the most precious of patient commodities: the energy required for behavior change. In their response to letters to the editor, the authors of the third RCT summarize the CPAP, AF, and CV disease data far better than I ever could. They sound the same words of caution and come out against screening patients with AF for OSA.

The story for CPAP’s effects on EF is similar though muddier. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for heart failure cite a meta-analysis showing that CPAP improves left ventricular EF. In 2019, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) CPAP guidelines included a systematic review and meta-analysis that found that CPAP has no effect on left ventricular EF in patients with or without heart failure.

There are a million reasons why two systematic reviews on the same topic might come to different conclusions. In this case, the included studies only partially overlap, and broadly speaking, it appears the authors made trade-offs. The review cited by the ACC/AHA had broader inclusion and significantly more patients and paid for it in heterogeneity (I2 in the 80%-90% range). The AASM analysis achieved 0% heterogeneity but limited inclusion to fewer than 100 patients. Across both, the improvement in EF was 2%- 5% at a minimally clinically important difference of 4%. Hardly convincing.

In summary, the road to negative trials and patient harm has always been paved with observational signal and biologic plausibility. Throw in some intellectual and academic bias, and you’ve created the perfect storm of therapeutic overconfidence.

Dr. Holley is a professor in the department of medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and a physician at Pulmonary/Sleep and Critical Care Medicine, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington. He disclosed ties to Metapharm Inc., CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

A few months ago, I posted a column on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with the title, “CPAP Oversells and Underperforms.” To date, it has 299 likes and 90 comments, which are almost all negative. I’m glad to see that it’s generated interest, and I’d like to address some of the themes expressed in the posts.

Most comments were personal testimonies to the miracles of CPAP. These are important, and the point deserves emphasis. CPAP can provide significant improvements in daytime sleepiness and quality of life. I closed the original piece by acknowledging this important fact. Readers can be forgiven for missing it given that the title and text were otherwise disparaging of CPAP.

But several comments warrant a more in-depth discussion. The original piece focuses on CPAP and cardiovascular (CV) outcomes but made no mention of atrial fibrillation (AF) or ejection fraction (EF). The effects of CPAP on each are touted by cardiologists and PAP-pushers alike and are drivers of frequent referrals. It›s my fault for omitting them from the discussion.

AF is easy. The data is identical to all other things CPAP and CV. Based on biologic plausibility alone, the likelihood of a relationship between AF and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is similar to the odds that the Celtics raise an 18th banner come June. There’s hypoxia, intrathoracic pressure swings, sympathetic surges, and sleep state disruptions. It’s easy to get from there to arrhythmogenesis. There’s lots of observational noise, too, but no randomized proof that CPAP alters this relationship.

I found four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested CPAP’s effect on AF. I’ll save you the suspense; they were all negative. One even found a signal for more adverse events in the CPAP group. These studies have several positive qualities: They enrolled patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and high oxygen desaturation indices, adherence averaged more than 4 hours across all groups in all trials, and the methods for assessing the AF outcomes differed slightly. There’s also a lot not to like: The sample sizes were small, only one trial enrolled “sleepy” patients (as assessed by the Epworth Sleepiness Score), and follow-up was short.

To paraphrase Carl Sagan, “absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence.” As a statistician would say, type II error cannot be excluded by these RCTs. In medicine, however, the burden of proof falls on demonstrating efficacy. If we treat before concluding that a therapy works, we risk wasting time, money, medical resources, and the most precious of patient commodities: the energy required for behavior change. In their response to letters to the editor, the authors of the third RCT summarize the CPAP, AF, and CV disease data far better than I ever could. They sound the same words of caution and come out against screening patients with AF for OSA.

The story for CPAP’s effects on EF is similar though muddier. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for heart failure cite a meta-analysis showing that CPAP improves left ventricular EF. In 2019, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) CPAP guidelines included a systematic review and meta-analysis that found that CPAP has no effect on left ventricular EF in patients with or without heart failure.

There are a million reasons why two systematic reviews on the same topic might come to different conclusions. In this case, the included studies only partially overlap, and broadly speaking, it appears the authors made trade-offs. The review cited by the ACC/AHA had broader inclusion and significantly more patients and paid for it in heterogeneity (I2 in the 80%-90% range). The AASM analysis achieved 0% heterogeneity but limited inclusion to fewer than 100 patients. Across both, the improvement in EF was 2%- 5% at a minimally clinically important difference of 4%. Hardly convincing.

In summary, the road to negative trials and patient harm has always been paved with observational signal and biologic plausibility. Throw in some intellectual and academic bias, and you’ve created the perfect storm of therapeutic overconfidence.

Dr. Holley is a professor in the department of medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and a physician at Pulmonary/Sleep and Critical Care Medicine, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington. He disclosed ties to Metapharm Inc., CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

A few months ago, I posted a column on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with the title, “CPAP Oversells and Underperforms.” To date, it has 299 likes and 90 comments, which are almost all negative. I’m glad to see that it’s generated interest, and I’d like to address some of the themes expressed in the posts.

Most comments were personal testimonies to the miracles of CPAP. These are important, and the point deserves emphasis. CPAP can provide significant improvements in daytime sleepiness and quality of life. I closed the original piece by acknowledging this important fact. Readers can be forgiven for missing it given that the title and text were otherwise disparaging of CPAP.

But several comments warrant a more in-depth discussion. The original piece focuses on CPAP and cardiovascular (CV) outcomes but made no mention of atrial fibrillation (AF) or ejection fraction (EF). The effects of CPAP on each are touted by cardiologists and PAP-pushers alike and are drivers of frequent referrals. It›s my fault for omitting them from the discussion.

AF is easy. The data is identical to all other things CPAP and CV. Based on biologic plausibility alone, the likelihood of a relationship between AF and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is similar to the odds that the Celtics raise an 18th banner come June. There’s hypoxia, intrathoracic pressure swings, sympathetic surges, and sleep state disruptions. It’s easy to get from there to arrhythmogenesis. There’s lots of observational noise, too, but no randomized proof that CPAP alters this relationship.

I found four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that tested CPAP’s effect on AF. I’ll save you the suspense; they were all negative. One even found a signal for more adverse events in the CPAP group. These studies have several positive qualities: They enrolled patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea and high oxygen desaturation indices, adherence averaged more than 4 hours across all groups in all trials, and the methods for assessing the AF outcomes differed slightly. There’s also a lot not to like: The sample sizes were small, only one trial enrolled “sleepy” patients (as assessed by the Epworth Sleepiness Score), and follow-up was short.

To paraphrase Carl Sagan, “absence of evidence does not equal evidence of absence.” As a statistician would say, type II error cannot be excluded by these RCTs. In medicine, however, the burden of proof falls on demonstrating efficacy. If we treat before concluding that a therapy works, we risk wasting time, money, medical resources, and the most precious of patient commodities: the energy required for behavior change. In their response to letters to the editor, the authors of the third RCT summarize the CPAP, AF, and CV disease data far better than I ever could. They sound the same words of caution and come out against screening patients with AF for OSA.

The story for CPAP’s effects on EF is similar though muddier. The American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines for heart failure cite a meta-analysis showing that CPAP improves left ventricular EF. In 2019, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) CPAP guidelines included a systematic review and meta-analysis that found that CPAP has no effect on left ventricular EF in patients with or without heart failure.

There are a million reasons why two systematic reviews on the same topic might come to different conclusions. In this case, the included studies only partially overlap, and broadly speaking, it appears the authors made trade-offs. The review cited by the ACC/AHA had broader inclusion and significantly more patients and paid for it in heterogeneity (I2 in the 80%-90% range). The AASM analysis achieved 0% heterogeneity but limited inclusion to fewer than 100 patients. Across both, the improvement in EF was 2%- 5% at a minimally clinically important difference of 4%. Hardly convincing.

In summary, the road to negative trials and patient harm has always been paved with observational signal and biologic plausibility. Throw in some intellectual and academic bias, and you’ve created the perfect storm of therapeutic overconfidence.

Dr. Holley is a professor in the department of medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Maryland, and a physician at Pulmonary/Sleep and Critical Care Medicine, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington. He disclosed ties to Metapharm Inc., CHEST College, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Why Cardiac Biomarkers Don’t Help Predict Heart Disease

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s the counterintuitive stuff in epidemiology that always really interests me. One intuition many of us have is that if a risk factor is significantly associated with an outcome, knowledge of that risk factor would help to predict that outcome. Makes sense. Feels right.

But it’s not right. Not always.

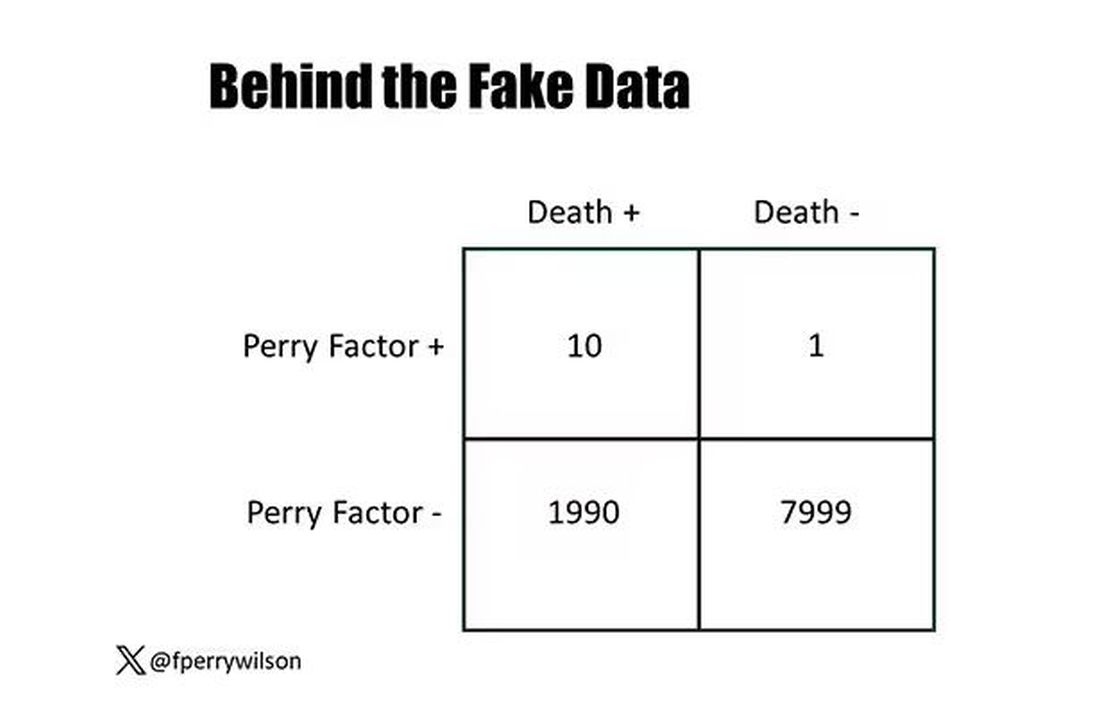

Here’s a fake example to illustrate my point. Let’s say we have 10,000 individuals who we follow for 10 years and 2000 of them die. (It’s been a rough decade.) At baseline, I measured a novel biomarker, the Perry Factor, in everyone. To keep it simple, the Perry Factor has only two values: 0 or 1.

I then do a standard associational analysis and find that individuals who are positive for the Perry Factor have a 40-fold higher odds of death than those who are negative for it. I am beginning to reconsider ascribing my good name to this biomarker. This is a highly statistically significant result — a P value <.001.

Clearly, knowledge of the Perry Factor should help me predict who will die in the cohort. I evaluate predictive power using a metric called the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC, referred to as the C-statistic in time-to-event studies). It tells you, given two people — one who dies and one who doesn’t — how frequently you “pick” the right person, given the knowledge of their Perry Factor.

A C-statistic of 0.5, or 50%, would mean the Perry Factor gives you no better results than a coin flip; it’s chance. A C-statistic of 1 is perfect prediction. So, what will the C-statistic be, given the incredibly strong association of the Perry Factor with outcomes? 0.9? 0.95?

0.5024. Almost useless.

Let’s figure out why strength of association and usefulness for prediction are not always the same thing.

I constructed my fake Perry Factor dataset quite carefully to illustrate this point. Let me show you what happened. What you see here is a breakdown of the patients in my fake study. You can see that just 11 of them were Perry Factor positive, but 10 of those 11 ended up dying.

That’s quite unlikely by chance alone. It really does appear that if you have Perry Factor, your risk for death is much higher. But the reason that Perry Factor is a bad predictor is because it is so rare in the population. Sure, you can use it to correctly predict the outcome of 10 of the 11 people who have it, but the vast majority of people don’t have Perry Factor. It’s useless to distinguish who will die vs who will live in that population.

Why have I spent so much time trying to reverse our intuition that strength of association and strength of predictive power must be related? Because it helps to explain this paper, “Prognostic Value of Cardiovascular Biomarkers in the Population,” appearing in JAMA, which is a very nice piece of work trying to help us better predict cardiovascular disease.

I don’t need to tell you that cardiovascular disease is the number-one killer in this country and most of the world. I don’t need to tell you that we have really good preventive therapies and lifestyle interventions that can reduce the risk. But it would be nice to know in whom, specifically, we should use those interventions.

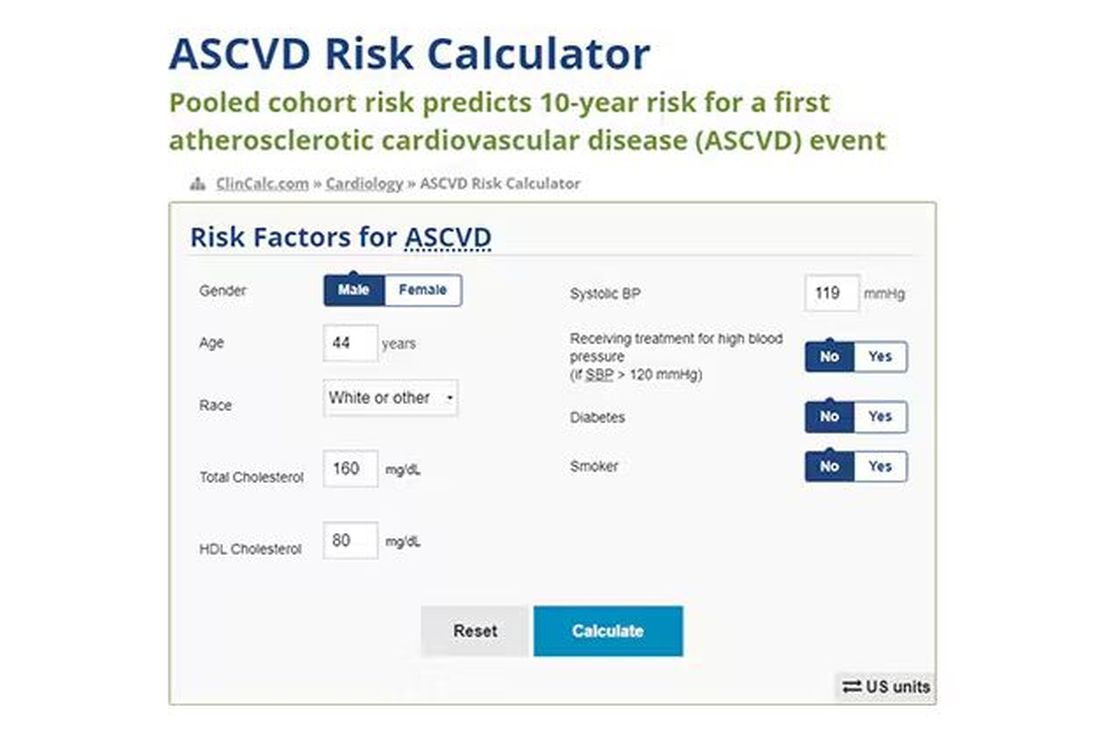

Cardiovascular risk scores, to date, are pretty simple. The most common one in use in the United States, the pooled cohort risk equation, has nine variables, two of which require a cholesterol panel and one a blood pressure test. It’s easy and it’s pretty accurate.

Using the score from the pooled cohort risk calculator, you get a C-statistic as high as 0.82 when applied to Black women, a low of 0.71 when applied to Black men. Non-Black individuals are in the middle. Not bad. But, clearly, not perfect.

And aren’t we in the era of big data, the era of personalized medicine? We have dozens, maybe hundreds, of quantifiable biomarkers that are associated with subsequent heart disease. Surely, by adding these biomarkers into the risk equation, we can improve prediction. Right?

The JAMA study includes 164,054 patients pooled from 28 cohort studies from 12 countries. All the studies measured various key biomarkers at baseline and followed their participants for cardiovascular events like heart attack, stroke, coronary revascularization, and so on.

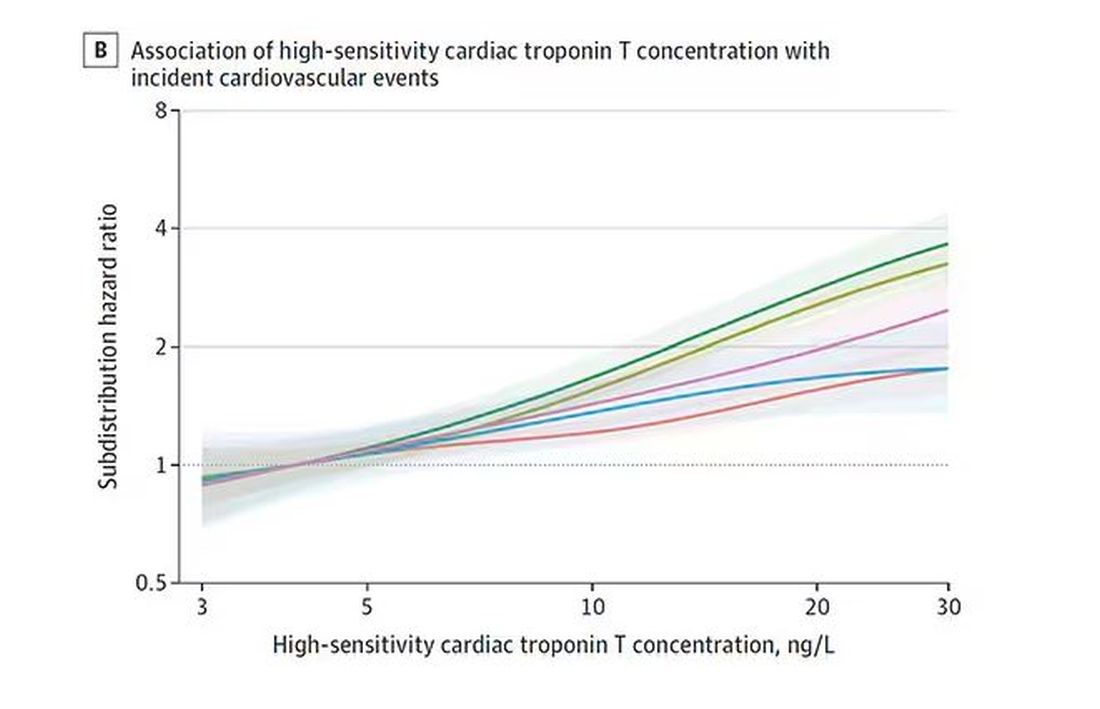

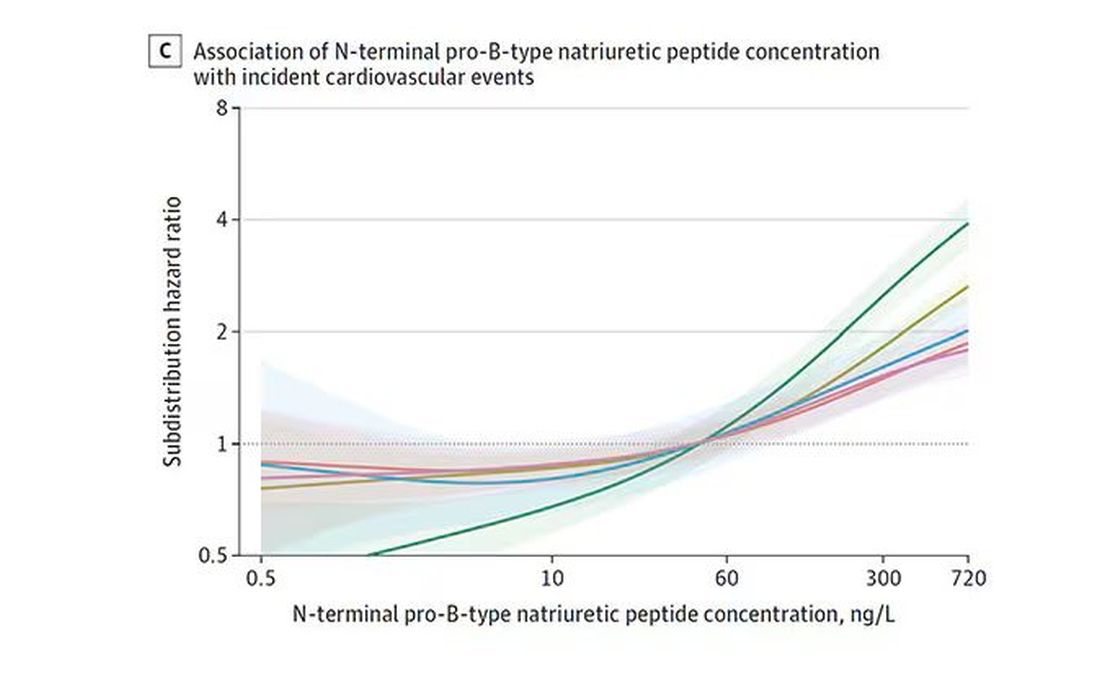

The biomarkers in question are really the big guns in this space: troponin, a marker of stress on the heart muscle; NT-proBNP, a marker of stretch on the heart muscle; and C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation. In every case, higher levels of these markers at baseline were associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular disease in the future.

Troponin T, shown here, has a basically linear risk with subsequent cardiovascular disease.

BNP seems to demonstrate more of a threshold effect, where levels above 60 start to associate with problems.

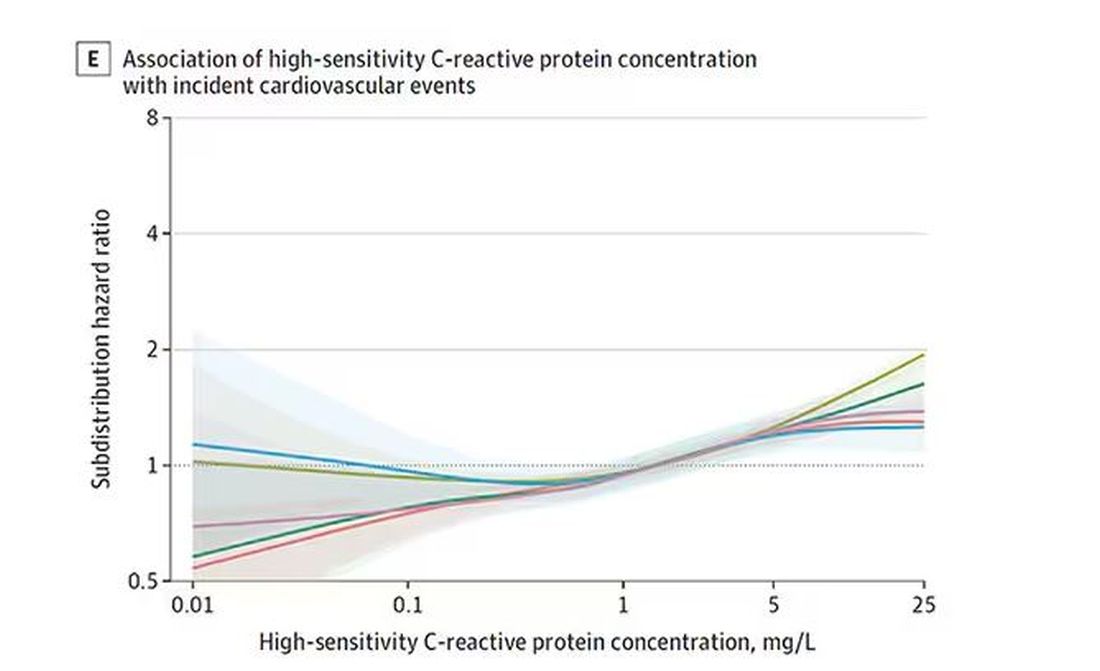

And CRP does a similar thing, with levels above 1.

All of these findings were statistically significant. If you have higher levels of one or more of these biomarkers, you are more likely to have cardiovascular disease in the future.

Of course, our old friend the pooled cohort risk equation is still here — in the background — requiring just that one blood test and measurement of blood pressure. Let’s talk about predictive power.

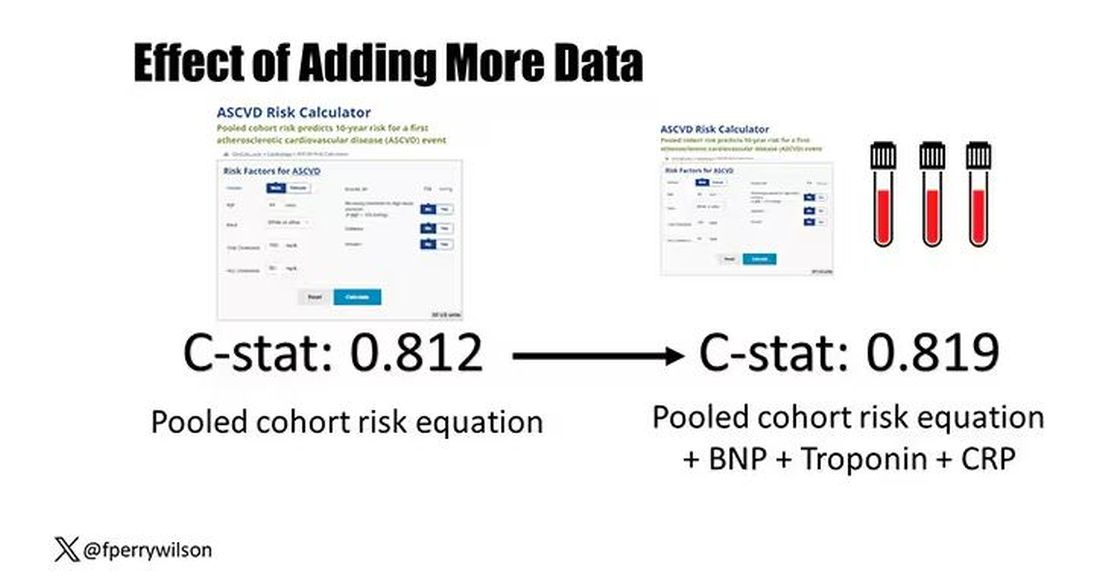

The pooled cohort risk equation score, in this study, had a C-statistic of 0.812.

By adding troponin, BNP, and CRP to the equation, the new C-statistic is 0.819. Barely any change.

Now, the authors looked at different types of prediction here. The greatest improvement in the AUC was seen when they tried to predict heart failure within 1 year of measurement; there the AUC improved by 0.04. But the presence of BNP as a biomarker and the short time window of 1 year makes me wonder whether this is really prediction at all or whether they were essentially just diagnosing people with existing heart failure.

Why does this happen? Why do these promising biomarkers, clearly associated with bad outcomes, fail to improve our ability to predict the future? I already gave one example, which has to do with how the markers are distributed in the population. But even more relevant here is that the new markers will only improve prediction insofar as they are not already represented in the old predictive model.

Of course, BNP, for example, wasn’t in the old model. But smoking was. Diabetes was. Blood pressure was. All of that data might actually tell you something about the patient’s BNP through their mutual correlation. And improvement in prediction requires new information.

This is actually why I consider this a really successful study. We need to do studies like this to help us find what those new sources of information might be.

We will never get to a C-statistic of 1. Perfect prediction is the domain of palm readers and astrophysicists. But better prediction is always possible through data. The big question, of course, is which data?

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s the counterintuitive stuff in epidemiology that always really interests me. One intuition many of us have is that if a risk factor is significantly associated with an outcome, knowledge of that risk factor would help to predict that outcome. Makes sense. Feels right.

But it’s not right. Not always.

Here’s a fake example to illustrate my point. Let’s say we have 10,000 individuals who we follow for 10 years and 2000 of them die. (It’s been a rough decade.) At baseline, I measured a novel biomarker, the Perry Factor, in everyone. To keep it simple, the Perry Factor has only two values: 0 or 1.

I then do a standard associational analysis and find that individuals who are positive for the Perry Factor have a 40-fold higher odds of death than those who are negative for it. I am beginning to reconsider ascribing my good name to this biomarker. This is a highly statistically significant result — a P value <.001.

Clearly, knowledge of the Perry Factor should help me predict who will die in the cohort. I evaluate predictive power using a metric called the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC, referred to as the C-statistic in time-to-event studies). It tells you, given two people — one who dies and one who doesn’t — how frequently you “pick” the right person, given the knowledge of their Perry Factor.

A C-statistic of 0.5, or 50%, would mean the Perry Factor gives you no better results than a coin flip; it’s chance. A C-statistic of 1 is perfect prediction. So, what will the C-statistic be, given the incredibly strong association of the Perry Factor with outcomes? 0.9? 0.95?

0.5024. Almost useless.

Let’s figure out why strength of association and usefulness for prediction are not always the same thing.

I constructed my fake Perry Factor dataset quite carefully to illustrate this point. Let me show you what happened. What you see here is a breakdown of the patients in my fake study. You can see that just 11 of them were Perry Factor positive, but 10 of those 11 ended up dying.

That’s quite unlikely by chance alone. It really does appear that if you have Perry Factor, your risk for death is much higher. But the reason that Perry Factor is a bad predictor is because it is so rare in the population. Sure, you can use it to correctly predict the outcome of 10 of the 11 people who have it, but the vast majority of people don’t have Perry Factor. It’s useless to distinguish who will die vs who will live in that population.

Why have I spent so much time trying to reverse our intuition that strength of association and strength of predictive power must be related? Because it helps to explain this paper, “Prognostic Value of Cardiovascular Biomarkers in the Population,” appearing in JAMA, which is a very nice piece of work trying to help us better predict cardiovascular disease.

I don’t need to tell you that cardiovascular disease is the number-one killer in this country and most of the world. I don’t need to tell you that we have really good preventive therapies and lifestyle interventions that can reduce the risk. But it would be nice to know in whom, specifically, we should use those interventions.

Cardiovascular risk scores, to date, are pretty simple. The most common one in use in the United States, the pooled cohort risk equation, has nine variables, two of which require a cholesterol panel and one a blood pressure test. It’s easy and it’s pretty accurate.

Using the score from the pooled cohort risk calculator, you get a C-statistic as high as 0.82 when applied to Black women, a low of 0.71 when applied to Black men. Non-Black individuals are in the middle. Not bad. But, clearly, not perfect.

And aren’t we in the era of big data, the era of personalized medicine? We have dozens, maybe hundreds, of quantifiable biomarkers that are associated with subsequent heart disease. Surely, by adding these biomarkers into the risk equation, we can improve prediction. Right?

The JAMA study includes 164,054 patients pooled from 28 cohort studies from 12 countries. All the studies measured various key biomarkers at baseline and followed their participants for cardiovascular events like heart attack, stroke, coronary revascularization, and so on.

The biomarkers in question are really the big guns in this space: troponin, a marker of stress on the heart muscle; NT-proBNP, a marker of stretch on the heart muscle; and C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation. In every case, higher levels of these markers at baseline were associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular disease in the future.

Troponin T, shown here, has a basically linear risk with subsequent cardiovascular disease.

BNP seems to demonstrate more of a threshold effect, where levels above 60 start to associate with problems.

And CRP does a similar thing, with levels above 1.

All of these findings were statistically significant. If you have higher levels of one or more of these biomarkers, you are more likely to have cardiovascular disease in the future.

Of course, our old friend the pooled cohort risk equation is still here — in the background — requiring just that one blood test and measurement of blood pressure. Let’s talk about predictive power.

The pooled cohort risk equation score, in this study, had a C-statistic of 0.812.

By adding troponin, BNP, and CRP to the equation, the new C-statistic is 0.819. Barely any change.

Now, the authors looked at different types of prediction here. The greatest improvement in the AUC was seen when they tried to predict heart failure within 1 year of measurement; there the AUC improved by 0.04. But the presence of BNP as a biomarker and the short time window of 1 year makes me wonder whether this is really prediction at all or whether they were essentially just diagnosing people with existing heart failure.

Why does this happen? Why do these promising biomarkers, clearly associated with bad outcomes, fail to improve our ability to predict the future? I already gave one example, which has to do with how the markers are distributed in the population. But even more relevant here is that the new markers will only improve prediction insofar as they are not already represented in the old predictive model.

Of course, BNP, for example, wasn’t in the old model. But smoking was. Diabetes was. Blood pressure was. All of that data might actually tell you something about the patient’s BNP through their mutual correlation. And improvement in prediction requires new information.

This is actually why I consider this a really successful study. We need to do studies like this to help us find what those new sources of information might be.

We will never get to a C-statistic of 1. Perfect prediction is the domain of palm readers and astrophysicists. But better prediction is always possible through data. The big question, of course, is which data?

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

It’s the counterintuitive stuff in epidemiology that always really interests me. One intuition many of us have is that if a risk factor is significantly associated with an outcome, knowledge of that risk factor would help to predict that outcome. Makes sense. Feels right.

But it’s not right. Not always.

Here’s a fake example to illustrate my point. Let’s say we have 10,000 individuals who we follow for 10 years and 2000 of them die. (It’s been a rough decade.) At baseline, I measured a novel biomarker, the Perry Factor, in everyone. To keep it simple, the Perry Factor has only two values: 0 or 1.

I then do a standard associational analysis and find that individuals who are positive for the Perry Factor have a 40-fold higher odds of death than those who are negative for it. I am beginning to reconsider ascribing my good name to this biomarker. This is a highly statistically significant result — a P value <.001.

Clearly, knowledge of the Perry Factor should help me predict who will die in the cohort. I evaluate predictive power using a metric called the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC, referred to as the C-statistic in time-to-event studies). It tells you, given two people — one who dies and one who doesn’t — how frequently you “pick” the right person, given the knowledge of their Perry Factor.

A C-statistic of 0.5, or 50%, would mean the Perry Factor gives you no better results than a coin flip; it’s chance. A C-statistic of 1 is perfect prediction. So, what will the C-statistic be, given the incredibly strong association of the Perry Factor with outcomes? 0.9? 0.95?

0.5024. Almost useless.

Let’s figure out why strength of association and usefulness for prediction are not always the same thing.

I constructed my fake Perry Factor dataset quite carefully to illustrate this point. Let me show you what happened. What you see here is a breakdown of the patients in my fake study. You can see that just 11 of them were Perry Factor positive, but 10 of those 11 ended up dying.

That’s quite unlikely by chance alone. It really does appear that if you have Perry Factor, your risk for death is much higher. But the reason that Perry Factor is a bad predictor is because it is so rare in the population. Sure, you can use it to correctly predict the outcome of 10 of the 11 people who have it, but the vast majority of people don’t have Perry Factor. It’s useless to distinguish who will die vs who will live in that population.

Why have I spent so much time trying to reverse our intuition that strength of association and strength of predictive power must be related? Because it helps to explain this paper, “Prognostic Value of Cardiovascular Biomarkers in the Population,” appearing in JAMA, which is a very nice piece of work trying to help us better predict cardiovascular disease.

I don’t need to tell you that cardiovascular disease is the number-one killer in this country and most of the world. I don’t need to tell you that we have really good preventive therapies and lifestyle interventions that can reduce the risk. But it would be nice to know in whom, specifically, we should use those interventions.

Cardiovascular risk scores, to date, are pretty simple. The most common one in use in the United States, the pooled cohort risk equation, has nine variables, two of which require a cholesterol panel and one a blood pressure test. It’s easy and it’s pretty accurate.

Using the score from the pooled cohort risk calculator, you get a C-statistic as high as 0.82 when applied to Black women, a low of 0.71 when applied to Black men. Non-Black individuals are in the middle. Not bad. But, clearly, not perfect.

And aren’t we in the era of big data, the era of personalized medicine? We have dozens, maybe hundreds, of quantifiable biomarkers that are associated with subsequent heart disease. Surely, by adding these biomarkers into the risk equation, we can improve prediction. Right?

The JAMA study includes 164,054 patients pooled from 28 cohort studies from 12 countries. All the studies measured various key biomarkers at baseline and followed their participants for cardiovascular events like heart attack, stroke, coronary revascularization, and so on.

The biomarkers in question are really the big guns in this space: troponin, a marker of stress on the heart muscle; NT-proBNP, a marker of stretch on the heart muscle; and C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation. In every case, higher levels of these markers at baseline were associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular disease in the future.

Troponin T, shown here, has a basically linear risk with subsequent cardiovascular disease.

BNP seems to demonstrate more of a threshold effect, where levels above 60 start to associate with problems.

And CRP does a similar thing, with levels above 1.

All of these findings were statistically significant. If you have higher levels of one or more of these biomarkers, you are more likely to have cardiovascular disease in the future.

Of course, our old friend the pooled cohort risk equation is still here — in the background — requiring just that one blood test and measurement of blood pressure. Let’s talk about predictive power.

The pooled cohort risk equation score, in this study, had a C-statistic of 0.812.

By adding troponin, BNP, and CRP to the equation, the new C-statistic is 0.819. Barely any change.

Now, the authors looked at different types of prediction here. The greatest improvement in the AUC was seen when they tried to predict heart failure within 1 year of measurement; there the AUC improved by 0.04. But the presence of BNP as a biomarker and the short time window of 1 year makes me wonder whether this is really prediction at all or whether they were essentially just diagnosing people with existing heart failure.

Why does this happen? Why do these promising biomarkers, clearly associated with bad outcomes, fail to improve our ability to predict the future? I already gave one example, which has to do with how the markers are distributed in the population. But even more relevant here is that the new markers will only improve prediction insofar as they are not already represented in the old predictive model.

Of course, BNP, for example, wasn’t in the old model. But smoking was. Diabetes was. Blood pressure was. All of that data might actually tell you something about the patient’s BNP through their mutual correlation. And improvement in prediction requires new information.

This is actually why I consider this a really successful study. We need to do studies like this to help us find what those new sources of information might be.

We will never get to a C-statistic of 1. Perfect prediction is the domain of palm readers and astrophysicists. But better prediction is always possible through data. The big question, of course, is which data?

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Why Incorporating Obstetric History Matters for CVD Risk Management in Autoimmune Diseases

NEW YORK — Systemic autoimmune disease is well-recognized as a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), but less recognized as a cardiovascular risk factor is a history of pregnancy complications, including preeclampsia, and cardiologists and rheumatologists need to include an obstetric history when managing patients with autoimmune diseases, a specialist in reproductive health in rheumatology told attendees at the 4th Annual Cardiometabolic Risk in Inflammatory Conditions conference.

“Autoimmune diseases, lupus in particular, increase the risk for both cardiovascular disease and maternal placental syndromes,” Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, a professor at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City and a specialist in reproductive health issues in rheumatology patients, told attendees. “For those patients who have complications during pregnancy, it further increases their already increased risk for later cardiovascular disease.”

CVD Risk Double Whammy

A history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and problematic pregnancy can be a double whammy for CVD risk. Dr. Sammaritano cited a 2022 meta-analysis that showed patients with SLE had a 2.5 times greater risk for stroke and almost three times greater risk for myocardial infarction than people without SLE.

Maternal placental syndromes include pregnancy loss, restricted fetal growth, preeclampsia, premature membrane rupture, placental abruption, and intrauterine fetal demise, Dr. Sammaritano said. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, formerly called adverse pregnancy outcomes, she noted, include gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and eclampsia.

Pregnancy complications can have an adverse effect on the mother’s postpartum cardiovascular health, Dr. Sammaritano noted, a fact borne out by the cardiovascular health after maternal placental syndromes population-based retrospective cohort study and a 2007 meta-analysis that found a history of preeclampsia doubles the risk for venous thromboembolism, stroke, and ischemic heart disease up to 15 years after pregnancy.

“It is always important to obtain a reproductive health history from patients with autoimmune diseases,” Dr. Sammaritano told this news organization in an interview. “This is an integral part of any medical history. In the usual setting, this includes not only pregnancy history but also use of contraception in reproductive-aged women. Unplanned pregnancy can lead to adverse outcomes in the setting of active or severe autoimmune disease or when teratogenic medications are used.”

Pregnancy history can be a factor in a woman’s cardiovascular health more than 15 years postpartum, even if a woman is no longer planning a pregnancy or is menopausal. “As such, this history is important in assessing every woman’s risk profile for CVD in addition to usual traditional risk factors,” Dr. Sammaritano said.

“It is even more important for women with autoimmune disorders, who have been shown to have an already increased risk for CVD independent of their pregnancy history, likely related to a chronic inflammatory state and other autoimmune-related factors such as presence of antiphospholipid antibodies [aPL] or use of corticosteroids.”

Timing of disease onset is also an issue, she said. “In patients with SLE, for example, onset of CVD is much earlier than in the general population,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “As a result, these patients should likely be assessed for risk — both traditional and other risk factors — earlier than the general population, especially if an adverse obstetric history is present.”

At the younger end of the age continuum, women with autoimmune disease, including SLE and antiphospholipid syndrome, who are pregnant should be put on guideline-directed low-dose aspirin preeclampsia prophylaxis, Dr. Sammaritano said. “Whether every patient with SLE needs this is still uncertain, but certainly, those with a history of renal disease, hypertension, or aPL antibody clearly do,” she added.

The evidence supporting hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in these patients is controversial, but Dr. Sammaritano noted two meta-analyses, one in 2022 and the other in 2023, that showed that HCQ lowered the risk for preeclampsia in women.

“The clear benefit of HCQ in preventing maternal disease complications, including flare, means we recommend it regardless for all patients with SLE at baseline and during pregnancy [if tolerated],” Dr. Sammaritano said. “The benefit or optimal use of these medications in other autoimmune diseases is less studied and less certain.”

Dr. Sammaritano added in her presentation, “We really need better therapies and, hopefully, those will be on the way, but I think the takeaway message, particularly for practicing rheumatologists and cardiologists, is to ask the question about obstetric history. Many of us don’t. It doesn’t seem relevant in the moment, but it really is in terms of the patient’s long-term risk for cardiovascular disease.”

The Case for Treatment During Pregnancy

Prophylaxis against pregnancy complications in patients with autoimmune disease may be achievable, Taryn Youngstein, MBBS, consultant rheumatologist and codirector of the Centre of Excellence in Vasculitis Research, Imperial College London, London, England, told this news organization after Dr. Sammaritano’s presentation. At the 2023 American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting, her group reported the safety and effectiveness of continuing tocilizumab in pregnant women with Takayasu arteritis, a large-vessel vasculitis predominantly affecting women of reproductive age.

“What traditionally happens is you would stop the biologic particularly before the third trimester because of safety and concerns that the monoclonal antibody is actively transported across the placenta, which means the baby gets much more concentration of the drug than the mum,” Dr. Youngstein said.

It’s a situation physicians must monitor closely, she said. “The mum is donating their immune system to the baby, but they’re also donating drug.”

“In high-risk patients, we would share decision-making with the patient,” Dr. Youngstein continued. “We have decided it’s too high of a risk for us to stop the drug, so we have been continuing the interleukin-6 [IL-6] inhibitor throughout the entire pregnancy.”

The data from Dr. Youngstein’s group showed that pregnant women with Takayasu arteritis who continued IL-6 inhibition therapy all carried to term with healthy births.

“We’ve shown that it’s relatively safe to do that, but you have to be very careful in monitoring the baby,” she said. This includes not giving the infant any live vaccines at birth because it will have the high levels of IL-6 inhibition, she said.

Dr. Sammaritano and Dr. Youngstein had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW YORK — Systemic autoimmune disease is well-recognized as a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), but less recognized as a cardiovascular risk factor is a history of pregnancy complications, including preeclampsia, and cardiologists and rheumatologists need to include an obstetric history when managing patients with autoimmune diseases, a specialist in reproductive health in rheumatology told attendees at the 4th Annual Cardiometabolic Risk in Inflammatory Conditions conference.

“Autoimmune diseases, lupus in particular, increase the risk for both cardiovascular disease and maternal placental syndromes,” Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, a professor at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City and a specialist in reproductive health issues in rheumatology patients, told attendees. “For those patients who have complications during pregnancy, it further increases their already increased risk for later cardiovascular disease.”

CVD Risk Double Whammy

A history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and problematic pregnancy can be a double whammy for CVD risk. Dr. Sammaritano cited a 2022 meta-analysis that showed patients with SLE had a 2.5 times greater risk for stroke and almost three times greater risk for myocardial infarction than people without SLE.

Maternal placental syndromes include pregnancy loss, restricted fetal growth, preeclampsia, premature membrane rupture, placental abruption, and intrauterine fetal demise, Dr. Sammaritano said. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, formerly called adverse pregnancy outcomes, she noted, include gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and eclampsia.

Pregnancy complications can have an adverse effect on the mother’s postpartum cardiovascular health, Dr. Sammaritano noted, a fact borne out by the cardiovascular health after maternal placental syndromes population-based retrospective cohort study and a 2007 meta-analysis that found a history of preeclampsia doubles the risk for venous thromboembolism, stroke, and ischemic heart disease up to 15 years after pregnancy.

“It is always important to obtain a reproductive health history from patients with autoimmune diseases,” Dr. Sammaritano told this news organization in an interview. “This is an integral part of any medical history. In the usual setting, this includes not only pregnancy history but also use of contraception in reproductive-aged women. Unplanned pregnancy can lead to adverse outcomes in the setting of active or severe autoimmune disease or when teratogenic medications are used.”

Pregnancy history can be a factor in a woman’s cardiovascular health more than 15 years postpartum, even if a woman is no longer planning a pregnancy or is menopausal. “As such, this history is important in assessing every woman’s risk profile for CVD in addition to usual traditional risk factors,” Dr. Sammaritano said.

“It is even more important for women with autoimmune disorders, who have been shown to have an already increased risk for CVD independent of their pregnancy history, likely related to a chronic inflammatory state and other autoimmune-related factors such as presence of antiphospholipid antibodies [aPL] or use of corticosteroids.”

Timing of disease onset is also an issue, she said. “In patients with SLE, for example, onset of CVD is much earlier than in the general population,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “As a result, these patients should likely be assessed for risk — both traditional and other risk factors — earlier than the general population, especially if an adverse obstetric history is present.”

At the younger end of the age continuum, women with autoimmune disease, including SLE and antiphospholipid syndrome, who are pregnant should be put on guideline-directed low-dose aspirin preeclampsia prophylaxis, Dr. Sammaritano said. “Whether every patient with SLE needs this is still uncertain, but certainly, those with a history of renal disease, hypertension, or aPL antibody clearly do,” she added.

The evidence supporting hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in these patients is controversial, but Dr. Sammaritano noted two meta-analyses, one in 2022 and the other in 2023, that showed that HCQ lowered the risk for preeclampsia in women.

“The clear benefit of HCQ in preventing maternal disease complications, including flare, means we recommend it regardless for all patients with SLE at baseline and during pregnancy [if tolerated],” Dr. Sammaritano said. “The benefit or optimal use of these medications in other autoimmune diseases is less studied and less certain.”

Dr. Sammaritano added in her presentation, “We really need better therapies and, hopefully, those will be on the way, but I think the takeaway message, particularly for practicing rheumatologists and cardiologists, is to ask the question about obstetric history. Many of us don’t. It doesn’t seem relevant in the moment, but it really is in terms of the patient’s long-term risk for cardiovascular disease.”

The Case for Treatment During Pregnancy

Prophylaxis against pregnancy complications in patients with autoimmune disease may be achievable, Taryn Youngstein, MBBS, consultant rheumatologist and codirector of the Centre of Excellence in Vasculitis Research, Imperial College London, London, England, told this news organization after Dr. Sammaritano’s presentation. At the 2023 American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting, her group reported the safety and effectiveness of continuing tocilizumab in pregnant women with Takayasu arteritis, a large-vessel vasculitis predominantly affecting women of reproductive age.

“What traditionally happens is you would stop the biologic particularly before the third trimester because of safety and concerns that the monoclonal antibody is actively transported across the placenta, which means the baby gets much more concentration of the drug than the mum,” Dr. Youngstein said.

It’s a situation physicians must monitor closely, she said. “The mum is donating their immune system to the baby, but they’re also donating drug.”

“In high-risk patients, we would share decision-making with the patient,” Dr. Youngstein continued. “We have decided it’s too high of a risk for us to stop the drug, so we have been continuing the interleukin-6 [IL-6] inhibitor throughout the entire pregnancy.”

The data from Dr. Youngstein’s group showed that pregnant women with Takayasu arteritis who continued IL-6 inhibition therapy all carried to term with healthy births.

“We’ve shown that it’s relatively safe to do that, but you have to be very careful in monitoring the baby,” she said. This includes not giving the infant any live vaccines at birth because it will have the high levels of IL-6 inhibition, she said.

Dr. Sammaritano and Dr. Youngstein had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW YORK — Systemic autoimmune disease is well-recognized as a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), but less recognized as a cardiovascular risk factor is a history of pregnancy complications, including preeclampsia, and cardiologists and rheumatologists need to include an obstetric history when managing patients with autoimmune diseases, a specialist in reproductive health in rheumatology told attendees at the 4th Annual Cardiometabolic Risk in Inflammatory Conditions conference.

“Autoimmune diseases, lupus in particular, increase the risk for both cardiovascular disease and maternal placental syndromes,” Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, a professor at Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City and a specialist in reproductive health issues in rheumatology patients, told attendees. “For those patients who have complications during pregnancy, it further increases their already increased risk for later cardiovascular disease.”

CVD Risk Double Whammy

A history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and problematic pregnancy can be a double whammy for CVD risk. Dr. Sammaritano cited a 2022 meta-analysis that showed patients with SLE had a 2.5 times greater risk for stroke and almost three times greater risk for myocardial infarction than people without SLE.

Maternal placental syndromes include pregnancy loss, restricted fetal growth, preeclampsia, premature membrane rupture, placental abruption, and intrauterine fetal demise, Dr. Sammaritano said. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, formerly called adverse pregnancy outcomes, she noted, include gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and eclampsia.

Pregnancy complications can have an adverse effect on the mother’s postpartum cardiovascular health, Dr. Sammaritano noted, a fact borne out by the cardiovascular health after maternal placental syndromes population-based retrospective cohort study and a 2007 meta-analysis that found a history of preeclampsia doubles the risk for venous thromboembolism, stroke, and ischemic heart disease up to 15 years after pregnancy.

“It is always important to obtain a reproductive health history from patients with autoimmune diseases,” Dr. Sammaritano told this news organization in an interview. “This is an integral part of any medical history. In the usual setting, this includes not only pregnancy history but also use of contraception in reproductive-aged women. Unplanned pregnancy can lead to adverse outcomes in the setting of active or severe autoimmune disease or when teratogenic medications are used.”

Pregnancy history can be a factor in a woman’s cardiovascular health more than 15 years postpartum, even if a woman is no longer planning a pregnancy or is menopausal. “As such, this history is important in assessing every woman’s risk profile for CVD in addition to usual traditional risk factors,” Dr. Sammaritano said.

“It is even more important for women with autoimmune disorders, who have been shown to have an already increased risk for CVD independent of their pregnancy history, likely related to a chronic inflammatory state and other autoimmune-related factors such as presence of antiphospholipid antibodies [aPL] or use of corticosteroids.”

Timing of disease onset is also an issue, she said. “In patients with SLE, for example, onset of CVD is much earlier than in the general population,” Dr. Sammaritano said. “As a result, these patients should likely be assessed for risk — both traditional and other risk factors — earlier than the general population, especially if an adverse obstetric history is present.”

At the younger end of the age continuum, women with autoimmune disease, including SLE and antiphospholipid syndrome, who are pregnant should be put on guideline-directed low-dose aspirin preeclampsia prophylaxis, Dr. Sammaritano said. “Whether every patient with SLE needs this is still uncertain, but certainly, those with a history of renal disease, hypertension, or aPL antibody clearly do,” she added.

The evidence supporting hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in these patients is controversial, but Dr. Sammaritano noted two meta-analyses, one in 2022 and the other in 2023, that showed that HCQ lowered the risk for preeclampsia in women.

“The clear benefit of HCQ in preventing maternal disease complications, including flare, means we recommend it regardless for all patients with SLE at baseline and during pregnancy [if tolerated],” Dr. Sammaritano said. “The benefit or optimal use of these medications in other autoimmune diseases is less studied and less certain.”

Dr. Sammaritano added in her presentation, “We really need better therapies and, hopefully, those will be on the way, but I think the takeaway message, particularly for practicing rheumatologists and cardiologists, is to ask the question about obstetric history. Many of us don’t. It doesn’t seem relevant in the moment, but it really is in terms of the patient’s long-term risk for cardiovascular disease.”

The Case for Treatment During Pregnancy

Prophylaxis against pregnancy complications in patients with autoimmune disease may be achievable, Taryn Youngstein, MBBS, consultant rheumatologist and codirector of the Centre of Excellence in Vasculitis Research, Imperial College London, London, England, told this news organization after Dr. Sammaritano’s presentation. At the 2023 American College of Rheumatology Annual Meeting, her group reported the safety and effectiveness of continuing tocilizumab in pregnant women with Takayasu arteritis, a large-vessel vasculitis predominantly affecting women of reproductive age.

“What traditionally happens is you would stop the biologic particularly before the third trimester because of safety and concerns that the monoclonal antibody is actively transported across the placenta, which means the baby gets much more concentration of the drug than the mum,” Dr. Youngstein said.

It’s a situation physicians must monitor closely, she said. “The mum is donating their immune system to the baby, but they’re also donating drug.”

“In high-risk patients, we would share decision-making with the patient,” Dr. Youngstein continued. “We have decided it’s too high of a risk for us to stop the drug, so we have been continuing the interleukin-6 [IL-6] inhibitor throughout the entire pregnancy.”

The data from Dr. Youngstein’s group showed that pregnant women with Takayasu arteritis who continued IL-6 inhibition therapy all carried to term with healthy births.

“We’ve shown that it’s relatively safe to do that, but you have to be very careful in monitoring the baby,” she said. This includes not giving the infant any live vaccines at birth because it will have the high levels of IL-6 inhibition, she said.

Dr. Sammaritano and Dr. Youngstein had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

CVD Risk Rises With Higher NSAID Doses in Ankylosing Spondylitis

TOPLINE:

Higher doses of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) increase the risk for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) compared with lower doses.

METHODOLOGY:

- NSAIDs can suppress inflammation and relieve pain in patients with AS, but long-term treatment with NSAIDs poses concerns regarding gastrointestinal and renal toxicities and increased CVD risk.

- This nationwide cohort study used data from the Korean National Health Insurance database to investigate the risk for CVD associated with an increasing NSAID dosage in a real-world AS cohort.

- Investigators recruited 19,775 patients (mean age, 36.1 years; 75% men) with newly diagnosed AS and without any prior CVD between January 2010 and December 2018, among whom 99.7% received NSAID treatment and 30.2% received tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment.

- A time-varying approach was used to assess the NSAID exposure, wherein periods of NSAID use were defined as “NSAID-exposed” and periods longer than 1 month without NSAID use were defined as “NSAID-unexposed.”

- The primary outcome was the composite outcome of ischemic heart disease, stroke, or congestive heart failure.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up period of 98,290 person-years, 1663 cases of CVD were identified, which included 1157 cases of ischemic heart disease, 301 cases of stroke, and 613 cases of congestive heart failure.

- After adjusting for confounders, each defined daily dose increase in NSAIDs raised the risk for incident CVD by 10% (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.10; 95% CI, 1.08-1.13).

- Similarly, increasing the dose of NSAIDs was associated with an increased risk for ischemic heart disease (aHR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05-1.11), stroke (aHR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.04-1.15), and congestive heart failure (aHR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.08-1.16).

- The association between increasing NSAID dose and increased CVD risk was consistent across various subgroups, with NSAIDs posing a greater threat to cardiovascular health in women than in men.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “Taken together, these results suggest that increasing the dose of NSAIDs is associated with a higher cardiovascular risk in AS, but that the increased risk might be lower than that in the general population.”

SOURCE:

First author Ji-Won Kim, MD, PhD, of the Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, the Republic of Korea, and colleagues had their work published online on April 9 in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was of retrospective nature. The levels of acute phase reactants and AS disease activity could not be determined owing to a lack of data in the National Health Insurance database. The accuracy of the diagnosis of cardiovascular outcomes on the basis of the International Classification of Disease codes was also questionable.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Higher doses of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) increase the risk for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) compared with lower doses.

METHODOLOGY:

- NSAIDs can suppress inflammation and relieve pain in patients with AS, but long-term treatment with NSAIDs poses concerns regarding gastrointestinal and renal toxicities and increased CVD risk.

- This nationwide cohort study used data from the Korean National Health Insurance database to investigate the risk for CVD associated with an increasing NSAID dosage in a real-world AS cohort.

- Investigators recruited 19,775 patients (mean age, 36.1 years; 75% men) with newly diagnosed AS and without any prior CVD between January 2010 and December 2018, among whom 99.7% received NSAID treatment and 30.2% received tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment.

- A time-varying approach was used to assess the NSAID exposure, wherein periods of NSAID use were defined as “NSAID-exposed” and periods longer than 1 month without NSAID use were defined as “NSAID-unexposed.”

- The primary outcome was the composite outcome of ischemic heart disease, stroke, or congestive heart failure.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up period of 98,290 person-years, 1663 cases of CVD were identified, which included 1157 cases of ischemic heart disease, 301 cases of stroke, and 613 cases of congestive heart failure.

- After adjusting for confounders, each defined daily dose increase in NSAIDs raised the risk for incident CVD by 10% (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.10; 95% CI, 1.08-1.13).

- Similarly, increasing the dose of NSAIDs was associated with an increased risk for ischemic heart disease (aHR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05-1.11), stroke (aHR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.04-1.15), and congestive heart failure (aHR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.08-1.16).

- The association between increasing NSAID dose and increased CVD risk was consistent across various subgroups, with NSAIDs posing a greater threat to cardiovascular health in women than in men.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “Taken together, these results suggest that increasing the dose of NSAIDs is associated with a higher cardiovascular risk in AS, but that the increased risk might be lower than that in the general population.”

SOURCE:

First author Ji-Won Kim, MD, PhD, of the Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, the Republic of Korea, and colleagues had their work published online on April 9 in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was of retrospective nature. The levels of acute phase reactants and AS disease activity could not be determined owing to a lack of data in the National Health Insurance database. The accuracy of the diagnosis of cardiovascular outcomes on the basis of the International Classification of Disease codes was also questionable.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Higher doses of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) increase the risk for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) such as ischemic heart disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) compared with lower doses.

METHODOLOGY:

- NSAIDs can suppress inflammation and relieve pain in patients with AS, but long-term treatment with NSAIDs poses concerns regarding gastrointestinal and renal toxicities and increased CVD risk.

- This nationwide cohort study used data from the Korean National Health Insurance database to investigate the risk for CVD associated with an increasing NSAID dosage in a real-world AS cohort.

- Investigators recruited 19,775 patients (mean age, 36.1 years; 75% men) with newly diagnosed AS and without any prior CVD between January 2010 and December 2018, among whom 99.7% received NSAID treatment and 30.2% received tumor necrosis factor inhibitor treatment.

- A time-varying approach was used to assess the NSAID exposure, wherein periods of NSAID use were defined as “NSAID-exposed” and periods longer than 1 month without NSAID use were defined as “NSAID-unexposed.”

- The primary outcome was the composite outcome of ischemic heart disease, stroke, or congestive heart failure.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up period of 98,290 person-years, 1663 cases of CVD were identified, which included 1157 cases of ischemic heart disease, 301 cases of stroke, and 613 cases of congestive heart failure.

- After adjusting for confounders, each defined daily dose increase in NSAIDs raised the risk for incident CVD by 10% (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.10; 95% CI, 1.08-1.13).

- Similarly, increasing the dose of NSAIDs was associated with an increased risk for ischemic heart disease (aHR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.05-1.11), stroke (aHR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.04-1.15), and congestive heart failure (aHR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.08-1.16).

- The association between increasing NSAID dose and increased CVD risk was consistent across various subgroups, with NSAIDs posing a greater threat to cardiovascular health in women than in men.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “Taken together, these results suggest that increasing the dose of NSAIDs is associated with a higher cardiovascular risk in AS, but that the increased risk might be lower than that in the general population.”

SOURCE:

First author Ji-Won Kim, MD, PhD, of the Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Daegu Catholic University School of Medicine, Daegu, the Republic of Korea, and colleagues had their work published online on April 9 in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

The study was of retrospective nature. The levels of acute phase reactants and AS disease activity could not be determined owing to a lack of data in the National Health Insurance database. The accuracy of the diagnosis of cardiovascular outcomes on the basis of the International Classification of Disease codes was also questionable.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Self-Monitoring Better Than Usual Care Among Patients With Hypertension

TOPLINE:

Blood pressure (BP) self-monitoring and medication management may be better than usual care for controlling hypertension, a new study published in JAMA Network Open suggested.

METHODOLOGY:

- The secondary analysis of a randomized, unblinded clinical trial included patients aged ≥ 40 years with uncontrolled hypertension in Valencia, Spain, between 2017 and 2020.

- The 111 patients in the intervention group received educational materials and instructions for self-monitoring of BP with a home monitor and medication adjustment as needed without contacting their healthcare clinicians.

- The 108 patients in the control group received usual care, including education on BP control.

- After 24 months, researchers recorded BP levels, the number of people who achieved a target BP (systolic BP < 140 mm Hg and diastolic BP < 90 mm Hg), adverse events, quality of life, behavioral changes, and health service use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients in the intervention group had a lower average systolic BP reading at 24 months than patients who received usual care (adjusted mean difference, -3.4 mm Hg).

- Patients in the intervention group also had a lower average diastolic BP reading than usual care (adjusted mean difference, -2.5 mm Hg).