User login

Rising injectable drug use among whites may reverse declining HIV infection rates

Shifts in injectable drug use behaviors among white Americans could threaten years of declining U.S. HIV rates in persons who inject drugs, according to a federal report.

Between 2008 and 2014, the number of new HIV diagnoses in injectable drug users across all demographic groups declined nationally by nearly half, according to an analysis of national HIV surveillance survey data by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

African Americans who inject drugs had a 60% drop nationally in the number of HIV diagnoses between 2008 and 2014. Latinos/Hispanics who inject drugs had a 50% decline nationally in the number of HIV diagnoses between 2008 and 2014. Whites who inject drugs had a 27% decline in HIV rates between 2008 and 2014, but stable rates between 2012 and 2014.

The report was published online in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Of note is that 2014 marked the first time that rates of HIV diagnoses were higher in whites who inject drugs than in any other U.S. demographic, according to lead author Cyprian Wejnert, PhD, of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention at the CDC.

The overall drop in new HIV cases largely is due to safer drug use behaviors among blacks and Hispanics. Between 2005 and 2015, syringe sharing among blacks decreased by 34% – African Americans who inject drugs had a 48% increase between 2005 and 2015 in use of sterile drug equipment – and syringe sharing by Hispanics decreased by 12%. Among whites, however, needle sharing rates remained essentially unchanged at 43%, and the rate of receiving all syringes from sterile sources was also unchanged, at 22% across 22 cities. This steady rate, combined with the fact that more whites than ever are using heroin and other drugs intravenously, worries federal health officials (MMWR. 2016 Dec 2;65[47]:1336-42).

From 2005 to 2015, the total percentage of injectable drug users in 22 urban centers who were white rose from 38% to 54%, while the number of urban blacks using injectable drugs decreased from 38% to 19%. Among new injectable drug users, 40% were white, while the percentage of new users who were black decreased by more than half, according to the report. Rates of novel injectable drug use among urban Hispanics remained unchanged at 21%.

Although more than half of those who reported injecting drugs in 2015 said they had obtained sterile equipment from a syringe sharing program, one in three also reported that during that time they also continued to share needles and syringes, meaning that needle sharing rates are virtually unchanged from 2005.

Because sharing needles and syringes is a direct route of transmission for HIV, as well as the hepatitis B and C viruses, federal health officials are stressing the importance of syringe sharing programs. Injectable drug use is associated with about 1 in 10 new cases of HIV, and has also contributed to a 150% increase in acute cases of hepatitis C infections in the past decade, according to the CDC.

“Until now, the nation has made substantial progress in preventing HIV among people who inject drugs, but this success is threatened,” Jonathan Mermin, MD, MPH, director of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, said in a statement. He called for an expansion of current syringe sharing programs, especially in rural areas where access to sterile injection equipment is limited.

The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Shifts in injectable drug use behaviors among white Americans could threaten years of declining U.S. HIV rates in persons who inject drugs, according to a federal report.

Between 2008 and 2014, the number of new HIV diagnoses in injectable drug users across all demographic groups declined nationally by nearly half, according to an analysis of national HIV surveillance survey data by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

African Americans who inject drugs had a 60% drop nationally in the number of HIV diagnoses between 2008 and 2014. Latinos/Hispanics who inject drugs had a 50% decline nationally in the number of HIV diagnoses between 2008 and 2014. Whites who inject drugs had a 27% decline in HIV rates between 2008 and 2014, but stable rates between 2012 and 2014.

The report was published online in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Of note is that 2014 marked the first time that rates of HIV diagnoses were higher in whites who inject drugs than in any other U.S. demographic, according to lead author Cyprian Wejnert, PhD, of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention at the CDC.

The overall drop in new HIV cases largely is due to safer drug use behaviors among blacks and Hispanics. Between 2005 and 2015, syringe sharing among blacks decreased by 34% – African Americans who inject drugs had a 48% increase between 2005 and 2015 in use of sterile drug equipment – and syringe sharing by Hispanics decreased by 12%. Among whites, however, needle sharing rates remained essentially unchanged at 43%, and the rate of receiving all syringes from sterile sources was also unchanged, at 22% across 22 cities. This steady rate, combined with the fact that more whites than ever are using heroin and other drugs intravenously, worries federal health officials (MMWR. 2016 Dec 2;65[47]:1336-42).

From 2005 to 2015, the total percentage of injectable drug users in 22 urban centers who were white rose from 38% to 54%, while the number of urban blacks using injectable drugs decreased from 38% to 19%. Among new injectable drug users, 40% were white, while the percentage of new users who were black decreased by more than half, according to the report. Rates of novel injectable drug use among urban Hispanics remained unchanged at 21%.

Although more than half of those who reported injecting drugs in 2015 said they had obtained sterile equipment from a syringe sharing program, one in three also reported that during that time they also continued to share needles and syringes, meaning that needle sharing rates are virtually unchanged from 2005.

Because sharing needles and syringes is a direct route of transmission for HIV, as well as the hepatitis B and C viruses, federal health officials are stressing the importance of syringe sharing programs. Injectable drug use is associated with about 1 in 10 new cases of HIV, and has also contributed to a 150% increase in acute cases of hepatitis C infections in the past decade, according to the CDC.

“Until now, the nation has made substantial progress in preventing HIV among people who inject drugs, but this success is threatened,” Jonathan Mermin, MD, MPH, director of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, said in a statement. He called for an expansion of current syringe sharing programs, especially in rural areas where access to sterile injection equipment is limited.

The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Shifts in injectable drug use behaviors among white Americans could threaten years of declining U.S. HIV rates in persons who inject drugs, according to a federal report.

Between 2008 and 2014, the number of new HIV diagnoses in injectable drug users across all demographic groups declined nationally by nearly half, according to an analysis of national HIV surveillance survey data by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

African Americans who inject drugs had a 60% drop nationally in the number of HIV diagnoses between 2008 and 2014. Latinos/Hispanics who inject drugs had a 50% decline nationally in the number of HIV diagnoses between 2008 and 2014. Whites who inject drugs had a 27% decline in HIV rates between 2008 and 2014, but stable rates between 2012 and 2014.

The report was published online in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Of note is that 2014 marked the first time that rates of HIV diagnoses were higher in whites who inject drugs than in any other U.S. demographic, according to lead author Cyprian Wejnert, PhD, of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention at the CDC.

The overall drop in new HIV cases largely is due to safer drug use behaviors among blacks and Hispanics. Between 2005 and 2015, syringe sharing among blacks decreased by 34% – African Americans who inject drugs had a 48% increase between 2005 and 2015 in use of sterile drug equipment – and syringe sharing by Hispanics decreased by 12%. Among whites, however, needle sharing rates remained essentially unchanged at 43%, and the rate of receiving all syringes from sterile sources was also unchanged, at 22% across 22 cities. This steady rate, combined with the fact that more whites than ever are using heroin and other drugs intravenously, worries federal health officials (MMWR. 2016 Dec 2;65[47]:1336-42).

From 2005 to 2015, the total percentage of injectable drug users in 22 urban centers who were white rose from 38% to 54%, while the number of urban blacks using injectable drugs decreased from 38% to 19%. Among new injectable drug users, 40% were white, while the percentage of new users who were black decreased by more than half, according to the report. Rates of novel injectable drug use among urban Hispanics remained unchanged at 21%.

Although more than half of those who reported injecting drugs in 2015 said they had obtained sterile equipment from a syringe sharing program, one in three also reported that during that time they also continued to share needles and syringes, meaning that needle sharing rates are virtually unchanged from 2005.

Because sharing needles and syringes is a direct route of transmission for HIV, as well as the hepatitis B and C viruses, federal health officials are stressing the importance of syringe sharing programs. Injectable drug use is associated with about 1 in 10 new cases of HIV, and has also contributed to a 150% increase in acute cases of hepatitis C infections in the past decade, according to the CDC.

“Until now, the nation has made substantial progress in preventing HIV among people who inject drugs, but this success is threatened,” Jonathan Mermin, MD, MPH, director of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, said in a statement. He called for an expansion of current syringe sharing programs, especially in rural areas where access to sterile injection equipment is limited.

The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

FROM MMWR

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Diagnoses among urban white PWID decreased 28%, but the decline stopped in 2012. Whites have the highest rate of syringe sharing and now make up more than 50% of new PWID.

Data source: National HIV Surveillance System data from 2008-2014.

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Skin cancer a concern in pediatric solid organ transplant recipients

As survival rates among pediatric organ transplant recipients increase, so do the rates of cutaneous malignancies later in life for this population, who are at a greater risk for skin cancers that include nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), melanoma, Kaposi sarcoma, and anogenital carcinoma, according to the authors of a literature review.

In studies, skin cancers account for 13%-55% of all cancers in pediatric organ transplant recipients (POTRs), according to Alexander L. Fogel of Stanford (Calif.) University and his coauthors. The review article provides an update on this topic, as well as information on the prevention and management of skin cancers in this population, and the differences between this group and adult organ transplant recipients (AOTRs).

NMSC is the most common type of skin cancer in the pediatric group – and the second most common type of malignancy (NMSCs are the most common type of cancer affecting adult organ transplant recipients). NMSCs typically appear an average of 12-18 years post transplantation in this population (at an average age of 26-34 years). Length of posttransplantation follow-up, sunlight exposure, fair skin, and Northern European ancestry are among the factors associated with increased risk. This type of cancer involves the lip nearly twice as often as in adult recipients: 23% vs. 12%. The pediatric cohort also experiences more nonmelanoma cancer spreading to the lymph nodes than do adults: 9% vs. 6%.

Among pediatric transplant recipients, squamous cell carcinomas appear 2.8 times more often than basal cell carcinomas, “a trend that is opposite that observed in the nontransplant population,” the authors wrote.

In one study, anogenital carcinomas accounted for 4% of posttransplant cancers in this cohort, at an average of 12 years after the transplant, at a mean age of 27 years.

Some data indicate that in adult transplant recipients, there is an association between the human papillomavirus, and anal and genital warts and posttransplant anogenital cancer, but there are little data looking at this association in the pediatric group, the authors noted.

Although melanoma and Kaposi sarcoma are also found in this cohort at rates greater than in the general population, and are associated with high mortality rates, the data are too few to draw conclusions, the authors wrote.

In 2014, 1,795 pediatric solid organ transplants were performed, accounting for 6% of all such transplants. The absolute number of pediatric transplants has remained fairly stable over 5 years, yet very little pediatric-specific literature exists for prevention and management of skin cancers post transplantation, the authors pointed out.

Changing immunosuppressive medications used in transplantation may be effective in reducing skin cancer risk, they said, noting that including rapamycin inhibitors in combination therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of developing skin cancers in some transplant patients by more than half.

The authors emphasized that regular sunscreen use and dermatologic checkups are also essential in this population, and that “the importance of regular dermatologic evaluation should be stressed to patients and their families.”

Mr. Fogel’s coauthors were Mari Miyar, MD, of the department of dermatology, Kaiser Permanente, San Jose, Calif., and Joyce Teng, MD, of the departments of dermatology and pediatrics, Stanford. The authors had no disclosures listed, and no funding source for the review was listed.

This article was updated 12/8/16.

As survival rates among pediatric organ transplant recipients increase, so do the rates of cutaneous malignancies later in life for this population, who are at a greater risk for skin cancers that include nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), melanoma, Kaposi sarcoma, and anogenital carcinoma, according to the authors of a literature review.

In studies, skin cancers account for 13%-55% of all cancers in pediatric organ transplant recipients (POTRs), according to Alexander L. Fogel of Stanford (Calif.) University and his coauthors. The review article provides an update on this topic, as well as information on the prevention and management of skin cancers in this population, and the differences between this group and adult organ transplant recipients (AOTRs).

NMSC is the most common type of skin cancer in the pediatric group – and the second most common type of malignancy (NMSCs are the most common type of cancer affecting adult organ transplant recipients). NMSCs typically appear an average of 12-18 years post transplantation in this population (at an average age of 26-34 years). Length of posttransplantation follow-up, sunlight exposure, fair skin, and Northern European ancestry are among the factors associated with increased risk. This type of cancer involves the lip nearly twice as often as in adult recipients: 23% vs. 12%. The pediatric cohort also experiences more nonmelanoma cancer spreading to the lymph nodes than do adults: 9% vs. 6%.

Among pediatric transplant recipients, squamous cell carcinomas appear 2.8 times more often than basal cell carcinomas, “a trend that is opposite that observed in the nontransplant population,” the authors wrote.

In one study, anogenital carcinomas accounted for 4% of posttransplant cancers in this cohort, at an average of 12 years after the transplant, at a mean age of 27 years.

Some data indicate that in adult transplant recipients, there is an association between the human papillomavirus, and anal and genital warts and posttransplant anogenital cancer, but there are little data looking at this association in the pediatric group, the authors noted.

Although melanoma and Kaposi sarcoma are also found in this cohort at rates greater than in the general population, and are associated with high mortality rates, the data are too few to draw conclusions, the authors wrote.

In 2014, 1,795 pediatric solid organ transplants were performed, accounting for 6% of all such transplants. The absolute number of pediatric transplants has remained fairly stable over 5 years, yet very little pediatric-specific literature exists for prevention and management of skin cancers post transplantation, the authors pointed out.

Changing immunosuppressive medications used in transplantation may be effective in reducing skin cancer risk, they said, noting that including rapamycin inhibitors in combination therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of developing skin cancers in some transplant patients by more than half.

The authors emphasized that regular sunscreen use and dermatologic checkups are also essential in this population, and that “the importance of regular dermatologic evaluation should be stressed to patients and their families.”

Mr. Fogel’s coauthors were Mari Miyar, MD, of the department of dermatology, Kaiser Permanente, San Jose, Calif., and Joyce Teng, MD, of the departments of dermatology and pediatrics, Stanford. The authors had no disclosures listed, and no funding source for the review was listed.

This article was updated 12/8/16.

As survival rates among pediatric organ transplant recipients increase, so do the rates of cutaneous malignancies later in life for this population, who are at a greater risk for skin cancers that include nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs), melanoma, Kaposi sarcoma, and anogenital carcinoma, according to the authors of a literature review.

In studies, skin cancers account for 13%-55% of all cancers in pediatric organ transplant recipients (POTRs), according to Alexander L. Fogel of Stanford (Calif.) University and his coauthors. The review article provides an update on this topic, as well as information on the prevention and management of skin cancers in this population, and the differences between this group and adult organ transplant recipients (AOTRs).

NMSC is the most common type of skin cancer in the pediatric group – and the second most common type of malignancy (NMSCs are the most common type of cancer affecting adult organ transplant recipients). NMSCs typically appear an average of 12-18 years post transplantation in this population (at an average age of 26-34 years). Length of posttransplantation follow-up, sunlight exposure, fair skin, and Northern European ancestry are among the factors associated with increased risk. This type of cancer involves the lip nearly twice as often as in adult recipients: 23% vs. 12%. The pediatric cohort also experiences more nonmelanoma cancer spreading to the lymph nodes than do adults: 9% vs. 6%.

Among pediatric transplant recipients, squamous cell carcinomas appear 2.8 times more often than basal cell carcinomas, “a trend that is opposite that observed in the nontransplant population,” the authors wrote.

In one study, anogenital carcinomas accounted for 4% of posttransplant cancers in this cohort, at an average of 12 years after the transplant, at a mean age of 27 years.

Some data indicate that in adult transplant recipients, there is an association between the human papillomavirus, and anal and genital warts and posttransplant anogenital cancer, but there are little data looking at this association in the pediatric group, the authors noted.

Although melanoma and Kaposi sarcoma are also found in this cohort at rates greater than in the general population, and are associated with high mortality rates, the data are too few to draw conclusions, the authors wrote.

In 2014, 1,795 pediatric solid organ transplants were performed, accounting for 6% of all such transplants. The absolute number of pediatric transplants has remained fairly stable over 5 years, yet very little pediatric-specific literature exists for prevention and management of skin cancers post transplantation, the authors pointed out.

Changing immunosuppressive medications used in transplantation may be effective in reducing skin cancer risk, they said, noting that including rapamycin inhibitors in combination therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of developing skin cancers in some transplant patients by more than half.

The authors emphasized that regular sunscreen use and dermatologic checkups are also essential in this population, and that “the importance of regular dermatologic evaluation should be stressed to patients and their families.”

Mr. Fogel’s coauthors were Mari Miyar, MD, of the department of dermatology, Kaiser Permanente, San Jose, Calif., and Joyce Teng, MD, of the departments of dermatology and pediatrics, Stanford. The authors had no disclosures listed, and no funding source for the review was listed.

This article was updated 12/8/16.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Pediatric solid organ transplant recipients experience skin cancer rates between 13% and 55%.

Data source: A literature review of malignancies among pediatric organ transplant recipients.

Disclosures: The authors listed no disclosures, and no funding source for the review was listed.

FDA sunscreen guidance calls for maximal use trials

The Food and Drug Administration has released final industry guidance for nonclinical sunscreen manufacturers, but comments from a top agency official bring into question the pace of progress for getting the products to market.

A 2014 law, the Sunscreen Innovation Act, was intended to speed approval of new sunscreen active ingredients; one impetus for its passage was that no new sunscreen active ingredient has been approved since the late 1990s.

During that time, eight applications for new sunscreen active ingredients languished at the agency, even though many, such as UV filters bisoctrizole and bemotrizinol, are widely available across Europe and elsewhere. The law gave the FDA 1 year to review the backlog of applications for the ingredients and gave the agency 18 months to act on any sunscreen ingredient application submitted after the law went into effect.

“The FDA has issued proposed sunscreen orders identifying data we believe is necessary for the agency to make a positive [generally regarded as safe and effective] determination on those within the [law’s] required time frame, but has yet to receive the additional data we requested” from sunscreen ingredient manufacturers, Theresa M. Michele, MD, director of the FDA’s Division of Nonprescription Drug Products, wrote in a blog post.

To help, the agency has just released the final two of four industry guidance documents. The first addresses the agency’s current thinking on what constitutes a generally safe and effective sunscreen ingredient, while the second outlines data submission procedures. Previous guidance addressed procedural matters.

Specifically, the FDA wants to see evidence that these ingredients aren’t toxic over time, something that requires clinical trials in humans.

“The FDA and industry are essentially at a standstill because industry feels that there is a significant amount of resources they have to [invest] in order to comply with these testing regulations,” Dr. Lim said in an interview. “Industry is not willing to do it.”

In Europe and many other countries, sunscreens are considered cosmetics. The FDA considers them over-the-counter drugs and holds them to a higher approval standard. Although the 2014 law allows the FDA to review 5 years or more of marketing history for ingredients that are in use outside the United States, current approval standards require human absorption data derived from maximal usage trials to determine the risk of chronic exposure to products applied over large areas of the body, Dr. Michele said in a statement. “It is the same standard used by the FDA for all topically applied drugs, and especially for drugs that are used routinely over the course of one’s life.”

Dr. Lim said that the AAD is working as a neutral party to help both sides arrive at a compromise, and that a meeting between FDA and industry officials is scheduled for early 2017. However, he said that he thinks it is “not likely” that the FDA would ever relax its approval process to view sunscreens at the level of cosmetics as is done abroad, since that would mean different sets of standards for the same class of product. “Knowing how the FDA works, this is not going to happen,” Dr. Lim said.

“The FDA is committed to helping ensure that sunscreens are safe and effective for U.S. consumers, but we need data to move forward,” Dr. Michele wrote.

Dr. Lim disclosed that he is a consultant for Pierre Fabre and an investigator for Allergan, Estee Lauder, and Ferndale.

The Food and Drug Administration has released final industry guidance for nonclinical sunscreen manufacturers, but comments from a top agency official bring into question the pace of progress for getting the products to market.

A 2014 law, the Sunscreen Innovation Act, was intended to speed approval of new sunscreen active ingredients; one impetus for its passage was that no new sunscreen active ingredient has been approved since the late 1990s.

During that time, eight applications for new sunscreen active ingredients languished at the agency, even though many, such as UV filters bisoctrizole and bemotrizinol, are widely available across Europe and elsewhere. The law gave the FDA 1 year to review the backlog of applications for the ingredients and gave the agency 18 months to act on any sunscreen ingredient application submitted after the law went into effect.

“The FDA has issued proposed sunscreen orders identifying data we believe is necessary for the agency to make a positive [generally regarded as safe and effective] determination on those within the [law’s] required time frame, but has yet to receive the additional data we requested” from sunscreen ingredient manufacturers, Theresa M. Michele, MD, director of the FDA’s Division of Nonprescription Drug Products, wrote in a blog post.

To help, the agency has just released the final two of four industry guidance documents. The first addresses the agency’s current thinking on what constitutes a generally safe and effective sunscreen ingredient, while the second outlines data submission procedures. Previous guidance addressed procedural matters.

Specifically, the FDA wants to see evidence that these ingredients aren’t toxic over time, something that requires clinical trials in humans.

“The FDA and industry are essentially at a standstill because industry feels that there is a significant amount of resources they have to [invest] in order to comply with these testing regulations,” Dr. Lim said in an interview. “Industry is not willing to do it.”

In Europe and many other countries, sunscreens are considered cosmetics. The FDA considers them over-the-counter drugs and holds them to a higher approval standard. Although the 2014 law allows the FDA to review 5 years or more of marketing history for ingredients that are in use outside the United States, current approval standards require human absorption data derived from maximal usage trials to determine the risk of chronic exposure to products applied over large areas of the body, Dr. Michele said in a statement. “It is the same standard used by the FDA for all topically applied drugs, and especially for drugs that are used routinely over the course of one’s life.”

Dr. Lim said that the AAD is working as a neutral party to help both sides arrive at a compromise, and that a meeting between FDA and industry officials is scheduled for early 2017. However, he said that he thinks it is “not likely” that the FDA would ever relax its approval process to view sunscreens at the level of cosmetics as is done abroad, since that would mean different sets of standards for the same class of product. “Knowing how the FDA works, this is not going to happen,” Dr. Lim said.

“The FDA is committed to helping ensure that sunscreens are safe and effective for U.S. consumers, but we need data to move forward,” Dr. Michele wrote.

Dr. Lim disclosed that he is a consultant for Pierre Fabre and an investigator for Allergan, Estee Lauder, and Ferndale.

The Food and Drug Administration has released final industry guidance for nonclinical sunscreen manufacturers, but comments from a top agency official bring into question the pace of progress for getting the products to market.

A 2014 law, the Sunscreen Innovation Act, was intended to speed approval of new sunscreen active ingredients; one impetus for its passage was that no new sunscreen active ingredient has been approved since the late 1990s.

During that time, eight applications for new sunscreen active ingredients languished at the agency, even though many, such as UV filters bisoctrizole and bemotrizinol, are widely available across Europe and elsewhere. The law gave the FDA 1 year to review the backlog of applications for the ingredients and gave the agency 18 months to act on any sunscreen ingredient application submitted after the law went into effect.

“The FDA has issued proposed sunscreen orders identifying data we believe is necessary for the agency to make a positive [generally regarded as safe and effective] determination on those within the [law’s] required time frame, but has yet to receive the additional data we requested” from sunscreen ingredient manufacturers, Theresa M. Michele, MD, director of the FDA’s Division of Nonprescription Drug Products, wrote in a blog post.

To help, the agency has just released the final two of four industry guidance documents. The first addresses the agency’s current thinking on what constitutes a generally safe and effective sunscreen ingredient, while the second outlines data submission procedures. Previous guidance addressed procedural matters.

Specifically, the FDA wants to see evidence that these ingredients aren’t toxic over time, something that requires clinical trials in humans.

“The FDA and industry are essentially at a standstill because industry feels that there is a significant amount of resources they have to [invest] in order to comply with these testing regulations,” Dr. Lim said in an interview. “Industry is not willing to do it.”

In Europe and many other countries, sunscreens are considered cosmetics. The FDA considers them over-the-counter drugs and holds them to a higher approval standard. Although the 2014 law allows the FDA to review 5 years or more of marketing history for ingredients that are in use outside the United States, current approval standards require human absorption data derived from maximal usage trials to determine the risk of chronic exposure to products applied over large areas of the body, Dr. Michele said in a statement. “It is the same standard used by the FDA for all topically applied drugs, and especially for drugs that are used routinely over the course of one’s life.”

Dr. Lim said that the AAD is working as a neutral party to help both sides arrive at a compromise, and that a meeting between FDA and industry officials is scheduled for early 2017. However, he said that he thinks it is “not likely” that the FDA would ever relax its approval process to view sunscreens at the level of cosmetics as is done abroad, since that would mean different sets of standards for the same class of product. “Knowing how the FDA works, this is not going to happen,” Dr. Lim said.

“The FDA is committed to helping ensure that sunscreens are safe and effective for U.S. consumers, but we need data to move forward,” Dr. Michele wrote.

Dr. Lim disclosed that he is a consultant for Pierre Fabre and an investigator for Allergan, Estee Lauder, and Ferndale.

Early TIPS effective in high-risk cirrhosis patients, but still underutilized

BOSTON – High-risk cirrhosis patients treated early with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) showed increased survival rates and reduced rates of adverse events, according to a study.

The data were presented at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases by Virginia Hernandez-Gea, MD, a hepatologist at the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona.

In each study arm, three-quarters were men in their mid-50s. Cirrhosis in the non-TIPS group was alcohol-related in 57.4% of the cohort, compared with 71.2% of the group given early TIPS; roughly half of each group mentioned alcohol use in the past 3 months.

Also similar were Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores: an average of 15.5 in the non-TIPS group, compared with 15 on average in the TIPS group. Nearly three-quarters of the TIPS group had a Child-Pugh C score, compared with 64% in the non-TIPS group. A Child-Pugh score with active bleeding was recorded in 28.8% of the TIPS group, compared with 36% in the non-TIPS group.

The transplant-free survival rate at 1 year in the standard care group was 61%, compared with 76% in the early TIPS group (P = .0175). The failure and bleeding rate at 1 year was significantly higher in the standard care group: 91%, compared with 68% in the early TIPS group (P = .004). Failure and bleeding rates in the Child-Pugh B and C groups across the study were similar.

Ascites at 1 year was seen in 88% of the standard care group, compared with in 64% of the study group. Rates of hepatic encephalopathy were similar in those with Child-Pugh B with active bleeding, and Child-Pugh C across both groups: 22% in the standard care group vs. 25% in the early TIPS group.

That there was no associated significant risk of hepatic encephalopathy in persons with acute variceal bleeding who were given early TIPS “strongly suggests that early TIPS should be included in clinical practice,” Dr. Hernandez-Gea said, noting that only 10% of the 34 sites in the study had used early TIPS. “We don’t really know why centers are not using this, since it is very difficult to find treatments that extend survival rates in this population.”

BOSTON – High-risk cirrhosis patients treated early with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) showed increased survival rates and reduced rates of adverse events, according to a study.

The data were presented at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases by Virginia Hernandez-Gea, MD, a hepatologist at the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona.

In each study arm, three-quarters were men in their mid-50s. Cirrhosis in the non-TIPS group was alcohol-related in 57.4% of the cohort, compared with 71.2% of the group given early TIPS; roughly half of each group mentioned alcohol use in the past 3 months.

Also similar were Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores: an average of 15.5 in the non-TIPS group, compared with 15 on average in the TIPS group. Nearly three-quarters of the TIPS group had a Child-Pugh C score, compared with 64% in the non-TIPS group. A Child-Pugh score with active bleeding was recorded in 28.8% of the TIPS group, compared with 36% in the non-TIPS group.

The transplant-free survival rate at 1 year in the standard care group was 61%, compared with 76% in the early TIPS group (P = .0175). The failure and bleeding rate at 1 year was significantly higher in the standard care group: 91%, compared with 68% in the early TIPS group (P = .004). Failure and bleeding rates in the Child-Pugh B and C groups across the study were similar.

Ascites at 1 year was seen in 88% of the standard care group, compared with in 64% of the study group. Rates of hepatic encephalopathy were similar in those with Child-Pugh B with active bleeding, and Child-Pugh C across both groups: 22% in the standard care group vs. 25% in the early TIPS group.

That there was no associated significant risk of hepatic encephalopathy in persons with acute variceal bleeding who were given early TIPS “strongly suggests that early TIPS should be included in clinical practice,” Dr. Hernandez-Gea said, noting that only 10% of the 34 sites in the study had used early TIPS. “We don’t really know why centers are not using this, since it is very difficult to find treatments that extend survival rates in this population.”

BOSTON – High-risk cirrhosis patients treated early with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) showed increased survival rates and reduced rates of adverse events, according to a study.

The data were presented at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases by Virginia Hernandez-Gea, MD, a hepatologist at the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona.

In each study arm, three-quarters were men in their mid-50s. Cirrhosis in the non-TIPS group was alcohol-related in 57.4% of the cohort, compared with 71.2% of the group given early TIPS; roughly half of each group mentioned alcohol use in the past 3 months.

Also similar were Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores: an average of 15.5 in the non-TIPS group, compared with 15 on average in the TIPS group. Nearly three-quarters of the TIPS group had a Child-Pugh C score, compared with 64% in the non-TIPS group. A Child-Pugh score with active bleeding was recorded in 28.8% of the TIPS group, compared with 36% in the non-TIPS group.

The transplant-free survival rate at 1 year in the standard care group was 61%, compared with 76% in the early TIPS group (P = .0175). The failure and bleeding rate at 1 year was significantly higher in the standard care group: 91%, compared with 68% in the early TIPS group (P = .004). Failure and bleeding rates in the Child-Pugh B and C groups across the study were similar.

Ascites at 1 year was seen in 88% of the standard care group, compared with in 64% of the study group. Rates of hepatic encephalopathy were similar in those with Child-Pugh B with active bleeding, and Child-Pugh C across both groups: 22% in the standard care group vs. 25% in the early TIPS group.

That there was no associated significant risk of hepatic encephalopathy in persons with acute variceal bleeding who were given early TIPS “strongly suggests that early TIPS should be included in clinical practice,” Dr. Hernandez-Gea said, noting that only 10% of the 34 sites in the study had used early TIPS. “We don’t really know why centers are not using this, since it is very difficult to find treatments that extend survival rates in this population.”

AT THE LIVER MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 1 year post procedure, early TIPS was associated with better rates of survival and lower rates of adverse events, compared with those who did not receive early TIPS.

Data source: Multicenter, international observational study between 2011 and 2015 of 671 high-risk patients with cirrhosis managed according to current guidelines.

Disclosures: Dr. Hernandez-Gea did not have any relevant disclosures.

Time to consider cirrhosis medical homes

BOSTON – As part of the push to create value-based care across the specialties, hepatologists should consider medical homes for their patients, such as those with cirrhosis, according to experts.

“Cirrhosis is a chronic condition, highly symptomatic, and occurs in highly comorbid individuals. Treating them in a medical home scenario means we can offer services that we don’t otherwise do, but which are associated with better outcomes for our patients,” Fasiha Kanwal, MD, of the department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in a panel presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Essentially, value-based care is the evolution of evidence-based medicine, according to Zobair M. Younossi, MD, AGAF, FAASLD, chair of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital. With value-based care, aligned incentives across all the specialties will lead to more precise accounting and efficiencies of care, said Dr. Younossi, who was also on the panel. “It would be very difficult right now to ask a hospital to tell you exactly what the cost of their liver care would be,” he said.

However, at present there are no true value-based models for hepatology in the United States, according to Dr. Kanwal, so clinicians should start by defining what will “truly constitute value for our patients.”

Because psychosocial support is essential to improved outcomes in patients with cirrhosis, she suggested adding case managers in practice, as they can help coordinate with services in the community at large. Other suggestions she offered included extending office hours, operating an after-hours hotline, and building teams that include general internists, additional nursing staff, and nutritionists.

Even though such changes in clinical practice models now are inevitable, Dr. Kanwal said there are few data at present that support how to innovate care in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. This matters, as how patients present for outpatient follow-up care will impact reimbursements to the clinicians who treat them.

Some possible ways to improve hospital outcomes for patients with cirrhosis include creating a “best practice alert” that prompts a hepatology consult and triggers the implementation of a standardized set of guidelines for addressing ascites, bleeding, acute kidney injury, encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome. For those with decompensated cirrhosis or for those who need transplants, a similar standardized checklist can be systematized between the hospital and clinic, emphasizing inpatient rifaximin and prophylactic antibiotics in case of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

With an overt emphasis on the needs of patients and payers, clinicians now must compete with one another to offer the most comprehensive, cost-effective care supported by information technology structures that can assess real time costs and outcomes, said Dr. Younossi. “Hepatology is lagging behind other fields in all this,” he added.

This worries Dr. Kanwal: “We should be the ones to determine what the value should be. We should be the ones to decide what the model will be and to engage with other fields, and the payers. Otherwise we will not have a seat at the table.”

Dr. Kanwal and Dr. Younossi did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

BOSTON – As part of the push to create value-based care across the specialties, hepatologists should consider medical homes for their patients, such as those with cirrhosis, according to experts.

“Cirrhosis is a chronic condition, highly symptomatic, and occurs in highly comorbid individuals. Treating them in a medical home scenario means we can offer services that we don’t otherwise do, but which are associated with better outcomes for our patients,” Fasiha Kanwal, MD, of the department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in a panel presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Essentially, value-based care is the evolution of evidence-based medicine, according to Zobair M. Younossi, MD, AGAF, FAASLD, chair of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital. With value-based care, aligned incentives across all the specialties will lead to more precise accounting and efficiencies of care, said Dr. Younossi, who was also on the panel. “It would be very difficult right now to ask a hospital to tell you exactly what the cost of their liver care would be,” he said.

However, at present there are no true value-based models for hepatology in the United States, according to Dr. Kanwal, so clinicians should start by defining what will “truly constitute value for our patients.”

Because psychosocial support is essential to improved outcomes in patients with cirrhosis, she suggested adding case managers in practice, as they can help coordinate with services in the community at large. Other suggestions she offered included extending office hours, operating an after-hours hotline, and building teams that include general internists, additional nursing staff, and nutritionists.

Even though such changes in clinical practice models now are inevitable, Dr. Kanwal said there are few data at present that support how to innovate care in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. This matters, as how patients present for outpatient follow-up care will impact reimbursements to the clinicians who treat them.

Some possible ways to improve hospital outcomes for patients with cirrhosis include creating a “best practice alert” that prompts a hepatology consult and triggers the implementation of a standardized set of guidelines for addressing ascites, bleeding, acute kidney injury, encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome. For those with decompensated cirrhosis or for those who need transplants, a similar standardized checklist can be systematized between the hospital and clinic, emphasizing inpatient rifaximin and prophylactic antibiotics in case of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

With an overt emphasis on the needs of patients and payers, clinicians now must compete with one another to offer the most comprehensive, cost-effective care supported by information technology structures that can assess real time costs and outcomes, said Dr. Younossi. “Hepatology is lagging behind other fields in all this,” he added.

This worries Dr. Kanwal: “We should be the ones to determine what the value should be. We should be the ones to decide what the model will be and to engage with other fields, and the payers. Otherwise we will not have a seat at the table.”

Dr. Kanwal and Dr. Younossi did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

BOSTON – As part of the push to create value-based care across the specialties, hepatologists should consider medical homes for their patients, such as those with cirrhosis, according to experts.

“Cirrhosis is a chronic condition, highly symptomatic, and occurs in highly comorbid individuals. Treating them in a medical home scenario means we can offer services that we don’t otherwise do, but which are associated with better outcomes for our patients,” Fasiha Kanwal, MD, of the department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in a panel presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Essentially, value-based care is the evolution of evidence-based medicine, according to Zobair M. Younossi, MD, AGAF, FAASLD, chair of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital. With value-based care, aligned incentives across all the specialties will lead to more precise accounting and efficiencies of care, said Dr. Younossi, who was also on the panel. “It would be very difficult right now to ask a hospital to tell you exactly what the cost of their liver care would be,” he said.

However, at present there are no true value-based models for hepatology in the United States, according to Dr. Kanwal, so clinicians should start by defining what will “truly constitute value for our patients.”

Because psychosocial support is essential to improved outcomes in patients with cirrhosis, she suggested adding case managers in practice, as they can help coordinate with services in the community at large. Other suggestions she offered included extending office hours, operating an after-hours hotline, and building teams that include general internists, additional nursing staff, and nutritionists.

Even though such changes in clinical practice models now are inevitable, Dr. Kanwal said there are few data at present that support how to innovate care in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. This matters, as how patients present for outpatient follow-up care will impact reimbursements to the clinicians who treat them.

Some possible ways to improve hospital outcomes for patients with cirrhosis include creating a “best practice alert” that prompts a hepatology consult and triggers the implementation of a standardized set of guidelines for addressing ascites, bleeding, acute kidney injury, encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome. For those with decompensated cirrhosis or for those who need transplants, a similar standardized checklist can be systematized between the hospital and clinic, emphasizing inpatient rifaximin and prophylactic antibiotics in case of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

With an overt emphasis on the needs of patients and payers, clinicians now must compete with one another to offer the most comprehensive, cost-effective care supported by information technology structures that can assess real time costs and outcomes, said Dr. Younossi. “Hepatology is lagging behind other fields in all this,” he added.

This worries Dr. Kanwal: “We should be the ones to determine what the value should be. We should be the ones to decide what the model will be and to engage with other fields, and the payers. Otherwise we will not have a seat at the table.”

Dr. Kanwal and Dr. Younossi did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE LIVER MEETING 2016

Surgeon general’s addiction report calls for better integrated care

Primary and emergency care providers must step up prevention efforts and the use of state-of-the-art medicine when treating patients with addiction, according to the first-ever U.S. Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health.

In the report, “Facing Addiction in America,” Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy, MD, called on health care providers to increase access to care and approach addiction and substance use disorders as they would any other chronic health condition.

“We must help everyone see that addiction is not a character flaw – it is a chronic illness that we must approach with the same skill and compassion with which we approach heart disease, diabetes, and cancer,” Dr. Murthy explained.

In addition to offering an action plan to address substance use of all kinds, the surgeon general’s report updates the public on the state of the art of addiction science, and includes chapters on neurobiology, prevention, treatment, recovery, health systems integration, and recommendations for the future.

Data from 2015 show that more than 27 million people in the United States used illicit drugs or misuse prescription medications, while a quarter of the entire adult and adolescent population reported binge drinking in the past month. However, only 10% of those with a substance use disorder received relevant specialty care.

For the more than 40% of those with substance use disorders who have a comorbid mental health condition, less than half were treated for either, according to the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

That treatment gap is the direct result of lack of access to affordable care, shame, discrimination, and the lack of screening for substance misuse and substance use disorders in the primary care setting, Dr. Murthy wrote.

To address the gap, the surgeon general laid out a plan that starts with increasing community-wide substance use prevention efforts, such as enforcement of underage drinking laws and DUI laws, and offering needle exchange programs.

Dr. Murthy also called for a coordinated public health response to addiction, including an overhaul of criminal justice where substance use is concerned, and an emphasis on preventing known risk factors for substance misuse.

The report underscores the need for a better trained and integrated health care workforce equipped to treat addiction as a chronic disease in the general health care setting, enforcement of addiction and mental health parity laws, and the delivery of services based on the latest research into the psychosocial and biological underpinnings of substance use.

Surgeon General Murthy also used the report to urge professional medical associations to advocate for more access to medication-assisted treatment and prescription drug monitoring programs, and to create evidence-based guidelines for integrating substance use disorder treatment.

The American Medical Association responded positively to the report. In a statement, AMA President Andrew W. Gurman, MD, called it a “crucial starting point” and praised its “important guidance for the nation to see that addiction is a chronic disease and must be treated as such.”

While also supporting the report, others in the addiction medicine field pointed out that such starting points had come and gone before.

“As a profession, we saw what was happening 10 years ago, but there was no strong [push] to respond, for a variety of factors,” Ako Jacintho, MD, director of addiction medicine for HealthRIGHT 360, a California community health network, said in an interview.

“The professional medical societies such as the AMA and the American Academy of Family Physicians should have put more pressure on the American Board of Medical Specialties a decade ago to create an addiction medicine subspecialty,” Dr. Jacintho observed.

Access to addiction specialty care would be wider by now had the ABMS not continued to allow psychiatrists to maintain their hold on the specialty, according to Dr. Jacintho, a family physician who treats patients with addictions.

Earlier this year, the ABMS announced it will certify the subspecialty of addiction medicine through the American Board of Preventive Medicine. A date for the first examination is pending.

With the surgeon general’s imprimatur, Dr. Jacintho expects physicians will be more aware that they should at least screen for substance use. He also predicted the report will lead to more patients demanding that addiction treatment services be made available in the primary care setting – and that practitioners will respond, either by subspecializing in addiction, or by otherwise integrating it into their practices.

That should be easier to do with the recently passed Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016, which expands access to medication-assisted treatment for addiction, Dr. Jacintho said.

Dr. Murthy also urged pharmaceutical companies to continue developing abuse-deterrent formulations of opioids, and to prioritize development of nonopioid alternatives for pain relief.

But the surgeon general’s report does not go far enough, given that five times more Americans suffer from chronic pain than have an opioid use disorder, according to William Maixner, DDS, PhD, professor of anesthesiology and director of Duke University’s Center for Translational Pain Medicine, Durham, N.C.

“There is an interrelationship between this very overt substance abuse epidemic and the subtler and larger covert epidemic of chronic pain,” Dr. Maixner said in a statement. “What it has in common with a huge portion of the substance abuse epidemic is opioids.”

Dr. Maixner said he hoped the report would put greater emphasis on developing alternatives to opioids for pain management, “which would eliminate this key pathway to abuse.

“We have a fundamental problem when we are trying to manage pain for the 100 million people who have some form of chronic pain, and opioids are among the few therapies available that work,” he noted.

The surgeon general’s report also urges researchers to become activists to ensure their findings are not “misrepresented” in public policy debates.

“It’s time to change how we view addiction,” said Dr. Murthy. “Not as a moral failing, but as a chronic illness that must be treated with skill, urgency, and compassion. The way we address this crisis is a test for America.”

Primary and emergency care providers must step up prevention efforts and the use of state-of-the-art medicine when treating patients with addiction, according to the first-ever U.S. Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health.

In the report, “Facing Addiction in America,” Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy, MD, called on health care providers to increase access to care and approach addiction and substance use disorders as they would any other chronic health condition.

“We must help everyone see that addiction is not a character flaw – it is a chronic illness that we must approach with the same skill and compassion with which we approach heart disease, diabetes, and cancer,” Dr. Murthy explained.

In addition to offering an action plan to address substance use of all kinds, the surgeon general’s report updates the public on the state of the art of addiction science, and includes chapters on neurobiology, prevention, treatment, recovery, health systems integration, and recommendations for the future.

Data from 2015 show that more than 27 million people in the United States used illicit drugs or misuse prescription medications, while a quarter of the entire adult and adolescent population reported binge drinking in the past month. However, only 10% of those with a substance use disorder received relevant specialty care.

For the more than 40% of those with substance use disorders who have a comorbid mental health condition, less than half were treated for either, according to the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

That treatment gap is the direct result of lack of access to affordable care, shame, discrimination, and the lack of screening for substance misuse and substance use disorders in the primary care setting, Dr. Murthy wrote.

To address the gap, the surgeon general laid out a plan that starts with increasing community-wide substance use prevention efforts, such as enforcement of underage drinking laws and DUI laws, and offering needle exchange programs.

Dr. Murthy also called for a coordinated public health response to addiction, including an overhaul of criminal justice where substance use is concerned, and an emphasis on preventing known risk factors for substance misuse.

The report underscores the need for a better trained and integrated health care workforce equipped to treat addiction as a chronic disease in the general health care setting, enforcement of addiction and mental health parity laws, and the delivery of services based on the latest research into the psychosocial and biological underpinnings of substance use.

Surgeon General Murthy also used the report to urge professional medical associations to advocate for more access to medication-assisted treatment and prescription drug monitoring programs, and to create evidence-based guidelines for integrating substance use disorder treatment.

The American Medical Association responded positively to the report. In a statement, AMA President Andrew W. Gurman, MD, called it a “crucial starting point” and praised its “important guidance for the nation to see that addiction is a chronic disease and must be treated as such.”

While also supporting the report, others in the addiction medicine field pointed out that such starting points had come and gone before.

“As a profession, we saw what was happening 10 years ago, but there was no strong [push] to respond, for a variety of factors,” Ako Jacintho, MD, director of addiction medicine for HealthRIGHT 360, a California community health network, said in an interview.

“The professional medical societies such as the AMA and the American Academy of Family Physicians should have put more pressure on the American Board of Medical Specialties a decade ago to create an addiction medicine subspecialty,” Dr. Jacintho observed.

Access to addiction specialty care would be wider by now had the ABMS not continued to allow psychiatrists to maintain their hold on the specialty, according to Dr. Jacintho, a family physician who treats patients with addictions.

Earlier this year, the ABMS announced it will certify the subspecialty of addiction medicine through the American Board of Preventive Medicine. A date for the first examination is pending.

With the surgeon general’s imprimatur, Dr. Jacintho expects physicians will be more aware that they should at least screen for substance use. He also predicted the report will lead to more patients demanding that addiction treatment services be made available in the primary care setting – and that practitioners will respond, either by subspecializing in addiction, or by otherwise integrating it into their practices.

That should be easier to do with the recently passed Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016, which expands access to medication-assisted treatment for addiction, Dr. Jacintho said.

Dr. Murthy also urged pharmaceutical companies to continue developing abuse-deterrent formulations of opioids, and to prioritize development of nonopioid alternatives for pain relief.

But the surgeon general’s report does not go far enough, given that five times more Americans suffer from chronic pain than have an opioid use disorder, according to William Maixner, DDS, PhD, professor of anesthesiology and director of Duke University’s Center for Translational Pain Medicine, Durham, N.C.

“There is an interrelationship between this very overt substance abuse epidemic and the subtler and larger covert epidemic of chronic pain,” Dr. Maixner said in a statement. “What it has in common with a huge portion of the substance abuse epidemic is opioids.”

Dr. Maixner said he hoped the report would put greater emphasis on developing alternatives to opioids for pain management, “which would eliminate this key pathway to abuse.

“We have a fundamental problem when we are trying to manage pain for the 100 million people who have some form of chronic pain, and opioids are among the few therapies available that work,” he noted.

The surgeon general’s report also urges researchers to become activists to ensure their findings are not “misrepresented” in public policy debates.

“It’s time to change how we view addiction,” said Dr. Murthy. “Not as a moral failing, but as a chronic illness that must be treated with skill, urgency, and compassion. The way we address this crisis is a test for America.”

Primary and emergency care providers must step up prevention efforts and the use of state-of-the-art medicine when treating patients with addiction, according to the first-ever U.S. Surgeon General’s report on alcohol, drugs, and health.

In the report, “Facing Addiction in America,” Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy, MD, called on health care providers to increase access to care and approach addiction and substance use disorders as they would any other chronic health condition.

“We must help everyone see that addiction is not a character flaw – it is a chronic illness that we must approach with the same skill and compassion with which we approach heart disease, diabetes, and cancer,” Dr. Murthy explained.

In addition to offering an action plan to address substance use of all kinds, the surgeon general’s report updates the public on the state of the art of addiction science, and includes chapters on neurobiology, prevention, treatment, recovery, health systems integration, and recommendations for the future.

Data from 2015 show that more than 27 million people in the United States used illicit drugs or misuse prescription medications, while a quarter of the entire adult and adolescent population reported binge drinking in the past month. However, only 10% of those with a substance use disorder received relevant specialty care.

For the more than 40% of those with substance use disorders who have a comorbid mental health condition, less than half were treated for either, according to the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

That treatment gap is the direct result of lack of access to affordable care, shame, discrimination, and the lack of screening for substance misuse and substance use disorders in the primary care setting, Dr. Murthy wrote.

To address the gap, the surgeon general laid out a plan that starts with increasing community-wide substance use prevention efforts, such as enforcement of underage drinking laws and DUI laws, and offering needle exchange programs.

Dr. Murthy also called for a coordinated public health response to addiction, including an overhaul of criminal justice where substance use is concerned, and an emphasis on preventing known risk factors for substance misuse.

The report underscores the need for a better trained and integrated health care workforce equipped to treat addiction as a chronic disease in the general health care setting, enforcement of addiction and mental health parity laws, and the delivery of services based on the latest research into the psychosocial and biological underpinnings of substance use.

Surgeon General Murthy also used the report to urge professional medical associations to advocate for more access to medication-assisted treatment and prescription drug monitoring programs, and to create evidence-based guidelines for integrating substance use disorder treatment.

The American Medical Association responded positively to the report. In a statement, AMA President Andrew W. Gurman, MD, called it a “crucial starting point” and praised its “important guidance for the nation to see that addiction is a chronic disease and must be treated as such.”

While also supporting the report, others in the addiction medicine field pointed out that such starting points had come and gone before.

“As a profession, we saw what was happening 10 years ago, but there was no strong [push] to respond, for a variety of factors,” Ako Jacintho, MD, director of addiction medicine for HealthRIGHT 360, a California community health network, said in an interview.

“The professional medical societies such as the AMA and the American Academy of Family Physicians should have put more pressure on the American Board of Medical Specialties a decade ago to create an addiction medicine subspecialty,” Dr. Jacintho observed.

Access to addiction specialty care would be wider by now had the ABMS not continued to allow psychiatrists to maintain their hold on the specialty, according to Dr. Jacintho, a family physician who treats patients with addictions.

Earlier this year, the ABMS announced it will certify the subspecialty of addiction medicine through the American Board of Preventive Medicine. A date for the first examination is pending.

With the surgeon general’s imprimatur, Dr. Jacintho expects physicians will be more aware that they should at least screen for substance use. He also predicted the report will lead to more patients demanding that addiction treatment services be made available in the primary care setting – and that practitioners will respond, either by subspecializing in addiction, or by otherwise integrating it into their practices.

That should be easier to do with the recently passed Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016, which expands access to medication-assisted treatment for addiction, Dr. Jacintho said.

Dr. Murthy also urged pharmaceutical companies to continue developing abuse-deterrent formulations of opioids, and to prioritize development of nonopioid alternatives for pain relief.

But the surgeon general’s report does not go far enough, given that five times more Americans suffer from chronic pain than have an opioid use disorder, according to William Maixner, DDS, PhD, professor of anesthesiology and director of Duke University’s Center for Translational Pain Medicine, Durham, N.C.

“There is an interrelationship between this very overt substance abuse epidemic and the subtler and larger covert epidemic of chronic pain,” Dr. Maixner said in a statement. “What it has in common with a huge portion of the substance abuse epidemic is opioids.”

Dr. Maixner said he hoped the report would put greater emphasis on developing alternatives to opioids for pain management, “which would eliminate this key pathway to abuse.

“We have a fundamental problem when we are trying to manage pain for the 100 million people who have some form of chronic pain, and opioids are among the few therapies available that work,” he noted.

The surgeon general’s report also urges researchers to become activists to ensure their findings are not “misrepresented” in public policy debates.

“It’s time to change how we view addiction,” said Dr. Murthy. “Not as a moral failing, but as a chronic illness that must be treated with skill, urgency, and compassion. The way we address this crisis is a test for America.”

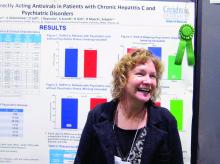

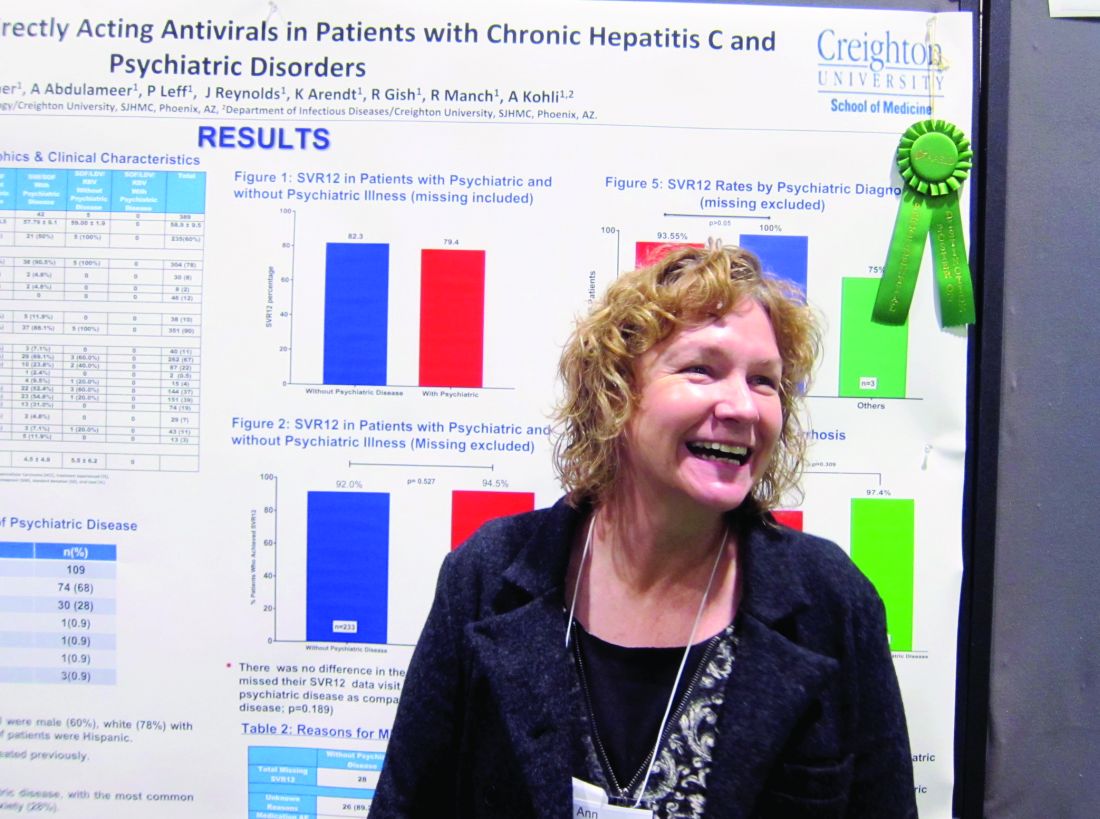

Direct-acting antiretrovirals in genotype 1 HCV patients with mental health conditions safe, well tolerated

BOSTON – Direct-acting antiretroviral therapies are safe and well tolerated in hepatitis C virus patients with comorbid psychiatric conditions, a study showed.

The finding that sustained virologic response (SVR) rates at 1 year were similar in genotype 1 HCV patients with and without psychiatric comorbidities could help end the stigma against treating this patient subgroup, stemming from when treatment with interferon risked psychiatric decompensation. That’s according to nurse practitioner Anne Moore, winner of this year’s Poster of Distinction Award at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases annual meeting.

She and her colleagues reviewed patient records for 588 adults diagnosed with genotype 1 HCV in Arizona between 2013 and 2016. They found 389 patients who’d been treated with either a combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir (with or without ribavirin) or sofosbuvir and simeprevir. Patients coinfected with HIV were included in this group; those who’d had a liver transplant were not. Just over three-quarters of the patients were white, 60% were male, 10% were Hispanic, and the average age was 59 years. A third of the patients had been diagnosed with cirrhosis.

Because medical and mental health records typically are not integrated, Ms. Moore and her colleagues instead used medical records to evaluate which medications had been prescribed, in order to determine likely psychiatric diagnoses. They determined that 27% of the 389 patients had a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis. Of these, 68% had depression and 28% had anxiety. Only one person was considered to have bipolar disorder; Ms. Moore said it was possible this group was underrepresented in the study, but that some persons considered to have depression might have had bipolar disorder instead.

Rates of SVR at 1 year were similar across the study – 82.3% in those without a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis vs. 79.4% of those who did have one – with no additional risk of patients with psychiatric diagnoses being lost to follow-up. DAA therapy was well tolerated in both groups.

Ms. Moore said that winning the award was a “huge surprise” but interpreted it to mean that liver specialists are struggling to find the best treatment algorithms for HCV, partly because of the number of restrictions often placed by payers on access to DAAs, but also because it is often difficult to know who will adhere to treatment.

“Gastroenterologists and hepatologists are not used to dealing with patients who have psychiatric conditions. They don’t understand them well, and so there is a reluctance to ‘go there.’ If that’s what has been holding you back, it doesn’t have to. You can treat these patients successfully,” Ms. Moore said.

She had no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Direct-acting antiretroviral therapies are safe and well tolerated in hepatitis C virus patients with comorbid psychiatric conditions, a study showed.

The finding that sustained virologic response (SVR) rates at 1 year were similar in genotype 1 HCV patients with and without psychiatric comorbidities could help end the stigma against treating this patient subgroup, stemming from when treatment with interferon risked psychiatric decompensation. That’s according to nurse practitioner Anne Moore, winner of this year’s Poster of Distinction Award at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases annual meeting.

She and her colleagues reviewed patient records for 588 adults diagnosed with genotype 1 HCV in Arizona between 2013 and 2016. They found 389 patients who’d been treated with either a combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir (with or without ribavirin) or sofosbuvir and simeprevir. Patients coinfected with HIV were included in this group; those who’d had a liver transplant were not. Just over three-quarters of the patients were white, 60% were male, 10% were Hispanic, and the average age was 59 years. A third of the patients had been diagnosed with cirrhosis.

Because medical and mental health records typically are not integrated, Ms. Moore and her colleagues instead used medical records to evaluate which medications had been prescribed, in order to determine likely psychiatric diagnoses. They determined that 27% of the 389 patients had a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis. Of these, 68% had depression and 28% had anxiety. Only one person was considered to have bipolar disorder; Ms. Moore said it was possible this group was underrepresented in the study, but that some persons considered to have depression might have had bipolar disorder instead.

Rates of SVR at 1 year were similar across the study – 82.3% in those without a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis vs. 79.4% of those who did have one – with no additional risk of patients with psychiatric diagnoses being lost to follow-up. DAA therapy was well tolerated in both groups.

Ms. Moore said that winning the award was a “huge surprise” but interpreted it to mean that liver specialists are struggling to find the best treatment algorithms for HCV, partly because of the number of restrictions often placed by payers on access to DAAs, but also because it is often difficult to know who will adhere to treatment.

“Gastroenterologists and hepatologists are not used to dealing with patients who have psychiatric conditions. They don’t understand them well, and so there is a reluctance to ‘go there.’ If that’s what has been holding you back, it doesn’t have to. You can treat these patients successfully,” Ms. Moore said.

She had no relevant financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Direct-acting antiretroviral therapies are safe and well tolerated in hepatitis C virus patients with comorbid psychiatric conditions, a study showed.

The finding that sustained virologic response (SVR) rates at 1 year were similar in genotype 1 HCV patients with and without psychiatric comorbidities could help end the stigma against treating this patient subgroup, stemming from when treatment with interferon risked psychiatric decompensation. That’s according to nurse practitioner Anne Moore, winner of this year’s Poster of Distinction Award at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases annual meeting.

She and her colleagues reviewed patient records for 588 adults diagnosed with genotype 1 HCV in Arizona between 2013 and 2016. They found 389 patients who’d been treated with either a combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir (with or without ribavirin) or sofosbuvir and simeprevir. Patients coinfected with HIV were included in this group; those who’d had a liver transplant were not. Just over three-quarters of the patients were white, 60% were male, 10% were Hispanic, and the average age was 59 years. A third of the patients had been diagnosed with cirrhosis.

Because medical and mental health records typically are not integrated, Ms. Moore and her colleagues instead used medical records to evaluate which medications had been prescribed, in order to determine likely psychiatric diagnoses. They determined that 27% of the 389 patients had a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis. Of these, 68% had depression and 28% had anxiety. Only one person was considered to have bipolar disorder; Ms. Moore said it was possible this group was underrepresented in the study, but that some persons considered to have depression might have had bipolar disorder instead.

Rates of SVR at 1 year were similar across the study – 82.3% in those without a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis vs. 79.4% of those who did have one – with no additional risk of patients with psychiatric diagnoses being lost to follow-up. DAA therapy was well tolerated in both groups.

Ms. Moore said that winning the award was a “huge surprise” but interpreted it to mean that liver specialists are struggling to find the best treatment algorithms for HCV, partly because of the number of restrictions often placed by payers on access to DAAs, but also because it is often difficult to know who will adhere to treatment.

“Gastroenterologists and hepatologists are not used to dealing with patients who have psychiatric conditions. They don’t understand them well, and so there is a reluctance to ‘go there.’ If that’s what has been holding you back, it doesn’t have to. You can treat these patients successfully,” Ms. Moore said.

She had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Sustained virologic response rates at 1 year were similar between genotype 1 HCV patients with and without a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of medical records from 2013 to 2016 for 588 adults with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus.

Disclosures: Ms. Moore had no relevant financial disclosures.

Treatment withdrawal without prior liver biopsy found safe in well-controlled autoimmune hepatitis

BOSTON – Although current guidance calls for a liver biopsy prior to treatment withdrawal in autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), a retrospective observational analysis conducted by researchers from the Cleveland Clinic offers a different view.

“Maybe not everyone needs a liver biopsy before withdrawing treatment,” Yilien Alonso, MD, an internist at the Cleveland Clinic in Weston, Fla., said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.