User login

Topical tofacitinib shows promise in atopic dermatitis

Topical tofacitinib showed significant improvements across all endpoints and for pruritus at week 4, compared with vehicle, results of a phase IIa trial have shown.

Tofacitinib is a Janus kinase inhibitor that affects the interleukin (IL)–4, IL-5, and IL-31 signaling pathways, interfering with the immune response that leads to inflammation.

The study could mean “that inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway may be a new therapeutic target for AD,” wrote the study’s lead author, Robert Bissonnette, MD, president of Innovaderm Research in Montreal. The study was published in the British Journal of Dermatology (2016 Nov;175[5]:902-11).

In the multicenter, double-blind, controlled study of 69 adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis randomly assigned to either 2% tofacitinib or vehicle ointment twice daily, the study group achieved an 81.7% mean reduction in baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score, compared with 29.9% of controls over the 4-week study period (P less than .001). EASI scores in the study group were about 80% at a score of 50, 60% at a score of 75, and 40% at a score of 90.

By week 4, about three-quarters of the study group were either clear or almost clear of their skin condition, according to the physician global assessment scale, compared with 22% of controls (P less than .05).

There also was a rapid reduction in patient-reported pruritus in the tofacitinib group per the Itch Severity Item scale, compared with controls, at weeks 2 and 4 (P less than .001 for each time point).

Tolerability was similar across the study, and treatment-related adverse effects were mild, although 44% of the tofacitinib group did report experiencing some form of infection, infestation, or other complication. Two people in the study group dropped out because of the severity of their treatment-emergent adverse events. There were no reported severe or serious infections.

Dr. Bissonnette has numerous pharmaceutical industry relationships, including with Pfizer, the study’s sponsor.

With the discovery of how cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 drive inflammatory disease pathogenesis, more targeted therapies are possible for dermatologic conditions such as atopic dermatitis.

The promise of such pathogenesis-based treatments gives hope to patients with atopic dermatitis, for whom new treatments have not been brought to market in more than 15 years.

While this is reason for excitement, the emergence of several new promising therapies calls for comparison trials, according to Brett A. King, MD, and William Damsky, MD, PhD, both of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“Further studies will be needed to address long-term efficacy and safety,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky noted. The results of Dr. Bissonnette’s phase IIa trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib mean there is potentially a third targeted topical agent to emerge as a treatment for atopic dermatitis. The others include the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole, and dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4 and IL-13.

“Head-to-head trials involving these agents and superpotent topical steroids would be useful in establishing their place in AD treatment algorithms,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky said.

Dr. King is an assistant professor of dermatology at Yale University. His coauthor, Dr. Damsky, is a second-year resident in dermatology at Yale University. These remarks are taken from an editorial accompanying Dr. Bissonnette’s study (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Nov;175[5]:861-2). Dr. King disclosed he has industry ties with Eli Lilly and Pfizer, among others. Dr. Damsky had no relevant disclosures.

With the discovery of how cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 drive inflammatory disease pathogenesis, more targeted therapies are possible for dermatologic conditions such as atopic dermatitis.

The promise of such pathogenesis-based treatments gives hope to patients with atopic dermatitis, for whom new treatments have not been brought to market in more than 15 years.

While this is reason for excitement, the emergence of several new promising therapies calls for comparison trials, according to Brett A. King, MD, and William Damsky, MD, PhD, both of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“Further studies will be needed to address long-term efficacy and safety,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky noted. The results of Dr. Bissonnette’s phase IIa trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib mean there is potentially a third targeted topical agent to emerge as a treatment for atopic dermatitis. The others include the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole, and dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4 and IL-13.

“Head-to-head trials involving these agents and superpotent topical steroids would be useful in establishing their place in AD treatment algorithms,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky said.

Dr. King is an assistant professor of dermatology at Yale University. His coauthor, Dr. Damsky, is a second-year resident in dermatology at Yale University. These remarks are taken from an editorial accompanying Dr. Bissonnette’s study (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Nov;175[5]:861-2). Dr. King disclosed he has industry ties with Eli Lilly and Pfizer, among others. Dr. Damsky had no relevant disclosures.

With the discovery of how cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 drive inflammatory disease pathogenesis, more targeted therapies are possible for dermatologic conditions such as atopic dermatitis.

The promise of such pathogenesis-based treatments gives hope to patients with atopic dermatitis, for whom new treatments have not been brought to market in more than 15 years.

While this is reason for excitement, the emergence of several new promising therapies calls for comparison trials, according to Brett A. King, MD, and William Damsky, MD, PhD, both of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“Further studies will be needed to address long-term efficacy and safety,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky noted. The results of Dr. Bissonnette’s phase IIa trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib mean there is potentially a third targeted topical agent to emerge as a treatment for atopic dermatitis. The others include the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole, and dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4 and IL-13.

“Head-to-head trials involving these agents and superpotent topical steroids would be useful in establishing their place in AD treatment algorithms,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky said.

Dr. King is an assistant professor of dermatology at Yale University. His coauthor, Dr. Damsky, is a second-year resident in dermatology at Yale University. These remarks are taken from an editorial accompanying Dr. Bissonnette’s study (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Nov;175[5]:861-2). Dr. King disclosed he has industry ties with Eli Lilly and Pfizer, among others. Dr. Damsky had no relevant disclosures.

Topical tofacitinib showed significant improvements across all endpoints and for pruritus at week 4, compared with vehicle, results of a phase IIa trial have shown.

Tofacitinib is a Janus kinase inhibitor that affects the interleukin (IL)–4, IL-5, and IL-31 signaling pathways, interfering with the immune response that leads to inflammation.

The study could mean “that inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway may be a new therapeutic target for AD,” wrote the study’s lead author, Robert Bissonnette, MD, president of Innovaderm Research in Montreal. The study was published in the British Journal of Dermatology (2016 Nov;175[5]:902-11).

In the multicenter, double-blind, controlled study of 69 adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis randomly assigned to either 2% tofacitinib or vehicle ointment twice daily, the study group achieved an 81.7% mean reduction in baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score, compared with 29.9% of controls over the 4-week study period (P less than .001). EASI scores in the study group were about 80% at a score of 50, 60% at a score of 75, and 40% at a score of 90.

By week 4, about three-quarters of the study group were either clear or almost clear of their skin condition, according to the physician global assessment scale, compared with 22% of controls (P less than .05).

There also was a rapid reduction in patient-reported pruritus in the tofacitinib group per the Itch Severity Item scale, compared with controls, at weeks 2 and 4 (P less than .001 for each time point).

Tolerability was similar across the study, and treatment-related adverse effects were mild, although 44% of the tofacitinib group did report experiencing some form of infection, infestation, or other complication. Two people in the study group dropped out because of the severity of their treatment-emergent adverse events. There were no reported severe or serious infections.

Dr. Bissonnette has numerous pharmaceutical industry relationships, including with Pfizer, the study’s sponsor.

Topical tofacitinib showed significant improvements across all endpoints and for pruritus at week 4, compared with vehicle, results of a phase IIa trial have shown.

Tofacitinib is a Janus kinase inhibitor that affects the interleukin (IL)–4, IL-5, and IL-31 signaling pathways, interfering with the immune response that leads to inflammation.

The study could mean “that inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway may be a new therapeutic target for AD,” wrote the study’s lead author, Robert Bissonnette, MD, president of Innovaderm Research in Montreal. The study was published in the British Journal of Dermatology (2016 Nov;175[5]:902-11).

In the multicenter, double-blind, controlled study of 69 adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis randomly assigned to either 2% tofacitinib or vehicle ointment twice daily, the study group achieved an 81.7% mean reduction in baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score, compared with 29.9% of controls over the 4-week study period (P less than .001). EASI scores in the study group were about 80% at a score of 50, 60% at a score of 75, and 40% at a score of 90.

By week 4, about three-quarters of the study group were either clear or almost clear of their skin condition, according to the physician global assessment scale, compared with 22% of controls (P less than .05).

There also was a rapid reduction in patient-reported pruritus in the tofacitinib group per the Itch Severity Item scale, compared with controls, at weeks 2 and 4 (P less than .001 for each time point).

Tolerability was similar across the study, and treatment-related adverse effects were mild, although 44% of the tofacitinib group did report experiencing some form of infection, infestation, or other complication. Two people in the study group dropped out because of the severity of their treatment-emergent adverse events. There were no reported severe or serious infections.

Dr. Bissonnette has numerous pharmaceutical industry relationships, including with Pfizer, the study’s sponsor.

FROM BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Tofacitinib showed significant improvements across all endpoints and for pruritus at week 4, compared with vehicle (P less than .001)

Data source: Multicenter, phase IIa, 4-week, double-blind, controlled study of 69 adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis randomly assigned to either 2% tofacitinib or vehicle ointment twice daily.

Disclosures: Dr. Bissonnette has numerous pharmaceutical industry relationships, including with Pfizer, the sponsor of this study.

Therapeutic alternative to liver transplantation could be on horizon in NASH

BOSTON – A novel therapeutic approach to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis could one day mean sufferers of this severe form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease have an alternative to transplantation.

Preclinical findings from a study using mesenchymal stem cells adapted from unsuitable organs for transplant have shown promise in suppressing inflammation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

By adding an inflammatory cocktail to cell cultures, with or without immunosuppression with cyclosporine, Dr. Gellynck and his colleagues were able to provoke secretion of anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic cytokines. HepaStem was shown to inhibit the T-lymphocyte response to the inflammation and also suppress the dendritic cell generation and function in co-culture experiments. In a NASH disease model culture, the immunosuppression did not solely affect disease progression, but cell-based treatment significantly and dose-dependently decreased collagen levels. A single HepaStem injection “significantly” decreased the nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity disease score, supporting the proposed mechanism of action, namely reduced inflammation.

Dr. Gellynck and his colleagues believe their findings warrant phase I/II studies in humans with NASH.

All study workers are employed by Promethera Biosciences.

BOSTON – A novel therapeutic approach to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis could one day mean sufferers of this severe form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease have an alternative to transplantation.

Preclinical findings from a study using mesenchymal stem cells adapted from unsuitable organs for transplant have shown promise in suppressing inflammation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

By adding an inflammatory cocktail to cell cultures, with or without immunosuppression with cyclosporine, Dr. Gellynck and his colleagues were able to provoke secretion of anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic cytokines. HepaStem was shown to inhibit the T-lymphocyte response to the inflammation and also suppress the dendritic cell generation and function in co-culture experiments. In a NASH disease model culture, the immunosuppression did not solely affect disease progression, but cell-based treatment significantly and dose-dependently decreased collagen levels. A single HepaStem injection “significantly” decreased the nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity disease score, supporting the proposed mechanism of action, namely reduced inflammation.

Dr. Gellynck and his colleagues believe their findings warrant phase I/II studies in humans with NASH.

All study workers are employed by Promethera Biosciences.

BOSTON – A novel therapeutic approach to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis could one day mean sufferers of this severe form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease have an alternative to transplantation.

Preclinical findings from a study using mesenchymal stem cells adapted from unsuitable organs for transplant have shown promise in suppressing inflammation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

By adding an inflammatory cocktail to cell cultures, with or without immunosuppression with cyclosporine, Dr. Gellynck and his colleagues were able to provoke secretion of anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic cytokines. HepaStem was shown to inhibit the T-lymphocyte response to the inflammation and also suppress the dendritic cell generation and function in co-culture experiments. In a NASH disease model culture, the immunosuppression did not solely affect disease progression, but cell-based treatment significantly and dose-dependently decreased collagen levels. A single HepaStem injection “significantly” decreased the nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity disease score, supporting the proposed mechanism of action, namely reduced inflammation.

Dr. Gellynck and his colleagues believe their findings warrant phase I/II studies in humans with NASH.

All study workers are employed by Promethera Biosciences.

FROM THE LIVER MEETING 2016

Cenicriviroc was well-tolerated but did not outperform placebo across all endpoints

Cenicriviroc, an oral chemokine receptor CCR/5 antagonist, was well tolerated, although it did not best placebo across all study endpoints, according to results of a 1-year phase IIb study released in an abstract in advance of the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

A correlation between treatment benefit and disease severity was reported by Arun J. Sanyal, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, and coworkers, however.

In the 2-year, multinational, phase IIb, double-blind CENTAUR (Efficacy and Safety Study of Cenicriviroc for the Treatment of NASH in Adult Subjects With Liver Fibrosis) study, 289 adults with chronic liver disease were randomly assigned to either 150 mg cenicriviroc (CVC) once daily or to placebo. At baseline, study participants had either histologically defined nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease score (NAS) of 4 or greater, or liver fibrosis between stages 1 and 3. Just over half of the cohort were women, 72% had metabolic syndrome, and 53% had diabetes. Three-quarters had an NAS score of 5 or higher, and 67% had fibrosis between stages 2 and 3. The mean body mass index across the study was 34 kg/m2.

At 1 year, liver biopsy showed that 16% of the CVC group had achieved at least a 2-point improvement in NAS, 3% less than controls (P = .519). Resolution of steatohepatitis with no worsening of fibrosis was higher in the study arm, compared with controls: 8% vs. 6% (P = .494). A significant difference was seen in members of the study arm who had advanced disease characteristics at baseline, compared with controls, by at least one stage in fibrosis improvement, with no worsening of steatohepatitis (P = .023). Across the study, improvement in fibrosis by two stages was seen in eight patients given CVC and in three controls. Progression to cirrhosis occurred in two members of the study arm and in five controls.

Adverse treatment-related events were similar across the study. The most commonly reported were fatigue (2.8%) and diarrhea (2.1%) in the study arm and headache (3.5%) in controls.

Most of the researchers associated with this study have industry relationships, including Brian L. Wiens, PhD, Pamela Vig, PhD, Star Seyedkazemi, PharmD, and Eric Lefebvre, MD, all of whom are employed by study sponsor, Tobira Therapeutics.

Cenicriviroc, an oral chemokine receptor CCR/5 antagonist, was well tolerated, although it did not best placebo across all study endpoints, according to results of a 1-year phase IIb study released in an abstract in advance of the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

A correlation between treatment benefit and disease severity was reported by Arun J. Sanyal, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, and coworkers, however.

In the 2-year, multinational, phase IIb, double-blind CENTAUR (Efficacy and Safety Study of Cenicriviroc for the Treatment of NASH in Adult Subjects With Liver Fibrosis) study, 289 adults with chronic liver disease were randomly assigned to either 150 mg cenicriviroc (CVC) once daily or to placebo. At baseline, study participants had either histologically defined nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease score (NAS) of 4 or greater, or liver fibrosis between stages 1 and 3. Just over half of the cohort were women, 72% had metabolic syndrome, and 53% had diabetes. Three-quarters had an NAS score of 5 or higher, and 67% had fibrosis between stages 2 and 3. The mean body mass index across the study was 34 kg/m2.

At 1 year, liver biopsy showed that 16% of the CVC group had achieved at least a 2-point improvement in NAS, 3% less than controls (P = .519). Resolution of steatohepatitis with no worsening of fibrosis was higher in the study arm, compared with controls: 8% vs. 6% (P = .494). A significant difference was seen in members of the study arm who had advanced disease characteristics at baseline, compared with controls, by at least one stage in fibrosis improvement, with no worsening of steatohepatitis (P = .023). Across the study, improvement in fibrosis by two stages was seen in eight patients given CVC and in three controls. Progression to cirrhosis occurred in two members of the study arm and in five controls.

Adverse treatment-related events were similar across the study. The most commonly reported were fatigue (2.8%) and diarrhea (2.1%) in the study arm and headache (3.5%) in controls.

Most of the researchers associated with this study have industry relationships, including Brian L. Wiens, PhD, Pamela Vig, PhD, Star Seyedkazemi, PharmD, and Eric Lefebvre, MD, all of whom are employed by study sponsor, Tobira Therapeutics.

Cenicriviroc, an oral chemokine receptor CCR/5 antagonist, was well tolerated, although it did not best placebo across all study endpoints, according to results of a 1-year phase IIb study released in an abstract in advance of the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

A correlation between treatment benefit and disease severity was reported by Arun J. Sanyal, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, and coworkers, however.

In the 2-year, multinational, phase IIb, double-blind CENTAUR (Efficacy and Safety Study of Cenicriviroc for the Treatment of NASH in Adult Subjects With Liver Fibrosis) study, 289 adults with chronic liver disease were randomly assigned to either 150 mg cenicriviroc (CVC) once daily or to placebo. At baseline, study participants had either histologically defined nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease score (NAS) of 4 or greater, or liver fibrosis between stages 1 and 3. Just over half of the cohort were women, 72% had metabolic syndrome, and 53% had diabetes. Three-quarters had an NAS score of 5 or higher, and 67% had fibrosis between stages 2 and 3. The mean body mass index across the study was 34 kg/m2.

At 1 year, liver biopsy showed that 16% of the CVC group had achieved at least a 2-point improvement in NAS, 3% less than controls (P = .519). Resolution of steatohepatitis with no worsening of fibrosis was higher in the study arm, compared with controls: 8% vs. 6% (P = .494). A significant difference was seen in members of the study arm who had advanced disease characteristics at baseline, compared with controls, by at least one stage in fibrosis improvement, with no worsening of steatohepatitis (P = .023). Across the study, improvement in fibrosis by two stages was seen in eight patients given CVC and in three controls. Progression to cirrhosis occurred in two members of the study arm and in five controls.

Adverse treatment-related events were similar across the study. The most commonly reported were fatigue (2.8%) and diarrhea (2.1%) in the study arm and headache (3.5%) in controls.

Most of the researchers associated with this study have industry relationships, including Brian L. Wiens, PhD, Pamela Vig, PhD, Star Seyedkazemi, PharmD, and Eric Lefebvre, MD, all of whom are employed by study sponsor, Tobira Therapeutics.

FROM THE LIVER MEETING 2016

Low parental confidence in HPV vaccine stymies adolescent vaccination rates

More than a quarter of U.S. parents surveyed refused human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for their adolescents because of a lack of overall trust in adolescent vaccination programs and higher levels of perceived harm, a study found.

In an online survey of 1,484 U.S. parents, 28% of respondents reported they had refused the HPV vaccine on behalf of their children aged 11-17 years at least once. Another 8% responded they had elected to delay vaccination. The remaining two-thirds of respondents said they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccination, reported Melissa B. Gilkey, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates (Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1247134).

Compared with parents who reported neither refusal nor delay, refusal was associated with lower confidence in adolescent vaccination (relative risk ratio = 0.66, 95% CI, 0.48-0.91), lower perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness (RRR = 0.68, 95% CI, 0.50-0.91), and higher perceived harms (RRR = 3.49, 95% CI, 2.65-4.60). Parents who reported delaying vaccination were more likely to endorse insufficient information as the reason (RRR = 1.76, 95% CI, 1.08-2.85). While 79% of parents who had delayed HPV vaccination said talking with a physician would help them with their decision, 61% of parents who refused the vaccination said it would. In addition, nearly half of parents who delayed vaccination said they did so out of a preference to wait until their children were older.

In adolescents whose parents had ever refused the vaccine, only 27% had received one HPV vaccine vs. 59% in those whose parents had elected to delay vaccination. Among adolescents whose parents responded they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccine, 56% had received one HPV vaccine.

Although the investigators did not find race, ethnicity, nor educational attainment were drivers of whether a parent chose to vaccinate, families with higher income levels tended to refuse the HPV vaccine more often than did other parents (RRR: 1.48, 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.15).

Merck and the National Cancer Institute funded the study. Coauthor Noel T. Brewer, PhD, has received HPV vaccine-related grants from, or been on paid advisory boards for, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer; he served on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee Working Group on HPV Vaccine and is chair of the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable.

More than a quarter of U.S. parents surveyed refused human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for their adolescents because of a lack of overall trust in adolescent vaccination programs and higher levels of perceived harm, a study found.

In an online survey of 1,484 U.S. parents, 28% of respondents reported they had refused the HPV vaccine on behalf of their children aged 11-17 years at least once. Another 8% responded they had elected to delay vaccination. The remaining two-thirds of respondents said they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccination, reported Melissa B. Gilkey, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates (Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1247134).

Compared with parents who reported neither refusal nor delay, refusal was associated with lower confidence in adolescent vaccination (relative risk ratio = 0.66, 95% CI, 0.48-0.91), lower perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness (RRR = 0.68, 95% CI, 0.50-0.91), and higher perceived harms (RRR = 3.49, 95% CI, 2.65-4.60). Parents who reported delaying vaccination were more likely to endorse insufficient information as the reason (RRR = 1.76, 95% CI, 1.08-2.85). While 79% of parents who had delayed HPV vaccination said talking with a physician would help them with their decision, 61% of parents who refused the vaccination said it would. In addition, nearly half of parents who delayed vaccination said they did so out of a preference to wait until their children were older.

In adolescents whose parents had ever refused the vaccine, only 27% had received one HPV vaccine vs. 59% in those whose parents had elected to delay vaccination. Among adolescents whose parents responded they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccine, 56% had received one HPV vaccine.

Although the investigators did not find race, ethnicity, nor educational attainment were drivers of whether a parent chose to vaccinate, families with higher income levels tended to refuse the HPV vaccine more often than did other parents (RRR: 1.48, 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.15).

Merck and the National Cancer Institute funded the study. Coauthor Noel T. Brewer, PhD, has received HPV vaccine-related grants from, or been on paid advisory boards for, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer; he served on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee Working Group on HPV Vaccine and is chair of the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable.

More than a quarter of U.S. parents surveyed refused human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for their adolescents because of a lack of overall trust in adolescent vaccination programs and higher levels of perceived harm, a study found.

In an online survey of 1,484 U.S. parents, 28% of respondents reported they had refused the HPV vaccine on behalf of their children aged 11-17 years at least once. Another 8% responded they had elected to delay vaccination. The remaining two-thirds of respondents said they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccination, reported Melissa B. Gilkey, PhD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and her associates (Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1247134).

Compared with parents who reported neither refusal nor delay, refusal was associated with lower confidence in adolescent vaccination (relative risk ratio = 0.66, 95% CI, 0.48-0.91), lower perceived HPV vaccine effectiveness (RRR = 0.68, 95% CI, 0.50-0.91), and higher perceived harms (RRR = 3.49, 95% CI, 2.65-4.60). Parents who reported delaying vaccination were more likely to endorse insufficient information as the reason (RRR = 1.76, 95% CI, 1.08-2.85). While 79% of parents who had delayed HPV vaccination said talking with a physician would help them with their decision, 61% of parents who refused the vaccination said it would. In addition, nearly half of parents who delayed vaccination said they did so out of a preference to wait until their children were older.

In adolescents whose parents had ever refused the vaccine, only 27% had received one HPV vaccine vs. 59% in those whose parents had elected to delay vaccination. Among adolescents whose parents responded they had neither refused nor delayed the vaccine, 56% had received one HPV vaccine.

Although the investigators did not find race, ethnicity, nor educational attainment were drivers of whether a parent chose to vaccinate, families with higher income levels tended to refuse the HPV vaccine more often than did other parents (RRR: 1.48, 95% confidence interval, 1.02-2.15).

Merck and the National Cancer Institute funded the study. Coauthor Noel T. Brewer, PhD, has received HPV vaccine-related grants from, or been on paid advisory boards for, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer; he served on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee Working Group on HPV Vaccine and is chair of the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: HPV vaccine refusal rate was 28% in parents of teens and preteens; the rate of vaccine delay was 8%.

Data source: Online survey conducted in 2014-2015 of 1,484 U.S. parents with children between ages of 11 and 17 years.

Disclosures: Merck and the National Cancer Institute funded the study. Coauthor Noel T. Brewer, PhD, has received HPV vaccine-related grants from, or been on paid advisory boards for, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer; he served on the National Vaccine Advisory Committee Working Group on HPV Vaccine and is chair of the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable.

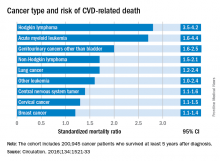

Cancer type, age at time of diagnosis implicated in risk of CVD-related deaths

Survivorship data derived from a U.K. cancer registry make it possible to more closely pinpoint the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients treated for cancer as adolescents and young adults.

Researchers report that 6% of the 2,016 deaths occurring in 200,945 cancer survivors diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 39 years were directly related to cardiovascular disease. A multivariable Poisson regression analysis of data from the Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Survivor Study also showed that survivors who were diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 19 years had 4.2 times the risk (95% confidence interval, 3.4-5.2) of death from cardiovascular disease, compared with their peers in the general population. But for survivors who were aged 35-39 years when diagnosed, that risk decreased to 1.2 times (95% CI, 1.1-1.3) that of their general population peers (P less than .0001). The standardized mortality ratios and absolute excess risks for ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, and cardiomyopathy were similar (Circulation. 2016;134:1521-33).

The findings should help clinicians craft more effective after-cancer care, according to Mike Hawkins, DPhil. “It helps them focus the most intensive follow-up care on those most at risk,” Dr. Hawkins, an epidemiology professor and director of the Centre for Childhood Cancer Survivor Studies at the University of Birmingham (England), said in a statement. “It is important for survivors because it empowers them by providing them with their long-term chances of a specific side effect of cancer treatment.”

The most significant relationship between cardiovascular disease and cancer occurred in those diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma, and at an earlier age. Overall, Hodgkin lymphoma survivors had a 3.8 times higher risk of cardiovascular disease–related death than their peers not diagnosed with any cancer. In those diagnosed at age 15-19 years, 6.9% had died from cardiovascular disease by age 55 years, compared with 2% of those who’d been diagnosed at age 35-39 years. Among these two age groups in the general population, fewer than 1% typically die from cardiovascular disease–related deaths. In Hodgkin lymphoma survivors aged 60 years or older, 27.5% of excess deaths were from cardiovascular disease.

Although not stratified by treatment, the study includes risk estimates for other cancers diagnosed in the teen and young adult years, stratified by the age at diagnosis, something the authors of the study noted is “a considerable advance on previous knowledge.”

Survivors of all age groups in the cohort diagnosed with a variety of cancers experienced a greater risk of death from heart disease, compared with their peers in the general population.

Survivorship data derived from a U.K. cancer registry make it possible to more closely pinpoint the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients treated for cancer as adolescents and young adults.

Researchers report that 6% of the 2,016 deaths occurring in 200,945 cancer survivors diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 39 years were directly related to cardiovascular disease. A multivariable Poisson regression analysis of data from the Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Survivor Study also showed that survivors who were diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 19 years had 4.2 times the risk (95% confidence interval, 3.4-5.2) of death from cardiovascular disease, compared with their peers in the general population. But for survivors who were aged 35-39 years when diagnosed, that risk decreased to 1.2 times (95% CI, 1.1-1.3) that of their general population peers (P less than .0001). The standardized mortality ratios and absolute excess risks for ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, and cardiomyopathy were similar (Circulation. 2016;134:1521-33).

The findings should help clinicians craft more effective after-cancer care, according to Mike Hawkins, DPhil. “It helps them focus the most intensive follow-up care on those most at risk,” Dr. Hawkins, an epidemiology professor and director of the Centre for Childhood Cancer Survivor Studies at the University of Birmingham (England), said in a statement. “It is important for survivors because it empowers them by providing them with their long-term chances of a specific side effect of cancer treatment.”

The most significant relationship between cardiovascular disease and cancer occurred in those diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma, and at an earlier age. Overall, Hodgkin lymphoma survivors had a 3.8 times higher risk of cardiovascular disease–related death than their peers not diagnosed with any cancer. In those diagnosed at age 15-19 years, 6.9% had died from cardiovascular disease by age 55 years, compared with 2% of those who’d been diagnosed at age 35-39 years. Among these two age groups in the general population, fewer than 1% typically die from cardiovascular disease–related deaths. In Hodgkin lymphoma survivors aged 60 years or older, 27.5% of excess deaths were from cardiovascular disease.

Although not stratified by treatment, the study includes risk estimates for other cancers diagnosed in the teen and young adult years, stratified by the age at diagnosis, something the authors of the study noted is “a considerable advance on previous knowledge.”

Survivors of all age groups in the cohort diagnosed with a variety of cancers experienced a greater risk of death from heart disease, compared with their peers in the general population.

Survivorship data derived from a U.K. cancer registry make it possible to more closely pinpoint the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients treated for cancer as adolescents and young adults.

Researchers report that 6% of the 2,016 deaths occurring in 200,945 cancer survivors diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 39 years were directly related to cardiovascular disease. A multivariable Poisson regression analysis of data from the Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Survivor Study also showed that survivors who were diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 19 years had 4.2 times the risk (95% confidence interval, 3.4-5.2) of death from cardiovascular disease, compared with their peers in the general population. But for survivors who were aged 35-39 years when diagnosed, that risk decreased to 1.2 times (95% CI, 1.1-1.3) that of their general population peers (P less than .0001). The standardized mortality ratios and absolute excess risks for ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, and cardiomyopathy were similar (Circulation. 2016;134:1521-33).

The findings should help clinicians craft more effective after-cancer care, according to Mike Hawkins, DPhil. “It helps them focus the most intensive follow-up care on those most at risk,” Dr. Hawkins, an epidemiology professor and director of the Centre for Childhood Cancer Survivor Studies at the University of Birmingham (England), said in a statement. “It is important for survivors because it empowers them by providing them with their long-term chances of a specific side effect of cancer treatment.”

The most significant relationship between cardiovascular disease and cancer occurred in those diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma, and at an earlier age. Overall, Hodgkin lymphoma survivors had a 3.8 times higher risk of cardiovascular disease–related death than their peers not diagnosed with any cancer. In those diagnosed at age 15-19 years, 6.9% had died from cardiovascular disease by age 55 years, compared with 2% of those who’d been diagnosed at age 35-39 years. Among these two age groups in the general population, fewer than 1% typically die from cardiovascular disease–related deaths. In Hodgkin lymphoma survivors aged 60 years or older, 27.5% of excess deaths were from cardiovascular disease.

Although not stratified by treatment, the study includes risk estimates for other cancers diagnosed in the teen and young adult years, stratified by the age at diagnosis, something the authors of the study noted is “a considerable advance on previous knowledge.”

Survivors of all age groups in the cohort diagnosed with a variety of cancers experienced a greater risk of death from heart disease, compared with their peers in the general population.

FROM CIRCULATION

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Cancer survivors who were diagnosed at age 15-19 years had 4.2 times the risk of death from cardiovascular disease than did their peers in the general population.

Data source: A U.K. cancer registry of 200,945 persons between 15 and 39 years at time of diagnosis.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research in the United Kingdom. The authors had no relevant disclosures.

Shorter duration of untreated psychosis key to Navy program’s approach to schizophrenia care

WASHINGTON – Medical treatment of first-episode psychosis alone is a “cornerstone” intervention, but it’s not sufficient, according to a U.S. Navy psychiatrist who annually treats about 75 people with serious mental illness.

“We need coordinated, multimodal care for optimal treatment of psychosis,” said Michael C. Hann, MD, a Navy psychiatrist and a speaker during a panel on integrated care for schizophrenia at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

By moving away from the standard model in the past 3 years, and instead implementing a coordinated, recovery-oriented system of care as outlined in the National Institute of Mental Health’s RAISE study (Recovery After Initial Schizophrenia Episode), Dr. Hann said the Navy has seen impressive results: In six patients seen recently, the estimated duration of psychosis – the time between prodromal symptoms and first signs of a psychotic break – was as little as 6 weeks and no more than about 9 weeks.

“That is very, very short,” Dr. Hann said. “We’re very excited about that.”

The shorter the duration between first signs of psychosis and treatment, the greater chance a person has to sustain his capacity to function in his community, and enjoy higher a quality of life, according to the NIMH’s webpage about the RAISE trial.

Located at the Navy Medical Center San Diego, the Psychiatric Transition Program treats active-duty military personnel with first-episode psychosis, and also those with bipolar I disorder. Patients in the program are treated for up to 9 or 12 months, before being medically retired from service. Rates of psychosis seen in the military mirror those in the general population – about 1%. “That’s about 300 first breaks a year,” Dr. Hann, the program’s chief resident, said in an interview. “We capture about 20% of those, which is the upper limit of what we’re capable of [caring for],” he said in his presentation, noting that the program is growing as its reputation has spread across the service branches. Dr. Hann said part of the program’s success comes from the swift referrals by military commanders who are alert to signs and symptoms of psychosis.

Other strengths Dr. Hann listed are that all necessary services – including the emergency department, inpatient psychiatric services, and the outpatient clinic – are colocated. Access to inpatient psychiatric services means medication monitoring and modifications, such as being switched to a long-acting injectable antipsychotic, is easier to manage, particularly in high-risk patients. Peer support also is available through a group home model.

The program is staffed by psychiatrists, psychiatry residents, psychiatric technicians, social workers, and nurses who function as case managers. In an interview, Dr. Hann said the program typically has 30 patients in treatment at a time, with an annual average of 75 patients. Most of the patients are on the schizophrenia spectrum, although the program also accepts referrals for bipolar I.

“Currently, there is very little coordination between military and VA-based care systems,” Dr. Yoon said during the presentation. “After [these service personnel] are medically retired, they kind of go off into the wind, and it’s unclear what happens. Our preliminary data show it’s pretty bad.” This lack of coordinated transition puts affected veterans at greater risk of homelessness and suicide, Dr. Yoon said.

Because at present, there is no systematized way for medical personnel in the Department of Defense and the VA to communicate, simple measures that would help keep this patient population stable are not achieved, said Dr. Yoon. With its intended launch in January 2017, OPTICARE is intended to be the bridge between the two systems during the peritransition period, covering the 6 months prior to medical retirement to 1 year post discharge. “None of what we’re doing is rocket science, but none of it is currently being done,” he said.

Dr. Yoon, whose work focuses on how to stabilize faulty striatal dopamine signaling at the D2 receptor to minimize the duration of untreated psychosis, said using aripiprazole to maintain steady levels of D2 blocking is effective. In addition, Dr. Yoon said, he believes that emerging evidence for the stabilizing effects on D2 blocking that long-acting injectable antipsychotics provide mean they should be used more. However, this kind of evidence-based approach to care is frustrated by quirks between the two systems, such as the absence of a shared pharmacy formulary. This can lead to a person’s antipsychotic agent being switched or even noncompliance, and the possible end result can be relapse.

Dr. Yoon also emphasizes ways he expects OPTICARE can help use psychosocial support to minimize stress for patients, since stress disrupts a steady dopamine release in the brain.

“Although schizophrenia is incredibly complex and there is so much more we don’t know, enough coherent and consistent evidence is starting to emerge that I think can provide a unifying framework that should inform treatment decisions at these levels, Dr. Yoon said.

The opinions are the speakers’ own and do not represent those of the U.S. Navy.

WASHINGTON – Medical treatment of first-episode psychosis alone is a “cornerstone” intervention, but it’s not sufficient, according to a U.S. Navy psychiatrist who annually treats about 75 people with serious mental illness.

“We need coordinated, multimodal care for optimal treatment of psychosis,” said Michael C. Hann, MD, a Navy psychiatrist and a speaker during a panel on integrated care for schizophrenia at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

By moving away from the standard model in the past 3 years, and instead implementing a coordinated, recovery-oriented system of care as outlined in the National Institute of Mental Health’s RAISE study (Recovery After Initial Schizophrenia Episode), Dr. Hann said the Navy has seen impressive results: In six patients seen recently, the estimated duration of psychosis – the time between prodromal symptoms and first signs of a psychotic break – was as little as 6 weeks and no more than about 9 weeks.

“That is very, very short,” Dr. Hann said. “We’re very excited about that.”

The shorter the duration between first signs of psychosis and treatment, the greater chance a person has to sustain his capacity to function in his community, and enjoy higher a quality of life, according to the NIMH’s webpage about the RAISE trial.

Located at the Navy Medical Center San Diego, the Psychiatric Transition Program treats active-duty military personnel with first-episode psychosis, and also those with bipolar I disorder. Patients in the program are treated for up to 9 or 12 months, before being medically retired from service. Rates of psychosis seen in the military mirror those in the general population – about 1%. “That’s about 300 first breaks a year,” Dr. Hann, the program’s chief resident, said in an interview. “We capture about 20% of those, which is the upper limit of what we’re capable of [caring for],” he said in his presentation, noting that the program is growing as its reputation has spread across the service branches. Dr. Hann said part of the program’s success comes from the swift referrals by military commanders who are alert to signs and symptoms of psychosis.

Other strengths Dr. Hann listed are that all necessary services – including the emergency department, inpatient psychiatric services, and the outpatient clinic – are colocated. Access to inpatient psychiatric services means medication monitoring and modifications, such as being switched to a long-acting injectable antipsychotic, is easier to manage, particularly in high-risk patients. Peer support also is available through a group home model.

The program is staffed by psychiatrists, psychiatry residents, psychiatric technicians, social workers, and nurses who function as case managers. In an interview, Dr. Hann said the program typically has 30 patients in treatment at a time, with an annual average of 75 patients. Most of the patients are on the schizophrenia spectrum, although the program also accepts referrals for bipolar I.

“Currently, there is very little coordination between military and VA-based care systems,” Dr. Yoon said during the presentation. “After [these service personnel] are medically retired, they kind of go off into the wind, and it’s unclear what happens. Our preliminary data show it’s pretty bad.” This lack of coordinated transition puts affected veterans at greater risk of homelessness and suicide, Dr. Yoon said.

Because at present, there is no systematized way for medical personnel in the Department of Defense and the VA to communicate, simple measures that would help keep this patient population stable are not achieved, said Dr. Yoon. With its intended launch in January 2017, OPTICARE is intended to be the bridge between the two systems during the peritransition period, covering the 6 months prior to medical retirement to 1 year post discharge. “None of what we’re doing is rocket science, but none of it is currently being done,” he said.

Dr. Yoon, whose work focuses on how to stabilize faulty striatal dopamine signaling at the D2 receptor to minimize the duration of untreated psychosis, said using aripiprazole to maintain steady levels of D2 blocking is effective. In addition, Dr. Yoon said, he believes that emerging evidence for the stabilizing effects on D2 blocking that long-acting injectable antipsychotics provide mean they should be used more. However, this kind of evidence-based approach to care is frustrated by quirks between the two systems, such as the absence of a shared pharmacy formulary. This can lead to a person’s antipsychotic agent being switched or even noncompliance, and the possible end result can be relapse.

Dr. Yoon also emphasizes ways he expects OPTICARE can help use psychosocial support to minimize stress for patients, since stress disrupts a steady dopamine release in the brain.

“Although schizophrenia is incredibly complex and there is so much more we don’t know, enough coherent and consistent evidence is starting to emerge that I think can provide a unifying framework that should inform treatment decisions at these levels, Dr. Yoon said.

The opinions are the speakers’ own and do not represent those of the U.S. Navy.

WASHINGTON – Medical treatment of first-episode psychosis alone is a “cornerstone” intervention, but it’s not sufficient, according to a U.S. Navy psychiatrist who annually treats about 75 people with serious mental illness.

“We need coordinated, multimodal care for optimal treatment of psychosis,” said Michael C. Hann, MD, a Navy psychiatrist and a speaker during a panel on integrated care for schizophrenia at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

By moving away from the standard model in the past 3 years, and instead implementing a coordinated, recovery-oriented system of care as outlined in the National Institute of Mental Health’s RAISE study (Recovery After Initial Schizophrenia Episode), Dr. Hann said the Navy has seen impressive results: In six patients seen recently, the estimated duration of psychosis – the time between prodromal symptoms and first signs of a psychotic break – was as little as 6 weeks and no more than about 9 weeks.

“That is very, very short,” Dr. Hann said. “We’re very excited about that.”

The shorter the duration between first signs of psychosis and treatment, the greater chance a person has to sustain his capacity to function in his community, and enjoy higher a quality of life, according to the NIMH’s webpage about the RAISE trial.

Located at the Navy Medical Center San Diego, the Psychiatric Transition Program treats active-duty military personnel with first-episode psychosis, and also those with bipolar I disorder. Patients in the program are treated for up to 9 or 12 months, before being medically retired from service. Rates of psychosis seen in the military mirror those in the general population – about 1%. “That’s about 300 first breaks a year,” Dr. Hann, the program’s chief resident, said in an interview. “We capture about 20% of those, which is the upper limit of what we’re capable of [caring for],” he said in his presentation, noting that the program is growing as its reputation has spread across the service branches. Dr. Hann said part of the program’s success comes from the swift referrals by military commanders who are alert to signs and symptoms of psychosis.

Other strengths Dr. Hann listed are that all necessary services – including the emergency department, inpatient psychiatric services, and the outpatient clinic – are colocated. Access to inpatient psychiatric services means medication monitoring and modifications, such as being switched to a long-acting injectable antipsychotic, is easier to manage, particularly in high-risk patients. Peer support also is available through a group home model.

The program is staffed by psychiatrists, psychiatry residents, psychiatric technicians, social workers, and nurses who function as case managers. In an interview, Dr. Hann said the program typically has 30 patients in treatment at a time, with an annual average of 75 patients. Most of the patients are on the schizophrenia spectrum, although the program also accepts referrals for bipolar I.

“Currently, there is very little coordination between military and VA-based care systems,” Dr. Yoon said during the presentation. “After [these service personnel] are medically retired, they kind of go off into the wind, and it’s unclear what happens. Our preliminary data show it’s pretty bad.” This lack of coordinated transition puts affected veterans at greater risk of homelessness and suicide, Dr. Yoon said.

Because at present, there is no systematized way for medical personnel in the Department of Defense and the VA to communicate, simple measures that would help keep this patient population stable are not achieved, said Dr. Yoon. With its intended launch in January 2017, OPTICARE is intended to be the bridge between the two systems during the peritransition period, covering the 6 months prior to medical retirement to 1 year post discharge. “None of what we’re doing is rocket science, but none of it is currently being done,” he said.

Dr. Yoon, whose work focuses on how to stabilize faulty striatal dopamine signaling at the D2 receptor to minimize the duration of untreated psychosis, said using aripiprazole to maintain steady levels of D2 blocking is effective. In addition, Dr. Yoon said, he believes that emerging evidence for the stabilizing effects on D2 blocking that long-acting injectable antipsychotics provide mean they should be used more. However, this kind of evidence-based approach to care is frustrated by quirks between the two systems, such as the absence of a shared pharmacy formulary. This can lead to a person’s antipsychotic agent being switched or even noncompliance, and the possible end result can be relapse.

Dr. Yoon also emphasizes ways he expects OPTICARE can help use psychosocial support to minimize stress for patients, since stress disrupts a steady dopamine release in the brain.

“Although schizophrenia is incredibly complex and there is so much more we don’t know, enough coherent and consistent evidence is starting to emerge that I think can provide a unifying framework that should inform treatment decisions at these levels, Dr. Yoon said.

The opinions are the speakers’ own and do not represent those of the U.S. Navy.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM INSTITUTE ON PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES

Clinician fatigue not associated with adenoma detection rates in community-based setting

Neither time of day, nor number of procedures performed by the clinician impacted adenoma detection rates in a large community-based setting, a study has shown.

Previously, mixed and scanty data on whether endoscopist fatigue correlates with colonoscopy quality in a community-based setting – where the majority of colonoscopies are performed – brought into question the link between a clinician’s detection rates and patient mortality rates due to interval cancers. Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in the U.S.

The most recent recommended adenoma detection rates – considered benchmarks of colonoscopic quality – are at or above 20% in men and at or above 30% in women, according to the American College of Gastroenterology.

A new study published online in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, however, indicates that the endoscopists working in a large, integrated, community-based health care system exceeded those quality benchmarks.

Gastroenterologist Alexander T. Lee, MD, and his colleagues identified 126 gastroenterologists in the health system, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, who performed an average of six endoscopy procedures per day – 259,064 in all – between 2010 and 2013, including 76,445 screenings and surveillance colonoscopies. They found that per physician, adenoma detection rates for screening colonoscopy examinations averaged 28.9% and 45.4% for surveillance examinations. By patient gender, the average detection rates per screening were 34.8% for men and 24.0% for women; detection rates per surveillance, the rates were 51.1% for men and 37.8% for women.

After adjusting for confounders, the investigators analyzed each physician’s average adenoma detection rates in association with the time of day each GI procedure was performed, the number of GI procedures performed before each colonoscopy, and the level of complexity of any prior procedures performed at the time of the screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Dr. Lee and his coinvestigators also found that compared with morning examinations, afternoon colonoscopies were not associated with lower adenoma detection for screening examinations, surveillance examinations, or their combination (odds ratio for combination, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.96-1.03). Additionally, neither the number of procedures performed before a given colonoscopy, nor a prior procedure’s complexity, was inversely associated with adenoma detection (OR for detection rates late in the day vs. first procedure of the day, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94-1.04).

In systems where physicians have larger daily GI procedure loads, there could be an adverse impact on adenoma detection rates, wrote Dr. Lee and his coauthors, but they also noted that quality could similarly be diluted by a lower ratio of procedures to clinician, as well. Whether other demands on a physician’s time, such as other clinical procedures or office tasks, might adversely impact detection rates, Dr. Lee and his colleagues didn’t know because they measured only the colonoscopic screening and surveillance activities. “The reported lack of an association with time of day would argue against this being a substantial factor in [this] study,” they wrote.

“The fact that increased adenoma detection was found only for screening colonoscopy examinations raises the question of whether endoscopists were systematically more vigilant during screening procedures, although the higher observed adenoma detection rates for surveillance examinations suggest otherwise,” the investigators wrote.

None of the investigators listed had any relevant disclosures.

The impact of endoscopist fatigue on colonoscopy quality is an understudied topic of great importance. The authors in this study have developed a unique objective measure of fatigue and found no association between fatigue and adenoma detection rates in a large community practice. The lack of an association may reflect the resilience of endoscopists, which is a trait to which we all aspire. One must also consider other explanations for the findings in this study: For one, the measures of fatigue used in this study have not previously been validated, although they have face validity.

Ziad F. Gellad, MD, MPH , associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and Associate Editor on the Board of GI & Hepatology News. He has no conflicts of interest.

The impact of endoscopist fatigue on colonoscopy quality is an understudied topic of great importance. The authors in this study have developed a unique objective measure of fatigue and found no association between fatigue and adenoma detection rates in a large community practice. The lack of an association may reflect the resilience of endoscopists, which is a trait to which we all aspire. One must also consider other explanations for the findings in this study: For one, the measures of fatigue used in this study have not previously been validated, although they have face validity.

Ziad F. Gellad, MD, MPH , associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and Associate Editor on the Board of GI & Hepatology News. He has no conflicts of interest.

The impact of endoscopist fatigue on colonoscopy quality is an understudied topic of great importance. The authors in this study have developed a unique objective measure of fatigue and found no association between fatigue and adenoma detection rates in a large community practice. The lack of an association may reflect the resilience of endoscopists, which is a trait to which we all aspire. One must also consider other explanations for the findings in this study: For one, the measures of fatigue used in this study have not previously been validated, although they have face validity.

Ziad F. Gellad, MD, MPH , associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., and Associate Editor on the Board of GI & Hepatology News. He has no conflicts of interest.

Neither time of day, nor number of procedures performed by the clinician impacted adenoma detection rates in a large community-based setting, a study has shown.

Previously, mixed and scanty data on whether endoscopist fatigue correlates with colonoscopy quality in a community-based setting – where the majority of colonoscopies are performed – brought into question the link between a clinician’s detection rates and patient mortality rates due to interval cancers. Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in the U.S.

The most recent recommended adenoma detection rates – considered benchmarks of colonoscopic quality – are at or above 20% in men and at or above 30% in women, according to the American College of Gastroenterology.

A new study published online in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, however, indicates that the endoscopists working in a large, integrated, community-based health care system exceeded those quality benchmarks.

Gastroenterologist Alexander T. Lee, MD, and his colleagues identified 126 gastroenterologists in the health system, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, who performed an average of six endoscopy procedures per day – 259,064 in all – between 2010 and 2013, including 76,445 screenings and surveillance colonoscopies. They found that per physician, adenoma detection rates for screening colonoscopy examinations averaged 28.9% and 45.4% for surveillance examinations. By patient gender, the average detection rates per screening were 34.8% for men and 24.0% for women; detection rates per surveillance, the rates were 51.1% for men and 37.8% for women.

After adjusting for confounders, the investigators analyzed each physician’s average adenoma detection rates in association with the time of day each GI procedure was performed, the number of GI procedures performed before each colonoscopy, and the level of complexity of any prior procedures performed at the time of the screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Dr. Lee and his coinvestigators also found that compared with morning examinations, afternoon colonoscopies were not associated with lower adenoma detection for screening examinations, surveillance examinations, or their combination (odds ratio for combination, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.96-1.03). Additionally, neither the number of procedures performed before a given colonoscopy, nor a prior procedure’s complexity, was inversely associated with adenoma detection (OR for detection rates late in the day vs. first procedure of the day, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94-1.04).

In systems where physicians have larger daily GI procedure loads, there could be an adverse impact on adenoma detection rates, wrote Dr. Lee and his coauthors, but they also noted that quality could similarly be diluted by a lower ratio of procedures to clinician, as well. Whether other demands on a physician’s time, such as other clinical procedures or office tasks, might adversely impact detection rates, Dr. Lee and his colleagues didn’t know because they measured only the colonoscopic screening and surveillance activities. “The reported lack of an association with time of day would argue against this being a substantial factor in [this] study,” they wrote.

“The fact that increased adenoma detection was found only for screening colonoscopy examinations raises the question of whether endoscopists were systematically more vigilant during screening procedures, although the higher observed adenoma detection rates for surveillance examinations suggest otherwise,” the investigators wrote.

None of the investigators listed had any relevant disclosures.

Neither time of day, nor number of procedures performed by the clinician impacted adenoma detection rates in a large community-based setting, a study has shown.

Previously, mixed and scanty data on whether endoscopist fatigue correlates with colonoscopy quality in a community-based setting – where the majority of colonoscopies are performed – brought into question the link between a clinician’s detection rates and patient mortality rates due to interval cancers. Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in the U.S.

The most recent recommended adenoma detection rates – considered benchmarks of colonoscopic quality – are at or above 20% in men and at or above 30% in women, according to the American College of Gastroenterology.

A new study published online in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, however, indicates that the endoscopists working in a large, integrated, community-based health care system exceeded those quality benchmarks.

Gastroenterologist Alexander T. Lee, MD, and his colleagues identified 126 gastroenterologists in the health system, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, who performed an average of six endoscopy procedures per day – 259,064 in all – between 2010 and 2013, including 76,445 screenings and surveillance colonoscopies. They found that per physician, adenoma detection rates for screening colonoscopy examinations averaged 28.9% and 45.4% for surveillance examinations. By patient gender, the average detection rates per screening were 34.8% for men and 24.0% for women; detection rates per surveillance, the rates were 51.1% for men and 37.8% for women.

After adjusting for confounders, the investigators analyzed each physician’s average adenoma detection rates in association with the time of day each GI procedure was performed, the number of GI procedures performed before each colonoscopy, and the level of complexity of any prior procedures performed at the time of the screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Dr. Lee and his coinvestigators also found that compared with morning examinations, afternoon colonoscopies were not associated with lower adenoma detection for screening examinations, surveillance examinations, or their combination (odds ratio for combination, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.96-1.03). Additionally, neither the number of procedures performed before a given colonoscopy, nor a prior procedure’s complexity, was inversely associated with adenoma detection (OR for detection rates late in the day vs. first procedure of the day, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94-1.04).

In systems where physicians have larger daily GI procedure loads, there could be an adverse impact on adenoma detection rates, wrote Dr. Lee and his coauthors, but they also noted that quality could similarly be diluted by a lower ratio of procedures to clinician, as well. Whether other demands on a physician’s time, such as other clinical procedures or office tasks, might adversely impact detection rates, Dr. Lee and his colleagues didn’t know because they measured only the colonoscopic screening and surveillance activities. “The reported lack of an association with time of day would argue against this being a substantial factor in [this] study,” they wrote.

“The fact that increased adenoma detection was found only for screening colonoscopy examinations raises the question of whether endoscopists were systematically more vigilant during screening procedures, although the higher observed adenoma detection rates for surveillance examinations suggest otherwise,” the investigators wrote.

None of the investigators listed had any relevant disclosures.

FROM GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Compared with morning examinations, afternoon colonoscopies were not associated with lower adenoma detection rates (OR for detection rates late in the day vs. first procedure of the day, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94-1.04).

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 126 community-based gastroenterologists who performed an average of six GI procedures daily between 2010 and 2013.

Disclosures: None of the investigators listed had any relevant disclosures.

Intravitreal sirolimus proves effective in reducing noninfectious uveitis inflammation

Intravitreal sirolimus 440 mcg or 880 mcg administered on days 1, 60, and 120, was shown to significantly improve ocular inflammation with preservation of best-corrected visual acuity in patients with noninfectious uveitis of the posterior segment, a phase III study has shown.

In the multinational SAKURA (Study Assessing Double-masked Uveitis Treatment) study, 346 study eyes were analyzed in this randomly assigned, double-masked, actively controlled study. In the study arm given intravitreal sirolimus 440 mcg, 22.8% (P = .025) met the primary endpoint of no vitreous haze (VH) at month 5 in the study eye without the aid of rescue therapy. In the group given intravitreal sirolimus 880 mcg, 16.4% (P = .182) met the primary endpoint, compared with 10.3% of active controls who were given 44 mcg intravitreal sirolimus.

For the secondary outcome, 52.6% (P = .008) of the intravitreal sirolimus 440 mcg arm had VH scores of 0 or a 0.5+ response rate at month 5. In the intravitreal sirolimus 880 mcg, 43.1% (P = .228) achieved a VH score of 0 or a 0.5+ response rate, compared with 35% of the 44 mcg active control group. Mean best-corrected visual acuity was maintained throughout the study in each study arm, with 76.9% of those who received corticosteroids at baseline in the 440 mcg study arm successfully tapering them to 5 mg per day or less by month 5, and 66.7% of those receiving corticosteroids in the 880 mcg group doing so. This was in comparison with 63.6% of those using corticosteroids in the active control group. Adverse events were similar across the study, and all doses were well tolerated. The study was funded by Santen.

Read the full study in Ophthalmology (2016;23[11]:2413-23).

Intravitreal sirolimus 440 mcg or 880 mcg administered on days 1, 60, and 120, was shown to significantly improve ocular inflammation with preservation of best-corrected visual acuity in patients with noninfectious uveitis of the posterior segment, a phase III study has shown.

In the multinational SAKURA (Study Assessing Double-masked Uveitis Treatment) study, 346 study eyes were analyzed in this randomly assigned, double-masked, actively controlled study. In the study arm given intravitreal sirolimus 440 mcg, 22.8% (P = .025) met the primary endpoint of no vitreous haze (VH) at month 5 in the study eye without the aid of rescue therapy. In the group given intravitreal sirolimus 880 mcg, 16.4% (P = .182) met the primary endpoint, compared with 10.3% of active controls who were given 44 mcg intravitreal sirolimus.

For the secondary outcome, 52.6% (P = .008) of the intravitreal sirolimus 440 mcg arm had VH scores of 0 or a 0.5+ response rate at month 5. In the intravitreal sirolimus 880 mcg, 43.1% (P = .228) achieved a VH score of 0 or a 0.5+ response rate, compared with 35% of the 44 mcg active control group. Mean best-corrected visual acuity was maintained throughout the study in each study arm, with 76.9% of those who received corticosteroids at baseline in the 440 mcg study arm successfully tapering them to 5 mg per day or less by month 5, and 66.7% of those receiving corticosteroids in the 880 mcg group doing so. This was in comparison with 63.6% of those using corticosteroids in the active control group. Adverse events were similar across the study, and all doses were well tolerated. The study was funded by Santen.

Read the full study in Ophthalmology (2016;23[11]:2413-23).

Intravitreal sirolimus 440 mcg or 880 mcg administered on days 1, 60, and 120, was shown to significantly improve ocular inflammation with preservation of best-corrected visual acuity in patients with noninfectious uveitis of the posterior segment, a phase III study has shown.

In the multinational SAKURA (Study Assessing Double-masked Uveitis Treatment) study, 346 study eyes were analyzed in this randomly assigned, double-masked, actively controlled study. In the study arm given intravitreal sirolimus 440 mcg, 22.8% (P = .025) met the primary endpoint of no vitreous haze (VH) at month 5 in the study eye without the aid of rescue therapy. In the group given intravitreal sirolimus 880 mcg, 16.4% (P = .182) met the primary endpoint, compared with 10.3% of active controls who were given 44 mcg intravitreal sirolimus.

For the secondary outcome, 52.6% (P = .008) of the intravitreal sirolimus 440 mcg arm had VH scores of 0 or a 0.5+ response rate at month 5. In the intravitreal sirolimus 880 mcg, 43.1% (P = .228) achieved a VH score of 0 or a 0.5+ response rate, compared with 35% of the 44 mcg active control group. Mean best-corrected visual acuity was maintained throughout the study in each study arm, with 76.9% of those who received corticosteroids at baseline in the 440 mcg study arm successfully tapering them to 5 mg per day or less by month 5, and 66.7% of those receiving corticosteroids in the 880 mcg group doing so. This was in comparison with 63.6% of those using corticosteroids in the active control group. Adverse events were similar across the study, and all doses were well tolerated. The study was funded by Santen.

Read the full study in Ophthalmology (2016;23[11]:2413-23).

Reframing views of patients who malinger advised

WASHINGTON – Imagine desperately wanting addiction treatment while living in a homeless shelter with many people who were using drugs. Could you remain sober for 6 weeks until treatment was available at an outpatient clinic – or would you bluff your way into treatment in an emergency department, where you would receive follow-up care within a week?

This is the kind of challenge that Margaret Balfour, MD, PhD, said she puts to her staff – and to anyone who treats patients they suspect are lying about this medical conditions. “Could [you], as a well-adjusted professional with reasonably good coping skills tolerate the things we ask our patients to do in order to help ‘appropriately’ ” asked Dr. Balfour, chief clinical officer at the Crisis Response Center in Tucson, Ariz., and a vice president for clinical innovation and quality at ConnectionsAZ in Tucson and Phoenix.

Signs of malingering

On average, 13% of the people presenting in the ED malinger, according to panelist Scott A. Simpson, MD, MPH, of the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and the medical director of psychiatric emergency services at Denver Health. So, how can a clinician differentiate whether a patient’s story is fact or fiction, and what can be done to get the real story?

Classic signs of malingering include a notable discrepancy between observed and reported symptoms, reports of atypical psychosis, and inexplicable cognitive symptoms. “Watch for things that seem odd, such as late-in-life onset of psychosis, Dr. Simpson said.

Patients who grow increasingly irritated during the patient interview, even to the point of threatening suicide if their treatment demands aren’t met, also can be patients who malinger However, some data do not necessarily support this as cause for alarm, according to Dr. Simpson, who cited a study showing that among 137 patients who endorsed suicidality, the 7-year suicide rate among those who did so conditionally was 0.0%, compared with 11% in those who did not have conditional suicidality (Psychiatr Serv. 2002 Jan;53[1]:92-4). The overall 7-year mortality in the first cohort was 4%, compared with 20% in the latter.

Rather than panic in such a situation, go deeper, said panelist John S. Rozel, MD, of the department of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, where he also completed a master of studies in law program and serves as an adjunct professor of law. Dr. Rozel also is the medical director of the university’s re:solve Crisis Network.

“Maybe the person is worried they won’t be taken seriously,” said Dr. Rozel, explaining why some patients will escalate their claims and often are oblivious to their deceit. He shared an anecdote of having been called to treat a 14-year-old trauma patient with suicidality but who didn’t endorse any thoughts of self-harm during the patient interview. Instead, she told him that being suicidal is“what you say when you need more support, and the staff aren’t paying enough attention to you.”

Documenting the behavior

Even when clinicians are sure their patient is malingering, they often are reluctant to document it, according to Rachel Rodriguez, MD, an inpatient/emergency attending psychiatrist at Bellevue Hospital Center in New York.

“Malingering is lying, and lying is distasteful. It’s difficult to talk about,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “It’s also making a judgment about someone’s intentions, which is outside the bounds of what we are trained to do.”

Clinicians are reluctant to formally identify malingering for many reasons, Dr. Rodriguez said in an interview. Those reasons include:

• Future denial of necessary care.

• Fear of retaliation.

• Concerns about making a judgment about motives/intentions.

• Risk of misidentification.

• Fear of liability.

• Feeling sorry for the patient and helpless to address the patient’s actual needs.

Dr. Rodriguez said the underidentification and overidentification of malingering also include unique sets of risks.

At the session, Dr. Rozel agreed that an unwillingness to address malingering head-on does have its risks.