User login

AAP: Teen access to abortion care is a right

.

“Genuine concern for the best interests of minors argues strongly against mandatory parental consent and notification laws,” the statement authors wrote in the updated policy statement, “The Adolescent’s Right to Confidential Care When Considering Abortion,” published online in Pediatrics.

The AAP Committee on Adolescence, which wrote the policy statement, encourages adolescents to voluntarily involve their parents – or other adults they trust – in decisions surrounding an unintended pregnancy, stating that teens who do will “likely benefit from adult experience, wisdom, emotional support, and financial support.” However, the policy statement also stresses that legally emphasizing parental involvement over a teen’s autonomy can result in barriers to care when timely access is most crucial, especially if a teen is reluctant to tell her parents of the situation (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3861).

Currently, 37 states require some level of parental involvement in an adolescent’s decision to pursue an abortion. Most of these states will allow a minor to terminate a pregnancy without parental consent in the case of a medical emergency; about half waive the parental involvement requirement when there is evidence of incest, abuse, or neglect. All states with parental involvement laws also have a so-called judicial bypass, allowing a minor to obtain an abortion with a court’s approval; however, because the process can take as long as several weeks, access to medical treatment can be delayed, upping the risk of complications from later-term abortions. Data cited in the statement indicate that following the enactment of parental involvement laws in three states, second-trimester abortion rates increased by as much as 21% (N Engl J Med. 2006;354[10]:1031-8; Fam Plann Perspect. 1995;27[3]:120-2; Women Health. 1995;22[3]:47-58.

Even when a judicial bypass is obtained, a study of 12,000 such petitions obtained in Minnesota and Massachusetts showed that only 21 of them were denied, and half of those were overturned, meaning the outcome was the same, but the potential risks of delaying care were higher (J Adolesc Health. 1991;12[2]:143-7). The AAP statement suggests physicians learn their state requirements for judicial bypass, if any.

The updated statement also refutes the notion that parental involvement laws improve communication within families and lead to better health outcomes for teens facing an unintended pregnancy. Instead, the statement says that on average, minors who discuss pregnancy termination with their parents do so at the same rate as in states with and without such laws, and that a teen is more likely to involve her parents than not, a likelihood that increases the younger a teen is. When she doesn’t choose to discuss it with parents, fear of some sort of danger such as an escalation in any ongoing family tensions, coercion into a decision, or abuse of some kind is often why (Contraception. 2010 Oct;82[4]:310-3; Fam Plann Perspect. 1992 Jul-Aug;24[4]:148-54, 173).

“In a perfect world of butterflies and unicorns, parents and kids have a perfect relationship, but we know that’s not always true. There can be significant discord in families, and parental notification could result in harm to the adolescent, or risk to the family’s tapestry with significant consequences for the family and the adolescent,” Dr. Breuner said.

Dr. Beers argued that while she believed most parents would rather be the one their teen turns to for advice in such a situation, it’s not possible to legislate trust within families, each of which has its own history and unique family culture and style of communication. “This is the type of conversation that doesn’t begin with the acute event. This is the kind of conversation that should begin [at] a very early age between a parent and a child,” she said.

The physician’s role, according to Dr. Beers, is to ensure parents and their children have “a shared understanding of the facts to [rely on] when they talk about what is important to their family and what their family values are.”

The updated statement, originally issued in 1993, roughly coincides with the release of a new Guttmacher Institute report indicating that abortion rates in the United States are at their lowest since passage of Roe v. Wade in 1973. The report credits lower unintended pregnancy rates and better access to contraception, not restrictive abortion legislation, for the drop. The AAP’s updated statement also comes within days of the inauguration of President Donald Trump, whose run-up to election featured rhetoric challenging the status quo of federal abortion laws.

Dr. Breuner said the timing was a coincidence, and that plans to reissue the statement began over 3 years ago as she and her colleagues drew up plans to recommit their membership to protecting the reproductive rights of their patients. “With all of the regulations, restrictions, and decreased access to [abortion] care that are occurring, the academy wanted members to know just how much more difficult it is to obtain an abortion,” she said, noting that access and confidentiality are not the same. “If you can’t get an abortion, what difference does confidentiality make?”

Last year, the Supreme Court reversed a law that would have greatly limited access to abortion in Texas by closing all but nine clinics statewide, burdening them with care for tens of thousands of women annually. Also in 2016, citing a Constitutional violation of a woman’s right to privacy, a federal judge blocked an Indiana law signed by then governor and now vice president Mike Pence, that restricted the reasons a woman could cite to seek an abortion.

Dr. Breuner views this as an erosion of the rights of all women to comprehensive reproductive care, including those of adolescents. “You can’t ‘Google Map’ how to figure this out anymore. The roads are closed and all the ways people say you can get there don’t really lead you there,” she said, noting that the AAP’s statement is in line with several other professional medical societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Medical Association.

Regardless of timing, the statement should be viewed not through a political – or even partisan – lens, but as a reaffirmation of “core values,” according to Dr. Beers. “We do live in divided times. I think it’s important to circle back to our core values as pediatricians. That’s the agenda – making sure adolescents are healthy, safe, and supported.”

.

“Genuine concern for the best interests of minors argues strongly against mandatory parental consent and notification laws,” the statement authors wrote in the updated policy statement, “The Adolescent’s Right to Confidential Care When Considering Abortion,” published online in Pediatrics.

The AAP Committee on Adolescence, which wrote the policy statement, encourages adolescents to voluntarily involve their parents – or other adults they trust – in decisions surrounding an unintended pregnancy, stating that teens who do will “likely benefit from adult experience, wisdom, emotional support, and financial support.” However, the policy statement also stresses that legally emphasizing parental involvement over a teen’s autonomy can result in barriers to care when timely access is most crucial, especially if a teen is reluctant to tell her parents of the situation (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3861).

Currently, 37 states require some level of parental involvement in an adolescent’s decision to pursue an abortion. Most of these states will allow a minor to terminate a pregnancy without parental consent in the case of a medical emergency; about half waive the parental involvement requirement when there is evidence of incest, abuse, or neglect. All states with parental involvement laws also have a so-called judicial bypass, allowing a minor to obtain an abortion with a court’s approval; however, because the process can take as long as several weeks, access to medical treatment can be delayed, upping the risk of complications from later-term abortions. Data cited in the statement indicate that following the enactment of parental involvement laws in three states, second-trimester abortion rates increased by as much as 21% (N Engl J Med. 2006;354[10]:1031-8; Fam Plann Perspect. 1995;27[3]:120-2; Women Health. 1995;22[3]:47-58.

Even when a judicial bypass is obtained, a study of 12,000 such petitions obtained in Minnesota and Massachusetts showed that only 21 of them were denied, and half of those were overturned, meaning the outcome was the same, but the potential risks of delaying care were higher (J Adolesc Health. 1991;12[2]:143-7). The AAP statement suggests physicians learn their state requirements for judicial bypass, if any.

The updated statement also refutes the notion that parental involvement laws improve communication within families and lead to better health outcomes for teens facing an unintended pregnancy. Instead, the statement says that on average, minors who discuss pregnancy termination with their parents do so at the same rate as in states with and without such laws, and that a teen is more likely to involve her parents than not, a likelihood that increases the younger a teen is. When she doesn’t choose to discuss it with parents, fear of some sort of danger such as an escalation in any ongoing family tensions, coercion into a decision, or abuse of some kind is often why (Contraception. 2010 Oct;82[4]:310-3; Fam Plann Perspect. 1992 Jul-Aug;24[4]:148-54, 173).

“In a perfect world of butterflies and unicorns, parents and kids have a perfect relationship, but we know that’s not always true. There can be significant discord in families, and parental notification could result in harm to the adolescent, or risk to the family’s tapestry with significant consequences for the family and the adolescent,” Dr. Breuner said.

Dr. Beers argued that while she believed most parents would rather be the one their teen turns to for advice in such a situation, it’s not possible to legislate trust within families, each of which has its own history and unique family culture and style of communication. “This is the type of conversation that doesn’t begin with the acute event. This is the kind of conversation that should begin [at] a very early age between a parent and a child,” she said.

The physician’s role, according to Dr. Beers, is to ensure parents and their children have “a shared understanding of the facts to [rely on] when they talk about what is important to their family and what their family values are.”

The updated statement, originally issued in 1993, roughly coincides with the release of a new Guttmacher Institute report indicating that abortion rates in the United States are at their lowest since passage of Roe v. Wade in 1973. The report credits lower unintended pregnancy rates and better access to contraception, not restrictive abortion legislation, for the drop. The AAP’s updated statement also comes within days of the inauguration of President Donald Trump, whose run-up to election featured rhetoric challenging the status quo of federal abortion laws.

Dr. Breuner said the timing was a coincidence, and that plans to reissue the statement began over 3 years ago as she and her colleagues drew up plans to recommit their membership to protecting the reproductive rights of their patients. “With all of the regulations, restrictions, and decreased access to [abortion] care that are occurring, the academy wanted members to know just how much more difficult it is to obtain an abortion,” she said, noting that access and confidentiality are not the same. “If you can’t get an abortion, what difference does confidentiality make?”

Last year, the Supreme Court reversed a law that would have greatly limited access to abortion in Texas by closing all but nine clinics statewide, burdening them with care for tens of thousands of women annually. Also in 2016, citing a Constitutional violation of a woman’s right to privacy, a federal judge blocked an Indiana law signed by then governor and now vice president Mike Pence, that restricted the reasons a woman could cite to seek an abortion.

Dr. Breuner views this as an erosion of the rights of all women to comprehensive reproductive care, including those of adolescents. “You can’t ‘Google Map’ how to figure this out anymore. The roads are closed and all the ways people say you can get there don’t really lead you there,” she said, noting that the AAP’s statement is in line with several other professional medical societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Medical Association.

Regardless of timing, the statement should be viewed not through a political – or even partisan – lens, but as a reaffirmation of “core values,” according to Dr. Beers. “We do live in divided times. I think it’s important to circle back to our core values as pediatricians. That’s the agenda – making sure adolescents are healthy, safe, and supported.”

.

“Genuine concern for the best interests of minors argues strongly against mandatory parental consent and notification laws,” the statement authors wrote in the updated policy statement, “The Adolescent’s Right to Confidential Care When Considering Abortion,” published online in Pediatrics.

The AAP Committee on Adolescence, which wrote the policy statement, encourages adolescents to voluntarily involve their parents – or other adults they trust – in decisions surrounding an unintended pregnancy, stating that teens who do will “likely benefit from adult experience, wisdom, emotional support, and financial support.” However, the policy statement also stresses that legally emphasizing parental involvement over a teen’s autonomy can result in barriers to care when timely access is most crucial, especially if a teen is reluctant to tell her parents of the situation (Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3861).

Currently, 37 states require some level of parental involvement in an adolescent’s decision to pursue an abortion. Most of these states will allow a minor to terminate a pregnancy without parental consent in the case of a medical emergency; about half waive the parental involvement requirement when there is evidence of incest, abuse, or neglect. All states with parental involvement laws also have a so-called judicial bypass, allowing a minor to obtain an abortion with a court’s approval; however, because the process can take as long as several weeks, access to medical treatment can be delayed, upping the risk of complications from later-term abortions. Data cited in the statement indicate that following the enactment of parental involvement laws in three states, second-trimester abortion rates increased by as much as 21% (N Engl J Med. 2006;354[10]:1031-8; Fam Plann Perspect. 1995;27[3]:120-2; Women Health. 1995;22[3]:47-58.

Even when a judicial bypass is obtained, a study of 12,000 such petitions obtained in Minnesota and Massachusetts showed that only 21 of them were denied, and half of those were overturned, meaning the outcome was the same, but the potential risks of delaying care were higher (J Adolesc Health. 1991;12[2]:143-7). The AAP statement suggests physicians learn their state requirements for judicial bypass, if any.

The updated statement also refutes the notion that parental involvement laws improve communication within families and lead to better health outcomes for teens facing an unintended pregnancy. Instead, the statement says that on average, minors who discuss pregnancy termination with their parents do so at the same rate as in states with and without such laws, and that a teen is more likely to involve her parents than not, a likelihood that increases the younger a teen is. When she doesn’t choose to discuss it with parents, fear of some sort of danger such as an escalation in any ongoing family tensions, coercion into a decision, or abuse of some kind is often why (Contraception. 2010 Oct;82[4]:310-3; Fam Plann Perspect. 1992 Jul-Aug;24[4]:148-54, 173).

“In a perfect world of butterflies and unicorns, parents and kids have a perfect relationship, but we know that’s not always true. There can be significant discord in families, and parental notification could result in harm to the adolescent, or risk to the family’s tapestry with significant consequences for the family and the adolescent,” Dr. Breuner said.

Dr. Beers argued that while she believed most parents would rather be the one their teen turns to for advice in such a situation, it’s not possible to legislate trust within families, each of which has its own history and unique family culture and style of communication. “This is the type of conversation that doesn’t begin with the acute event. This is the kind of conversation that should begin [at] a very early age between a parent and a child,” she said.

The physician’s role, according to Dr. Beers, is to ensure parents and their children have “a shared understanding of the facts to [rely on] when they talk about what is important to their family and what their family values are.”

The updated statement, originally issued in 1993, roughly coincides with the release of a new Guttmacher Institute report indicating that abortion rates in the United States are at their lowest since passage of Roe v. Wade in 1973. The report credits lower unintended pregnancy rates and better access to contraception, not restrictive abortion legislation, for the drop. The AAP’s updated statement also comes within days of the inauguration of President Donald Trump, whose run-up to election featured rhetoric challenging the status quo of federal abortion laws.

Dr. Breuner said the timing was a coincidence, and that plans to reissue the statement began over 3 years ago as she and her colleagues drew up plans to recommit their membership to protecting the reproductive rights of their patients. “With all of the regulations, restrictions, and decreased access to [abortion] care that are occurring, the academy wanted members to know just how much more difficult it is to obtain an abortion,” she said, noting that access and confidentiality are not the same. “If you can’t get an abortion, what difference does confidentiality make?”

Last year, the Supreme Court reversed a law that would have greatly limited access to abortion in Texas by closing all but nine clinics statewide, burdening them with care for tens of thousands of women annually. Also in 2016, citing a Constitutional violation of a woman’s right to privacy, a federal judge blocked an Indiana law signed by then governor and now vice president Mike Pence, that restricted the reasons a woman could cite to seek an abortion.

Dr. Breuner views this as an erosion of the rights of all women to comprehensive reproductive care, including those of adolescents. “You can’t ‘Google Map’ how to figure this out anymore. The roads are closed and all the ways people say you can get there don’t really lead you there,” she said, noting that the AAP’s statement is in line with several other professional medical societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Medical Association.

Regardless of timing, the statement should be viewed not through a political – or even partisan – lens, but as a reaffirmation of “core values,” according to Dr. Beers. “We do live in divided times. I think it’s important to circle back to our core values as pediatricians. That’s the agenda – making sure adolescents are healthy, safe, and supported.”

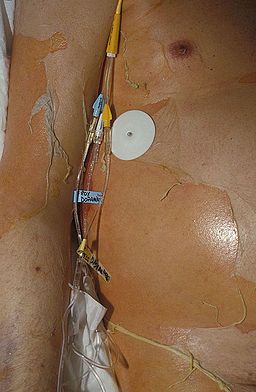

Oral, liquid supplement improves clinical outcomes in lactose-intolerant adults

Adults with self-reported lactose intolerance were shown to have significant improvement in their clinical outcomes, including abdominal pain, after consuming an oral, liquid supplement intended to increase lactose-fermenting gut bacteria, M. Andrea Azcarate-Peril, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her colleagues have shown in a small phase IIa study (Proc Nat Acad Sci. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606722113).

In a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial, randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio and conducted at two U.S. sites, highly purified (more than 95%) short-chain galactooligosaccharide (GOS) was given to 42 adults with a self-reported history of lactose intolerance, confirmed by a hydrogen breath test administered after a 25-g lactose challenge. The 20 controls were given a corn syrup mixture formulated according to the same sweetness and consistency as the test drug. Each study arm was started on its regimen at 1.5 g daily, with incremental increases in dose every 5 days until reaching 15 g. Beginning with their first dose at day 1, through day 35, all participants avoided consumption of dairy foods. Stool samples were collected from both groups at days 0 and 36. After day 36, all participants were asked to resume eating dairy foods. At day 66, stool samples were once again collected. Changes in the microbiome at all endpoints were measured by testing the stools via polymerase chain reaction.

Of the 30 study arm participants for whom complete stool samples were available, 27 were found to have had a bifidobacterial response at day 36, including a significant increase in the lactose-fermenting Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium, and Lactobacillus species. The remaining three participants in the study arm were considered nonresponders.

In an interview, Andrew Ritter, whose company, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, sponsored the trial, reported that of the 36 study arm participants who had reported abdominal pain pretreatment, 18 said they no longer had the pain at either endpoint, day 36 or day 66 (P = .019); three of 19 in the placebo group reported they no longer had abdominal pain at either endpoint. The study group was also six times more likely to report lactose tolerance at day 66 compared with their pretreatment levels (P = .0389); 28% of the placebo arm reported lactose tolerance at the endpoints. These results were previously published in Nutrition Journal in 2013. [doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-160]

“We’re super excited about these results,” said Mr. Ritter. “This is really one of the first clinical studies in a lactose-intolerant population that shows changes in the microbiome.” As to how long before the treatment will be ready for the Food and Drug Administration approval process, Mr. Ritter said, “We’re probably just a couple of years away.”

Two coauthors are advisers to Ritter Pharmaceuticals, which provided the highly purified GOS used in the study. The North Carolina Agriculture Foundation also provided funding for the study.

Adults with self-reported lactose intolerance were shown to have significant improvement in their clinical outcomes, including abdominal pain, after consuming an oral, liquid supplement intended to increase lactose-fermenting gut bacteria, M. Andrea Azcarate-Peril, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her colleagues have shown in a small phase IIa study (Proc Nat Acad Sci. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606722113).

In a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial, randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio and conducted at two U.S. sites, highly purified (more than 95%) short-chain galactooligosaccharide (GOS) was given to 42 adults with a self-reported history of lactose intolerance, confirmed by a hydrogen breath test administered after a 25-g lactose challenge. The 20 controls were given a corn syrup mixture formulated according to the same sweetness and consistency as the test drug. Each study arm was started on its regimen at 1.5 g daily, with incremental increases in dose every 5 days until reaching 15 g. Beginning with their first dose at day 1, through day 35, all participants avoided consumption of dairy foods. Stool samples were collected from both groups at days 0 and 36. After day 36, all participants were asked to resume eating dairy foods. At day 66, stool samples were once again collected. Changes in the microbiome at all endpoints were measured by testing the stools via polymerase chain reaction.

Of the 30 study arm participants for whom complete stool samples were available, 27 were found to have had a bifidobacterial response at day 36, including a significant increase in the lactose-fermenting Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium, and Lactobacillus species. The remaining three participants in the study arm were considered nonresponders.

In an interview, Andrew Ritter, whose company, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, sponsored the trial, reported that of the 36 study arm participants who had reported abdominal pain pretreatment, 18 said they no longer had the pain at either endpoint, day 36 or day 66 (P = .019); three of 19 in the placebo group reported they no longer had abdominal pain at either endpoint. The study group was also six times more likely to report lactose tolerance at day 66 compared with their pretreatment levels (P = .0389); 28% of the placebo arm reported lactose tolerance at the endpoints. These results were previously published in Nutrition Journal in 2013. [doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-160]

“We’re super excited about these results,” said Mr. Ritter. “This is really one of the first clinical studies in a lactose-intolerant population that shows changes in the microbiome.” As to how long before the treatment will be ready for the Food and Drug Administration approval process, Mr. Ritter said, “We’re probably just a couple of years away.”

Two coauthors are advisers to Ritter Pharmaceuticals, which provided the highly purified GOS used in the study. The North Carolina Agriculture Foundation also provided funding for the study.

Adults with self-reported lactose intolerance were shown to have significant improvement in their clinical outcomes, including abdominal pain, after consuming an oral, liquid supplement intended to increase lactose-fermenting gut bacteria, M. Andrea Azcarate-Peril, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her colleagues have shown in a small phase IIa study (Proc Nat Acad Sci. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606722113).

In a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial, randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio and conducted at two U.S. sites, highly purified (more than 95%) short-chain galactooligosaccharide (GOS) was given to 42 adults with a self-reported history of lactose intolerance, confirmed by a hydrogen breath test administered after a 25-g lactose challenge. The 20 controls were given a corn syrup mixture formulated according to the same sweetness and consistency as the test drug. Each study arm was started on its regimen at 1.5 g daily, with incremental increases in dose every 5 days until reaching 15 g. Beginning with their first dose at day 1, through day 35, all participants avoided consumption of dairy foods. Stool samples were collected from both groups at days 0 and 36. After day 36, all participants were asked to resume eating dairy foods. At day 66, stool samples were once again collected. Changes in the microbiome at all endpoints were measured by testing the stools via polymerase chain reaction.

Of the 30 study arm participants for whom complete stool samples were available, 27 were found to have had a bifidobacterial response at day 36, including a significant increase in the lactose-fermenting Bifidobacterium, Faecalibacterium, and Lactobacillus species. The remaining three participants in the study arm were considered nonresponders.

In an interview, Andrew Ritter, whose company, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, sponsored the trial, reported that of the 36 study arm participants who had reported abdominal pain pretreatment, 18 said they no longer had the pain at either endpoint, day 36 or day 66 (P = .019); three of 19 in the placebo group reported they no longer had abdominal pain at either endpoint. The study group was also six times more likely to report lactose tolerance at day 66 compared with their pretreatment levels (P = .0389); 28% of the placebo arm reported lactose tolerance at the endpoints. These results were previously published in Nutrition Journal in 2013. [doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-160]

“We’re super excited about these results,” said Mr. Ritter. “This is really one of the first clinical studies in a lactose-intolerant population that shows changes in the microbiome.” As to how long before the treatment will be ready for the Food and Drug Administration approval process, Mr. Ritter said, “We’re probably just a couple of years away.”

Two coauthors are advisers to Ritter Pharmaceuticals, which provided the highly purified GOS used in the study. The North Carolina Agriculture Foundation also provided funding for the study.

FROM THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES OF SCIENCE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A clinically significant response was seen in patients with lactose intolerance who were given an oral, liquid supplement intended to increase lactose-fermenting bacteria.

Data source: Phase IIa trial of 62 adults with lactose intolerance incrementally dosed with an oral, highly purified (more than 95%) short-chain galactooligosaccharide while dietary dairy was restricted.

Disclosures: Ritter Pharmaceuticals, owned by study coauthor Andrew J. Ritter, funded the study and provided the highly purified GOS used in the study. The North Carolina Agriculture Foundation also provided funding. Two coauthors are advisers to Ritter Pharmaceuticals.

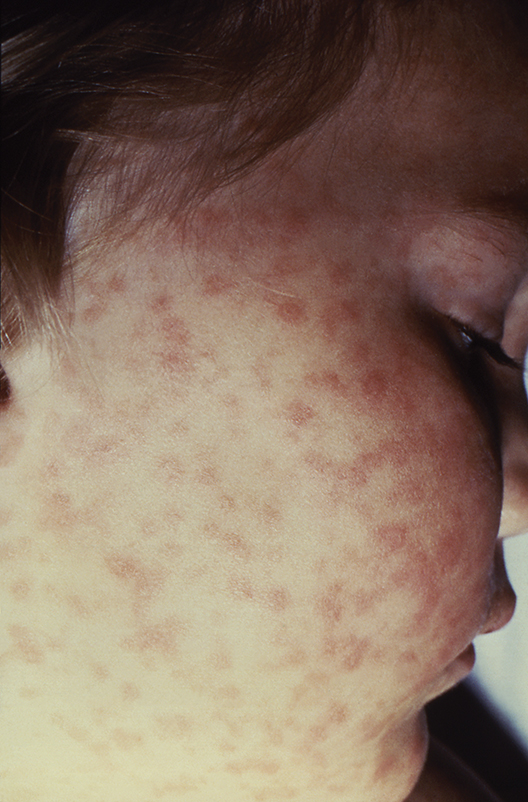

Lab values poor surrogate for detecting pediatric Rocky Mountain spotted fever in children

The three fatalities observed in a retrospective analysis of six cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) in children were associated with either a delayed diagnosis pending laboratory findings or delayed antirickettsia treatment.

“The fact that all fatal cases died before the convalescent period emphasizes that diagnosis should be based on clinical findings instead of RMSF serologic and histologic testing,” wrote the authors of a study published online in Pediatric Dermatology (2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.13053).

Two of the fatal cases involved delayed antirickettsial therapy after the patients were misdiagnosed with group A streptococcus. None of the six children were initially evaluated for R. rickettsii; they averaged three encounters with their clinician before being admitted for acute inpatient care where they received intravenous doxycycline after nearly a week of symptoms.

“All fatal cases were complicated by neurologic manifestations, including seizures, obtundation, and uncal herniation,” a finding that is consistent with the literature, the authors said.

Although the high fatality rate might be the result of the small study size, Ms. Tull and her coinvestigators concluded that the disease should be considered in all differential diagnoses for children who present with a fever and rash during the summer months in endemic areas, particularly since pediatric cases of the disease are associated with poorer outcomes than in adult cases.

Given that RMSF often remains subclinical in its early stages, and typically presents with nonspecific symptoms of fever, rash, headache, and abdominal pain when it does emerge, physicians might be tempted to defer treatment until after serologic and histologic results are in, as is the standard method. Concerns over doxycycline’s tendency to stain teeth and cause enamel hypoplasia are also common. However, empirical administration could mean the difference between life and death, since treatment within the first 5 days following infection is associated with better outcomes – an algorithm complicated by the fact that symptoms caused by R. rickettsii have been known to take as long as 21 days to appear.

In the study, Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that the average time between exposure to the tick and the onset of symptoms was 6.6 days (range, 1-21 days).

Currently, there are no diagnostic tests “that reliably diagnose RMSF during the first 7 days of illness,” and most patients “do not develop detectable antibodies until the second week of illness,” the investigators reported. Even then, sensitivity of indirect fluorescent antibody serum testing after the second week of illness is only between 86% and 94%, they noted. Further, the sensitivity of immunohistochemical (IHC) tissue staining has been reported at 70%, and false-negative IHC results are common in acute disease when antibody response is harder to detect.

Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that five of the six patients in their study had negative IHC testing; two of the six had positive serum antibody titers. For this reason, they concluded that Rocky Mountain spotted fever diagnosis should be based on “clinical history, examination, and laboratory abnormalities” rather than laboratory testing, and urged that “prompt treatment should be instituted empirically.”

The authors did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

The three fatalities observed in a retrospective analysis of six cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) in children were associated with either a delayed diagnosis pending laboratory findings or delayed antirickettsia treatment.

“The fact that all fatal cases died before the convalescent period emphasizes that diagnosis should be based on clinical findings instead of RMSF serologic and histologic testing,” wrote the authors of a study published online in Pediatric Dermatology (2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.13053).

Two of the fatal cases involved delayed antirickettsial therapy after the patients were misdiagnosed with group A streptococcus. None of the six children were initially evaluated for R. rickettsii; they averaged three encounters with their clinician before being admitted for acute inpatient care where they received intravenous doxycycline after nearly a week of symptoms.

“All fatal cases were complicated by neurologic manifestations, including seizures, obtundation, and uncal herniation,” a finding that is consistent with the literature, the authors said.

Although the high fatality rate might be the result of the small study size, Ms. Tull and her coinvestigators concluded that the disease should be considered in all differential diagnoses for children who present with a fever and rash during the summer months in endemic areas, particularly since pediatric cases of the disease are associated with poorer outcomes than in adult cases.

Given that RMSF often remains subclinical in its early stages, and typically presents with nonspecific symptoms of fever, rash, headache, and abdominal pain when it does emerge, physicians might be tempted to defer treatment until after serologic and histologic results are in, as is the standard method. Concerns over doxycycline’s tendency to stain teeth and cause enamel hypoplasia are also common. However, empirical administration could mean the difference between life and death, since treatment within the first 5 days following infection is associated with better outcomes – an algorithm complicated by the fact that symptoms caused by R. rickettsii have been known to take as long as 21 days to appear.

In the study, Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that the average time between exposure to the tick and the onset of symptoms was 6.6 days (range, 1-21 days).

Currently, there are no diagnostic tests “that reliably diagnose RMSF during the first 7 days of illness,” and most patients “do not develop detectable antibodies until the second week of illness,” the investigators reported. Even then, sensitivity of indirect fluorescent antibody serum testing after the second week of illness is only between 86% and 94%, they noted. Further, the sensitivity of immunohistochemical (IHC) tissue staining has been reported at 70%, and false-negative IHC results are common in acute disease when antibody response is harder to detect.

Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that five of the six patients in their study had negative IHC testing; two of the six had positive serum antibody titers. For this reason, they concluded that Rocky Mountain spotted fever diagnosis should be based on “clinical history, examination, and laboratory abnormalities” rather than laboratory testing, and urged that “prompt treatment should be instituted empirically.”

The authors did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

The three fatalities observed in a retrospective analysis of six cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) in children were associated with either a delayed diagnosis pending laboratory findings or delayed antirickettsia treatment.

“The fact that all fatal cases died before the convalescent period emphasizes that diagnosis should be based on clinical findings instead of RMSF serologic and histologic testing,” wrote the authors of a study published online in Pediatric Dermatology (2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.13053).

Two of the fatal cases involved delayed antirickettsial therapy after the patients were misdiagnosed with group A streptococcus. None of the six children were initially evaluated for R. rickettsii; they averaged three encounters with their clinician before being admitted for acute inpatient care where they received intravenous doxycycline after nearly a week of symptoms.

“All fatal cases were complicated by neurologic manifestations, including seizures, obtundation, and uncal herniation,” a finding that is consistent with the literature, the authors said.

Although the high fatality rate might be the result of the small study size, Ms. Tull and her coinvestigators concluded that the disease should be considered in all differential diagnoses for children who present with a fever and rash during the summer months in endemic areas, particularly since pediatric cases of the disease are associated with poorer outcomes than in adult cases.

Given that RMSF often remains subclinical in its early stages, and typically presents with nonspecific symptoms of fever, rash, headache, and abdominal pain when it does emerge, physicians might be tempted to defer treatment until after serologic and histologic results are in, as is the standard method. Concerns over doxycycline’s tendency to stain teeth and cause enamel hypoplasia are also common. However, empirical administration could mean the difference between life and death, since treatment within the first 5 days following infection is associated with better outcomes – an algorithm complicated by the fact that symptoms caused by R. rickettsii have been known to take as long as 21 days to appear.

In the study, Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that the average time between exposure to the tick and the onset of symptoms was 6.6 days (range, 1-21 days).

Currently, there are no diagnostic tests “that reliably diagnose RMSF during the first 7 days of illness,” and most patients “do not develop detectable antibodies until the second week of illness,” the investigators reported. Even then, sensitivity of indirect fluorescent antibody serum testing after the second week of illness is only between 86% and 94%, they noted. Further, the sensitivity of immunohistochemical (IHC) tissue staining has been reported at 70%, and false-negative IHC results are common in acute disease when antibody response is harder to detect.

Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that five of the six patients in their study had negative IHC testing; two of the six had positive serum antibody titers. For this reason, they concluded that Rocky Mountain spotted fever diagnosis should be based on “clinical history, examination, and laboratory abnormalities” rather than laboratory testing, and urged that “prompt treatment should be instituted empirically.”

The authors did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Half of pediatric patients diagnosed with Rocky Mountain spotted fever died after treatment was delayed.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of 6 pediatric RMSF cases among 3,912 inpatient dermatology consultations over a period of 10 years at a tertiary care center.

Disclosures: The authors did not have any relevant financial disclosures. .

Adolescents, boys, black children most likely to be hospitalized in SJS and TEN

Annual hospitalization rates in the United States for Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) were shown to be higher in adolescents, boys, and black children, in a cross-sectional analysis of discharge records from more than 4,100 hospitals.

Using relevant ICD-9 codes, researchers at Harvard University identified 1,571 patients hospitalized for SJS, TEN, or both in 2009 and 2012, as listed in the Kids Inpatient Database from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The highest hospitalization rates per 100,000 in each year were for adolescents between 15 and 19 years (P = .01), boys (P = .03), and black children (P = .82). The overall risk of death from these conditions was 1.5% in 2009 and 0.3% in 2012. The data were published online in a brief report (Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.13050).

With the number of SJS- and TEN-related hospitalizations between 0.1 and 1.0 per 100,000, lead author Yusuke Okubo MD, MPH, and his colleagues wrote that their data aligned with previous studies; however, regarding the emphasis on demographic differences, theirs was, to the best of their knowledge, “the first study to reveal these disparities.” Compared with adults, they added, mortality was “remarkably lower” in children.

The authors had no disclosures.

Annual hospitalization rates in the United States for Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) were shown to be higher in adolescents, boys, and black children, in a cross-sectional analysis of discharge records from more than 4,100 hospitals.

Using relevant ICD-9 codes, researchers at Harvard University identified 1,571 patients hospitalized for SJS, TEN, or both in 2009 and 2012, as listed in the Kids Inpatient Database from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The highest hospitalization rates per 100,000 in each year were for adolescents between 15 and 19 years (P = .01), boys (P = .03), and black children (P = .82). The overall risk of death from these conditions was 1.5% in 2009 and 0.3% in 2012. The data were published online in a brief report (Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.13050).

With the number of SJS- and TEN-related hospitalizations between 0.1 and 1.0 per 100,000, lead author Yusuke Okubo MD, MPH, and his colleagues wrote that their data aligned with previous studies; however, regarding the emphasis on demographic differences, theirs was, to the best of their knowledge, “the first study to reveal these disparities.” Compared with adults, they added, mortality was “remarkably lower” in children.

The authors had no disclosures.

Annual hospitalization rates in the United States for Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) were shown to be higher in adolescents, boys, and black children, in a cross-sectional analysis of discharge records from more than 4,100 hospitals.

Using relevant ICD-9 codes, researchers at Harvard University identified 1,571 patients hospitalized for SJS, TEN, or both in 2009 and 2012, as listed in the Kids Inpatient Database from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The highest hospitalization rates per 100,000 in each year were for adolescents between 15 and 19 years (P = .01), boys (P = .03), and black children (P = .82). The overall risk of death from these conditions was 1.5% in 2009 and 0.3% in 2012. The data were published online in a brief report (Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.13050).

With the number of SJS- and TEN-related hospitalizations between 0.1 and 1.0 per 100,000, lead author Yusuke Okubo MD, MPH, and his colleagues wrote that their data aligned with previous studies; however, regarding the emphasis on demographic differences, theirs was, to the best of their knowledge, “the first study to reveal these disparities.” Compared with adults, they added, mortality was “remarkably lower” in children.

The authors had no disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Hospitalization rates for SJS/TEN were highest among adolescents (aged 15-19) at 1.36 and 1.09 per 100,000 children in 2009 and 2012, respectively.

Data source: An analysis of 1,571 pediatric discharge records for 2009 and 2012 from more than 4,100 hospitals in a national database.

Disclosures: The authors had no disclosures.

BRAIN Initiative could help end mental illness stigma

BETHESDA, MD – Top researchers are optimistic that billions in funding for basic neuroscience research made possible by the 21st Century Cures Act will lead to breakthroughs in the understanding of brain function and dysfunction that could help end the stigma of mental illness.

Under the new law, $6.3 billion are slated for health initiatives over the next decade. The Cancer Moonshot will receive $1.8 billion, precision medicine will receive just under $1.5 billion, and the BRAIN Initiative (Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) will receive just over that amount.

“I know there have been some anxieties about the program’s fragilities given the change in administration,” Dr. Collins told an audience at a meeting of the NIH Brain Institute investigators. “But [passage of the 21st Century Cures Act] should be a source of great reassurance.”

The actual cost of the BRAIN Initiative is expected to top $4.5 billion by the year 2025, funded by a mix of federal and private monies. The National Institute of Mental Health’s typical annual budget is just under $1.5 billion – essentially the same as the amount provided for in the new law. The funds will benefit neuroscience generally, and if successful, understanding of the brain specifically.

The BRAIN Initiative funding is not for clinical studies, however. Instead, it will be spread across what Dr. Collins dubbed, “Team Science,” a multidisciplinary band of investigators, all of whom are expected to help not only identify the brain’s biologic processes but also create the tools needed to reengineer the brain’s circuitry when it malfunctions. Some current BRAIN projects Dr. Collins singled out as worth watching were the use of ultrasound neuromodulation in nonhuman primates, the analysis of individual methylone in cell nuclei, and the development of ultrahigh-resolution 3D brain imaging technology.

“We are moving toward a full bore effort toward technologies that allow us to see what is happening in real time in circuits in the brain,” Dr. Collins said. “Maybe there are certain fundamental operating principles that may have eluded us in the past but which may start to appear.”

In 2016, there were as many neuroscientists as there were engineers of all types – 141 each – named as the principal investigators of projects funded by the initiative, according to NIMH Director Joshua A. Gordon, MD, PhD, who also spoke at the meeting. Among the other disciplines Dr. Gordon said were represented in the 2016 roster of investigators were 61 radiologists, 33 biostatisticians, 47 neurosurgeons, and 69 psychiatrists and psychologists.

The enormous focus on bench science – about 85% of all NIMH funding is for nonclinical research – is not without its critics. In a recent editorial, several prominent academic clinicians urged the NIMH to spend less on futuristic neuroscience and more on the application of therapies for those with mental illness, and on their psychosocial needs (Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208[6]507-9). The last-minute inclusion in the 21st Century Cures Act of several provisions that will have a direct impact in the near future on the plight of those with severe mental illness has the potential to allay some concerns, however.

“My hope is that the [law] will be interpreted from the perspective of making effective treatments available for ... those who are already ill,” Susan M. Essock, PhD, the Edna L. Edison Professor of Medical Psychology (in Psychiatry) at Columbia University, New York, and a cosigner of the editorial, said in an interview.

The law aims to drive evidence-based grant making for programs such as the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) integrated care model and expands assisted outpatient treatment for children with serious emotional disturbance, or adults with serious mental illness, among several other provisions.

For some, the initiative’s cross-specialty structure and hefty price tag are worthwhile if it means filling the void of basic science necessary to explain the mechanics of mental illness, a void often filled with attitudes leading to the stigmatization of people who are ill.

Dr. Mayberg said she believes that a “systems approach” to behavior will emerge over time as interdisciplinary BRAIN Initiative researchers are given the freedom to make necessary discoveries, often when least expected, and are urged to share what they find. “Real fundamental changes happen by accident, in my experience. They are rarely planned. It happens when there are a lot of clues. A diversified portfolio has to be the answer, because nobody is smart enough to do it all [alone]. The goal is diversified, evidence-based approaches. ... Science has to make fundamental progress on how the brain works, because we’re obviously missing something clinically,” she said.

The ultimate goals of the initiative are to understand human beings and to improve the human condition by alleviating suffering, according to Brian Litt, MD, professor of neurology and bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and a moderator of a panel focused on the clinical implications of BRAIN research.

“If you think about the fundamental problems that affect our society and many around the world, they’re not just diseases like Parkinson’s or epilepsy, they are the disorders of mood, addiction, violence, anger, and a number of other conditions that affect behavior that are part of the neurological spectrum that affects the way our society functions,” Dr. Litt, a clinician specializing in treating people with epilepsy, told the audience.

Rather than create a neuroengineered super race, he said, fundamental neuroscience is about helping humans reach their fullest potential. For his support of this, Dr. Litt said he makes “no apologies. As a clinician, I am not sorry to be involved in fundamental neuroscience where ... incremental discoveries can create cures.”

As science favors cures, policy inevitably will evolve, perhaps even making current interventions relics of ignorance. “Psychosocial intervention is what you do when you have an absence of knowing how to cure,” said Dr. Mayberg. “It might be that [currently] what we treat is maladaptation to the primary problem.”

The key for clinicians, she said, will be to keep up with the latest literature. “Clinicians have to be aware of what’s exciting, of what should be in their armamentarium.”

Dr. Collins, Dr. Gordon, Dr. Essock, and Dr. Mayberg had no disclosures. Dr. Litt has cofounded several companies, including Blackfynn and Neuropace, and has served as a consultant and licensed technology to several companies.

BETHESDA, MD – Top researchers are optimistic that billions in funding for basic neuroscience research made possible by the 21st Century Cures Act will lead to breakthroughs in the understanding of brain function and dysfunction that could help end the stigma of mental illness.

Under the new law, $6.3 billion are slated for health initiatives over the next decade. The Cancer Moonshot will receive $1.8 billion, precision medicine will receive just under $1.5 billion, and the BRAIN Initiative (Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) will receive just over that amount.

“I know there have been some anxieties about the program’s fragilities given the change in administration,” Dr. Collins told an audience at a meeting of the NIH Brain Institute investigators. “But [passage of the 21st Century Cures Act] should be a source of great reassurance.”

The actual cost of the BRAIN Initiative is expected to top $4.5 billion by the year 2025, funded by a mix of federal and private monies. The National Institute of Mental Health’s typical annual budget is just under $1.5 billion – essentially the same as the amount provided for in the new law. The funds will benefit neuroscience generally, and if successful, understanding of the brain specifically.

The BRAIN Initiative funding is not for clinical studies, however. Instead, it will be spread across what Dr. Collins dubbed, “Team Science,” a multidisciplinary band of investigators, all of whom are expected to help not only identify the brain’s biologic processes but also create the tools needed to reengineer the brain’s circuitry when it malfunctions. Some current BRAIN projects Dr. Collins singled out as worth watching were the use of ultrasound neuromodulation in nonhuman primates, the analysis of individual methylone in cell nuclei, and the development of ultrahigh-resolution 3D brain imaging technology.

“We are moving toward a full bore effort toward technologies that allow us to see what is happening in real time in circuits in the brain,” Dr. Collins said. “Maybe there are certain fundamental operating principles that may have eluded us in the past but which may start to appear.”

In 2016, there were as many neuroscientists as there were engineers of all types – 141 each – named as the principal investigators of projects funded by the initiative, according to NIMH Director Joshua A. Gordon, MD, PhD, who also spoke at the meeting. Among the other disciplines Dr. Gordon said were represented in the 2016 roster of investigators were 61 radiologists, 33 biostatisticians, 47 neurosurgeons, and 69 psychiatrists and psychologists.

The enormous focus on bench science – about 85% of all NIMH funding is for nonclinical research – is not without its critics. In a recent editorial, several prominent academic clinicians urged the NIMH to spend less on futuristic neuroscience and more on the application of therapies for those with mental illness, and on their psychosocial needs (Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208[6]507-9). The last-minute inclusion in the 21st Century Cures Act of several provisions that will have a direct impact in the near future on the plight of those with severe mental illness has the potential to allay some concerns, however.

“My hope is that the [law] will be interpreted from the perspective of making effective treatments available for ... those who are already ill,” Susan M. Essock, PhD, the Edna L. Edison Professor of Medical Psychology (in Psychiatry) at Columbia University, New York, and a cosigner of the editorial, said in an interview.

The law aims to drive evidence-based grant making for programs such as the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) integrated care model and expands assisted outpatient treatment for children with serious emotional disturbance, or adults with serious mental illness, among several other provisions.

For some, the initiative’s cross-specialty structure and hefty price tag are worthwhile if it means filling the void of basic science necessary to explain the mechanics of mental illness, a void often filled with attitudes leading to the stigmatization of people who are ill.

Dr. Mayberg said she believes that a “systems approach” to behavior will emerge over time as interdisciplinary BRAIN Initiative researchers are given the freedom to make necessary discoveries, often when least expected, and are urged to share what they find. “Real fundamental changes happen by accident, in my experience. They are rarely planned. It happens when there are a lot of clues. A diversified portfolio has to be the answer, because nobody is smart enough to do it all [alone]. The goal is diversified, evidence-based approaches. ... Science has to make fundamental progress on how the brain works, because we’re obviously missing something clinically,” she said.

The ultimate goals of the initiative are to understand human beings and to improve the human condition by alleviating suffering, according to Brian Litt, MD, professor of neurology and bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and a moderator of a panel focused on the clinical implications of BRAIN research.

“If you think about the fundamental problems that affect our society and many around the world, they’re not just diseases like Parkinson’s or epilepsy, they are the disorders of mood, addiction, violence, anger, and a number of other conditions that affect behavior that are part of the neurological spectrum that affects the way our society functions,” Dr. Litt, a clinician specializing in treating people with epilepsy, told the audience.

Rather than create a neuroengineered super race, he said, fundamental neuroscience is about helping humans reach their fullest potential. For his support of this, Dr. Litt said he makes “no apologies. As a clinician, I am not sorry to be involved in fundamental neuroscience where ... incremental discoveries can create cures.”

As science favors cures, policy inevitably will evolve, perhaps even making current interventions relics of ignorance. “Psychosocial intervention is what you do when you have an absence of knowing how to cure,” said Dr. Mayberg. “It might be that [currently] what we treat is maladaptation to the primary problem.”

The key for clinicians, she said, will be to keep up with the latest literature. “Clinicians have to be aware of what’s exciting, of what should be in their armamentarium.”

Dr. Collins, Dr. Gordon, Dr. Essock, and Dr. Mayberg had no disclosures. Dr. Litt has cofounded several companies, including Blackfynn and Neuropace, and has served as a consultant and licensed technology to several companies.

BETHESDA, MD – Top researchers are optimistic that billions in funding for basic neuroscience research made possible by the 21st Century Cures Act will lead to breakthroughs in the understanding of brain function and dysfunction that could help end the stigma of mental illness.

Under the new law, $6.3 billion are slated for health initiatives over the next decade. The Cancer Moonshot will receive $1.8 billion, precision medicine will receive just under $1.5 billion, and the BRAIN Initiative (Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) will receive just over that amount.

“I know there have been some anxieties about the program’s fragilities given the change in administration,” Dr. Collins told an audience at a meeting of the NIH Brain Institute investigators. “But [passage of the 21st Century Cures Act] should be a source of great reassurance.”

The actual cost of the BRAIN Initiative is expected to top $4.5 billion by the year 2025, funded by a mix of federal and private monies. The National Institute of Mental Health’s typical annual budget is just under $1.5 billion – essentially the same as the amount provided for in the new law. The funds will benefit neuroscience generally, and if successful, understanding of the brain specifically.

The BRAIN Initiative funding is not for clinical studies, however. Instead, it will be spread across what Dr. Collins dubbed, “Team Science,” a multidisciplinary band of investigators, all of whom are expected to help not only identify the brain’s biologic processes but also create the tools needed to reengineer the brain’s circuitry when it malfunctions. Some current BRAIN projects Dr. Collins singled out as worth watching were the use of ultrasound neuromodulation in nonhuman primates, the analysis of individual methylone in cell nuclei, and the development of ultrahigh-resolution 3D brain imaging technology.

“We are moving toward a full bore effort toward technologies that allow us to see what is happening in real time in circuits in the brain,” Dr. Collins said. “Maybe there are certain fundamental operating principles that may have eluded us in the past but which may start to appear.”

In 2016, there were as many neuroscientists as there were engineers of all types – 141 each – named as the principal investigators of projects funded by the initiative, according to NIMH Director Joshua A. Gordon, MD, PhD, who also spoke at the meeting. Among the other disciplines Dr. Gordon said were represented in the 2016 roster of investigators were 61 radiologists, 33 biostatisticians, 47 neurosurgeons, and 69 psychiatrists and psychologists.

The enormous focus on bench science – about 85% of all NIMH funding is for nonclinical research – is not without its critics. In a recent editorial, several prominent academic clinicians urged the NIMH to spend less on futuristic neuroscience and more on the application of therapies for those with mental illness, and on their psychosocial needs (Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208[6]507-9). The last-minute inclusion in the 21st Century Cures Act of several provisions that will have a direct impact in the near future on the plight of those with severe mental illness has the potential to allay some concerns, however.

“My hope is that the [law] will be interpreted from the perspective of making effective treatments available for ... those who are already ill,” Susan M. Essock, PhD, the Edna L. Edison Professor of Medical Psychology (in Psychiatry) at Columbia University, New York, and a cosigner of the editorial, said in an interview.

The law aims to drive evidence-based grant making for programs such as the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) integrated care model and expands assisted outpatient treatment for children with serious emotional disturbance, or adults with serious mental illness, among several other provisions.

For some, the initiative’s cross-specialty structure and hefty price tag are worthwhile if it means filling the void of basic science necessary to explain the mechanics of mental illness, a void often filled with attitudes leading to the stigmatization of people who are ill.

Dr. Mayberg said she believes that a “systems approach” to behavior will emerge over time as interdisciplinary BRAIN Initiative researchers are given the freedom to make necessary discoveries, often when least expected, and are urged to share what they find. “Real fundamental changes happen by accident, in my experience. They are rarely planned. It happens when there are a lot of clues. A diversified portfolio has to be the answer, because nobody is smart enough to do it all [alone]. The goal is diversified, evidence-based approaches. ... Science has to make fundamental progress on how the brain works, because we’re obviously missing something clinically,” she said.

The ultimate goals of the initiative are to understand human beings and to improve the human condition by alleviating suffering, according to Brian Litt, MD, professor of neurology and bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and a moderator of a panel focused on the clinical implications of BRAIN research.

“If you think about the fundamental problems that affect our society and many around the world, they’re not just diseases like Parkinson’s or epilepsy, they are the disorders of mood, addiction, violence, anger, and a number of other conditions that affect behavior that are part of the neurological spectrum that affects the way our society functions,” Dr. Litt, a clinician specializing in treating people with epilepsy, told the audience.

Rather than create a neuroengineered super race, he said, fundamental neuroscience is about helping humans reach their fullest potential. For his support of this, Dr. Litt said he makes “no apologies. As a clinician, I am not sorry to be involved in fundamental neuroscience where ... incremental discoveries can create cures.”

As science favors cures, policy inevitably will evolve, perhaps even making current interventions relics of ignorance. “Psychosocial intervention is what you do when you have an absence of knowing how to cure,” said Dr. Mayberg. “It might be that [currently] what we treat is maladaptation to the primary problem.”

The key for clinicians, she said, will be to keep up with the latest literature. “Clinicians have to be aware of what’s exciting, of what should be in their armamentarium.”

Dr. Collins, Dr. Gordon, Dr. Essock, and Dr. Mayberg had no disclosures. Dr. Litt has cofounded several companies, including Blackfynn and Neuropace, and has served as a consultant and licensed technology to several companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT AN NIH ADVISORY COUNCIL MEETING

FDA eases mental health warnings in smoking cessation drugs’ labels

Labels on two smoking cessation treatments will offer less severe warnings for mental health risk potentials in people with no history of psychiatric disorders, the Food and Drug Administration has announced.

Varenicline (Chantix) will no longer include a boxed warning for serious mental health side effects. The label for bupropion (Zyban) will still include a boxed warning, but language describing the potential for serious psychiatric adverse events will no longer appear within it. Updates will also be made to both labels to describe side effects on mood, behavior, or thinking.

In addition, varenicline’s label will reflect trial data showing its superior efficacy, compared with oral bupropion or nicotine patch. Although a patient medication guide will still be included with each prescription, the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy that prompted the guide will no longer be in place.

Earlier this year, two FDA advisory committees voted in favor of updating varenicline’s label, based on data from a randomized, controlled trial of more than 8,000 smokers, half of whom had a history of psychiatric disorders.

The trial showed no clinically significant difference in risk of adverse events across the smoking cessation treatments varenicline, bupropion, nicotine patch, or placebo study arms, although the risk was higher in the psychiatric cohorts in each.

Overall, 2% of those without a history of mental illness experienced neuropsychiatric adverse events, compared with between 5% and 7% of those with such a history.

The trial was cosponsored by Pfizer, maker of Chantix, and GlaxoSmithKline, maker of Zyban.

The FDA approved varenicline for smoking cessation in 2006 and approved bupropion, which also is indicated to treat depression and seasonal affective disorder, in 1997. After numerous postmarketing reports of increased incidents of psychiatric disorders occurring in smokers who used either drug, the agency added the boxed warning to each in 2009.

FDA officials advised clinicians to guard against changes in mental health status in smokers using these therapies. However, “the results of the trial confirm that the benefits of stopping smoking outweigh the risks of these medicines,” they noted.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Labels on two smoking cessation treatments will offer less severe warnings for mental health risk potentials in people with no history of psychiatric disorders, the Food and Drug Administration has announced.

Varenicline (Chantix) will no longer include a boxed warning for serious mental health side effects. The label for bupropion (Zyban) will still include a boxed warning, but language describing the potential for serious psychiatric adverse events will no longer appear within it. Updates will also be made to both labels to describe side effects on mood, behavior, or thinking.

In addition, varenicline’s label will reflect trial data showing its superior efficacy, compared with oral bupropion or nicotine patch. Although a patient medication guide will still be included with each prescription, the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy that prompted the guide will no longer be in place.

Earlier this year, two FDA advisory committees voted in favor of updating varenicline’s label, based on data from a randomized, controlled trial of more than 8,000 smokers, half of whom had a history of psychiatric disorders.

The trial showed no clinically significant difference in risk of adverse events across the smoking cessation treatments varenicline, bupropion, nicotine patch, or placebo study arms, although the risk was higher in the psychiatric cohorts in each.

Overall, 2% of those without a history of mental illness experienced neuropsychiatric adverse events, compared with between 5% and 7% of those with such a history.

The trial was cosponsored by Pfizer, maker of Chantix, and GlaxoSmithKline, maker of Zyban.

The FDA approved varenicline for smoking cessation in 2006 and approved bupropion, which also is indicated to treat depression and seasonal affective disorder, in 1997. After numerous postmarketing reports of increased incidents of psychiatric disorders occurring in smokers who used either drug, the agency added the boxed warning to each in 2009.

FDA officials advised clinicians to guard against changes in mental health status in smokers using these therapies. However, “the results of the trial confirm that the benefits of stopping smoking outweigh the risks of these medicines,” they noted.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Labels on two smoking cessation treatments will offer less severe warnings for mental health risk potentials in people with no history of psychiatric disorders, the Food and Drug Administration has announced.

Varenicline (Chantix) will no longer include a boxed warning for serious mental health side effects. The label for bupropion (Zyban) will still include a boxed warning, but language describing the potential for serious psychiatric adverse events will no longer appear within it. Updates will also be made to both labels to describe side effects on mood, behavior, or thinking.

In addition, varenicline’s label will reflect trial data showing its superior efficacy, compared with oral bupropion or nicotine patch. Although a patient medication guide will still be included with each prescription, the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy that prompted the guide will no longer be in place.

Earlier this year, two FDA advisory committees voted in favor of updating varenicline’s label, based on data from a randomized, controlled trial of more than 8,000 smokers, half of whom had a history of psychiatric disorders.

The trial showed no clinically significant difference in risk of adverse events across the smoking cessation treatments varenicline, bupropion, nicotine patch, or placebo study arms, although the risk was higher in the psychiatric cohorts in each.

Overall, 2% of those without a history of mental illness experienced neuropsychiatric adverse events, compared with between 5% and 7% of those with such a history.

The trial was cosponsored by Pfizer, maker of Chantix, and GlaxoSmithKline, maker of Zyban.

The FDA approved varenicline for smoking cessation in 2006 and approved bupropion, which also is indicated to treat depression and seasonal affective disorder, in 1997. After numerous postmarketing reports of increased incidents of psychiatric disorders occurring in smokers who used either drug, the agency added the boxed warning to each in 2009.

FDA officials advised clinicians to guard against changes in mental health status in smokers using these therapies. However, “the results of the trial confirm that the benefits of stopping smoking outweigh the risks of these medicines,” they noted.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Is better reporting to blame for the rise maternal mortality rates?

Better surveillance could be responsible for increased rates of U.S. maternal mortality, a sign that previous estimates were too low, according to a new study.

For more than 2 decades, rates of maternal deaths have increased significantly, climbing from 7.55 per 100,000 live births in 1993 to 9.88 in 1999, and rising again to 21.5 in 2014. This means the relative risk of maternal death between 2014 and 1993 was 2.84, while it was 2.17 between 2014 and 1999.

Although rising rates of obesity and other chronic conditions are often theorized as possible factors in the spiking maternal death rates K.S. Joseph, MD, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his colleagues suggest the more likely causes are improved maternal death surveillance and changes in how these deaths are coded.

This conclusion is based on a retrospective cohort analysis of maternal deaths and live births from 1993-2014 as recorded in the National Center for Health Statistics and the Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research files of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:91-100).

Surveillance and reporting changes have been implemented across the country over the last few decades. During the 1990s, some states began including a separate question regarding pregnancy on death certificates. Starting in 2003, pregnancy was added to the standardized checklist of causes of death on certificates used nationwide, although state-by-state implementation has varied. In addition, in 1999, ICD-10 codes for underlying causes of death were introduced, including O96 and O97 for late maternal deaths, O26.8 for specified pregnancy-related conditions, and O99 for other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere.

When Dr. Joseph and his colleagues excluded from their analysis maternal deaths coded according to the new ICD-10 codes primarily related to renal disease and other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere, the increase between 1999 and 2014 was erased, dropping the relative risk to 1.09 (95% CI, 0.94-1.27).

Adjustment for improvements in surveillance also wiped out the temporal increase in maternal mortality rates for a relative risk of 1.06 for 2013 compared to 1993 (95% CI, 0.90-1.25).

“Reports of temporal increases in maternal mortality rates in the United States have led to shock and soul-searching by clinicians,” the investigators wrote. “In fact, maternal deaths from conditions historically associated with high case fatality rates including preeclampsia, eclampsia, complications of labor and delivery, antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, and abortion either declined substantially or remained stable between 1999 and 2014.”

The investigators did not report having any potential conflicts of interest.

Better surveillance could be responsible for increased rates of U.S. maternal mortality, a sign that previous estimates were too low, according to a new study.

For more than 2 decades, rates of maternal deaths have increased significantly, climbing from 7.55 per 100,000 live births in 1993 to 9.88 in 1999, and rising again to 21.5 in 2014. This means the relative risk of maternal death between 2014 and 1993 was 2.84, while it was 2.17 between 2014 and 1999.

Although rising rates of obesity and other chronic conditions are often theorized as possible factors in the spiking maternal death rates K.S. Joseph, MD, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his colleagues suggest the more likely causes are improved maternal death surveillance and changes in how these deaths are coded.

This conclusion is based on a retrospective cohort analysis of maternal deaths and live births from 1993-2014 as recorded in the National Center for Health Statistics and the Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research files of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:91-100).

Surveillance and reporting changes have been implemented across the country over the last few decades. During the 1990s, some states began including a separate question regarding pregnancy on death certificates. Starting in 2003, pregnancy was added to the standardized checklist of causes of death on certificates used nationwide, although state-by-state implementation has varied. In addition, in 1999, ICD-10 codes for underlying causes of death were introduced, including O96 and O97 for late maternal deaths, O26.8 for specified pregnancy-related conditions, and O99 for other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere.

When Dr. Joseph and his colleagues excluded from their analysis maternal deaths coded according to the new ICD-10 codes primarily related to renal disease and other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere, the increase between 1999 and 2014 was erased, dropping the relative risk to 1.09 (95% CI, 0.94-1.27).

Adjustment for improvements in surveillance also wiped out the temporal increase in maternal mortality rates for a relative risk of 1.06 for 2013 compared to 1993 (95% CI, 0.90-1.25).

“Reports of temporal increases in maternal mortality rates in the United States have led to shock and soul-searching by clinicians,” the investigators wrote. “In fact, maternal deaths from conditions historically associated with high case fatality rates including preeclampsia, eclampsia, complications of labor and delivery, antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, and abortion either declined substantially or remained stable between 1999 and 2014.”

The investigators did not report having any potential conflicts of interest.

Better surveillance could be responsible for increased rates of U.S. maternal mortality, a sign that previous estimates were too low, according to a new study.

For more than 2 decades, rates of maternal deaths have increased significantly, climbing from 7.55 per 100,000 live births in 1993 to 9.88 in 1999, and rising again to 21.5 in 2014. This means the relative risk of maternal death between 2014 and 1993 was 2.84, while it was 2.17 between 2014 and 1999.

Although rising rates of obesity and other chronic conditions are often theorized as possible factors in the spiking maternal death rates K.S. Joseph, MD, PhD, of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and his colleagues suggest the more likely causes are improved maternal death surveillance and changes in how these deaths are coded.

This conclusion is based on a retrospective cohort analysis of maternal deaths and live births from 1993-2014 as recorded in the National Center for Health Statistics and the Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research files of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:91-100).