User login

FDA approves topical oxymetazoline for rosacea

A topical cream containing the vasoconstrictor oxymetazoline has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat symptoms of rosacea, its manufacturer announced.

Oxymetazoline hydrochloride cream 1%, which will be marketed as Rhofade by Allergan, is indicated for the treatment of “persistent facial erythema associated with rosacea in adults.” While nasal sprays containing a lower concentration of oxymetazoline HCl, an alpha1A-adrenoceptor agonist, have been used off label for a decade, this is the first time this ingredient has been harnessed to formulate an approved rosacea treatment.

Safety results from three pooled trials showed 2% of patients in the active treatment arms (489 people) had treatment-site dermatitis, and 1% had worsening of rosacea symptoms, pruritus, or pain. The vehicle cream groups (483 people) experienced similar rates of pruritus but negligible rates of other adverse effects, according to the prescribing information.

Brimonidine (Mirvaso) is another topical treatment approved by the FDA for treating rosacea, and its active ingredient is also an alpha-adrenergic agonist that works on the cutaneous microvasculature. However, there are differences in the two agents’ activity. Oxymetazoline acts on alpha1A receptors and brimonidine on alpha2 receptors. There have been reports of rebound erythema more severe than at baseline with brimonidine, and its manufacturer, Galderma, acknowledges the phenomenon in patient labeling.

When Allergan announced the FDA application for oxymetazoline in May 2016, it issued a press statement, describing oxymetazoline as a “sympathomimetic agonist that is selective for the alpha1A adrenoceptor or over other alpha1 adrenoceptors and nonselective for the alpha2 adrenoceptors.”In a 1-year open label trial of oxymetazoline (440 people), 3% of patients had worsening inflammatory lesions of rosacea, according to the prescribing information for oxymetazoline HCl 1%.

A topical cream containing the vasoconstrictor oxymetazoline has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat symptoms of rosacea, its manufacturer announced.

Oxymetazoline hydrochloride cream 1%, which will be marketed as Rhofade by Allergan, is indicated for the treatment of “persistent facial erythema associated with rosacea in adults.” While nasal sprays containing a lower concentration of oxymetazoline HCl, an alpha1A-adrenoceptor agonist, have been used off label for a decade, this is the first time this ingredient has been harnessed to formulate an approved rosacea treatment.

Safety results from three pooled trials showed 2% of patients in the active treatment arms (489 people) had treatment-site dermatitis, and 1% had worsening of rosacea symptoms, pruritus, or pain. The vehicle cream groups (483 people) experienced similar rates of pruritus but negligible rates of other adverse effects, according to the prescribing information.

Brimonidine (Mirvaso) is another topical treatment approved by the FDA for treating rosacea, and its active ingredient is also an alpha-adrenergic agonist that works on the cutaneous microvasculature. However, there are differences in the two agents’ activity. Oxymetazoline acts on alpha1A receptors and brimonidine on alpha2 receptors. There have been reports of rebound erythema more severe than at baseline with brimonidine, and its manufacturer, Galderma, acknowledges the phenomenon in patient labeling.

When Allergan announced the FDA application for oxymetazoline in May 2016, it issued a press statement, describing oxymetazoline as a “sympathomimetic agonist that is selective for the alpha1A adrenoceptor or over other alpha1 adrenoceptors and nonselective for the alpha2 adrenoceptors.”In a 1-year open label trial of oxymetazoline (440 people), 3% of patients had worsening inflammatory lesions of rosacea, according to the prescribing information for oxymetazoline HCl 1%.

A topical cream containing the vasoconstrictor oxymetazoline has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat symptoms of rosacea, its manufacturer announced.

Oxymetazoline hydrochloride cream 1%, which will be marketed as Rhofade by Allergan, is indicated for the treatment of “persistent facial erythema associated with rosacea in adults.” While nasal sprays containing a lower concentration of oxymetazoline HCl, an alpha1A-adrenoceptor agonist, have been used off label for a decade, this is the first time this ingredient has been harnessed to formulate an approved rosacea treatment.

Safety results from three pooled trials showed 2% of patients in the active treatment arms (489 people) had treatment-site dermatitis, and 1% had worsening of rosacea symptoms, pruritus, or pain. The vehicle cream groups (483 people) experienced similar rates of pruritus but negligible rates of other adverse effects, according to the prescribing information.

Brimonidine (Mirvaso) is another topical treatment approved by the FDA for treating rosacea, and its active ingredient is also an alpha-adrenergic agonist that works on the cutaneous microvasculature. However, there are differences in the two agents’ activity. Oxymetazoline acts on alpha1A receptors and brimonidine on alpha2 receptors. There have been reports of rebound erythema more severe than at baseline with brimonidine, and its manufacturer, Galderma, acknowledges the phenomenon in patient labeling.

When Allergan announced the FDA application for oxymetazoline in May 2016, it issued a press statement, describing oxymetazoline as a “sympathomimetic agonist that is selective for the alpha1A adrenoceptor or over other alpha1 adrenoceptors and nonselective for the alpha2 adrenoceptors.”In a 1-year open label trial of oxymetazoline (440 people), 3% of patients had worsening inflammatory lesions of rosacea, according to the prescribing information for oxymetazoline HCl 1%.

FDA approves ibrutinib for refractory MZL

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ibrutinib for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), the drug’s manufacturers report.

The approval marks the fifth indication for ibrutinib (Imbruvica) in just over 4 years, and ibrutinib is the first agent specifically approved for relapsed/refractory MZL, according to press releases issued by Janssen Biotech and Pharmacyclics, the two manufacturers that jointly developed and marketed the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

After receiving various fast-track, breakthrough therapy, priority review, and accelerated approval designations from the FDA, ibrutinib was previously approved to treat mantle cell lymphoma; refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL); CLL/SLL with 17p deletion; and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, another rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The MCL and MZL approvals are based on overall response rates, and full approval is likely to require additional confirmatory data.

The new indication is based on data from a phase II, open-label, single-arm manufacturer-sponsored study that showed a 46% overall response rate (95% confidence interval, 33.4-59.1) in a cohort of 63 MZL patients who had failed one or more prior therapies. Of these, 3.2% had a complete response and 42.9% had a partial response. The median duration of response was not reached (NR) (range, 16.7 months–NR), with median follow-up of 19.4 months. The median time to initial response was 4.5 months (2.3-16.4 months).

All three MZL subtypes were represented in the cohort, and ibrutinib appeared to be effective across subtypes. Thrombocytopenia, fatigue, anemia, diarrhea, bruising, and musculoskeletal pain were commonly reported adverse events.

hematologynews@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @HematologyNews1

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ibrutinib for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), the drug’s manufacturers report.

The approval marks the fifth indication for ibrutinib (Imbruvica) in just over 4 years, and ibrutinib is the first agent specifically approved for relapsed/refractory MZL, according to press releases issued by Janssen Biotech and Pharmacyclics, the two manufacturers that jointly developed and marketed the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

After receiving various fast-track, breakthrough therapy, priority review, and accelerated approval designations from the FDA, ibrutinib was previously approved to treat mantle cell lymphoma; refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL); CLL/SLL with 17p deletion; and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, another rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The MCL and MZL approvals are based on overall response rates, and full approval is likely to require additional confirmatory data.

The new indication is based on data from a phase II, open-label, single-arm manufacturer-sponsored study that showed a 46% overall response rate (95% confidence interval, 33.4-59.1) in a cohort of 63 MZL patients who had failed one or more prior therapies. Of these, 3.2% had a complete response and 42.9% had a partial response. The median duration of response was not reached (NR) (range, 16.7 months–NR), with median follow-up of 19.4 months. The median time to initial response was 4.5 months (2.3-16.4 months).

All three MZL subtypes were represented in the cohort, and ibrutinib appeared to be effective across subtypes. Thrombocytopenia, fatigue, anemia, diarrhea, bruising, and musculoskeletal pain were commonly reported adverse events.

hematologynews@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @HematologyNews1

The Food and Drug Administration has approved ibrutinib for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), the drug’s manufacturers report.

The approval marks the fifth indication for ibrutinib (Imbruvica) in just over 4 years, and ibrutinib is the first agent specifically approved for relapsed/refractory MZL, according to press releases issued by Janssen Biotech and Pharmacyclics, the two manufacturers that jointly developed and marketed the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

After receiving various fast-track, breakthrough therapy, priority review, and accelerated approval designations from the FDA, ibrutinib was previously approved to treat mantle cell lymphoma; refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL); CLL/SLL with 17p deletion; and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, another rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The MCL and MZL approvals are based on overall response rates, and full approval is likely to require additional confirmatory data.

The new indication is based on data from a phase II, open-label, single-arm manufacturer-sponsored study that showed a 46% overall response rate (95% confidence interval, 33.4-59.1) in a cohort of 63 MZL patients who had failed one or more prior therapies. Of these, 3.2% had a complete response and 42.9% had a partial response. The median duration of response was not reached (NR) (range, 16.7 months–NR), with median follow-up of 19.4 months. The median time to initial response was 4.5 months (2.3-16.4 months).

All three MZL subtypes were represented in the cohort, and ibrutinib appeared to be effective across subtypes. Thrombocytopenia, fatigue, anemia, diarrhea, bruising, and musculoskeletal pain were commonly reported adverse events.

hematologynews@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @HematologyNews1

Prominent clinical guidelines fall short of conflict of interest standards

Two recent clinical practice guidelines – one for cholesterol management and another for treatment of chronic hepatitis C – did not meet the Institute of Medicine’s standards for limiting commercial conflicts of interest, according to results of a new analysis.

In research published online Jan. 17, Akilah A. Jefferson, MD, and Steven D. Pearson, MD, both of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., re-examined conflict of interest disclosures for the 2013 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association cholesterol management guideline, as well as for the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and Infectious Diseases Society of America’s joint 2014 guideline related to novel drug treatments for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

The IOM standards for conflicts of interest in guidelines, introduced in 2011, require that less than half the members of any guideline writing committee have a commercial conflict, which can include consultancies, board memberships, and stock in manufacturers of devices or treatments. Guideline writing committee chairs and cochairs should have no commercial conflicts of interest, according to the IOM.

For the cholesterol guidelines, the investigators found that while the committee members fell below the threshold with only 44% reporting commercial conflicts, one writing chair had multiple conflicts until about 1 year before guideline development began, an analysis of concurrent publications suggested. For the HCV guidelines, meanwhile, 72% of the committee members reported commercial conflicts, along with four out of six committee cochairs. An analysis of concurrent publications revealed incomplete disclosure of conflicts among authors of both guidelines (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8439).

“Management of levels of commercial [conflict of interest] among guideline committees remains an important problem 5 years after the IOM standards were published,” the investigators wrote. They recommended “broader and more explicit adoption” of the IOM’s framework for conflict of interest.

The study notes that the HCV guideline met all nine of the additional IOM guideline development and evidence standards, while the cholesterol guideline met five of those standards.

The study was funded by an NIH grant. Dr. Pearson reported receiving research funding from foundations and membership dues paid by insurance and pharmaceutical companies. No other disclosures were reported.

Two recent clinical practice guidelines – one for cholesterol management and another for treatment of chronic hepatitis C – did not meet the Institute of Medicine’s standards for limiting commercial conflicts of interest, according to results of a new analysis.

In research published online Jan. 17, Akilah A. Jefferson, MD, and Steven D. Pearson, MD, both of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., re-examined conflict of interest disclosures for the 2013 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association cholesterol management guideline, as well as for the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and Infectious Diseases Society of America’s joint 2014 guideline related to novel drug treatments for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

The IOM standards for conflicts of interest in guidelines, introduced in 2011, require that less than half the members of any guideline writing committee have a commercial conflict, which can include consultancies, board memberships, and stock in manufacturers of devices or treatments. Guideline writing committee chairs and cochairs should have no commercial conflicts of interest, according to the IOM.

For the cholesterol guidelines, the investigators found that while the committee members fell below the threshold with only 44% reporting commercial conflicts, one writing chair had multiple conflicts until about 1 year before guideline development began, an analysis of concurrent publications suggested. For the HCV guidelines, meanwhile, 72% of the committee members reported commercial conflicts, along with four out of six committee cochairs. An analysis of concurrent publications revealed incomplete disclosure of conflicts among authors of both guidelines (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8439).

“Management of levels of commercial [conflict of interest] among guideline committees remains an important problem 5 years after the IOM standards were published,” the investigators wrote. They recommended “broader and more explicit adoption” of the IOM’s framework for conflict of interest.

The study notes that the HCV guideline met all nine of the additional IOM guideline development and evidence standards, while the cholesterol guideline met five of those standards.

The study was funded by an NIH grant. Dr. Pearson reported receiving research funding from foundations and membership dues paid by insurance and pharmaceutical companies. No other disclosures were reported.

Two recent clinical practice guidelines – one for cholesterol management and another for treatment of chronic hepatitis C – did not meet the Institute of Medicine’s standards for limiting commercial conflicts of interest, according to results of a new analysis.

In research published online Jan. 17, Akilah A. Jefferson, MD, and Steven D. Pearson, MD, both of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., re-examined conflict of interest disclosures for the 2013 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association cholesterol management guideline, as well as for the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and Infectious Diseases Society of America’s joint 2014 guideline related to novel drug treatments for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

The IOM standards for conflicts of interest in guidelines, introduced in 2011, require that less than half the members of any guideline writing committee have a commercial conflict, which can include consultancies, board memberships, and stock in manufacturers of devices or treatments. Guideline writing committee chairs and cochairs should have no commercial conflicts of interest, according to the IOM.

For the cholesterol guidelines, the investigators found that while the committee members fell below the threshold with only 44% reporting commercial conflicts, one writing chair had multiple conflicts until about 1 year before guideline development began, an analysis of concurrent publications suggested. For the HCV guidelines, meanwhile, 72% of the committee members reported commercial conflicts, along with four out of six committee cochairs. An analysis of concurrent publications revealed incomplete disclosure of conflicts among authors of both guidelines (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8439).

“Management of levels of commercial [conflict of interest] among guideline committees remains an important problem 5 years after the IOM standards were published,” the investigators wrote. They recommended “broader and more explicit adoption” of the IOM’s framework for conflict of interest.

The study notes that the HCV guideline met all nine of the additional IOM guideline development and evidence standards, while the cholesterol guideline met five of those standards.

The study was funded by an NIH grant. Dr. Pearson reported receiving research funding from foundations and membership dues paid by insurance and pharmaceutical companies. No other disclosures were reported.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In total, 72% of members of the hepatitis C virus guideline committee disclosed conflicts of interest, while 44% of members of the cholesterol guideline committee reported commercial conflicts.

Data source: A retrospective review of the ACA/AHA’s cholesterol guideline and the AASLD/IDSA’s hepatitis C virus guideline.

Disclosures: The research was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Pearson reported research grants from foundations and membership dues paid by insurance and pharmaceutical companies. No other disclosures were reported.

Two-thirds of patient advocacy groups receive industry funding

About two-thirds of patient advocacy organizations report receiving funds from for-profit firms, including pharmaceutical, device and biotechnology manufacturers, according to new survey results.

The study, published online Jan. 17 in JAMA Internal Medicine, sought responses from a randomly chosen sample of 439 executives at patient advocacy organizations (PAOs), of whom 66% (n = 289) responded. The median annual revenue for the groups surveyed was nearly $300,000, and 67% (n = 165) reported receiving at least some industry funding. Of those, 12% reported that more than half their annual funding comes from industry sources.

A total of 22 PAO leaders surveyed (8%) reported that they perceived pressure to conform their organizational interests to those of corporate donors (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8443).

The vast majority of respondents (82%) said they found conflicts of interest to be relevant to PAOs, and most reported having a written policy on conflicts. More than half said they viewed their own organizations’ conflict of interest policies as sound.

The findings warrant a broad re-examination of PAO conflict-of-interest policies and disclosures, and a detailed examination of the specific ways in which PAOs are influenced or pressured, wrote Susannah L. Rose, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and her colleagues.

PAOs do not routinely and publicly disclose all their sources of funding on websites, tax returns, or annual reports, and there are media investigations into some groups “regarding their ties to industry and the integrity of their activities,” the investigators wrote.

Dr. Rose and her colleagues recommended that PAOs disclose detailed information about industry funding on their websites and on Open Payments, a government website. The researchers acknowledged that their study relied on self-reported data, and though it was designed to obscure the identity of respondents and their organizations, the possibility of response bias exists.

Harvard University’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics funded the study. One coauthor, Steven Joffe, MD, MPH, disclosed past funding from Genzyme Sanofi. No other conflicts were reported.

Industry funding strengthens and extends the much-needed patient voice in health care, but at what cost? During the EpiPen scandal, the manufacturer-sponsored advocacy groups were largely silent about price gouging. Recently, a drug company–funded “patient advocacy” campaign called “Even the Score” helped win regulatory approval for the thrice rejected controversial female sex drug flibanserin.

Just as the industry funding of clinical trials has been associated with more favorable findings, patient groups also face risks of bias when accepting money from companies seeking to expand markets for their new tests and treatments.

This new work demonstrates an urgent need for patient advocacy organizations to explicitly focus much more on representing the interests of patients and citizens, rather than serving – inadvertently or otherwise – the interests of their industry sponsors. In the meantime, we need much greater transparency about industry funding, including prominently displayed disclosures of dollar amounts and proportions of total funding on group websites, as well as addition of patient advocacy groups to the Open Payments program established by the Sunshine Act, which would mean mandatory disclosure of funding by sponsors.

Ray Moynihan, PhD, and Lisa Bero, PhD, are at the University of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Their comments are adapted from an editorial. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9179 ).

Industry funding strengthens and extends the much-needed patient voice in health care, but at what cost? During the EpiPen scandal, the manufacturer-sponsored advocacy groups were largely silent about price gouging. Recently, a drug company–funded “patient advocacy” campaign called “Even the Score” helped win regulatory approval for the thrice rejected controversial female sex drug flibanserin.

Just as the industry funding of clinical trials has been associated with more favorable findings, patient groups also face risks of bias when accepting money from companies seeking to expand markets for their new tests and treatments.

This new work demonstrates an urgent need for patient advocacy organizations to explicitly focus much more on representing the interests of patients and citizens, rather than serving – inadvertently or otherwise – the interests of their industry sponsors. In the meantime, we need much greater transparency about industry funding, including prominently displayed disclosures of dollar amounts and proportions of total funding on group websites, as well as addition of patient advocacy groups to the Open Payments program established by the Sunshine Act, which would mean mandatory disclosure of funding by sponsors.

Ray Moynihan, PhD, and Lisa Bero, PhD, are at the University of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Their comments are adapted from an editorial. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9179 ).

Industry funding strengthens and extends the much-needed patient voice in health care, but at what cost? During the EpiPen scandal, the manufacturer-sponsored advocacy groups were largely silent about price gouging. Recently, a drug company–funded “patient advocacy” campaign called “Even the Score” helped win regulatory approval for the thrice rejected controversial female sex drug flibanserin.

Just as the industry funding of clinical trials has been associated with more favorable findings, patient groups also face risks of bias when accepting money from companies seeking to expand markets for their new tests and treatments.

This new work demonstrates an urgent need for patient advocacy organizations to explicitly focus much more on representing the interests of patients and citizens, rather than serving – inadvertently or otherwise – the interests of their industry sponsors. In the meantime, we need much greater transparency about industry funding, including prominently displayed disclosures of dollar amounts and proportions of total funding on group websites, as well as addition of patient advocacy groups to the Open Payments program established by the Sunshine Act, which would mean mandatory disclosure of funding by sponsors.

Ray Moynihan, PhD, and Lisa Bero, PhD, are at the University of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Their comments are adapted from an editorial. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures. (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9179 ).

About two-thirds of patient advocacy organizations report receiving funds from for-profit firms, including pharmaceutical, device and biotechnology manufacturers, according to new survey results.

The study, published online Jan. 17 in JAMA Internal Medicine, sought responses from a randomly chosen sample of 439 executives at patient advocacy organizations (PAOs), of whom 66% (n = 289) responded. The median annual revenue for the groups surveyed was nearly $300,000, and 67% (n = 165) reported receiving at least some industry funding. Of those, 12% reported that more than half their annual funding comes from industry sources.

A total of 22 PAO leaders surveyed (8%) reported that they perceived pressure to conform their organizational interests to those of corporate donors (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8443).

The vast majority of respondents (82%) said they found conflicts of interest to be relevant to PAOs, and most reported having a written policy on conflicts. More than half said they viewed their own organizations’ conflict of interest policies as sound.

The findings warrant a broad re-examination of PAO conflict-of-interest policies and disclosures, and a detailed examination of the specific ways in which PAOs are influenced or pressured, wrote Susannah L. Rose, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and her colleagues.

PAOs do not routinely and publicly disclose all their sources of funding on websites, tax returns, or annual reports, and there are media investigations into some groups “regarding their ties to industry and the integrity of their activities,” the investigators wrote.

Dr. Rose and her colleagues recommended that PAOs disclose detailed information about industry funding on their websites and on Open Payments, a government website. The researchers acknowledged that their study relied on self-reported data, and though it was designed to obscure the identity of respondents and their organizations, the possibility of response bias exists.

Harvard University’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics funded the study. One coauthor, Steven Joffe, MD, MPH, disclosed past funding from Genzyme Sanofi. No other conflicts were reported.

About two-thirds of patient advocacy organizations report receiving funds from for-profit firms, including pharmaceutical, device and biotechnology manufacturers, according to new survey results.

The study, published online Jan. 17 in JAMA Internal Medicine, sought responses from a randomly chosen sample of 439 executives at patient advocacy organizations (PAOs), of whom 66% (n = 289) responded. The median annual revenue for the groups surveyed was nearly $300,000, and 67% (n = 165) reported receiving at least some industry funding. Of those, 12% reported that more than half their annual funding comes from industry sources.

A total of 22 PAO leaders surveyed (8%) reported that they perceived pressure to conform their organizational interests to those of corporate donors (JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan 17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8443).

The vast majority of respondents (82%) said they found conflicts of interest to be relevant to PAOs, and most reported having a written policy on conflicts. More than half said they viewed their own organizations’ conflict of interest policies as sound.

The findings warrant a broad re-examination of PAO conflict-of-interest policies and disclosures, and a detailed examination of the specific ways in which PAOs are influenced or pressured, wrote Susannah L. Rose, PhD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and her colleagues.

PAOs do not routinely and publicly disclose all their sources of funding on websites, tax returns, or annual reports, and there are media investigations into some groups “regarding their ties to industry and the integrity of their activities,” the investigators wrote.

Dr. Rose and her colleagues recommended that PAOs disclose detailed information about industry funding on their websites and on Open Payments, a government website. The researchers acknowledged that their study relied on self-reported data, and though it was designed to obscure the identity of respondents and their organizations, the possibility of response bias exists.

Harvard University’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics funded the study. One coauthor, Steven Joffe, MD, MPH, disclosed past funding from Genzyme Sanofi. No other conflicts were reported.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 67% of PAOs receive industry support, with 12% reporting funds comprising more than half their yearly funding.

Data source: A survey study sent to executives of 439 PAOs chosen at random; the response rate was 66%.

Disclosures: An ethics center at Harvard University sponsored the study; one coauthor reported prior funding from Genzyme Sanofi.

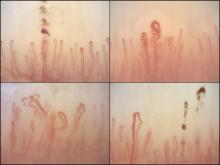

Nailfold analysis can predict cardiopulmonary complications in systemic sclerosis

Nailfold videocapillaroscopy can help to predict which patients with systemic sclerosis may develop serious cardiopulmonary complications, according to findings from a Dutch cross-sectional study.

While individual autoantibodies seen in systemic sclerosis (SSc) are known to be associated with greater or lesser risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, in this study nailfold vascularization patterns independently predicted pulmonary artery hypertension or interstitial lung disease.

All patients in the study had NVC pattern data as well as anti-extractable nuclear antigen (anti-ENA) antibodies. The mean age of the patients was 54 years; 82% were female, and median disease duration was 3 years. Just over half the cohort had interstitial lung disease, and 16% had pulmonary artery hypertension.

Among the anti-ENA autoantibody subtypes, anti-ACA was seen in 37% of patients, anti-Scl-70 in 24%, anti-RNP in 9%, and anti-RNAPIII in 5%; other subtypes were rarer. SSc-specific NVC patterns were seen in 88% of patients, with 10% of the cohort showing an early (less severe microangiopathy) pattern, 42% an active pattern, and 36% a late pattern.

One of the study’s objectives was to determine whether one or more mechanisms was responsible for both autoantibody production and the microangiopathy seen in SSc.

If a joint mechanism is implicated, “more severe NVC patterns would be determined in patients with autoantibodies (such as anti-Scl-70 and anti-RNAPIII) that are associated with more severe disease,” wrote Dr. Markusse and her colleagues. “On the other hand, if specific autoantibodies and stage of microangiopathy reflect different processes in the disease, a combination of autoantibody status and NVC could be helpful for identifying patients at highest risk for cardiopulmonary involvement.”

The investigators reported finding a similar distribution of NVC abnormalities across the major SSc autoantibody subtypes (except for anti–RNP-positive patients), suggesting that combinations of the two variables would be most predictive of cardiopulmonary involvement. More severe NVC patterns were associated with a higher risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, independent of the presence of a specific autoantibody.

Notably, the researchers wrote, “prevalence of ILD [interstitial lung disease] is generally lower among ACA-positive patients. According to our data, even among ACA-positive patients there was a trend for more ILD being associated with more severe NVC patterns (OR = 1.33).”

A similar pattern was seen for pulmonary artery hypertension. “Based on anti-RNP and anti-RNAPIII positivity, patients did not have an increased risk of a [systolic pulmonary artery pressure] greater than 35 mm Hg; however, with a severe NVC pattern, this risk was significantly increased (OR = 2.33).”

The investigators cautioned that their findings should be confirmed in larger cohorts. The study by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues was conducted without outside funding, though manufacturers donated diagnostic antibody tests. One of the 11 study coauthors disclosed receiving financial support from Actelion.

Systemic sclerosis is a profoundly heterogeneous disorder, with the overall prevalence of major organ-specific manifestations, such as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), broadly adhering to a 15% rule. As such, the majority of patients with SSc will not develop any given organ-specific complication. The major challenge for clinicians during the early stages of the disease is predicting the future occurrence of potentially life-threatening organ-specific manifestations, such as PAH.

The complementary association of nailfold videocapillaroscopy changes and autoantibody profile in predicting cardiopulmonary involvement reported by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues is novel, but otherwise supports the findings of previous cross-sectional studies identifying associations between advanced NVC changes and SSc complications, such as digital ischemic lesions and PAH. These studies provide intriguing insight into the relationship between the evolution of microangiopathy and the emergence of organ-specific manifestations of SSc, but also represent a shift in focus from the diagnostic to the prognostic utility of NVC in SSc.

There is potential clinical utility in these observations that has yet to be unlocked fully; particularly should the predictive value and timing of NVC progression be further characterized in longitudinal studies better defining the natural history of SSc organ-specific manifestations. If evolving NVC changes (in high-risk serological subgroups) are shown to pre-date the emergence of overt organ-specific manifestations of SSc, then we might be provided with a window of opportunity for escalation of therapy with treatments targeting endothelial function (such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors and/or endothelin receptor antagonists) and/or possible immunomodulatory approaches. This could potentially usher in a new era of preventive disease-modifying therapeutic intervention in SSc.

John D. Pauling, MD, PhD, is a consultant rheumatologist at the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath, England, and Visiting Senior Lecturer in the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath. His commentary is derived from an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Markusse and her associates (Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2016 Dec 30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew461). He disclosed having received grants and consultancy income from Actelion.

Systemic sclerosis is a profoundly heterogeneous disorder, with the overall prevalence of major organ-specific manifestations, such as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), broadly adhering to a 15% rule. As such, the majority of patients with SSc will not develop any given organ-specific complication. The major challenge for clinicians during the early stages of the disease is predicting the future occurrence of potentially life-threatening organ-specific manifestations, such as PAH.

The complementary association of nailfold videocapillaroscopy changes and autoantibody profile in predicting cardiopulmonary involvement reported by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues is novel, but otherwise supports the findings of previous cross-sectional studies identifying associations between advanced NVC changes and SSc complications, such as digital ischemic lesions and PAH. These studies provide intriguing insight into the relationship between the evolution of microangiopathy and the emergence of organ-specific manifestations of SSc, but also represent a shift in focus from the diagnostic to the prognostic utility of NVC in SSc.

There is potential clinical utility in these observations that has yet to be unlocked fully; particularly should the predictive value and timing of NVC progression be further characterized in longitudinal studies better defining the natural history of SSc organ-specific manifestations. If evolving NVC changes (in high-risk serological subgroups) are shown to pre-date the emergence of overt organ-specific manifestations of SSc, then we might be provided with a window of opportunity for escalation of therapy with treatments targeting endothelial function (such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors and/or endothelin receptor antagonists) and/or possible immunomodulatory approaches. This could potentially usher in a new era of preventive disease-modifying therapeutic intervention in SSc.

John D. Pauling, MD, PhD, is a consultant rheumatologist at the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath, England, and Visiting Senior Lecturer in the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath. His commentary is derived from an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Markusse and her associates (Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2016 Dec 30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew461). He disclosed having received grants and consultancy income from Actelion.

Systemic sclerosis is a profoundly heterogeneous disorder, with the overall prevalence of major organ-specific manifestations, such as pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), broadly adhering to a 15% rule. As such, the majority of patients with SSc will not develop any given organ-specific complication. The major challenge for clinicians during the early stages of the disease is predicting the future occurrence of potentially life-threatening organ-specific manifestations, such as PAH.

The complementary association of nailfold videocapillaroscopy changes and autoantibody profile in predicting cardiopulmonary involvement reported by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues is novel, but otherwise supports the findings of previous cross-sectional studies identifying associations between advanced NVC changes and SSc complications, such as digital ischemic lesions and PAH. These studies provide intriguing insight into the relationship between the evolution of microangiopathy and the emergence of organ-specific manifestations of SSc, but also represent a shift in focus from the diagnostic to the prognostic utility of NVC in SSc.

There is potential clinical utility in these observations that has yet to be unlocked fully; particularly should the predictive value and timing of NVC progression be further characterized in longitudinal studies better defining the natural history of SSc organ-specific manifestations. If evolving NVC changes (in high-risk serological subgroups) are shown to pre-date the emergence of overt organ-specific manifestations of SSc, then we might be provided with a window of opportunity for escalation of therapy with treatments targeting endothelial function (such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors and/or endothelin receptor antagonists) and/or possible immunomodulatory approaches. This could potentially usher in a new era of preventive disease-modifying therapeutic intervention in SSc.

John D. Pauling, MD, PhD, is a consultant rheumatologist at the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath, England, and Visiting Senior Lecturer in the department of pharmacy and pharmacology at the University of Bath. His commentary is derived from an editorial accompanying the study by Dr. Markusse and her associates (Rheumatology [Oxford]. 2016 Dec 30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew461). He disclosed having received grants and consultancy income from Actelion.

Nailfold videocapillaroscopy can help to predict which patients with systemic sclerosis may develop serious cardiopulmonary complications, according to findings from a Dutch cross-sectional study.

While individual autoantibodies seen in systemic sclerosis (SSc) are known to be associated with greater or lesser risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, in this study nailfold vascularization patterns independently predicted pulmonary artery hypertension or interstitial lung disease.

All patients in the study had NVC pattern data as well as anti-extractable nuclear antigen (anti-ENA) antibodies. The mean age of the patients was 54 years; 82% were female, and median disease duration was 3 years. Just over half the cohort had interstitial lung disease, and 16% had pulmonary artery hypertension.

Among the anti-ENA autoantibody subtypes, anti-ACA was seen in 37% of patients, anti-Scl-70 in 24%, anti-RNP in 9%, and anti-RNAPIII in 5%; other subtypes were rarer. SSc-specific NVC patterns were seen in 88% of patients, with 10% of the cohort showing an early (less severe microangiopathy) pattern, 42% an active pattern, and 36% a late pattern.

One of the study’s objectives was to determine whether one or more mechanisms was responsible for both autoantibody production and the microangiopathy seen in SSc.

If a joint mechanism is implicated, “more severe NVC patterns would be determined in patients with autoantibodies (such as anti-Scl-70 and anti-RNAPIII) that are associated with more severe disease,” wrote Dr. Markusse and her colleagues. “On the other hand, if specific autoantibodies and stage of microangiopathy reflect different processes in the disease, a combination of autoantibody status and NVC could be helpful for identifying patients at highest risk for cardiopulmonary involvement.”

The investigators reported finding a similar distribution of NVC abnormalities across the major SSc autoantibody subtypes (except for anti–RNP-positive patients), suggesting that combinations of the two variables would be most predictive of cardiopulmonary involvement. More severe NVC patterns were associated with a higher risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, independent of the presence of a specific autoantibody.

Notably, the researchers wrote, “prevalence of ILD [interstitial lung disease] is generally lower among ACA-positive patients. According to our data, even among ACA-positive patients there was a trend for more ILD being associated with more severe NVC patterns (OR = 1.33).”

A similar pattern was seen for pulmonary artery hypertension. “Based on anti-RNP and anti-RNAPIII positivity, patients did not have an increased risk of a [systolic pulmonary artery pressure] greater than 35 mm Hg; however, with a severe NVC pattern, this risk was significantly increased (OR = 2.33).”

The investigators cautioned that their findings should be confirmed in larger cohorts. The study by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues was conducted without outside funding, though manufacturers donated diagnostic antibody tests. One of the 11 study coauthors disclosed receiving financial support from Actelion.

Nailfold videocapillaroscopy can help to predict which patients with systemic sclerosis may develop serious cardiopulmonary complications, according to findings from a Dutch cross-sectional study.

While individual autoantibodies seen in systemic sclerosis (SSc) are known to be associated with greater or lesser risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, in this study nailfold vascularization patterns independently predicted pulmonary artery hypertension or interstitial lung disease.

All patients in the study had NVC pattern data as well as anti-extractable nuclear antigen (anti-ENA) antibodies. The mean age of the patients was 54 years; 82% were female, and median disease duration was 3 years. Just over half the cohort had interstitial lung disease, and 16% had pulmonary artery hypertension.

Among the anti-ENA autoantibody subtypes, anti-ACA was seen in 37% of patients, anti-Scl-70 in 24%, anti-RNP in 9%, and anti-RNAPIII in 5%; other subtypes were rarer. SSc-specific NVC patterns were seen in 88% of patients, with 10% of the cohort showing an early (less severe microangiopathy) pattern, 42% an active pattern, and 36% a late pattern.

One of the study’s objectives was to determine whether one or more mechanisms was responsible for both autoantibody production and the microangiopathy seen in SSc.

If a joint mechanism is implicated, “more severe NVC patterns would be determined in patients with autoantibodies (such as anti-Scl-70 and anti-RNAPIII) that are associated with more severe disease,” wrote Dr. Markusse and her colleagues. “On the other hand, if specific autoantibodies and stage of microangiopathy reflect different processes in the disease, a combination of autoantibody status and NVC could be helpful for identifying patients at highest risk for cardiopulmonary involvement.”

The investigators reported finding a similar distribution of NVC abnormalities across the major SSc autoantibody subtypes (except for anti–RNP-positive patients), suggesting that combinations of the two variables would be most predictive of cardiopulmonary involvement. More severe NVC patterns were associated with a higher risk of cardiopulmonary involvement, independent of the presence of a specific autoantibody.

Notably, the researchers wrote, “prevalence of ILD [interstitial lung disease] is generally lower among ACA-positive patients. According to our data, even among ACA-positive patients there was a trend for more ILD being associated with more severe NVC patterns (OR = 1.33).”

A similar pattern was seen for pulmonary artery hypertension. “Based on anti-RNP and anti-RNAPIII positivity, patients did not have an increased risk of a [systolic pulmonary artery pressure] greater than 35 mm Hg; however, with a severe NVC pattern, this risk was significantly increased (OR = 2.33).”

The investigators cautioned that their findings should be confirmed in larger cohorts. The study by Dr. Markusse and her colleagues was conducted without outside funding, though manufacturers donated diagnostic antibody tests. One of the 11 study coauthors disclosed receiving financial support from Actelion.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Across the major autoantibody subtypes seen in an SSc cohort, NVC pattern showed a stable association with presence of interstitial lung disease (OR, 1.3-1.4) or elevated systolic pulmonary artery pressure (OR, 2.2-2.4).

Data source: A cross-section of 287 patients in a Dutch SSc cohort.

Disclosures: The study was conducted without outside funding, though manufacturers donated diagnostic antibody tests. One of the 11 study coauthors disclosed receiving financial support from Actelion.

Enthesitis seen in 35% of PsA patients

About one-third of people with psoriatic arthritis have clinical enthesitis, according to results from a prospective cohort study of more than 800 patients.

Enthesitis, or soreness and inflammation at sites where soft tissue attaches to bone, is considered to be common in psoriatic arthritis (PsA), but its true prevalence has been difficult to define in this population, according to a group of researchers led by Ari Polachek, MD, of the University of Toronto.

Previous studies attempting to quantify enthesitis prevalence in PsA populations have found it to be as low as 8% to more than 50% of patients affected, Dr. Polachek and his colleagues noted, but such disparities can likely be attributed to the use of different enthesitis measures. To define enthesitis in the current study, the investigators used the SPondyloArthritis Research Consortium Canada (SPARCC) enthesitis index, which they called “valid and reliable, particularly for patients with PsA.”

Dr. Polachek and his colleagues detected enthesitis in 281 (35%) of 803 patents who had been recruited during 2008-2014 at a single clinic dedicated to PsA. The enthesitis diagnoses were established for at least one site on an initial visit (n = 128) or during a mean 3 years’ follow-up (n = 192).

The investigators reported that the annual incidence of enthesitis in this population was 0.9% (Arthritis Care Res. 2016 Dec 20. doi: 10.1002/acr.23174). About half of the patients in the cohort had only one site affected, and one-third had two sites affected. The most common of these sites were the Achilles tendon, plantar fascia, and the lateral epicondyle, Dr. Polachek and colleagues reported. They also found several factors associated with enthesitis: higher inflamed joint count (odds ratio, 1.06; P = .0002), less clinical damage (OR, 0.9; P = .04), more pain (OR, 1.15; P = .01), and presence of tenosynovitis (OR, 5.3; P less than .0001) or dactylitis (OR, 2.5; P = .02).

Significant risk factors for enthesitis included higher body mass index (hazard ratio, 1.04; P = .02), more actively inflamed joints (HR, 1.04; P = .0004), and younger age (HR, 0.98; P = .02). Among the patients in the cohort, 57% were male, the mean age was 50.8 years, and mean PsA disease duration was 12.3 years. Median time to resolution of enthesitis was 7.5 months, with 70% of patients improving without changes to their treatment.

The University of Toronto PsA research program receives funding from Krembil Foundation. Dr. Polachek disclosed grant funding from Janssen Canada. No other authors reported conflicts of interest.

About one-third of people with psoriatic arthritis have clinical enthesitis, according to results from a prospective cohort study of more than 800 patients.

Enthesitis, or soreness and inflammation at sites where soft tissue attaches to bone, is considered to be common in psoriatic arthritis (PsA), but its true prevalence has been difficult to define in this population, according to a group of researchers led by Ari Polachek, MD, of the University of Toronto.

Previous studies attempting to quantify enthesitis prevalence in PsA populations have found it to be as low as 8% to more than 50% of patients affected, Dr. Polachek and his colleagues noted, but such disparities can likely be attributed to the use of different enthesitis measures. To define enthesitis in the current study, the investigators used the SPondyloArthritis Research Consortium Canada (SPARCC) enthesitis index, which they called “valid and reliable, particularly for patients with PsA.”

Dr. Polachek and his colleagues detected enthesitis in 281 (35%) of 803 patents who had been recruited during 2008-2014 at a single clinic dedicated to PsA. The enthesitis diagnoses were established for at least one site on an initial visit (n = 128) or during a mean 3 years’ follow-up (n = 192).

The investigators reported that the annual incidence of enthesitis in this population was 0.9% (Arthritis Care Res. 2016 Dec 20. doi: 10.1002/acr.23174). About half of the patients in the cohort had only one site affected, and one-third had two sites affected. The most common of these sites were the Achilles tendon, plantar fascia, and the lateral epicondyle, Dr. Polachek and colleagues reported. They also found several factors associated with enthesitis: higher inflamed joint count (odds ratio, 1.06; P = .0002), less clinical damage (OR, 0.9; P = .04), more pain (OR, 1.15; P = .01), and presence of tenosynovitis (OR, 5.3; P less than .0001) or dactylitis (OR, 2.5; P = .02).

Significant risk factors for enthesitis included higher body mass index (hazard ratio, 1.04; P = .02), more actively inflamed joints (HR, 1.04; P = .0004), and younger age (HR, 0.98; P = .02). Among the patients in the cohort, 57% were male, the mean age was 50.8 years, and mean PsA disease duration was 12.3 years. Median time to resolution of enthesitis was 7.5 months, with 70% of patients improving without changes to their treatment.

The University of Toronto PsA research program receives funding from Krembil Foundation. Dr. Polachek disclosed grant funding from Janssen Canada. No other authors reported conflicts of interest.

About one-third of people with psoriatic arthritis have clinical enthesitis, according to results from a prospective cohort study of more than 800 patients.

Enthesitis, or soreness and inflammation at sites where soft tissue attaches to bone, is considered to be common in psoriatic arthritis (PsA), but its true prevalence has been difficult to define in this population, according to a group of researchers led by Ari Polachek, MD, of the University of Toronto.

Previous studies attempting to quantify enthesitis prevalence in PsA populations have found it to be as low as 8% to more than 50% of patients affected, Dr. Polachek and his colleagues noted, but such disparities can likely be attributed to the use of different enthesitis measures. To define enthesitis in the current study, the investigators used the SPondyloArthritis Research Consortium Canada (SPARCC) enthesitis index, which they called “valid and reliable, particularly for patients with PsA.”

Dr. Polachek and his colleagues detected enthesitis in 281 (35%) of 803 patents who had been recruited during 2008-2014 at a single clinic dedicated to PsA. The enthesitis diagnoses were established for at least one site on an initial visit (n = 128) or during a mean 3 years’ follow-up (n = 192).

The investigators reported that the annual incidence of enthesitis in this population was 0.9% (Arthritis Care Res. 2016 Dec 20. doi: 10.1002/acr.23174). About half of the patients in the cohort had only one site affected, and one-third had two sites affected. The most common of these sites were the Achilles tendon, plantar fascia, and the lateral epicondyle, Dr. Polachek and colleagues reported. They also found several factors associated with enthesitis: higher inflamed joint count (odds ratio, 1.06; P = .0002), less clinical damage (OR, 0.9; P = .04), more pain (OR, 1.15; P = .01), and presence of tenosynovitis (OR, 5.3; P less than .0001) or dactylitis (OR, 2.5; P = .02).

Significant risk factors for enthesitis included higher body mass index (hazard ratio, 1.04; P = .02), more actively inflamed joints (HR, 1.04; P = .0004), and younger age (HR, 0.98; P = .02). Among the patients in the cohort, 57% were male, the mean age was 50.8 years, and mean PsA disease duration was 12.3 years. Median time to resolution of enthesitis was 7.5 months, with 70% of patients improving without changes to their treatment.

The University of Toronto PsA research program receives funding from Krembil Foundation. Dr. Polachek disclosed grant funding from Janssen Canada. No other authors reported conflicts of interest.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Prevalence of enthesitis was 35% in a cohort of PsA patients; significant risk factors included high BMI, higher disease activity, and younger age.

Data source: About 800 PsA patients treated at a university clinic during 2008-2014; mean follow-up was 3.3 years.

Disclosures: The Krembil Foundation indirectly supported the study, whose lead author disclosed receipt of a grant from a pharmaceutical manufacturer.

Pain after hernia repair shows improvement at 6 months

Patients who have undergone open ventral abdominal hernia repair see significant improvements in some self-reported pain measures at 6 or more months after surgery, according to results from a new study.

The investigators, led by Eugene Park, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, suggested that the timing of the improvements may have to do with the mesh used in the surgeries.

For their research, published in the January issue of The American Journal of Surgery (2017;213:58-63), Dr. Park and his colleagues recruited 77 patients scheduled for midline incisional ventral hernia repair between 2010 and 2013 (mean age, 54 years; 45% female), who completed detailed pain surveys before surgery and during all postoperative visits; 38 patients completed surveys at least 6 months after surgery. All surgeries were performed by one of the study authors, Gregory A. Dumanian, MD, also of Northwestern.

The investigators used pain surveys from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), which was developed under the National Institutes of Health. The investigators called the PROMIS surveys, which are computer based, a “rigorous and reliable tool” to measure patient feedback in clinical research and healthcare settings. PROMIS is designed to measure, among other things, how pain impacts a patient’s behavior and interferes with his or her everyday functioning.

Dr. Park and his colleagues reported that the patients with at least 6 months of follow-up saw significant improvement in measures of pain interference (P less than 0.05), though not in pain behavior.

The researchers wrote in their analysis that the mesh used in securing the hernia repair – all patients in the study were treated with some type of mesh – might be why pain scores were seen to improve significantly at around 6 months.

“The changes noted in pain interference at the 4- to 8-month time frame may represent a physiologic change as the mesh solidly integrates and begins to contribute to a patient’s increasing ability to perform tasks.”

The mesh used in the study, the researchers also noted, was narrower than that generally reported for hernia repairs of this type.

Dr. Park and his colleagues described as limitations of their study the relatively small number of patients completing long-term follow-up. Also, the investigators noted, the PROMIS pain interference and pain behavior surveys “were not designed specifically with ventral hernia patients in mind, which may limit the scope of hernia-related symptoms covered” and that data on patients’ use of pain medications was not recorded.

The study authors reported no outside funding or conflicts of interest related to their findings.

Patients who have undergone open ventral abdominal hernia repair see significant improvements in some self-reported pain measures at 6 or more months after surgery, according to results from a new study.

The investigators, led by Eugene Park, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, suggested that the timing of the improvements may have to do with the mesh used in the surgeries.

For their research, published in the January issue of The American Journal of Surgery (2017;213:58-63), Dr. Park and his colleagues recruited 77 patients scheduled for midline incisional ventral hernia repair between 2010 and 2013 (mean age, 54 years; 45% female), who completed detailed pain surveys before surgery and during all postoperative visits; 38 patients completed surveys at least 6 months after surgery. All surgeries were performed by one of the study authors, Gregory A. Dumanian, MD, also of Northwestern.

The investigators used pain surveys from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), which was developed under the National Institutes of Health. The investigators called the PROMIS surveys, which are computer based, a “rigorous and reliable tool” to measure patient feedback in clinical research and healthcare settings. PROMIS is designed to measure, among other things, how pain impacts a patient’s behavior and interferes with his or her everyday functioning.

Dr. Park and his colleagues reported that the patients with at least 6 months of follow-up saw significant improvement in measures of pain interference (P less than 0.05), though not in pain behavior.

The researchers wrote in their analysis that the mesh used in securing the hernia repair – all patients in the study were treated with some type of mesh – might be why pain scores were seen to improve significantly at around 6 months.

“The changes noted in pain interference at the 4- to 8-month time frame may represent a physiologic change as the mesh solidly integrates and begins to contribute to a patient’s increasing ability to perform tasks.”

The mesh used in the study, the researchers also noted, was narrower than that generally reported for hernia repairs of this type.

Dr. Park and his colleagues described as limitations of their study the relatively small number of patients completing long-term follow-up. Also, the investigators noted, the PROMIS pain interference and pain behavior surveys “were not designed specifically with ventral hernia patients in mind, which may limit the scope of hernia-related symptoms covered” and that data on patients’ use of pain medications was not recorded.

The study authors reported no outside funding or conflicts of interest related to their findings.

Patients who have undergone open ventral abdominal hernia repair see significant improvements in some self-reported pain measures at 6 or more months after surgery, according to results from a new study.

The investigators, led by Eugene Park, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, suggested that the timing of the improvements may have to do with the mesh used in the surgeries.

For their research, published in the January issue of The American Journal of Surgery (2017;213:58-63), Dr. Park and his colleagues recruited 77 patients scheduled for midline incisional ventral hernia repair between 2010 and 2013 (mean age, 54 years; 45% female), who completed detailed pain surveys before surgery and during all postoperative visits; 38 patients completed surveys at least 6 months after surgery. All surgeries were performed by one of the study authors, Gregory A. Dumanian, MD, also of Northwestern.

The investigators used pain surveys from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), which was developed under the National Institutes of Health. The investigators called the PROMIS surveys, which are computer based, a “rigorous and reliable tool” to measure patient feedback in clinical research and healthcare settings. PROMIS is designed to measure, among other things, how pain impacts a patient’s behavior and interferes with his or her everyday functioning.

Dr. Park and his colleagues reported that the patients with at least 6 months of follow-up saw significant improvement in measures of pain interference (P less than 0.05), though not in pain behavior.

The researchers wrote in their analysis that the mesh used in securing the hernia repair – all patients in the study were treated with some type of mesh – might be why pain scores were seen to improve significantly at around 6 months.

“The changes noted in pain interference at the 4- to 8-month time frame may represent a physiologic change as the mesh solidly integrates and begins to contribute to a patient’s increasing ability to perform tasks.”

The mesh used in the study, the researchers also noted, was narrower than that generally reported for hernia repairs of this type.

Dr. Park and his colleagues described as limitations of their study the relatively small number of patients completing long-term follow-up. Also, the investigators noted, the PROMIS pain interference and pain behavior surveys “were not designed specifically with ventral hernia patients in mind, which may limit the scope of hernia-related symptoms covered” and that data on patients’ use of pain medications was not recorded.

The study authors reported no outside funding or conflicts of interest related to their findings.

Key clinical point: People undergoing open ventral hernia repair saw significant improvements in self-reported pain starting at about 6 months after their procedures.

Major finding: Reported reductions of pain interference were significant among patients with 6 or more months’ follow-up (P less than .05).

Data source: 77 patients undergoing open ventral hernia repairs who completed validated pain questionnaires pre- and post-surgery; of these, 38 had follow-up of 6 months or longer.

Disclosures: None.

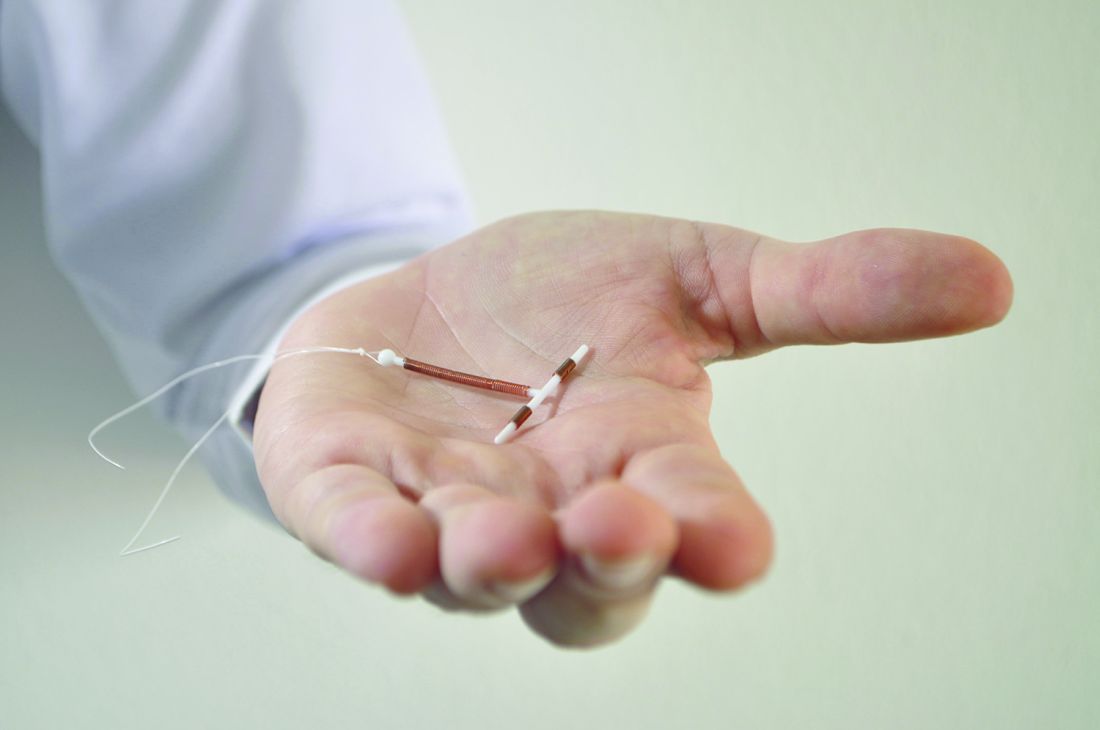

Immediate postpartum LARC requires cross-disciplinary cooperation in the hospital

Hospitals that aim to offer women long-acting reversible contraception immediately after giving birth require up-front coordination across departments, including early recruitment of nonclinical staff, researchers have found.

One of the advantages to offering LARC postpartum in the hospital, instead of an outpatient clinic, is that patients are not required to present for repeat visits. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has called the immediate postpartum period an optimal time for LARC placement.

In an effort to fill in this knowledge gap, a team of investigators led by Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, sought to identify barriers to implementation and characteristics of successful efforts among hospitals developing postpartum LARC programs.

Dr. Hofler’s team interviewed clinicians and staff members, including pharmacists and billing employees, at 10 Georgia hospitals starting in March 2015, about a year after the state approved a separate Medicaid-reimbursement protocol for immediate postpartum LARC. Of the hospitals in the study, nine were attempting to launch programs during the study period, and four had active programs by the study endpoint (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:3–9).

Dr. Hofler and her colleagues found – through interviews conducted separately with 32 employees in clinical or administrative roles – that the hospitals that had succeeded had engaged multidisciplinary teams early in the process.

“We found that implementing an immediate postpartum LARC program in the hospital is initially more complicated than people think, and involves the participation of departments that people might overlook,” Dr. Hofler said in an interview. “It’s about engaging a pharmacy person, a billing person, or a health records expert in addition to the usual nursing and physician staff that one engages when you have some sort of clinical practice change.”

Barriers to successful programs included staff lack of knowledge about LARC, financial concerns, and competing priorities within hospitals, the team found.

“Several participants had little previous exposure to LARC, and clinicians did not always easily appreciate the differences between providing LARC in the inpatient and outpatient settings,” Dr. Hofler and her colleagues reported in their study.

“Early involvement of the necessary members of the implementation team leads to better communication and understanding of the project,” the researchers concluded, noting that implementation cannot move forward without “financial reassurance early in the process.”

Teams should include representation from direct clinical care personnel, pharmacy, or finance and billing, they reported, though the specific team members may vary by hospital.

“Consistent communication and team planning with clear roles and responsibilities are key to navigating the complex and interconnected steps” in launching a program, they wrote.

Though Dr. Hofler stressed that the report was not meant to substitute for formal guidance, it maps the steps needed, and the departments involved, at each stage of the implementation process, from exploration of a program to its eventual launch and maintenance.

The study was supported by a grant from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Two of the coauthors disclosed research funding or other relationships with LARC manufacturers.

Hospitals that aim to offer women long-acting reversible contraception immediately after giving birth require up-front coordination across departments, including early recruitment of nonclinical staff, researchers have found.

One of the advantages to offering LARC postpartum in the hospital, instead of an outpatient clinic, is that patients are not required to present for repeat visits. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has called the immediate postpartum period an optimal time for LARC placement.

In an effort to fill in this knowledge gap, a team of investigators led by Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, sought to identify barriers to implementation and characteristics of successful efforts among hospitals developing postpartum LARC programs.

Dr. Hofler’s team interviewed clinicians and staff members, including pharmacists and billing employees, at 10 Georgia hospitals starting in March 2015, about a year after the state approved a separate Medicaid-reimbursement protocol for immediate postpartum LARC. Of the hospitals in the study, nine were attempting to launch programs during the study period, and four had active programs by the study endpoint (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:3–9).

Dr. Hofler and her colleagues found – through interviews conducted separately with 32 employees in clinical or administrative roles – that the hospitals that had succeeded had engaged multidisciplinary teams early in the process.

“We found that implementing an immediate postpartum LARC program in the hospital is initially more complicated than people think, and involves the participation of departments that people might overlook,” Dr. Hofler said in an interview. “It’s about engaging a pharmacy person, a billing person, or a health records expert in addition to the usual nursing and physician staff that one engages when you have some sort of clinical practice change.”

Barriers to successful programs included staff lack of knowledge about LARC, financial concerns, and competing priorities within hospitals, the team found.

“Several participants had little previous exposure to LARC, and clinicians did not always easily appreciate the differences between providing LARC in the inpatient and outpatient settings,” Dr. Hofler and her colleagues reported in their study.

“Early involvement of the necessary members of the implementation team leads to better communication and understanding of the project,” the researchers concluded, noting that implementation cannot move forward without “financial reassurance early in the process.”

Teams should include representation from direct clinical care personnel, pharmacy, or finance and billing, they reported, though the specific team members may vary by hospital.

“Consistent communication and team planning with clear roles and responsibilities are key to navigating the complex and interconnected steps” in launching a program, they wrote.

Though Dr. Hofler stressed that the report was not meant to substitute for formal guidance, it maps the steps needed, and the departments involved, at each stage of the implementation process, from exploration of a program to its eventual launch and maintenance.

The study was supported by a grant from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Two of the coauthors disclosed research funding or other relationships with LARC manufacturers.

Hospitals that aim to offer women long-acting reversible contraception immediately after giving birth require up-front coordination across departments, including early recruitment of nonclinical staff, researchers have found.

One of the advantages to offering LARC postpartum in the hospital, instead of an outpatient clinic, is that patients are not required to present for repeat visits. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has called the immediate postpartum period an optimal time for LARC placement.

In an effort to fill in this knowledge gap, a team of investigators led by Lisa G. Hofler, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta, sought to identify barriers to implementation and characteristics of successful efforts among hospitals developing postpartum LARC programs.

Dr. Hofler’s team interviewed clinicians and staff members, including pharmacists and billing employees, at 10 Georgia hospitals starting in March 2015, about a year after the state approved a separate Medicaid-reimbursement protocol for immediate postpartum LARC. Of the hospitals in the study, nine were attempting to launch programs during the study period, and four had active programs by the study endpoint (Obstet Gynecol 2017;129:3–9).

Dr. Hofler and her colleagues found – through interviews conducted separately with 32 employees in clinical or administrative roles – that the hospitals that had succeeded had engaged multidisciplinary teams early in the process.

“We found that implementing an immediate postpartum LARC program in the hospital is initially more complicated than people think, and involves the participation of departments that people might overlook,” Dr. Hofler said in an interview. “It’s about engaging a pharmacy person, a billing person, or a health records expert in addition to the usual nursing and physician staff that one engages when you have some sort of clinical practice change.”

Barriers to successful programs included staff lack of knowledge about LARC, financial concerns, and competing priorities within hospitals, the team found.

“Several participants had little previous exposure to LARC, and clinicians did not always easily appreciate the differences between providing LARC in the inpatient and outpatient settings,” Dr. Hofler and her colleagues reported in their study.

“Early involvement of the necessary members of the implementation team leads to better communication and understanding of the project,” the researchers concluded, noting that implementation cannot move forward without “financial reassurance early in the process.”

Teams should include representation from direct clinical care personnel, pharmacy, or finance and billing, they reported, though the specific team members may vary by hospital.

“Consistent communication and team planning with clear roles and responsibilities are key to navigating the complex and interconnected steps” in launching a program, they wrote.

Though Dr. Hofler stressed that the report was not meant to substitute for formal guidance, it maps the steps needed, and the departments involved, at each stage of the implementation process, from exploration of a program to its eventual launch and maintenance.

The study was supported by a grant from the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Two of the coauthors disclosed research funding or other relationships with LARC manufacturers.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Success in establishing an immediate postpartum LARC program involves team-building across hospital disciplines.

Major finding: Factors associated with success included early coordination among financial, administrative, pharmacy, and clinical personnel.

Data source: A qualitative analysis of interviews with 32 employees (clinical and nonclinical) from 10 hospitals in Georgia.

Disclosures: Two authors disclosed relationships with LARC manufacturers.

Curricular milestones in rheumatology: Is granular better?

A new curricular “road map” attempts to lay out precisely what rheumatology fellows are expected to be able to know and do at different time points in their training.

The 80 “curricular milestones” for rheumatology, developed under the direction of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, are meant to complement the 23 internal medicine subspecialty reporting milestones already mandated by the ACGME for use in trainee evaluation.

Unlike the reporting milestones, which came into use in 2014, the curricular milestones are not compulsory. Instead they “offer a guide so that trainees and the people teaching them know what’s expected of them,” said Lisa Criscione-Schreiber, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., the lead author of a recent article in Arthritis Care & Research describing the new milestones (Arthritis Care Res. 2016 Nov 11. doi: 10.1002/acr.23151).

While the reporting milestones are designed to target broader competencies, the curricular milestones are highly granular. For example, a rheumatology fellow at 12 months is expected to be able to “perform compensated polarized microscopy to examine and interpret synovial fluid,” according to one milestone; before 24 months of training, he or she is expected to be able to teach others to do the same.

Authors of an accompanying editorial (Arthritis Care Res. 2016 Nov 11. doi: 10.1002/acr.23150) by Richard Panush, MD, of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, Eric Hsieh, MD, also of USC, and Nortin Hadler, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, praised the curricular milestones as meticulous and well conceived, but questioned their complexity and the broader push toward rubric-based training, particularly in the absence of evidence showing it to be superior to established methods.

Ultimately, Dr. Panush acknowledged in an interview, the move to milestones – including the curricular milestones – may prove worthwhile. But it simply “isn’t as sufficiently grounded in science as we would have liked for such a major departure from everything we have done, and with all that implementing the change would imply: the time, the manpower, the cost,” he said.

A leap of faith?