User login

Does your patient really need a supplement?

Lung cancer screening: USPSTF revises its recommendation

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released a draft recommendation on lung cancer screen- ing, advising annual screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for individuals at high risk for lung cancer based on age and smoking history. Once finalized, this recommendation will replace its “I” rating, which indicated that evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against screening for lung cancer.

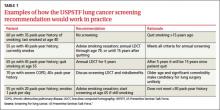

While the wording of the new recommendation is nonspecific regarding who should be screened, the Task Force elaborates in its follow-on commentary: Screening should start at age 55 and continue through age 79 for those who have ≥30 pack-year history of smoking and are either current smokers or past smokers who quit <15 years earlier.1 The draft recommendation advises caution in screening those with significant comorbidities, as well as individuals in their late 70s. Examples of how these specifications would work in practice are included in TABLE 1.

Lung cancer epidemiology

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer in both men and women and the leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, accounting for more than 158,000 deaths in 2010.2 Lung cancer is highly lethal, with >90% mortality rate and a 5-year survival rate <20%.1 However, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which can be cured with surgical resection if caught early, is responsible for 80% of cases.3 The incidence of lung cancer increases markedly after age 50, with >80% of cases occurring in those 60 years or older.3

Smoking causes >90% of lung cancers,2 which are preventable with avoidance of smoking and smoking cessation programs. Currently, 19% of Americans smoke and 37% are current or former smokers.1

Evidence report

The systematic review4 that the new draft rec- ommendation was based on found 4 clinical trials of LDCT screening that met inclusion criteria (TABLE 2). One, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), was a large study involving 33 centers in the United States and 53,454 current and former smokers ages 55 to 74 years. Participants had a mean age of 61.4 years and ≥30 pack-year history of smoking, with a mean of 56 pack-years.5

The study population was relatively young and healthy; only 8.8% of participants were older than 70. The researchers excluded anyone with a significant comorbidity that would make it unlikely that they would undergo surgery if cancer were detected.

Participants were randomized to either LDCT or chest x-ray, given 3 annual screens, and followed for a mean of 6.5 years. In the LDCT group, there was a 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality and a 7% decrease in overall mortality. This translates to a number needed to screen (NNS) of 320 to prevent one lung cancer death, which compares favorably with other cancer screening tests. Mammography has an NNS of about 1339 for women ages 50 to 59, for example, and colon cancer screening using flexible sigmoidoscopy has an NNS of 817 among individuals ages 55 to 74 years.4

The other 3 studies in the systematic review were conducted in other countries, and were smaller, of shorter duration, and of lower quality.6-8 None demonstrated a reduction in either lung cancer or all-cause mortality, and one showed a small increase in all-cause mortality.8 A Forest plot of all 4 studies raises questions about the significance of the decline in all-cause or lung-cancer mortality.4 However, a meta-analysis that deletes the one poor quality study did demonstrate a 19% decrease in lung cancer mortality, but no decline in all- cause mortality.9

The evidence report included an assessment of 15 studies on the accuracy of LDCT screening. Sensitivity varied from 80% to 100% and specificity ranged from 28% to 100%. The positive predictive value (PPV) for lung cancer ranged from 2% to 42%; however, most abnormal findings resolved with further imaging. As a result, the PPV for those who had a biopsy or surgery after retesting was 50% to 92%.4

Potential harms in the recommendation

Radiation exposure from an LDCT is slightly greater than that of a mammogram. The long-term effects of annual LDCT plus follow-up of abnormal findings is not fully known. There is some concern about the potential for lung cancer screening to have a negative effect on smoking cessation efforts. However, evidence suggests that the use of LDCT as a lung cancer screening tool has no influence on smoking cessation.4

Extrapolating results. The NLST was a well-controlled trial conducted at academic health centers, with strict procedures for conservative follow-up of suspicious lesions. A potential for harm exists in extrapolating results from such a study to the community at large, where work-ups may be more aggressive and include biopsy.

Overdiagnosis. Routine LDCT will likely result in some degree of overdiagnosis—eg, detection of low-grade cancers that would either regress on their own or simply not progress—and overtreatment, with the potential for complications.

Full impact is unknown

The ultimate balance of benefits and harms of the USPSTF’s lung cancer screening draft recommendation rests on some unknowns. Widespread screening is unlikely to achieve the same results as did the NLST. As already noted, those enrolled in the NLST were relatively young and had large pack-year smoking histories. The Task Force acknowledges that the 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality achieved in the NLST is unlikely to be duplicated in older patients and individuals with less significant smoking histories. Additional harms will likely accrue if suspicious findings are more aggressively pursued than they were in this study. The potential harms, as well as benefits, from incidental findings on chest LDCT scans are also unknown.

The number of screenings. The potential for benefits beyond 3 screenings is also unknown, as the USPSTF’s projections in such cases are based on modeling. The degree of overdiagnosis is not fully understood, nor is the harm that could result from the accumulated radiation of what could be an annual LDCT for 25 years. The harm/benefit ratio will become clearer with time and can then be compared with other medical interventions.

Financial burden. While it may appear to some that the draft recommendation would unfairly benefit smokers by allowing them to undergo free annual CT screening, patients are likely to incur significant financial obligations as a result of doing so. The Affordable Care Act mandates that the annual LDCT screening would have to be offered with no patient cost sharing, but follow-up CTs for questionable findings, biopsies, and treatment will all be subject to deductibles and copayments.

Recommendations of others

Other organizations have adopted recommendations on lung cancer screening similar to the USPSTF proposal. These include the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Cancer Society, American College of Chest Physicians, American Lung Association, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and American Thoracic Society. Most apply to those ages 55 to 74 years and use other inclusion criteria of the NLST. Some stipulate that patients should be in good enough health to benefit from early detection, and most include a reference to the quality of the centers at which screening should occur. The American Academy of Family Physicians is currently considering what its recommendation on lung cancer screening will be.

Final USPSTF recommendation expected soon

Noticeably absent from the news coverage of the proposed USPSTF recommendation was the word “draft.” The Task Force has now collected public comments about its proposed recommendation and will be considering potential changes to the wording. Publication of the final recommendation is expected in December—shortly after press time.

1. Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement Draft. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservices- taskforce.org/uspstf13/lungcan/lungcandraftrec.htm. Accessed October 2, 2013.

2. Lung Cancer Statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/ statistics/. Updated October 23, 2013. Accessed November 15, 2013.

3. Lung Cancer Fact Sheet. American Lung Association Web site. Available at: http://www.lung.org/lung-disease/lung-cancer/resources/facts-figures/lung-cancer-fact-sheet.html#Prevalence_ and_Incidence. Accessed October 2, 2013.

4. Humphrey LL, Deffeback M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer using low-dose computed tomography. a systematic review to update the US Preventive Services Task Force Recom- mendation. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:411-420.

5. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team; Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395-409.

6. Saghir Z, Dirksen A, Ashraf H, et al. CT screening for lung cancer brings forward early disease. The randomised Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial: status after five annual screening rounds with low-dose CT. Thorax. 2012;67:296-301.

7. Infante M, Cavuto S, Lutman FR, et al; DANTE Study Group. A randomized study of lung cancer screening with spiral computed tomography: three-year results from the DANTE trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:445-453.

8. Pastorino U, Rossi M, Rosato V, et al. Annual or biennial CT screening versus observation in heavy smokers: 5-year results of the MILD trial. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21: 308-315.

9. Humphrey L, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer: systematic review to update the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Evidence Synthesis No. 105. AHRQ Publication No. 13-05188-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health- care Research and Quality; 2013. Available at: http://www.uspre- ventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf13/lungcan/lungcanes105. pdf. Accessed October 2, 2013.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released a draft recommendation on lung cancer screen- ing, advising annual screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for individuals at high risk for lung cancer based on age and smoking history. Once finalized, this recommendation will replace its “I” rating, which indicated that evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against screening for lung cancer.

While the wording of the new recommendation is nonspecific regarding who should be screened, the Task Force elaborates in its follow-on commentary: Screening should start at age 55 and continue through age 79 for those who have ≥30 pack-year history of smoking and are either current smokers or past smokers who quit <15 years earlier.1 The draft recommendation advises caution in screening those with significant comorbidities, as well as individuals in their late 70s. Examples of how these specifications would work in practice are included in TABLE 1.

Lung cancer epidemiology

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer in both men and women and the leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, accounting for more than 158,000 deaths in 2010.2 Lung cancer is highly lethal, with >90% mortality rate and a 5-year survival rate <20%.1 However, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which can be cured with surgical resection if caught early, is responsible for 80% of cases.3 The incidence of lung cancer increases markedly after age 50, with >80% of cases occurring in those 60 years or older.3

Smoking causes >90% of lung cancers,2 which are preventable with avoidance of smoking and smoking cessation programs. Currently, 19% of Americans smoke and 37% are current or former smokers.1

Evidence report

The systematic review4 that the new draft rec- ommendation was based on found 4 clinical trials of LDCT screening that met inclusion criteria (TABLE 2). One, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), was a large study involving 33 centers in the United States and 53,454 current and former smokers ages 55 to 74 years. Participants had a mean age of 61.4 years and ≥30 pack-year history of smoking, with a mean of 56 pack-years.5

The study population was relatively young and healthy; only 8.8% of participants were older than 70. The researchers excluded anyone with a significant comorbidity that would make it unlikely that they would undergo surgery if cancer were detected.

Participants were randomized to either LDCT or chest x-ray, given 3 annual screens, and followed for a mean of 6.5 years. In the LDCT group, there was a 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality and a 7% decrease in overall mortality. This translates to a number needed to screen (NNS) of 320 to prevent one lung cancer death, which compares favorably with other cancer screening tests. Mammography has an NNS of about 1339 for women ages 50 to 59, for example, and colon cancer screening using flexible sigmoidoscopy has an NNS of 817 among individuals ages 55 to 74 years.4

The other 3 studies in the systematic review were conducted in other countries, and were smaller, of shorter duration, and of lower quality.6-8 None demonstrated a reduction in either lung cancer or all-cause mortality, and one showed a small increase in all-cause mortality.8 A Forest plot of all 4 studies raises questions about the significance of the decline in all-cause or lung-cancer mortality.4 However, a meta-analysis that deletes the one poor quality study did demonstrate a 19% decrease in lung cancer mortality, but no decline in all- cause mortality.9

The evidence report included an assessment of 15 studies on the accuracy of LDCT screening. Sensitivity varied from 80% to 100% and specificity ranged from 28% to 100%. The positive predictive value (PPV) for lung cancer ranged from 2% to 42%; however, most abnormal findings resolved with further imaging. As a result, the PPV for those who had a biopsy or surgery after retesting was 50% to 92%.4

Potential harms in the recommendation

Radiation exposure from an LDCT is slightly greater than that of a mammogram. The long-term effects of annual LDCT plus follow-up of abnormal findings is not fully known. There is some concern about the potential for lung cancer screening to have a negative effect on smoking cessation efforts. However, evidence suggests that the use of LDCT as a lung cancer screening tool has no influence on smoking cessation.4

Extrapolating results. The NLST was a well-controlled trial conducted at academic health centers, with strict procedures for conservative follow-up of suspicious lesions. A potential for harm exists in extrapolating results from such a study to the community at large, where work-ups may be more aggressive and include biopsy.

Overdiagnosis. Routine LDCT will likely result in some degree of overdiagnosis—eg, detection of low-grade cancers that would either regress on their own or simply not progress—and overtreatment, with the potential for complications.

Full impact is unknown

The ultimate balance of benefits and harms of the USPSTF’s lung cancer screening draft recommendation rests on some unknowns. Widespread screening is unlikely to achieve the same results as did the NLST. As already noted, those enrolled in the NLST were relatively young and had large pack-year smoking histories. The Task Force acknowledges that the 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality achieved in the NLST is unlikely to be duplicated in older patients and individuals with less significant smoking histories. Additional harms will likely accrue if suspicious findings are more aggressively pursued than they were in this study. The potential harms, as well as benefits, from incidental findings on chest LDCT scans are also unknown.

The number of screenings. The potential for benefits beyond 3 screenings is also unknown, as the USPSTF’s projections in such cases are based on modeling. The degree of overdiagnosis is not fully understood, nor is the harm that could result from the accumulated radiation of what could be an annual LDCT for 25 years. The harm/benefit ratio will become clearer with time and can then be compared with other medical interventions.

Financial burden. While it may appear to some that the draft recommendation would unfairly benefit smokers by allowing them to undergo free annual CT screening, patients are likely to incur significant financial obligations as a result of doing so. The Affordable Care Act mandates that the annual LDCT screening would have to be offered with no patient cost sharing, but follow-up CTs for questionable findings, biopsies, and treatment will all be subject to deductibles and copayments.

Recommendations of others

Other organizations have adopted recommendations on lung cancer screening similar to the USPSTF proposal. These include the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Cancer Society, American College of Chest Physicians, American Lung Association, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and American Thoracic Society. Most apply to those ages 55 to 74 years and use other inclusion criteria of the NLST. Some stipulate that patients should be in good enough health to benefit from early detection, and most include a reference to the quality of the centers at which screening should occur. The American Academy of Family Physicians is currently considering what its recommendation on lung cancer screening will be.

Final USPSTF recommendation expected soon

Noticeably absent from the news coverage of the proposed USPSTF recommendation was the word “draft.” The Task Force has now collected public comments about its proposed recommendation and will be considering potential changes to the wording. Publication of the final recommendation is expected in December—shortly after press time.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released a draft recommendation on lung cancer screen- ing, advising annual screening with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for individuals at high risk for lung cancer based on age and smoking history. Once finalized, this recommendation will replace its “I” rating, which indicated that evidence was insufficient to recommend for or against screening for lung cancer.

While the wording of the new recommendation is nonspecific regarding who should be screened, the Task Force elaborates in its follow-on commentary: Screening should start at age 55 and continue through age 79 for those who have ≥30 pack-year history of smoking and are either current smokers or past smokers who quit <15 years earlier.1 The draft recommendation advises caution in screening those with significant comorbidities, as well as individuals in their late 70s. Examples of how these specifications would work in practice are included in TABLE 1.

Lung cancer epidemiology

Lung cancer is the second most common cancer in both men and women and the leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States, accounting for more than 158,000 deaths in 2010.2 Lung cancer is highly lethal, with >90% mortality rate and a 5-year survival rate <20%.1 However, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which can be cured with surgical resection if caught early, is responsible for 80% of cases.3 The incidence of lung cancer increases markedly after age 50, with >80% of cases occurring in those 60 years or older.3

Smoking causes >90% of lung cancers,2 which are preventable with avoidance of smoking and smoking cessation programs. Currently, 19% of Americans smoke and 37% are current or former smokers.1

Evidence report

The systematic review4 that the new draft rec- ommendation was based on found 4 clinical trials of LDCT screening that met inclusion criteria (TABLE 2). One, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), was a large study involving 33 centers in the United States and 53,454 current and former smokers ages 55 to 74 years. Participants had a mean age of 61.4 years and ≥30 pack-year history of smoking, with a mean of 56 pack-years.5

The study population was relatively young and healthy; only 8.8% of participants were older than 70. The researchers excluded anyone with a significant comorbidity that would make it unlikely that they would undergo surgery if cancer were detected.

Participants were randomized to either LDCT or chest x-ray, given 3 annual screens, and followed for a mean of 6.5 years. In the LDCT group, there was a 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality and a 7% decrease in overall mortality. This translates to a number needed to screen (NNS) of 320 to prevent one lung cancer death, which compares favorably with other cancer screening tests. Mammography has an NNS of about 1339 for women ages 50 to 59, for example, and colon cancer screening using flexible sigmoidoscopy has an NNS of 817 among individuals ages 55 to 74 years.4

The other 3 studies in the systematic review were conducted in other countries, and were smaller, of shorter duration, and of lower quality.6-8 None demonstrated a reduction in either lung cancer or all-cause mortality, and one showed a small increase in all-cause mortality.8 A Forest plot of all 4 studies raises questions about the significance of the decline in all-cause or lung-cancer mortality.4 However, a meta-analysis that deletes the one poor quality study did demonstrate a 19% decrease in lung cancer mortality, but no decline in all- cause mortality.9

The evidence report included an assessment of 15 studies on the accuracy of LDCT screening. Sensitivity varied from 80% to 100% and specificity ranged from 28% to 100%. The positive predictive value (PPV) for lung cancer ranged from 2% to 42%; however, most abnormal findings resolved with further imaging. As a result, the PPV for those who had a biopsy or surgery after retesting was 50% to 92%.4

Potential harms in the recommendation

Radiation exposure from an LDCT is slightly greater than that of a mammogram. The long-term effects of annual LDCT plus follow-up of abnormal findings is not fully known. There is some concern about the potential for lung cancer screening to have a negative effect on smoking cessation efforts. However, evidence suggests that the use of LDCT as a lung cancer screening tool has no influence on smoking cessation.4

Extrapolating results. The NLST was a well-controlled trial conducted at academic health centers, with strict procedures for conservative follow-up of suspicious lesions. A potential for harm exists in extrapolating results from such a study to the community at large, where work-ups may be more aggressive and include biopsy.

Overdiagnosis. Routine LDCT will likely result in some degree of overdiagnosis—eg, detection of low-grade cancers that would either regress on their own or simply not progress—and overtreatment, with the potential for complications.

Full impact is unknown

The ultimate balance of benefits and harms of the USPSTF’s lung cancer screening draft recommendation rests on some unknowns. Widespread screening is unlikely to achieve the same results as did the NLST. As already noted, those enrolled in the NLST were relatively young and had large pack-year smoking histories. The Task Force acknowledges that the 20% reduction in lung cancer mortality achieved in the NLST is unlikely to be duplicated in older patients and individuals with less significant smoking histories. Additional harms will likely accrue if suspicious findings are more aggressively pursued than they were in this study. The potential harms, as well as benefits, from incidental findings on chest LDCT scans are also unknown.

The number of screenings. The potential for benefits beyond 3 screenings is also unknown, as the USPSTF’s projections in such cases are based on modeling. The degree of overdiagnosis is not fully understood, nor is the harm that could result from the accumulated radiation of what could be an annual LDCT for 25 years. The harm/benefit ratio will become clearer with time and can then be compared with other medical interventions.

Financial burden. While it may appear to some that the draft recommendation would unfairly benefit smokers by allowing them to undergo free annual CT screening, patients are likely to incur significant financial obligations as a result of doing so. The Affordable Care Act mandates that the annual LDCT screening would have to be offered with no patient cost sharing, but follow-up CTs for questionable findings, biopsies, and treatment will all be subject to deductibles and copayments.

Recommendations of others

Other organizations have adopted recommendations on lung cancer screening similar to the USPSTF proposal. These include the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Cancer Society, American College of Chest Physicians, American Lung Association, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and American Thoracic Society. Most apply to those ages 55 to 74 years and use other inclusion criteria of the NLST. Some stipulate that patients should be in good enough health to benefit from early detection, and most include a reference to the quality of the centers at which screening should occur. The American Academy of Family Physicians is currently considering what its recommendation on lung cancer screening will be.

Final USPSTF recommendation expected soon

Noticeably absent from the news coverage of the proposed USPSTF recommendation was the word “draft.” The Task Force has now collected public comments about its proposed recommendation and will be considering potential changes to the wording. Publication of the final recommendation is expected in December—shortly after press time.

1. Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement Draft. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservices- taskforce.org/uspstf13/lungcan/lungcandraftrec.htm. Accessed October 2, 2013.

2. Lung Cancer Statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/ statistics/. Updated October 23, 2013. Accessed November 15, 2013.

3. Lung Cancer Fact Sheet. American Lung Association Web site. Available at: http://www.lung.org/lung-disease/lung-cancer/resources/facts-figures/lung-cancer-fact-sheet.html#Prevalence_ and_Incidence. Accessed October 2, 2013.

4. Humphrey LL, Deffeback M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer using low-dose computed tomography. a systematic review to update the US Preventive Services Task Force Recom- mendation. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:411-420.

5. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team; Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395-409.

6. Saghir Z, Dirksen A, Ashraf H, et al. CT screening for lung cancer brings forward early disease. The randomised Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial: status after five annual screening rounds with low-dose CT. Thorax. 2012;67:296-301.

7. Infante M, Cavuto S, Lutman FR, et al; DANTE Study Group. A randomized study of lung cancer screening with spiral computed tomography: three-year results from the DANTE trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:445-453.

8. Pastorino U, Rossi M, Rosato V, et al. Annual or biennial CT screening versus observation in heavy smokers: 5-year results of the MILD trial. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21: 308-315.

9. Humphrey L, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer: systematic review to update the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Evidence Synthesis No. 105. AHRQ Publication No. 13-05188-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health- care Research and Quality; 2013. Available at: http://www.uspre- ventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf13/lungcan/lungcanes105. pdf. Accessed October 2, 2013.

1. Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement Draft. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservices- taskforce.org/uspstf13/lungcan/lungcandraftrec.htm. Accessed October 2, 2013.

2. Lung Cancer Statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/ statistics/. Updated October 23, 2013. Accessed November 15, 2013.

3. Lung Cancer Fact Sheet. American Lung Association Web site. Available at: http://www.lung.org/lung-disease/lung-cancer/resources/facts-figures/lung-cancer-fact-sheet.html#Prevalence_ and_Incidence. Accessed October 2, 2013.

4. Humphrey LL, Deffeback M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer using low-dose computed tomography. a systematic review to update the US Preventive Services Task Force Recom- mendation. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:411-420.

5. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team; Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. Reduced lung cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395-409.

6. Saghir Z, Dirksen A, Ashraf H, et al. CT screening for lung cancer brings forward early disease. The randomised Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial: status after five annual screening rounds with low-dose CT. Thorax. 2012;67:296-301.

7. Infante M, Cavuto S, Lutman FR, et al; DANTE Study Group. A randomized study of lung cancer screening with spiral computed tomography: three-year results from the DANTE trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:445-453.

8. Pastorino U, Rossi M, Rosato V, et al. Annual or biennial CT screening versus observation in heavy smokers: 5-year results of the MILD trial. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21: 308-315.

9. Humphrey L, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer: systematic review to update the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Evidence Synthesis No. 105. AHRQ Publication No. 13-05188-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health- care Research and Quality; 2013. Available at: http://www.uspre- ventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf13/lungcan/lungcanes105. pdf. Accessed October 2, 2013.

Drug resistance: What FPs can do

Influenza: Update for the 2013-2014 Season

Each year in late summer, the CDC publishes its recommendations for the prevention of influenza for the upcoming season. The severity of each influenza season varies and is difficult to predict—underscoring the need to provide maximal vaccine coverage for at-risk patient populations.

Hoping for the best, planning for the worst.

Over the past several decades, the annual number of influenza-related hospitalizations has varied from approximately 55,000 to 431,000,1 and the number of deaths from influenza has been as low as 3,349 and as high as 48,614.2 Infection rates are usually highest in children.

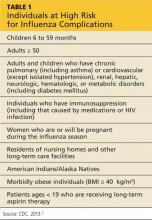

Complications, hospitalizations, and deaths are highest in adults ≥ 65, children < 2 years, and patients with medical conditions known to increase risk for influenza complications. Those at high risk of complications appear in Table 1.3

The main recommendations for this coming year are the same as those for last year, including vaccinating everyone ≥ 6 months of age without a contraindication, starting vaccinations as soon as vaccine is available, and continuing throughout the influenza season for those who need it.

What’s new this year

An increasing number of influenza vaccine products are available; although to date, their effectiveness (which was determined to be 56% for all vaccines used last influenza season)4 remains below what we would hope for. The CDC’s recommendations address these new types of vaccines, including ones that have four antigens instead of three, and use new terminology to describe the vaccines.3

New terminology reflects changing vaccine formulations.

Last influenza season there were two major categories of influenza vaccines: live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV). All products were produced using egg-culture methods and contained two influenza A antigen subtypes and oneB subtype.

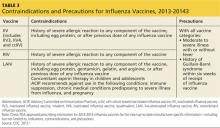

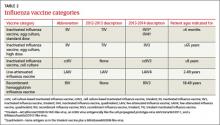

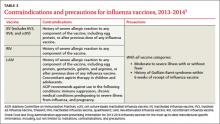

Several products this year include four antigens (two A subtypes and two B subtypes), and some are now produced with non–egg-culture methods. This has led to a new system of classification, with the term inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) replacing TIV. Table 2 lists the influenza vaccine categories and abbreviations. Table 33 lists the contraindications for the different vaccine types.

The new products include Flumist Quadrivalent (MedImmune), a quadrivalent LAIV (LAIV4); Fluarix Quadrivalent (GlaxoSmithKline), a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4); Flucelvax (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics), a cell culture-based trivalent IIV (ccIIV3); and FluBlok (Protein Sciences), a trivalent recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine (RIV3). Fluzone (Sanofi Pasteur), introduced last season in a trivalent formulation, is also available this season as a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4).

As a group, influenza vaccine products now offer three routes of administration: intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intranasal. There is currently no evidence that any route offers an advantage over another, and the CDC states no preference for any particular product or route of administration.

Mercury content is not a problem

Even though there is no scientific controversy over the safety of the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal, some patients still have doubts and may ask for a thimerosal-free product. The only influenza products that contain any thimerosal are those that come in multidose vials. A description of each influenza vaccine product, including thimerosal content, indicated ages, and routes of administration, can be found on the CDC’s Web site (www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).3

Options for those with egg allergy

There is now a product, RIV3 (FluBlok), that is manufactured without the use of eggs. It can be used in those 18 to 49 years of age with a history of egg allergy of any severity. Since 2011, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended that individuals with a history of mild egg allergy (those who experience only hives after egg exposure) may receive IIV, with additional safety precautions. Do not delay vaccination for these individuals if RIV is unavailable. Because of a lack of data demonstrating safety of LAIV for individuals with egg allergy, those allergic to eggs should receive RIV or IIV rather than LAIV.

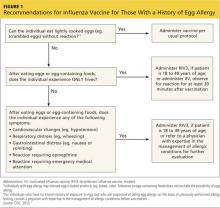

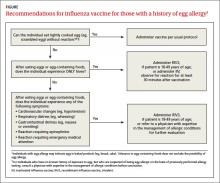

Though the new ccIIV product, Flucelvax, is manufactured without the use of eggs, the seed viruses used to create the vaccine have been processed in eggs. The egg protein content in the vaccine is extremely low (< 50 femtograms [5 × 10-14 g] per 0.5-mL dose), but the CDC does not consider it egg free. Figure 1 (see page 32) depicts the recommendations for those with a history of egg allergy.3

Other interventions for influenza prevention

Vaccination is only one tool available to prevent morbidity and mortality from influenza. Antiviral chemoprevention and treatment and infection control practices can also be effective.

Antiviral chemoprevention is available for both pre- and post-exposure administration. In the past few years, the CDC has de-emphasized such use of antivirals for these indications out of concern for the supply of these agents and for the possibility that their use might lead to increased rates of viral resistance. Consider antiviral chemoprevention for those who have conditions that place them at risk for complications, and for those who are unvaccinated if they are at high risk for exposure to influenza (pre-exposure prophylaxis) or have been exposed (postexposure prophylaxis), if the medication can be started within 48 hours of exposure.

Another option for unvaccinated high-risk patients is vigilant symptom monitoring with early treatment for influenza symptoms. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended in addition to vaccination to control influenza outbreaks at institutions that house patients at high risk for complications of influenza. Details on recommended antivirals including doses and duration of treatment can be found in a 2011 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.5

Antiviral treatment. The CDC recommends antiviral treatment for anyone with suspected or confirmed influenza who has progressive, severe, or complicated illness or is hospitalized for his or her illness.5 Treatment is also recommended for outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are at higher risk for influenza complications. This latter group includes those in Table 1, particularly children 6 to 59 months and adults ≥ 50. Start antiviral treatment within 48 hours of the first symptoms. For hospitalized patients, however, begin treatment at any point, regardless of duration of illness.

Infection control practices can prevent the spread of influenza in the health care setting and in the homes of those with influenza. These practices are also described on the CDC influenza Web site.6

References

1. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333-1340.

2. CDC. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza–United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057-1062.

3. CDC. Summary* recommendations: prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—(ACIP)—United States, 2013-14. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm. Accessed August 9, 2013.

4. CDC. Interim adjusted estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness–United States, February 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:119-123.

5. CDC. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR01):1-24. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6001a1.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

6. CDC. Infection control in health care facilities. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/index.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

Each year in late summer, the CDC publishes its recommendations for the prevention of influenza for the upcoming season. The severity of each influenza season varies and is difficult to predict—underscoring the need to provide maximal vaccine coverage for at-risk patient populations.

Hoping for the best, planning for the worst.

Over the past several decades, the annual number of influenza-related hospitalizations has varied from approximately 55,000 to 431,000,1 and the number of deaths from influenza has been as low as 3,349 and as high as 48,614.2 Infection rates are usually highest in children.

Complications, hospitalizations, and deaths are highest in adults ≥ 65, children < 2 years, and patients with medical conditions known to increase risk for influenza complications. Those at high risk of complications appear in Table 1.3

The main recommendations for this coming year are the same as those for last year, including vaccinating everyone ≥ 6 months of age without a contraindication, starting vaccinations as soon as vaccine is available, and continuing throughout the influenza season for those who need it.

What’s new this year

An increasing number of influenza vaccine products are available; although to date, their effectiveness (which was determined to be 56% for all vaccines used last influenza season)4 remains below what we would hope for. The CDC’s recommendations address these new types of vaccines, including ones that have four antigens instead of three, and use new terminology to describe the vaccines.3

New terminology reflects changing vaccine formulations.

Last influenza season there were two major categories of influenza vaccines: live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV). All products were produced using egg-culture methods and contained two influenza A antigen subtypes and oneB subtype.

Several products this year include four antigens (two A subtypes and two B subtypes), and some are now produced with non–egg-culture methods. This has led to a new system of classification, with the term inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) replacing TIV. Table 2 lists the influenza vaccine categories and abbreviations. Table 33 lists the contraindications for the different vaccine types.

The new products include Flumist Quadrivalent (MedImmune), a quadrivalent LAIV (LAIV4); Fluarix Quadrivalent (GlaxoSmithKline), a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4); Flucelvax (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics), a cell culture-based trivalent IIV (ccIIV3); and FluBlok (Protein Sciences), a trivalent recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine (RIV3). Fluzone (Sanofi Pasteur), introduced last season in a trivalent formulation, is also available this season as a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4).

As a group, influenza vaccine products now offer three routes of administration: intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intranasal. There is currently no evidence that any route offers an advantage over another, and the CDC states no preference for any particular product or route of administration.

Mercury content is not a problem

Even though there is no scientific controversy over the safety of the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal, some patients still have doubts and may ask for a thimerosal-free product. The only influenza products that contain any thimerosal are those that come in multidose vials. A description of each influenza vaccine product, including thimerosal content, indicated ages, and routes of administration, can be found on the CDC’s Web site (www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).3

Options for those with egg allergy

There is now a product, RIV3 (FluBlok), that is manufactured without the use of eggs. It can be used in those 18 to 49 years of age with a history of egg allergy of any severity. Since 2011, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended that individuals with a history of mild egg allergy (those who experience only hives after egg exposure) may receive IIV, with additional safety precautions. Do not delay vaccination for these individuals if RIV is unavailable. Because of a lack of data demonstrating safety of LAIV for individuals with egg allergy, those allergic to eggs should receive RIV or IIV rather than LAIV.

Though the new ccIIV product, Flucelvax, is manufactured without the use of eggs, the seed viruses used to create the vaccine have been processed in eggs. The egg protein content in the vaccine is extremely low (< 50 femtograms [5 × 10-14 g] per 0.5-mL dose), but the CDC does not consider it egg free. Figure 1 (see page 32) depicts the recommendations for those with a history of egg allergy.3

Other interventions for influenza prevention

Vaccination is only one tool available to prevent morbidity and mortality from influenza. Antiviral chemoprevention and treatment and infection control practices can also be effective.

Antiviral chemoprevention is available for both pre- and post-exposure administration. In the past few years, the CDC has de-emphasized such use of antivirals for these indications out of concern for the supply of these agents and for the possibility that their use might lead to increased rates of viral resistance. Consider antiviral chemoprevention for those who have conditions that place them at risk for complications, and for those who are unvaccinated if they are at high risk for exposure to influenza (pre-exposure prophylaxis) or have been exposed (postexposure prophylaxis), if the medication can be started within 48 hours of exposure.

Another option for unvaccinated high-risk patients is vigilant symptom monitoring with early treatment for influenza symptoms. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended in addition to vaccination to control influenza outbreaks at institutions that house patients at high risk for complications of influenza. Details on recommended antivirals including doses and duration of treatment can be found in a 2011 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.5

Antiviral treatment. The CDC recommends antiviral treatment for anyone with suspected or confirmed influenza who has progressive, severe, or complicated illness or is hospitalized for his or her illness.5 Treatment is also recommended for outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are at higher risk for influenza complications. This latter group includes those in Table 1, particularly children 6 to 59 months and adults ≥ 50. Start antiviral treatment within 48 hours of the first symptoms. For hospitalized patients, however, begin treatment at any point, regardless of duration of illness.

Infection control practices can prevent the spread of influenza in the health care setting and in the homes of those with influenza. These practices are also described on the CDC influenza Web site.6

References

1. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333-1340.

2. CDC. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza–United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057-1062.

3. CDC. Summary* recommendations: prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—(ACIP)—United States, 2013-14. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm. Accessed August 9, 2013.

4. CDC. Interim adjusted estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness–United States, February 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:119-123.

5. CDC. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR01):1-24. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6001a1.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

6. CDC. Infection control in health care facilities. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/index.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

Each year in late summer, the CDC publishes its recommendations for the prevention of influenza for the upcoming season. The severity of each influenza season varies and is difficult to predict—underscoring the need to provide maximal vaccine coverage for at-risk patient populations.

Hoping for the best, planning for the worst.

Over the past several decades, the annual number of influenza-related hospitalizations has varied from approximately 55,000 to 431,000,1 and the number of deaths from influenza has been as low as 3,349 and as high as 48,614.2 Infection rates are usually highest in children.

Complications, hospitalizations, and deaths are highest in adults ≥ 65, children < 2 years, and patients with medical conditions known to increase risk for influenza complications. Those at high risk of complications appear in Table 1.3

The main recommendations for this coming year are the same as those for last year, including vaccinating everyone ≥ 6 months of age without a contraindication, starting vaccinations as soon as vaccine is available, and continuing throughout the influenza season for those who need it.

What’s new this year

An increasing number of influenza vaccine products are available; although to date, their effectiveness (which was determined to be 56% for all vaccines used last influenza season)4 remains below what we would hope for. The CDC’s recommendations address these new types of vaccines, including ones that have four antigens instead of three, and use new terminology to describe the vaccines.3

New terminology reflects changing vaccine formulations.

Last influenza season there were two major categories of influenza vaccines: live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV). All products were produced using egg-culture methods and contained two influenza A antigen subtypes and oneB subtype.

Several products this year include four antigens (two A subtypes and two B subtypes), and some are now produced with non–egg-culture methods. This has led to a new system of classification, with the term inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) replacing TIV. Table 2 lists the influenza vaccine categories and abbreviations. Table 33 lists the contraindications for the different vaccine types.

The new products include Flumist Quadrivalent (MedImmune), a quadrivalent LAIV (LAIV4); Fluarix Quadrivalent (GlaxoSmithKline), a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4); Flucelvax (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics), a cell culture-based trivalent IIV (ccIIV3); and FluBlok (Protein Sciences), a trivalent recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine (RIV3). Fluzone (Sanofi Pasteur), introduced last season in a trivalent formulation, is also available this season as a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4).

As a group, influenza vaccine products now offer three routes of administration: intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intranasal. There is currently no evidence that any route offers an advantage over another, and the CDC states no preference for any particular product or route of administration.

Mercury content is not a problem

Even though there is no scientific controversy over the safety of the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal, some patients still have doubts and may ask for a thimerosal-free product. The only influenza products that contain any thimerosal are those that come in multidose vials. A description of each influenza vaccine product, including thimerosal content, indicated ages, and routes of administration, can be found on the CDC’s Web site (www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).3

Options for those with egg allergy

There is now a product, RIV3 (FluBlok), that is manufactured without the use of eggs. It can be used in those 18 to 49 years of age with a history of egg allergy of any severity. Since 2011, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended that individuals with a history of mild egg allergy (those who experience only hives after egg exposure) may receive IIV, with additional safety precautions. Do not delay vaccination for these individuals if RIV is unavailable. Because of a lack of data demonstrating safety of LAIV for individuals with egg allergy, those allergic to eggs should receive RIV or IIV rather than LAIV.

Though the new ccIIV product, Flucelvax, is manufactured without the use of eggs, the seed viruses used to create the vaccine have been processed in eggs. The egg protein content in the vaccine is extremely low (< 50 femtograms [5 × 10-14 g] per 0.5-mL dose), but the CDC does not consider it egg free. Figure 1 (see page 32) depicts the recommendations for those with a history of egg allergy.3

Other interventions for influenza prevention

Vaccination is only one tool available to prevent morbidity and mortality from influenza. Antiviral chemoprevention and treatment and infection control practices can also be effective.

Antiviral chemoprevention is available for both pre- and post-exposure administration. In the past few years, the CDC has de-emphasized such use of antivirals for these indications out of concern for the supply of these agents and for the possibility that their use might lead to increased rates of viral resistance. Consider antiviral chemoprevention for those who have conditions that place them at risk for complications, and for those who are unvaccinated if they are at high risk for exposure to influenza (pre-exposure prophylaxis) or have been exposed (postexposure prophylaxis), if the medication can be started within 48 hours of exposure.

Another option for unvaccinated high-risk patients is vigilant symptom monitoring with early treatment for influenza symptoms. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended in addition to vaccination to control influenza outbreaks at institutions that house patients at high risk for complications of influenza. Details on recommended antivirals including doses and duration of treatment can be found in a 2011 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.5

Antiviral treatment. The CDC recommends antiviral treatment for anyone with suspected or confirmed influenza who has progressive, severe, or complicated illness or is hospitalized for his or her illness.5 Treatment is also recommended for outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are at higher risk for influenza complications. This latter group includes those in Table 1, particularly children 6 to 59 months and adults ≥ 50. Start antiviral treatment within 48 hours of the first symptoms. For hospitalized patients, however, begin treatment at any point, regardless of duration of illness.

Infection control practices can prevent the spread of influenza in the health care setting and in the homes of those with influenza. These practices are also described on the CDC influenza Web site.6

References

1. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333-1340.

2. CDC. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza–United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057-1062.

3. CDC. Summary* recommendations: prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—(ACIP)—United States, 2013-14. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm. Accessed August 9, 2013.

4. CDC. Interim adjusted estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness–United States, February 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:119-123.

5. CDC. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR01):1-24. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6001a1.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

6. CDC. Infection control in health care facilities. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/index.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

Lung cancer screening: The USPSTF's latest proposal

Influenza: Update for the 2013-2014 season

Each year in late summer, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) publishes its recommendations for the prevention of influenza for the upcoming season. The severity of each influenza season varies and is difficult to predict, which underscores the need to provide maximal vaccine coverage for at-risk patient populations.

Hoping for the best, planning for the worst. Over the past several decades the annual number of influenza-related hospitalizations has varied from approximately 55,000 to 431,000,1 and the number of deaths from influenza has been as low as 3349 and as high as 48,614.2 Infection rates are usually highest in children. Complications, hospitalizations, and deaths are highest in those ≥65 years, children<2 years, and patients with medical conditions known to increase risk for influenza complications. Those at high risk of complications appear in TABLE 1.3 The main recommendations for this coming year are the same as last year, including vaccinating everyone ≥6 months of age without a contraindication, starting vaccinations as soon as vaccine is available, and continuing throughout the influenza season for those who need it.

What’s new this year

An increasing number of influenza vaccine products are available; although to date, their effectiveness (which was determined to be 56% for all vaccines used last influenza season) 4 remains below what we would hope for. The CDC’s recommendations address these new types of vaccines, including ones that have 4 antigens instead of 3, and use new terminology to describe the vaccines.3

New terminology reflects changing vaccine formulations. Last influenza season there were 2 major categories of influenza vaccines: live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV). All products were produced using egg-culture methods and contained 2 influenza A antigen subtypes and 1 B subtype. Several products this year include 4 antigens (2 A subtypes and 2 B subtypes), and some are now produced with non–eggculture methods. This has led to a new system of classification, with the term inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) replacing TIV. TABLE 2 lists the influenza vaccine categories and abbreviations. TABLE 3 lists the contraindications for the different vaccine types.3

The new products include Flumist Quadrivalent (MedImmune), a quadrivalent LAIV (LAIV4); Fluarix Quadrivalent (GlaxoSmithKline), a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4); Flucelvax (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics), a cell culture-based trivalent IIV (ccIIV3); and FluBlok (Protein Sciences), a trivalent recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine (RIV3). Fluzone (Sanofi Pasteur), introduced last season in a trivalent formulation, is also available this season as a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4). As a group, influenza vaccine products now offer 3 routes of administration: intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intranasal. There is currently no evidence that any route offers an advantage over another, and the CDC states no preference for any particular product or route of administration.

Mercury content is not a problem

Even though there is no scientific controversy over the safety of the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal, some patients still have doubts and may ask for a thimerosalfree product. The only influenza products that contain any thimerosal are those that come in multidose vials. A description of each influenza vaccine product, including thimerosal content, indicated ages, and routes of administration, can be found on the CDC’s Web site3 (http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).

Options for those with egg allergy

There is now a product, RIV3 (FluBlok), that is manufactured without the use of eggs. It can be used in those 18 to 49 years of age with a history of egg allergy of any severity. Since 2011, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended that individuals with a history of mild egg allergy (those who experience only hives after egg exposure) may receive IIV, with additional safety precautions. Do not delay vaccination for these individuals if RIV is unavailable. Because of a lack of data demonstrating safety of LAIV for individuals with egg allergy, those allergic to eggs should receive RIV or IIV rather than LAIV.

Though the new ccIIV product, Flucelvax, is manufactured without the use of eggs, the seed viruses used to create the vaccine have been processed in eggs. The egg protein content in the vaccine is extremely low (<50 femtograms [5 × 10-14 g] per 0.5-mL dose), but the CDC does not consider it egg free. The FIGURE depicts the recommendations for those with a history of egg allergy.3

Other interventions for influenza prevention

Vaccination is only one tool available to prevent morbidity and mortality from influenza. Antiviral chemoprevention and treatment, and infection control practices can also be effective.

Antiviral chemoprevention is available for both pre- and post-exposure administration. In the past few years, the CDC has de-emphasized such use of antivirals for these indications out of concern for the supply of these agents and for the possibility that their use might lead to increased rates of viral resistance. Consider antiviral chemoprevention for those who have conditions that place them at risk for complications, and for those who are unvaccinated if they are at high risk for exposure to influenza (preexposure prophylaxis) or have been exposed (postexposure prophylaxis), if the medication can be started within 48 hours of exposure. Another option for unvaccinated high-risk patients is vigilant symptom monitoring with early treatment for influenza symptoms. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended in addition to vaccination to control influenza outbreaks at institutions that house patients at high risk for complications of influenza. Details on recommended antivirals including doses and duration of treatment can be found in a 2011 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.5

Antiviral treatment. The CDC recommends antiviral treatment for anyone with suspected or confirmed influenza who has progressive, severe, or complicated illness or is hospitalized for their illness.5 Treatment is also recommended for outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are at higher risk for influenza complications. This latter group includes those in TABLE 1, particularly children 6 to 59 months and adults ≥50 years. Start antiviral treatment within 48 hours of the first symptoms. For hospitalized patients, however, begin treatment at any point regardless of duration of illness.

Infection control practices can prevent the spread of influenza in the health care setting and in the homes of those with influenza. These practices are also described on the CDC influenza Web site.6

1. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333-1340.

2. CDC. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza–United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057-1062.

3. CDC. Summary* recommendations: prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—(ACIP)—United States, 2013-14. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/ acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm. Accessed August 9, 2013.

4. CDC. Interim adjusted estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:119-123.

5. CDC. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR01):1-24. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6001a1. htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

6. CDC. Infection control in health care facilities. Available at:http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/index.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

Each year in late summer, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) publishes its recommendations for the prevention of influenza for the upcoming season. The severity of each influenza season varies and is difficult to predict, which underscores the need to provide maximal vaccine coverage for at-risk patient populations.

Hoping for the best, planning for the worst. Over the past several decades the annual number of influenza-related hospitalizations has varied from approximately 55,000 to 431,000,1 and the number of deaths from influenza has been as low as 3349 and as high as 48,614.2 Infection rates are usually highest in children. Complications, hospitalizations, and deaths are highest in those ≥65 years, children<2 years, and patients with medical conditions known to increase risk for influenza complications. Those at high risk of complications appear in TABLE 1.3 The main recommendations for this coming year are the same as last year, including vaccinating everyone ≥6 months of age without a contraindication, starting vaccinations as soon as vaccine is available, and continuing throughout the influenza season for those who need it.

What’s new this year

An increasing number of influenza vaccine products are available; although to date, their effectiveness (which was determined to be 56% for all vaccines used last influenza season) 4 remains below what we would hope for. The CDC’s recommendations address these new types of vaccines, including ones that have 4 antigens instead of 3, and use new terminology to describe the vaccines.3

New terminology reflects changing vaccine formulations. Last influenza season there were 2 major categories of influenza vaccines: live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV). All products were produced using egg-culture methods and contained 2 influenza A antigen subtypes and 1 B subtype. Several products this year include 4 antigens (2 A subtypes and 2 B subtypes), and some are now produced with non–eggculture methods. This has led to a new system of classification, with the term inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) replacing TIV. TABLE 2 lists the influenza vaccine categories and abbreviations. TABLE 3 lists the contraindications for the different vaccine types.3

The new products include Flumist Quadrivalent (MedImmune), a quadrivalent LAIV (LAIV4); Fluarix Quadrivalent (GlaxoSmithKline), a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4); Flucelvax (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics), a cell culture-based trivalent IIV (ccIIV3); and FluBlok (Protein Sciences), a trivalent recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine (RIV3). Fluzone (Sanofi Pasteur), introduced last season in a trivalent formulation, is also available this season as a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4). As a group, influenza vaccine products now offer 3 routes of administration: intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intranasal. There is currently no evidence that any route offers an advantage over another, and the CDC states no preference for any particular product or route of administration.

Mercury content is not a problem

Even though there is no scientific controversy over the safety of the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal, some patients still have doubts and may ask for a thimerosalfree product. The only influenza products that contain any thimerosal are those that come in multidose vials. A description of each influenza vaccine product, including thimerosal content, indicated ages, and routes of administration, can be found on the CDC’s Web site3 (http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).

Options for those with egg allergy

There is now a product, RIV3 (FluBlok), that is manufactured without the use of eggs. It can be used in those 18 to 49 years of age with a history of egg allergy of any severity. Since 2011, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended that individuals with a history of mild egg allergy (those who experience only hives after egg exposure) may receive IIV, with additional safety precautions. Do not delay vaccination for these individuals if RIV is unavailable. Because of a lack of data demonstrating safety of LAIV for individuals with egg allergy, those allergic to eggs should receive RIV or IIV rather than LAIV.

Though the new ccIIV product, Flucelvax, is manufactured without the use of eggs, the seed viruses used to create the vaccine have been processed in eggs. The egg protein content in the vaccine is extremely low (<50 femtograms [5 × 10-14 g] per 0.5-mL dose), but the CDC does not consider it egg free. The FIGURE depicts the recommendations for those with a history of egg allergy.3

Other interventions for influenza prevention

Vaccination is only one tool available to prevent morbidity and mortality from influenza. Antiviral chemoprevention and treatment, and infection control practices can also be effective.

Antiviral chemoprevention is available for both pre- and post-exposure administration. In the past few years, the CDC has de-emphasized such use of antivirals for these indications out of concern for the supply of these agents and for the possibility that their use might lead to increased rates of viral resistance. Consider antiviral chemoprevention for those who have conditions that place them at risk for complications, and for those who are unvaccinated if they are at high risk for exposure to influenza (preexposure prophylaxis) or have been exposed (postexposure prophylaxis), if the medication can be started within 48 hours of exposure. Another option for unvaccinated high-risk patients is vigilant symptom monitoring with early treatment for influenza symptoms. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended in addition to vaccination to control influenza outbreaks at institutions that house patients at high risk for complications of influenza. Details on recommended antivirals including doses and duration of treatment can be found in a 2011 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.5

Antiviral treatment. The CDC recommends antiviral treatment for anyone with suspected or confirmed influenza who has progressive, severe, or complicated illness or is hospitalized for their illness.5 Treatment is also recommended for outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are at higher risk for influenza complications. This latter group includes those in TABLE 1, particularly children 6 to 59 months and adults ≥50 years. Start antiviral treatment within 48 hours of the first symptoms. For hospitalized patients, however, begin treatment at any point regardless of duration of illness.

Infection control practices can prevent the spread of influenza in the health care setting and in the homes of those with influenza. These practices are also described on the CDC influenza Web site.6

Each year in late summer, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) publishes its recommendations for the prevention of influenza for the upcoming season. The severity of each influenza season varies and is difficult to predict, which underscores the need to provide maximal vaccine coverage for at-risk patient populations.

Hoping for the best, planning for the worst. Over the past several decades the annual number of influenza-related hospitalizations has varied from approximately 55,000 to 431,000,1 and the number of deaths from influenza has been as low as 3349 and as high as 48,614.2 Infection rates are usually highest in children. Complications, hospitalizations, and deaths are highest in those ≥65 years, children<2 years, and patients with medical conditions known to increase risk for influenza complications. Those at high risk of complications appear in TABLE 1.3 The main recommendations for this coming year are the same as last year, including vaccinating everyone ≥6 months of age without a contraindication, starting vaccinations as soon as vaccine is available, and continuing throughout the influenza season for those who need it.

What’s new this year

An increasing number of influenza vaccine products are available; although to date, their effectiveness (which was determined to be 56% for all vaccines used last influenza season) 4 remains below what we would hope for. The CDC’s recommendations address these new types of vaccines, including ones that have 4 antigens instead of 3, and use new terminology to describe the vaccines.3

New terminology reflects changing vaccine formulations. Last influenza season there were 2 major categories of influenza vaccines: live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV). All products were produced using egg-culture methods and contained 2 influenza A antigen subtypes and 1 B subtype. Several products this year include 4 antigens (2 A subtypes and 2 B subtypes), and some are now produced with non–eggculture methods. This has led to a new system of classification, with the term inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) replacing TIV. TABLE 2 lists the influenza vaccine categories and abbreviations. TABLE 3 lists the contraindications for the different vaccine types.3

The new products include Flumist Quadrivalent (MedImmune), a quadrivalent LAIV (LAIV4); Fluarix Quadrivalent (GlaxoSmithKline), a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4); Flucelvax (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics), a cell culture-based trivalent IIV (ccIIV3); and FluBlok (Protein Sciences), a trivalent recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine (RIV3). Fluzone (Sanofi Pasteur), introduced last season in a trivalent formulation, is also available this season as a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4). As a group, influenza vaccine products now offer 3 routes of administration: intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intranasal. There is currently no evidence that any route offers an advantage over another, and the CDC states no preference for any particular product or route of administration.

Mercury content is not a problem

Even though there is no scientific controversy over the safety of the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal, some patients still have doubts and may ask for a thimerosalfree product. The only influenza products that contain any thimerosal are those that come in multidose vials. A description of each influenza vaccine product, including thimerosal content, indicated ages, and routes of administration, can be found on the CDC’s Web site3 (http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).

Options for those with egg allergy

There is now a product, RIV3 (FluBlok), that is manufactured without the use of eggs. It can be used in those 18 to 49 years of age with a history of egg allergy of any severity. Since 2011, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended that individuals with a history of mild egg allergy (those who experience only hives after egg exposure) may receive IIV, with additional safety precautions. Do not delay vaccination for these individuals if RIV is unavailable. Because of a lack of data demonstrating safety of LAIV for individuals with egg allergy, those allergic to eggs should receive RIV or IIV rather than LAIV.

Though the new ccIIV product, Flucelvax, is manufactured without the use of eggs, the seed viruses used to create the vaccine have been processed in eggs. The egg protein content in the vaccine is extremely low (<50 femtograms [5 × 10-14 g] per 0.5-mL dose), but the CDC does not consider it egg free. The FIGURE depicts the recommendations for those with a history of egg allergy.3

Other interventions for influenza prevention

Vaccination is only one tool available to prevent morbidity and mortality from influenza. Antiviral chemoprevention and treatment, and infection control practices can also be effective.

Antiviral chemoprevention is available for both pre- and post-exposure administration. In the past few years, the CDC has de-emphasized such use of antivirals for these indications out of concern for the supply of these agents and for the possibility that their use might lead to increased rates of viral resistance. Consider antiviral chemoprevention for those who have conditions that place them at risk for complications, and for those who are unvaccinated if they are at high risk for exposure to influenza (preexposure prophylaxis) or have been exposed (postexposure prophylaxis), if the medication can be started within 48 hours of exposure. Another option for unvaccinated high-risk patients is vigilant symptom monitoring with early treatment for influenza symptoms. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended in addition to vaccination to control influenza outbreaks at institutions that house patients at high risk for complications of influenza. Details on recommended antivirals including doses and duration of treatment can be found in a 2011 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.5

Antiviral treatment. The CDC recommends antiviral treatment for anyone with suspected or confirmed influenza who has progressive, severe, or complicated illness or is hospitalized for their illness.5 Treatment is also recommended for outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are at higher risk for influenza complications. This latter group includes those in TABLE 1, particularly children 6 to 59 months and adults ≥50 years. Start antiviral treatment within 48 hours of the first symptoms. For hospitalized patients, however, begin treatment at any point regardless of duration of illness.

Infection control practices can prevent the spread of influenza in the health care setting and in the homes of those with influenza. These practices are also described on the CDC influenza Web site.6

1. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333-1340.

2. CDC. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza–United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057-1062.

3. CDC. Summary* recommendations: prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—(ACIP)—United States, 2013-14. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/ acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm. Accessed August 9, 2013.

4. CDC. Interim adjusted estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:119-123.

5. CDC. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR01):1-24. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6001a1. htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

6. CDC. Infection control in health care facilities. Available at:http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/index.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

1. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333-1340.

2. CDC. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza–United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057-1062.

3. CDC. Summary* recommendations: prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—(ACIP)—United States, 2013-14. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/ acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm. Accessed August 9, 2013.

4. CDC. Interim adjusted estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:119-123.

5. CDC. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR01):1-24. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6001a1. htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

6. CDC. Infection control in health care facilities. Available at:http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/index.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

Vitamin D: When it helps, when it harms

Vitamin D is the new wonder cure and preventive for all kinds of ailments and chronic diseases. Or so it would seem from the popular press and Internet.1

But what do we actually know about the health benefits of vitamin D? Should we be screening patients for vitamin D deficiency? How much vitamin D should our patients consume daily? This Practice Alert answers these questions.

Vitamin D basics

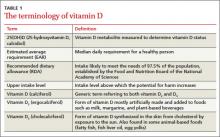

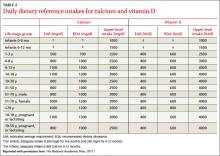

Vitamin D is synthesized in the skin from cholesterol through sun exposure (vitamin D3) and consumed in food fortified with vitamin D2, such as milk, yogurt, and orange juice, or food that contains vitamin D3 (fatty fish and eggs). Both forms of vitamin D are inactive until metabolized in the liver to 25(OH)D (TABLE 1), which is further metabolized in the kidney to the biologically active calcitriol. The 25(OH)D circulates in the blood with a vitamin D–binding protein and is the basis of measurement of serum vitamin D levels.

The terminology of vitamin D