User login

The 2014-2015 Influenza Season: What You Need to Know

As clinicians and the CDC prepare for the upcoming influenza season, many of the immunization recommendations remain unchanged from last season. Vaccination continues to be recommended for everyone ages 6 months and older. However, for the first time, a specific vaccine is preferred for children ages 2 through 8 years. Here’s what you need to know about this change, as well as how to handle vaccination in patients who are, or might be, allergic to eggs.

USE LAIV FOR KIDS AGES 2 THROUGH 8 (IF AVAILABLE)

For the first time, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has stated a preference for a specific influenza vaccine for a specific age-group. It recommends using the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), which is a nasal spray, for children ages 2 through 8 years.1

A systematic review found evidence of increased efficacy of LAIV compared to inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in this age-group; both types of vaccine have similar rates of adverse reactions.2 This increased effectiveness results in 46 fewer cases of confirmed influenza per 1,000 children vaccinated (number needed to treat, 24). Although the evidence of LAIV’s increased effectiveness was found for children ages 2 to 6 years, ACIP extended this recommendation through age 8 because this is the age through which clinicians need to consider two doses of vaccine for a child previously unvaccinated with the influenza vaccine. Children younger than 2 should receive IIV3 or IIV4.3

ACIP realizes that due to programmatic constraints it would be difficult to vaccinate all children with LAIV this year; the committee emphasizes that this recommendation should be implemented when feasible this year but no later than the 2015-2016 influenza season. IIV is effective in children and should be given if LAIV is not available or is contraindicated. Vaccination should not be delayed in the hopes of receiving a supply of LAIV if IIV is available.1

LAIV should not be used in children younger than 2 or adults older than 49. This vaccine is contraindicated in children and adolescents who are taking chronic aspirin therapy, pregnant women, or persons who are immunosuppressed, have a history of egg allergy, or have taken influenza antiviral medications in the past 48 hours.1 LAIV also is not recommended for children ages 2 through 4 years who have asthma or have had a wheezing episode in the past 12 months.1

There are precautions for the use of LAIV in patients with chronic medical conditions that can place them at high risk for complications from influenza. These include chronic lung, heart, renal, neurologic, liver, blood, or metabolic disorders—particularly, asthma and diabetes.1

WHICH VACCINE FOR PATIENTS WHO ARE ALLERGIC TO EGGS?

Two influenza vaccines are now available that are not prepared in embryonated eggs: recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV3) and cell culture–based inactivated influenza vaccine (ccIIV3). Both are trivalent products that contain antigens from two influenza A viruses and one influenza B virus; they were introduced in time for the 2013-2014 flu season. The RIV3 is considered egg-free but ccIIV3 is not, although the amount of egg protein in the latter is miniscule (estimated at 5 × 10-8 mg/0.5 mL dose).1 Neither product is licensed for use in children younger than 18, and RIV3 is licensed only for those ages 18 through 49.

Patients who experience only hives after egg exposure can receive any of the flu vaccines except LAIV—and only because of a lack of data on this product, not because it has been shown to be less safe than the other vaccines. Patients who are unsure if they have an egg allergy or who only get hives when they eat eggs should be observed for at least 30 minutes1 following injection as a precaution. Those ages 18 through 49 who have a history of severe reactions to eggs should receive RIV3. Patients younger than 18 and older than 49 can receive IIV vaccines approved for their specific age-group.

Any patient who is severely allergic but who cannot receive an egg-free vaccine should be vaccinated by a clinician with experience managing severe allergic conditions. Although severe anaphylactic reactions to influenza vaccine are very rare, clinicians should be equipped and prepared to respond to a severe allergic reaction after providing influenza vaccine to anyone with a history of egg allergy.

Continue for additional tips and resources >>

ADDITIONAL TIPS AND RESOURCES

In addition to the LAIV, RIV3, and ccIIV3 vaccines described here, 10 other vaccines are available: five egg-based IIV3 products in standard-dose form, one IIV3 vaccine for intradermal use, one high-dose IIV3 product for patients ages 65 or older, and three standard-dose IIV4 products. More details on each of these vaccines are available on the CDC website (www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6207a1.htm?s_cid=rr6207a1_w#Tab1).

Regardless of which type of flu vaccine they receive, children ages 6 months through 8 years should receive two doses, at least four weeks apart, unless they received

• One dose during the 2013-2014 season, or

• Two or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine since July 2010, or

• Two or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine before July 2010 and at least one dose of monovalent H1N1 vaccine, or

• At least one dose of seasonal influenza vaccine prior to July 2010 and one or more after.

Vaccine effectiveness. The CDC estimated that vaccine effectiveness during the 2013-2014 flu season was 66%.3 While this degree of effectiveness is important for minimizing morbidity and mortality from influenza each year, it’s important to appreciate the limitations of the vaccine and not rely on it as the only preventive intervention.

Other forms of prevention. We need to advise and practice good respiratory hygiene, frequent hand washing, self-isolation when sick, effective infection control practices at health care facilities, targeted early treatment with antivirals, and targeted pre- and postexposure antiviral chemoprevention. Details on each of these interventions, including recommendations on the use of antiviral medications, can be found on the CDC website (www.cdc.gov/flu).

REFERENCES

1. Grohskopf LA, Olsen SJ, Sokolow LZ, et al; Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States 2014-2015 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63: 691-697.

2. Grohskopf L, Olsen S, Sokolow L. Effectiveness of live-attenuated vs inactivated influenza vaccines for healthy children. Presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/05-Flu-Grohskopf.pdf. Accessed October 19, 2014.

3. Flannery B. Interim estimates of 2013-14 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness. Presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/04-Flu-Flannery.pdf. Accessed October 19, 2014.

As clinicians and the CDC prepare for the upcoming influenza season, many of the immunization recommendations remain unchanged from last season. Vaccination continues to be recommended for everyone ages 6 months and older. However, for the first time, a specific vaccine is preferred for children ages 2 through 8 years. Here’s what you need to know about this change, as well as how to handle vaccination in patients who are, or might be, allergic to eggs.

USE LAIV FOR KIDS AGES 2 THROUGH 8 (IF AVAILABLE)

For the first time, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has stated a preference for a specific influenza vaccine for a specific age-group. It recommends using the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), which is a nasal spray, for children ages 2 through 8 years.1

A systematic review found evidence of increased efficacy of LAIV compared to inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in this age-group; both types of vaccine have similar rates of adverse reactions.2 This increased effectiveness results in 46 fewer cases of confirmed influenza per 1,000 children vaccinated (number needed to treat, 24). Although the evidence of LAIV’s increased effectiveness was found for children ages 2 to 6 years, ACIP extended this recommendation through age 8 because this is the age through which clinicians need to consider two doses of vaccine for a child previously unvaccinated with the influenza vaccine. Children younger than 2 should receive IIV3 or IIV4.3

ACIP realizes that due to programmatic constraints it would be difficult to vaccinate all children with LAIV this year; the committee emphasizes that this recommendation should be implemented when feasible this year but no later than the 2015-2016 influenza season. IIV is effective in children and should be given if LAIV is not available or is contraindicated. Vaccination should not be delayed in the hopes of receiving a supply of LAIV if IIV is available.1

LAIV should not be used in children younger than 2 or adults older than 49. This vaccine is contraindicated in children and adolescents who are taking chronic aspirin therapy, pregnant women, or persons who are immunosuppressed, have a history of egg allergy, or have taken influenza antiviral medications in the past 48 hours.1 LAIV also is not recommended for children ages 2 through 4 years who have asthma or have had a wheezing episode in the past 12 months.1

There are precautions for the use of LAIV in patients with chronic medical conditions that can place them at high risk for complications from influenza. These include chronic lung, heart, renal, neurologic, liver, blood, or metabolic disorders—particularly, asthma and diabetes.1

WHICH VACCINE FOR PATIENTS WHO ARE ALLERGIC TO EGGS?

Two influenza vaccines are now available that are not prepared in embryonated eggs: recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV3) and cell culture–based inactivated influenza vaccine (ccIIV3). Both are trivalent products that contain antigens from two influenza A viruses and one influenza B virus; they were introduced in time for the 2013-2014 flu season. The RIV3 is considered egg-free but ccIIV3 is not, although the amount of egg protein in the latter is miniscule (estimated at 5 × 10-8 mg/0.5 mL dose).1 Neither product is licensed for use in children younger than 18, and RIV3 is licensed only for those ages 18 through 49.

Patients who experience only hives after egg exposure can receive any of the flu vaccines except LAIV—and only because of a lack of data on this product, not because it has been shown to be less safe than the other vaccines. Patients who are unsure if they have an egg allergy or who only get hives when they eat eggs should be observed for at least 30 minutes1 following injection as a precaution. Those ages 18 through 49 who have a history of severe reactions to eggs should receive RIV3. Patients younger than 18 and older than 49 can receive IIV vaccines approved for their specific age-group.

Any patient who is severely allergic but who cannot receive an egg-free vaccine should be vaccinated by a clinician with experience managing severe allergic conditions. Although severe anaphylactic reactions to influenza vaccine are very rare, clinicians should be equipped and prepared to respond to a severe allergic reaction after providing influenza vaccine to anyone with a history of egg allergy.

Continue for additional tips and resources >>

ADDITIONAL TIPS AND RESOURCES

In addition to the LAIV, RIV3, and ccIIV3 vaccines described here, 10 other vaccines are available: five egg-based IIV3 products in standard-dose form, one IIV3 vaccine for intradermal use, one high-dose IIV3 product for patients ages 65 or older, and three standard-dose IIV4 products. More details on each of these vaccines are available on the CDC website (www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6207a1.htm?s_cid=rr6207a1_w#Tab1).

Regardless of which type of flu vaccine they receive, children ages 6 months through 8 years should receive two doses, at least four weeks apart, unless they received

• One dose during the 2013-2014 season, or

• Two or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine since July 2010, or

• Two or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine before July 2010 and at least one dose of monovalent H1N1 vaccine, or

• At least one dose of seasonal influenza vaccine prior to July 2010 and one or more after.

Vaccine effectiveness. The CDC estimated that vaccine effectiveness during the 2013-2014 flu season was 66%.3 While this degree of effectiveness is important for minimizing morbidity and mortality from influenza each year, it’s important to appreciate the limitations of the vaccine and not rely on it as the only preventive intervention.

Other forms of prevention. We need to advise and practice good respiratory hygiene, frequent hand washing, self-isolation when sick, effective infection control practices at health care facilities, targeted early treatment with antivirals, and targeted pre- and postexposure antiviral chemoprevention. Details on each of these interventions, including recommendations on the use of antiviral medications, can be found on the CDC website (www.cdc.gov/flu).

REFERENCES

1. Grohskopf LA, Olsen SJ, Sokolow LZ, et al; Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States 2014-2015 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63: 691-697.

2. Grohskopf L, Olsen S, Sokolow L. Effectiveness of live-attenuated vs inactivated influenza vaccines for healthy children. Presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/05-Flu-Grohskopf.pdf. Accessed October 19, 2014.

3. Flannery B. Interim estimates of 2013-14 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness. Presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/04-Flu-Flannery.pdf. Accessed October 19, 2014.

As clinicians and the CDC prepare for the upcoming influenza season, many of the immunization recommendations remain unchanged from last season. Vaccination continues to be recommended for everyone ages 6 months and older. However, for the first time, a specific vaccine is preferred for children ages 2 through 8 years. Here’s what you need to know about this change, as well as how to handle vaccination in patients who are, or might be, allergic to eggs.

USE LAIV FOR KIDS AGES 2 THROUGH 8 (IF AVAILABLE)

For the first time, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has stated a preference for a specific influenza vaccine for a specific age-group. It recommends using the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), which is a nasal spray, for children ages 2 through 8 years.1

A systematic review found evidence of increased efficacy of LAIV compared to inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in this age-group; both types of vaccine have similar rates of adverse reactions.2 This increased effectiveness results in 46 fewer cases of confirmed influenza per 1,000 children vaccinated (number needed to treat, 24). Although the evidence of LAIV’s increased effectiveness was found for children ages 2 to 6 years, ACIP extended this recommendation through age 8 because this is the age through which clinicians need to consider two doses of vaccine for a child previously unvaccinated with the influenza vaccine. Children younger than 2 should receive IIV3 or IIV4.3

ACIP realizes that due to programmatic constraints it would be difficult to vaccinate all children with LAIV this year; the committee emphasizes that this recommendation should be implemented when feasible this year but no later than the 2015-2016 influenza season. IIV is effective in children and should be given if LAIV is not available or is contraindicated. Vaccination should not be delayed in the hopes of receiving a supply of LAIV if IIV is available.1

LAIV should not be used in children younger than 2 or adults older than 49. This vaccine is contraindicated in children and adolescents who are taking chronic aspirin therapy, pregnant women, or persons who are immunosuppressed, have a history of egg allergy, or have taken influenza antiviral medications in the past 48 hours.1 LAIV also is not recommended for children ages 2 through 4 years who have asthma or have had a wheezing episode in the past 12 months.1

There are precautions for the use of LAIV in patients with chronic medical conditions that can place them at high risk for complications from influenza. These include chronic lung, heart, renal, neurologic, liver, blood, or metabolic disorders—particularly, asthma and diabetes.1

WHICH VACCINE FOR PATIENTS WHO ARE ALLERGIC TO EGGS?

Two influenza vaccines are now available that are not prepared in embryonated eggs: recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV3) and cell culture–based inactivated influenza vaccine (ccIIV3). Both are trivalent products that contain antigens from two influenza A viruses and one influenza B virus; they were introduced in time for the 2013-2014 flu season. The RIV3 is considered egg-free but ccIIV3 is not, although the amount of egg protein in the latter is miniscule (estimated at 5 × 10-8 mg/0.5 mL dose).1 Neither product is licensed for use in children younger than 18, and RIV3 is licensed only for those ages 18 through 49.

Patients who experience only hives after egg exposure can receive any of the flu vaccines except LAIV—and only because of a lack of data on this product, not because it has been shown to be less safe than the other vaccines. Patients who are unsure if they have an egg allergy or who only get hives when they eat eggs should be observed for at least 30 minutes1 following injection as a precaution. Those ages 18 through 49 who have a history of severe reactions to eggs should receive RIV3. Patients younger than 18 and older than 49 can receive IIV vaccines approved for their specific age-group.

Any patient who is severely allergic but who cannot receive an egg-free vaccine should be vaccinated by a clinician with experience managing severe allergic conditions. Although severe anaphylactic reactions to influenza vaccine are very rare, clinicians should be equipped and prepared to respond to a severe allergic reaction after providing influenza vaccine to anyone with a history of egg allergy.

Continue for additional tips and resources >>

ADDITIONAL TIPS AND RESOURCES

In addition to the LAIV, RIV3, and ccIIV3 vaccines described here, 10 other vaccines are available: five egg-based IIV3 products in standard-dose form, one IIV3 vaccine for intradermal use, one high-dose IIV3 product for patients ages 65 or older, and three standard-dose IIV4 products. More details on each of these vaccines are available on the CDC website (www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6207a1.htm?s_cid=rr6207a1_w#Tab1).

Regardless of which type of flu vaccine they receive, children ages 6 months through 8 years should receive two doses, at least four weeks apart, unless they received

• One dose during the 2013-2014 season, or

• Two or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine since July 2010, or

• Two or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine before July 2010 and at least one dose of monovalent H1N1 vaccine, or

• At least one dose of seasonal influenza vaccine prior to July 2010 and one or more after.

Vaccine effectiveness. The CDC estimated that vaccine effectiveness during the 2013-2014 flu season was 66%.3 While this degree of effectiveness is important for minimizing morbidity and mortality from influenza each year, it’s important to appreciate the limitations of the vaccine and not rely on it as the only preventive intervention.

Other forms of prevention. We need to advise and practice good respiratory hygiene, frequent hand washing, self-isolation when sick, effective infection control practices at health care facilities, targeted early treatment with antivirals, and targeted pre- and postexposure antiviral chemoprevention. Details on each of these interventions, including recommendations on the use of antiviral medications, can be found on the CDC website (www.cdc.gov/flu).

REFERENCES

1. Grohskopf LA, Olsen SJ, Sokolow LZ, et al; Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States 2014-2015 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63: 691-697.

2. Grohskopf L, Olsen S, Sokolow L. Effectiveness of live-attenuated vs inactivated influenza vaccines for healthy children. Presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/05-Flu-Grohskopf.pdf. Accessed October 19, 2014.

3. Flannery B. Interim estimates of 2013-14 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness. Presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/04-Flu-Flannery.pdf. Accessed October 19, 2014.

Ebola: The facts FPs need to know

The 2014-2015 influenza season: What you need to know

As physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) prepare for the upcoming influenza season, many of the recommendations remain unchanged from last season. Vaccination continues to be recommended for everyone 6 months of age and older. However, for the first time, a specific vaccine is preferred for children ages 2 through 8 years. Here’s what you need to know about this change, as well as how to handle vaccination in patients who are, or might be, allergic to eggs.

Use LAIV for kids ages 2 through 8 (if available)

For the first time, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has stated a preference for a specific influenza vaccine for a specific age group. It recommends using the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), which is a nasal spray, for children ages 2 through 8 years.1

A systematic review found evidence of increased efficacy of LAIV compared to inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in this age group; both types of vaccine have similar rates of adverse reactions.2 This increased effectiveness results in 46 fewer cases of confirmed influenza per 1000 children vaccinated (number needed to treat=24). Although the evidence of LAIV’s increased effectiveness was found for children ages 2 to 6 years, ACIP extended this recommendation through age 8 because this is the age through which physicians need to consider 2 doses of vaccine for a child previously unvaccinated with the influenza vaccine. Children younger than age 2 should receive IIV3 or IIV4.3

ACIP realizes that due to programmatic constraints it would be difficult to vaccinate all children with LAIV this year and is emphasizing that it should be implemented when feasible this year but no later than the 2015 to 2016 influenza season. IIV is effective in children and should be given if LAIV is not available or is contraindicated. Vaccine should not be delayed in the hopes of receiving LAIV if IIV is available.1

LAIV should not be used in children <2 years or adults >49. This vaccine is contraindicated in children and adolescents who are taking chronic aspirin therapy, pregnant women, those who are immunosuppressed, those with a history of egg allergy, or those who have taken influenza antiviral medications in the past 48 hours.1 LAIV also is not recommended for children ages 2 through 4 years who have asthma or had a wheezing episode in the past 12 months.1

There are precautions for the use of LAIV in patients with chronic medical conditions that can place them at high risk for complications from influenza, such as chronic lung, heart, renal, neurologic, liver, blood, or metabolic disorders, including asthma and diabetes.1

Which vaccine for patients who are allergic to eggs?

Two influenza vaccines are now available that are not prepared in embryonated eggs: recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV3) and cell culture-based inactivated influenza vaccine (ccIIV3). Both are trivalent products that contain antigens from 2 influenza A viruses and one influenza B virus and were introduced in time for the 2013 to 2014 flu season. The RIV3 is considered egg-free but ccIIV3 is not, although the amount of egg protein in it is miniscule, estimated at 5 × 10-8 mcg/0.5 mL dose.1 Neither product is licensed for children younger than 18 years and RIV3 is licensed only for those ages 18 through 49 years.

Patients who experience only hives after egg exposure can receive any of the flu vaccines except LAIV, and only because of a lack of data on this product, not because it has been shown to be less safe than the other vaccines. Patients who are unsure if they have an egg allergy or only get hives when they eat eggs should be observed for at least 30 minutes1 following injection as a precaution. Those ages 18 through 49 who have a history of severe reactions to eggs should receive RIV3. Patients younger than 18 years of age and older than 49 years of age can receive IIV vaccines approved for their specific age group. Any patient who is severely allergic and who cannot receive an egg-free vaccine should be vaccinated by a physician with experience managing severe allergic conditions.

Although severe, anaphylactic reactions to influenza vaccine are very rare, physicians should be equipped and prepared to respond to a severe allergic reaction after providing influenza vaccine to anyone with a history of an egg allergy.

Additional tips and resources

In addition to the LAIV, RIV3, and ccIIV3 vaccines described here, 10 other vaccines are available, including 5 egg-based IIV3 products in standard-dose form, 1 IIV3 vaccine for intradermal use, 1 high-dose IIV3 product for patients ages 65 or older, and 3 standard-dose IIV4 products. More details on each of these vaccines are available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6207a1.htm?_%20cid=rr6207a1_w#Tab1.

Regardless of which type of flu vaccine they receive, children 6 months through 8 years should receive 2 doses, at least 4 weeks apart, unless they received:

- 1 dose in 2013 to 2014, or

- 2 or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine since July 2010, or

- 2 or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine before July 2010 and ≥1 dose of monovalent H1N1 vaccine, or

- at least 1 dose of seasonal influenza vaccine prior to July 2010 and ≥1 after.

Vaccine effectiveness. The CDC estimated that vaccine effectiveness during the 2013 to 2014 flu season was 66%.3 While this degree of effectiveness is important for minimizing the morbidity and mortality from influenza each year, it’s important to appreciate the limitations of the vaccine and not rely on it as the only prevention intervention.

Other forms of prevention. We need to advise and practice good respiratory hygiene, frequent hand washing, self-isolation when sick, effective infection control practices at health care facilities, targeted early treatment with antivirals, and targeted pre- and post-exposure antiviral chemoprevention. Details on each of these interventions, including recommendations on the use of antiviral medications, can be found on the CDC Web site at http://www.cdc.gov/flu.

1. Grohskopf LA, Olsen SJ, Sokolow LZ, et al; Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States 2014-2015 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:691-697.

2. Grohskopf L, Olsen S, Sokolow L. Effectiveness of live-attenuated vs inactivated influenza vaccines for healthy children. PowerPoint presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/05-Flu-Grohskopf.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2014.

3. Flannery B. Interim estimates of 2013-14 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness. PowerPoint presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/04-Flu-Flannery.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2014.

As physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) prepare for the upcoming influenza season, many of the recommendations remain unchanged from last season. Vaccination continues to be recommended for everyone 6 months of age and older. However, for the first time, a specific vaccine is preferred for children ages 2 through 8 years. Here’s what you need to know about this change, as well as how to handle vaccination in patients who are, or might be, allergic to eggs.

Use LAIV for kids ages 2 through 8 (if available)

For the first time, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has stated a preference for a specific influenza vaccine for a specific age group. It recommends using the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), which is a nasal spray, for children ages 2 through 8 years.1

A systematic review found evidence of increased efficacy of LAIV compared to inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in this age group; both types of vaccine have similar rates of adverse reactions.2 This increased effectiveness results in 46 fewer cases of confirmed influenza per 1000 children vaccinated (number needed to treat=24). Although the evidence of LAIV’s increased effectiveness was found for children ages 2 to 6 years, ACIP extended this recommendation through age 8 because this is the age through which physicians need to consider 2 doses of vaccine for a child previously unvaccinated with the influenza vaccine. Children younger than age 2 should receive IIV3 or IIV4.3

ACIP realizes that due to programmatic constraints it would be difficult to vaccinate all children with LAIV this year and is emphasizing that it should be implemented when feasible this year but no later than the 2015 to 2016 influenza season. IIV is effective in children and should be given if LAIV is not available or is contraindicated. Vaccine should not be delayed in the hopes of receiving LAIV if IIV is available.1

LAIV should not be used in children <2 years or adults >49. This vaccine is contraindicated in children and adolescents who are taking chronic aspirin therapy, pregnant women, those who are immunosuppressed, those with a history of egg allergy, or those who have taken influenza antiviral medications in the past 48 hours.1 LAIV also is not recommended for children ages 2 through 4 years who have asthma or had a wheezing episode in the past 12 months.1

There are precautions for the use of LAIV in patients with chronic medical conditions that can place them at high risk for complications from influenza, such as chronic lung, heart, renal, neurologic, liver, blood, or metabolic disorders, including asthma and diabetes.1

Which vaccine for patients who are allergic to eggs?

Two influenza vaccines are now available that are not prepared in embryonated eggs: recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV3) and cell culture-based inactivated influenza vaccine (ccIIV3). Both are trivalent products that contain antigens from 2 influenza A viruses and one influenza B virus and were introduced in time for the 2013 to 2014 flu season. The RIV3 is considered egg-free but ccIIV3 is not, although the amount of egg protein in it is miniscule, estimated at 5 × 10-8 mcg/0.5 mL dose.1 Neither product is licensed for children younger than 18 years and RIV3 is licensed only for those ages 18 through 49 years.

Patients who experience only hives after egg exposure can receive any of the flu vaccines except LAIV, and only because of a lack of data on this product, not because it has been shown to be less safe than the other vaccines. Patients who are unsure if they have an egg allergy or only get hives when they eat eggs should be observed for at least 30 minutes1 following injection as a precaution. Those ages 18 through 49 who have a history of severe reactions to eggs should receive RIV3. Patients younger than 18 years of age and older than 49 years of age can receive IIV vaccines approved for their specific age group. Any patient who is severely allergic and who cannot receive an egg-free vaccine should be vaccinated by a physician with experience managing severe allergic conditions.

Although severe, anaphylactic reactions to influenza vaccine are very rare, physicians should be equipped and prepared to respond to a severe allergic reaction after providing influenza vaccine to anyone with a history of an egg allergy.

Additional tips and resources

In addition to the LAIV, RIV3, and ccIIV3 vaccines described here, 10 other vaccines are available, including 5 egg-based IIV3 products in standard-dose form, 1 IIV3 vaccine for intradermal use, 1 high-dose IIV3 product for patients ages 65 or older, and 3 standard-dose IIV4 products. More details on each of these vaccines are available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6207a1.htm?_%20cid=rr6207a1_w#Tab1.

Regardless of which type of flu vaccine they receive, children 6 months through 8 years should receive 2 doses, at least 4 weeks apart, unless they received:

- 1 dose in 2013 to 2014, or

- 2 or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine since July 2010, or

- 2 or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine before July 2010 and ≥1 dose of monovalent H1N1 vaccine, or

- at least 1 dose of seasonal influenza vaccine prior to July 2010 and ≥1 after.

Vaccine effectiveness. The CDC estimated that vaccine effectiveness during the 2013 to 2014 flu season was 66%.3 While this degree of effectiveness is important for minimizing the morbidity and mortality from influenza each year, it’s important to appreciate the limitations of the vaccine and not rely on it as the only prevention intervention.

Other forms of prevention. We need to advise and practice good respiratory hygiene, frequent hand washing, self-isolation when sick, effective infection control practices at health care facilities, targeted early treatment with antivirals, and targeted pre- and post-exposure antiviral chemoprevention. Details on each of these interventions, including recommendations on the use of antiviral medications, can be found on the CDC Web site at http://www.cdc.gov/flu.

As physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) prepare for the upcoming influenza season, many of the recommendations remain unchanged from last season. Vaccination continues to be recommended for everyone 6 months of age and older. However, for the first time, a specific vaccine is preferred for children ages 2 through 8 years. Here’s what you need to know about this change, as well as how to handle vaccination in patients who are, or might be, allergic to eggs.

Use LAIV for kids ages 2 through 8 (if available)

For the first time, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has stated a preference for a specific influenza vaccine for a specific age group. It recommends using the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), which is a nasal spray, for children ages 2 through 8 years.1

A systematic review found evidence of increased efficacy of LAIV compared to inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) in this age group; both types of vaccine have similar rates of adverse reactions.2 This increased effectiveness results in 46 fewer cases of confirmed influenza per 1000 children vaccinated (number needed to treat=24). Although the evidence of LAIV’s increased effectiveness was found for children ages 2 to 6 years, ACIP extended this recommendation through age 8 because this is the age through which physicians need to consider 2 doses of vaccine for a child previously unvaccinated with the influenza vaccine. Children younger than age 2 should receive IIV3 or IIV4.3

ACIP realizes that due to programmatic constraints it would be difficult to vaccinate all children with LAIV this year and is emphasizing that it should be implemented when feasible this year but no later than the 2015 to 2016 influenza season. IIV is effective in children and should be given if LAIV is not available or is contraindicated. Vaccine should not be delayed in the hopes of receiving LAIV if IIV is available.1

LAIV should not be used in children <2 years or adults >49. This vaccine is contraindicated in children and adolescents who are taking chronic aspirin therapy, pregnant women, those who are immunosuppressed, those with a history of egg allergy, or those who have taken influenza antiviral medications in the past 48 hours.1 LAIV also is not recommended for children ages 2 through 4 years who have asthma or had a wheezing episode in the past 12 months.1

There are precautions for the use of LAIV in patients with chronic medical conditions that can place them at high risk for complications from influenza, such as chronic lung, heart, renal, neurologic, liver, blood, or metabolic disorders, including asthma and diabetes.1

Which vaccine for patients who are allergic to eggs?

Two influenza vaccines are now available that are not prepared in embryonated eggs: recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV3) and cell culture-based inactivated influenza vaccine (ccIIV3). Both are trivalent products that contain antigens from 2 influenza A viruses and one influenza B virus and were introduced in time for the 2013 to 2014 flu season. The RIV3 is considered egg-free but ccIIV3 is not, although the amount of egg protein in it is miniscule, estimated at 5 × 10-8 mcg/0.5 mL dose.1 Neither product is licensed for children younger than 18 years and RIV3 is licensed only for those ages 18 through 49 years.

Patients who experience only hives after egg exposure can receive any of the flu vaccines except LAIV, and only because of a lack of data on this product, not because it has been shown to be less safe than the other vaccines. Patients who are unsure if they have an egg allergy or only get hives when they eat eggs should be observed for at least 30 minutes1 following injection as a precaution. Those ages 18 through 49 who have a history of severe reactions to eggs should receive RIV3. Patients younger than 18 years of age and older than 49 years of age can receive IIV vaccines approved for their specific age group. Any patient who is severely allergic and who cannot receive an egg-free vaccine should be vaccinated by a physician with experience managing severe allergic conditions.

Although severe, anaphylactic reactions to influenza vaccine are very rare, physicians should be equipped and prepared to respond to a severe allergic reaction after providing influenza vaccine to anyone with a history of an egg allergy.

Additional tips and resources

In addition to the LAIV, RIV3, and ccIIV3 vaccines described here, 10 other vaccines are available, including 5 egg-based IIV3 products in standard-dose form, 1 IIV3 vaccine for intradermal use, 1 high-dose IIV3 product for patients ages 65 or older, and 3 standard-dose IIV4 products. More details on each of these vaccines are available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6207a1.htm?_%20cid=rr6207a1_w#Tab1.

Regardless of which type of flu vaccine they receive, children 6 months through 8 years should receive 2 doses, at least 4 weeks apart, unless they received:

- 1 dose in 2013 to 2014, or

- 2 or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine since July 2010, or

- 2 or more doses of seasonal influenza vaccine before July 2010 and ≥1 dose of monovalent H1N1 vaccine, or

- at least 1 dose of seasonal influenza vaccine prior to July 2010 and ≥1 after.

Vaccine effectiveness. The CDC estimated that vaccine effectiveness during the 2013 to 2014 flu season was 66%.3 While this degree of effectiveness is important for minimizing the morbidity and mortality from influenza each year, it’s important to appreciate the limitations of the vaccine and not rely on it as the only prevention intervention.

Other forms of prevention. We need to advise and practice good respiratory hygiene, frequent hand washing, self-isolation when sick, effective infection control practices at health care facilities, targeted early treatment with antivirals, and targeted pre- and post-exposure antiviral chemoprevention. Details on each of these interventions, including recommendations on the use of antiviral medications, can be found on the CDC Web site at http://www.cdc.gov/flu.

1. Grohskopf LA, Olsen SJ, Sokolow LZ, et al; Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States 2014-2015 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:691-697.

2. Grohskopf L, Olsen S, Sokolow L. Effectiveness of live-attenuated vs inactivated influenza vaccines for healthy children. PowerPoint presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/05-Flu-Grohskopf.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2014.

3. Flannery B. Interim estimates of 2013-14 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness. PowerPoint presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/04-Flu-Flannery.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2014.

1. Grohskopf LA, Olsen SJ, Sokolow LZ, et al; Influenza Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, CDC. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States 2014-2015 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:691-697.

2. Grohskopf L, Olsen S, Sokolow L. Effectiveness of live-attenuated vs inactivated influenza vaccines for healthy children. PowerPoint presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/05-Flu-Grohskopf.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2014.

3. Flannery B. Interim estimates of 2013-14 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness. PowerPoint presented at: Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; February 26, 2014; Atlanta, GA. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-02/04-Flu-Flannery.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2014.

Diet, exercise, and CVD: When counseling makes the most sense

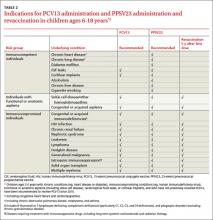

In the past 2 years, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has released 2 recommendations on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD). And it is proposing a third. The first recommendation, released in 2012, covered behavioral counseling on diet and physical activity to prevent CVD in individuals without documented CVD risks.1 The second recommendation, released earlier this year, covered the use of vitamins and mineral supplements to prevent CVD.2 A draft of the proposed third recommendation, which was posted for public review until early June, covers behavioral counseling to help adults with known CVD risk factors improve their diet and physical activity (TABLE).1-3

Counseling can influence behavior, but does it affect outcomes?

CVD is the leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for >596,000 deaths per year with an age-adjusted rate of 191.4 per 100,000.4 Age-adjusted CVD mortality has been declining for decades thanks to improved medical care and a reduction in smoking and other risk factors. It is well documented that adults who follow national recommendations for a healthy diet and levels of physical activity have lower rates of CVD and CVD mortality.1 The USPSTF agrees with the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) that everyone would benefit from a healthier diet and more exercise.5 However, the Task Force reviewed the evidence on behavioral counseling in the primary care setting and found that, for adults who do not have known CVD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes, even high-intensity behavioral counseling resulted in only a small benefit in intermediate outcomes, which would translate into very small population-wide improvements.

In the evidence report prepared by the Task Force, the intensity of counseling intervention was defined as low, medium, or high if it lasted, respectively, 1 to 30 minutes, 31 to 360 minutes, or ≥361 minutes. Low-intensity interventions involved brief counseling sessions performed by primary care clinicians or mailing educational materials to patients or both. Medium- and high-intensity interventions usually were conducted by health educators, nutritionists, or other professionals instead of primary care clinicians. These interventions improved patients’ consumption of a healthier diet and participation in physical activity, but yielded only modest reductions in body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), and lipid levels. Moreover, no direct evidence exists for improved CVD outcomes with these interventions.

The recent AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle modifications recommends that clinicians advise all adults on healthy dietary choices and exercise, based on the known benefits of these behaviors. The guideline developers recognized that the evidence for benefits appears in the highest risk groups, and they did not assess the evidence for effectiveness of behavioral counseling itself.6

The Task Force rationale for recommending counseling

In the draft of its third recommendation addressing those at highest risk for CVD, the Task Force does advise high-intensity behavioral counseling for those who are overweight or obese and who have other CVD risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or impaired fasting glucose levels. This proposed new recommendation replaces one from 2003 that advised intensive dietary counseling for those with CVD risks including hyperlipidemia. The draft focuses attention in primary care on those who are overweight or obese. It complements another Task Force recommendation to provide or to refer patients for intensive multicomponent behavioral interventions if they are obese, defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2.7

The Task Force cited 2 examples of behavioral interventions that can improve outcomes in those with CVD risks—the Diabetes Prevention Program and PREMIER, a set of interventions to lower BP.8,9 These programs have improved intermediate outcomes after 12 to 24 months, decreasing total cholesterol by 3 to 6 mg/dL and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by 1.5 to 5 mg/dL; systolic and diastolic BP by 1 to 3 mm Hg and 1 to 2 mm Hg, respectively; fasting glucose by 1 to 3 mg/dL; and weight by approximately 3 kg. The Task Force felt that while hard evidence is lacking for reducing CVD with counseling, epidemiologic studies demonstrate that, in those at high risk, reductions in CVD rates generally reflect the magnitude of improvement in intermediate measures.

Half of all adults in the United States have at least one documented CVD risk factor. But the potential benefit of behavioral counseling for those without documented CVD risks is relatively small. Rather than expending effort for only modest gain in the lower risk group, the Task Force recommends focusing on those with highest CVD risk. Thus the non-high risk group received a “C” recommendation, while the group of overweight and obese patients with other CVD risks received a “B” recommendation for essentially the same interventions. (For more on the grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.)

In addition to counseling...

The Task Force also recommends other interventions for the primary prevention of CVD:

- screening for and treating hypertension

- selectively screening for hyperlipidemia

- using aspirin to prevent CVD in those at high risk

- intensive counseling on weight management for those who are obese

- advising children and adolescents to avoid tobacco, and using brief interventions for tobacco cessation for smokers.

The recent Task Force recommendation on the use of vitamins, minerals, and multivitamins2 states that, while many adults take vitamin and mineral supplements in the belief that they prevent both heart disease and cancer, there is no evidence to support that belief. And there is good evidence that both β-carotene and vitamin E do not prevent disease. For other vitamins and minerals, singly or in combination, there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against their use.2

The Community Preventive Services Task Force—a separate expert panel established by the US Department of Health and Human Services to complement the USPSTF—makes recommendations on population-level interventions and has a series of recommendations on ways to improve the population’s nutrition and physical activity.10 These community-based interventions, if widely implemented, would probably yield greater improvements in healthy eating and increased activity levels than resource-intense clinical interventions based on individual patients with low risk.

1. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsphys.htm. Accessed May 21, 2014.

2. USPSTF. Vitamin, mineral, and multivitamin supplements for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf14/vitasupp/vitasuppfinalrs.htm. Accessed May 21, 2014.

3. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with known risk factors: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement (Draft). US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf13/cvdhighrisk/cvdhighriskdraftrec.htm. Accessed July 22, 2014.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. Natl Vital Stat Report. 2012;61:1-51.

5. Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard, JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Nov 12. [Epub ahead of print].

6. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; 2013 ACC/AHA Cholesterol Guideline Panel. Treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in adults: synopsis of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:339-343.

7. USPSTF. Screening for and management of obesity in adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsobes.htm. Accessed May 21, 2014.

8. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393-403.

9. Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, et al; PREMIER Collaborative Research Group. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-month results of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:485-495.

10. USPSTF. The Guide to Community Preventive Services. Community Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. Accessed May 21, 2014.

In the past 2 years, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has released 2 recommendations on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD). And it is proposing a third. The first recommendation, released in 2012, covered behavioral counseling on diet and physical activity to prevent CVD in individuals without documented CVD risks.1 The second recommendation, released earlier this year, covered the use of vitamins and mineral supplements to prevent CVD.2 A draft of the proposed third recommendation, which was posted for public review until early June, covers behavioral counseling to help adults with known CVD risk factors improve their diet and physical activity (TABLE).1-3

Counseling can influence behavior, but does it affect outcomes?

CVD is the leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for >596,000 deaths per year with an age-adjusted rate of 191.4 per 100,000.4 Age-adjusted CVD mortality has been declining for decades thanks to improved medical care and a reduction in smoking and other risk factors. It is well documented that adults who follow national recommendations for a healthy diet and levels of physical activity have lower rates of CVD and CVD mortality.1 The USPSTF agrees with the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) that everyone would benefit from a healthier diet and more exercise.5 However, the Task Force reviewed the evidence on behavioral counseling in the primary care setting and found that, for adults who do not have known CVD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes, even high-intensity behavioral counseling resulted in only a small benefit in intermediate outcomes, which would translate into very small population-wide improvements.

In the evidence report prepared by the Task Force, the intensity of counseling intervention was defined as low, medium, or high if it lasted, respectively, 1 to 30 minutes, 31 to 360 minutes, or ≥361 minutes. Low-intensity interventions involved brief counseling sessions performed by primary care clinicians or mailing educational materials to patients or both. Medium- and high-intensity interventions usually were conducted by health educators, nutritionists, or other professionals instead of primary care clinicians. These interventions improved patients’ consumption of a healthier diet and participation in physical activity, but yielded only modest reductions in body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), and lipid levels. Moreover, no direct evidence exists for improved CVD outcomes with these interventions.

The recent AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle modifications recommends that clinicians advise all adults on healthy dietary choices and exercise, based on the known benefits of these behaviors. The guideline developers recognized that the evidence for benefits appears in the highest risk groups, and they did not assess the evidence for effectiveness of behavioral counseling itself.6

The Task Force rationale for recommending counseling

In the draft of its third recommendation addressing those at highest risk for CVD, the Task Force does advise high-intensity behavioral counseling for those who are overweight or obese and who have other CVD risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or impaired fasting glucose levels. This proposed new recommendation replaces one from 2003 that advised intensive dietary counseling for those with CVD risks including hyperlipidemia. The draft focuses attention in primary care on those who are overweight or obese. It complements another Task Force recommendation to provide or to refer patients for intensive multicomponent behavioral interventions if they are obese, defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2.7

The Task Force cited 2 examples of behavioral interventions that can improve outcomes in those with CVD risks—the Diabetes Prevention Program and PREMIER, a set of interventions to lower BP.8,9 These programs have improved intermediate outcomes after 12 to 24 months, decreasing total cholesterol by 3 to 6 mg/dL and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by 1.5 to 5 mg/dL; systolic and diastolic BP by 1 to 3 mm Hg and 1 to 2 mm Hg, respectively; fasting glucose by 1 to 3 mg/dL; and weight by approximately 3 kg. The Task Force felt that while hard evidence is lacking for reducing CVD with counseling, epidemiologic studies demonstrate that, in those at high risk, reductions in CVD rates generally reflect the magnitude of improvement in intermediate measures.

Half of all adults in the United States have at least one documented CVD risk factor. But the potential benefit of behavioral counseling for those without documented CVD risks is relatively small. Rather than expending effort for only modest gain in the lower risk group, the Task Force recommends focusing on those with highest CVD risk. Thus the non-high risk group received a “C” recommendation, while the group of overweight and obese patients with other CVD risks received a “B” recommendation for essentially the same interventions. (For more on the grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.)

In addition to counseling...

The Task Force also recommends other interventions for the primary prevention of CVD:

- screening for and treating hypertension

- selectively screening for hyperlipidemia

- using aspirin to prevent CVD in those at high risk

- intensive counseling on weight management for those who are obese

- advising children and adolescents to avoid tobacco, and using brief interventions for tobacco cessation for smokers.

The recent Task Force recommendation on the use of vitamins, minerals, and multivitamins2 states that, while many adults take vitamin and mineral supplements in the belief that they prevent both heart disease and cancer, there is no evidence to support that belief. And there is good evidence that both β-carotene and vitamin E do not prevent disease. For other vitamins and minerals, singly or in combination, there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against their use.2

The Community Preventive Services Task Force—a separate expert panel established by the US Department of Health and Human Services to complement the USPSTF—makes recommendations on population-level interventions and has a series of recommendations on ways to improve the population’s nutrition and physical activity.10 These community-based interventions, if widely implemented, would probably yield greater improvements in healthy eating and increased activity levels than resource-intense clinical interventions based on individual patients with low risk.

In the past 2 years, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has released 2 recommendations on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD). And it is proposing a third. The first recommendation, released in 2012, covered behavioral counseling on diet and physical activity to prevent CVD in individuals without documented CVD risks.1 The second recommendation, released earlier this year, covered the use of vitamins and mineral supplements to prevent CVD.2 A draft of the proposed third recommendation, which was posted for public review until early June, covers behavioral counseling to help adults with known CVD risk factors improve their diet and physical activity (TABLE).1-3

Counseling can influence behavior, but does it affect outcomes?

CVD is the leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for >596,000 deaths per year with an age-adjusted rate of 191.4 per 100,000.4 Age-adjusted CVD mortality has been declining for decades thanks to improved medical care and a reduction in smoking and other risk factors. It is well documented that adults who follow national recommendations for a healthy diet and levels of physical activity have lower rates of CVD and CVD mortality.1 The USPSTF agrees with the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) that everyone would benefit from a healthier diet and more exercise.5 However, the Task Force reviewed the evidence on behavioral counseling in the primary care setting and found that, for adults who do not have known CVD, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes, even high-intensity behavioral counseling resulted in only a small benefit in intermediate outcomes, which would translate into very small population-wide improvements.

In the evidence report prepared by the Task Force, the intensity of counseling intervention was defined as low, medium, or high if it lasted, respectively, 1 to 30 minutes, 31 to 360 minutes, or ≥361 minutes. Low-intensity interventions involved brief counseling sessions performed by primary care clinicians or mailing educational materials to patients or both. Medium- and high-intensity interventions usually were conducted by health educators, nutritionists, or other professionals instead of primary care clinicians. These interventions improved patients’ consumption of a healthier diet and participation in physical activity, but yielded only modest reductions in body mass index (BMI), blood pressure (BP), and lipid levels. Moreover, no direct evidence exists for improved CVD outcomes with these interventions.

The recent AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle modifications recommends that clinicians advise all adults on healthy dietary choices and exercise, based on the known benefits of these behaviors. The guideline developers recognized that the evidence for benefits appears in the highest risk groups, and they did not assess the evidence for effectiveness of behavioral counseling itself.6

The Task Force rationale for recommending counseling

In the draft of its third recommendation addressing those at highest risk for CVD, the Task Force does advise high-intensity behavioral counseling for those who are overweight or obese and who have other CVD risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or impaired fasting glucose levels. This proposed new recommendation replaces one from 2003 that advised intensive dietary counseling for those with CVD risks including hyperlipidemia. The draft focuses attention in primary care on those who are overweight or obese. It complements another Task Force recommendation to provide or to refer patients for intensive multicomponent behavioral interventions if they are obese, defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2.7

The Task Force cited 2 examples of behavioral interventions that can improve outcomes in those with CVD risks—the Diabetes Prevention Program and PREMIER, a set of interventions to lower BP.8,9 These programs have improved intermediate outcomes after 12 to 24 months, decreasing total cholesterol by 3 to 6 mg/dL and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by 1.5 to 5 mg/dL; systolic and diastolic BP by 1 to 3 mm Hg and 1 to 2 mm Hg, respectively; fasting glucose by 1 to 3 mg/dL; and weight by approximately 3 kg. The Task Force felt that while hard evidence is lacking for reducing CVD with counseling, epidemiologic studies demonstrate that, in those at high risk, reductions in CVD rates generally reflect the magnitude of improvement in intermediate measures.

Half of all adults in the United States have at least one documented CVD risk factor. But the potential benefit of behavioral counseling for those without documented CVD risks is relatively small. Rather than expending effort for only modest gain in the lower risk group, the Task Force recommends focusing on those with highest CVD risk. Thus the non-high risk group received a “C” recommendation, while the group of overweight and obese patients with other CVD risks received a “B” recommendation for essentially the same interventions. (For more on the grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.)

In addition to counseling...

The Task Force also recommends other interventions for the primary prevention of CVD:

- screening for and treating hypertension

- selectively screening for hyperlipidemia

- using aspirin to prevent CVD in those at high risk

- intensive counseling on weight management for those who are obese

- advising children and adolescents to avoid tobacco, and using brief interventions for tobacco cessation for smokers.

The recent Task Force recommendation on the use of vitamins, minerals, and multivitamins2 states that, while many adults take vitamin and mineral supplements in the belief that they prevent both heart disease and cancer, there is no evidence to support that belief. And there is good evidence that both β-carotene and vitamin E do not prevent disease. For other vitamins and minerals, singly or in combination, there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against their use.2

The Community Preventive Services Task Force—a separate expert panel established by the US Department of Health and Human Services to complement the USPSTF—makes recommendations on population-level interventions and has a series of recommendations on ways to improve the population’s nutrition and physical activity.10 These community-based interventions, if widely implemented, would probably yield greater improvements in healthy eating and increased activity levels than resource-intense clinical interventions based on individual patients with low risk.

1. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsphys.htm. Accessed May 21, 2014.

2. USPSTF. Vitamin, mineral, and multivitamin supplements for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf14/vitasupp/vitasuppfinalrs.htm. Accessed May 21, 2014.

3. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with known risk factors: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement (Draft). US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf13/cvdhighrisk/cvdhighriskdraftrec.htm. Accessed July 22, 2014.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. Natl Vital Stat Report. 2012;61:1-51.

5. Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard, JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Nov 12. [Epub ahead of print].

6. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; 2013 ACC/AHA Cholesterol Guideline Panel. Treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in adults: synopsis of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:339-343.

7. USPSTF. Screening for and management of obesity in adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsobes.htm. Accessed May 21, 2014.

8. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393-403.

9. Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, et al; PREMIER Collaborative Research Group. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-month results of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:485-495.

10. USPSTF. The Guide to Community Preventive Services. Community Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. Accessed May 21, 2014.

1. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsphys.htm. Accessed May 21, 2014.

2. USPSTF. Vitamin, mineral, and multivitamin supplements for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf14/vitasupp/vitasuppfinalrs.htm. Accessed May 21, 2014.

3. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with known risk factors: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement (Draft). US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf13/cvdhighrisk/cvdhighriskdraftrec.htm. Accessed July 22, 2014.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. Natl Vital Stat Report. 2012;61:1-51.

5. Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard, JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013 Nov 12. [Epub ahead of print].

6. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; 2013 ACC/AHA Cholesterol Guideline Panel. Treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in adults: synopsis of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:339-343.

7. USPSTF. Screening for and management of obesity in adults. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsobes.htm. Accessed May 21, 2014.

8. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393-403.

9. Elmer PJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, et al; PREMIER Collaborative Research Group. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on diet, weight, physical fitness, and blood pressure control: 18-month results of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:485-495.

10. USPSTF. The Guide to Community Preventive Services. Community Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. Accessed May 21, 2014.

Measles & pertussis: How best to respond to an outbreak

MERS: What you need to know

USPSTF: What’s recommended, what’s not

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) was busy in 2013, issuing 26 recommendations on 16 topics (TABLES 1-3). We have covered some of these topics previously in Practice Alerts or audiocasts—vitamin D for bone health and fall prevention,1 screening for lung cancer,2 human immunodeficiency virus infection,3 and the use of multivitamins to prevent cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD).4 Another Practice Alert on chronic hepatitis C virus infection reviewed recommendations of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,5 which agree with those of the USPSTF. This Practice Alert discusses the remaining USPSTF recommendations.

Alcohol and tobacco

The Task Force (TF) reports that 30% of adults are affected by alcohol-related problems and that alcohol causes 85,000 deaths per year, making it the third leading cause of preventable death.6 The TF reviewed evidence on screening and counseling and now recommends screening adults ≥18 years for alcohol misuse and providing brief counseling to reduce alcohol use for those who engage in risky or hazardous drinking.6 The TF recommends any of 3 screening tools: using either the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or the abbreviated AUDIT-Consumption (AUDIT-C), or asking a single-question, such as “How many times in the past year have you had 5 (for men) or 4 (for women and all adults >65 years) or more drinks in a day?”6

Counseling for 5 to 15 minutes during the initial clinical encounter and then at subsequent visits is more effective than very brief (<5 minutes) or single-episode counseling. Counseling can include action plans, drinking diaries, stress management, or problem solving, and it can be done face-to-face or with written self-help materials, computer- or Web-based programs, or telephone support. Despite the importance of alcohol misuse as a health problem, the TF could find no evidence that screening and behavioral counseling is effective for adolescents.

For tobacco use, however, the TF now recommends providing prevention advice to school-age children and adolescents,7 presented in person or through written materials, videos, or other media. Over 8% of middle school children and close to 24% of high school students use tobacco.7 Tobacco is the leading cause of preventable deaths in the United States, and most smokers start before they are adults.7

Cancer screening and prevention

In addition to the recommendation for lung cancer screening, 2 other cancer screening/prevention recommendations were made in 2013. One is a modification of the previous recommendation on the use of BRCA gene testing to detect increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer. The recommendation now states that if a woman has a family member with breast, ovarian, tubal, or peritoneal cancer, her physician should use a screening tool to determine if her family history suggests high risk for having either BRCA1 or BRCA2. With a positive screening result, referral for genetic counseling is warranted. After counseling, the patient may choose to undergo BRCA testing. Screening tools reviewed by the TF are the Ontario Family History Assessment Tool, the Manchester Scoring System, the Referral Screening Tool, the Pedigree Assessment Tool, and the Family History Screening-7 instrument.8

The second recommendation is complex and concerns whether to prescribe tamoxifen or raloxifene to prevent breast cancer in women at high risk—ie, a 5-year risk ≥3%.9 One tool for estimating risk can be found at http://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/. It calculates risk based on age, race, genetic profile, age at menopause and menarche, family history of breast cancer, and personal history of breast cancer and biopsies. The TF recommends that physicians share decision making with women who are at high risk of breast cancer and offer medication to those at low risk of complications (those who have had a hysterectomy). Use of tamoxifen or raloxifene can reduce risk of the invasive cancer by 7 to 9 cases per 1000 women over 5 years. However, the risk of venous thromboembolism increases by 4 to 7 cases per 1000 over 5 years, and tamoxifen increases the risk of endometrial cancer by 4 in 1000. Both medications can cause hot flashes.9

Gestational diabetes

For a number of years the TF has assigned an “I” statement (insufficient evidence to assess benefits and harms) to screening for gestational diabetes. It recently changed that to a “B” recommendation for all pregnant women after the 24th week of pregnancy. Screening before 24 weeks is still listed as an I. Possible screening tools include a fasting blood glucose test, a 50-g oral glucose challenge test, or an assessment of risk factors. The TF did not find evidence of superiority with any of these methods. The TF found that diet modifications, glucose monitoring, and use of insulin can, in some cases, moderately reduce the incidence of preeclampsia, macrosomia, and shoulder dystocia.10

Intimate partner violence

Another change from a previous “I” statement pertains to intimate partner violence (IPV). The TF now recommends screening women of childbearing age for IPV and either providing intervention services for those who screen positive for IPV or referring for services. Reproductive age is defined as 14 to 46 years, although the TF admits that most studies have looked at women ≥18 years.11 Most of the benefits from screening and counseling have been demonstrated in pregnant women.

IPV can include physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse, and it is not limited to opposite sex couples.11 Screening tools with the highest sensitivity and specificity include the Hurt, Insult, Threaten, and Scream (HITS) scale. Potential interventions include counseling, home visits, information cards, referrals to community services, and mentoring support.

While the TF acknowledges that both child abuse and elder abuse are prominent problems, there is not enough evidence to assess and recommend interventions.11,12

D recommendations

There were 4 “D” recommendations (recommend against) in 2013: testing for BRCA or using tamoxifen or raloxifene in women at low risk of breast cancer; using β-carotene or vitamin E to prevent CVD and cancer; and using low doses of vitamin D and calcium to prevent fractures in noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women (TABLE 2). In each instance the harms of the intervention were deemed to exceed potential benefits.

I statements

The TF still finds little evidence to support some common practices (TABLE 3). Physicians who use these interventions should realize that the TF, after thorough systematic reviews of the available evidence, does not find enough evidence to assess their relative benefits and harms. A description of the evidence on each condition can be found in the recommendations section of the USPSTF Web site (http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstopics.htm).

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Vitamin D: when it helps, when it harms. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:368-370.

2. Campos-Outcalt D. Lung cancer screening: USPSTF revises its recommendation. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:733-740.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. HIV screening: what the USPSTF says now. [Audiocast]. Parsippany, NJ; The Journal of Family Practice: 2013. Available at: http://www.jfponline.com/multimedia/audio/article/hiv-screening-what-the-uspstf-says-now/a1c4bc0fc9405f18820bb19fe971f743.html. Accessed March 14, 2014.