User login

PUFAs a promising add-on for borderline personality disorder

Marine omega-3 fatty acids may be a promising add-on therapy for improving symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD), new research suggests.

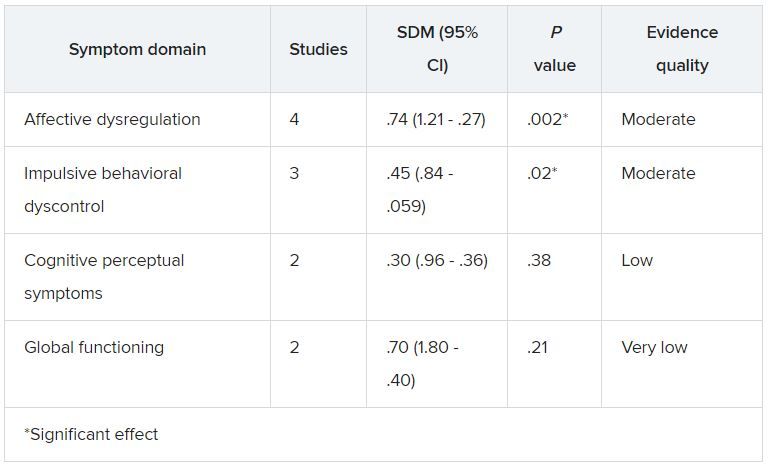

A meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials showed that adjunctive omega-3 fatty polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) significantly reduced overall BPD symptom severity, particularly affect dysregulation and impulsive behavior.

“Given the mechanisms of action and beneficial side effect profile, this [analysis] suggests that omega-3 fatty acids could be considered as add-on treatment” for patients with BPD, senior author Roel J. T. Mocking MD, PhD, resident in psychiatry and postdoctoral researcher at Academisch Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Urgent need

“There are several effective treatments, but not all patients respond sufficiently,” which points to an urgent need for additional treatment options, Dr. Mocking said.

He noted that, although “several prior studies showed promising effects of omega-3 fatty acids” for patients with BPD, those studies were relatively small, which precluded more definitive overall conclusions.

The investigators wanted to combine results of the earlier studies to provide a combined estimate of overall effectiveness of the use of omega-3 fatty acids for patients with BP, with the intention of “guiding clinicians and individuals suffering from borderline personality disorder to decide on whether they should add omega-3 fatty acids to their treatment.”

The analyzed four studies that had a total of 137 patients. Three of the studies included patients diagnosed with BPD; one included individuals with recurrent self-harm, most of whom were also diagnosed with BPD.

Omega-3 fatty acids were used as monotherapy in one study. In the other studies, they were used as add-on therapy to other agents, such as antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and/or valproic acid. None of the studies included patients who were taking antipsychotics.

The type of omega-3 PUFAs were derived from marine rather than plant sources.

Three studies compared omega-3 fatty acids with placebo. One study compared valproic acid monotherapy with valproic acid plus omega-3 fatty acids and did not include a placebo group.

Significant symptom reduction

Random-effects meta-analyses showed an “overall significant decreasing effect” of omega-3 fatty acids on overall BPD symptom severity (standardized difference in means, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.91-0.17; P = .004) in the omega-3 group compared with the control group, with a medium effect size.

The investigators added that there was “no relevant heterogeneity” (P = .45).

Although heterogeneity was “more pronounced” in the affective dysregulation symptom domain, it did not reach statistical significance, the researchers noted.

The impulsive behavioral dyscontrol and cognitive perceptual symptom domains had “no relevant heterogeneity.” On the other hand, there was “substantial heterogeneity” in the global functioning symptom group.

Omega-3 fatty acids “have multiple bioactive roles in the brain. For example, they form essential components of the membrane of brain cells and thereby influence the structure and functioning of the brain. They also have an effect on inflammation levels in the brain,” Dr. Mocking said.

“Because we cannot synthesize these omega-3 fatty acids ourselves, we are dependent on our diet. The main dietary source of omega-3 fatty acids is fatty fish. However, since the industrial revolution, we eat less and less fatty fish, risking deficiency of omega-3 fatty acids causing brain dysfunction,” he added.

Dr. Mocking noted that

This “suggests that they could be combined to increase overall effectiveness,” he said.

Important benefit

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the benefit of omega-3 “on impulsivity and mood symptoms is especially important, as these are some of the most debilitating aspects of BPD and lead to service utilization, such as ER, primary care, and specialty care.”

In addition, “impulsivity often presages suicidality,” he noted.

Dr. McIntyre, who is also chair and executive director of the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation in Toronto and was not involved with the study, called the effect size “quite reasonable.”

“The mechanistic story is very strong around anti-inflammatory effect, which particularly implied mood and cognition. In other words, inflammation is highly associated with mood and cognitive difficulties,” he said.

However, Dr. McIntyre also pointed to several significant challenges, including “quality assurance on the purchase of the product of fish oil, as it is not sufficiently regulated.” It is also unclear which individuals are more likely to benefit from it.

For example, major depressive disorder data have shown that “fish oils are not as effective as we hoped but are especially effective in people with baseline elevation of inflammatory markers,” Dr. McIntyre said.

“In other words, is there a way to identify a biomarkers/biosignature or phenomenology that’s more likely to identify a subgroup of people with BPD who might benefit benefiting from omega-3?” he asked.

Dr. Mocking and the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and AbbVie. Dr. McIntyre is also CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Marine omega-3 fatty acids may be a promising add-on therapy for improving symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD), new research suggests.

A meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials showed that adjunctive omega-3 fatty polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) significantly reduced overall BPD symptom severity, particularly affect dysregulation and impulsive behavior.

“Given the mechanisms of action and beneficial side effect profile, this [analysis] suggests that omega-3 fatty acids could be considered as add-on treatment” for patients with BPD, senior author Roel J. T. Mocking MD, PhD, resident in psychiatry and postdoctoral researcher at Academisch Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Urgent need

“There are several effective treatments, but not all patients respond sufficiently,” which points to an urgent need for additional treatment options, Dr. Mocking said.

He noted that, although “several prior studies showed promising effects of omega-3 fatty acids” for patients with BPD, those studies were relatively small, which precluded more definitive overall conclusions.

The investigators wanted to combine results of the earlier studies to provide a combined estimate of overall effectiveness of the use of omega-3 fatty acids for patients with BP, with the intention of “guiding clinicians and individuals suffering from borderline personality disorder to decide on whether they should add omega-3 fatty acids to their treatment.”

The analyzed four studies that had a total of 137 patients. Three of the studies included patients diagnosed with BPD; one included individuals with recurrent self-harm, most of whom were also diagnosed with BPD.

Omega-3 fatty acids were used as monotherapy in one study. In the other studies, they were used as add-on therapy to other agents, such as antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and/or valproic acid. None of the studies included patients who were taking antipsychotics.

The type of omega-3 PUFAs were derived from marine rather than plant sources.

Three studies compared omega-3 fatty acids with placebo. One study compared valproic acid monotherapy with valproic acid plus omega-3 fatty acids and did not include a placebo group.

Significant symptom reduction

Random-effects meta-analyses showed an “overall significant decreasing effect” of omega-3 fatty acids on overall BPD symptom severity (standardized difference in means, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.91-0.17; P = .004) in the omega-3 group compared with the control group, with a medium effect size.

The investigators added that there was “no relevant heterogeneity” (P = .45).

Although heterogeneity was “more pronounced” in the affective dysregulation symptom domain, it did not reach statistical significance, the researchers noted.

The impulsive behavioral dyscontrol and cognitive perceptual symptom domains had “no relevant heterogeneity.” On the other hand, there was “substantial heterogeneity” in the global functioning symptom group.

Omega-3 fatty acids “have multiple bioactive roles in the brain. For example, they form essential components of the membrane of brain cells and thereby influence the structure and functioning of the brain. They also have an effect on inflammation levels in the brain,” Dr. Mocking said.

“Because we cannot synthesize these omega-3 fatty acids ourselves, we are dependent on our diet. The main dietary source of omega-3 fatty acids is fatty fish. However, since the industrial revolution, we eat less and less fatty fish, risking deficiency of omega-3 fatty acids causing brain dysfunction,” he added.

Dr. Mocking noted that

This “suggests that they could be combined to increase overall effectiveness,” he said.

Important benefit

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the benefit of omega-3 “on impulsivity and mood symptoms is especially important, as these are some of the most debilitating aspects of BPD and lead to service utilization, such as ER, primary care, and specialty care.”

In addition, “impulsivity often presages suicidality,” he noted.

Dr. McIntyre, who is also chair and executive director of the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation in Toronto and was not involved with the study, called the effect size “quite reasonable.”

“The mechanistic story is very strong around anti-inflammatory effect, which particularly implied mood and cognition. In other words, inflammation is highly associated with mood and cognitive difficulties,” he said.

However, Dr. McIntyre also pointed to several significant challenges, including “quality assurance on the purchase of the product of fish oil, as it is not sufficiently regulated.” It is also unclear which individuals are more likely to benefit from it.

For example, major depressive disorder data have shown that “fish oils are not as effective as we hoped but are especially effective in people with baseline elevation of inflammatory markers,” Dr. McIntyre said.

“In other words, is there a way to identify a biomarkers/biosignature or phenomenology that’s more likely to identify a subgroup of people with BPD who might benefit benefiting from omega-3?” he asked.

Dr. Mocking and the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and AbbVie. Dr. McIntyre is also CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Marine omega-3 fatty acids may be a promising add-on therapy for improving symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD), new research suggests.

A meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials showed that adjunctive omega-3 fatty polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) significantly reduced overall BPD symptom severity, particularly affect dysregulation and impulsive behavior.

“Given the mechanisms of action and beneficial side effect profile, this [analysis] suggests that omega-3 fatty acids could be considered as add-on treatment” for patients with BPD, senior author Roel J. T. Mocking MD, PhD, resident in psychiatry and postdoctoral researcher at Academisch Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Urgent need

“There are several effective treatments, but not all patients respond sufficiently,” which points to an urgent need for additional treatment options, Dr. Mocking said.

He noted that, although “several prior studies showed promising effects of omega-3 fatty acids” for patients with BPD, those studies were relatively small, which precluded more definitive overall conclusions.

The investigators wanted to combine results of the earlier studies to provide a combined estimate of overall effectiveness of the use of omega-3 fatty acids for patients with BP, with the intention of “guiding clinicians and individuals suffering from borderline personality disorder to decide on whether they should add omega-3 fatty acids to their treatment.”

The analyzed four studies that had a total of 137 patients. Three of the studies included patients diagnosed with BPD; one included individuals with recurrent self-harm, most of whom were also diagnosed with BPD.

Omega-3 fatty acids were used as monotherapy in one study. In the other studies, they were used as add-on therapy to other agents, such as antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and/or valproic acid. None of the studies included patients who were taking antipsychotics.

The type of omega-3 PUFAs were derived from marine rather than plant sources.

Three studies compared omega-3 fatty acids with placebo. One study compared valproic acid monotherapy with valproic acid plus omega-3 fatty acids and did not include a placebo group.

Significant symptom reduction

Random-effects meta-analyses showed an “overall significant decreasing effect” of omega-3 fatty acids on overall BPD symptom severity (standardized difference in means, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.91-0.17; P = .004) in the omega-3 group compared with the control group, with a medium effect size.

The investigators added that there was “no relevant heterogeneity” (P = .45).

Although heterogeneity was “more pronounced” in the affective dysregulation symptom domain, it did not reach statistical significance, the researchers noted.

The impulsive behavioral dyscontrol and cognitive perceptual symptom domains had “no relevant heterogeneity.” On the other hand, there was “substantial heterogeneity” in the global functioning symptom group.

Omega-3 fatty acids “have multiple bioactive roles in the brain. For example, they form essential components of the membrane of brain cells and thereby influence the structure and functioning of the brain. They also have an effect on inflammation levels in the brain,” Dr. Mocking said.

“Because we cannot synthesize these omega-3 fatty acids ourselves, we are dependent on our diet. The main dietary source of omega-3 fatty acids is fatty fish. However, since the industrial revolution, we eat less and less fatty fish, risking deficiency of omega-3 fatty acids causing brain dysfunction,” he added.

Dr. Mocking noted that

This “suggests that they could be combined to increase overall effectiveness,” he said.

Important benefit

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the benefit of omega-3 “on impulsivity and mood symptoms is especially important, as these are some of the most debilitating aspects of BPD and lead to service utilization, such as ER, primary care, and specialty care.”

In addition, “impulsivity often presages suicidality,” he noted.

Dr. McIntyre, who is also chair and executive director of the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation in Toronto and was not involved with the study, called the effect size “quite reasonable.”

“The mechanistic story is very strong around anti-inflammatory effect, which particularly implied mood and cognition. In other words, inflammation is highly associated with mood and cognitive difficulties,” he said.

However, Dr. McIntyre also pointed to several significant challenges, including “quality assurance on the purchase of the product of fish oil, as it is not sufficiently regulated.” It is also unclear which individuals are more likely to benefit from it.

For example, major depressive disorder data have shown that “fish oils are not as effective as we hoped but are especially effective in people with baseline elevation of inflammatory markers,” Dr. McIntyre said.

“In other words, is there a way to identify a biomarkers/biosignature or phenomenology that’s more likely to identify a subgroup of people with BPD who might benefit benefiting from omega-3?” he asked.

Dr. Mocking and the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and AbbVie. Dr. McIntyre is also CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ketamine and psychosis risk: New data

Ketamine used to treat severe depression in patients with a history of psychosis does not exacerbate psychosis risk, new research suggests.

A meta-analysis of nine studies, encompassing 41 patients with TRD and a history of psychosis, suggests ketamine is safe and effective and did not exacerbate psychotic symptoms in this patient population.

“We believe our findings could encourage clinicians and researchers to examine a broadened indication for ketamine treatment in individual patients with high levels of treatment resistance, carefully monitoring both clinical response and side effects, specifically looking at possible increases in psychotic symptoms,” study investigator Jolien K. E. Veraart, MD, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands, told this news organization.

The study was published online July 13 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Rapid, robust effects

Ketamine has shown “rapid and robust antidepressant effects” in clinical studies. However, this research has not included patients with past or current psychosis, based on the assumption that psychosis will increase with ketamine administration, since side effects of ketamine can include transient “schizophrenia-like” psychotomimetic phenomena, including perceptual disorders and hallucinations in healthy individuals, the investigators note.

Dr. Veraart said psychotic symptoms are “common in people with severe depression,” and these patients have poorer outcomes with pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy.

Additionally, up to 60% of patients with schizophrenia experience negative symptomatology, including loss of motivation, affective blunting, and anhedonia, which “has a clear phenomenological overlap with depression,” the authors write. They also note anti-anhedonic effects of subanesthetic ketamine doses have been reported, without adversely impacting long-term psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

“Positive results from carefully monitored trials with ketamine treatment in these patients have motivated us to summarize the currently available knowledge to inform our colleagues,” she said.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a literature search and selected 9 articles (N = 41 patients) that reported on ketamine treatment in patients with a history of psychosis or current psychotic symptoms.

All studies were either case reports or pilot studies, the authors report. Types of patients included those with bipolar or unipolar depression, or depression in schizoaffective disorder , or patients with schizophrenia and concurrent depression. Depressive symptomatology was the treatment target in eight studies, and one study targeted negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Dosing, frequency, and types of administration (ketamine IV, esketamine IV, or esketamine subcutaneous) varied from study to study.

In seven studies, ketamine was found to improve depressive symptoms, and in two studies, improvement in psychotic symptoms was also shown. Two studies revealed improvement in symptoms of suicidality. Results of the study that measured negative symptoms showed “significant improvement” in five of six patients, with a -37.3% decrease in mean Brief Negative Symptoms Scale (BNSS) from the baseline to the end of four infusions.

“Ketamine showed good antidepressant effects, and, in some cases, the comorbid symptoms even improved or disappeared after ketamine treatment,” Dr. Veraart summarized. However, the effect size of ketamine might be lower in those with a history of psychosis, she added.

She also noted that

She pointed to one study limitation, which is that only small, uncontrolled trials were included and that there is a risk for publication bias.

Larger trials needed

Commenting on the study, Dan Iosifescu, MD, MSc, associate professor of psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, said that if the finding “were based on a larger study it would be very important, as a theoretical risk of psychosis is preventing such patients from access to an otherwise beneficial treatment.”

However, “since the review is based on a small sample, a low risk of psychosis exacerbation after IV ketamine is still possible,” said Dr. Iosifescu, who is also the director of clinical research at the Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research in Orangeburg, New York, and was not involved with the study.

Dr. Veraart agreed, adding that the “efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ketamine in depressed patients with a vulnerability to psychosis should be investigated in well-designed randomized controlled trials before application on a large scale is promoted.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Veraart has received speaker honoraria from Janssen outside of the submitted work. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Iosifescu has been a consultant to the Centers of Psychiatric Excellence, advising clinics on the best methods of providing treatment with IV ketamine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ketamine used to treat severe depression in patients with a history of psychosis does not exacerbate psychosis risk, new research suggests.

A meta-analysis of nine studies, encompassing 41 patients with TRD and a history of psychosis, suggests ketamine is safe and effective and did not exacerbate psychotic symptoms in this patient population.

“We believe our findings could encourage clinicians and researchers to examine a broadened indication for ketamine treatment in individual patients with high levels of treatment resistance, carefully monitoring both clinical response and side effects, specifically looking at possible increases in psychotic symptoms,” study investigator Jolien K. E. Veraart, MD, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands, told this news organization.

The study was published online July 13 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Rapid, robust effects

Ketamine has shown “rapid and robust antidepressant effects” in clinical studies. However, this research has not included patients with past or current psychosis, based on the assumption that psychosis will increase with ketamine administration, since side effects of ketamine can include transient “schizophrenia-like” psychotomimetic phenomena, including perceptual disorders and hallucinations in healthy individuals, the investigators note.

Dr. Veraart said psychotic symptoms are “common in people with severe depression,” and these patients have poorer outcomes with pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy.

Additionally, up to 60% of patients with schizophrenia experience negative symptomatology, including loss of motivation, affective blunting, and anhedonia, which “has a clear phenomenological overlap with depression,” the authors write. They also note anti-anhedonic effects of subanesthetic ketamine doses have been reported, without adversely impacting long-term psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

“Positive results from carefully monitored trials with ketamine treatment in these patients have motivated us to summarize the currently available knowledge to inform our colleagues,” she said.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a literature search and selected 9 articles (N = 41 patients) that reported on ketamine treatment in patients with a history of psychosis or current psychotic symptoms.

All studies were either case reports or pilot studies, the authors report. Types of patients included those with bipolar or unipolar depression, or depression in schizoaffective disorder , or patients with schizophrenia and concurrent depression. Depressive symptomatology was the treatment target in eight studies, and one study targeted negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Dosing, frequency, and types of administration (ketamine IV, esketamine IV, or esketamine subcutaneous) varied from study to study.

In seven studies, ketamine was found to improve depressive symptoms, and in two studies, improvement in psychotic symptoms was also shown. Two studies revealed improvement in symptoms of suicidality. Results of the study that measured negative symptoms showed “significant improvement” in five of six patients, with a -37.3% decrease in mean Brief Negative Symptoms Scale (BNSS) from the baseline to the end of four infusions.

“Ketamine showed good antidepressant effects, and, in some cases, the comorbid symptoms even improved or disappeared after ketamine treatment,” Dr. Veraart summarized. However, the effect size of ketamine might be lower in those with a history of psychosis, she added.

She also noted that

She pointed to one study limitation, which is that only small, uncontrolled trials were included and that there is a risk for publication bias.

Larger trials needed

Commenting on the study, Dan Iosifescu, MD, MSc, associate professor of psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, said that if the finding “were based on a larger study it would be very important, as a theoretical risk of psychosis is preventing such patients from access to an otherwise beneficial treatment.”

However, “since the review is based on a small sample, a low risk of psychosis exacerbation after IV ketamine is still possible,” said Dr. Iosifescu, who is also the director of clinical research at the Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research in Orangeburg, New York, and was not involved with the study.

Dr. Veraart agreed, adding that the “efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ketamine in depressed patients with a vulnerability to psychosis should be investigated in well-designed randomized controlled trials before application on a large scale is promoted.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Veraart has received speaker honoraria from Janssen outside of the submitted work. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Iosifescu has been a consultant to the Centers of Psychiatric Excellence, advising clinics on the best methods of providing treatment with IV ketamine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ketamine used to treat severe depression in patients with a history of psychosis does not exacerbate psychosis risk, new research suggests.

A meta-analysis of nine studies, encompassing 41 patients with TRD and a history of psychosis, suggests ketamine is safe and effective and did not exacerbate psychotic symptoms in this patient population.

“We believe our findings could encourage clinicians and researchers to examine a broadened indication for ketamine treatment in individual patients with high levels of treatment resistance, carefully monitoring both clinical response and side effects, specifically looking at possible increases in psychotic symptoms,” study investigator Jolien K. E. Veraart, MD, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands, told this news organization.

The study was published online July 13 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Rapid, robust effects

Ketamine has shown “rapid and robust antidepressant effects” in clinical studies. However, this research has not included patients with past or current psychosis, based on the assumption that psychosis will increase with ketamine administration, since side effects of ketamine can include transient “schizophrenia-like” psychotomimetic phenomena, including perceptual disorders and hallucinations in healthy individuals, the investigators note.

Dr. Veraart said psychotic symptoms are “common in people with severe depression,” and these patients have poorer outcomes with pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and electroconvulsive therapy.

Additionally, up to 60% of patients with schizophrenia experience negative symptomatology, including loss of motivation, affective blunting, and anhedonia, which “has a clear phenomenological overlap with depression,” the authors write. They also note anti-anhedonic effects of subanesthetic ketamine doses have been reported, without adversely impacting long-term psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

“Positive results from carefully monitored trials with ketamine treatment in these patients have motivated us to summarize the currently available knowledge to inform our colleagues,” she said.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a literature search and selected 9 articles (N = 41 patients) that reported on ketamine treatment in patients with a history of psychosis or current psychotic symptoms.

All studies were either case reports or pilot studies, the authors report. Types of patients included those with bipolar or unipolar depression, or depression in schizoaffective disorder , or patients with schizophrenia and concurrent depression. Depressive symptomatology was the treatment target in eight studies, and one study targeted negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

Dosing, frequency, and types of administration (ketamine IV, esketamine IV, or esketamine subcutaneous) varied from study to study.

In seven studies, ketamine was found to improve depressive symptoms, and in two studies, improvement in psychotic symptoms was also shown. Two studies revealed improvement in symptoms of suicidality. Results of the study that measured negative symptoms showed “significant improvement” in five of six patients, with a -37.3% decrease in mean Brief Negative Symptoms Scale (BNSS) from the baseline to the end of four infusions.

“Ketamine showed good antidepressant effects, and, in some cases, the comorbid symptoms even improved or disappeared after ketamine treatment,” Dr. Veraart summarized. However, the effect size of ketamine might be lower in those with a history of psychosis, she added.

She also noted that

She pointed to one study limitation, which is that only small, uncontrolled trials were included and that there is a risk for publication bias.

Larger trials needed

Commenting on the study, Dan Iosifescu, MD, MSc, associate professor of psychiatry, New York University School of Medicine, said that if the finding “were based on a larger study it would be very important, as a theoretical risk of psychosis is preventing such patients from access to an otherwise beneficial treatment.”

However, “since the review is based on a small sample, a low risk of psychosis exacerbation after IV ketamine is still possible,” said Dr. Iosifescu, who is also the director of clinical research at the Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research in Orangeburg, New York, and was not involved with the study.

Dr. Veraart agreed, adding that the “efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ketamine in depressed patients with a vulnerability to psychosis should be investigated in well-designed randomized controlled trials before application on a large scale is promoted.”

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Veraart has received speaker honoraria from Janssen outside of the submitted work. The other authors’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Iosifescu has been a consultant to the Centers of Psychiatric Excellence, advising clinics on the best methods of providing treatment with IV ketamine.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Common parasite now tied to impaired cognitive function

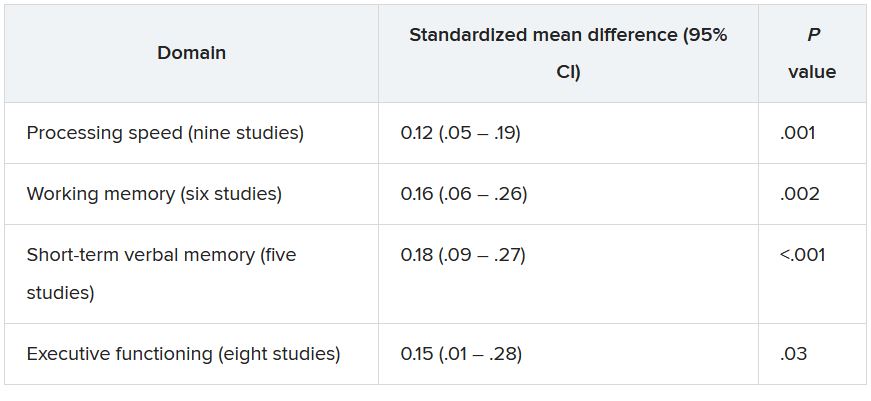

Investigators reviewed and conducted a meta-analysis of 13 studies that encompassed more than 13,000 healthy adults and found a modest but significant association between T. gondii seropositivity and impaired performance on cognitive tests of processing speed, working memory, short-term verbal memory, and executive function. The average age of the persons in the studies was close to 50 years.

“Our findings show that T. gondii could have a negative but small effect on cognition,” study investigator Arjen Sutterland, MD, of the Amsterdam Neuroscience Research Institute and the Amsterdam Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Amsterdam, said in an interview.

The study was published online July 14, 2021, in JAMA Psychiatry.

Mental illness link

T. gondii is “an intracellular parasite that produces quiescent infection in approximately 30% of humans worldwide,” the authors wrote. The parasite that causes the infection not only settles in muscle and liver tissue but also can cross the blood-brain barrier and settle quiescently in brain tissue. It can be spread through contact with cat feces or by consuming contaminated meat.

Previous research has shown that neurocognitive changes associated with toxoplasmosis can occur in humans, and meta-analyses suggest an association with neuropsychiatric disorders. Some research has also tied T. gondii infection to increased motor vehicle crashes and suicide attempts.

Dr. Sutterland said he had been inspired by the work of E. Fuller Torrey and Bob Yolken, who proposed the connection between T. gondii and schizophrenia.

Some years ago, Dr. Sutterland and his group analyzed the mental health consequences of T. gondii infection and found “several interesting associations,” but they were unable to “rule out reverse causation – i.e., people with mental health disorders more often get these infections – as well as determine the impact on the population of this common infection.”

For the current study, the investigators analyzed studies that examined specifically cognitive functioning in otherwise healthy individuals in relation to T. gondii infection, “because reverse causation would be less likely in this population and a grasp of global impact would become more clear.”

The researchers conducted a literature search of studies conducted through June 7, 2019, that analyzed cognitive function among healthy participants for whom data on T. gondii seropositivity were available.

A total of 13 studies (n = 13,289 participants; mean age, 46.7 years; 49.6% male) were used in the review and meta-analysis. Some of the studies enrolled a healthy population sample; other studies compared participants with and those without psychiatric disorders. From these, the researchers extracted only the data concerning healthy participants.

The studies analyzed four cognitive domains: processing speed, working memory, short-term verbal memory, and executive functioning.

All cognitive domains affected

Of all the participants, 22.6% had antibodies against T. gondii.

Participants who were seropositive for T. gondii had less favorable functioning in all cognitive domains, with “small but significant” differences.

The researchers conducted a meta-regression analysis of mean age in the analysis of executive functioning and found greater effect sizes as age increased (Q = 6.17; R2 = 81%; P = .01).

The studies were of “high quality,” and there was “little suggestion of publication bias was detected,” the authors noted.

“Although the extent of the associations was modest, the ubiquitous prevalence of the quiescent infection worldwide ... suggests that the consequences for cognitive function of the population as a whole may be substantial, although it is difficult to quantify the global impact,” they wrote.

They note that because the studies were cross-sectional in nature, causality cannot be established.

Nevertheless, Dr. Sutterland suggested several possible mechanisms through which T. gondii might affect neurocognition.

“We know the parasite forms cysts in the brain and can influence dopaminergic neurotransmission, which, in turn, affects neurocognition. Alternatively, it is also possible that the immune response to the infection in the brain causes cognitive impairment. This remains an important question to explore further,” he said.

He noted that clinicians can reassure patients who test positive for T. gondii that although the infection can have a negative impact on cognition, the effect is “small.”

Prevention programs warranted

Commenting on the study in an interview, Shawn D. Gale, PhD, associate professor, department of psychology and neuroscience center, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, called it a “great meta-analysis.” He noted that his group is researching the subject and has obtained similar findings. A big plus is that the researchers assessed several cognitive domains, not just one.

Although the data showed “mild effects,” the findings could be important on a population level. Because 30% of the world’s population are seropositive for T. gondii, a potentially large number of people are at risk for cognitive impairment, noted Dr. Gale, who was not involved with the study.

“If you look at the United States, perhaps 10%-15% of people might test positive [for T. gondii], but in Germany and France, the number comes closer to 50%, and in other places in the world – especially countries that have a harder time economically – the rates are even higher. So if it can affect cognition, even a small effect is a big deal,” Dr. Gale said.

“I think prevention will be the most important thing, and perhaps down the road, I hope that a vaccine will be considered,” Dr. Gale added.

“These findings indicate that primary prevention of the infection could have substantial global impact on mental health” and that public health programs to prevent T. gondii “are warranted.”

These programs might consist of hygienic measures, especially after human contact with contaminated sources, as well as research into vaccine development.

No source of funding for the study was listed. The authors and Dr. Gale reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators reviewed and conducted a meta-analysis of 13 studies that encompassed more than 13,000 healthy adults and found a modest but significant association between T. gondii seropositivity and impaired performance on cognitive tests of processing speed, working memory, short-term verbal memory, and executive function. The average age of the persons in the studies was close to 50 years.

“Our findings show that T. gondii could have a negative but small effect on cognition,” study investigator Arjen Sutterland, MD, of the Amsterdam Neuroscience Research Institute and the Amsterdam Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Amsterdam, said in an interview.

The study was published online July 14, 2021, in JAMA Psychiatry.

Mental illness link

T. gondii is “an intracellular parasite that produces quiescent infection in approximately 30% of humans worldwide,” the authors wrote. The parasite that causes the infection not only settles in muscle and liver tissue but also can cross the blood-brain barrier and settle quiescently in brain tissue. It can be spread through contact with cat feces or by consuming contaminated meat.

Previous research has shown that neurocognitive changes associated with toxoplasmosis can occur in humans, and meta-analyses suggest an association with neuropsychiatric disorders. Some research has also tied T. gondii infection to increased motor vehicle crashes and suicide attempts.

Dr. Sutterland said he had been inspired by the work of E. Fuller Torrey and Bob Yolken, who proposed the connection between T. gondii and schizophrenia.

Some years ago, Dr. Sutterland and his group analyzed the mental health consequences of T. gondii infection and found “several interesting associations,” but they were unable to “rule out reverse causation – i.e., people with mental health disorders more often get these infections – as well as determine the impact on the population of this common infection.”

For the current study, the investigators analyzed studies that examined specifically cognitive functioning in otherwise healthy individuals in relation to T. gondii infection, “because reverse causation would be less likely in this population and a grasp of global impact would become more clear.”

The researchers conducted a literature search of studies conducted through June 7, 2019, that analyzed cognitive function among healthy participants for whom data on T. gondii seropositivity were available.

A total of 13 studies (n = 13,289 participants; mean age, 46.7 years; 49.6% male) were used in the review and meta-analysis. Some of the studies enrolled a healthy population sample; other studies compared participants with and those without psychiatric disorders. From these, the researchers extracted only the data concerning healthy participants.

The studies analyzed four cognitive domains: processing speed, working memory, short-term verbal memory, and executive functioning.

All cognitive domains affected

Of all the participants, 22.6% had antibodies against T. gondii.

Participants who were seropositive for T. gondii had less favorable functioning in all cognitive domains, with “small but significant” differences.

The researchers conducted a meta-regression analysis of mean age in the analysis of executive functioning and found greater effect sizes as age increased (Q = 6.17; R2 = 81%; P = .01).

The studies were of “high quality,” and there was “little suggestion of publication bias was detected,” the authors noted.

“Although the extent of the associations was modest, the ubiquitous prevalence of the quiescent infection worldwide ... suggests that the consequences for cognitive function of the population as a whole may be substantial, although it is difficult to quantify the global impact,” they wrote.

They note that because the studies were cross-sectional in nature, causality cannot be established.

Nevertheless, Dr. Sutterland suggested several possible mechanisms through which T. gondii might affect neurocognition.

“We know the parasite forms cysts in the brain and can influence dopaminergic neurotransmission, which, in turn, affects neurocognition. Alternatively, it is also possible that the immune response to the infection in the brain causes cognitive impairment. This remains an important question to explore further,” he said.

He noted that clinicians can reassure patients who test positive for T. gondii that although the infection can have a negative impact on cognition, the effect is “small.”

Prevention programs warranted

Commenting on the study in an interview, Shawn D. Gale, PhD, associate professor, department of psychology and neuroscience center, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, called it a “great meta-analysis.” He noted that his group is researching the subject and has obtained similar findings. A big plus is that the researchers assessed several cognitive domains, not just one.

Although the data showed “mild effects,” the findings could be important on a population level. Because 30% of the world’s population are seropositive for T. gondii, a potentially large number of people are at risk for cognitive impairment, noted Dr. Gale, who was not involved with the study.

“If you look at the United States, perhaps 10%-15% of people might test positive [for T. gondii], but in Germany and France, the number comes closer to 50%, and in other places in the world – especially countries that have a harder time economically – the rates are even higher. So if it can affect cognition, even a small effect is a big deal,” Dr. Gale said.

“I think prevention will be the most important thing, and perhaps down the road, I hope that a vaccine will be considered,” Dr. Gale added.

“These findings indicate that primary prevention of the infection could have substantial global impact on mental health” and that public health programs to prevent T. gondii “are warranted.”

These programs might consist of hygienic measures, especially after human contact with contaminated sources, as well as research into vaccine development.

No source of funding for the study was listed. The authors and Dr. Gale reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators reviewed and conducted a meta-analysis of 13 studies that encompassed more than 13,000 healthy adults and found a modest but significant association between T. gondii seropositivity and impaired performance on cognitive tests of processing speed, working memory, short-term verbal memory, and executive function. The average age of the persons in the studies was close to 50 years.

“Our findings show that T. gondii could have a negative but small effect on cognition,” study investigator Arjen Sutterland, MD, of the Amsterdam Neuroscience Research Institute and the Amsterdam Institute for Infection and Immunity, University of Amsterdam, said in an interview.

The study was published online July 14, 2021, in JAMA Psychiatry.

Mental illness link

T. gondii is “an intracellular parasite that produces quiescent infection in approximately 30% of humans worldwide,” the authors wrote. The parasite that causes the infection not only settles in muscle and liver tissue but also can cross the blood-brain barrier and settle quiescently in brain tissue. It can be spread through contact with cat feces or by consuming contaminated meat.

Previous research has shown that neurocognitive changes associated with toxoplasmosis can occur in humans, and meta-analyses suggest an association with neuropsychiatric disorders. Some research has also tied T. gondii infection to increased motor vehicle crashes and suicide attempts.

Dr. Sutterland said he had been inspired by the work of E. Fuller Torrey and Bob Yolken, who proposed the connection between T. gondii and schizophrenia.

Some years ago, Dr. Sutterland and his group analyzed the mental health consequences of T. gondii infection and found “several interesting associations,” but they were unable to “rule out reverse causation – i.e., people with mental health disorders more often get these infections – as well as determine the impact on the population of this common infection.”

For the current study, the investigators analyzed studies that examined specifically cognitive functioning in otherwise healthy individuals in relation to T. gondii infection, “because reverse causation would be less likely in this population and a grasp of global impact would become more clear.”

The researchers conducted a literature search of studies conducted through June 7, 2019, that analyzed cognitive function among healthy participants for whom data on T. gondii seropositivity were available.

A total of 13 studies (n = 13,289 participants; mean age, 46.7 years; 49.6% male) were used in the review and meta-analysis. Some of the studies enrolled a healthy population sample; other studies compared participants with and those without psychiatric disorders. From these, the researchers extracted only the data concerning healthy participants.

The studies analyzed four cognitive domains: processing speed, working memory, short-term verbal memory, and executive functioning.

All cognitive domains affected

Of all the participants, 22.6% had antibodies against T. gondii.

Participants who were seropositive for T. gondii had less favorable functioning in all cognitive domains, with “small but significant” differences.

The researchers conducted a meta-regression analysis of mean age in the analysis of executive functioning and found greater effect sizes as age increased (Q = 6.17; R2 = 81%; P = .01).

The studies were of “high quality,” and there was “little suggestion of publication bias was detected,” the authors noted.

“Although the extent of the associations was modest, the ubiquitous prevalence of the quiescent infection worldwide ... suggests that the consequences for cognitive function of the population as a whole may be substantial, although it is difficult to quantify the global impact,” they wrote.

They note that because the studies were cross-sectional in nature, causality cannot be established.

Nevertheless, Dr. Sutterland suggested several possible mechanisms through which T. gondii might affect neurocognition.

“We know the parasite forms cysts in the brain and can influence dopaminergic neurotransmission, which, in turn, affects neurocognition. Alternatively, it is also possible that the immune response to the infection in the brain causes cognitive impairment. This remains an important question to explore further,” he said.

He noted that clinicians can reassure patients who test positive for T. gondii that although the infection can have a negative impact on cognition, the effect is “small.”

Prevention programs warranted

Commenting on the study in an interview, Shawn D. Gale, PhD, associate professor, department of psychology and neuroscience center, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, called it a “great meta-analysis.” He noted that his group is researching the subject and has obtained similar findings. A big plus is that the researchers assessed several cognitive domains, not just one.

Although the data showed “mild effects,” the findings could be important on a population level. Because 30% of the world’s population are seropositive for T. gondii, a potentially large number of people are at risk for cognitive impairment, noted Dr. Gale, who was not involved with the study.

“If you look at the United States, perhaps 10%-15% of people might test positive [for T. gondii], but in Germany and France, the number comes closer to 50%, and in other places in the world – especially countries that have a harder time economically – the rates are even higher. So if it can affect cognition, even a small effect is a big deal,” Dr. Gale said.

“I think prevention will be the most important thing, and perhaps down the road, I hope that a vaccine will be considered,” Dr. Gale added.

“These findings indicate that primary prevention of the infection could have substantial global impact on mental health” and that public health programs to prevent T. gondii “are warranted.”

These programs might consist of hygienic measures, especially after human contact with contaminated sources, as well as research into vaccine development.

No source of funding for the study was listed. The authors and Dr. Gale reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Could the Surgisphere Lancet and NEJM retractions debacle happen again?

In May 2020, two major scientific journals published and subsequently retracted studies that relied on data provided by the now-disgraced data analytics company Surgisphere.

One of the studies, published in The Lancet, reported an association between the antimalarial drugs hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine and increased in-hospital mortality and cardiac arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19. The second study, which appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine, described an association between underlying cardiovascular disease, but not related drug therapy, with increased mortality in COVID-19 patients.

The retractions in June 2020 followed an open letter to each publication penned by scientists, ethicists, and clinicians who flagged serious methodological and ethical anomalies in the data used in the studies.

On the 1-year anniversary, researchers and journal editors spoke about what was learned to reduce the risk of something like this happening again.

“The Surgisphere incident served as a wake-up call for everyone involved with scientific research to make sure that data have integrity and are robust,” Sunil Rao, MD, professor of medicine, Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C., and editor-in-chief of Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions, said in an interview.

“I’m sure this isn’t going to be the last incident of this nature, and we have to be vigilant about new datasets or datasets that we haven’t heard of as having a track record of publication,” Dr. Rao said.

Spotlight on authors

The editors of the Lancet Group responded to the “wake-up call” with a statement, Learning From a Retraction, which announced changes to reduce the risks of research and publication misconduct.

The changes affect multiple phases of the publication process. For example, the declaration form that authors must sign “will require that more than one author has directly accessed and verified the data reported in the manuscript.” Additionally, when a research article is the result of an academic and commercial partnership – as was the case in the two retracted studies – “one of the authors named as having accessed and verified data must be from the academic team.”

This was particularly important because it appears that the academic coauthors of the retracted studies did not have access to the data provided by Surgisphere, a private commercial entity.

Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, William Harvey Distinguished Chair in Advanced Cardiovascular Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, who was the lead author of both studies, declined to be interviewed for this article. In a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine editors requesting that the article be retracted, he wrote: “Because all the authors were not granted access to the raw data and the raw data could not be made available to a third-party auditor, we are unable to validate the primary data sources underlying our article.”

In a similar communication with The Lancet, Dr. Mehra wrote even more pointedly that, in light of the refusal of Surgisphere to make the data available to the third-party auditor, “we can no longer vouch for the veracity of the primary data sources.”

“It is very disturbing that the authors were willing to put their names on a paper without ever seeing and verifying the data,” Mario Malički, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at METRICS at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “Saying that they could ‘no longer vouch’ suggests that at one point they could vouch for it. Most likely they took its existence and veracity entirely on trust.”

Dr. Malički pointed out that one of the four criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors for being an author on a study is the “agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.”

The new policies put forth by The Lancet are “encouraging,” but perhaps do not go far enough. “Every author, not only one or two authors, should personally take responsibility for the integrity of data,” he stated.

Many journals “adhere to ICMJE rules in principle and have checkboxes for authors to confirm that they guarantee the veracity of the data.” However, they “do not have the resources to verify the authors’ statements.”

Ideally, “it is the institutions where the researchers work that should guarantee the veracity of the raw data – but I do not know any university or institute that does this,” he said.

No ‘good-housekeeping’ seal

For articles based on large, real-world datasets, the Lancet Group will now require that editors ensure that at least one peer reviewer is “knowledgeable about the details of the dataset being reported and can understand its strengths and limitations in relation to the question being addressed.”

For studies that use “very large datasets,” the editors are now required to ensure that, in addition to a statistical peer review, a review from an “expert in data science” is obtained. Reviewers will also be explicitly asked if they have “concerns about research integrity or publication ethics regarding the manuscript they are reviewing.”

Although these changes are encouraging, Harlan Krumholz, MD, professor of medicine (cardiology), Yale University, New Haven, Conn., is not convinced that they are realistic.

Dr. Krumholz, who is also the founder and director of the Yale New Haven Hospital Center for Outcome Research and Evaluation, said in an interview that “large, real-world datasets” are of two varieties. Datasets drawn from publicly available sources, such as Medicare or Medicaid health records, are utterly transparent.

By contrast, Surgisphere was a privately owned database, and “it is not unusual for privately owned databases to have proprietary data from multiple sources that the company may choose to keep confidential,” Dr. Krumholz said.

He noted that several large datasets are widely used for research purposes, such as IBM, Optum, and Komodo – a data analytics company that recently entered into partnership with a fourth company, PicnicHealth.

These companies receive deidentified electronic health records from health systems and insurers nationwide. Komodo boasts “real-time and longitudinal data on more than 325 million patients, representing more than 65 billion clinical encounters with 15 million new encounters added daily.”

“One has to raise an eyebrow – how were these data acquired? And, given that the U.S. has a population of around 328 million people, is it really plausible that a single company has health records of almost the entire U.S. population?” Dr. Krumholz commented. (A spokesperson for Komodo said in an interview that the company has records on 325 million U.S. patients.)

This is “an issue across the board with ‘real-world evidence,’ which is that it’s like the ‘Wild West’ – the transparencies of private databases are less than optimal and there are no common standards to help us move forward,” Dr. Krumholz said, noting that there is “no external authority overseeing, validating, or auditing these databases. In the end, we are trusting the companies.”

Although the Food and Drug Administration has laid out a framework for how real-world data and real-world evidence can be used to advance scientific research, the FDA does not oversee the databases.

“Thus, there is no ‘good housekeeping seal’ that a peer reviewer or author would be in a position to evaluate,” Dr. Krumholz said. “No journal can do an audit of these types of private databases, so ultimately, it boils down to trust.”

Nevertheless, there were red flags with Surgisphere, Dr. Rao pointed out. Unlike more established and widely used databases, the Surgisphere database had been catapulted from relative obscurity onto center stage, which should have given researchers pause.

AI-assisted peer review

A series of investigative reports by The Guardian raised questions about Sapan Desai, the CEO of Surgisphere, including the fact that hospitals purporting to have contributed data to Surgisphere had never heard of the company.

However, peer reviewers are not expected to be investigative reporters, explained Dr. Malički.

“In an ideal world, editors and peer reviewers would have a chance to look at raw data or would have a certificate from the academic institution the authors are affiliated with that the data have been inspected by the institution, but in the real world, of course, this does not happen,” he said.

Artificial intelligence software is being developed and deployed to assist in the peer review process, Dr. Malički noted. In July 2020, Frontiers Science News debuted its Artificial Intelligence Review Assistant to help editors, reviewers, and authors evaluate the quality of a manuscript. The program can make up to 20 recommendations, including “the assessment of language quality, the detection of plagiarism, and identification of potential conflicts of interest.” The program is now in use in all 103 journals published by Frontiers. Preliminary software is also available to detect statistical errors.

Another system under development is FAIRware, an initiative of the Research on Research Institute in partnership with the Stanford Center for Biomedical Informatics Research. The partnership’s goal is to “develop an automated online tool (or suite of tools) to help researchers ensure that the datasets they produce are ‘FAIR’ at the point of creation,” said Dr. Malički, referring to the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR) guiding principles for data management. The principles aim to increase the ability of machines to automatically find and use the data, as well as to support its reuse by individuals.

He added that these advanced tools cannot replace human reviewers, who will “likely always be a necessary quality check in the process.”

Greater transparency needed

Another limitation of peer review is the reviewers themselves, according to Dr. Malički. “It’s a step in the right direction that The Lancet is now requesting a peer reviewer with expertise in big datasets, but it does not go far enough to increase accountability of peer reviewers,” he said.

Dr. Malički is the co–editor-in-chief of the journal Research Integrity and Peer Review , which has “an open and transparent review process – meaning that we reveal the names of the reviewers to the public and we publish the full review report alongside the paper.” The publication also allows the authors to make public the original version they sent.

Dr. Malički cited several advantages to transparent peer review, particularly the increased accountability that results from placing potential conflicts of interest under the microscope.

As for the concern that identifying the reviewers might soften the review process, “there is little evidence to substantiate that concern,” he added.

Dr. Malički emphasized that making reviews public “is not a problem – people voice strong opinions at conferences and elsewhere. The question remains, who gets to decide if the criticism has been adequately addressed, so that the findings of the study still stand?”

He acknowledged that, “as in politics and on many social platforms, rage, hatred, and personal attacks divert the discussion from the topic at hand, which is why a good moderator is needed.”

A journal editor or a moderator at a scientific conference may be tasked with “stopping all talk not directly related to the topic.”

Widening the circle of scrutiny

Dr. Malički added: “A published paper should not be considered the ‘final word,’ even if it has gone through peer review and is published in a reputable journal. The peer-review process means that a limited number of people have seen the study.”

Once the study is published, “the whole world gets to see it and criticize it, and that widens the circle of scrutiny.”

One classic way to raise concerns about a study post publication is to write a letter to the journal editor. But there is no guarantee that the letter will be published or the authors notified of the feedback.

Dr. Malički encourages readers to use PubPeer, an online forum in which members of the public can post comments on scientific studies and articles.

Once a comment is posted, the authors are alerted. “There is no ‘police department’ that forces authors to acknowledge comments or forces journal editors to take action, but at least PubPeer guarantees that readers’ messages will reach the authors and – depending on how many people raise similar issues – the comments can lead to errata or even full retractions,” he said.

PubPeer was key in pointing out errors in a suspect study from France (which did not involve Surgisphere) that supported the use of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19.

A message to policy makers

High stakes are involved in ensuring the integrity of scientific publications: The French government revoked a decree that allowed hospitals to prescribe hydroxychloroquine for certain COVID-19 patients.

After the Surgisphere Lancet article, the World Health Organization temporarily halted enrollment in the hydroxychloroquine component of the Solidarity international randomized trial of medications to treat COVID-19.

Similarly, the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency instructed the organizers of COPCOV, an international trial of the use of hydroxychloroquine as prophylaxis against COVID-19, to suspend recruitment of patients. The SOLIDARITY trial briefly resumed, but that arm of the trial was ultimately suspended after a preliminary analysis suggested that hydroxychloroquine provided no benefit for patients with COVID-19.

Dr. Malički emphasized that governments and organizations should not “blindly trust journal articles” and make policy decisions based exclusively on study findings in published journals – even with the current improvements in the peer review process – without having their own experts conduct a thorough review of the data.

“If you are not willing to do your own due diligence, then at least be brave enough and say transparently why you are making this policy, or any other changes, and clearly state if your decision is based primarily or solely on the fact that ‘X’ study was published in ‘Y’ journal,” he stated.

Dr. Rao believes that the most important take-home message of the Surgisphere scandal is “that we should be skeptical and do our own due diligence about the kinds of data published – a responsibility that applies to all of us, whether we are investigators, editors at journals, the press, scientists, and readers.”

Dr. Rao reported being on the steering committee of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored MINT trial and the Bayer-sponsored PACIFIC AMI trial. Dr. Malički reports being a postdoc at METRICS Stanford in the past 3 years. Dr. Krumholz received expenses and/or personal fees from UnitedHealth, Element Science, Aetna, Facebook, the Siegfried and Jensen Law Firm, Arnold and Porter Law Firm, Martin/Baughman Law Firm, F-Prime, and the National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases in Beijing. He is an owner of Refactor Health and HugoHealth and had grants and/or contracts from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the FDA, Johnson & Johnson, and the Shenzhen Center for Health Information.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In May 2020, two major scientific journals published and subsequently retracted studies that relied on data provided by the now-disgraced data analytics company Surgisphere.

One of the studies, published in The Lancet, reported an association between the antimalarial drugs hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine and increased in-hospital mortality and cardiac arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19. The second study, which appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine, described an association between underlying cardiovascular disease, but not related drug therapy, with increased mortality in COVID-19 patients.

The retractions in June 2020 followed an open letter to each publication penned by scientists, ethicists, and clinicians who flagged serious methodological and ethical anomalies in the data used in the studies.

On the 1-year anniversary, researchers and journal editors spoke about what was learned to reduce the risk of something like this happening again.

“The Surgisphere incident served as a wake-up call for everyone involved with scientific research to make sure that data have integrity and are robust,” Sunil Rao, MD, professor of medicine, Duke University Health System, Durham, N.C., and editor-in-chief of Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions, said in an interview.

“I’m sure this isn’t going to be the last incident of this nature, and we have to be vigilant about new datasets or datasets that we haven’t heard of as having a track record of publication,” Dr. Rao said.

Spotlight on authors

The editors of the Lancet Group responded to the “wake-up call” with a statement, Learning From a Retraction, which announced changes to reduce the risks of research and publication misconduct.

The changes affect multiple phases of the publication process. For example, the declaration form that authors must sign “will require that more than one author has directly accessed and verified the data reported in the manuscript.” Additionally, when a research article is the result of an academic and commercial partnership – as was the case in the two retracted studies – “one of the authors named as having accessed and verified data must be from the academic team.”

This was particularly important because it appears that the academic coauthors of the retracted studies did not have access to the data provided by Surgisphere, a private commercial entity.

Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, William Harvey Distinguished Chair in Advanced Cardiovascular Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, who was the lead author of both studies, declined to be interviewed for this article. In a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine editors requesting that the article be retracted, he wrote: “Because all the authors were not granted access to the raw data and the raw data could not be made available to a third-party auditor, we are unable to validate the primary data sources underlying our article.”

In a similar communication with The Lancet, Dr. Mehra wrote even more pointedly that, in light of the refusal of Surgisphere to make the data available to the third-party auditor, “we can no longer vouch for the veracity of the primary data sources.”

“It is very disturbing that the authors were willing to put their names on a paper without ever seeing and verifying the data,” Mario Malički, MD, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at METRICS at Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview. “Saying that they could ‘no longer vouch’ suggests that at one point they could vouch for it. Most likely they took its existence and veracity entirely on trust.”

Dr. Malički pointed out that one of the four criteria of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors for being an author on a study is the “agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.”

The new policies put forth by The Lancet are “encouraging,” but perhaps do not go far enough. “Every author, not only one or two authors, should personally take responsibility for the integrity of data,” he stated.

Many journals “adhere to ICMJE rules in principle and have checkboxes for authors to confirm that they guarantee the veracity of the data.” However, they “do not have the resources to verify the authors’ statements.”

Ideally, “it is the institutions where the researchers work that should guarantee the veracity of the raw data – but I do not know any university or institute that does this,” he said.

No ‘good-housekeeping’ seal

For articles based on large, real-world datasets, the Lancet Group will now require that editors ensure that at least one peer reviewer is “knowledgeable about the details of the dataset being reported and can understand its strengths and limitations in relation to the question being addressed.”

For studies that use “very large datasets,” the editors are now required to ensure that, in addition to a statistical peer review, a review from an “expert in data science” is obtained. Reviewers will also be explicitly asked if they have “concerns about research integrity or publication ethics regarding the manuscript they are reviewing.”

Although these changes are encouraging, Harlan Krumholz, MD, professor of medicine (cardiology), Yale University, New Haven, Conn., is not convinced that they are realistic.

Dr. Krumholz, who is also the founder and director of the Yale New Haven Hospital Center for Outcome Research and Evaluation, said in an interview that “large, real-world datasets” are of two varieties. Datasets drawn from publicly available sources, such as Medicare or Medicaid health records, are utterly transparent.

By contrast, Surgisphere was a privately owned database, and “it is not unusual for privately owned databases to have proprietary data from multiple sources that the company may choose to keep confidential,” Dr. Krumholz said.

He noted that several large datasets are widely used for research purposes, such as IBM, Optum, and Komodo – a data analytics company that recently entered into partnership with a fourth company, PicnicHealth.

These companies receive deidentified electronic health records from health systems and insurers nationwide. Komodo boasts “real-time and longitudinal data on more than 325 million patients, representing more than 65 billion clinical encounters with 15 million new encounters added daily.”

“One has to raise an eyebrow – how were these data acquired? And, given that the U.S. has a population of around 328 million people, is it really plausible that a single company has health records of almost the entire U.S. population?” Dr. Krumholz commented. (A spokesperson for Komodo said in an interview that the company has records on 325 million U.S. patients.)

This is “an issue across the board with ‘real-world evidence,’ which is that it’s like the ‘Wild West’ – the transparencies of private databases are less than optimal and there are no common standards to help us move forward,” Dr. Krumholz said, noting that there is “no external authority overseeing, validating, or auditing these databases. In the end, we are trusting the companies.”

Although the Food and Drug Administration has laid out a framework for how real-world data and real-world evidence can be used to advance scientific research, the FDA does not oversee the databases.

“Thus, there is no ‘good housekeeping seal’ that a peer reviewer or author would be in a position to evaluate,” Dr. Krumholz said. “No journal can do an audit of these types of private databases, so ultimately, it boils down to trust.”

Nevertheless, there were red flags with Surgisphere, Dr. Rao pointed out. Unlike more established and widely used databases, the Surgisphere database had been catapulted from relative obscurity onto center stage, which should have given researchers pause.

AI-assisted peer review

A series of investigative reports by The Guardian raised questions about Sapan Desai, the CEO of Surgisphere, including the fact that hospitals purporting to have contributed data to Surgisphere had never heard of the company.

However, peer reviewers are not expected to be investigative reporters, explained Dr. Malički.

“In an ideal world, editors and peer reviewers would have a chance to look at raw data or would have a certificate from the academic institution the authors are affiliated with that the data have been inspected by the institution, but in the real world, of course, this does not happen,” he said.

Artificial intelligence software is being developed and deployed to assist in the peer review process, Dr. Malički noted. In July 2020, Frontiers Science News debuted its Artificial Intelligence Review Assistant to help editors, reviewers, and authors evaluate the quality of a manuscript. The program can make up to 20 recommendations, including “the assessment of language quality, the detection of plagiarism, and identification of potential conflicts of interest.” The program is now in use in all 103 journals published by Frontiers. Preliminary software is also available to detect statistical errors.

Another system under development is FAIRware, an initiative of the Research on Research Institute in partnership with the Stanford Center for Biomedical Informatics Research. The partnership’s goal is to “develop an automated online tool (or suite of tools) to help researchers ensure that the datasets they produce are ‘FAIR’ at the point of creation,” said Dr. Malički, referring to the findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (FAIR) guiding principles for data management. The principles aim to increase the ability of machines to automatically find and use the data, as well as to support its reuse by individuals.

He added that these advanced tools cannot replace human reviewers, who will “likely always be a necessary quality check in the process.”

Greater transparency needed

Another limitation of peer review is the reviewers themselves, according to Dr. Malički. “It’s a step in the right direction that The Lancet is now requesting a peer reviewer with expertise in big datasets, but it does not go far enough to increase accountability of peer reviewers,” he said.

Dr. Malički is the co–editor-in-chief of the journal Research Integrity and Peer Review , which has “an open and transparent review process – meaning that we reveal the names of the reviewers to the public and we publish the full review report alongside the paper.” The publication also allows the authors to make public the original version they sent.

Dr. Malički cited several advantages to transparent peer review, particularly the increased accountability that results from placing potential conflicts of interest under the microscope.

As for the concern that identifying the reviewers might soften the review process, “there is little evidence to substantiate that concern,” he added.

Dr. Malički emphasized that making reviews public “is not a problem – people voice strong opinions at conferences and elsewhere. The question remains, who gets to decide if the criticism has been adequately addressed, so that the findings of the study still stand?”