User login

Fewer transplants for MM with quadruplet therapy?

“It is not a big leap of faith to imagine that, in the near future, with the availability of quadruplets and T-cell therapies, the role of high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant will be diminished,” said Dickran Kazandjian, MD, and Ola Landgren, MD, PhD, of the myeloma division, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami.

They commented in a editorial in JAMA Oncology, prompted by a paper describing new results with a novel quadruple combination of therapies. These treatments included the monoclonal antibody elotuzumab (Empliciti) added onto the established backbone of carfilzomib (Kyprolis), lenalidomide (Revlimid), and dexamethasone (known as KRd).

“Regardless of what the future holds for elotuzumab-based combinations, it is clear that the new treatment paradigm of newly diagnosed MM will incorporate antibody-based quadruplet regimens,” the editorialists commented.

“Novel immunotherapies are here to stay,” they added, “as they are already transforming the lives of patients with multiple MM and bringing a bright horizon to the treatment landscape.”

Study details

The trial of the novel quadruplet regimen was a multicenter, single-arm, phase 2 study that involved 46 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, explain first author Benjamin A. Derman, MD, of the University of Chicago Medical Center, and colleagues.

These patients had a median age of 62; more than two-thirds were male (72%) and White (70%). About half (48%) had high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities.

All patients were treated with 12 cycles of the quadruple therapy Elo-KRd regimen. They underwent bone marrow assessment of measurable residual disease (MRD; with 10-5 sensitivity) after cycle 8 and cycle 12.

“An MRD-adapted treatment approach is rational because it may identify which patients can be administered shorter courses of intensive therapy without compromising efficacy,” the authors explained.

Patients who had MRD negativity at both time points did not receive further Elo-KRd, while patients who converted from MRD positivity to negativity in between cycles 8 and 12 received 6 additional cycles of Elo-KRd. Those who remained MRD positive or converted to positivity after 12 cycles received an additional 12 cycles of Elo-KRd.

Following Elo-KRd treatment, all patients transitioned to triple therapy with Elo-Rd (with no carfilzomib), for indefinite maintenance therapy or until disease progression.

For the primary endpoint, the rate of stringent complete response and/or MRD-negativity after cycle 8 was 58% (26 of 45), meeting the predefined definition of efficacy.

Importantly, 26% of patients converted from MRD positivity after cycle 8 to negativity at a later time point, while 50% of patients reached 1-year sustained MRD negativity.

Overall, the estimated 3-year, progression-free survival was 72%, and the rate was 92% for patients with MRD-negativity at cycle 8. The overall survival rate was 78%.

The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were lung and nonpulmonary infections (13% and 11%, respectively), and one patient had a grade 5 MI. Three patients discontinued the treatment because of intolerance.

“An MRD-adapted design using elotuzumab and weekly KRd without autologous stem cell transplantation showed a high rate of stringent complete response (sCR) and/or MRD-negativity and durable responses,” the authors wrote.

“This approach provides support for further evaluation of MRD-guided de-escalation of therapy to decrease treatment exposure while sustaining deep responses.”

To better assess the difference of the therapy versus treatment including stem cell transplantation, a phase 3, randomized trial is currently underway to compare the Elo-KRd regimen against KRd with autologous stem cell transplant in newly diagnosed MM.

“If Elo-KRd proves superior, a randomized comparison of Elo versus anti-CD38 mAb-based quadruplets would help determine the optimal combination of therapies in the frontline setting,” the authors noted.

Randomized trial anticipated to clarify benefit

In their editorial, Dr. Kazandjian and Dr. Landgren agreed with the authors that the role of elotuzumab needs to be better clarified in a randomized trial setting.

Elotuzumab received FDA approval in 2015 based on results from the ELOQUENT-2 study, which showed improved progression-free survival and overall survival with the addition of elotuzumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma who have previously received one to three other therapies.

However, the editorialists pointed out that recently published results from the randomized ELOQUENT-1 trial of lenalidomide and dexamethasone with and without elotuzumab showed the addition of elotuzumab was not associated with a statistically significant difference in progression-free survival.

The editorialists also pointed out that, in the setting of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, another recent, similarly designed study found that the backbone regimen of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone – on its own – was also associated with a favorable MRD-negative rate of 62%.

In addition, several studies involving novel quadruple treatments with the monoclonal antibody daratumumab (Darzalex) instead of elotuzumab, have also shown benefit in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, resulting in high rates of MRD negativity.

Collectively, the findings bode well for the quadruple regimens in the treatment of MM, the editorialists emphasized.

“Importantly, with the rate of deep remissions observed with antibody-based quadruplet therapies, one may question the role of using early high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant in every patient, especially in those who have achieved MRD negativity with the quadruplet alone,” they added.

The study was sponsored in part by Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and the Multiple Myeloma Research Consortium. Dr. Derman reported advisory board fees from Sanofi, Janssen, and COTA Healthcare; honoraria from PleXus Communications and MJH Life Sciences. Dr. Kazandjian declares receiving advisory board or consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, and Arcellx outside the submitted work. Dr. Landgren has received grant support from numerous organizations and pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Landgren has also received honoraria for scientific talks/participated in advisory boards for Adaptive Biotech, Amgen, Binding Site, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Cellectis, Glenmark, Janssen, Juno, and Pfizer, and served on independent data monitoring committees for international randomized trials by Takeda, Merck, Janssen, and Theradex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“It is not a big leap of faith to imagine that, in the near future, with the availability of quadruplets and T-cell therapies, the role of high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant will be diminished,” said Dickran Kazandjian, MD, and Ola Landgren, MD, PhD, of the myeloma division, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami.

They commented in a editorial in JAMA Oncology, prompted by a paper describing new results with a novel quadruple combination of therapies. These treatments included the monoclonal antibody elotuzumab (Empliciti) added onto the established backbone of carfilzomib (Kyprolis), lenalidomide (Revlimid), and dexamethasone (known as KRd).

“Regardless of what the future holds for elotuzumab-based combinations, it is clear that the new treatment paradigm of newly diagnosed MM will incorporate antibody-based quadruplet regimens,” the editorialists commented.

“Novel immunotherapies are here to stay,” they added, “as they are already transforming the lives of patients with multiple MM and bringing a bright horizon to the treatment landscape.”

Study details

The trial of the novel quadruplet regimen was a multicenter, single-arm, phase 2 study that involved 46 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, explain first author Benjamin A. Derman, MD, of the University of Chicago Medical Center, and colleagues.

These patients had a median age of 62; more than two-thirds were male (72%) and White (70%). About half (48%) had high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities.

All patients were treated with 12 cycles of the quadruple therapy Elo-KRd regimen. They underwent bone marrow assessment of measurable residual disease (MRD; with 10-5 sensitivity) after cycle 8 and cycle 12.

“An MRD-adapted treatment approach is rational because it may identify which patients can be administered shorter courses of intensive therapy without compromising efficacy,” the authors explained.

Patients who had MRD negativity at both time points did not receive further Elo-KRd, while patients who converted from MRD positivity to negativity in between cycles 8 and 12 received 6 additional cycles of Elo-KRd. Those who remained MRD positive or converted to positivity after 12 cycles received an additional 12 cycles of Elo-KRd.

Following Elo-KRd treatment, all patients transitioned to triple therapy with Elo-Rd (with no carfilzomib), for indefinite maintenance therapy or until disease progression.

For the primary endpoint, the rate of stringent complete response and/or MRD-negativity after cycle 8 was 58% (26 of 45), meeting the predefined definition of efficacy.

Importantly, 26% of patients converted from MRD positivity after cycle 8 to negativity at a later time point, while 50% of patients reached 1-year sustained MRD negativity.

Overall, the estimated 3-year, progression-free survival was 72%, and the rate was 92% for patients with MRD-negativity at cycle 8. The overall survival rate was 78%.

The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were lung and nonpulmonary infections (13% and 11%, respectively), and one patient had a grade 5 MI. Three patients discontinued the treatment because of intolerance.

“An MRD-adapted design using elotuzumab and weekly KRd without autologous stem cell transplantation showed a high rate of stringent complete response (sCR) and/or MRD-negativity and durable responses,” the authors wrote.

“This approach provides support for further evaluation of MRD-guided de-escalation of therapy to decrease treatment exposure while sustaining deep responses.”

To better assess the difference of the therapy versus treatment including stem cell transplantation, a phase 3, randomized trial is currently underway to compare the Elo-KRd regimen against KRd with autologous stem cell transplant in newly diagnosed MM.

“If Elo-KRd proves superior, a randomized comparison of Elo versus anti-CD38 mAb-based quadruplets would help determine the optimal combination of therapies in the frontline setting,” the authors noted.

Randomized trial anticipated to clarify benefit

In their editorial, Dr. Kazandjian and Dr. Landgren agreed with the authors that the role of elotuzumab needs to be better clarified in a randomized trial setting.

Elotuzumab received FDA approval in 2015 based on results from the ELOQUENT-2 study, which showed improved progression-free survival and overall survival with the addition of elotuzumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma who have previously received one to three other therapies.

However, the editorialists pointed out that recently published results from the randomized ELOQUENT-1 trial of lenalidomide and dexamethasone with and without elotuzumab showed the addition of elotuzumab was not associated with a statistically significant difference in progression-free survival.

The editorialists also pointed out that, in the setting of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, another recent, similarly designed study found that the backbone regimen of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone – on its own – was also associated with a favorable MRD-negative rate of 62%.

In addition, several studies involving novel quadruple treatments with the monoclonal antibody daratumumab (Darzalex) instead of elotuzumab, have also shown benefit in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, resulting in high rates of MRD negativity.

Collectively, the findings bode well for the quadruple regimens in the treatment of MM, the editorialists emphasized.

“Importantly, with the rate of deep remissions observed with antibody-based quadruplet therapies, one may question the role of using early high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant in every patient, especially in those who have achieved MRD negativity with the quadruplet alone,” they added.

The study was sponsored in part by Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and the Multiple Myeloma Research Consortium. Dr. Derman reported advisory board fees from Sanofi, Janssen, and COTA Healthcare; honoraria from PleXus Communications and MJH Life Sciences. Dr. Kazandjian declares receiving advisory board or consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, and Arcellx outside the submitted work. Dr. Landgren has received grant support from numerous organizations and pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Landgren has also received honoraria for scientific talks/participated in advisory boards for Adaptive Biotech, Amgen, Binding Site, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Cellectis, Glenmark, Janssen, Juno, and Pfizer, and served on independent data monitoring committees for international randomized trials by Takeda, Merck, Janssen, and Theradex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“It is not a big leap of faith to imagine that, in the near future, with the availability of quadruplets and T-cell therapies, the role of high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant will be diminished,” said Dickran Kazandjian, MD, and Ola Landgren, MD, PhD, of the myeloma division, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Miami.

They commented in a editorial in JAMA Oncology, prompted by a paper describing new results with a novel quadruple combination of therapies. These treatments included the monoclonal antibody elotuzumab (Empliciti) added onto the established backbone of carfilzomib (Kyprolis), lenalidomide (Revlimid), and dexamethasone (known as KRd).

“Regardless of what the future holds for elotuzumab-based combinations, it is clear that the new treatment paradigm of newly diagnosed MM will incorporate antibody-based quadruplet regimens,” the editorialists commented.

“Novel immunotherapies are here to stay,” they added, “as they are already transforming the lives of patients with multiple MM and bringing a bright horizon to the treatment landscape.”

Study details

The trial of the novel quadruplet regimen was a multicenter, single-arm, phase 2 study that involved 46 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, explain first author Benjamin A. Derman, MD, of the University of Chicago Medical Center, and colleagues.

These patients had a median age of 62; more than two-thirds were male (72%) and White (70%). About half (48%) had high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities.

All patients were treated with 12 cycles of the quadruple therapy Elo-KRd regimen. They underwent bone marrow assessment of measurable residual disease (MRD; with 10-5 sensitivity) after cycle 8 and cycle 12.

“An MRD-adapted treatment approach is rational because it may identify which patients can be administered shorter courses of intensive therapy without compromising efficacy,” the authors explained.

Patients who had MRD negativity at both time points did not receive further Elo-KRd, while patients who converted from MRD positivity to negativity in between cycles 8 and 12 received 6 additional cycles of Elo-KRd. Those who remained MRD positive or converted to positivity after 12 cycles received an additional 12 cycles of Elo-KRd.

Following Elo-KRd treatment, all patients transitioned to triple therapy with Elo-Rd (with no carfilzomib), for indefinite maintenance therapy or until disease progression.

For the primary endpoint, the rate of stringent complete response and/or MRD-negativity after cycle 8 was 58% (26 of 45), meeting the predefined definition of efficacy.

Importantly, 26% of patients converted from MRD positivity after cycle 8 to negativity at a later time point, while 50% of patients reached 1-year sustained MRD negativity.

Overall, the estimated 3-year, progression-free survival was 72%, and the rate was 92% for patients with MRD-negativity at cycle 8. The overall survival rate was 78%.

The most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were lung and nonpulmonary infections (13% and 11%, respectively), and one patient had a grade 5 MI. Three patients discontinued the treatment because of intolerance.

“An MRD-adapted design using elotuzumab and weekly KRd without autologous stem cell transplantation showed a high rate of stringent complete response (sCR) and/or MRD-negativity and durable responses,” the authors wrote.

“This approach provides support for further evaluation of MRD-guided de-escalation of therapy to decrease treatment exposure while sustaining deep responses.”

To better assess the difference of the therapy versus treatment including stem cell transplantation, a phase 3, randomized trial is currently underway to compare the Elo-KRd regimen against KRd with autologous stem cell transplant in newly diagnosed MM.

“If Elo-KRd proves superior, a randomized comparison of Elo versus anti-CD38 mAb-based quadruplets would help determine the optimal combination of therapies in the frontline setting,” the authors noted.

Randomized trial anticipated to clarify benefit

In their editorial, Dr. Kazandjian and Dr. Landgren agreed with the authors that the role of elotuzumab needs to be better clarified in a randomized trial setting.

Elotuzumab received FDA approval in 2015 based on results from the ELOQUENT-2 study, which showed improved progression-free survival and overall survival with the addition of elotuzumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma who have previously received one to three other therapies.

However, the editorialists pointed out that recently published results from the randomized ELOQUENT-1 trial of lenalidomide and dexamethasone with and without elotuzumab showed the addition of elotuzumab was not associated with a statistically significant difference in progression-free survival.

The editorialists also pointed out that, in the setting of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, another recent, similarly designed study found that the backbone regimen of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone – on its own – was also associated with a favorable MRD-negative rate of 62%.

In addition, several studies involving novel quadruple treatments with the monoclonal antibody daratumumab (Darzalex) instead of elotuzumab, have also shown benefit in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma, resulting in high rates of MRD negativity.

Collectively, the findings bode well for the quadruple regimens in the treatment of MM, the editorialists emphasized.

“Importantly, with the rate of deep remissions observed with antibody-based quadruplet therapies, one may question the role of using early high-dose melphalan and autologous stem cell transplant in every patient, especially in those who have achieved MRD negativity with the quadruplet alone,” they added.

The study was sponsored in part by Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and the Multiple Myeloma Research Consortium. Dr. Derman reported advisory board fees from Sanofi, Janssen, and COTA Healthcare; honoraria from PleXus Communications and MJH Life Sciences. Dr. Kazandjian declares receiving advisory board or consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, and Arcellx outside the submitted work. Dr. Landgren has received grant support from numerous organizations and pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Landgren has also received honoraria for scientific talks/participated in advisory boards for Adaptive Biotech, Amgen, Binding Site, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Cellectis, Glenmark, Janssen, Juno, and Pfizer, and served on independent data monitoring committees for international randomized trials by Takeda, Merck, Janssen, and Theradex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Evusheld for COVID-19: Lifesaving and free, but still few takers

Evusheld (AstraZeneca), a medication used to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients at high risk, has problems: Namely, that supplies of the potentially lifesaving drug outweigh demand.

At least 7 million people who are immunocompromised could benefit from it, as could many others who are undergoing cancer treatment, have received a transplant, or who are allergic to the COVID-19 vaccines. The medication has laboratory-produced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and helps the body protect itself. It can slash the chances of becoming infected by 77%, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

And it’s free to eligible patients (although there may be an out-of-pocket administrative fee in some cases).

To meet demand, the Biden administration secured 1.7 million doses of the medicine, which was granted emergency use authorization by the FDA in December 2021. As of July 25, however, 793,348 doses have been ordered by the administration sites, and only 398,181 doses have been reported as used, a spokesperson for the Department of Health & Human Services tells this news organization.

Each week, a certain amount of doses from the 1.7 million dose stockpile is made available to state and territorial health departments. States have not been asking for their full allotment, the spokesperson said July 28.

Now, HHS and AstraZeneca have taken a number of steps to increase awareness of the medication and access to it.

- On July 27, HHS announced that individual providers and smaller sites of care that don’t currently receive Evusheld through the federal distribution process via the HHS Health Partner Order Portal can now order up to three patient courses of the medicine. These can be

- Health care providers can use the HHS’s COVID-19 Therapeutics Locator to find Evusheld in their area.

- AstraZeneca has launched a new website with educational materials and says it is working closely with patient and professional groups to inform patients and health care providers.

- A direct-to-consumer ad launched on June 22 and will run in the United States online and on TV (Yahoo, Fox, CBS Sports, MSN, ESPN) and be amplified on social and digital channels through year’s end, an AstraZeneca spokesperson said in an interview.

- AstraZeneca set up a toll-free number for providers: 1-833-EVUSHLD.

Evusheld includes two monoclonal antibodies, tixagevimab and cilgavimab. The medication is given as two consecutive intramuscular injections during a single visit to a doctor’s office, infusion center, or other health care facility. The antibodies bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and prevent the virus from getting into human cells and infecting them. It’s authorized for use in children and adults aged 12 years and older who weigh at least 88 pounds.

Studies have found that the medication decreases the risk of getting COVID-19 for up to 6 months after it is given. The FDA recommends repeat dosing every 6 months with the doses of 300 mg of each monoclonal antibody. In clinical trials, Evusheld reduced the incidence of COVID-19 symptomatic illness by 77%, compared with placebo.

Physicians monitor patients for an hour after administering Evusheld for allergic reactions. Other possible side effects include cardiac events, but they are not common.

Doctors and patients weigh in

Physicians – and patients – from the United States to the United Kingdom and beyond are questioning why the medication is underused while lauding the recent efforts to expand access and increase awareness.

The U.S. federal government may have underestimated the amount of communication needed to increase awareness of the medication and its applications, said infectious disease specialist William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn.

“HHS hasn’t made a major educational effort to promote it,” he said in an interview.

Many physicians who need to know about it, such as transplant doctors and rheumatologists, are outside the typical public health communications loop, he said.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Transational Institute and editor-in-chief of Medscape, has taken to social media to bemoan the lack of awareness.

Another infectious disease expert agrees. “In my experience, the awareness of Evusheld is low amongst many patients as well as many providers,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore.

“Initially, there were scarce supplies of the drug, and certain hospital systems tiered eligibility based on degrees of immunosuppression, and only the most immunosuppressed were proactively approached for treatment.”

“Also, many community hospitals never initially ordered Evusheld – they may have been crowded out by academic centers who treat many more immunosuppressed patients and may not currently see it as a priority,” Dr. Adalja said in an interview. “As such, many immunosuppressed patients would have to seek treatment at academic medical centers, where the drug is more likely to be available.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Evusheld (AstraZeneca), a medication used to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients at high risk, has problems: Namely, that supplies of the potentially lifesaving drug outweigh demand.

At least 7 million people who are immunocompromised could benefit from it, as could many others who are undergoing cancer treatment, have received a transplant, or who are allergic to the COVID-19 vaccines. The medication has laboratory-produced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and helps the body protect itself. It can slash the chances of becoming infected by 77%, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

And it’s free to eligible patients (although there may be an out-of-pocket administrative fee in some cases).

To meet demand, the Biden administration secured 1.7 million doses of the medicine, which was granted emergency use authorization by the FDA in December 2021. As of July 25, however, 793,348 doses have been ordered by the administration sites, and only 398,181 doses have been reported as used, a spokesperson for the Department of Health & Human Services tells this news organization.

Each week, a certain amount of doses from the 1.7 million dose stockpile is made available to state and territorial health departments. States have not been asking for their full allotment, the spokesperson said July 28.

Now, HHS and AstraZeneca have taken a number of steps to increase awareness of the medication and access to it.

- On July 27, HHS announced that individual providers and smaller sites of care that don’t currently receive Evusheld through the federal distribution process via the HHS Health Partner Order Portal can now order up to three patient courses of the medicine. These can be

- Health care providers can use the HHS’s COVID-19 Therapeutics Locator to find Evusheld in their area.

- AstraZeneca has launched a new website with educational materials and says it is working closely with patient and professional groups to inform patients and health care providers.

- A direct-to-consumer ad launched on June 22 and will run in the United States online and on TV (Yahoo, Fox, CBS Sports, MSN, ESPN) and be amplified on social and digital channels through year’s end, an AstraZeneca spokesperson said in an interview.

- AstraZeneca set up a toll-free number for providers: 1-833-EVUSHLD.

Evusheld includes two monoclonal antibodies, tixagevimab and cilgavimab. The medication is given as two consecutive intramuscular injections during a single visit to a doctor’s office, infusion center, or other health care facility. The antibodies bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and prevent the virus from getting into human cells and infecting them. It’s authorized for use in children and adults aged 12 years and older who weigh at least 88 pounds.

Studies have found that the medication decreases the risk of getting COVID-19 for up to 6 months after it is given. The FDA recommends repeat dosing every 6 months with the doses of 300 mg of each monoclonal antibody. In clinical trials, Evusheld reduced the incidence of COVID-19 symptomatic illness by 77%, compared with placebo.

Physicians monitor patients for an hour after administering Evusheld for allergic reactions. Other possible side effects include cardiac events, but they are not common.

Doctors and patients weigh in

Physicians – and patients – from the United States to the United Kingdom and beyond are questioning why the medication is underused while lauding the recent efforts to expand access and increase awareness.

The U.S. federal government may have underestimated the amount of communication needed to increase awareness of the medication and its applications, said infectious disease specialist William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn.

“HHS hasn’t made a major educational effort to promote it,” he said in an interview.

Many physicians who need to know about it, such as transplant doctors and rheumatologists, are outside the typical public health communications loop, he said.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Transational Institute and editor-in-chief of Medscape, has taken to social media to bemoan the lack of awareness.

Another infectious disease expert agrees. “In my experience, the awareness of Evusheld is low amongst many patients as well as many providers,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore.

“Initially, there were scarce supplies of the drug, and certain hospital systems tiered eligibility based on degrees of immunosuppression, and only the most immunosuppressed were proactively approached for treatment.”

“Also, many community hospitals never initially ordered Evusheld – they may have been crowded out by academic centers who treat many more immunosuppressed patients and may not currently see it as a priority,” Dr. Adalja said in an interview. “As such, many immunosuppressed patients would have to seek treatment at academic medical centers, where the drug is more likely to be available.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Evusheld (AstraZeneca), a medication used to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients at high risk, has problems: Namely, that supplies of the potentially lifesaving drug outweigh demand.

At least 7 million people who are immunocompromised could benefit from it, as could many others who are undergoing cancer treatment, have received a transplant, or who are allergic to the COVID-19 vaccines. The medication has laboratory-produced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and helps the body protect itself. It can slash the chances of becoming infected by 77%, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

And it’s free to eligible patients (although there may be an out-of-pocket administrative fee in some cases).

To meet demand, the Biden administration secured 1.7 million doses of the medicine, which was granted emergency use authorization by the FDA in December 2021. As of July 25, however, 793,348 doses have been ordered by the administration sites, and only 398,181 doses have been reported as used, a spokesperson for the Department of Health & Human Services tells this news organization.

Each week, a certain amount of doses from the 1.7 million dose stockpile is made available to state and territorial health departments. States have not been asking for their full allotment, the spokesperson said July 28.

Now, HHS and AstraZeneca have taken a number of steps to increase awareness of the medication and access to it.

- On July 27, HHS announced that individual providers and smaller sites of care that don’t currently receive Evusheld through the federal distribution process via the HHS Health Partner Order Portal can now order up to three patient courses of the medicine. These can be

- Health care providers can use the HHS’s COVID-19 Therapeutics Locator to find Evusheld in their area.

- AstraZeneca has launched a new website with educational materials and says it is working closely with patient and professional groups to inform patients and health care providers.

- A direct-to-consumer ad launched on June 22 and will run in the United States online and on TV (Yahoo, Fox, CBS Sports, MSN, ESPN) and be amplified on social and digital channels through year’s end, an AstraZeneca spokesperson said in an interview.

- AstraZeneca set up a toll-free number for providers: 1-833-EVUSHLD.

Evusheld includes two monoclonal antibodies, tixagevimab and cilgavimab. The medication is given as two consecutive intramuscular injections during a single visit to a doctor’s office, infusion center, or other health care facility. The antibodies bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and prevent the virus from getting into human cells and infecting them. It’s authorized for use in children and adults aged 12 years and older who weigh at least 88 pounds.

Studies have found that the medication decreases the risk of getting COVID-19 for up to 6 months after it is given. The FDA recommends repeat dosing every 6 months with the doses of 300 mg of each monoclonal antibody. In clinical trials, Evusheld reduced the incidence of COVID-19 symptomatic illness by 77%, compared with placebo.

Physicians monitor patients for an hour after administering Evusheld for allergic reactions. Other possible side effects include cardiac events, but they are not common.

Doctors and patients weigh in

Physicians – and patients – from the United States to the United Kingdom and beyond are questioning why the medication is underused while lauding the recent efforts to expand access and increase awareness.

The U.S. federal government may have underestimated the amount of communication needed to increase awareness of the medication and its applications, said infectious disease specialist William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn.

“HHS hasn’t made a major educational effort to promote it,” he said in an interview.

Many physicians who need to know about it, such as transplant doctors and rheumatologists, are outside the typical public health communications loop, he said.

Eric Topol, MD, director of the Scripps Research Transational Institute and editor-in-chief of Medscape, has taken to social media to bemoan the lack of awareness.

Another infectious disease expert agrees. “In my experience, the awareness of Evusheld is low amongst many patients as well as many providers,” said Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore.

“Initially, there were scarce supplies of the drug, and certain hospital systems tiered eligibility based on degrees of immunosuppression, and only the most immunosuppressed were proactively approached for treatment.”

“Also, many community hospitals never initially ordered Evusheld – they may have been crowded out by academic centers who treat many more immunosuppressed patients and may not currently see it as a priority,” Dr. Adalja said in an interview. “As such, many immunosuppressed patients would have to seek treatment at academic medical centers, where the drug is more likely to be available.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pig heart transplants and the ethical challenges that lie ahead

The long-struggling field of cardiac xenotransplantation has had a very good year.

In January, the University of Maryland made history by keeping a 57-year-old man deemed too sick for a human heart transplant alive for 2 months with a genetically engineered pig heart. On July 12, New York University surgeons reported that heart function was “completely normal with excellent contractility” in two brain-dead patients with pig hearts beating in their chests for 72 hours.

The NYU team approached the project with a decedent model in mind and, after discussions with their IRB equivalent, settled on a 72-hour window because that’s the time they typically keep people ventilated when trying to place their organs, explained Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

“There’s no real ethical argument for that,” he said in an interview. The consideration is what the family is willing to do when trying to balance doing “something very altruistic and good versus having closure.”

Some families have religious beliefs that burial or interment has to occur very rapidly, whereas others, including one of the family donors, were willing to have the research go on much longer, Dr. Montgomery said. Indeed, the next protocol is being written to consider maintaining the bodies for 2-4 weeks.

“People do vary and you have to kind of accommodate that variation,” he said. “For some people, this isn’t going to be what they’re going to want and that’s why you have to go through the consent process.”

Informed authorization

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of medical ethics at the NYU Langone Medical Center, said the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act recognizes an individual’s right to be an organ donor for transplant and research, but it “mentions nothing about maintaining you in a dead state artificially for research purposes.”

“It’s a major shift in what people are thinking about doing when they die or their relatives die,” he said.

Because organ donation is controlled at the state, not federal, level, the possibility of donating organs for xenotransplantation, like medical aid in dying, will vary between states, observed Dr. Caplan. The best way to ensure that patients whose organs are found to be unsuitable for transplantation have the option is to change state laws.

He noted that cases are already springing up where people are requesting postmortem sperm or egg donations without direct consents from the person who died. “So we have this new area opening up of handling the use of the dead body and we need to bring the law into sync with the possibilities that are out there.”

In terms of informed authorization (informed consent is reserved for the living), Dr. Caplan said there should be written evidence the person wanted to be a donor and, while not required by law, all survivors should give their permission and understand what’s going to be done in terms of the experiment, such as the use of animal parts, when the body will be returned, and the possibility of zoonotic viral infection.

“They have to fully accept that the person is dead and we’re just maintaining them artificially,” he said. “There’s no maintaining anyone who’s alive. That’s a source of a lot of confusion.”

Special committees also need to be appointed with voices from people in organ procurement, law, theology, and patient groups to monitor practice to ensure people who have given permission understood the process, that families have their questions answered independent of the research team, and that clear limits are set on how long experiments will last.

As to what those limits should be: “I think in terms of a week or 2,” Dr. Caplan said. “Obviously we could maintain bodies longer and people have. But I think, culturally in our society, going much past that starts to perhaps stress emotionally, psychologically, family and friends about getting closure.”

“I’m not as comfortable when people say things like, ‘How about 2 months?’ ” he said. “That’s a long time to sort of accept the fact that somebody has died but you can’t complete all the things that go along with the death.”

Dr. Caplan is also uncomfortable with the use of one-off emergency authorizations, as used for Maryland resident David Bennett Sr., who was rejected for standard heart transplantation and required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive.

“It’s too premature, I believe, even to try and rescue someone,” he said. “We need to learn more from the deceased models.”

A better model

Dr. Montgomery noted that primates are very imperfect models for predicting what’s going to happen in humans, and that in order to do xenotransplantation in living humans, there are only two pathways – the one-off emergency authorization or a clinical phase 1 trial.

The decedent model, he said, “will make human trials safer because it’s an intermediate step. You don’t have a living human’s life on the line when you’re trying to do iterative changes and improve the procedure.”

The team, for example, omitted a perfusion pump that was used in the Maryland case and would likely have made its way into phase 1 trials based on baboon data that suggested it was important to have the heart on the pump for hours before it was transplanted, he said. “We didn’t do any of that. We just did it like we would do a regular heart transplant and it started right up, immediately, and started to work.”

The researchers did not release details on the immunosuppression regimen, but noted that, unlike Maryland, they also did not use the experimental anti-CD40 antibody to tamp down the recipients’ immune system.

Although Mr. Bennett’s autopsy did not show any conventional sign of graft rejection, the transplanted pig heart was infected with porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) and Mr. Bennett showed traces of DNA from PCMV in his circulation.

Nailing down safety

Dr. Montgomery said he wouldn’t rule out xenotransplantation in a living human, but that the safety issues need to be nailed down. “I think that the tests used on the pig that was the donor for the Bennett case were not sensitive enough for latent virus, and that’s how it slipped through. So there was a bit of going back to the drawing board, really looking at each of the tests, and being sure we had the sensitivity to pick up a latent virus.”

He noted that United Therapeutics, which funded the research and provided the engineered pigs through its subsidiary Revivicor, has created and validated a more sensitive polymerase chain reaction test that covers some 35 different pathogens, microbes, and parasites. NYU has also developed its own platform to repeat the testing and for monitoring after the transplant. “The ones that we’re currently using would have picked up the virus.”

Stuart Russell, MD, a professor of medicine who specializes in advanced HF at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said “the biggest thing from my perspective is those two amazing families that were willing let this happen. ... If 20 years from now, this is what we’re doing, it’s related to these families being this generous at a really tough time in their lives.”

Dr. Russell said he awaits publication of the data on what the pathology of the heart looks like, but that the experiments “help to give us a lot of reassurance that we don’t need to worry about hyperacute rejection,” which by definition is going to happen in the first 24-48 hours.

That said, longer-term data is essential to potential safety issues. Notably, among the 10 genetic modifications made to the pigs, four were porcine gene knockouts, including a growth hormone receptor knockout to prevent abnormal organ growth inside the recipient’s chest. As a result, the organs seem to be small for the age of the pig and just don’t grow that well, admitted Dr. Montgomery, who said they are currently analyzing this with echocardiography.

Dr. Russell said this may create a sizing issue, but also “if you have a heart that’s more stressed in the pig, from the point of being a donor, maybe it’s not as good a heart as if it was growing normally. But that kind of stuff, I think, is going to take more than two cases and longer-term data to sort out.”

Sharon Hunt, MD, professor emerita, Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center, and past president of the International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation, said it’s not the technical aspects, but the biology of xenotransplantation that’s really daunting.

“It’s not the physical act of doing it, like they needed a bigger heart or a smaller heart. Those are technical problems but they’ll manage them,” she said. “The big problem is biological – and the bottom line is we don’t really know. We may have overcome hyperacute rejection, which is great, but the rest remains to be seen.”

Dr. Hunt, who worked with heart transplantation pioneer Norman Shumway, MD, and spent decades caring for patients after transplantation, said most families will consent to 24 or 48 hours or even a week of experimentation on a brain-dead loved one, but what the transplant community wants to know is whether this is workable for many months.

“So the fact that the xenotransplant works for 72 hours, yeah, that’s groovy. But, you know, the answer is kind of ‘so what,’ ” she said. “I’d like to see this go for months, like they were trying to do in the human in Maryland.”

For phase 1 trials, even longer-term survival with or without rejection or with rejection that’s treatable is needed, Dr. Hunt suggested.

“We haven’t seen that yet. The Maryland people were very valiant but they lost the cause,” she said. “There’s just so much more to do before we have a viable model to start anything like a phase 1 trial. I’d love it if that happens in my lifetime, but I’m not sure it’s going to.”

Dr. Russell and Dr. Hunt reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Caplan reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The long-struggling field of cardiac xenotransplantation has had a very good year.

In January, the University of Maryland made history by keeping a 57-year-old man deemed too sick for a human heart transplant alive for 2 months with a genetically engineered pig heart. On July 12, New York University surgeons reported that heart function was “completely normal with excellent contractility” in two brain-dead patients with pig hearts beating in their chests for 72 hours.

The NYU team approached the project with a decedent model in mind and, after discussions with their IRB equivalent, settled on a 72-hour window because that’s the time they typically keep people ventilated when trying to place their organs, explained Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

“There’s no real ethical argument for that,” he said in an interview. The consideration is what the family is willing to do when trying to balance doing “something very altruistic and good versus having closure.”

Some families have religious beliefs that burial or interment has to occur very rapidly, whereas others, including one of the family donors, were willing to have the research go on much longer, Dr. Montgomery said. Indeed, the next protocol is being written to consider maintaining the bodies for 2-4 weeks.

“People do vary and you have to kind of accommodate that variation,” he said. “For some people, this isn’t going to be what they’re going to want and that’s why you have to go through the consent process.”

Informed authorization

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of medical ethics at the NYU Langone Medical Center, said the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act recognizes an individual’s right to be an organ donor for transplant and research, but it “mentions nothing about maintaining you in a dead state artificially for research purposes.”

“It’s a major shift in what people are thinking about doing when they die or their relatives die,” he said.

Because organ donation is controlled at the state, not federal, level, the possibility of donating organs for xenotransplantation, like medical aid in dying, will vary between states, observed Dr. Caplan. The best way to ensure that patients whose organs are found to be unsuitable for transplantation have the option is to change state laws.

He noted that cases are already springing up where people are requesting postmortem sperm or egg donations without direct consents from the person who died. “So we have this new area opening up of handling the use of the dead body and we need to bring the law into sync with the possibilities that are out there.”

In terms of informed authorization (informed consent is reserved for the living), Dr. Caplan said there should be written evidence the person wanted to be a donor and, while not required by law, all survivors should give their permission and understand what’s going to be done in terms of the experiment, such as the use of animal parts, when the body will be returned, and the possibility of zoonotic viral infection.

“They have to fully accept that the person is dead and we’re just maintaining them artificially,” he said. “There’s no maintaining anyone who’s alive. That’s a source of a lot of confusion.”

Special committees also need to be appointed with voices from people in organ procurement, law, theology, and patient groups to monitor practice to ensure people who have given permission understood the process, that families have their questions answered independent of the research team, and that clear limits are set on how long experiments will last.

As to what those limits should be: “I think in terms of a week or 2,” Dr. Caplan said. “Obviously we could maintain bodies longer and people have. But I think, culturally in our society, going much past that starts to perhaps stress emotionally, psychologically, family and friends about getting closure.”

“I’m not as comfortable when people say things like, ‘How about 2 months?’ ” he said. “That’s a long time to sort of accept the fact that somebody has died but you can’t complete all the things that go along with the death.”

Dr. Caplan is also uncomfortable with the use of one-off emergency authorizations, as used for Maryland resident David Bennett Sr., who was rejected for standard heart transplantation and required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive.

“It’s too premature, I believe, even to try and rescue someone,” he said. “We need to learn more from the deceased models.”

A better model

Dr. Montgomery noted that primates are very imperfect models for predicting what’s going to happen in humans, and that in order to do xenotransplantation in living humans, there are only two pathways – the one-off emergency authorization or a clinical phase 1 trial.

The decedent model, he said, “will make human trials safer because it’s an intermediate step. You don’t have a living human’s life on the line when you’re trying to do iterative changes and improve the procedure.”

The team, for example, omitted a perfusion pump that was used in the Maryland case and would likely have made its way into phase 1 trials based on baboon data that suggested it was important to have the heart on the pump for hours before it was transplanted, he said. “We didn’t do any of that. We just did it like we would do a regular heart transplant and it started right up, immediately, and started to work.”

The researchers did not release details on the immunosuppression regimen, but noted that, unlike Maryland, they also did not use the experimental anti-CD40 antibody to tamp down the recipients’ immune system.

Although Mr. Bennett’s autopsy did not show any conventional sign of graft rejection, the transplanted pig heart was infected with porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) and Mr. Bennett showed traces of DNA from PCMV in his circulation.

Nailing down safety

Dr. Montgomery said he wouldn’t rule out xenotransplantation in a living human, but that the safety issues need to be nailed down. “I think that the tests used on the pig that was the donor for the Bennett case were not sensitive enough for latent virus, and that’s how it slipped through. So there was a bit of going back to the drawing board, really looking at each of the tests, and being sure we had the sensitivity to pick up a latent virus.”

He noted that United Therapeutics, which funded the research and provided the engineered pigs through its subsidiary Revivicor, has created and validated a more sensitive polymerase chain reaction test that covers some 35 different pathogens, microbes, and parasites. NYU has also developed its own platform to repeat the testing and for monitoring after the transplant. “The ones that we’re currently using would have picked up the virus.”

Stuart Russell, MD, a professor of medicine who specializes in advanced HF at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said “the biggest thing from my perspective is those two amazing families that were willing let this happen. ... If 20 years from now, this is what we’re doing, it’s related to these families being this generous at a really tough time in their lives.”

Dr. Russell said he awaits publication of the data on what the pathology of the heart looks like, but that the experiments “help to give us a lot of reassurance that we don’t need to worry about hyperacute rejection,” which by definition is going to happen in the first 24-48 hours.

That said, longer-term data is essential to potential safety issues. Notably, among the 10 genetic modifications made to the pigs, four were porcine gene knockouts, including a growth hormone receptor knockout to prevent abnormal organ growth inside the recipient’s chest. As a result, the organs seem to be small for the age of the pig and just don’t grow that well, admitted Dr. Montgomery, who said they are currently analyzing this with echocardiography.

Dr. Russell said this may create a sizing issue, but also “if you have a heart that’s more stressed in the pig, from the point of being a donor, maybe it’s not as good a heart as if it was growing normally. But that kind of stuff, I think, is going to take more than two cases and longer-term data to sort out.”

Sharon Hunt, MD, professor emerita, Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center, and past president of the International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation, said it’s not the technical aspects, but the biology of xenotransplantation that’s really daunting.

“It’s not the physical act of doing it, like they needed a bigger heart or a smaller heart. Those are technical problems but they’ll manage them,” she said. “The big problem is biological – and the bottom line is we don’t really know. We may have overcome hyperacute rejection, which is great, but the rest remains to be seen.”

Dr. Hunt, who worked with heart transplantation pioneer Norman Shumway, MD, and spent decades caring for patients after transplantation, said most families will consent to 24 or 48 hours or even a week of experimentation on a brain-dead loved one, but what the transplant community wants to know is whether this is workable for many months.

“So the fact that the xenotransplant works for 72 hours, yeah, that’s groovy. But, you know, the answer is kind of ‘so what,’ ” she said. “I’d like to see this go for months, like they were trying to do in the human in Maryland.”

For phase 1 trials, even longer-term survival with or without rejection or with rejection that’s treatable is needed, Dr. Hunt suggested.

“We haven’t seen that yet. The Maryland people were very valiant but they lost the cause,” she said. “There’s just so much more to do before we have a viable model to start anything like a phase 1 trial. I’d love it if that happens in my lifetime, but I’m not sure it’s going to.”

Dr. Russell and Dr. Hunt reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Caplan reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The long-struggling field of cardiac xenotransplantation has had a very good year.

In January, the University of Maryland made history by keeping a 57-year-old man deemed too sick for a human heart transplant alive for 2 months with a genetically engineered pig heart. On July 12, New York University surgeons reported that heart function was “completely normal with excellent contractility” in two brain-dead patients with pig hearts beating in their chests for 72 hours.

The NYU team approached the project with a decedent model in mind and, after discussions with their IRB equivalent, settled on a 72-hour window because that’s the time they typically keep people ventilated when trying to place their organs, explained Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

“There’s no real ethical argument for that,” he said in an interview. The consideration is what the family is willing to do when trying to balance doing “something very altruistic and good versus having closure.”

Some families have religious beliefs that burial or interment has to occur very rapidly, whereas others, including one of the family donors, were willing to have the research go on much longer, Dr. Montgomery said. Indeed, the next protocol is being written to consider maintaining the bodies for 2-4 weeks.

“People do vary and you have to kind of accommodate that variation,” he said. “For some people, this isn’t going to be what they’re going to want and that’s why you have to go through the consent process.”

Informed authorization

Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, director of medical ethics at the NYU Langone Medical Center, said the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act recognizes an individual’s right to be an organ donor for transplant and research, but it “mentions nothing about maintaining you in a dead state artificially for research purposes.”

“It’s a major shift in what people are thinking about doing when they die or their relatives die,” he said.

Because organ donation is controlled at the state, not federal, level, the possibility of donating organs for xenotransplantation, like medical aid in dying, will vary between states, observed Dr. Caplan. The best way to ensure that patients whose organs are found to be unsuitable for transplantation have the option is to change state laws.

He noted that cases are already springing up where people are requesting postmortem sperm or egg donations without direct consents from the person who died. “So we have this new area opening up of handling the use of the dead body and we need to bring the law into sync with the possibilities that are out there.”

In terms of informed authorization (informed consent is reserved for the living), Dr. Caplan said there should be written evidence the person wanted to be a donor and, while not required by law, all survivors should give their permission and understand what’s going to be done in terms of the experiment, such as the use of animal parts, when the body will be returned, and the possibility of zoonotic viral infection.

“They have to fully accept that the person is dead and we’re just maintaining them artificially,” he said. “There’s no maintaining anyone who’s alive. That’s a source of a lot of confusion.”

Special committees also need to be appointed with voices from people in organ procurement, law, theology, and patient groups to monitor practice to ensure people who have given permission understood the process, that families have their questions answered independent of the research team, and that clear limits are set on how long experiments will last.

As to what those limits should be: “I think in terms of a week or 2,” Dr. Caplan said. “Obviously we could maintain bodies longer and people have. But I think, culturally in our society, going much past that starts to perhaps stress emotionally, psychologically, family and friends about getting closure.”

“I’m not as comfortable when people say things like, ‘How about 2 months?’ ” he said. “That’s a long time to sort of accept the fact that somebody has died but you can’t complete all the things that go along with the death.”

Dr. Caplan is also uncomfortable with the use of one-off emergency authorizations, as used for Maryland resident David Bennett Sr., who was rejected for standard heart transplantation and required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive.

“It’s too premature, I believe, even to try and rescue someone,” he said. “We need to learn more from the deceased models.”

A better model

Dr. Montgomery noted that primates are very imperfect models for predicting what’s going to happen in humans, and that in order to do xenotransplantation in living humans, there are only two pathways – the one-off emergency authorization or a clinical phase 1 trial.

The decedent model, he said, “will make human trials safer because it’s an intermediate step. You don’t have a living human’s life on the line when you’re trying to do iterative changes and improve the procedure.”

The team, for example, omitted a perfusion pump that was used in the Maryland case and would likely have made its way into phase 1 trials based on baboon data that suggested it was important to have the heart on the pump for hours before it was transplanted, he said. “We didn’t do any of that. We just did it like we would do a regular heart transplant and it started right up, immediately, and started to work.”

The researchers did not release details on the immunosuppression regimen, but noted that, unlike Maryland, they also did not use the experimental anti-CD40 antibody to tamp down the recipients’ immune system.

Although Mr. Bennett’s autopsy did not show any conventional sign of graft rejection, the transplanted pig heart was infected with porcine cytomegalovirus (PCMV) and Mr. Bennett showed traces of DNA from PCMV in his circulation.

Nailing down safety

Dr. Montgomery said he wouldn’t rule out xenotransplantation in a living human, but that the safety issues need to be nailed down. “I think that the tests used on the pig that was the donor for the Bennett case were not sensitive enough for latent virus, and that’s how it slipped through. So there was a bit of going back to the drawing board, really looking at each of the tests, and being sure we had the sensitivity to pick up a latent virus.”

He noted that United Therapeutics, which funded the research and provided the engineered pigs through its subsidiary Revivicor, has created and validated a more sensitive polymerase chain reaction test that covers some 35 different pathogens, microbes, and parasites. NYU has also developed its own platform to repeat the testing and for monitoring after the transplant. “The ones that we’re currently using would have picked up the virus.”

Stuart Russell, MD, a professor of medicine who specializes in advanced HF at Duke University, Durham, N.C., said “the biggest thing from my perspective is those two amazing families that were willing let this happen. ... If 20 years from now, this is what we’re doing, it’s related to these families being this generous at a really tough time in their lives.”

Dr. Russell said he awaits publication of the data on what the pathology of the heart looks like, but that the experiments “help to give us a lot of reassurance that we don’t need to worry about hyperacute rejection,” which by definition is going to happen in the first 24-48 hours.

That said, longer-term data is essential to potential safety issues. Notably, among the 10 genetic modifications made to the pigs, four were porcine gene knockouts, including a growth hormone receptor knockout to prevent abnormal organ growth inside the recipient’s chest. As a result, the organs seem to be small for the age of the pig and just don’t grow that well, admitted Dr. Montgomery, who said they are currently analyzing this with echocardiography.

Dr. Russell said this may create a sizing issue, but also “if you have a heart that’s more stressed in the pig, from the point of being a donor, maybe it’s not as good a heart as if it was growing normally. But that kind of stuff, I think, is going to take more than two cases and longer-term data to sort out.”

Sharon Hunt, MD, professor emerita, Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center, and past president of the International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation, said it’s not the technical aspects, but the biology of xenotransplantation that’s really daunting.

“It’s not the physical act of doing it, like they needed a bigger heart or a smaller heart. Those are technical problems but they’ll manage them,” she said. “The big problem is biological – and the bottom line is we don’t really know. We may have overcome hyperacute rejection, which is great, but the rest remains to be seen.”

Dr. Hunt, who worked with heart transplantation pioneer Norman Shumway, MD, and spent decades caring for patients after transplantation, said most families will consent to 24 or 48 hours or even a week of experimentation on a brain-dead loved one, but what the transplant community wants to know is whether this is workable for many months.

“So the fact that the xenotransplant works for 72 hours, yeah, that’s groovy. But, you know, the answer is kind of ‘so what,’ ” she said. “I’d like to see this go for months, like they were trying to do in the human in Maryland.”

For phase 1 trials, even longer-term survival with or without rejection or with rejection that’s treatable is needed, Dr. Hunt suggested.

“We haven’t seen that yet. The Maryland people were very valiant but they lost the cause,” she said. “There’s just so much more to do before we have a viable model to start anything like a phase 1 trial. I’d love it if that happens in my lifetime, but I’m not sure it’s going to.”

Dr. Russell and Dr. Hunt reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Caplan reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position) and is a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Transplanted pig hearts functioned normally in deceased persons on ventilator support

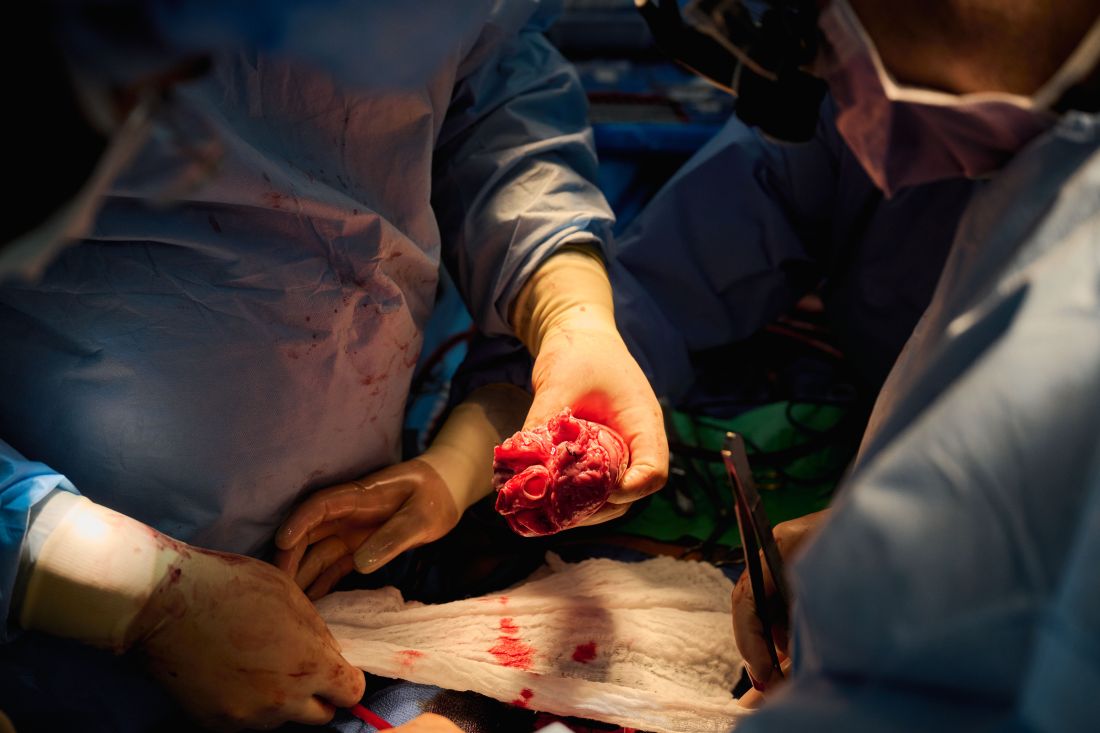

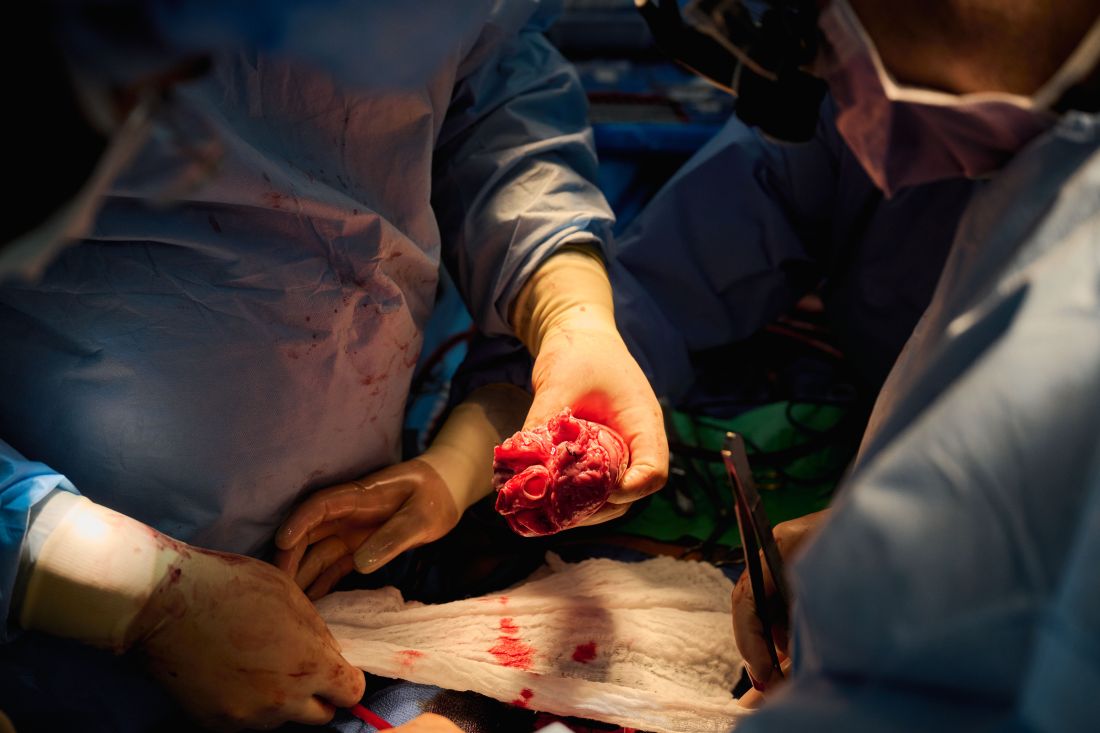

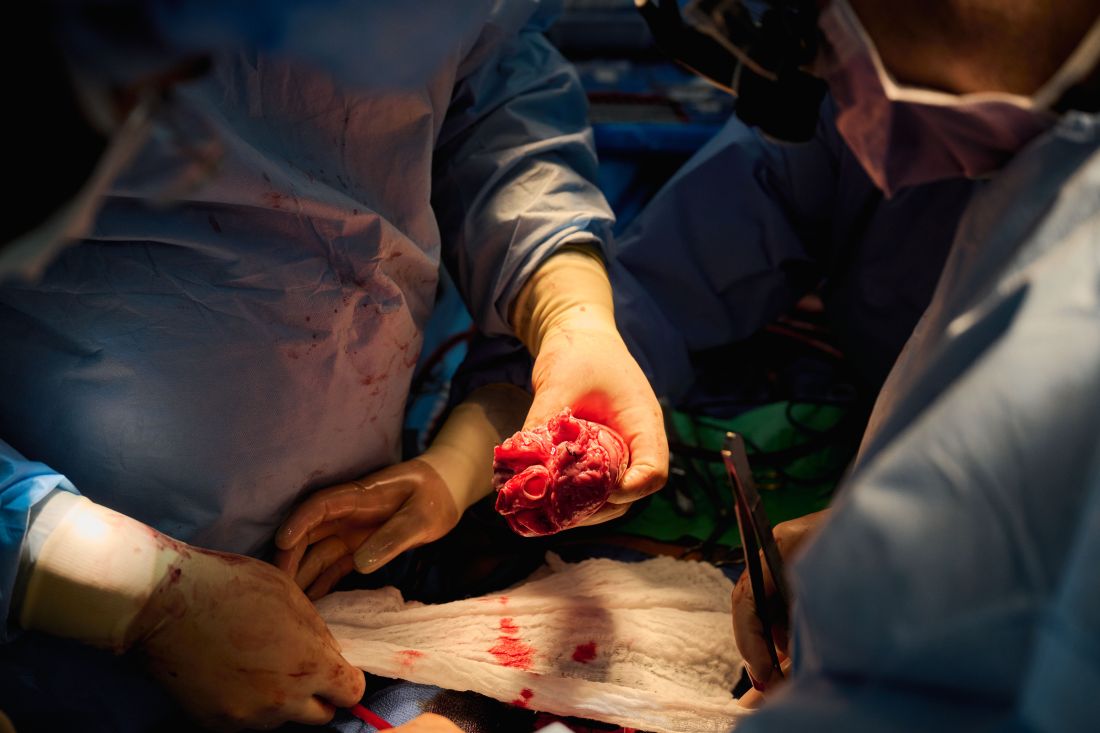

A team of surgeons successfully transplanted genetically engineered pig hearts into two recently deceased people whose bodies were being maintained on ventilatory support – not in the hope of restoring life, but as a proof-of-concept experiment in xenotransplantation that could eventually help to ease the critical shortage of donor organs.

The surgeries were performed on June 16 and July 6, 2022, using porcine hearts from animals genetically engineered to prevent organ rejection and promote adaptive immunity by human recipients

without utilizing unapproved devices or techniques or medications,” said Nader Moazami, MD, surgical director of heart transplantation and chief of the division of heart and lung transplantation and mechanical circulatory support at NYU Langone Health, New York.

Through 72 hours of postoperative monitoring “we evaluated the heart for functionality and the heart function was completely normal with excellent contractility,” he said at a press briefing announcing early results of the experimental program.

He acknowledged that for the first of the two procedures some surgical modification of the pig heart was required, primarily because of size differences between the donor and recipient.

“Nevertheless, we learned a tremendous amount from the first operation, and when that experience was translated into the second operation it even performed better,” he said.

Alex Reyentovich, MD, medical director of heart transplantation and director of the NYU Langone advanced heart failure program noted that “there are 6 million individuals with heart failure in the United States. About 100,000 of those individuals have end-stage heart failure, and we only do about 3,500 heart transplants a year in the United States, so we have a tremendous deficiency in organs, and there are many people dying waiting for a heart.”

Infection protocols

To date there has been only one xenotransplant of a genetically modified pig heart into a living human recipient, David Bennett Sr., age 57. The surgery, performed at the University of Maryland in January 2022, was initially successful, with the patient able to sit up in bed a few days after the procedure, and the heart performing like a “rock star” according to transplant surgeon Bartley Griffith, MD.

However, Mr. Bennett died 2 months after the procedure from compromise of the organ by an as yet undetermined cause, of which one may have been the heart's infection by porcine cytomegalovirus (CMV).

The NYU team, mindful of this potential setback, used more sensitive assays to screen the donor organs for porcine CMV, and implemented protocols to prevent and to monitor for potential zoonotic transmission of porcine endogenous retrovirus.

The procedure used a dedicated operating room and equipment that will not be used for clinical procedures, the team emphasized.

An organ transplant specialist who was not involved in the study commented that there can be unwelcome surprises even with the most rigorous infection prophylaxis protocols.

“I think these are important steps, but they don’t resolve the question of infectious risk. Sometimes viruses or latent infections are only manifested later,” said Jay A. Fishman, MD, associate director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Transplant Center and director of the transplant infectious diseases and compromised host program at the hospital, which is in Boston.

“I think these are important steps, but as you may recall from the Maryland heart transplant experience, when porcine cytomegalovirus was activated, it was a long way into that patient’s course, and so we just don’t know whether something would have been reactivated later,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Fishman noted that experience with xenotransplantation at the University of Maryland and other centers has suggested that immunosuppressive regimens used for human-to-human transplants may not be suited for animal-to-human grafts.

The hearts were taken from pigs genetically modified with knockouts of four porcine genes to prevent rejection – including a gene for a growth hormone that would otherwise cause the heart to continue to expand in the recipient’s chest – and with the addition of six human transgenes encoding for expression of proteins regulating biologic pathways that might be disrupted by incompatibilities across species.

Vietnam veteran

The organ recipients were recently deceased patients who had expressed the clear wish to be organ donors but whose organs were for clinical reasons unsuitable for transplant.

The first recipient was Lawrence Kelly, a Vietnam War veteran and welder who died from heart failure at the age of 72.

“He was an organ donor, and would be so happy to know how much his contribution to this research will help people like him with this heart disease. He was a hero his whole life, and he went out a hero,” said Alice Michael, Mr. Kelly’s partner of 33 years, who also spoke at the briefing.

“It was, I think, one of the most incredible things to see a pig heart pounding away and beating inside the chest of a human being,” said Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Transplant Institute, and himself a heart transplant recipient.

Dr. Fishman said he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was updated on 7/12/22 and 7/14/22.

A team of surgeons successfully transplanted genetically engineered pig hearts into two recently deceased people whose bodies were being maintained on ventilatory support – not in the hope of restoring life, but as a proof-of-concept experiment in xenotransplantation that could eventually help to ease the critical shortage of donor organs.

The surgeries were performed on June 16 and July 6, 2022, using porcine hearts from animals genetically engineered to prevent organ rejection and promote adaptive immunity by human recipients

without utilizing unapproved devices or techniques or medications,” said Nader Moazami, MD, surgical director of heart transplantation and chief of the division of heart and lung transplantation and mechanical circulatory support at NYU Langone Health, New York.

Through 72 hours of postoperative monitoring “we evaluated the heart for functionality and the heart function was completely normal with excellent contractility,” he said at a press briefing announcing early results of the experimental program.

He acknowledged that for the first of the two procedures some surgical modification of the pig heart was required, primarily because of size differences between the donor and recipient.

“Nevertheless, we learned a tremendous amount from the first operation, and when that experience was translated into the second operation it even performed better,” he said.

Alex Reyentovich, MD, medical director of heart transplantation and director of the NYU Langone advanced heart failure program noted that “there are 6 million individuals with heart failure in the United States. About 100,000 of those individuals have end-stage heart failure, and we only do about 3,500 heart transplants a year in the United States, so we have a tremendous deficiency in organs, and there are many people dying waiting for a heart.”

Infection protocols

To date there has been only one xenotransplant of a genetically modified pig heart into a living human recipient, David Bennett Sr., age 57. The surgery, performed at the University of Maryland in January 2022, was initially successful, with the patient able to sit up in bed a few days after the procedure, and the heart performing like a “rock star” according to transplant surgeon Bartley Griffith, MD.

However, Mr. Bennett died 2 months after the procedure from compromise of the organ by an as yet undetermined cause, of which one may have been the heart's infection by porcine cytomegalovirus (CMV).

The NYU team, mindful of this potential setback, used more sensitive assays to screen the donor organs for porcine CMV, and implemented protocols to prevent and to monitor for potential zoonotic transmission of porcine endogenous retrovirus.

The procedure used a dedicated operating room and equipment that will not be used for clinical procedures, the team emphasized.

An organ transplant specialist who was not involved in the study commented that there can be unwelcome surprises even with the most rigorous infection prophylaxis protocols.

“I think these are important steps, but they don’t resolve the question of infectious risk. Sometimes viruses or latent infections are only manifested later,” said Jay A. Fishman, MD, associate director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Transplant Center and director of the transplant infectious diseases and compromised host program at the hospital, which is in Boston.

“I think these are important steps, but as you may recall from the Maryland heart transplant experience, when porcine cytomegalovirus was activated, it was a long way into that patient’s course, and so we just don’t know whether something would have been reactivated later,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Fishman noted that experience with xenotransplantation at the University of Maryland and other centers has suggested that immunosuppressive regimens used for human-to-human transplants may not be suited for animal-to-human grafts.

The hearts were taken from pigs genetically modified with knockouts of four porcine genes to prevent rejection – including a gene for a growth hormone that would otherwise cause the heart to continue to expand in the recipient’s chest – and with the addition of six human transgenes encoding for expression of proteins regulating biologic pathways that might be disrupted by incompatibilities across species.

Vietnam veteran

The organ recipients were recently deceased patients who had expressed the clear wish to be organ donors but whose organs were for clinical reasons unsuitable for transplant.

The first recipient was Lawrence Kelly, a Vietnam War veteran and welder who died from heart failure at the age of 72.

“He was an organ donor, and would be so happy to know how much his contribution to this research will help people like him with this heart disease. He was a hero his whole life, and he went out a hero,” said Alice Michael, Mr. Kelly’s partner of 33 years, who also spoke at the briefing.

“It was, I think, one of the most incredible things to see a pig heart pounding away and beating inside the chest of a human being,” said Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, director of the NYU Transplant Institute, and himself a heart transplant recipient.

Dr. Fishman said he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was updated on 7/12/22 and 7/14/22.

A team of surgeons successfully transplanted genetically engineered pig hearts into two recently deceased people whose bodies were being maintained on ventilatory support – not in the hope of restoring life, but as a proof-of-concept experiment in xenotransplantation that could eventually help to ease the critical shortage of donor organs.

The surgeries were performed on June 16 and July 6, 2022, using porcine hearts from animals genetically engineered to prevent organ rejection and promote adaptive immunity by human recipients

without utilizing unapproved devices or techniques or medications,” said Nader Moazami, MD, surgical director of heart transplantation and chief of the division of heart and lung transplantation and mechanical circulatory support at NYU Langone Health, New York.

Through 72 hours of postoperative monitoring “we evaluated the heart for functionality and the heart function was completely normal with excellent contractility,” he said at a press briefing announcing early results of the experimental program.

He acknowledged that for the first of the two procedures some surgical modification of the pig heart was required, primarily because of size differences between the donor and recipient.

“Nevertheless, we learned a tremendous amount from the first operation, and when that experience was translated into the second operation it even performed better,” he said.