User login

Parent concerns a factor when treating eczema in children with darker skin types

NEW YORK –

Skin diseases pose a greater risk of both hyper- and hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types, but the fear and concern that this raises for permanent disfigurement is not limited to Blacks, Dr. Heath, assistant professor of pediatric dermatology at Temple University, Philadelphia, said at the Skin of Color Update 2023.

“Culturally, pigmentation changes can be huge. For people of Indian descent, for example, pigmentary changes like light spots on the skin might be an obstacle to marriage, so it can really be life changing,” she added.

In patients with darker skin tones presenting with an inflammatory skin disease, such as AD or psoriasis, Dr. Heath advised asking specifically about change in skin tone even if it is not readily apparent. In pediatric patients, it is also appropriate to include parents in this conversation.

Consider the parent’s perspective

“When you are taking care of a child or adolescent, the patient is likely to be concerned about changes in pigmentation, but it is important to remember that the adult in the room might have had their own journey with brown skin and has dealt with the burden of pigment changes,” Dr. Heath said.

For the parent, the pigmentation changes, rather than the inflammation, might be the governing issue and the reason that he or she brought the child to the clinician. Dr. Heath suggested that it is important for caregivers to explicitly recognize their concern, explain that addressing the pigmentary changes is part of the treatment plan, and to create realistic expectations about how long pigmentary changes will take to resolve.

As an example, Dr. Heath recounted a difficult case of a Black infant with disseminated hyperpigmentation and features that did not preclude pathology other than AD. Dr. Heath created a multifaceted treatment plan to address the inflammation in distinct areas of the body that included low-strength topical steroids for the face, stronger steroids for the body, and advice on scalp and skin care.

“I thought this was a great treatment plan out of the gate – I was covering all of the things on my differential list – I thought that the mom would be thinking, this doctor is amazing,” Dr. Heath said.

Pigmentary changes are a priority

However, that was not what the patient’s mother was thinking. Having failed to explicitly recognize her concern about the pigmentation changes and how the treatment would address this issue, the mother was disappointed.

“She had one question: Will my baby ever be one color? That was her main concern,” said Dr. Heath, indicating that other clinicians seeing inflammatory diseases in children with darker skin types can learn from her experience.

“Really, you have to acknowledge that the condition you are treating is causing the pigmentation change, and we do see that and that we have a treatment plan in place,” she said.

Because of differences in how inflammatory skin diseases present in darker skin types, there is plenty of room for a delayed diagnosis for clinicians who do not see many of these patients, according to Dr. Heath. Follicular eczema, which is common in skin of color, often presents with pruritus but differences in the appearance of the underlying disease can threaten a delay in diagnosis.

In cases of follicular eczema with itch in darker skin, the bumps look and feel like goose bumps, which “means that the eczema is really active and inflamed,” Dr. Heath said. When the skin becomes smooth and the itch dissipates, “you know that they are under great control.”

Psoriasis is often missed in children with darker skin types based on the misperception that it is rare. Although it is true that it is less common in Blacks than Whites, it is not rare, according to Dr. Heath. In inspecting the telltale erythematous plaque–like lesions, clinicians might start to consider alternative diagnoses when they do not detect the same erythematous appearance, but the reddish tone is often concealed in darker skin.

She said that predominant involvement in the head and neck and diaper area is often more common in children of color and that nail or scalp involvement, when present, is often a clue that psoriasis is the diagnosis.

Again, because many clinicians do not think immediately of psoriasis in darker skin children with lesions in the scalp, Dr. Heath advised this is another reason to include psoriasis in the differential diagnosis.

“If you have a child that has failed multiple courses of treatment for tinea capitis and they have well-demarcated plaques, it’s time to really start to think about pediatric psoriasis,” she said.

Restoring skin tone can be the priority

Asked to comment on Dr. Heath’s advice about the importance of acknowledging pigmentary changes associated with inflammatory skin diseases in patients of color, Jenna Lester, MD, the founding director of the Skin of Color Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, called it an “often unspoken concern of patients.”

“Pigmentary changes that occur secondary to an inflammatory condition should be addressed and treated alongside the inciting condition,” she agreed.

Even if changes in skin color or skin tone are not a specific complaint of the patients, Dr. Lester also urged clinicians to raise the topic. If change in skin pigmentation is part of the clinical picture, this should be targeted in the treatment plan.

“In acne, for example, often times I find that patients are as worried about postinflammatory hyperpigmentation as they are about their acne,” she said, reiterating the advice provided by Dr. Heath.

Dr. Heath has financial relationships with Arcutis, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, and Regeneron. Dr. Lester reported no potential conflicts of interest.

NEW YORK –

Skin diseases pose a greater risk of both hyper- and hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types, but the fear and concern that this raises for permanent disfigurement is not limited to Blacks, Dr. Heath, assistant professor of pediatric dermatology at Temple University, Philadelphia, said at the Skin of Color Update 2023.

“Culturally, pigmentation changes can be huge. For people of Indian descent, for example, pigmentary changes like light spots on the skin might be an obstacle to marriage, so it can really be life changing,” she added.

In patients with darker skin tones presenting with an inflammatory skin disease, such as AD or psoriasis, Dr. Heath advised asking specifically about change in skin tone even if it is not readily apparent. In pediatric patients, it is also appropriate to include parents in this conversation.

Consider the parent’s perspective

“When you are taking care of a child or adolescent, the patient is likely to be concerned about changes in pigmentation, but it is important to remember that the adult in the room might have had their own journey with brown skin and has dealt with the burden of pigment changes,” Dr. Heath said.

For the parent, the pigmentation changes, rather than the inflammation, might be the governing issue and the reason that he or she brought the child to the clinician. Dr. Heath suggested that it is important for caregivers to explicitly recognize their concern, explain that addressing the pigmentary changes is part of the treatment plan, and to create realistic expectations about how long pigmentary changes will take to resolve.

As an example, Dr. Heath recounted a difficult case of a Black infant with disseminated hyperpigmentation and features that did not preclude pathology other than AD. Dr. Heath created a multifaceted treatment plan to address the inflammation in distinct areas of the body that included low-strength topical steroids for the face, stronger steroids for the body, and advice on scalp and skin care.

“I thought this was a great treatment plan out of the gate – I was covering all of the things on my differential list – I thought that the mom would be thinking, this doctor is amazing,” Dr. Heath said.

Pigmentary changes are a priority

However, that was not what the patient’s mother was thinking. Having failed to explicitly recognize her concern about the pigmentation changes and how the treatment would address this issue, the mother was disappointed.

“She had one question: Will my baby ever be one color? That was her main concern,” said Dr. Heath, indicating that other clinicians seeing inflammatory diseases in children with darker skin types can learn from her experience.

“Really, you have to acknowledge that the condition you are treating is causing the pigmentation change, and we do see that and that we have a treatment plan in place,” she said.

Because of differences in how inflammatory skin diseases present in darker skin types, there is plenty of room for a delayed diagnosis for clinicians who do not see many of these patients, according to Dr. Heath. Follicular eczema, which is common in skin of color, often presents with pruritus but differences in the appearance of the underlying disease can threaten a delay in diagnosis.

In cases of follicular eczema with itch in darker skin, the bumps look and feel like goose bumps, which “means that the eczema is really active and inflamed,” Dr. Heath said. When the skin becomes smooth and the itch dissipates, “you know that they are under great control.”

Psoriasis is often missed in children with darker skin types based on the misperception that it is rare. Although it is true that it is less common in Blacks than Whites, it is not rare, according to Dr. Heath. In inspecting the telltale erythematous plaque–like lesions, clinicians might start to consider alternative diagnoses when they do not detect the same erythematous appearance, but the reddish tone is often concealed in darker skin.

She said that predominant involvement in the head and neck and diaper area is often more common in children of color and that nail or scalp involvement, when present, is often a clue that psoriasis is the diagnosis.

Again, because many clinicians do not think immediately of psoriasis in darker skin children with lesions in the scalp, Dr. Heath advised this is another reason to include psoriasis in the differential diagnosis.

“If you have a child that has failed multiple courses of treatment for tinea capitis and they have well-demarcated plaques, it’s time to really start to think about pediatric psoriasis,” she said.

Restoring skin tone can be the priority

Asked to comment on Dr. Heath’s advice about the importance of acknowledging pigmentary changes associated with inflammatory skin diseases in patients of color, Jenna Lester, MD, the founding director of the Skin of Color Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, called it an “often unspoken concern of patients.”

“Pigmentary changes that occur secondary to an inflammatory condition should be addressed and treated alongside the inciting condition,” she agreed.

Even if changes in skin color or skin tone are not a specific complaint of the patients, Dr. Lester also urged clinicians to raise the topic. If change in skin pigmentation is part of the clinical picture, this should be targeted in the treatment plan.

“In acne, for example, often times I find that patients are as worried about postinflammatory hyperpigmentation as they are about their acne,” she said, reiterating the advice provided by Dr. Heath.

Dr. Heath has financial relationships with Arcutis, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, and Regeneron. Dr. Lester reported no potential conflicts of interest.

NEW YORK –

Skin diseases pose a greater risk of both hyper- and hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types, but the fear and concern that this raises for permanent disfigurement is not limited to Blacks, Dr. Heath, assistant professor of pediatric dermatology at Temple University, Philadelphia, said at the Skin of Color Update 2023.

“Culturally, pigmentation changes can be huge. For people of Indian descent, for example, pigmentary changes like light spots on the skin might be an obstacle to marriage, so it can really be life changing,” she added.

In patients with darker skin tones presenting with an inflammatory skin disease, such as AD or psoriasis, Dr. Heath advised asking specifically about change in skin tone even if it is not readily apparent. In pediatric patients, it is also appropriate to include parents in this conversation.

Consider the parent’s perspective

“When you are taking care of a child or adolescent, the patient is likely to be concerned about changes in pigmentation, but it is important to remember that the adult in the room might have had their own journey with brown skin and has dealt with the burden of pigment changes,” Dr. Heath said.

For the parent, the pigmentation changes, rather than the inflammation, might be the governing issue and the reason that he or she brought the child to the clinician. Dr. Heath suggested that it is important for caregivers to explicitly recognize their concern, explain that addressing the pigmentary changes is part of the treatment plan, and to create realistic expectations about how long pigmentary changes will take to resolve.

As an example, Dr. Heath recounted a difficult case of a Black infant with disseminated hyperpigmentation and features that did not preclude pathology other than AD. Dr. Heath created a multifaceted treatment plan to address the inflammation in distinct areas of the body that included low-strength topical steroids for the face, stronger steroids for the body, and advice on scalp and skin care.

“I thought this was a great treatment plan out of the gate – I was covering all of the things on my differential list – I thought that the mom would be thinking, this doctor is amazing,” Dr. Heath said.

Pigmentary changes are a priority

However, that was not what the patient’s mother was thinking. Having failed to explicitly recognize her concern about the pigmentation changes and how the treatment would address this issue, the mother was disappointed.

“She had one question: Will my baby ever be one color? That was her main concern,” said Dr. Heath, indicating that other clinicians seeing inflammatory diseases in children with darker skin types can learn from her experience.

“Really, you have to acknowledge that the condition you are treating is causing the pigmentation change, and we do see that and that we have a treatment plan in place,” she said.

Because of differences in how inflammatory skin diseases present in darker skin types, there is plenty of room for a delayed diagnosis for clinicians who do not see many of these patients, according to Dr. Heath. Follicular eczema, which is common in skin of color, often presents with pruritus but differences in the appearance of the underlying disease can threaten a delay in diagnosis.

In cases of follicular eczema with itch in darker skin, the bumps look and feel like goose bumps, which “means that the eczema is really active and inflamed,” Dr. Heath said. When the skin becomes smooth and the itch dissipates, “you know that they are under great control.”

Psoriasis is often missed in children with darker skin types based on the misperception that it is rare. Although it is true that it is less common in Blacks than Whites, it is not rare, according to Dr. Heath. In inspecting the telltale erythematous plaque–like lesions, clinicians might start to consider alternative diagnoses when they do not detect the same erythematous appearance, but the reddish tone is often concealed in darker skin.

She said that predominant involvement in the head and neck and diaper area is often more common in children of color and that nail or scalp involvement, when present, is often a clue that psoriasis is the diagnosis.

Again, because many clinicians do not think immediately of psoriasis in darker skin children with lesions in the scalp, Dr. Heath advised this is another reason to include psoriasis in the differential diagnosis.

“If you have a child that has failed multiple courses of treatment for tinea capitis and they have well-demarcated plaques, it’s time to really start to think about pediatric psoriasis,” she said.

Restoring skin tone can be the priority

Asked to comment on Dr. Heath’s advice about the importance of acknowledging pigmentary changes associated with inflammatory skin diseases in patients of color, Jenna Lester, MD, the founding director of the Skin of Color Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, called it an “often unspoken concern of patients.”

“Pigmentary changes that occur secondary to an inflammatory condition should be addressed and treated alongside the inciting condition,” she agreed.

Even if changes in skin color or skin tone are not a specific complaint of the patients, Dr. Lester also urged clinicians to raise the topic. If change in skin pigmentation is part of the clinical picture, this should be targeted in the treatment plan.

“In acne, for example, often times I find that patients are as worried about postinflammatory hyperpigmentation as they are about their acne,” she said, reiterating the advice provided by Dr. Heath.

Dr. Heath has financial relationships with Arcutis, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, and Regeneron. Dr. Lester reported no potential conflicts of interest.

AT SOC 2023

Review finds no CV or VTE risk signal with use of JAK inhibitors for skin indications

, results from a systematic literature review, and meta-analysis showed.

“There remains a knowledge gap regarding the risk of JAK inhibitor use and VTE and/or MACE in the dermatologic population,” researchers led by Michael S. Garshick, MD, a cardiologist at New York University Langone Health, wrote in their study, which was published online in JAMA Dermatology . “Pooled safety studies suggest that the risk of MACE and VTE may be lower in patients treated with JAK inhibitors for a dermatologic indication than the risk observed in the ORAL Surveillance study, which may be related to the younger age and better health status of those enrolled in trials for dermatologic indications.” The results of that study, which included patients with rheumatoid arthritis only, resulted in the addition of a boxed warning in the labels for topical and oral JAK inhibitors regarding the increased risk of MACE, VTE, serious infections, malignancies, and death .

For the review – thought to be the first to specifically evaluate these risks for dermatologic indications – the researchers searched PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception through April 1, 2023, for phase 3 dermatology randomized clinical trials (RCTs) to evaluate the risk of MACE, VTE, and all-cause mortality with JAK inhibitors, compared with placebo or an active comparator in the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory skin diseases. They followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and used a random-effects model and the DerSimonian-Laird method to calculate adverse events with odds ratios.

The database search yielded 35 RCTs with a total of 20,651 patients. Their mean age was 38.5 years, 54% were male, and the mean follow-up time was 4.9 months. Of the 35 trials, most (21) involved patients with atopic dermatitis, followed by psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis (9 trials), alopecia areata (3 trials) and vitiligo (2 trials).

The researchers found no significant difference between JAK inhibitors and placebo/active comparator in composite MACE and all-cause mortality (odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.44-1.57) or in VTE (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.26-1.04).

In a secondary analysis, which included additional psoriatic arthritis RCTs, no significant differences between the treatment and placebo/active comparator groups were observed. Similarly, subgroup analyses of oral versus topical JAK inhibitors and a sensitivity analysis that excluded pediatric trials showed no significant differences between patients exposed to JAK inhibitors and those not exposed.

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the review, including the lack of access to patient-level data, the fact that most trials only included short-term follow-up, and that the findings have limited generalizability to an older patient population. “It remains unclear if the cardiovascular risks of JAK inhibitors are primarily due to patient level cardiovascular risk factors or are drug mediated,” they concluded. “Dermatologists should carefully select patients and assess baseline cardiovascular risk factors when considering JAK therapy. Cardiovascular risk assessment should continue for the duration of treatment.”

Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, assistant professor of dermatology and director of the center for eczema and itch at Northwestern University, Chicago, who was asked to comment on the study results, characterized the findings as reassuring to dermatologists who may be reluctant to initiate therapy with JAK inhibitors based on concerns about safety signals for MACE, VTE, and all-cause mortality.

“These data systematically show that across medications and across conditions, there doesn’t appear to be an increased signal for these events during the short-term, placebo-controlled period which generally spans a few months in most studies,” he told this news organization. The findings, he added, “align well with our clinical experience to date for JAK inhibitor use in inflammatory skin disease. Short-term safety, particularly in relation to boxed warning events such MACE, VTE, and all-cause mortality, have generally been favorable with real-world use. It’s good to have a rigorous statistical analysis to refer to when setting patient expectations.”

However, he noted that these data only examined short-term safety during the placebo or active comparator-controlled periods. “Considering that events like MACE or VTE may take many months or years to manifest, continued long-term data generation is needed to fully answer the question of risk,” he said.

Dr. Garshick disclosed that he received grants from Pfizer and personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Several other coauthors reported having advisory board roles and/or having received funding or support from several pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Chovatiya disclosed that he is a consultant to, a speaker for, investigator, and/or a member of the advisory board for several pharmaceutical companies, including those that develop JAK inhibitors.

, results from a systematic literature review, and meta-analysis showed.

“There remains a knowledge gap regarding the risk of JAK inhibitor use and VTE and/or MACE in the dermatologic population,” researchers led by Michael S. Garshick, MD, a cardiologist at New York University Langone Health, wrote in their study, which was published online in JAMA Dermatology . “Pooled safety studies suggest that the risk of MACE and VTE may be lower in patients treated with JAK inhibitors for a dermatologic indication than the risk observed in the ORAL Surveillance study, which may be related to the younger age and better health status of those enrolled in trials for dermatologic indications.” The results of that study, which included patients with rheumatoid arthritis only, resulted in the addition of a boxed warning in the labels for topical and oral JAK inhibitors regarding the increased risk of MACE, VTE, serious infections, malignancies, and death .

For the review – thought to be the first to specifically evaluate these risks for dermatologic indications – the researchers searched PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception through April 1, 2023, for phase 3 dermatology randomized clinical trials (RCTs) to evaluate the risk of MACE, VTE, and all-cause mortality with JAK inhibitors, compared with placebo or an active comparator in the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory skin diseases. They followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and used a random-effects model and the DerSimonian-Laird method to calculate adverse events with odds ratios.

The database search yielded 35 RCTs with a total of 20,651 patients. Their mean age was 38.5 years, 54% were male, and the mean follow-up time was 4.9 months. Of the 35 trials, most (21) involved patients with atopic dermatitis, followed by psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis (9 trials), alopecia areata (3 trials) and vitiligo (2 trials).

The researchers found no significant difference between JAK inhibitors and placebo/active comparator in composite MACE and all-cause mortality (odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.44-1.57) or in VTE (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.26-1.04).

In a secondary analysis, which included additional psoriatic arthritis RCTs, no significant differences between the treatment and placebo/active comparator groups were observed. Similarly, subgroup analyses of oral versus topical JAK inhibitors and a sensitivity analysis that excluded pediatric trials showed no significant differences between patients exposed to JAK inhibitors and those not exposed.

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the review, including the lack of access to patient-level data, the fact that most trials only included short-term follow-up, and that the findings have limited generalizability to an older patient population. “It remains unclear if the cardiovascular risks of JAK inhibitors are primarily due to patient level cardiovascular risk factors or are drug mediated,” they concluded. “Dermatologists should carefully select patients and assess baseline cardiovascular risk factors when considering JAK therapy. Cardiovascular risk assessment should continue for the duration of treatment.”

Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, assistant professor of dermatology and director of the center for eczema and itch at Northwestern University, Chicago, who was asked to comment on the study results, characterized the findings as reassuring to dermatologists who may be reluctant to initiate therapy with JAK inhibitors based on concerns about safety signals for MACE, VTE, and all-cause mortality.

“These data systematically show that across medications and across conditions, there doesn’t appear to be an increased signal for these events during the short-term, placebo-controlled period which generally spans a few months in most studies,” he told this news organization. The findings, he added, “align well with our clinical experience to date for JAK inhibitor use in inflammatory skin disease. Short-term safety, particularly in relation to boxed warning events such MACE, VTE, and all-cause mortality, have generally been favorable with real-world use. It’s good to have a rigorous statistical analysis to refer to when setting patient expectations.”

However, he noted that these data only examined short-term safety during the placebo or active comparator-controlled periods. “Considering that events like MACE or VTE may take many months or years to manifest, continued long-term data generation is needed to fully answer the question of risk,” he said.

Dr. Garshick disclosed that he received grants from Pfizer and personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Several other coauthors reported having advisory board roles and/or having received funding or support from several pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Chovatiya disclosed that he is a consultant to, a speaker for, investigator, and/or a member of the advisory board for several pharmaceutical companies, including those that develop JAK inhibitors.

, results from a systematic literature review, and meta-analysis showed.

“There remains a knowledge gap regarding the risk of JAK inhibitor use and VTE and/or MACE in the dermatologic population,” researchers led by Michael S. Garshick, MD, a cardiologist at New York University Langone Health, wrote in their study, which was published online in JAMA Dermatology . “Pooled safety studies suggest that the risk of MACE and VTE may be lower in patients treated with JAK inhibitors for a dermatologic indication than the risk observed in the ORAL Surveillance study, which may be related to the younger age and better health status of those enrolled in trials for dermatologic indications.” The results of that study, which included patients with rheumatoid arthritis only, resulted in the addition of a boxed warning in the labels for topical and oral JAK inhibitors regarding the increased risk of MACE, VTE, serious infections, malignancies, and death .

For the review – thought to be the first to specifically evaluate these risks for dermatologic indications – the researchers searched PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception through April 1, 2023, for phase 3 dermatology randomized clinical trials (RCTs) to evaluate the risk of MACE, VTE, and all-cause mortality with JAK inhibitors, compared with placebo or an active comparator in the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory skin diseases. They followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and used a random-effects model and the DerSimonian-Laird method to calculate adverse events with odds ratios.

The database search yielded 35 RCTs with a total of 20,651 patients. Their mean age was 38.5 years, 54% were male, and the mean follow-up time was 4.9 months. Of the 35 trials, most (21) involved patients with atopic dermatitis, followed by psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis (9 trials), alopecia areata (3 trials) and vitiligo (2 trials).

The researchers found no significant difference between JAK inhibitors and placebo/active comparator in composite MACE and all-cause mortality (odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.44-1.57) or in VTE (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.26-1.04).

In a secondary analysis, which included additional psoriatic arthritis RCTs, no significant differences between the treatment and placebo/active comparator groups were observed. Similarly, subgroup analyses of oral versus topical JAK inhibitors and a sensitivity analysis that excluded pediatric trials showed no significant differences between patients exposed to JAK inhibitors and those not exposed.

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the review, including the lack of access to patient-level data, the fact that most trials only included short-term follow-up, and that the findings have limited generalizability to an older patient population. “It remains unclear if the cardiovascular risks of JAK inhibitors are primarily due to patient level cardiovascular risk factors or are drug mediated,” they concluded. “Dermatologists should carefully select patients and assess baseline cardiovascular risk factors when considering JAK therapy. Cardiovascular risk assessment should continue for the duration of treatment.”

Raj Chovatiya, MD, PhD, assistant professor of dermatology and director of the center for eczema and itch at Northwestern University, Chicago, who was asked to comment on the study results, characterized the findings as reassuring to dermatologists who may be reluctant to initiate therapy with JAK inhibitors based on concerns about safety signals for MACE, VTE, and all-cause mortality.

“These data systematically show that across medications and across conditions, there doesn’t appear to be an increased signal for these events during the short-term, placebo-controlled period which generally spans a few months in most studies,” he told this news organization. The findings, he added, “align well with our clinical experience to date for JAK inhibitor use in inflammatory skin disease. Short-term safety, particularly in relation to boxed warning events such MACE, VTE, and all-cause mortality, have generally been favorable with real-world use. It’s good to have a rigorous statistical analysis to refer to when setting patient expectations.”

However, he noted that these data only examined short-term safety during the placebo or active comparator-controlled periods. “Considering that events like MACE or VTE may take many months or years to manifest, continued long-term data generation is needed to fully answer the question of risk,” he said.

Dr. Garshick disclosed that he received grants from Pfizer and personal fees from Bristol Myers Squibb during the conduct of the study and personal fees from Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Several other coauthors reported having advisory board roles and/or having received funding or support from several pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Chovatiya disclosed that he is a consultant to, a speaker for, investigator, and/or a member of the advisory board for several pharmaceutical companies, including those that develop JAK inhibitors.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Cysteamine and melasma

Most subjects covered in this column are botanical ingredients used for multiple conditions in topical skin care. The focus this month, though, is a natural agent garnering attention primarily for one indication. Present in many mammals and in various cells in the human body (and particularly highly concentrated in human milk), cysteamine is a stable aminothiol that acts as an antioxidant as a result of the degradation of coenzyme A and is known to play a protective function.1 Melasma, an acquired recurrent, chronic hyperpigmentary disorder, continues to be a treatment challenge and is often psychologically troublesome for those affected, approximately 90% of whom are women.2 Individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV and V who reside in regions where UV exposure is likely are particularly prominent among those with melasma.2 While triple combination therapy (also known as Kligman’s formula) continues to be the modern gold standard of care for melasma (over the last 30 years),3 cysteamine, a nonmelanocytotoxic molecule, is considered viable for long-term use and safer than the long-time skin-lightening gold standard over several decades, hydroquinone (HQ), which is associated with safety concerns.4.

Recent history and the 2015 study

Prior to 2015, the quick oxidation and malodorous nature of cysteamine rendered it unsuitable for use as a topical agent. However, stabilization efforts resulted in a product that first began to show efficacy that year.5

Mansouri et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy of topical cysteamine 5% to treat epidermal melasma in 2015. Over 4 months, 50 volunteers (25 in each group) applied either cysteamine cream or placebo on lesions once nightly. The mean differences at baseline between pigmented and normal skin were 75.2 ± 37 in the cysteamine group and 68.9 ± 31 in the placebo group. Statistically significant differences between the groups were identified at the 2- and 4-month points. At 2 months, the mean differences were 39.7 ± 16.6 in the cysteamine group and 63.8 ± 28.6 in the placebo group; at 4 months, the respective differences were 26.2 ± 16 and 60.7 ± 27.3. Melasma area severity index (MASI) scores were significantly lower in the cysteamine group compared with the placebo group at the end of the study, and investigator global assessment scores and patient questionnaire results revealed substantial comparative efficacy of cysteamine cream.6 Topical cysteamine has also demonstrated notable efficacy in treating senile lentigines, which typically do not respond to topical depigmenting products.5

Farshi et al. used Dermacatch as a novel measurement tool to ascertain the efficacy of cysteamine cream for treating epidermal melasma in a 2018 report of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with 40 patients. During the 4-month trial, cysteamine cream or placebo was applied nightly before sleep. Investigators measured treatment efficacy through Dermacatch, and Mexameter skin colorimetry, MASI scores, investigator global assessments, and patient questionnaires at baseline, 2 months, and 4 months. Through all measurement methods, cysteamine was found to reduce melanin content of melasma lesions, with Dermacatch performing reliably and comparably to Mexameter.7 Since then, cysteamine has been compared to several first-line melasma therapies.

Reviews

A 2019 systematic review by Austin et al. of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on topical treatments for melasma identified 35 original RCTs evaluating a wide range of approximately 20 agents. They identified cysteamine, triple combination therapy, and tranexamic acid as the products netting the most robust recommendations. The researchers characterized cysteamine as conferring strong efficacy and reported anticancer activity while triple combination therapy poses the potential risk of ochronosis and tranexamic acid may present the risk for thrombosis. They concluded that more research is necessary, though, to establish the proper concentration and optimal formulation of cysteamine as a frontline therapy.8

More reviews have since been published to further clarify where cysteamine stands among the optimal treatments for melasma. In a May 2022 systematic PubMed review of topical agents used to treat melasma, González-Molina et al. identified 80 papers meeting inclusion criteria (double or single blinded, prospective, controlled or RCTs, reviews of literature, and meta-analysis studies), with tranexamic acid and cysteamine among the novel well-tolerated agents. Cysteamine was not associated with any severe adverse effects and is recommended as an adjuvant and maintenance therapy.3

A September 2022 review by Niazi et al. found that while the signaling mechanisms through which cysteamine suppresses melasma are not well understood, the topical application of cysteamine cream is seen as safe and effective alone or in combination with other products to treat melasma.2

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported by Gomes dos Santos-Neto et al. at the end of 2022 considered the efficacy of depigmenting formulations containing 5% cysteamine for treating melasma. The meta-analysis covered six studies, with 120 melasma patients treated. The conclusion was that 5% cysteamine was effective with adverse effects unlikely.9

Cysteamine vs. hydroquinone

In 2020, Lima et al. reported the results of a quasi-randomized, multicenter, evaluator-blinded comparative study of topical 0.56% cysteamine and 4% HQ in 40 women with facial melasma. (Note that this study originally claimed a 5% cysteamine concentration, but a letter to the editor of the International Journal of Dermatology in 2020 disputed this and proved it was 0.56%) For 120 days, volunteers applied either 0.56% cysteamine or 4% HQ nightly. Tinted sunscreen (SPF 50; PPD 19) use was required for all participants. There were no differences in colorimetric evaluations between the groups, both of which showed progressive depigmenting, or in photographic assessments. The HQ group demonstrated greater mean decreases in modified melasma area severity index (mMASI) scores (41% for HQ and 24% for cysteamine at 60 days; 53% for HQ and 38% for cysteamine at 120 days). The investigators observed that while cysteamine was safe, well tolerated, and effective, it was outperformed by HQ in terms of mMASI and melasma quality of life (MELASQoL) scores.10

Early the next year, results of a randomized, double-blind, single-center study in 20 women, conducted by Nguyen et al. comparing the efficacy of cysteamine cream with HQ for melasma treatment were published. Participants were given either treatment over 16 weeks. Ultimately, five volunteers in the cysteamine group and nine in the HQ group completed the study. There was no statistically significant difference in mMASI scores between the groups. In this notably small study, HQ was tolerated better. The researchers concluded that their findings supported the argument of comparable efficacy between cysteamine and HQ, with further studies needed to establish whether cysteamine would be an appropriate alternative to HQ.11 Notably, HQ was banned by the Food and Drug Administration in 2020 in over-the-counter products.

Cysteamine vs. Kligman’s formula

Early in 2021, Karrabi et al. published the results of a randomized, double-blind clinical trial of 50 subjects with epidermal melasma to compare cysteamine 5% with Modified Kligman’s formula. Over 4 months, participants applied once daily either cysteamine cream 5% (15 minutes exposure) or the Modified Kligman’s formula (4% hydroquinone, 0.05% retinoic acid and 0.1% betamethasone) for whole night exposure. At 2 and 4 months, a statistically significant difference in mMASI score was noted, with the percentage decline in mMASI score nearly 9% higher in the cysteamine group. The investigators concluded that cysteamine 5% demonstrated greater efficacy than the Modified Kligman’s formula and was also better tolerated.12

Cysteamine vs. tranexamic acid

Later that year, Karrabi et al. published the results of a single-blind, randomized clinical trial assessing the efficacy of tranexamic acid mesotherapy compared with cysteamine 5% cream in 54 melasma patients. For 4 consecutive months, the cysteamine 5% cream group applied the cream on lesions 30 minutes before going to sleep. Every 4 weeks until 2 months, a physician performed tranexamic acid mesotherapy (0.05 mL; 4 mg/mL) on individuals in the tranexamic acid group. The researchers concluded, after measurements using both a Dermacatch device and the mMASI, that neither treatment was significantly better than the other but fewer complications were observed in the cysteamine group.13

Safety

In 2022, Sepaskhah et al. assessed the effects of a cysteamine 5% cream and compared it with HQ 4%/ascorbic acid 3% cream for epidermal melasma in a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Sixty-five of 80 patients completed the study. The difference in mMASI scores after 4 months was not significant between the groups nor was the improvement in quality of life, but the melanin index was significantly lower in the HQ/ascorbic acid group compared with the less substantial reduction for the cysteamine group. Nevertheless, the researchers concluded that cysteamine is a safe and suitable substitute for HQ/ascorbic acid.4

Conclusion

In the last decade, cysteamine has been established as a potent depigmenting agent. Its suitability and desirability as a top consideration for melasma treatment also appears to be compelling. More RCTs comparing cysteamine and other topline therapies are warranted, but current evidence shows that cysteamine is an effective and safe therapy for melasma.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in office and as an ecommerce solution. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Konar MC et al. J Trop Pediatr. 2020 Apr 1;66(2):129-35.

2. Niazi S et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Sep;21(9):3867-75.

3. González-Molina V et al. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022 May;15(5):19-28.

4. Sepaskhah M et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jul;21(7):2871-8.

5. Desai S et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021 Dec 1;20(12):1276-9.

6. Mansouri P et al. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Jul;173(1):209-17.

7. Farshi S et al. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018 Mar;29(2):182-9.

8. Austin E et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Nov 1;18(11):S1545961619P1156X.

9. Gomes dos Santos-Neto A et al. Dermatol Ther. 2022 Dec;35(12):e15961.

10. Lima PB et al. Int J Dermatol. 2020 Dec;59(12):1531-6.

11. Nguyen J et al. Australas J Dermatol. 2021 Feb;62(1):e41-e46.

12. Karrabi M et al. Skin Res Technol. 2021 Jan;27(1):24-31.

13. Karrabi M et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021 Sep;313(7):539-47.

Most subjects covered in this column are botanical ingredients used for multiple conditions in topical skin care. The focus this month, though, is a natural agent garnering attention primarily for one indication. Present in many mammals and in various cells in the human body (and particularly highly concentrated in human milk), cysteamine is a stable aminothiol that acts as an antioxidant as a result of the degradation of coenzyme A and is known to play a protective function.1 Melasma, an acquired recurrent, chronic hyperpigmentary disorder, continues to be a treatment challenge and is often psychologically troublesome for those affected, approximately 90% of whom are women.2 Individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV and V who reside in regions where UV exposure is likely are particularly prominent among those with melasma.2 While triple combination therapy (also known as Kligman’s formula) continues to be the modern gold standard of care for melasma (over the last 30 years),3 cysteamine, a nonmelanocytotoxic molecule, is considered viable for long-term use and safer than the long-time skin-lightening gold standard over several decades, hydroquinone (HQ), which is associated with safety concerns.4.

Recent history and the 2015 study

Prior to 2015, the quick oxidation and malodorous nature of cysteamine rendered it unsuitable for use as a topical agent. However, stabilization efforts resulted in a product that first began to show efficacy that year.5

Mansouri et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy of topical cysteamine 5% to treat epidermal melasma in 2015. Over 4 months, 50 volunteers (25 in each group) applied either cysteamine cream or placebo on lesions once nightly. The mean differences at baseline between pigmented and normal skin were 75.2 ± 37 in the cysteamine group and 68.9 ± 31 in the placebo group. Statistically significant differences between the groups were identified at the 2- and 4-month points. At 2 months, the mean differences were 39.7 ± 16.6 in the cysteamine group and 63.8 ± 28.6 in the placebo group; at 4 months, the respective differences were 26.2 ± 16 and 60.7 ± 27.3. Melasma area severity index (MASI) scores were significantly lower in the cysteamine group compared with the placebo group at the end of the study, and investigator global assessment scores and patient questionnaire results revealed substantial comparative efficacy of cysteamine cream.6 Topical cysteamine has also demonstrated notable efficacy in treating senile lentigines, which typically do not respond to topical depigmenting products.5

Farshi et al. used Dermacatch as a novel measurement tool to ascertain the efficacy of cysteamine cream for treating epidermal melasma in a 2018 report of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with 40 patients. During the 4-month trial, cysteamine cream or placebo was applied nightly before sleep. Investigators measured treatment efficacy through Dermacatch, and Mexameter skin colorimetry, MASI scores, investigator global assessments, and patient questionnaires at baseline, 2 months, and 4 months. Through all measurement methods, cysteamine was found to reduce melanin content of melasma lesions, with Dermacatch performing reliably and comparably to Mexameter.7 Since then, cysteamine has been compared to several first-line melasma therapies.

Reviews

A 2019 systematic review by Austin et al. of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on topical treatments for melasma identified 35 original RCTs evaluating a wide range of approximately 20 agents. They identified cysteamine, triple combination therapy, and tranexamic acid as the products netting the most robust recommendations. The researchers characterized cysteamine as conferring strong efficacy and reported anticancer activity while triple combination therapy poses the potential risk of ochronosis and tranexamic acid may present the risk for thrombosis. They concluded that more research is necessary, though, to establish the proper concentration and optimal formulation of cysteamine as a frontline therapy.8

More reviews have since been published to further clarify where cysteamine stands among the optimal treatments for melasma. In a May 2022 systematic PubMed review of topical agents used to treat melasma, González-Molina et al. identified 80 papers meeting inclusion criteria (double or single blinded, prospective, controlled or RCTs, reviews of literature, and meta-analysis studies), with tranexamic acid and cysteamine among the novel well-tolerated agents. Cysteamine was not associated with any severe adverse effects and is recommended as an adjuvant and maintenance therapy.3

A September 2022 review by Niazi et al. found that while the signaling mechanisms through which cysteamine suppresses melasma are not well understood, the topical application of cysteamine cream is seen as safe and effective alone or in combination with other products to treat melasma.2

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported by Gomes dos Santos-Neto et al. at the end of 2022 considered the efficacy of depigmenting formulations containing 5% cysteamine for treating melasma. The meta-analysis covered six studies, with 120 melasma patients treated. The conclusion was that 5% cysteamine was effective with adverse effects unlikely.9

Cysteamine vs. hydroquinone

In 2020, Lima et al. reported the results of a quasi-randomized, multicenter, evaluator-blinded comparative study of topical 0.56% cysteamine and 4% HQ in 40 women with facial melasma. (Note that this study originally claimed a 5% cysteamine concentration, but a letter to the editor of the International Journal of Dermatology in 2020 disputed this and proved it was 0.56%) For 120 days, volunteers applied either 0.56% cysteamine or 4% HQ nightly. Tinted sunscreen (SPF 50; PPD 19) use was required for all participants. There were no differences in colorimetric evaluations between the groups, both of which showed progressive depigmenting, or in photographic assessments. The HQ group demonstrated greater mean decreases in modified melasma area severity index (mMASI) scores (41% for HQ and 24% for cysteamine at 60 days; 53% for HQ and 38% for cysteamine at 120 days). The investigators observed that while cysteamine was safe, well tolerated, and effective, it was outperformed by HQ in terms of mMASI and melasma quality of life (MELASQoL) scores.10

Early the next year, results of a randomized, double-blind, single-center study in 20 women, conducted by Nguyen et al. comparing the efficacy of cysteamine cream with HQ for melasma treatment were published. Participants were given either treatment over 16 weeks. Ultimately, five volunteers in the cysteamine group and nine in the HQ group completed the study. There was no statistically significant difference in mMASI scores between the groups. In this notably small study, HQ was tolerated better. The researchers concluded that their findings supported the argument of comparable efficacy between cysteamine and HQ, with further studies needed to establish whether cysteamine would be an appropriate alternative to HQ.11 Notably, HQ was banned by the Food and Drug Administration in 2020 in over-the-counter products.

Cysteamine vs. Kligman’s formula

Early in 2021, Karrabi et al. published the results of a randomized, double-blind clinical trial of 50 subjects with epidermal melasma to compare cysteamine 5% with Modified Kligman’s formula. Over 4 months, participants applied once daily either cysteamine cream 5% (15 minutes exposure) or the Modified Kligman’s formula (4% hydroquinone, 0.05% retinoic acid and 0.1% betamethasone) for whole night exposure. At 2 and 4 months, a statistically significant difference in mMASI score was noted, with the percentage decline in mMASI score nearly 9% higher in the cysteamine group. The investigators concluded that cysteamine 5% demonstrated greater efficacy than the Modified Kligman’s formula and was also better tolerated.12

Cysteamine vs. tranexamic acid

Later that year, Karrabi et al. published the results of a single-blind, randomized clinical trial assessing the efficacy of tranexamic acid mesotherapy compared with cysteamine 5% cream in 54 melasma patients. For 4 consecutive months, the cysteamine 5% cream group applied the cream on lesions 30 minutes before going to sleep. Every 4 weeks until 2 months, a physician performed tranexamic acid mesotherapy (0.05 mL; 4 mg/mL) on individuals in the tranexamic acid group. The researchers concluded, after measurements using both a Dermacatch device and the mMASI, that neither treatment was significantly better than the other but fewer complications were observed in the cysteamine group.13

Safety

In 2022, Sepaskhah et al. assessed the effects of a cysteamine 5% cream and compared it with HQ 4%/ascorbic acid 3% cream for epidermal melasma in a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Sixty-five of 80 patients completed the study. The difference in mMASI scores after 4 months was not significant between the groups nor was the improvement in quality of life, but the melanin index was significantly lower in the HQ/ascorbic acid group compared with the less substantial reduction for the cysteamine group. Nevertheless, the researchers concluded that cysteamine is a safe and suitable substitute for HQ/ascorbic acid.4

Conclusion

In the last decade, cysteamine has been established as a potent depigmenting agent. Its suitability and desirability as a top consideration for melasma treatment also appears to be compelling. More RCTs comparing cysteamine and other topline therapies are warranted, but current evidence shows that cysteamine is an effective and safe therapy for melasma.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in office and as an ecommerce solution. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Konar MC et al. J Trop Pediatr. 2020 Apr 1;66(2):129-35.

2. Niazi S et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Sep;21(9):3867-75.

3. González-Molina V et al. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022 May;15(5):19-28.

4. Sepaskhah M et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jul;21(7):2871-8.

5. Desai S et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021 Dec 1;20(12):1276-9.

6. Mansouri P et al. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Jul;173(1):209-17.

7. Farshi S et al. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018 Mar;29(2):182-9.

8. Austin E et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Nov 1;18(11):S1545961619P1156X.

9. Gomes dos Santos-Neto A et al. Dermatol Ther. 2022 Dec;35(12):e15961.

10. Lima PB et al. Int J Dermatol. 2020 Dec;59(12):1531-6.

11. Nguyen J et al. Australas J Dermatol. 2021 Feb;62(1):e41-e46.

12. Karrabi M et al. Skin Res Technol. 2021 Jan;27(1):24-31.

13. Karrabi M et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021 Sep;313(7):539-47.

Most subjects covered in this column are botanical ingredients used for multiple conditions in topical skin care. The focus this month, though, is a natural agent garnering attention primarily for one indication. Present in many mammals and in various cells in the human body (and particularly highly concentrated in human milk), cysteamine is a stable aminothiol that acts as an antioxidant as a result of the degradation of coenzyme A and is known to play a protective function.1 Melasma, an acquired recurrent, chronic hyperpigmentary disorder, continues to be a treatment challenge and is often psychologically troublesome for those affected, approximately 90% of whom are women.2 Individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV and V who reside in regions where UV exposure is likely are particularly prominent among those with melasma.2 While triple combination therapy (also known as Kligman’s formula) continues to be the modern gold standard of care for melasma (over the last 30 years),3 cysteamine, a nonmelanocytotoxic molecule, is considered viable for long-term use and safer than the long-time skin-lightening gold standard over several decades, hydroquinone (HQ), which is associated with safety concerns.4.

Recent history and the 2015 study

Prior to 2015, the quick oxidation and malodorous nature of cysteamine rendered it unsuitable for use as a topical agent. However, stabilization efforts resulted in a product that first began to show efficacy that year.5

Mansouri et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy of topical cysteamine 5% to treat epidermal melasma in 2015. Over 4 months, 50 volunteers (25 in each group) applied either cysteamine cream or placebo on lesions once nightly. The mean differences at baseline between pigmented and normal skin were 75.2 ± 37 in the cysteamine group and 68.9 ± 31 in the placebo group. Statistically significant differences between the groups were identified at the 2- and 4-month points. At 2 months, the mean differences were 39.7 ± 16.6 in the cysteamine group and 63.8 ± 28.6 in the placebo group; at 4 months, the respective differences were 26.2 ± 16 and 60.7 ± 27.3. Melasma area severity index (MASI) scores were significantly lower in the cysteamine group compared with the placebo group at the end of the study, and investigator global assessment scores and patient questionnaire results revealed substantial comparative efficacy of cysteamine cream.6 Topical cysteamine has also demonstrated notable efficacy in treating senile lentigines, which typically do not respond to topical depigmenting products.5

Farshi et al. used Dermacatch as a novel measurement tool to ascertain the efficacy of cysteamine cream for treating epidermal melasma in a 2018 report of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with 40 patients. During the 4-month trial, cysteamine cream or placebo was applied nightly before sleep. Investigators measured treatment efficacy through Dermacatch, and Mexameter skin colorimetry, MASI scores, investigator global assessments, and patient questionnaires at baseline, 2 months, and 4 months. Through all measurement methods, cysteamine was found to reduce melanin content of melasma lesions, with Dermacatch performing reliably and comparably to Mexameter.7 Since then, cysteamine has been compared to several first-line melasma therapies.

Reviews

A 2019 systematic review by Austin et al. of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on topical treatments for melasma identified 35 original RCTs evaluating a wide range of approximately 20 agents. They identified cysteamine, triple combination therapy, and tranexamic acid as the products netting the most robust recommendations. The researchers characterized cysteamine as conferring strong efficacy and reported anticancer activity while triple combination therapy poses the potential risk of ochronosis and tranexamic acid may present the risk for thrombosis. They concluded that more research is necessary, though, to establish the proper concentration and optimal formulation of cysteamine as a frontline therapy.8

More reviews have since been published to further clarify where cysteamine stands among the optimal treatments for melasma. In a May 2022 systematic PubMed review of topical agents used to treat melasma, González-Molina et al. identified 80 papers meeting inclusion criteria (double or single blinded, prospective, controlled or RCTs, reviews of literature, and meta-analysis studies), with tranexamic acid and cysteamine among the novel well-tolerated agents. Cysteamine was not associated with any severe adverse effects and is recommended as an adjuvant and maintenance therapy.3

A September 2022 review by Niazi et al. found that while the signaling mechanisms through which cysteamine suppresses melasma are not well understood, the topical application of cysteamine cream is seen as safe and effective alone or in combination with other products to treat melasma.2

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported by Gomes dos Santos-Neto et al. at the end of 2022 considered the efficacy of depigmenting formulations containing 5% cysteamine for treating melasma. The meta-analysis covered six studies, with 120 melasma patients treated. The conclusion was that 5% cysteamine was effective with adverse effects unlikely.9

Cysteamine vs. hydroquinone

In 2020, Lima et al. reported the results of a quasi-randomized, multicenter, evaluator-blinded comparative study of topical 0.56% cysteamine and 4% HQ in 40 women with facial melasma. (Note that this study originally claimed a 5% cysteamine concentration, but a letter to the editor of the International Journal of Dermatology in 2020 disputed this and proved it was 0.56%) For 120 days, volunteers applied either 0.56% cysteamine or 4% HQ nightly. Tinted sunscreen (SPF 50; PPD 19) use was required for all participants. There were no differences in colorimetric evaluations between the groups, both of which showed progressive depigmenting, or in photographic assessments. The HQ group demonstrated greater mean decreases in modified melasma area severity index (mMASI) scores (41% for HQ and 24% for cysteamine at 60 days; 53% for HQ and 38% for cysteamine at 120 days). The investigators observed that while cysteamine was safe, well tolerated, and effective, it was outperformed by HQ in terms of mMASI and melasma quality of life (MELASQoL) scores.10

Early the next year, results of a randomized, double-blind, single-center study in 20 women, conducted by Nguyen et al. comparing the efficacy of cysteamine cream with HQ for melasma treatment were published. Participants were given either treatment over 16 weeks. Ultimately, five volunteers in the cysteamine group and nine in the HQ group completed the study. There was no statistically significant difference in mMASI scores between the groups. In this notably small study, HQ was tolerated better. The researchers concluded that their findings supported the argument of comparable efficacy between cysteamine and HQ, with further studies needed to establish whether cysteamine would be an appropriate alternative to HQ.11 Notably, HQ was banned by the Food and Drug Administration in 2020 in over-the-counter products.

Cysteamine vs. Kligman’s formula

Early in 2021, Karrabi et al. published the results of a randomized, double-blind clinical trial of 50 subjects with epidermal melasma to compare cysteamine 5% with Modified Kligman’s formula. Over 4 months, participants applied once daily either cysteamine cream 5% (15 minutes exposure) or the Modified Kligman’s formula (4% hydroquinone, 0.05% retinoic acid and 0.1% betamethasone) for whole night exposure. At 2 and 4 months, a statistically significant difference in mMASI score was noted, with the percentage decline in mMASI score nearly 9% higher in the cysteamine group. The investigators concluded that cysteamine 5% demonstrated greater efficacy than the Modified Kligman’s formula and was also better tolerated.12

Cysteamine vs. tranexamic acid

Later that year, Karrabi et al. published the results of a single-blind, randomized clinical trial assessing the efficacy of tranexamic acid mesotherapy compared with cysteamine 5% cream in 54 melasma patients. For 4 consecutive months, the cysteamine 5% cream group applied the cream on lesions 30 minutes before going to sleep. Every 4 weeks until 2 months, a physician performed tranexamic acid mesotherapy (0.05 mL; 4 mg/mL) on individuals in the tranexamic acid group. The researchers concluded, after measurements using both a Dermacatch device and the mMASI, that neither treatment was significantly better than the other but fewer complications were observed in the cysteamine group.13

Safety

In 2022, Sepaskhah et al. assessed the effects of a cysteamine 5% cream and compared it with HQ 4%/ascorbic acid 3% cream for epidermal melasma in a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Sixty-five of 80 patients completed the study. The difference in mMASI scores after 4 months was not significant between the groups nor was the improvement in quality of life, but the melanin index was significantly lower in the HQ/ascorbic acid group compared with the less substantial reduction for the cysteamine group. Nevertheless, the researchers concluded that cysteamine is a safe and suitable substitute for HQ/ascorbic acid.4

Conclusion

In the last decade, cysteamine has been established as a potent depigmenting agent. Its suitability and desirability as a top consideration for melasma treatment also appears to be compelling. More RCTs comparing cysteamine and other topline therapies are warranted, but current evidence shows that cysteamine is an effective and safe therapy for melasma.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in office and as an ecommerce solution. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Konar MC et al. J Trop Pediatr. 2020 Apr 1;66(2):129-35.

2. Niazi S et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Sep;21(9):3867-75.

3. González-Molina V et al. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022 May;15(5):19-28.

4. Sepaskhah M et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jul;21(7):2871-8.

5. Desai S et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021 Dec 1;20(12):1276-9.

6. Mansouri P et al. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Jul;173(1):209-17.

7. Farshi S et al. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018 Mar;29(2):182-9.

8. Austin E et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Nov 1;18(11):S1545961619P1156X.

9. Gomes dos Santos-Neto A et al. Dermatol Ther. 2022 Dec;35(12):e15961.

10. Lima PB et al. Int J Dermatol. 2020 Dec;59(12):1531-6.

11. Nguyen J et al. Australas J Dermatol. 2021 Feb;62(1):e41-e46.

12. Karrabi M et al. Skin Res Technol. 2021 Jan;27(1):24-31.

13. Karrabi M et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 2021 Sep;313(7):539-47.

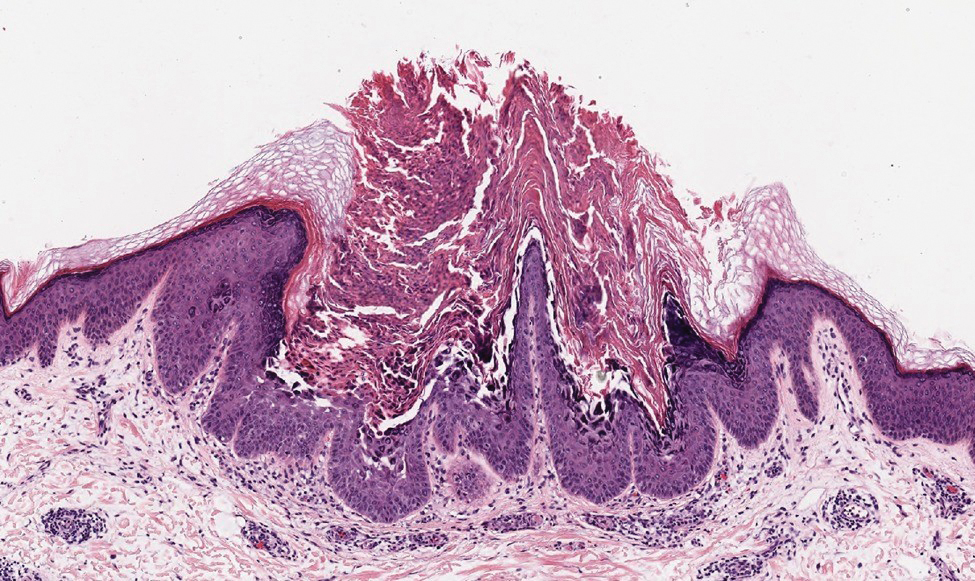

Suture Selection to Minimize Postoperative Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation in Patients With Skin of Color During Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Practice Gap

Proper suture selection is imperative for appropriate wound healing to minimize the risk for infection and inflammation and to reduce scarring. In Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), suture selection should be given high consideration in patients with skin of color.1 Using the right type of suture and wound closure technique can lead to favorable aesthetic outcomes by preventing postoperative postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) and keloids. Data on the choice of suture material in patients with skin of color are limited.

Suture selection depends on a variety of factors including but not limited to the location of the wound on the body, risk for infection, cost, availability, and the personal preference and experience of the MMS surgeon. During the COVID-19 pandemic, suturepreference among dermatologic surgeons shifted to fast-absorbing gut sutures,2 offering alternatives to synthetic monofilament polypropylene and nylon sutures. Absorbable sutures reduced the need for in-person follow-up visits without increasing the incidence of postoperative complications.

Despite these benefits, research suggests that natural absorbable gut sutures induce cutaneous inflammation and should be avoided in patients with skin of color.1,3,4 Nonabsorbable sutures are less reactive, reducing PIH after MMS in patients with skin of color.

Tools and Technique

Use of nonabsorbable stitches is a practical solution to reduce the risk for inflammation in patients with skin of color. Increased inflammation can lead to PIH and increase the risk for keloids in this patient population. Some patients will experience PIH after a surgical procedure regardless of the sutures used to repair the closure; however, one of our goals with patients with skin of color undergoing MMS is to reduce the inflammatory risk that could lead to PIH to ensure optimal aesthetic outcomes.

A middle-aged African woman with darker skin and a history of developing PIH after trauma to the skin presented to our clinic for MMS of a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans on the upper abdomen. We used a simple running suture with 4-0 nylon to close the surgical wound. We avoided fast-absorbing gut sutures because they have high tissue reactivity1,4; use of sutures with low tissue reactivity, such as nylon and polypropylene, decreases the risk for inflammation without compromising alignment of wound edges and overall cosmesis of the repair. Prolene also is cost-effective and presents a decreased risk for wound dehiscence.5 After cauterizing the wound, we placed multiple synthetic absorbable sutures first to close the wound. We then did a double-running suture of nonabsorbable monofilament suture to reapproximate the epidermal edges with minimal tension. We placed 2 sets of running stitches to minimize the risk for dehiscence along the scar.

The patient was required to return for removal of the nonabsorbable sutures; this postoperative visit was covered by health insurance at no additional cost to the patient. In comparison, long-term repeat visits to treat PIH with a laser or chemical peel would have been more costly. Given that treatment of PIH is considered cosmetic, laser treatment would have been priced at several hundred dollars per session at our institution, and the patient would likely have had a copay for a pretreatment lightening cream such as hydroquinone. Our patient had a favorable cosmetic outcome and reported no or minimal evidence of PIH months after the procedure.

Patients should be instructed to apply petrolatum twice daily, use sun-protective clothing, and cover sutures to minimize exposure to the sun and prevent crusting of the wound. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation can be proactively treated postoperatively with topical hydroquinone, which was not needed in our patient.

Practice Implications

Although some studies suggest that there are no cosmetic differences between absorbable and nonabsorbable sutures, the effect of suture type in patients with skin of color undergoing MMS often is unreported or is not studied.6,7 The high reactivity and cutaneous inflammation associated with absorbable gut sutures are important considerations in this patient population.

In patients with skin of color undergoing MMS, we use nonabsorbable epidermal sutures such as nylon and Prolene because of their low reactivity and association with favorable aesthetic outcomes. Nonabsorbable sutures can be safely used in patients of all ages who are undergoing MMS under local anesthesia.

An exception would be the use of the absorbable suture Monocryl (J&J MedTech) in patients with skin of color who need a running subcuticular wound closure because it has low tissue reactivity and maintains high tensile strength. Monocryl has been shown to create less-reactive scars, which decreases the risk for keloids.8,9

More clinical studies are needed to assess the increased susceptibility to PIH in patients with skin of color when using absorbable gut sutures.

- Williams R, Ciocon D. Mohs micrographic surgery in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:536-541. doi:10.36849/JDD.6469

- Gallop J, Andrasik W, Lucas J. Successful use of percutaneous dissolvable sutures during COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023;27:34-38. doi:10.1177/12034754221143083

- Byrne M, Aly A. The surgical suture. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39(suppl 2):S67-S72. doi:10.1093/asj/sjz036

- Koppa M, House R, Tobin V, et al. Suture material choice can increase risk of hypersensitivity in hand trauma patients. Eur J Plast Surg. 2023;46:239-243. doi:10.1007/s00238-022-01986-7

- Pandey S, Singh M, Singh K, et al. A prospective randomized study comparing non-absorbable polypropylene (Prolene®) and delayed absorbable polyglactin 910 (Vicryl®) suture material in mass closure of vertical laparotomy wounds. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:306-310. doi:10.1007/s12262-012-0492-x

- Parell GJ, Becker GD. Comparison of absorbable with nonabsorbable sutures in closure of facial skin wounds. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2003;5:488-490. doi:10.1001/archfaci.5.6.488

- Kim J, Singh Maan H, Cool AJ, et al. Fast absorbing gut suture versus cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive in the epidermal closure of linear repairs following Mohs micrographic surgery. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:24-29.

- Niessen FB, Spauwen PH, Kon M. The role of suture material in hypertrophic scar formation: Monocryl vs. Vicryl-Rapide. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39:254-260. doi:10.1097/00000637-199709000-00006

- Fosko SW, Heap D. Surgical pearl: an economical means of skin closure with absorbable suture. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2 pt 1):248-250. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70084-2

Practice Gap

Proper suture selection is imperative for appropriate wound healing to minimize the risk for infection and inflammation and to reduce scarring. In Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), suture selection should be given high consideration in patients with skin of color.1 Using the right type of suture and wound closure technique can lead to favorable aesthetic outcomes by preventing postoperative postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) and keloids. Data on the choice of suture material in patients with skin of color are limited.

Suture selection depends on a variety of factors including but not limited to the location of the wound on the body, risk for infection, cost, availability, and the personal preference and experience of the MMS surgeon. During the COVID-19 pandemic, suturepreference among dermatologic surgeons shifted to fast-absorbing gut sutures,2 offering alternatives to synthetic monofilament polypropylene and nylon sutures. Absorbable sutures reduced the need for in-person follow-up visits without increasing the incidence of postoperative complications.

Despite these benefits, research suggests that natural absorbable gut sutures induce cutaneous inflammation and should be avoided in patients with skin of color.1,3,4 Nonabsorbable sutures are less reactive, reducing PIH after MMS in patients with skin of color.

Tools and Technique

Use of nonabsorbable stitches is a practical solution to reduce the risk for inflammation in patients with skin of color. Increased inflammation can lead to PIH and increase the risk for keloids in this patient population. Some patients will experience PIH after a surgical procedure regardless of the sutures used to repair the closure; however, one of our goals with patients with skin of color undergoing MMS is to reduce the inflammatory risk that could lead to PIH to ensure optimal aesthetic outcomes.

A middle-aged African woman with darker skin and a history of developing PIH after trauma to the skin presented to our clinic for MMS of a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans on the upper abdomen. We used a simple running suture with 4-0 nylon to close the surgical wound. We avoided fast-absorbing gut sutures because they have high tissue reactivity1,4; use of sutures with low tissue reactivity, such as nylon and polypropylene, decreases the risk for inflammation without compromising alignment of wound edges and overall cosmesis of the repair. Prolene also is cost-effective and presents a decreased risk for wound dehiscence.5 After cauterizing the wound, we placed multiple synthetic absorbable sutures first to close the wound. We then did a double-running suture of nonabsorbable monofilament suture to reapproximate the epidermal edges with minimal tension. We placed 2 sets of running stitches to minimize the risk for dehiscence along the scar.

The patient was required to return for removal of the nonabsorbable sutures; this postoperative visit was covered by health insurance at no additional cost to the patient. In comparison, long-term repeat visits to treat PIH with a laser or chemical peel would have been more costly. Given that treatment of PIH is considered cosmetic, laser treatment would have been priced at several hundred dollars per session at our institution, and the patient would likely have had a copay for a pretreatment lightening cream such as hydroquinone. Our patient had a favorable cosmetic outcome and reported no or minimal evidence of PIH months after the procedure.

Patients should be instructed to apply petrolatum twice daily, use sun-protective clothing, and cover sutures to minimize exposure to the sun and prevent crusting of the wound. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation can be proactively treated postoperatively with topical hydroquinone, which was not needed in our patient.

Practice Implications

Although some studies suggest that there are no cosmetic differences between absorbable and nonabsorbable sutures, the effect of suture type in patients with skin of color undergoing MMS often is unreported or is not studied.6,7 The high reactivity and cutaneous inflammation associated with absorbable gut sutures are important considerations in this patient population.

In patients with skin of color undergoing MMS, we use nonabsorbable epidermal sutures such as nylon and Prolene because of their low reactivity and association with favorable aesthetic outcomes. Nonabsorbable sutures can be safely used in patients of all ages who are undergoing MMS under local anesthesia.

An exception would be the use of the absorbable suture Monocryl (J&J MedTech) in patients with skin of color who need a running subcuticular wound closure because it has low tissue reactivity and maintains high tensile strength. Monocryl has been shown to create less-reactive scars, which decreases the risk for keloids.8,9

More clinical studies are needed to assess the increased susceptibility to PIH in patients with skin of color when using absorbable gut sutures.

Practice Gap