User login

MD-IQ only

Anticoagulation Stewardship Efforts Via Indication Reviews at a Veterans Affairs Health Care System

Anticoagulation Stewardship Efforts Via Indication Reviews at a Veterans Affairs Health Care System

Due to the underlying mechanism of atrial fibrillation (Afib), clots can form within the left atrial appendage. Clots that become dislodged may lead to ischemic stroke and possibly death. The 2023 guidelines for atrial fibrillation from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend anticoagulation therapy for patients with an Afib diagnosis and a CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, diabetes, stroke/vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, and female sex) score pertinent for ≥ 1 non–sex-related factor (score ≥ 2 for women; ≥ 1 for men) to prevent stroke-related complications. The CHA2DS2-VASc score is a 9-point scoring tool based on comorbidities and conditions that increase risk of stroke in patients with Afib. Each value correlates to an annualized stroke risk percentage that increases as the score increases.

In clinical practice, patients meeting these thresholds are indicated for anticoagulation and are considered for indefinite use unless ≥ 1 of the following conditions are present: bleeding risk outweighs the stroke prevention benefit, Afib is episodic (< 48 hours) or a nonpharmacologic intervention, such as a left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) device is present.1

In patients with a diagnosed venous thromboembolism (VTE), such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation is used to treat the current thrombosis and prevent embolization that can ultimately lead to death. The 2021 guideline for VTE from the American College of Chest Physicians identifies certain risk factors that increase risk for VTE and categorizes them as transient or persistent. Transient risk factors include hospitalization > 3 days, major trauma, surgery, cast immobilization, hormone therapy, pregnancy, or prolonged travel > 8 hours. Persistent risk factors include malignancy, thrombophilia, and certain medications.

The guideline recommends therapy durations based on event frequency, the presence and classification of provoking risk factors, and bleeding risk. As the risk of recurrent thrombosis and other potential complications is greatest in the first 3 to 6 months after a diagnosed event, at least 3 months anticoagulation therapy is recommended following VTE diagnosis. At the 3-month mark, all regimens are suggested to be re-evaluated and considered for extended treatment duration if the event was unprovoked, recurrent, secondary to a persistent risk factor, or low bleed risk.2Anticoagulation is an important guideline-recommended pharmacologic intervention for various disease states, although its use is not without risks. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices has classified oral anticoagulants as high-alert medications. This designation was made because anticoagulant medications have the potential to cause harm when used or omitted in error and lead to life-threatening bleed or thrombotic complications.3Anticoagulation stewardship ensures that anticoagulation therapy is appropriately initiated, maintained, and discontinued when indicated. Because of the potential for harm, anticoagulation stewardship is an important part of Afib and VTE management. Pharmacists can help verify and evaluate anticoagulation therapies. Research suggests that pharmacist-led anticoagulation stewardship efforts may play a role in ensuring safer patient outcomes.4The purpose of this quality improvement (QI) study was to implement pharmacist-led anticoagulation stewardship practices at Veterans Affairs Phoenix Health Care System (VAPHCS) to identify veterans with Afib not currently on anticoagulation, as well as to identify veterans with a history of VTE events who have completed a sufficient treatment duration.

Methods

Anticoagulation stewardship efforts were implemented in 2 cohorts of patients: those with Afib who may be indicated to initiate anticoagulation, and those with a history of VTE events who may be indicated to consider anticoagulation discontinuation. Patient records were reviewed using a standardized note template, and recommendations to either initiate or discontinue anticoagulation therapy were documented. The VAPHCS Research Service reviewed this study and determined that it was not research and was exempt from institutional review board review.

Atrial Fibrillation Cohort

A population health dashboard created by the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter Targeting the uNTreated: a focus on health care disparities (SPAFF-TNT-D) national VA study team was used to identify veterans at VAPHCS with a diagnosis of Afib without an active VA prescription for an anticoagulant. The dashboard filtered and produced data points from the medical record that correlated to the components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score. All veterans identified by the dashboard with scores of 7 or 8 were included. No patients had a score of 9. Comprehensive chart reviews of available VA and non–VA-provided care records were conducted by the investigators, and a standardized note template designed by the SPAFF-TNT-D team (eAppendix 1) was used to document findings within the electronic health record (EHR). If anticoagulation was deemed to be indicated, the assigned primary care practitioner (PCP) as listed in the EHR was alerted to the note by the investigators for further evaluation and consideration of prescribing anticoagulation.

Venous Thromboembolism Cohort

VAPHCS pharmacy informatics pulled data that included veterans with documented VTE and an active VA anticoagulant prescription between November 2022 and November 2023. Veterans were reviewed in chronological order based on when the anticoagulant prescription was written. All veterans were included until an equal number of charts were reviewed in both the Afib and VTE cohorts. Comprehensive chart review of available VA- and non–VA-provided care records was conducted by the investigators, and a standardized note template as designed by the investigators (eAppendix 2) was used to document findings within the EHR. If the duration of anticoagulation therapy was deemed sufficient, the assigned anticoagulation clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP) was alerted to the note by the investigators for further evaluation and consideration of discontinuing anticoagulation.

EHR reviews were conducted in October and November 2023 and lasted about 10 to 20 minutes per patient. To evaluate completeness and accuracy of the documented findings within the EHR, both investigators reviewed and cosigned the completed note template and verified the correct PCP was alerted to the recommendation for appropriate continuity of care. Results were reviewed in March 2024.

Outcomes

Atrial fibrillation cohort. The primary outcome was the number of veterans with Afib who were recommended to start anticoagulation therapy. Additional outcomes evaluated included the number of interventions completed, action taken by PCPs in response to the provided recommendation, and reasons provided by the investigators for not recommending initiation of anticoagulation therapy in specific veteran cases.

Venous thromboembolism cohort. The primary outcome was the number of veterans with a history of VTE events recommended to discontinue anticoagulation therapy. Additional outcomes included number of interventions completed, action taken by the anticoagulation CPP in response to the provided recommendation, and reasons provided by the investigators for not recommending discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy in specific veteran cases.

Analysis

Sample size was determined by the inclusion criteria and was not designed to attain statistical power. Data embedded in the Afib cohort standardized note template, also known as health factors, were later used for data analysis. Recommendations in the VTE cohort were manually tracked and recorded by the investigators. Results for this study were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

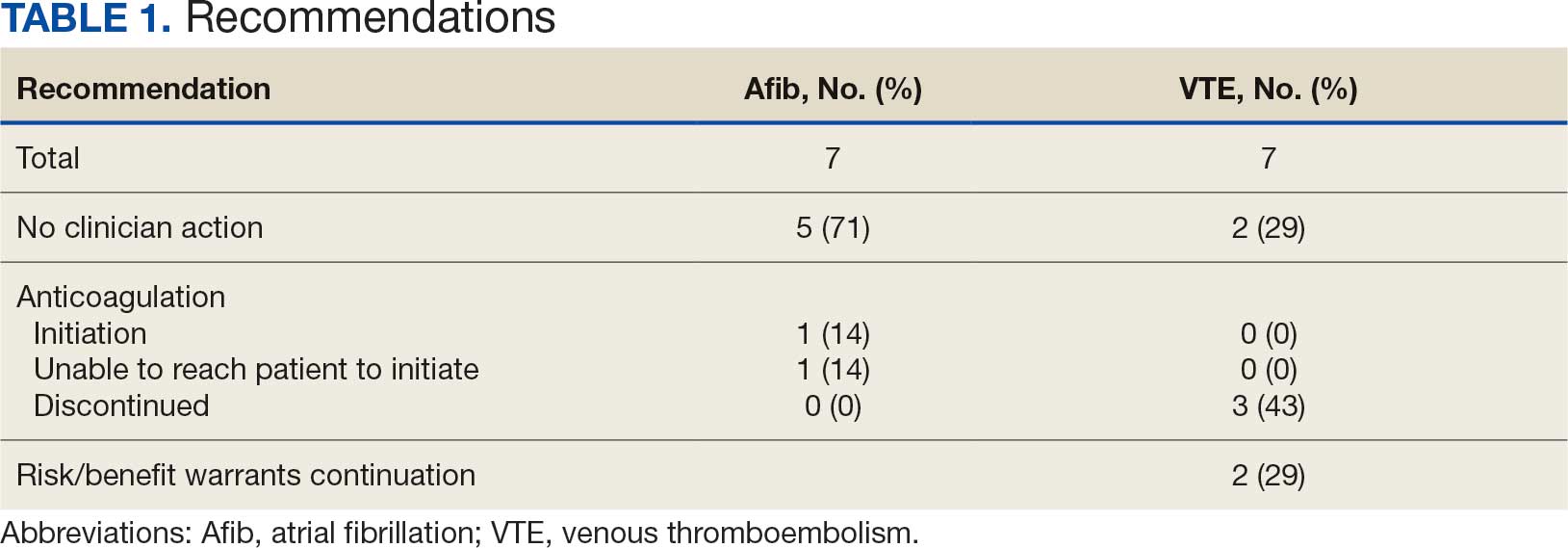

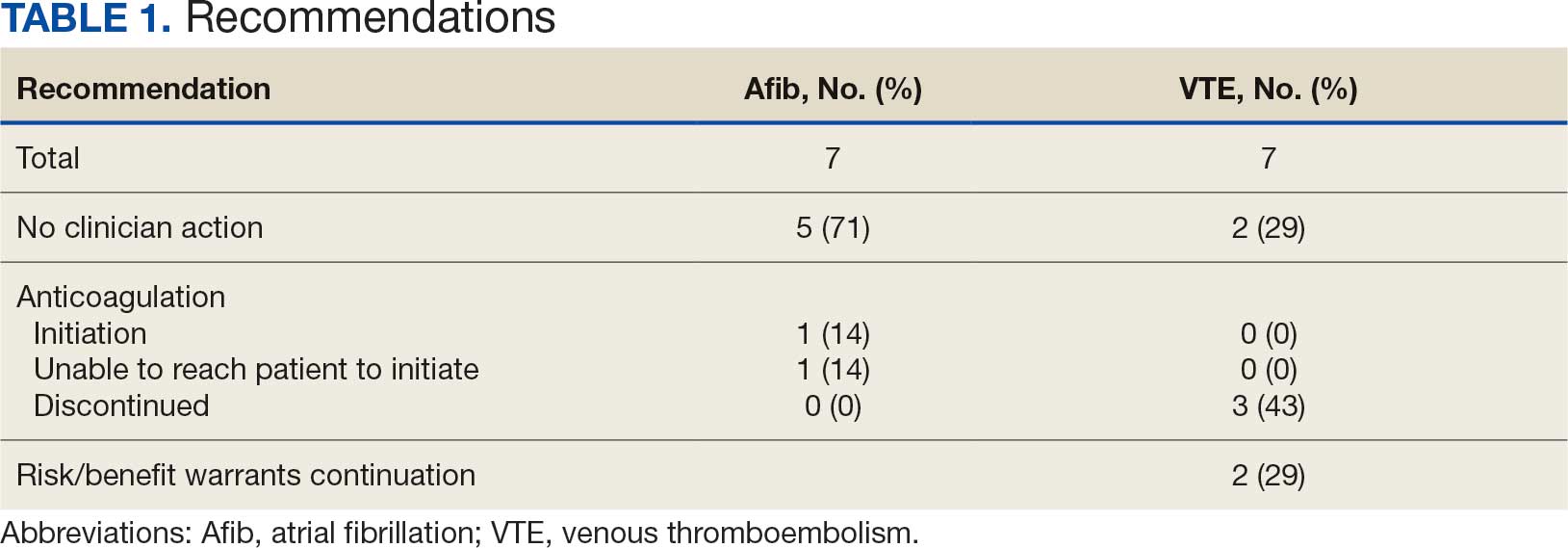

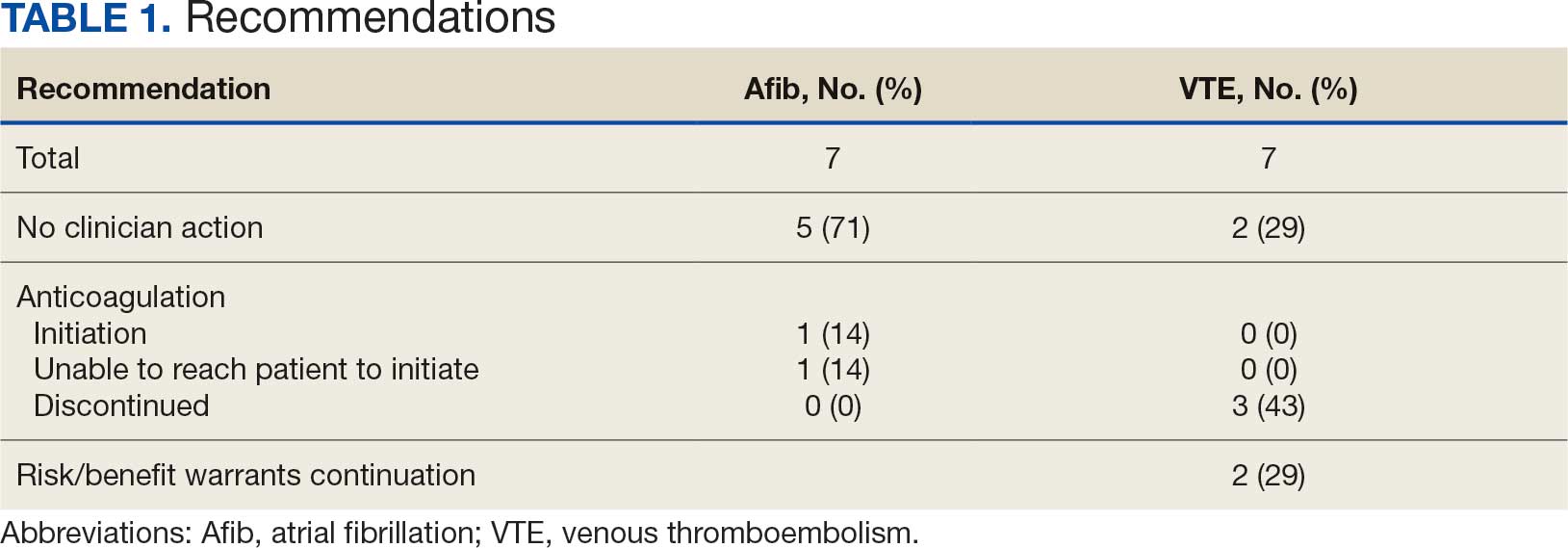

A total of 114 veterans were reviewed and included in this study: 57 in each cohort. Seven recommendations were made regarding anticoagulation initiation for patients with Afib and 7 were made for anticoagulation discontinuation for patients with VTE (Table 1).

In the Afib cohort, 1 veteran was successfully initiated on anticoagulation therapy and 1 veteran was deemed appropriate for initiation of anticoagulation but was not reachable. Of the 5 recommendations with no action taken, 4 PCPs acknowledged the alert with no further documentation, and 1 PCP deferred the decision to cardiology with no further documentation. In the VTE cohort, 3 veterans successfully discontinued anticoagulation therapy and 2 veterans were further evaluated by the anticoagulation CPP and deemed appropriate to continue therapy based on potential for malignancy. Of the 2 recommendations with no action taken, 1 anticoagulation CPP acknowledged the alert with no further documentation and 1 anticoagulation CPP suggested further evaluation by PCP with no further documentation.

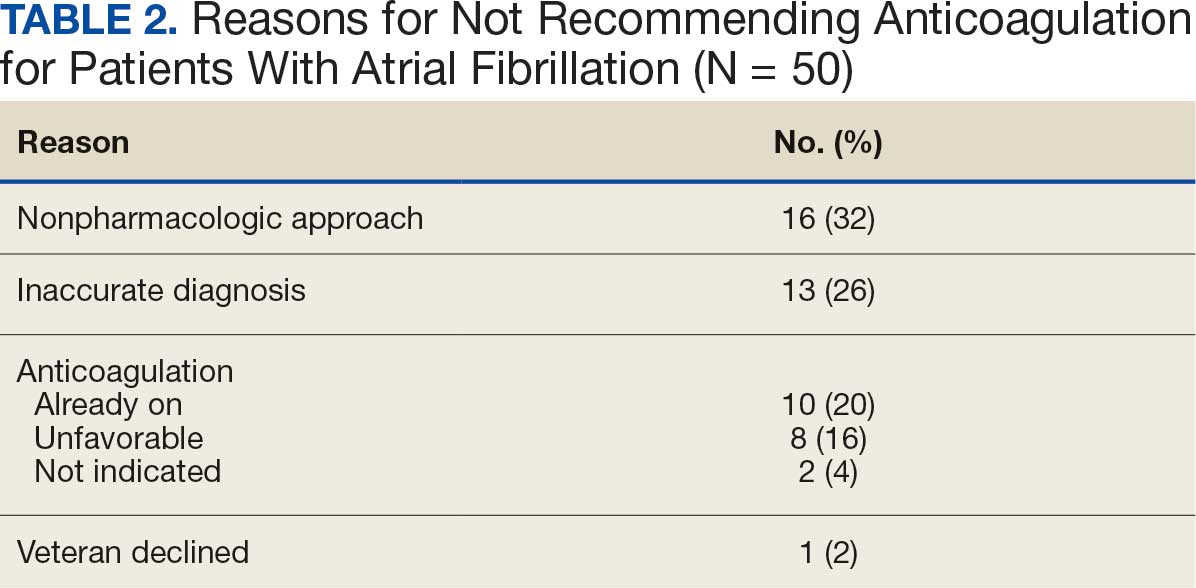

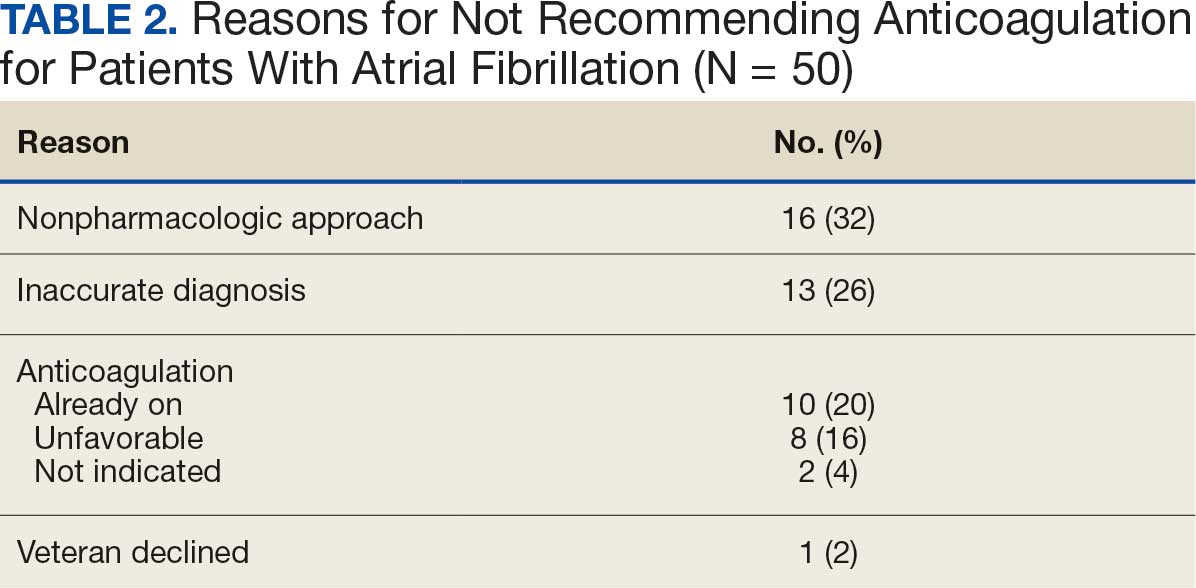

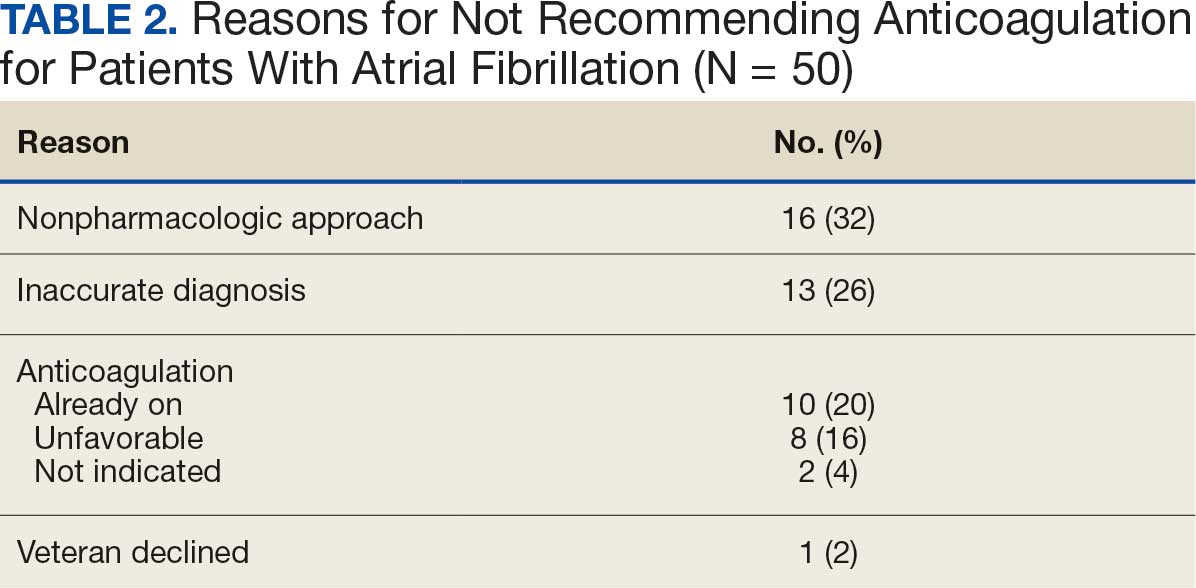

In the Afib cohort, a nonpharmacologic approach was defined as documentation of a LAAO device. An inaccurate diagnosis was defined as an Afib diagnosis being used in a previous visit, although there was no further confirmation of diagnosis via chart review. Veterans classified as already being on anticoagulation had documentation of non–VA-written anticoagulant prescriptions or receiving a supply of anticoagulants from a facility such as a nursing home. Anticoagulation was defined as unfavorable if a documented risk/benefit conversation was found via EHR review. Anticoagulation was defined as not indicated if the Afib was documented as transient, episodic, or historical (Table 2).

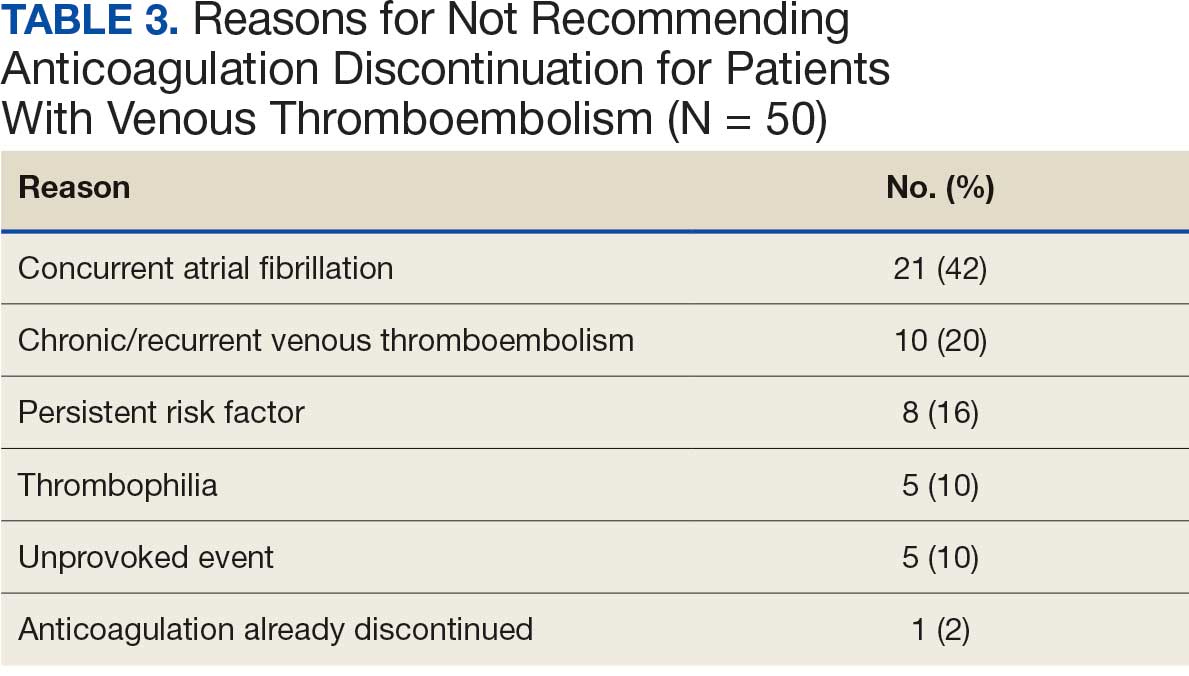

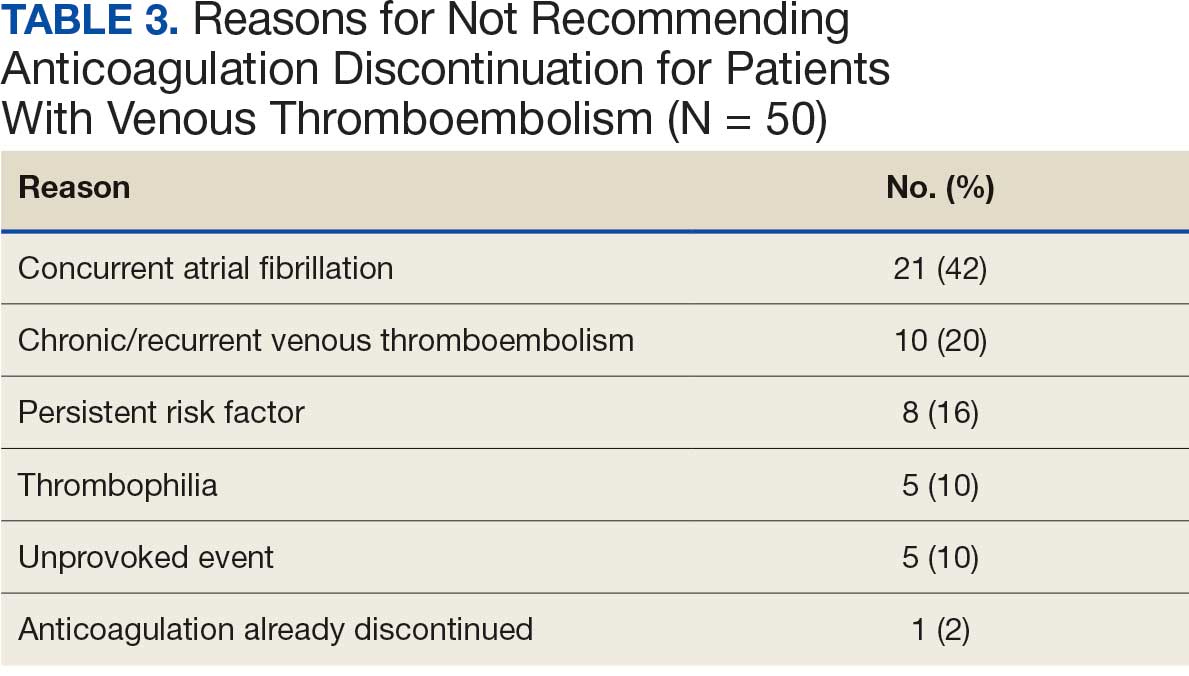

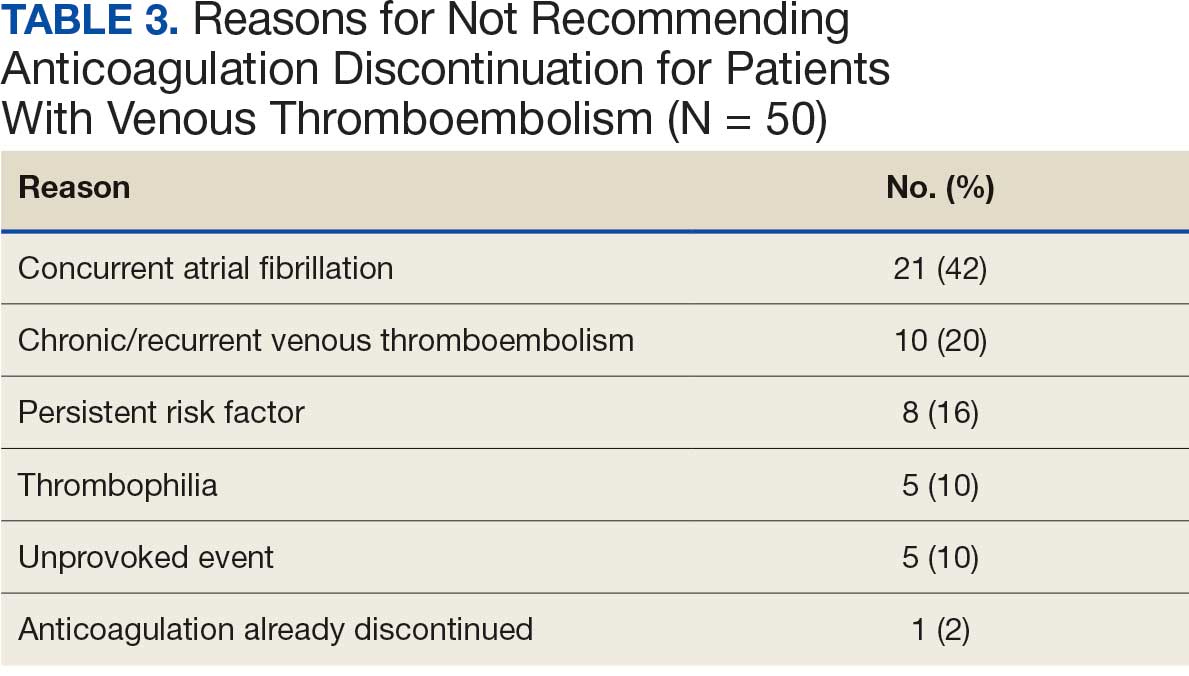

In the VTE cohort, no recommendations for discontinuation were made for veterans indicated to continue anticoagulation due to a concurrent Afib diagnosis. Chronic or recurrent events were defined as documentation of multiple VTE events and associated dates in the EHR. Persistent risk factors included malignancy or medications contributing to hypercoagulable states. Thrombophilia was defined as having documentation of a diagnosis in the EHR. An unprovoked event was defined as VTE without any documented transient risk factors (eg, hospitalization, trauma, surgery, cast immobilization, hormone therapy, pregnancy, or prolonged travel). Anticoagulation had already been discontinued in 1 veteran after the data were collected but before chart review occurred (Table 3).

Discussion

Pharmacy-led indication reviews resulted in appropriate recommendations for anticoagulation use in veterans with Afib and a history of VTE events. Overall, 12.3% of chart reviews in each cohort resulted in a recommendation being made, which was similar to the rate found by Koolian et al.5 In that study, 10% of recommendations were related to initiation or interruption of anticoagulation. This recommendation category consisted of several subcategories, including “suggesting therapeutic anticoagulation when none is currently ordered” and “suggesting anticoagulation cessation if no longer indicated,” but specific numerical prevalence was not provided.5

Online dashboard use allowed for greater population health management and identification of veterans with Afib who were not on active anticoagulation, providing opportunities to prevent stroke-related complications. Wang et al completed a similarly designed study that included a population health tool to identify patients with Afib who were not on anticoagulation and implemented pharmacist-led chart review and facilitation of recommendations to the responsible clinician. This study reviewed 1727 patients and recommended initiation of anticoagulation therapy for 75 (4.3%).6 The current study had a higher percentage of patients with recommendations for changes despite its smaller size.

Evaluating the duration of therapy for anticoagulation in veterans with a history of VTE events provided an opportunity to reduce unnecessary exposure to anticoagulation and minimize bleeding risks. Using a chart review process and standardized note template enabled the documentation of pertinent information that could be readily reviewed by the PCP. This process is a step toward ensuring VAPHCS PCPs provide guideline-recommended care and actively prevent stroke and bleeding complications. Adoption of this process into the current VAPHCS Anticoagulation Clinic workflow for review of veterans with either Afib or VTE could lead to more EHRs being reviewed and recommendations made, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Therapeutic interventions based on the recommendations were completed for 1 of 7 veterans (14%) and 3 of 7 veterans (43%) in the Afib and VTE cohorts, respectively. The prevalence of completed interventions in this anticoagulation stewardship study was higher than those in Wang et al, who found only 9% of their recommendations resulted in PCPs considering action related to anticoagulation, and only 4% were successfully initiated.6

In the Afib cohort, veterans identified by the dashboard with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 7 or 8 were prioritized for review. Reviewing these veterans ensured that patients with the highest stroke risk were sufficiently evaluated and started on anticoagulation as needed to reduce stroke-related complications. In contrast, because these veterans had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores, they may have already been evaluated for anticoagulation in the past and had a documented rationale for not being placed on anticoagulation (LAAO device placement was the most common rationale). Focusing on veterans with a lower CHA2DS2-VASc score such as 1 for men or 2 for women could potentially include more opportunities for recommendations. Although stroke risk may be lower in this population compared with those with higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores, guideline-recommended anticoagulation use may be missed for these patients.

In the VTE cohort, veterans with an anticoagulant prescription written 12 months before data collection were prioritized for review. Reviewing these veterans ensured that anticoagulation therapy met guideline recommendations of at least 3 months, with potential for extended duration upon further evaluation by a provider at that time. Based on collected results, most veterans were already reevaluated and had documented reasons why anticoagulation was still indicated; concurrent Afib was most common followed by chronic or recurrent VTE. Reviewing veterans with more recent prescriptions just over the recommended 3-month duration could potentially include more opportunities for recommendations to be made. It is more likely that by 3 months another PCP had not already weighed in on the duration of therapy, and the anticoagulation CPP could ensure a thorough review is conducted with guideline-based recommendations.

Most published literature on anticoagulation stewardship efforts is focused on inpatient management and policy changes, or concentrate on attributes of therapy such as appropriate dosing and drug interactions. This study highlighted that gaps in care related to anticoagulation use and discontinuation are present in the VAPHCS population and can be appropriately addressed via pharmacist-led indication reviews. Future studies designed to focus on initiating anticoagulation where appropriate, and discontinuing where a sufficient treatment period has been completed, are warranted to minimize this gap in care and allow health systems to work toward process changes to ensure safe and optimized care is provided for the patients they serve.

Limitations

In the Afib cohort, 5 of 7 recommendations (71%) had no further action taken by the PCP, which may represent a barrier to care. In contrast, 2 of 7 recommendations (29%) had no further action in the VTE cohort. It is possible that the difference can be attributed to the anticoagulation CPP receiving VTE alerts and PCPs receiving Afib alerts. The anticoagulation CPP was familiar with this QI study and may have better understood the purpose of the chart review and the need to provide a timely response. PCPs may have been less likely to take action because they were unfamiliar with the anticoagulation stewardship initiative and standardized note template or overwhelmed by too many EHR alerts.

The lack of PCP response to a virtual alert or message also was observed by Wang et al, whereas Koolian et al reported higher intervention completion rates, with verbal recommendations being made to the responsible clinicians. To further ensure these pertinent recommendations for anticoagulation initiation in veterans with Afib are properly reviewed and evaluated, future research could include intentional follow-up with the PCP regarding the alert, PCP-specific education about the anticoagulation stewardship initiative and the role of the standardized note template, and collaboration with PCPs to identify alternative ways to relay recommendations in a way that would ensure the completion of appropriate and timely review.

Conclusions

This study identified gaps in care related to anticoagulation needs in the VAPHCS veteran population. Utilizing a standardized indication review process allows pharmacists to evaluate anticoagulant use for both appropriate indication and duration of therapy. Providing recommendations via chart review notes and alerting respective PCPs and CPPs results in veterans receiving safe and optimized care regarding their anticoagulation needs.

- Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149:e1-e156. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193

- Stevens SM, Woller SC, Kreuziger LB, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021;160:e545-e608. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.055

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). List of high-alert medications in community/ambulatory care settings. ISMP. September 30, 2021. Accessed September 11, 2025. https://home.ecri.org/blogs/ismp-resources/high-alert-medications-in-community-ambulatory-care-settings

- Burnett AE, Barnes GD. A call to action for anticoagulation stewardship. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;6:e12757. doi:10.1002/rth2.12757

- Koolian M, Wiseman D, Mantzanis H, et al. Anticoagulation stewardship: descriptive analysis of a novel approach to appropriate anticoagulant prescription. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;6:e12758. doi:10.1002/rth2.12758

- Wang SV, Rogers JR, Jin Y, et al. Stepped-wedge randomised trial to evaluate population health intervention designed to increase appropriate anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:835-842. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009367

Due to the underlying mechanism of atrial fibrillation (Afib), clots can form within the left atrial appendage. Clots that become dislodged may lead to ischemic stroke and possibly death. The 2023 guidelines for atrial fibrillation from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend anticoagulation therapy for patients with an Afib diagnosis and a CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, diabetes, stroke/vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, and female sex) score pertinent for ≥ 1 non–sex-related factor (score ≥ 2 for women; ≥ 1 for men) to prevent stroke-related complications. The CHA2DS2-VASc score is a 9-point scoring tool based on comorbidities and conditions that increase risk of stroke in patients with Afib. Each value correlates to an annualized stroke risk percentage that increases as the score increases.

In clinical practice, patients meeting these thresholds are indicated for anticoagulation and are considered for indefinite use unless ≥ 1 of the following conditions are present: bleeding risk outweighs the stroke prevention benefit, Afib is episodic (< 48 hours) or a nonpharmacologic intervention, such as a left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) device is present.1

In patients with a diagnosed venous thromboembolism (VTE), such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation is used to treat the current thrombosis and prevent embolization that can ultimately lead to death. The 2021 guideline for VTE from the American College of Chest Physicians identifies certain risk factors that increase risk for VTE and categorizes them as transient or persistent. Transient risk factors include hospitalization > 3 days, major trauma, surgery, cast immobilization, hormone therapy, pregnancy, or prolonged travel > 8 hours. Persistent risk factors include malignancy, thrombophilia, and certain medications.

The guideline recommends therapy durations based on event frequency, the presence and classification of provoking risk factors, and bleeding risk. As the risk of recurrent thrombosis and other potential complications is greatest in the first 3 to 6 months after a diagnosed event, at least 3 months anticoagulation therapy is recommended following VTE diagnosis. At the 3-month mark, all regimens are suggested to be re-evaluated and considered for extended treatment duration if the event was unprovoked, recurrent, secondary to a persistent risk factor, or low bleed risk.2Anticoagulation is an important guideline-recommended pharmacologic intervention for various disease states, although its use is not without risks. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices has classified oral anticoagulants as high-alert medications. This designation was made because anticoagulant medications have the potential to cause harm when used or omitted in error and lead to life-threatening bleed or thrombotic complications.3Anticoagulation stewardship ensures that anticoagulation therapy is appropriately initiated, maintained, and discontinued when indicated. Because of the potential for harm, anticoagulation stewardship is an important part of Afib and VTE management. Pharmacists can help verify and evaluate anticoagulation therapies. Research suggests that pharmacist-led anticoagulation stewardship efforts may play a role in ensuring safer patient outcomes.4The purpose of this quality improvement (QI) study was to implement pharmacist-led anticoagulation stewardship practices at Veterans Affairs Phoenix Health Care System (VAPHCS) to identify veterans with Afib not currently on anticoagulation, as well as to identify veterans with a history of VTE events who have completed a sufficient treatment duration.

Methods

Anticoagulation stewardship efforts were implemented in 2 cohorts of patients: those with Afib who may be indicated to initiate anticoagulation, and those with a history of VTE events who may be indicated to consider anticoagulation discontinuation. Patient records were reviewed using a standardized note template, and recommendations to either initiate or discontinue anticoagulation therapy were documented. The VAPHCS Research Service reviewed this study and determined that it was not research and was exempt from institutional review board review.

Atrial Fibrillation Cohort

A population health dashboard created by the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter Targeting the uNTreated: a focus on health care disparities (SPAFF-TNT-D) national VA study team was used to identify veterans at VAPHCS with a diagnosis of Afib without an active VA prescription for an anticoagulant. The dashboard filtered and produced data points from the medical record that correlated to the components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score. All veterans identified by the dashboard with scores of 7 or 8 were included. No patients had a score of 9. Comprehensive chart reviews of available VA and non–VA-provided care records were conducted by the investigators, and a standardized note template designed by the SPAFF-TNT-D team (eAppendix 1) was used to document findings within the electronic health record (EHR). If anticoagulation was deemed to be indicated, the assigned primary care practitioner (PCP) as listed in the EHR was alerted to the note by the investigators for further evaluation and consideration of prescribing anticoagulation.

Venous Thromboembolism Cohort

VAPHCS pharmacy informatics pulled data that included veterans with documented VTE and an active VA anticoagulant prescription between November 2022 and November 2023. Veterans were reviewed in chronological order based on when the anticoagulant prescription was written. All veterans were included until an equal number of charts were reviewed in both the Afib and VTE cohorts. Comprehensive chart review of available VA- and non–VA-provided care records was conducted by the investigators, and a standardized note template as designed by the investigators (eAppendix 2) was used to document findings within the EHR. If the duration of anticoagulation therapy was deemed sufficient, the assigned anticoagulation clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP) was alerted to the note by the investigators for further evaluation and consideration of discontinuing anticoagulation.

EHR reviews were conducted in October and November 2023 and lasted about 10 to 20 minutes per patient. To evaluate completeness and accuracy of the documented findings within the EHR, both investigators reviewed and cosigned the completed note template and verified the correct PCP was alerted to the recommendation for appropriate continuity of care. Results were reviewed in March 2024.

Outcomes

Atrial fibrillation cohort. The primary outcome was the number of veterans with Afib who were recommended to start anticoagulation therapy. Additional outcomes evaluated included the number of interventions completed, action taken by PCPs in response to the provided recommendation, and reasons provided by the investigators for not recommending initiation of anticoagulation therapy in specific veteran cases.

Venous thromboembolism cohort. The primary outcome was the number of veterans with a history of VTE events recommended to discontinue anticoagulation therapy. Additional outcomes included number of interventions completed, action taken by the anticoagulation CPP in response to the provided recommendation, and reasons provided by the investigators for not recommending discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy in specific veteran cases.

Analysis

Sample size was determined by the inclusion criteria and was not designed to attain statistical power. Data embedded in the Afib cohort standardized note template, also known as health factors, were later used for data analysis. Recommendations in the VTE cohort were manually tracked and recorded by the investigators. Results for this study were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

A total of 114 veterans were reviewed and included in this study: 57 in each cohort. Seven recommendations were made regarding anticoagulation initiation for patients with Afib and 7 were made for anticoagulation discontinuation for patients with VTE (Table 1).

In the Afib cohort, 1 veteran was successfully initiated on anticoagulation therapy and 1 veteran was deemed appropriate for initiation of anticoagulation but was not reachable. Of the 5 recommendations with no action taken, 4 PCPs acknowledged the alert with no further documentation, and 1 PCP deferred the decision to cardiology with no further documentation. In the VTE cohort, 3 veterans successfully discontinued anticoagulation therapy and 2 veterans were further evaluated by the anticoagulation CPP and deemed appropriate to continue therapy based on potential for malignancy. Of the 2 recommendations with no action taken, 1 anticoagulation CPP acknowledged the alert with no further documentation and 1 anticoagulation CPP suggested further evaluation by PCP with no further documentation.

In the Afib cohort, a nonpharmacologic approach was defined as documentation of a LAAO device. An inaccurate diagnosis was defined as an Afib diagnosis being used in a previous visit, although there was no further confirmation of diagnosis via chart review. Veterans classified as already being on anticoagulation had documentation of non–VA-written anticoagulant prescriptions or receiving a supply of anticoagulants from a facility such as a nursing home. Anticoagulation was defined as unfavorable if a documented risk/benefit conversation was found via EHR review. Anticoagulation was defined as not indicated if the Afib was documented as transient, episodic, or historical (Table 2).

In the VTE cohort, no recommendations for discontinuation were made for veterans indicated to continue anticoagulation due to a concurrent Afib diagnosis. Chronic or recurrent events were defined as documentation of multiple VTE events and associated dates in the EHR. Persistent risk factors included malignancy or medications contributing to hypercoagulable states. Thrombophilia was defined as having documentation of a diagnosis in the EHR. An unprovoked event was defined as VTE without any documented transient risk factors (eg, hospitalization, trauma, surgery, cast immobilization, hormone therapy, pregnancy, or prolonged travel). Anticoagulation had already been discontinued in 1 veteran after the data were collected but before chart review occurred (Table 3).

Discussion

Pharmacy-led indication reviews resulted in appropriate recommendations for anticoagulation use in veterans with Afib and a history of VTE events. Overall, 12.3% of chart reviews in each cohort resulted in a recommendation being made, which was similar to the rate found by Koolian et al.5 In that study, 10% of recommendations were related to initiation or interruption of anticoagulation. This recommendation category consisted of several subcategories, including “suggesting therapeutic anticoagulation when none is currently ordered” and “suggesting anticoagulation cessation if no longer indicated,” but specific numerical prevalence was not provided.5

Online dashboard use allowed for greater population health management and identification of veterans with Afib who were not on active anticoagulation, providing opportunities to prevent stroke-related complications. Wang et al completed a similarly designed study that included a population health tool to identify patients with Afib who were not on anticoagulation and implemented pharmacist-led chart review and facilitation of recommendations to the responsible clinician. This study reviewed 1727 patients and recommended initiation of anticoagulation therapy for 75 (4.3%).6 The current study had a higher percentage of patients with recommendations for changes despite its smaller size.

Evaluating the duration of therapy for anticoagulation in veterans with a history of VTE events provided an opportunity to reduce unnecessary exposure to anticoagulation and minimize bleeding risks. Using a chart review process and standardized note template enabled the documentation of pertinent information that could be readily reviewed by the PCP. This process is a step toward ensuring VAPHCS PCPs provide guideline-recommended care and actively prevent stroke and bleeding complications. Adoption of this process into the current VAPHCS Anticoagulation Clinic workflow for review of veterans with either Afib or VTE could lead to more EHRs being reviewed and recommendations made, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Therapeutic interventions based on the recommendations were completed for 1 of 7 veterans (14%) and 3 of 7 veterans (43%) in the Afib and VTE cohorts, respectively. The prevalence of completed interventions in this anticoagulation stewardship study was higher than those in Wang et al, who found only 9% of their recommendations resulted in PCPs considering action related to anticoagulation, and only 4% were successfully initiated.6

In the Afib cohort, veterans identified by the dashboard with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 7 or 8 were prioritized for review. Reviewing these veterans ensured that patients with the highest stroke risk were sufficiently evaluated and started on anticoagulation as needed to reduce stroke-related complications. In contrast, because these veterans had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores, they may have already been evaluated for anticoagulation in the past and had a documented rationale for not being placed on anticoagulation (LAAO device placement was the most common rationale). Focusing on veterans with a lower CHA2DS2-VASc score such as 1 for men or 2 for women could potentially include more opportunities for recommendations. Although stroke risk may be lower in this population compared with those with higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores, guideline-recommended anticoagulation use may be missed for these patients.

In the VTE cohort, veterans with an anticoagulant prescription written 12 months before data collection were prioritized for review. Reviewing these veterans ensured that anticoagulation therapy met guideline recommendations of at least 3 months, with potential for extended duration upon further evaluation by a provider at that time. Based on collected results, most veterans were already reevaluated and had documented reasons why anticoagulation was still indicated; concurrent Afib was most common followed by chronic or recurrent VTE. Reviewing veterans with more recent prescriptions just over the recommended 3-month duration could potentially include more opportunities for recommendations to be made. It is more likely that by 3 months another PCP had not already weighed in on the duration of therapy, and the anticoagulation CPP could ensure a thorough review is conducted with guideline-based recommendations.

Most published literature on anticoagulation stewardship efforts is focused on inpatient management and policy changes, or concentrate on attributes of therapy such as appropriate dosing and drug interactions. This study highlighted that gaps in care related to anticoagulation use and discontinuation are present in the VAPHCS population and can be appropriately addressed via pharmacist-led indication reviews. Future studies designed to focus on initiating anticoagulation where appropriate, and discontinuing where a sufficient treatment period has been completed, are warranted to minimize this gap in care and allow health systems to work toward process changes to ensure safe and optimized care is provided for the patients they serve.

Limitations

In the Afib cohort, 5 of 7 recommendations (71%) had no further action taken by the PCP, which may represent a barrier to care. In contrast, 2 of 7 recommendations (29%) had no further action in the VTE cohort. It is possible that the difference can be attributed to the anticoagulation CPP receiving VTE alerts and PCPs receiving Afib alerts. The anticoagulation CPP was familiar with this QI study and may have better understood the purpose of the chart review and the need to provide a timely response. PCPs may have been less likely to take action because they were unfamiliar with the anticoagulation stewardship initiative and standardized note template or overwhelmed by too many EHR alerts.

The lack of PCP response to a virtual alert or message also was observed by Wang et al, whereas Koolian et al reported higher intervention completion rates, with verbal recommendations being made to the responsible clinicians. To further ensure these pertinent recommendations for anticoagulation initiation in veterans with Afib are properly reviewed and evaluated, future research could include intentional follow-up with the PCP regarding the alert, PCP-specific education about the anticoagulation stewardship initiative and the role of the standardized note template, and collaboration with PCPs to identify alternative ways to relay recommendations in a way that would ensure the completion of appropriate and timely review.

Conclusions

This study identified gaps in care related to anticoagulation needs in the VAPHCS veteran population. Utilizing a standardized indication review process allows pharmacists to evaluate anticoagulant use for both appropriate indication and duration of therapy. Providing recommendations via chart review notes and alerting respective PCPs and CPPs results in veterans receiving safe and optimized care regarding their anticoagulation needs.

Due to the underlying mechanism of atrial fibrillation (Afib), clots can form within the left atrial appendage. Clots that become dislodged may lead to ischemic stroke and possibly death. The 2023 guidelines for atrial fibrillation from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend anticoagulation therapy for patients with an Afib diagnosis and a CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, diabetes, stroke/vascular disease, age 65 to 74 years, and female sex) score pertinent for ≥ 1 non–sex-related factor (score ≥ 2 for women; ≥ 1 for men) to prevent stroke-related complications. The CHA2DS2-VASc score is a 9-point scoring tool based on comorbidities and conditions that increase risk of stroke in patients with Afib. Each value correlates to an annualized stroke risk percentage that increases as the score increases.

In clinical practice, patients meeting these thresholds are indicated for anticoagulation and are considered for indefinite use unless ≥ 1 of the following conditions are present: bleeding risk outweighs the stroke prevention benefit, Afib is episodic (< 48 hours) or a nonpharmacologic intervention, such as a left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) device is present.1

In patients with a diagnosed venous thromboembolism (VTE), such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, anticoagulation is used to treat the current thrombosis and prevent embolization that can ultimately lead to death. The 2021 guideline for VTE from the American College of Chest Physicians identifies certain risk factors that increase risk for VTE and categorizes them as transient or persistent. Transient risk factors include hospitalization > 3 days, major trauma, surgery, cast immobilization, hormone therapy, pregnancy, or prolonged travel > 8 hours. Persistent risk factors include malignancy, thrombophilia, and certain medications.

The guideline recommends therapy durations based on event frequency, the presence and classification of provoking risk factors, and bleeding risk. As the risk of recurrent thrombosis and other potential complications is greatest in the first 3 to 6 months after a diagnosed event, at least 3 months anticoagulation therapy is recommended following VTE diagnosis. At the 3-month mark, all regimens are suggested to be re-evaluated and considered for extended treatment duration if the event was unprovoked, recurrent, secondary to a persistent risk factor, or low bleed risk.2Anticoagulation is an important guideline-recommended pharmacologic intervention for various disease states, although its use is not without risks. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices has classified oral anticoagulants as high-alert medications. This designation was made because anticoagulant medications have the potential to cause harm when used or omitted in error and lead to life-threatening bleed or thrombotic complications.3Anticoagulation stewardship ensures that anticoagulation therapy is appropriately initiated, maintained, and discontinued when indicated. Because of the potential for harm, anticoagulation stewardship is an important part of Afib and VTE management. Pharmacists can help verify and evaluate anticoagulation therapies. Research suggests that pharmacist-led anticoagulation stewardship efforts may play a role in ensuring safer patient outcomes.4The purpose of this quality improvement (QI) study was to implement pharmacist-led anticoagulation stewardship practices at Veterans Affairs Phoenix Health Care System (VAPHCS) to identify veterans with Afib not currently on anticoagulation, as well as to identify veterans with a history of VTE events who have completed a sufficient treatment duration.

Methods

Anticoagulation stewardship efforts were implemented in 2 cohorts of patients: those with Afib who may be indicated to initiate anticoagulation, and those with a history of VTE events who may be indicated to consider anticoagulation discontinuation. Patient records were reviewed using a standardized note template, and recommendations to either initiate or discontinue anticoagulation therapy were documented. The VAPHCS Research Service reviewed this study and determined that it was not research and was exempt from institutional review board review.

Atrial Fibrillation Cohort

A population health dashboard created by the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter Targeting the uNTreated: a focus on health care disparities (SPAFF-TNT-D) national VA study team was used to identify veterans at VAPHCS with a diagnosis of Afib without an active VA prescription for an anticoagulant. The dashboard filtered and produced data points from the medical record that correlated to the components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score. All veterans identified by the dashboard with scores of 7 or 8 were included. No patients had a score of 9. Comprehensive chart reviews of available VA and non–VA-provided care records were conducted by the investigators, and a standardized note template designed by the SPAFF-TNT-D team (eAppendix 1) was used to document findings within the electronic health record (EHR). If anticoagulation was deemed to be indicated, the assigned primary care practitioner (PCP) as listed in the EHR was alerted to the note by the investigators for further evaluation and consideration of prescribing anticoagulation.

Venous Thromboembolism Cohort

VAPHCS pharmacy informatics pulled data that included veterans with documented VTE and an active VA anticoagulant prescription between November 2022 and November 2023. Veterans were reviewed in chronological order based on when the anticoagulant prescription was written. All veterans were included until an equal number of charts were reviewed in both the Afib and VTE cohorts. Comprehensive chart review of available VA- and non–VA-provided care records was conducted by the investigators, and a standardized note template as designed by the investigators (eAppendix 2) was used to document findings within the EHR. If the duration of anticoagulation therapy was deemed sufficient, the assigned anticoagulation clinical pharmacist practitioner (CPP) was alerted to the note by the investigators for further evaluation and consideration of discontinuing anticoagulation.

EHR reviews were conducted in October and November 2023 and lasted about 10 to 20 minutes per patient. To evaluate completeness and accuracy of the documented findings within the EHR, both investigators reviewed and cosigned the completed note template and verified the correct PCP was alerted to the recommendation for appropriate continuity of care. Results were reviewed in March 2024.

Outcomes

Atrial fibrillation cohort. The primary outcome was the number of veterans with Afib who were recommended to start anticoagulation therapy. Additional outcomes evaluated included the number of interventions completed, action taken by PCPs in response to the provided recommendation, and reasons provided by the investigators for not recommending initiation of anticoagulation therapy in specific veteran cases.

Venous thromboembolism cohort. The primary outcome was the number of veterans with a history of VTE events recommended to discontinue anticoagulation therapy. Additional outcomes included number of interventions completed, action taken by the anticoagulation CPP in response to the provided recommendation, and reasons provided by the investigators for not recommending discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy in specific veteran cases.

Analysis

Sample size was determined by the inclusion criteria and was not designed to attain statistical power. Data embedded in the Afib cohort standardized note template, also known as health factors, were later used for data analysis. Recommendations in the VTE cohort were manually tracked and recorded by the investigators. Results for this study were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

A total of 114 veterans were reviewed and included in this study: 57 in each cohort. Seven recommendations were made regarding anticoagulation initiation for patients with Afib and 7 were made for anticoagulation discontinuation for patients with VTE (Table 1).

In the Afib cohort, 1 veteran was successfully initiated on anticoagulation therapy and 1 veteran was deemed appropriate for initiation of anticoagulation but was not reachable. Of the 5 recommendations with no action taken, 4 PCPs acknowledged the alert with no further documentation, and 1 PCP deferred the decision to cardiology with no further documentation. In the VTE cohort, 3 veterans successfully discontinued anticoagulation therapy and 2 veterans were further evaluated by the anticoagulation CPP and deemed appropriate to continue therapy based on potential for malignancy. Of the 2 recommendations with no action taken, 1 anticoagulation CPP acknowledged the alert with no further documentation and 1 anticoagulation CPP suggested further evaluation by PCP with no further documentation.

In the Afib cohort, a nonpharmacologic approach was defined as documentation of a LAAO device. An inaccurate diagnosis was defined as an Afib diagnosis being used in a previous visit, although there was no further confirmation of diagnosis via chart review. Veterans classified as already being on anticoagulation had documentation of non–VA-written anticoagulant prescriptions or receiving a supply of anticoagulants from a facility such as a nursing home. Anticoagulation was defined as unfavorable if a documented risk/benefit conversation was found via EHR review. Anticoagulation was defined as not indicated if the Afib was documented as transient, episodic, or historical (Table 2).

In the VTE cohort, no recommendations for discontinuation were made for veterans indicated to continue anticoagulation due to a concurrent Afib diagnosis. Chronic or recurrent events were defined as documentation of multiple VTE events and associated dates in the EHR. Persistent risk factors included malignancy or medications contributing to hypercoagulable states. Thrombophilia was defined as having documentation of a diagnosis in the EHR. An unprovoked event was defined as VTE without any documented transient risk factors (eg, hospitalization, trauma, surgery, cast immobilization, hormone therapy, pregnancy, or prolonged travel). Anticoagulation had already been discontinued in 1 veteran after the data were collected but before chart review occurred (Table 3).

Discussion

Pharmacy-led indication reviews resulted in appropriate recommendations for anticoagulation use in veterans with Afib and a history of VTE events. Overall, 12.3% of chart reviews in each cohort resulted in a recommendation being made, which was similar to the rate found by Koolian et al.5 In that study, 10% of recommendations were related to initiation or interruption of anticoagulation. This recommendation category consisted of several subcategories, including “suggesting therapeutic anticoagulation when none is currently ordered” and “suggesting anticoagulation cessation if no longer indicated,” but specific numerical prevalence was not provided.5

Online dashboard use allowed for greater population health management and identification of veterans with Afib who were not on active anticoagulation, providing opportunities to prevent stroke-related complications. Wang et al completed a similarly designed study that included a population health tool to identify patients with Afib who were not on anticoagulation and implemented pharmacist-led chart review and facilitation of recommendations to the responsible clinician. This study reviewed 1727 patients and recommended initiation of anticoagulation therapy for 75 (4.3%).6 The current study had a higher percentage of patients with recommendations for changes despite its smaller size.

Evaluating the duration of therapy for anticoagulation in veterans with a history of VTE events provided an opportunity to reduce unnecessary exposure to anticoagulation and minimize bleeding risks. Using a chart review process and standardized note template enabled the documentation of pertinent information that could be readily reviewed by the PCP. This process is a step toward ensuring VAPHCS PCPs provide guideline-recommended care and actively prevent stroke and bleeding complications. Adoption of this process into the current VAPHCS Anticoagulation Clinic workflow for review of veterans with either Afib or VTE could lead to more EHRs being reviewed and recommendations made, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Therapeutic interventions based on the recommendations were completed for 1 of 7 veterans (14%) and 3 of 7 veterans (43%) in the Afib and VTE cohorts, respectively. The prevalence of completed interventions in this anticoagulation stewardship study was higher than those in Wang et al, who found only 9% of their recommendations resulted in PCPs considering action related to anticoagulation, and only 4% were successfully initiated.6

In the Afib cohort, veterans identified by the dashboard with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 7 or 8 were prioritized for review. Reviewing these veterans ensured that patients with the highest stroke risk were sufficiently evaluated and started on anticoagulation as needed to reduce stroke-related complications. In contrast, because these veterans had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores, they may have already been evaluated for anticoagulation in the past and had a documented rationale for not being placed on anticoagulation (LAAO device placement was the most common rationale). Focusing on veterans with a lower CHA2DS2-VASc score such as 1 for men or 2 for women could potentially include more opportunities for recommendations. Although stroke risk may be lower in this population compared with those with higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores, guideline-recommended anticoagulation use may be missed for these patients.

In the VTE cohort, veterans with an anticoagulant prescription written 12 months before data collection were prioritized for review. Reviewing these veterans ensured that anticoagulation therapy met guideline recommendations of at least 3 months, with potential for extended duration upon further evaluation by a provider at that time. Based on collected results, most veterans were already reevaluated and had documented reasons why anticoagulation was still indicated; concurrent Afib was most common followed by chronic or recurrent VTE. Reviewing veterans with more recent prescriptions just over the recommended 3-month duration could potentially include more opportunities for recommendations to be made. It is more likely that by 3 months another PCP had not already weighed in on the duration of therapy, and the anticoagulation CPP could ensure a thorough review is conducted with guideline-based recommendations.

Most published literature on anticoagulation stewardship efforts is focused on inpatient management and policy changes, or concentrate on attributes of therapy such as appropriate dosing and drug interactions. This study highlighted that gaps in care related to anticoagulation use and discontinuation are present in the VAPHCS population and can be appropriately addressed via pharmacist-led indication reviews. Future studies designed to focus on initiating anticoagulation where appropriate, and discontinuing where a sufficient treatment period has been completed, are warranted to minimize this gap in care and allow health systems to work toward process changes to ensure safe and optimized care is provided for the patients they serve.

Limitations

In the Afib cohort, 5 of 7 recommendations (71%) had no further action taken by the PCP, which may represent a barrier to care. In contrast, 2 of 7 recommendations (29%) had no further action in the VTE cohort. It is possible that the difference can be attributed to the anticoagulation CPP receiving VTE alerts and PCPs receiving Afib alerts. The anticoagulation CPP was familiar with this QI study and may have better understood the purpose of the chart review and the need to provide a timely response. PCPs may have been less likely to take action because they were unfamiliar with the anticoagulation stewardship initiative and standardized note template or overwhelmed by too many EHR alerts.

The lack of PCP response to a virtual alert or message also was observed by Wang et al, whereas Koolian et al reported higher intervention completion rates, with verbal recommendations being made to the responsible clinicians. To further ensure these pertinent recommendations for anticoagulation initiation in veterans with Afib are properly reviewed and evaluated, future research could include intentional follow-up with the PCP regarding the alert, PCP-specific education about the anticoagulation stewardship initiative and the role of the standardized note template, and collaboration with PCPs to identify alternative ways to relay recommendations in a way that would ensure the completion of appropriate and timely review.

Conclusions

This study identified gaps in care related to anticoagulation needs in the VAPHCS veteran population. Utilizing a standardized indication review process allows pharmacists to evaluate anticoagulant use for both appropriate indication and duration of therapy. Providing recommendations via chart review notes and alerting respective PCPs and CPPs results in veterans receiving safe and optimized care regarding their anticoagulation needs.

- Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149:e1-e156. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193

- Stevens SM, Woller SC, Kreuziger LB, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021;160:e545-e608. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.055

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). List of high-alert medications in community/ambulatory care settings. ISMP. September 30, 2021. Accessed September 11, 2025. https://home.ecri.org/blogs/ismp-resources/high-alert-medications-in-community-ambulatory-care-settings

- Burnett AE, Barnes GD. A call to action for anticoagulation stewardship. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;6:e12757. doi:10.1002/rth2.12757

- Koolian M, Wiseman D, Mantzanis H, et al. Anticoagulation stewardship: descriptive analysis of a novel approach to appropriate anticoagulant prescription. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;6:e12758. doi:10.1002/rth2.12758

- Wang SV, Rogers JR, Jin Y, et al. Stepped-wedge randomised trial to evaluate population health intervention designed to increase appropriate anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:835-842. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009367

- Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, et al. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149:e1-e156. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001193

- Stevens SM, Woller SC, Kreuziger LB, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021;160:e545-e608. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.055

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). List of high-alert medications in community/ambulatory care settings. ISMP. September 30, 2021. Accessed September 11, 2025. https://home.ecri.org/blogs/ismp-resources/high-alert-medications-in-community-ambulatory-care-settings

- Burnett AE, Barnes GD. A call to action for anticoagulation stewardship. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;6:e12757. doi:10.1002/rth2.12757

- Koolian M, Wiseman D, Mantzanis H, et al. Anticoagulation stewardship: descriptive analysis of a novel approach to appropriate anticoagulant prescription. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2022;6:e12758. doi:10.1002/rth2.12758

- Wang SV, Rogers JR, Jin Y, et al. Stepped-wedge randomised trial to evaluate population health intervention designed to increase appropriate anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:835-842. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009367

Anticoagulation Stewardship Efforts Via Indication Reviews at a Veterans Affairs Health Care System

Anticoagulation Stewardship Efforts Via Indication Reviews at a Veterans Affairs Health Care System

Targeted Syncope Workup in Hypercoagulable Patients

Background

Syncope presents a common diagnostic challenge due to its broad differential, ranging from benign to life-threatening conditions. Despite guidelines emphasizing a history- and physical examination- driven approach, nearly $33 billion is spent annually on syncope evaluations, often without yielding conclusive diagnoses. Here, we present a case of syncope secondary to cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, underscoring the importance of cerebrovascular imaging in select high-risk patient populations.

Case Presentation

An 80-year-old male with chronic sinusitis and history of pulmonary embolism (managed with thrombolysis and apixaban) presented due to an episode of transient loss of consciousness followed by nausea and vomiting. He denied any preceding symptoms but his wife did notice his arm move up for a few seconds. He didn’t have any headaches or post-ictal state. Physical exam showed normal orthostatic vital signs, symmetric blood pressure and radial pulses bilaterally. An extensive neurological exam was done and was unremarkable for any focal deficits including no vision changes. Initial evaluation including electrocardiogram, telemetry monitoring, transthoracic echocardiogram, and electroencephalography showed no significant abnormalities.

Chest CT angiography revealed right-sided segmental pulmonary emboli, unchanged from prior imaging. Head CT did not show any acute intracranial findings, and CT angiography demonstrated no vascular abnormality. Ultimately, an MRI brain revealed a left sigmoid sinus filling defect, suggestive of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), in addition to chronic sinusitis. As CVST occurred while on apixaban, anticoagulation was switched to enoxaparin. He did not experience any recurrent symptoms during admission.

Conclusions

This case highlights the need for a patient- specific approach to syncope evaluation. Early neurovascular imaging may aid in prompt diagnosis and prevent unnecessary testing. CVST is a rare manifestation of venous thromboembolism and may present with symptoms mimicking vasovagal syncope, such as nausea and transient loss of consciousness. Typical symptoms of CVST include headaches, vomiting, vision changes, focal deficits, seizures, mental status changes, stupor or coma. Risk factors include prior thrombosis, hypercoagulable states like pregnancy or malignancy, obesity, OCPs, and chronic sinusitis. Noncontrast CT may miss CVST, and advanced neuroimaging is necessary for diagnosis in high-risk patients with thrombotic risk factors or symptoms suggestive of elevated intracranial pressure.

Background

Syncope presents a common diagnostic challenge due to its broad differential, ranging from benign to life-threatening conditions. Despite guidelines emphasizing a history- and physical examination- driven approach, nearly $33 billion is spent annually on syncope evaluations, often without yielding conclusive diagnoses. Here, we present a case of syncope secondary to cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, underscoring the importance of cerebrovascular imaging in select high-risk patient populations.

Case Presentation

An 80-year-old male with chronic sinusitis and history of pulmonary embolism (managed with thrombolysis and apixaban) presented due to an episode of transient loss of consciousness followed by nausea and vomiting. He denied any preceding symptoms but his wife did notice his arm move up for a few seconds. He didn’t have any headaches or post-ictal state. Physical exam showed normal orthostatic vital signs, symmetric blood pressure and radial pulses bilaterally. An extensive neurological exam was done and was unremarkable for any focal deficits including no vision changes. Initial evaluation including electrocardiogram, telemetry monitoring, transthoracic echocardiogram, and electroencephalography showed no significant abnormalities.

Chest CT angiography revealed right-sided segmental pulmonary emboli, unchanged from prior imaging. Head CT did not show any acute intracranial findings, and CT angiography demonstrated no vascular abnormality. Ultimately, an MRI brain revealed a left sigmoid sinus filling defect, suggestive of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), in addition to chronic sinusitis. As CVST occurred while on apixaban, anticoagulation was switched to enoxaparin. He did not experience any recurrent symptoms during admission.

Conclusions

This case highlights the need for a patient- specific approach to syncope evaluation. Early neurovascular imaging may aid in prompt diagnosis and prevent unnecessary testing. CVST is a rare manifestation of venous thromboembolism and may present with symptoms mimicking vasovagal syncope, such as nausea and transient loss of consciousness. Typical symptoms of CVST include headaches, vomiting, vision changes, focal deficits, seizures, mental status changes, stupor or coma. Risk factors include prior thrombosis, hypercoagulable states like pregnancy or malignancy, obesity, OCPs, and chronic sinusitis. Noncontrast CT may miss CVST, and advanced neuroimaging is necessary for diagnosis in high-risk patients with thrombotic risk factors or symptoms suggestive of elevated intracranial pressure.

Background

Syncope presents a common diagnostic challenge due to its broad differential, ranging from benign to life-threatening conditions. Despite guidelines emphasizing a history- and physical examination- driven approach, nearly $33 billion is spent annually on syncope evaluations, often without yielding conclusive diagnoses. Here, we present a case of syncope secondary to cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, underscoring the importance of cerebrovascular imaging in select high-risk patient populations.

Case Presentation

An 80-year-old male with chronic sinusitis and history of pulmonary embolism (managed with thrombolysis and apixaban) presented due to an episode of transient loss of consciousness followed by nausea and vomiting. He denied any preceding symptoms but his wife did notice his arm move up for a few seconds. He didn’t have any headaches or post-ictal state. Physical exam showed normal orthostatic vital signs, symmetric blood pressure and radial pulses bilaterally. An extensive neurological exam was done and was unremarkable for any focal deficits including no vision changes. Initial evaluation including electrocardiogram, telemetry monitoring, transthoracic echocardiogram, and electroencephalography showed no significant abnormalities.

Chest CT angiography revealed right-sided segmental pulmonary emboli, unchanged from prior imaging. Head CT did not show any acute intracranial findings, and CT angiography demonstrated no vascular abnormality. Ultimately, an MRI brain revealed a left sigmoid sinus filling defect, suggestive of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), in addition to chronic sinusitis. As CVST occurred while on apixaban, anticoagulation was switched to enoxaparin. He did not experience any recurrent symptoms during admission.

Conclusions

This case highlights the need for a patient- specific approach to syncope evaluation. Early neurovascular imaging may aid in prompt diagnosis and prevent unnecessary testing. CVST is a rare manifestation of venous thromboembolism and may present with symptoms mimicking vasovagal syncope, such as nausea and transient loss of consciousness. Typical symptoms of CVST include headaches, vomiting, vision changes, focal deficits, seizures, mental status changes, stupor or coma. Risk factors include prior thrombosis, hypercoagulable states like pregnancy or malignancy, obesity, OCPs, and chronic sinusitis. Noncontrast CT may miss CVST, and advanced neuroimaging is necessary for diagnosis in high-risk patients with thrombotic risk factors or symptoms suggestive of elevated intracranial pressure.

Cardiac Risks of Newer Psoriasis Biologics vs. TNF Inhibitors Compared

TOPLINE:

The newer biologics — .

METHODOLOGY:

- In a retrospective cohort study, researchers conducted an emulated target trial analysis using data of 32,098 biologic-naive patients with psoriasis or PsA who were treated with one of the newer biologics (infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, certolizumab pegol, secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, ustekinumab, risankizumab, guselkumab, and tildrakizumab) from the TriNetX Research Network between 2014 and 2022.

- Patients received TNF inhibitors (n = 20,314), IL-17 inhibitors (n = 5073), IL-12/23 inhibitors (n = 3573), or IL-23 inhibitors (n = 3138).

- A propensity-matched analysis compared each class of newer biologics with TNF inhibitors, adjusting for demographics, comorbidities, and medication use.

- The primary outcomes were major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; myocardial infarction and stroke) or venous thromboembolic events (VTE).

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with patients who received TNF inhibitors, the risk for MACE was not significantly different between patients who received IL-17 inhibitors (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.14; 95% CI, 0.86-1.52), IL-12/23 inhibitors (IRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.84-1.78), or IL-23 inhibitors (IRR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.61-1.38)

- The VTE risk was also not significantly different between patients who received IL-17 inhibitors (IRR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.63-2.08), IL-12/23 inhibitors (IRR, 1.51; 95% CI, 0.73-3.19), or IL-23 inhibitors (IRR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.64-3.25) compared with those who received TNF inhibitors.

- Subgroup analyses for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis alone confirmed consistent findings.

- Patients with preexisting hyperlipidemia and diabetes mellitus showed lower risks for MACE and VTE with newer biologics compared with TNF inhibitors.

IN PRACTICE:

“No significant MACE and VTE risk differences were detected in patients with psoriasis or PsA between those receiving IL-17, IL-12/23, and IL-23 inhibitors and those with TNF inhibitors,” the authors concluded. These findings, they added “can be considered by physicians and patients when making treatment decisions” and also provide “evidence for future pharmacovigilance studies.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Tai-Li Chen, MD, of the Department of Dermatology, Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan. It was published online on December 27, 2024, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Study limitations included potential residual confounding factors, lack of information on disease severity, and inclusion of predominantly White individuals.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The newer biologics — .

METHODOLOGY:

- In a retrospective cohort study, researchers conducted an emulated target trial analysis using data of 32,098 biologic-naive patients with psoriasis or PsA who were treated with one of the newer biologics (infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, certolizumab pegol, secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, ustekinumab, risankizumab, guselkumab, and tildrakizumab) from the TriNetX Research Network between 2014 and 2022.

- Patients received TNF inhibitors (n = 20,314), IL-17 inhibitors (n = 5073), IL-12/23 inhibitors (n = 3573), or IL-23 inhibitors (n = 3138).

- A propensity-matched analysis compared each class of newer biologics with TNF inhibitors, adjusting for demographics, comorbidities, and medication use.

- The primary outcomes were major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; myocardial infarction and stroke) or venous thromboembolic events (VTE).

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with patients who received TNF inhibitors, the risk for MACE was not significantly different between patients who received IL-17 inhibitors (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.14; 95% CI, 0.86-1.52), IL-12/23 inhibitors (IRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.84-1.78), or IL-23 inhibitors (IRR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.61-1.38)

- The VTE risk was also not significantly different between patients who received IL-17 inhibitors (IRR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.63-2.08), IL-12/23 inhibitors (IRR, 1.51; 95% CI, 0.73-3.19), or IL-23 inhibitors (IRR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.64-3.25) compared with those who received TNF inhibitors.

- Subgroup analyses for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis alone confirmed consistent findings.

- Patients with preexisting hyperlipidemia and diabetes mellitus showed lower risks for MACE and VTE with newer biologics compared with TNF inhibitors.

IN PRACTICE:

“No significant MACE and VTE risk differences were detected in patients with psoriasis or PsA between those receiving IL-17, IL-12/23, and IL-23 inhibitors and those with TNF inhibitors,” the authors concluded. These findings, they added “can be considered by physicians and patients when making treatment decisions” and also provide “evidence for future pharmacovigilance studies.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Tai-Li Chen, MD, of the Department of Dermatology, Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan. It was published online on December 27, 2024, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Study limitations included potential residual confounding factors, lack of information on disease severity, and inclusion of predominantly White individuals.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The newer biologics — .

METHODOLOGY:

- In a retrospective cohort study, researchers conducted an emulated target trial analysis using data of 32,098 biologic-naive patients with psoriasis or PsA who were treated with one of the newer biologics (infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, certolizumab pegol, secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, ustekinumab, risankizumab, guselkumab, and tildrakizumab) from the TriNetX Research Network between 2014 and 2022.

- Patients received TNF inhibitors (n = 20,314), IL-17 inhibitors (n = 5073), IL-12/23 inhibitors (n = 3573), or IL-23 inhibitors (n = 3138).

- A propensity-matched analysis compared each class of newer biologics with TNF inhibitors, adjusting for demographics, comorbidities, and medication use.

- The primary outcomes were major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; myocardial infarction and stroke) or venous thromboembolic events (VTE).

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with patients who received TNF inhibitors, the risk for MACE was not significantly different between patients who received IL-17 inhibitors (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.14; 95% CI, 0.86-1.52), IL-12/23 inhibitors (IRR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.84-1.78), or IL-23 inhibitors (IRR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.61-1.38)

- The VTE risk was also not significantly different between patients who received IL-17 inhibitors (IRR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.63-2.08), IL-12/23 inhibitors (IRR, 1.51; 95% CI, 0.73-3.19), or IL-23 inhibitors (IRR, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.64-3.25) compared with those who received TNF inhibitors.

- Subgroup analyses for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis alone confirmed consistent findings.

- Patients with preexisting hyperlipidemia and diabetes mellitus showed lower risks for MACE and VTE with newer biologics compared with TNF inhibitors.

IN PRACTICE:

“No significant MACE and VTE risk differences were detected in patients with psoriasis or PsA between those receiving IL-17, IL-12/23, and IL-23 inhibitors and those with TNF inhibitors,” the authors concluded. These findings, they added “can be considered by physicians and patients when making treatment decisions” and also provide “evidence for future pharmacovigilance studies.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Tai-Li Chen, MD, of the Department of Dermatology, Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan. It was published online on December 27, 2024, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Study limitations included potential residual confounding factors, lack of information on disease severity, and inclusion of predominantly White individuals.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New Investigation Casts Doubt on Landmark Ticagrelor Trial

New questions about the landmark trial that launched the antiplatelet drug ticagrelor worldwide are being raised after an investigation uncovered more information about how the PLATO study was conducted.

Peter Doshi, PhD, senior editor at The BMJ, obtained primary records for the trial and unpublished data through a Freedom of Information Act request, and has detailed inconsistencies and omissions in data reporting from the 2009 trial originally published in The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). The new investigation into the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial is published in The BMJ.

The findings come as generic versions of ticagrelor (Brilinta) are expected to become available soon in the United States. Ticagrelor is the only P2Y12 inhibitor still under patent, and in 2022, the United States spent more than $750 million on it, according to the report.

PLATO, sponsored by ticagrelor manufacturer AstraZeneca, included more than 18,000 patients in 43 countries. Investigators reported that ticagrelor reduced deaths from vascular causes, heart attack, or stroke compared with clopidogrel (Plavix). However, in a subgroup analysis, among US patients, there were more deaths in the ticagrelor group, and AstraZeneca failed its first bid for approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Failed First Bid for FDA Approval

AstraZeneca resubmitted its application, which was met with objections by some FDA staff members, including medical officer Thomas Marciniak, who called the resubmission “the worst in my experience regarding completeness of the submissions and the sponsor responding completely and accurately to requests,” Doshi reports.

Despite the objections, the FDA in 2011 approved ticagrelor for acute coronary syndrome, kicking off intense controversy over the trial, as several other studies have failed to replicate PLATO’s positive results.

Doubts have grown about its apparent advantage over cheaper, off-patent P2Y12 inhibitors such as clopidogrel and prasugrel.

“Critics said it was noteworthy that ticagrelor failed in the US,” Doshi writes, “the only high enrolling country where sites were not monitored by the sponsor itself.” Doshi’s report points out that critics of the trial “highlight that AstraZeneca itself carried out the data monitoring for PLATO except for sites that were monitored by third party contract research organizations. In the four countries exclusively monitored by non-sponsor personnel—Georgia, Israel, Russia, and the US—ticagrelor fared worse.”

Victor Serebruany, MD, from Johns Hopkins University, said he was initially impressed by the trial results but became skeptical after noticing inconsistencies and anomalies in the data. He filed a complaint with the US District Court in the District of Columbia, suggesting that the cardiovascular events in the study “may have been manipulated.”

US Department of Justice Investigation

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) opened an investigation in 2013 and closed it in 2014 with no further action. Serebruany continues to publish critiques of the trial 15 years later but told The BMJ he has little hope that the questions will be resolved unless the DOJ re-engages with an investigation.

Doshi also points out discrepancies in the data reported. In the 2009 paper, published as an intent-to-treat analysis, investigators said there were 905 total deaths from any cause among all randomized patients. “An internal company report states, however, that 983 patients had died at this point. While 33 deaths occurred after the follow-up period, the NEJM tally still leaves out 45 deaths ‘discovered after withdrawal of consent,’” he reports.

The NEJM responded to Doshi that while it didn’t dispute the error in the number of deaths, it was uncertain about publishing a correction, citing new — not yet published — guidelines from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. NEJM Editor-in-Chief Eric Rubin told The BMJ that “for older manuscripts, correction is not necessarily appropriate unless there would be an effect on clinical practice.”

Doshi’s investigation includes an interview with Eric Bates, MD, professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and a co-author of the US guidelines that recommend ticagrelor, who said he was “increasingly disturbed by how trial after trial came out as being not dramatically positive in any way.” Bates is now calling for a review of ticagrelor’s recommendation in guidelines, according to the report.

AstraZeneca declined to be interviewed for the BMJ investigation, according to Doshi, and a spokesperson from the company told the journal by email that they have “nothing to add,” directing editors to its 2014 public statement after the DOJ’s investigation into PLATO. The BMJ said PLATO trial co-chairs Robert A. Harrington, MD, and Lars Wallentin, MD, did not respond to The BMJ’s requests for comment.

Will the Guidelines Be Changed Now?