User login

Dying in the Hospital: A Necessary Choice?

More than a third of all patients with cancer die in hospitals, a figure that has increased slightly in recent years, while deaths at home have decreased. These findings come from a recent study published in Cancer Epidemiology, which analyzed data on the different places in Italy where end of life occurs.

“Place of death is relevant both for individuals and for the society. Home is universally considered the optimal place of death, while dying in a hospital may be a signal of inappropriate end-of-life care,” wrote the authors, led by Gianmauro Numico, MD, head of the Oncology Department at the Santa Croce e Carle General Hospital in Cuneo, Italy.

“Despite the general trend toward strengthening community-based networks and the increasing number of hospice and long-term care facilities, we oncologists are facing an opposite trend, with many patients spending their last days in the hospital,” Numico explained to Univadis Italy. This observation led to the questions that prompted the study: Is this only a perception among doctors, or is it a real phenomenon? If the latter, why is it happening?

What’s Preferable

For their analysis, Numico and colleagues relied on death certificates published by the Italian National Institute of Statistics from 2015 to 2019, excluding data from the pandemic years to avoid potential biases.

The analysis of data pertaining to cancer deaths revealed that approximately 35% of Italian patients with cancer die in hospitals, with a slight increase over the study period. Of the patients who die elsewhere, 40% die at home and 20% die in hospice or other long-term care facilities. Home deaths have decreased by 3.09%, while those in hospices and long-term care facilities have increased by 2.71%, and hospital deaths have risen by 0.3%.

The study also highlighted notable geographical differences: Hospital deaths are more frequent in the north, while in the south, home deaths remain predominant, although hospital admissions are on the rise. “These differences reflect not only access to facilities but also cultural and social variables,” explained Numico. “Some end-of-life issues with cancer patients are more straightforward, while others are difficult to manage outside the hospital,” he said, recalling that many family members and caregivers are afraid they won’t be able to care for their loved ones properly without the support of an appropriate facility and skilled personnel.

Social factors also contribute to the increased use of hospitals for end-of-life care: Without a social and family network, it is often impossible to manage the final stages of life at home. “We cannot guarantee that dying at home is better for everyone; in some cases, the home cannot provide the necessary care and emotional support,” Numico added.

Attitudes Need Change

Looking beyond Italy, it is clear that this trend exists in other countries as well. For example, in the Netherlands — where community-based care is highly developed and includes practices such as euthanasia — hospital death rates are higher than those in Italy. In the United States, the trend is different, but this is largely due to the structure of the US healthcare system, where patients bear much of the financial burden of hospital admissions.

“The basic requests of patients and families are clear: They want a safe place that is adequately staffed and where the patient won’t suffer,” said Numico, questioning whether the home is truly the best place to die. “In reality, this is not always the case, and it’s important to focus on the quality of care in the final days rather than just the place of care,” he added.

Ruling out hospitals a priori as a place to die is not a winning strategy, according to the expert. Instead of trying to reverse the trend, he suggests integrating the hospital into a care network that prioritizes the patient’s well-being, regardless of the setting. “Our goal should not be to eliminate hospital deaths — a common request from hospital administrations — but rather to ensure that end-of-life care in hospitals is a dignified experience that respects the needs of the dying and their loved ones,” Numico said. “We must ensure that, wherever the end-of-life process occurs, it should happen in the best way possible, and the hospital must be a part of this overall framework,” he concluded.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

More than a third of all patients with cancer die in hospitals, a figure that has increased slightly in recent years, while deaths at home have decreased. These findings come from a recent study published in Cancer Epidemiology, which analyzed data on the different places in Italy where end of life occurs.

“Place of death is relevant both for individuals and for the society. Home is universally considered the optimal place of death, while dying in a hospital may be a signal of inappropriate end-of-life care,” wrote the authors, led by Gianmauro Numico, MD, head of the Oncology Department at the Santa Croce e Carle General Hospital in Cuneo, Italy.

“Despite the general trend toward strengthening community-based networks and the increasing number of hospice and long-term care facilities, we oncologists are facing an opposite trend, with many patients spending their last days in the hospital,” Numico explained to Univadis Italy. This observation led to the questions that prompted the study: Is this only a perception among doctors, or is it a real phenomenon? If the latter, why is it happening?

What’s Preferable

For their analysis, Numico and colleagues relied on death certificates published by the Italian National Institute of Statistics from 2015 to 2019, excluding data from the pandemic years to avoid potential biases.

The analysis of data pertaining to cancer deaths revealed that approximately 35% of Italian patients with cancer die in hospitals, with a slight increase over the study period. Of the patients who die elsewhere, 40% die at home and 20% die in hospice or other long-term care facilities. Home deaths have decreased by 3.09%, while those in hospices and long-term care facilities have increased by 2.71%, and hospital deaths have risen by 0.3%.

The study also highlighted notable geographical differences: Hospital deaths are more frequent in the north, while in the south, home deaths remain predominant, although hospital admissions are on the rise. “These differences reflect not only access to facilities but also cultural and social variables,” explained Numico. “Some end-of-life issues with cancer patients are more straightforward, while others are difficult to manage outside the hospital,” he said, recalling that many family members and caregivers are afraid they won’t be able to care for their loved ones properly without the support of an appropriate facility and skilled personnel.

Social factors also contribute to the increased use of hospitals for end-of-life care: Without a social and family network, it is often impossible to manage the final stages of life at home. “We cannot guarantee that dying at home is better for everyone; in some cases, the home cannot provide the necessary care and emotional support,” Numico added.

Attitudes Need Change

Looking beyond Italy, it is clear that this trend exists in other countries as well. For example, in the Netherlands — where community-based care is highly developed and includes practices such as euthanasia — hospital death rates are higher than those in Italy. In the United States, the trend is different, but this is largely due to the structure of the US healthcare system, where patients bear much of the financial burden of hospital admissions.

“The basic requests of patients and families are clear: They want a safe place that is adequately staffed and where the patient won’t suffer,” said Numico, questioning whether the home is truly the best place to die. “In reality, this is not always the case, and it’s important to focus on the quality of care in the final days rather than just the place of care,” he added.

Ruling out hospitals a priori as a place to die is not a winning strategy, according to the expert. Instead of trying to reverse the trend, he suggests integrating the hospital into a care network that prioritizes the patient’s well-being, regardless of the setting. “Our goal should not be to eliminate hospital deaths — a common request from hospital administrations — but rather to ensure that end-of-life care in hospitals is a dignified experience that respects the needs of the dying and their loved ones,” Numico said. “We must ensure that, wherever the end-of-life process occurs, it should happen in the best way possible, and the hospital must be a part of this overall framework,” he concluded.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

More than a third of all patients with cancer die in hospitals, a figure that has increased slightly in recent years, while deaths at home have decreased. These findings come from a recent study published in Cancer Epidemiology, which analyzed data on the different places in Italy where end of life occurs.

“Place of death is relevant both for individuals and for the society. Home is universally considered the optimal place of death, while dying in a hospital may be a signal of inappropriate end-of-life care,” wrote the authors, led by Gianmauro Numico, MD, head of the Oncology Department at the Santa Croce e Carle General Hospital in Cuneo, Italy.

“Despite the general trend toward strengthening community-based networks and the increasing number of hospice and long-term care facilities, we oncologists are facing an opposite trend, with many patients spending their last days in the hospital,” Numico explained to Univadis Italy. This observation led to the questions that prompted the study: Is this only a perception among doctors, or is it a real phenomenon? If the latter, why is it happening?

What’s Preferable

For their analysis, Numico and colleagues relied on death certificates published by the Italian National Institute of Statistics from 2015 to 2019, excluding data from the pandemic years to avoid potential biases.

The analysis of data pertaining to cancer deaths revealed that approximately 35% of Italian patients with cancer die in hospitals, with a slight increase over the study period. Of the patients who die elsewhere, 40% die at home and 20% die in hospice or other long-term care facilities. Home deaths have decreased by 3.09%, while those in hospices and long-term care facilities have increased by 2.71%, and hospital deaths have risen by 0.3%.

The study also highlighted notable geographical differences: Hospital deaths are more frequent in the north, while in the south, home deaths remain predominant, although hospital admissions are on the rise. “These differences reflect not only access to facilities but also cultural and social variables,” explained Numico. “Some end-of-life issues with cancer patients are more straightforward, while others are difficult to manage outside the hospital,” he said, recalling that many family members and caregivers are afraid they won’t be able to care for their loved ones properly without the support of an appropriate facility and skilled personnel.

Social factors also contribute to the increased use of hospitals for end-of-life care: Without a social and family network, it is often impossible to manage the final stages of life at home. “We cannot guarantee that dying at home is better for everyone; in some cases, the home cannot provide the necessary care and emotional support,” Numico added.

Attitudes Need Change

Looking beyond Italy, it is clear that this trend exists in other countries as well. For example, in the Netherlands — where community-based care is highly developed and includes practices such as euthanasia — hospital death rates are higher than those in Italy. In the United States, the trend is different, but this is largely due to the structure of the US healthcare system, where patients bear much of the financial burden of hospital admissions.

“The basic requests of patients and families are clear: They want a safe place that is adequately staffed and where the patient won’t suffer,” said Numico, questioning whether the home is truly the best place to die. “In reality, this is not always the case, and it’s important to focus on the quality of care in the final days rather than just the place of care,” he added.

Ruling out hospitals a priori as a place to die is not a winning strategy, according to the expert. Instead of trying to reverse the trend, he suggests integrating the hospital into a care network that prioritizes the patient’s well-being, regardless of the setting. “Our goal should not be to eliminate hospital deaths — a common request from hospital administrations — but rather to ensure that end-of-life care in hospitals is a dignified experience that respects the needs of the dying and their loved ones,” Numico said. “We must ensure that, wherever the end-of-life process occurs, it should happen in the best way possible, and the hospital must be a part of this overall framework,” he concluded.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Patient and Support Person Satisfaction Following a Whole Health-Informed Interdisciplinary Pain Team Meeting

Patient and Support Person Satisfaction Following a Whole Health-Informed Interdisciplinary Pain Team Meeting

Chronic pain is one of the most prevalent public health concerns in the United States, affecting > 51 million adults with about $500 billion in health care costs.1 Military veterans are among the most vulnerable subpopulations, with 65% of veterans reporting chronic pain in the last 3 months.2 Chronic pain is complex, affecting the biopsychosocial-spiritual levels of human health, and requires multimodal and comprehensive treatment approaches.3 Hence, chronic pain treatment can be best delivered via interdisciplinary teams (IDTs) that use a patient-centered approach.4,5

The Veterans Healthcare Administration (VHA) is a leader in developing and delivering interdisciplinary pain care.6,7 VHA Directive 2009-053 requires every US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center to offer an IDT for chronic pain. However, VHA and non-VHA IDT programs vary significantly.8-11 A recent systematic review found a median of 5 disciplines included on IDTs (range, 2-8), and program content often included exercise and education; only 11% of included IDTs met simultaneously with patients.11 The heterogeneity of IDT programs has made determining best practices challenging.8,11 The Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials has denoted several core measures and measurement domains that were critical for determining the success of pain management interventions, including patient satisfaction.12,13 Nevertheless, the association of IDTs with high patient satisfaction and improvement in pain measures has been documented.5,11

The VHA has worked to implement the Whole Health System into health care, which considers well-being across physical, behavioral, spiritual, and socioeconomic domains. As such, the Whole Health System involves an interpersonal, team-based approach, “anchored in trusting longitudinal relationships to promote resilience, prevent disease, and restore health.”14 It aligns with the patient’s mission, aspiration, and purpose. Surgeon General VADM Vivek H. Murthy, MD, MBA, recently endorsed this approach.15,16 Other health care systems adopting whole health tend to have higher patient satisfaction, increased access to care, and improved patient-reported outcomes.15 Within the VHA, the Whole Health System has shifted the conversation between clinicians and patients from “What is the matter with you?” to “What is important to you?” while emphasizing a proactive and personalized approach to health care.17 Rather than emphasizing passive modalities such as medications and clinician-led services (eg, interventional pain service), the Whole Health System highlights self-care.3,17 Initial research findings within the VHA have been promising.18-21 Whole health peer coaching calls appear to be an effective approach for veterans diagnosed with PTSD, and the use of whole health services is associated with a decrease in opioid use.19,22 However, there are negligible data on patient experiences after meeting with a whole health-focused pain IDT, and studies to date have focused on urban populations.23 One approach to IDT that has shown promise for other health issues involves a patient meeting simultaneously with all members of the IDT.24-27 With the integration of the Whole Health System and the VHA priorities to provide veterans with the “soonest and best care,” more data are needed on the experiences of patients and support persons with various approaches to IDT pain care.28 This study aimed to evaluate patient and support person experiences with a whole health-focused pain IDT that met simultaneously with the patient and support person during an initial evaluation. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the Salem VA Health Care System (SVAHCS) in Virginia.

Methods

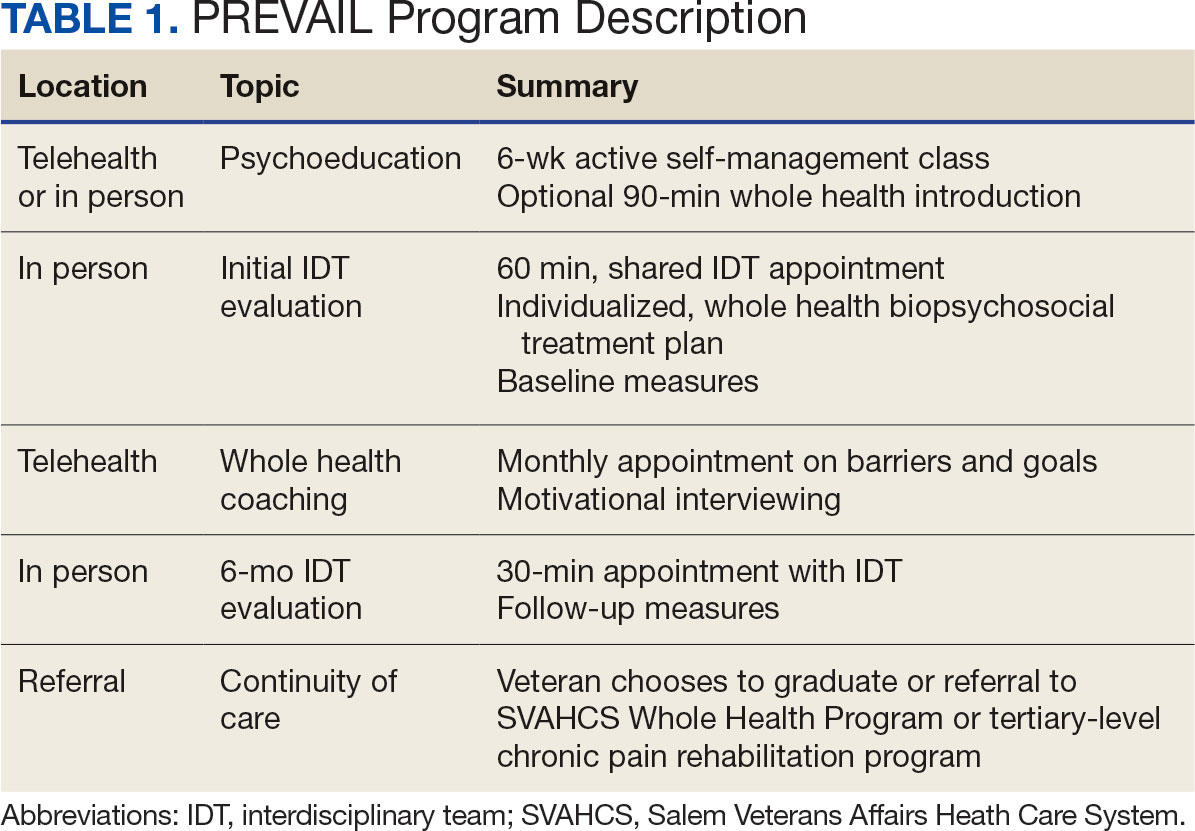

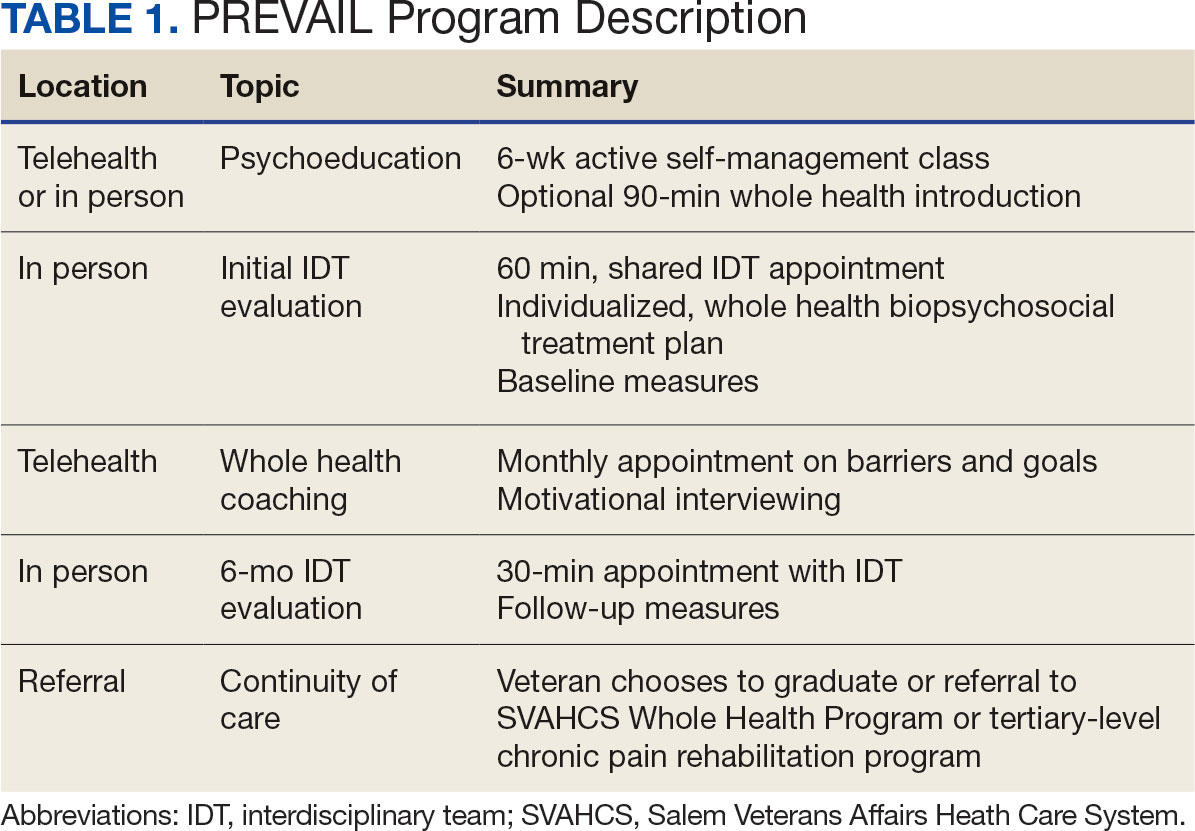

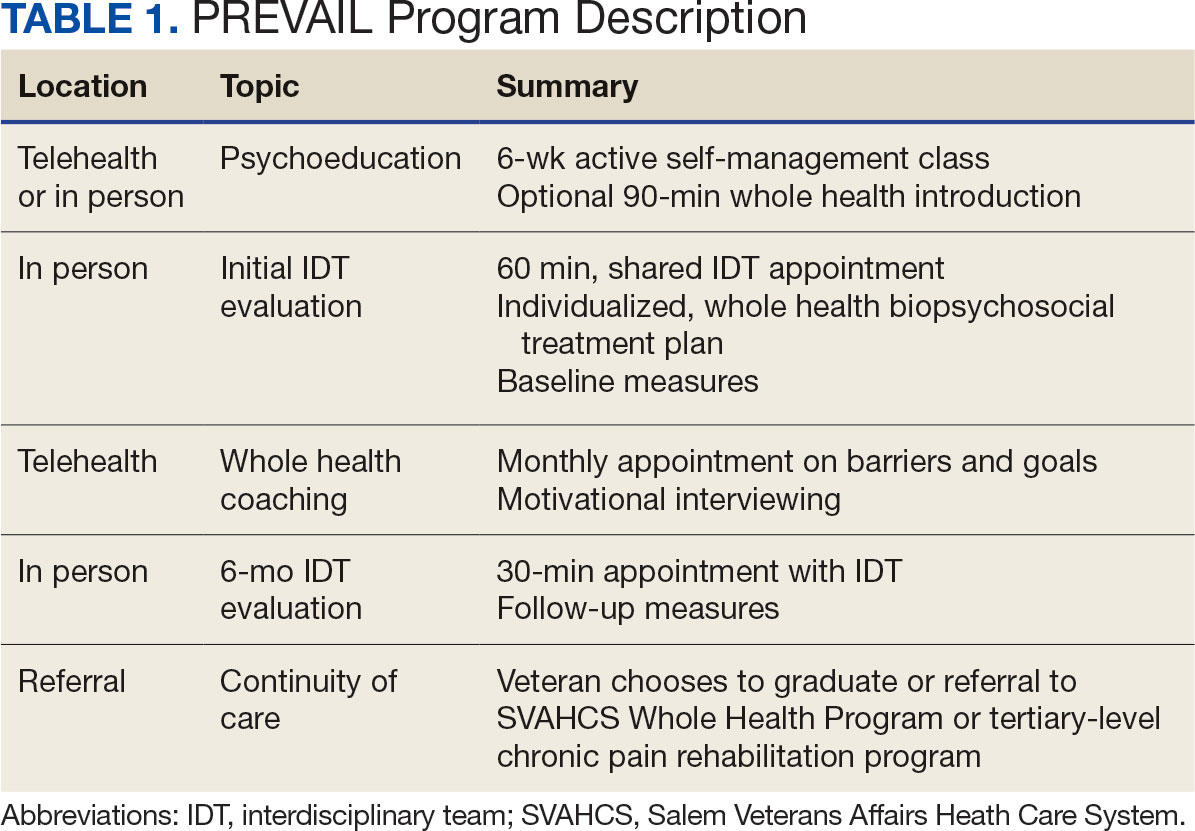

The PREVAIL IDT Track is a clinical program offered at SVAHCS with a whole health-focused approach that involves patients and their support persons meeting simultaneously with a pain IDT. PREVAIL IDT Track is designed to help veterans more effectively self-manage chronic pain (Table 1).6,29 Health care practitioners (HCPs) at SVAHCS recommended that veterans with pain persisting for > 3 months participate in PREVAIL IDT Track. After meeting with an advanced practice clinician for an intake, veterans elected to participate in the PREVAIL IDT Track program and completed the initial 6 weeks of pain education. Veterans were then invited to be evaluated by the pain IDT. A team including HCPs from interventional pain, psychology, pharmacy, nutrition, and physical therapy services met with the veteran for 60 minutes. Veterans were also invited to bring a support person to the IDT initial evaluation.

During the IDT initial evaluation, HCPs inquired about the patient’s mission, aspiration, and purpose (“If you were in less pain, what would you be doing more of?”) and about whole health self-care and wellness factors that may contribute to their chronic pain using the Personal Health Inventory.30,31 Veterans were then invited to select 3 whole health self-care areas to focus on during the 6-month program.3 The IDT HCPs worked with the veteran to establish the treatment plan for the first month in the areas of self-care selected by the patient and made recommendations for additional treatments. If the veteran brought a support person to the IDT initial evaluation, their feedback was elicited throughout and at the end to ensure the final treatment plan and first month’s goals were realistic. At the end of the appointment, the veteran and their support person were asked to complete a program-specific satisfaction survey. The HCPs on the team and the veteran executed the treatment plan developed during the appointment, except for medication prescribing. Recommendations for medication changes are included in clinical notes. Veterans then received 5 monthly coaching calls from a nurse navigator with training in whole health and a 6-month follow-up appointment with the IDT HCPs to discuss a plan for continuity of care.

Participant demographic information was not collected, and participants were not compensated for completing the survey. Veterans in PREVAIL IDT Track are predominantly residents of central Appalachia, White, male, unemployed, have ≥ 1 mental and physical health comorbidity, and have a history of mental health treatment.32 Veterans participating in PREVAIL IDT had a mean age of 57 years, and about 1 in 3 have opioid prescriptions.32

A program-specific 17-question satisfaction survey was developed, which included questions related to satisfaction with previous SVAHCS pain care and staff interactions. To assess the overall impression of the IDT initial evaluation, 3 yes/no questions and a 0 to 10-point scale were used. The 5 remaining open-ended questions allowed participants to give feedback about the IDT initial evaluation.

Data Analysis

A convergent mixed-methods approach was used to evaluate participant satisfaction with the initial IDT evaluation. The study team collected and analyzed quantitative and qualitative survey data and triangulated the findings.33 For quantitative responses, frequencies and means were calculated using Python. For qualitative responses, thematic data analysis was conducted by systematic coding, using inductive methods and allowing themes to emerge. Study team members performed a line-by-line analysis of responses using NVivo to identify important codes and reach a consensus. This study adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research and followed the National Institute for Health Care Excellence checklist.34,35

Results

Quantitative Responses

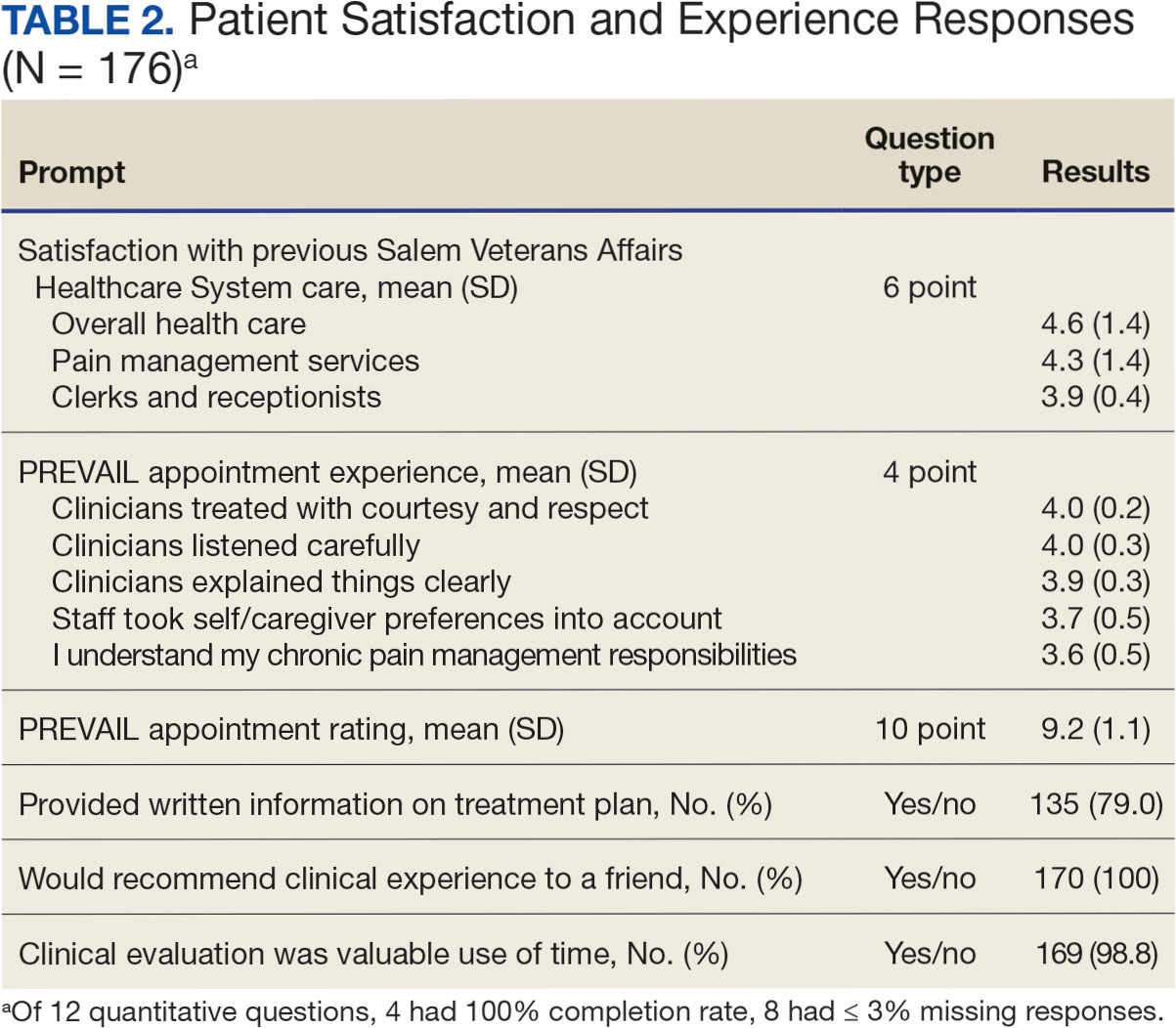

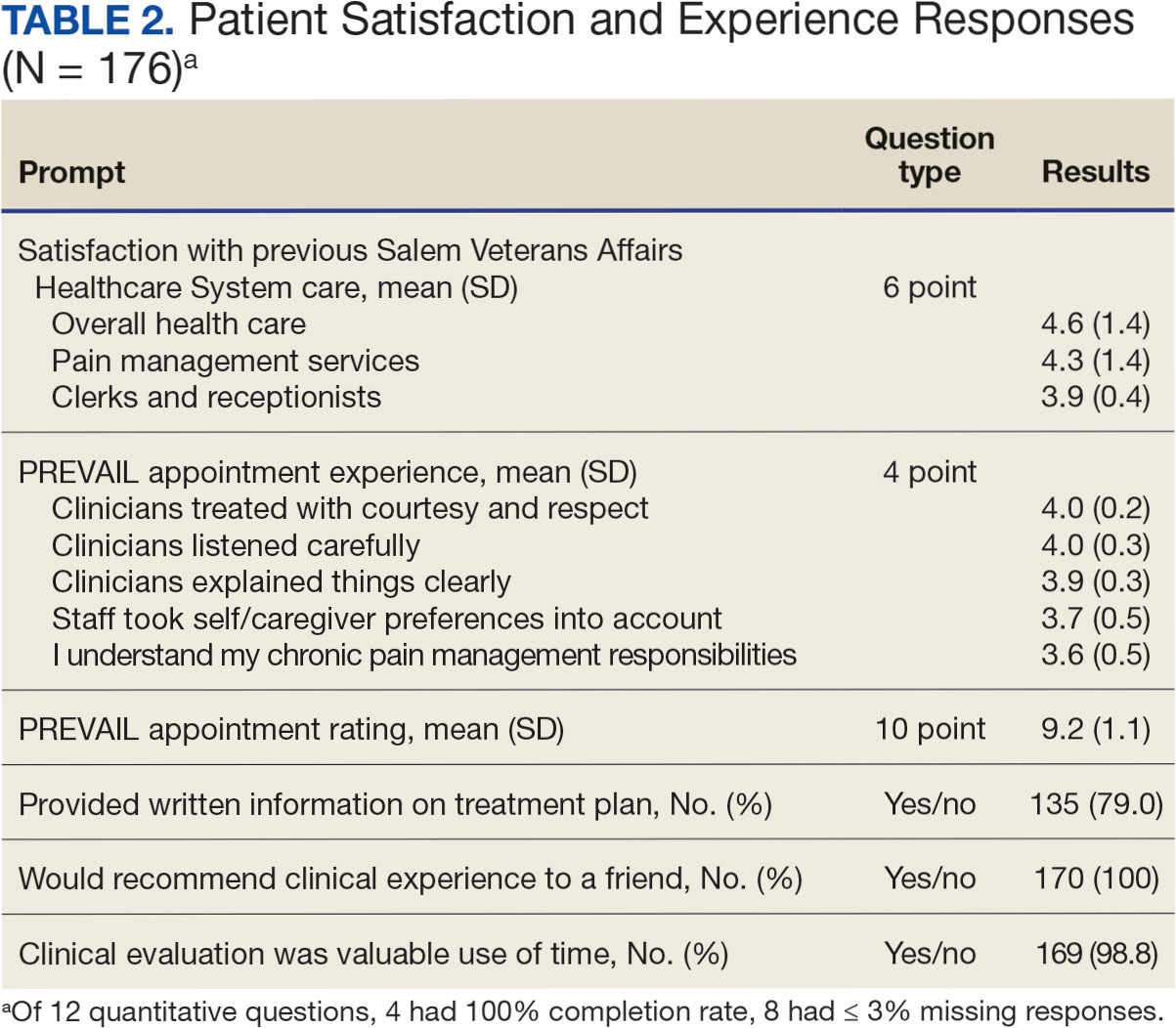

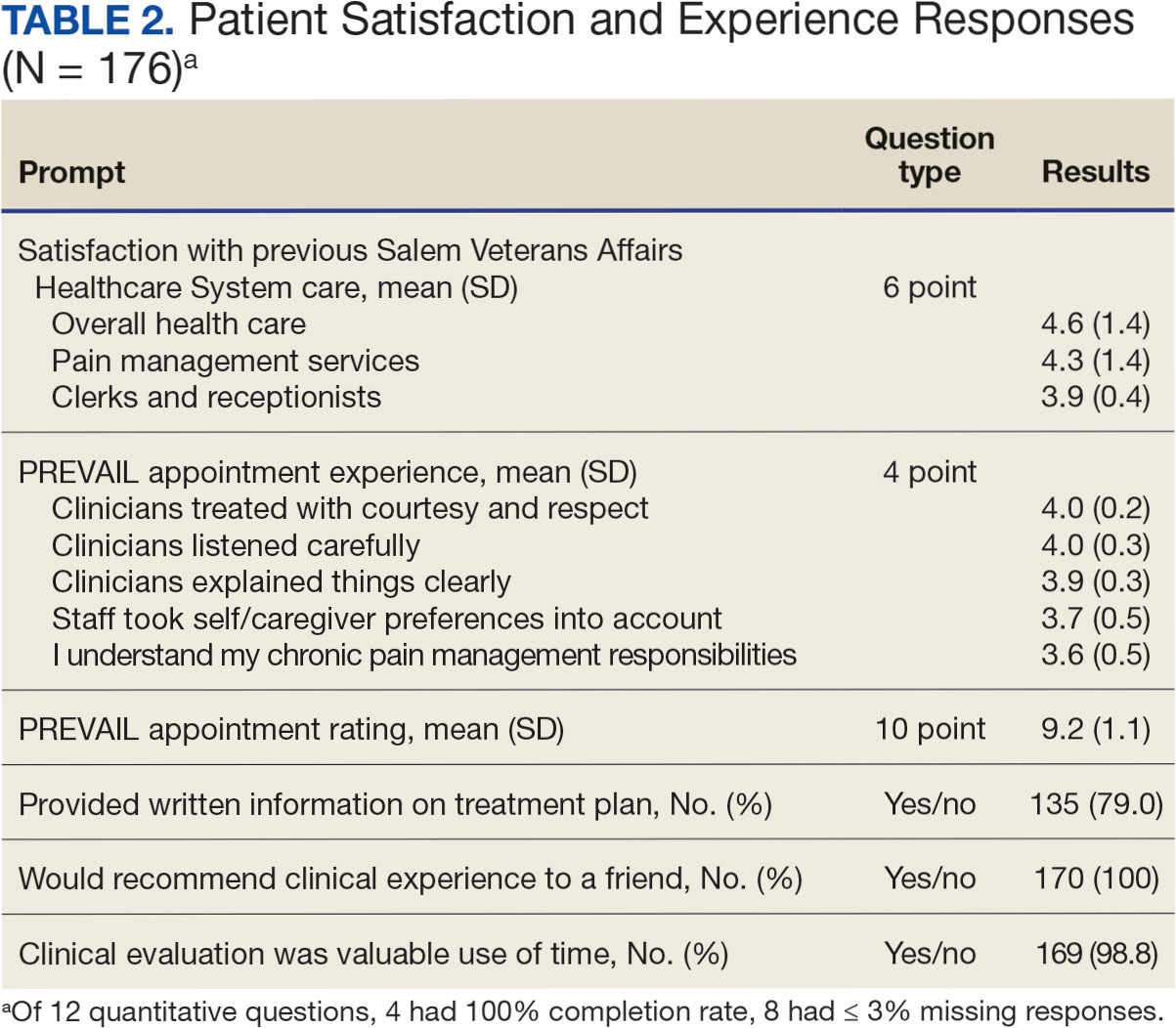

In 2022, 168 veterans completed the initial IDT evaluation, and 144 (85.2%) completed the satisfaction survey and were included in this study. Thirty-two support persons who attended the initial IDT evaluation and completed the survey also were included. Of the 12 quantitative questions, 4 had a 100% completion rate, while 8 had ≤ 3% missing responses. When describing care prior to participating in PREVAIL, participants indicated a mean (SD) response of 4.6 (1.4) with the health care they received at SVAHCS and 4.3 (1.4) with SVAHCS pain management services, both on 6-point scales. All but 2 participants (98.9%) reported always being treated with courtesy and respect by PREVAIL HCPs during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) score of 4.0 (0.2) on a 4-point scale. Most respondents (96.6%) reported that PREVAIL HCPs always listened carefully during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) 4.0 (0.3) on a 4-point scale. Similarly, 92.6% reported that PREVAIL HCPs explained things clearly during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) 3.9 (0.3) on a 4-point scale.

All respondents agreed that PREVAIL HCPs considered veteran preferences and those of their support persons in deciding their health care needs during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) 3.7 (0.5) on a 4-point scale. Most respondents left the appointment with a good understanding of their responsibilities for chronic pain management with 99.4% (n = 169) strongly agreeing or agreeing (mean [SD] 3.6 [0.5]). A total of 135 respondents (79.4%) reported they left appointments with written information on their treatment plan. All 170 respondents reported that they would recommend PREVAIL to a friend, and 169 respondents (98.8%) felt that the initial PREVAIL IDT evaluation was a valuable use of time. Eighty-seven respondents (50.9%) rated the initial IDT evaluation as the “best clinical experience possible” with a mean (SD) score of 9.2 (1.1) on a 10-point scale (Table 2).

Qualitative Responses

Respondents provided complementary feedback on the program, with many participants stating that they enjoyed every aspect (eAppendix, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0503). In terms of positive aspects of the program, several themes emerged: participants appreciated meeting as an IDT, feeling cared for and listened to, learning more about their pain and ways to manage it, and specific services offered. Thirty-three of 144 respondents wanted longer appointment times. Twenty-two respondents suggested logistics improvements (eg, meeting in a larger room, having a written plan at the end, sending paperwork ahead of time, and later appointment times).

Discussion

Veterans and support persons were satisfied with the initial IDT evaluation for the PREVAIL whole health-focused pain clinical program for veterans predominantly residing in central Appalachia. These satisfaction findings are noteworthy since 20% of this same sample reported dissatisfaction with prior pain services, which could affect engagement and outcomes in pain care. In addition to high satisfaction levels, the PREVAIL IDT model may benefit veterans with limited resources. Rather than needing to attend several individual appointments, the PREVAIL IDT Track provides a 1-stop shop approach that decreases patient burden and barriers to care (eg, travel, transportation, and time) as well as health care system burden. For instance, schedulers need only to make 1 appointment for the veteran rather than several. This approach was highly acceptable to veterans served at SVAHCS and may increase the reach and impact of VHA IDT pain care.

The PREVAIL model may foster rapport with HCPs and encourage an active role in self-managing pain.36,37 Participants noted that their preferences were considered and that they had a good understanding of their responsibilities for managing their chronic pain. This patient-centered approach, emphasizing an active role for the patient, is a hallmark of the VHA Whole Health System and aligns with the overarching PREVAIL IDT Track goal to enhance self-management skills, thus improving functioning through decreased pain interference.14,38-41

Participants in PREVAIL provided substantial open-ended feedback that has contributed to the program’s improvement and may provide information into preferred components of pain IDT programs, particularly for rural veterans. When asked about their favorite component of the initial IDT evaluation, the most emergent theme was meeting simultaneously with HCPs on the IDT. This finding is significant, given that only 11% of IDTs involve direct patient interaction.

Furthermore, unlike most IDTs, PREVAIL IDT includes a dietitian.11,42 IDT programs may benefit from dietitian involvement given the importance of the anti-inflammatory diet on chronic pain.43-46 Participants recommended improvements, (eg, changes to the location and timing, adding a written treatment plan at the end of the appointment, and completing paperwork prior to the appointment) many of which have been addressed. The program now uses validated measures to track progress and comprehensive assessments of pain in response to calls for measurement-based care.13,47 These process improvement suggestions may be instructive for other VA medical centers with rural populations.

Limitations

This study used a program-specific satisfaction survey with open-ended questions to allow for rich responses; however, the survey has not been validated. It also sought to minimize bias by asking participants to give completed surveys to staff members who were not HCPs on the IDT. However, participants’ responses may still have been influenced by this process. Response rate and demographics for support persons were impossible to determine. The results analyzed the responses of veterans and support persons together, which may have skewed the data. Future studies of pain IDT programs should consider analyzing responses from veterans and their support persons separately and identifying factors (eg, demographics or clinical characteristics) that influence the patients’ experiences while participating.

Conclusions

The initial PREVAIL IDT evaluation at SVAHCS is associated with high-levels of satisfaction. These veterans living in rural Appalachia, similar to the 4.4 million rural US veterans, are more likely to encounter barriers to care (eg, drive time, or transportation concerns) and be prescribed opioids.48 These veterans are also at high risk of chronic physical and mental health comorbidities, drug misuse, overdose, and suicide.49,50 Providing veterans in rural communities the opportunity to attend a single appointment with a pain IDT instead of requiring several individual appointments could improve the reach of evidence-based pain care.

This model of meeting simultaneously with all HCPs on the pain IDT may connect all veterans to the most available and best care, something prioritized by the VHA.28 The initial PREVAIL IDT evaluation also utilizes the Personal Health Inventory and the VHA Whole Health System Circle of Health to design patient-centered treatment plans. Integration of the Whole Health System is currently a high priority within VHA. The PREVAIL IDT Track model warrants additional efficacy research.

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, Guy GP Jr. Chronic pain among adults - United States, 2019-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(15):379-385. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1

- Nahin RL. Severe Pain in Veterans: The effect of age and sex, and comparisons with the general population. J Pain. 2017;18(3):247-254. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2016.10.021

- Courtney RE, Schadegg MJ, Bolton R, Smith S, Harden SM. Using a whole health approach to build biopsychosocial-spiritual personal health plans for veterans with chronic pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2024;25(1):69-74. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2023.09.010

- Mackey SC, Pearl RG. Pain management: optimizing patient care through comprehensive, interdisciplinary models and continuous innovations. Anesthesiol Clin. 2023;41(2):xv-xvii. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2023.03.011

- Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119-130. doi:10.1037/a0035514

- Courtney RE, Schadegg MJ. Chronic, noncancer pain care in the veterans administration: current trends and future directions. Anesthesiol Clin. 2023;41(2):519-529. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2023.02.004

- Gallagher RM. Advancing the pain agenda in the veteran population. Anesthesiol Clin. 2016;34(2):357-378. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2016.01.003

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h444. doi:10.1136/bmj.h444

- Waterschoot FPC, Dijkstra PU, Hollak N, De Vries HJ, Geertzen JHB, Reneman MF. Dose or content? Effectiveness of pain rehabilitation programs for patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain. 2014;155(1):179-189. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.10.006

- Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(5):670-678. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken021

- Elbers S, Wittink H, Konings S, et al. Longitudinal outcome evaluations of interdisciplinary multimodal pain Treatment programmes for patients with chronic primary musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pain. 2022;26(2):310-335. doi:10.1002/ejp.1875

- Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Allen RR, et al. Core outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2003;106(3):337-345. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2003.08.001

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113(1-2):9-19. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012

- Kligler B, Hyde J, Gantt C, Bokhour B. The whole health transformation at the Veterans Health Administration: moving from “what’s the matter with you?” to “what matters to you?”. Med Care. 2022;60(5):387-391. doi:10.1097/mlr.0000000000001706

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Transforming Health Care to Create Whole Health: Strategies to Assess, Scale, and Spread the Whole Person Approach to Health, Meisnere M, SouthPaul J, Krist AH, eds. Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation. National Academies Press (US); February 15, 2023.

- The time Is now for a whole-person health approach to public health. Public Health Rep. 2023;138(4):561-564. doi:10.1177/00333549231154583

- Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole health: the vision and implementation of personalized, proactive, patient-driven health care for veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12 Suppl 5):S5-S8. doi:10.1097/mlr.0000000000000226

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Kligler B, et al. From patient outcomes to system change: evaluating the impact of VHA’s implementation of the whole health system of care. Health Serv Res. 2022;57 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):53-65. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13938

- Zeliadt SB, Douglas JH, Gelman H, et al. Effectiveness of a whole health model of care emphasizing complementary and integrative health on reducing opioid use among patients with chronic pain. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1053. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08388-2

- Reed DE 2nd, Bokhour BG, Gaj L, et al. Whole health use and interest across veterans with cooccurring chronic pain and PTSD: an examination of the 18 VA medical center flagship sites. Glob Adv Health Med. 2022;11:21649561211065374. doi:10.1177/21649561211065374

- Etingen B, Smith BM, Zeliadt SB, et al. VHA whole health services and complementary and integrative health therapies: a gateway to evidence-based mental health treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(14):3144-3151. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08296-z

- Johnson EM, Possemato K, Khan S, Chinman M, Maisto SA. Engagement, experience, and satisfaction with peerdelivered whole health coaching for veterans with PTSD: a mixed methods process evaluation. Psychol Serv. 2021;19(2):305-316. doi:10.1037/ser0000529

- Purcell N, Zamora K, Gibson C, et al. Patient experiences with integrated pain care: a qualitative evaluation of one VA’s biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain treatment and opioid safety. Glob Adv Health Med. 2019;8:2164956119838845. doi:10.1177/2164956119838845

- Will KK, Johnson ML, Lamb G. Team-based care and patient satisfaction in the hospital setting: a systematic review. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2019;6(2):158-171. doi:10.17294/2330-0698.1695

- van Dongen JJJ, Habets IGJ, Beurskens A, van Bokhoven MA. Successful participation of patients in interprofessional team meetings: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2017;20(4):724-733. doi:10.1111/hex.12511

- Oliver DP, Albright DL, Kruse RL, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Washington K, Demiris G. Caregiver evaluation of the ACTIVE intervention: “it was like we were sitting at the table with everyone.” Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(4):444-453. doi:10.1177/1049909113490823

- Ansmann L, Heuser C, Diekmann A, et al. Patient participation in multidisciplinary tumor conferences: how is it implemented? What is the patients’ role? What are patients’ experiences? Cancer Med. 2021;10(19):6714-6724. doi:10.1002/cam4.4213

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Updated March 20, 2023. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.va.gov/health/priorities/index.asp

- Darnall BD, Edwards KA, Courtney RE, Ziadni MS, Simons LE, Harrison LE. Innovative treatment formats, technologies, and clinician trainings that improve access to behavioral pain treatment for youth and adults. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2023;4:1223172. doi:10.3389/fpain.2023.1223172

- Kligler B. Whole health in the Veterans Health Administration. Glob Adv Health Med. 2022;11:2164957X221077214.

- Howe RJ, Poulin LM, Federman DG. The personal health inventory: current use, perceived barriers, and benefits. Fed Pract. 2017;34(5):23-26. doi:10.1177/2164957X221077214

- Hicks N, Harden S, Oursler KA, Courtney RE. Determining the representativeness of participants in a whole health interdisciplinary chronic pain program (PREVAIL) in a VA medical center: who did we reach? Presented at: PAINWeek 2022; September 6-9, 2022; Las Vegas, Nevada. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00325481.2022.2116839

- Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. SAGE Publications; 2018.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual in Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance, 3rd edition. Published September 26, 2012. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/introduction

- Alexander JA, Hearld LR, Mittler JN, Harvey J. Patient-physician role relationships and patient activation among individuals with chronic illness. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 PART 1):1201-1223. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01354.x

- Fu Y, Yu G, McNichol E, Marczewski K, Closs SJ. The association between patient-professional partnerships and self-management of chronic back pain: a mixed methods study. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(7):1229-1244. doi:10.1002/ejp.1210

- Nicholas MK, Asghari A, Blyth FM, et al. Self-management intervention for chronic pain in older adults: a randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2013;154(6):824-835. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.009

- Nøst TH, Steinsbekk A, Bratås O, Grønning K. Twelvemonth effect of chronic pain self-management intervention delivered in an easily accessible primary healthcare service - a randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1012. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3843-x

- Blyth FM, March LM, Nicholas MK, Cousins MJ. Selfmanagement of chronic pain: a population-based study. Pain. 2005;113(3):285-292. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.004

- Damush TM, Kroenke K, Bair MJ, et al. Pain self-management training increases self-efficacy, self-management behaviours and pain and depression outcomes. Eur J Pain. 2016;20(7):1070-1078. doi:10.1002/ejp.830

- Murphy JL, Palyo SA, Schmidt ZS, et al. The resurrection of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation: outcomes across a veterans affairs collaborative. Pain Med. 2021;22(2):430- 443. doi:10.1093/pm/pnaa417

- Brain K, Burrows TL, Bruggink L, et al. Diet and chronic non-cancer pain: the state of the art and future directions. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):5203. doi:10.3390/jcm10215203

- Field R, Pourkazemi F, Turton J, Rooney K. Dietary interventions are beneficial for patients with chronic pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Pain Med). 2021;22(3):694-714. doi:10.1093/pm/pnaa378

- Bjørklund G, Aaseth J, Do§a MD, et al. Does diet play a role in reducing nociception related to inflammation and chronic pain? Nutrition. 2019;66:153-165. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2019.04.007

- Kaushik AS, Strath LJ, Sorge RE. Dietary interventions for treatment of chronic pain: oxidative stress and inflammation. Pain Ther. 2020;9(2):487-498. doi:10.1007/s40122-020-00200-5

- Boswell JF, Hepner KA, Lysell K, et al. The need for a measurement-based care professional practice guideline. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2023;60(1):1-16. doi:10.1037/pst0000439

- Lund BC, Ohl ME, Hadlandsmyth K, Mosher HJ. Regional and rural-urban variation in opioid prescribing in the Veterans Health Administration. Mil Med. 2019;184(11-12):894- 900. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz104

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Rural veterans. Updated May 14, 2024. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/aboutus/ruralvets.asp

- McCarthy JF, Blow FC, Ignacio R V., Ilgen MA, Austin KL, Valenstein M. Suicide among patients in the Veterans Affairs health system: rural-urban differences in rates, risks, and methods. Am J Public Health. 2012;102 Suppl 1(suppl 1):S111-S117. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300463

Chronic pain is one of the most prevalent public health concerns in the United States, affecting > 51 million adults with about $500 billion in health care costs.1 Military veterans are among the most vulnerable subpopulations, with 65% of veterans reporting chronic pain in the last 3 months.2 Chronic pain is complex, affecting the biopsychosocial-spiritual levels of human health, and requires multimodal and comprehensive treatment approaches.3 Hence, chronic pain treatment can be best delivered via interdisciplinary teams (IDTs) that use a patient-centered approach.4,5

The Veterans Healthcare Administration (VHA) is a leader in developing and delivering interdisciplinary pain care.6,7 VHA Directive 2009-053 requires every US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center to offer an IDT for chronic pain. However, VHA and non-VHA IDT programs vary significantly.8-11 A recent systematic review found a median of 5 disciplines included on IDTs (range, 2-8), and program content often included exercise and education; only 11% of included IDTs met simultaneously with patients.11 The heterogeneity of IDT programs has made determining best practices challenging.8,11 The Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials has denoted several core measures and measurement domains that were critical for determining the success of pain management interventions, including patient satisfaction.12,13 Nevertheless, the association of IDTs with high patient satisfaction and improvement in pain measures has been documented.5,11

The VHA has worked to implement the Whole Health System into health care, which considers well-being across physical, behavioral, spiritual, and socioeconomic domains. As such, the Whole Health System involves an interpersonal, team-based approach, “anchored in trusting longitudinal relationships to promote resilience, prevent disease, and restore health.”14 It aligns with the patient’s mission, aspiration, and purpose. Surgeon General VADM Vivek H. Murthy, MD, MBA, recently endorsed this approach.15,16 Other health care systems adopting whole health tend to have higher patient satisfaction, increased access to care, and improved patient-reported outcomes.15 Within the VHA, the Whole Health System has shifted the conversation between clinicians and patients from “What is the matter with you?” to “What is important to you?” while emphasizing a proactive and personalized approach to health care.17 Rather than emphasizing passive modalities such as medications and clinician-led services (eg, interventional pain service), the Whole Health System highlights self-care.3,17 Initial research findings within the VHA have been promising.18-21 Whole health peer coaching calls appear to be an effective approach for veterans diagnosed with PTSD, and the use of whole health services is associated with a decrease in opioid use.19,22 However, there are negligible data on patient experiences after meeting with a whole health-focused pain IDT, and studies to date have focused on urban populations.23 One approach to IDT that has shown promise for other health issues involves a patient meeting simultaneously with all members of the IDT.24-27 With the integration of the Whole Health System and the VHA priorities to provide veterans with the “soonest and best care,” more data are needed on the experiences of patients and support persons with various approaches to IDT pain care.28 This study aimed to evaluate patient and support person experiences with a whole health-focused pain IDT that met simultaneously with the patient and support person during an initial evaluation. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the Salem VA Health Care System (SVAHCS) in Virginia.

Methods

The PREVAIL IDT Track is a clinical program offered at SVAHCS with a whole health-focused approach that involves patients and their support persons meeting simultaneously with a pain IDT. PREVAIL IDT Track is designed to help veterans more effectively self-manage chronic pain (Table 1).6,29 Health care practitioners (HCPs) at SVAHCS recommended that veterans with pain persisting for > 3 months participate in PREVAIL IDT Track. After meeting with an advanced practice clinician for an intake, veterans elected to participate in the PREVAIL IDT Track program and completed the initial 6 weeks of pain education. Veterans were then invited to be evaluated by the pain IDT. A team including HCPs from interventional pain, psychology, pharmacy, nutrition, and physical therapy services met with the veteran for 60 minutes. Veterans were also invited to bring a support person to the IDT initial evaluation.

During the IDT initial evaluation, HCPs inquired about the patient’s mission, aspiration, and purpose (“If you were in less pain, what would you be doing more of?”) and about whole health self-care and wellness factors that may contribute to their chronic pain using the Personal Health Inventory.30,31 Veterans were then invited to select 3 whole health self-care areas to focus on during the 6-month program.3 The IDT HCPs worked with the veteran to establish the treatment plan for the first month in the areas of self-care selected by the patient and made recommendations for additional treatments. If the veteran brought a support person to the IDT initial evaluation, their feedback was elicited throughout and at the end to ensure the final treatment plan and first month’s goals were realistic. At the end of the appointment, the veteran and their support person were asked to complete a program-specific satisfaction survey. The HCPs on the team and the veteran executed the treatment plan developed during the appointment, except for medication prescribing. Recommendations for medication changes are included in clinical notes. Veterans then received 5 monthly coaching calls from a nurse navigator with training in whole health and a 6-month follow-up appointment with the IDT HCPs to discuss a plan for continuity of care.

Participant demographic information was not collected, and participants were not compensated for completing the survey. Veterans in PREVAIL IDT Track are predominantly residents of central Appalachia, White, male, unemployed, have ≥ 1 mental and physical health comorbidity, and have a history of mental health treatment.32 Veterans participating in PREVAIL IDT had a mean age of 57 years, and about 1 in 3 have opioid prescriptions.32

A program-specific 17-question satisfaction survey was developed, which included questions related to satisfaction with previous SVAHCS pain care and staff interactions. To assess the overall impression of the IDT initial evaluation, 3 yes/no questions and a 0 to 10-point scale were used. The 5 remaining open-ended questions allowed participants to give feedback about the IDT initial evaluation.

Data Analysis

A convergent mixed-methods approach was used to evaluate participant satisfaction with the initial IDT evaluation. The study team collected and analyzed quantitative and qualitative survey data and triangulated the findings.33 For quantitative responses, frequencies and means were calculated using Python. For qualitative responses, thematic data analysis was conducted by systematic coding, using inductive methods and allowing themes to emerge. Study team members performed a line-by-line analysis of responses using NVivo to identify important codes and reach a consensus. This study adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research and followed the National Institute for Health Care Excellence checklist.34,35

Results

Quantitative Responses

In 2022, 168 veterans completed the initial IDT evaluation, and 144 (85.2%) completed the satisfaction survey and were included in this study. Thirty-two support persons who attended the initial IDT evaluation and completed the survey also were included. Of the 12 quantitative questions, 4 had a 100% completion rate, while 8 had ≤ 3% missing responses. When describing care prior to participating in PREVAIL, participants indicated a mean (SD) response of 4.6 (1.4) with the health care they received at SVAHCS and 4.3 (1.4) with SVAHCS pain management services, both on 6-point scales. All but 2 participants (98.9%) reported always being treated with courtesy and respect by PREVAIL HCPs during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) score of 4.0 (0.2) on a 4-point scale. Most respondents (96.6%) reported that PREVAIL HCPs always listened carefully during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) 4.0 (0.3) on a 4-point scale. Similarly, 92.6% reported that PREVAIL HCPs explained things clearly during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) 3.9 (0.3) on a 4-point scale.

All respondents agreed that PREVAIL HCPs considered veteran preferences and those of their support persons in deciding their health care needs during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) 3.7 (0.5) on a 4-point scale. Most respondents left the appointment with a good understanding of their responsibilities for chronic pain management with 99.4% (n = 169) strongly agreeing or agreeing (mean [SD] 3.6 [0.5]). A total of 135 respondents (79.4%) reported they left appointments with written information on their treatment plan. All 170 respondents reported that they would recommend PREVAIL to a friend, and 169 respondents (98.8%) felt that the initial PREVAIL IDT evaluation was a valuable use of time. Eighty-seven respondents (50.9%) rated the initial IDT evaluation as the “best clinical experience possible” with a mean (SD) score of 9.2 (1.1) on a 10-point scale (Table 2).

Qualitative Responses

Respondents provided complementary feedback on the program, with many participants stating that they enjoyed every aspect (eAppendix, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0503). In terms of positive aspects of the program, several themes emerged: participants appreciated meeting as an IDT, feeling cared for and listened to, learning more about their pain and ways to manage it, and specific services offered. Thirty-three of 144 respondents wanted longer appointment times. Twenty-two respondents suggested logistics improvements (eg, meeting in a larger room, having a written plan at the end, sending paperwork ahead of time, and later appointment times).

Discussion

Veterans and support persons were satisfied with the initial IDT evaluation for the PREVAIL whole health-focused pain clinical program for veterans predominantly residing in central Appalachia. These satisfaction findings are noteworthy since 20% of this same sample reported dissatisfaction with prior pain services, which could affect engagement and outcomes in pain care. In addition to high satisfaction levels, the PREVAIL IDT model may benefit veterans with limited resources. Rather than needing to attend several individual appointments, the PREVAIL IDT Track provides a 1-stop shop approach that decreases patient burden and barriers to care (eg, travel, transportation, and time) as well as health care system burden. For instance, schedulers need only to make 1 appointment for the veteran rather than several. This approach was highly acceptable to veterans served at SVAHCS and may increase the reach and impact of VHA IDT pain care.

The PREVAIL model may foster rapport with HCPs and encourage an active role in self-managing pain.36,37 Participants noted that their preferences were considered and that they had a good understanding of their responsibilities for managing their chronic pain. This patient-centered approach, emphasizing an active role for the patient, is a hallmark of the VHA Whole Health System and aligns with the overarching PREVAIL IDT Track goal to enhance self-management skills, thus improving functioning through decreased pain interference.14,38-41

Participants in PREVAIL provided substantial open-ended feedback that has contributed to the program’s improvement and may provide information into preferred components of pain IDT programs, particularly for rural veterans. When asked about their favorite component of the initial IDT evaluation, the most emergent theme was meeting simultaneously with HCPs on the IDT. This finding is significant, given that only 11% of IDTs involve direct patient interaction.

Furthermore, unlike most IDTs, PREVAIL IDT includes a dietitian.11,42 IDT programs may benefit from dietitian involvement given the importance of the anti-inflammatory diet on chronic pain.43-46 Participants recommended improvements, (eg, changes to the location and timing, adding a written treatment plan at the end of the appointment, and completing paperwork prior to the appointment) many of which have been addressed. The program now uses validated measures to track progress and comprehensive assessments of pain in response to calls for measurement-based care.13,47 These process improvement suggestions may be instructive for other VA medical centers with rural populations.

Limitations

This study used a program-specific satisfaction survey with open-ended questions to allow for rich responses; however, the survey has not been validated. It also sought to minimize bias by asking participants to give completed surveys to staff members who were not HCPs on the IDT. However, participants’ responses may still have been influenced by this process. Response rate and demographics for support persons were impossible to determine. The results analyzed the responses of veterans and support persons together, which may have skewed the data. Future studies of pain IDT programs should consider analyzing responses from veterans and their support persons separately and identifying factors (eg, demographics or clinical characteristics) that influence the patients’ experiences while participating.

Conclusions

The initial PREVAIL IDT evaluation at SVAHCS is associated with high-levels of satisfaction. These veterans living in rural Appalachia, similar to the 4.4 million rural US veterans, are more likely to encounter barriers to care (eg, drive time, or transportation concerns) and be prescribed opioids.48 These veterans are also at high risk of chronic physical and mental health comorbidities, drug misuse, overdose, and suicide.49,50 Providing veterans in rural communities the opportunity to attend a single appointment with a pain IDT instead of requiring several individual appointments could improve the reach of evidence-based pain care.

This model of meeting simultaneously with all HCPs on the pain IDT may connect all veterans to the most available and best care, something prioritized by the VHA.28 The initial PREVAIL IDT evaluation also utilizes the Personal Health Inventory and the VHA Whole Health System Circle of Health to design patient-centered treatment plans. Integration of the Whole Health System is currently a high priority within VHA. The PREVAIL IDT Track model warrants additional efficacy research.

Chronic pain is one of the most prevalent public health concerns in the United States, affecting > 51 million adults with about $500 billion in health care costs.1 Military veterans are among the most vulnerable subpopulations, with 65% of veterans reporting chronic pain in the last 3 months.2 Chronic pain is complex, affecting the biopsychosocial-spiritual levels of human health, and requires multimodal and comprehensive treatment approaches.3 Hence, chronic pain treatment can be best delivered via interdisciplinary teams (IDTs) that use a patient-centered approach.4,5

The Veterans Healthcare Administration (VHA) is a leader in developing and delivering interdisciplinary pain care.6,7 VHA Directive 2009-053 requires every US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center to offer an IDT for chronic pain. However, VHA and non-VHA IDT programs vary significantly.8-11 A recent systematic review found a median of 5 disciplines included on IDTs (range, 2-8), and program content often included exercise and education; only 11% of included IDTs met simultaneously with patients.11 The heterogeneity of IDT programs has made determining best practices challenging.8,11 The Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials has denoted several core measures and measurement domains that were critical for determining the success of pain management interventions, including patient satisfaction.12,13 Nevertheless, the association of IDTs with high patient satisfaction and improvement in pain measures has been documented.5,11

The VHA has worked to implement the Whole Health System into health care, which considers well-being across physical, behavioral, spiritual, and socioeconomic domains. As such, the Whole Health System involves an interpersonal, team-based approach, “anchored in trusting longitudinal relationships to promote resilience, prevent disease, and restore health.”14 It aligns with the patient’s mission, aspiration, and purpose. Surgeon General VADM Vivek H. Murthy, MD, MBA, recently endorsed this approach.15,16 Other health care systems adopting whole health tend to have higher patient satisfaction, increased access to care, and improved patient-reported outcomes.15 Within the VHA, the Whole Health System has shifted the conversation between clinicians and patients from “What is the matter with you?” to “What is important to you?” while emphasizing a proactive and personalized approach to health care.17 Rather than emphasizing passive modalities such as medications and clinician-led services (eg, interventional pain service), the Whole Health System highlights self-care.3,17 Initial research findings within the VHA have been promising.18-21 Whole health peer coaching calls appear to be an effective approach for veterans diagnosed with PTSD, and the use of whole health services is associated with a decrease in opioid use.19,22 However, there are negligible data on patient experiences after meeting with a whole health-focused pain IDT, and studies to date have focused on urban populations.23 One approach to IDT that has shown promise for other health issues involves a patient meeting simultaneously with all members of the IDT.24-27 With the integration of the Whole Health System and the VHA priorities to provide veterans with the “soonest and best care,” more data are needed on the experiences of patients and support persons with various approaches to IDT pain care.28 This study aimed to evaluate patient and support person experiences with a whole health-focused pain IDT that met simultaneously with the patient and support person during an initial evaluation. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the Salem VA Health Care System (SVAHCS) in Virginia.

Methods

The PREVAIL IDT Track is a clinical program offered at SVAHCS with a whole health-focused approach that involves patients and their support persons meeting simultaneously with a pain IDT. PREVAIL IDT Track is designed to help veterans more effectively self-manage chronic pain (Table 1).6,29 Health care practitioners (HCPs) at SVAHCS recommended that veterans with pain persisting for > 3 months participate in PREVAIL IDT Track. After meeting with an advanced practice clinician for an intake, veterans elected to participate in the PREVAIL IDT Track program and completed the initial 6 weeks of pain education. Veterans were then invited to be evaluated by the pain IDT. A team including HCPs from interventional pain, psychology, pharmacy, nutrition, and physical therapy services met with the veteran for 60 minutes. Veterans were also invited to bring a support person to the IDT initial evaluation.

During the IDT initial evaluation, HCPs inquired about the patient’s mission, aspiration, and purpose (“If you were in less pain, what would you be doing more of?”) and about whole health self-care and wellness factors that may contribute to their chronic pain using the Personal Health Inventory.30,31 Veterans were then invited to select 3 whole health self-care areas to focus on during the 6-month program.3 The IDT HCPs worked with the veteran to establish the treatment plan for the first month in the areas of self-care selected by the patient and made recommendations for additional treatments. If the veteran brought a support person to the IDT initial evaluation, their feedback was elicited throughout and at the end to ensure the final treatment plan and first month’s goals were realistic. At the end of the appointment, the veteran and their support person were asked to complete a program-specific satisfaction survey. The HCPs on the team and the veteran executed the treatment plan developed during the appointment, except for medication prescribing. Recommendations for medication changes are included in clinical notes. Veterans then received 5 monthly coaching calls from a nurse navigator with training in whole health and a 6-month follow-up appointment with the IDT HCPs to discuss a plan for continuity of care.

Participant demographic information was not collected, and participants were not compensated for completing the survey. Veterans in PREVAIL IDT Track are predominantly residents of central Appalachia, White, male, unemployed, have ≥ 1 mental and physical health comorbidity, and have a history of mental health treatment.32 Veterans participating in PREVAIL IDT had a mean age of 57 years, and about 1 in 3 have opioid prescriptions.32

A program-specific 17-question satisfaction survey was developed, which included questions related to satisfaction with previous SVAHCS pain care and staff interactions. To assess the overall impression of the IDT initial evaluation, 3 yes/no questions and a 0 to 10-point scale were used. The 5 remaining open-ended questions allowed participants to give feedback about the IDT initial evaluation.

Data Analysis

A convergent mixed-methods approach was used to evaluate participant satisfaction with the initial IDT evaluation. The study team collected and analyzed quantitative and qualitative survey data and triangulated the findings.33 For quantitative responses, frequencies and means were calculated using Python. For qualitative responses, thematic data analysis was conducted by systematic coding, using inductive methods and allowing themes to emerge. Study team members performed a line-by-line analysis of responses using NVivo to identify important codes and reach a consensus. This study adhered to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research and followed the National Institute for Health Care Excellence checklist.34,35

Results

Quantitative Responses

In 2022, 168 veterans completed the initial IDT evaluation, and 144 (85.2%) completed the satisfaction survey and were included in this study. Thirty-two support persons who attended the initial IDT evaluation and completed the survey also were included. Of the 12 quantitative questions, 4 had a 100% completion rate, while 8 had ≤ 3% missing responses. When describing care prior to participating in PREVAIL, participants indicated a mean (SD) response of 4.6 (1.4) with the health care they received at SVAHCS and 4.3 (1.4) with SVAHCS pain management services, both on 6-point scales. All but 2 participants (98.9%) reported always being treated with courtesy and respect by PREVAIL HCPs during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) score of 4.0 (0.2) on a 4-point scale. Most respondents (96.6%) reported that PREVAIL HCPs always listened carefully during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) 4.0 (0.3) on a 4-point scale. Similarly, 92.6% reported that PREVAIL HCPs explained things clearly during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) 3.9 (0.3) on a 4-point scale.

All respondents agreed that PREVAIL HCPs considered veteran preferences and those of their support persons in deciding their health care needs during the initial IDT evaluation, with a mean (SD) 3.7 (0.5) on a 4-point scale. Most respondents left the appointment with a good understanding of their responsibilities for chronic pain management with 99.4% (n = 169) strongly agreeing or agreeing (mean [SD] 3.6 [0.5]). A total of 135 respondents (79.4%) reported they left appointments with written information on their treatment plan. All 170 respondents reported that they would recommend PREVAIL to a friend, and 169 respondents (98.8%) felt that the initial PREVAIL IDT evaluation was a valuable use of time. Eighty-seven respondents (50.9%) rated the initial IDT evaluation as the “best clinical experience possible” with a mean (SD) score of 9.2 (1.1) on a 10-point scale (Table 2).

Qualitative Responses

Respondents provided complementary feedback on the program, with many participants stating that they enjoyed every aspect (eAppendix, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0503). In terms of positive aspects of the program, several themes emerged: participants appreciated meeting as an IDT, feeling cared for and listened to, learning more about their pain and ways to manage it, and specific services offered. Thirty-three of 144 respondents wanted longer appointment times. Twenty-two respondents suggested logistics improvements (eg, meeting in a larger room, having a written plan at the end, sending paperwork ahead of time, and later appointment times).

Discussion

Veterans and support persons were satisfied with the initial IDT evaluation for the PREVAIL whole health-focused pain clinical program for veterans predominantly residing in central Appalachia. These satisfaction findings are noteworthy since 20% of this same sample reported dissatisfaction with prior pain services, which could affect engagement and outcomes in pain care. In addition to high satisfaction levels, the PREVAIL IDT model may benefit veterans with limited resources. Rather than needing to attend several individual appointments, the PREVAIL IDT Track provides a 1-stop shop approach that decreases patient burden and barriers to care (eg, travel, transportation, and time) as well as health care system burden. For instance, schedulers need only to make 1 appointment for the veteran rather than several. This approach was highly acceptable to veterans served at SVAHCS and may increase the reach and impact of VHA IDT pain care.

The PREVAIL model may foster rapport with HCPs and encourage an active role in self-managing pain.36,37 Participants noted that their preferences were considered and that they had a good understanding of their responsibilities for managing their chronic pain. This patient-centered approach, emphasizing an active role for the patient, is a hallmark of the VHA Whole Health System and aligns with the overarching PREVAIL IDT Track goal to enhance self-management skills, thus improving functioning through decreased pain interference.14,38-41

Participants in PREVAIL provided substantial open-ended feedback that has contributed to the program’s improvement and may provide information into preferred components of pain IDT programs, particularly for rural veterans. When asked about their favorite component of the initial IDT evaluation, the most emergent theme was meeting simultaneously with HCPs on the IDT. This finding is significant, given that only 11% of IDTs involve direct patient interaction.

Furthermore, unlike most IDTs, PREVAIL IDT includes a dietitian.11,42 IDT programs may benefit from dietitian involvement given the importance of the anti-inflammatory diet on chronic pain.43-46 Participants recommended improvements, (eg, changes to the location and timing, adding a written treatment plan at the end of the appointment, and completing paperwork prior to the appointment) many of which have been addressed. The program now uses validated measures to track progress and comprehensive assessments of pain in response to calls for measurement-based care.13,47 These process improvement suggestions may be instructive for other VA medical centers with rural populations.

Limitations

This study used a program-specific satisfaction survey with open-ended questions to allow for rich responses; however, the survey has not been validated. It also sought to minimize bias by asking participants to give completed surveys to staff members who were not HCPs on the IDT. However, participants’ responses may still have been influenced by this process. Response rate and demographics for support persons were impossible to determine. The results analyzed the responses of veterans and support persons together, which may have skewed the data. Future studies of pain IDT programs should consider analyzing responses from veterans and their support persons separately and identifying factors (eg, demographics or clinical characteristics) that influence the patients’ experiences while participating.

Conclusions

The initial PREVAIL IDT evaluation at SVAHCS is associated with high-levels of satisfaction. These veterans living in rural Appalachia, similar to the 4.4 million rural US veterans, are more likely to encounter barriers to care (eg, drive time, or transportation concerns) and be prescribed opioids.48 These veterans are also at high risk of chronic physical and mental health comorbidities, drug misuse, overdose, and suicide.49,50 Providing veterans in rural communities the opportunity to attend a single appointment with a pain IDT instead of requiring several individual appointments could improve the reach of evidence-based pain care.

This model of meeting simultaneously with all HCPs on the pain IDT may connect all veterans to the most available and best care, something prioritized by the VHA.28 The initial PREVAIL IDT evaluation also utilizes the Personal Health Inventory and the VHA Whole Health System Circle of Health to design patient-centered treatment plans. Integration of the Whole Health System is currently a high priority within VHA. The PREVAIL IDT Track model warrants additional efficacy research.

- Rikard SM, Strahan AE, Schmit KM, Guy GP Jr. Chronic pain among adults - United States, 2019-2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(15):379-385. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7215a1

- Nahin RL. Severe Pain in Veterans: The effect of age and sex, and comparisons with the general population. J Pain. 2017;18(3):247-254. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2016.10.021

- Courtney RE, Schadegg MJ, Bolton R, Smith S, Harden SM. Using a whole health approach to build biopsychosocial-spiritual personal health plans for veterans with chronic pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2024;25(1):69-74. doi:10.1016/j.pmn.2023.09.010

- Mackey SC, Pearl RG. Pain management: optimizing patient care through comprehensive, interdisciplinary models and continuous innovations. Anesthesiol Clin. 2023;41(2):xv-xvii. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2023.03.011

- Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119-130. doi:10.1037/a0035514

- Courtney RE, Schadegg MJ. Chronic, noncancer pain care in the veterans administration: current trends and future directions. Anesthesiol Clin. 2023;41(2):519-529. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2023.02.004

- Gallagher RM. Advancing the pain agenda in the veteran population. Anesthesiol Clin. 2016;34(2):357-378. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2016.01.003

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h444. doi:10.1136/bmj.h444

- Waterschoot FPC, Dijkstra PU, Hollak N, De Vries HJ, Geertzen JHB, Reneman MF. Dose or content? Effectiveness of pain rehabilitation programs for patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain. 2014;155(1):179-189. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.10.006

- Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(5):670-678. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ken021

- Elbers S, Wittink H, Konings S, et al. Longitudinal outcome evaluations of interdisciplinary multimodal pain Treatment programmes for patients with chronic primary musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pain. 2022;26(2):310-335. doi:10.1002/ejp.1875

- Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Allen RR, et al. Core outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2003;106(3):337-345. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2003.08.001

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113(1-2):9-19. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012

- Kligler B, Hyde J, Gantt C, Bokhour B. The whole health transformation at the Veterans Health Administration: moving from “what’s the matter with you?” to “what matters to you?”. Med Care. 2022;60(5):387-391. doi:10.1097/mlr.0000000000001706

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Transforming Health Care to Create Whole Health: Strategies to Assess, Scale, and Spread the Whole Person Approach to Health, Meisnere M, SouthPaul J, Krist AH, eds. Achieving Whole Health: A New Approach for Veterans and the Nation. National Academies Press (US); February 15, 2023.

- The time Is now for a whole-person health approach to public health. Public Health Rep. 2023;138(4):561-564. doi:10.1177/00333549231154583

- Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole health: the vision and implementation of personalized, proactive, patient-driven health care for veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12 Suppl 5):S5-S8. doi:10.1097/mlr.0000000000000226

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Kligler B, et al. From patient outcomes to system change: evaluating the impact of VHA’s implementation of the whole health system of care. Health Serv Res. 2022;57 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):53-65. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13938

- Zeliadt SB, Douglas JH, Gelman H, et al. Effectiveness of a whole health model of care emphasizing complementary and integrative health on reducing opioid use among patients with chronic pain. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1053. doi:10.1186/s12913-022-08388-2

- Reed DE 2nd, Bokhour BG, Gaj L, et al. Whole health use and interest across veterans with cooccurring chronic pain and PTSD: an examination of the 18 VA medical center flagship sites. Glob Adv Health Med. 2022;11:21649561211065374. doi:10.1177/21649561211065374

- Etingen B, Smith BM, Zeliadt SB, et al. VHA whole health services and complementary and integrative health therapies: a gateway to evidence-based mental health treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(14):3144-3151. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08296-z

- Johnson EM, Possemato K, Khan S, Chinman M, Maisto SA. Engagement, experience, and satisfaction with peerdelivered whole health coaching for veterans with PTSD: a mixed methods process evaluation. Psychol Serv. 2021;19(2):305-316. doi:10.1037/ser0000529

- Purcell N, Zamora K, Gibson C, et al. Patient experiences with integrated pain care: a qualitative evaluation of one VA’s biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain treatment and opioid safety. Glob Adv Health Med. 2019;8:2164956119838845. doi:10.1177/2164956119838845

- Will KK, Johnson ML, Lamb G. Team-based care and patient satisfaction in the hospital setting: a systematic review. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2019;6(2):158-171. doi:10.17294/2330-0698.1695

- van Dongen JJJ, Habets IGJ, Beurskens A, van Bokhoven MA. Successful participation of patients in interprofessional team meetings: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2017;20(4):724-733. doi:10.1111/hex.12511

- Oliver DP, Albright DL, Kruse RL, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Washington K, Demiris G. Caregiver evaluation of the ACTIVE intervention: “it was like we were sitting at the table with everyone.” Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(4):444-453. doi:10.1177/1049909113490823

- Ansmann L, Heuser C, Diekmann A, et al. Patient participation in multidisciplinary tumor conferences: how is it implemented? What is the patients’ role? What are patients’ experiences? Cancer Med. 2021;10(19):6714-6724. doi:10.1002/cam4.4213

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Updated March 20, 2023. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.va.gov/health/priorities/index.asp

- Darnall BD, Edwards KA, Courtney RE, Ziadni MS, Simons LE, Harrison LE. Innovative treatment formats, technologies, and clinician trainings that improve access to behavioral pain treatment for youth and adults. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2023;4:1223172. doi:10.3389/fpain.2023.1223172

- Kligler B. Whole health in the Veterans Health Administration. Glob Adv Health Med. 2022;11:2164957X221077214.

- Howe RJ, Poulin LM, Federman DG. The personal health inventory: current use, perceived barriers, and benefits. Fed Pract. 2017;34(5):23-26. doi:10.1177/2164957X221077214

- Hicks N, Harden S, Oursler KA, Courtney RE. Determining the representativeness of participants in a whole health interdisciplinary chronic pain program (PREVAIL) in a VA medical center: who did we reach? Presented at: PAINWeek 2022; September 6-9, 2022; Las Vegas, Nevada. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00325481.2022.2116839

- Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. SAGE Publications; 2018.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual in Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Methods for the development of NICE public health guidance, 3rd edition. Published September 26, 2012. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/introduction

- Alexander JA, Hearld LR, Mittler JN, Harvey J. Patient-physician role relationships and patient activation among individuals with chronic illness. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 PART 1):1201-1223. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01354.x

- Fu Y, Yu G, McNichol E, Marczewski K, Closs SJ. The association between patient-professional partnerships and self-management of chronic back pain: a mixed methods study. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(7):1229-1244. doi:10.1002/ejp.1210

- Nicholas MK, Asghari A, Blyth FM, et al. Self-management intervention for chronic pain in older adults: a randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2013;154(6):824-835. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.009

- Nøst TH, Steinsbekk A, Bratås O, Grønning K. Twelvemonth effect of chronic pain self-management intervention delivered in an easily accessible primary healthcare service - a randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1012. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3843-x

- Blyth FM, March LM, Nicholas MK, Cousins MJ. Selfmanagement of chronic pain: a population-based study. Pain. 2005;113(3):285-292. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2004.12.004

- Damush TM, Kroenke K, Bair MJ, et al. Pain self-management training increases self-efficacy, self-management behaviours and pain and depression outcomes. Eur J Pain. 2016;20(7):1070-1078. doi:10.1002/ejp.830