User login

Medication treatment of opioid use disorder in primary care practice: Opportunities and limitations

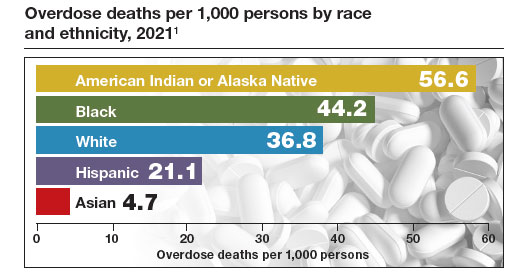

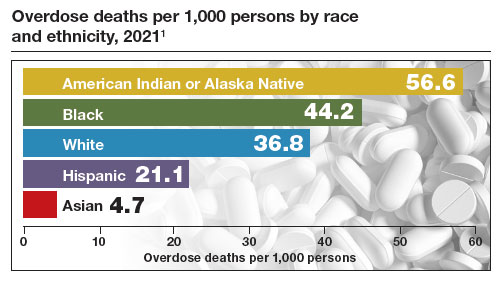

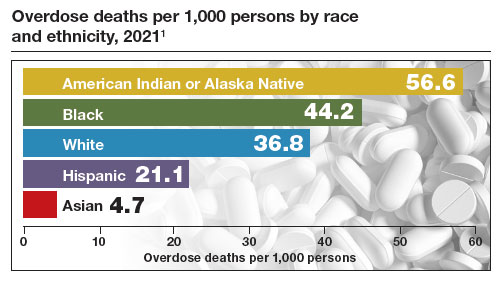

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 106,699 deaths in 2021 from drug overdose, with the majority being linked to synthetic opioids, including fentanyl and tramadol.1 This number compares with 42,795 deaths due to motor vehicle accidents and 48,183 deaths due to suicide in 2021.2,3 Most of the opioid overdose deaths occurred among people aged 25 to 64 years, the peak age of patients cared for by obstetrician-gynecologists. Among pregnant and postpartum persons, mortality due to drug overdose has increased by 81% between 2017 and 2020.4

Among pregnant and postpartum patients, drug overdose death is more common than suicide, and the risk for drug overdose death appears to be greatest in the year following delivery.5,6 In many cases, postpartum patients with OUD have had multiple contacts with the health care system prior to their death, showing that there is an opportunity for therapeutic intervention before the death occurred.7 Medication-assisted recovery for OUD involves a comprehensive array of interventions including medication, counseling, and social support. Medication treatment of OUD with BUP or methadone reduces the risk for death but is underutilized among patients with OUD.6,8 Recent federal legislation has removed restrictions on the use of BUP, increasing the opportunity for primary care clinicians to prescribe it for the treatment of OUD.9

Screening and diagnosis of OUD

Screening for OUD is recommended for patients who are at risk for opioid misuse (ie, those who are taking/have taken opioid medications). The OWLS (Overuse, Worrying, Losing interest, and feeling Slowed down, sluggish, or sedated) screening tool is used to detect prescription medication OUD and has 4 questions10:

1. In the past 3 months did you use your opioid medicines for other purposes—for example, to help you sleep or to help with stress or worry?

2. In the past 3 months did opioid medicines cause you to feel slowed down, sluggish, or sedated?

3. In the past 3 months did opioid medicines cause you to lose interest in your usual activities?

4. In the past 3 months did you worry about your use of opioid medicines?

Patient agreement with 3 or 4 questions indicates a positive screening test.

If the patient has a positive screening test, a formal diagnosis of OUD can be made using the 11 symptoms outlined in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition.11 The diagnosis of mild (2 to 3 symptoms), moderate (4 to 5 symptoms), or severe OUD (6 or more symptoms) is made based on the number of symptoms the patient reports.

Buprenorphine treatment of OUD in primary care

The role of primary care clinicians in the medication treatment of OUD is increasing. Using a nationwide system that tracks prescription medications, investigators reported that, in 2004, psychiatrists wrote 32.2% of all BUP prescriptions; in 2021, however, only 10% of such prescriptions were provided by psychiatrists, with most prescriptions written by non-psychiatrist physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants that year.12 Innovative telehealth approaches to consultation and medication treatment of OUD are now available—one example is QuickMD.13 Such sites are designed to remove barriers to initiating medication treatment of OUD.

The role of primary care clinicians in the management of OUD using BUP and buprenorphine-naloxone (BUP-NAL) has increased due to many factors, including:

- the removal of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) barriers to prescribing BUP

- the epidemic of OUD and the small size of the addiction specialist workforce, necessitating that primary care clinicians become engaged in the treatment of OUD

- an increase in unobserved initiation of BUP among ambulatory patients, and a parallel decrease in cases of observed initiation in addiction center settings

- the reframing of OUD as a chronic medical problem, with many similarities to diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.

Similar to other diseases managed by primary care clinicians, OUD requires long-term chronic treatment with a medicine that, if taken as directed, provides excellent outcomes. Primary care clinicians who prescribe BUP also can optimize longitudinal care for comorbid disorders such as hypertension and diabetes, which are prevalent in people with OUD.

In 2019, New Jersey implemented new guidelines for the treatment of OUD, removing prior authorization barriers, increasing reimbursement for office-based OUD treatment, and establishing regional centers of excellence. The implementation of the new guidelines was followed by a marked increase in BUP prescribers among primary care clinicians, emergency medicine physicians, and advanced practice clinicians.14

To estimate the public health impact of BUP prescribing by primary care clinicians, investigators simulated patient outcomes in 3 scenarios15:

1. primary care clinicians refer patients to addiction specialists for OUD treatment

2. primary care clinicians provide BUP services in their practice

3. primary care clinicians provide BUP and harm reduction kits containing syringes and wound care supplies in their practice.

Strategies 2 and 3 resulted in 14% fewer deaths due to opioid overdose, an increased life expectancy of approximately 2.7 years, and reduced hospital costs. For strategy 3, the incremental cost per life-year saved was $34,400. The investigators noted that prescribing BUP in primary care practice increases practice costs.15

Treatment with BUP reduces death from opioid overdose, improves patient health, decreases use of illicit opioids, and reduces patient cravings for opioids. BUP is a safe medication and is associated with fewer adverse effects than insulin or warfarin.16

Continue to: Methadone treatment of OUD...

Methadone treatment of OUD

Methadone is a full opioid agonist approved by the FDA for the treatment of severe pain or OUD. Methadone treatment of OUD is strictly regulated and typically is ordered and administered at an opioid treatment program that is federally licensed. Methadone for OUD treatment cannot be prescribed by a physician to a pharmacy, limiting its use in primary care practice. Methadone used to treat OUD is ordered and dispensed at opioid-treatment programs. Take-home doses of methadone may be available to patients after adherence to the regimen has been established. When used long-term, higher doses of methadone are associated with better adherence, but these higher doses can cause respiratory depression. In a study of 189 pregnant patients taking methadone to treat OUD, daily doses of 60 mg or greater were associated with better treatment retention at delivery and 60 days postpartum, as well as less use of nonprescription opioids.17 Under limited circumstances methadone can be ordered and dispensed for hospitalized patients with OUD.

Methadone is a pure opioid receptor agonist. Naloxone (NAL) is an opioid receptor antagonist. Buprenorphine (BUP) is a partial opioid receptor agonist-antagonist, which limits overdose risk. BUP often is combined with NAL as a combination formulation, which is thought to reduce the repurposing of BUP for non-prescribed uses. At appropriate treatment dosages, both methadone (≥60 mg) and BUP (≥ 16 mg) are highly effective for the treatment of OUD.1 For patients with health insurance, pharmacy benefits often provide some coverage for preferred products but no coverage for other products. Not all pharmacies carry BUP products. In a study of more than 5,000 pharmacies, approximately 60% reported that they carry and can dispense BUP medications.2

BUP monotherapy is available as generic sublingual tablets, buccal films (Belbuca), formulations for injection (Sublocade), and subcutaneous implants (Probuphine). BUPNAL is available as buccal films (Bunavail), sublingual films (Suboxone), and sublingual tablets (Zubsolv). For BUP-NAL combination productions, the following dose combinations have been reported to have similar effects: BUP-NAL 8 mg/2 mg sublingual film, BUP-NAL 5.7 mg/1.4 mg sublingual tablet, and BUP-NAL 4.2 mg/0.7 mg buccal film.3

When initiating BUP-monotherapy or BUP-NAL treatment for OUD, one approach for unobserved initiation is to instruct the patient to discontinue using opioid agonist drugs and wait for the onset of mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms. The purpose of this step is to avoid precipitating severe withdrawal symptoms caused by giving BUP or BUP-NAL to a patient who has recently used opioid drugs.

If BUP-NAL sublingual films (Suboxone) are prescribed following the onset of mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms, the patient can initiate therapy with a dose of 2 mg BUP/0.5 mg NAL or 4 mg BUP/1 mg NAL. At 60 to 120 minutes following the initial dose, if withdrawal symptoms persist, an additional dose of 4 mg BUP/1 mg NAL can be given. Thereafter, symptoms can be assessed every 60 to 120 minutes and additional doses administered to control symptoms. On the second day of therapy, a maximum of 16 mg of BUP is administered. Over the following days and weeks, if symptoms and cravings persist at a BUP dose of 16 mg, the total daily dose of BUP can be titrated up to 24 mg. For long-term treatment, a commonly prescribed daily dose is 16 mg BUP/4 mg NAL or 24 mg BUP/6 mg NAL. An absolute contraindication to BUP or BUP/NAL treatment is an allergy to the medication, and a relative contraindication is liver failure.

One potential complication of transmucosal BUP or BUP-NAL treatment is a dry mouth (xerostomia), which may contribute to dental disease.4 However, some experts question the quality of the data that contributed to the warning.5,6 Potential dental complications might be prevented by regular oral health examinations, daily flossing and teeth brushing, and stimulation of saliva by sugar-free gum or lozenges.

Primary care clinicians who initiate BUP or BUPNAL treatment for OUD often have a weekly visit with the patient during the initial phase of treatment and then every 3 to 4 weeks during maintenance therapy. Most patients need long-term treatment to achieve the goals of therapy, which include prevention of opioid overdose, reduction of cravings for nonprescription narcotics, and improvement in overall health. BUP and BUP-NAL treatment are effective without formal counseling, but counseling and social work support improve long-term adherence with treatment. Primary care clinicians who have experience with medication treatment of OUD report that their experience convinces them that medication treatment of OUD has similarities to the long-term treatment of diabetes, with antihyperglycemia medicines or the treatment of HIV infection with antiviral medications.

References

1. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD002207.

2. Weiner SG, Qato DM, Faust JS, et al. Pharmacy availability of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder treatment in the U.S. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:E2316089.

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Medications for opioid use disorder. SAMHSA website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https ://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/PEP 21-02-01-002.pdf

4. FDA warns about dental problems with buprenorphine medicines dissolved in the mouth. FDA website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https ://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-about-dental-problems-buprenorphine-medicines-dissolved-mouth-treat-opioiduse-disorder#:~:text=What%20did%20FDA%20find%3F,medicines%20 dissolved%20in%20the%20mouth

5. Watson DP, Etmian S, Gastala N. Sublingual buprenorphine-naloxone exposure and dental disease. JAMA. 2023;329:1223-1224.

6. Brothers TD, Lewer D, Bonn M. Sublingual buprenorphine-naloxone exposure and dental disease. JAMA. 2023;329:1224.

Medication treatment of OUD in obstetrics

In the United States, the prevalence of OUD among pregnant patients hospitalized for delivery more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2014.18 BUP and methadone commonly are used to treat OUD during pregnancy.19 Among pregnant patients about 5% of buprenorphine prescriptions are written by obstetricians.20 An innovative approach to initiating BUP for pregnant patients with OUD is to use unobserved initiation, which involves outpatient discontinuation of nonprescription opioids to induce mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms followed by initiation of BUP treatment. In one cohort study, 55 pregnant patients used an unobserved outpatient protocol to initiate BUP treatment; 80% of the patients previously had used methadone or BUP. No patient experienced a precipitated withdrawal and 96% of patients returned for their office visit 1 week after initiation of treatment. Eighty-six percent of patients remained in treatment 3 months following initiation of BUP.21

Compared with methadone, BUP treatment during pregnancy may result in lower rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome. In one study of pregnant patients who were using methadone (n = 5,056) or BUP (n = 11,272) in late pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome was diagnosed in 69.2% and 52.0% of newborns, respectively (adjusted relative risk, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.71–0.75).22 In addition, compared with methadone, the use of BUP was associated with a reduced risk for low birth weight (14.9% vs 8.3%) and a lower risk for preterm birth (24.9% vs 14.4%). In this study, there were no differences in maternal obstetric outcomes when comparing BUP versus methadone treatment. Similar results have been reported in a meta-analysis analyzing the use of methadone and BUP during pregnancy.23 Studies performed to date have not shown an increased risk of congenital anomalies with the use of BUP-NAL during pregnancy.24,25

Although there may be differences in newborn outcomes with BUP and methadone, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend switching from methadone to BUP during pregnancy because precipitated withdrawal may occur.26 Based on recent studies, the American Society of Addiction Medicine has advised that it is safe to prescribe pregnant patients either BUP or BUP-NAL.27,28

Medication treatment of OUD with or without intensive counseling

The FDA recently reviewed literature related to the advantages and challenges of combining intensive counseling with medication treatment of OUD.29 The FDA noted that treatment saves lives and encouraged clinicians to initiate medication treatment of OUD or refer the patient to an appropriate clinician or treatment center. Combining medication treatment of OUD with intensive counseling is associated with greater treatment adherence and reduced health care costs. For example, in one study of 4,987 patients with OUD, initiation of counseling within 8 weeks of the start of medication treatment and a BUP dose of 16 mg or greater daily were associated with increased adherence to treatment.30 For patients receiving a BUP dose of less than 16 mg daily, treatment adherence with and without counseling was approximately 325 and 230 days, respectively. When the dose of BUP was 16 mg or greater, treatment adherence with and without counseling was approximately 405 and 320 days, respectively.30

Counseling should always be offered to patients initiating medication treatment of OUD. It should be noted that counseling alone is not a highly effective treatment for OUD.31 The FDA recently advised that the lack of availability of intensive counseling should not prevent clinicians from initiating BUP for the treatment of OUD.29 OUD is associated with a high mortalityrate and if counseling is not possible, medication treatment should be initiated. Substantial evidence demonstrates that medication treatment of OUD is associated with many benefits.16 The FDA advisory committee concluded that OUD treatment decisions should use shared decision making and be supportive and patient centered.29

The opportunities for medication treatment of OUD in primary care practice have expanded due to the recent FDA removal of restrictions on the use of BUP and heightened awareness of the positive public health impact of medication treatment. Challenges to the medication treatment of OUD remain, including stigmatization of OUD, barriers to insurance coverage for BUP, practice costs of treating OUD, and gaps in clinical education. For many pregnant patients, their main point of contact with health care is their obstetrician. By incorporating OUD treatment in pregnancy care, obstetricians will improve the health of the mother and newborn, contributing to the well-being of current and future generations. ●

Experts have recommended several interventions that may help reduce opioid overdose death.1 A consensus recommendation is that people who use drugs should be provided naloxone rescue medication and educated on the proper use of naloxone. Naloxone rescue medication is available in formulations for nasal or parenteral administration. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently has approved naloxone for over-the-counter status. The American Medical Association has provided a short web video on how to administer nasal naloxone.2 In a small pilot study, obstetricians offered every postpartum patient with naloxone administration education and a 2-dose nasal naloxone pack, with 76% of patients accepting the nasal naloxone pack.3

Many experts recommend that people who use drugs should be advised to never use them alone and to test a small amount of the drug to assess its potency. Many patients who use opioid drugs also take benzodiazepines, which can contribute to respiratory depression.4 Patients should avoid mixing drugs (eg, opioids and benzodiazepines). Some experts recommend that patients who use drugs should be provided take-home fentanyl test strips so they can evaluate their drugs for the presence of fentanyl, a medication that suppresses respiration and contributes to many overdose deaths. In addition, people who use drugs and are interested in reducing their use of drugs or managing overdose risk can be offered initiation of medication treatment of OUD.1

References

1. Wood E, Solomon ED, Hadland SE. Universal precautions for people at risk of opioid overdose in North America. JAMA Int Med. 2023;183:401-402.

2. How to administer Naloxone. AMA website. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org /delivering-care/overdose-epidemic/how-administer-naloxone

3. Naliboff JA, Tharpe N. Universal postpartum naloxone provision: a harm reduction quality improvement project. J Addict Med. 2022;17:360-362.

4. Kelly JC, Raghuraman N, Stout MJ, et al. Home induction of buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:655-659.

- Spencer MR, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 20012021. NCHS Data Brief no 457. Hyattsville, MD, National Center for Health Statistics. 2022. NCHS Data Brief No. 457. Published December 2022. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov /nchs/products/databriefs/db457.htm

- US traffic deaths drop slightly in 2022 but still a ‘crisis.’ AP News website. Published April 20, 2023. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://apnews.com /article/traffic-deaths-distracted-driving-crisis -6db6471e273b275920b6c4f9eb7e493b

- Suicide statistics. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://afsp.org/suicide-statistics/

- Bruzelius E, Martins SS. US Trends in drug overdose mortality among pregnant and postpartum persons, 2017-2020. JAMA. 2022;328:2159-2161.

- Metz TD, Rovner P, Hoffman MC, et al. Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose in Colorado, 2004-2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1233-1240.

- Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Terplan M, et al. Fatal and nonfatal overdose among pregnant and postpartum women in Massachusetts. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:466-474.

- Goldman-Mellor S, Margerison CE. Maternal drug-related death and suicide are leading causes of postpartum death in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:489.e1-489.e9.

- Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550.

- Waiver elimination (MAT Act). SAMHSA website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www .samhsa.gov/medications-substance-use- disorders/removal-data-waiver-requirement

- Picco L, Middleton M, Bruno R, et al. Validation of the OWLS, a Screening Tool for Measuring Prescription Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care. Pain Med. 2020;21:2757-2764.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Creedon TB, Ali MM, Schuman-Olivier Z. Trends in buprenorphine prescribing for opioid use disorder by psychiatrists in the US from 2003 to 2021. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4:E230221.

- Quick MD website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://quick.md/

- Treitler P, Nowels M, Samples H, et al. BUP utilization and prescribing among New Jersey Medicaid beneficiaries after adoption of initiatives designed to improve treatment access. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:E2312030.

- Jawa R, Tin Y, Nall S, et al. Estimated clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness associated with provision of addiction treatment in US primary care clinics. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:E237888.

- Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways of opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:E1920622.

- Wilder CM, Hosta D, Winhusen T. Association of methadone dose with substance use and treatment retention in pregnant and postpartum women with opioid use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;80:33-36.

- Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, et al. Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization - United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:845-849.

- Xu KY, Jones HE, Schiff DM, et al. Initiation and treatment discontinuation of medications for opioid use disorder in pregnant people compared with nonpregnant people. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:845-853.

- Kelly D, Krans EE. Medical specialty of buprenorphine prescribers for pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:502-503.

- Kelly JC, Raghuraman N, Stout MJ, et al. Home induction of buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:655-659.

- Suarez EA, Huybrechts KF, Straub L, et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone for opioid use disorder in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2033-2044.

- Kinsella M, Halliday LO, Shaw M, et al. Buprenorphine compared with methadone in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57:1400-1416.

- Jumah NA, Edwards C, Balfour-Boehm J, et al. Observational study of the safety of buprenorphine-naloxone in pregnancy in a rural and remote population. BMJ Open. 2016;6:E011774.

- Mullins N, Galvin SL, Ramage M, et al. Buprenorphine and naloxone versus buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in pregnancy: a cohort study. J Addict Med. 2020;14:185-192.

- Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 711. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:E81-E94.

- The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2S suppl 1):1-91.

- Link HM, Jones H, Miller L, et al. Buprenorphinenaloxone use in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100179.

- Delphin-Rittmon ME, Cavazzoni P. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda .gov/media/168027/download

- Eren K, Schuster J, Herschell A, et al. Association of Counseling and Psychotherapy on retention in medication for addiction treatment within a large Medicaid population. J Addict Med. 2022;16:346353.

- Kakko J, Dybrandt Svanborg K, Kreek MJ, et al. 1-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:662-668.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 106,699 deaths in 2021 from drug overdose, with the majority being linked to synthetic opioids, including fentanyl and tramadol.1 This number compares with 42,795 deaths due to motor vehicle accidents and 48,183 deaths due to suicide in 2021.2,3 Most of the opioid overdose deaths occurred among people aged 25 to 64 years, the peak age of patients cared for by obstetrician-gynecologists. Among pregnant and postpartum persons, mortality due to drug overdose has increased by 81% between 2017 and 2020.4

Among pregnant and postpartum patients, drug overdose death is more common than suicide, and the risk for drug overdose death appears to be greatest in the year following delivery.5,6 In many cases, postpartum patients with OUD have had multiple contacts with the health care system prior to their death, showing that there is an opportunity for therapeutic intervention before the death occurred.7 Medication-assisted recovery for OUD involves a comprehensive array of interventions including medication, counseling, and social support. Medication treatment of OUD with BUP or methadone reduces the risk for death but is underutilized among patients with OUD.6,8 Recent federal legislation has removed restrictions on the use of BUP, increasing the opportunity for primary care clinicians to prescribe it for the treatment of OUD.9

Screening and diagnosis of OUD

Screening for OUD is recommended for patients who are at risk for opioid misuse (ie, those who are taking/have taken opioid medications). The OWLS (Overuse, Worrying, Losing interest, and feeling Slowed down, sluggish, or sedated) screening tool is used to detect prescription medication OUD and has 4 questions10:

1. In the past 3 months did you use your opioid medicines for other purposes—for example, to help you sleep or to help with stress or worry?

2. In the past 3 months did opioid medicines cause you to feel slowed down, sluggish, or sedated?

3. In the past 3 months did opioid medicines cause you to lose interest in your usual activities?

4. In the past 3 months did you worry about your use of opioid medicines?

Patient agreement with 3 or 4 questions indicates a positive screening test.

If the patient has a positive screening test, a formal diagnosis of OUD can be made using the 11 symptoms outlined in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition.11 The diagnosis of mild (2 to 3 symptoms), moderate (4 to 5 symptoms), or severe OUD (6 or more symptoms) is made based on the number of symptoms the patient reports.

Buprenorphine treatment of OUD in primary care

The role of primary care clinicians in the medication treatment of OUD is increasing. Using a nationwide system that tracks prescription medications, investigators reported that, in 2004, psychiatrists wrote 32.2% of all BUP prescriptions; in 2021, however, only 10% of such prescriptions were provided by psychiatrists, with most prescriptions written by non-psychiatrist physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants that year.12 Innovative telehealth approaches to consultation and medication treatment of OUD are now available—one example is QuickMD.13 Such sites are designed to remove barriers to initiating medication treatment of OUD.

The role of primary care clinicians in the management of OUD using BUP and buprenorphine-naloxone (BUP-NAL) has increased due to many factors, including:

- the removal of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) barriers to prescribing BUP

- the epidemic of OUD and the small size of the addiction specialist workforce, necessitating that primary care clinicians become engaged in the treatment of OUD

- an increase in unobserved initiation of BUP among ambulatory patients, and a parallel decrease in cases of observed initiation in addiction center settings

- the reframing of OUD as a chronic medical problem, with many similarities to diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.

Similar to other diseases managed by primary care clinicians, OUD requires long-term chronic treatment with a medicine that, if taken as directed, provides excellent outcomes. Primary care clinicians who prescribe BUP also can optimize longitudinal care for comorbid disorders such as hypertension and diabetes, which are prevalent in people with OUD.

In 2019, New Jersey implemented new guidelines for the treatment of OUD, removing prior authorization barriers, increasing reimbursement for office-based OUD treatment, and establishing regional centers of excellence. The implementation of the new guidelines was followed by a marked increase in BUP prescribers among primary care clinicians, emergency medicine physicians, and advanced practice clinicians.14

To estimate the public health impact of BUP prescribing by primary care clinicians, investigators simulated patient outcomes in 3 scenarios15:

1. primary care clinicians refer patients to addiction specialists for OUD treatment

2. primary care clinicians provide BUP services in their practice

3. primary care clinicians provide BUP and harm reduction kits containing syringes and wound care supplies in their practice.

Strategies 2 and 3 resulted in 14% fewer deaths due to opioid overdose, an increased life expectancy of approximately 2.7 years, and reduced hospital costs. For strategy 3, the incremental cost per life-year saved was $34,400. The investigators noted that prescribing BUP in primary care practice increases practice costs.15

Treatment with BUP reduces death from opioid overdose, improves patient health, decreases use of illicit opioids, and reduces patient cravings for opioids. BUP is a safe medication and is associated with fewer adverse effects than insulin or warfarin.16

Continue to: Methadone treatment of OUD...

Methadone treatment of OUD

Methadone is a full opioid agonist approved by the FDA for the treatment of severe pain or OUD. Methadone treatment of OUD is strictly regulated and typically is ordered and administered at an opioid treatment program that is federally licensed. Methadone for OUD treatment cannot be prescribed by a physician to a pharmacy, limiting its use in primary care practice. Methadone used to treat OUD is ordered and dispensed at opioid-treatment programs. Take-home doses of methadone may be available to patients after adherence to the regimen has been established. When used long-term, higher doses of methadone are associated with better adherence, but these higher doses can cause respiratory depression. In a study of 189 pregnant patients taking methadone to treat OUD, daily doses of 60 mg or greater were associated with better treatment retention at delivery and 60 days postpartum, as well as less use of nonprescription opioids.17 Under limited circumstances methadone can be ordered and dispensed for hospitalized patients with OUD.

Methadone is a pure opioid receptor agonist. Naloxone (NAL) is an opioid receptor antagonist. Buprenorphine (BUP) is a partial opioid receptor agonist-antagonist, which limits overdose risk. BUP often is combined with NAL as a combination formulation, which is thought to reduce the repurposing of BUP for non-prescribed uses. At appropriate treatment dosages, both methadone (≥60 mg) and BUP (≥ 16 mg) are highly effective for the treatment of OUD.1 For patients with health insurance, pharmacy benefits often provide some coverage for preferred products but no coverage for other products. Not all pharmacies carry BUP products. In a study of more than 5,000 pharmacies, approximately 60% reported that they carry and can dispense BUP medications.2

BUP monotherapy is available as generic sublingual tablets, buccal films (Belbuca), formulations for injection (Sublocade), and subcutaneous implants (Probuphine). BUPNAL is available as buccal films (Bunavail), sublingual films (Suboxone), and sublingual tablets (Zubsolv). For BUP-NAL combination productions, the following dose combinations have been reported to have similar effects: BUP-NAL 8 mg/2 mg sublingual film, BUP-NAL 5.7 mg/1.4 mg sublingual tablet, and BUP-NAL 4.2 mg/0.7 mg buccal film.3

When initiating BUP-monotherapy or BUP-NAL treatment for OUD, one approach for unobserved initiation is to instruct the patient to discontinue using opioid agonist drugs and wait for the onset of mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms. The purpose of this step is to avoid precipitating severe withdrawal symptoms caused by giving BUP or BUP-NAL to a patient who has recently used opioid drugs.

If BUP-NAL sublingual films (Suboxone) are prescribed following the onset of mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms, the patient can initiate therapy with a dose of 2 mg BUP/0.5 mg NAL or 4 mg BUP/1 mg NAL. At 60 to 120 minutes following the initial dose, if withdrawal symptoms persist, an additional dose of 4 mg BUP/1 mg NAL can be given. Thereafter, symptoms can be assessed every 60 to 120 minutes and additional doses administered to control symptoms. On the second day of therapy, a maximum of 16 mg of BUP is administered. Over the following days and weeks, if symptoms and cravings persist at a BUP dose of 16 mg, the total daily dose of BUP can be titrated up to 24 mg. For long-term treatment, a commonly prescribed daily dose is 16 mg BUP/4 mg NAL or 24 mg BUP/6 mg NAL. An absolute contraindication to BUP or BUP/NAL treatment is an allergy to the medication, and a relative contraindication is liver failure.

One potential complication of transmucosal BUP or BUP-NAL treatment is a dry mouth (xerostomia), which may contribute to dental disease.4 However, some experts question the quality of the data that contributed to the warning.5,6 Potential dental complications might be prevented by regular oral health examinations, daily flossing and teeth brushing, and stimulation of saliva by sugar-free gum or lozenges.

Primary care clinicians who initiate BUP or BUPNAL treatment for OUD often have a weekly visit with the patient during the initial phase of treatment and then every 3 to 4 weeks during maintenance therapy. Most patients need long-term treatment to achieve the goals of therapy, which include prevention of opioid overdose, reduction of cravings for nonprescription narcotics, and improvement in overall health. BUP and BUP-NAL treatment are effective without formal counseling, but counseling and social work support improve long-term adherence with treatment. Primary care clinicians who have experience with medication treatment of OUD report that their experience convinces them that medication treatment of OUD has similarities to the long-term treatment of diabetes, with antihyperglycemia medicines or the treatment of HIV infection with antiviral medications.

References

1. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD002207.

2. Weiner SG, Qato DM, Faust JS, et al. Pharmacy availability of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder treatment in the U.S. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:E2316089.

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Medications for opioid use disorder. SAMHSA website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https ://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/PEP 21-02-01-002.pdf

4. FDA warns about dental problems with buprenorphine medicines dissolved in the mouth. FDA website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https ://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-about-dental-problems-buprenorphine-medicines-dissolved-mouth-treat-opioiduse-disorder#:~:text=What%20did%20FDA%20find%3F,medicines%20 dissolved%20in%20the%20mouth

5. Watson DP, Etmian S, Gastala N. Sublingual buprenorphine-naloxone exposure and dental disease. JAMA. 2023;329:1223-1224.

6. Brothers TD, Lewer D, Bonn M. Sublingual buprenorphine-naloxone exposure and dental disease. JAMA. 2023;329:1224.

Medication treatment of OUD in obstetrics

In the United States, the prevalence of OUD among pregnant patients hospitalized for delivery more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2014.18 BUP and methadone commonly are used to treat OUD during pregnancy.19 Among pregnant patients about 5% of buprenorphine prescriptions are written by obstetricians.20 An innovative approach to initiating BUP for pregnant patients with OUD is to use unobserved initiation, which involves outpatient discontinuation of nonprescription opioids to induce mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms followed by initiation of BUP treatment. In one cohort study, 55 pregnant patients used an unobserved outpatient protocol to initiate BUP treatment; 80% of the patients previously had used methadone or BUP. No patient experienced a precipitated withdrawal and 96% of patients returned for their office visit 1 week after initiation of treatment. Eighty-six percent of patients remained in treatment 3 months following initiation of BUP.21

Compared with methadone, BUP treatment during pregnancy may result in lower rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome. In one study of pregnant patients who were using methadone (n = 5,056) or BUP (n = 11,272) in late pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome was diagnosed in 69.2% and 52.0% of newborns, respectively (adjusted relative risk, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.71–0.75).22 In addition, compared with methadone, the use of BUP was associated with a reduced risk for low birth weight (14.9% vs 8.3%) and a lower risk for preterm birth (24.9% vs 14.4%). In this study, there were no differences in maternal obstetric outcomes when comparing BUP versus methadone treatment. Similar results have been reported in a meta-analysis analyzing the use of methadone and BUP during pregnancy.23 Studies performed to date have not shown an increased risk of congenital anomalies with the use of BUP-NAL during pregnancy.24,25

Although there may be differences in newborn outcomes with BUP and methadone, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend switching from methadone to BUP during pregnancy because precipitated withdrawal may occur.26 Based on recent studies, the American Society of Addiction Medicine has advised that it is safe to prescribe pregnant patients either BUP or BUP-NAL.27,28

Medication treatment of OUD with or without intensive counseling

The FDA recently reviewed literature related to the advantages and challenges of combining intensive counseling with medication treatment of OUD.29 The FDA noted that treatment saves lives and encouraged clinicians to initiate medication treatment of OUD or refer the patient to an appropriate clinician or treatment center. Combining medication treatment of OUD with intensive counseling is associated with greater treatment adherence and reduced health care costs. For example, in one study of 4,987 patients with OUD, initiation of counseling within 8 weeks of the start of medication treatment and a BUP dose of 16 mg or greater daily were associated with increased adherence to treatment.30 For patients receiving a BUP dose of less than 16 mg daily, treatment adherence with and without counseling was approximately 325 and 230 days, respectively. When the dose of BUP was 16 mg or greater, treatment adherence with and without counseling was approximately 405 and 320 days, respectively.30

Counseling should always be offered to patients initiating medication treatment of OUD. It should be noted that counseling alone is not a highly effective treatment for OUD.31 The FDA recently advised that the lack of availability of intensive counseling should not prevent clinicians from initiating BUP for the treatment of OUD.29 OUD is associated with a high mortalityrate and if counseling is not possible, medication treatment should be initiated. Substantial evidence demonstrates that medication treatment of OUD is associated with many benefits.16 The FDA advisory committee concluded that OUD treatment decisions should use shared decision making and be supportive and patient centered.29

The opportunities for medication treatment of OUD in primary care practice have expanded due to the recent FDA removal of restrictions on the use of BUP and heightened awareness of the positive public health impact of medication treatment. Challenges to the medication treatment of OUD remain, including stigmatization of OUD, barriers to insurance coverage for BUP, practice costs of treating OUD, and gaps in clinical education. For many pregnant patients, their main point of contact with health care is their obstetrician. By incorporating OUD treatment in pregnancy care, obstetricians will improve the health of the mother and newborn, contributing to the well-being of current and future generations. ●

Experts have recommended several interventions that may help reduce opioid overdose death.1 A consensus recommendation is that people who use drugs should be provided naloxone rescue medication and educated on the proper use of naloxone. Naloxone rescue medication is available in formulations for nasal or parenteral administration. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently has approved naloxone for over-the-counter status. The American Medical Association has provided a short web video on how to administer nasal naloxone.2 In a small pilot study, obstetricians offered every postpartum patient with naloxone administration education and a 2-dose nasal naloxone pack, with 76% of patients accepting the nasal naloxone pack.3

Many experts recommend that people who use drugs should be advised to never use them alone and to test a small amount of the drug to assess its potency. Many patients who use opioid drugs also take benzodiazepines, which can contribute to respiratory depression.4 Patients should avoid mixing drugs (eg, opioids and benzodiazepines). Some experts recommend that patients who use drugs should be provided take-home fentanyl test strips so they can evaluate their drugs for the presence of fentanyl, a medication that suppresses respiration and contributes to many overdose deaths. In addition, people who use drugs and are interested in reducing their use of drugs or managing overdose risk can be offered initiation of medication treatment of OUD.1

References

1. Wood E, Solomon ED, Hadland SE. Universal precautions for people at risk of opioid overdose in North America. JAMA Int Med. 2023;183:401-402.

2. How to administer Naloxone. AMA website. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org /delivering-care/overdose-epidemic/how-administer-naloxone

3. Naliboff JA, Tharpe N. Universal postpartum naloxone provision: a harm reduction quality improvement project. J Addict Med. 2022;17:360-362.

4. Kelly JC, Raghuraman N, Stout MJ, et al. Home induction of buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:655-659.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 106,699 deaths in 2021 from drug overdose, with the majority being linked to synthetic opioids, including fentanyl and tramadol.1 This number compares with 42,795 deaths due to motor vehicle accidents and 48,183 deaths due to suicide in 2021.2,3 Most of the opioid overdose deaths occurred among people aged 25 to 64 years, the peak age of patients cared for by obstetrician-gynecologists. Among pregnant and postpartum persons, mortality due to drug overdose has increased by 81% between 2017 and 2020.4

Among pregnant and postpartum patients, drug overdose death is more common than suicide, and the risk for drug overdose death appears to be greatest in the year following delivery.5,6 In many cases, postpartum patients with OUD have had multiple contacts with the health care system prior to their death, showing that there is an opportunity for therapeutic intervention before the death occurred.7 Medication-assisted recovery for OUD involves a comprehensive array of interventions including medication, counseling, and social support. Medication treatment of OUD with BUP or methadone reduces the risk for death but is underutilized among patients with OUD.6,8 Recent federal legislation has removed restrictions on the use of BUP, increasing the opportunity for primary care clinicians to prescribe it for the treatment of OUD.9

Screening and diagnosis of OUD

Screening for OUD is recommended for patients who are at risk for opioid misuse (ie, those who are taking/have taken opioid medications). The OWLS (Overuse, Worrying, Losing interest, and feeling Slowed down, sluggish, or sedated) screening tool is used to detect prescription medication OUD and has 4 questions10:

1. In the past 3 months did you use your opioid medicines for other purposes—for example, to help you sleep or to help with stress or worry?

2. In the past 3 months did opioid medicines cause you to feel slowed down, sluggish, or sedated?

3. In the past 3 months did opioid medicines cause you to lose interest in your usual activities?

4. In the past 3 months did you worry about your use of opioid medicines?

Patient agreement with 3 or 4 questions indicates a positive screening test.

If the patient has a positive screening test, a formal diagnosis of OUD can be made using the 11 symptoms outlined in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition.11 The diagnosis of mild (2 to 3 symptoms), moderate (4 to 5 symptoms), or severe OUD (6 or more symptoms) is made based on the number of symptoms the patient reports.

Buprenorphine treatment of OUD in primary care

The role of primary care clinicians in the medication treatment of OUD is increasing. Using a nationwide system that tracks prescription medications, investigators reported that, in 2004, psychiatrists wrote 32.2% of all BUP prescriptions; in 2021, however, only 10% of such prescriptions were provided by psychiatrists, with most prescriptions written by non-psychiatrist physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants that year.12 Innovative telehealth approaches to consultation and medication treatment of OUD are now available—one example is QuickMD.13 Such sites are designed to remove barriers to initiating medication treatment of OUD.

The role of primary care clinicians in the management of OUD using BUP and buprenorphine-naloxone (BUP-NAL) has increased due to many factors, including:

- the removal of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) barriers to prescribing BUP

- the epidemic of OUD and the small size of the addiction specialist workforce, necessitating that primary care clinicians become engaged in the treatment of OUD

- an increase in unobserved initiation of BUP among ambulatory patients, and a parallel decrease in cases of observed initiation in addiction center settings

- the reframing of OUD as a chronic medical problem, with many similarities to diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.

Similar to other diseases managed by primary care clinicians, OUD requires long-term chronic treatment with a medicine that, if taken as directed, provides excellent outcomes. Primary care clinicians who prescribe BUP also can optimize longitudinal care for comorbid disorders such as hypertension and diabetes, which are prevalent in people with OUD.

In 2019, New Jersey implemented new guidelines for the treatment of OUD, removing prior authorization barriers, increasing reimbursement for office-based OUD treatment, and establishing regional centers of excellence. The implementation of the new guidelines was followed by a marked increase in BUP prescribers among primary care clinicians, emergency medicine physicians, and advanced practice clinicians.14

To estimate the public health impact of BUP prescribing by primary care clinicians, investigators simulated patient outcomes in 3 scenarios15:

1. primary care clinicians refer patients to addiction specialists for OUD treatment

2. primary care clinicians provide BUP services in their practice

3. primary care clinicians provide BUP and harm reduction kits containing syringes and wound care supplies in their practice.

Strategies 2 and 3 resulted in 14% fewer deaths due to opioid overdose, an increased life expectancy of approximately 2.7 years, and reduced hospital costs. For strategy 3, the incremental cost per life-year saved was $34,400. The investigators noted that prescribing BUP in primary care practice increases practice costs.15

Treatment with BUP reduces death from opioid overdose, improves patient health, decreases use of illicit opioids, and reduces patient cravings for opioids. BUP is a safe medication and is associated with fewer adverse effects than insulin or warfarin.16

Continue to: Methadone treatment of OUD...

Methadone treatment of OUD

Methadone is a full opioid agonist approved by the FDA for the treatment of severe pain or OUD. Methadone treatment of OUD is strictly regulated and typically is ordered and administered at an opioid treatment program that is federally licensed. Methadone for OUD treatment cannot be prescribed by a physician to a pharmacy, limiting its use in primary care practice. Methadone used to treat OUD is ordered and dispensed at opioid-treatment programs. Take-home doses of methadone may be available to patients after adherence to the regimen has been established. When used long-term, higher doses of methadone are associated with better adherence, but these higher doses can cause respiratory depression. In a study of 189 pregnant patients taking methadone to treat OUD, daily doses of 60 mg or greater were associated with better treatment retention at delivery and 60 days postpartum, as well as less use of nonprescription opioids.17 Under limited circumstances methadone can be ordered and dispensed for hospitalized patients with OUD.

Methadone is a pure opioid receptor agonist. Naloxone (NAL) is an opioid receptor antagonist. Buprenorphine (BUP) is a partial opioid receptor agonist-antagonist, which limits overdose risk. BUP often is combined with NAL as a combination formulation, which is thought to reduce the repurposing of BUP for non-prescribed uses. At appropriate treatment dosages, both methadone (≥60 mg) and BUP (≥ 16 mg) are highly effective for the treatment of OUD.1 For patients with health insurance, pharmacy benefits often provide some coverage for preferred products but no coverage for other products. Not all pharmacies carry BUP products. In a study of more than 5,000 pharmacies, approximately 60% reported that they carry and can dispense BUP medications.2

BUP monotherapy is available as generic sublingual tablets, buccal films (Belbuca), formulations for injection (Sublocade), and subcutaneous implants (Probuphine). BUPNAL is available as buccal films (Bunavail), sublingual films (Suboxone), and sublingual tablets (Zubsolv). For BUP-NAL combination productions, the following dose combinations have been reported to have similar effects: BUP-NAL 8 mg/2 mg sublingual film, BUP-NAL 5.7 mg/1.4 mg sublingual tablet, and BUP-NAL 4.2 mg/0.7 mg buccal film.3

When initiating BUP-monotherapy or BUP-NAL treatment for OUD, one approach for unobserved initiation is to instruct the patient to discontinue using opioid agonist drugs and wait for the onset of mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms. The purpose of this step is to avoid precipitating severe withdrawal symptoms caused by giving BUP or BUP-NAL to a patient who has recently used opioid drugs.

If BUP-NAL sublingual films (Suboxone) are prescribed following the onset of mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms, the patient can initiate therapy with a dose of 2 mg BUP/0.5 mg NAL or 4 mg BUP/1 mg NAL. At 60 to 120 minutes following the initial dose, if withdrawal symptoms persist, an additional dose of 4 mg BUP/1 mg NAL can be given. Thereafter, symptoms can be assessed every 60 to 120 minutes and additional doses administered to control symptoms. On the second day of therapy, a maximum of 16 mg of BUP is administered. Over the following days and weeks, if symptoms and cravings persist at a BUP dose of 16 mg, the total daily dose of BUP can be titrated up to 24 mg. For long-term treatment, a commonly prescribed daily dose is 16 mg BUP/4 mg NAL or 24 mg BUP/6 mg NAL. An absolute contraindication to BUP or BUP/NAL treatment is an allergy to the medication, and a relative contraindication is liver failure.

One potential complication of transmucosal BUP or BUP-NAL treatment is a dry mouth (xerostomia), which may contribute to dental disease.4 However, some experts question the quality of the data that contributed to the warning.5,6 Potential dental complications might be prevented by regular oral health examinations, daily flossing and teeth brushing, and stimulation of saliva by sugar-free gum or lozenges.

Primary care clinicians who initiate BUP or BUPNAL treatment for OUD often have a weekly visit with the patient during the initial phase of treatment and then every 3 to 4 weeks during maintenance therapy. Most patients need long-term treatment to achieve the goals of therapy, which include prevention of opioid overdose, reduction of cravings for nonprescription narcotics, and improvement in overall health. BUP and BUP-NAL treatment are effective without formal counseling, but counseling and social work support improve long-term adherence with treatment. Primary care clinicians who have experience with medication treatment of OUD report that their experience convinces them that medication treatment of OUD has similarities to the long-term treatment of diabetes, with antihyperglycemia medicines or the treatment of HIV infection with antiviral medications.

References

1. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD002207.

2. Weiner SG, Qato DM, Faust JS, et al. Pharmacy availability of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder treatment in the U.S. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:E2316089.

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Medications for opioid use disorder. SAMHSA website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https ://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/PEP 21-02-01-002.pdf

4. FDA warns about dental problems with buprenorphine medicines dissolved in the mouth. FDA website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https ://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-warns-about-dental-problems-buprenorphine-medicines-dissolved-mouth-treat-opioiduse-disorder#:~:text=What%20did%20FDA%20find%3F,medicines%20 dissolved%20in%20the%20mouth

5. Watson DP, Etmian S, Gastala N. Sublingual buprenorphine-naloxone exposure and dental disease. JAMA. 2023;329:1223-1224.

6. Brothers TD, Lewer D, Bonn M. Sublingual buprenorphine-naloxone exposure and dental disease. JAMA. 2023;329:1224.

Medication treatment of OUD in obstetrics

In the United States, the prevalence of OUD among pregnant patients hospitalized for delivery more than quadrupled from 1999 through 2014.18 BUP and methadone commonly are used to treat OUD during pregnancy.19 Among pregnant patients about 5% of buprenorphine prescriptions are written by obstetricians.20 An innovative approach to initiating BUP for pregnant patients with OUD is to use unobserved initiation, which involves outpatient discontinuation of nonprescription opioids to induce mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms followed by initiation of BUP treatment. In one cohort study, 55 pregnant patients used an unobserved outpatient protocol to initiate BUP treatment; 80% of the patients previously had used methadone or BUP. No patient experienced a precipitated withdrawal and 96% of patients returned for their office visit 1 week after initiation of treatment. Eighty-six percent of patients remained in treatment 3 months following initiation of BUP.21

Compared with methadone, BUP treatment during pregnancy may result in lower rates of neonatal abstinence syndrome. In one study of pregnant patients who were using methadone (n = 5,056) or BUP (n = 11,272) in late pregnancy, neonatal abstinence syndrome was diagnosed in 69.2% and 52.0% of newborns, respectively (adjusted relative risk, 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.71–0.75).22 In addition, compared with methadone, the use of BUP was associated with a reduced risk for low birth weight (14.9% vs 8.3%) and a lower risk for preterm birth (24.9% vs 14.4%). In this study, there were no differences in maternal obstetric outcomes when comparing BUP versus methadone treatment. Similar results have been reported in a meta-analysis analyzing the use of methadone and BUP during pregnancy.23 Studies performed to date have not shown an increased risk of congenital anomalies with the use of BUP-NAL during pregnancy.24,25

Although there may be differences in newborn outcomes with BUP and methadone, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists does not recommend switching from methadone to BUP during pregnancy because precipitated withdrawal may occur.26 Based on recent studies, the American Society of Addiction Medicine has advised that it is safe to prescribe pregnant patients either BUP or BUP-NAL.27,28

Medication treatment of OUD with or without intensive counseling

The FDA recently reviewed literature related to the advantages and challenges of combining intensive counseling with medication treatment of OUD.29 The FDA noted that treatment saves lives and encouraged clinicians to initiate medication treatment of OUD or refer the patient to an appropriate clinician or treatment center. Combining medication treatment of OUD with intensive counseling is associated with greater treatment adherence and reduced health care costs. For example, in one study of 4,987 patients with OUD, initiation of counseling within 8 weeks of the start of medication treatment and a BUP dose of 16 mg or greater daily were associated with increased adherence to treatment.30 For patients receiving a BUP dose of less than 16 mg daily, treatment adherence with and without counseling was approximately 325 and 230 days, respectively. When the dose of BUP was 16 mg or greater, treatment adherence with and without counseling was approximately 405 and 320 days, respectively.30

Counseling should always be offered to patients initiating medication treatment of OUD. It should be noted that counseling alone is not a highly effective treatment for OUD.31 The FDA recently advised that the lack of availability of intensive counseling should not prevent clinicians from initiating BUP for the treatment of OUD.29 OUD is associated with a high mortalityrate and if counseling is not possible, medication treatment should be initiated. Substantial evidence demonstrates that medication treatment of OUD is associated with many benefits.16 The FDA advisory committee concluded that OUD treatment decisions should use shared decision making and be supportive and patient centered.29

The opportunities for medication treatment of OUD in primary care practice have expanded due to the recent FDA removal of restrictions on the use of BUP and heightened awareness of the positive public health impact of medication treatment. Challenges to the medication treatment of OUD remain, including stigmatization of OUD, barriers to insurance coverage for BUP, practice costs of treating OUD, and gaps in clinical education. For many pregnant patients, their main point of contact with health care is their obstetrician. By incorporating OUD treatment in pregnancy care, obstetricians will improve the health of the mother and newborn, contributing to the well-being of current and future generations. ●

Experts have recommended several interventions that may help reduce opioid overdose death.1 A consensus recommendation is that people who use drugs should be provided naloxone rescue medication and educated on the proper use of naloxone. Naloxone rescue medication is available in formulations for nasal or parenteral administration. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently has approved naloxone for over-the-counter status. The American Medical Association has provided a short web video on how to administer nasal naloxone.2 In a small pilot study, obstetricians offered every postpartum patient with naloxone administration education and a 2-dose nasal naloxone pack, with 76% of patients accepting the nasal naloxone pack.3

Many experts recommend that people who use drugs should be advised to never use them alone and to test a small amount of the drug to assess its potency. Many patients who use opioid drugs also take benzodiazepines, which can contribute to respiratory depression.4 Patients should avoid mixing drugs (eg, opioids and benzodiazepines). Some experts recommend that patients who use drugs should be provided take-home fentanyl test strips so they can evaluate their drugs for the presence of fentanyl, a medication that suppresses respiration and contributes to many overdose deaths. In addition, people who use drugs and are interested in reducing their use of drugs or managing overdose risk can be offered initiation of medication treatment of OUD.1

References

1. Wood E, Solomon ED, Hadland SE. Universal precautions for people at risk of opioid overdose in North America. JAMA Int Med. 2023;183:401-402.

2. How to administer Naloxone. AMA website. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org /delivering-care/overdose-epidemic/how-administer-naloxone

3. Naliboff JA, Tharpe N. Universal postpartum naloxone provision: a harm reduction quality improvement project. J Addict Med. 2022;17:360-362.

4. Kelly JC, Raghuraman N, Stout MJ, et al. Home induction of buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:655-659.

- Spencer MR, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 20012021. NCHS Data Brief no 457. Hyattsville, MD, National Center for Health Statistics. 2022. NCHS Data Brief No. 457. Published December 2022. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov /nchs/products/databriefs/db457.htm

- US traffic deaths drop slightly in 2022 but still a ‘crisis.’ AP News website. Published April 20, 2023. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://apnews.com /article/traffic-deaths-distracted-driving-crisis -6db6471e273b275920b6c4f9eb7e493b

- Suicide statistics. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://afsp.org/suicide-statistics/

- Bruzelius E, Martins SS. US Trends in drug overdose mortality among pregnant and postpartum persons, 2017-2020. JAMA. 2022;328:2159-2161.

- Metz TD, Rovner P, Hoffman MC, et al. Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose in Colorado, 2004-2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1233-1240.

- Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Terplan M, et al. Fatal and nonfatal overdose among pregnant and postpartum women in Massachusetts. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:466-474.

- Goldman-Mellor S, Margerison CE. Maternal drug-related death and suicide are leading causes of postpartum death in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:489.e1-489.e9.

- Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550.

- Waiver elimination (MAT Act). SAMHSA website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www .samhsa.gov/medications-substance-use- disorders/removal-data-waiver-requirement

- Picco L, Middleton M, Bruno R, et al. Validation of the OWLS, a Screening Tool for Measuring Prescription Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care. Pain Med. 2020;21:2757-2764.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Creedon TB, Ali MM, Schuman-Olivier Z. Trends in buprenorphine prescribing for opioid use disorder by psychiatrists in the US from 2003 to 2021. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4:E230221.

- Quick MD website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://quick.md/

- Treitler P, Nowels M, Samples H, et al. BUP utilization and prescribing among New Jersey Medicaid beneficiaries after adoption of initiatives designed to improve treatment access. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:E2312030.

- Jawa R, Tin Y, Nall S, et al. Estimated clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness associated with provision of addiction treatment in US primary care clinics. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:E237888.

- Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways of opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:E1920622.

- Wilder CM, Hosta D, Winhusen T. Association of methadone dose with substance use and treatment retention in pregnant and postpartum women with opioid use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;80:33-36.

- Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, et al. Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization - United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:845-849.

- Xu KY, Jones HE, Schiff DM, et al. Initiation and treatment discontinuation of medications for opioid use disorder in pregnant people compared with nonpregnant people. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:845-853.

- Kelly D, Krans EE. Medical specialty of buprenorphine prescribers for pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:502-503.

- Kelly JC, Raghuraman N, Stout MJ, et al. Home induction of buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:655-659.

- Suarez EA, Huybrechts KF, Straub L, et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone for opioid use disorder in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2033-2044.

- Kinsella M, Halliday LO, Shaw M, et al. Buprenorphine compared with methadone in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57:1400-1416.

- Jumah NA, Edwards C, Balfour-Boehm J, et al. Observational study of the safety of buprenorphine-naloxone in pregnancy in a rural and remote population. BMJ Open. 2016;6:E011774.

- Mullins N, Galvin SL, Ramage M, et al. Buprenorphine and naloxone versus buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in pregnancy: a cohort study. J Addict Med. 2020;14:185-192.

- Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 711. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:E81-E94.

- The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2S suppl 1):1-91.

- Link HM, Jones H, Miller L, et al. Buprenorphinenaloxone use in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100179.

- Delphin-Rittmon ME, Cavazzoni P. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda .gov/media/168027/download

- Eren K, Schuster J, Herschell A, et al. Association of Counseling and Psychotherapy on retention in medication for addiction treatment within a large Medicaid population. J Addict Med. 2022;16:346353.

- Kakko J, Dybrandt Svanborg K, Kreek MJ, et al. 1-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:662-668.

- Spencer MR, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 20012021. NCHS Data Brief no 457. Hyattsville, MD, National Center for Health Statistics. 2022. NCHS Data Brief No. 457. Published December 2022. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov /nchs/products/databriefs/db457.htm

- US traffic deaths drop slightly in 2022 but still a ‘crisis.’ AP News website. Published April 20, 2023. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://apnews.com /article/traffic-deaths-distracted-driving-crisis -6db6471e273b275920b6c4f9eb7e493b

- Suicide statistics. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://afsp.org/suicide-statistics/

- Bruzelius E, Martins SS. US Trends in drug overdose mortality among pregnant and postpartum persons, 2017-2020. JAMA. 2022;328:2159-2161.

- Metz TD, Rovner P, Hoffman MC, et al. Maternal deaths from suicide and overdose in Colorado, 2004-2012. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1233-1240.

- Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Terplan M, et al. Fatal and nonfatal overdose among pregnant and postpartum women in Massachusetts. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:466-474.

- Goldman-Mellor S, Margerison CE. Maternal drug-related death and suicide are leading causes of postpartum death in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:489.e1-489.e9.

- Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550.

- Waiver elimination (MAT Act). SAMHSA website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www .samhsa.gov/medications-substance-use- disorders/removal-data-waiver-requirement

- Picco L, Middleton M, Bruno R, et al. Validation of the OWLS, a Screening Tool for Measuring Prescription Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care. Pain Med. 2020;21:2757-2764.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Creedon TB, Ali MM, Schuman-Olivier Z. Trends in buprenorphine prescribing for opioid use disorder by psychiatrists in the US from 2003 to 2021. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4:E230221.

- Quick MD website. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://quick.md/

- Treitler P, Nowels M, Samples H, et al. BUP utilization and prescribing among New Jersey Medicaid beneficiaries after adoption of initiatives designed to improve treatment access. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:E2312030.

- Jawa R, Tin Y, Nall S, et al. Estimated clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness associated with provision of addiction treatment in US primary care clinics. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:E237888.

- Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different treatment pathways of opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:E1920622.

- Wilder CM, Hosta D, Winhusen T. Association of methadone dose with substance use and treatment retention in pregnant and postpartum women with opioid use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;80:33-36.

- Haight SC, Ko JY, Tong VT, et al. Opioid use disorder documented at delivery hospitalization - United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:845-849.

- Xu KY, Jones HE, Schiff DM, et al. Initiation and treatment discontinuation of medications for opioid use disorder in pregnant people compared with nonpregnant people. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:845-853.

- Kelly D, Krans EE. Medical specialty of buprenorphine prescribers for pregnant women with opioid use disorder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:502-503.

- Kelly JC, Raghuraman N, Stout MJ, et al. Home induction of buprenorphine for treatment of opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:655-659.

- Suarez EA, Huybrechts KF, Straub L, et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone for opioid use disorder in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2033-2044.

- Kinsella M, Halliday LO, Shaw M, et al. Buprenorphine compared with methadone in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57:1400-1416.

- Jumah NA, Edwards C, Balfour-Boehm J, et al. Observational study of the safety of buprenorphine-naloxone in pregnancy in a rural and remote population. BMJ Open. 2016;6:E011774.

- Mullins N, Galvin SL, Ramage M, et al. Buprenorphine and naloxone versus buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in pregnancy: a cohort study. J Addict Med. 2020;14:185-192.

- Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Committee Opinion No. 711. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:E81-E94.

- The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2S suppl 1):1-91.

- Link HM, Jones H, Miller L, et al. Buprenorphinenaloxone use in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2:100179.

- Delphin-Rittmon ME, Cavazzoni P. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda .gov/media/168027/download

- Eren K, Schuster J, Herschell A, et al. Association of Counseling and Psychotherapy on retention in medication for addiction treatment within a large Medicaid population. J Addict Med. 2022;16:346353.

- Kakko J, Dybrandt Svanborg K, Kreek MJ, et al. 1-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:662-668.

Thoughts on the CDC update on opioid prescribing guidelines

The media is filled with stories about the opioid crisis. We have all heard the horror stories of addiction and overdose, as well as “pill mill” doctors. In fact, more than 932,000 people have died of drug overdose since 1999 and, in recent years, approximately 75% of drug overdoses involved opioids.

Yet, they still have their place in the treatment of pain.

The CDC updated the 2016 guidelines for prescribing opioids for pain in 2022. They cover when to initiate prescribing of opioids, selecting appropriate opioids and doses, and deciding the duration of therapy. The guidelines do a great job providing evidence-based recommendations while at the same time keeping the problems with opioids in the picture.

For primary care doctors, pain is one of the most common complaints we see – from broken bones to low back pain to cancer pain. It is important to note that the current guidelines exclude pain from sickle cell disease, cancer-related pain, palliative care, and end-of-life care. The guidelines apply to acute, subacute, and chronic pain. Pain is a complex symptom and often needs a multipronged approach. We make a mistake if we just prescribe a pain medication without understanding the root cause of the pain.

The guidelines suggest starting with nonopioid medications and incorporating nonmedicinal modes of treatments, such as physical therapy, as well. Opioids should be started at the lowest dose and for the shortest duration. Immediate-release medications are preferred over long-acting or extended-release ones. The patient should always be informed of the risks and benefits.

While the guidelines do a great job recommending how to prescribe opioids, they do not go into any depth discussing other treatment options. Perhaps knowledge of other treatment modalities would help primary care physicians avoid opioid prescribing. When treating our patients, it is important to educate them on how to manage their own symptoms.

The guidelines also advise tapering patients who may have been on high-dose opioids for long periods of time. Doctors know this is a very difficult task. However, resources to help with this are often lacking. For example, rehab may not be covered under a patient’s insurance, or it may be cheaper to take an opioid than to go to physical therapy. Although the recommendation is to taper, community assets may not support this. Guidelines are one thing, but the rest of the health care system needs to catch up to them and make them practical.

Primary care doctors often utilize our physical medicine, rehabilitation, and pain management specialists to assist in managing our patients’ pain. Here too, access to this resource is often difficult to come by. Depending on a patient’s insurance, it can take months to get an appointment.

In general, the current guidelines offer 12 key recommendations when prescribing opioids. They are a great reference; however, we need more real-life tools. For many of us in primary care, these guidelines support what we’ve been doing all along.

Primary care doctors will surely play a huge role in addressing the opioid crisis. We can prescribe opioids appropriately, but it doesn’t erase the problems of those patients who were overprescribed in the past. Many still seek out these medications whether for monetary reasons or just for the high. It is often easy to blame the patient but the one in control is the one with the prescription pad. Yet, it is important to remember that many of these patients are in real pain and need help.

Often, it is simpler to just prescribe a pain medication than it is to explain why one is not appropriate. As primary care doctors, we need to be effective ambassadors of appropriate opioid prescribing and often that means doing the hard thing and saying no to a patient.

Dr. Girgis practices family medicine in South River, N.J., and is a clinical assistant professor of family medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

fpnews@mdedge.com

The media is filled with stories about the opioid crisis. We have all heard the horror stories of addiction and overdose, as well as “pill mill” doctors. In fact, more than 932,000 people have died of drug overdose since 1999 and, in recent years, approximately 75% of drug overdoses involved opioids.

Yet, they still have their place in the treatment of pain.

The CDC updated the 2016 guidelines for prescribing opioids for pain in 2022. They cover when to initiate prescribing of opioids, selecting appropriate opioids and doses, and deciding the duration of therapy. The guidelines do a great job providing evidence-based recommendations while at the same time keeping the problems with opioids in the picture.

For primary care doctors, pain is one of the most common complaints we see – from broken bones to low back pain to cancer pain. It is important to note that the current guidelines exclude pain from sickle cell disease, cancer-related pain, palliative care, and end-of-life care. The guidelines apply to acute, subacute, and chronic pain. Pain is a complex symptom and often needs a multipronged approach. We make a mistake if we just prescribe a pain medication without understanding the root cause of the pain.

The guidelines suggest starting with nonopioid medications and incorporating nonmedicinal modes of treatments, such as physical therapy, as well. Opioids should be started at the lowest dose and for the shortest duration. Immediate-release medications are preferred over long-acting or extended-release ones. The patient should always be informed of the risks and benefits.