User login

Consider drug holidays for BCC patients on hedgehog inhibitors

KAUAI, HAWAII – according to Kishwer Nehal, MD, director of Mohs micrographic and dermatologic surgery at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

That’s important because, although some patients have a good response to vismodegib, more – about 80% – have side effects that make it necessary to stop treatment, including muscle spasms and weight loss, among other problems. Side effects often come on quickly and can become intolerable after a few months of treatment, so physicians have looked for alternative dosing regimens to hold them off, with some success.

Compared with those on continuous dosing, fewer patients on intermittent dosing discontinued treatment for adverse events (23% versus 31%). Patients on intermittent dosing also experienced fewer grade 3 adverse events (31% versus 44%) and were on treatment for a longer period of time (a median of 71.4 weeks versus 37.6 weeks).

Meanwhile, among those on intermittent dosing, the number of BCCs was reduced in more than half of the patients in both interrupted treatment groups, but more so in the 12-weeks-on/8-weeks-off group (Lancet Oncol. 2017 Mar; 18[3]:404-12).

Other treatment options are being explored for vismodegib, as well as for sonidegib (Odomzo), another hedgehog signaling pathway inhibitor approved for advanced BCC. Ongoing trials are looking at the use of hedgehog inhibitors with radiation, and for shrinking tumors before surgery, Dr. Nehal said

For now, however, surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for BCC; both biologics are indicated for when other treatments fail or are not feasible. For high-risk BCC (meaning high risk for recurrence, based on infiltrative or poorly defined histology, perineural or bony involvement, or location on the face, for instance), “surgery with clear margins remains the goal and is the most effective treatment. For a high-risk [BCC], you pretty much need surgery,” she said.

Recurrence is less likely with Mohs surgery than with standard excision. When Mohs isn’t available, “you should wait for the pathology report before reconstruction,” she said.

“Radiation for high-risk [BCC] is really reserved for nonsurgical candidates,” Dr. Nehal commented. There are only two scenarios to consider radiation in high-risk BCC, “and they really have no proven benefit in any sort of prospective trial. One is if you cannot, after exhaustive surgery, clear your very high risk [BCC].” The other is if there is “really large nerve involvement, greater than 0.1 mm, or such extensive perineural involvement that surgery is unlikely to be successful,” she said.

Dr. Nehal had no relevant disclosures. SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – according to Kishwer Nehal, MD, director of Mohs micrographic and dermatologic surgery at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

That’s important because, although some patients have a good response to vismodegib, more – about 80% – have side effects that make it necessary to stop treatment, including muscle spasms and weight loss, among other problems. Side effects often come on quickly and can become intolerable after a few months of treatment, so physicians have looked for alternative dosing regimens to hold them off, with some success.

Compared with those on continuous dosing, fewer patients on intermittent dosing discontinued treatment for adverse events (23% versus 31%). Patients on intermittent dosing also experienced fewer grade 3 adverse events (31% versus 44%) and were on treatment for a longer period of time (a median of 71.4 weeks versus 37.6 weeks).

Meanwhile, among those on intermittent dosing, the number of BCCs was reduced in more than half of the patients in both interrupted treatment groups, but more so in the 12-weeks-on/8-weeks-off group (Lancet Oncol. 2017 Mar; 18[3]:404-12).

Other treatment options are being explored for vismodegib, as well as for sonidegib (Odomzo), another hedgehog signaling pathway inhibitor approved for advanced BCC. Ongoing trials are looking at the use of hedgehog inhibitors with radiation, and for shrinking tumors before surgery, Dr. Nehal said

For now, however, surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for BCC; both biologics are indicated for when other treatments fail or are not feasible. For high-risk BCC (meaning high risk for recurrence, based on infiltrative or poorly defined histology, perineural or bony involvement, or location on the face, for instance), “surgery with clear margins remains the goal and is the most effective treatment. For a high-risk [BCC], you pretty much need surgery,” she said.

Recurrence is less likely with Mohs surgery than with standard excision. When Mohs isn’t available, “you should wait for the pathology report before reconstruction,” she said.

“Radiation for high-risk [BCC] is really reserved for nonsurgical candidates,” Dr. Nehal commented. There are only two scenarios to consider radiation in high-risk BCC, “and they really have no proven benefit in any sort of prospective trial. One is if you cannot, after exhaustive surgery, clear your very high risk [BCC].” The other is if there is “really large nerve involvement, greater than 0.1 mm, or such extensive perineural involvement that surgery is unlikely to be successful,” she said.

Dr. Nehal had no relevant disclosures. SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – according to Kishwer Nehal, MD, director of Mohs micrographic and dermatologic surgery at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

That’s important because, although some patients have a good response to vismodegib, more – about 80% – have side effects that make it necessary to stop treatment, including muscle spasms and weight loss, among other problems. Side effects often come on quickly and can become intolerable after a few months of treatment, so physicians have looked for alternative dosing regimens to hold them off, with some success.

Compared with those on continuous dosing, fewer patients on intermittent dosing discontinued treatment for adverse events (23% versus 31%). Patients on intermittent dosing also experienced fewer grade 3 adverse events (31% versus 44%) and were on treatment for a longer period of time (a median of 71.4 weeks versus 37.6 weeks).

Meanwhile, among those on intermittent dosing, the number of BCCs was reduced in more than half of the patients in both interrupted treatment groups, but more so in the 12-weeks-on/8-weeks-off group (Lancet Oncol. 2017 Mar; 18[3]:404-12).

Other treatment options are being explored for vismodegib, as well as for sonidegib (Odomzo), another hedgehog signaling pathway inhibitor approved for advanced BCC. Ongoing trials are looking at the use of hedgehog inhibitors with radiation, and for shrinking tumors before surgery, Dr. Nehal said

For now, however, surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for BCC; both biologics are indicated for when other treatments fail or are not feasible. For high-risk BCC (meaning high risk for recurrence, based on infiltrative or poorly defined histology, perineural or bony involvement, or location on the face, for instance), “surgery with clear margins remains the goal and is the most effective treatment. For a high-risk [BCC], you pretty much need surgery,” she said.

Recurrence is less likely with Mohs surgery than with standard excision. When Mohs isn’t available, “you should wait for the pathology report before reconstruction,” she said.

“Radiation for high-risk [BCC] is really reserved for nonsurgical candidates,” Dr. Nehal commented. There are only two scenarios to consider radiation in high-risk BCC, “and they really have no proven benefit in any sort of prospective trial. One is if you cannot, after exhaustive surgery, clear your very high risk [BCC].” The other is if there is “really large nerve involvement, greater than 0.1 mm, or such extensive perineural involvement that surgery is unlikely to be successful,” she said.

Dr. Nehal had no relevant disclosures. SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

VIDEO: Bioimpedance provides accurate assessment of Mohs surgical margins

SAN DIEGO – In assessing tumor-free margins during Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer, of histologic sections, in a single-center, pilot study of bioimpedance in 151 specimens from 50 consecutive patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

If the finding of high diagnostic accuracy using bioimpedance spectroscopy is confirmed in larger numbers of patients and specimens run at multiple sites, this approach could “potentially revolutionize what happens with the way Mohs sections are processed in the future” by potentially shaving many minutes off the duration of a standard procedure, Darrell S. Rigel, MD, said in a video interview during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Usually, it takes 10-20 minutes to process and examine Mohs specimens at each stage of the surgical procedure to determine whether additional excision must remove residual cancer cells, said Dr. Rigel, a dermatologist at New York University. In contrast, assessment for residual cancer cells in the surgical field takes less than a minute using bioimpedance spectroscopy, which relies on differences in electrical conductivity between benign and cancerous cells to identify cancer cells remaining at the surgical margins.

The results of the study were presented in a poster at the meeting, by a research associate of Dr. Rigel’s, Ryan Svoboda, MD, of the National Society for Cutaneous Medicine, New York.

The researchers used a bioimpedance spectroscopy device made by NovaScan to assess 151 histology slides prepared during Mohs micrographic surgery on patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer, and compared the findings against the gold standard of histological slide examination. By this criterion, bioimpedance spectroscopy identified 105 true negatives and 2 false negatives, and 43 true positives and 1 false positive. Calculations showed that this equated to 95.6% sensitivity, 99.1% specificity, a 97.7% positive predictive value, and a 98.1% negative predictive value.

These may be underestimates of the accuracy of bioimpedance spectroscopy because the calculations presume that conventional histology is always correct, but Dr. Rigel noted that sometimes the histological diagnosis is wrong.

SOURCE: Svoboda R et al. Poster 7304.

SAN DIEGO – In assessing tumor-free margins during Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer, of histologic sections, in a single-center, pilot study of bioimpedance in 151 specimens from 50 consecutive patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

If the finding of high diagnostic accuracy using bioimpedance spectroscopy is confirmed in larger numbers of patients and specimens run at multiple sites, this approach could “potentially revolutionize what happens with the way Mohs sections are processed in the future” by potentially shaving many minutes off the duration of a standard procedure, Darrell S. Rigel, MD, said in a video interview during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Usually, it takes 10-20 minutes to process and examine Mohs specimens at each stage of the surgical procedure to determine whether additional excision must remove residual cancer cells, said Dr. Rigel, a dermatologist at New York University. In contrast, assessment for residual cancer cells in the surgical field takes less than a minute using bioimpedance spectroscopy, which relies on differences in electrical conductivity between benign and cancerous cells to identify cancer cells remaining at the surgical margins.

The results of the study were presented in a poster at the meeting, by a research associate of Dr. Rigel’s, Ryan Svoboda, MD, of the National Society for Cutaneous Medicine, New York.

The researchers used a bioimpedance spectroscopy device made by NovaScan to assess 151 histology slides prepared during Mohs micrographic surgery on patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer, and compared the findings against the gold standard of histological slide examination. By this criterion, bioimpedance spectroscopy identified 105 true negatives and 2 false negatives, and 43 true positives and 1 false positive. Calculations showed that this equated to 95.6% sensitivity, 99.1% specificity, a 97.7% positive predictive value, and a 98.1% negative predictive value.

These may be underestimates of the accuracy of bioimpedance spectroscopy because the calculations presume that conventional histology is always correct, but Dr. Rigel noted that sometimes the histological diagnosis is wrong.

SOURCE: Svoboda R et al. Poster 7304.

SAN DIEGO – In assessing tumor-free margins during Mohs micrographic surgery for skin cancer, of histologic sections, in a single-center, pilot study of bioimpedance in 151 specimens from 50 consecutive patients.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

If the finding of high diagnostic accuracy using bioimpedance spectroscopy is confirmed in larger numbers of patients and specimens run at multiple sites, this approach could “potentially revolutionize what happens with the way Mohs sections are processed in the future” by potentially shaving many minutes off the duration of a standard procedure, Darrell S. Rigel, MD, said in a video interview during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Usually, it takes 10-20 minutes to process and examine Mohs specimens at each stage of the surgical procedure to determine whether additional excision must remove residual cancer cells, said Dr. Rigel, a dermatologist at New York University. In contrast, assessment for residual cancer cells in the surgical field takes less than a minute using bioimpedance spectroscopy, which relies on differences in electrical conductivity between benign and cancerous cells to identify cancer cells remaining at the surgical margins.

The results of the study were presented in a poster at the meeting, by a research associate of Dr. Rigel’s, Ryan Svoboda, MD, of the National Society for Cutaneous Medicine, New York.

The researchers used a bioimpedance spectroscopy device made by NovaScan to assess 151 histology slides prepared during Mohs micrographic surgery on patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer, and compared the findings against the gold standard of histological slide examination. By this criterion, bioimpedance spectroscopy identified 105 true negatives and 2 false negatives, and 43 true positives and 1 false positive. Calculations showed that this equated to 95.6% sensitivity, 99.1% specificity, a 97.7% positive predictive value, and a 98.1% negative predictive value.

These may be underestimates of the accuracy of bioimpedance spectroscopy because the calculations presume that conventional histology is always correct, but Dr. Rigel noted that sometimes the histological diagnosis is wrong.

SOURCE: Svoboda R et al. Poster 7304.

REPORTING FROM AAD 18

Key clinical point: Bioimpedance spectroscopy showed excellent diagnostic accuracy for cancer cells on Mohs surgical margins.

Major finding: Bioimpedance spectroscopy had a sensitivity of 95.6% and specificity of 99.1% compared with Mohs histology.

Study details: A single-center pilot study with 151 Mohs surgical specimens taken from 50 patients.

Disclosures: The study was funded by NovaScan, the company developing the device tested in the study. Dr. Rigel has been a consultant to NovaScan and to Castle Biosciences, DermTech, Ferndale, Myriad, and Neutrogena, and has received research support from Castle and Neutrogena.

Source: Svoboda R et al. Poster 7304.

Evaluating Dermatology Apps for Patient Education

Study: Test for PD-L1 amplification in solid tumors

SAN FRANCISCO – Amplification of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), also known as cluster of differentiation 274 (CD274), is rare in most solid tumors, but findings from an analysis in which a majority of patients with the alteration experienced durable responses to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade suggest that testing for it may be warranted.

Of 117,344 deidentified cancer patient samples from a large database, only 0.7% had PD-L1 amplification, which was defined as 6 or more copy number alterations (CNAs). The CNAs were found across more than 100 tumor histologies, Aaron Goodman, MD, reported at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

Of a subset of 2,039 clinically annotated patients from the database, who were seen at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Center for Personalized Cancer Therapy, 13 (0.6%) had PD-L1 CNAs, and 9 were treated with immune checkpoint blockade, either alone or in combination with another immunotherapeutic or targeted therapy, after a median of four prior systemic therapies.

The PD-1/PD-L1 blockade response rate in those nine patients was 67%, and median progression-free survival was 15.2 months; three objective responses were ongoing for at least 15 months, said Dr. Goodman of UCSD.

The findings are notable, because in unselected patients, the rates of response to immune checkpoint blockade range from 10% to 20%.

Lessons from cHL and solid tumors

“Over the past few years, investigators have identified numerous biomarkers that can select subgroups of patients with increased likelihoods of responding to PD-1 blockade,” he said, adding that biomarkers include PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry, microsatellite instability – with microsatellite instability–high tumors responding extremely well to immunotherapy, tumor mutational burden measured by whole exome sequencing and next generation sequencing, and possibly PD-L1 amplification.

Of note, response rates are high in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). In general, cHL patients respond well to treatment, with the majority being cured by way of multiagent chemotherapy and radiation.

“But for the subpopulation that fails to respond to chemotherapy or relapses, outcomes still remain suboptimal. Remarkably, in the relapsed/refractory population of Hodgkin lymphoma ... response rates to single agent nivolumab and pembrolizumab were 65% to 87% [in recent studies],” he said. “Long-term follow-up demonstrates that the majority of these responses were durable and lasted over a year.”

The question is why relapsed/refractory cHL patients treated with immune checkpoint blockade have such a higher response rate than is typically seen in patients with solid tumors.

One answer might lie in the recent finding that nearly 100% of cHL tumors harbor amplification of 9p24.1; the 9p24.1 amplicon encodes the genes PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2, (and thus is also known as the PDJ amplicon), he explained, adding that “through gene dose-dependent increased expression of PD-L1 ligand on the Hodgkin lymphoma Reed-Sternberg cells, there is also JAK-STAT mediation of further expression of PD-L1 on the Reed-Sternberg cells.

An encounter with a patient with metastatic basal cell carcinoma – a “relatively unusual situation, as the majority of patients are cured with local therapy”– led to interest in looking at 9p24.1 alterations in solid tumors.

The patient had extensive metastatic disease, and had progressed through multiple therapies. Given his limited treatment options, next generation sequencing was performed on a biopsy from his tumor, and it revealed the PTCH1 alteration typical in basal cell carcinoma, as well as amplification of 9p24.1 with PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2 amplification. Nivolumab monotherapy was initiated.

“Within 2 months, he had an excellent partial response to therapy, and I’m pleased to say that he’s in an ongoing complete response 2 years later,” Dr. Goodman said.

It was that case that sparked the idea for the current study.

9p24.1 alterations and checkpoint blockade

“With my interest in hematologic malignancies, I was unaware that [9p24.1] amplification could occur in solid tumors, so the first aim was to determine the prevalence of chromosome 9p24.1 alterations in solid tumors. The next was to determine if patients with solid tumors and chromosome 9p24.1 alterations respond to PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade.

“What is astounding is [that PD-L1 amplification] was found in over 100 unique tumor histologies, although rare in most histologies,” Dr. Goodman said, noting that histologies with a statistically increased prevalence of PD-L1 amplification included breast cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, and soft tissue sarcoma.

There also were some rare histologies with increased prevalence of PD-L1 amplification, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma, renal sarcomatoid carcinoma, bladder squamous cell carcinoma, and liver mixed hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma, he said.

Tumors with a paucity of PD-L1 amplification included colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, and cutaneous melanoma, although even these still harbored a few patients with amplification, he said.

A closer look at the mutational burden in amplified vs. unamplified tumors showed a median of 7.4 vs. 3.6 mut/mb, but in the PD-L1 amplified group, 85% still had a low-to intermediate mutational burden of 1-20 mut/mb.

“Microsatellite instability and PD-L1 amplification were not mutually exclusive, but a rare event. Five of the 821 cases with PD-L1 amplification were microsatellite high; these included three carcinomas of unknown origin and two cases of gastrointestinal cancer,” he noted.

Treatment outcomes

In the 13 UCSD patients with PD-L1 amplification, nine different malignancies were identified, and all patients had advanced or metastatic disease and were heavily pretreated. Of the nine treated patients, five received anti-PD-1 monotherapy, one received anti-CTLA4/anti-PD-1 combination therapy, and three received a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor plus an investigational agent, which was immunotherapeutic, Dr. Goodman said.

The 67% overall response rate was similar to that seen in Hodgkin lymphoma, and many of the responses were durable; median overall survival was not reached.

Of note, genomic analysis in the 13 UCSD patients found to have PD-L1 amplification showed there were 143 total alterations in 70 different genes. All but one patient had amplification of PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2, and that one had amplification of PD-L1 and PD-L2.

Of six tumors with tissue available to test for PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry, four (67%) tested positive. None were microsatellite high, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were present in five cases.

The tumors that tested negative for PD-L1 expression were from the patient with the rare basal cell cancer, and another with glioblastoma. Both responded to anti-PD1/PD-L1 therapy.

The glioblastoma patient was a 40-year-old man with progressive disease, who underwent standard surgical debulking followed by concurrent radiation therapy plus temozolomide. He progressed soon after completing the concurrent chemoradiation therapy, and genomic profiling revealed 12 alterations, including 9p24.1 amplification, Dr. Goodman said, adding that nivolumab therapy was initiated.

“By week 12, much of the tumor mass had started to resolve, and by week 26 it continued to decrease further. He continues to be in an ongoing partial response at 5.2 months,” he said.

Recommendations

The findings of this study demonstrate that PD-Ll amplification is rare in solid tumors.

“However, PD-L1 amplification appears to be tissue agnostic, as we have seen in over 100 tumor histologies. We also noted that PD-L1 amplification was enriched in many rare tumors with limited treatment options, including anaplastic thyroid cancer, sarcomatoid carcinoma, and some sarcomas. We believe testing for PD-L1 amplification may be warranted given the frequent responses that were durable and seemed to be independent of mutational burden,” he concluded.

Ravindra Uppaluri, MD, session chair and discussant for Dr. Goodman’s presentation, said that Dr. Goodman’s findings should be considered in the context of “the complex biology [of PD-L1/PD-L2] that has evolved over the last few years.”

He specifically mentioned the two patients without PD-L1 expression despite amplification, but with response to immune checkpoint blockade, and noted that “there are several things going on here ... and we really want to look at all these things.”

The PDJ amplicon, especially given “the ability to look at this with the targeted gene panels that many patients are getting,” is clearly contributing to biomarker stratification, said Dr. Uppaluri of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

However, it should be assessed as part of a “global biomarker” that includes tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and tumor mutational burden, he said.

Dr. Goodman reported having no disclosures. Dr. Uppaluri has received grant/research support from NIH/NIDCR, Merck, and V Foundation, and has received honoraria from Merck.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Goodman A et al. ASCO-SITC, Abstract 47

SAN FRANCISCO – Amplification of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), also known as cluster of differentiation 274 (CD274), is rare in most solid tumors, but findings from an analysis in which a majority of patients with the alteration experienced durable responses to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade suggest that testing for it may be warranted.

Of 117,344 deidentified cancer patient samples from a large database, only 0.7% had PD-L1 amplification, which was defined as 6 or more copy number alterations (CNAs). The CNAs were found across more than 100 tumor histologies, Aaron Goodman, MD, reported at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

Of a subset of 2,039 clinically annotated patients from the database, who were seen at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Center for Personalized Cancer Therapy, 13 (0.6%) had PD-L1 CNAs, and 9 were treated with immune checkpoint blockade, either alone or in combination with another immunotherapeutic or targeted therapy, after a median of four prior systemic therapies.

The PD-1/PD-L1 blockade response rate in those nine patients was 67%, and median progression-free survival was 15.2 months; three objective responses were ongoing for at least 15 months, said Dr. Goodman of UCSD.

The findings are notable, because in unselected patients, the rates of response to immune checkpoint blockade range from 10% to 20%.

Lessons from cHL and solid tumors

“Over the past few years, investigators have identified numerous biomarkers that can select subgroups of patients with increased likelihoods of responding to PD-1 blockade,” he said, adding that biomarkers include PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry, microsatellite instability – with microsatellite instability–high tumors responding extremely well to immunotherapy, tumor mutational burden measured by whole exome sequencing and next generation sequencing, and possibly PD-L1 amplification.

Of note, response rates are high in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). In general, cHL patients respond well to treatment, with the majority being cured by way of multiagent chemotherapy and radiation.

“But for the subpopulation that fails to respond to chemotherapy or relapses, outcomes still remain suboptimal. Remarkably, in the relapsed/refractory population of Hodgkin lymphoma ... response rates to single agent nivolumab and pembrolizumab were 65% to 87% [in recent studies],” he said. “Long-term follow-up demonstrates that the majority of these responses were durable and lasted over a year.”

The question is why relapsed/refractory cHL patients treated with immune checkpoint blockade have such a higher response rate than is typically seen in patients with solid tumors.

One answer might lie in the recent finding that nearly 100% of cHL tumors harbor amplification of 9p24.1; the 9p24.1 amplicon encodes the genes PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2, (and thus is also known as the PDJ amplicon), he explained, adding that “through gene dose-dependent increased expression of PD-L1 ligand on the Hodgkin lymphoma Reed-Sternberg cells, there is also JAK-STAT mediation of further expression of PD-L1 on the Reed-Sternberg cells.

An encounter with a patient with metastatic basal cell carcinoma – a “relatively unusual situation, as the majority of patients are cured with local therapy”– led to interest in looking at 9p24.1 alterations in solid tumors.

The patient had extensive metastatic disease, and had progressed through multiple therapies. Given his limited treatment options, next generation sequencing was performed on a biopsy from his tumor, and it revealed the PTCH1 alteration typical in basal cell carcinoma, as well as amplification of 9p24.1 with PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2 amplification. Nivolumab monotherapy was initiated.

“Within 2 months, he had an excellent partial response to therapy, and I’m pleased to say that he’s in an ongoing complete response 2 years later,” Dr. Goodman said.

It was that case that sparked the idea for the current study.

9p24.1 alterations and checkpoint blockade

“With my interest in hematologic malignancies, I was unaware that [9p24.1] amplification could occur in solid tumors, so the first aim was to determine the prevalence of chromosome 9p24.1 alterations in solid tumors. The next was to determine if patients with solid tumors and chromosome 9p24.1 alterations respond to PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade.

“What is astounding is [that PD-L1 amplification] was found in over 100 unique tumor histologies, although rare in most histologies,” Dr. Goodman said, noting that histologies with a statistically increased prevalence of PD-L1 amplification included breast cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, and soft tissue sarcoma.

There also were some rare histologies with increased prevalence of PD-L1 amplification, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma, renal sarcomatoid carcinoma, bladder squamous cell carcinoma, and liver mixed hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma, he said.

Tumors with a paucity of PD-L1 amplification included colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, and cutaneous melanoma, although even these still harbored a few patients with amplification, he said.

A closer look at the mutational burden in amplified vs. unamplified tumors showed a median of 7.4 vs. 3.6 mut/mb, but in the PD-L1 amplified group, 85% still had a low-to intermediate mutational burden of 1-20 mut/mb.

“Microsatellite instability and PD-L1 amplification were not mutually exclusive, but a rare event. Five of the 821 cases with PD-L1 amplification were microsatellite high; these included three carcinomas of unknown origin and two cases of gastrointestinal cancer,” he noted.

Treatment outcomes

In the 13 UCSD patients with PD-L1 amplification, nine different malignancies were identified, and all patients had advanced or metastatic disease and were heavily pretreated. Of the nine treated patients, five received anti-PD-1 monotherapy, one received anti-CTLA4/anti-PD-1 combination therapy, and three received a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor plus an investigational agent, which was immunotherapeutic, Dr. Goodman said.

The 67% overall response rate was similar to that seen in Hodgkin lymphoma, and many of the responses were durable; median overall survival was not reached.

Of note, genomic analysis in the 13 UCSD patients found to have PD-L1 amplification showed there were 143 total alterations in 70 different genes. All but one patient had amplification of PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2, and that one had amplification of PD-L1 and PD-L2.

Of six tumors with tissue available to test for PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry, four (67%) tested positive. None were microsatellite high, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were present in five cases.

The tumors that tested negative for PD-L1 expression were from the patient with the rare basal cell cancer, and another with glioblastoma. Both responded to anti-PD1/PD-L1 therapy.

The glioblastoma patient was a 40-year-old man with progressive disease, who underwent standard surgical debulking followed by concurrent radiation therapy plus temozolomide. He progressed soon after completing the concurrent chemoradiation therapy, and genomic profiling revealed 12 alterations, including 9p24.1 amplification, Dr. Goodman said, adding that nivolumab therapy was initiated.

“By week 12, much of the tumor mass had started to resolve, and by week 26 it continued to decrease further. He continues to be in an ongoing partial response at 5.2 months,” he said.

Recommendations

The findings of this study demonstrate that PD-Ll amplification is rare in solid tumors.

“However, PD-L1 amplification appears to be tissue agnostic, as we have seen in over 100 tumor histologies. We also noted that PD-L1 amplification was enriched in many rare tumors with limited treatment options, including anaplastic thyroid cancer, sarcomatoid carcinoma, and some sarcomas. We believe testing for PD-L1 amplification may be warranted given the frequent responses that were durable and seemed to be independent of mutational burden,” he concluded.

Ravindra Uppaluri, MD, session chair and discussant for Dr. Goodman’s presentation, said that Dr. Goodman’s findings should be considered in the context of “the complex biology [of PD-L1/PD-L2] that has evolved over the last few years.”

He specifically mentioned the two patients without PD-L1 expression despite amplification, but with response to immune checkpoint blockade, and noted that “there are several things going on here ... and we really want to look at all these things.”

The PDJ amplicon, especially given “the ability to look at this with the targeted gene panels that many patients are getting,” is clearly contributing to biomarker stratification, said Dr. Uppaluri of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

However, it should be assessed as part of a “global biomarker” that includes tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and tumor mutational burden, he said.

Dr. Goodman reported having no disclosures. Dr. Uppaluri has received grant/research support from NIH/NIDCR, Merck, and V Foundation, and has received honoraria from Merck.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Goodman A et al. ASCO-SITC, Abstract 47

SAN FRANCISCO – Amplification of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), also known as cluster of differentiation 274 (CD274), is rare in most solid tumors, but findings from an analysis in which a majority of patients with the alteration experienced durable responses to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade suggest that testing for it may be warranted.

Of 117,344 deidentified cancer patient samples from a large database, only 0.7% had PD-L1 amplification, which was defined as 6 or more copy number alterations (CNAs). The CNAs were found across more than 100 tumor histologies, Aaron Goodman, MD, reported at the ASCO-SITC Clinical Immuno-Oncology Symposium.

Of a subset of 2,039 clinically annotated patients from the database, who were seen at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) Center for Personalized Cancer Therapy, 13 (0.6%) had PD-L1 CNAs, and 9 were treated with immune checkpoint blockade, either alone or in combination with another immunotherapeutic or targeted therapy, after a median of four prior systemic therapies.

The PD-1/PD-L1 blockade response rate in those nine patients was 67%, and median progression-free survival was 15.2 months; three objective responses were ongoing for at least 15 months, said Dr. Goodman of UCSD.

The findings are notable, because in unselected patients, the rates of response to immune checkpoint blockade range from 10% to 20%.

Lessons from cHL and solid tumors

“Over the past few years, investigators have identified numerous biomarkers that can select subgroups of patients with increased likelihoods of responding to PD-1 blockade,” he said, adding that biomarkers include PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry, microsatellite instability – with microsatellite instability–high tumors responding extremely well to immunotherapy, tumor mutational burden measured by whole exome sequencing and next generation sequencing, and possibly PD-L1 amplification.

Of note, response rates are high in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). In general, cHL patients respond well to treatment, with the majority being cured by way of multiagent chemotherapy and radiation.

“But for the subpopulation that fails to respond to chemotherapy or relapses, outcomes still remain suboptimal. Remarkably, in the relapsed/refractory population of Hodgkin lymphoma ... response rates to single agent nivolumab and pembrolizumab were 65% to 87% [in recent studies],” he said. “Long-term follow-up demonstrates that the majority of these responses were durable and lasted over a year.”

The question is why relapsed/refractory cHL patients treated with immune checkpoint blockade have such a higher response rate than is typically seen in patients with solid tumors.

One answer might lie in the recent finding that nearly 100% of cHL tumors harbor amplification of 9p24.1; the 9p24.1 amplicon encodes the genes PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2, (and thus is also known as the PDJ amplicon), he explained, adding that “through gene dose-dependent increased expression of PD-L1 ligand on the Hodgkin lymphoma Reed-Sternberg cells, there is also JAK-STAT mediation of further expression of PD-L1 on the Reed-Sternberg cells.

An encounter with a patient with metastatic basal cell carcinoma – a “relatively unusual situation, as the majority of patients are cured with local therapy”– led to interest in looking at 9p24.1 alterations in solid tumors.

The patient had extensive metastatic disease, and had progressed through multiple therapies. Given his limited treatment options, next generation sequencing was performed on a biopsy from his tumor, and it revealed the PTCH1 alteration typical in basal cell carcinoma, as well as amplification of 9p24.1 with PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2 amplification. Nivolumab monotherapy was initiated.

“Within 2 months, he had an excellent partial response to therapy, and I’m pleased to say that he’s in an ongoing complete response 2 years later,” Dr. Goodman said.

It was that case that sparked the idea for the current study.

9p24.1 alterations and checkpoint blockade

“With my interest in hematologic malignancies, I was unaware that [9p24.1] amplification could occur in solid tumors, so the first aim was to determine the prevalence of chromosome 9p24.1 alterations in solid tumors. The next was to determine if patients with solid tumors and chromosome 9p24.1 alterations respond to PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade.

“What is astounding is [that PD-L1 amplification] was found in over 100 unique tumor histologies, although rare in most histologies,” Dr. Goodman said, noting that histologies with a statistically increased prevalence of PD-L1 amplification included breast cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, and soft tissue sarcoma.

There also were some rare histologies with increased prevalence of PD-L1 amplification, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma, renal sarcomatoid carcinoma, bladder squamous cell carcinoma, and liver mixed hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma, he said.

Tumors with a paucity of PD-L1 amplification included colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, and cutaneous melanoma, although even these still harbored a few patients with amplification, he said.

A closer look at the mutational burden in amplified vs. unamplified tumors showed a median of 7.4 vs. 3.6 mut/mb, but in the PD-L1 amplified group, 85% still had a low-to intermediate mutational burden of 1-20 mut/mb.

“Microsatellite instability and PD-L1 amplification were not mutually exclusive, but a rare event. Five of the 821 cases with PD-L1 amplification were microsatellite high; these included three carcinomas of unknown origin and two cases of gastrointestinal cancer,” he noted.

Treatment outcomes

In the 13 UCSD patients with PD-L1 amplification, nine different malignancies were identified, and all patients had advanced or metastatic disease and were heavily pretreated. Of the nine treated patients, five received anti-PD-1 monotherapy, one received anti-CTLA4/anti-PD-1 combination therapy, and three received a PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor plus an investigational agent, which was immunotherapeutic, Dr. Goodman said.

The 67% overall response rate was similar to that seen in Hodgkin lymphoma, and many of the responses were durable; median overall survival was not reached.

Of note, genomic analysis in the 13 UCSD patients found to have PD-L1 amplification showed there were 143 total alterations in 70 different genes. All but one patient had amplification of PD-L1, PD-L2, and JAK2, and that one had amplification of PD-L1 and PD-L2.

Of six tumors with tissue available to test for PD-L1 expression by immunohistochemistry, four (67%) tested positive. None were microsatellite high, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were present in five cases.

The tumors that tested negative for PD-L1 expression were from the patient with the rare basal cell cancer, and another with glioblastoma. Both responded to anti-PD1/PD-L1 therapy.

The glioblastoma patient was a 40-year-old man with progressive disease, who underwent standard surgical debulking followed by concurrent radiation therapy plus temozolomide. He progressed soon after completing the concurrent chemoradiation therapy, and genomic profiling revealed 12 alterations, including 9p24.1 amplification, Dr. Goodman said, adding that nivolumab therapy was initiated.

“By week 12, much of the tumor mass had started to resolve, and by week 26 it continued to decrease further. He continues to be in an ongoing partial response at 5.2 months,” he said.

Recommendations

The findings of this study demonstrate that PD-Ll amplification is rare in solid tumors.

“However, PD-L1 amplification appears to be tissue agnostic, as we have seen in over 100 tumor histologies. We also noted that PD-L1 amplification was enriched in many rare tumors with limited treatment options, including anaplastic thyroid cancer, sarcomatoid carcinoma, and some sarcomas. We believe testing for PD-L1 amplification may be warranted given the frequent responses that were durable and seemed to be independent of mutational burden,” he concluded.

Ravindra Uppaluri, MD, session chair and discussant for Dr. Goodman’s presentation, said that Dr. Goodman’s findings should be considered in the context of “the complex biology [of PD-L1/PD-L2] that has evolved over the last few years.”

He specifically mentioned the two patients without PD-L1 expression despite amplification, but with response to immune checkpoint blockade, and noted that “there are several things going on here ... and we really want to look at all these things.”

The PDJ amplicon, especially given “the ability to look at this with the targeted gene panels that many patients are getting,” is clearly contributing to biomarker stratification, said Dr. Uppaluri of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

However, it should be assessed as part of a “global biomarker” that includes tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and tumor mutational burden, he said.

Dr. Goodman reported having no disclosures. Dr. Uppaluri has received grant/research support from NIH/NIDCR, Merck, and V Foundation, and has received honoraria from Merck.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Goodman A et al. ASCO-SITC, Abstract 47

REPORTING FROM THE CLINICAL IMMUNO-ONCOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point: Solid tumor patients with PD-L1 amplification had durable responses to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade.

Major finding: The overall response rate was 67% in nine patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade.

Study details: An analysis of more than 117,000 patient samples.

Disclosures: Dr. Goodman reported having no disclosures. Dr. Uppaluri has received grant/research support from NIH/NIDCR, Merck, and V Foundation, and has received honoraria from Merck.

Source: Goodman A et al. ASCO-SITC, Abstract 47.

Enlarging Red Papulonodule on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

Histopathologic examination of the punch biopsy demonstrated epithelioid cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and numerous chicken wire-like vascular channels consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of renal cell carcinoma (RCC)(Figure). Collateral history revealed that 8 years prior, the patient had been diagnosed with clear cell RCC, stage III (T3aN0M0). At that time, he was treated with radical nephrectomy, which was considered curative. He remained disease free until several months prior to the development of the cutaneous lesion when he was found to have pulmonary and cerebral metastases with biopsies showing metastatic RCC. He was treated with lobectomy and Gamma Knife radiation for the lung and cerebral metastases, respectively. His oncologist planned to initiate therapy with the multikinase inhibitor sunitinib, which inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling. Unfortunately, the patient died prior to treatment due to overwhelming tumor burden.

Clear cell RCC, the most common renal malignancy, presents with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis in 21% of patients.1 An additional 20% of patients with localized disease develop metastases within several years of receiving a nephrectomy without adjuvant therapy, which is standard treatment for stage I to stage III disease.1,2 Metastatic RCC most frequently targets the lungs, bone, liver, and brain, though virtually any organ can be involved. Cutaneous involvement is estimated to occur in 3.3% of RCC cases,3 accounting for only 1.4% of cutaneous metastases overall.4 The risk for developing cutaneous metastases is greatest within 3 years following nephrectomy.3 However, our patient demonstrates that metastasis of RCC to skin can be long delayed (>5 years) despite an initial diagnosis of localized disease.

Cutaneous RCC classically presents as a painless firm papulonodule with a deep red or purple color due to its high vascularity.4 Several retrospective studies have identified the scalp as the most frequent site of cutaneous involvement, followed by the chest, abdomen, and nephrectomy scar.3,4 The differential diagnosis includes other vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, angiosarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, and Kaposi sarcoma. Diagnosis usually is easily confirmed histologically. Proliferative nests of epithelioid cells with clear cell morphology are surrounded by delicately branching vessels referred to as chicken wire-like vasculature. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for pan-cytokeratin, vimentin, and CD-10, and negativity for p63 and cytokeratins 5 and 6, helping to confirm the diagnosis in more challenging cases, especially when there is no known history of primary RCC.5

If cutaneous metastasis of RCC is diagnosed, a chest and abdominal computed tomography scan as well as serum alkaline phosphatase test are warranted, as up to 90% of patients with RCC in the skin have additional lesions in at least 1 other site such as the lungs, bones, or liver.3 Management of metastatic RCC includes surgical excision if a single metastasis is found and either immunotherapy with high-dose IL-2 or an anti-programmed cell death inhibitor. Patients with progressive disease also may receive targeted anti-VEGF inhibitors (eg, axitinib, pazopanib, sunitinib), which have been shown to increase progression-free survival in metastatic RCC.6-8 Interestingly, some evidence suggests severely delayed recurrence of RCC (>5 years following nephrectomy) may predict better response to systemic therapy.9

This case of severely delayed metastasis of RCC 8 years after nephrectomy raises the question of whether routine surveillance for RCC recurrence should continue beyond 5 years. It also underscores the need for further studies to determine the utility of postsurgical adjuvant therapy for localized disease (stages I-III). A randomized clinical trial showed no significant difference in disease-free survival when the multikinase inhibitors sunitinib and sorafenib were used as adjuvant therapy.10 The randomized, placebo-controlled PROTECT trial showed no significant difference in disease-free survival between the VEGF inhibitor pazopanib and placebo when used as adjuvant therapy.11 However, trials are ongoing to investigate a potential survival advantage of adjuvant therapy with the VEGF receptor inhibitor axitinib and the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus.

- Dabestani S, Thorstenson A, Lindblad P, et al. Renal cell carcinoma recurrences and metastases in primary non-metastatic patients: a population-based study. World J Urol. 2016;34:1081-1086.

- Ljungberg B, Campbell SC, Choi HY, et al. The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;60:615-621.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):228-236.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613-620.

- Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1061-1068.

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3584-3590.

- Rini BI, Grunwald V, Fishman MN, et al. Axitinib for first-line metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): overall efficacy and pharmacokinetic (PK) analyses from a randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl). doi:10.1200/jco.2012.30.15_suppl.4503.

- Ficarra V, Novara G. Characterizing late recurrence of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10:687-689.

- Haas NB, Manola J, Uzzo RG, et al. Adjuvant sunitinib or sorafenib for high-risk, non-metastatic renal-cell carcinoma (ECOG-ACRIN E2805): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3 trial [published online March 9, 2016]. Lancet. 2016;387:2008-2016.

- Motzer RJ, Haas NB, Donskov F, et al; PROTECT investigators. Randomized phase III trial of adjuvant pazopanib versus placebo after nephrectomy in patients with localized or locally advanced renal cell carcinoma [published online September 13, 2017]. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3916-3923.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

Histopathologic examination of the punch biopsy demonstrated epithelioid cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and numerous chicken wire-like vascular channels consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of renal cell carcinoma (RCC)(Figure). Collateral history revealed that 8 years prior, the patient had been diagnosed with clear cell RCC, stage III (T3aN0M0). At that time, he was treated with radical nephrectomy, which was considered curative. He remained disease free until several months prior to the development of the cutaneous lesion when he was found to have pulmonary and cerebral metastases with biopsies showing metastatic RCC. He was treated with lobectomy and Gamma Knife radiation for the lung and cerebral metastases, respectively. His oncologist planned to initiate therapy with the multikinase inhibitor sunitinib, which inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling. Unfortunately, the patient died prior to treatment due to overwhelming tumor burden.

Clear cell RCC, the most common renal malignancy, presents with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis in 21% of patients.1 An additional 20% of patients with localized disease develop metastases within several years of receiving a nephrectomy without adjuvant therapy, which is standard treatment for stage I to stage III disease.1,2 Metastatic RCC most frequently targets the lungs, bone, liver, and brain, though virtually any organ can be involved. Cutaneous involvement is estimated to occur in 3.3% of RCC cases,3 accounting for only 1.4% of cutaneous metastases overall.4 The risk for developing cutaneous metastases is greatest within 3 years following nephrectomy.3 However, our patient demonstrates that metastasis of RCC to skin can be long delayed (>5 years) despite an initial diagnosis of localized disease.

Cutaneous RCC classically presents as a painless firm papulonodule with a deep red or purple color due to its high vascularity.4 Several retrospective studies have identified the scalp as the most frequent site of cutaneous involvement, followed by the chest, abdomen, and nephrectomy scar.3,4 The differential diagnosis includes other vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, angiosarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, and Kaposi sarcoma. Diagnosis usually is easily confirmed histologically. Proliferative nests of epithelioid cells with clear cell morphology are surrounded by delicately branching vessels referred to as chicken wire-like vasculature. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for pan-cytokeratin, vimentin, and CD-10, and negativity for p63 and cytokeratins 5 and 6, helping to confirm the diagnosis in more challenging cases, especially when there is no known history of primary RCC.5

If cutaneous metastasis of RCC is diagnosed, a chest and abdominal computed tomography scan as well as serum alkaline phosphatase test are warranted, as up to 90% of patients with RCC in the skin have additional lesions in at least 1 other site such as the lungs, bones, or liver.3 Management of metastatic RCC includes surgical excision if a single metastasis is found and either immunotherapy with high-dose IL-2 or an anti-programmed cell death inhibitor. Patients with progressive disease also may receive targeted anti-VEGF inhibitors (eg, axitinib, pazopanib, sunitinib), which have been shown to increase progression-free survival in metastatic RCC.6-8 Interestingly, some evidence suggests severely delayed recurrence of RCC (>5 years following nephrectomy) may predict better response to systemic therapy.9

This case of severely delayed metastasis of RCC 8 years after nephrectomy raises the question of whether routine surveillance for RCC recurrence should continue beyond 5 years. It also underscores the need for further studies to determine the utility of postsurgical adjuvant therapy for localized disease (stages I-III). A randomized clinical trial showed no significant difference in disease-free survival when the multikinase inhibitors sunitinib and sorafenib were used as adjuvant therapy.10 The randomized, placebo-controlled PROTECT trial showed no significant difference in disease-free survival between the VEGF inhibitor pazopanib and placebo when used as adjuvant therapy.11 However, trials are ongoing to investigate a potential survival advantage of adjuvant therapy with the VEGF receptor inhibitor axitinib and the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

Histopathologic examination of the punch biopsy demonstrated epithelioid cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and numerous chicken wire-like vascular channels consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of renal cell carcinoma (RCC)(Figure). Collateral history revealed that 8 years prior, the patient had been diagnosed with clear cell RCC, stage III (T3aN0M0). At that time, he was treated with radical nephrectomy, which was considered curative. He remained disease free until several months prior to the development of the cutaneous lesion when he was found to have pulmonary and cerebral metastases with biopsies showing metastatic RCC. He was treated with lobectomy and Gamma Knife radiation for the lung and cerebral metastases, respectively. His oncologist planned to initiate therapy with the multikinase inhibitor sunitinib, which inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling. Unfortunately, the patient died prior to treatment due to overwhelming tumor burden.

Clear cell RCC, the most common renal malignancy, presents with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis in 21% of patients.1 An additional 20% of patients with localized disease develop metastases within several years of receiving a nephrectomy without adjuvant therapy, which is standard treatment for stage I to stage III disease.1,2 Metastatic RCC most frequently targets the lungs, bone, liver, and brain, though virtually any organ can be involved. Cutaneous involvement is estimated to occur in 3.3% of RCC cases,3 accounting for only 1.4% of cutaneous metastases overall.4 The risk for developing cutaneous metastases is greatest within 3 years following nephrectomy.3 However, our patient demonstrates that metastasis of RCC to skin can be long delayed (>5 years) despite an initial diagnosis of localized disease.

Cutaneous RCC classically presents as a painless firm papulonodule with a deep red or purple color due to its high vascularity.4 Several retrospective studies have identified the scalp as the most frequent site of cutaneous involvement, followed by the chest, abdomen, and nephrectomy scar.3,4 The differential diagnosis includes other vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, angiosarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, and Kaposi sarcoma. Diagnosis usually is easily confirmed histologically. Proliferative nests of epithelioid cells with clear cell morphology are surrounded by delicately branching vessels referred to as chicken wire-like vasculature. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for pan-cytokeratin, vimentin, and CD-10, and negativity for p63 and cytokeratins 5 and 6, helping to confirm the diagnosis in more challenging cases, especially when there is no known history of primary RCC.5

If cutaneous metastasis of RCC is diagnosed, a chest and abdominal computed tomography scan as well as serum alkaline phosphatase test are warranted, as up to 90% of patients with RCC in the skin have additional lesions in at least 1 other site such as the lungs, bones, or liver.3 Management of metastatic RCC includes surgical excision if a single metastasis is found and either immunotherapy with high-dose IL-2 or an anti-programmed cell death inhibitor. Patients with progressive disease also may receive targeted anti-VEGF inhibitors (eg, axitinib, pazopanib, sunitinib), which have been shown to increase progression-free survival in metastatic RCC.6-8 Interestingly, some evidence suggests severely delayed recurrence of RCC (>5 years following nephrectomy) may predict better response to systemic therapy.9

This case of severely delayed metastasis of RCC 8 years after nephrectomy raises the question of whether routine surveillance for RCC recurrence should continue beyond 5 years. It also underscores the need for further studies to determine the utility of postsurgical adjuvant therapy for localized disease (stages I-III). A randomized clinical trial showed no significant difference in disease-free survival when the multikinase inhibitors sunitinib and sorafenib were used as adjuvant therapy.10 The randomized, placebo-controlled PROTECT trial showed no significant difference in disease-free survival between the VEGF inhibitor pazopanib and placebo when used as adjuvant therapy.11 However, trials are ongoing to investigate a potential survival advantage of adjuvant therapy with the VEGF receptor inhibitor axitinib and the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus.

- Dabestani S, Thorstenson A, Lindblad P, et al. Renal cell carcinoma recurrences and metastases in primary non-metastatic patients: a population-based study. World J Urol. 2016;34:1081-1086.

- Ljungberg B, Campbell SC, Choi HY, et al. The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;60:615-621.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):228-236.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613-620.

- Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1061-1068.

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3584-3590.

- Rini BI, Grunwald V, Fishman MN, et al. Axitinib for first-line metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): overall efficacy and pharmacokinetic (PK) analyses from a randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl). doi:10.1200/jco.2012.30.15_suppl.4503.

- Ficarra V, Novara G. Characterizing late recurrence of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10:687-689.

- Haas NB, Manola J, Uzzo RG, et al. Adjuvant sunitinib or sorafenib for high-risk, non-metastatic renal-cell carcinoma (ECOG-ACRIN E2805): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3 trial [published online March 9, 2016]. Lancet. 2016;387:2008-2016.

- Motzer RJ, Haas NB, Donskov F, et al; PROTECT investigators. Randomized phase III trial of adjuvant pazopanib versus placebo after nephrectomy in patients with localized or locally advanced renal cell carcinoma [published online September 13, 2017]. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3916-3923.

- Dabestani S, Thorstenson A, Lindblad P, et al. Renal cell carcinoma recurrences and metastases in primary non-metastatic patients: a population-based study. World J Urol. 2016;34:1081-1086.

- Ljungberg B, Campbell SC, Choi HY, et al. The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;60:615-621.

- Dorairajan LN, Hemal AK, Aron M, et al. Cutaneous metastases in renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int. 1999;63:164-167.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(2, pt 1):228-236.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613-620.

- Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1061-1068.

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3584-3590.

- Rini BI, Grunwald V, Fishman MN, et al. Axitinib for first-line metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): overall efficacy and pharmacokinetic (PK) analyses from a randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl). doi:10.1200/jco.2012.30.15_suppl.4503.

- Ficarra V, Novara G. Characterizing late recurrence of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10:687-689.

- Haas NB, Manola J, Uzzo RG, et al. Adjuvant sunitinib or sorafenib for high-risk, non-metastatic renal-cell carcinoma (ECOG-ACRIN E2805): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3 trial [published online March 9, 2016]. Lancet. 2016;387:2008-2016.

- Motzer RJ, Haas NB, Donskov F, et al; PROTECT investigators. Randomized phase III trial of adjuvant pazopanib versus placebo after nephrectomy in patients with localized or locally advanced renal cell carcinoma [published online September 13, 2017]. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3916-3923.

A man in his 60s presented with a subcutaneous nodule on the right side of the chest. Due to impaired mental status, he was unable to describe the precise age of the lesion, but his wife reported it had been present at least several weeks. She recently noted a new, bright red growth on top of the nodule. The lesion was asymptomatic but seemed to be growing in size. Physical examination revealed a 3-cm firm fixed nodule on the right side of the chest with an overlying, exophytic bright red papule. No similar lesions were found elsewhere on physical examination. A punch biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Mobile Medical Apps for Patient Education: A Graded Review of Available Dermatology Apps

According to industry estimates, roughly 64% of US adults were smartphone users in 2015.1 Smartphones enable users to utilize mobile applications (apps) that can perform a variety of functions in many categories, including business, music, photography, entertainment, education, social networking, travel, and lifestyle. The widespread adoption and use of mobile apps has implications for medical practice. Mobile apps have the capability to serve as information sources for patients, educational tools for students, and diagnostic aids for physicians.2 Consequently, a number of medical and health care–oriented apps have already been developed3 and are increasingly utilized by patients and providers.4

Given its visual nature, dermatology is particularly amenable to the integration of mobile medical apps. A study by Brewer et al5 identified more than 229 dermatology-related apps in categories ranging from general dermatology reference, self-surveillance and diagnosis, disease guides, educational aids, sunscreen and UV recommendations, and teledermatology. Patients served as the target audience and principal consumers of more than half of these dermatology apps.5

Mobile medical and health care apps demonstrate great potential for serving as valuable information sources for patients with dermatologic conditions; however, the content, functions, accuracy, and educational value of dermatology mobile apps are not well characterized, making it difficult for patients and health care providers to select and recommend appropriate apps.6 In this study, we created a rubric to objectively grade 44 publicly available mobile dermatology apps with the primary focus of patient education.

Methods

We conducted a search of dermatology-related educational mobile apps that were publicly available via the App Store (Apple Inc) from January 2016 to November 2016. (The pricing, availability, and other features of these apps may have changed since the study period.) The following search terms were used: dermatology, dermoscopy, melanoma, skin cancer, psoriasis, rosacea, acne, eczema, dermal fillers, and Mohs surgery. We excluded apps that were not in English; had a solely commercial focus; were mobile textbooks or scientific journals; were used to provide teledermatology services with no educational purpose; were solely focused on homeopathic, alternative, and/or complementary medicine; or were intended primarily as a reference for students or health care professionals. Our search yielded 44 apps with patient education as a primary objective. The apps were divided into 6 categories based on their focus: general dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, acne, eczema, psoriasis, and skin cancer.

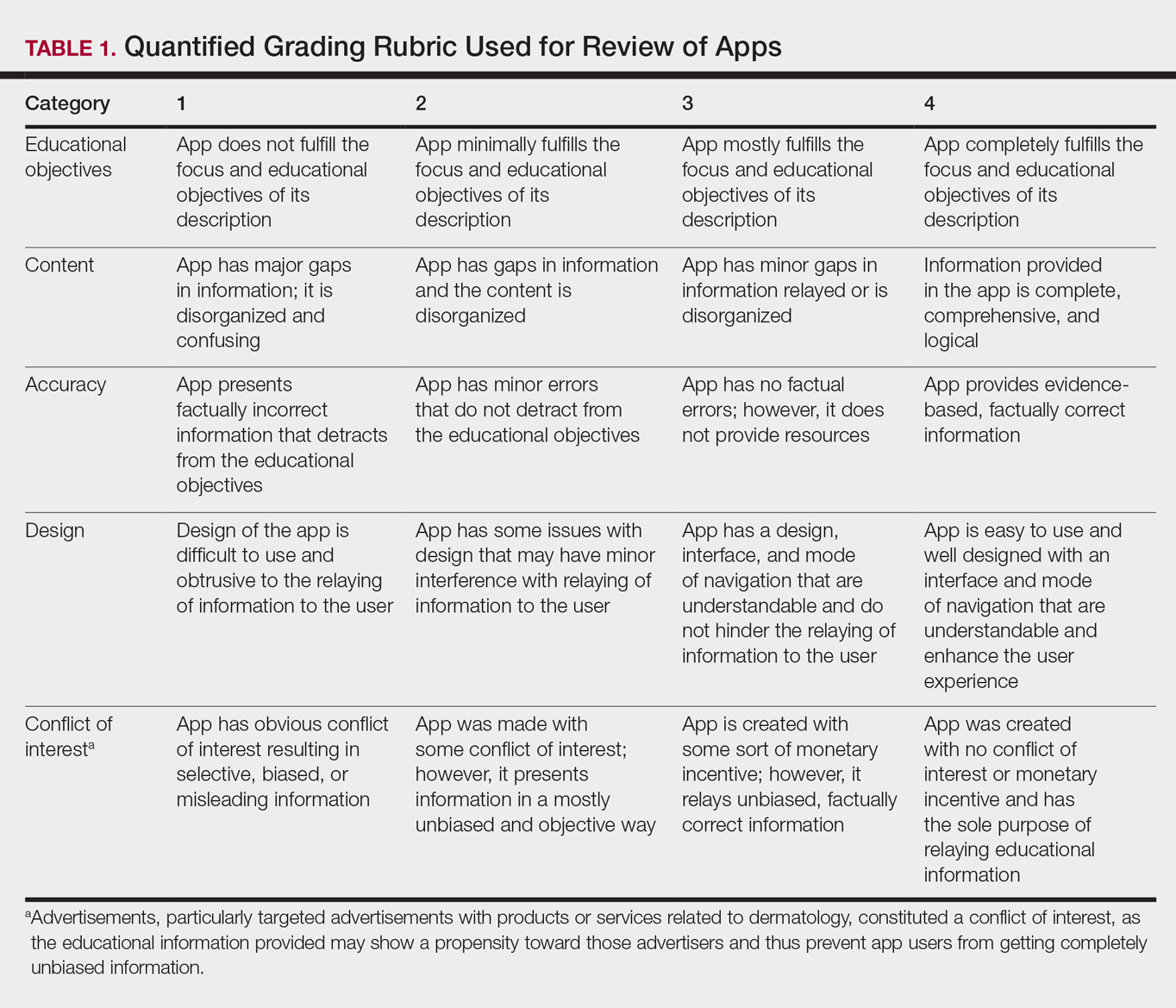

Each app was reviewed using a quantified grading rubric developed by the researchers. In a prior evaluation, Handel7 reviewed 35 health and wellness mobile apps utilizing the categories of ease of use, reliability, quality, scope of information, and aesthetics.4 These criteria were modified and adapted for the purposes of this study, and a 4-point scale was applied to each criterion. The final criteria were (1) educational objectives, (2) content, (3) accuracy, (4) design, and (5) conflict of interest. The quantified grading rubric is described in Table 1.

Results

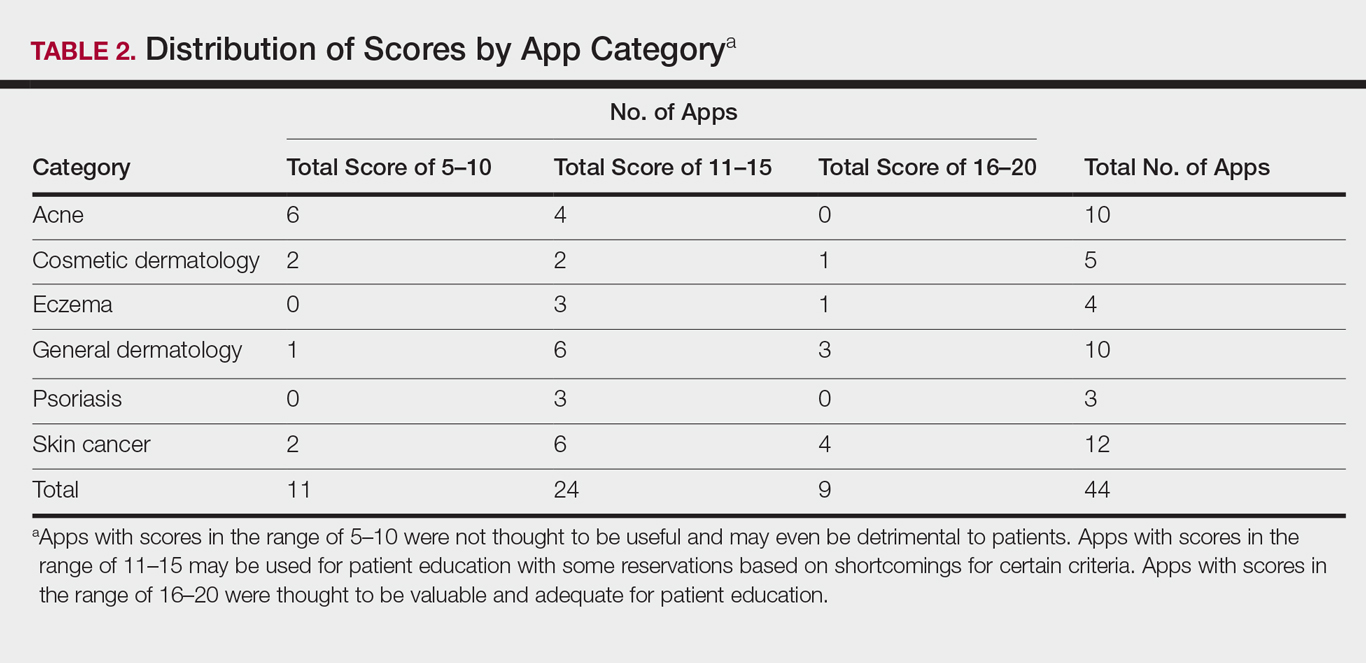

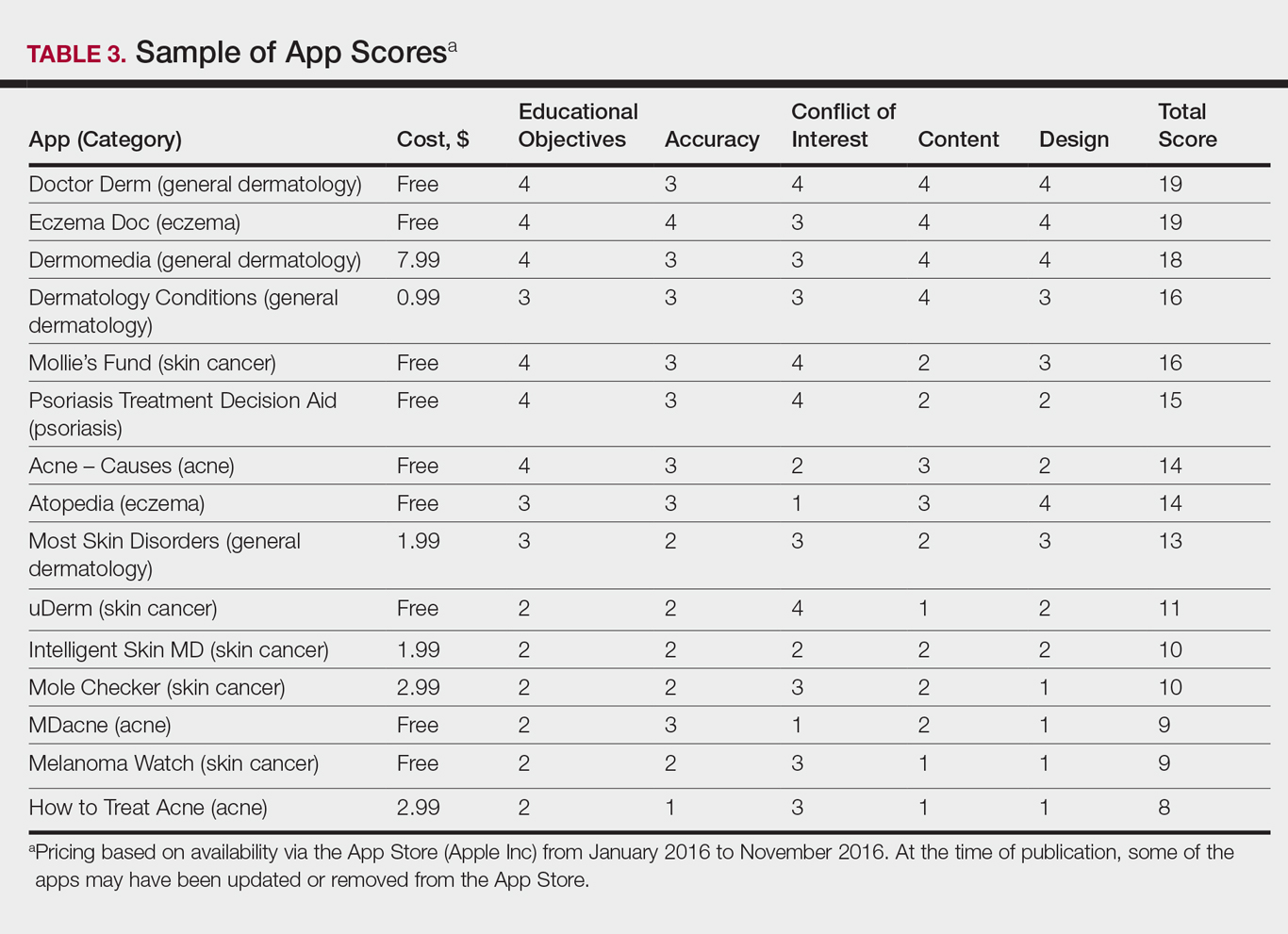

The possible range of scores based on the grading rubric was 5 to 20. The actual range of scores was 8 to 19 (Table 2). The 44 reviewed apps were categorized by topic as acne, cosmetic dermatology, eczema, general dermatology, psoriasis, or skin cancer. A sample of 15 apps selected to represent the distribution of scores and their grading on the rubric are presented in Table 3.

Comment

The number of dermatology-related apps available to mobile users continues to grow at an increasing rate.8 The apps vary in many aspects, including their purpose, scope, intended audience, and goals of the app publisher. In turn, more individuals are turning to mobile apps for medical information,4 especially in dermatology, thus it is necessary to create a systematic way to evaluate the quality and utility of each app to assist users in making informed decisions about which apps will best meet their needs in the midst of a wide array of choices.

For the purpose of this study, an objective rubric was created that can be used to evaluate the quality of medical apps for patient education in dermatology. An app’s adequacy and usefulness for patient education was thought to depend on 3 possible score ranges into which the app could fall based on the grading rubric. An app with a total score in the range of 5 to 10 was not thought to be useful and may even be detrimental to patients. An app with a total score in the range of 11 to 15 may be used for patient education with some reservations based on shortcomings for certain criteria. An app with a score in the range of 16 to 20 was thought to be valuable and adequate for patient education. For example, the How to Treat Acne app received a total score of 8 and therefore would not be recommended to patients based on the grading rubric used in this study. This particular app provided sparse and sometimes inaccurate information, had a confusing user interface, and contained many obstructive advertisements. In contrast, the Eczema Doc app received a total score of 19, which indicates a quality app deemed to be useful for patient information based on the established rubric. This app met all the objectives that it advertised, contained accurate information with verified citation of sources, and was very easy for users to navigate.

Of the 44 graded apps, only 9 (20.5%) received scores in the highest range of 16 to 20, which indicates a need for improvements in mobile dermatology apps intended for patient education. Adopting the grading rubric developed in this study as a standard in the creation of medical apps could have beneficial implications in disseminating accurate, safe, unbiased, and easy-to-understand information to patients.

- Smith A. U.S. smartphone use in 2015. Pew Research Center website. http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015. Published April 1, 2015. Accessed August 29, 2017.

- Nilsen W, Kumar S, Shar A, et al. Advancing the science of mHealth. J Health Commun. 2012;17(suppl 1):5-10.

- West DM. How mobile devices are transforming healthcare issues in technology innovation. Issues Technol Innov. 2012;18:1-14.

- Boudreaux ED, Waring ME, Hayes RB, et al. Evaluating and selecting mobile health apps: strategies for healthcare providers and healthcare organizations. Transl Behav Med. 2014;4:363-371.

- Brewer AC, Endly DC, Henley J, et al. Mobile applications in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1300-1304.

- Cummings E, Borycki E, Roehrer E. Issues and considerations for healthcare consumers using mobile applications. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;183:227-231.

- Handel MJ. mHealth (mobile health)-using apps for health and wellness. Explore. 2011;7:256-261.

- Boulos MN, Brewer AC, Karimkhani C, et al. Mobile medical and health apps: state of the art, concerns, regulatory control and certification. Online J Public Health Inform. 2014;5:229.

According to industry estimates, roughly 64% of US adults were smartphone users in 2015.1 Smartphones enable users to utilize mobile applications (apps) that can perform a variety of functions in many categories, including business, music, photography, entertainment, education, social networking, travel, and lifestyle. The widespread adoption and use of mobile apps has implications for medical practice. Mobile apps have the capability to serve as information sources for patients, educational tools for students, and diagnostic aids for physicians.2 Consequently, a number of medical and health care–oriented apps have already been developed3 and are increasingly utilized by patients and providers.4

Given its visual nature, dermatology is particularly amenable to the integration of mobile medical apps. A study by Brewer et al5 identified more than 229 dermatology-related apps in categories ranging from general dermatology reference, self-surveillance and diagnosis, disease guides, educational aids, sunscreen and UV recommendations, and teledermatology. Patients served as the target audience and principal consumers of more than half of these dermatology apps.5

Mobile medical and health care apps demonstrate great potential for serving as valuable information sources for patients with dermatologic conditions; however, the content, functions, accuracy, and educational value of dermatology mobile apps are not well characterized, making it difficult for patients and health care providers to select and recommend appropriate apps.6 In this study, we created a rubric to objectively grade 44 publicly available mobile dermatology apps with the primary focus of patient education.

Methods

We conducted a search of dermatology-related educational mobile apps that were publicly available via the App Store (Apple Inc) from January 2016 to November 2016. (The pricing, availability, and other features of these apps may have changed since the study period.) The following search terms were used: dermatology, dermoscopy, melanoma, skin cancer, psoriasis, rosacea, acne, eczema, dermal fillers, and Mohs surgery. We excluded apps that were not in English; had a solely commercial focus; were mobile textbooks or scientific journals; were used to provide teledermatology services with no educational purpose; were solely focused on homeopathic, alternative, and/or complementary medicine; or were intended primarily as a reference for students or health care professionals. Our search yielded 44 apps with patient education as a primary objective. The apps were divided into 6 categories based on their focus: general dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, acne, eczema, psoriasis, and skin cancer.

Each app was reviewed using a quantified grading rubric developed by the researchers. In a prior evaluation, Handel7 reviewed 35 health and wellness mobile apps utilizing the categories of ease of use, reliability, quality, scope of information, and aesthetics.4 These criteria were modified and adapted for the purposes of this study, and a 4-point scale was applied to each criterion. The final criteria were (1) educational objectives, (2) content, (3) accuracy, (4) design, and (5) conflict of interest. The quantified grading rubric is described in Table 1.

Results

The possible range of scores based on the grading rubric was 5 to 20. The actual range of scores was 8 to 19 (Table 2). The 44 reviewed apps were categorized by topic as acne, cosmetic dermatology, eczema, general dermatology, psoriasis, or skin cancer. A sample of 15 apps selected to represent the distribution of scores and their grading on the rubric are presented in Table 3.

Comment

The number of dermatology-related apps available to mobile users continues to grow at an increasing rate.8 The apps vary in many aspects, including their purpose, scope, intended audience, and goals of the app publisher. In turn, more individuals are turning to mobile apps for medical information,4 especially in dermatology, thus it is necessary to create a systematic way to evaluate the quality and utility of each app to assist users in making informed decisions about which apps will best meet their needs in the midst of a wide array of choices.

For the purpose of this study, an objective rubric was created that can be used to evaluate the quality of medical apps for patient education in dermatology. An app’s adequacy and usefulness for patient education was thought to depend on 3 possible score ranges into which the app could fall based on the grading rubric. An app with a total score in the range of 5 to 10 was not thought to be useful and may even be detrimental to patients. An app with a total score in the range of 11 to 15 may be used for patient education with some reservations based on shortcomings for certain criteria. An app with a score in the range of 16 to 20 was thought to be valuable and adequate for patient education. For example, the How to Treat Acne app received a total score of 8 and therefore would not be recommended to patients based on the grading rubric used in this study. This particular app provided sparse and sometimes inaccurate information, had a confusing user interface, and contained many obstructive advertisements. In contrast, the Eczema Doc app received a total score of 19, which indicates a quality app deemed to be useful for patient information based on the established rubric. This app met all the objectives that it advertised, contained accurate information with verified citation of sources, and was very easy for users to navigate.

Of the 44 graded apps, only 9 (20.5%) received scores in the highest range of 16 to 20, which indicates a need for improvements in mobile dermatology apps intended for patient education. Adopting the grading rubric developed in this study as a standard in the creation of medical apps could have beneficial implications in disseminating accurate, safe, unbiased, and easy-to-understand information to patients.