User login

CO2 laser guided by confocal microscopy effectively treated superficial BCC

DALLAS – The use of CO2 laser ablation guided by reflectance confocal microscopy is an effective, minimally invasive treatment for superficial and early nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC), according to results from an ongoing study.

“While surgery is the gold standard for many basal cell carcinomas, nonsurgical therapies may be a good option for the superficial and early nodular subtypes,” lead study author Anthony M. Rossi, MD, said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Laser ablation was used many years ago, so this is not a novel concept, but we’re bringing it back and we’re trying to use confocal microscopy to hone in on the basal cell and selectively target the tumor.”

For the current analysis, he and his associates used with a mean age of 55 years. Of the 20 lesions, 18 were located on the limbs and trunk, while two were on the head and neck. The median lesion diameter was 7 mm. Prior to laser ablation, the researchers performed reflectance confocal microscopy to define lateral and deep margins and define the laser parameters.

The median number of laser passes was three, and ranged from two to eight, delivered at a fluence of 7.5 J/cm2. Reflectance confocal microscopy was repeated immediately after the laser treatment to the skin wound margins and deep margins, and it was performed every 3-6 months thereafter. “If you do confocal microscopy too early, you’ll see mainly inflammation and you may see residual tumor that hasn’t been fully resolved yet,” Dr. Rossi said.

As for future directions, he and his colleagues are developing contrast agents to enhance the ability to detect BCC tumors in vivo, to highlight tumor islands, and to differentiate sebaceous glands and hair follicles. Dr. Rossi reported having no relevant disclosures.

DALLAS – The use of CO2 laser ablation guided by reflectance confocal microscopy is an effective, minimally invasive treatment for superficial and early nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC), according to results from an ongoing study.

“While surgery is the gold standard for many basal cell carcinomas, nonsurgical therapies may be a good option for the superficial and early nodular subtypes,” lead study author Anthony M. Rossi, MD, said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Laser ablation was used many years ago, so this is not a novel concept, but we’re bringing it back and we’re trying to use confocal microscopy to hone in on the basal cell and selectively target the tumor.”

For the current analysis, he and his associates used with a mean age of 55 years. Of the 20 lesions, 18 were located on the limbs and trunk, while two were on the head and neck. The median lesion diameter was 7 mm. Prior to laser ablation, the researchers performed reflectance confocal microscopy to define lateral and deep margins and define the laser parameters.

The median number of laser passes was three, and ranged from two to eight, delivered at a fluence of 7.5 J/cm2. Reflectance confocal microscopy was repeated immediately after the laser treatment to the skin wound margins and deep margins, and it was performed every 3-6 months thereafter. “If you do confocal microscopy too early, you’ll see mainly inflammation and you may see residual tumor that hasn’t been fully resolved yet,” Dr. Rossi said.

As for future directions, he and his colleagues are developing contrast agents to enhance the ability to detect BCC tumors in vivo, to highlight tumor islands, and to differentiate sebaceous glands and hair follicles. Dr. Rossi reported having no relevant disclosures.

DALLAS – The use of CO2 laser ablation guided by reflectance confocal microscopy is an effective, minimally invasive treatment for superficial and early nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC), according to results from an ongoing study.

“While surgery is the gold standard for many basal cell carcinomas, nonsurgical therapies may be a good option for the superficial and early nodular subtypes,” lead study author Anthony M. Rossi, MD, said at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Laser ablation was used many years ago, so this is not a novel concept, but we’re bringing it back and we’re trying to use confocal microscopy to hone in on the basal cell and selectively target the tumor.”

For the current analysis, he and his associates used with a mean age of 55 years. Of the 20 lesions, 18 were located on the limbs and trunk, while two were on the head and neck. The median lesion diameter was 7 mm. Prior to laser ablation, the researchers performed reflectance confocal microscopy to define lateral and deep margins and define the laser parameters.

The median number of laser passes was three, and ranged from two to eight, delivered at a fluence of 7.5 J/cm2. Reflectance confocal microscopy was repeated immediately after the laser treatment to the skin wound margins and deep margins, and it was performed every 3-6 months thereafter. “If you do confocal microscopy too early, you’ll see mainly inflammation and you may see residual tumor that hasn’t been fully resolved yet,” Dr. Rossi said.

As for future directions, he and his colleagues are developing contrast agents to enhance the ability to detect BCC tumors in vivo, to highlight tumor islands, and to differentiate sebaceous glands and hair follicles. Dr. Rossi reported having no relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ASLMS 2018

Key clinical point: Reflectance confocal microscopy-guided CO2 laser ablation of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) was found to be effective.

Major finding: After an average follow-up of 17 months, no recurrence of BCC has been detected clinically, dermoscopically, or by reflectance confocal microscopy.

Study details: A clinical analysis of seven adults with superficial BCC who were treated with a CO2 laser guided by confocal microscopy.

Disclosures: Dr. Rossi reported having no financial disclosures.

Tanning is the new tobacco

I was driving to work the other day, perched up in my pickup truck (somehow you knew that) and noticed a fancy race car in front of me with a vanity tag. It read HRTATTK 4. Well, I thought after four heart attacks maybe I would splurge on a special car too (more likely a newer truck). Then I noticed smoke coming out of the driver’s window, and I could see this guy in his side view mirror, presumably Mr. “Heart Attack 4,” puffing away on a cigarette. Wow.

Then I got to work and saw my secretary, who works with her oxygen on, out back puffing a cigarette. Wow.

It turns out that cigarette smoke contains substances that act as a monoamine oxidase (MAO) A inhibitor, prolonging the dopamine high in the brain (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Nov 26;93[24]:14065-9). Makes sense and may explain the above smoking behavior. I truly believe cigarettes are as or more addictive than any other dopamine enhancing drug.

More than 50 years ago, a national campaign against smoking was launched after the 1964 Surgeon General’s report concluded that smoking was a major health hazard. (Looking back, one of the few losses of not having to pull journal articles from the stacks in the library, is that medical students and residents can’t shake their heads in wonder at the cigarette ads in old medical journals.) The impact of the national antismoking campaign has been dramatic, but smoking remains the leading preventable cause of death in the United States and globally, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

in 2006, from 1992 (Arch Dermatol. 2010;146[3]:283-7), dermatologists had good footing on which to start a major prevention campaign. The American Cancer Society got on board, and in 2014, acting surgeon general Boris Lushniak, MD, issued a call to action to prevent skin cancer along with Howard Koh, MD, the assistant secretary of health, in “The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer” in 2014, and the campaign was on.

Well, I am delighted to pass on a report from Leonard Lichtenfeld, MD, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society, who recently described in his March 2018 blog what may the first signs of the effectiveness of efforts to promote protection from ultraviolet ray exposure (JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154[3]:361-2). He writes: “In young white women ages 15 to 24, the incidence of melanoma has declined an average of 5.5% per year from January 2005 through December 2014. Not 5.5% over those ten years but 5.5 % PER YEAR. That’s remarkable, to say the least.”

As for the reasons behind these trends, he says, “no one can say for certain,” but he refers to national data indicating that indoor tanning has decreased in the past few years, especially among adolescents and young adults.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

I was driving to work the other day, perched up in my pickup truck (somehow you knew that) and noticed a fancy race car in front of me with a vanity tag. It read HRTATTK 4. Well, I thought after four heart attacks maybe I would splurge on a special car too (more likely a newer truck). Then I noticed smoke coming out of the driver’s window, and I could see this guy in his side view mirror, presumably Mr. “Heart Attack 4,” puffing away on a cigarette. Wow.

Then I got to work and saw my secretary, who works with her oxygen on, out back puffing a cigarette. Wow.

It turns out that cigarette smoke contains substances that act as a monoamine oxidase (MAO) A inhibitor, prolonging the dopamine high in the brain (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Nov 26;93[24]:14065-9). Makes sense and may explain the above smoking behavior. I truly believe cigarettes are as or more addictive than any other dopamine enhancing drug.

More than 50 years ago, a national campaign against smoking was launched after the 1964 Surgeon General’s report concluded that smoking was a major health hazard. (Looking back, one of the few losses of not having to pull journal articles from the stacks in the library, is that medical students and residents can’t shake their heads in wonder at the cigarette ads in old medical journals.) The impact of the national antismoking campaign has been dramatic, but smoking remains the leading preventable cause of death in the United States and globally, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

in 2006, from 1992 (Arch Dermatol. 2010;146[3]:283-7), dermatologists had good footing on which to start a major prevention campaign. The American Cancer Society got on board, and in 2014, acting surgeon general Boris Lushniak, MD, issued a call to action to prevent skin cancer along with Howard Koh, MD, the assistant secretary of health, in “The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer” in 2014, and the campaign was on.

Well, I am delighted to pass on a report from Leonard Lichtenfeld, MD, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society, who recently described in his March 2018 blog what may the first signs of the effectiveness of efforts to promote protection from ultraviolet ray exposure (JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154[3]:361-2). He writes: “In young white women ages 15 to 24, the incidence of melanoma has declined an average of 5.5% per year from January 2005 through December 2014. Not 5.5% over those ten years but 5.5 % PER YEAR. That’s remarkable, to say the least.”

As for the reasons behind these trends, he says, “no one can say for certain,” but he refers to national data indicating that indoor tanning has decreased in the past few years, especially among adolescents and young adults.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

I was driving to work the other day, perched up in my pickup truck (somehow you knew that) and noticed a fancy race car in front of me with a vanity tag. It read HRTATTK 4. Well, I thought after four heart attacks maybe I would splurge on a special car too (more likely a newer truck). Then I noticed smoke coming out of the driver’s window, and I could see this guy in his side view mirror, presumably Mr. “Heart Attack 4,” puffing away on a cigarette. Wow.

Then I got to work and saw my secretary, who works with her oxygen on, out back puffing a cigarette. Wow.

It turns out that cigarette smoke contains substances that act as a monoamine oxidase (MAO) A inhibitor, prolonging the dopamine high in the brain (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Nov 26;93[24]:14065-9). Makes sense and may explain the above smoking behavior. I truly believe cigarettes are as or more addictive than any other dopamine enhancing drug.

More than 50 years ago, a national campaign against smoking was launched after the 1964 Surgeon General’s report concluded that smoking was a major health hazard. (Looking back, one of the few losses of not having to pull journal articles from the stacks in the library, is that medical students and residents can’t shake their heads in wonder at the cigarette ads in old medical journals.) The impact of the national antismoking campaign has been dramatic, but smoking remains the leading preventable cause of death in the United States and globally, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

in 2006, from 1992 (Arch Dermatol. 2010;146[3]:283-7), dermatologists had good footing on which to start a major prevention campaign. The American Cancer Society got on board, and in 2014, acting surgeon general Boris Lushniak, MD, issued a call to action to prevent skin cancer along with Howard Koh, MD, the assistant secretary of health, in “The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer” in 2014, and the campaign was on.

Well, I am delighted to pass on a report from Leonard Lichtenfeld, MD, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society, who recently described in his March 2018 blog what may the first signs of the effectiveness of efforts to promote protection from ultraviolet ray exposure (JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154[3]:361-2). He writes: “In young white women ages 15 to 24, the incidence of melanoma has declined an average of 5.5% per year from January 2005 through December 2014. Not 5.5% over those ten years but 5.5 % PER YEAR. That’s remarkable, to say the least.”

As for the reasons behind these trends, he says, “no one can say for certain,” but he refers to national data indicating that indoor tanning has decreased in the past few years, especially among adolescents and young adults.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Cancer-related clinical pearls from pediatric dermatology

KAUAI, HAWAII – Every child diagnosed with medulloblastoma deserves a careful dermatologic evaluation for possible comorbid basal cell nevus syndrome, according to Jennifer Huang, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

“Medulloblastoma occurs in 10%-20% of patients with basal cell nevus syndrome and can be the presenting sign. So if a patient with basal cell nevus syndrome gets medulloblastoma, it usually occurs within the first year of life – and it can be the first thing you see,” she said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Dr. Huang presented a series of pediatric dermatology clinical pearls focused not only on basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS) and medulloblastoma, but also on the implications of skin-limited Langerhans cell histiocytosis, how to recognize and treat drug-induced follicular eruptions in pediatric patients on targeted anticancer therapies, and when to suspect Demodex folliculitis in immunosuppressed patients.

Skin-limited Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Around 10%-20% of patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) have the skin-limited form of the malignancy. These are patients who, after a thorough workup, have a normal CBC, skeletal survey, and liver function tests; essentially, no evidence of multisystem disease.

“It’s very rare for patients who present with skin-limited LCH alone to develop multisystem disease and to require chemotherapy or other more aggressive treatment,” Dr. Huang said. “I think that skin-limited LCH is probably a separate entity with its own natural history distinct from multisystem disease. We can see that with current genomic testing: in multisystem LCH, BRAF mutations are identified in at least half of patients, but very few with skin-limited disease express those mutations.

“The clinical pearl here is if you have a patient with skin-limited LCH it very rarely progresses to multisystem involvement. It’s associated with a good prognosis. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t monitor them, but I think it can be reassuring information for the family,” she said.

Basal cell nevus syndrome and medulloblastoma

“Half of cases of medulloblastoma are associated with mutations in the sonic hedgehog pathway – and a subset of that group has basal cell nevus syndrome,” Dr. Huang said.

BCNS is not a diagnosis frequently made by oncologists, who typically dismiss the multitude of lesions as skin tags, which they often mimic in both appearance and location, particularly on the neck and intertriginous areas. So it’s useful for dermatologists to establish a good referral relationship with their local oncologists.

“As dermatologists it’s really important to recognize not only the major features of basal cell nevus syndrome, but also the associated findings because we can really help in making this diagnosis early,” Dr. Huang stressed.

Early diagnosis of BCNS is a high priority for two reasons: to start treatment aimed at reducing development of basal cell carcinomas, and because radiation therapy for their medulloblastoma is contraindicated in patients with BCNS because it boosts their skin cancer burden.

BCNS is caused by mutations in the PTCH (Patched) gene found on chromosome arm 9q. The major features of BCNS include odontogenic keratocysts, palmoplantar pits, ectopic calcification, and, of course, basal cell carcinomas. The associated findings in BCNS, in addition to medulloblastoma, include macrocephaly and dysmorphic features such as cleft lip or palate, frontal bossing, and hypertelorism.

“I’ve treated a hundred at a time. It’s incredibly successful. It’s locally destructive. It leaves a little bit of hypopigmentation but no scar, which the CO2 laser will do in this instance. It’s actually a pretty cool modality,” said Dr. Eichenfield, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego.

Follicular eruptions in cancer patients on MAPK inhibitors

Cutaneous reactions to anticancer drugs aimed at inhibiting the key MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathway in children are common and diverse. Dr. Huang focused on the most common one: follicular eruptions, which occur in up to 80% of pediatric cancer patients on targeted therapy. These eruptions can express themselves in a variety of ways and are easily mistaken for comedonal acne, varicella zoster infection, herpes simplex, or bacterial folliculitis.

The key clues are highly suggestive that a follicular eruption in a child on targeted anticancer therapy is caused by the drug and not something else are the eruption’s symmetric distribution, that it’s truly follicular upon close inspection, and the timing: The eruption typically begins 2-3 weeks after initiation of therapy or within a week after a dose escalation.

Anti-inflammatory agents are the treatment mainstay. Treatment of the cutaneous eruption often is successful without need to discontinue the patient’s MAPK inhibitor.

“Even though some of these eruptions look comedonal, they’re not. It’s not a follicular plugging disorder, it’s an inflammatory condition. Topical steroids, oral tetracyclines, and dilute bleach baths all work pretty well. I haven’t had good experiences with keratolytics like tretinoin cream and benzoyl peroxide; they’re less effective. Dose reduction is the last resort for these patients. Often they are very sick. They need the drug and I think the last thing we want to do is take them off it,” Dr. Huang said.

She has observed that prepubertal children are more likely to have an eczematous reaction to their targeted anticancer therapy than a follicular eruption.

D. folliculitis in immunocompromised patients

“The clinical pearl here is to strongly consider the diagnosis of Demodex folliculitis in an immunosuppresed patient with an itchy acneiform eruption,” Dr. Huang said.

Demodex is a human mite which is part of the normal skin flora. She called it “a great mimicker”: It can cause dermatoses mistaken for rosacea, acne, seborrheic dermatitis, perioral facial dermatitis, blepharitis, and acute graft-versus-host disease.

In the setting of a young, immunosuppressed patient who develops an acneiform eruption, the differential diagnosis is lengthy and includes steroid-induced acne, a cutaneous reaction to targeted anticancer therapy, gram-negative folliculitis secondary to long-term antibiotic therapy, and Pityrosporum folliculitis, as well as D. folliculitis.

Demodex and P. folliculitis are the two acneiform dermatoses where itch figures prominently. A couple of clues are helpful in differentiating the two conditions: P. folliculitis often involves the chest and back, while D. folliculitis generally spares the trunk and is focused on the face and neck. And D. folliculitis typically arises when immunosuppression is weaned. Overgrowth of the mites occurs during immunosuppression, then as the immunosuppression is lifted a prominent inflammatory response with an acne-like appearance occurs.

Dr. Huang usually sticks with topical therapies for D. folliculitis. These include topical sulfur 5%, permethrin 5%, metronidazole, and/or ivermectin. If a young patient is unresponsive to this panoply of topical agents, she resorts to a single dose of oral ivermectin at 0.2 mg/kg, usually with good effect.

Dr. Huang reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

The SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – Every child diagnosed with medulloblastoma deserves a careful dermatologic evaluation for possible comorbid basal cell nevus syndrome, according to Jennifer Huang, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

“Medulloblastoma occurs in 10%-20% of patients with basal cell nevus syndrome and can be the presenting sign. So if a patient with basal cell nevus syndrome gets medulloblastoma, it usually occurs within the first year of life – and it can be the first thing you see,” she said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Dr. Huang presented a series of pediatric dermatology clinical pearls focused not only on basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS) and medulloblastoma, but also on the implications of skin-limited Langerhans cell histiocytosis, how to recognize and treat drug-induced follicular eruptions in pediatric patients on targeted anticancer therapies, and when to suspect Demodex folliculitis in immunosuppressed patients.

Skin-limited Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Around 10%-20% of patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) have the skin-limited form of the malignancy. These are patients who, after a thorough workup, have a normal CBC, skeletal survey, and liver function tests; essentially, no evidence of multisystem disease.

“It’s very rare for patients who present with skin-limited LCH alone to develop multisystem disease and to require chemotherapy or other more aggressive treatment,” Dr. Huang said. “I think that skin-limited LCH is probably a separate entity with its own natural history distinct from multisystem disease. We can see that with current genomic testing: in multisystem LCH, BRAF mutations are identified in at least half of patients, but very few with skin-limited disease express those mutations.

“The clinical pearl here is if you have a patient with skin-limited LCH it very rarely progresses to multisystem involvement. It’s associated with a good prognosis. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t monitor them, but I think it can be reassuring information for the family,” she said.

Basal cell nevus syndrome and medulloblastoma

“Half of cases of medulloblastoma are associated with mutations in the sonic hedgehog pathway – and a subset of that group has basal cell nevus syndrome,” Dr. Huang said.

BCNS is not a diagnosis frequently made by oncologists, who typically dismiss the multitude of lesions as skin tags, which they often mimic in both appearance and location, particularly on the neck and intertriginous areas. So it’s useful for dermatologists to establish a good referral relationship with their local oncologists.

“As dermatologists it’s really important to recognize not only the major features of basal cell nevus syndrome, but also the associated findings because we can really help in making this diagnosis early,” Dr. Huang stressed.

Early diagnosis of BCNS is a high priority for two reasons: to start treatment aimed at reducing development of basal cell carcinomas, and because radiation therapy for their medulloblastoma is contraindicated in patients with BCNS because it boosts their skin cancer burden.

BCNS is caused by mutations in the PTCH (Patched) gene found on chromosome arm 9q. The major features of BCNS include odontogenic keratocysts, palmoplantar pits, ectopic calcification, and, of course, basal cell carcinomas. The associated findings in BCNS, in addition to medulloblastoma, include macrocephaly and dysmorphic features such as cleft lip or palate, frontal bossing, and hypertelorism.

“I’ve treated a hundred at a time. It’s incredibly successful. It’s locally destructive. It leaves a little bit of hypopigmentation but no scar, which the CO2 laser will do in this instance. It’s actually a pretty cool modality,” said Dr. Eichenfield, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego.

Follicular eruptions in cancer patients on MAPK inhibitors

Cutaneous reactions to anticancer drugs aimed at inhibiting the key MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathway in children are common and diverse. Dr. Huang focused on the most common one: follicular eruptions, which occur in up to 80% of pediatric cancer patients on targeted therapy. These eruptions can express themselves in a variety of ways and are easily mistaken for comedonal acne, varicella zoster infection, herpes simplex, or bacterial folliculitis.

The key clues are highly suggestive that a follicular eruption in a child on targeted anticancer therapy is caused by the drug and not something else are the eruption’s symmetric distribution, that it’s truly follicular upon close inspection, and the timing: The eruption typically begins 2-3 weeks after initiation of therapy or within a week after a dose escalation.

Anti-inflammatory agents are the treatment mainstay. Treatment of the cutaneous eruption often is successful without need to discontinue the patient’s MAPK inhibitor.

“Even though some of these eruptions look comedonal, they’re not. It’s not a follicular plugging disorder, it’s an inflammatory condition. Topical steroids, oral tetracyclines, and dilute bleach baths all work pretty well. I haven’t had good experiences with keratolytics like tretinoin cream and benzoyl peroxide; they’re less effective. Dose reduction is the last resort for these patients. Often they are very sick. They need the drug and I think the last thing we want to do is take them off it,” Dr. Huang said.

She has observed that prepubertal children are more likely to have an eczematous reaction to their targeted anticancer therapy than a follicular eruption.

D. folliculitis in immunocompromised patients

“The clinical pearl here is to strongly consider the diagnosis of Demodex folliculitis in an immunosuppresed patient with an itchy acneiform eruption,” Dr. Huang said.

Demodex is a human mite which is part of the normal skin flora. She called it “a great mimicker”: It can cause dermatoses mistaken for rosacea, acne, seborrheic dermatitis, perioral facial dermatitis, blepharitis, and acute graft-versus-host disease.

In the setting of a young, immunosuppressed patient who develops an acneiform eruption, the differential diagnosis is lengthy and includes steroid-induced acne, a cutaneous reaction to targeted anticancer therapy, gram-negative folliculitis secondary to long-term antibiotic therapy, and Pityrosporum folliculitis, as well as D. folliculitis.

Demodex and P. folliculitis are the two acneiform dermatoses where itch figures prominently. A couple of clues are helpful in differentiating the two conditions: P. folliculitis often involves the chest and back, while D. folliculitis generally spares the trunk and is focused on the face and neck. And D. folliculitis typically arises when immunosuppression is weaned. Overgrowth of the mites occurs during immunosuppression, then as the immunosuppression is lifted a prominent inflammatory response with an acne-like appearance occurs.

Dr. Huang usually sticks with topical therapies for D. folliculitis. These include topical sulfur 5%, permethrin 5%, metronidazole, and/or ivermectin. If a young patient is unresponsive to this panoply of topical agents, she resorts to a single dose of oral ivermectin at 0.2 mg/kg, usually with good effect.

Dr. Huang reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

The SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

KAUAI, HAWAII – Every child diagnosed with medulloblastoma deserves a careful dermatologic evaluation for possible comorbid basal cell nevus syndrome, according to Jennifer Huang, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

“Medulloblastoma occurs in 10%-20% of patients with basal cell nevus syndrome and can be the presenting sign. So if a patient with basal cell nevus syndrome gets medulloblastoma, it usually occurs within the first year of life – and it can be the first thing you see,” she said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

Dr. Huang presented a series of pediatric dermatology clinical pearls focused not only on basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS) and medulloblastoma, but also on the implications of skin-limited Langerhans cell histiocytosis, how to recognize and treat drug-induced follicular eruptions in pediatric patients on targeted anticancer therapies, and when to suspect Demodex folliculitis in immunosuppressed patients.

Skin-limited Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Around 10%-20% of patients with Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) have the skin-limited form of the malignancy. These are patients who, after a thorough workup, have a normal CBC, skeletal survey, and liver function tests; essentially, no evidence of multisystem disease.

“It’s very rare for patients who present with skin-limited LCH alone to develop multisystem disease and to require chemotherapy or other more aggressive treatment,” Dr. Huang said. “I think that skin-limited LCH is probably a separate entity with its own natural history distinct from multisystem disease. We can see that with current genomic testing: in multisystem LCH, BRAF mutations are identified in at least half of patients, but very few with skin-limited disease express those mutations.

“The clinical pearl here is if you have a patient with skin-limited LCH it very rarely progresses to multisystem involvement. It’s associated with a good prognosis. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t monitor them, but I think it can be reassuring information for the family,” she said.

Basal cell nevus syndrome and medulloblastoma

“Half of cases of medulloblastoma are associated with mutations in the sonic hedgehog pathway – and a subset of that group has basal cell nevus syndrome,” Dr. Huang said.

BCNS is not a diagnosis frequently made by oncologists, who typically dismiss the multitude of lesions as skin tags, which they often mimic in both appearance and location, particularly on the neck and intertriginous areas. So it’s useful for dermatologists to establish a good referral relationship with their local oncologists.

“As dermatologists it’s really important to recognize not only the major features of basal cell nevus syndrome, but also the associated findings because we can really help in making this diagnosis early,” Dr. Huang stressed.

Early diagnosis of BCNS is a high priority for two reasons: to start treatment aimed at reducing development of basal cell carcinomas, and because radiation therapy for their medulloblastoma is contraindicated in patients with BCNS because it boosts their skin cancer burden.

BCNS is caused by mutations in the PTCH (Patched) gene found on chromosome arm 9q. The major features of BCNS include odontogenic keratocysts, palmoplantar pits, ectopic calcification, and, of course, basal cell carcinomas. The associated findings in BCNS, in addition to medulloblastoma, include macrocephaly and dysmorphic features such as cleft lip or palate, frontal bossing, and hypertelorism.

“I’ve treated a hundred at a time. It’s incredibly successful. It’s locally destructive. It leaves a little bit of hypopigmentation but no scar, which the CO2 laser will do in this instance. It’s actually a pretty cool modality,” said Dr. Eichenfield, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego.

Follicular eruptions in cancer patients on MAPK inhibitors

Cutaneous reactions to anticancer drugs aimed at inhibiting the key MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathway in children are common and diverse. Dr. Huang focused on the most common one: follicular eruptions, which occur in up to 80% of pediatric cancer patients on targeted therapy. These eruptions can express themselves in a variety of ways and are easily mistaken for comedonal acne, varicella zoster infection, herpes simplex, or bacterial folliculitis.

The key clues are highly suggestive that a follicular eruption in a child on targeted anticancer therapy is caused by the drug and not something else are the eruption’s symmetric distribution, that it’s truly follicular upon close inspection, and the timing: The eruption typically begins 2-3 weeks after initiation of therapy or within a week after a dose escalation.

Anti-inflammatory agents are the treatment mainstay. Treatment of the cutaneous eruption often is successful without need to discontinue the patient’s MAPK inhibitor.

“Even though some of these eruptions look comedonal, they’re not. It’s not a follicular plugging disorder, it’s an inflammatory condition. Topical steroids, oral tetracyclines, and dilute bleach baths all work pretty well. I haven’t had good experiences with keratolytics like tretinoin cream and benzoyl peroxide; they’re less effective. Dose reduction is the last resort for these patients. Often they are very sick. They need the drug and I think the last thing we want to do is take them off it,” Dr. Huang said.

She has observed that prepubertal children are more likely to have an eczematous reaction to their targeted anticancer therapy than a follicular eruption.

D. folliculitis in immunocompromised patients

“The clinical pearl here is to strongly consider the diagnosis of Demodex folliculitis in an immunosuppresed patient with an itchy acneiform eruption,” Dr. Huang said.

Demodex is a human mite which is part of the normal skin flora. She called it “a great mimicker”: It can cause dermatoses mistaken for rosacea, acne, seborrheic dermatitis, perioral facial dermatitis, blepharitis, and acute graft-versus-host disease.

In the setting of a young, immunosuppressed patient who develops an acneiform eruption, the differential diagnosis is lengthy and includes steroid-induced acne, a cutaneous reaction to targeted anticancer therapy, gram-negative folliculitis secondary to long-term antibiotic therapy, and Pityrosporum folliculitis, as well as D. folliculitis.

Demodex and P. folliculitis are the two acneiform dermatoses where itch figures prominently. A couple of clues are helpful in differentiating the two conditions: P. folliculitis often involves the chest and back, while D. folliculitis generally spares the trunk and is focused on the face and neck. And D. folliculitis typically arises when immunosuppression is weaned. Overgrowth of the mites occurs during immunosuppression, then as the immunosuppression is lifted a prominent inflammatory response with an acne-like appearance occurs.

Dr. Huang usually sticks with topical therapies for D. folliculitis. These include topical sulfur 5%, permethrin 5%, metronidazole, and/or ivermectin. If a young patient is unresponsive to this panoply of topical agents, she resorts to a single dose of oral ivermectin at 0.2 mg/kg, usually with good effect.

Dr. Huang reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

The SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Spontaneous Regression of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, rapidly growing, aggressive neoplasm with a generally poor prognosis. The cells of origin are highly anaplastic and share structural and immunohistochemical features with various neuroectodermally derived cells. Although Merkel cells, which are slow-acting cutaneous mechanoreceptors located in the basal layer of the epidermis, and MCC share immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features, there is limited evidence of a direct histogenetic relationship between the two.1,2 Additionally, some extracutaneous neuroendocrine tumors have features similar to MCC; therefore, although it may be more accurate and perhaps more practical to describe these lesions as primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin, the term MCC is more commonly used both in the literature and in clinical practice.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma typically presents in the head and neck region in white patients older than 70 years of age and in the immunocompromised population.3-6 The mean age of diagnosis is 76 years for women and 74 years for men.7 The incidence of MCC in the United States tripled over a 15-year period, and there are approximately 1500 new cases of MCC diagnosed each year, making it about 40 times less common than melanoma.8 The 5-year survival rate for patients without lymph node involvement is 75%, whereas the 5-year survival rate for patients with distant metastases is 25%.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is thought to develop through 1 of 2 distinct pathways. In a virally mediated pathway, which represents at least 80% of cases, the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV) monoclonally integrates into the host genome and promotes oncogenesis via altered p53 and retinoblastoma protein expression.10-12 The remainder of cases are believed to develop via a nonvirally mediated pathway in which genetic anomalies, immune status, and environmental factors influence oncogenesis.10-13

Due to the similarity between MCC and metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, especially small-cell lung carcinomas, immunohistochemistry is important in making the diagnosis. Cytokeratin 20 and neuron-specific enolase positivity and thyroid transcription factor 1 negativity are the most useful markers in identifying MCC.

Regression of MCC is a very rare and poorly understood event. A 2010 review of the literature described 22 cases of spontaneous regression.14 We report a rare case of rapid and complete regression of MCC following punch biopsy in a 96-year-old woman.

Case Report

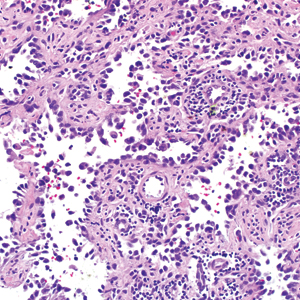

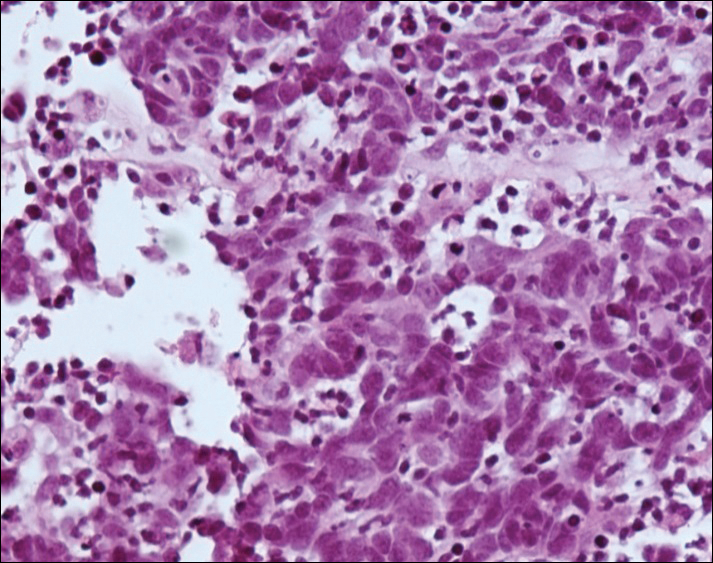

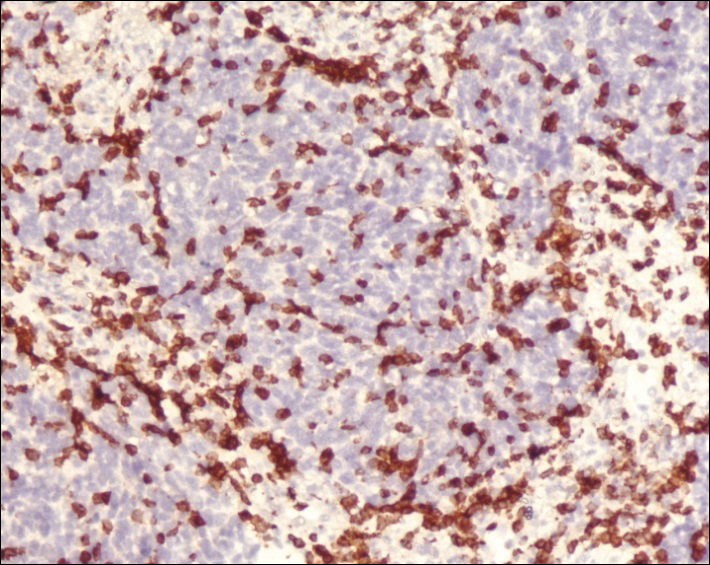

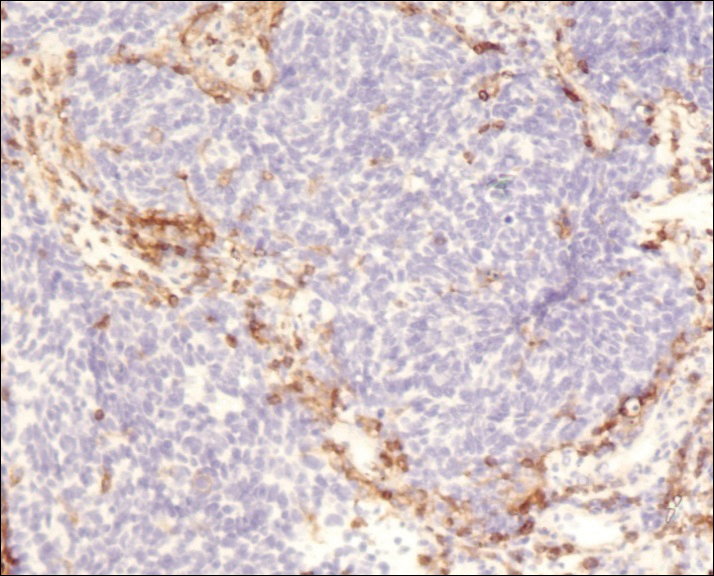

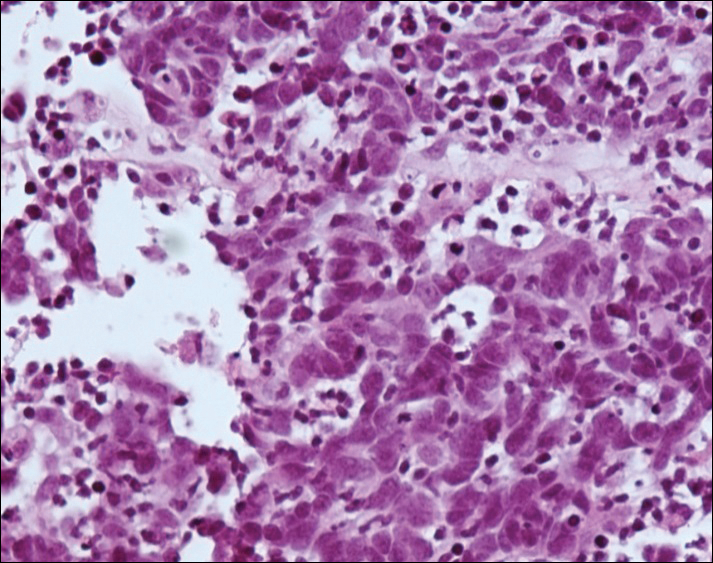

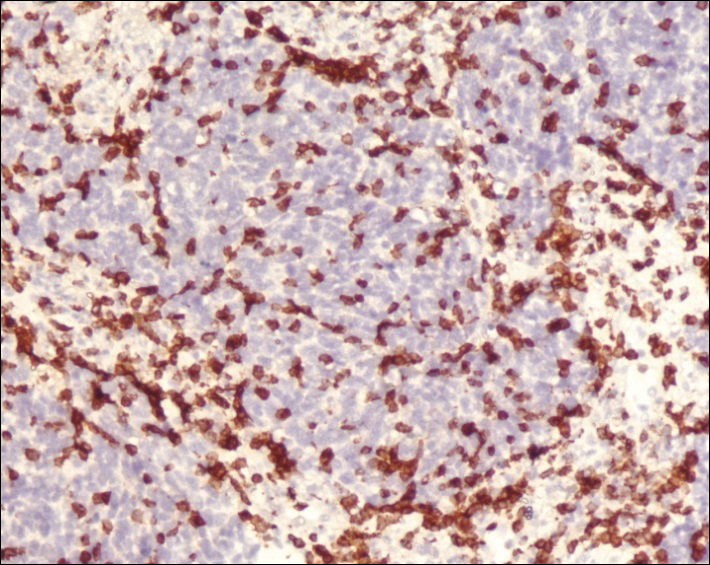

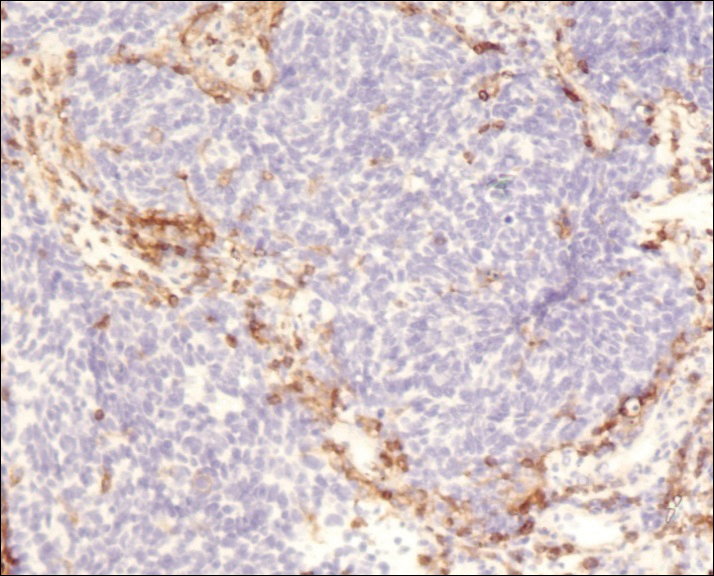

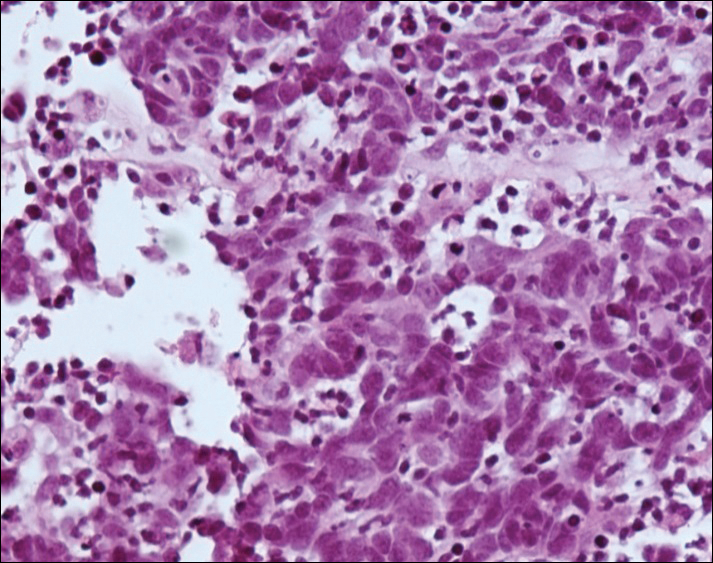

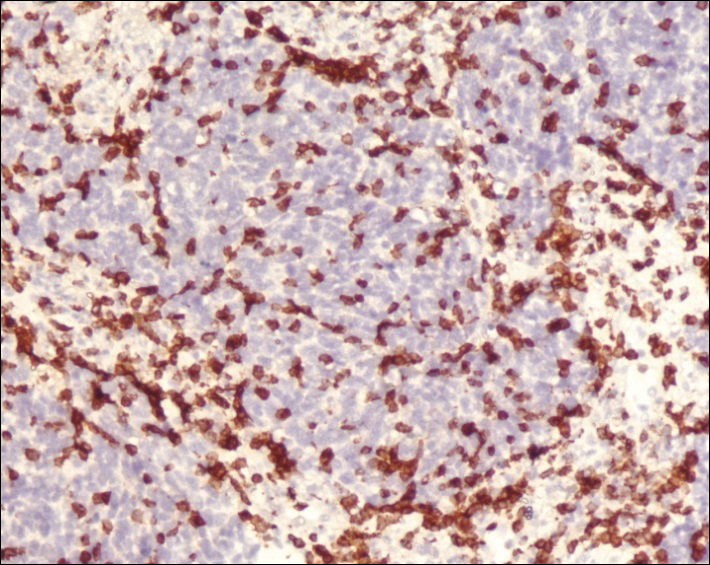

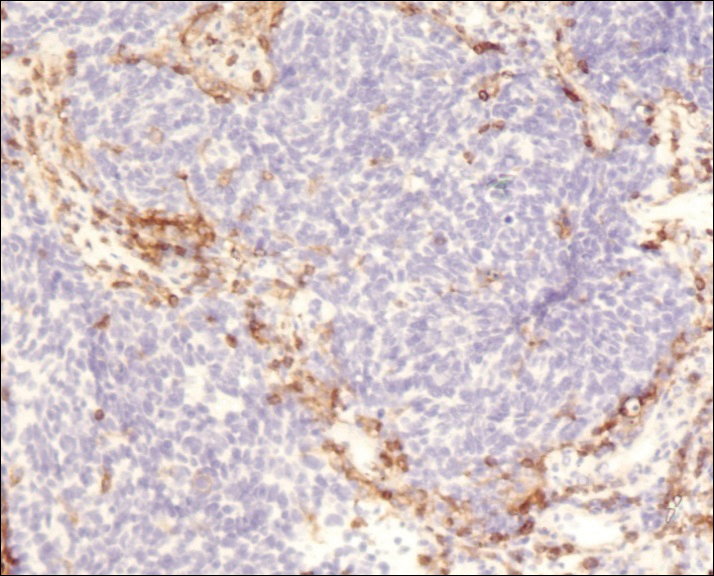

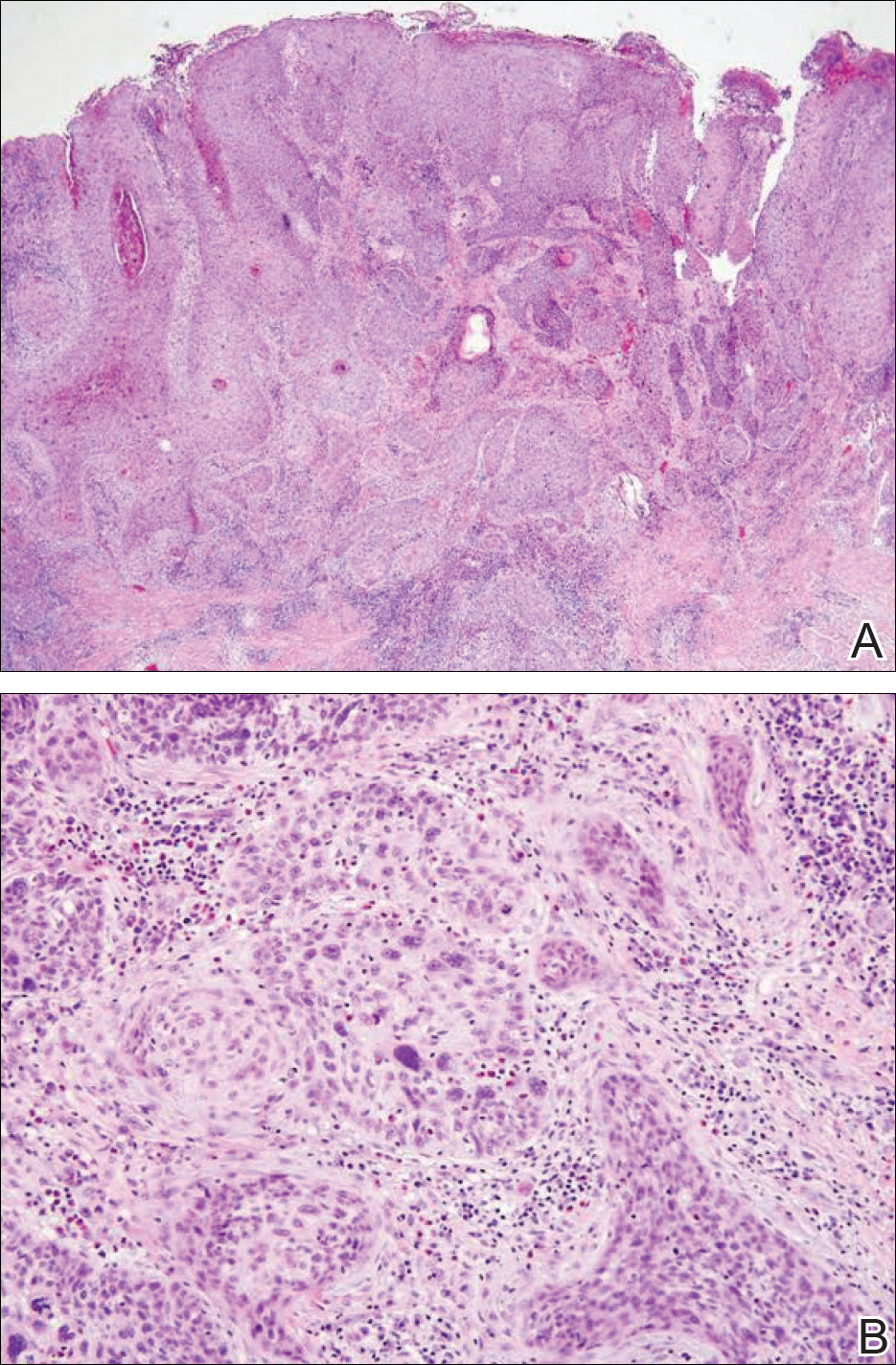

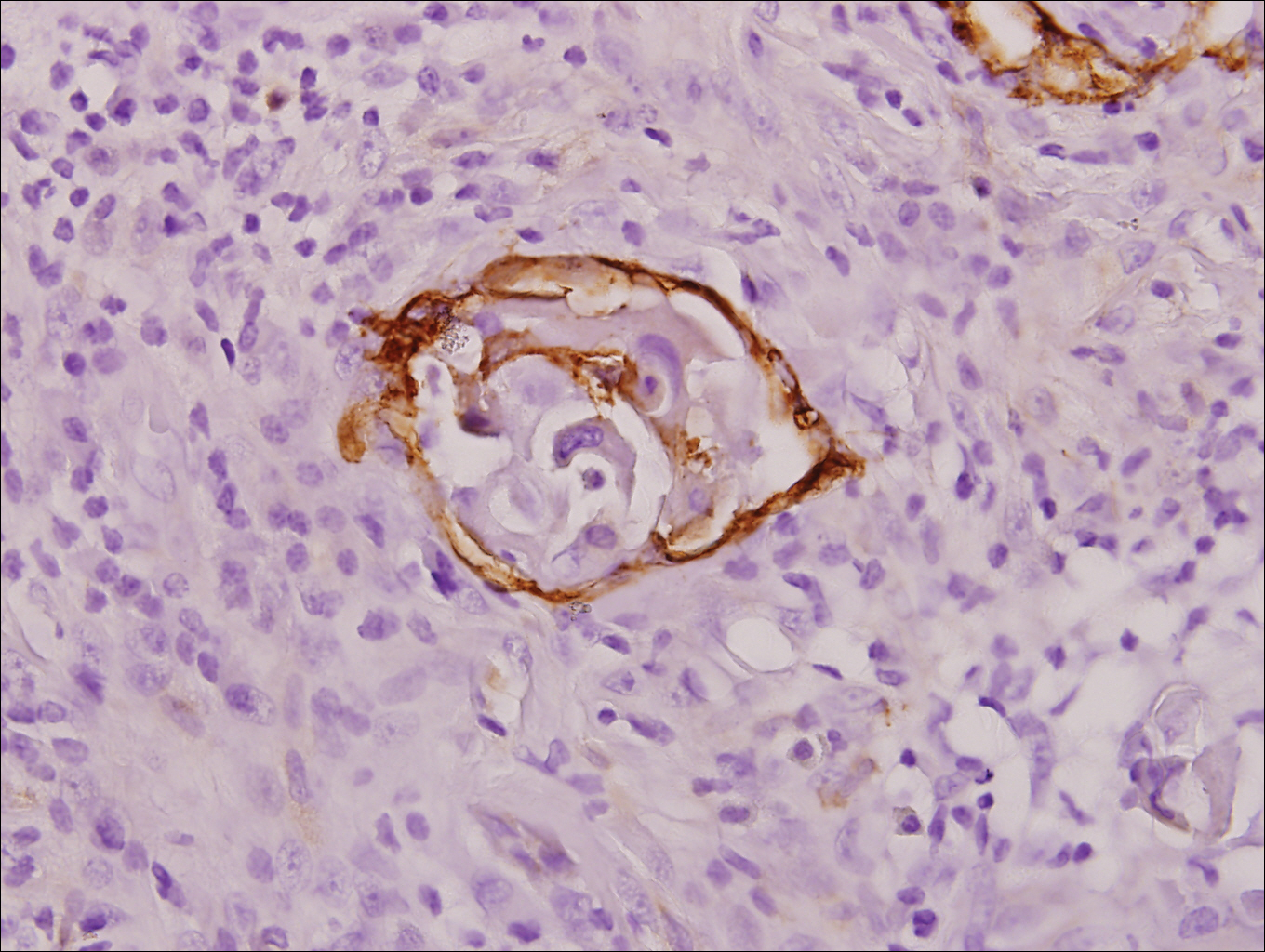

A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained at a follow-up visit 4 weeks later (12 weeks after the reported onset of the lesion). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed a small-cell neoplasm with stippled nuclei and scant cytoplasm forming a nested and somewhat trabecular pattern. Mitotic activity, apoptosis, and nuclear molding also were present (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 20 with a dotlike, paranuclear pattern (Figure 3). Staining for CAM 5.2 also was positive. Cytokeratin 5/6, human melanoma black 45, and leukocyte common antigen were negative. The immunophenotyping of the lymphocytic response to the tumor showed that the majority of intratumoral lymphocytes were CD8 positive (Figure 4). CD4-positive lymphocytes were predominantly seen at the periphery of the tumor nests without tumor infiltration (Figure 5). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of MCC was made. The patient’s family declined treatment based on her advanced age and current health status, which included advanced dementia.

Two weeks after the punch biopsy, the lesion had noticeably decreased in size and lost its dome-shaped appearance. Within 8 weeks after biopsy (20 weeks since the lesion first appeared), the lesion had completely resolved (Figure 6). The patient was lost to follow-up months later, but no recurrence of the lesion was reported.

Comment

Spontaneous regression is not unique to MCC, as this phenomenon also has been reported in keratoacanthoma, lymphoma, basal cell carcinoma, and melanoma.15 Complete spontaneous regression is defined as occurring in the absence of therapy that is intended to have a treatment effect.15,16 Spontaneous regression is estimated to occur in malignant neoplasms at a rate of 1 case per 60,000 to 100,000 (approximately 0.0013% of all malignant neoplasms).17 Considering the reported prevalence of MCC and the number of cases that have been known to regress, the estimated incidence of complete spontaneous regression may be as high as 1.5%.14 Though spontaneous regression of MCC is more prevalent than expected, it still is considered a rare phenomenon. A 2010 review of the literature yielded 22 cases of complete spontaneous regression of MCC.14 No recurrences have been observed; however, follow-up was relatively short in some cases.

In a unique report by Bertolotti et al,18 a patient with MCC on the nasal tip presented 4 weeks after biopsy with complete spontaneous regression of the tumor, which was associated with bilateral cervical lymph node involvement as noted by hypermetabolic uptake on positron emission tomography scanning. The patient underwent radiation therapy and was disease free at 12 months’ follow-up.18

Complete spontaneous regression has been described in MCC patients with local disease, regional recurrences, and metastatic disease.19 In

The histopathologic features observed in our case, specifically intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells, were similar to the findings in other reported cases. In one series of 2 cases, the one case showed scar tissue with a moderate, predominantly T-lymphocytic infiltrate and no tumor cells, and the second showed cellular proliferation in the deep dermis with dense lymphocytic infiltrates primarily composed of CD3-positive T cells.14 Other studies of regression of both localized and metastatic MCC demonstrated infiltration by CD4-positive, CD8-positive, and CD3-positive lymphocytes and foamy macrophages.21-23

The discovery of the MCV was one of the most important advances in elucidating the pathogenesis of MCC.10,24-26 Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA has been detected in a majority of MCC cases.25,27 Viral integration has been shown to take place early, prior to tumor clonal expansion.10 Importantly, not all cases of MCC show MCV infection, and MCV infection is not exclusive to MCC.28 Merkel cell polyomavirus is considered to be part of the normal human flora, and asymptomatic infection is quite common.29 It has been identified in 80% of adults older than 50 years of age and, interestingly, in 35% of children by 13 years of age or younger.30,31 It remains unclear what role the presence of MCV plays in determining MCC prognosis. Several reports have demonstrated lower disease-specific mortality associated with MCV-positive MCC.32-35 In contrast, Schrama et al36 correlated the MCV status of 174 MCC tumors and found no difference in clinical behavior or prognosis between MCV-positive and MCV-negative MCCs.

Immunosuppression also may play a role in the development of MCC.5,25 There is increased prevalence of MCC in the human immunodeficiency virus–positive population, as well as in organ-transplant recipients and patients with leukemia. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia seems to be the most frequent neoplasia associated with development of MCC.37

The mechanism of MCC regression remains unclear, but many investigators emphasize the importance of T-cell–mediated immunity.16,21-23,38,39 Apoptosis also has been shown to play an important role.40 Our case showed tumor-infiltrating CD8-positive lymphocytes and CD4-positive lymphocytes present predominantly at the periphery of the tumor, with close proximity to the tumor nests but with no tumor infiltration (Figure 3). This distribution was consistently present in multiple sections of the tumor. These findings are consistent with prior reports of both CD4-positive and CD8-positive T lymphocytes associated with MCC regression. Our findings confirm that immune response may play an important role in spontaneous regression of MCC.

There is much speculation regarding the initial biopsy of an MCC lesion (or other traumatic event) and its role in tumor regression. Koba et al41 examined the effect of biopsy on CD8-positive lymphocytic infiltration of MCC tumor cells and found that biopsy does not commonly alter intratumoral CD8-positive infiltration. These findings suggest trauma does not directly induce immunologic recognition of this cancer.

Conclusion

We report a case of complete spontaneous regression of a localized MCC following a punch biopsy. The histopathology showed a brisk T-lymphocyte response with intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells. The age and clinical profile of our patient as well as the clinicopathologic characteristics of the tumor regression are similar to other reported cases. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of MCC regression, and a better understanding of this fascinating phenomenon could help in development of new immunotherapeutic approaches.

- Sibley RK, Dehner LP, Rosai J. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin. I. a clinicopathologic and ultrastructural study of 43 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:95-108.

- Sibley RK, Dahl D. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin. II. an immunocytochemical study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:109-116.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

- Gooptu C, Woolloons A, Ross J, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma arising after therapeutic immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:637-641.

- Plunkett TA, Harris AJ, Ogg CS, et al. The treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma and its association with immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:345-346.

- Calder KB, Smoller BR. New insights into Merkel cell carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:155-161.

- Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

- Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100.

- Amber K, McLeod MP, Nouri K. The Merkel cell polyomavirus and its involvement in Merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:232-238.

- Decaprio JA. Does detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma provide prognostic information? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:905-907.

- Popp S, Waltering S, Herbst C, et al. UV-B-type mutations and chromosomal imbalances indicate common pathways for the development of Merkel and skin squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:352-360.

- Ciudad C, Avilés JA, Alfageme F, et al. Spontaneous regression in Merkel cell carcinoma: report of two cases with description of dermoscopic features and review of literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:687-693.

- O’Rourke MGE, Bell JR. Merkel cell tumor with spontaneous regression. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986;12:994-997.

- Connelly TJ, Cribier B, Brown TJ, et al. Complete spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a review of 10 reported cases. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:853-856.

- Cole WH. Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:201-209.

- Bertolotti A, Conte H, Francois L, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: complete clinical remission associated with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:501-502.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature [published online November 13, 2014]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- Richetta AG, Mancini M, Torroni A, et al. Total spontaneous regression of advanced Merkel cell carcinoma after biopsy: review and a new case. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:815-822.

- Vesely MJ, Murray DJ, Neligan PC, et al. Complete spontaneous regression in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:165-171.

- Kayashima K, Ono T, Johno M, et al. Spontaneous regression in Merkel cell (neuroendocrine) carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:550-553.

- Maruo K, Kayashima KI, Ono T. Regressing Merkel cell carcinoma-a case showing replacement of tumour cells by foamy cells. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1184-1189.

- Duncavage E, Zehnbauer B, Pfeifer J. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:516-521.

- Kassem A, Schopflin A, Diaz C, et al. Frequent detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinomas and identification of unique deletion in the VP1 gene. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5009-5013.

- Becker J, Schrama D, Houben R. Merkel cell carcinoma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1-8.

- Haitz KA, Rady PL, Nguyen HP, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA detection in a patient with Merkel cell carcinoma and multiple other skin cancers. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:442-444.

- Andres C, Puchta U, Sander CA, et al. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA in cutaneous lymphomas, pseudolymphomas, and inflammatory skin diseases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:593-598.

- Showalter RM, Pastrana DV, Pumphrey KA, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and two previously unknown polyomaviruses are chronically shed from human skin. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:509-515.

- Tolstov YL, Pastrana DV, Feng H, et al. Human Merkel cell polyomavirus infection II. MCV is a common human infection that can be detected by conformational capsid epitope immunoassays. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1250-1256.

- Chen T, Hedman L, Mattila PS, et al. Serological evidence of Merkel cell polyomavirus primary infections in childhood. J Clin Virol. 2011;50:125-129.

- Laude HC, Jonchère B, Maubec E, et al. Distinct Merkel cell polyomavirus molecular features in tumour and non tumour specimens from patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001076.

- Waltari M, Sihto H, Kukko H, et al. Association of Merkel cell polyomavirus infection with tumor p53, KIT, stem cell factor, PDGFR-alpha and survival in Merkel cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:619-628.

- Sihto H, Kukko H, Koljonen V, et al. Clinical factors associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:938-945.

- Paulson KG, Lemos BD, Feng B, et al. Array-CGH reveals recurrent genomic changes in Merkel cell carcinoma including amplification of L-Myc. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1547-1555.

- Schrama D, Peitsch WK, Zapatka M, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus status is not associated with clinical course of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1631-1638.

- Tadmor T, Aviv A, Polliack A. Merkel cell carcinoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other lymphoproliferative disorders: an old bond with possible new viral ties. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:250-256.

- Wooff J, Trites JR, Walsh NM, et al. Complete spontaneous regression of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:614-617.

- Turk TO, Smoljan I, Nacinovic A, et al. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7270.

- Mori Y, Tanaka K, Cui CY, et al. A study of apoptosis in Merkel cell carcinoma. an immunohistochemical, ultrasctructural, DNA ladder and TUNEL labeling study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:16-23.

- Koba S, Paulson KG, Nagase K, et al. Diagnostic biopsy does not commonly induce intratumoral CD8 T cell infiltration in Merkel cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41465.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, rapidly growing, aggressive neoplasm with a generally poor prognosis. The cells of origin are highly anaplastic and share structural and immunohistochemical features with various neuroectodermally derived cells. Although Merkel cells, which are slow-acting cutaneous mechanoreceptors located in the basal layer of the epidermis, and MCC share immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features, there is limited evidence of a direct histogenetic relationship between the two.1,2 Additionally, some extracutaneous neuroendocrine tumors have features similar to MCC; therefore, although it may be more accurate and perhaps more practical to describe these lesions as primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin, the term MCC is more commonly used both in the literature and in clinical practice.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma typically presents in the head and neck region in white patients older than 70 years of age and in the immunocompromised population.3-6 The mean age of diagnosis is 76 years for women and 74 years for men.7 The incidence of MCC in the United States tripled over a 15-year period, and there are approximately 1500 new cases of MCC diagnosed each year, making it about 40 times less common than melanoma.8 The 5-year survival rate for patients without lymph node involvement is 75%, whereas the 5-year survival rate for patients with distant metastases is 25%.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is thought to develop through 1 of 2 distinct pathways. In a virally mediated pathway, which represents at least 80% of cases, the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV) monoclonally integrates into the host genome and promotes oncogenesis via altered p53 and retinoblastoma protein expression.10-12 The remainder of cases are believed to develop via a nonvirally mediated pathway in which genetic anomalies, immune status, and environmental factors influence oncogenesis.10-13

Due to the similarity between MCC and metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, especially small-cell lung carcinomas, immunohistochemistry is important in making the diagnosis. Cytokeratin 20 and neuron-specific enolase positivity and thyroid transcription factor 1 negativity are the most useful markers in identifying MCC.

Regression of MCC is a very rare and poorly understood event. A 2010 review of the literature described 22 cases of spontaneous regression.14 We report a rare case of rapid and complete regression of MCC following punch biopsy in a 96-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained at a follow-up visit 4 weeks later (12 weeks after the reported onset of the lesion). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed a small-cell neoplasm with stippled nuclei and scant cytoplasm forming a nested and somewhat trabecular pattern. Mitotic activity, apoptosis, and nuclear molding also were present (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 20 with a dotlike, paranuclear pattern (Figure 3). Staining for CAM 5.2 also was positive. Cytokeratin 5/6, human melanoma black 45, and leukocyte common antigen were negative. The immunophenotyping of the lymphocytic response to the tumor showed that the majority of intratumoral lymphocytes were CD8 positive (Figure 4). CD4-positive lymphocytes were predominantly seen at the periphery of the tumor nests without tumor infiltration (Figure 5). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of MCC was made. The patient’s family declined treatment based on her advanced age and current health status, which included advanced dementia.

Two weeks after the punch biopsy, the lesion had noticeably decreased in size and lost its dome-shaped appearance. Within 8 weeks after biopsy (20 weeks since the lesion first appeared), the lesion had completely resolved (Figure 6). The patient was lost to follow-up months later, but no recurrence of the lesion was reported.

Comment

Spontaneous regression is not unique to MCC, as this phenomenon also has been reported in keratoacanthoma, lymphoma, basal cell carcinoma, and melanoma.15 Complete spontaneous regression is defined as occurring in the absence of therapy that is intended to have a treatment effect.15,16 Spontaneous regression is estimated to occur in malignant neoplasms at a rate of 1 case per 60,000 to 100,000 (approximately 0.0013% of all malignant neoplasms).17 Considering the reported prevalence of MCC and the number of cases that have been known to regress, the estimated incidence of complete spontaneous regression may be as high as 1.5%.14 Though spontaneous regression of MCC is more prevalent than expected, it still is considered a rare phenomenon. A 2010 review of the literature yielded 22 cases of complete spontaneous regression of MCC.14 No recurrences have been observed; however, follow-up was relatively short in some cases.

In a unique report by Bertolotti et al,18 a patient with MCC on the nasal tip presented 4 weeks after biopsy with complete spontaneous regression of the tumor, which was associated with bilateral cervical lymph node involvement as noted by hypermetabolic uptake on positron emission tomography scanning. The patient underwent radiation therapy and was disease free at 12 months’ follow-up.18

Complete spontaneous regression has been described in MCC patients with local disease, regional recurrences, and metastatic disease.19 In

The histopathologic features observed in our case, specifically intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells, were similar to the findings in other reported cases. In one series of 2 cases, the one case showed scar tissue with a moderate, predominantly T-lymphocytic infiltrate and no tumor cells, and the second showed cellular proliferation in the deep dermis with dense lymphocytic infiltrates primarily composed of CD3-positive T cells.14 Other studies of regression of both localized and metastatic MCC demonstrated infiltration by CD4-positive, CD8-positive, and CD3-positive lymphocytes and foamy macrophages.21-23

The discovery of the MCV was one of the most important advances in elucidating the pathogenesis of MCC.10,24-26 Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA has been detected in a majority of MCC cases.25,27 Viral integration has been shown to take place early, prior to tumor clonal expansion.10 Importantly, not all cases of MCC show MCV infection, and MCV infection is not exclusive to MCC.28 Merkel cell polyomavirus is considered to be part of the normal human flora, and asymptomatic infection is quite common.29 It has been identified in 80% of adults older than 50 years of age and, interestingly, in 35% of children by 13 years of age or younger.30,31 It remains unclear what role the presence of MCV plays in determining MCC prognosis. Several reports have demonstrated lower disease-specific mortality associated with MCV-positive MCC.32-35 In contrast, Schrama et al36 correlated the MCV status of 174 MCC tumors and found no difference in clinical behavior or prognosis between MCV-positive and MCV-negative MCCs.

Immunosuppression also may play a role in the development of MCC.5,25 There is increased prevalence of MCC in the human immunodeficiency virus–positive population, as well as in organ-transplant recipients and patients with leukemia. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia seems to be the most frequent neoplasia associated with development of MCC.37

The mechanism of MCC regression remains unclear, but many investigators emphasize the importance of T-cell–mediated immunity.16,21-23,38,39 Apoptosis also has been shown to play an important role.40 Our case showed tumor-infiltrating CD8-positive lymphocytes and CD4-positive lymphocytes present predominantly at the periphery of the tumor, with close proximity to the tumor nests but with no tumor infiltration (Figure 3). This distribution was consistently present in multiple sections of the tumor. These findings are consistent with prior reports of both CD4-positive and CD8-positive T lymphocytes associated with MCC regression. Our findings confirm that immune response may play an important role in spontaneous regression of MCC.

There is much speculation regarding the initial biopsy of an MCC lesion (or other traumatic event) and its role in tumor regression. Koba et al41 examined the effect of biopsy on CD8-positive lymphocytic infiltration of MCC tumor cells and found that biopsy does not commonly alter intratumoral CD8-positive infiltration. These findings suggest trauma does not directly induce immunologic recognition of this cancer.

Conclusion

We report a case of complete spontaneous regression of a localized MCC following a punch biopsy. The histopathology showed a brisk T-lymphocyte response with intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells. The age and clinical profile of our patient as well as the clinicopathologic characteristics of the tumor regression are similar to other reported cases. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of MCC regression, and a better understanding of this fascinating phenomenon could help in development of new immunotherapeutic approaches.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, rapidly growing, aggressive neoplasm with a generally poor prognosis. The cells of origin are highly anaplastic and share structural and immunohistochemical features with various neuroectodermally derived cells. Although Merkel cells, which are slow-acting cutaneous mechanoreceptors located in the basal layer of the epidermis, and MCC share immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features, there is limited evidence of a direct histogenetic relationship between the two.1,2 Additionally, some extracutaneous neuroendocrine tumors have features similar to MCC; therefore, although it may be more accurate and perhaps more practical to describe these lesions as primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin, the term MCC is more commonly used both in the literature and in clinical practice.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma typically presents in the head and neck region in white patients older than 70 years of age and in the immunocompromised population.3-6 The mean age of diagnosis is 76 years for women and 74 years for men.7 The incidence of MCC in the United States tripled over a 15-year period, and there are approximately 1500 new cases of MCC diagnosed each year, making it about 40 times less common than melanoma.8 The 5-year survival rate for patients without lymph node involvement is 75%, whereas the 5-year survival rate for patients with distant metastases is 25%.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is thought to develop through 1 of 2 distinct pathways. In a virally mediated pathway, which represents at least 80% of cases, the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV) monoclonally integrates into the host genome and promotes oncogenesis via altered p53 and retinoblastoma protein expression.10-12 The remainder of cases are believed to develop via a nonvirally mediated pathway in which genetic anomalies, immune status, and environmental factors influence oncogenesis.10-13

Due to the similarity between MCC and metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, especially small-cell lung carcinomas, immunohistochemistry is important in making the diagnosis. Cytokeratin 20 and neuron-specific enolase positivity and thyroid transcription factor 1 negativity are the most useful markers in identifying MCC.

Regression of MCC is a very rare and poorly understood event. A 2010 review of the literature described 22 cases of spontaneous regression.14 We report a rare case of rapid and complete regression of MCC following punch biopsy in a 96-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained at a follow-up visit 4 weeks later (12 weeks after the reported onset of the lesion). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed a small-cell neoplasm with stippled nuclei and scant cytoplasm forming a nested and somewhat trabecular pattern. Mitotic activity, apoptosis, and nuclear molding also were present (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 20 with a dotlike, paranuclear pattern (Figure 3). Staining for CAM 5.2 also was positive. Cytokeratin 5/6, human melanoma black 45, and leukocyte common antigen were negative. The immunophenotyping of the lymphocytic response to the tumor showed that the majority of intratumoral lymphocytes were CD8 positive (Figure 4). CD4-positive lymphocytes were predominantly seen at the periphery of the tumor nests without tumor infiltration (Figure 5). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of MCC was made. The patient’s family declined treatment based on her advanced age and current health status, which included advanced dementia.

Two weeks after the punch biopsy, the lesion had noticeably decreased in size and lost its dome-shaped appearance. Within 8 weeks after biopsy (20 weeks since the lesion first appeared), the lesion had completely resolved (Figure 6). The patient was lost to follow-up months later, but no recurrence of the lesion was reported.

Comment

Spontaneous regression is not unique to MCC, as this phenomenon also has been reported in keratoacanthoma, lymphoma, basal cell carcinoma, and melanoma.15 Complete spontaneous regression is defined as occurring in the absence of therapy that is intended to have a treatment effect.15,16 Spontaneous regression is estimated to occur in malignant neoplasms at a rate of 1 case per 60,000 to 100,000 (approximately 0.0013% of all malignant neoplasms).17 Considering the reported prevalence of MCC and the number of cases that have been known to regress, the estimated incidence of complete spontaneous regression may be as high as 1.5%.14 Though spontaneous regression of MCC is more prevalent than expected, it still is considered a rare phenomenon. A 2010 review of the literature yielded 22 cases of complete spontaneous regression of MCC.14 No recurrences have been observed; however, follow-up was relatively short in some cases.

In a unique report by Bertolotti et al,18 a patient with MCC on the nasal tip presented 4 weeks after biopsy with complete spontaneous regression of the tumor, which was associated with bilateral cervical lymph node involvement as noted by hypermetabolic uptake on positron emission tomography scanning. The patient underwent radiation therapy and was disease free at 12 months’ follow-up.18

Complete spontaneous regression has been described in MCC patients with local disease, regional recurrences, and metastatic disease.19 In

The histopathologic features observed in our case, specifically intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells, were similar to the findings in other reported cases. In one series of 2 cases, the one case showed scar tissue with a moderate, predominantly T-lymphocytic infiltrate and no tumor cells, and the second showed cellular proliferation in the deep dermis with dense lymphocytic infiltrates primarily composed of CD3-positive T cells.14 Other studies of regression of both localized and metastatic MCC demonstrated infiltration by CD4-positive, CD8-positive, and CD3-positive lymphocytes and foamy macrophages.21-23

The discovery of the MCV was one of the most important advances in elucidating the pathogenesis of MCC.10,24-26 Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA has been detected in a majority of MCC cases.25,27 Viral integration has been shown to take place early, prior to tumor clonal expansion.10 Importantly, not all cases of MCC show MCV infection, and MCV infection is not exclusive to MCC.28 Merkel cell polyomavirus is considered to be part of the normal human flora, and asymptomatic infection is quite common.29 It has been identified in 80% of adults older than 50 years of age and, interestingly, in 35% of children by 13 years of age or younger.30,31 It remains unclear what role the presence of MCV plays in determining MCC prognosis. Several reports have demonstrated lower disease-specific mortality associated with MCV-positive MCC.32-35 In contrast, Schrama et al36 correlated the MCV status of 174 MCC tumors and found no difference in clinical behavior or prognosis between MCV-positive and MCV-negative MCCs.

Immunosuppression also may play a role in the development of MCC.5,25 There is increased prevalence of MCC in the human immunodeficiency virus–positive population, as well as in organ-transplant recipients and patients with leukemia. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia seems to be the most frequent neoplasia associated with development of MCC.37

The mechanism of MCC regression remains unclear, but many investigators emphasize the importance of T-cell–mediated immunity.16,21-23,38,39 Apoptosis also has been shown to play an important role.40 Our case showed tumor-infiltrating CD8-positive lymphocytes and CD4-positive lymphocytes present predominantly at the periphery of the tumor, with close proximity to the tumor nests but with no tumor infiltration (Figure 3). This distribution was consistently present in multiple sections of the tumor. These findings are consistent with prior reports of both CD4-positive and CD8-positive T lymphocytes associated with MCC regression. Our findings confirm that immune response may play an important role in spontaneous regression of MCC.

There is much speculation regarding the initial biopsy of an MCC lesion (or other traumatic event) and its role in tumor regression. Koba et al41 examined the effect of biopsy on CD8-positive lymphocytic infiltration of MCC tumor cells and found that biopsy does not commonly alter intratumoral CD8-positive infiltration. These findings suggest trauma does not directly induce immunologic recognition of this cancer.

Conclusion

We report a case of complete spontaneous regression of a localized MCC following a punch biopsy. The histopathology showed a brisk T-lymphocyte response with intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells. The age and clinical profile of our patient as well as the clinicopathologic characteristics of the tumor regression are similar to other reported cases. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of MCC regression, and a better understanding of this fascinating phenomenon could help in development of new immunotherapeutic approaches.

- Sibley RK, Dehner LP, Rosai J. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin. I. a clinicopathologic and ultrastructural study of 43 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:95-108.

- Sibley RK, Dahl D. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin. II. an immunocytochemical study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:109-116.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

- Gooptu C, Woolloons A, Ross J, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma arising after therapeutic immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:637-641.

- Plunkett TA, Harris AJ, Ogg CS, et al. The treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma and its association with immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:345-346.

- Calder KB, Smoller BR. New insights into Merkel cell carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:155-161.

- Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

- Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100.

- Amber K, McLeod MP, Nouri K. The Merkel cell polyomavirus and its involvement in Merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:232-238.

- Decaprio JA. Does detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma provide prognostic information? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:905-907.

- Popp S, Waltering S, Herbst C, et al. UV-B-type mutations and chromosomal imbalances indicate common pathways for the development of Merkel and skin squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:352-360.

- Ciudad C, Avilés JA, Alfageme F, et al. Spontaneous regression in Merkel cell carcinoma: report of two cases with description of dermoscopic features and review of literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:687-693.

- O’Rourke MGE, Bell JR. Merkel cell tumor with spontaneous regression. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986;12:994-997.

- Connelly TJ, Cribier B, Brown TJ, et al. Complete spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a review of 10 reported cases. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:853-856.

- Cole WH. Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:201-209.

- Bertolotti A, Conte H, Francois L, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: complete clinical remission associated with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:501-502.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature [published online November 13, 2014]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- Richetta AG, Mancini M, Torroni A, et al. Total spontaneous regression of advanced Merkel cell carcinoma after biopsy: review and a new case. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:815-822.

- Vesely MJ, Murray DJ, Neligan PC, et al. Complete spontaneous regression in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:165-171.

- Kayashima K, Ono T, Johno M, et al. Spontaneous regression in Merkel cell (neuroendocrine) carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:550-553.

- Maruo K, Kayashima KI, Ono T. Regressing Merkel cell carcinoma-a case showing replacement of tumour cells by foamy cells. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1184-1189.

- Duncavage E, Zehnbauer B, Pfeifer J. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:516-521.

- Kassem A, Schopflin A, Diaz C, et al. Frequent detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinomas and identification of unique deletion in the VP1 gene. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5009-5013.

- Becker J, Schrama D, Houben R. Merkel cell carcinoma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1-8.

- Haitz KA, Rady PL, Nguyen HP, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA detection in a patient with Merkel cell carcinoma and multiple other skin cancers. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:442-444.

- Andres C, Puchta U, Sander CA, et al. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA in cutaneous lymphomas, pseudolymphomas, and inflammatory skin diseases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:593-598.

- Showalter RM, Pastrana DV, Pumphrey KA, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and two previously unknown polyomaviruses are chronically shed from human skin. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:509-515.

- Tolstov YL, Pastrana DV, Feng H, et al. Human Merkel cell polyomavirus infection II. MCV is a common human infection that can be detected by conformational capsid epitope immunoassays. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1250-1256.

- Chen T, Hedman L, Mattila PS, et al. Serological evidence of Merkel cell polyomavirus primary infections in childhood. J Clin Virol. 2011;50:125-129.

- Laude HC, Jonchère B, Maubec E, et al. Distinct Merkel cell polyomavirus molecular features in tumour and non tumour specimens from patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001076.

- Waltari M, Sihto H, Kukko H, et al. Association of Merkel cell polyomavirus infection with tumor p53, KIT, stem cell factor, PDGFR-alpha and survival in Merkel cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:619-628.

- Sihto H, Kukko H, Koljonen V, et al. Clinical factors associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:938-945.

- Paulson KG, Lemos BD, Feng B, et al. Array-CGH reveals recurrent genomic changes in Merkel cell carcinoma including amplification of L-Myc. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1547-1555.

- Schrama D, Peitsch WK, Zapatka M, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus status is not associated with clinical course of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1631-1638.