User login

Recurrent Cutaneous Exophiala Phaeohyphomycosis in an Immunosuppressed Patient

To the Editor:

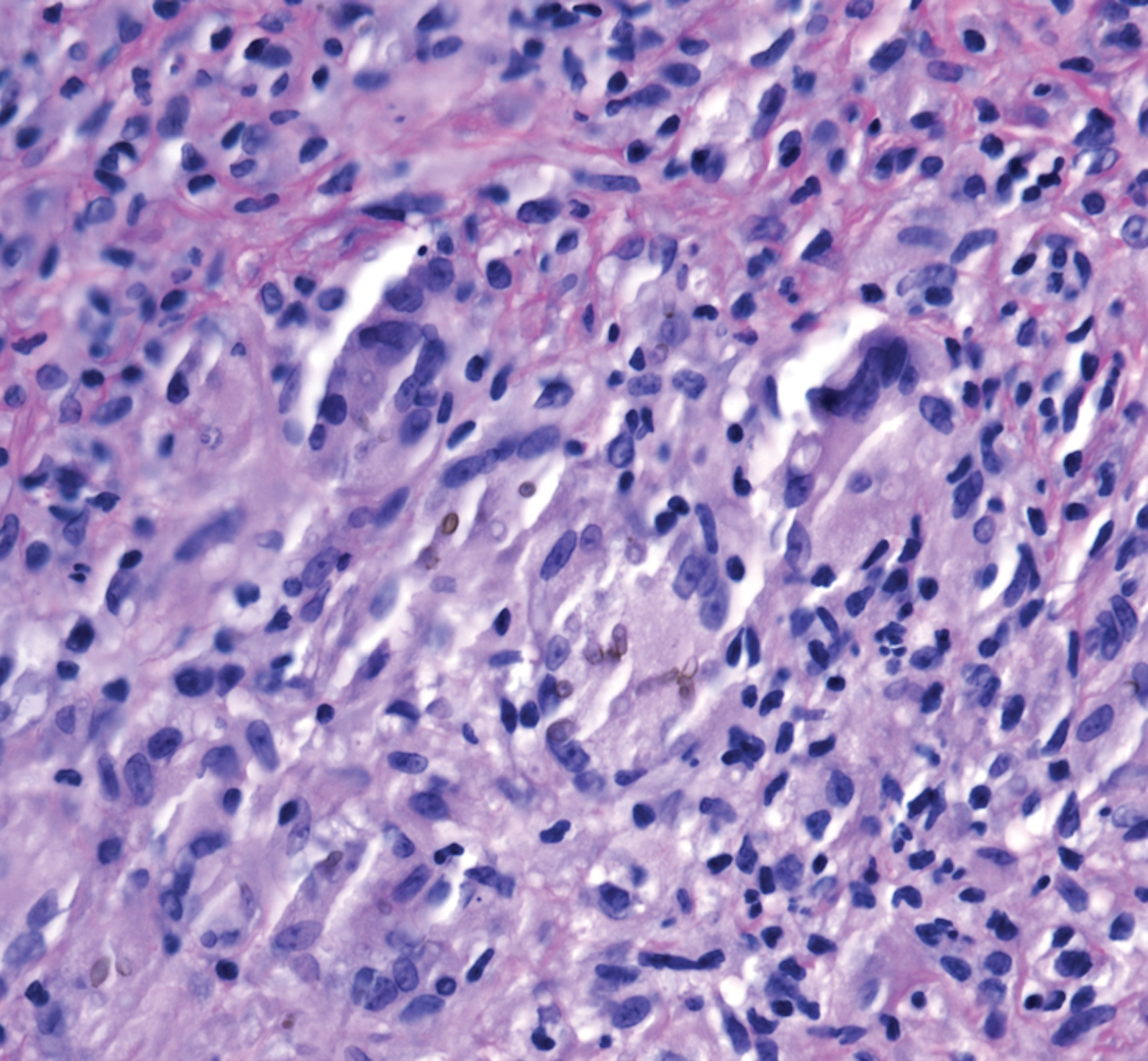

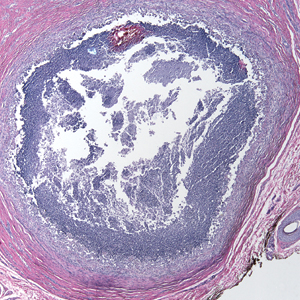

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

Practice Points

- Phaeohyphomycosis is an infection with dematiaceous fungi that most commonly affects immunosuppressed patients.

- Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis may present with nodulocystic lesions that recur over the course of years.

- Tissue fungal culture should be obtained when the diagnosis is suspected, as the risk for dissemination is related to the culprit organism.

- Surgical excision with close follow-up may be an appropriate management strategy for patients on immunosuppressive medications to avoid interactions with azole therapy.

Pronounced racial differences in HBsAg loss after stopping nucleos(t)ide

Loss of the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), a marker for functional cure of hepatitis B infection, is nearly six times more common among White patients than Asian patients following cessation of therapy with a nucleotide or nucleoside analogue, investigators in the RETRACT-B study group report.

Among 1,541 patients in a global retrospective cohort, the cumulative rate of HBsAg loss 4 years after cessation of therapy with entecavir (ETV), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), or other nucleoside/nucleotide analogue (“nuc” or NA) was 11% in Asian patients, compared with 41% in Whites, which translated in multivariate analysis into a hazard ratio (HR) of 5.8 (P < .001), said Grishma Hirode, a clinical research associate and PhD candidate at the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease.

“On univariate Cox regression, the rate of S [antigen] loss was significantly higher among older patients, among [Whites], and among tenofovir-treated patients prior to stopping,” she said during the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Although NAs are effective at suppressing hepatitis B viral activity, functional cure as indicated by HBsAg loss is uncommon, Ms. Hirode noted.

“Finite use of antiviral therapy has been proposed as an alternative to long-term therapy, and the rationale for stopping nuc therapy is to induce a durable virologic remission in the form of an inactive carrier state, and ideally a functional cure,” she said.

The RETRACT-B (Response after End of Treatment with Antivirals in Chronic Hepatitis B) study group, comprising liver treatment centers in Canada, Europe, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, studies outcomes following cessation of nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy.

The investigators looked at data on 1,541 patients, including those with both hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) positive and HBeAg-negative disease at the start of therapy, all of whom were HBeAg negative at the time of antiviral cessation and had undetectable serum HBV DNA. Patients with hepatitis C, hepatitis D and/or HIV co-infection were excluded, as were patients who had received interferon treatment less than 12 months before stopping.

The mean age at baseline was 53 years. Men comprised 73% of the sample. In all, 88% of patients were Asian, 10% White, and 2% other.

In patients for whom genotype data was known, 0.5% had type A, 43% type B, 11% type C, and 2% type D.

Nearly two-thirds of patients (60%) were on ETV at the time of drug cessation, 29% were on TDF, and 11% were on other agents.

In all, 5% of patients had cirrhosis at the time of nucleos(t)ide cessation, the mean HBsAg was 2.6 log10 IU/mL, and the mean alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level was 0.6 times the upper limit of normal.

The median duration of NA therapy was 3 years.

The cumulative rates of HBsAg loss over time among all patients was 3% at 1 year, 8% at 2 years. 12% at 3 years, and 14% at 4 years. Cumulative rates of antigen loss at year 4 were significantly greater for patients 50 and older vs. those younger than 50 (18% vs. 9%, respectively, P = .01), Whites vs. Asians (41% vs. 11%, P < .001), and in those who had been on TDF vs. ETV (17% vs. 12%, P = .001). There was no significant difference in cumulative HBsAg loss between patients who were HBeAg positive or negative at the start of NA therapy.

Cumulative rates of retreatment were 30% at 1 year, 43% at 2 years, 50% at 3 years, and 56% at 4 years. The only significant predictor for retreatment was age, with patients 50 and older being significantly more likely to be retreated by year 4 (63% vs. 45%, respectively, P < .001).

In a univariate model for HBsAg loss, the HR for age 50 and older was 1.7 (P = .01), the HR for White vs. Asian patients was 5.5 (P < .001), and the HR for TDF vs. ETV was 2.0 (P = .001).

A univariate model for retreatment showed an HR of 1.6 for patients 50 and older; all other parameters (sex, race, NA type, and HBeAg status at start of therapy) were not significantly different.

In multivariate models, only race/ethnicity remained significant as a predictor for HBsAg loss, with a HR of 5.8 for Whites vs. Asians (P < .001), and only age 50 and older remained significant as a predictor for retreatment, with a HR of 1.6 (P < .001).

The 4-year cumulative rate of virologic relapse, defined as an HBV DNA of 2000 IU/mL or higher) was 74%, the rate of combined DNA plus ALT relapse (ALT 2 or more times the upper limit of normal) was 56%, and the rate of ALT flares (5 or more times the upper limit of normal) was 33%.

In all, 15 patients (1%) experienced hepatic decompensation, and 12 (0.96%) died, with 9 of the deaths reported as liver-related.

Race/ethnicity differences previously seen

Liver specialist Anna Suk-Fong Lok, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the study, said that the findings are not especially surprising.

“When the studies came out from Asian countries showing that patients who were taken off treatment had a higher rate of S antigen loss than patients who stayed on treatment, the rate of S antigen loss was not all that impressive, but when you look at the European studies the rate of S antigen loss was very high,” she said in an interview.

“The question of course is ‘Why?’ I don’t think we understand completely why. We can speculate, but none of these type studies give us a definitive answer,” she said.

Possible reasons for the racial differences in HBsAg loss include differences in hepatitis B genotype, she said.

“Another possibility is that Asian patients may have been infected either at the time of birth or as a young kid, so they may have been infected for a much longer period of time than [Whites], who usually acquire infections as adults,” Dr. Lok said.

There may also be differences between patient populations in immune responses following cessation of antiviral therapy, she added.

The study was supported by the RETRACT-B group. Ms. Hirode and Dr. Lok reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Hirode G et al. AASLD 2020. Abstract 23.

Loss of the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), a marker for functional cure of hepatitis B infection, is nearly six times more common among White patients than Asian patients following cessation of therapy with a nucleotide or nucleoside analogue, investigators in the RETRACT-B study group report.

Among 1,541 patients in a global retrospective cohort, the cumulative rate of HBsAg loss 4 years after cessation of therapy with entecavir (ETV), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), or other nucleoside/nucleotide analogue (“nuc” or NA) was 11% in Asian patients, compared with 41% in Whites, which translated in multivariate analysis into a hazard ratio (HR) of 5.8 (P < .001), said Grishma Hirode, a clinical research associate and PhD candidate at the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease.

“On univariate Cox regression, the rate of S [antigen] loss was significantly higher among older patients, among [Whites], and among tenofovir-treated patients prior to stopping,” she said during the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Although NAs are effective at suppressing hepatitis B viral activity, functional cure as indicated by HBsAg loss is uncommon, Ms. Hirode noted.

“Finite use of antiviral therapy has been proposed as an alternative to long-term therapy, and the rationale for stopping nuc therapy is to induce a durable virologic remission in the form of an inactive carrier state, and ideally a functional cure,” she said.

The RETRACT-B (Response after End of Treatment with Antivirals in Chronic Hepatitis B) study group, comprising liver treatment centers in Canada, Europe, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, studies outcomes following cessation of nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy.

The investigators looked at data on 1,541 patients, including those with both hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) positive and HBeAg-negative disease at the start of therapy, all of whom were HBeAg negative at the time of antiviral cessation and had undetectable serum HBV DNA. Patients with hepatitis C, hepatitis D and/or HIV co-infection were excluded, as were patients who had received interferon treatment less than 12 months before stopping.

The mean age at baseline was 53 years. Men comprised 73% of the sample. In all, 88% of patients were Asian, 10% White, and 2% other.

In patients for whom genotype data was known, 0.5% had type A, 43% type B, 11% type C, and 2% type D.

Nearly two-thirds of patients (60%) were on ETV at the time of drug cessation, 29% were on TDF, and 11% were on other agents.

In all, 5% of patients had cirrhosis at the time of nucleos(t)ide cessation, the mean HBsAg was 2.6 log10 IU/mL, and the mean alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level was 0.6 times the upper limit of normal.

The median duration of NA therapy was 3 years.

The cumulative rates of HBsAg loss over time among all patients was 3% at 1 year, 8% at 2 years. 12% at 3 years, and 14% at 4 years. Cumulative rates of antigen loss at year 4 were significantly greater for patients 50 and older vs. those younger than 50 (18% vs. 9%, respectively, P = .01), Whites vs. Asians (41% vs. 11%, P < .001), and in those who had been on TDF vs. ETV (17% vs. 12%, P = .001). There was no significant difference in cumulative HBsAg loss between patients who were HBeAg positive or negative at the start of NA therapy.

Cumulative rates of retreatment were 30% at 1 year, 43% at 2 years, 50% at 3 years, and 56% at 4 years. The only significant predictor for retreatment was age, with patients 50 and older being significantly more likely to be retreated by year 4 (63% vs. 45%, respectively, P < .001).

In a univariate model for HBsAg loss, the HR for age 50 and older was 1.7 (P = .01), the HR for White vs. Asian patients was 5.5 (P < .001), and the HR for TDF vs. ETV was 2.0 (P = .001).

A univariate model for retreatment showed an HR of 1.6 for patients 50 and older; all other parameters (sex, race, NA type, and HBeAg status at start of therapy) were not significantly different.

In multivariate models, only race/ethnicity remained significant as a predictor for HBsAg loss, with a HR of 5.8 for Whites vs. Asians (P < .001), and only age 50 and older remained significant as a predictor for retreatment, with a HR of 1.6 (P < .001).

The 4-year cumulative rate of virologic relapse, defined as an HBV DNA of 2000 IU/mL or higher) was 74%, the rate of combined DNA plus ALT relapse (ALT 2 or more times the upper limit of normal) was 56%, and the rate of ALT flares (5 or more times the upper limit of normal) was 33%.

In all, 15 patients (1%) experienced hepatic decompensation, and 12 (0.96%) died, with 9 of the deaths reported as liver-related.

Race/ethnicity differences previously seen

Liver specialist Anna Suk-Fong Lok, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the study, said that the findings are not especially surprising.

“When the studies came out from Asian countries showing that patients who were taken off treatment had a higher rate of S antigen loss than patients who stayed on treatment, the rate of S antigen loss was not all that impressive, but when you look at the European studies the rate of S antigen loss was very high,” she said in an interview.

“The question of course is ‘Why?’ I don’t think we understand completely why. We can speculate, but none of these type studies give us a definitive answer,” she said.

Possible reasons for the racial differences in HBsAg loss include differences in hepatitis B genotype, she said.

“Another possibility is that Asian patients may have been infected either at the time of birth or as a young kid, so they may have been infected for a much longer period of time than [Whites], who usually acquire infections as adults,” Dr. Lok said.

There may also be differences between patient populations in immune responses following cessation of antiviral therapy, she added.

The study was supported by the RETRACT-B group. Ms. Hirode and Dr. Lok reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Hirode G et al. AASLD 2020. Abstract 23.

Loss of the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), a marker for functional cure of hepatitis B infection, is nearly six times more common among White patients than Asian patients following cessation of therapy with a nucleotide or nucleoside analogue, investigators in the RETRACT-B study group report.

Among 1,541 patients in a global retrospective cohort, the cumulative rate of HBsAg loss 4 years after cessation of therapy with entecavir (ETV), tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), or other nucleoside/nucleotide analogue (“nuc” or NA) was 11% in Asian patients, compared with 41% in Whites, which translated in multivariate analysis into a hazard ratio (HR) of 5.8 (P < .001), said Grishma Hirode, a clinical research associate and PhD candidate at the Toronto Centre for Liver Disease.

“On univariate Cox regression, the rate of S [antigen] loss was significantly higher among older patients, among [Whites], and among tenofovir-treated patients prior to stopping,” she said during the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Although NAs are effective at suppressing hepatitis B viral activity, functional cure as indicated by HBsAg loss is uncommon, Ms. Hirode noted.

“Finite use of antiviral therapy has been proposed as an alternative to long-term therapy, and the rationale for stopping nuc therapy is to induce a durable virologic remission in the form of an inactive carrier state, and ideally a functional cure,” she said.

The RETRACT-B (Response after End of Treatment with Antivirals in Chronic Hepatitis B) study group, comprising liver treatment centers in Canada, Europe, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, studies outcomes following cessation of nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy.

The investigators looked at data on 1,541 patients, including those with both hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) positive and HBeAg-negative disease at the start of therapy, all of whom were HBeAg negative at the time of antiviral cessation and had undetectable serum HBV DNA. Patients with hepatitis C, hepatitis D and/or HIV co-infection were excluded, as were patients who had received interferon treatment less than 12 months before stopping.

The mean age at baseline was 53 years. Men comprised 73% of the sample. In all, 88% of patients were Asian, 10% White, and 2% other.

In patients for whom genotype data was known, 0.5% had type A, 43% type B, 11% type C, and 2% type D.

Nearly two-thirds of patients (60%) were on ETV at the time of drug cessation, 29% were on TDF, and 11% were on other agents.

In all, 5% of patients had cirrhosis at the time of nucleos(t)ide cessation, the mean HBsAg was 2.6 log10 IU/mL, and the mean alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level was 0.6 times the upper limit of normal.

The median duration of NA therapy was 3 years.

The cumulative rates of HBsAg loss over time among all patients was 3% at 1 year, 8% at 2 years. 12% at 3 years, and 14% at 4 years. Cumulative rates of antigen loss at year 4 were significantly greater for patients 50 and older vs. those younger than 50 (18% vs. 9%, respectively, P = .01), Whites vs. Asians (41% vs. 11%, P < .001), and in those who had been on TDF vs. ETV (17% vs. 12%, P = .001). There was no significant difference in cumulative HBsAg loss between patients who were HBeAg positive or negative at the start of NA therapy.

Cumulative rates of retreatment were 30% at 1 year, 43% at 2 years, 50% at 3 years, and 56% at 4 years. The only significant predictor for retreatment was age, with patients 50 and older being significantly more likely to be retreated by year 4 (63% vs. 45%, respectively, P < .001).

In a univariate model for HBsAg loss, the HR for age 50 and older was 1.7 (P = .01), the HR for White vs. Asian patients was 5.5 (P < .001), and the HR for TDF vs. ETV was 2.0 (P = .001).

A univariate model for retreatment showed an HR of 1.6 for patients 50 and older; all other parameters (sex, race, NA type, and HBeAg status at start of therapy) were not significantly different.

In multivariate models, only race/ethnicity remained significant as a predictor for HBsAg loss, with a HR of 5.8 for Whites vs. Asians (P < .001), and only age 50 and older remained significant as a predictor for retreatment, with a HR of 1.6 (P < .001).

The 4-year cumulative rate of virologic relapse, defined as an HBV DNA of 2000 IU/mL or higher) was 74%, the rate of combined DNA plus ALT relapse (ALT 2 or more times the upper limit of normal) was 56%, and the rate of ALT flares (5 or more times the upper limit of normal) was 33%.

In all, 15 patients (1%) experienced hepatic decompensation, and 12 (0.96%) died, with 9 of the deaths reported as liver-related.

Race/ethnicity differences previously seen

Liver specialist Anna Suk-Fong Lok, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the study, said that the findings are not especially surprising.

“When the studies came out from Asian countries showing that patients who were taken off treatment had a higher rate of S antigen loss than patients who stayed on treatment, the rate of S antigen loss was not all that impressive, but when you look at the European studies the rate of S antigen loss was very high,” she said in an interview.

“The question of course is ‘Why?’ I don’t think we understand completely why. We can speculate, but none of these type studies give us a definitive answer,” she said.

Possible reasons for the racial differences in HBsAg loss include differences in hepatitis B genotype, she said.

“Another possibility is that Asian patients may have been infected either at the time of birth or as a young kid, so they may have been infected for a much longer period of time than [Whites], who usually acquire infections as adults,” Dr. Lok said.

There may also be differences between patient populations in immune responses following cessation of antiviral therapy, she added.

The study was supported by the RETRACT-B group. Ms. Hirode and Dr. Lok reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Hirode G et al. AASLD 2020. Abstract 23.

FROM THE LIVER MEETING DIGITAL EXPERIENCE

Vanquishing hepatitis C: A remarkable success story

One of the most remarkable stories in medicine must be the relatively brief 25 years between the discovery of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) in 1989 to its eventual cure in 2014.

HCV afflicted over 5 million Americans and was the cause of death in approximately 10,000 patients annually, the leading indication for liver transplantation, and the leading risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma, clearly signaling it as one of the era’s major public health villains. Within that span of time, it is the work beginning in the mid-1990s until today that perhaps best defines the race for the HCV “cure.”

In the early to mid-1990s, polymerase chain reaction techniques were just becoming commonplace for HCV diagnosis, whereas HCV genotypes were emerging as major factors determining response to interferon therapy. The sustained viral response (SVR) rates were mired at around 6%-12% for a 24- to 48-week course of three-times-weekly injection therapy. Severe side effects were common and there was a relatively high relapse rate, even in patients who responded to treatment.

By 1996, the addition of ribavirin to the interferon treatment was associated with a modest but significant improvement in SVR rates to above 20%. And by 2000, the use of pegylated interferon – allowing once-weekly injection therapy – along with ribavirin, improved SVR rates to above 50% for the first time. The therapy was still poorly tolerated but was associated with better compliance.

The real breakthrough in therapy came in the early 2000s with the discovery and availability of HCV protease inhibitors: telaprevir and boceprevir. These agents could induce a more rapid decline in viral replication than interferon but could not be administered alone owing to the rapid emergence of resistant HCV variants. Therefore, these agents were administered with interferon and ribavirin as a three-drug cocktail to take advantage of interferon to prevent emergence of resistant variants. Although SVR rates improved substantially to around 75%, adverse events also increased and limited its usefulness in patients with more advanced liver disease, precisely those who were most in need of better therapies.

Nonetheless, the incredible advances in understanding the replication machinery of HCV that led to the discovery of the protease inhibitors in turn led to further elucidation and unlocking of three additional classes of HCV protein targets and inhibitors: NS5A complex inhibitors (e.g., ledipasvir), the NS5B nonnucleoside inhibitors (e.g., dasabuvir), and NS5B nucleoside inhibitors (e.g., sofosbuvir). It quickly became apparent that the use of combinations of these direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) could limit emergence of resistant variants while also providing rapid and profound viral suppression. Because HCV required viral replication to persist in the hepatocyte, it became possible to induce HCV eradication, and thus cure, with combinations of DAAs.

In addition, investigators soon learned that the duration of therapy no longer needed to be the generally accepted 24-48 weeks for SVR, but instead could be reduced eventually to 8-12 weeks. This shortened treatment duration allowed for more rapid testing of new agents and combinations, and the field took a rapid step forward between 2011 and 2017. HCV cure rates rose to 90%-95%.

The competition for Food and Drug Administration approval of new agents among several pharmaceutical companies also meant that the time-honored process of issuing treatment guidelines every 3-5 years by societies would not be adequate. Therefore, in 2013, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America joined forces to establish more nimble and responsive online HCV guidance. This important resource debuted in January 2014 just as the FDA approved the first DAA therapies.

The high cost initially associated with many of these new therapies (up to $1,000 per pill) significantly limited uptake owing to insurance and health plan cost factors. Early on, the cost was also analyzed by price per cure, seemingly to justify the high cost by the high cure rate. However, advocacy and negotiations ultimately led to marked reductions in the cost of a course of therapy (with some therapies at $225 per pill), thus making these treatments now widely available.

By 2020, the HCV field has shifted from therapeutic development to improving the care cascade by enhanced identification and testing of unsuspected but HCV infected individuals. This is our current challenge.

Moving toward noninvasive tests

While curative therapy has revolutionized HCV management, innovation in diagnostics eliminated a significant barrier in access to therapy: the liver biopsy.

Staging, or accurately identifying advanced fibrosis in persons infected with HCV, is essential for long-term follow-up. The presence of advanced disease affects drug choices, especially before the approval of all-oral therapy. Historically, a liver biopsy was obligatory before treatment. Invasive with a significant risk for complications, this requirement effectively prevented treatment in those who were unwilling to undergo the procedure and deterred those at risk from even being tested.

Over the past 25 years, numerous methods to noninvasively assess for liver fibrosis have been used. Serum biomarkers can be either indirect (based on routine tests) or direct (reflecting components of the extracellular matrix). Although highly available, they are only moderately useful for identifying advanced fibrosis and thus cannot replace liver biopsy in the care cascade. The technique of elastography dates back to the 1980s, though the role of vibration-controlled transient liver elastography in the assessment of hepatic fibrosis in patients with HCV was not recognized until around 2005 and it was not commonly used for nearly another decade.

Yet, a paradigm shift in the care cascade occurred with the release of the AASLD/IDSA guidance document in 2014. For the first time in the United States, noninvasive tests were recommended as first-line testing for the assessment of advanced fibrosis. Prior guidelines specifically stated that although noninvasive tests might be useful, they “should not replace the liver biopsy in routine clinical practice.” Current guidelines recommend combining elastography with serum biomarkers and considering biopsy only in patients with discordant results if the biopsy would affect clinical decision-making.

The last frontier

Curative therapy has also allowed the unthinkable: willingly exposing patients to the virus through donor-positive/recipient-negative solid organ transplant. Traditionally, an HCV-infected donor would be considered only for an HCV-positive recipient; however, with effective DAA therapy, the number of HCV actively infected patients in need of transplant has dwindled.

Unfortunately as a consequence of the opioid epidemic, the HCV-exposed donor population has blossomed. Given that HCV therapy is near universally curative, using organs from HCV-viremic donors can greatly expand the organ transplantation pool. Small studies[1-5] have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of this approach, both in HCV-positive liver donors as well as in other solid organs.

A disease pegged for elimination

In the past 25 years, HCV has evolved from non-A, non-B hepatitis into a disease pegged for elimination. This is a direct reflection of improved therapeutics with highly effective DAAs. Yet, without improved diagnostics, we would be unable to navigate patients through the clinical care cascade. These incredible strides in diagnostics and therapeutics allow us to push the cutting edge through iatrogenic infection of organ recipients, while recognizing that the largest hurdle to elimination remains in finding those who are chronically infected. Ultimately, the crux of elimination remains unchanged over the past 25 years and resides in screening and diagnosis with effective linkage to care.

Donald M. Jensen, MD, is a professor of medicine at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. He was previously the director of the Center for Liver Disease at the University of Chicago until 2015. His research interest has been in newer HCV therapies. He recently received the Distinguished Service Award from the AASLD for his many contributions to the field.

Nancy S. Reau, MD, is chief of the hepatology section at Rush University Medical Center and a regular contributor to Medscape. She serves as editor of Clinical Liver Disease, a multimedia review journal, and recently as a member of HCVGuidelines.org, a web-based resource from the AASLD and the IDSA, as well as educational chair for the AASLD hepatitis C special interest group. She continues to have an active role in the hepatology interest group of the World Gastroenterology Organisation and the American Liver Foundation at the regional and national levels.

References

Woolley AE et al. Heart and lung transplants from HCV-infected donors to uninfected recipients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1606-17.

Franco A et al. Renal transplantation from seropositive hepatitis C virus donors to seronegative recipients in Spain: A prospective study. Transpl Int. 2019;32:710-6.

Goldberg DS et al. Transplanting HCV-infected kidneys into uninfected recipients. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1105.

Kwong AJ et al. Liver transplantation for hepatitis C virus (HCV) nonviremic recipients with HCV viremic donors. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:1380-7.

Bethea E et al. Immediate administration of antiviral therapy after transplantation of hepatitis C–infected livers into uninfected recipients: Implications for therapeutic planning. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1619-28.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the most remarkable stories in medicine must be the relatively brief 25 years between the discovery of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) in 1989 to its eventual cure in 2014.

HCV afflicted over 5 million Americans and was the cause of death in approximately 10,000 patients annually, the leading indication for liver transplantation, and the leading risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma, clearly signaling it as one of the era’s major public health villains. Within that span of time, it is the work beginning in the mid-1990s until today that perhaps best defines the race for the HCV “cure.”

In the early to mid-1990s, polymerase chain reaction techniques were just becoming commonplace for HCV diagnosis, whereas HCV genotypes were emerging as major factors determining response to interferon therapy. The sustained viral response (SVR) rates were mired at around 6%-12% for a 24- to 48-week course of three-times-weekly injection therapy. Severe side effects were common and there was a relatively high relapse rate, even in patients who responded to treatment.

By 1996, the addition of ribavirin to the interferon treatment was associated with a modest but significant improvement in SVR rates to above 20%. And by 2000, the use of pegylated interferon – allowing once-weekly injection therapy – along with ribavirin, improved SVR rates to above 50% for the first time. The therapy was still poorly tolerated but was associated with better compliance.

The real breakthrough in therapy came in the early 2000s with the discovery and availability of HCV protease inhibitors: telaprevir and boceprevir. These agents could induce a more rapid decline in viral replication than interferon but could not be administered alone owing to the rapid emergence of resistant HCV variants. Therefore, these agents were administered with interferon and ribavirin as a three-drug cocktail to take advantage of interferon to prevent emergence of resistant variants. Although SVR rates improved substantially to around 75%, adverse events also increased and limited its usefulness in patients with more advanced liver disease, precisely those who were most in need of better therapies.

Nonetheless, the incredible advances in understanding the replication machinery of HCV that led to the discovery of the protease inhibitors in turn led to further elucidation and unlocking of three additional classes of HCV protein targets and inhibitors: NS5A complex inhibitors (e.g., ledipasvir), the NS5B nonnucleoside inhibitors (e.g., dasabuvir), and NS5B nucleoside inhibitors (e.g., sofosbuvir). It quickly became apparent that the use of combinations of these direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) could limit emergence of resistant variants while also providing rapid and profound viral suppression. Because HCV required viral replication to persist in the hepatocyte, it became possible to induce HCV eradication, and thus cure, with combinations of DAAs.

In addition, investigators soon learned that the duration of therapy no longer needed to be the generally accepted 24-48 weeks for SVR, but instead could be reduced eventually to 8-12 weeks. This shortened treatment duration allowed for more rapid testing of new agents and combinations, and the field took a rapid step forward between 2011 and 2017. HCV cure rates rose to 90%-95%.

The competition for Food and Drug Administration approval of new agents among several pharmaceutical companies also meant that the time-honored process of issuing treatment guidelines every 3-5 years by societies would not be adequate. Therefore, in 2013, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America joined forces to establish more nimble and responsive online HCV guidance. This important resource debuted in January 2014 just as the FDA approved the first DAA therapies.

The high cost initially associated with many of these new therapies (up to $1,000 per pill) significantly limited uptake owing to insurance and health plan cost factors. Early on, the cost was also analyzed by price per cure, seemingly to justify the high cost by the high cure rate. However, advocacy and negotiations ultimately led to marked reductions in the cost of a course of therapy (with some therapies at $225 per pill), thus making these treatments now widely available.

By 2020, the HCV field has shifted from therapeutic development to improving the care cascade by enhanced identification and testing of unsuspected but HCV infected individuals. This is our current challenge.

Moving toward noninvasive tests

While curative therapy has revolutionized HCV management, innovation in diagnostics eliminated a significant barrier in access to therapy: the liver biopsy.

Staging, or accurately identifying advanced fibrosis in persons infected with HCV, is essential for long-term follow-up. The presence of advanced disease affects drug choices, especially before the approval of all-oral therapy. Historically, a liver biopsy was obligatory before treatment. Invasive with a significant risk for complications, this requirement effectively prevented treatment in those who were unwilling to undergo the procedure and deterred those at risk from even being tested.

Over the past 25 years, numerous methods to noninvasively assess for liver fibrosis have been used. Serum biomarkers can be either indirect (based on routine tests) or direct (reflecting components of the extracellular matrix). Although highly available, they are only moderately useful for identifying advanced fibrosis and thus cannot replace liver biopsy in the care cascade. The technique of elastography dates back to the 1980s, though the role of vibration-controlled transient liver elastography in the assessment of hepatic fibrosis in patients with HCV was not recognized until around 2005 and it was not commonly used for nearly another decade.

Yet, a paradigm shift in the care cascade occurred with the release of the AASLD/IDSA guidance document in 2014. For the first time in the United States, noninvasive tests were recommended as first-line testing for the assessment of advanced fibrosis. Prior guidelines specifically stated that although noninvasive tests might be useful, they “should not replace the liver biopsy in routine clinical practice.” Current guidelines recommend combining elastography with serum biomarkers and considering biopsy only in patients with discordant results if the biopsy would affect clinical decision-making.

The last frontier

Curative therapy has also allowed the unthinkable: willingly exposing patients to the virus through donor-positive/recipient-negative solid organ transplant. Traditionally, an HCV-infected donor would be considered only for an HCV-positive recipient; however, with effective DAA therapy, the number of HCV actively infected patients in need of transplant has dwindled.

Unfortunately as a consequence of the opioid epidemic, the HCV-exposed donor population has blossomed. Given that HCV therapy is near universally curative, using organs from HCV-viremic donors can greatly expand the organ transplantation pool. Small studies[1-5] have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of this approach, both in HCV-positive liver donors as well as in other solid organs.

A disease pegged for elimination

In the past 25 years, HCV has evolved from non-A, non-B hepatitis into a disease pegged for elimination. This is a direct reflection of improved therapeutics with highly effective DAAs. Yet, without improved diagnostics, we would be unable to navigate patients through the clinical care cascade. These incredible strides in diagnostics and therapeutics allow us to push the cutting edge through iatrogenic infection of organ recipients, while recognizing that the largest hurdle to elimination remains in finding those who are chronically infected. Ultimately, the crux of elimination remains unchanged over the past 25 years and resides in screening and diagnosis with effective linkage to care.

Donald M. Jensen, MD, is a professor of medicine at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. He was previously the director of the Center for Liver Disease at the University of Chicago until 2015. His research interest has been in newer HCV therapies. He recently received the Distinguished Service Award from the AASLD for his many contributions to the field.

Nancy S. Reau, MD, is chief of the hepatology section at Rush University Medical Center and a regular contributor to Medscape. She serves as editor of Clinical Liver Disease, a multimedia review journal, and recently as a member of HCVGuidelines.org, a web-based resource from the AASLD and the IDSA, as well as educational chair for the AASLD hepatitis C special interest group. She continues to have an active role in the hepatology interest group of the World Gastroenterology Organisation and the American Liver Foundation at the regional and national levels.

References

Woolley AE et al. Heart and lung transplants from HCV-infected donors to uninfected recipients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1606-17.

Franco A et al. Renal transplantation from seropositive hepatitis C virus donors to seronegative recipients in Spain: A prospective study. Transpl Int. 2019;32:710-6.

Goldberg DS et al. Transplanting HCV-infected kidneys into uninfected recipients. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1105.

Kwong AJ et al. Liver transplantation for hepatitis C virus (HCV) nonviremic recipients with HCV viremic donors. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:1380-7.

Bethea E et al. Immediate administration of antiviral therapy after transplantation of hepatitis C–infected livers into uninfected recipients: Implications for therapeutic planning. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1619-28.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

One of the most remarkable stories in medicine must be the relatively brief 25 years between the discovery of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) in 1989 to its eventual cure in 2014.

HCV afflicted over 5 million Americans and was the cause of death in approximately 10,000 patients annually, the leading indication for liver transplantation, and the leading risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma, clearly signaling it as one of the era’s major public health villains. Within that span of time, it is the work beginning in the mid-1990s until today that perhaps best defines the race for the HCV “cure.”

In the early to mid-1990s, polymerase chain reaction techniques were just becoming commonplace for HCV diagnosis, whereas HCV genotypes were emerging as major factors determining response to interferon therapy. The sustained viral response (SVR) rates were mired at around 6%-12% for a 24- to 48-week course of three-times-weekly injection therapy. Severe side effects were common and there was a relatively high relapse rate, even in patients who responded to treatment.

By 1996, the addition of ribavirin to the interferon treatment was associated with a modest but significant improvement in SVR rates to above 20%. And by 2000, the use of pegylated interferon – allowing once-weekly injection therapy – along with ribavirin, improved SVR rates to above 50% for the first time. The therapy was still poorly tolerated but was associated with better compliance.

The real breakthrough in therapy came in the early 2000s with the discovery and availability of HCV protease inhibitors: telaprevir and boceprevir. These agents could induce a more rapid decline in viral replication than interferon but could not be administered alone owing to the rapid emergence of resistant HCV variants. Therefore, these agents were administered with interferon and ribavirin as a three-drug cocktail to take advantage of interferon to prevent emergence of resistant variants. Although SVR rates improved substantially to around 75%, adverse events also increased and limited its usefulness in patients with more advanced liver disease, precisely those who were most in need of better therapies.

Nonetheless, the incredible advances in understanding the replication machinery of HCV that led to the discovery of the protease inhibitors in turn led to further elucidation and unlocking of three additional classes of HCV protein targets and inhibitors: NS5A complex inhibitors (e.g., ledipasvir), the NS5B nonnucleoside inhibitors (e.g., dasabuvir), and NS5B nucleoside inhibitors (e.g., sofosbuvir). It quickly became apparent that the use of combinations of these direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) could limit emergence of resistant variants while also providing rapid and profound viral suppression. Because HCV required viral replication to persist in the hepatocyte, it became possible to induce HCV eradication, and thus cure, with combinations of DAAs.

In addition, investigators soon learned that the duration of therapy no longer needed to be the generally accepted 24-48 weeks for SVR, but instead could be reduced eventually to 8-12 weeks. This shortened treatment duration allowed for more rapid testing of new agents and combinations, and the field took a rapid step forward between 2011 and 2017. HCV cure rates rose to 90%-95%.

The competition for Food and Drug Administration approval of new agents among several pharmaceutical companies also meant that the time-honored process of issuing treatment guidelines every 3-5 years by societies would not be adequate. Therefore, in 2013, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America joined forces to establish more nimble and responsive online HCV guidance. This important resource debuted in January 2014 just as the FDA approved the first DAA therapies.

The high cost initially associated with many of these new therapies (up to $1,000 per pill) significantly limited uptake owing to insurance and health plan cost factors. Early on, the cost was also analyzed by price per cure, seemingly to justify the high cost by the high cure rate. However, advocacy and negotiations ultimately led to marked reductions in the cost of a course of therapy (with some therapies at $225 per pill), thus making these treatments now widely available.

By 2020, the HCV field has shifted from therapeutic development to improving the care cascade by enhanced identification and testing of unsuspected but HCV infected individuals. This is our current challenge.

Moving toward noninvasive tests

While curative therapy has revolutionized HCV management, innovation in diagnostics eliminated a significant barrier in access to therapy: the liver biopsy.

Staging, or accurately identifying advanced fibrosis in persons infected with HCV, is essential for long-term follow-up. The presence of advanced disease affects drug choices, especially before the approval of all-oral therapy. Historically, a liver biopsy was obligatory before treatment. Invasive with a significant risk for complications, this requirement effectively prevented treatment in those who were unwilling to undergo the procedure and deterred those at risk from even being tested.

Over the past 25 years, numerous methods to noninvasively assess for liver fibrosis have been used. Serum biomarkers can be either indirect (based on routine tests) or direct (reflecting components of the extracellular matrix). Although highly available, they are only moderately useful for identifying advanced fibrosis and thus cannot replace liver biopsy in the care cascade. The technique of elastography dates back to the 1980s, though the role of vibration-controlled transient liver elastography in the assessment of hepatic fibrosis in patients with HCV was not recognized until around 2005 and it was not commonly used for nearly another decade.

Yet, a paradigm shift in the care cascade occurred with the release of the AASLD/IDSA guidance document in 2014. For the first time in the United States, noninvasive tests were recommended as first-line testing for the assessment of advanced fibrosis. Prior guidelines specifically stated that although noninvasive tests might be useful, they “should not replace the liver biopsy in routine clinical practice.” Current guidelines recommend combining elastography with serum biomarkers and considering biopsy only in patients with discordant results if the biopsy would affect clinical decision-making.

The last frontier

Curative therapy has also allowed the unthinkable: willingly exposing patients to the virus through donor-positive/recipient-negative solid organ transplant. Traditionally, an HCV-infected donor would be considered only for an HCV-positive recipient; however, with effective DAA therapy, the number of HCV actively infected patients in need of transplant has dwindled.

Unfortunately as a consequence of the opioid epidemic, the HCV-exposed donor population has blossomed. Given that HCV therapy is near universally curative, using organs from HCV-viremic donors can greatly expand the organ transplantation pool. Small studies[1-5] have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of this approach, both in HCV-positive liver donors as well as in other solid organs.

A disease pegged for elimination

In the past 25 years, HCV has evolved from non-A, non-B hepatitis into a disease pegged for elimination. This is a direct reflection of improved therapeutics with highly effective DAAs. Yet, without improved diagnostics, we would be unable to navigate patients through the clinical care cascade. These incredible strides in diagnostics and therapeutics allow us to push the cutting edge through iatrogenic infection of organ recipients, while recognizing that the largest hurdle to elimination remains in finding those who are chronically infected. Ultimately, the crux of elimination remains unchanged over the past 25 years and resides in screening and diagnosis with effective linkage to care.

Donald M. Jensen, MD, is a professor of medicine at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. He was previously the director of the Center for Liver Disease at the University of Chicago until 2015. His research interest has been in newer HCV therapies. He recently received the Distinguished Service Award from the AASLD for his many contributions to the field.

Nancy S. Reau, MD, is chief of the hepatology section at Rush University Medical Center and a regular contributor to Medscape. She serves as editor of Clinical Liver Disease, a multimedia review journal, and recently as a member of HCVGuidelines.org, a web-based resource from the AASLD and the IDSA, as well as educational chair for the AASLD hepatitis C special interest group. She continues to have an active role in the hepatology interest group of the World Gastroenterology Organisation and the American Liver Foundation at the regional and national levels.

References

Woolley AE et al. Heart and lung transplants from HCV-infected donors to uninfected recipients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1606-17.

Franco A et al. Renal transplantation from seropositive hepatitis C virus donors to seronegative recipients in Spain: A prospective study. Transpl Int. 2019;32:710-6.

Goldberg DS et al. Transplanting HCV-infected kidneys into uninfected recipients. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1105.

Kwong AJ et al. Liver transplantation for hepatitis C virus (HCV) nonviremic recipients with HCV viremic donors. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:1380-7.

Bethea E et al. Immediate administration of antiviral therapy after transplantation of hepatitis C–infected livers into uninfected recipients: Implications for therapeutic planning. Am J Transplant. 2020;20:1619-28.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Harnessing the HIV care continuum model to improve HCV treatment success

Better linkage to care with providers who are familiar with both the HCV and HIV treatment cascade may not only improve access to HCV treatment, but it may also support patient retention, treatment adherence, and achievement of sustained virologic response (SVR) and viral suppression, said Stephanie LaMoy, CAN Community Health, North Point, Florida. She presented the results of a pilot study at the virtual Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2020 Annual Meeting.

In an effort to identify strategies most important for improving care access among their patients with HCV, LaMoy and her colleagues assessed 12-month patient data collected from three of their clinics. These data were evaluated for HCV treatment access, engagement, and outcomes.

The pilot study included 126 patients who were reactive and another 24 HCV-positive patients who were referred from other sources. Active HCV infections requiring treatment were reported in 144 patients.

A total of 59 patients were linked to care but did not initiate treatment for their active infection. LaMoy said there were multiple causes, including homelessness, substance abuse, and inability to maintain contact.

In contrast, 85 patients with HCV infection started treatment, but 35 of these patients did not complete their regimen. Out of the 50 patients who reported completing treatment, 30 did not return to the clinic to confirm sustained viral suppression.

According to LaMoy, this raised a red flag, causing the investigators to consider a different approach to care.

HIV care continuum model and its role in HCV

To improve the rate at which patients with HCV infection complete treatment within their clinics, the researchers formed a panel to determine necessary interventions that could reduce barriers to care.

The HIV care continuum came into play. They chose this model based on knowledge that HCV and HIV share the same care continuum with similar goals in diagnosis, linkage to care, retention, and suppression.

Based on the consensus of the panel and consideration of the HIV care continuum model, they identified a number of interventions needed to mitigate HCV treatment barriers. These included the incorporation of peer navigators or linkage-to-care (LCC) coordinators, use of the mobile medical unit, greater implementation of onsite lab visits, and medication-assisted treatment.

The LCC coordinators proved to be particularly important, as these team members helped assist patients with social and financial support to address challenges with access to treatment. These coordinators can also help patients gain access to specialized providers, ultimately improving the chance of successful HCV management.

Additionally, LCC coordinators may help identify and reduce barriers associated with housing, transportation, and nutrition. Frequent patient contact by the LCC coordinators can encourage adherence and promote risk reduction education, such as providing referrals to needle exchange services.

“Linking individuals to care with providers who are familiar with the treatment cascade could help improve retention and should be a top priority for those involved in HCV screening and treatment,” said LaMoy. “An environment with knowledge, lack of judgment, and a tenacious need to heal the community that welcomes those with barriers to care is exactly what is needed for the patients in our program.”

National, community challenges fuel barriers to HCV treatment access

Substance use, trauma histories, and mental health problems can negatively affect care engagement and must be addressed before the benefits of HCV therapy can be realized.

Addressing these issues isn’t always easy, said Kathleen Bernock, FNP-BC, AACRN, AAHIVS, of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Family Health Center in New York City, in an email to Medscape Medical News. She pointed out that several states have harsh restrictions on who is able to access HCV treatment, and some states will not approve certain medications for people who actively use drugs.

“Even for states without these restrictions, many health systems are difficult to navigate and may not be welcoming to persons actively using,” said Bernock. Trauma-informed care can also be difficult to translate into clinics, she added.

“Decentralizing care to the communities most affected would greatly help mitigate these barriers,” suggested Bernock. Decentralization, she explained, might include co-locating services such as syringe exchanges, utilizing community health workers and patient navigators, and expanding capacity-to-treat to community-based providers.

“[And] with the expansion of telehealth services in the US,” said Bernock, “we now have even more avenues to reach people that we never had before.”

LaMoy and Bernock have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Better linkage to care with providers who are familiar with both the HCV and HIV treatment cascade may not only improve access to HCV treatment, but it may also support patient retention, treatment adherence, and achievement of sustained virologic response (SVR) and viral suppression, said Stephanie LaMoy, CAN Community Health, North Point, Florida. She presented the results of a pilot study at the virtual Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2020 Annual Meeting.

In an effort to identify strategies most important for improving care access among their patients with HCV, LaMoy and her colleagues assessed 12-month patient data collected from three of their clinics. These data were evaluated for HCV treatment access, engagement, and outcomes.

The pilot study included 126 patients who were reactive and another 24 HCV-positive patients who were referred from other sources. Active HCV infections requiring treatment were reported in 144 patients.

A total of 59 patients were linked to care but did not initiate treatment for their active infection. LaMoy said there were multiple causes, including homelessness, substance abuse, and inability to maintain contact.

In contrast, 85 patients with HCV infection started treatment, but 35 of these patients did not complete their regimen. Out of the 50 patients who reported completing treatment, 30 did not return to the clinic to confirm sustained viral suppression.

According to LaMoy, this raised a red flag, causing the investigators to consider a different approach to care.

HIV care continuum model and its role in HCV

To improve the rate at which patients with HCV infection complete treatment within their clinics, the researchers formed a panel to determine necessary interventions that could reduce barriers to care.

The HIV care continuum came into play. They chose this model based on knowledge that HCV and HIV share the same care continuum with similar goals in diagnosis, linkage to care, retention, and suppression.

Based on the consensus of the panel and consideration of the HIV care continuum model, they identified a number of interventions needed to mitigate HCV treatment barriers. These included the incorporation of peer navigators or linkage-to-care (LCC) coordinators, use of the mobile medical unit, greater implementation of onsite lab visits, and medication-assisted treatment.

The LCC coordinators proved to be particularly important, as these team members helped assist patients with social and financial support to address challenges with access to treatment. These coordinators can also help patients gain access to specialized providers, ultimately improving the chance of successful HCV management.

Additionally, LCC coordinators may help identify and reduce barriers associated with housing, transportation, and nutrition. Frequent patient contact by the LCC coordinators can encourage adherence and promote risk reduction education, such as providing referrals to needle exchange services.

“Linking individuals to care with providers who are familiar with the treatment cascade could help improve retention and should be a top priority for those involved in HCV screening and treatment,” said LaMoy. “An environment with knowledge, lack of judgment, and a tenacious need to heal the community that welcomes those with barriers to care is exactly what is needed for the patients in our program.”

National, community challenges fuel barriers to HCV treatment access

Substance use, trauma histories, and mental health problems can negatively affect care engagement and must be addressed before the benefits of HCV therapy can be realized.

Addressing these issues isn’t always easy, said Kathleen Bernock, FNP-BC, AACRN, AAHIVS, of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Family Health Center in New York City, in an email to Medscape Medical News. She pointed out that several states have harsh restrictions on who is able to access HCV treatment, and some states will not approve certain medications for people who actively use drugs.

“Even for states without these restrictions, many health systems are difficult to navigate and may not be welcoming to persons actively using,” said Bernock. Trauma-informed care can also be difficult to translate into clinics, she added.

“Decentralizing care to the communities most affected would greatly help mitigate these barriers,” suggested Bernock. Decentralization, she explained, might include co-locating services such as syringe exchanges, utilizing community health workers and patient navigators, and expanding capacity-to-treat to community-based providers.

“[And] with the expansion of telehealth services in the US,” said Bernock, “we now have even more avenues to reach people that we never had before.”

LaMoy and Bernock have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Better linkage to care with providers who are familiar with both the HCV and HIV treatment cascade may not only improve access to HCV treatment, but it may also support patient retention, treatment adherence, and achievement of sustained virologic response (SVR) and viral suppression, said Stephanie LaMoy, CAN Community Health, North Point, Florida. She presented the results of a pilot study at the virtual Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2020 Annual Meeting.

In an effort to identify strategies most important for improving care access among their patients with HCV, LaMoy and her colleagues assessed 12-month patient data collected from three of their clinics. These data were evaluated for HCV treatment access, engagement, and outcomes.

The pilot study included 126 patients who were reactive and another 24 HCV-positive patients who were referred from other sources. Active HCV infections requiring treatment were reported in 144 patients.

A total of 59 patients were linked to care but did not initiate treatment for their active infection. LaMoy said there were multiple causes, including homelessness, substance abuse, and inability to maintain contact.

In contrast, 85 patients with HCV infection started treatment, but 35 of these patients did not complete their regimen. Out of the 50 patients who reported completing treatment, 30 did not return to the clinic to confirm sustained viral suppression.

According to LaMoy, this raised a red flag, causing the investigators to consider a different approach to care.

HIV care continuum model and its role in HCV

To improve the rate at which patients with HCV infection complete treatment within their clinics, the researchers formed a panel to determine necessary interventions that could reduce barriers to care.

The HIV care continuum came into play. They chose this model based on knowledge that HCV and HIV share the same care continuum with similar goals in diagnosis, linkage to care, retention, and suppression.

Based on the consensus of the panel and consideration of the HIV care continuum model, they identified a number of interventions needed to mitigate HCV treatment barriers. These included the incorporation of peer navigators or linkage-to-care (LCC) coordinators, use of the mobile medical unit, greater implementation of onsite lab visits, and medication-assisted treatment.