User login

Reactive Granulomatous Dermatitis: Variability of the Predominant Inflammatory Cell Type

To the Editor:

The term palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) has been proposed to encompass various conditions, including Winkelmann granuloma and superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis. More recently, PNGD has been classified along with interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction under a unifying rubric of reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD).1-4 The diagnosis of RGD can be challenging because of a range of clinical and histopathologic features as well as variable nomenclature.1-3,5

Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis classically manifests with papules and small plaques on the extensor extremities, with histopathology showing characteristic necrobiosis with both neutrophils and histiocytes.1,2,6 We report 6 cases of RGD, including an index case in which a predominance of neutrophils in the infiltrate impeded the diagnosis.

An 85-year-old woman (the index patient) presented with a several-week history of asymmetric crusted papules on the right upper extremity—3 lesions on the elbow and forearm and 1 lesion on a finger. She was an avid gardener with severe rheumatoid arthritis treated with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor therapy. An initial biopsy of the elbow revealed a dense infiltrate of neutrophils and sparse eosinophils within the dermis. Special stains for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast organisms were negative.

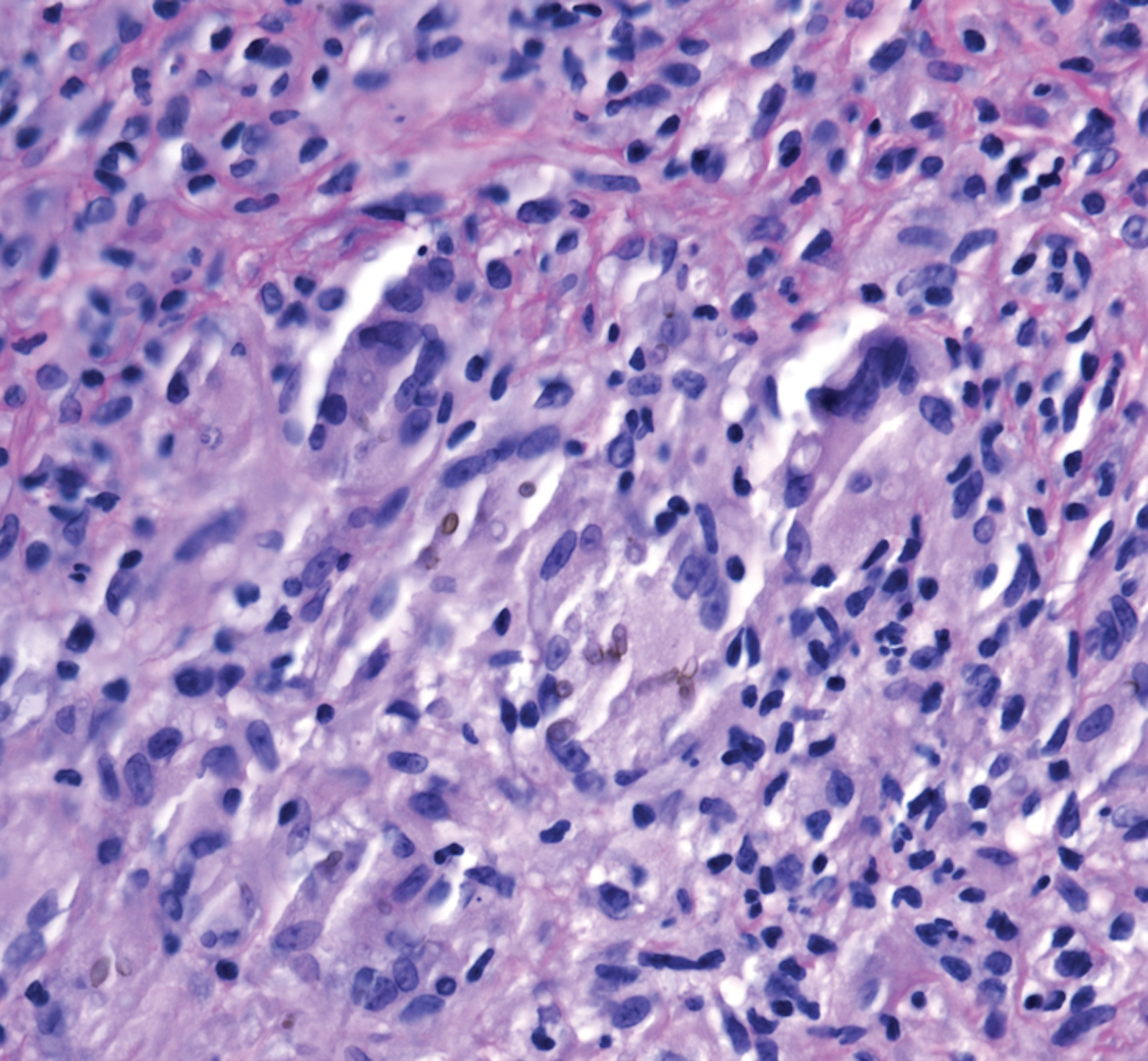

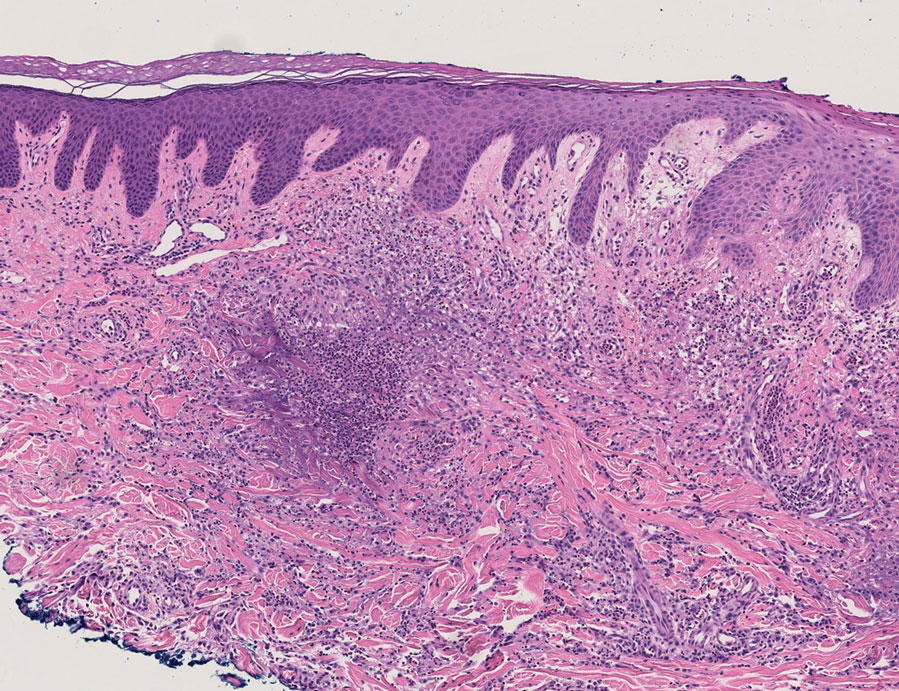

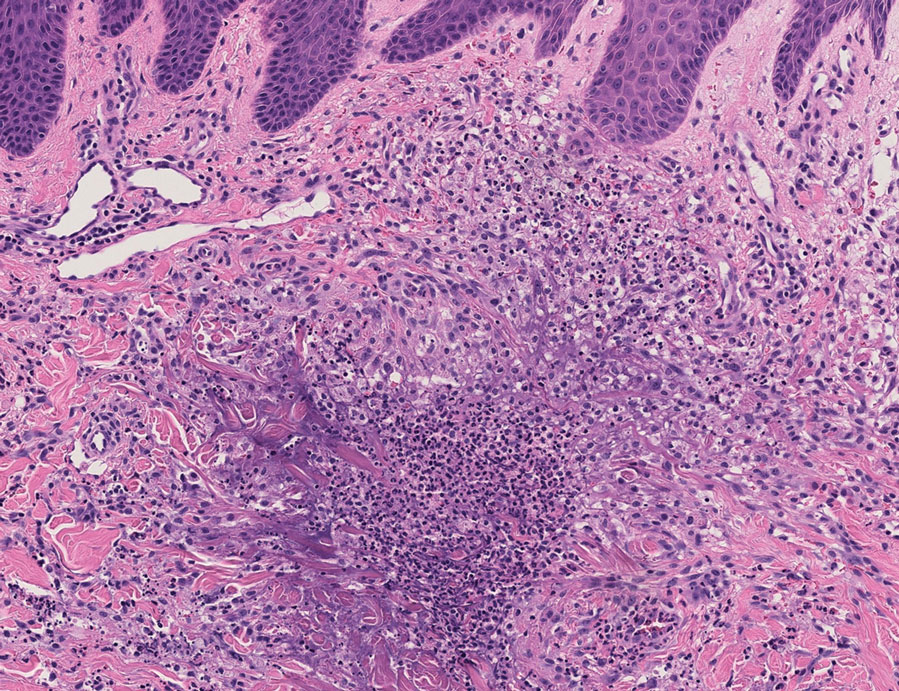

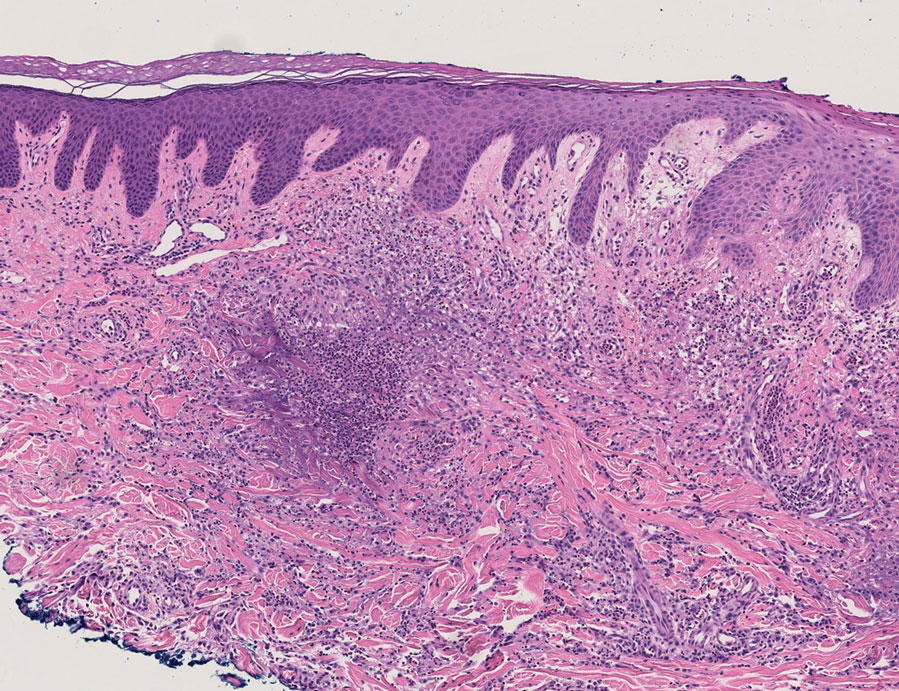

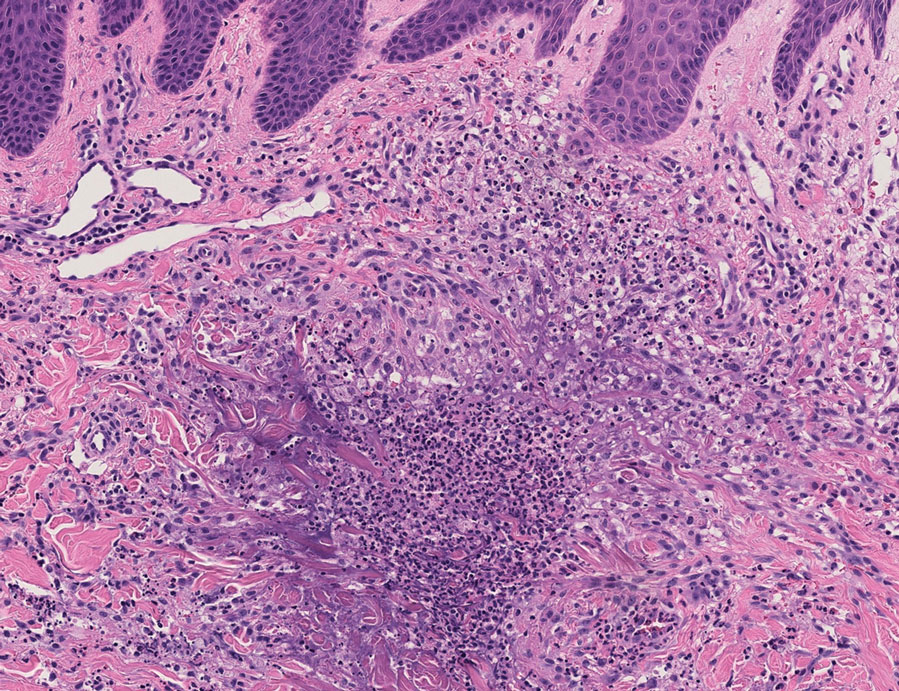

Because infection with sporotrichoid spread remained high in the differential diagnosis, the JAK inhibitor was discontinued and an antifungal agent was initiated. Given the persistence of the lesions, a subsequent biopsy of the right finger revealed scarce neutrophils and predominant histiocytes with rare foci of degenerated collagen. Sporotrichosis remained the leading diagnosis for these unilateral lesions. The patient subsequently developed additional crusted papules on the left arm (Figure 1). A biopsy of a left elbow lesion revealed palisades of histiocytes around degenerated collagen and collections of neutrophils compatible with RGD (Figures 2 and 3). Incidentally, the patient also presented with bilateral lower extremity palpable purpura, with a biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Antifungal therapy was discontinued and JAK inhibitor therapy resumed, with partial resolution of both the arm and right finger lesions and complete resolution of the lower extremity palpable purpura over several months.

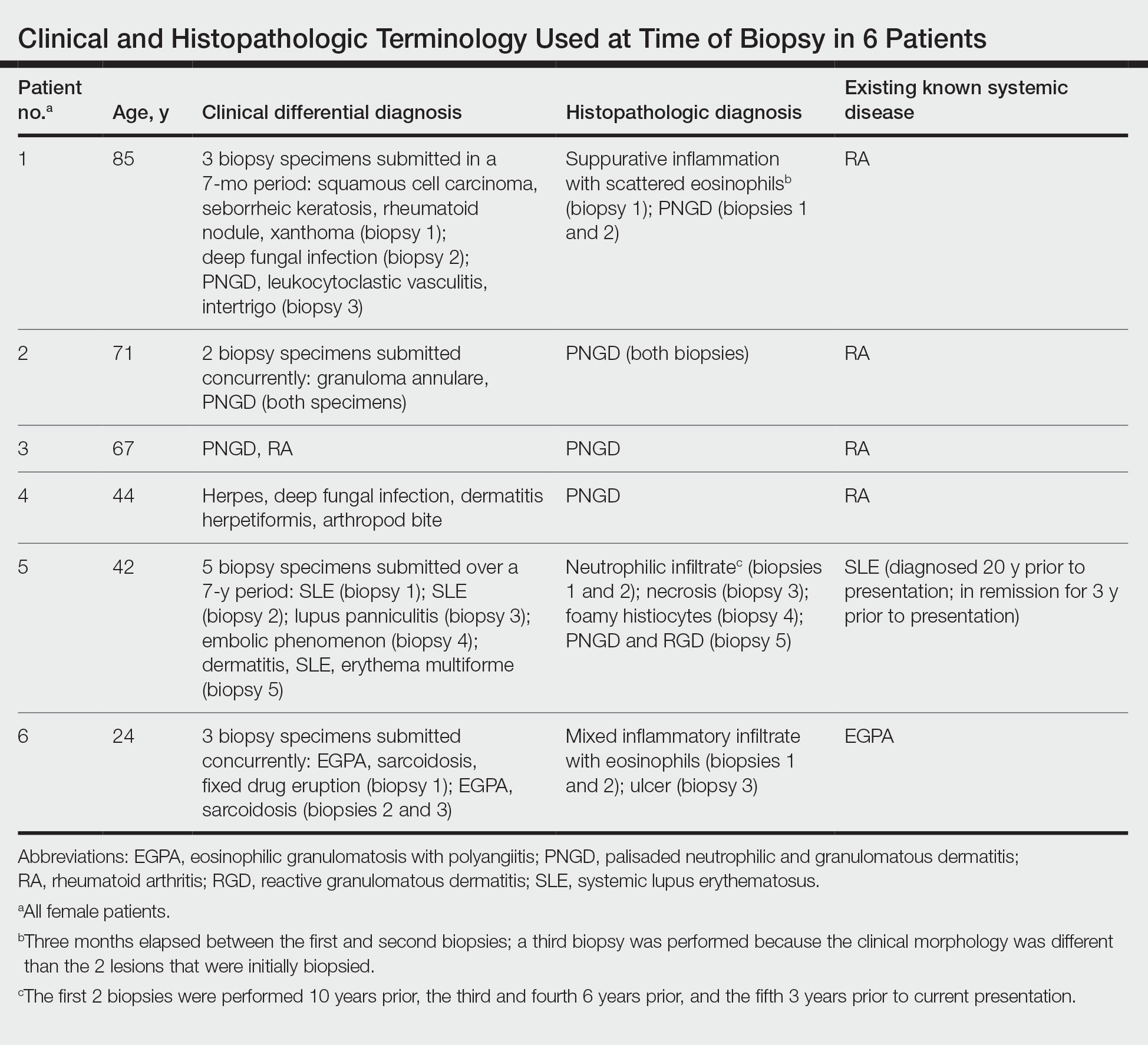

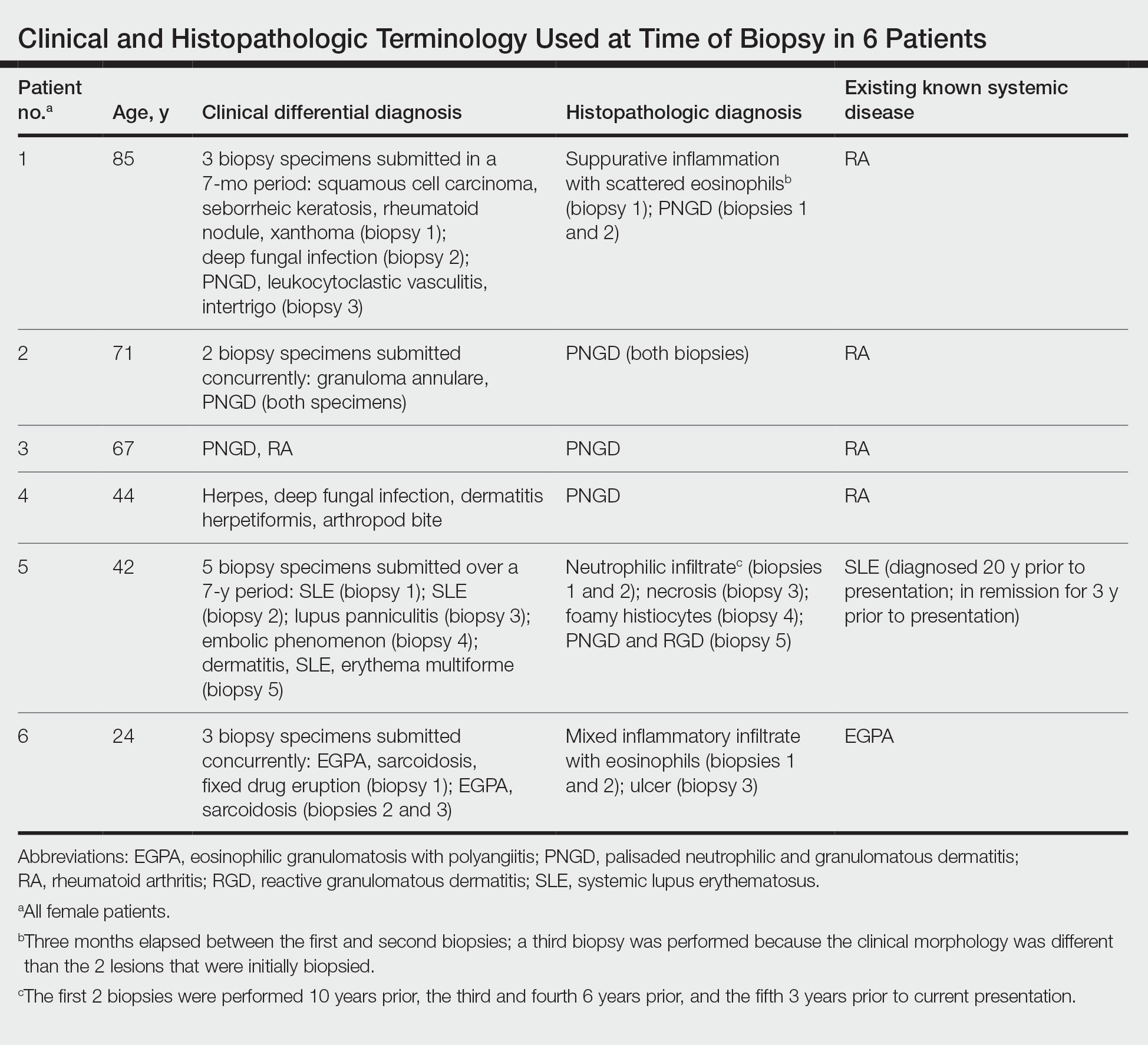

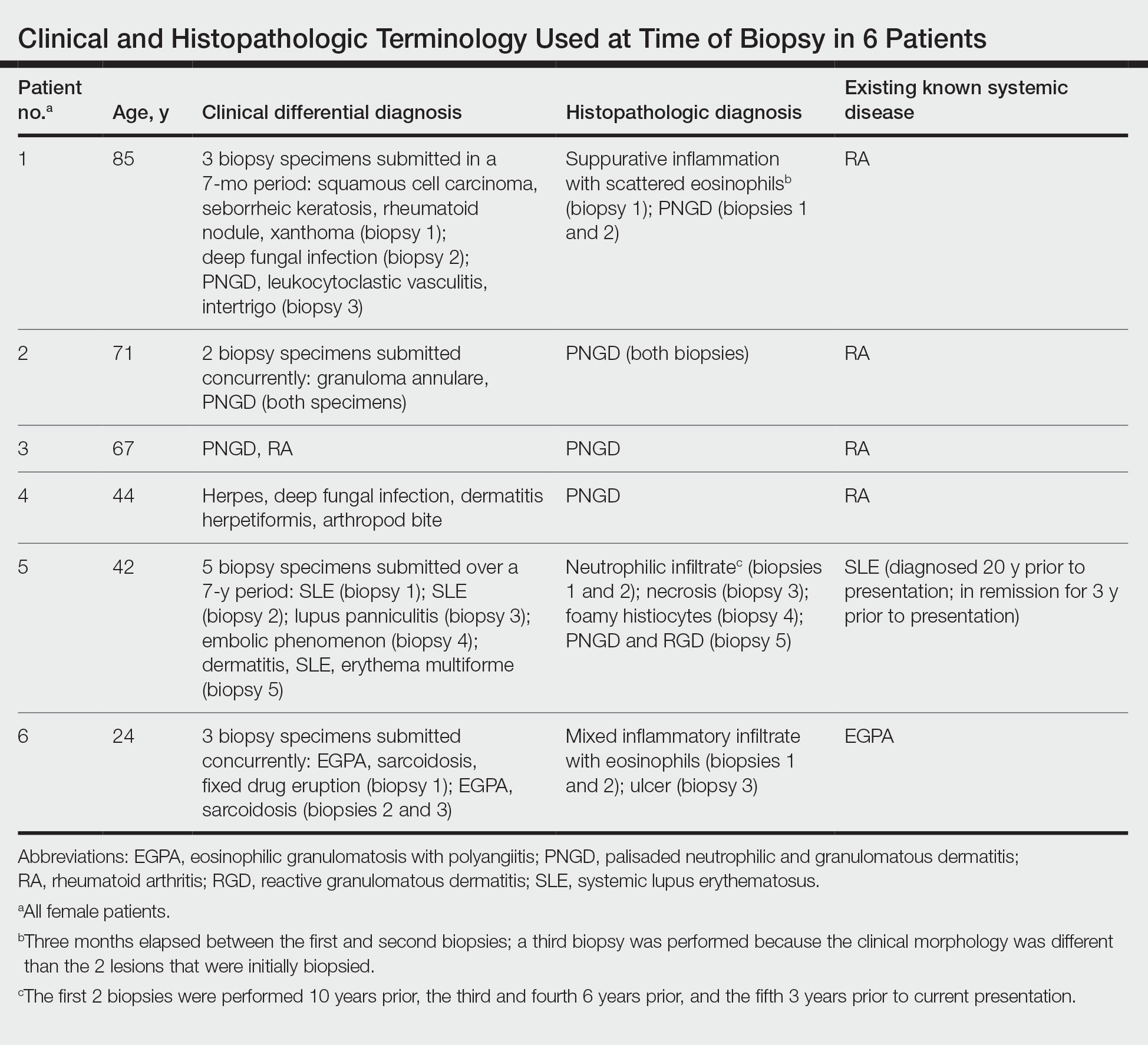

The dense neutrophilic infiltrate and asymmetric presentation seen in our index patient’s initial biopsy hindered categorization of the cutaneous findings as RGD in association with her rheumatoid arthritis rather than as an infectious process. To ascertain whether diagnosis also was difficult in other cases of RGD, we conducted a search of the Yale Dermatopathology database for the diagnosis palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, a term consistently used at our institution over the past decade. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut), and informed consent was waived. The search covered a 10-year period; 13 patients were found. Eight patients were eliminated because further clinical information or follow-up could not be obtained, leaving 5 additional cases (Table). The 8 eliminated cases were consultations submitted to the laboratory by outside pathologists from other institutions.

In one case (patient 5), the diagnosis of RGD was delayed for 7 years from first documentation of an RGD-compatible neutrophil-predominant infiltrate (Table). In 3 other cases, PNGD was in the clinical differential diagnosis. In patient 6 with known eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, biopsy findings included a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils, and the clinical and histopathologic findings were deemed compatible with RGD by group consensus at Grand Rounds.

In practice, a consistent unifying nomenclature has not been achieved for RGD and the diseases it encompasses—PNGD, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction. In this small series, a diagnosis of PNGD was given in the dermatopathology report only when biopsy specimens were characterized by histiocytes, neutrophils, and necrobiosis. Histopathology reports for neutrophil-predominant, histiocyte-predominant, and eosinophil-predominant cases did not mention PNGD or RGD, though potential association with systemic disease generally was noted.

Given the variability in the predominant inflammatory cell type in these patients, adding a qualifier to the histopathologic diagnosis—“RGD, eosinophil rich,” “RGD, histiocyte rich,” or “RGD, neutrophil rich”1—would underscore the range of inflammatory cells in this entity. Employing this terminology rather than stating a solely descriptive diagnosis such as neutrophilic infiltrate, which may bias clinicians toward an infectious process, would aid in the association of a given rash with systemic disease and may prevent unnecessary tissue sampling. Indeed, 3 patients in this small series underwent more than 2 biopsies; multiple procedures might have been avoided had there been better communication about the spectrum of inflammatory cells compatible with RGD.

The inflammatory infiltrate in biopsy specimens of RGD can be solely neutrophil or histiocyte predominant or even have prominent eosinophils depending on the stage of disease. Awareness of variability in the predominant inflammatory cell in RGD may facilitate an accurate diagnosis as well as an association with any underlying autoimmune process, thereby allowing better management and treatment.1

- Rosenbach M, English JC. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.005

- Wanat KA, Caplan A, Messenger E, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a useful and encompassing term. JAAD Intl. 2022;7:126-128. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.03.004

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283. doi:10.1001/archderm.1994.01690100062010

- Dykman CJ, Galens GJ, Good AE. Linear subcutaneous bands in rheumatoid arthritis: an unusual form of rheumatoid granuloma. Ann Intern Med. 1965;63:134-140. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-63-1-134

- Rodríguez-Garijo N, Bielsa I, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis as a histological pattern including manifestations of interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomtous dermatitis: a study of 52 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:988-994. doi:10.1111/jdv.17010

- Kalen JE, Shokeen D, Ramos-Caro F, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis: spectrum of histologic findings in a single patient. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:425. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.06.010

To the Editor:

The term palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) has been proposed to encompass various conditions, including Winkelmann granuloma and superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis. More recently, PNGD has been classified along with interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction under a unifying rubric of reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD).1-4 The diagnosis of RGD can be challenging because of a range of clinical and histopathologic features as well as variable nomenclature.1-3,5

Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis classically manifests with papules and small plaques on the extensor extremities, with histopathology showing characteristic necrobiosis with both neutrophils and histiocytes.1,2,6 We report 6 cases of RGD, including an index case in which a predominance of neutrophils in the infiltrate impeded the diagnosis.

An 85-year-old woman (the index patient) presented with a several-week history of asymmetric crusted papules on the right upper extremity—3 lesions on the elbow and forearm and 1 lesion on a finger. She was an avid gardener with severe rheumatoid arthritis treated with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor therapy. An initial biopsy of the elbow revealed a dense infiltrate of neutrophils and sparse eosinophils within the dermis. Special stains for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast organisms were negative.

Because infection with sporotrichoid spread remained high in the differential diagnosis, the JAK inhibitor was discontinued and an antifungal agent was initiated. Given the persistence of the lesions, a subsequent biopsy of the right finger revealed scarce neutrophils and predominant histiocytes with rare foci of degenerated collagen. Sporotrichosis remained the leading diagnosis for these unilateral lesions. The patient subsequently developed additional crusted papules on the left arm (Figure 1). A biopsy of a left elbow lesion revealed palisades of histiocytes around degenerated collagen and collections of neutrophils compatible with RGD (Figures 2 and 3). Incidentally, the patient also presented with bilateral lower extremity palpable purpura, with a biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Antifungal therapy was discontinued and JAK inhibitor therapy resumed, with partial resolution of both the arm and right finger lesions and complete resolution of the lower extremity palpable purpura over several months.

The dense neutrophilic infiltrate and asymmetric presentation seen in our index patient’s initial biopsy hindered categorization of the cutaneous findings as RGD in association with her rheumatoid arthritis rather than as an infectious process. To ascertain whether diagnosis also was difficult in other cases of RGD, we conducted a search of the Yale Dermatopathology database for the diagnosis palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, a term consistently used at our institution over the past decade. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut), and informed consent was waived. The search covered a 10-year period; 13 patients were found. Eight patients were eliminated because further clinical information or follow-up could not be obtained, leaving 5 additional cases (Table). The 8 eliminated cases were consultations submitted to the laboratory by outside pathologists from other institutions.

In one case (patient 5), the diagnosis of RGD was delayed for 7 years from first documentation of an RGD-compatible neutrophil-predominant infiltrate (Table). In 3 other cases, PNGD was in the clinical differential diagnosis. In patient 6 with known eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, biopsy findings included a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils, and the clinical and histopathologic findings were deemed compatible with RGD by group consensus at Grand Rounds.

In practice, a consistent unifying nomenclature has not been achieved for RGD and the diseases it encompasses—PNGD, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction. In this small series, a diagnosis of PNGD was given in the dermatopathology report only when biopsy specimens were characterized by histiocytes, neutrophils, and necrobiosis. Histopathology reports for neutrophil-predominant, histiocyte-predominant, and eosinophil-predominant cases did not mention PNGD or RGD, though potential association with systemic disease generally was noted.

Given the variability in the predominant inflammatory cell type in these patients, adding a qualifier to the histopathologic diagnosis—“RGD, eosinophil rich,” “RGD, histiocyte rich,” or “RGD, neutrophil rich”1—would underscore the range of inflammatory cells in this entity. Employing this terminology rather than stating a solely descriptive diagnosis such as neutrophilic infiltrate, which may bias clinicians toward an infectious process, would aid in the association of a given rash with systemic disease and may prevent unnecessary tissue sampling. Indeed, 3 patients in this small series underwent more than 2 biopsies; multiple procedures might have been avoided had there been better communication about the spectrum of inflammatory cells compatible with RGD.

The inflammatory infiltrate in biopsy specimens of RGD can be solely neutrophil or histiocyte predominant or even have prominent eosinophils depending on the stage of disease. Awareness of variability in the predominant inflammatory cell in RGD may facilitate an accurate diagnosis as well as an association with any underlying autoimmune process, thereby allowing better management and treatment.1

To the Editor:

The term palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD) has been proposed to encompass various conditions, including Winkelmann granuloma and superficial ulcerating rheumatoid necrobiosis. More recently, PNGD has been classified along with interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction under a unifying rubric of reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD).1-4 The diagnosis of RGD can be challenging because of a range of clinical and histopathologic features as well as variable nomenclature.1-3,5

Palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis classically manifests with papules and small plaques on the extensor extremities, with histopathology showing characteristic necrobiosis with both neutrophils and histiocytes.1,2,6 We report 6 cases of RGD, including an index case in which a predominance of neutrophils in the infiltrate impeded the diagnosis.

An 85-year-old woman (the index patient) presented with a several-week history of asymmetric crusted papules on the right upper extremity—3 lesions on the elbow and forearm and 1 lesion on a finger. She was an avid gardener with severe rheumatoid arthritis treated with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor therapy. An initial biopsy of the elbow revealed a dense infiltrate of neutrophils and sparse eosinophils within the dermis. Special stains for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast organisms were negative.

Because infection with sporotrichoid spread remained high in the differential diagnosis, the JAK inhibitor was discontinued and an antifungal agent was initiated. Given the persistence of the lesions, a subsequent biopsy of the right finger revealed scarce neutrophils and predominant histiocytes with rare foci of degenerated collagen. Sporotrichosis remained the leading diagnosis for these unilateral lesions. The patient subsequently developed additional crusted papules on the left arm (Figure 1). A biopsy of a left elbow lesion revealed palisades of histiocytes around degenerated collagen and collections of neutrophils compatible with RGD (Figures 2 and 3). Incidentally, the patient also presented with bilateral lower extremity palpable purpura, with a biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Antifungal therapy was discontinued and JAK inhibitor therapy resumed, with partial resolution of both the arm and right finger lesions and complete resolution of the lower extremity palpable purpura over several months.

The dense neutrophilic infiltrate and asymmetric presentation seen in our index patient’s initial biopsy hindered categorization of the cutaneous findings as RGD in association with her rheumatoid arthritis rather than as an infectious process. To ascertain whether diagnosis also was difficult in other cases of RGD, we conducted a search of the Yale Dermatopathology database for the diagnosis palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, a term consistently used at our institution over the past decade. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Yale University (New Haven, Connecticut), and informed consent was waived. The search covered a 10-year period; 13 patients were found. Eight patients were eliminated because further clinical information or follow-up could not be obtained, leaving 5 additional cases (Table). The 8 eliminated cases were consultations submitted to the laboratory by outside pathologists from other institutions.

In one case (patient 5), the diagnosis of RGD was delayed for 7 years from first documentation of an RGD-compatible neutrophil-predominant infiltrate (Table). In 3 other cases, PNGD was in the clinical differential diagnosis. In patient 6 with known eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, biopsy findings included a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with eosinophils, and the clinical and histopathologic findings were deemed compatible with RGD by group consensus at Grand Rounds.

In practice, a consistent unifying nomenclature has not been achieved for RGD and the diseases it encompasses—PNGD, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction. In this small series, a diagnosis of PNGD was given in the dermatopathology report only when biopsy specimens were characterized by histiocytes, neutrophils, and necrobiosis. Histopathology reports for neutrophil-predominant, histiocyte-predominant, and eosinophil-predominant cases did not mention PNGD or RGD, though potential association with systemic disease generally was noted.

Given the variability in the predominant inflammatory cell type in these patients, adding a qualifier to the histopathologic diagnosis—“RGD, eosinophil rich,” “RGD, histiocyte rich,” or “RGD, neutrophil rich”1—would underscore the range of inflammatory cells in this entity. Employing this terminology rather than stating a solely descriptive diagnosis such as neutrophilic infiltrate, which may bias clinicians toward an infectious process, would aid in the association of a given rash with systemic disease and may prevent unnecessary tissue sampling. Indeed, 3 patients in this small series underwent more than 2 biopsies; multiple procedures might have been avoided had there been better communication about the spectrum of inflammatory cells compatible with RGD.

The inflammatory infiltrate in biopsy specimens of RGD can be solely neutrophil or histiocyte predominant or even have prominent eosinophils depending on the stage of disease. Awareness of variability in the predominant inflammatory cell in RGD may facilitate an accurate diagnosis as well as an association with any underlying autoimmune process, thereby allowing better management and treatment.1

- Rosenbach M, English JC. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.005

- Wanat KA, Caplan A, Messenger E, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a useful and encompassing term. JAAD Intl. 2022;7:126-128. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.03.004

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283. doi:10.1001/archderm.1994.01690100062010

- Dykman CJ, Galens GJ, Good AE. Linear subcutaneous bands in rheumatoid arthritis: an unusual form of rheumatoid granuloma. Ann Intern Med. 1965;63:134-140. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-63-1-134

- Rodríguez-Garijo N, Bielsa I, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis as a histological pattern including manifestations of interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomtous dermatitis: a study of 52 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:988-994. doi:10.1111/jdv.17010

- Kalen JE, Shokeen D, Ramos-Caro F, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis: spectrum of histologic findings in a single patient. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:425. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.06.010

- Rosenbach M, English JC. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a review of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, and a proposed reclassification. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:373-387. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.005

- Wanat KA, Caplan A, Messenger E, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis: a useful and encompassing term. JAAD Intl. 2022;7:126-128. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.03.004

- Chu P, Connolly MK, LeBoit PE. The histopathologic spectrum of palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis in patients with collagen vascular disease. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1278-1283. doi:10.1001/archderm.1994.01690100062010

- Dykman CJ, Galens GJ, Good AE. Linear subcutaneous bands in rheumatoid arthritis: an unusual form of rheumatoid granuloma. Ann Intern Med. 1965;63:134-140. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-63-1-134

- Rodríguez-Garijo N, Bielsa I, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Reactive granulomatous dermatitis as a histological pattern including manifestations of interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic and granulomtous dermatitis: a study of 52 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:988-994. doi:10.1111/jdv.17010

- Kalen JE, Shokeen D, Ramos-Caro F, et al. Palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis: spectrum of histologic findings in a single patient. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:425. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.06.010

Practice Points

- The term reactive granulomatous dermatitis (RGD) provides a unifying rubric for palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, and interstitial granulomatous drug reaction.

- Reactive granulomatous dermatitis can have a variable infiltrate that includes neutrophils, histiocytes, and/or eosinophils.

- Awareness of the variability in inflammatory cell type is important for the diagnosis of RGD.

Recurrent Cutaneous Exophiala Phaeohyphomycosis in an Immunosuppressed Patient

To the Editor:

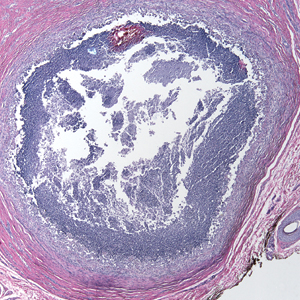

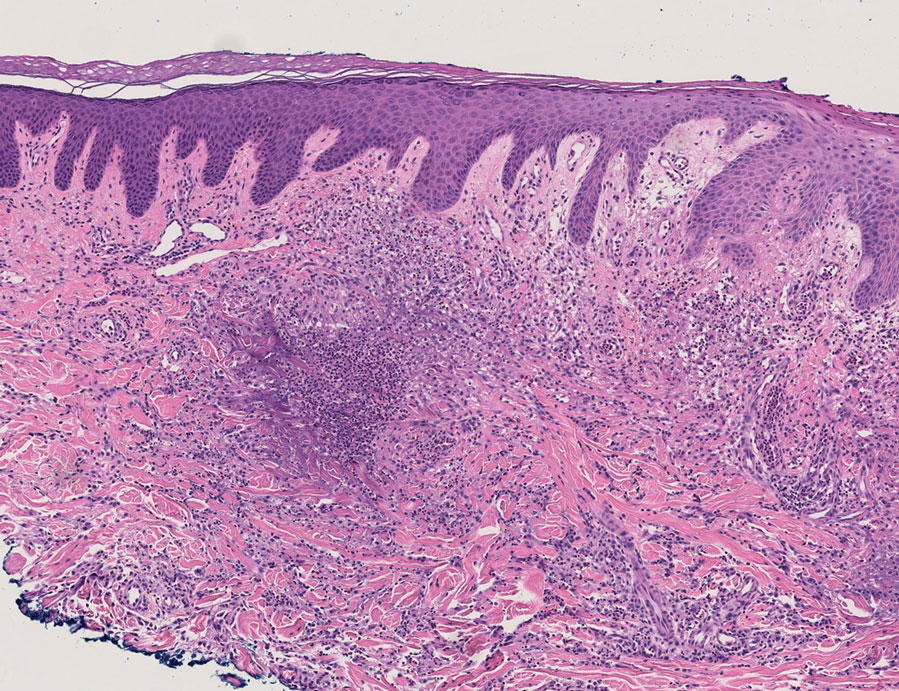

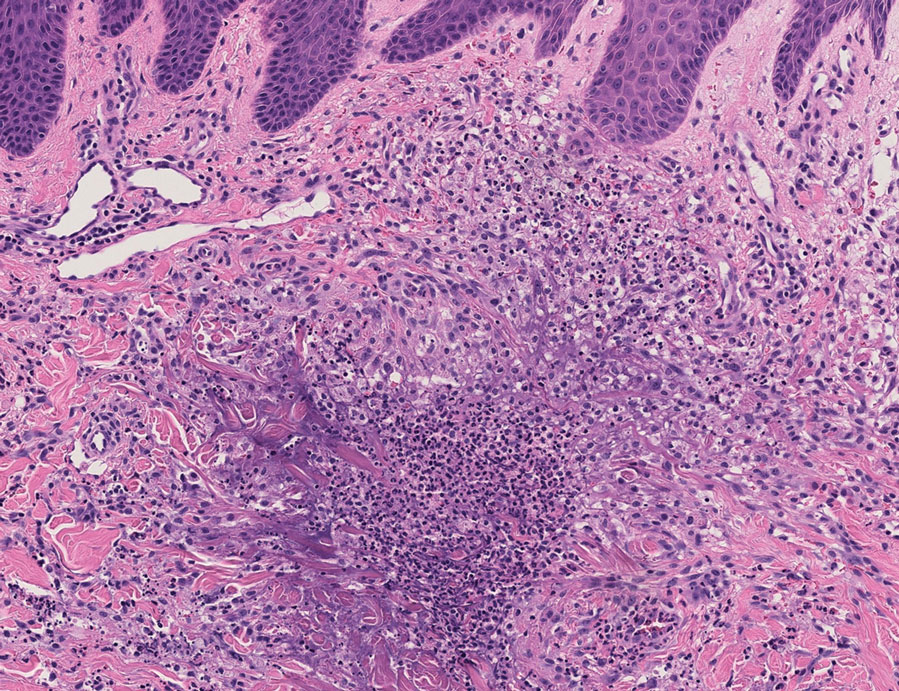

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

Practice Points

- Phaeohyphomycosis is an infection with dematiaceous fungi that most commonly affects immunosuppressed patients.

- Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis may present with nodulocystic lesions that recur over the course of years.

- Tissue fungal culture should be obtained when the diagnosis is suspected, as the risk for dissemination is related to the culprit organism.

- Surgical excision with close follow-up may be an appropriate management strategy for patients on immunosuppressive medications to avoid interactions with azole therapy.