User login

Cancer Data Trends 2025

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

In this issue:

- Access, Race, and "Colon Age": Improving CRC Screening

- Lung Cancer: Mortality Trends in Veterans and New Treatments

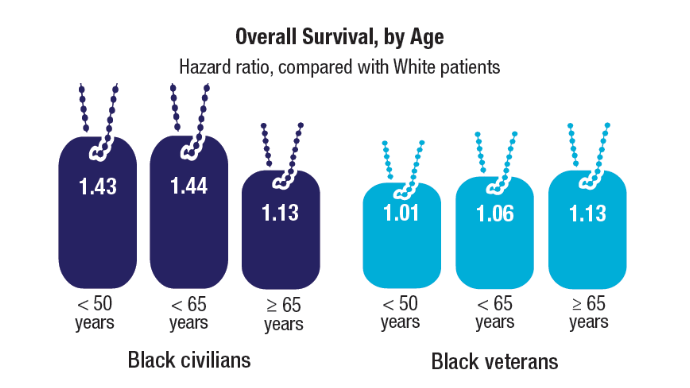

- Racial Disparities, Germline Testing, and Improved Overall Survival in Prostate Cancer

- Breast and Uterine Cancer: Screening Guidelines, Genetic Testing, and Mortality Trends

- HCC Updates: Quality Care Framework and Risk Stratification Data

- Rising Kidney Cancer Cases and Emerging Treatments for Veterans

- Advances in Blood Cancer Care for Veterans

- AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

- Brain Cancer: Epidemiology, TBI, and New Treatments

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

In this issue:

- Access, Race, and "Colon Age": Improving CRC Screening

- Lung Cancer: Mortality Trends in Veterans and New Treatments

- Racial Disparities, Germline Testing, and Improved Overall Survival in Prostate Cancer

- Breast and Uterine Cancer: Screening Guidelines, Genetic Testing, and Mortality Trends

- HCC Updates: Quality Care Framework and Risk Stratification Data

- Rising Kidney Cancer Cases and Emerging Treatments for Veterans

- Advances in Blood Cancer Care for Veterans

- AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

- Brain Cancer: Epidemiology, TBI, and New Treatments

The annual issue of Cancer Data Trends, produced in collaboration with the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), highlights the latest research in some of the top cancers impacting US veterans.

In this issue:

- Access, Race, and "Colon Age": Improving CRC Screening

- Lung Cancer: Mortality Trends in Veterans and New Treatments

- Racial Disparities, Germline Testing, and Improved Overall Survival in Prostate Cancer

- Breast and Uterine Cancer: Screening Guidelines, Genetic Testing, and Mortality Trends

- HCC Updates: Quality Care Framework and Risk Stratification Data

- Rising Kidney Cancer Cases and Emerging Treatments for Veterans

- Advances in Blood Cancer Care for Veterans

- AI-Based Risk Stratification for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas: AIROC

- Brain Cancer: Epidemiology, TBI, and New Treatments

Unique Presentation of Postpartum Hypereosinophilic Syndrome With Atypical Features and Therapeutic Challenges

Unique Presentation of Postpartum Hypereosinophilic Syndrome With Atypical Features and Therapeutic Challenges

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is defined by marked, persistent absolute eosinophil count (AEC) > 1500 cells/μL on ≥ 2 peripheral smears separated by ≥ 1 month with evidence of accompanied end-organ damage, in the absence of other causes of eosinophilia such as malignancy, atopy, or parasitic infections.1-5 Hypereosinophilic infiltration can impact almost every organ system; however, the most profound complications in patients with HES are related to leukemias and cardiac manifestations of the disease.3,4 Although rare, the associated morbidity and mortality of HES are considerable, making prompt recognition and treatment essential. Management involves targeted therapy based on pathologic classification of HES and on decreasing associated inflammation, fibrosis, and end-organ damage.3,5-7

The patient in this case report met the diagnostic criteria for HES. However, this patient had several clinical and laboratory features that made it difficult to characterize a specific HES variant. Moreover, she had additional immunomodulating factors in the setting of pregnancy. This is the first documented case of HES of undetermined etiology diagnosed postpartum and managed in the setting of a new pregnancy.2,8

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year-old female active-duty military service member with allergic rhinitis and a history of childhood eczema was referred to allergy/immunology for evaluation of a new, progressive pruritic rash. Symptoms started 3 months after the birth of her first child, with a new diffuse erythematous skin rash sparing her palms, soles, and mucosal surfaces. Given her history of atopy, the rash was initially treated as severe atopic dermatitis with appropriate topical medications. The rash gradually worsened, with the development of intermittent facial swelling, night sweats, dyspnea, recurrent epigastric abdominal pain, and nausea with vomiting, resulting in decreased oral intake and weight loss.

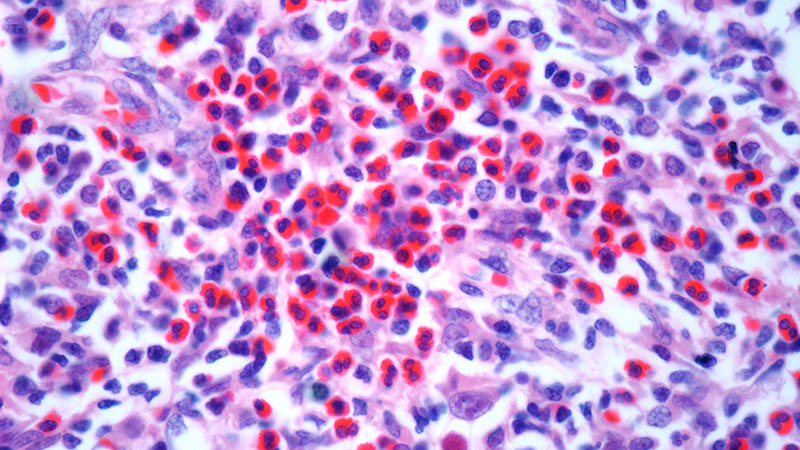

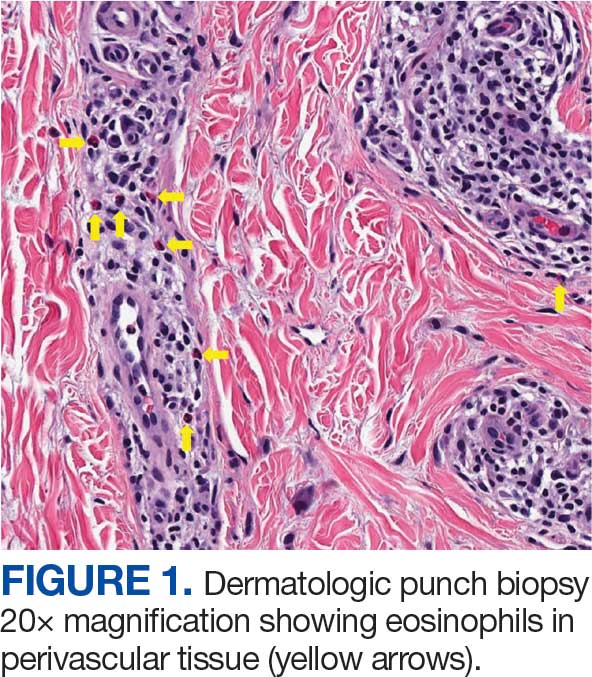

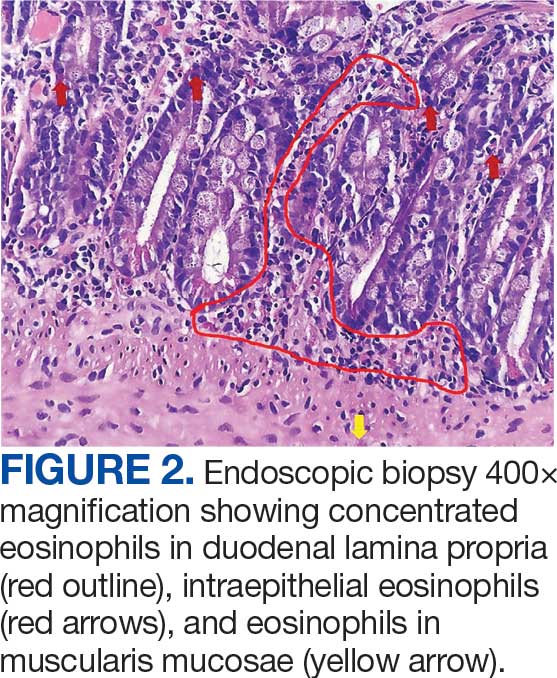

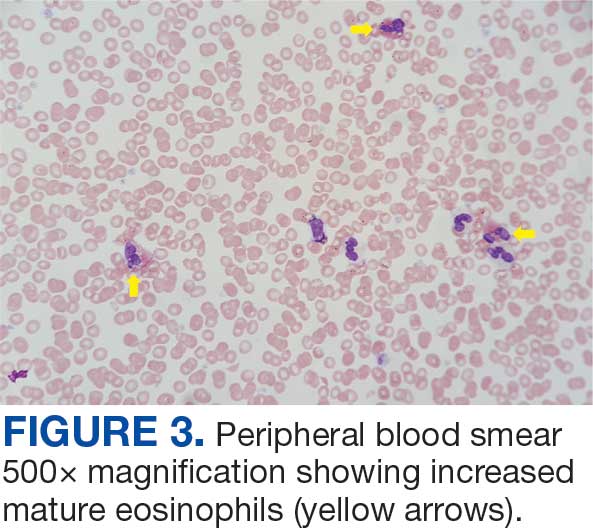

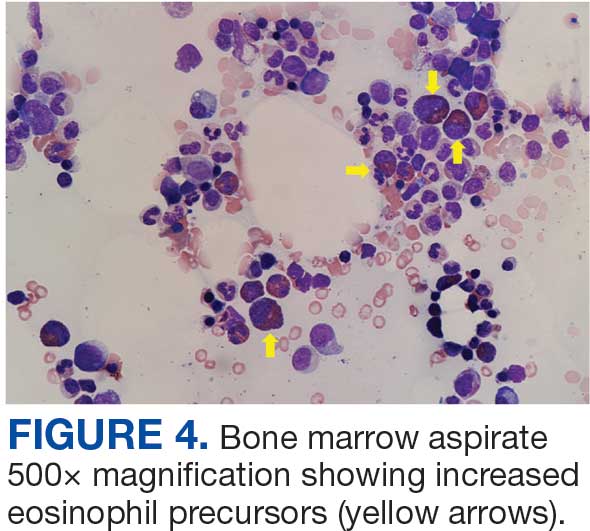

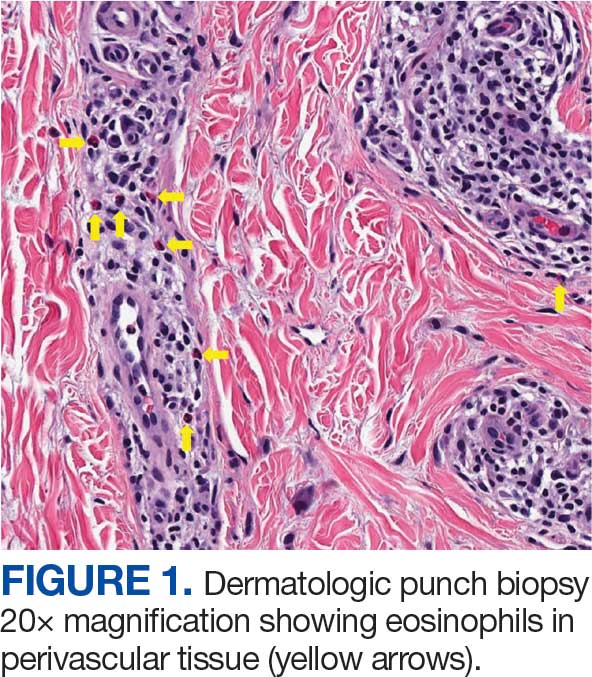

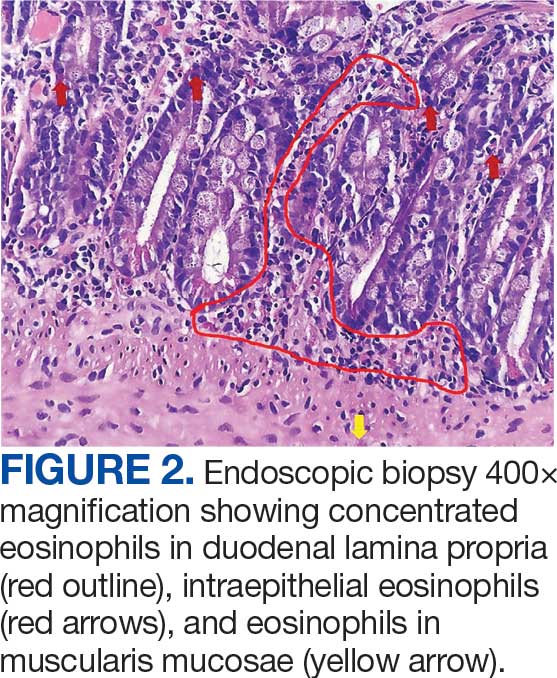

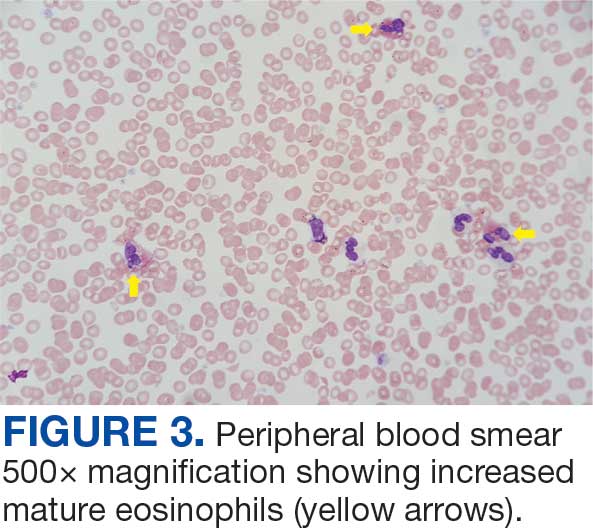

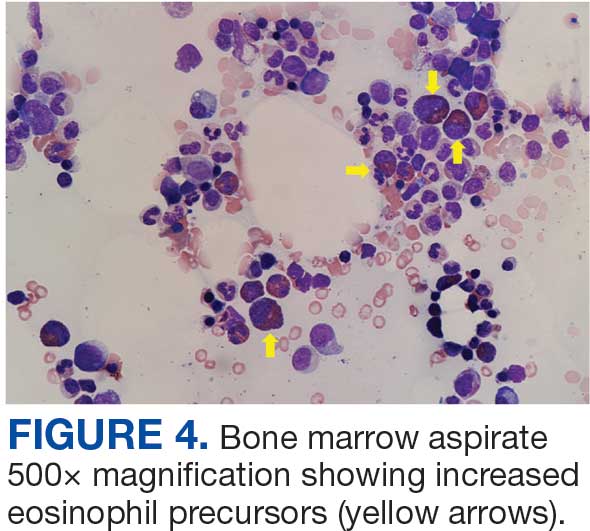

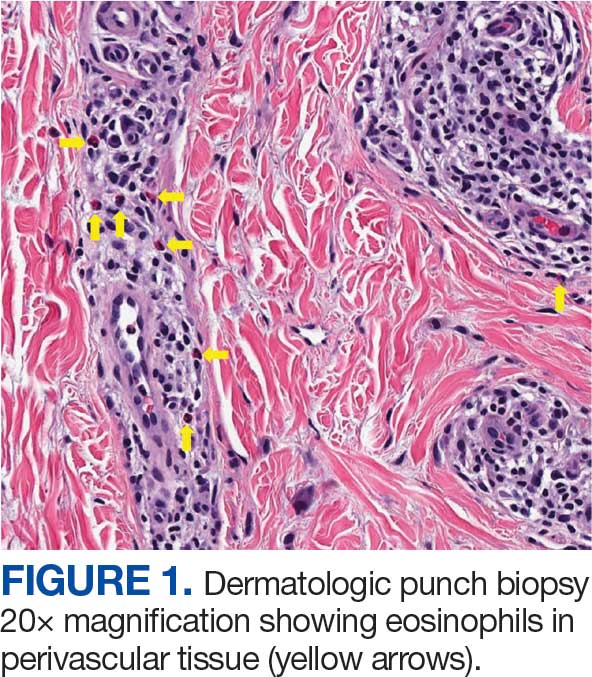

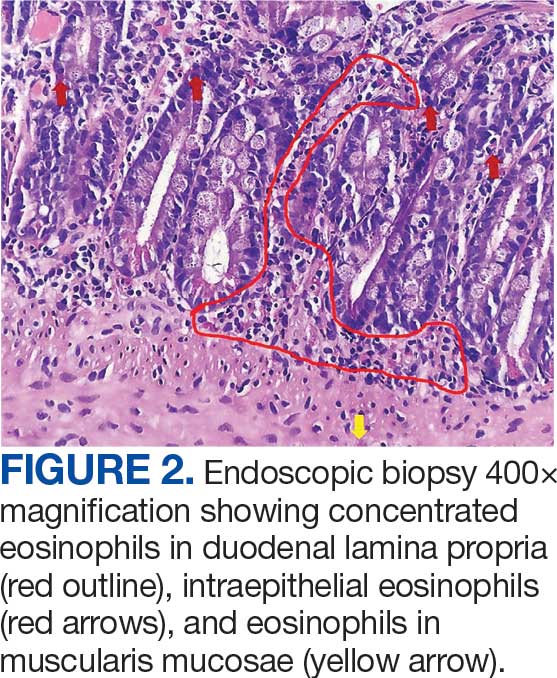

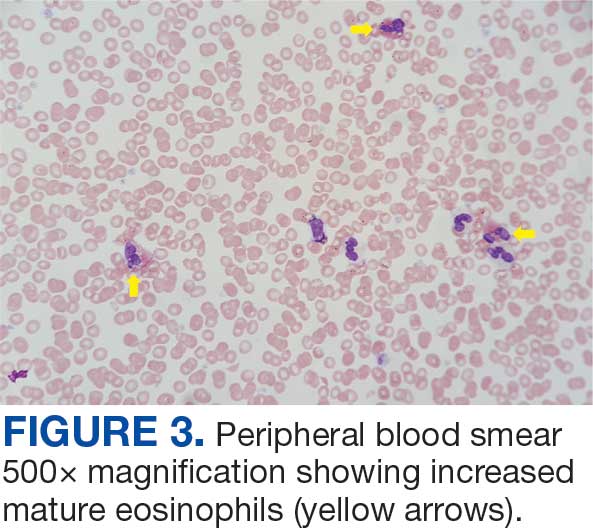

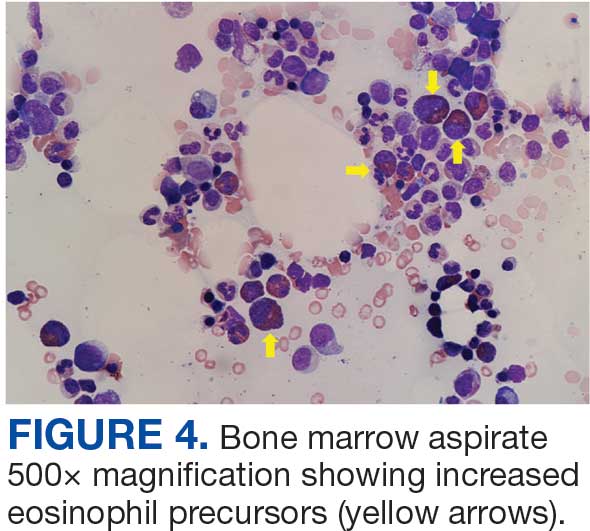

The patient was hospitalized and received an expedited multidisciplinary evaluation by dermatology, hematology/oncology, and gastroenterology. Her AEC of 4787 cells/μL peaked on admission and was markedly elevated from the 1070 cells/μL reported in the third trimester of her pregnancy. She was found to have mature eosinophilia on skin biopsy (Figure 1), endoscopic duodenal biopsy (Figure 2), peripheral blood smear (Figure 3), and bone marrow biopsy (Figure 4).

Radiographic imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed hepatomegaly without detectable neoplasm. There was no clinical evidence of cardiac involvement, and evaluation with electrocardiography and echocardiography did not indicate myocarditis. Extensive laboratory testing revealed no genetic mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants of HES.

The patient received topical emollients, omeprazole 40 mg daily, and ondansetron 8 mg 3 times daily as needed for symptom management, and was started on oral prednisone 40 mg daily with improvement in dyspnea, night sweats, and gastrointestinal complaints. During the patient's 6-day hospitalization and treatment, her AECs gradually decreased to 2110 cells/μL, and decreased to 1600 cells/μL over the course of a month, remaining in the hypereosinophilic range. The patient was discovered to be pregnant while symptoms were improving, resulting in stepwise discontinuation of oral steroids, but she reported continued improvement in symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Peripheral eosinophilia has a broad differential diagnoses, including HES, parasitic infections, atopic hypersensitivity diseases, eosinophilic lung diseases, eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, vasculitides such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, genetic syndromes predisposing to eosinophilia, episodic angioedema with eosinophilia, and chronic metabolic disease with adrenal insufficiency.1-5 HES, although rare, is a disease process with potentially devastating associated morbidity and mortality if not promptly recognized and treated. HES is further delineated by hypereosinophilia with associated eosinophil-mediated organ damage or dysfunction.3-5

Clinical manifestations of HES can differ greatly depending on the HES variant and degree of organ involvement at the time of diagnosis and throughout the disease course. Patients with HES, as well as those with asymptomatic eosinophilia or hypereosinophilia, should be closely monitored for disease progression. In addition to trending peripheral AECs, clinicians should screen for symptoms of organ involvement and perform targeted evaluation of the suspected organs to promptly identify early signs of organ involvement and initiate treatment.1-4 Recommendations regarding screening intervals vary widely from monthly to annually, depending on a patient’s specific clinical picture.

HES has been subdivided into clinically relevant variants, including myeloproliferative (M-HES), T lymphocytic (L-HES), organ-restricted (or overlap) HES, familial HES, idiopathic HES, and specific syndromes with associated hypereosinophilia.3-5,9 Patients with M-HES have elevated circulating leukocyte precursors and clinical manifestations, including but not limited to hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. The most commonly associated genetic mutations include the FIP1L1-PDGFR-α fusion, BCR-ABL1, PDGFRA/B, JAK2, KIT, and FGFR1.3-6 L-HES usually has predominant skin and soft tissue involvement secondary to immunoglobulin E-mediated actions with clonal expansion of T cells (most commonly CD3-4+ or CD3+CD4-CD8-).3,5,6 Familial HES, a rare variant, follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and is usually present at birth. It involves chromosome 5, which contains genes coding for cytokines that drive eosinophilic proliferation, including interleukin (IL)-3, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.5,9 Hypereosinophilia in the setting of end-organ damage restricted to a single organ is considered organ-restricted HES. There can be significant hepatic and gastrointestinal dysfunction, with or without malabsorption.

HES can also manifest with hematologic malignancy, restrictive obliterative cardiomyopathies, renal injury manifested by hematuria and electrolyte derangements, and neurologic complications including hemiparesis, dysarthria, and even coma.6 Endothelial damage due to eosinophil-driven inflammation can result in thrombus formation and increased risk of thromboembolic events in various organs.3 Idiopathic HES, otherwise known as HES of unknown etiology or significance, is a diagnosis of exclusion and constitutes a cohort of patients who do not fit into the other delineated categories.3-5 These patients often have multisystem involvement, making classification and treatment a challenge.5

The patient described in this case met the diagnostic criteria for HES, but her complicated clinical and laboratory features were challenging to characterize into a specific variant of HES. Organ-restricted HES was ruled out due to skin, marrow, and duodenal infiltration. She also had the potential for lung involvement based on her clinical symptoms, however no biopsy was obtained. Laboratory testing revealed no deletions or mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants. Her multisystem involvement without an underlying associated syndrome suggests idiopathic HES or HES of undetermined significance.1-5

Most patients with HES are diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50 years.10 While HES has its peak incidence in the fourth decade of life, acute onset of new symptoms 3 months postpartum makes this an unusual presentation. In this unique case, it is important to highlight the role of the physiologic changes of pregnancy in inflammatory mediation. The physiologic changes that occur in pregnancy to ensure fetal tolerance can have profound implications for leukocyte count, AEC, and subsequent inflammatory responses. The phenomenon of inflammatory amelioration during pregnancy is well-documented, but there has only been 1 known published case report discussing decreasing HES symptoms during pregnancy with prepregnancy and postpartum hypereosinophilia.8 It is suggested that this amelioration is secondary to cortisol and progesterone shifts that occur in pregnancy. Physiologic increases in adrenocorticotropic hormone in pregnancy leads to subsequent secretion of endogenous steroids by the adrenal cortex. In turn, pregnancy can lead to leukocytosis and eosinopenia.8 Overall, pregnancy can have beneficial immunomodulating properties in the spectrum of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Even so, this patient with HES diagnosed postpartum remains at risk for the sequelae of hypereosinophilia, regardless of potential for AEC reduction during pregnancy. Therefore, treatment considerations need to be made with the safety of the maternal-fetal dyad as a priority.

Treatment

The treatment of symptomatic HES without acute life-threatening features or associated malignancy is generally determined by clinical variant.2-4 There is insufficient data to support initiation of treatment solely based on persistently elevated AEC. Patients with peripheral eosinophilia and hypereosinophilia should be monitored periodically with appropriate subspecialist evaluation for occult end-organ involvement, and targeted therapies should be deferred until an HES diagnosis.1-4 First-line therapy in most HES variants is systemic glucocorticoids.2,3,7 Since the disease course for this patient did not precisely match an HES variant, it was challenging to ascertain the optimal personalized treatment regimen. The approach to therapy was further complicated by newly identified pregnancy necessitating cessation of systemic glucocorticoids. In addition to glucocorticoids, hydroxyurea and interferon-α are among treatments historically used for HES, with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5 becoming more common.1-4 Although this patient may ultimately benefit from an IL-5 targeting biologic medication such as mepolizumab, safety in pregnancy is not well-studied and may require close clinical monitoring with treatment deferred until after delivery if possible.3,7,8,11

Military service members with frequent geographic relocation have additional barriers to timely diagnosis with often-limited access to subspecialty care depending on the duty station. While the patient was able to receive care at a large military medical center with many subspecialists, prompt recognition and timely referral to specialists would be even more critical at a smaller treatment facility. Depending on the severity and variant of HES, patients may warrant evaluation and treatment by hematology/oncology, cardiology, pulmonology, and immunology. Although HES can present in young children and older adults, this condition is most often diagnosed during the third and fourth decades of life, putting clinicians on the front line of hypereosinophilia identification and evaluation.10 Military physicians have the additional duty to not only think ahead in their diverse clinical settings to ensure proper care for patients, but also maintain a broad differential inclusive of more rare disease processes such as HES.

CONCLUSIONS

This case emphasizes how uncontrolled or untreated HES can lead to significant end-organ damage involving multiple systems and high morbidity. Prompt recognition of hypereosinophilia with potential HES can help expedite coordination of multidisciplinary care across multiple specialties to minimize delays in diagnosis and treatment. Doing so may minimize associated morbidity and mortality, especially in individuals located at more remote duty stations or deployed to austere environments.

- Cogan E, Roufosse F. Clinical management of the hypereosinophilic syndromes. Expert Rev Hematol. 2012;5:275-290. doi: 10.1586/ehm.12.14

- Klion A. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: approach to treatment in the era of precision medicine. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2018;2018:326-331. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.326

- Shomali W, Gotlib J. World health organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2022 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2022;97:129-148. doi:10.1002/ajh.26352

- Helbig G, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilic syndromes - an enigmatic group of disorders with an intriguing clinical spectrum and challenging treatment. Blood Rev. 2021;49:100809. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2021.100809

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, et al. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:607-612.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.019

- Roufosse FE, Goldman M, Cogan E. Hypereosinophilic syndromes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:37. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-37

- Pitlick MM, Li JT, Pongdee T. Current and emerging biologic therapies targeting eosinophilic disorders. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15:100676. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2022.10067

- Ault P, Cortes J, Lynn A, Keating M, Verstovsek S. Pregnancy in a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Leuk Res. 2009;33:186-187. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2008.05.013

- Rioux JD, Stone VA, Daly MJ, et al. Familial eosinophilia maps to the cytokine gene cluster on human chromosomal region 5q31-q33. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1086-1094. doi:10.1086/302053

- Williams KW, Ware J, Abiodun A, et al. Hypereosinophilia in children and adults: a retrospective comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:941-947.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2016.03.020

- Pane F, Lefevre G, Kwon N, et al. Characterization of disease flares and impact of mepolizumab in patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Front Immunol. 2022;13:935996. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.935996

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is defined by marked, persistent absolute eosinophil count (AEC) > 1500 cells/μL on ≥ 2 peripheral smears separated by ≥ 1 month with evidence of accompanied end-organ damage, in the absence of other causes of eosinophilia such as malignancy, atopy, or parasitic infections.1-5 Hypereosinophilic infiltration can impact almost every organ system; however, the most profound complications in patients with HES are related to leukemias and cardiac manifestations of the disease.3,4 Although rare, the associated morbidity and mortality of HES are considerable, making prompt recognition and treatment essential. Management involves targeted therapy based on pathologic classification of HES and on decreasing associated inflammation, fibrosis, and end-organ damage.3,5-7

The patient in this case report met the diagnostic criteria for HES. However, this patient had several clinical and laboratory features that made it difficult to characterize a specific HES variant. Moreover, she had additional immunomodulating factors in the setting of pregnancy. This is the first documented case of HES of undetermined etiology diagnosed postpartum and managed in the setting of a new pregnancy.2,8

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year-old female active-duty military service member with allergic rhinitis and a history of childhood eczema was referred to allergy/immunology for evaluation of a new, progressive pruritic rash. Symptoms started 3 months after the birth of her first child, with a new diffuse erythematous skin rash sparing her palms, soles, and mucosal surfaces. Given her history of atopy, the rash was initially treated as severe atopic dermatitis with appropriate topical medications. The rash gradually worsened, with the development of intermittent facial swelling, night sweats, dyspnea, recurrent epigastric abdominal pain, and nausea with vomiting, resulting in decreased oral intake and weight loss.

The patient was hospitalized and received an expedited multidisciplinary evaluation by dermatology, hematology/oncology, and gastroenterology. Her AEC of 4787 cells/μL peaked on admission and was markedly elevated from the 1070 cells/μL reported in the third trimester of her pregnancy. She was found to have mature eosinophilia on skin biopsy (Figure 1), endoscopic duodenal biopsy (Figure 2), peripheral blood smear (Figure 3), and bone marrow biopsy (Figure 4).

Radiographic imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed hepatomegaly without detectable neoplasm. There was no clinical evidence of cardiac involvement, and evaluation with electrocardiography and echocardiography did not indicate myocarditis. Extensive laboratory testing revealed no genetic mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants of HES.

The patient received topical emollients, omeprazole 40 mg daily, and ondansetron 8 mg 3 times daily as needed for symptom management, and was started on oral prednisone 40 mg daily with improvement in dyspnea, night sweats, and gastrointestinal complaints. During the patient's 6-day hospitalization and treatment, her AECs gradually decreased to 2110 cells/μL, and decreased to 1600 cells/μL over the course of a month, remaining in the hypereosinophilic range. The patient was discovered to be pregnant while symptoms were improving, resulting in stepwise discontinuation of oral steroids, but she reported continued improvement in symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Peripheral eosinophilia has a broad differential diagnoses, including HES, parasitic infections, atopic hypersensitivity diseases, eosinophilic lung diseases, eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, vasculitides such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, genetic syndromes predisposing to eosinophilia, episodic angioedema with eosinophilia, and chronic metabolic disease with adrenal insufficiency.1-5 HES, although rare, is a disease process with potentially devastating associated morbidity and mortality if not promptly recognized and treated. HES is further delineated by hypereosinophilia with associated eosinophil-mediated organ damage or dysfunction.3-5

Clinical manifestations of HES can differ greatly depending on the HES variant and degree of organ involvement at the time of diagnosis and throughout the disease course. Patients with HES, as well as those with asymptomatic eosinophilia or hypereosinophilia, should be closely monitored for disease progression. In addition to trending peripheral AECs, clinicians should screen for symptoms of organ involvement and perform targeted evaluation of the suspected organs to promptly identify early signs of organ involvement and initiate treatment.1-4 Recommendations regarding screening intervals vary widely from monthly to annually, depending on a patient’s specific clinical picture.

HES has been subdivided into clinically relevant variants, including myeloproliferative (M-HES), T lymphocytic (L-HES), organ-restricted (or overlap) HES, familial HES, idiopathic HES, and specific syndromes with associated hypereosinophilia.3-5,9 Patients with M-HES have elevated circulating leukocyte precursors and clinical manifestations, including but not limited to hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. The most commonly associated genetic mutations include the FIP1L1-PDGFR-α fusion, BCR-ABL1, PDGFRA/B, JAK2, KIT, and FGFR1.3-6 L-HES usually has predominant skin and soft tissue involvement secondary to immunoglobulin E-mediated actions with clonal expansion of T cells (most commonly CD3-4+ or CD3+CD4-CD8-).3,5,6 Familial HES, a rare variant, follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and is usually present at birth. It involves chromosome 5, which contains genes coding for cytokines that drive eosinophilic proliferation, including interleukin (IL)-3, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.5,9 Hypereosinophilia in the setting of end-organ damage restricted to a single organ is considered organ-restricted HES. There can be significant hepatic and gastrointestinal dysfunction, with or without malabsorption.

HES can also manifest with hematologic malignancy, restrictive obliterative cardiomyopathies, renal injury manifested by hematuria and electrolyte derangements, and neurologic complications including hemiparesis, dysarthria, and even coma.6 Endothelial damage due to eosinophil-driven inflammation can result in thrombus formation and increased risk of thromboembolic events in various organs.3 Idiopathic HES, otherwise known as HES of unknown etiology or significance, is a diagnosis of exclusion and constitutes a cohort of patients who do not fit into the other delineated categories.3-5 These patients often have multisystem involvement, making classification and treatment a challenge.5

The patient described in this case met the diagnostic criteria for HES, but her complicated clinical and laboratory features were challenging to characterize into a specific variant of HES. Organ-restricted HES was ruled out due to skin, marrow, and duodenal infiltration. She also had the potential for lung involvement based on her clinical symptoms, however no biopsy was obtained. Laboratory testing revealed no deletions or mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants. Her multisystem involvement without an underlying associated syndrome suggests idiopathic HES or HES of undetermined significance.1-5

Most patients with HES are diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50 years.10 While HES has its peak incidence in the fourth decade of life, acute onset of new symptoms 3 months postpartum makes this an unusual presentation. In this unique case, it is important to highlight the role of the physiologic changes of pregnancy in inflammatory mediation. The physiologic changes that occur in pregnancy to ensure fetal tolerance can have profound implications for leukocyte count, AEC, and subsequent inflammatory responses. The phenomenon of inflammatory amelioration during pregnancy is well-documented, but there has only been 1 known published case report discussing decreasing HES symptoms during pregnancy with prepregnancy and postpartum hypereosinophilia.8 It is suggested that this amelioration is secondary to cortisol and progesterone shifts that occur in pregnancy. Physiologic increases in adrenocorticotropic hormone in pregnancy leads to subsequent secretion of endogenous steroids by the adrenal cortex. In turn, pregnancy can lead to leukocytosis and eosinopenia.8 Overall, pregnancy can have beneficial immunomodulating properties in the spectrum of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Even so, this patient with HES diagnosed postpartum remains at risk for the sequelae of hypereosinophilia, regardless of potential for AEC reduction during pregnancy. Therefore, treatment considerations need to be made with the safety of the maternal-fetal dyad as a priority.

Treatment

The treatment of symptomatic HES without acute life-threatening features or associated malignancy is generally determined by clinical variant.2-4 There is insufficient data to support initiation of treatment solely based on persistently elevated AEC. Patients with peripheral eosinophilia and hypereosinophilia should be monitored periodically with appropriate subspecialist evaluation for occult end-organ involvement, and targeted therapies should be deferred until an HES diagnosis.1-4 First-line therapy in most HES variants is systemic glucocorticoids.2,3,7 Since the disease course for this patient did not precisely match an HES variant, it was challenging to ascertain the optimal personalized treatment regimen. The approach to therapy was further complicated by newly identified pregnancy necessitating cessation of systemic glucocorticoids. In addition to glucocorticoids, hydroxyurea and interferon-α are among treatments historically used for HES, with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5 becoming more common.1-4 Although this patient may ultimately benefit from an IL-5 targeting biologic medication such as mepolizumab, safety in pregnancy is not well-studied and may require close clinical monitoring with treatment deferred until after delivery if possible.3,7,8,11

Military service members with frequent geographic relocation have additional barriers to timely diagnosis with often-limited access to subspecialty care depending on the duty station. While the patient was able to receive care at a large military medical center with many subspecialists, prompt recognition and timely referral to specialists would be even more critical at a smaller treatment facility. Depending on the severity and variant of HES, patients may warrant evaluation and treatment by hematology/oncology, cardiology, pulmonology, and immunology. Although HES can present in young children and older adults, this condition is most often diagnosed during the third and fourth decades of life, putting clinicians on the front line of hypereosinophilia identification and evaluation.10 Military physicians have the additional duty to not only think ahead in their diverse clinical settings to ensure proper care for patients, but also maintain a broad differential inclusive of more rare disease processes such as HES.

CONCLUSIONS

This case emphasizes how uncontrolled or untreated HES can lead to significant end-organ damage involving multiple systems and high morbidity. Prompt recognition of hypereosinophilia with potential HES can help expedite coordination of multidisciplinary care across multiple specialties to minimize delays in diagnosis and treatment. Doing so may minimize associated morbidity and mortality, especially in individuals located at more remote duty stations or deployed to austere environments.

Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is defined by marked, persistent absolute eosinophil count (AEC) > 1500 cells/μL on ≥ 2 peripheral smears separated by ≥ 1 month with evidence of accompanied end-organ damage, in the absence of other causes of eosinophilia such as malignancy, atopy, or parasitic infections.1-5 Hypereosinophilic infiltration can impact almost every organ system; however, the most profound complications in patients with HES are related to leukemias and cardiac manifestations of the disease.3,4 Although rare, the associated morbidity and mortality of HES are considerable, making prompt recognition and treatment essential. Management involves targeted therapy based on pathologic classification of HES and on decreasing associated inflammation, fibrosis, and end-organ damage.3,5-7

The patient in this case report met the diagnostic criteria for HES. However, this patient had several clinical and laboratory features that made it difficult to characterize a specific HES variant. Moreover, she had additional immunomodulating factors in the setting of pregnancy. This is the first documented case of HES of undetermined etiology diagnosed postpartum and managed in the setting of a new pregnancy.2,8

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year-old female active-duty military service member with allergic rhinitis and a history of childhood eczema was referred to allergy/immunology for evaluation of a new, progressive pruritic rash. Symptoms started 3 months after the birth of her first child, with a new diffuse erythematous skin rash sparing her palms, soles, and mucosal surfaces. Given her history of atopy, the rash was initially treated as severe atopic dermatitis with appropriate topical medications. The rash gradually worsened, with the development of intermittent facial swelling, night sweats, dyspnea, recurrent epigastric abdominal pain, and nausea with vomiting, resulting in decreased oral intake and weight loss.

The patient was hospitalized and received an expedited multidisciplinary evaluation by dermatology, hematology/oncology, and gastroenterology. Her AEC of 4787 cells/μL peaked on admission and was markedly elevated from the 1070 cells/μL reported in the third trimester of her pregnancy. She was found to have mature eosinophilia on skin biopsy (Figure 1), endoscopic duodenal biopsy (Figure 2), peripheral blood smear (Figure 3), and bone marrow biopsy (Figure 4).

Radiographic imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed hepatomegaly without detectable neoplasm. There was no clinical evidence of cardiac involvement, and evaluation with electrocardiography and echocardiography did not indicate myocarditis. Extensive laboratory testing revealed no genetic mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants of HES.

The patient received topical emollients, omeprazole 40 mg daily, and ondansetron 8 mg 3 times daily as needed for symptom management, and was started on oral prednisone 40 mg daily with improvement in dyspnea, night sweats, and gastrointestinal complaints. During the patient's 6-day hospitalization and treatment, her AECs gradually decreased to 2110 cells/μL, and decreased to 1600 cells/μL over the course of a month, remaining in the hypereosinophilic range. The patient was discovered to be pregnant while symptoms were improving, resulting in stepwise discontinuation of oral steroids, but she reported continued improvement in symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Peripheral eosinophilia has a broad differential diagnoses, including HES, parasitic infections, atopic hypersensitivity diseases, eosinophilic lung diseases, eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases, vasculitides such as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, genetic syndromes predisposing to eosinophilia, episodic angioedema with eosinophilia, and chronic metabolic disease with adrenal insufficiency.1-5 HES, although rare, is a disease process with potentially devastating associated morbidity and mortality if not promptly recognized and treated. HES is further delineated by hypereosinophilia with associated eosinophil-mediated organ damage or dysfunction.3-5

Clinical manifestations of HES can differ greatly depending on the HES variant and degree of organ involvement at the time of diagnosis and throughout the disease course. Patients with HES, as well as those with asymptomatic eosinophilia or hypereosinophilia, should be closely monitored for disease progression. In addition to trending peripheral AECs, clinicians should screen for symptoms of organ involvement and perform targeted evaluation of the suspected organs to promptly identify early signs of organ involvement and initiate treatment.1-4 Recommendations regarding screening intervals vary widely from monthly to annually, depending on a patient’s specific clinical picture.

HES has been subdivided into clinically relevant variants, including myeloproliferative (M-HES), T lymphocytic (L-HES), organ-restricted (or overlap) HES, familial HES, idiopathic HES, and specific syndromes with associated hypereosinophilia.3-5,9 Patients with M-HES have elevated circulating leukocyte precursors and clinical manifestations, including but not limited to hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. The most commonly associated genetic mutations include the FIP1L1-PDGFR-α fusion, BCR-ABL1, PDGFRA/B, JAK2, KIT, and FGFR1.3-6 L-HES usually has predominant skin and soft tissue involvement secondary to immunoglobulin E-mediated actions with clonal expansion of T cells (most commonly CD3-4+ or CD3+CD4-CD8-).3,5,6 Familial HES, a rare variant, follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and is usually present at birth. It involves chromosome 5, which contains genes coding for cytokines that drive eosinophilic proliferation, including interleukin (IL)-3, IL-5, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.5,9 Hypereosinophilia in the setting of end-organ damage restricted to a single organ is considered organ-restricted HES. There can be significant hepatic and gastrointestinal dysfunction, with or without malabsorption.

HES can also manifest with hematologic malignancy, restrictive obliterative cardiomyopathies, renal injury manifested by hematuria and electrolyte derangements, and neurologic complications including hemiparesis, dysarthria, and even coma.6 Endothelial damage due to eosinophil-driven inflammation can result in thrombus formation and increased risk of thromboembolic events in various organs.3 Idiopathic HES, otherwise known as HES of unknown etiology or significance, is a diagnosis of exclusion and constitutes a cohort of patients who do not fit into the other delineated categories.3-5 These patients often have multisystem involvement, making classification and treatment a challenge.5

The patient described in this case met the diagnostic criteria for HES, but her complicated clinical and laboratory features were challenging to characterize into a specific variant of HES. Organ-restricted HES was ruled out due to skin, marrow, and duodenal infiltration. She also had the potential for lung involvement based on her clinical symptoms, however no biopsy was obtained. Laboratory testing revealed no deletions or mutations indicative of familial, myeloproliferative, or lymphocytic variants. Her multisystem involvement without an underlying associated syndrome suggests idiopathic HES or HES of undetermined significance.1-5

Most patients with HES are diagnosed between the ages of 20 and 50 years.10 While HES has its peak incidence in the fourth decade of life, acute onset of new symptoms 3 months postpartum makes this an unusual presentation. In this unique case, it is important to highlight the role of the physiologic changes of pregnancy in inflammatory mediation. The physiologic changes that occur in pregnancy to ensure fetal tolerance can have profound implications for leukocyte count, AEC, and subsequent inflammatory responses. The phenomenon of inflammatory amelioration during pregnancy is well-documented, but there has only been 1 known published case report discussing decreasing HES symptoms during pregnancy with prepregnancy and postpartum hypereosinophilia.8 It is suggested that this amelioration is secondary to cortisol and progesterone shifts that occur in pregnancy. Physiologic increases in adrenocorticotropic hormone in pregnancy leads to subsequent secretion of endogenous steroids by the adrenal cortex. In turn, pregnancy can lead to leukocytosis and eosinopenia.8 Overall, pregnancy can have beneficial immunomodulating properties in the spectrum of hypereosinophilic syndromes. Even so, this patient with HES diagnosed postpartum remains at risk for the sequelae of hypereosinophilia, regardless of potential for AEC reduction during pregnancy. Therefore, treatment considerations need to be made with the safety of the maternal-fetal dyad as a priority.

Treatment

The treatment of symptomatic HES without acute life-threatening features or associated malignancy is generally determined by clinical variant.2-4 There is insufficient data to support initiation of treatment solely based on persistently elevated AEC. Patients with peripheral eosinophilia and hypereosinophilia should be monitored periodically with appropriate subspecialist evaluation for occult end-organ involvement, and targeted therapies should be deferred until an HES diagnosis.1-4 First-line therapy in most HES variants is systemic glucocorticoids.2,3,7 Since the disease course for this patient did not precisely match an HES variant, it was challenging to ascertain the optimal personalized treatment regimen. The approach to therapy was further complicated by newly identified pregnancy necessitating cessation of systemic glucocorticoids. In addition to glucocorticoids, hydroxyurea and interferon-α are among treatments historically used for HES, with tyrosine kinase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5 becoming more common.1-4 Although this patient may ultimately benefit from an IL-5 targeting biologic medication such as mepolizumab, safety in pregnancy is not well-studied and may require close clinical monitoring with treatment deferred until after delivery if possible.3,7,8,11

Military service members with frequent geographic relocation have additional barriers to timely diagnosis with often-limited access to subspecialty care depending on the duty station. While the patient was able to receive care at a large military medical center with many subspecialists, prompt recognition and timely referral to specialists would be even more critical at a smaller treatment facility. Depending on the severity and variant of HES, patients may warrant evaluation and treatment by hematology/oncology, cardiology, pulmonology, and immunology. Although HES can present in young children and older adults, this condition is most often diagnosed during the third and fourth decades of life, putting clinicians on the front line of hypereosinophilia identification and evaluation.10 Military physicians have the additional duty to not only think ahead in their diverse clinical settings to ensure proper care for patients, but also maintain a broad differential inclusive of more rare disease processes such as HES.

CONCLUSIONS

This case emphasizes how uncontrolled or untreated HES can lead to significant end-organ damage involving multiple systems and high morbidity. Prompt recognition of hypereosinophilia with potential HES can help expedite coordination of multidisciplinary care across multiple specialties to minimize delays in diagnosis and treatment. Doing so may minimize associated morbidity and mortality, especially in individuals located at more remote duty stations or deployed to austere environments.

- Cogan E, Roufosse F. Clinical management of the hypereosinophilic syndromes. Expert Rev Hematol. 2012;5:275-290. doi: 10.1586/ehm.12.14

- Klion A. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: approach to treatment in the era of precision medicine. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2018;2018:326-331. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.326

- Shomali W, Gotlib J. World health organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2022 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2022;97:129-148. doi:10.1002/ajh.26352

- Helbig G, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilic syndromes - an enigmatic group of disorders with an intriguing clinical spectrum and challenging treatment. Blood Rev. 2021;49:100809. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2021.100809

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, et al. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:607-612.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.019

- Roufosse FE, Goldman M, Cogan E. Hypereosinophilic syndromes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:37. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-37

- Pitlick MM, Li JT, Pongdee T. Current and emerging biologic therapies targeting eosinophilic disorders. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15:100676. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2022.10067

- Ault P, Cortes J, Lynn A, Keating M, Verstovsek S. Pregnancy in a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Leuk Res. 2009;33:186-187. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2008.05.013

- Rioux JD, Stone VA, Daly MJ, et al. Familial eosinophilia maps to the cytokine gene cluster on human chromosomal region 5q31-q33. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1086-1094. doi:10.1086/302053

- Williams KW, Ware J, Abiodun A, et al. Hypereosinophilia in children and adults: a retrospective comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:941-947.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2016.03.020

- Pane F, Lefevre G, Kwon N, et al. Characterization of disease flares and impact of mepolizumab in patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Front Immunol. 2022;13:935996. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.935996

- Cogan E, Roufosse F. Clinical management of the hypereosinophilic syndromes. Expert Rev Hematol. 2012;5:275-290. doi: 10.1586/ehm.12.14

- Klion A. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: approach to treatment in the era of precision medicine. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2018;2018:326-331. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2018.1.326

- Shomali W, Gotlib J. World health organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2022 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2022;97:129-148. doi:10.1002/ajh.26352

- Helbig G, Klion AD. Hypereosinophilic syndromes - an enigmatic group of disorders with an intriguing clinical spectrum and challenging treatment. Blood Rev. 2021;49:100809. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2021.100809

- Valent P, Klion AD, Horny HP, et al. Contemporary consensus proposal on criteria and classification of eosinophilic disorders and related syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:607-612.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.019

- Roufosse FE, Goldman M, Cogan E. Hypereosinophilic syndromes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:37. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-37

- Pitlick MM, Li JT, Pongdee T. Current and emerging biologic therapies targeting eosinophilic disorders. World Allergy Organ J. 2022;15:100676. doi:10.1016/j.waojou.2022.10067

- Ault P, Cortes J, Lynn A, Keating M, Verstovsek S. Pregnancy in a patient with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Leuk Res. 2009;33:186-187. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2008.05.013

- Rioux JD, Stone VA, Daly MJ, et al. Familial eosinophilia maps to the cytokine gene cluster on human chromosomal region 5q31-q33. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1086-1094. doi:10.1086/302053

- Williams KW, Ware J, Abiodun A, et al. Hypereosinophilia in children and adults: a retrospective comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:941-947.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2016.03.020

- Pane F, Lefevre G, Kwon N, et al. Characterization of disease flares and impact of mepolizumab in patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome. Front Immunol. 2022;13:935996. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.935996

Unique Presentation of Postpartum Hypereosinophilic Syndrome With Atypical Features and Therapeutic Challenges

Unique Presentation of Postpartum Hypereosinophilic Syndrome With Atypical Features and Therapeutic Challenges

Hematology and Oncology Staffing Levels for Fiscal Years 19–24

Background

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) faces a landscape of increasingly complex practice, especially in Hematology/Oncology (H/O), and a nationwide shortage of healthcare providers, while serving more Veterans than ever before. To understand current and future staffing needs, the VA National Oncology Program performed an assessment of H/O staffing, including attending physicians, residents/ fellows, licensed independent practitioners (LIPs) (nurse practitioners/physician assistants), and nurses for fiscal years (FY) 19–24.

Methods

Using VA Corporate Data Warehouse, we identified H/O visits in VA from 10/01/2018 through 09/30/2024 using stop codes. No-show (< 0.00001%) and National TeleOncology appointments (1%) were removed. We retrieved all notes associated with resulting visits and used area-ofspecialization and provider-type data to identify all attending physicians, trainees, LIPs, and nurses who authored or cosigned these notes. We identified H/O staff as 1. those associated with H/O clinic locations, 2. physicians who consistently cosigned H/O notes authored by fellows and LIPs associated with H/O locations, 3. fellows and LIPs authoring notes that were then cosigned by H/O physicians, and 4. nurses authoring notes associated with H/O visits.

Analysis

For each FY, we obtained total numbers of visits, unique patients, and care-providing staff by type. For validation, collaborating providers at several sites reviewed visit information, and a colleague also performed an independent, parallel data extraction. We adjusted FY totals to account for the growing patient population by dividing unique staff count by number of unique patients and multiplying by 200,000 (the approximate number of unique patients in FY19).

Results

From FY19 through FY24, VA Hematology/ Oncology saw a 14.6% rise in unique patients (from 232,084 to 265,926) and a 15.4% rise in visits (from 923,175 to 1,065,186). The absolute number of attendings rose by 4 (0.6%); of LIPs, by 138 (14.4%); and of nurses, by 142 (4.9%); trainees fell by 102 (4.3%). Adjusted to 200,000 patients, the number of attendings fell by 76 (12.3%); LIPs, by 1 (0.1%); trainees, by 335 (16.5%); and nurses, by 211 (8.4%).

Conclusions

Adjusted to number of Veterans, there are 10.4% fewer staff in Hematology/Oncology in FY24 compared to FY19.

Background

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) faces a landscape of increasingly complex practice, especially in Hematology/Oncology (H/O), and a nationwide shortage of healthcare providers, while serving more Veterans than ever before. To understand current and future staffing needs, the VA National Oncology Program performed an assessment of H/O staffing, including attending physicians, residents/ fellows, licensed independent practitioners (LIPs) (nurse practitioners/physician assistants), and nurses for fiscal years (FY) 19–24.

Methods

Using VA Corporate Data Warehouse, we identified H/O visits in VA from 10/01/2018 through 09/30/2024 using stop codes. No-show (< 0.00001%) and National TeleOncology appointments (1%) were removed. We retrieved all notes associated with resulting visits and used area-ofspecialization and provider-type data to identify all attending physicians, trainees, LIPs, and nurses who authored or cosigned these notes. We identified H/O staff as 1. those associated with H/O clinic locations, 2. physicians who consistently cosigned H/O notes authored by fellows and LIPs associated with H/O locations, 3. fellows and LIPs authoring notes that were then cosigned by H/O physicians, and 4. nurses authoring notes associated with H/O visits.

Analysis

For each FY, we obtained total numbers of visits, unique patients, and care-providing staff by type. For validation, collaborating providers at several sites reviewed visit information, and a colleague also performed an independent, parallel data extraction. We adjusted FY totals to account for the growing patient population by dividing unique staff count by number of unique patients and multiplying by 200,000 (the approximate number of unique patients in FY19).

Results

From FY19 through FY24, VA Hematology/ Oncology saw a 14.6% rise in unique patients (from 232,084 to 265,926) and a 15.4% rise in visits (from 923,175 to 1,065,186). The absolute number of attendings rose by 4 (0.6%); of LIPs, by 138 (14.4%); and of nurses, by 142 (4.9%); trainees fell by 102 (4.3%). Adjusted to 200,000 patients, the number of attendings fell by 76 (12.3%); LIPs, by 1 (0.1%); trainees, by 335 (16.5%); and nurses, by 211 (8.4%).

Conclusions

Adjusted to number of Veterans, there are 10.4% fewer staff in Hematology/Oncology in FY24 compared to FY19.

Background

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) faces a landscape of increasingly complex practice, especially in Hematology/Oncology (H/O), and a nationwide shortage of healthcare providers, while serving more Veterans than ever before. To understand current and future staffing needs, the VA National Oncology Program performed an assessment of H/O staffing, including attending physicians, residents/ fellows, licensed independent practitioners (LIPs) (nurse practitioners/physician assistants), and nurses for fiscal years (FY) 19–24.

Methods

Using VA Corporate Data Warehouse, we identified H/O visits in VA from 10/01/2018 through 09/30/2024 using stop codes. No-show (< 0.00001%) and National TeleOncology appointments (1%) were removed. We retrieved all notes associated with resulting visits and used area-ofspecialization and provider-type data to identify all attending physicians, trainees, LIPs, and nurses who authored or cosigned these notes. We identified H/O staff as 1. those associated with H/O clinic locations, 2. physicians who consistently cosigned H/O notes authored by fellows and LIPs associated with H/O locations, 3. fellows and LIPs authoring notes that were then cosigned by H/O physicians, and 4. nurses authoring notes associated with H/O visits.

Analysis

For each FY, we obtained total numbers of visits, unique patients, and care-providing staff by type. For validation, collaborating providers at several sites reviewed visit information, and a colleague also performed an independent, parallel data extraction. We adjusted FY totals to account for the growing patient population by dividing unique staff count by number of unique patients and multiplying by 200,000 (the approximate number of unique patients in FY19).

Results

From FY19 through FY24, VA Hematology/ Oncology saw a 14.6% rise in unique patients (from 232,084 to 265,926) and a 15.4% rise in visits (from 923,175 to 1,065,186). The absolute number of attendings rose by 4 (0.6%); of LIPs, by 138 (14.4%); and of nurses, by 142 (4.9%); trainees fell by 102 (4.3%). Adjusted to 200,000 patients, the number of attendings fell by 76 (12.3%); LIPs, by 1 (0.1%); trainees, by 335 (16.5%); and nurses, by 211 (8.4%).

Conclusions

Adjusted to number of Veterans, there are 10.4% fewer staff in Hematology/Oncology in FY24 compared to FY19.

Enhancing Coding Accuracy at the Hematology/Oncology Clinic: Is It Time to Hire a Dedicated Coder?

Background

Accurate clinical coding that reflects all diagnoses and problems addressed during a patient encounter is essential for the cancer program’s data quality, research initiatives, and securing VERA (Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation) funding. However, providers often face barriers such as limited time during patient visits and difficulty navigating Electronic health record (EHR) systems. These challenges lead to inaccurate coding, which undermines downstream data integrity. This quality improvement (QI) study aimed to identify these barriers and implement an intervention to improve coding accuracy, while also assessing the financial implications of improved documentation.

Methods

This QI study was conducted at the Albany Stratton VA Medical Center, focusing on hematology/ oncology outpatient encounters. A baseline chart audit of diagnosis codes from June 2023 revealed an accuracy rate of 69.8%. To address this, an intervention was implemented in which dedicated coders were assigned to support attending physicians in coding for over a two-week period. These coders reviewed and corrected diagnosis codes in real-time. A follow-up audit conducted after the intervention showed an improved coding accuracy of 82%.

Discussion/Implications

Coding remains a timeconsuming task for providers, made more difficult by EHR systems that are not user-friendly. This study demonstrated that involving dedicated coders significantly improves documentation accuracy—from 69% to 82%. In addition to data quality, the financial benefits are notable. A projected annual return on investment of $216,094 was calculated, based on an internal analysis showing that in a sample of 124 patients, 10% could have qualified for higher VERA funding based on accurate coding, generating an estimated $17,427 in additional reimbursement per patient. This cost-benefit ratio supports the recommendation to staff dedicated coders. Other interventions were also utilised, such as updating the national encounter form and auto-populating documentation in Dragon software, but had limited impact and did not directly address diagnosis accuracy respectively.

Conclusions

Targeted interventions improved coding accuracy, but sustainability remains a challenge due to time and system limitations. Future efforts should focus on hiring full-time coders. These steps can further enhance coding quality and potentially increase hospital revenue.

Background

Accurate clinical coding that reflects all diagnoses and problems addressed during a patient encounter is essential for the cancer program’s data quality, research initiatives, and securing VERA (Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation) funding. However, providers often face barriers such as limited time during patient visits and difficulty navigating Electronic health record (EHR) systems. These challenges lead to inaccurate coding, which undermines downstream data integrity. This quality improvement (QI) study aimed to identify these barriers and implement an intervention to improve coding accuracy, while also assessing the financial implications of improved documentation.

Methods

This QI study was conducted at the Albany Stratton VA Medical Center, focusing on hematology/ oncology outpatient encounters. A baseline chart audit of diagnosis codes from June 2023 revealed an accuracy rate of 69.8%. To address this, an intervention was implemented in which dedicated coders were assigned to support attending physicians in coding for over a two-week period. These coders reviewed and corrected diagnosis codes in real-time. A follow-up audit conducted after the intervention showed an improved coding accuracy of 82%.

Discussion/Implications

Coding remains a timeconsuming task for providers, made more difficult by EHR systems that are not user-friendly. This study demonstrated that involving dedicated coders significantly improves documentation accuracy—from 69% to 82%. In addition to data quality, the financial benefits are notable. A projected annual return on investment of $216,094 was calculated, based on an internal analysis showing that in a sample of 124 patients, 10% could have qualified for higher VERA funding based on accurate coding, generating an estimated $17,427 in additional reimbursement per patient. This cost-benefit ratio supports the recommendation to staff dedicated coders. Other interventions were also utilised, such as updating the national encounter form and auto-populating documentation in Dragon software, but had limited impact and did not directly address diagnosis accuracy respectively.

Conclusions

Targeted interventions improved coding accuracy, but sustainability remains a challenge due to time and system limitations. Future efforts should focus on hiring full-time coders. These steps can further enhance coding quality and potentially increase hospital revenue.

Background

Accurate clinical coding that reflects all diagnoses and problems addressed during a patient encounter is essential for the cancer program’s data quality, research initiatives, and securing VERA (Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation) funding. However, providers often face barriers such as limited time during patient visits and difficulty navigating Electronic health record (EHR) systems. These challenges lead to inaccurate coding, which undermines downstream data integrity. This quality improvement (QI) study aimed to identify these barriers and implement an intervention to improve coding accuracy, while also assessing the financial implications of improved documentation.

Methods

This QI study was conducted at the Albany Stratton VA Medical Center, focusing on hematology/ oncology outpatient encounters. A baseline chart audit of diagnosis codes from June 2023 revealed an accuracy rate of 69.8%. To address this, an intervention was implemented in which dedicated coders were assigned to support attending physicians in coding for over a two-week period. These coders reviewed and corrected diagnosis codes in real-time. A follow-up audit conducted after the intervention showed an improved coding accuracy of 82%.

Discussion/Implications

Coding remains a timeconsuming task for providers, made more difficult by EHR systems that are not user-friendly. This study demonstrated that involving dedicated coders significantly improves documentation accuracy—from 69% to 82%. In addition to data quality, the financial benefits are notable. A projected annual return on investment of $216,094 was calculated, based on an internal analysis showing that in a sample of 124 patients, 10% could have qualified for higher VERA funding based on accurate coding, generating an estimated $17,427 in additional reimbursement per patient. This cost-benefit ratio supports the recommendation to staff dedicated coders. Other interventions were also utilised, such as updating the national encounter form and auto-populating documentation in Dragon software, but had limited impact and did not directly address diagnosis accuracy respectively.

Conclusions

Targeted interventions improved coding accuracy, but sustainability remains a challenge due to time and system limitations. Future efforts should focus on hiring full-time coders. These steps can further enhance coding quality and potentially increase hospital revenue.

Evaluating the Implementation of 60-minute Iron Dextran Infusions at a Rural Health Center

Background

Due to risk for infusion-related reactions (IRR), administration of iron dextran requires an initial test dose with an extended monitoring period and subsequent doses given as a slow infusion over 2-3 hours. Safe use of a 60-minute iron dextran infusion protocol has been demonstrated previously at fully staffed academic teaching institutions. This study sought to determine the impact on patient safety and infusion clinic efficiency after implementing a 60-minute iron dextran administration protocol at a small, rural facility utilizing a decentralized clinical model.

Methods

This single-site, prospective, interventional study was conducted at a rural level 1C Veterans Affairs secondary care facility. The Hematology/Oncology clinic staffing includes one onsite clinical pharmacy practitioner (CPP) and advanced practice nurse. Remote providers complete patient encounters through video and telehealth modalities. A 60-minute iron dextran infusion service line agreement was designed by the Hematology/Oncology CPP and approved by the facility prior to data collection. The protocol included administration of a test dose and 15-minute monitoring period for treatment naïve patients. Pre-medications were allowed at the discretion of the ordering providers. All patients who received iron dextran between May 31, 2024 and April 14, 2025 per protocol were included in data analysis and results were stratified by treatment naïve and pre-treated patients. Outcomes included the proportion of patients experiencing any grade of IRR based on the Common Criteria for Adverse Events Version 5.0, and the average duration of administration. Descriptive statistics were used for safety and efficiency outcomes.

Results

Eighty patients received 103 iron dextran infusions and were included for analysis. Pre-medications were administered for 16 of the 103 (15.5%) included infusions. Two patients experienced grade 1 IRR (nausea) on 4 occasions (3.8%) which quickly resolved with intravenous ondansetron, and full iron dextran doses were received. The mean infusion time was 94 minutes in the treatment naïve cohort vs 71 minutes in the pre-treated cohort.

Conclusions

This study suggests a Hematology/ Oncology CPP developed iron dextran 60-minute infusion protocol may be safely and efficiently administered for qualifying patients in a decentralized, rural healthcare setting.

Background

Due to risk for infusion-related reactions (IRR), administration of iron dextran requires an initial test dose with an extended monitoring period and subsequent doses given as a slow infusion over 2-3 hours. Safe use of a 60-minute iron dextran infusion protocol has been demonstrated previously at fully staffed academic teaching institutions. This study sought to determine the impact on patient safety and infusion clinic efficiency after implementing a 60-minute iron dextran administration protocol at a small, rural facility utilizing a decentralized clinical model.

Methods

This single-site, prospective, interventional study was conducted at a rural level 1C Veterans Affairs secondary care facility. The Hematology/Oncology clinic staffing includes one onsite clinical pharmacy practitioner (CPP) and advanced practice nurse. Remote providers complete patient encounters through video and telehealth modalities. A 60-minute iron dextran infusion service line agreement was designed by the Hematology/Oncology CPP and approved by the facility prior to data collection. The protocol included administration of a test dose and 15-minute monitoring period for treatment naïve patients. Pre-medications were allowed at the discretion of the ordering providers. All patients who received iron dextran between May 31, 2024 and April 14, 2025 per protocol were included in data analysis and results were stratified by treatment naïve and pre-treated patients. Outcomes included the proportion of patients experiencing any grade of IRR based on the Common Criteria for Adverse Events Version 5.0, and the average duration of administration. Descriptive statistics were used for safety and efficiency outcomes.

Results

Eighty patients received 103 iron dextran infusions and were included for analysis. Pre-medications were administered for 16 of the 103 (15.5%) included infusions. Two patients experienced grade 1 IRR (nausea) on 4 occasions (3.8%) which quickly resolved with intravenous ondansetron, and full iron dextran doses were received. The mean infusion time was 94 minutes in the treatment naïve cohort vs 71 minutes in the pre-treated cohort.

Conclusions

This study suggests a Hematology/ Oncology CPP developed iron dextran 60-minute infusion protocol may be safely and efficiently administered for qualifying patients in a decentralized, rural healthcare setting.

Background

Due to risk for infusion-related reactions (IRR), administration of iron dextran requires an initial test dose with an extended monitoring period and subsequent doses given as a slow infusion over 2-3 hours. Safe use of a 60-minute iron dextran infusion protocol has been demonstrated previously at fully staffed academic teaching institutions. This study sought to determine the impact on patient safety and infusion clinic efficiency after implementing a 60-minute iron dextran administration protocol at a small, rural facility utilizing a decentralized clinical model.

Methods

This single-site, prospective, interventional study was conducted at a rural level 1C Veterans Affairs secondary care facility. The Hematology/Oncology clinic staffing includes one onsite clinical pharmacy practitioner (CPP) and advanced practice nurse. Remote providers complete patient encounters through video and telehealth modalities. A 60-minute iron dextran infusion service line agreement was designed by the Hematology/Oncology CPP and approved by the facility prior to data collection. The protocol included administration of a test dose and 15-minute monitoring period for treatment naïve patients. Pre-medications were allowed at the discretion of the ordering providers. All patients who received iron dextran between May 31, 2024 and April 14, 2025 per protocol were included in data analysis and results were stratified by treatment naïve and pre-treated patients. Outcomes included the proportion of patients experiencing any grade of IRR based on the Common Criteria for Adverse Events Version 5.0, and the average duration of administration. Descriptive statistics were used for safety and efficiency outcomes.

Results

Eighty patients received 103 iron dextran infusions and were included for analysis. Pre-medications were administered for 16 of the 103 (15.5%) included infusions. Two patients experienced grade 1 IRR (nausea) on 4 occasions (3.8%) which quickly resolved with intravenous ondansetron, and full iron dextran doses were received. The mean infusion time was 94 minutes in the treatment naïve cohort vs 71 minutes in the pre-treated cohort.

Conclusions

This study suggests a Hematology/ Oncology CPP developed iron dextran 60-minute infusion protocol may be safely and efficiently administered for qualifying patients in a decentralized, rural healthcare setting.

Improving Palliative Care Referrals through Education of Hematology/Oncology Fellows: A QI Initiative

Purpose/Background

Palliative care referrals are recommended for patients with advanced or metastatic cancer to enhance patient and caregiver outcomes. However, challenges like delays or lack of referrals hinder implementation. This study identified rate of palliative care referrals at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida; explored potential barriers to referral, and implemented targeted interventions to improve referral rates and patient outcomes.

Methods

A Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle was used for this quality improvement project. Data was collected from electronic medical record, focusing on consult dates, patient demographics, and reasons for seeking palliative care. Pre-intervention surveys were administered to Hematology-Oncology fellows at the institution to identify barriers to referral. Following a root cause analysis, a targeted intervention was developed, focusing on educational programs for fellows for streamlined referral processes.

Results

Before the intervention, monthly average for palliative care consults was low (3-8, typically 5). Pre-intervention surveys revealed that fellows lacked knowledge about palliative care resources, which contributed to low referral rates. To address this issue, a didactic session led by a palliative care specialist was conducted for the fellows in the fellowship program. This session provided education on the role of palliative care, how to initiate referrals, and the benefits of early involvement of palliative care teams in oncology patient management. Post-intervention surveys showed a marked improvement in fellows’ confidence regarding identification of patients suitable for palliative care. Following the session, 90% (9/10) of fellows reported being “very likely” to consult palliative care more often and 80% (8/10) indicated they were “very likely” to initiate palliative care discussions earlier in patient’s disease trajectory, with the remaining 20% (2/10) reporting a neutral stance. All fellows (100%) agreed that earlier palliative care involvement improves patient outcomes.

Implications/Significance

This PDSA cycle demonstrated that targeted education for fellows can increase awareness of palliative care resources and improve referral rates. Future work will focus on reassessing usage of palliative care consults post-intervention to evaluate effects of fellows’ education of appropriate palliative care consultation, make necessary interventions based on data and further evaluate the long-term impact on patient outcomes at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.

Purpose/Background

Palliative care referrals are recommended for patients with advanced or metastatic cancer to enhance patient and caregiver outcomes. However, challenges like delays or lack of referrals hinder implementation. This study identified rate of palliative care referrals at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida; explored potential barriers to referral, and implemented targeted interventions to improve referral rates and patient outcomes.

Methods

A Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle was used for this quality improvement project. Data was collected from electronic medical record, focusing on consult dates, patient demographics, and reasons for seeking palliative care. Pre-intervention surveys were administered to Hematology-Oncology fellows at the institution to identify barriers to referral. Following a root cause analysis, a targeted intervention was developed, focusing on educational programs for fellows for streamlined referral processes.

Results

Before the intervention, monthly average for palliative care consults was low (3-8, typically 5). Pre-intervention surveys revealed that fellows lacked knowledge about palliative care resources, which contributed to low referral rates. To address this issue, a didactic session led by a palliative care specialist was conducted for the fellows in the fellowship program. This session provided education on the role of palliative care, how to initiate referrals, and the benefits of early involvement of palliative care teams in oncology patient management. Post-intervention surveys showed a marked improvement in fellows’ confidence regarding identification of patients suitable for palliative care. Following the session, 90% (9/10) of fellows reported being “very likely” to consult palliative care more often and 80% (8/10) indicated they were “very likely” to initiate palliative care discussions earlier in patient’s disease trajectory, with the remaining 20% (2/10) reporting a neutral stance. All fellows (100%) agreed that earlier palliative care involvement improves patient outcomes.

Implications/Significance

This PDSA cycle demonstrated that targeted education for fellows can increase awareness of palliative care resources and improve referral rates. Future work will focus on reassessing usage of palliative care consults post-intervention to evaluate effects of fellows’ education of appropriate palliative care consultation, make necessary interventions based on data and further evaluate the long-term impact on patient outcomes at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.

Purpose/Background

Palliative care referrals are recommended for patients with advanced or metastatic cancer to enhance patient and caregiver outcomes. However, challenges like delays or lack of referrals hinder implementation. This study identified rate of palliative care referrals at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida; explored potential barriers to referral, and implemented targeted interventions to improve referral rates and patient outcomes.

Methods

A Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle was used for this quality improvement project. Data was collected from electronic medical record, focusing on consult dates, patient demographics, and reasons for seeking palliative care. Pre-intervention surveys were administered to Hematology-Oncology fellows at the institution to identify barriers to referral. Following a root cause analysis, a targeted intervention was developed, focusing on educational programs for fellows for streamlined referral processes.

Results

Before the intervention, monthly average for palliative care consults was low (3-8, typically 5). Pre-intervention surveys revealed that fellows lacked knowledge about palliative care resources, which contributed to low referral rates. To address this issue, a didactic session led by a palliative care specialist was conducted for the fellows in the fellowship program. This session provided education on the role of palliative care, how to initiate referrals, and the benefits of early involvement of palliative care teams in oncology patient management. Post-intervention surveys showed a marked improvement in fellows’ confidence regarding identification of patients suitable for palliative care. Following the session, 90% (9/10) of fellows reported being “very likely” to consult palliative care more often and 80% (8/10) indicated they were “very likely” to initiate palliative care discussions earlier in patient’s disease trajectory, with the remaining 20% (2/10) reporting a neutral stance. All fellows (100%) agreed that earlier palliative care involvement improves patient outcomes.

Implications/Significance

This PDSA cycle demonstrated that targeted education for fellows can increase awareness of palliative care resources and improve referral rates. Future work will focus on reassessing usage of palliative care consults post-intervention to evaluate effects of fellows’ education of appropriate palliative care consultation, make necessary interventions based on data and further evaluate the long-term impact on patient outcomes at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.

Implementation of Consult Template Optimizes Hematology E-Consult Evaluation

Purpose/Background

The purpose of this project was to understand how implementing a consult template could optimize hematology E-consult evaluation. At the Tampa VA, providers can submit hematology E-consults for interpretation of lab abnormalities and management recommendations that do not require an in-person hematology evaluation. Previously, submission of an E-consult did not require prerequisite labs or imaging or for lab parameters to be met, leading to an increased number of hematology E-consults and subsequently, lower efficiency for hematologists.

Methods

A hematology E-consult template was created through collaboration between the hematology/ oncology and ambulatory care sections, which lists specific diagnoses and required parameters/workup needed for each diagnosis prior to submission of the E-consult. If those criteria were not met, the consult was cancelled. A representative sample of one month pre- and post-implementation data was analyzed.

Results

The E-consult template was implemented in September 2024. From April to August 2024, the average number of E-consults per month was 243, averaging at 11.0 per day, while from October 2024 to February 2025, the average number of E-consults per month was 146.4, averaging at 6.6 per day. In August 2024, the leading reasons for consult were anemia (77), leukocytosis (26), and thrombocytopenia (24). That month, there were 15 consult cancellations, with the primary reason being the patient was established in clinic (9). In October 2024, the leading reasons for consult were anemia (39), leukocytosis (14), and thrombocytopenia (13). That month, there were 34 consult cancellations, with the primary reason being that hematology advised a clinic consultation rather than an E-consult (10).

Implications/Significance

These data reveal that the hematology E-consult template was associated with a decreased number of E-consults per day and per month. Implementation of the hematology E-consult template allows the hematology consultants to focus on interpretation of lab results and providing management recommendations, as opposed to providing standard of care diagnostic recommendations. It also serves as an educational tool to referring providers, to understand appropriate indications for hematology E-consultation. Lastly, the template has created increased efficiency in providing hematology recommendations and ultimately, improved timely care for our veterans.

Purpose/Background

The purpose of this project was to understand how implementing a consult template could optimize hematology E-consult evaluation. At the Tampa VA, providers can submit hematology E-consults for interpretation of lab abnormalities and management recommendations that do not require an in-person hematology evaluation. Previously, submission of an E-consult did not require prerequisite labs or imaging or for lab parameters to be met, leading to an increased number of hematology E-consults and subsequently, lower efficiency for hematologists.

Methods

A hematology E-consult template was created through collaboration between the hematology/ oncology and ambulatory care sections, which lists specific diagnoses and required parameters/workup needed for each diagnosis prior to submission of the E-consult. If those criteria were not met, the consult was cancelled. A representative sample of one month pre- and post-implementation data was analyzed.

Results

The E-consult template was implemented in September 2024. From April to August 2024, the average number of E-consults per month was 243, averaging at 11.0 per day, while from October 2024 to February 2025, the average number of E-consults per month was 146.4, averaging at 6.6 per day. In August 2024, the leading reasons for consult were anemia (77), leukocytosis (26), and thrombocytopenia (24). That month, there were 15 consult cancellations, with the primary reason being the patient was established in clinic (9). In October 2024, the leading reasons for consult were anemia (39), leukocytosis (14), and thrombocytopenia (13). That month, there were 34 consult cancellations, with the primary reason being that hematology advised a clinic consultation rather than an E-consult (10).

Implications/Significance