User login

The Shifting Landscape of Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke

Study 1 Overview (Menon et al)

Objective: To determine whether a 0.25 mg/kg dose of intravenous tenecteplase is noninferior to intravenous alteplase 0.9 mg/kg for patients with acute ischemic stroke eligible for thrombolytic therapy.

Design: Multicenter, parallel-group, open-label randomized controlled trial.

Setting and participants: The trial was conducted at 22 primary and comprehensive stroke centers across Canada. A primary stroke center was defined as a hospital capable of offering intravenous thrombolysis to patients with acute ischemic stroke, while a comprehensive stroke center was able to offer thrombectomy services in addition. The involved centers also participated in Canadian quality improvement registries (either Quality Improvement and Clinical Research [QuiCR] or Optimizing Patient Treatment in Major Ischemic Stroke with EVT [OPTIMISE]) that track patient outcomes. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 18 years or older, had a diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke, presented within 4.5 hours of symptom onset, and were eligible for thrombolysis according to Canadian guidelines.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to either intravenous tenecteplase (0.25 mg/kg single dose, maximum of 25 mg) or intravenous alteplase (0.9 mg/kg total dose to a maximum of 90 mg, delivered as a bolus followed by a continuous infusion). A total of 1600 patients were enrolled, with 816 randomly assigned to the tenecteplase arm and 784 to the alteplase arm; 1577 patients were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis (n = 806 tenecteplase; n = 771 alteplase). The median age of enrollees was 74 years, and 52.1% of the ITT population were men.

Main outcome measures: In the ITT population, the primary outcome measure was a modified Rankin score (mRS) of 0 or 1 at 90 to 120 days post treatment. Safety outcomes included symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, orolingual angioedema, extracranial bleeding that required blood transfusion (all within 24 hours of thrombolytic administration), and all-cause mortality at 90 days. The noninferiority threshold for intravenous tenecteplase was set as the lower 95% CI of the difference between the tenecteplase and alteplase groups in the proportion of patients who met the primary outcome exceeding –5%.

Main results: The primary outcome of mRS of either 0 or 1 at 90 to 120 days of treatment occurred in 296 (36.9%) of the 802 patients assigned to tenecteplase and 266 (34.8%) of the 765 patients assigned to alteplase (unadjusted risk difference, 2.1%; 95% CI, –2.6 to 6.9). The prespecified noninferiority threshold was met. There were no significant differences between the groups in rates of intracerebral hemorrhage at 24 hours or 90-day all-cause mortality.

Conclusion: Intravenous tenecteplase is a reasonable alternative to alteplase for patients eligible for thrombolytic therapy.

Study 2 Overview (Wang et al)

Objective: To determine whether tenecteplase (dose 0.25 mg/kg) is noninferior to alteplase in patients with acute ischemic stroke who are within 4.5 hours of symptom onset and eligible for thrombolytic therapy but either refused or were ineligible for endovascular thrombectomy.

Design: Multicenter, prospective, open-label, randomized, controlled noninferiority trial.

Setting and participants: This trial was conducted at 53 centers across China and included patients 18 years of age or older who were within 4.5 hours of symptom onset and were thrombolytic eligible, had a mRS ≤ 1 at enrollment, and had a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score between 5 and 25. Eligible participants were randomized 1:1 to either tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg (maximum dose 25 mg) or alteplase 0.9 mg/kg (maximum dose 90 mg, administered as a bolus followed by infusion). During the enrollment period (June 12, 2021, to May 29, 2022), a total of 1430 participants were enrolled, and, of those, 716 were randomly assigned to tenecteplase and 714 to alteplase. Six patients assigned to tenecteplase and 7 assigned to alteplase did not receive drugs. At 90 days, 5 in the tenecteplase group and 11 in the alteplase group were lost to follow up.

Main outcome measures: The primary efficacy outcome was a mRS of 0 or 1 at 90 days. The primary safety outcome was intracranial hemorrhage within 36 hours. Safety outcomes included parenchymal hematoma 2, as defined by the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III; any intracranial or significant hemorrhage, as defined by the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries criteria; and death from all causes at 90 days. Noninferiority for tenecteplase would be declared if the lower 97.5% 1-sided CI for the relative risk (RR) for the primary outcome did not cross 0.937.

Main results: In the modified ITT population, the primary outcome occurred in 439 (62%) of the tenecteplase group and 405 (68%) of the alteplase group (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.98-1.16). This met the prespecified margin for noninferiority. Intracranial hemorrhage within 36 hours was experienced by 15 (2%) patients in the tenecteplase group and 13 (2%) in the alteplase group (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.56-2.50). Death at 90 days occurred in 46 (7%) patients in the tenecteplase group and 35 (5%) in the alteplase group (RR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.86-2.01).

Conclusion: Tenecteplase was noninferior to alteplase in patients with acute ischemic stroke who met criteria for thrombolysis and either refused or were ineligible for endovascular thrombectomy.

Commentary

Alteplase has been FDA-approved for managing acute ischemic stroke since 1996 and has demonstrated positive effects on functional outcomes. Drawbacks of alteplase therapy, however, include bleeding risk as well as cumbersome administration of a bolus dose followed by a 60-minute infusion. In recent years, the question of whether or not tenecteplase could replace alteplase as the preferred thrombolytic for acute ischemic stroke has garnered much attention. Several features of tenecteplase make it an attractive option, including increased fibrin specificity, a longer half-life, and ease of administration as a single, rapid bolus dose. In phase 2 trials that compared tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg with alteplase, findings suggested the potential for early neurological improvement as well as improved outcomes at 90 days. While the role of tenecteplase in acute myocardial infarction has been well established due to ease of use and a favorable adverse-effect profile,1 there is much less evidence from phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trials to secure the role of tenecteplase in acute ischemic stroke.2

Menon et al attempted to close this gap in the literature by conducting a randomized controlled clinical trial (AcT) comparing tenecteplase to alteplase in a Canadian patient population. The trial's patient population mirrors that of real-world data from global registries in terms of age, sex, and baseline stroke severity. In addition, the eligibility window of 4.5 hours from symptom onset as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria for therapy are common to those utilized in other countries, making the findings generalizable. There were some limitations to the study, however, including the impact of COVID-19 on recruitment efforts as well as limitations of research infrastructure and staffing, which may have limited enrollment efforts at primary stroke centers. Nonetheless, the authors concluded that their results provide evidence that tenecteplase is comparable to alteplase, with similar functional and safety outcomes.

TRACE-2 focused on an Asian patient population and provided follow up to the dose-ranging TRACE-1 phase 2 trial. TRACE-1 showed that tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg had a similar safety profile to alteplase 0.9 mg/kg in Chinese patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke. TRACE-2 sought to establish noninferiority of tenecteplase and excluded patients who were ineligible for or refused thrombectomy. Interestingly, the tenecteplase arm, as the authors point out, had numerically greater mortality as well as intracranial hemorrhage, but these differences were not statistically significant between the treatment groups at 90 days. The TRACE-2 results parallel those of AcT, and although there were differences in ethnicity between the 2 trials, the authors cite this as evidence that the results are consistent and provide evidence for the role of tenecteplase in the management of acute ischemic stroke. Limitations of this trial include potential bias from its open-label design, as well as exclusion of patients with more severe strokes eligible for thrombectomy, which may limit generalizability to patients with more disabling strokes who could have a higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage.

Application for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

Across the country, many organizations have adopted the off-label use of tenecteplase for managing fibrinolytic-eligible acute ischemic stroke patients. In most cases, the impetus for change is the ease of dosing and administration of tenecteplase compared to alteplase, while the inclusion and exclusion criteria and overall management remain the same. Timely administration of therapy in stroke is critical. This, along with other time constraints in stroke workflows, the weight-based calculation of alteplase doses, and alteplase’s administration method may lead to medication errors when using this agent to treat patients with acute stroke. The rapid, single-dose administration of tenecteplase removes many barriers that hospitals face when patients may need to be treated and then transferred to another site for further care. Without the worry to “drip and ship,” the completion of administration may allow for timely patient transfer and eliminate the need for monitoring of an infusion during transfer. For some organizations, there may be a potential for drug cost-savings as well as improved metrics, such as door-to-needle time, but the overall effects of switching from alteplase to tenecteplase remain to be seen. Currently, tenecteplase is included in stroke guidelines as a “reasonable choice,” though with a low level of evidence.3 However, these 2 studies support the role of tenecteplase in acute ischemic stroke treatment and may provide a foundation for further studies to establish the role of tenecteplase in the acute ischemic stroke population.

Practice Points

- Tenecteplase may be considered as an alternative to alteplase for acute ischemic stroke for patients who meet eligibility criteria for thrombolytics; this recommendation is included in the most recent stroke guidelines, although tenecteplase has not been demonstrated to be superior to alteplase.

- The ease of administration of tenecteplase as a single intravenous bolus dose represents a benefit compared to alteplase; it is an off-label use, however, and further studies are needed to establish the superiority of tenecteplase in terms of functional and safety outcomes.

– Carol Heunisch, PharmD, BCPS, BCCP

Pharmacy Department, NorthShore–Edward-Elmhurst Health, Evanston, IL

1. Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic (ASSENT-2) Investigators; F Van De Werf, J Adgey, et al. Single-bolus tenecteplase compared with front-loaded alteplase in acute myocardial infarction: the ASSENT-2 double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9180):716-722. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07403-6

2. Burgos AM, Saver JL. Evidence that tenecteplase is noninferior to alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: meta-analysis of 5 randomized trials. Stroke. 2019;50(8):2156-2162. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025080

3. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344-e418. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000211

Study 1 Overview (Menon et al)

Objective: To determine whether a 0.25 mg/kg dose of intravenous tenecteplase is noninferior to intravenous alteplase 0.9 mg/kg for patients with acute ischemic stroke eligible for thrombolytic therapy.

Design: Multicenter, parallel-group, open-label randomized controlled trial.

Setting and participants: The trial was conducted at 22 primary and comprehensive stroke centers across Canada. A primary stroke center was defined as a hospital capable of offering intravenous thrombolysis to patients with acute ischemic stroke, while a comprehensive stroke center was able to offer thrombectomy services in addition. The involved centers also participated in Canadian quality improvement registries (either Quality Improvement and Clinical Research [QuiCR] or Optimizing Patient Treatment in Major Ischemic Stroke with EVT [OPTIMISE]) that track patient outcomes. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 18 years or older, had a diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke, presented within 4.5 hours of symptom onset, and were eligible for thrombolysis according to Canadian guidelines.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to either intravenous tenecteplase (0.25 mg/kg single dose, maximum of 25 mg) or intravenous alteplase (0.9 mg/kg total dose to a maximum of 90 mg, delivered as a bolus followed by a continuous infusion). A total of 1600 patients were enrolled, with 816 randomly assigned to the tenecteplase arm and 784 to the alteplase arm; 1577 patients were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis (n = 806 tenecteplase; n = 771 alteplase). The median age of enrollees was 74 years, and 52.1% of the ITT population were men.

Main outcome measures: In the ITT population, the primary outcome measure was a modified Rankin score (mRS) of 0 or 1 at 90 to 120 days post treatment. Safety outcomes included symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, orolingual angioedema, extracranial bleeding that required blood transfusion (all within 24 hours of thrombolytic administration), and all-cause mortality at 90 days. The noninferiority threshold for intravenous tenecteplase was set as the lower 95% CI of the difference between the tenecteplase and alteplase groups in the proportion of patients who met the primary outcome exceeding –5%.

Main results: The primary outcome of mRS of either 0 or 1 at 90 to 120 days of treatment occurred in 296 (36.9%) of the 802 patients assigned to tenecteplase and 266 (34.8%) of the 765 patients assigned to alteplase (unadjusted risk difference, 2.1%; 95% CI, –2.6 to 6.9). The prespecified noninferiority threshold was met. There were no significant differences between the groups in rates of intracerebral hemorrhage at 24 hours or 90-day all-cause mortality.

Conclusion: Intravenous tenecteplase is a reasonable alternative to alteplase for patients eligible for thrombolytic therapy.

Study 2 Overview (Wang et al)

Objective: To determine whether tenecteplase (dose 0.25 mg/kg) is noninferior to alteplase in patients with acute ischemic stroke who are within 4.5 hours of symptom onset and eligible for thrombolytic therapy but either refused or were ineligible for endovascular thrombectomy.

Design: Multicenter, prospective, open-label, randomized, controlled noninferiority trial.

Setting and participants: This trial was conducted at 53 centers across China and included patients 18 years of age or older who were within 4.5 hours of symptom onset and were thrombolytic eligible, had a mRS ≤ 1 at enrollment, and had a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score between 5 and 25. Eligible participants were randomized 1:1 to either tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg (maximum dose 25 mg) or alteplase 0.9 mg/kg (maximum dose 90 mg, administered as a bolus followed by infusion). During the enrollment period (June 12, 2021, to May 29, 2022), a total of 1430 participants were enrolled, and, of those, 716 were randomly assigned to tenecteplase and 714 to alteplase. Six patients assigned to tenecteplase and 7 assigned to alteplase did not receive drugs. At 90 days, 5 in the tenecteplase group and 11 in the alteplase group were lost to follow up.

Main outcome measures: The primary efficacy outcome was a mRS of 0 or 1 at 90 days. The primary safety outcome was intracranial hemorrhage within 36 hours. Safety outcomes included parenchymal hematoma 2, as defined by the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III; any intracranial or significant hemorrhage, as defined by the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries criteria; and death from all causes at 90 days. Noninferiority for tenecteplase would be declared if the lower 97.5% 1-sided CI for the relative risk (RR) for the primary outcome did not cross 0.937.

Main results: In the modified ITT population, the primary outcome occurred in 439 (62%) of the tenecteplase group and 405 (68%) of the alteplase group (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.98-1.16). This met the prespecified margin for noninferiority. Intracranial hemorrhage within 36 hours was experienced by 15 (2%) patients in the tenecteplase group and 13 (2%) in the alteplase group (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.56-2.50). Death at 90 days occurred in 46 (7%) patients in the tenecteplase group and 35 (5%) in the alteplase group (RR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.86-2.01).

Conclusion: Tenecteplase was noninferior to alteplase in patients with acute ischemic stroke who met criteria for thrombolysis and either refused or were ineligible for endovascular thrombectomy.

Commentary

Alteplase has been FDA-approved for managing acute ischemic stroke since 1996 and has demonstrated positive effects on functional outcomes. Drawbacks of alteplase therapy, however, include bleeding risk as well as cumbersome administration of a bolus dose followed by a 60-minute infusion. In recent years, the question of whether or not tenecteplase could replace alteplase as the preferred thrombolytic for acute ischemic stroke has garnered much attention. Several features of tenecteplase make it an attractive option, including increased fibrin specificity, a longer half-life, and ease of administration as a single, rapid bolus dose. In phase 2 trials that compared tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg with alteplase, findings suggested the potential for early neurological improvement as well as improved outcomes at 90 days. While the role of tenecteplase in acute myocardial infarction has been well established due to ease of use and a favorable adverse-effect profile,1 there is much less evidence from phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trials to secure the role of tenecteplase in acute ischemic stroke.2

Menon et al attempted to close this gap in the literature by conducting a randomized controlled clinical trial (AcT) comparing tenecteplase to alteplase in a Canadian patient population. The trial's patient population mirrors that of real-world data from global registries in terms of age, sex, and baseline stroke severity. In addition, the eligibility window of 4.5 hours from symptom onset as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria for therapy are common to those utilized in other countries, making the findings generalizable. There were some limitations to the study, however, including the impact of COVID-19 on recruitment efforts as well as limitations of research infrastructure and staffing, which may have limited enrollment efforts at primary stroke centers. Nonetheless, the authors concluded that their results provide evidence that tenecteplase is comparable to alteplase, with similar functional and safety outcomes.

TRACE-2 focused on an Asian patient population and provided follow up to the dose-ranging TRACE-1 phase 2 trial. TRACE-1 showed that tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg had a similar safety profile to alteplase 0.9 mg/kg in Chinese patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke. TRACE-2 sought to establish noninferiority of tenecteplase and excluded patients who were ineligible for or refused thrombectomy. Interestingly, the tenecteplase arm, as the authors point out, had numerically greater mortality as well as intracranial hemorrhage, but these differences were not statistically significant between the treatment groups at 90 days. The TRACE-2 results parallel those of AcT, and although there were differences in ethnicity between the 2 trials, the authors cite this as evidence that the results are consistent and provide evidence for the role of tenecteplase in the management of acute ischemic stroke. Limitations of this trial include potential bias from its open-label design, as well as exclusion of patients with more severe strokes eligible for thrombectomy, which may limit generalizability to patients with more disabling strokes who could have a higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage.

Application for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

Across the country, many organizations have adopted the off-label use of tenecteplase for managing fibrinolytic-eligible acute ischemic stroke patients. In most cases, the impetus for change is the ease of dosing and administration of tenecteplase compared to alteplase, while the inclusion and exclusion criteria and overall management remain the same. Timely administration of therapy in stroke is critical. This, along with other time constraints in stroke workflows, the weight-based calculation of alteplase doses, and alteplase’s administration method may lead to medication errors when using this agent to treat patients with acute stroke. The rapid, single-dose administration of tenecteplase removes many barriers that hospitals face when patients may need to be treated and then transferred to another site for further care. Without the worry to “drip and ship,” the completion of administration may allow for timely patient transfer and eliminate the need for monitoring of an infusion during transfer. For some organizations, there may be a potential for drug cost-savings as well as improved metrics, such as door-to-needle time, but the overall effects of switching from alteplase to tenecteplase remain to be seen. Currently, tenecteplase is included in stroke guidelines as a “reasonable choice,” though with a low level of evidence.3 However, these 2 studies support the role of tenecteplase in acute ischemic stroke treatment and may provide a foundation for further studies to establish the role of tenecteplase in the acute ischemic stroke population.

Practice Points

- Tenecteplase may be considered as an alternative to alteplase for acute ischemic stroke for patients who meet eligibility criteria for thrombolytics; this recommendation is included in the most recent stroke guidelines, although tenecteplase has not been demonstrated to be superior to alteplase.

- The ease of administration of tenecteplase as a single intravenous bolus dose represents a benefit compared to alteplase; it is an off-label use, however, and further studies are needed to establish the superiority of tenecteplase in terms of functional and safety outcomes.

– Carol Heunisch, PharmD, BCPS, BCCP

Pharmacy Department, NorthShore–Edward-Elmhurst Health, Evanston, IL

Study 1 Overview (Menon et al)

Objective: To determine whether a 0.25 mg/kg dose of intravenous tenecteplase is noninferior to intravenous alteplase 0.9 mg/kg for patients with acute ischemic stroke eligible for thrombolytic therapy.

Design: Multicenter, parallel-group, open-label randomized controlled trial.

Setting and participants: The trial was conducted at 22 primary and comprehensive stroke centers across Canada. A primary stroke center was defined as a hospital capable of offering intravenous thrombolysis to patients with acute ischemic stroke, while a comprehensive stroke center was able to offer thrombectomy services in addition. The involved centers also participated in Canadian quality improvement registries (either Quality Improvement and Clinical Research [QuiCR] or Optimizing Patient Treatment in Major Ischemic Stroke with EVT [OPTIMISE]) that track patient outcomes. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 18 years or older, had a diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke, presented within 4.5 hours of symptom onset, and were eligible for thrombolysis according to Canadian guidelines.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to either intravenous tenecteplase (0.25 mg/kg single dose, maximum of 25 mg) or intravenous alteplase (0.9 mg/kg total dose to a maximum of 90 mg, delivered as a bolus followed by a continuous infusion). A total of 1600 patients were enrolled, with 816 randomly assigned to the tenecteplase arm and 784 to the alteplase arm; 1577 patients were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis (n = 806 tenecteplase; n = 771 alteplase). The median age of enrollees was 74 years, and 52.1% of the ITT population were men.

Main outcome measures: In the ITT population, the primary outcome measure was a modified Rankin score (mRS) of 0 or 1 at 90 to 120 days post treatment. Safety outcomes included symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, orolingual angioedema, extracranial bleeding that required blood transfusion (all within 24 hours of thrombolytic administration), and all-cause mortality at 90 days. The noninferiority threshold for intravenous tenecteplase was set as the lower 95% CI of the difference between the tenecteplase and alteplase groups in the proportion of patients who met the primary outcome exceeding –5%.

Main results: The primary outcome of mRS of either 0 or 1 at 90 to 120 days of treatment occurred in 296 (36.9%) of the 802 patients assigned to tenecteplase and 266 (34.8%) of the 765 patients assigned to alteplase (unadjusted risk difference, 2.1%; 95% CI, –2.6 to 6.9). The prespecified noninferiority threshold was met. There were no significant differences between the groups in rates of intracerebral hemorrhage at 24 hours or 90-day all-cause mortality.

Conclusion: Intravenous tenecteplase is a reasonable alternative to alteplase for patients eligible for thrombolytic therapy.

Study 2 Overview (Wang et al)

Objective: To determine whether tenecteplase (dose 0.25 mg/kg) is noninferior to alteplase in patients with acute ischemic stroke who are within 4.5 hours of symptom onset and eligible for thrombolytic therapy but either refused or were ineligible for endovascular thrombectomy.

Design: Multicenter, prospective, open-label, randomized, controlled noninferiority trial.

Setting and participants: This trial was conducted at 53 centers across China and included patients 18 years of age or older who were within 4.5 hours of symptom onset and were thrombolytic eligible, had a mRS ≤ 1 at enrollment, and had a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score between 5 and 25. Eligible participants were randomized 1:1 to either tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg (maximum dose 25 mg) or alteplase 0.9 mg/kg (maximum dose 90 mg, administered as a bolus followed by infusion). During the enrollment period (June 12, 2021, to May 29, 2022), a total of 1430 participants were enrolled, and, of those, 716 were randomly assigned to tenecteplase and 714 to alteplase. Six patients assigned to tenecteplase and 7 assigned to alteplase did not receive drugs. At 90 days, 5 in the tenecteplase group and 11 in the alteplase group were lost to follow up.

Main outcome measures: The primary efficacy outcome was a mRS of 0 or 1 at 90 days. The primary safety outcome was intracranial hemorrhage within 36 hours. Safety outcomes included parenchymal hematoma 2, as defined by the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III; any intracranial or significant hemorrhage, as defined by the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries criteria; and death from all causes at 90 days. Noninferiority for tenecteplase would be declared if the lower 97.5% 1-sided CI for the relative risk (RR) for the primary outcome did not cross 0.937.

Main results: In the modified ITT population, the primary outcome occurred in 439 (62%) of the tenecteplase group and 405 (68%) of the alteplase group (RR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.98-1.16). This met the prespecified margin for noninferiority. Intracranial hemorrhage within 36 hours was experienced by 15 (2%) patients in the tenecteplase group and 13 (2%) in the alteplase group (RR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.56-2.50). Death at 90 days occurred in 46 (7%) patients in the tenecteplase group and 35 (5%) in the alteplase group (RR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.86-2.01).

Conclusion: Tenecteplase was noninferior to alteplase in patients with acute ischemic stroke who met criteria for thrombolysis and either refused or were ineligible for endovascular thrombectomy.

Commentary

Alteplase has been FDA-approved for managing acute ischemic stroke since 1996 and has demonstrated positive effects on functional outcomes. Drawbacks of alteplase therapy, however, include bleeding risk as well as cumbersome administration of a bolus dose followed by a 60-minute infusion. In recent years, the question of whether or not tenecteplase could replace alteplase as the preferred thrombolytic for acute ischemic stroke has garnered much attention. Several features of tenecteplase make it an attractive option, including increased fibrin specificity, a longer half-life, and ease of administration as a single, rapid bolus dose. In phase 2 trials that compared tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg with alteplase, findings suggested the potential for early neurological improvement as well as improved outcomes at 90 days. While the role of tenecteplase in acute myocardial infarction has been well established due to ease of use and a favorable adverse-effect profile,1 there is much less evidence from phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trials to secure the role of tenecteplase in acute ischemic stroke.2

Menon et al attempted to close this gap in the literature by conducting a randomized controlled clinical trial (AcT) comparing tenecteplase to alteplase in a Canadian patient population. The trial's patient population mirrors that of real-world data from global registries in terms of age, sex, and baseline stroke severity. In addition, the eligibility window of 4.5 hours from symptom onset as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria for therapy are common to those utilized in other countries, making the findings generalizable. There were some limitations to the study, however, including the impact of COVID-19 on recruitment efforts as well as limitations of research infrastructure and staffing, which may have limited enrollment efforts at primary stroke centers. Nonetheless, the authors concluded that their results provide evidence that tenecteplase is comparable to alteplase, with similar functional and safety outcomes.

TRACE-2 focused on an Asian patient population and provided follow up to the dose-ranging TRACE-1 phase 2 trial. TRACE-1 showed that tenecteplase 0.25 mg/kg had a similar safety profile to alteplase 0.9 mg/kg in Chinese patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke. TRACE-2 sought to establish noninferiority of tenecteplase and excluded patients who were ineligible for or refused thrombectomy. Interestingly, the tenecteplase arm, as the authors point out, had numerically greater mortality as well as intracranial hemorrhage, but these differences were not statistically significant between the treatment groups at 90 days. The TRACE-2 results parallel those of AcT, and although there were differences in ethnicity between the 2 trials, the authors cite this as evidence that the results are consistent and provide evidence for the role of tenecteplase in the management of acute ischemic stroke. Limitations of this trial include potential bias from its open-label design, as well as exclusion of patients with more severe strokes eligible for thrombectomy, which may limit generalizability to patients with more disabling strokes who could have a higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage.

Application for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

Across the country, many organizations have adopted the off-label use of tenecteplase for managing fibrinolytic-eligible acute ischemic stroke patients. In most cases, the impetus for change is the ease of dosing and administration of tenecteplase compared to alteplase, while the inclusion and exclusion criteria and overall management remain the same. Timely administration of therapy in stroke is critical. This, along with other time constraints in stroke workflows, the weight-based calculation of alteplase doses, and alteplase’s administration method may lead to medication errors when using this agent to treat patients with acute stroke. The rapid, single-dose administration of tenecteplase removes many barriers that hospitals face when patients may need to be treated and then transferred to another site for further care. Without the worry to “drip and ship,” the completion of administration may allow for timely patient transfer and eliminate the need for monitoring of an infusion during transfer. For some organizations, there may be a potential for drug cost-savings as well as improved metrics, such as door-to-needle time, but the overall effects of switching from alteplase to tenecteplase remain to be seen. Currently, tenecteplase is included in stroke guidelines as a “reasonable choice,” though with a low level of evidence.3 However, these 2 studies support the role of tenecteplase in acute ischemic stroke treatment and may provide a foundation for further studies to establish the role of tenecteplase in the acute ischemic stroke population.

Practice Points

- Tenecteplase may be considered as an alternative to alteplase for acute ischemic stroke for patients who meet eligibility criteria for thrombolytics; this recommendation is included in the most recent stroke guidelines, although tenecteplase has not been demonstrated to be superior to alteplase.

- The ease of administration of tenecteplase as a single intravenous bolus dose represents a benefit compared to alteplase; it is an off-label use, however, and further studies are needed to establish the superiority of tenecteplase in terms of functional and safety outcomes.

– Carol Heunisch, PharmD, BCPS, BCCP

Pharmacy Department, NorthShore–Edward-Elmhurst Health, Evanston, IL

1. Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic (ASSENT-2) Investigators; F Van De Werf, J Adgey, et al. Single-bolus tenecteplase compared with front-loaded alteplase in acute myocardial infarction: the ASSENT-2 double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9180):716-722. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07403-6

2. Burgos AM, Saver JL. Evidence that tenecteplase is noninferior to alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: meta-analysis of 5 randomized trials. Stroke. 2019;50(8):2156-2162. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025080

3. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344-e418. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000211

1. Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic (ASSENT-2) Investigators; F Van De Werf, J Adgey, et al. Single-bolus tenecteplase compared with front-loaded alteplase in acute myocardial infarction: the ASSENT-2 double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354(9180):716-722. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07403-6

2. Burgos AM, Saver JL. Evidence that tenecteplase is noninferior to alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: meta-analysis of 5 randomized trials. Stroke. 2019;50(8):2156-2162. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025080

3. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344-e418. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000211

Best Practice Implementation and Clinical Inertia

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

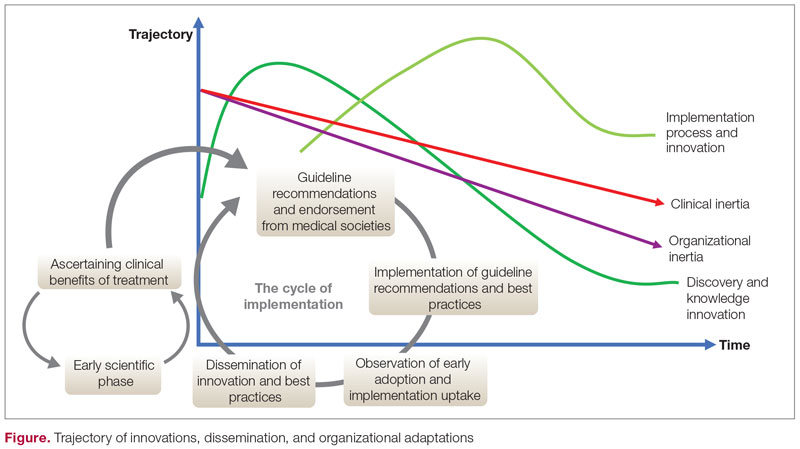

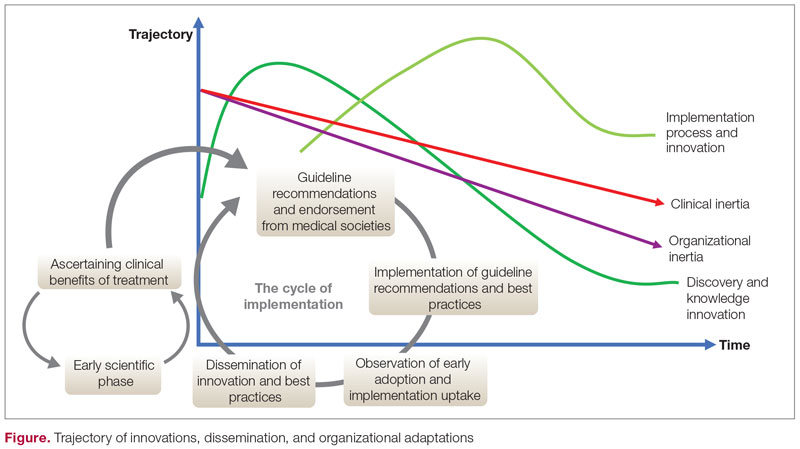

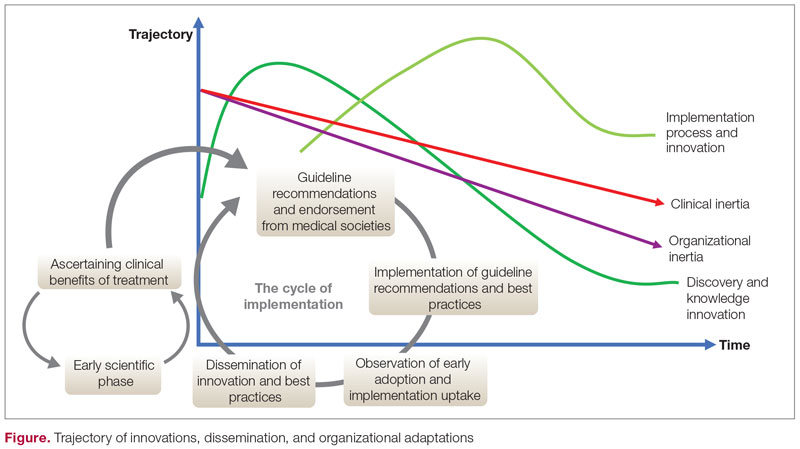

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

From the Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure of clinicians to initiate or escalate guideline-directed medical therapy to achieve treatment goals for well-defined clinical conditions.1,2 Evidence-based guidelines recommend optimal disease management with readily available medical therapies throughout the phases of clinical care. Unfortunately, the care provided to individual patients undergoes multiple modifications throughout the disease course, resulting in divergent pathways, significant deviations from treatment guidelines, and failure of “safeguard” checkpoints to reinstate, initiate, optimize, or stop treatments. Clinical inertia generally describes rigidity or resistance to change around implementing evidence-based guidelines. Furthermore, this term describes treatment behavior on the part of an individual clinician, not organizational inertia, which generally encompasses both internal (immediate clinical practice settings) and external factors (national and international guidelines and recommendations), eventually leading to resistance to optimizing disease treatment and therapeutic regimens. Individual clinicians’ clinical inertia in the form of resistance to guideline implementation and evidence-based principles can be one factor that drives organizational inertia. In turn, such individual behavior can be dictated by personal beliefs, knowledge, interpretation, skills, management principles, and biases. The terms therapeutic inertia or clinical inertia should not be confused with nonadherence from the patient’s standpoint when the clinician follows the best practice guidelines.3

Clinical inertia has been described in several clinical domains, including diabetes,4,5 hypertension,6,7 heart failure,8 depression,9 pulmonary medicine,10 and complex disease management.11 Clinicians can set suboptimal treatment goals due to specific beliefs and attitudes around optimal therapeutic goals. For example, when treating a patient with a chronic disease that is presently stable, a clinician could elect to initiate suboptimal treatment, as escalation of treatment might not be the priority in stable disease; they also may have concerns about overtreatment. Other factors that can contribute to clinical inertia (ie, undertreatment in the presence of indications for treatment) include those related to the patient, the clinical setting, and the organization, along with the importance of individualizing therapies in specific patients. Organizational inertia is the initial global resistance by the system to implementation, which can slow the dissemination and adaptation of best practices but eventually declines over time. Individual clinical inertia, on the other hand, will likely persist after the system-level rollout of guideline-based approaches.

The trajectory of dissemination, implementation, and adaptation of innovations and best practices is illustrated in the Figure. When the guidelines and medical societies endorse the adaptation of innovations or practice change after the benefits of such innovations/change have been established by the regulatory bodies, uptake can be hindered by both organizational and clinical inertia. Overcoming inertia to system-level changes requires addressing individual clinicians, along with practice and organizational factors, in order to ensure systematic adaptations. From the clinicians’ view, training and cognitive interventions to improve the adaptation and coping skills can improve understanding of treatment options through standardized educational and behavioral modification tools, direct and indirect feedback around performance, and decision support through a continuous improvement approach on both individual and system levels.

Addressing inertia in clinical practice requires a deep understanding of the individual and organizational elements that foster resistance to adapting best practice models. Research that explores tools and approaches to overcome inertia in managing complex diseases is a key step in advancing clinical innovation and disseminating best practices.

Corresponding author: Ebrahim Barkoudah, MD, MPH; ebarkoudah@bwh.harvard.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007

1. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(9):825-834. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012

2. Allen JD, Curtiss FR, Fairman KA. Nonadherence, clinical inertia, or therapeutic inertia? J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15(8):690-695. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.690

3. Zafar A, Davies M, Azhar A, Khunti K. Clinical inertia in management of T2DM. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4(4):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2010.07.003

4. Khunti K, Davies MJ. Clinical inertia—time to reappraise the terminology? Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(2):105-106. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2017.01.007

5. O’Connor PJ. Overcome clinical inertia to control systolic blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2677-2678. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.22.2677

6. Faria C, Wenzel M, Lee KW, et al. A narrative review of clinical inertia: focus on hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009;3(4):267-276. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2009.03.001

7. Jarjour M, Henri C, de Denus S, et al. Care gaps in adherence to heart failure guidelines: clinical inertia or physiological limitations? JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8(9):725-738. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.04.019

8. Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Med Care. 2009;47(9):959-67. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5da0

9. Cooke CE, Sidel M, Belletti DA, Fuhlbrigge AL. Clinical inertia in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2012;9(1):73-80. doi:10.3109/15412555.2011.631957

10. Whitford DL, Al-Anjawi HA, Al-Baharna MM. Impact of clinical inertia on cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2014;8(2):133-138. doi:10.1016/j.pcd.2013.10.007

The Role of Revascularization and Viability Testing in Patients With Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease and Severely Reduced Ejection Fraction

Study 1 Overview (STICHES Investigators)

Objective: To assess the survival benefit of coronary-artery bypass grafting (CABG) added to guideline-directed medical therapy, compared to optimal medical therapy (OMT) alone, in patients with coronary artery disease, heart failure, and severe left ventricular dysfunction. Design: Multicenter, randomized, prospective study with extended follow-up (median duration of 9.8 years).

Setting and participants: A total of 1212 patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35% or less and coronary artery disease were randomized to medical therapy plus CABG or OMT alone at 127 clinical sites in 26 countries.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint was death from any cause. Main secondary endpoints were death from cardiovascular causes and a composite outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes.

Main results: There were 359 primary outcome all-cause deaths (58.9%) in the CABG group and 398 (66.1%) in the medical therapy group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97; P = .02). Death from cardiovascular causes was reported in 247 patients (40.5%) in the CABG group and 297 patients (49.3%) in the medical therapy group (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.66-0.93; P < .01). The composite outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes occurred in 467 patients (76.6%) in the CABG group and 467 patients (87.0%) in the medical therapy group (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.64-0.82; P < .01).

Conclusion: Over a median follow-up of 9.8 years in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with severely reduced ejection fraction, the rates of death from any cause, death from cardiovascular causes, and the composite of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes were significantly lower in patients undergoing CABG than in patients receiving medical therapy alone.

Study 2 Overview (REVIVED BCIS Trial Group)

Objective: To assess whether percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can improve survival and left ventricular function in patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction as compared to OMT alone.

Design: Multicenter, randomized, prospective study.

Setting and participants: A total of 700 patients with LVEF <35% with severe coronary artery disease amendable to PCI and demonstrable myocardial viability were randomly assigned to either PCI plus optimal medical therapy (PCI group) or OMT alone (OMT group).

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome was death from any cause or hospitalization for heart failure. The main secondary outcomes were LVEF at 6 and 12 months and quality of life (QOL) scores.

Main results: Over a median follow-up of 41 months, the primary outcome was reported in 129 patients (37.2%) in the PCI group and in 134 patients (38.0%) in the OMT group (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.78-1.27; P = .96). The LVEF was similar in the 2 groups at 6 months (mean difference, –1.6 percentage points; 95% CI, –3.7 to 0.5) and at 12 months (mean difference, 0.9 percentage points; 95% CI, –1.7 to 3.4). QOL scores at 6 and 12 months favored the PCI group, but the difference had diminished at 24 months.

Conclusion: In patients with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy, revascularization by PCI in addition to OMT did not result in a lower incidence of death from any cause or hospitalization from heart failure.

Commentary

Coronary artery disease is the most common cause of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and an important cause of mortality.1 Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with reduced ejection fraction are often considered for revascularization in addition to OMT and device therapies. Although there have been multiple retrospective studies and registries suggesting that cardiac outcomes and LVEF improve with revascularization, the number of large-scale prospective studies that assessed this clinical question and randomized patients to revascularization plus OMT compared to OMT alone has been limited.

In the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure (STICH) study,2,3 eligible patients had coronary artery disease amendable to CABG and a LVEF of 35% or less. Patients (N = 1212) were randomly assigned to CABG plus OMT or OMT alone between July 2002 and May 2007. The original study, with a median follow-up of 5 years, did not show survival benefit, but the investigators reported that the primary outcome of death from any cause was significantly lower in the CABG group compared to OMT alone when follow-up of the same study population was extended to 9.8 years (58.9% vs 66.1%, P = .02). The findings from this study led to a class I guideline recommendation of CABG over medical therapy in patients with multivessel disease and low ejection fraction.4

Since the STICH trial was designed, there have been significant improvements in devices and techniques used for PCI, and the procedure is now widely performed in patients with multivessel disease.5 The advantages of PCI over CABG include shorter recovery times and lower risk of immediate complications. In this context, the recently reported Revascularization for Ischemic Ventricular Dysfunction (REVIVED) study assessed clinical outcomes in patients with severe coronary artery disease and reduced ejection fraction by randomizing patients to either PCI with OMT or OMT alone.6 At a median follow-up of 3.5 years, the investigators found no difference in the primary outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for heart failure (37.2% vs 38.0%; 95% CI, 0.78-1.28; P = .96). Moreover, the degree of LVEF improvement, assessed by follow-up echocardiogram read by the core lab, showed no difference in the degree of LVEF improvement between groups at 6 and 12 months. Finally, although results of the QOL assessment using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), a validated, patient-reported, heart-failure-specific QOL scale, favored the PCI group at 6 and 12 months of follow-up, the difference had diminished at 24 months.

The main strength of the REVIVED study was that it targeted a patient population with severe coronary artery disease, including left main disease and severely reduced ejection fraction, that historically have been excluded from large-scale randomized controlled studies evaluating PCI with OMT compared to OMT alone.7 However, there are several points to consider when interpreting the results of this study. First, further details of the PCI procedures are necessary. The REVIVED study recommended revascularization of all territories with viable myocardium; the anatomical revascularization index utilizing the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) Jeopardy Score was 71%. It is important to note that this jeopardy score was operator-reported and the core-lab adjudicated anatomical revascularization rate may be lower. Although viability testing primarily utilizing cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was performed in most patients, correlation between the revascularization territory and the viable segments has yet to be reported. Moreover, procedural details such as use of intravascular ultrasound and physiological testing, known to improve clinical outcome, need to be reported.8,9

Second, there is a high prevalence of ischemic cardiomyopathy, and it is important to note that the patients included in this study were highly selected from daily clinical practice, as evidenced by the prolonged enrollment period (8 years). Individuals were largely stable patients with less complex coronary anatomy as evidenced by the median interval from angiography to randomization of 80 days. Taking into consideration the degree of left ventricular dysfunction for patients included in the trial, only 14% of the patients had left main disease and half of the patients only had 2-vessel disease. The severity of the left main disease also needs to be clarified as it is likely that patients the operator determined to be critical were not enrolled in the study. Furthermore, the standard of care based on the STICH trial is to refer patients with severe multivessel coronary artery disease to CABG, making it more likely that patients with more severe and complex disease were not included in this trial. It is also important to note that this study enrolled patients with stable ischemic heart disease, and the data do not apply to patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome.

Third, although the primary outcome was similar between the groups, the secondary outcome of unplanned revascularization was lower in the PCI group. In addition, the rate of acute myocardial infarction (MI) was similar between the 2 groups, but the rate of spontaneous MI was lower in the PCI group compared to the OMT group (5.2% vs 9.3%) as 40% of MI cases in the PCI group were periprocedural MIs. The correlation between periprocedural MI and long-term outcomes has been modest compared to spontaneous MI. Moreover, with the longer follow-up, the number of spontaneous MI cases is expected to rise while the number of periprocedural MI cases is not. Extending the follow-up period is also important, as the STICH extension trial showed a statistically significant difference at 10-year follow up despite negative results at the time of the original publication.

Fourth, the REVIVED trial randomized a significantly lower number of patients compared to the STICH trial, and the authors reported fewer primary-outcome events than the estimated number needed to achieve the power to assess the primary hypothesis. In addition, significant improvements in medical treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction since the STICH trial make comparison of PCI vs CABG in this patient population unfeasible.

Finally, although severe angina was not an exclusion criterion, two-thirds of the patients enrolled had no angina, and only 2% of the patients had baseline severe angina. This is important to consider when interpreting the results of the patient-reported health status as previous studies have shown that patients with worse angina at baseline derive the largest improvement in their QOL,10,11 and symptom improvement is the main indication for PCI in patients with stable ischemic heart disease.

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

In patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction and multivessel stable ischemic heart disease who are well compensated and have little or no angina at baseline, OMT alone as an initial strategy may be considered against the addition of PCI after careful risk and benefit discussion. Further details about revascularization and extended follow-up data from the REVIVED trial are necessary.

Practice Points

- Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with reduced ejection fraction have been an understudied population in previous studies.

- Further studies are necessary to understand the benefits of revascularization and the role of viability testing in this population.

– Taishi Hirai MD, and Ziad Sayed Ahmad, MD

University of Missouri, Columbia, MO

1. Nowbar AN, Gitto M, Howard JP, et al. Mortality from ischemic heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(6):e005375. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES

2. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, et al; for the STICH Investigators. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(17):1607-1616. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1100356

3. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Jones RH, et al. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1511-1520. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602001

4. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(2):e21-e129. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.006

5. Kirtane AJ, Doshi D, Leon MB, et al. Treatment of higher-risk patients with an indication for revascularization: evolution within the field of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2016;134(5):422-431. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

6. Perera D, Clayton T, O’Kane PD, et al. Percutaneous revascularization for ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(15):1351-1360. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2206606

7. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. Circulation. 2020;142(18):1725-1735. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

8. De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(11):991-1001. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1205361

9. Zhang J, Gao X, Kan J, et al. Intravascular ultrasound versus angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation: The ULTIMATE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(24):3126-3137. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.013

10. Spertus JA, Jones PG, Maron DJ, et al. Health-status outcomes with invasive or conservative care in coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1408-1419. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1916370

11. Hirai T, Grantham JA, Sapontis J, et al. Quality of life changes after chronic total occlusion angioplasty in patients with baseline refractory angina. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e007558. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007558

Study 1 Overview (STICHES Investigators)

Objective: To assess the survival benefit of coronary-artery bypass grafting (CABG) added to guideline-directed medical therapy, compared to optimal medical therapy (OMT) alone, in patients with coronary artery disease, heart failure, and severe left ventricular dysfunction. Design: Multicenter, randomized, prospective study with extended follow-up (median duration of 9.8 years).

Setting and participants: A total of 1212 patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 35% or less and coronary artery disease were randomized to medical therapy plus CABG or OMT alone at 127 clinical sites in 26 countries.

Main outcome measures: The primary endpoint was death from any cause. Main secondary endpoints were death from cardiovascular causes and a composite outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes.

Main results: There were 359 primary outcome all-cause deaths (58.9%) in the CABG group and 398 (66.1%) in the medical therapy group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97; P = .02). Death from cardiovascular causes was reported in 247 patients (40.5%) in the CABG group and 297 patients (49.3%) in the medical therapy group (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.66-0.93; P < .01). The composite outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes occurred in 467 patients (76.6%) in the CABG group and 467 patients (87.0%) in the medical therapy group (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.64-0.82; P < .01).

Conclusion: Over a median follow-up of 9.8 years in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with severely reduced ejection fraction, the rates of death from any cause, death from cardiovascular causes, and the composite of death from any cause or hospitalization for cardiovascular causes were significantly lower in patients undergoing CABG than in patients receiving medical therapy alone.

Study 2 Overview (REVIVED BCIS Trial Group)

Objective: To assess whether percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can improve survival and left ventricular function in patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction as compared to OMT alone.

Design: Multicenter, randomized, prospective study.

Setting and participants: A total of 700 patients with LVEF <35% with severe coronary artery disease amendable to PCI and demonstrable myocardial viability were randomly assigned to either PCI plus optimal medical therapy (PCI group) or OMT alone (OMT group).

Main outcome measures: The primary outcome was death from any cause or hospitalization for heart failure. The main secondary outcomes were LVEF at 6 and 12 months and quality of life (QOL) scores.

Main results: Over a median follow-up of 41 months, the primary outcome was reported in 129 patients (37.2%) in the PCI group and in 134 patients (38.0%) in the OMT group (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.78-1.27; P = .96). The LVEF was similar in the 2 groups at 6 months (mean difference, –1.6 percentage points; 95% CI, –3.7 to 0.5) and at 12 months (mean difference, 0.9 percentage points; 95% CI, –1.7 to 3.4). QOL scores at 6 and 12 months favored the PCI group, but the difference had diminished at 24 months.

Conclusion: In patients with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy, revascularization by PCI in addition to OMT did not result in a lower incidence of death from any cause or hospitalization from heart failure.

Commentary

Coronary artery disease is the most common cause of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and an important cause of mortality.1 Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with reduced ejection fraction are often considered for revascularization in addition to OMT and device therapies. Although there have been multiple retrospective studies and registries suggesting that cardiac outcomes and LVEF improve with revascularization, the number of large-scale prospective studies that assessed this clinical question and randomized patients to revascularization plus OMT compared to OMT alone has been limited.

In the Surgical Treatment for Ischemic Heart Failure (STICH) study,2,3 eligible patients had coronary artery disease amendable to CABG and a LVEF of 35% or less. Patients (N = 1212) were randomly assigned to CABG plus OMT or OMT alone between July 2002 and May 2007. The original study, with a median follow-up of 5 years, did not show survival benefit, but the investigators reported that the primary outcome of death from any cause was significantly lower in the CABG group compared to OMT alone when follow-up of the same study population was extended to 9.8 years (58.9% vs 66.1%, P = .02). The findings from this study led to a class I guideline recommendation of CABG over medical therapy in patients with multivessel disease and low ejection fraction.4

Since the STICH trial was designed, there have been significant improvements in devices and techniques used for PCI, and the procedure is now widely performed in patients with multivessel disease.5 The advantages of PCI over CABG include shorter recovery times and lower risk of immediate complications. In this context, the recently reported Revascularization for Ischemic Ventricular Dysfunction (REVIVED) study assessed clinical outcomes in patients with severe coronary artery disease and reduced ejection fraction by randomizing patients to either PCI with OMT or OMT alone.6 At a median follow-up of 3.5 years, the investigators found no difference in the primary outcome of death from any cause or hospitalization for heart failure (37.2% vs 38.0%; 95% CI, 0.78-1.28; P = .96). Moreover, the degree of LVEF improvement, assessed by follow-up echocardiogram read by the core lab, showed no difference in the degree of LVEF improvement between groups at 6 and 12 months. Finally, although results of the QOL assessment using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), a validated, patient-reported, heart-failure-specific QOL scale, favored the PCI group at 6 and 12 months of follow-up, the difference had diminished at 24 months.

The main strength of the REVIVED study was that it targeted a patient population with severe coronary artery disease, including left main disease and severely reduced ejection fraction, that historically have been excluded from large-scale randomized controlled studies evaluating PCI with OMT compared to OMT alone.7 However, there are several points to consider when interpreting the results of this study. First, further details of the PCI procedures are necessary. The REVIVED study recommended revascularization of all territories with viable myocardium; the anatomical revascularization index utilizing the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) Jeopardy Score was 71%. It is important to note that this jeopardy score was operator-reported and the core-lab adjudicated anatomical revascularization rate may be lower. Although viability testing primarily utilizing cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was performed in most patients, correlation between the revascularization territory and the viable segments has yet to be reported. Moreover, procedural details such as use of intravascular ultrasound and physiological testing, known to improve clinical outcome, need to be reported.8,9

Second, there is a high prevalence of ischemic cardiomyopathy, and it is important to note that the patients included in this study were highly selected from daily clinical practice, as evidenced by the prolonged enrollment period (8 years). Individuals were largely stable patients with less complex coronary anatomy as evidenced by the median interval from angiography to randomization of 80 days. Taking into consideration the degree of left ventricular dysfunction for patients included in the trial, only 14% of the patients had left main disease and half of the patients only had 2-vessel disease. The severity of the left main disease also needs to be clarified as it is likely that patients the operator determined to be critical were not enrolled in the study. Furthermore, the standard of care based on the STICH trial is to refer patients with severe multivessel coronary artery disease to CABG, making it more likely that patients with more severe and complex disease were not included in this trial. It is also important to note that this study enrolled patients with stable ischemic heart disease, and the data do not apply to patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome.

Third, although the primary outcome was similar between the groups, the secondary outcome of unplanned revascularization was lower in the PCI group. In addition, the rate of acute myocardial infarction (MI) was similar between the 2 groups, but the rate of spontaneous MI was lower in the PCI group compared to the OMT group (5.2% vs 9.3%) as 40% of MI cases in the PCI group were periprocedural MIs. The correlation between periprocedural MI and long-term outcomes has been modest compared to spontaneous MI. Moreover, with the longer follow-up, the number of spontaneous MI cases is expected to rise while the number of periprocedural MI cases is not. Extending the follow-up period is also important, as the STICH extension trial showed a statistically significant difference at 10-year follow up despite negative results at the time of the original publication.

Fourth, the REVIVED trial randomized a significantly lower number of patients compared to the STICH trial, and the authors reported fewer primary-outcome events than the estimated number needed to achieve the power to assess the primary hypothesis. In addition, significant improvements in medical treatment for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction since the STICH trial make comparison of PCI vs CABG in this patient population unfeasible.

Finally, although severe angina was not an exclusion criterion, two-thirds of the patients enrolled had no angina, and only 2% of the patients had baseline severe angina. This is important to consider when interpreting the results of the patient-reported health status as previous studies have shown that patients with worse angina at baseline derive the largest improvement in their QOL,10,11 and symptom improvement is the main indication for PCI in patients with stable ischemic heart disease.

Applications for Clinical Practice and System Implementation

In patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction and multivessel stable ischemic heart disease who are well compensated and have little or no angina at baseline, OMT alone as an initial strategy may be considered against the addition of PCI after careful risk and benefit discussion. Further details about revascularization and extended follow-up data from the REVIVED trial are necessary.

Practice Points

- Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy with reduced ejection fraction have been an understudied population in previous studies.

- Further studies are necessary to understand the benefits of revascularization and the role of viability testing in this population.

– Taishi Hirai MD, and Ziad Sayed Ahmad, MD

University of Missouri, Columbia, MO

Study 1 Overview (STICHES Investigators)