User login

Now trending on social media: Bad birth control info

Add this to the list of social media’s potential health risks: unintended pregnancy.

That’s for women who take birth control advice from influencers, particularly on YouTube, where many talk about stopping hormonal contraception and may give incomplete or inaccurate sexual health information.

In an analysis of 50 YouTube videos, University of Delaware researchers found that nearly three-quarters of influencers talked about discontinuing birth control pills or other forms hormonal birth control. And 40% were using or had used a “natural family planning” method – when women track their cycle, sometimes using an app, to identify days they might get pregnant.

“We know from previous research that these nonhormonal options, such as fertility tracking apps, are not always as accurate as hormonal birth control,” said lead study author Emily Pfender, who reported the findings in Health Communication. “They rely on so many different factors, like body temperature and cervical fluid, that vary widely.”

In fact, this “natural” approach only works when women meticulously follow guidelines like measuring basal body temperature and tracking cervical fluid daily. But many influencers left that part out. Using fertility-tracking methods without the right education and tools could raise the risk of unplanned pregnancy, as failure rates using these methods vary from 2% to 23%, according to the CDC.

Even more alarming: Of the influencers who stopped hormonal birth control, only one-third mentioned replacing it with something else, Ms. Pfender said.

“The message that some of these videos are sending is that discontinuing [hormonal birth control] is good for if you want to improve your mental health and be more natural, but it’s not important to start another form of birth control,” she said. “This places those women at an increased risk of unplanned pregnancy, and possibly sexually transmitted diseases.”

Rise of the health influencer

Taking health advice from influencers is nothing new and appears to be getting more popular.

“People have been sharing health information for decades, even before the internet, but now it is much more prevalent and easier,” said Erin Willis, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who studies digital media and health communication.

Peer-to-peer health information is very influential, Dr. Willis said. It makes people feel understood, especially if they have the same health condition or share similar experiences or emotions. “The social support is there,” she said. “It is almost like crowdsourcing.”

In her study, Ms. Pfender and another researcher watched 50 YouTube videos posted between December 2019 and December 2021 by influencers with between 20,000 and 2.2 million followers. The top reasons influencers gave for discontinuing birth control included the desire to be more natural and to improve mental health.

Although hormonal birth control, namely the pill, has been used for decades and is considered safe, it has been linked to side effects like depression. And people sharing their experiences with hormonal birth control online may create controversy over whether it’s safe to use.

But Ms. Pfender found that influencers didn’t always share accurate or complete information. For example, some of the influencers talked about using the cycle tracking app Daysy, touting it as highly accurate, but none mentioned that the study backing up how well it worked was retracted in 2019 due to flaws in its research methods.

Not all health influencers give bad information, Dr. Willis said. Many go through ethics and advocacy training and understand the sensitive position and influence they have. Still, people have different levels of “health literacy” – some may understand health information better than others. It’s crucial to analyze the info and sort the good from the bad.

Look for information that is not linked to a particular product, the National Institutes of Health recommends. And cross-check it against reliable websites, such as those ending in “.gov” or “.org.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Add this to the list of social media’s potential health risks: unintended pregnancy.

That’s for women who take birth control advice from influencers, particularly on YouTube, where many talk about stopping hormonal contraception and may give incomplete or inaccurate sexual health information.

In an analysis of 50 YouTube videos, University of Delaware researchers found that nearly three-quarters of influencers talked about discontinuing birth control pills or other forms hormonal birth control. And 40% were using or had used a “natural family planning” method – when women track their cycle, sometimes using an app, to identify days they might get pregnant.

“We know from previous research that these nonhormonal options, such as fertility tracking apps, are not always as accurate as hormonal birth control,” said lead study author Emily Pfender, who reported the findings in Health Communication. “They rely on so many different factors, like body temperature and cervical fluid, that vary widely.”

In fact, this “natural” approach only works when women meticulously follow guidelines like measuring basal body temperature and tracking cervical fluid daily. But many influencers left that part out. Using fertility-tracking methods without the right education and tools could raise the risk of unplanned pregnancy, as failure rates using these methods vary from 2% to 23%, according to the CDC.

Even more alarming: Of the influencers who stopped hormonal birth control, only one-third mentioned replacing it with something else, Ms. Pfender said.

“The message that some of these videos are sending is that discontinuing [hormonal birth control] is good for if you want to improve your mental health and be more natural, but it’s not important to start another form of birth control,” she said. “This places those women at an increased risk of unplanned pregnancy, and possibly sexually transmitted diseases.”

Rise of the health influencer

Taking health advice from influencers is nothing new and appears to be getting more popular.

“People have been sharing health information for decades, even before the internet, but now it is much more prevalent and easier,” said Erin Willis, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who studies digital media and health communication.

Peer-to-peer health information is very influential, Dr. Willis said. It makes people feel understood, especially if they have the same health condition or share similar experiences or emotions. “The social support is there,” she said. “It is almost like crowdsourcing.”

In her study, Ms. Pfender and another researcher watched 50 YouTube videos posted between December 2019 and December 2021 by influencers with between 20,000 and 2.2 million followers. The top reasons influencers gave for discontinuing birth control included the desire to be more natural and to improve mental health.

Although hormonal birth control, namely the pill, has been used for decades and is considered safe, it has been linked to side effects like depression. And people sharing their experiences with hormonal birth control online may create controversy over whether it’s safe to use.

But Ms. Pfender found that influencers didn’t always share accurate or complete information. For example, some of the influencers talked about using the cycle tracking app Daysy, touting it as highly accurate, but none mentioned that the study backing up how well it worked was retracted in 2019 due to flaws in its research methods.

Not all health influencers give bad information, Dr. Willis said. Many go through ethics and advocacy training and understand the sensitive position and influence they have. Still, people have different levels of “health literacy” – some may understand health information better than others. It’s crucial to analyze the info and sort the good from the bad.

Look for information that is not linked to a particular product, the National Institutes of Health recommends. And cross-check it against reliable websites, such as those ending in “.gov” or “.org.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Add this to the list of social media’s potential health risks: unintended pregnancy.

That’s for women who take birth control advice from influencers, particularly on YouTube, where many talk about stopping hormonal contraception and may give incomplete or inaccurate sexual health information.

In an analysis of 50 YouTube videos, University of Delaware researchers found that nearly three-quarters of influencers talked about discontinuing birth control pills or other forms hormonal birth control. And 40% were using or had used a “natural family planning” method – when women track their cycle, sometimes using an app, to identify days they might get pregnant.

“We know from previous research that these nonhormonal options, such as fertility tracking apps, are not always as accurate as hormonal birth control,” said lead study author Emily Pfender, who reported the findings in Health Communication. “They rely on so many different factors, like body temperature and cervical fluid, that vary widely.”

In fact, this “natural” approach only works when women meticulously follow guidelines like measuring basal body temperature and tracking cervical fluid daily. But many influencers left that part out. Using fertility-tracking methods without the right education and tools could raise the risk of unplanned pregnancy, as failure rates using these methods vary from 2% to 23%, according to the CDC.

Even more alarming: Of the influencers who stopped hormonal birth control, only one-third mentioned replacing it with something else, Ms. Pfender said.

“The message that some of these videos are sending is that discontinuing [hormonal birth control] is good for if you want to improve your mental health and be more natural, but it’s not important to start another form of birth control,” she said. “This places those women at an increased risk of unplanned pregnancy, and possibly sexually transmitted diseases.”

Rise of the health influencer

Taking health advice from influencers is nothing new and appears to be getting more popular.

“People have been sharing health information for decades, even before the internet, but now it is much more prevalent and easier,” said Erin Willis, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who studies digital media and health communication.

Peer-to-peer health information is very influential, Dr. Willis said. It makes people feel understood, especially if they have the same health condition or share similar experiences or emotions. “The social support is there,” she said. “It is almost like crowdsourcing.”

In her study, Ms. Pfender and another researcher watched 50 YouTube videos posted between December 2019 and December 2021 by influencers with between 20,000 and 2.2 million followers. The top reasons influencers gave for discontinuing birth control included the desire to be more natural and to improve mental health.

Although hormonal birth control, namely the pill, has been used for decades and is considered safe, it has been linked to side effects like depression. And people sharing their experiences with hormonal birth control online may create controversy over whether it’s safe to use.

But Ms. Pfender found that influencers didn’t always share accurate or complete information. For example, some of the influencers talked about using the cycle tracking app Daysy, touting it as highly accurate, but none mentioned that the study backing up how well it worked was retracted in 2019 due to flaws in its research methods.

Not all health influencers give bad information, Dr. Willis said. Many go through ethics and advocacy training and understand the sensitive position and influence they have. Still, people have different levels of “health literacy” – some may understand health information better than others. It’s crucial to analyze the info and sort the good from the bad.

Look for information that is not linked to a particular product, the National Institutes of Health recommends. And cross-check it against reliable websites, such as those ending in “.gov” or “.org.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM HEALTH COMMUNICATION

Post ‘Roe,’ contraceptive failures carry bigger stakes

Birth control options have improved over the decades. Oral contraceptives are now safer, with fewer side effects. Intrauterine devices can prevent pregnancy 99.6% of the time. But no prescription drug or medical device works flawlessly, and people’s use of contraception is inexact.

“No one walks into my office and says, ‘I plan on missing a pill,’ ” said obstetrician-gynecologist Mitchell Creinin, MD.

“There is no such thing as perfect use; we are all real-life users,” said Dr. Creinin, a professor at the University of California, Davis, who wrote a widely used textbook that details contraceptive failure rates.

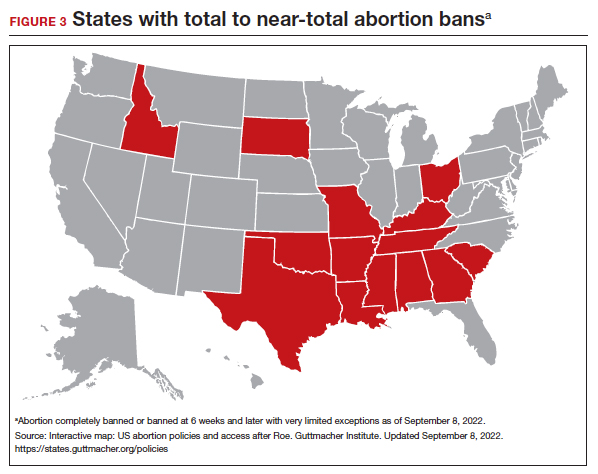

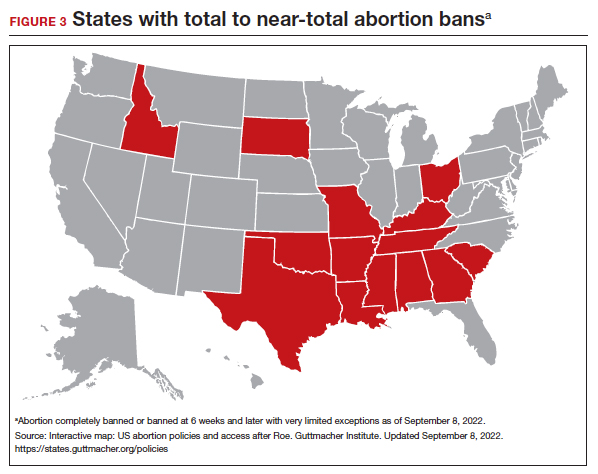

Even when the odds of contraception failure are small, the number of incidents can add up quickly. More than 47 million women of reproductive age in the United States use contraception, and, depending on the birth control method, hundreds of thousands of unplanned pregnancies can occur each year. With most abortions outlawed in at least 13 states and legal battles underway in others, contraceptive failures now carry bigger stakes for tens of millions of Americans.

Researchers distinguish between the perfect use of birth control, when a method is used consistently and correctly every time, and typical use, when a method is used in real-life circumstances. No birth control, short of a complete female sterilization, has a 0.00% failure rate.

The failure rate for typical use of birth control pills is 7%. For every million women taking pills, 70,000 unplanned pregnancies could occur in a year. According to the most recent data available, more than 6.5 million women ages 15 to 49 use oral contraceptives, leading to about 460,000 unplanned pregnancies.

Even seemingly minuscule failure rates of IUDs and birth control implants can lead to surprises.

An intrauterine device releases a hormone that thickens the mucus on the cervix. Sperm hit the brick wall of mucus and are unable to pass through the barrier. Implants are matchstick-sized plastic rods placed under the skin, which send a steady, low dose of hormone into the body that also thickens the cervical mucus and prevents the ovaries from releasing an egg. But not always. The hormonal IUD and implants fail to prevent pregnancy 0.1%-0.4% of the time.

Some 4.8 million women use IUDs or implants in the U.S., leading to as many as 5,000 to 20,000 unplanned pregnancies a year.

“We’ve had women come through here for abortions who had an IUD, and they were the one in a thousand,” said Gordon Low, a nurse practitioner at the Planned Parenthood in Little Rock.

Abortion has been outlawed in Arkansas since the Supreme Court’s ruling on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in late June. The only exception is when a patient’s death is considered imminent.

Those stakes are the new backdrop for couples making decisions about which form of contraception to choose or calculating the chances of pregnancy.

Another complication is the belief among many that contraceptives should work all the time, every time.

“In medicine, there is never anything that is 100%,” said Régine Sitruk-Ware, MD, a reproductive endocrinologist at the Population Council, a nonprofit research organization.

All sorts of factors interfere with contraceptive efficacy, said Dr. Sitruk-Ware. Certain medications for HIV and tuberculosis and the herbal supplement St. John’s wort can disrupt the liver’s processing of birth control pills. A medical provider might insert an IUD imprecisely into the uterus. Emergency contraception, including Plan B, is less effective in women weighing more than 165 pounds because the hormone in the medication is weight-dependent.

And life is hectic.

“You may have a delay in taking your next pill,” said Dr. Sitruk-Ware, or getting to the doctor to insert “your next vaginal ring.”

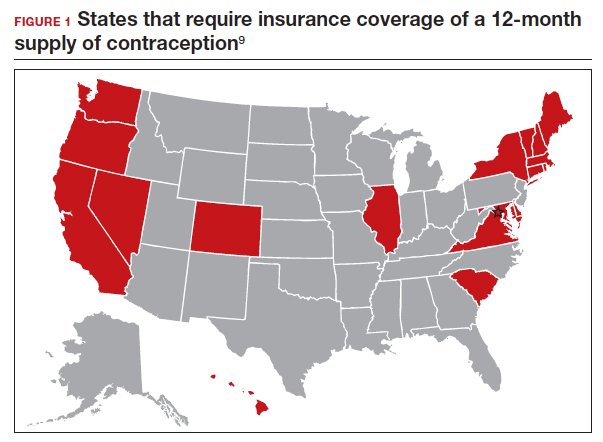

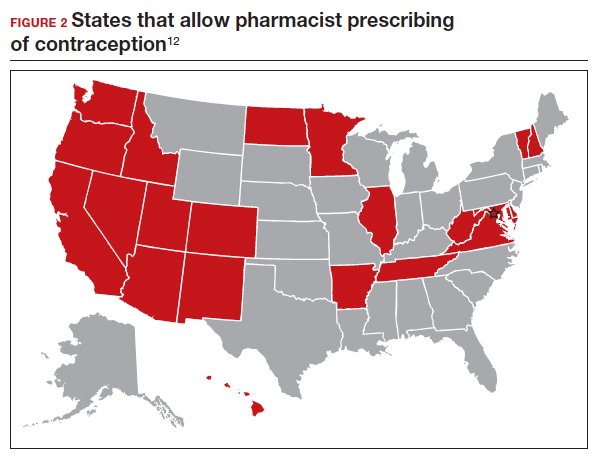

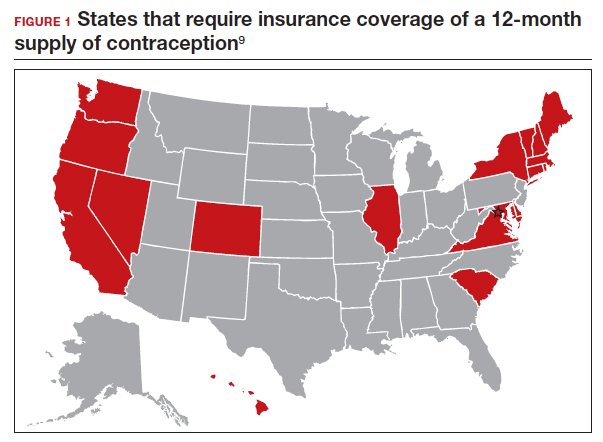

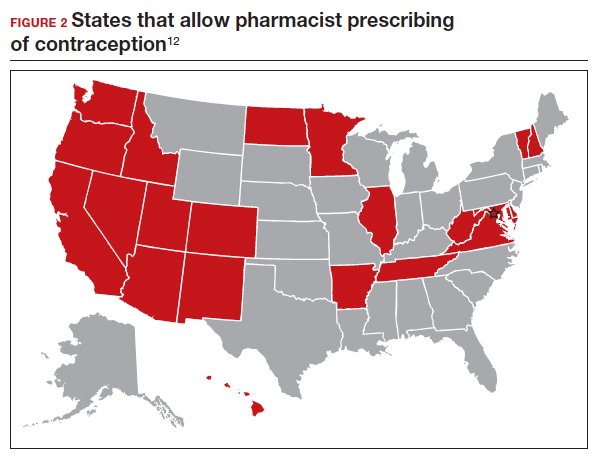

Using contraception consistently and correctly lessens the chance for a failure but Alina Salganicoff, KFF’s director of women’s health policy, said that for many people access to birth control is anything but dependable. Birth control pills are needed month after month, year after year, but “the vast majority of women can only get a one- to two-month supply,” she said.

Even vasectomies can fail.

During a vasectomy, the surgeon cuts the tube that carries sperm to the semen.

The procedure is one of the most effective methods of birth control – the failure rate is 0.15% – and avoids the side effects of hormonal birth control. But even after the vas deferens is cut, cells in the body can heal themselves, including after a vasectomy.

“If you get a cut on your finger, the skin covers it back up,” said Dr. Creinin. “Depending on how big the gap is and how the procedure is done, that tube may grow back together, and that’s one of the ways in which it fails.”

Researchers are testing reversible birth control methods for men, including a hormonal gel applied to the shoulders that suppresses sperm production. Among the 350 participants in the trial and their partners, so far zero pregnancies have occurred. It’s expected to take years for the new methods to reach the market and be available to consumers. Meanwhile, vasectomies and condoms remain the only contraception available for men, who remain fertile for much of their lives.

At 13%, the typical-use failure rate of condoms is among the highest of birth control methods. Condoms play a vital role in stopping the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, but they are often misused or tear. The typical-use failure rate means that for 1 million couples using condoms, 130,000 unplanned pregnancies could occur in one year.

Navigating the failure rates of birth control medicines and medical devices is just one aspect of preventing pregnancy. Ensuring a male sexual partner uses a condom can require negotiation or persuasion skills that can be difficult to navigate, said Jennifer Evans, an assistant teaching professor and health education specialist at Northeastern University.

Historically, women have had little to no say in whether to engage in sexual intercourse and limited autonomy over their bodies, complicating sexual-negotiation skills today, said Ms. Evans.

Part of Ms. Evans’ research focuses on men who coerce women into sex without a condom. One tactic, known as “stealthing,” is when a man puts on a condom but then removes it either before or during sexual intercourse without the other person’s knowledge or consent.

“In a lot of these stealthing cases women don’t necessarily know the condom has been used improperly,” said Ms. Evans. “It means they can’t engage in any kind of preventative behaviors like taking a Plan B or even going and getting an abortion in a timely manner.”

Ms. Evans has found that heterosexual men who engage in stealthing often have hostile attitudes toward women. They report that sex without a condom feels better or say they do it “for the thrill of engaging in a behavior they know is not OK,” she said. Ms. Evans cautions women who suspect a sexual partner will not use a condom correctly to not have sex with that person.

“The consequences were already severe before,” said Ms. Evans, “but now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned, they’re even more right now.”

This story is a collaboration between KHN and Science Friday. KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Birth control options have improved over the decades. Oral contraceptives are now safer, with fewer side effects. Intrauterine devices can prevent pregnancy 99.6% of the time. But no prescription drug or medical device works flawlessly, and people’s use of contraception is inexact.

“No one walks into my office and says, ‘I plan on missing a pill,’ ” said obstetrician-gynecologist Mitchell Creinin, MD.

“There is no such thing as perfect use; we are all real-life users,” said Dr. Creinin, a professor at the University of California, Davis, who wrote a widely used textbook that details contraceptive failure rates.

Even when the odds of contraception failure are small, the number of incidents can add up quickly. More than 47 million women of reproductive age in the United States use contraception, and, depending on the birth control method, hundreds of thousands of unplanned pregnancies can occur each year. With most abortions outlawed in at least 13 states and legal battles underway in others, contraceptive failures now carry bigger stakes for tens of millions of Americans.

Researchers distinguish between the perfect use of birth control, when a method is used consistently and correctly every time, and typical use, when a method is used in real-life circumstances. No birth control, short of a complete female sterilization, has a 0.00% failure rate.

The failure rate for typical use of birth control pills is 7%. For every million women taking pills, 70,000 unplanned pregnancies could occur in a year. According to the most recent data available, more than 6.5 million women ages 15 to 49 use oral contraceptives, leading to about 460,000 unplanned pregnancies.

Even seemingly minuscule failure rates of IUDs and birth control implants can lead to surprises.

An intrauterine device releases a hormone that thickens the mucus on the cervix. Sperm hit the brick wall of mucus and are unable to pass through the barrier. Implants are matchstick-sized plastic rods placed under the skin, which send a steady, low dose of hormone into the body that also thickens the cervical mucus and prevents the ovaries from releasing an egg. But not always. The hormonal IUD and implants fail to prevent pregnancy 0.1%-0.4% of the time.

Some 4.8 million women use IUDs or implants in the U.S., leading to as many as 5,000 to 20,000 unplanned pregnancies a year.

“We’ve had women come through here for abortions who had an IUD, and they were the one in a thousand,” said Gordon Low, a nurse practitioner at the Planned Parenthood in Little Rock.

Abortion has been outlawed in Arkansas since the Supreme Court’s ruling on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in late June. The only exception is when a patient’s death is considered imminent.

Those stakes are the new backdrop for couples making decisions about which form of contraception to choose or calculating the chances of pregnancy.

Another complication is the belief among many that contraceptives should work all the time, every time.

“In medicine, there is never anything that is 100%,” said Régine Sitruk-Ware, MD, a reproductive endocrinologist at the Population Council, a nonprofit research organization.

All sorts of factors interfere with contraceptive efficacy, said Dr. Sitruk-Ware. Certain medications for HIV and tuberculosis and the herbal supplement St. John’s wort can disrupt the liver’s processing of birth control pills. A medical provider might insert an IUD imprecisely into the uterus. Emergency contraception, including Plan B, is less effective in women weighing more than 165 pounds because the hormone in the medication is weight-dependent.

And life is hectic.

“You may have a delay in taking your next pill,” said Dr. Sitruk-Ware, or getting to the doctor to insert “your next vaginal ring.”

Using contraception consistently and correctly lessens the chance for a failure but Alina Salganicoff, KFF’s director of women’s health policy, said that for many people access to birth control is anything but dependable. Birth control pills are needed month after month, year after year, but “the vast majority of women can only get a one- to two-month supply,” she said.

Even vasectomies can fail.

During a vasectomy, the surgeon cuts the tube that carries sperm to the semen.

The procedure is one of the most effective methods of birth control – the failure rate is 0.15% – and avoids the side effects of hormonal birth control. But even after the vas deferens is cut, cells in the body can heal themselves, including after a vasectomy.

“If you get a cut on your finger, the skin covers it back up,” said Dr. Creinin. “Depending on how big the gap is and how the procedure is done, that tube may grow back together, and that’s one of the ways in which it fails.”

Researchers are testing reversible birth control methods for men, including a hormonal gel applied to the shoulders that suppresses sperm production. Among the 350 participants in the trial and their partners, so far zero pregnancies have occurred. It’s expected to take years for the new methods to reach the market and be available to consumers. Meanwhile, vasectomies and condoms remain the only contraception available for men, who remain fertile for much of their lives.

At 13%, the typical-use failure rate of condoms is among the highest of birth control methods. Condoms play a vital role in stopping the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, but they are often misused or tear. The typical-use failure rate means that for 1 million couples using condoms, 130,000 unplanned pregnancies could occur in one year.

Navigating the failure rates of birth control medicines and medical devices is just one aspect of preventing pregnancy. Ensuring a male sexual partner uses a condom can require negotiation or persuasion skills that can be difficult to navigate, said Jennifer Evans, an assistant teaching professor and health education specialist at Northeastern University.

Historically, women have had little to no say in whether to engage in sexual intercourse and limited autonomy over their bodies, complicating sexual-negotiation skills today, said Ms. Evans.

Part of Ms. Evans’ research focuses on men who coerce women into sex without a condom. One tactic, known as “stealthing,” is when a man puts on a condom but then removes it either before or during sexual intercourse without the other person’s knowledge or consent.

“In a lot of these stealthing cases women don’t necessarily know the condom has been used improperly,” said Ms. Evans. “It means they can’t engage in any kind of preventative behaviors like taking a Plan B or even going and getting an abortion in a timely manner.”

Ms. Evans has found that heterosexual men who engage in stealthing often have hostile attitudes toward women. They report that sex without a condom feels better or say they do it “for the thrill of engaging in a behavior they know is not OK,” she said. Ms. Evans cautions women who suspect a sexual partner will not use a condom correctly to not have sex with that person.

“The consequences were already severe before,” said Ms. Evans, “but now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned, they’re even more right now.”

This story is a collaboration between KHN and Science Friday. KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Birth control options have improved over the decades. Oral contraceptives are now safer, with fewer side effects. Intrauterine devices can prevent pregnancy 99.6% of the time. But no prescription drug or medical device works flawlessly, and people’s use of contraception is inexact.

“No one walks into my office and says, ‘I plan on missing a pill,’ ” said obstetrician-gynecologist Mitchell Creinin, MD.

“There is no such thing as perfect use; we are all real-life users,” said Dr. Creinin, a professor at the University of California, Davis, who wrote a widely used textbook that details contraceptive failure rates.

Even when the odds of contraception failure are small, the number of incidents can add up quickly. More than 47 million women of reproductive age in the United States use contraception, and, depending on the birth control method, hundreds of thousands of unplanned pregnancies can occur each year. With most abortions outlawed in at least 13 states and legal battles underway in others, contraceptive failures now carry bigger stakes for tens of millions of Americans.

Researchers distinguish between the perfect use of birth control, when a method is used consistently and correctly every time, and typical use, when a method is used in real-life circumstances. No birth control, short of a complete female sterilization, has a 0.00% failure rate.

The failure rate for typical use of birth control pills is 7%. For every million women taking pills, 70,000 unplanned pregnancies could occur in a year. According to the most recent data available, more than 6.5 million women ages 15 to 49 use oral contraceptives, leading to about 460,000 unplanned pregnancies.

Even seemingly minuscule failure rates of IUDs and birth control implants can lead to surprises.

An intrauterine device releases a hormone that thickens the mucus on the cervix. Sperm hit the brick wall of mucus and are unable to pass through the barrier. Implants are matchstick-sized plastic rods placed under the skin, which send a steady, low dose of hormone into the body that also thickens the cervical mucus and prevents the ovaries from releasing an egg. But not always. The hormonal IUD and implants fail to prevent pregnancy 0.1%-0.4% of the time.

Some 4.8 million women use IUDs or implants in the U.S., leading to as many as 5,000 to 20,000 unplanned pregnancies a year.

“We’ve had women come through here for abortions who had an IUD, and they were the one in a thousand,” said Gordon Low, a nurse practitioner at the Planned Parenthood in Little Rock.

Abortion has been outlawed in Arkansas since the Supreme Court’s ruling on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in late June. The only exception is when a patient’s death is considered imminent.

Those stakes are the new backdrop for couples making decisions about which form of contraception to choose or calculating the chances of pregnancy.

Another complication is the belief among many that contraceptives should work all the time, every time.

“In medicine, there is never anything that is 100%,” said Régine Sitruk-Ware, MD, a reproductive endocrinologist at the Population Council, a nonprofit research organization.

All sorts of factors interfere with contraceptive efficacy, said Dr. Sitruk-Ware. Certain medications for HIV and tuberculosis and the herbal supplement St. John’s wort can disrupt the liver’s processing of birth control pills. A medical provider might insert an IUD imprecisely into the uterus. Emergency contraception, including Plan B, is less effective in women weighing more than 165 pounds because the hormone in the medication is weight-dependent.

And life is hectic.

“You may have a delay in taking your next pill,” said Dr. Sitruk-Ware, or getting to the doctor to insert “your next vaginal ring.”

Using contraception consistently and correctly lessens the chance for a failure but Alina Salganicoff, KFF’s director of women’s health policy, said that for many people access to birth control is anything but dependable. Birth control pills are needed month after month, year after year, but “the vast majority of women can only get a one- to two-month supply,” she said.

Even vasectomies can fail.

During a vasectomy, the surgeon cuts the tube that carries sperm to the semen.

The procedure is one of the most effective methods of birth control – the failure rate is 0.15% – and avoids the side effects of hormonal birth control. But even after the vas deferens is cut, cells in the body can heal themselves, including after a vasectomy.

“If you get a cut on your finger, the skin covers it back up,” said Dr. Creinin. “Depending on how big the gap is and how the procedure is done, that tube may grow back together, and that’s one of the ways in which it fails.”

Researchers are testing reversible birth control methods for men, including a hormonal gel applied to the shoulders that suppresses sperm production. Among the 350 participants in the trial and their partners, so far zero pregnancies have occurred. It’s expected to take years for the new methods to reach the market and be available to consumers. Meanwhile, vasectomies and condoms remain the only contraception available for men, who remain fertile for much of their lives.

At 13%, the typical-use failure rate of condoms is among the highest of birth control methods. Condoms play a vital role in stopping the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, but they are often misused or tear. The typical-use failure rate means that for 1 million couples using condoms, 130,000 unplanned pregnancies could occur in one year.

Navigating the failure rates of birth control medicines and medical devices is just one aspect of preventing pregnancy. Ensuring a male sexual partner uses a condom can require negotiation or persuasion skills that can be difficult to navigate, said Jennifer Evans, an assistant teaching professor and health education specialist at Northeastern University.

Historically, women have had little to no say in whether to engage in sexual intercourse and limited autonomy over their bodies, complicating sexual-negotiation skills today, said Ms. Evans.

Part of Ms. Evans’ research focuses on men who coerce women into sex without a condom. One tactic, known as “stealthing,” is when a man puts on a condom but then removes it either before or during sexual intercourse without the other person’s knowledge or consent.

“In a lot of these stealthing cases women don’t necessarily know the condom has been used improperly,” said Ms. Evans. “It means they can’t engage in any kind of preventative behaviors like taking a Plan B or even going and getting an abortion in a timely manner.”

Ms. Evans has found that heterosexual men who engage in stealthing often have hostile attitudes toward women. They report that sex without a condom feels better or say they do it “for the thrill of engaging in a behavior they know is not OK,” she said. Ms. Evans cautions women who suspect a sexual partner will not use a condom correctly to not have sex with that person.

“The consequences were already severe before,” said Ms. Evans, “but now that Roe v. Wade has been overturned, they’re even more right now.”

This story is a collaboration between KHN and Science Friday. KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Sexual health care for disabled youth: Tough and getting tougher

The developmentally disabled girl was just 10 years old when Margaret Thew, DNP, medical director of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee, helped care for her. Providing that care was not emotionally easy. “Her brother’s friend sexually assaulted her and impregnated her,” Dr. Thew said.

The girl was able to obtain an abortion, a decision her parents supported. The alternative could have been deadly. “She was a tiny little person and would not have been able to carry a fetus,” Dr. Thew, a nurse practitioner, said.

Dr. Thew said she’s thankful that tragic case occurred before 2022. After the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, Wisconsin reverted to an 1849 law banning abortion. Although the law is currently being challenged, Dr. Thew wonders how the situation would have played out now. (Weeks after the Supreme Court’s decision, a similar case occurred in Ohio. In that case, a 10-year-old girl had to travel out of the state to obtain an abortion after having been raped.)

Talking to adolescents and young adults about reproductive health, whether regarding an unexpected pregnancy, the need for contraception, or to provide information about sexual activity, can be a challenge even for experienced health care providers.

The talks, decisions, and care are particularly complex when patients have developmental and intellectual disabilities. Among the many factors, Dr. Thew said, are dealing with menstruation, finding the right contraceptives, and counseling parents who might not want to acknowledge their children’s emerging sexuality.

Statistics: How many?

Because the definitions of disabilities vary and they represent a spectrum, estimates for how many youth have intellectual or developmental disabilities range widely.

In 2019, the National Survey of Children’s Health found that 1 in 4 children and adolescents aged 12-17 years have special health care needs because of disability. The American Community Survey estimates more than 1.3 million people aged 16-20 have a disability.

Intellectual disabilities can occur when a person’s IQ is below 70, significantly impeding the ability to perform activities of daily living, such as eating, dressing, and communicating. Developmental disabilities are impairments in physical, learning, language, and behavior, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Among the conditions are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorders, fragile X syndrome, learning and language problems, spina bifida, and other conditions.

Addressing common issues, concerns

April Kayser is a health educator for the Multnomah County Health Department, Portland, Ore. In 2016, Ms. Kayser and other experts conducted interviews with 11 youth with developmental and intellectual disabilities and 34 support people, either parents or professionals who provide services. The survey was part of the SHEIDD Project – short for Sexual Health Equity for Individuals with Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities – at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU).

From their findings, the researchers compiled guidelines. They provided scenarios that health care providers need to be aware of and that they need to be ready to address:

- A boy, 14, who is unclear about what to do when he feels sexually excited and wants to masturbate but isn’t at home. He has been told that masturbation is appropriate in private.

- A 20-year-old woman who lives in a group home is pregnant. She confesses to her parents during a visit that another resident is her boyfriend and that he is the father of the child she is expecting.

- A 17-year-old boy wants to ask out another student, who is 15.

Some developmentally and intellectually disabled youth can’t turn to their parents for help. One person in the survey said his father told him, “You don’t need to worry about any of that stuff. You’re too young.” Another said the job of a health care provider was to offer reproductive and sex education “to make sure you don’t screw up in some bad way.”

One finding stood out: Health care providers were at the top of the list of those whom young people trusted for information about reproductive and sexual health, Ms. Kayser said. Yet in her experience, she said, health care professionals are hesitant to bring up the issues with all youth, “especially those with intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

Health care providers often talk both to the patient and to the parents. Those conversations can be critical when a child is developmentally or intellectually disabled.

Women with disabilities have been shown to have a higher risk for adverse outcomes of pregnancy, said Willi Horner-Johnson, PhD, associate professor at OHSU–Portland State University School of Public Health.

In a recent study, she and her colleagues analyzed data from the CDC’s National Survey of Family Growth that included self-reported disability status. They found that the number of women with disabilities who give birth is far higher than was previously thought.

The researchers found that 19.5% of respondents who gave birth reported at least one sensory, cognitive, or mobility-related disability, a rate that is much greater than the less than 1%-6.6% estimates that are based on hospital discharge data.

Her group reported other troubling findings: Women with disabilities are twice as likely to have smoked during their pregnancy (19% vs. 8.9%) and are more likely to have preterm and low-birthweight babies.

Clinicians play an important role

Dr. Horner-Johnson agreed with the finding from the Multnomah County survey that health care providers play an important role in providing those with intellectual and developmental disabilities reproductive health care that meets their needs. “Clinicians need to be asking people with disabilities about their reproductive plans,” she said.

In the Multnomah County report, the researchers advised health care providers to recognize that people with disabilities are social and sexual beings; to learn about their goals, including those regarding sex and reproductive health; and to help youth build skills for healthy relationships and sexual activity.

Dr. Horner-Johnson pointed out that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “recommends that clinicians discuss reproductive plans at every visit, for example, by asking one key question – ‘Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?’ – of every woman of reproductive age.”

Some women will not be able to answer that question, and health care providers at times must rely on a caregiver for input. But many women, even those with disabilities, could answer if given a chance. She estimated that only about 5% of disabled people are unable to communicate. “Clinicians defer to the caregiver more than they need to,” she said.

Clinicians are becoming better at providing care to those with disabilities, Dr. Horner-Johnson said, yet they have a way to go. Clinician biases may prevent some from asking all women, including those with disabilities, about their reproductive plans. “Women with disabilities have described clinicians treating them as nonsexual, assuming or implying that they would not or should not get pregnant,” she writes in her report.

Such biases, she said, could be reduced by increased education of providers. A 2018 study in Health Equity found that only 19.3% of ob.gyns. said they felt equipped to manage the pregnancy of a woman with disabilities.

Managing sexuality and sexual health for youth with disabilities can be highly complex, according to Margaret Thew, DNP, medical director of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Challenges include the following:

- Parents often can’t deal with the reality that their teen or young adult is sexually active or may become so. Parents she helps often prefer to use the term “hormones,” not contraceptives, when talking about pregnancy prevention.

- Menstruation is a frequent concern, especially for youth with severe disabilities. Some react strongly to seeing a sanitary pad with blood, for example, by throwing it. Parents worry that caregivers will balk at changing pads regularly. As a result, some parents want complete menstrual suppression, Dr. Thew said. The American Academy of Pediatrics outlines how to approach menstrual suppression through methods such as the use of estrogen-progestin, progesterone, a ring, or a patch. In late August, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists released its clinical consensus on medical management of menstrual suppression.

- Some parents want to know how to obtain a complete hysterectomy for the patient – an option Dr. Thew and the AAP discourage. “We will tell them that’s not the best and safest approach, as you want to have the estrogen for bone health,” she said.

- After a discussion of all the options, an intrauterine device proves best for many. “That gives 7-8 years of protection,” she said, which is the approved effective duration for such devices. “They are less apt to have heavy monthly menstrual bleeding.”

- Parents of boys with disabilities, especially those with Down syndrome, often ask for sex education and guidance when sexual desires develop.

- Many parents want effective birth control for their children because of fear that their teen or young adult will be assaulted, a fear that isn’t groundless. Such cases are common, and caregivers frequently are the perpetrators.

Ms. Kayser, Dr. Horner-Johnson, and Dr. Thew have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The developmentally disabled girl was just 10 years old when Margaret Thew, DNP, medical director of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee, helped care for her. Providing that care was not emotionally easy. “Her brother’s friend sexually assaulted her and impregnated her,” Dr. Thew said.

The girl was able to obtain an abortion, a decision her parents supported. The alternative could have been deadly. “She was a tiny little person and would not have been able to carry a fetus,” Dr. Thew, a nurse practitioner, said.

Dr. Thew said she’s thankful that tragic case occurred before 2022. After the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, Wisconsin reverted to an 1849 law banning abortion. Although the law is currently being challenged, Dr. Thew wonders how the situation would have played out now. (Weeks after the Supreme Court’s decision, a similar case occurred in Ohio. In that case, a 10-year-old girl had to travel out of the state to obtain an abortion after having been raped.)

Talking to adolescents and young adults about reproductive health, whether regarding an unexpected pregnancy, the need for contraception, or to provide information about sexual activity, can be a challenge even for experienced health care providers.

The talks, decisions, and care are particularly complex when patients have developmental and intellectual disabilities. Among the many factors, Dr. Thew said, are dealing with menstruation, finding the right contraceptives, and counseling parents who might not want to acknowledge their children’s emerging sexuality.

Statistics: How many?

Because the definitions of disabilities vary and they represent a spectrum, estimates for how many youth have intellectual or developmental disabilities range widely.

In 2019, the National Survey of Children’s Health found that 1 in 4 children and adolescents aged 12-17 years have special health care needs because of disability. The American Community Survey estimates more than 1.3 million people aged 16-20 have a disability.

Intellectual disabilities can occur when a person’s IQ is below 70, significantly impeding the ability to perform activities of daily living, such as eating, dressing, and communicating. Developmental disabilities are impairments in physical, learning, language, and behavior, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Among the conditions are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorders, fragile X syndrome, learning and language problems, spina bifida, and other conditions.

Addressing common issues, concerns

April Kayser is a health educator for the Multnomah County Health Department, Portland, Ore. In 2016, Ms. Kayser and other experts conducted interviews with 11 youth with developmental and intellectual disabilities and 34 support people, either parents or professionals who provide services. The survey was part of the SHEIDD Project – short for Sexual Health Equity for Individuals with Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities – at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU).

From their findings, the researchers compiled guidelines. They provided scenarios that health care providers need to be aware of and that they need to be ready to address:

- A boy, 14, who is unclear about what to do when he feels sexually excited and wants to masturbate but isn’t at home. He has been told that masturbation is appropriate in private.

- A 20-year-old woman who lives in a group home is pregnant. She confesses to her parents during a visit that another resident is her boyfriend and that he is the father of the child she is expecting.

- A 17-year-old boy wants to ask out another student, who is 15.

Some developmentally and intellectually disabled youth can’t turn to their parents for help. One person in the survey said his father told him, “You don’t need to worry about any of that stuff. You’re too young.” Another said the job of a health care provider was to offer reproductive and sex education “to make sure you don’t screw up in some bad way.”

One finding stood out: Health care providers were at the top of the list of those whom young people trusted for information about reproductive and sexual health, Ms. Kayser said. Yet in her experience, she said, health care professionals are hesitant to bring up the issues with all youth, “especially those with intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

Health care providers often talk both to the patient and to the parents. Those conversations can be critical when a child is developmentally or intellectually disabled.

Women with disabilities have been shown to have a higher risk for adverse outcomes of pregnancy, said Willi Horner-Johnson, PhD, associate professor at OHSU–Portland State University School of Public Health.

In a recent study, she and her colleagues analyzed data from the CDC’s National Survey of Family Growth that included self-reported disability status. They found that the number of women with disabilities who give birth is far higher than was previously thought.

The researchers found that 19.5% of respondents who gave birth reported at least one sensory, cognitive, or mobility-related disability, a rate that is much greater than the less than 1%-6.6% estimates that are based on hospital discharge data.

Her group reported other troubling findings: Women with disabilities are twice as likely to have smoked during their pregnancy (19% vs. 8.9%) and are more likely to have preterm and low-birthweight babies.

Clinicians play an important role

Dr. Horner-Johnson agreed with the finding from the Multnomah County survey that health care providers play an important role in providing those with intellectual and developmental disabilities reproductive health care that meets their needs. “Clinicians need to be asking people with disabilities about their reproductive plans,” she said.

In the Multnomah County report, the researchers advised health care providers to recognize that people with disabilities are social and sexual beings; to learn about their goals, including those regarding sex and reproductive health; and to help youth build skills for healthy relationships and sexual activity.

Dr. Horner-Johnson pointed out that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “recommends that clinicians discuss reproductive plans at every visit, for example, by asking one key question – ‘Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?’ – of every woman of reproductive age.”

Some women will not be able to answer that question, and health care providers at times must rely on a caregiver for input. But many women, even those with disabilities, could answer if given a chance. She estimated that only about 5% of disabled people are unable to communicate. “Clinicians defer to the caregiver more than they need to,” she said.

Clinicians are becoming better at providing care to those with disabilities, Dr. Horner-Johnson said, yet they have a way to go. Clinician biases may prevent some from asking all women, including those with disabilities, about their reproductive plans. “Women with disabilities have described clinicians treating them as nonsexual, assuming or implying that they would not or should not get pregnant,” she writes in her report.

Such biases, she said, could be reduced by increased education of providers. A 2018 study in Health Equity found that only 19.3% of ob.gyns. said they felt equipped to manage the pregnancy of a woman with disabilities.

Managing sexuality and sexual health for youth with disabilities can be highly complex, according to Margaret Thew, DNP, medical director of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Challenges include the following:

- Parents often can’t deal with the reality that their teen or young adult is sexually active or may become so. Parents she helps often prefer to use the term “hormones,” not contraceptives, when talking about pregnancy prevention.

- Menstruation is a frequent concern, especially for youth with severe disabilities. Some react strongly to seeing a sanitary pad with blood, for example, by throwing it. Parents worry that caregivers will balk at changing pads regularly. As a result, some parents want complete menstrual suppression, Dr. Thew said. The American Academy of Pediatrics outlines how to approach menstrual suppression through methods such as the use of estrogen-progestin, progesterone, a ring, or a patch. In late August, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists released its clinical consensus on medical management of menstrual suppression.

- Some parents want to know how to obtain a complete hysterectomy for the patient – an option Dr. Thew and the AAP discourage. “We will tell them that’s not the best and safest approach, as you want to have the estrogen for bone health,” she said.

- After a discussion of all the options, an intrauterine device proves best for many. “That gives 7-8 years of protection,” she said, which is the approved effective duration for such devices. “They are less apt to have heavy monthly menstrual bleeding.”

- Parents of boys with disabilities, especially those with Down syndrome, often ask for sex education and guidance when sexual desires develop.

- Many parents want effective birth control for their children because of fear that their teen or young adult will be assaulted, a fear that isn’t groundless. Such cases are common, and caregivers frequently are the perpetrators.

Ms. Kayser, Dr. Horner-Johnson, and Dr. Thew have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The developmentally disabled girl was just 10 years old when Margaret Thew, DNP, medical director of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee, helped care for her. Providing that care was not emotionally easy. “Her brother’s friend sexually assaulted her and impregnated her,” Dr. Thew said.

The girl was able to obtain an abortion, a decision her parents supported. The alternative could have been deadly. “She was a tiny little person and would not have been able to carry a fetus,” Dr. Thew, a nurse practitioner, said.

Dr. Thew said she’s thankful that tragic case occurred before 2022. After the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, Wisconsin reverted to an 1849 law banning abortion. Although the law is currently being challenged, Dr. Thew wonders how the situation would have played out now. (Weeks after the Supreme Court’s decision, a similar case occurred in Ohio. In that case, a 10-year-old girl had to travel out of the state to obtain an abortion after having been raped.)

Talking to adolescents and young adults about reproductive health, whether regarding an unexpected pregnancy, the need for contraception, or to provide information about sexual activity, can be a challenge even for experienced health care providers.

The talks, decisions, and care are particularly complex when patients have developmental and intellectual disabilities. Among the many factors, Dr. Thew said, are dealing with menstruation, finding the right contraceptives, and counseling parents who might not want to acknowledge their children’s emerging sexuality.

Statistics: How many?

Because the definitions of disabilities vary and they represent a spectrum, estimates for how many youth have intellectual or developmental disabilities range widely.

In 2019, the National Survey of Children’s Health found that 1 in 4 children and adolescents aged 12-17 years have special health care needs because of disability. The American Community Survey estimates more than 1.3 million people aged 16-20 have a disability.

Intellectual disabilities can occur when a person’s IQ is below 70, significantly impeding the ability to perform activities of daily living, such as eating, dressing, and communicating. Developmental disabilities are impairments in physical, learning, language, and behavior, according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Among the conditions are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorders, fragile X syndrome, learning and language problems, spina bifida, and other conditions.

Addressing common issues, concerns

April Kayser is a health educator for the Multnomah County Health Department, Portland, Ore. In 2016, Ms. Kayser and other experts conducted interviews with 11 youth with developmental and intellectual disabilities and 34 support people, either parents or professionals who provide services. The survey was part of the SHEIDD Project – short for Sexual Health Equity for Individuals with Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities – at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU).

From their findings, the researchers compiled guidelines. They provided scenarios that health care providers need to be aware of and that they need to be ready to address:

- A boy, 14, who is unclear about what to do when he feels sexually excited and wants to masturbate but isn’t at home. He has been told that masturbation is appropriate in private.

- A 20-year-old woman who lives in a group home is pregnant. She confesses to her parents during a visit that another resident is her boyfriend and that he is the father of the child she is expecting.

- A 17-year-old boy wants to ask out another student, who is 15.

Some developmentally and intellectually disabled youth can’t turn to their parents for help. One person in the survey said his father told him, “You don’t need to worry about any of that stuff. You’re too young.” Another said the job of a health care provider was to offer reproductive and sex education “to make sure you don’t screw up in some bad way.”

One finding stood out: Health care providers were at the top of the list of those whom young people trusted for information about reproductive and sexual health, Ms. Kayser said. Yet in her experience, she said, health care professionals are hesitant to bring up the issues with all youth, “especially those with intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

Health care providers often talk both to the patient and to the parents. Those conversations can be critical when a child is developmentally or intellectually disabled.

Women with disabilities have been shown to have a higher risk for adverse outcomes of pregnancy, said Willi Horner-Johnson, PhD, associate professor at OHSU–Portland State University School of Public Health.

In a recent study, she and her colleagues analyzed data from the CDC’s National Survey of Family Growth that included self-reported disability status. They found that the number of women with disabilities who give birth is far higher than was previously thought.

The researchers found that 19.5% of respondents who gave birth reported at least one sensory, cognitive, or mobility-related disability, a rate that is much greater than the less than 1%-6.6% estimates that are based on hospital discharge data.

Her group reported other troubling findings: Women with disabilities are twice as likely to have smoked during their pregnancy (19% vs. 8.9%) and are more likely to have preterm and low-birthweight babies.

Clinicians play an important role

Dr. Horner-Johnson agreed with the finding from the Multnomah County survey that health care providers play an important role in providing those with intellectual and developmental disabilities reproductive health care that meets their needs. “Clinicians need to be asking people with disabilities about their reproductive plans,” she said.

In the Multnomah County report, the researchers advised health care providers to recognize that people with disabilities are social and sexual beings; to learn about their goals, including those regarding sex and reproductive health; and to help youth build skills for healthy relationships and sexual activity.

Dr. Horner-Johnson pointed out that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists “recommends that clinicians discuss reproductive plans at every visit, for example, by asking one key question – ‘Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?’ – of every woman of reproductive age.”

Some women will not be able to answer that question, and health care providers at times must rely on a caregiver for input. But many women, even those with disabilities, could answer if given a chance. She estimated that only about 5% of disabled people are unable to communicate. “Clinicians defer to the caregiver more than they need to,” she said.

Clinicians are becoming better at providing care to those with disabilities, Dr. Horner-Johnson said, yet they have a way to go. Clinician biases may prevent some from asking all women, including those with disabilities, about their reproductive plans. “Women with disabilities have described clinicians treating them as nonsexual, assuming or implying that they would not or should not get pregnant,” she writes in her report.

Such biases, she said, could be reduced by increased education of providers. A 2018 study in Health Equity found that only 19.3% of ob.gyns. said they felt equipped to manage the pregnancy of a woman with disabilities.

Managing sexuality and sexual health for youth with disabilities can be highly complex, according to Margaret Thew, DNP, medical director of adolescent medicine at Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Challenges include the following:

- Parents often can’t deal with the reality that their teen or young adult is sexually active or may become so. Parents she helps often prefer to use the term “hormones,” not contraceptives, when talking about pregnancy prevention.

- Menstruation is a frequent concern, especially for youth with severe disabilities. Some react strongly to seeing a sanitary pad with blood, for example, by throwing it. Parents worry that caregivers will balk at changing pads regularly. As a result, some parents want complete menstrual suppression, Dr. Thew said. The American Academy of Pediatrics outlines how to approach menstrual suppression through methods such as the use of estrogen-progestin, progesterone, a ring, or a patch. In late August, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists released its clinical consensus on medical management of menstrual suppression.

- Some parents want to know how to obtain a complete hysterectomy for the patient – an option Dr. Thew and the AAP discourage. “We will tell them that’s not the best and safest approach, as you want to have the estrogen for bone health,” she said.

- After a discussion of all the options, an intrauterine device proves best for many. “That gives 7-8 years of protection,” she said, which is the approved effective duration for such devices. “They are less apt to have heavy monthly menstrual bleeding.”

- Parents of boys with disabilities, especially those with Down syndrome, often ask for sex education and guidance when sexual desires develop.

- Many parents want effective birth control for their children because of fear that their teen or young adult will be assaulted, a fear that isn’t groundless. Such cases are common, and caregivers frequently are the perpetrators.

Ms. Kayser, Dr. Horner-Johnson, and Dr. Thew have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dermatologists fear effects of Dobbs decision for patients on isotretinoin, methotrexate

More than 3 months after the Dobbs decision by the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and revoked the constitutional right to an abortion, Some have beefed up their already stringent instructions and lengthy conversations about avoiding pregnancy while on the medication.

The major fear is that a patient who is taking contraceptive precautions, in accordance with the isotretinoin risk-management program, iPLEDGE, but still becomes pregnant while on isotretinoin may find out about the pregnancy too late to undergo an abortion in her own state and may not be able to travel to another state – or the patient may live in a state where abortions are entirely prohibited and is unable to travel to another state.

Isotretinoin is marketed as Absorica, Absorica LD, Claravis, Amnesteem, Myorisan, and Zenatane; its former brand name was Accutane.

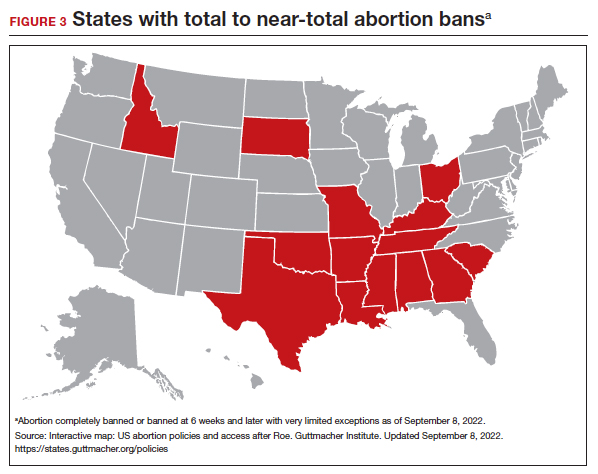

As of Oct. 7, a total of 14 states have banned most abortions, while 4 others have bans at 6, 15, 18, or 20 weeks. Attempts to restrict abortion on several other states are underway.

“To date, we don’t know of any specific effects of the Dobbs decision on isotretinoin prescribing, but with abortion access banned in many states, we anticipate that this could be a very real issue for individuals who accidentally become pregnant while taking isotretinoin,” said Ilona Frieden, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, and chair of the American Academy of Dermatology Association’s iPLEDGE Workgroup.

The iPLEDGE REMS (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy) is the Food and Drug Administration–required safety program that is in place to manage the risk of isotretinoin teratogenicity and minimize fetal exposure. The work group meets with the FDA and isotretinoin manufacturers to keep the program safe and operating smoothly. The iPLEDGE workgroup has not yet issued any specific statements on the implications of the Dobbs decision on prescribing isotretinoin.

But work on the issue is ongoing by the American Academy of Dermatology. In a statement issued in September, Mark D. Kaufmann, MD, president of the AAD, said that the academy “is continuing to work with its Patient Guidance for State Regulations Regarding Reproductive Health Task Force to help dermatologists best navigate state laws about how care should be implemented for patients who are or might become pregnant, and have been exposed to teratogenic medications.”

The task force, working with the academy, is “in the process of developing resources to help members better assist patients and have a productive and caring dialogue with them,” according to the statement. No specific timeline was given for when those resources might be available.

Methotrexate prescriptions

Also of concern are prescriptions for methotrexate, which is prescribed for psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and other skin diseases. Soon after the Dobbs decision was announced on June 24, pharmacies began to require pharmacists in states that banned abortions to verify that a prescription for methotrexate was not intended for an abortion, since methotrexate is used in combination with misoprostol for termination of an early pregnancy.

The action was taken, spokespersons for several major pharmacies said, to comply with state laws. According to Kara Page, a CVS spokesperson: “Pharmacists are caught in the middle on this issue.” Laws in some states, she told this news organization, “restrict the dispensing of medications for the purpose of inducing an abortion. These laws, some of which include criminal penalties, have forced us to require pharmacists in these states to validate that the intended indication is not to terminate a pregnancy before they can fill a prescription for methotrexate.”

“New laws in various states require additional steps for dispensing certain prescriptions and apply to all pharmacies, including Walgreens,” Fraser Engerman, a spokesperson for Walgreens, told this news organization. “In these states, our pharmacists work closely with prescribers as needed, to fill lawful, clinically appropriate prescriptions. We provide ongoing training and information to help our pharmacists understand the latest requirements in their area, and with these supports, the expectation is they are empowered to fill these prescriptions.”

The iPLEDGE program has numerous requirements before a patient can begin isotretinoin treatment. Patients capable of becoming pregnant must agree to use two effective forms of birth control during the entire treatment period, which typically lasts 4 or 5 months, as well as 1 month before and 1 month after treatment, or commit to total abstinence during that time.

Perspective: A Georgia dermatologist

Howa Yeung, MD, MSc, assistant professor of dermatology at Emory University, Atlanta, who sees patients regularly, practices in Georgia, where abortion is now banned at about 6 weeks of pregnancy. Dr. Yeung worries that some dermatologists in Georgia and elsewhere may not even want to take the risk of prescribing isotretinoin, although the results in treating resistant acne are well documented.

That isn’t his only concern. “Some may not want to prescribe it to a patient who reports they are abstinent and instead require them to go on two forms [of contraception].” Or some women who are not sexually active with anyone who can get them pregnant may also be asked to go on contraception, he said. Abstinence is an alternative option in iPLEDGE.

In the past, he said, well before the Dobbs decision, some doctors have argued that iPLEDGE should not include abstinence as an option. That 2020 report was challenged by others who pointed out that removing the abstinence option would pose ethical issues and may disproportionately affect minorities and others.

Before the Dobbs decision, Dr. Yeung noted, dermatologists prescribing isotretinoin focused on pregnancy prevention but knew that if pregnancy accidentally occurred, abortion was available as an option. “The reality after the decision is, it may or may not be available to all our patients.”

Of the 14 states banning most abortions, 10 are clustered within the South and Southeast. A woman living in Arkansas, which bans most abortions, for example, is surrounded by 6 other states that do the same.

Perspective: An Arizona dermatologist

Christina Kranc, MD, is a general dermatologist in Phoenix and Scottsdale. Arizona now bans most abortions. However, this has not changed her practice much when prescribing isotretinoin, she told this news organization, because when selecting appropriate candidates for the medication, she is strict on the contraceptive requirement, and only very rarely agrees to a patient relying on abstinence.

And if a patient capable of becoming pregnant was only having sex with another patient capable of becoming pregnant? Dr. Kranc said she would still require contraception unless it was impossible for pregnancy to occur.

Among the many scenarios a dermatologist might have to consider are a lesbian cisgender woman who is having, or has only had, sexual activity with another cisgender women.

Perspective: A Connecticut dermatologist

The concern is not only about isotretinoin but all teratogenic drugs, according to Jane M. Grant-Kels, MD, vice chair of dermatology and professor of dermatology, pathology, and pediatrics at the University of Connecticut, Farmington. She often prescribes methotrexate, which is also teratogenic.

Her advice for colleagues: “Whether you believe in abortion or not is irrelevant; it’s something you discuss with your patients.” She, too, fears that doctors in states banning abortions will stop prescribing these medications, “and that is very sad.”

For those practicing in states limiting or banning abortions, Dr. Grant-Kels said, “They need to have an even longer discussion with their patients about how serious this is.” Those doctors need to talk about not only two or three types of birth control, but also discuss with the patient about the potential need for travel, should pregnancy occur and abortion be the chosen option.

Although the newer biologics are an option for psoriasis, they are expensive. And, she said, many insurers require a step-therapy approach, and “want you to start with cheaper medications,” such as methotrexate. As a result, “in some states you won’t have access to the targeted therapies unless a patient fails something like methotrexate.”

Dr. Grant-Kels worries in particular about low-income women who may not have the means to travel to get an abortion.

Need for EC education

In a recent survey of 57 pediatric dermatologists who prescribe isotretinoin, only a third said they felt confident in their understanding of emergency contraception.

The authors of the study noted that the most common reasons for pregnancies during isotretinoin therapy reported to the FDA from 2011 to 2017 “included ineffective or inconsistent use” of contraceptives and “unsuccessful abstinence,” and recommended that physicians who prescribe isotretinoin update and increase their understanding of emergency contraception.

Dr. Yeung, Dr. Kranc, Dr. Grant-Kels, and Dr. Frieden reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than 3 months after the Dobbs decision by the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and revoked the constitutional right to an abortion, Some have beefed up their already stringent instructions and lengthy conversations about avoiding pregnancy while on the medication.

The major fear is that a patient who is taking contraceptive precautions, in accordance with the isotretinoin risk-management program, iPLEDGE, but still becomes pregnant while on isotretinoin may find out about the pregnancy too late to undergo an abortion in her own state and may not be able to travel to another state – or the patient may live in a state where abortions are entirely prohibited and is unable to travel to another state.

Isotretinoin is marketed as Absorica, Absorica LD, Claravis, Amnesteem, Myorisan, and Zenatane; its former brand name was Accutane.

As of Oct. 7, a total of 14 states have banned most abortions, while 4 others have bans at 6, 15, 18, or 20 weeks. Attempts to restrict abortion on several other states are underway.

“To date, we don’t know of any specific effects of the Dobbs decision on isotretinoin prescribing, but with abortion access banned in many states, we anticipate that this could be a very real issue for individuals who accidentally become pregnant while taking isotretinoin,” said Ilona Frieden, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco, and chair of the American Academy of Dermatology Association’s iPLEDGE Workgroup.

The iPLEDGE REMS (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy) is the Food and Drug Administration–required safety program that is in place to manage the risk of isotretinoin teratogenicity and minimize fetal exposure. The work group meets with the FDA and isotretinoin manufacturers to keep the program safe and operating smoothly. The iPLEDGE workgroup has not yet issued any specific statements on the implications of the Dobbs decision on prescribing isotretinoin.

But work on the issue is ongoing by the American Academy of Dermatology. In a statement issued in September, Mark D. Kaufmann, MD, president of the AAD, said that the academy “is continuing to work with its Patient Guidance for State Regulations Regarding Reproductive Health Task Force to help dermatologists best navigate state laws about how care should be implemented for patients who are or might become pregnant, and have been exposed to teratogenic medications.”

The task force, working with the academy, is “in the process of developing resources to help members better assist patients and have a productive and caring dialogue with them,” according to the statement. No specific timeline was given for when those resources might be available.

Methotrexate prescriptions

Also of concern are prescriptions for methotrexate, which is prescribed for psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and other skin diseases. Soon after the Dobbs decision was announced on June 24, pharmacies began to require pharmacists in states that banned abortions to verify that a prescription for methotrexate was not intended for an abortion, since methotrexate is used in combination with misoprostol for termination of an early pregnancy.

The action was taken, spokespersons for several major pharmacies said, to comply with state laws. According to Kara Page, a CVS spokesperson: “Pharmacists are caught in the middle on this issue.” Laws in some states, she told this news organization, “restrict the dispensing of medications for the purpose of inducing an abortion. These laws, some of which include criminal penalties, have forced us to require pharmacists in these states to validate that the intended indication is not to terminate a pregnancy before they can fill a prescription for methotrexate.”

“New laws in various states require additional steps for dispensing certain prescriptions and apply to all pharmacies, including Walgreens,” Fraser Engerman, a spokesperson for Walgreens, told this news organization. “In these states, our pharmacists work closely with prescribers as needed, to fill lawful, clinically appropriate prescriptions. We provide ongoing training and information to help our pharmacists understand the latest requirements in their area, and with these supports, the expectation is they are empowered to fill these prescriptions.”

The iPLEDGE program has numerous requirements before a patient can begin isotretinoin treatment. Patients capable of becoming pregnant must agree to use two effective forms of birth control during the entire treatment period, which typically lasts 4 or 5 months, as well as 1 month before and 1 month after treatment, or commit to total abstinence during that time.

Perspective: A Georgia dermatologist