User login

Robot-assisted laparoscopic tubal anastomosis following sterilization

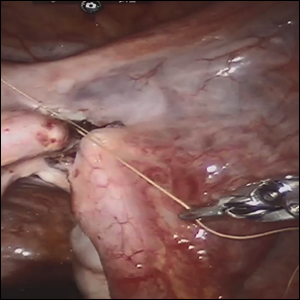

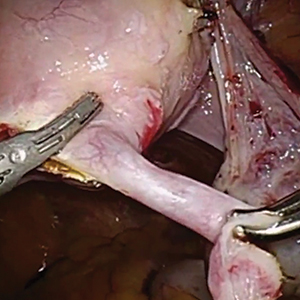

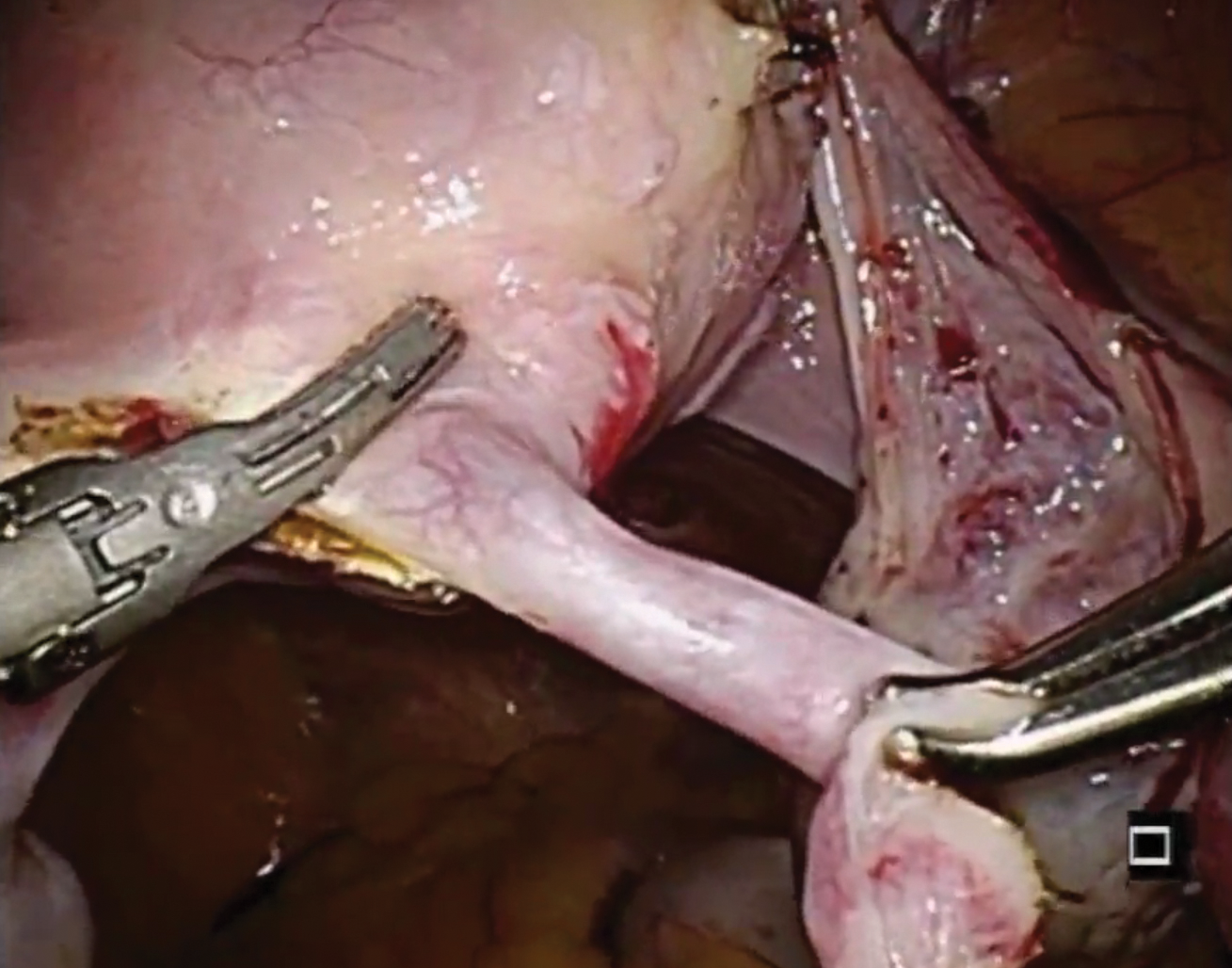

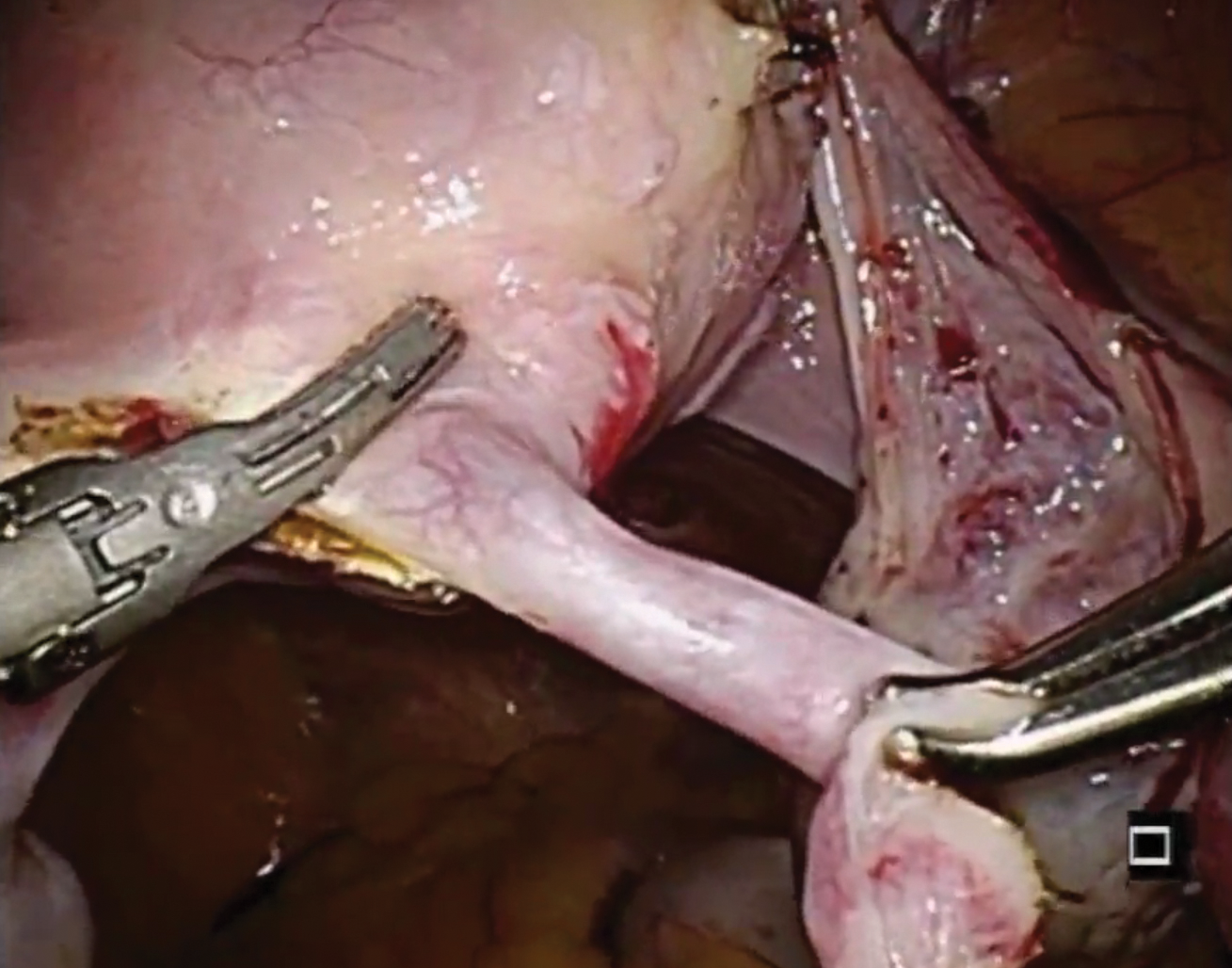

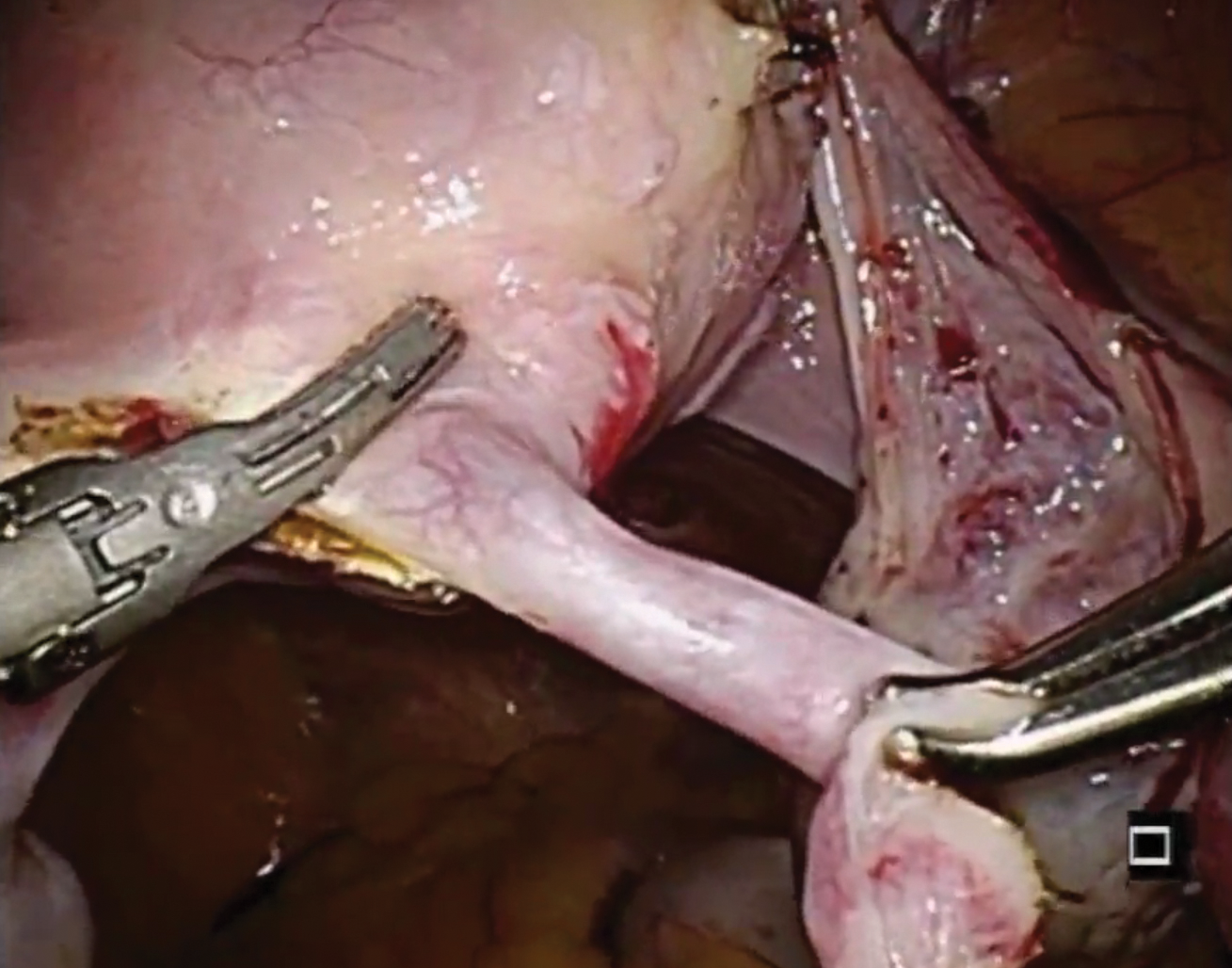

Female sterilization is the most common method of contraception worldwide, and the second most common contraceptive method used in the United States. Approximately 643,000 sterilization procedures are performed annually.1 Approximately 1% to 3% of women who undergo sterilization will subsequently undergo a sterilization reversal.2 Although multiple variables have been identified, change in marital status is the most commonly cited reason for desiring a tubal reversal.3,4 Tubal anastomosis can be a technically challenging surgical procedure when done by laparoscopy, especially given the microsurgical elements that are required. Several modifications, including limiting the number of sutures, have evolved as a result of its tedious nature.5 By leveraging 3D magnification, articulating instruments, and tremor filtration, it is only natural that robotic surgery has been applied to tubal anastomosis.

In this video, we review some background information surrounding a tubal reversal, followed by demonstration of a robotic interpretation of a 2-stitch anastomosis technique in a patient who successfully conceived and delivered.6 Overall robot-assisted laparoscopic tubal anastomosis is a feasible and safe option for women who desire reversal of surgical sterilization, with pregnancy and live-birth rates comparable to those observed when an open technique is utilized.7 I hope that you will find this video beneficial to your clinical practice.

- Chan LM, Westhoff CL. Tubal sterilization trends in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1-6.

- Moss CC. Sterilization: a review and update. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015-12-01;42:713-724.

- Gordts S, Campo R, Puttemans P, Gordts S. Clinical factors determining pregnancy outcome after microsurgical tubal anastomosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1198-1202.

- Chi I-C, Jones DB. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of poststerilization regret in women. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1994;49:722-732.

- Dubuisson JB, Swolin K. Laparoscopic tubal anastomosis (the one stitch technique): preliminary results. Human Reprod. 1995;10:2044-2046.

- Bissonnette FCA, Lapensee L, Bouzayen R. Outpatient laparoscopic tubal anastomosis and subsequent fertility. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:549-552.

- Caillet M, Vandromme J, Rozenberg S, Paesmans M, Germay O, Degueldre M. Robotically assisted laparoscopic microsurgical tubal anastomosis: a retrospective study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1844-1847.

Female sterilization is the most common method of contraception worldwide, and the second most common contraceptive method used in the United States. Approximately 643,000 sterilization procedures are performed annually.1 Approximately 1% to 3% of women who undergo sterilization will subsequently undergo a sterilization reversal.2 Although multiple variables have been identified, change in marital status is the most commonly cited reason for desiring a tubal reversal.3,4 Tubal anastomosis can be a technically challenging surgical procedure when done by laparoscopy, especially given the microsurgical elements that are required. Several modifications, including limiting the number of sutures, have evolved as a result of its tedious nature.5 By leveraging 3D magnification, articulating instruments, and tremor filtration, it is only natural that robotic surgery has been applied to tubal anastomosis.

In this video, we review some background information surrounding a tubal reversal, followed by demonstration of a robotic interpretation of a 2-stitch anastomosis technique in a patient who successfully conceived and delivered.6 Overall robot-assisted laparoscopic tubal anastomosis is a feasible and safe option for women who desire reversal of surgical sterilization, with pregnancy and live-birth rates comparable to those observed when an open technique is utilized.7 I hope that you will find this video beneficial to your clinical practice.

Female sterilization is the most common method of contraception worldwide, and the second most common contraceptive method used in the United States. Approximately 643,000 sterilization procedures are performed annually.1 Approximately 1% to 3% of women who undergo sterilization will subsequently undergo a sterilization reversal.2 Although multiple variables have been identified, change in marital status is the most commonly cited reason for desiring a tubal reversal.3,4 Tubal anastomosis can be a technically challenging surgical procedure when done by laparoscopy, especially given the microsurgical elements that are required. Several modifications, including limiting the number of sutures, have evolved as a result of its tedious nature.5 By leveraging 3D magnification, articulating instruments, and tremor filtration, it is only natural that robotic surgery has been applied to tubal anastomosis.

In this video, we review some background information surrounding a tubal reversal, followed by demonstration of a robotic interpretation of a 2-stitch anastomosis technique in a patient who successfully conceived and delivered.6 Overall robot-assisted laparoscopic tubal anastomosis is a feasible and safe option for women who desire reversal of surgical sterilization, with pregnancy and live-birth rates comparable to those observed when an open technique is utilized.7 I hope that you will find this video beneficial to your clinical practice.

- Chan LM, Westhoff CL. Tubal sterilization trends in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1-6.

- Moss CC. Sterilization: a review and update. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015-12-01;42:713-724.

- Gordts S, Campo R, Puttemans P, Gordts S. Clinical factors determining pregnancy outcome after microsurgical tubal anastomosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1198-1202.

- Chi I-C, Jones DB. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of poststerilization regret in women. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1994;49:722-732.

- Dubuisson JB, Swolin K. Laparoscopic tubal anastomosis (the one stitch technique): preliminary results. Human Reprod. 1995;10:2044-2046.

- Bissonnette FCA, Lapensee L, Bouzayen R. Outpatient laparoscopic tubal anastomosis and subsequent fertility. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:549-552.

- Caillet M, Vandromme J, Rozenberg S, Paesmans M, Germay O, Degueldre M. Robotically assisted laparoscopic microsurgical tubal anastomosis: a retrospective study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1844-1847.

- Chan LM, Westhoff CL. Tubal sterilization trends in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1-6.

- Moss CC. Sterilization: a review and update. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015-12-01;42:713-724.

- Gordts S, Campo R, Puttemans P, Gordts S. Clinical factors determining pregnancy outcome after microsurgical tubal anastomosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1198-1202.

- Chi I-C, Jones DB. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of poststerilization regret in women. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1994;49:722-732.

- Dubuisson JB, Swolin K. Laparoscopic tubal anastomosis (the one stitch technique): preliminary results. Human Reprod. 1995;10:2044-2046.

- Bissonnette FCA, Lapensee L, Bouzayen R. Outpatient laparoscopic tubal anastomosis and subsequent fertility. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:549-552.

- Caillet M, Vandromme J, Rozenberg S, Paesmans M, Germay O, Degueldre M. Robotically assisted laparoscopic microsurgical tubal anastomosis: a retrospective study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1844-1847.

Are women seeking short-acting contraception satisfied with LARC after giving it a try?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Because of women’s personal preference and aversion, for various reasons, to LARC methods, the current estimated use rate of 17% for LARC methods would increase only to 24% to 29% even if major barriers, such as cost and availability, were removed.1 To gain more insight into this issue, Hubacher and colleagues sought to determine if LARC methods would meet the contraceptive needs and be acceptable to a population of women who were not seeking these methods actively and who might have some reservation about using them.

Details of the study

The authors approached women actively seeking 1 of the 2 SARC methods but not a LARC method for contraception. They enrolled 524 women into a cohort study in which they received their desired SARC method. In addition, 392 women agreed to be enrolled in a randomized clinical trial comparing women beginning a LARC method for the first time with a group receiving 1 of the 2 SARC methods.

Importance of covered costs. Of note, the women in the randomized trial had the costs of the insertion or removal of the LARC method covered; those randomly assigned to the comparative SARC arm had the costs of their oral contraceptives (OCs) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) covered for the first year of use. Underwriting the costs in the randomized study was likely important for study recruitment, since 47% of participants who were randomized to the LARC group cited cost as one of the reasons they did not try a LARC method previously.

Satisfaction with contraceptive method. In addition to the differences in continuation rates and pregnancy rates noted, it is interesting that, among women who tried a LARC method and who had some persistent negative feelings about the method, 65.9% would try the method again.

Satisfaction levels were estimated using 3 choices, with “happiness” being the highest level of satisfaction, followed by “neutral” and “unhappy.” At 24 months, the number of women indicating happiness was similar among the 3 study groups: 71.4% for the LARC randomized group, 75.0% for the randomized SARC group, and 77.6% for the preferred SARC cohort group.

Among women who discontinued their LARC method, occurrence of adverse effects was the reason given 74.2% of the time, while among SARC method users in both groups there was no dominant reason for discontinuation. Also, among women who discontinued their method, the percentage indicating happiness was 32.2% for the LARC randomized group compared with 69.9% and 68.2% for the randomized and preference cohort SARC groups, respectively.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study had several strengths. The population from which the study groups were obtained was demographically diverse and was appropriate for determining if women with reservations about LARC methods could have satisfactory outcomes similar to women who self-select LARC methods. Further, the 24 months of observations indicate that, for the most part, satisfaction persisted.

One of the study’s shortcomings is the limited data on the subsets, that is, the specific method chosen, within each of the study groups.

-- Ronald T. Burkman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Foster DG, Barar R, Gould H, et al. Projections and opinions from 100 experts in long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2015;92:543-552.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Because of women’s personal preference and aversion, for various reasons, to LARC methods, the current estimated use rate of 17% for LARC methods would increase only to 24% to 29% even if major barriers, such as cost and availability, were removed.1 To gain more insight into this issue, Hubacher and colleagues sought to determine if LARC methods would meet the contraceptive needs and be acceptable to a population of women who were not seeking these methods actively and who might have some reservation about using them.

Details of the study

The authors approached women actively seeking 1 of the 2 SARC methods but not a LARC method for contraception. They enrolled 524 women into a cohort study in which they received their desired SARC method. In addition, 392 women agreed to be enrolled in a randomized clinical trial comparing women beginning a LARC method for the first time with a group receiving 1 of the 2 SARC methods.

Importance of covered costs. Of note, the women in the randomized trial had the costs of the insertion or removal of the LARC method covered; those randomly assigned to the comparative SARC arm had the costs of their oral contraceptives (OCs) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) covered for the first year of use. Underwriting the costs in the randomized study was likely important for study recruitment, since 47% of participants who were randomized to the LARC group cited cost as one of the reasons they did not try a LARC method previously.

Satisfaction with contraceptive method. In addition to the differences in continuation rates and pregnancy rates noted, it is interesting that, among women who tried a LARC method and who had some persistent negative feelings about the method, 65.9% would try the method again.

Satisfaction levels were estimated using 3 choices, with “happiness” being the highest level of satisfaction, followed by “neutral” and “unhappy.” At 24 months, the number of women indicating happiness was similar among the 3 study groups: 71.4% for the LARC randomized group, 75.0% for the randomized SARC group, and 77.6% for the preferred SARC cohort group.

Among women who discontinued their LARC method, occurrence of adverse effects was the reason given 74.2% of the time, while among SARC method users in both groups there was no dominant reason for discontinuation. Also, among women who discontinued their method, the percentage indicating happiness was 32.2% for the LARC randomized group compared with 69.9% and 68.2% for the randomized and preference cohort SARC groups, respectively.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study had several strengths. The population from which the study groups were obtained was demographically diverse and was appropriate for determining if women with reservations about LARC methods could have satisfactory outcomes similar to women who self-select LARC methods. Further, the 24 months of observations indicate that, for the most part, satisfaction persisted.

One of the study’s shortcomings is the limited data on the subsets, that is, the specific method chosen, within each of the study groups.

-- Ronald T. Burkman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Because of women’s personal preference and aversion, for various reasons, to LARC methods, the current estimated use rate of 17% for LARC methods would increase only to 24% to 29% even if major barriers, such as cost and availability, were removed.1 To gain more insight into this issue, Hubacher and colleagues sought to determine if LARC methods would meet the contraceptive needs and be acceptable to a population of women who were not seeking these methods actively and who might have some reservation about using them.

Details of the study

The authors approached women actively seeking 1 of the 2 SARC methods but not a LARC method for contraception. They enrolled 524 women into a cohort study in which they received their desired SARC method. In addition, 392 women agreed to be enrolled in a randomized clinical trial comparing women beginning a LARC method for the first time with a group receiving 1 of the 2 SARC methods.

Importance of covered costs. Of note, the women in the randomized trial had the costs of the insertion or removal of the LARC method covered; those randomly assigned to the comparative SARC arm had the costs of their oral contraceptives (OCs) or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) covered for the first year of use. Underwriting the costs in the randomized study was likely important for study recruitment, since 47% of participants who were randomized to the LARC group cited cost as one of the reasons they did not try a LARC method previously.

Satisfaction with contraceptive method. In addition to the differences in continuation rates and pregnancy rates noted, it is interesting that, among women who tried a LARC method and who had some persistent negative feelings about the method, 65.9% would try the method again.

Satisfaction levels were estimated using 3 choices, with “happiness” being the highest level of satisfaction, followed by “neutral” and “unhappy.” At 24 months, the number of women indicating happiness was similar among the 3 study groups: 71.4% for the LARC randomized group, 75.0% for the randomized SARC group, and 77.6% for the preferred SARC cohort group.

Among women who discontinued their LARC method, occurrence of adverse effects was the reason given 74.2% of the time, while among SARC method users in both groups there was no dominant reason for discontinuation. Also, among women who discontinued their method, the percentage indicating happiness was 32.2% for the LARC randomized group compared with 69.9% and 68.2% for the randomized and preference cohort SARC groups, respectively.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study had several strengths. The population from which the study groups were obtained was demographically diverse and was appropriate for determining if women with reservations about LARC methods could have satisfactory outcomes similar to women who self-select LARC methods. Further, the 24 months of observations indicate that, for the most part, satisfaction persisted.

One of the study’s shortcomings is the limited data on the subsets, that is, the specific method chosen, within each of the study groups.

-- Ronald T. Burkman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Foster DG, Barar R, Gould H, et al. Projections and opinions from 100 experts in long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2015;92:543-552.

- Foster DG, Barar R, Gould H, et al. Projections and opinions from 100 experts in long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2015;92:543-552.

Should return to fertility be a concern for nulliparous patients using an IUD?

Investigators from the University of Texas Southwestern are dispelling the myth that you shouldn’t recommend intrauterine devices (IUDs) for nulliparous women because the devices might make it more difficult for them to become pregnant after discontinuation. They found that nulliparous women can just as easily get pregnant after using a progestin intrauterine system (IUS) as parous women,1 according to results of a study presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6–10, Denver, Colorado).

Bruce R. Carr, MD, lead investigator of the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “There have been a number of studies—maybe 10 to 15 years ago—that looked at pregnancy rates when patients stopped using IUDs, but most of these studies were done in women who were multiparous. There is almost no data on patients who are nulliparous stopping an IUD and trying to get pregnant.”

Participants and methods. This prospective, multicenter, clinical trial, which is still ongoing, is evaluating the efficacy and safety for up to 10 years of the Liletta levonorgestrel 52-mg IUS in nulliparous and parous women ages 16 to 45 years. Every 3 months for up to 1 year, the investigators contacted the women who discontinued the IUS during the first 5 years of use and who were trying to become pregnant to determine pregnancy status.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was time to pregnancy among nulliparous vs parous women after discontinuation of a progestin IUS.

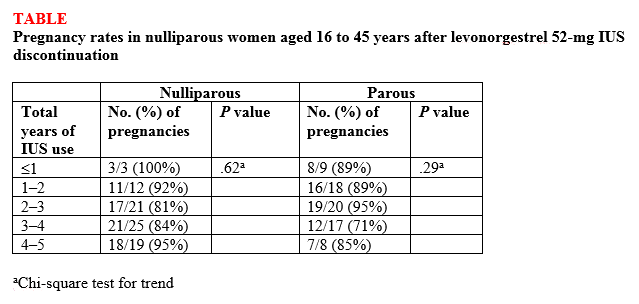

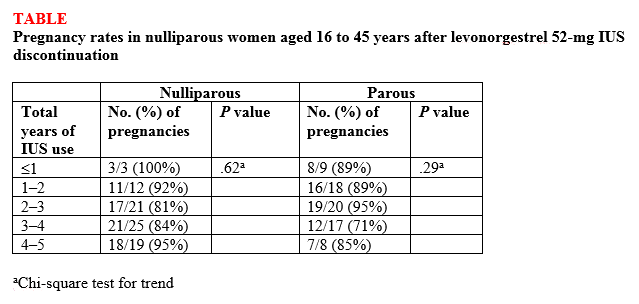

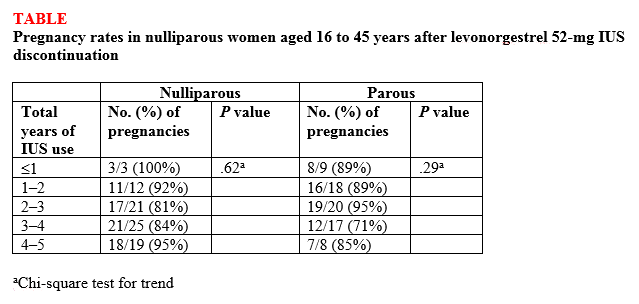

Findings. Overall, 132 (87%) of 152 women ages 16 to 35 years at the beginning of the study who attempted to become pregnant did so within 1 year of discontinuing the IUS, and there was no difference in pregnancy rates between nulliparous and parous women (87.5% vs 86.1%, respectively; P<.82) or between nulligravid and gravid women (88.2% vs 85.7%, respectively; P<.81). High percentages of women became pregnant by the end of 3 months (43.4%) and 6 months (69.7%), with a median time to conception of 91.5 days. The women used the IUS for a median of 34 months before discontinuation. Length of IUS use and age of the women at IUS discontinuation did not affect pregnancy rates at 12 months postdiscontinuation in either nulliparous or parous women (TABLE).1

“The bottom line,” according to Dr. Carr, is that the “pregnancy rates were the same in women who had never been pregnant compared with women who had previously been pregnant.” He continued, “People worried that if a patient who had never been pregnant used an IUD that maybe she was going to have a harder time getting pregnant after discontinuing, and now we know that is not true. It [the study] reinforces the option of using progestin IUDs and not having to worry about future pregnancy.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This article was updated October 15, 2018.

- Carr BR, Thomas MA, Gangestad A, Eisenberg DL, Olariu AI, Creinin MD. Return of fertility in nulliparous and parous women after levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system discontinuation [ASRM abstract O-104]. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e46.

Investigators from the University of Texas Southwestern are dispelling the myth that you shouldn’t recommend intrauterine devices (IUDs) for nulliparous women because the devices might make it more difficult for them to become pregnant after discontinuation. They found that nulliparous women can just as easily get pregnant after using a progestin intrauterine system (IUS) as parous women,1 according to results of a study presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6–10, Denver, Colorado).

Bruce R. Carr, MD, lead investigator of the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “There have been a number of studies—maybe 10 to 15 years ago—that looked at pregnancy rates when patients stopped using IUDs, but most of these studies were done in women who were multiparous. There is almost no data on patients who are nulliparous stopping an IUD and trying to get pregnant.”

Participants and methods. This prospective, multicenter, clinical trial, which is still ongoing, is evaluating the efficacy and safety for up to 10 years of the Liletta levonorgestrel 52-mg IUS in nulliparous and parous women ages 16 to 45 years. Every 3 months for up to 1 year, the investigators contacted the women who discontinued the IUS during the first 5 years of use and who were trying to become pregnant to determine pregnancy status.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was time to pregnancy among nulliparous vs parous women after discontinuation of a progestin IUS.

Findings. Overall, 132 (87%) of 152 women ages 16 to 35 years at the beginning of the study who attempted to become pregnant did so within 1 year of discontinuing the IUS, and there was no difference in pregnancy rates between nulliparous and parous women (87.5% vs 86.1%, respectively; P<.82) or between nulligravid and gravid women (88.2% vs 85.7%, respectively; P<.81). High percentages of women became pregnant by the end of 3 months (43.4%) and 6 months (69.7%), with a median time to conception of 91.5 days. The women used the IUS for a median of 34 months before discontinuation. Length of IUS use and age of the women at IUS discontinuation did not affect pregnancy rates at 12 months postdiscontinuation in either nulliparous or parous women (TABLE).1

“The bottom line,” according to Dr. Carr, is that the “pregnancy rates were the same in women who had never been pregnant compared with women who had previously been pregnant.” He continued, “People worried that if a patient who had never been pregnant used an IUD that maybe she was going to have a harder time getting pregnant after discontinuing, and now we know that is not true. It [the study] reinforces the option of using progestin IUDs and not having to worry about future pregnancy.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This article was updated October 15, 2018.

Investigators from the University of Texas Southwestern are dispelling the myth that you shouldn’t recommend intrauterine devices (IUDs) for nulliparous women because the devices might make it more difficult for them to become pregnant after discontinuation. They found that nulliparous women can just as easily get pregnant after using a progestin intrauterine system (IUS) as parous women,1 according to results of a study presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6–10, Denver, Colorado).

Bruce R. Carr, MD, lead investigator of the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “There have been a number of studies—maybe 10 to 15 years ago—that looked at pregnancy rates when patients stopped using IUDs, but most of these studies were done in women who were multiparous. There is almost no data on patients who are nulliparous stopping an IUD and trying to get pregnant.”

Participants and methods. This prospective, multicenter, clinical trial, which is still ongoing, is evaluating the efficacy and safety for up to 10 years of the Liletta levonorgestrel 52-mg IUS in nulliparous and parous women ages 16 to 45 years. Every 3 months for up to 1 year, the investigators contacted the women who discontinued the IUS during the first 5 years of use and who were trying to become pregnant to determine pregnancy status.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was time to pregnancy among nulliparous vs parous women after discontinuation of a progestin IUS.

Findings. Overall, 132 (87%) of 152 women ages 16 to 35 years at the beginning of the study who attempted to become pregnant did so within 1 year of discontinuing the IUS, and there was no difference in pregnancy rates between nulliparous and parous women (87.5% vs 86.1%, respectively; P<.82) or between nulligravid and gravid women (88.2% vs 85.7%, respectively; P<.81). High percentages of women became pregnant by the end of 3 months (43.4%) and 6 months (69.7%), with a median time to conception of 91.5 days. The women used the IUS for a median of 34 months before discontinuation. Length of IUS use and age of the women at IUS discontinuation did not affect pregnancy rates at 12 months postdiscontinuation in either nulliparous or parous women (TABLE).1

“The bottom line,” according to Dr. Carr, is that the “pregnancy rates were the same in women who had never been pregnant compared with women who had previously been pregnant.” He continued, “People worried that if a patient who had never been pregnant used an IUD that maybe she was going to have a harder time getting pregnant after discontinuing, and now we know that is not true. It [the study] reinforces the option of using progestin IUDs and not having to worry about future pregnancy.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This article was updated October 15, 2018.

- Carr BR, Thomas MA, Gangestad A, Eisenberg DL, Olariu AI, Creinin MD. Return of fertility in nulliparous and parous women after levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system discontinuation [ASRM abstract O-104]. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e46.

- Carr BR, Thomas MA, Gangestad A, Eisenberg DL, Olariu AI, Creinin MD. Return of fertility in nulliparous and parous women after levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system discontinuation [ASRM abstract O-104]. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e46.

Abortion, the travel ban, and other top Supreme Court rulings affecting your practice

The 2017−2018 term of the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) was momentous. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who had been the deciding vote in most of the 5 to 4 cases for a generation, announced his retirement as of July 31, 2018. In addition, the Court decided a number of cases of interest to ObGyns. In this article we review some of those cases, as well as consider the future of the Court without Justice Kennedy. In selecting cases, we have given special attention to those in which national medical organizations filed amicus briefs. These “amicus curiae” or “friend of the court” briefs are filed by an entity who is not party to a case but wants to provide information or views to the court.

1. Abortion rulings

The Court decided 2 abortion cases and rejected a request to hear a third.

National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v Becerra

In this case,1 the Court struck down a California law that required pregnancy crisis centers not offering abortions (generally operated by pro-life groups) to provide special notices to clients.2

At stake. These notices would inform clients that California provides free or low-cost services, including abortions, and provide a phone number to call for those services.

There were many amicus briefs filed in this case, including those by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and other specialty boards,3 as well as the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists and other pro-life organizations.4 ACOG’s brief argued that the California-required notice facilitates the goal of allowing women to receive medical services without harmful delay.

Final ruling. The Court held that the law required clinics to engage in speech with which the clinics disagreed (known as “compelled speech”). It also noted that California disclosure requirements were “wildly underinclusive” because they apply only to some clinics. The majority felt that there was no strong state interest in compelling this speech because there were other alternatives for the state to provide information about the availability of abortion and other services. The Court found that the clinics were likely to succeed on the merits of their claims of a First Amendment (free speech) violation.

Right to abortion for illegal immigrants in custody

A very unusual abortion case involved “Jane Doe,” a minor who was at 8 weeks’ gestation when she illegally crossed the border into the United States.5 She was placed in a federally-funded shelter where she requested an abortion. The facility denied that request.

At stake. Legal argument ensued about releasing her to another facility for an abortion, as the argument was made that pregnant minors who are apprehended crossing into the United States illegally and placed into the custody of federal officials should have abortion access. A lower Court of Appeals ruled against the Trump Administration’s policy of denying abortions to undocumented minors in federal custody. During the process of the federal government taking the case to the Supreme Court, the attorneys for Doe moved appointments around and, without notice, the abortion was performed. Government attorneys said that Doe’s attorneys made “what appear to be material misrepresentations and omissions” designed to “thwart [the Supreme Court’s] review” of the case.5 The government requested that the Court vacate the order of the Court of Appeals so that it could not be used as precedent.

Final ruling. The Court granted the governments request to vacate the lower court’s order because the minor was no longer pregnant and the order was therefore moot. The basic issue in this case (the right of in-custody minors to access abortions) remains unresolved. It is likely to appear before the Court in the future.

Continue to: Access to medical abortions

Access to medical abortions

An Arkansas law requires that a physician administering medical abortions contract with a physician who has admitting privileges at a hospital (a “contracted physician”).

At stake. Planned Parenthood filed suit challenging the requirement as unnecessary and harmful because it would result in the closure of 2 of the 3 abortion providers in Arkansas. ACOG filed an amicus brief urging the Supreme Court to consider the case.6 (Technically this was a petition for a Writ of Certiorari, the procedure by which the Court accepts cases. It accepts only about 1% of applications.) ACOG argued that there was no medical reason for the contracted physician requirement, and noted the harm it would do to women who would not have access to abortions.

Final ruling. On May 29, 2018, the Court declined to hear the case. This case is still active in the lower courts and may eventually return to the Supreme Court.

2. The patent system

The medical profession depends on the patent system to encourage the discovery of new patents efficiently and effectively. In 2012, Congress passed the America Invents Act7 that authorizes a petition by anyone other than the patent holder to the Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) for an “inter partes review” to assess a challenge to the patent’s legitimacy. If the PTO determines that there may be merit to the claim, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board undertakes a trial-like review process that may validate, invalidate, or amend the patent. The Board’s decision is subject to appellate court review.

At stake. This term, the inter partes review was challenged as unconstitutional on technical bases.8

Final ruling. The Court rejected this claim and approved the current administrative inter partes review process. The Court determined that once the Patent Office takes a petition challenging a patent, it must decide all of the claims against the patent, not pick and choose which elements of the challenge to evaluate.9 The Court’s decision upheld patent-review reform, but will require the Patent Office to tweak its procedures.

3. The travel ban

ACOG, the American Medical Association (AMA), the Association of American Medical Colleges, and more than 30 other health care and specialty associations filed an amicus brief regarding one of the most anticipated cases of the term—the “travel ban.”10

At stake. The essential argument of these organizations was that the US health care system depends on professionals from other countries. An efficient and fair immigration program is, therefore, important to advance the nation’s “health security.” During the 2016−2017 term, the Court considered but then removed the issue from its calendar when the Trump Administration issued a revised travel ban.11

In September 2017, President Trump’s proclamation imposed a range of entry restrictions on the citizens of 8 countries, most (but not all) of which are predominantly Muslim. The government indicated that, in a study by Homeland Security and the State Department, these countries were identified as having especially deficient information-sharing practices and presented national security concerns. Trump v Hawaii12 challenged this proclamation.

Final ruling. The majority of the Court upheld the travel ban. For the 5-Justice majority led by Chief Justice Roberts, the case came down to 3 things:

- The Constitution and the laws passed by Congress of necessity give the President great authority to engage in foreign policy, including policies regarding entry into the country.

- The courts are very reluctant to get into the substance of foreign affairs—they are not equipped to know in detail what the facts are, and things change very fast.

- If courts start tinkering with foreign policy and things turn bad, it will appear that the courts are to blame and were interfering in an area about which they are not competent.

Continue to: 4. Did a credit card case add risk to health insurance markets?

It was just a credit card case, but one in which the AMA saw a real risk to regulation of the health insurance markets.

At stake. Technically, Ohio v American Express concerned a claim that American Express (AmEx) violated antitrust laws when it prohibited merchants taking its credit card from “steering” customers to cards with lower fees.13 AmEx maintained that, because credit cards were a special kind of “2-sided” market (connecting merchants on one side and customers on the other), antitrust laws should not be strictly enforced.

The AMA noticed that special rules regarding 2-sided markets might apply to health insurance, and it submitted an amicus brief14 that noted: “dominant health insurance networks … have imposed and could further impose rules or effectively erect barriers that prohibit physicians from referring patients to certain specialists, particularly out-of-network specialists, for innovative and even necessary medical tests.”14 It concluded that the antitrust rule AmEx was suggesting would make it nearly impossible to challenge these unfair provisions in health insurance arrangements.

Final ruling. The Court, however, accepted the AmEx position, making it very difficult to develop an antitrust case against 2-sided markets. It remains to be seen the degree to which the AMA concern about health insurance markets will be realized.

5. Gay wedding and a bakeshop

At stake. In Masterpiece Cakeshop v Colorado, a cakemaker declined to design a cake for a gay wedding and had been disciplined under Colorado law for discriminating against the couple based on sexual orientation.15

Final ruling. The Court, however, found that the Colorado regulators had, ironically, shown such religious animus in the way they treated the baker that the regulators themselves had discriminated on the basis of religion. As a result, the Court reversed the sanctions against the baker.

This decision was fairly narrow. It does not, for example, stand for the proposition that there may be a general religious exception to antidiscrimination laws. The question of broader religious or free-speech objections to antidiscrimination laws remains for another time.

Amicus brief. It was interesting that the American College of Pediatricians, American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and others, filed an amicus brief to report with concern the “demands that individual medical professionals must perform, assist with, or facilitate abortions, without regard to the teachings of their own faiths, consciences, and convictions.”16 The brief also noted that “issues in the present case implicate the fundamental rights of health care professionals, and to respectfully urge that the Court should by no means permit any weakening or qualification of well-established protections against compelled speech, and of free exercise” of religion.16

Arbitration. The Court upheld, as it has in most recent terms, another arbitration agreement.1 This case concerned an employment agreement in which employees consented to submit to arbitration rather than file lawsuits and not use class action claims.

Search of cell-phone location. Cell phones, whenever turned on, connect with cell towers that record the phone’s location several times a minute. Cell companies store this information, creating a virtual map of where the owner is at all times. The Federal Bureau of Investigation asked a cell company for location information for several people during a 127-day period in which robberies were committed.2 The Court held that the search was illegal in the absence of a warrant.

Public employee unions. The Court held that agency (fair share) fees, in which public employees who are not union members can be required to pay dues for the bargaining and grievance activities (from which they generally benefit), violate the First Amendment. The majority held that forcing public employees to pay fees to unions requires the employees, through those fees, to engage in political activities with which they disagree.3 This is a form of compelled speech, which the Court found violates the First Amendment. Health care professionals who are public employees in positions that have union representation will probably have the opportunity to opt out of agency agreements.

Internet sales tax. The Court permitted states to charge sales tax on out-of-state Internet purchases.4 In doing so, a state may require out-of-state companies to collect taxes on sales to its residents.

References

- Epic Systems Corp. v Lewis, 584 US 16 285 (2018).

- Carpenter v United States, 585 US 16 402 (2018).

- Janus v State, County, and Municipal Employees, 585 US 16 1466 (2018).

- South Dakota v Wayfair, Inc, 585 US 17 494 (2018).

Clues to the future

During the term that ran from October 2, 2017, through June 27, 2018, the Court issued 72 decisions. An unusually high proportion of cases (26%; 19 cases) were decided on a 5 to 4 vote. Last term, the rate of 5 to 4 decisions was 10%; the 6-year average was 18%. The unanimous decision rate was 39% this term, compared with 59% last term, and 50% on average.

The rate of 5 to 4 cases provides a clue about the Court’s general direction. The number of times each Justice was in the majority in those nineteen 5 to 4 decisions included: Chief Justice Roberts, 17; and Justices Kennedy, 16; Gorsuch, 16; Thomas, 15; and Alito, 15; compared with Justices Ginsburg, 5; Breyer, 4; Sotomayor, 4; and Kagan, 3.

The Court convened on October 1, 2018. At this writing, whether the new term starts with 8 or 9 justices remains a question. President Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh, JD, to take Justice Kennedy’s place on the Court. His professional qualifications and experience appear to make him qualified for a position on the Court, but as we have seen, there are many other elements that go into confirming a Justice’s nomination.

Justice Anthony Kennedy was the deciding vote in the overwhelming majority of the 5 to 4 decisions in 20 of his 30 years on the Court. The areas in which he had an especially important impact include1:

- Gay rights. Justice Kennedy wrote the opinions (usually 5 to 4 decisions) in a number of groundbreaking gay-rights cases, including decriminalizing homosexual conduct, striking down the Defense of Marriage Act, and finding that the Constitution requires states to recognize gay marriage.

- The death penalty. Justice Kennedy wrote decisions that prohibited states from imposing the death penalty for any crime other than murder, for defendants who were under 18 when they committed the crime, and for defendants with serious developmental disabilities. He expressed reservations about long-term solitary confinement, but did not have a case that allowed him to decide its constitutionality.

- The First Amendment. Early in his service on the Court, he held that the First Amendment protected flag burning as a form of speech. He decided many important freespeech and freedom-of-religion cases that have set a standard for protecting those fundamental freedoms.

- Use of health and social science data. Justice Kennedy was more open to mental health information and cited it more often than most other Justices.

- Abortion rights? Many commentators would add protecting the right to choose to have an abortion to the above list. Justice Kennedy was a central figure in one case that declined to back away from Roe v Wade, and joined a more recent decision that struck down a Texas law that created an undue burden on women seeking abortion. Plus, he also voted to uphold abortion restrictions, such as “partial-birth-abortion laws.” So there is a good argument for including abortion rights on the list, although he did not break new ground.

Justice Kennedy as a person

Outside the courtroom, Justice Kennedy is a person of great warmth and compassion. He is a natural teacher and spends a great deal of time with students. When asked how he would like to be remembered, Justice Kennedy once replied, “Somebody who’s decent, and honest, and fair, and who’s absolutely committed to the proposition that freedom is America’s gift to the rest of the world.” I agree with that assessment.

STEVEN R. SMITH, MS, JD

Reference

- South Dakota v Wayfair, Inc, 585 US (2018)

Next term, the Court is scheduled to hear cases regarding pharmaceutical liability, double jeopardy, sex-offender registration, expert witnesses, Social Security disability benefits, and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act. There will be at least 3 arbitration cases. Health care and reproductive rights will continue to be an important part of the Court’s docket.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v Becerra, 585 US 16 1140 (2018).

- California Reproductive Freedom, Accountability, Comprehensive Care, and Transparency Act (FACT Act), Cal. Health & Safety Code Ann. §123470 et seq. (West 2018).

- Brief amici curiae of American Academy of Pediatrics, et al. in National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v Becerra, February 27, 2018.

- Brief amici curiae of American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians & Gynecologists, et al. in National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v Becerra, January 16, 2018.

- Azar v Garza, 584 US 17 654 (2018).

- Brief amici curiae of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Public Health Association in Planned Parenthood of Arkansas and Eastern Oklahoma v Jegley, February 1, 2018.

- Chapter 31, Inter Partes Review. United States Code. Title 35: Patents. Part III, Patents and protection of patents. 2012 Ed. 35 USC 311–319.

- Oil States Energy Services, LLC v Greene’s Energy Group, LLC, 584 US 16 712 (2018).

- SAS Institute Inc. v Iancu, 584 US 16 969 (2018).

- Brief for Association of American Medical Colleges and Others as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondents, Trump v Hawaii. https://www.supremecourt.gov/Docket PDF/17/ 17-965/40128/20180327105855912_17-965%20Amicus%20Br.%20Proclamation.pdf. Accessed September 21, 2018.

- Smith SR, Sanfilippo JS. Supreme Court decisions in 2017 that affected your practice. OBG Manag. 2017;29(12)44–47.

- Trump v Hawaii, 585 US 17 965 (2018).

- Ohio v American Express Co, 585 US 16 1454 (2018).

- Brief amici curiae of American Medical Association and Ohio State Medical Association in Ohio v American Express, December 24, 2017.

- Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v Colorado Civil Rights Commission, 584 US 16 111 (2018).

- Brief amici curiae of American College of Pediatricians, et al. in Masterpiece Cakeshop v Colorado Civil Rights Commission, September 7, 2017.

The 2017−2018 term of the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) was momentous. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who had been the deciding vote in most of the 5 to 4 cases for a generation, announced his retirement as of July 31, 2018. In addition, the Court decided a number of cases of interest to ObGyns. In this article we review some of those cases, as well as consider the future of the Court without Justice Kennedy. In selecting cases, we have given special attention to those in which national medical organizations filed amicus briefs. These “amicus curiae” or “friend of the court” briefs are filed by an entity who is not party to a case but wants to provide information or views to the court.

1. Abortion rulings

The Court decided 2 abortion cases and rejected a request to hear a third.

National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v Becerra

In this case,1 the Court struck down a California law that required pregnancy crisis centers not offering abortions (generally operated by pro-life groups) to provide special notices to clients.2

At stake. These notices would inform clients that California provides free or low-cost services, including abortions, and provide a phone number to call for those services.

There were many amicus briefs filed in this case, including those by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and other specialty boards,3 as well as the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists and other pro-life organizations.4 ACOG’s brief argued that the California-required notice facilitates the goal of allowing women to receive medical services without harmful delay.

Final ruling. The Court held that the law required clinics to engage in speech with which the clinics disagreed (known as “compelled speech”). It also noted that California disclosure requirements were “wildly underinclusive” because they apply only to some clinics. The majority felt that there was no strong state interest in compelling this speech because there were other alternatives for the state to provide information about the availability of abortion and other services. The Court found that the clinics were likely to succeed on the merits of their claims of a First Amendment (free speech) violation.

Right to abortion for illegal immigrants in custody

A very unusual abortion case involved “Jane Doe,” a minor who was at 8 weeks’ gestation when she illegally crossed the border into the United States.5 She was placed in a federally-funded shelter where she requested an abortion. The facility denied that request.

At stake. Legal argument ensued about releasing her to another facility for an abortion, as the argument was made that pregnant minors who are apprehended crossing into the United States illegally and placed into the custody of federal officials should have abortion access. A lower Court of Appeals ruled against the Trump Administration’s policy of denying abortions to undocumented minors in federal custody. During the process of the federal government taking the case to the Supreme Court, the attorneys for Doe moved appointments around and, without notice, the abortion was performed. Government attorneys said that Doe’s attorneys made “what appear to be material misrepresentations and omissions” designed to “thwart [the Supreme Court’s] review” of the case.5 The government requested that the Court vacate the order of the Court of Appeals so that it could not be used as precedent.

Final ruling. The Court granted the governments request to vacate the lower court’s order because the minor was no longer pregnant and the order was therefore moot. The basic issue in this case (the right of in-custody minors to access abortions) remains unresolved. It is likely to appear before the Court in the future.

Continue to: Access to medical abortions

Access to medical abortions

An Arkansas law requires that a physician administering medical abortions contract with a physician who has admitting privileges at a hospital (a “contracted physician”).

At stake. Planned Parenthood filed suit challenging the requirement as unnecessary and harmful because it would result in the closure of 2 of the 3 abortion providers in Arkansas. ACOG filed an amicus brief urging the Supreme Court to consider the case.6 (Technically this was a petition for a Writ of Certiorari, the procedure by which the Court accepts cases. It accepts only about 1% of applications.) ACOG argued that there was no medical reason for the contracted physician requirement, and noted the harm it would do to women who would not have access to abortions.

Final ruling. On May 29, 2018, the Court declined to hear the case. This case is still active in the lower courts and may eventually return to the Supreme Court.

2. The patent system

The medical profession depends on the patent system to encourage the discovery of new patents efficiently and effectively. In 2012, Congress passed the America Invents Act7 that authorizes a petition by anyone other than the patent holder to the Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) for an “inter partes review” to assess a challenge to the patent’s legitimacy. If the PTO determines that there may be merit to the claim, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board undertakes a trial-like review process that may validate, invalidate, or amend the patent. The Board’s decision is subject to appellate court review.

At stake. This term, the inter partes review was challenged as unconstitutional on technical bases.8

Final ruling. The Court rejected this claim and approved the current administrative inter partes review process. The Court determined that once the Patent Office takes a petition challenging a patent, it must decide all of the claims against the patent, not pick and choose which elements of the challenge to evaluate.9 The Court’s decision upheld patent-review reform, but will require the Patent Office to tweak its procedures.

3. The travel ban

ACOG, the American Medical Association (AMA), the Association of American Medical Colleges, and more than 30 other health care and specialty associations filed an amicus brief regarding one of the most anticipated cases of the term—the “travel ban.”10

At stake. The essential argument of these organizations was that the US health care system depends on professionals from other countries. An efficient and fair immigration program is, therefore, important to advance the nation’s “health security.” During the 2016−2017 term, the Court considered but then removed the issue from its calendar when the Trump Administration issued a revised travel ban.11

In September 2017, President Trump’s proclamation imposed a range of entry restrictions on the citizens of 8 countries, most (but not all) of which are predominantly Muslim. The government indicated that, in a study by Homeland Security and the State Department, these countries were identified as having especially deficient information-sharing practices and presented national security concerns. Trump v Hawaii12 challenged this proclamation.

Final ruling. The majority of the Court upheld the travel ban. For the 5-Justice majority led by Chief Justice Roberts, the case came down to 3 things:

- The Constitution and the laws passed by Congress of necessity give the President great authority to engage in foreign policy, including policies regarding entry into the country.

- The courts are very reluctant to get into the substance of foreign affairs—they are not equipped to know in detail what the facts are, and things change very fast.

- If courts start tinkering with foreign policy and things turn bad, it will appear that the courts are to blame and were interfering in an area about which they are not competent.

Continue to: 4. Did a credit card case add risk to health insurance markets?

It was just a credit card case, but one in which the AMA saw a real risk to regulation of the health insurance markets.

At stake. Technically, Ohio v American Express concerned a claim that American Express (AmEx) violated antitrust laws when it prohibited merchants taking its credit card from “steering” customers to cards with lower fees.13 AmEx maintained that, because credit cards were a special kind of “2-sided” market (connecting merchants on one side and customers on the other), antitrust laws should not be strictly enforced.

The AMA noticed that special rules regarding 2-sided markets might apply to health insurance, and it submitted an amicus brief14 that noted: “dominant health insurance networks … have imposed and could further impose rules or effectively erect barriers that prohibit physicians from referring patients to certain specialists, particularly out-of-network specialists, for innovative and even necessary medical tests.”14 It concluded that the antitrust rule AmEx was suggesting would make it nearly impossible to challenge these unfair provisions in health insurance arrangements.

Final ruling. The Court, however, accepted the AmEx position, making it very difficult to develop an antitrust case against 2-sided markets. It remains to be seen the degree to which the AMA concern about health insurance markets will be realized.

5. Gay wedding and a bakeshop

At stake. In Masterpiece Cakeshop v Colorado, a cakemaker declined to design a cake for a gay wedding and had been disciplined under Colorado law for discriminating against the couple based on sexual orientation.15

Final ruling. The Court, however, found that the Colorado regulators had, ironically, shown such religious animus in the way they treated the baker that the regulators themselves had discriminated on the basis of religion. As a result, the Court reversed the sanctions against the baker.

This decision was fairly narrow. It does not, for example, stand for the proposition that there may be a general religious exception to antidiscrimination laws. The question of broader religious or free-speech objections to antidiscrimination laws remains for another time.

Amicus brief. It was interesting that the American College of Pediatricians, American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and others, filed an amicus brief to report with concern the “demands that individual medical professionals must perform, assist with, or facilitate abortions, without regard to the teachings of their own faiths, consciences, and convictions.”16 The brief also noted that “issues in the present case implicate the fundamental rights of health care professionals, and to respectfully urge that the Court should by no means permit any weakening or qualification of well-established protections against compelled speech, and of free exercise” of religion.16

Arbitration. The Court upheld, as it has in most recent terms, another arbitration agreement.1 This case concerned an employment agreement in which employees consented to submit to arbitration rather than file lawsuits and not use class action claims.

Search of cell-phone location. Cell phones, whenever turned on, connect with cell towers that record the phone’s location several times a minute. Cell companies store this information, creating a virtual map of where the owner is at all times. The Federal Bureau of Investigation asked a cell company for location information for several people during a 127-day period in which robberies were committed.2 The Court held that the search was illegal in the absence of a warrant.

Public employee unions. The Court held that agency (fair share) fees, in which public employees who are not union members can be required to pay dues for the bargaining and grievance activities (from which they generally benefit), violate the First Amendment. The majority held that forcing public employees to pay fees to unions requires the employees, through those fees, to engage in political activities with which they disagree.3 This is a form of compelled speech, which the Court found violates the First Amendment. Health care professionals who are public employees in positions that have union representation will probably have the opportunity to opt out of agency agreements.

Internet sales tax. The Court permitted states to charge sales tax on out-of-state Internet purchases.4 In doing so, a state may require out-of-state companies to collect taxes on sales to its residents.

References

- Epic Systems Corp. v Lewis, 584 US 16 285 (2018).

- Carpenter v United States, 585 US 16 402 (2018).

- Janus v State, County, and Municipal Employees, 585 US 16 1466 (2018).

- South Dakota v Wayfair, Inc, 585 US 17 494 (2018).

Clues to the future

During the term that ran from October 2, 2017, through June 27, 2018, the Court issued 72 decisions. An unusually high proportion of cases (26%; 19 cases) were decided on a 5 to 4 vote. Last term, the rate of 5 to 4 decisions was 10%; the 6-year average was 18%. The unanimous decision rate was 39% this term, compared with 59% last term, and 50% on average.

The rate of 5 to 4 cases provides a clue about the Court’s general direction. The number of times each Justice was in the majority in those nineteen 5 to 4 decisions included: Chief Justice Roberts, 17; and Justices Kennedy, 16; Gorsuch, 16; Thomas, 15; and Alito, 15; compared with Justices Ginsburg, 5; Breyer, 4; Sotomayor, 4; and Kagan, 3.

The Court convened on October 1, 2018. At this writing, whether the new term starts with 8 or 9 justices remains a question. President Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh, JD, to take Justice Kennedy’s place on the Court. His professional qualifications and experience appear to make him qualified for a position on the Court, but as we have seen, there are many other elements that go into confirming a Justice’s nomination.

Justice Anthony Kennedy was the deciding vote in the overwhelming majority of the 5 to 4 decisions in 20 of his 30 years on the Court. The areas in which he had an especially important impact include1:

- Gay rights. Justice Kennedy wrote the opinions (usually 5 to 4 decisions) in a number of groundbreaking gay-rights cases, including decriminalizing homosexual conduct, striking down the Defense of Marriage Act, and finding that the Constitution requires states to recognize gay marriage.

- The death penalty. Justice Kennedy wrote decisions that prohibited states from imposing the death penalty for any crime other than murder, for defendants who were under 18 when they committed the crime, and for defendants with serious developmental disabilities. He expressed reservations about long-term solitary confinement, but did not have a case that allowed him to decide its constitutionality.

- The First Amendment. Early in his service on the Court, he held that the First Amendment protected flag burning as a form of speech. He decided many important freespeech and freedom-of-religion cases that have set a standard for protecting those fundamental freedoms.

- Use of health and social science data. Justice Kennedy was more open to mental health information and cited it more often than most other Justices.

- Abortion rights? Many commentators would add protecting the right to choose to have an abortion to the above list. Justice Kennedy was a central figure in one case that declined to back away from Roe v Wade, and joined a more recent decision that struck down a Texas law that created an undue burden on women seeking abortion. Plus, he also voted to uphold abortion restrictions, such as “partial-birth-abortion laws.” So there is a good argument for including abortion rights on the list, although he did not break new ground.

Justice Kennedy as a person

Outside the courtroom, Justice Kennedy is a person of great warmth and compassion. He is a natural teacher and spends a great deal of time with students. When asked how he would like to be remembered, Justice Kennedy once replied, “Somebody who’s decent, and honest, and fair, and who’s absolutely committed to the proposition that freedom is America’s gift to the rest of the world.” I agree with that assessment.

STEVEN R. SMITH, MS, JD

Reference

- South Dakota v Wayfair, Inc, 585 US (2018)

Next term, the Court is scheduled to hear cases regarding pharmaceutical liability, double jeopardy, sex-offender registration, expert witnesses, Social Security disability benefits, and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act. There will be at least 3 arbitration cases. Health care and reproductive rights will continue to be an important part of the Court’s docket.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The 2017−2018 term of the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) was momentous. Justice Anthony Kennedy, who had been the deciding vote in most of the 5 to 4 cases for a generation, announced his retirement as of July 31, 2018. In addition, the Court decided a number of cases of interest to ObGyns. In this article we review some of those cases, as well as consider the future of the Court without Justice Kennedy. In selecting cases, we have given special attention to those in which national medical organizations filed amicus briefs. These “amicus curiae” or “friend of the court” briefs are filed by an entity who is not party to a case but wants to provide information or views to the court.

1. Abortion rulings

The Court decided 2 abortion cases and rejected a request to hear a third.

National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v Becerra

In this case,1 the Court struck down a California law that required pregnancy crisis centers not offering abortions (generally operated by pro-life groups) to provide special notices to clients.2

At stake. These notices would inform clients that California provides free or low-cost services, including abortions, and provide a phone number to call for those services.

There were many amicus briefs filed in this case, including those by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and other specialty boards,3 as well as the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists and other pro-life organizations.4 ACOG’s brief argued that the California-required notice facilitates the goal of allowing women to receive medical services without harmful delay.

Final ruling. The Court held that the law required clinics to engage in speech with which the clinics disagreed (known as “compelled speech”). It also noted that California disclosure requirements were “wildly underinclusive” because they apply only to some clinics. The majority felt that there was no strong state interest in compelling this speech because there were other alternatives for the state to provide information about the availability of abortion and other services. The Court found that the clinics were likely to succeed on the merits of their claims of a First Amendment (free speech) violation.

Right to abortion for illegal immigrants in custody

A very unusual abortion case involved “Jane Doe,” a minor who was at 8 weeks’ gestation when she illegally crossed the border into the United States.5 She was placed in a federally-funded shelter where she requested an abortion. The facility denied that request.

At stake. Legal argument ensued about releasing her to another facility for an abortion, as the argument was made that pregnant minors who are apprehended crossing into the United States illegally and placed into the custody of federal officials should have abortion access. A lower Court of Appeals ruled against the Trump Administration’s policy of denying abortions to undocumented minors in federal custody. During the process of the federal government taking the case to the Supreme Court, the attorneys for Doe moved appointments around and, without notice, the abortion was performed. Government attorneys said that Doe’s attorneys made “what appear to be material misrepresentations and omissions” designed to “thwart [the Supreme Court’s] review” of the case.5 The government requested that the Court vacate the order of the Court of Appeals so that it could not be used as precedent.

Final ruling. The Court granted the governments request to vacate the lower court’s order because the minor was no longer pregnant and the order was therefore moot. The basic issue in this case (the right of in-custody minors to access abortions) remains unresolved. It is likely to appear before the Court in the future.

Continue to: Access to medical abortions

Access to medical abortions

An Arkansas law requires that a physician administering medical abortions contract with a physician who has admitting privileges at a hospital (a “contracted physician”).

At stake. Planned Parenthood filed suit challenging the requirement as unnecessary and harmful because it would result in the closure of 2 of the 3 abortion providers in Arkansas. ACOG filed an amicus brief urging the Supreme Court to consider the case.6 (Technically this was a petition for a Writ of Certiorari, the procedure by which the Court accepts cases. It accepts only about 1% of applications.) ACOG argued that there was no medical reason for the contracted physician requirement, and noted the harm it would do to women who would not have access to abortions.

Final ruling. On May 29, 2018, the Court declined to hear the case. This case is still active in the lower courts and may eventually return to the Supreme Court.

2. The patent system

The medical profession depends on the patent system to encourage the discovery of new patents efficiently and effectively. In 2012, Congress passed the America Invents Act7 that authorizes a petition by anyone other than the patent holder to the Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) for an “inter partes review” to assess a challenge to the patent’s legitimacy. If the PTO determines that there may be merit to the claim, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board undertakes a trial-like review process that may validate, invalidate, or amend the patent. The Board’s decision is subject to appellate court review.

At stake. This term, the inter partes review was challenged as unconstitutional on technical bases.8

Final ruling. The Court rejected this claim and approved the current administrative inter partes review process. The Court determined that once the Patent Office takes a petition challenging a patent, it must decide all of the claims against the patent, not pick and choose which elements of the challenge to evaluate.9 The Court’s decision upheld patent-review reform, but will require the Patent Office to tweak its procedures.

3. The travel ban

ACOG, the American Medical Association (AMA), the Association of American Medical Colleges, and more than 30 other health care and specialty associations filed an amicus brief regarding one of the most anticipated cases of the term—the “travel ban.”10

At stake. The essential argument of these organizations was that the US health care system depends on professionals from other countries. An efficient and fair immigration program is, therefore, important to advance the nation’s “health security.” During the 2016−2017 term, the Court considered but then removed the issue from its calendar when the Trump Administration issued a revised travel ban.11

In September 2017, President Trump’s proclamation imposed a range of entry restrictions on the citizens of 8 countries, most (but not all) of which are predominantly Muslim. The government indicated that, in a study by Homeland Security and the State Department, these countries were identified as having especially deficient information-sharing practices and presented national security concerns. Trump v Hawaii12 challenged this proclamation.

Final ruling. The majority of the Court upheld the travel ban. For the 5-Justice majority led by Chief Justice Roberts, the case came down to 3 things:

- The Constitution and the laws passed by Congress of necessity give the President great authority to engage in foreign policy, including policies regarding entry into the country.

- The courts are very reluctant to get into the substance of foreign affairs—they are not equipped to know in detail what the facts are, and things change very fast.

- If courts start tinkering with foreign policy and things turn bad, it will appear that the courts are to blame and were interfering in an area about which they are not competent.

Continue to: 4. Did a credit card case add risk to health insurance markets?

It was just a credit card case, but one in which the AMA saw a real risk to regulation of the health insurance markets.

At stake. Technically, Ohio v American Express concerned a claim that American Express (AmEx) violated antitrust laws when it prohibited merchants taking its credit card from “steering” customers to cards with lower fees.13 AmEx maintained that, because credit cards were a special kind of “2-sided” market (connecting merchants on one side and customers on the other), antitrust laws should not be strictly enforced.

The AMA noticed that special rules regarding 2-sided markets might apply to health insurance, and it submitted an amicus brief14 that noted: “dominant health insurance networks … have imposed and could further impose rules or effectively erect barriers that prohibit physicians from referring patients to certain specialists, particularly out-of-network specialists, for innovative and even necessary medical tests.”14 It concluded that the antitrust rule AmEx was suggesting would make it nearly impossible to challenge these unfair provisions in health insurance arrangements.

Final ruling. The Court, however, accepted the AmEx position, making it very difficult to develop an antitrust case against 2-sided markets. It remains to be seen the degree to which the AMA concern about health insurance markets will be realized.

5. Gay wedding and a bakeshop

At stake. In Masterpiece Cakeshop v Colorado, a cakemaker declined to design a cake for a gay wedding and had been disciplined under Colorado law for discriminating against the couple based on sexual orientation.15

Final ruling. The Court, however, found that the Colorado regulators had, ironically, shown such religious animus in the way they treated the baker that the regulators themselves had discriminated on the basis of religion. As a result, the Court reversed the sanctions against the baker.

This decision was fairly narrow. It does not, for example, stand for the proposition that there may be a general religious exception to antidiscrimination laws. The question of broader religious or free-speech objections to antidiscrimination laws remains for another time.

Amicus brief. It was interesting that the American College of Pediatricians, American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and others, filed an amicus brief to report with concern the “demands that individual medical professionals must perform, assist with, or facilitate abortions, without regard to the teachings of their own faiths, consciences, and convictions.”16 The brief also noted that “issues in the present case implicate the fundamental rights of health care professionals, and to respectfully urge that the Court should by no means permit any weakening or qualification of well-established protections against compelled speech, and of free exercise” of religion.16

Arbitration. The Court upheld, as it has in most recent terms, another arbitration agreement.1 This case concerned an employment agreement in which employees consented to submit to arbitration rather than file lawsuits and not use class action claims.

Search of cell-phone location. Cell phones, whenever turned on, connect with cell towers that record the phone’s location several times a minute. Cell companies store this information, creating a virtual map of where the owner is at all times. The Federal Bureau of Investigation asked a cell company for location information for several people during a 127-day period in which robberies were committed.2 The Court held that the search was illegal in the absence of a warrant.

Public employee unions. The Court held that agency (fair share) fees, in which public employees who are not union members can be required to pay dues for the bargaining and grievance activities (from which they generally benefit), violate the First Amendment. The majority held that forcing public employees to pay fees to unions requires the employees, through those fees, to engage in political activities with which they disagree.3 This is a form of compelled speech, which the Court found violates the First Amendment. Health care professionals who are public employees in positions that have union representation will probably have the opportunity to opt out of agency agreements.

Internet sales tax. The Court permitted states to charge sales tax on out-of-state Internet purchases.4 In doing so, a state may require out-of-state companies to collect taxes on sales to its residents.

References

- Epic Systems Corp. v Lewis, 584 US 16 285 (2018).

- Carpenter v United States, 585 US 16 402 (2018).

- Janus v State, County, and Municipal Employees, 585 US 16 1466 (2018).

- South Dakota v Wayfair, Inc, 585 US 17 494 (2018).

Clues to the future

During the term that ran from October 2, 2017, through June 27, 2018, the Court issued 72 decisions. An unusually high proportion of cases (26%; 19 cases) were decided on a 5 to 4 vote. Last term, the rate of 5 to 4 decisions was 10%; the 6-year average was 18%. The unanimous decision rate was 39% this term, compared with 59% last term, and 50% on average.

The rate of 5 to 4 cases provides a clue about the Court’s general direction. The number of times each Justice was in the majority in those nineteen 5 to 4 decisions included: Chief Justice Roberts, 17; and Justices Kennedy, 16; Gorsuch, 16; Thomas, 15; and Alito, 15; compared with Justices Ginsburg, 5; Breyer, 4; Sotomayor, 4; and Kagan, 3.

The Court convened on October 1, 2018. At this writing, whether the new term starts with 8 or 9 justices remains a question. President Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh, JD, to take Justice Kennedy’s place on the Court. His professional qualifications and experience appear to make him qualified for a position on the Court, but as we have seen, there are many other elements that go into confirming a Justice’s nomination.

Justice Anthony Kennedy was the deciding vote in the overwhelming majority of the 5 to 4 decisions in 20 of his 30 years on the Court. The areas in which he had an especially important impact include1:

- Gay rights. Justice Kennedy wrote the opinions (usually 5 to 4 decisions) in a number of groundbreaking gay-rights cases, including decriminalizing homosexual conduct, striking down the Defense of Marriage Act, and finding that the Constitution requires states to recognize gay marriage.

- The death penalty. Justice Kennedy wrote decisions that prohibited states from imposing the death penalty for any crime other than murder, for defendants who were under 18 when they committed the crime, and for defendants with serious developmental disabilities. He expressed reservations about long-term solitary confinement, but did not have a case that allowed him to decide its constitutionality.

- The First Amendment. Early in his service on the Court, he held that the First Amendment protected flag burning as a form of speech. He decided many important freespeech and freedom-of-religion cases that have set a standard for protecting those fundamental freedoms.

- Use of health and social science data. Justice Kennedy was more open to mental health information and cited it more often than most other Justices.

- Abortion rights? Many commentators would add protecting the right to choose to have an abortion to the above list. Justice Kennedy was a central figure in one case that declined to back away from Roe v Wade, and joined a more recent decision that struck down a Texas law that created an undue burden on women seeking abortion. Plus, he also voted to uphold abortion restrictions, such as “partial-birth-abortion laws.” So there is a good argument for including abortion rights on the list, although he did not break new ground.

Justice Kennedy as a person