User login

Does the preterm birth racial disparity persist among black and white IVF users?

Investigators from the National Institutes of Health and Shady Grove Fertility found that among women having a singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) that black women are at higher risk for lower gestational age and preterm delivery than white women.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Kate Devine, MD, coinvestigator of the retrospective cohort study said in an interview with OBG Management that “It’s been well documented that African Americans have a higher preterm birth rate in the United States compared to Caucasians and the overall population. While the exact mechanism of preterm birth is unknown and likely varied, and while the mechanism for the preterm birth rate being higher in African Americans is not well understood, it has been hypothesized that socioeconomic factors are responsible at least in part.”2 She added that the investigators used a population of women receiving IVF for the study because “access to reproductive care and IVF is in some way a leveling factor in terms of socioeconomics.”

Details of the study. The investigators reviewed all singleton IVF pregnancies ending in live birth among women self-identifying as white, black, Asian, or Hispanic from 2004 to 2016 at a private IVF practice (N=10,371). The primary outcome was gestational age at birth, calculated as the number of days from oocyte retrieval to birth, plus 14, among white, black, Asian, and Hispanic women receiving IVF.

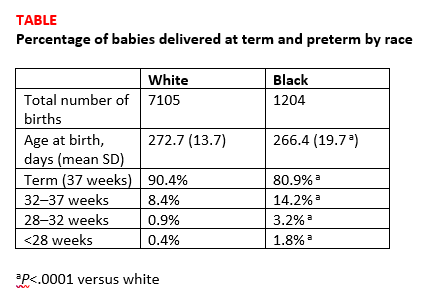

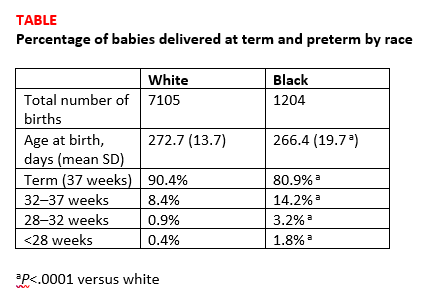

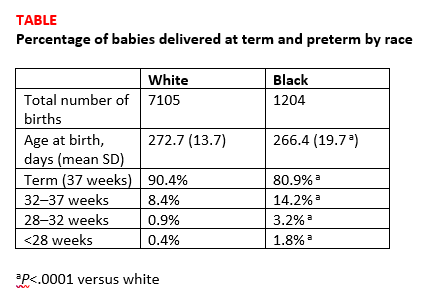

Births among black women occurred more than 6 days earlier than births among white women. The researchers noted that some of the shorter gestations among the black women could be explained by the higher average body mass index of the group (P<.0001). Dr. Devine explained that another contributing factor was the higher incidence of fibroid uterus among the black women (P<.0001). But after adjusting for these and other demographic variables, the black women still delivered 5.5 days earlier than the white women, and they were more than 3 times as likely to have either very preterm or extremely preterm deliveries (TABLE).1

Research implications. Dr. Devine said that black pregnant patients “perhaps should be monitored more closely” for signs or symptoms suggestive of preterm labor and would like to see more research into understanding the mechanisms of preterm birth that are resulting in greater rates of preterm birth among black women. She mentioned that research into how fibroids impact obstetric outcomes is also important.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letters to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Bishop LA, Devine K, Sasson I, et al. Lower gestational age and increased risk of preterm birth associated with singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) among African American versus comparable Caucasian women. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e7.

Investigators from the National Institutes of Health and Shady Grove Fertility found that among women having a singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) that black women are at higher risk for lower gestational age and preterm delivery than white women.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Kate Devine, MD, coinvestigator of the retrospective cohort study said in an interview with OBG Management that “It’s been well documented that African Americans have a higher preterm birth rate in the United States compared to Caucasians and the overall population. While the exact mechanism of preterm birth is unknown and likely varied, and while the mechanism for the preterm birth rate being higher in African Americans is not well understood, it has been hypothesized that socioeconomic factors are responsible at least in part.”2 She added that the investigators used a population of women receiving IVF for the study because “access to reproductive care and IVF is in some way a leveling factor in terms of socioeconomics.”

Details of the study. The investigators reviewed all singleton IVF pregnancies ending in live birth among women self-identifying as white, black, Asian, or Hispanic from 2004 to 2016 at a private IVF practice (N=10,371). The primary outcome was gestational age at birth, calculated as the number of days from oocyte retrieval to birth, plus 14, among white, black, Asian, and Hispanic women receiving IVF.

Births among black women occurred more than 6 days earlier than births among white women. The researchers noted that some of the shorter gestations among the black women could be explained by the higher average body mass index of the group (P<.0001). Dr. Devine explained that another contributing factor was the higher incidence of fibroid uterus among the black women (P<.0001). But after adjusting for these and other demographic variables, the black women still delivered 5.5 days earlier than the white women, and they were more than 3 times as likely to have either very preterm or extremely preterm deliveries (TABLE).1

Research implications. Dr. Devine said that black pregnant patients “perhaps should be monitored more closely” for signs or symptoms suggestive of preterm labor and would like to see more research into understanding the mechanisms of preterm birth that are resulting in greater rates of preterm birth among black women. She mentioned that research into how fibroids impact obstetric outcomes is also important.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letters to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Investigators from the National Institutes of Health and Shady Grove Fertility found that among women having a singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) that black women are at higher risk for lower gestational age and preterm delivery than white women.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Kate Devine, MD, coinvestigator of the retrospective cohort study said in an interview with OBG Management that “It’s been well documented that African Americans have a higher preterm birth rate in the United States compared to Caucasians and the overall population. While the exact mechanism of preterm birth is unknown and likely varied, and while the mechanism for the preterm birth rate being higher in African Americans is not well understood, it has been hypothesized that socioeconomic factors are responsible at least in part.”2 She added that the investigators used a population of women receiving IVF for the study because “access to reproductive care and IVF is in some way a leveling factor in terms of socioeconomics.”

Details of the study. The investigators reviewed all singleton IVF pregnancies ending in live birth among women self-identifying as white, black, Asian, or Hispanic from 2004 to 2016 at a private IVF practice (N=10,371). The primary outcome was gestational age at birth, calculated as the number of days from oocyte retrieval to birth, plus 14, among white, black, Asian, and Hispanic women receiving IVF.

Births among black women occurred more than 6 days earlier than births among white women. The researchers noted that some of the shorter gestations among the black women could be explained by the higher average body mass index of the group (P<.0001). Dr. Devine explained that another contributing factor was the higher incidence of fibroid uterus among the black women (P<.0001). But after adjusting for these and other demographic variables, the black women still delivered 5.5 days earlier than the white women, and they were more than 3 times as likely to have either very preterm or extremely preterm deliveries (TABLE).1

Research implications. Dr. Devine said that black pregnant patients “perhaps should be monitored more closely” for signs or symptoms suggestive of preterm labor and would like to see more research into understanding the mechanisms of preterm birth that are resulting in greater rates of preterm birth among black women. She mentioned that research into how fibroids impact obstetric outcomes is also important.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letters to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Bishop LA, Devine K, Sasson I, et al. Lower gestational age and increased risk of preterm birth associated with singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) among African American versus comparable Caucasian women. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e7.

- Bishop LA, Devine K, Sasson I, et al. Lower gestational age and increased risk of preterm birth associated with singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) among African American versus comparable Caucasian women. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e7.

Prior fertility treatment is associated with higher maternal morbidity during delivery

Investigators from the Stanford Hospital and Clinics in California found that while absolute risk is low, women who have received an infertility diagnosis or who have received fertility treatment are at higher risk of several markers of severe maternal morbidity than women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Gaya Murugappan, MD, lead investigator on the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “We know that in the last decade or so the rate of maternal morbidity has been rising gradually in the US, and we know that the utilization of fertility technology and the incidence of infertility are also rising.” The retrospective analysis set out to determine if a connection exists.

Methods. The investigators used a large insurance claims database to look at data from 2003 to 2016. They identified a group of infertile women who later conceived without fertility treatment (n=1822 deliveries) and a group of women who received fertility treatment (n=782 deliveries) and compared them with a control group of women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment (n=37,944 deliveries). Women who currently or previously had cancer were excluded from the study.

The primary outcome was the number of indicators of severe maternal morbidity that occurred during the 6 months prior to or following delivery.

Findings. Compared with the control group, the women diagnosed with infertility were almost 4 times as likely to experience severe anesthesia complications (0.38% vs 0.11%; odds ratio [OR], 3.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.69–8.70), about twice as likely to experience intraoperative heart failure (0.71% vs 0.31%; OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.05–3.34), and more than 3 times as likely to receive a hysterectomy (1.04% vs 0.28%; OR, 3.30; 95% CI, 2.02–5.40).

Similarly, compared with controls, women who had received fertility treatment had an OR of 2.66 for disseminated intravascular coagulation (2.81% vs 0.91%; 95% CI, 1.66–4.24), an OR of 5.17 for shock (0.90% vs 0.15%; 95% CI, 2.21–12.06), an OR of 1.61 for blood transfusions (3.71% vs 1.64%; 95% CI, 1.07–2.42), and an OR of 1.43 for cardiac monitoring (13.17% vs 8.14%; 95% CI, 1.14–1.79).

More research is needed. Dr. Murugappan noted, “I hope that these data help us identify high-risk populations of women so that we can minimize the occurrence of these potentially devastating health outcomes. Women need to be telling their ObGyns that they have a history of infertility and/or fertility treatment. Some women may not want to say that they conceived with donor egg, for example, but that could be a critical element of a patient’s history that an ObGyn should be aware of.”

More study is necessary, she added. For instance, “a study in the future looking at risk of maternal morbidity in patients who are infertile but then who go on to conceive spontaneously. Then we can tease out what is the effect of infertility versus the effect of fertility treatment.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Murugappan G, Li S, Lathi RB, Baker VL, Eisenberg ML. Increased risk of maternal morbidity in infertile women: analysis of US claims data. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e9.

Investigators from the Stanford Hospital and Clinics in California found that while absolute risk is low, women who have received an infertility diagnosis or who have received fertility treatment are at higher risk of several markers of severe maternal morbidity than women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Gaya Murugappan, MD, lead investigator on the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “We know that in the last decade or so the rate of maternal morbidity has been rising gradually in the US, and we know that the utilization of fertility technology and the incidence of infertility are also rising.” The retrospective analysis set out to determine if a connection exists.

Methods. The investigators used a large insurance claims database to look at data from 2003 to 2016. They identified a group of infertile women who later conceived without fertility treatment (n=1822 deliveries) and a group of women who received fertility treatment (n=782 deliveries) and compared them with a control group of women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment (n=37,944 deliveries). Women who currently or previously had cancer were excluded from the study.

The primary outcome was the number of indicators of severe maternal morbidity that occurred during the 6 months prior to or following delivery.

Findings. Compared with the control group, the women diagnosed with infertility were almost 4 times as likely to experience severe anesthesia complications (0.38% vs 0.11%; odds ratio [OR], 3.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.69–8.70), about twice as likely to experience intraoperative heart failure (0.71% vs 0.31%; OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.05–3.34), and more than 3 times as likely to receive a hysterectomy (1.04% vs 0.28%; OR, 3.30; 95% CI, 2.02–5.40).

Similarly, compared with controls, women who had received fertility treatment had an OR of 2.66 for disseminated intravascular coagulation (2.81% vs 0.91%; 95% CI, 1.66–4.24), an OR of 5.17 for shock (0.90% vs 0.15%; 95% CI, 2.21–12.06), an OR of 1.61 for blood transfusions (3.71% vs 1.64%; 95% CI, 1.07–2.42), and an OR of 1.43 for cardiac monitoring (13.17% vs 8.14%; 95% CI, 1.14–1.79).

More research is needed. Dr. Murugappan noted, “I hope that these data help us identify high-risk populations of women so that we can minimize the occurrence of these potentially devastating health outcomes. Women need to be telling their ObGyns that they have a history of infertility and/or fertility treatment. Some women may not want to say that they conceived with donor egg, for example, but that could be a critical element of a patient’s history that an ObGyn should be aware of.”

More study is necessary, she added. For instance, “a study in the future looking at risk of maternal morbidity in patients who are infertile but then who go on to conceive spontaneously. Then we can tease out what is the effect of infertility versus the effect of fertility treatment.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Investigators from the Stanford Hospital and Clinics in California found that while absolute risk is low, women who have received an infertility diagnosis or who have received fertility treatment are at higher risk of several markers of severe maternal morbidity than women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Gaya Murugappan, MD, lead investigator on the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “We know that in the last decade or so the rate of maternal morbidity has been rising gradually in the US, and we know that the utilization of fertility technology and the incidence of infertility are also rising.” The retrospective analysis set out to determine if a connection exists.

Methods. The investigators used a large insurance claims database to look at data from 2003 to 2016. They identified a group of infertile women who later conceived without fertility treatment (n=1822 deliveries) and a group of women who received fertility treatment (n=782 deliveries) and compared them with a control group of women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment (n=37,944 deliveries). Women who currently or previously had cancer were excluded from the study.

The primary outcome was the number of indicators of severe maternal morbidity that occurred during the 6 months prior to or following delivery.

Findings. Compared with the control group, the women diagnosed with infertility were almost 4 times as likely to experience severe anesthesia complications (0.38% vs 0.11%; odds ratio [OR], 3.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.69–8.70), about twice as likely to experience intraoperative heart failure (0.71% vs 0.31%; OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.05–3.34), and more than 3 times as likely to receive a hysterectomy (1.04% vs 0.28%; OR, 3.30; 95% CI, 2.02–5.40).

Similarly, compared with controls, women who had received fertility treatment had an OR of 2.66 for disseminated intravascular coagulation (2.81% vs 0.91%; 95% CI, 1.66–4.24), an OR of 5.17 for shock (0.90% vs 0.15%; 95% CI, 2.21–12.06), an OR of 1.61 for blood transfusions (3.71% vs 1.64%; 95% CI, 1.07–2.42), and an OR of 1.43 for cardiac monitoring (13.17% vs 8.14%; 95% CI, 1.14–1.79).

More research is needed. Dr. Murugappan noted, “I hope that these data help us identify high-risk populations of women so that we can minimize the occurrence of these potentially devastating health outcomes. Women need to be telling their ObGyns that they have a history of infertility and/or fertility treatment. Some women may not want to say that they conceived with donor egg, for example, but that could be a critical element of a patient’s history that an ObGyn should be aware of.”

More study is necessary, she added. For instance, “a study in the future looking at risk of maternal morbidity in patients who are infertile but then who go on to conceive spontaneously. Then we can tease out what is the effect of infertility versus the effect of fertility treatment.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Murugappan G, Li S, Lathi RB, Baker VL, Eisenberg ML. Increased risk of maternal morbidity in infertile women: analysis of US claims data. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e9.

- Murugappan G, Li S, Lathi RB, Baker VL, Eisenberg ML. Increased risk of maternal morbidity in infertile women: analysis of US claims data. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e9.

Should return to fertility be a concern for nulliparous patients using an IUD?

Investigators from the University of Texas Southwestern are dispelling the myth that you shouldn’t recommend intrauterine devices (IUDs) for nulliparous women because the devices might make it more difficult for them to become pregnant after discontinuation. They found that nulliparous women can just as easily get pregnant after using a progestin intrauterine system (IUS) as parous women,1 according to results of a study presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6–10, Denver, Colorado).

Bruce R. Carr, MD, lead investigator of the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “There have been a number of studies—maybe 10 to 15 years ago—that looked at pregnancy rates when patients stopped using IUDs, but most of these studies were done in women who were multiparous. There is almost no data on patients who are nulliparous stopping an IUD and trying to get pregnant.”

Participants and methods. This prospective, multicenter, clinical trial, which is still ongoing, is evaluating the efficacy and safety for up to 10 years of the Liletta levonorgestrel 52-mg IUS in nulliparous and parous women ages 16 to 45 years. Every 3 months for up to 1 year, the investigators contacted the women who discontinued the IUS during the first 5 years of use and who were trying to become pregnant to determine pregnancy status.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was time to pregnancy among nulliparous vs parous women after discontinuation of a progestin IUS.

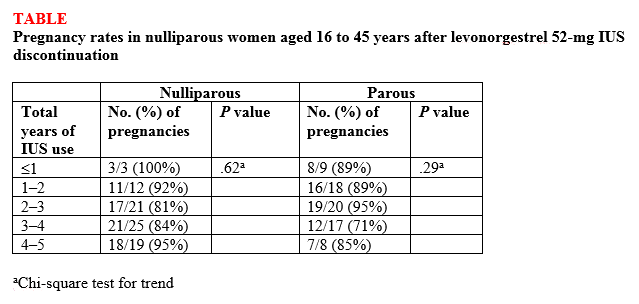

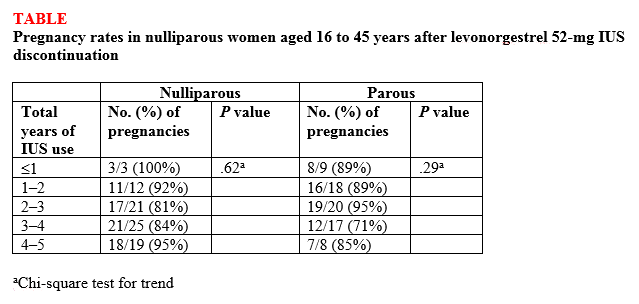

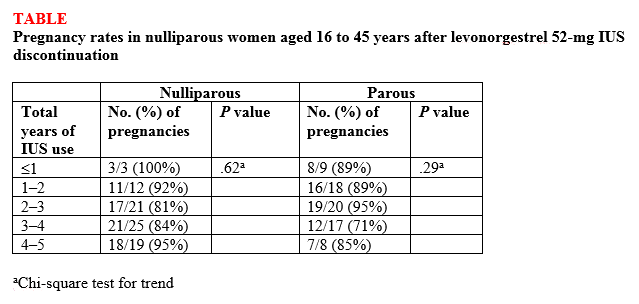

Findings. Overall, 132 (87%) of 152 women ages 16 to 35 years at the beginning of the study who attempted to become pregnant did so within 1 year of discontinuing the IUS, and there was no difference in pregnancy rates between nulliparous and parous women (87.5% vs 86.1%, respectively; P<.82) or between nulligravid and gravid women (88.2% vs 85.7%, respectively; P<.81). High percentages of women became pregnant by the end of 3 months (43.4%) and 6 months (69.7%), with a median time to conception of 91.5 days. The women used the IUS for a median of 34 months before discontinuation. Length of IUS use and age of the women at IUS discontinuation did not affect pregnancy rates at 12 months postdiscontinuation in either nulliparous or parous women (TABLE).1

“The bottom line,” according to Dr. Carr, is that the “pregnancy rates were the same in women who had never been pregnant compared with women who had previously been pregnant.” He continued, “People worried that if a patient who had never been pregnant used an IUD that maybe she was going to have a harder time getting pregnant after discontinuing, and now we know that is not true. It [the study] reinforces the option of using progestin IUDs and not having to worry about future pregnancy.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This article was updated October 15, 2018.

- Carr BR, Thomas MA, Gangestad A, Eisenberg DL, Olariu AI, Creinin MD. Return of fertility in nulliparous and parous women after levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system discontinuation [ASRM abstract O-104]. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e46.

Investigators from the University of Texas Southwestern are dispelling the myth that you shouldn’t recommend intrauterine devices (IUDs) for nulliparous women because the devices might make it more difficult for them to become pregnant after discontinuation. They found that nulliparous women can just as easily get pregnant after using a progestin intrauterine system (IUS) as parous women,1 according to results of a study presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6–10, Denver, Colorado).

Bruce R. Carr, MD, lead investigator of the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “There have been a number of studies—maybe 10 to 15 years ago—that looked at pregnancy rates when patients stopped using IUDs, but most of these studies were done in women who were multiparous. There is almost no data on patients who are nulliparous stopping an IUD and trying to get pregnant.”

Participants and methods. This prospective, multicenter, clinical trial, which is still ongoing, is evaluating the efficacy and safety for up to 10 years of the Liletta levonorgestrel 52-mg IUS in nulliparous and parous women ages 16 to 45 years. Every 3 months for up to 1 year, the investigators contacted the women who discontinued the IUS during the first 5 years of use and who were trying to become pregnant to determine pregnancy status.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was time to pregnancy among nulliparous vs parous women after discontinuation of a progestin IUS.

Findings. Overall, 132 (87%) of 152 women ages 16 to 35 years at the beginning of the study who attempted to become pregnant did so within 1 year of discontinuing the IUS, and there was no difference in pregnancy rates between nulliparous and parous women (87.5% vs 86.1%, respectively; P<.82) or between nulligravid and gravid women (88.2% vs 85.7%, respectively; P<.81). High percentages of women became pregnant by the end of 3 months (43.4%) and 6 months (69.7%), with a median time to conception of 91.5 days. The women used the IUS for a median of 34 months before discontinuation. Length of IUS use and age of the women at IUS discontinuation did not affect pregnancy rates at 12 months postdiscontinuation in either nulliparous or parous women (TABLE).1

“The bottom line,” according to Dr. Carr, is that the “pregnancy rates were the same in women who had never been pregnant compared with women who had previously been pregnant.” He continued, “People worried that if a patient who had never been pregnant used an IUD that maybe she was going to have a harder time getting pregnant after discontinuing, and now we know that is not true. It [the study] reinforces the option of using progestin IUDs and not having to worry about future pregnancy.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This article was updated October 15, 2018.

Investigators from the University of Texas Southwestern are dispelling the myth that you shouldn’t recommend intrauterine devices (IUDs) for nulliparous women because the devices might make it more difficult for them to become pregnant after discontinuation. They found that nulliparous women can just as easily get pregnant after using a progestin intrauterine system (IUS) as parous women,1 according to results of a study presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6–10, Denver, Colorado).

Bruce R. Carr, MD, lead investigator of the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “There have been a number of studies—maybe 10 to 15 years ago—that looked at pregnancy rates when patients stopped using IUDs, but most of these studies were done in women who were multiparous. There is almost no data on patients who are nulliparous stopping an IUD and trying to get pregnant.”

Participants and methods. This prospective, multicenter, clinical trial, which is still ongoing, is evaluating the efficacy and safety for up to 10 years of the Liletta levonorgestrel 52-mg IUS in nulliparous and parous women ages 16 to 45 years. Every 3 months for up to 1 year, the investigators contacted the women who discontinued the IUS during the first 5 years of use and who were trying to become pregnant to determine pregnancy status.

Outcomes. The primary outcome was time to pregnancy among nulliparous vs parous women after discontinuation of a progestin IUS.

Findings. Overall, 132 (87%) of 152 women ages 16 to 35 years at the beginning of the study who attempted to become pregnant did so within 1 year of discontinuing the IUS, and there was no difference in pregnancy rates between nulliparous and parous women (87.5% vs 86.1%, respectively; P<.82) or between nulligravid and gravid women (88.2% vs 85.7%, respectively; P<.81). High percentages of women became pregnant by the end of 3 months (43.4%) and 6 months (69.7%), with a median time to conception of 91.5 days. The women used the IUS for a median of 34 months before discontinuation. Length of IUS use and age of the women at IUS discontinuation did not affect pregnancy rates at 12 months postdiscontinuation in either nulliparous or parous women (TABLE).1

“The bottom line,” according to Dr. Carr, is that the “pregnancy rates were the same in women who had never been pregnant compared with women who had previously been pregnant.” He continued, “People worried that if a patient who had never been pregnant used an IUD that maybe she was going to have a harder time getting pregnant after discontinuing, and now we know that is not true. It [the study] reinforces the option of using progestin IUDs and not having to worry about future pregnancy.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This article was updated October 15, 2018.

- Carr BR, Thomas MA, Gangestad A, Eisenberg DL, Olariu AI, Creinin MD. Return of fertility in nulliparous and parous women after levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system discontinuation [ASRM abstract O-104]. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e46.

- Carr BR, Thomas MA, Gangestad A, Eisenberg DL, Olariu AI, Creinin MD. Return of fertility in nulliparous and parous women after levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system discontinuation [ASRM abstract O-104]. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e46.