User login

Clinical factors drive hospitalization after self-harm

Clinicians who assess suicidal patients in the emergency department setting face the challenge of whether to admit the patient to inpatient or outpatient care, and data on predictors of compulsory admission are limited, wrote Laurent Michaud, MD, of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and colleagues.

To better identify predictors of hospitalization after self-harm, the researchers reviewed data from 1,832 patients aged 18 years and older admitted to four emergency departments in Switzerland between December 2016 and November 2019 .

Self-harm (SH) was defined in this study as “all nonfatal intentional acts of self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation,” the researchers noted. The study included 2,142 episodes of self-harm.

The researchers conducted two analyses. They compared episodes followed by any hospitalization and those with outpatient follow-up (1,083 episodes vs. 1,059 episodes) and episodes followed by compulsory hospitalization (357 episodes) with all other episodes followed by either outpatient care or voluntary hospitalization (1,785 episodes).

Overall, women were significantly more likely to be referred to outpatient follow-up compared with men (61.8% vs. 38.1%), and hospitalized patients were significantly older than outpatients (mean age of 41 years vs. 36 years, P < .001 for both).

“Not surprisingly, major psychopathological conditions such as depression, mania, dementia, and schizophrenia were predictive of hospitalization,” the researchers noted.

Other sociodemographic factors associated with hospitalization included living alone, no children, problematic socioeconomic status, and unemployment. Clinical factors associated with hospitalization included physical pain, more lethal suicide attempt method, and clear intent to die.

In a multivariate analysis, independent predictors of any hospitalization included male gender, older age, assessment in the Neuchatel location vs. Lausanne, depression vs. personality disorders, substance use, or anxiety disorder, difficult socioeconomic status, a clear vs. unclear intent to die, and a serious suicide attempt vs. less serious.

Differences in hospitalization based on hospital setting was a striking finding, the researchers wrote in their discussion. These differences may be largely explained by the organization of local mental health services and specific institutional cultures; the workload of staff and availability of beds also may have played a role in decisions to hospitalize, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the lack of data on the realization level of a self-harm episode and significant events such as a breakup, the researchers explained. Other limitations included missing data, multiple analyses that could increase the risk of false positives, the reliance on clinical diagnosis rather than formal instruments, and the cross-sectional study design, they said.

However, the results have clinical implications, as the clinical factors identified could be used to target subgroups of suicidal populations and refine treatment strategies, they concluded.

The study was supported by institutional funding and the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Clinicians who assess suicidal patients in the emergency department setting face the challenge of whether to admit the patient to inpatient or outpatient care, and data on predictors of compulsory admission are limited, wrote Laurent Michaud, MD, of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and colleagues.

To better identify predictors of hospitalization after self-harm, the researchers reviewed data from 1,832 patients aged 18 years and older admitted to four emergency departments in Switzerland between December 2016 and November 2019 .

Self-harm (SH) was defined in this study as “all nonfatal intentional acts of self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation,” the researchers noted. The study included 2,142 episodes of self-harm.

The researchers conducted two analyses. They compared episodes followed by any hospitalization and those with outpatient follow-up (1,083 episodes vs. 1,059 episodes) and episodes followed by compulsory hospitalization (357 episodes) with all other episodes followed by either outpatient care or voluntary hospitalization (1,785 episodes).

Overall, women were significantly more likely to be referred to outpatient follow-up compared with men (61.8% vs. 38.1%), and hospitalized patients were significantly older than outpatients (mean age of 41 years vs. 36 years, P < .001 for both).

“Not surprisingly, major psychopathological conditions such as depression, mania, dementia, and schizophrenia were predictive of hospitalization,” the researchers noted.

Other sociodemographic factors associated with hospitalization included living alone, no children, problematic socioeconomic status, and unemployment. Clinical factors associated with hospitalization included physical pain, more lethal suicide attempt method, and clear intent to die.

In a multivariate analysis, independent predictors of any hospitalization included male gender, older age, assessment in the Neuchatel location vs. Lausanne, depression vs. personality disorders, substance use, or anxiety disorder, difficult socioeconomic status, a clear vs. unclear intent to die, and a serious suicide attempt vs. less serious.

Differences in hospitalization based on hospital setting was a striking finding, the researchers wrote in their discussion. These differences may be largely explained by the organization of local mental health services and specific institutional cultures; the workload of staff and availability of beds also may have played a role in decisions to hospitalize, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the lack of data on the realization level of a self-harm episode and significant events such as a breakup, the researchers explained. Other limitations included missing data, multiple analyses that could increase the risk of false positives, the reliance on clinical diagnosis rather than formal instruments, and the cross-sectional study design, they said.

However, the results have clinical implications, as the clinical factors identified could be used to target subgroups of suicidal populations and refine treatment strategies, they concluded.

The study was supported by institutional funding and the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Clinicians who assess suicidal patients in the emergency department setting face the challenge of whether to admit the patient to inpatient or outpatient care, and data on predictors of compulsory admission are limited, wrote Laurent Michaud, MD, of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and colleagues.

To better identify predictors of hospitalization after self-harm, the researchers reviewed data from 1,832 patients aged 18 years and older admitted to four emergency departments in Switzerland between December 2016 and November 2019 .

Self-harm (SH) was defined in this study as “all nonfatal intentional acts of self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation,” the researchers noted. The study included 2,142 episodes of self-harm.

The researchers conducted two analyses. They compared episodes followed by any hospitalization and those with outpatient follow-up (1,083 episodes vs. 1,059 episodes) and episodes followed by compulsory hospitalization (357 episodes) with all other episodes followed by either outpatient care or voluntary hospitalization (1,785 episodes).

Overall, women were significantly more likely to be referred to outpatient follow-up compared with men (61.8% vs. 38.1%), and hospitalized patients were significantly older than outpatients (mean age of 41 years vs. 36 years, P < .001 for both).

“Not surprisingly, major psychopathological conditions such as depression, mania, dementia, and schizophrenia were predictive of hospitalization,” the researchers noted.

Other sociodemographic factors associated with hospitalization included living alone, no children, problematic socioeconomic status, and unemployment. Clinical factors associated with hospitalization included physical pain, more lethal suicide attempt method, and clear intent to die.

In a multivariate analysis, independent predictors of any hospitalization included male gender, older age, assessment in the Neuchatel location vs. Lausanne, depression vs. personality disorders, substance use, or anxiety disorder, difficult socioeconomic status, a clear vs. unclear intent to die, and a serious suicide attempt vs. less serious.

Differences in hospitalization based on hospital setting was a striking finding, the researchers wrote in their discussion. These differences may be largely explained by the organization of local mental health services and specific institutional cultures; the workload of staff and availability of beds also may have played a role in decisions to hospitalize, they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the lack of data on the realization level of a self-harm episode and significant events such as a breakup, the researchers explained. Other limitations included missing data, multiple analyses that could increase the risk of false positives, the reliance on clinical diagnosis rather than formal instruments, and the cross-sectional study design, they said.

However, the results have clinical implications, as the clinical factors identified could be used to target subgroups of suicidal populations and refine treatment strategies, they concluded.

The study was supported by institutional funding and the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

Lithium-associated hypercalcemia: Monitoring and management

Hypercalcemia is a well-known but underrecognized adverse effect of lithium. Most patients with lithium-associated hypercalcemia (LAH) have either nonspecific symptoms (eg, persistent tiredness, constipation, polyuria, polydipsia) or no symptoms. Clinically, LAH differs from primary hyperparathyroidism, though the management protocol of these 2 conditions is almost the same. In this article, we discuss how lithium can affect calcium and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels and how LAH and lithium-associated hyperparathyroidism (LAHP) differs from primary hyperparathyroidism. We also outline a suggested approach to monitoring and management.

An insidious problem

Due to the varying definitions and methods used to assess hypercalcemia, the reported prevalence of LAH varies from 4.3% to 80%.1 McKnight et al2 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of the relationship between lithium and parathyroid function that included 14 case-control studies, 36 case reports, and 6 cross-sectional studies without a control group. They found that the levels of calcium and PTH were 10% higher in lithium-treated patients than in controls.2

Pathophysiology. Lithium is known to increase both calcium and PTH levels. PTH is responsible for calcium homeostasis. It is secreted in response to low calcium levels, which it increases by its action on bones, intestines, and kidneys. Vitamin D also plays a crucial role in calcium homeostasis. A deficiency of vitamin D triggers a compensatory increase in PTH to maintain calcium levels.3

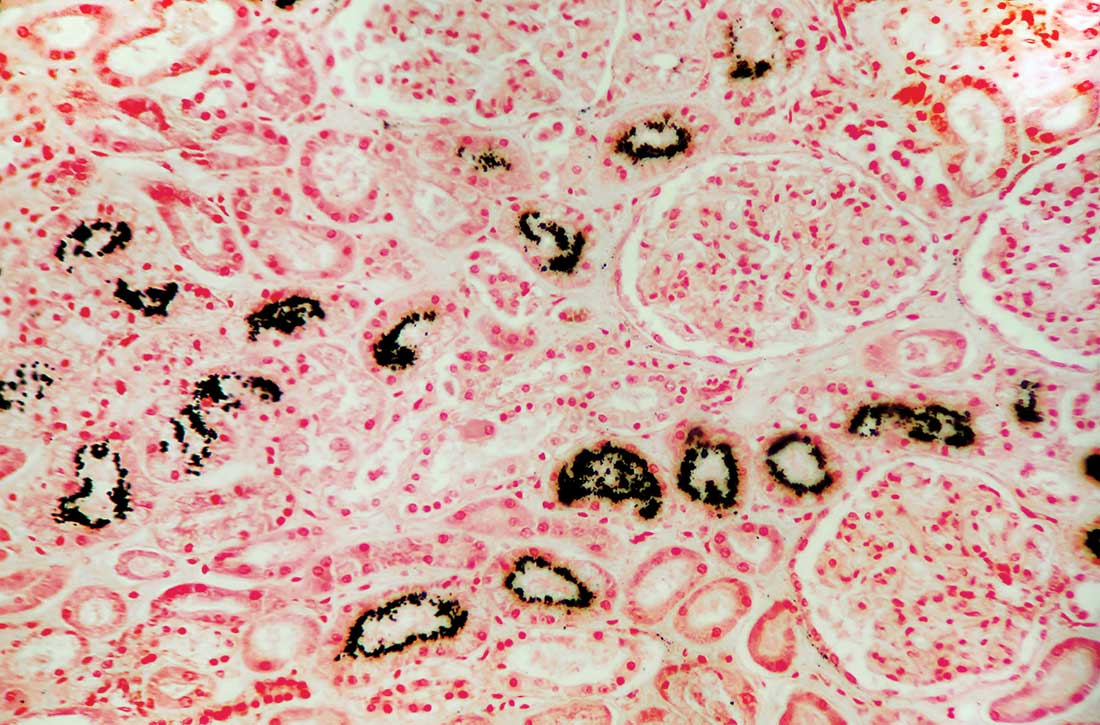

Calcium and PTH levels increase soon after administration of lithium, but the rise is usually mild and insidious. In a small proportion of patients who receive long-term lithium treatment, calcium levels can exceed the normal range. Patients who develop LAH typically have serum calcium levels slightly above the normal range and PTH levels ranging from the higher side of the normal range to several times the upper limit of the normal range. Patients might also experience elevated PTH levels without any increase in calcium levels. Lithium can affect calcium and PTH levels in multiple ways. For instance, it increases the reabsorption of calcium in the kidney as well as the reset point of calcium-sensing receptors. Therefore, only higher levels of calcium can inhibit the release of PTH. Hence, in cases where the PTH level is within the normal range, it is generally higher than would be expected for a given serum calcium level. Lithium can also directly affect the parathyroid glands and can lead to either single-nodule or multimodule hyperplasia.4

Long-term lithium use can cause chronic kidney disease (CKD), which in turn leads to vitamin D deficiency and hyperparathyroidism. However, secondary hyperparathyroidism with CKD is usually seen in the more advanced stages of CKD, and is associated with low-to-normal calcium levels (as opposed to the high levels seen in LAH).3-5

Lithium-associated hyperparathyroidism

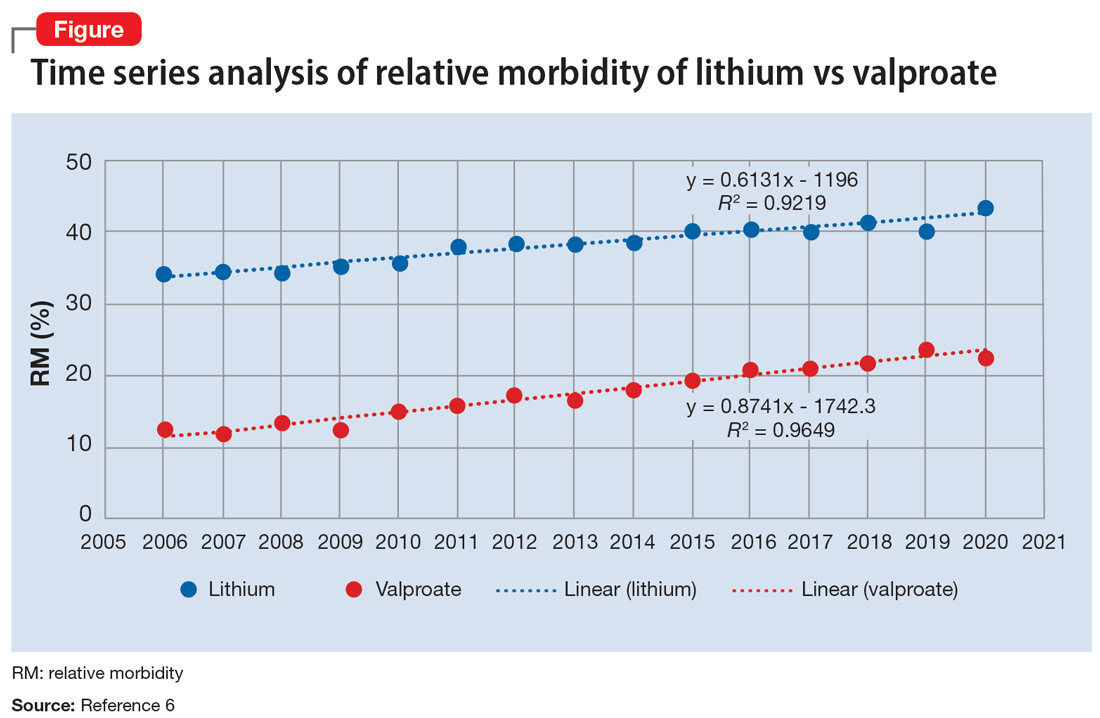

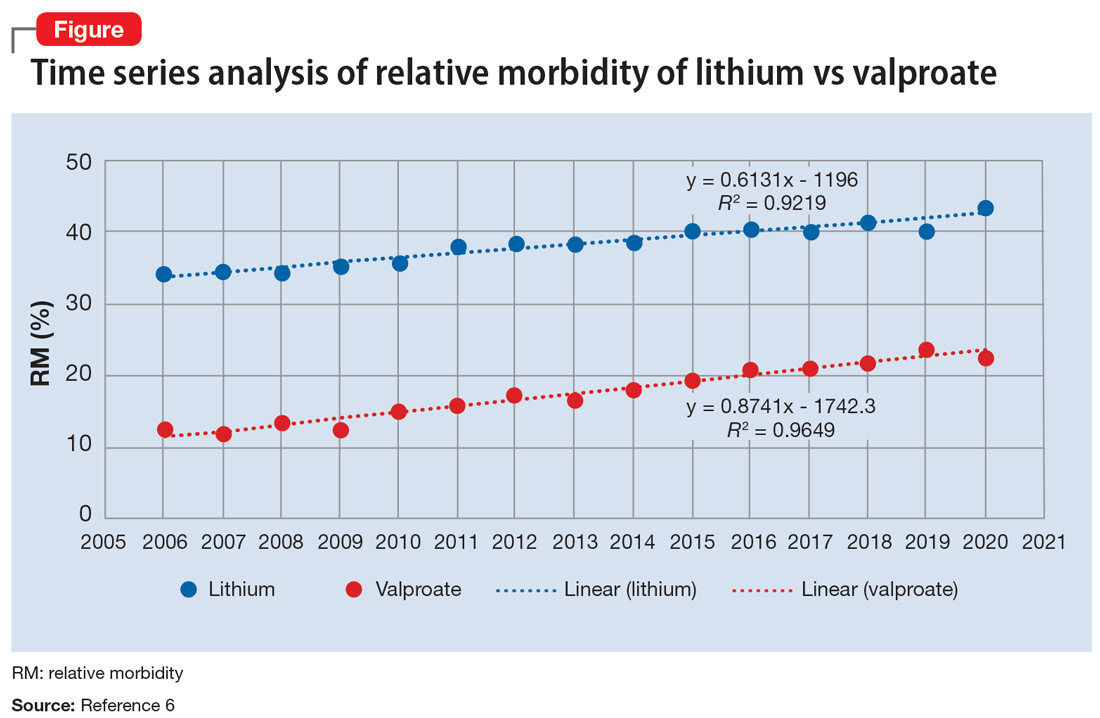

Primary hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of hypercalcemia. Its prevalence ranges from 1 to 7 cases per 1,000 adults. The incidence of LAH/LAHP is 4- to 6-fold higher compared to the general population.6 Similar to LAH/LAHP, primary hyperparathyroidism is more common in older adults (age >60) and females. Hence, some researchers have suggested that lithium probably unmasks hyperparathyroidism in patients who are susceptible to primary hyperparathyroidism.3

Look for these clinical manifestations

Symptoms of primary hyperparathyroidism are related to high calcium and PTH levels. They are commonly described as “painful bones, renal stones, abdominal groans (due to hypercalcemia-induced ileus), and psychic moans (lethargy, poor concentration, depression).” Common adverse outcomes associated with primary hyperparathyroidism are renal stones, high risk of fracture, constipation, peptic ulcer, and pancreatitis.3,7

Continue: In contrast...

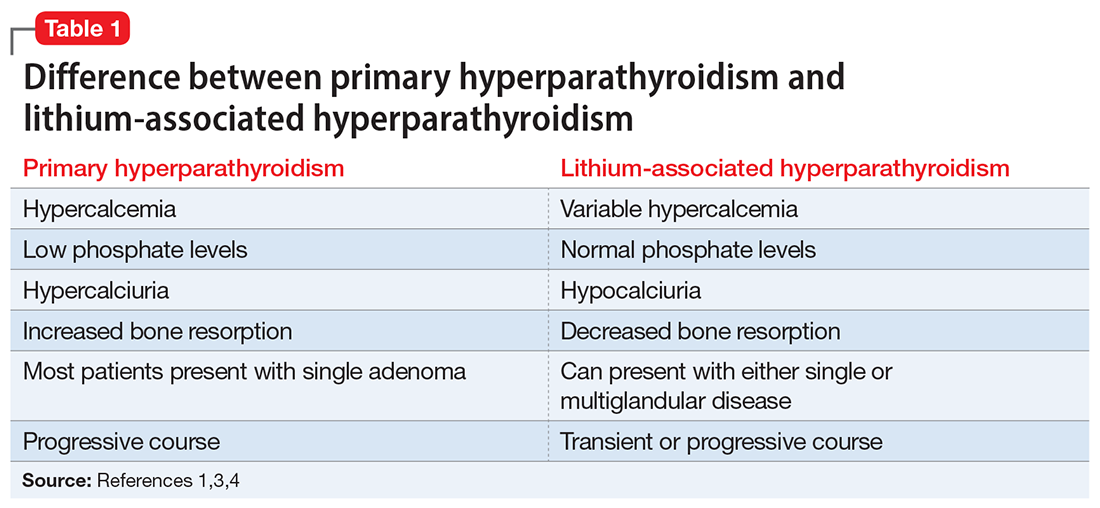

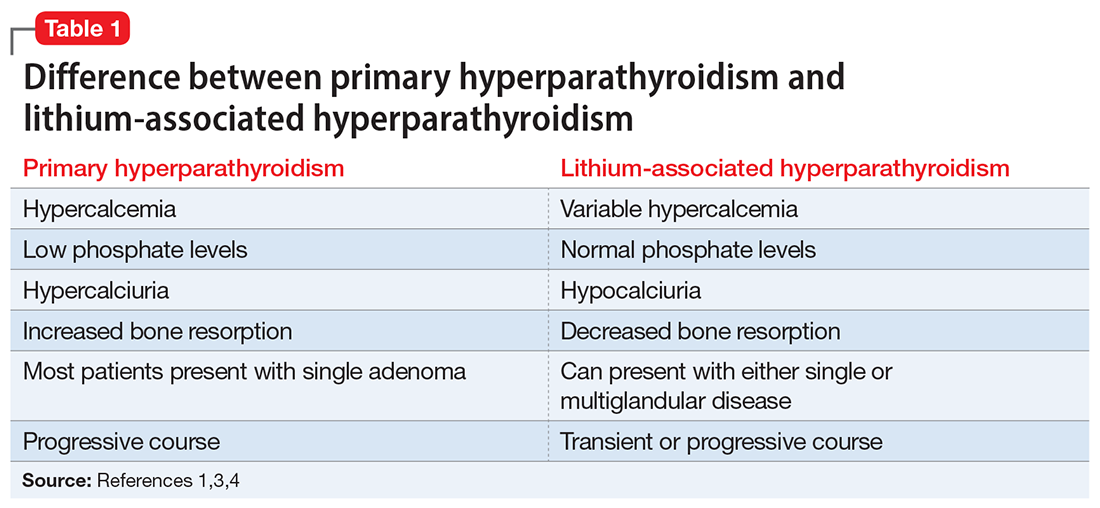

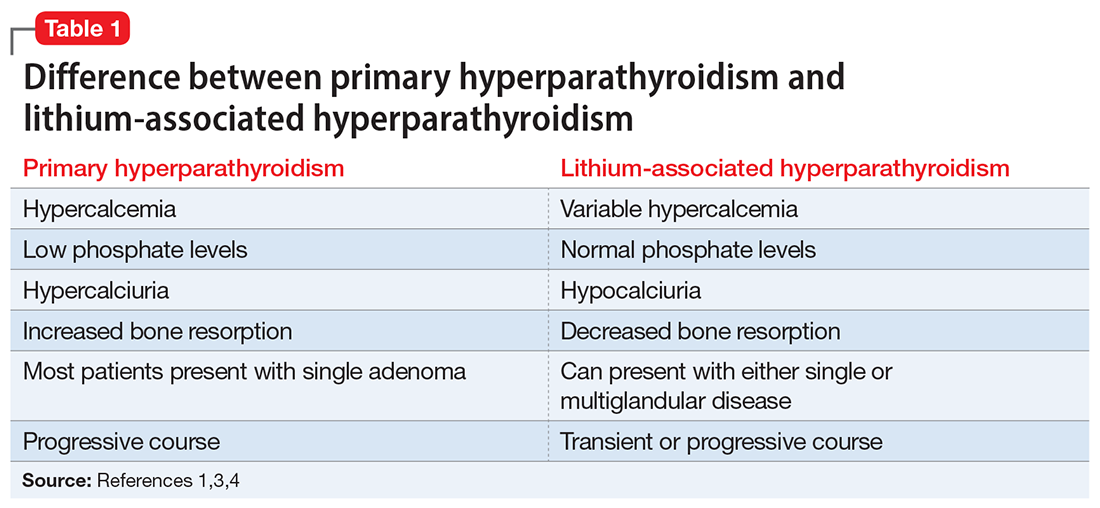

In contrast, LAHP is characterized by mild, intermittent, and/or persistent hypercalcemia and mildly increased PTH (Table 1).1,3,4 In some patients, it could improve without active intervention. Because lithium increases the absorption of urinary calcium, it is associated with hypocalciuria and a lower risk of renal stones. Additionally, lithium has osteoprotective effects and has not been associated with an increased risk of fracture. Some researchers have suggested that the presentation of LAHP is more like familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHC), which is also associated with hypocalciuria. FHC is a benign condition and does not require active intervention.3,4 Similar to those with FHC, many patients with LAHP may live with chronic asymptomatic hypercalcemia without any significant adverse outcome.

A suggested approach to monitoring

In most cases, LAH is an insidious adverse effect that is usually detected on blood tests after many years of lithium therapy.8 For patients starting lithium therapy, International Society of Bipolar Disorder guidelines recommend testing calcium levels at baseline, 6 months, and annually thereafter, or as clinically indicated, to detect and monitor hypercalcemia and hyperparathyroidism. However, these guidelines do not provide any recommendations regarding how to manage abnormal findings.9

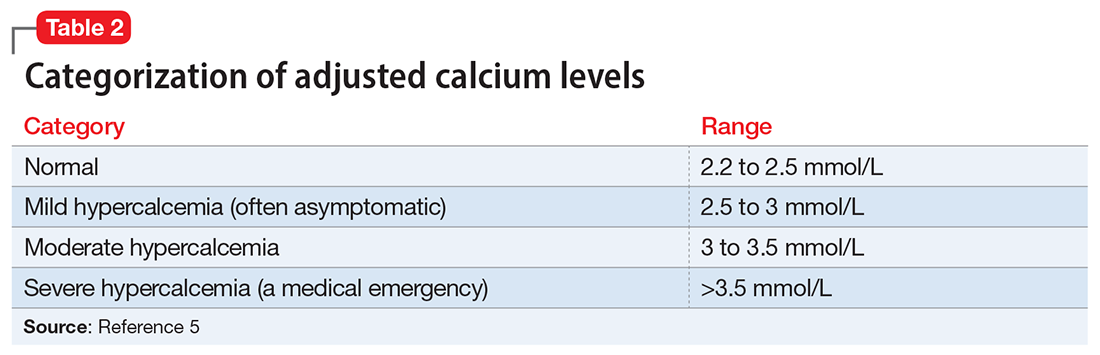

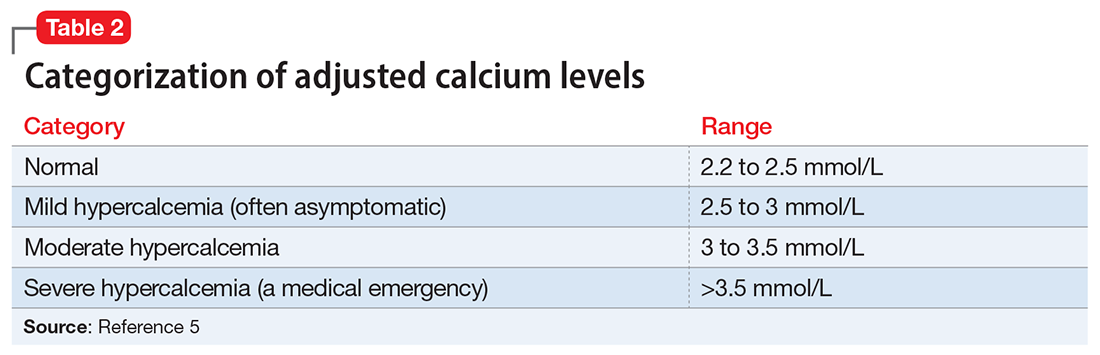

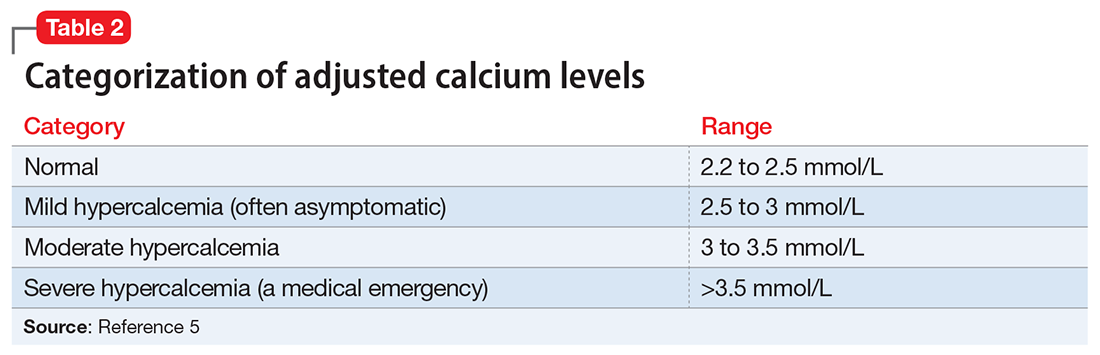

Clinical laboratories report both total and adjusted calcium values. The adjusted calcium value takes into account albumin levels. This is a way to compensate for an abnormal concentration of albumin (establishing what a patient’s total calcium concentration would be if the albumin concentration was normal). Table 25 shows the categorization of adjusted calcium values.For patients receiving lithium, some researchers have suggested monitoring PTH as well as calcium.1

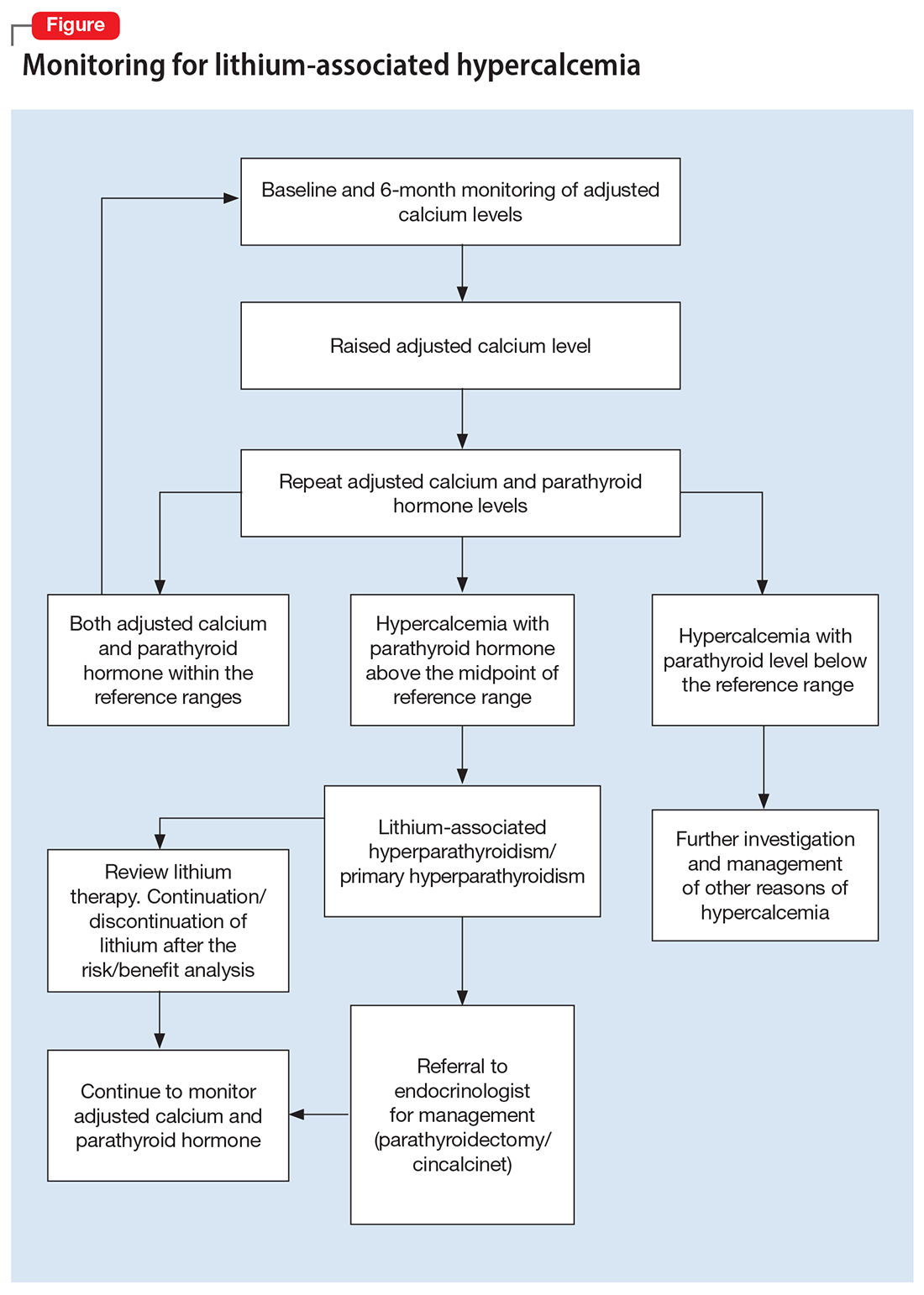

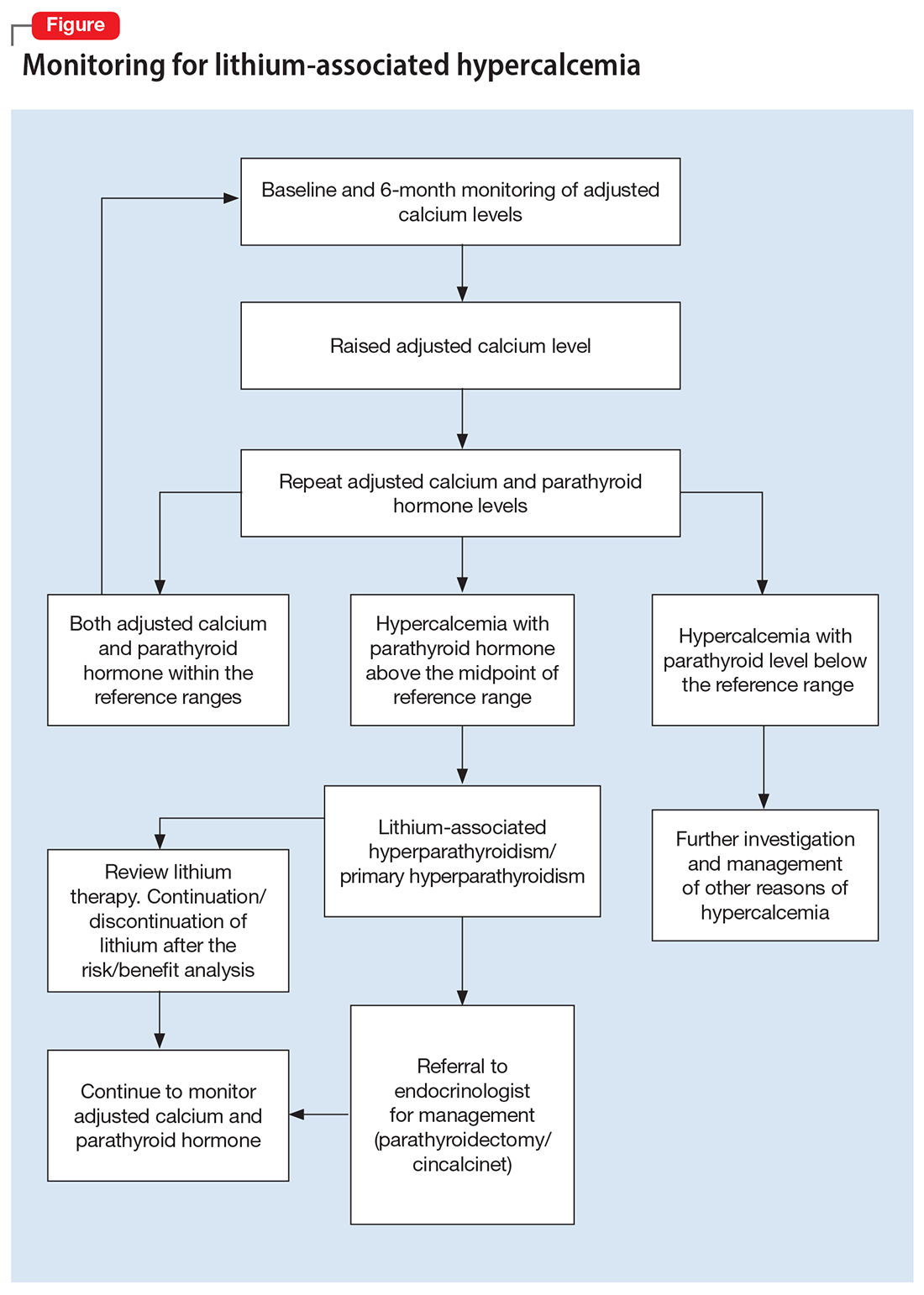

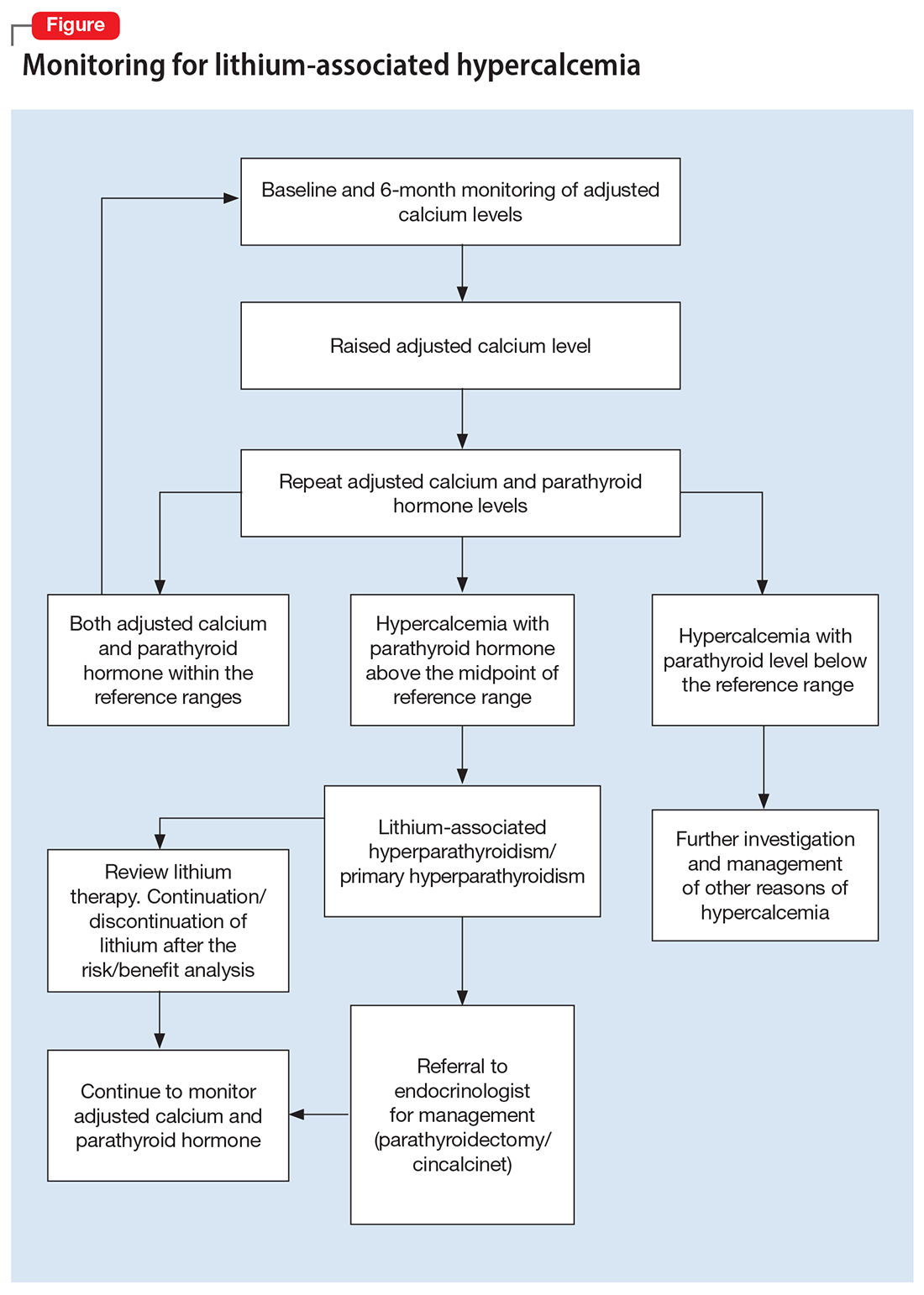

The Figure outlines our proposed approach to monitoring for LAH in patients receiving lithium. An isolated high value of calcium could be due to prolonged venous stasis if a tourniquet is used for phlebotomy. In such instances, the calcium level should be tested again without a tourniquet.10 If the repeat blood test shows elevated calcium levels, then both PTH and serum calcium should be tested.

If the PTH level is higher than the midpoint of the reference range, LAH should be suspected, though sometimes hypercalcemia can present without raised PTH. LAH has also been reported to cause a transient increase in calcium levels. If hypercalcemia frequently recurs, PTH levels should be monitored. If PTH is suppressed, then the raised calcium levels are probably secondary to something other than lithium; common reasons for this include the use of vitamin D supplements or thiazide diuretics, or malignancies such as multiple myeloma.3,5,8

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment: Continue lithium?

There are several options for treating LAH. Lithium may be continued or discontinued following close monitoring of calcium and PTH levels, with or without active interventions such as surgery or pharmacotherapy, and as deemed appropriate after consultation with an endocrinologist. The decision should be informed by evaluating the risks and benefits to the patient’s physical and mental health. LAH can be reversed by discontinuing lithium, but this might not be the case in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy, especially if their elevated calcium levels are associated with parathyroid adenomas or hyperplasia. Hence, close monitoring of calcium and PTH is required even after discontinuing lithium.3,8

Surgical treatment. The primary treatment of LAH and primary hyperparathyroidism is parathyroidectomy. The possibility of recovery after parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism is 60% to 80%, though a small proportion of patients might experience recurrence. This figure might be higher for LAH, because it is more likely to affect multiple glands.1,11 Other potential complications of parathyroidectomy are recurrent laryngeal nerve injury causing paralysis of vocal cords leading to hoarseness of voice, stridor, or aspiration, and local hematoma and hypocalcemia (requiring vitamin D and/or calcium supplements).12

Pharmacotherapy. Cinacalcet is a calcimimetic drug that decreases the reset point of the calcium-sensing receptor. It can be used if a patient is not suitable for or apprehensive about surgical intervention.1,8

Bottom Line

Calcium levels should be regularly monitored in patients receiving lithium. If calcium levels are persistently high, parathyroid hormone levels should also be measured. Management of lithium-associated hypercalcemia includes watchful waiting, discontinuing lithium, parathyroidectomy, and pharmacotherapy with cinacalcet.

Related Resources

- Laski M, Foreman R, Hancock H, et al. Lithium: an underutilized element. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(12):27-30,34. doi:10.12788/cp.0193

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Cinacalcet • Sensipar

1. Meehan AD, Udumyan R, Kardell M, et al. Lithium-associated hypercalcemia: pathophysiology, prevalence, management. World J Surg. 2018;42(2):415-424.

2. McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721-728.

3. Shapiro HI, Davis KA. Hypercalcemia and “primary” hyperparathyroidism during lithium therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):12-15.

4. Lerena VS, León NS, Sosa S, et al. Lithium and endocrine dysfunction. Medicina (B Aires). 2022;82(1):130-137.

5. Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(9):1959-1966.

6. Yeh MW, Ituarte PH, Zhou HC, et al. Incidence and prevalence of primary hyperparathyroidism in a racially mixed population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):1122-1129.

7. Dandurand K, Ali DS, Khan AA. Primary hyperparathyroidism: a narrative review of diagnosis and medical management. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1604.

8. Mifsud S, Cilia K, Mifsud EL, et al. Lithium-associated hyperparathyroidism. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2020;81(11):1-9.

9. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

10. Mieebi WM, Solomon AE, Wabote AP. The effect of tourniquet application on serum calcium and inorganic phosphorus determination. Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing. 2019;65:51-54.

11. Awad SS, Miskulin J, Thompson N. Parathyroid adenomas versus four-gland hyperplasia as the cause of primary hyperparathyroidism in patients with prolonged lithium therapy. World J Surg. 2003;27(4):486-488.

12. Farndon JR. Postoperative complications of parathyroidectomy. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. Accessed October 25, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6967

Hypercalcemia is a well-known but underrecognized adverse effect of lithium. Most patients with lithium-associated hypercalcemia (LAH) have either nonspecific symptoms (eg, persistent tiredness, constipation, polyuria, polydipsia) or no symptoms. Clinically, LAH differs from primary hyperparathyroidism, though the management protocol of these 2 conditions is almost the same. In this article, we discuss how lithium can affect calcium and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels and how LAH and lithium-associated hyperparathyroidism (LAHP) differs from primary hyperparathyroidism. We also outline a suggested approach to monitoring and management.

An insidious problem

Due to the varying definitions and methods used to assess hypercalcemia, the reported prevalence of LAH varies from 4.3% to 80%.1 McKnight et al2 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of the relationship between lithium and parathyroid function that included 14 case-control studies, 36 case reports, and 6 cross-sectional studies without a control group. They found that the levels of calcium and PTH were 10% higher in lithium-treated patients than in controls.2

Pathophysiology. Lithium is known to increase both calcium and PTH levels. PTH is responsible for calcium homeostasis. It is secreted in response to low calcium levels, which it increases by its action on bones, intestines, and kidneys. Vitamin D also plays a crucial role in calcium homeostasis. A deficiency of vitamin D triggers a compensatory increase in PTH to maintain calcium levels.3

Calcium and PTH levels increase soon after administration of lithium, but the rise is usually mild and insidious. In a small proportion of patients who receive long-term lithium treatment, calcium levels can exceed the normal range. Patients who develop LAH typically have serum calcium levels slightly above the normal range and PTH levels ranging from the higher side of the normal range to several times the upper limit of the normal range. Patients might also experience elevated PTH levels without any increase in calcium levels. Lithium can affect calcium and PTH levels in multiple ways. For instance, it increases the reabsorption of calcium in the kidney as well as the reset point of calcium-sensing receptors. Therefore, only higher levels of calcium can inhibit the release of PTH. Hence, in cases where the PTH level is within the normal range, it is generally higher than would be expected for a given serum calcium level. Lithium can also directly affect the parathyroid glands and can lead to either single-nodule or multimodule hyperplasia.4

Long-term lithium use can cause chronic kidney disease (CKD), which in turn leads to vitamin D deficiency and hyperparathyroidism. However, secondary hyperparathyroidism with CKD is usually seen in the more advanced stages of CKD, and is associated with low-to-normal calcium levels (as opposed to the high levels seen in LAH).3-5

Lithium-associated hyperparathyroidism

Primary hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of hypercalcemia. Its prevalence ranges from 1 to 7 cases per 1,000 adults. The incidence of LAH/LAHP is 4- to 6-fold higher compared to the general population.6 Similar to LAH/LAHP, primary hyperparathyroidism is more common in older adults (age >60) and females. Hence, some researchers have suggested that lithium probably unmasks hyperparathyroidism in patients who are susceptible to primary hyperparathyroidism.3

Look for these clinical manifestations

Symptoms of primary hyperparathyroidism are related to high calcium and PTH levels. They are commonly described as “painful bones, renal stones, abdominal groans (due to hypercalcemia-induced ileus), and psychic moans (lethargy, poor concentration, depression).” Common adverse outcomes associated with primary hyperparathyroidism are renal stones, high risk of fracture, constipation, peptic ulcer, and pancreatitis.3,7

Continue: In contrast...

In contrast, LAHP is characterized by mild, intermittent, and/or persistent hypercalcemia and mildly increased PTH (Table 1).1,3,4 In some patients, it could improve without active intervention. Because lithium increases the absorption of urinary calcium, it is associated with hypocalciuria and a lower risk of renal stones. Additionally, lithium has osteoprotective effects and has not been associated with an increased risk of fracture. Some researchers have suggested that the presentation of LAHP is more like familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHC), which is also associated with hypocalciuria. FHC is a benign condition and does not require active intervention.3,4 Similar to those with FHC, many patients with LAHP may live with chronic asymptomatic hypercalcemia without any significant adverse outcome.

A suggested approach to monitoring

In most cases, LAH is an insidious adverse effect that is usually detected on blood tests after many years of lithium therapy.8 For patients starting lithium therapy, International Society of Bipolar Disorder guidelines recommend testing calcium levels at baseline, 6 months, and annually thereafter, or as clinically indicated, to detect and monitor hypercalcemia and hyperparathyroidism. However, these guidelines do not provide any recommendations regarding how to manage abnormal findings.9

Clinical laboratories report both total and adjusted calcium values. The adjusted calcium value takes into account albumin levels. This is a way to compensate for an abnormal concentration of albumin (establishing what a patient’s total calcium concentration would be if the albumin concentration was normal). Table 25 shows the categorization of adjusted calcium values.For patients receiving lithium, some researchers have suggested monitoring PTH as well as calcium.1

The Figure outlines our proposed approach to monitoring for LAH in patients receiving lithium. An isolated high value of calcium could be due to prolonged venous stasis if a tourniquet is used for phlebotomy. In such instances, the calcium level should be tested again without a tourniquet.10 If the repeat blood test shows elevated calcium levels, then both PTH and serum calcium should be tested.

If the PTH level is higher than the midpoint of the reference range, LAH should be suspected, though sometimes hypercalcemia can present without raised PTH. LAH has also been reported to cause a transient increase in calcium levels. If hypercalcemia frequently recurs, PTH levels should be monitored. If PTH is suppressed, then the raised calcium levels are probably secondary to something other than lithium; common reasons for this include the use of vitamin D supplements or thiazide diuretics, or malignancies such as multiple myeloma.3,5,8

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment: Continue lithium?

There are several options for treating LAH. Lithium may be continued or discontinued following close monitoring of calcium and PTH levels, with or without active interventions such as surgery or pharmacotherapy, and as deemed appropriate after consultation with an endocrinologist. The decision should be informed by evaluating the risks and benefits to the patient’s physical and mental health. LAH can be reversed by discontinuing lithium, but this might not be the case in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy, especially if their elevated calcium levels are associated with parathyroid adenomas or hyperplasia. Hence, close monitoring of calcium and PTH is required even after discontinuing lithium.3,8

Surgical treatment. The primary treatment of LAH and primary hyperparathyroidism is parathyroidectomy. The possibility of recovery after parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism is 60% to 80%, though a small proportion of patients might experience recurrence. This figure might be higher for LAH, because it is more likely to affect multiple glands.1,11 Other potential complications of parathyroidectomy are recurrent laryngeal nerve injury causing paralysis of vocal cords leading to hoarseness of voice, stridor, or aspiration, and local hematoma and hypocalcemia (requiring vitamin D and/or calcium supplements).12

Pharmacotherapy. Cinacalcet is a calcimimetic drug that decreases the reset point of the calcium-sensing receptor. It can be used if a patient is not suitable for or apprehensive about surgical intervention.1,8

Bottom Line

Calcium levels should be regularly monitored in patients receiving lithium. If calcium levels are persistently high, parathyroid hormone levels should also be measured. Management of lithium-associated hypercalcemia includes watchful waiting, discontinuing lithium, parathyroidectomy, and pharmacotherapy with cinacalcet.

Related Resources

- Laski M, Foreman R, Hancock H, et al. Lithium: an underutilized element. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(12):27-30,34. doi:10.12788/cp.0193

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Cinacalcet • Sensipar

Hypercalcemia is a well-known but underrecognized adverse effect of lithium. Most patients with lithium-associated hypercalcemia (LAH) have either nonspecific symptoms (eg, persistent tiredness, constipation, polyuria, polydipsia) or no symptoms. Clinically, LAH differs from primary hyperparathyroidism, though the management protocol of these 2 conditions is almost the same. In this article, we discuss how lithium can affect calcium and parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels and how LAH and lithium-associated hyperparathyroidism (LAHP) differs from primary hyperparathyroidism. We also outline a suggested approach to monitoring and management.

An insidious problem

Due to the varying definitions and methods used to assess hypercalcemia, the reported prevalence of LAH varies from 4.3% to 80%.1 McKnight et al2 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of the relationship between lithium and parathyroid function that included 14 case-control studies, 36 case reports, and 6 cross-sectional studies without a control group. They found that the levels of calcium and PTH were 10% higher in lithium-treated patients than in controls.2

Pathophysiology. Lithium is known to increase both calcium and PTH levels. PTH is responsible for calcium homeostasis. It is secreted in response to low calcium levels, which it increases by its action on bones, intestines, and kidneys. Vitamin D also plays a crucial role in calcium homeostasis. A deficiency of vitamin D triggers a compensatory increase in PTH to maintain calcium levels.3

Calcium and PTH levels increase soon after administration of lithium, but the rise is usually mild and insidious. In a small proportion of patients who receive long-term lithium treatment, calcium levels can exceed the normal range. Patients who develop LAH typically have serum calcium levels slightly above the normal range and PTH levels ranging from the higher side of the normal range to several times the upper limit of the normal range. Patients might also experience elevated PTH levels without any increase in calcium levels. Lithium can affect calcium and PTH levels in multiple ways. For instance, it increases the reabsorption of calcium in the kidney as well as the reset point of calcium-sensing receptors. Therefore, only higher levels of calcium can inhibit the release of PTH. Hence, in cases where the PTH level is within the normal range, it is generally higher than would be expected for a given serum calcium level. Lithium can also directly affect the parathyroid glands and can lead to either single-nodule or multimodule hyperplasia.4

Long-term lithium use can cause chronic kidney disease (CKD), which in turn leads to vitamin D deficiency and hyperparathyroidism. However, secondary hyperparathyroidism with CKD is usually seen in the more advanced stages of CKD, and is associated with low-to-normal calcium levels (as opposed to the high levels seen in LAH).3-5

Lithium-associated hyperparathyroidism

Primary hyperparathyroidism is the most common cause of hypercalcemia. Its prevalence ranges from 1 to 7 cases per 1,000 adults. The incidence of LAH/LAHP is 4- to 6-fold higher compared to the general population.6 Similar to LAH/LAHP, primary hyperparathyroidism is more common in older adults (age >60) and females. Hence, some researchers have suggested that lithium probably unmasks hyperparathyroidism in patients who are susceptible to primary hyperparathyroidism.3

Look for these clinical manifestations

Symptoms of primary hyperparathyroidism are related to high calcium and PTH levels. They are commonly described as “painful bones, renal stones, abdominal groans (due to hypercalcemia-induced ileus), and psychic moans (lethargy, poor concentration, depression).” Common adverse outcomes associated with primary hyperparathyroidism are renal stones, high risk of fracture, constipation, peptic ulcer, and pancreatitis.3,7

Continue: In contrast...

In contrast, LAHP is characterized by mild, intermittent, and/or persistent hypercalcemia and mildly increased PTH (Table 1).1,3,4 In some patients, it could improve without active intervention. Because lithium increases the absorption of urinary calcium, it is associated with hypocalciuria and a lower risk of renal stones. Additionally, lithium has osteoprotective effects and has not been associated with an increased risk of fracture. Some researchers have suggested that the presentation of LAHP is more like familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia (FHC), which is also associated with hypocalciuria. FHC is a benign condition and does not require active intervention.3,4 Similar to those with FHC, many patients with LAHP may live with chronic asymptomatic hypercalcemia without any significant adverse outcome.

A suggested approach to monitoring

In most cases, LAH is an insidious adverse effect that is usually detected on blood tests after many years of lithium therapy.8 For patients starting lithium therapy, International Society of Bipolar Disorder guidelines recommend testing calcium levels at baseline, 6 months, and annually thereafter, or as clinically indicated, to detect and monitor hypercalcemia and hyperparathyroidism. However, these guidelines do not provide any recommendations regarding how to manage abnormal findings.9

Clinical laboratories report both total and adjusted calcium values. The adjusted calcium value takes into account albumin levels. This is a way to compensate for an abnormal concentration of albumin (establishing what a patient’s total calcium concentration would be if the albumin concentration was normal). Table 25 shows the categorization of adjusted calcium values.For patients receiving lithium, some researchers have suggested monitoring PTH as well as calcium.1

The Figure outlines our proposed approach to monitoring for LAH in patients receiving lithium. An isolated high value of calcium could be due to prolonged venous stasis if a tourniquet is used for phlebotomy. In such instances, the calcium level should be tested again without a tourniquet.10 If the repeat blood test shows elevated calcium levels, then both PTH and serum calcium should be tested.

If the PTH level is higher than the midpoint of the reference range, LAH should be suspected, though sometimes hypercalcemia can present without raised PTH. LAH has also been reported to cause a transient increase in calcium levels. If hypercalcemia frequently recurs, PTH levels should be monitored. If PTH is suppressed, then the raised calcium levels are probably secondary to something other than lithium; common reasons for this include the use of vitamin D supplements or thiazide diuretics, or malignancies such as multiple myeloma.3,5,8

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment: Continue lithium?

There are several options for treating LAH. Lithium may be continued or discontinued following close monitoring of calcium and PTH levels, with or without active interventions such as surgery or pharmacotherapy, and as deemed appropriate after consultation with an endocrinologist. The decision should be informed by evaluating the risks and benefits to the patient’s physical and mental health. LAH can be reversed by discontinuing lithium, but this might not be the case in patients receiving long-term lithium therapy, especially if their elevated calcium levels are associated with parathyroid adenomas or hyperplasia. Hence, close monitoring of calcium and PTH is required even after discontinuing lithium.3,8

Surgical treatment. The primary treatment of LAH and primary hyperparathyroidism is parathyroidectomy. The possibility of recovery after parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism is 60% to 80%, though a small proportion of patients might experience recurrence. This figure might be higher for LAH, because it is more likely to affect multiple glands.1,11 Other potential complications of parathyroidectomy are recurrent laryngeal nerve injury causing paralysis of vocal cords leading to hoarseness of voice, stridor, or aspiration, and local hematoma and hypocalcemia (requiring vitamin D and/or calcium supplements).12

Pharmacotherapy. Cinacalcet is a calcimimetic drug that decreases the reset point of the calcium-sensing receptor. It can be used if a patient is not suitable for or apprehensive about surgical intervention.1,8

Bottom Line

Calcium levels should be regularly monitored in patients receiving lithium. If calcium levels are persistently high, parathyroid hormone levels should also be measured. Management of lithium-associated hypercalcemia includes watchful waiting, discontinuing lithium, parathyroidectomy, and pharmacotherapy with cinacalcet.

Related Resources

- Laski M, Foreman R, Hancock H, et al. Lithium: an underutilized element. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(12):27-30,34. doi:10.12788/cp.0193

- Pelekanos M, Foo K. A resident’s guide to lithium. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(4):e3-e7. doi:10.12788/cp.0113

Drug Brand Names

Cinacalcet • Sensipar

1. Meehan AD, Udumyan R, Kardell M, et al. Lithium-associated hypercalcemia: pathophysiology, prevalence, management. World J Surg. 2018;42(2):415-424.

2. McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721-728.

3. Shapiro HI, Davis KA. Hypercalcemia and “primary” hyperparathyroidism during lithium therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):12-15.

4. Lerena VS, León NS, Sosa S, et al. Lithium and endocrine dysfunction. Medicina (B Aires). 2022;82(1):130-137.

5. Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(9):1959-1966.

6. Yeh MW, Ituarte PH, Zhou HC, et al. Incidence and prevalence of primary hyperparathyroidism in a racially mixed population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):1122-1129.

7. Dandurand K, Ali DS, Khan AA. Primary hyperparathyroidism: a narrative review of diagnosis and medical management. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1604.

8. Mifsud S, Cilia K, Mifsud EL, et al. Lithium-associated hyperparathyroidism. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2020;81(11):1-9.

9. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

10. Mieebi WM, Solomon AE, Wabote AP. The effect of tourniquet application on serum calcium and inorganic phosphorus determination. Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing. 2019;65:51-54.

11. Awad SS, Miskulin J, Thompson N. Parathyroid adenomas versus four-gland hyperplasia as the cause of primary hyperparathyroidism in patients with prolonged lithium therapy. World J Surg. 2003;27(4):486-488.

12. Farndon JR. Postoperative complications of parathyroidectomy. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. Accessed October 25, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6967

1. Meehan AD, Udumyan R, Kardell M, et al. Lithium-associated hypercalcemia: pathophysiology, prevalence, management. World J Surg. 2018;42(2):415-424.

2. McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721-728.

3. Shapiro HI, Davis KA. Hypercalcemia and “primary” hyperparathyroidism during lithium therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):12-15.

4. Lerena VS, León NS, Sosa S, et al. Lithium and endocrine dysfunction. Medicina (B Aires). 2022;82(1):130-137.

5. Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(9):1959-1966.

6. Yeh MW, Ituarte PH, Zhou HC, et al. Incidence and prevalence of primary hyperparathyroidism in a racially mixed population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):1122-1129.

7. Dandurand K, Ali DS, Khan AA. Primary hyperparathyroidism: a narrative review of diagnosis and medical management. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1604.

8. Mifsud S, Cilia K, Mifsud EL, et al. Lithium-associated hyperparathyroidism. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2020;81(11):1-9.

9. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97-170.

10. Mieebi WM, Solomon AE, Wabote AP. The effect of tourniquet application on serum calcium and inorganic phosphorus determination. Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing. 2019;65:51-54.

11. Awad SS, Miskulin J, Thompson N. Parathyroid adenomas versus four-gland hyperplasia as the cause of primary hyperparathyroidism in patients with prolonged lithium therapy. World J Surg. 2003;27(4):486-488.

12. Farndon JR. Postoperative complications of parathyroidectomy. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem-Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. Accessed October 25, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK6967

Long-term behavioral follow-up of children exposed to mood stabilizers and antidepressants: A look forward

Much of the focus of reproductive psychiatry over the last 1 to 2 decades has been on issues regarding risk of fetal exposure to psychiatric medications in the context of the specific risk for teratogenesis or organ malformation. Concerns and questions are mostly focused on exposure to any number of medications that women take during the first trimester, as it is during that period that the major organs are formed.

More recently, there has been appropriate interest in the effect of fetal exposure to psychiatric medications with respect to risk for obstetrical and neonatal complications. This particularly has been the case with respect to antidepressants where fetal exposure to these medications, which while associated with symptoms of transient jitteriness and irritability about 20% of the time, have not been associated with symptoms requiring frank clinical intervention.

Concerning mood stabilizers, the risk for organ dysgenesis following fetal exposure to sodium valproate has been very well established, and we’ve known for over a decade about the adverse effects of fetal exposure to sodium valproate on behavioral outcomes (Lancet Neurol. 2013 Mar;12[3]:244-52). We also now have ample data on lamotrigine, one of the most widely used medicines by reproductive-age women for treatment of bipolar disorder that supports the absence of a risk of organ malformation in first-trimester exposure.

Most recently, in a study of 292 children of women with epilepsy, an evaluation of women being treated with more modern anticonvulsants such as lamotrigine and levetiracetam alone or as polytherapy was performed. The results showed no difference in language, motor, cognitive, social, emotional, and general adaptive functioning in children exposed to either lamotrigine or levetiracetam relative to unexposed children of women with epilepsy. However, the researchers found an increase in anti-epileptic drug plasma level appeared to be associated with decreased motor and sensory function. These are reassuring data that really confirm earlier work, which failed to reveal a signal of concern for lamotrigine and now provide some of the first data on levetiracetam, which is widely used by reproductive-age women with epilepsy (JAMA Neurol. 2021 Aug 1;78[8]:927-936). While one caveat of the study is a short follow-up of 2 years, the absence of a signal of concern is reassuring. With more and more data demonstrating bipolar disorder is an illness that requires chronic treatment for many people, and that discontinuation is associated with high risk for relapse, it is an advance in the field to have data on risk for teratogenesis and data on longer-term neurobehavioral outcomes.

There is vast information regarding reproductive safety, organ malformation, and acute neonatal outcomes for antidepressants. The last decade has brought interest in and analysis of specific reports of increased risk of both autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) following fetal exposure to antidepressants. What can be said based on reviews of pooled meta-analyses is that the risk for ASD and ADHD has been put to rest for most clinicians and patients (J Clin Psychiatry. 2020 May 26;81[3]:20f13463). With other neurodevelopmental disorders, results have been somewhat inconclusive. Over the last 5-10 years, there have been sporadic reports of concerns about problems in a specific domain of neurodevelopment in offspring of women who have used antidepressants during pregnancy, whether it be speech, language, or motor functioning, but no signal of concern has been consistent.

In a previous column, I addressed a Danish study that showed no increased risk of longer-term sequelae after fetal exposure to antidepressants. Now, a new study has examined 1.93 million pregnancies in the Medicaid Analytic eXtract and 1.25 million pregnancies in the IBM MarketScan Research Database with follow-up up to 14 years of age where the specific interval for fetal exposure was from gestational age of 19 weeks to delivery, as that is the period that corresponds most to synaptogenesis in the brain. The researchers examined a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders such as developmental speech issues, ADHD, ASD, dyslexia, and learning disorders, among others. They found a twofold increased risk for neurodevelopmental disorders in the unadjusted models that flattened to no finding when factoring in environmental and genetic risk variables, highlighting the importance of dealing appropriately with confounders when performing these analyses. Those confounders examined include the mother’s use of alcohol and tobacco, and her body mass index and overall general health (JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182[11]:1149-60).

Given the consistency of these results with earlier data, patients can be increasingly comfortable as they weigh the benefits and risks of antidepressant use during pregnancy, factoring in the risk of fetal exposure with added data on long-term neurobehavioral sequelae. With that said, we need to remember the importance of initiatives to address alcohol consumption, poor nutrition, tobacco use, elevated BMI, and general health during pregnancy. These are modifiable risks that we as clinicians should focus on in order to optimize outcomes during pregnancy.

We have come so far in knowledge about fetal exposure to antidepressants relative to other classes of medications women take during pregnancy, about which, frankly, we are still starved for data. As use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy continues to grow, we can rest a bit more comfortably. But we should also address some of the other behaviors that have adverse effects on maternal and child well-being.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at obnews@mdedge.com.

Much of the focus of reproductive psychiatry over the last 1 to 2 decades has been on issues regarding risk of fetal exposure to psychiatric medications in the context of the specific risk for teratogenesis or organ malformation. Concerns and questions are mostly focused on exposure to any number of medications that women take during the first trimester, as it is during that period that the major organs are formed.

More recently, there has been appropriate interest in the effect of fetal exposure to psychiatric medications with respect to risk for obstetrical and neonatal complications. This particularly has been the case with respect to antidepressants where fetal exposure to these medications, which while associated with symptoms of transient jitteriness and irritability about 20% of the time, have not been associated with symptoms requiring frank clinical intervention.

Concerning mood stabilizers, the risk for organ dysgenesis following fetal exposure to sodium valproate has been very well established, and we’ve known for over a decade about the adverse effects of fetal exposure to sodium valproate on behavioral outcomes (Lancet Neurol. 2013 Mar;12[3]:244-52). We also now have ample data on lamotrigine, one of the most widely used medicines by reproductive-age women for treatment of bipolar disorder that supports the absence of a risk of organ malformation in first-trimester exposure.

Most recently, in a study of 292 children of women with epilepsy, an evaluation of women being treated with more modern anticonvulsants such as lamotrigine and levetiracetam alone or as polytherapy was performed. The results showed no difference in language, motor, cognitive, social, emotional, and general adaptive functioning in children exposed to either lamotrigine or levetiracetam relative to unexposed children of women with epilepsy. However, the researchers found an increase in anti-epileptic drug plasma level appeared to be associated with decreased motor and sensory function. These are reassuring data that really confirm earlier work, which failed to reveal a signal of concern for lamotrigine and now provide some of the first data on levetiracetam, which is widely used by reproductive-age women with epilepsy (JAMA Neurol. 2021 Aug 1;78[8]:927-936). While one caveat of the study is a short follow-up of 2 years, the absence of a signal of concern is reassuring. With more and more data demonstrating bipolar disorder is an illness that requires chronic treatment for many people, and that discontinuation is associated with high risk for relapse, it is an advance in the field to have data on risk for teratogenesis and data on longer-term neurobehavioral outcomes.

There is vast information regarding reproductive safety, organ malformation, and acute neonatal outcomes for antidepressants. The last decade has brought interest in and analysis of specific reports of increased risk of both autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) following fetal exposure to antidepressants. What can be said based on reviews of pooled meta-analyses is that the risk for ASD and ADHD has been put to rest for most clinicians and patients (J Clin Psychiatry. 2020 May 26;81[3]:20f13463). With other neurodevelopmental disorders, results have been somewhat inconclusive. Over the last 5-10 years, there have been sporadic reports of concerns about problems in a specific domain of neurodevelopment in offspring of women who have used antidepressants during pregnancy, whether it be speech, language, or motor functioning, but no signal of concern has been consistent.

In a previous column, I addressed a Danish study that showed no increased risk of longer-term sequelae after fetal exposure to antidepressants. Now, a new study has examined 1.93 million pregnancies in the Medicaid Analytic eXtract and 1.25 million pregnancies in the IBM MarketScan Research Database with follow-up up to 14 years of age where the specific interval for fetal exposure was from gestational age of 19 weeks to delivery, as that is the period that corresponds most to synaptogenesis in the brain. The researchers examined a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders such as developmental speech issues, ADHD, ASD, dyslexia, and learning disorders, among others. They found a twofold increased risk for neurodevelopmental disorders in the unadjusted models that flattened to no finding when factoring in environmental and genetic risk variables, highlighting the importance of dealing appropriately with confounders when performing these analyses. Those confounders examined include the mother’s use of alcohol and tobacco, and her body mass index and overall general health (JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182[11]:1149-60).

Given the consistency of these results with earlier data, patients can be increasingly comfortable as they weigh the benefits and risks of antidepressant use during pregnancy, factoring in the risk of fetal exposure with added data on long-term neurobehavioral sequelae. With that said, we need to remember the importance of initiatives to address alcohol consumption, poor nutrition, tobacco use, elevated BMI, and general health during pregnancy. These are modifiable risks that we as clinicians should focus on in order to optimize outcomes during pregnancy.

We have come so far in knowledge about fetal exposure to antidepressants relative to other classes of medications women take during pregnancy, about which, frankly, we are still starved for data. As use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy continues to grow, we can rest a bit more comfortably. But we should also address some of the other behaviors that have adverse effects on maternal and child well-being.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at obnews@mdedge.com.

Much of the focus of reproductive psychiatry over the last 1 to 2 decades has been on issues regarding risk of fetal exposure to psychiatric medications in the context of the specific risk for teratogenesis or organ malformation. Concerns and questions are mostly focused on exposure to any number of medications that women take during the first trimester, as it is during that period that the major organs are formed.

More recently, there has been appropriate interest in the effect of fetal exposure to psychiatric medications with respect to risk for obstetrical and neonatal complications. This particularly has been the case with respect to antidepressants where fetal exposure to these medications, which while associated with symptoms of transient jitteriness and irritability about 20% of the time, have not been associated with symptoms requiring frank clinical intervention.

Concerning mood stabilizers, the risk for organ dysgenesis following fetal exposure to sodium valproate has been very well established, and we’ve known for over a decade about the adverse effects of fetal exposure to sodium valproate on behavioral outcomes (Lancet Neurol. 2013 Mar;12[3]:244-52). We also now have ample data on lamotrigine, one of the most widely used medicines by reproductive-age women for treatment of bipolar disorder that supports the absence of a risk of organ malformation in first-trimester exposure.

Most recently, in a study of 292 children of women with epilepsy, an evaluation of women being treated with more modern anticonvulsants such as lamotrigine and levetiracetam alone or as polytherapy was performed. The results showed no difference in language, motor, cognitive, social, emotional, and general adaptive functioning in children exposed to either lamotrigine or levetiracetam relative to unexposed children of women with epilepsy. However, the researchers found an increase in anti-epileptic drug plasma level appeared to be associated with decreased motor and sensory function. These are reassuring data that really confirm earlier work, which failed to reveal a signal of concern for lamotrigine and now provide some of the first data on levetiracetam, which is widely used by reproductive-age women with epilepsy (JAMA Neurol. 2021 Aug 1;78[8]:927-936). While one caveat of the study is a short follow-up of 2 years, the absence of a signal of concern is reassuring. With more and more data demonstrating bipolar disorder is an illness that requires chronic treatment for many people, and that discontinuation is associated with high risk for relapse, it is an advance in the field to have data on risk for teratogenesis and data on longer-term neurobehavioral outcomes.

There is vast information regarding reproductive safety, organ malformation, and acute neonatal outcomes for antidepressants. The last decade has brought interest in and analysis of specific reports of increased risk of both autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) following fetal exposure to antidepressants. What can be said based on reviews of pooled meta-analyses is that the risk for ASD and ADHD has been put to rest for most clinicians and patients (J Clin Psychiatry. 2020 May 26;81[3]:20f13463). With other neurodevelopmental disorders, results have been somewhat inconclusive. Over the last 5-10 years, there have been sporadic reports of concerns about problems in a specific domain of neurodevelopment in offspring of women who have used antidepressants during pregnancy, whether it be speech, language, or motor functioning, but no signal of concern has been consistent.

In a previous column, I addressed a Danish study that showed no increased risk of longer-term sequelae after fetal exposure to antidepressants. Now, a new study has examined 1.93 million pregnancies in the Medicaid Analytic eXtract and 1.25 million pregnancies in the IBM MarketScan Research Database with follow-up up to 14 years of age where the specific interval for fetal exposure was from gestational age of 19 weeks to delivery, as that is the period that corresponds most to synaptogenesis in the brain. The researchers examined a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders such as developmental speech issues, ADHD, ASD, dyslexia, and learning disorders, among others. They found a twofold increased risk for neurodevelopmental disorders in the unadjusted models that flattened to no finding when factoring in environmental and genetic risk variables, highlighting the importance of dealing appropriately with confounders when performing these analyses. Those confounders examined include the mother’s use of alcohol and tobacco, and her body mass index and overall general health (JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182[11]:1149-60).

Given the consistency of these results with earlier data, patients can be increasingly comfortable as they weigh the benefits and risks of antidepressant use during pregnancy, factoring in the risk of fetal exposure with added data on long-term neurobehavioral sequelae. With that said, we need to remember the importance of initiatives to address alcohol consumption, poor nutrition, tobacco use, elevated BMI, and general health during pregnancy. These are modifiable risks that we as clinicians should focus on in order to optimize outcomes during pregnancy.

We have come so far in knowledge about fetal exposure to antidepressants relative to other classes of medications women take during pregnancy, about which, frankly, we are still starved for data. As use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy continues to grow, we can rest a bit more comfortably. But we should also address some of the other behaviors that have adverse effects on maternal and child well-being.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Ammon-Pinizzotto Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, which provides information resources and conducts clinical care and research in reproductive mental health. He has been a consultant to manufacturers of psychiatric medications. Email Dr. Cohen at obnews@mdedge.com.

Machine learning identifies childhood characteristics that predict bipolar disorder

This is the first quantitative approach to predict bipolar disorder, offering sensitivity and specificity of 75% and 76%, respectively, reported lead author Mai Uchida, MD, director of the pediatric depression program at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. With further development, the model could be used to identify at-risk children via electronic medical records, enabling earlier monitoring and intervention.

“Although longitudinal studies have found the prognosis of early-onset mood disorders to be unfavorable, research has also shown there are effective treatments and therapies that could significantly alleviate the patients’ and their families’ struggles from the diagnoses,” the investigators wrote in the Journal of Psychiatric Research. “Thus, early identification of the risks and interventions for early symptoms of pediatric mood disorders is crucial.”

To this end, Dr. Uchida and colleagues teamed up with the Gabrieli Lab at MIT, who have published extensively in the realm of neurodevelopment. They sourced data from 492 children, 6-18 years at baseline, who were involved in two longitudinal case-control family studies focused on ADHD. Inputs included psychometric scales, structured diagnostic interviews, social and cognitive functioning assessments, and sociodemographic data.

At 10-year follow-up, 10% of these children had developed bipolar disorder, a notably higher rate than the 3%-4% prevalence in the general population.

“This is a population that’s overrepresented,” Dr. Uchida said in an interview.

She offered two primary reasons for this: First, the families involved in the study were probably willing to be followed for 10 years because they had ongoing concerns about their child’s mental health. Second, the studies enrolled children diagnosed with ADHD, a condition associated with increased risk of bipolar disorder.

Using machine learning algorithms that processed the baseline data while accounting for the skewed distribution, the investigators were able to predict which of the children in the population would go on to develop bipolar disorder. The final model offered a sensitivity of 75%, a specificity of 76%, and an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 75%.

“To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first study using machine-learning algorithms for this purpose in pediatric psychiatry,” the investigators wrote.

Integrating models into electronic medical records

In the future, this model, or one like it, could be incorporated into software that automatically analyzes electronic medical records and notifies physicians about high-risk patients, Dr. Uchida predicted.

“Not all patients would connect to intervention,” she said. “Maybe it just means that you invite them in for a visit, or you observe them a little bit more carefully. I think that’s where we are hoping that machine learning and medical practice will go.”

When asked about the potential bias posed by psychiatric evaluation, compared with something like blood work results, Dr. Uchida suggested that this subjectivity can be overcome.

“I’m not entirely bothered by that,” she said, offering a list of objective data points that could be harvested from records, such as number of referrals, medications, and hospitalizations. Narrative text in medical records could also be analyzed, she said, potentially detecting key words that are more often associated with high-risk patients.

“Risk prediction is never going to be 100% accurate,” Dr. Uchida said. “But I do think that there will be things [in electronic medical records] that could guide how worried we should be, or how quickly we should intervene.”

Opening doors to personalized care

Martin Gignac, MD, chief of psychiatry at Montreal Children’s Hospital and associate professor at McGill University, Montreal, said the present study offers further support for the existence of pediatric-onset bipolar disorder, which “remains controversial” despite “solid evidence.”

“I’m impressed that we have 10-year-long longitudinal follow-up studies that corroborate the importance of this disorder, and show strong predictors of who is at risk,” Dr. Gignac said in an interview. “Clinicians treating a pediatric population should be aware that some of those children with mental health problems might have severe mental health problems, and you have to have the appropriate tools to screen them.”

Advanced tools like the one developed by Dr. Uchida and colleagues should lead to more personalized care, he said.

“We’re going to be able to define what your individual risk is, and maybe most importantly, what you can do to prevent the development of certain disorders,” Dr. Gignac said. “Are there any risks that are dynamic in nature, and that we can act upon? Exposure to stress, for example.”

While more work is needed to bring machine learning into daily psychiatric practice, Dr. Gignac concluded on an optimistic note.

“These instruments should translate from research into clinical practice in order to make difference for the patients we care for,” he said. “This is the type of hope that I hold – that it’s going to be applicable in clinical practice, hopefully, in the near future.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with InCarda, Baylis Medical, Johnson & Johnson, and others. Dr. Gignac disclosed no relevant competing interests.

This is the first quantitative approach to predict bipolar disorder, offering sensitivity and specificity of 75% and 76%, respectively, reported lead author Mai Uchida, MD, director of the pediatric depression program at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. With further development, the model could be used to identify at-risk children via electronic medical records, enabling earlier monitoring and intervention.

“Although longitudinal studies have found the prognosis of early-onset mood disorders to be unfavorable, research has also shown there are effective treatments and therapies that could significantly alleviate the patients’ and their families’ struggles from the diagnoses,” the investigators wrote in the Journal of Psychiatric Research. “Thus, early identification of the risks and interventions for early symptoms of pediatric mood disorders is crucial.”

To this end, Dr. Uchida and colleagues teamed up with the Gabrieli Lab at MIT, who have published extensively in the realm of neurodevelopment. They sourced data from 492 children, 6-18 years at baseline, who were involved in two longitudinal case-control family studies focused on ADHD. Inputs included psychometric scales, structured diagnostic interviews, social and cognitive functioning assessments, and sociodemographic data.

At 10-year follow-up, 10% of these children had developed bipolar disorder, a notably higher rate than the 3%-4% prevalence in the general population.

“This is a population that’s overrepresented,” Dr. Uchida said in an interview.

She offered two primary reasons for this: First, the families involved in the study were probably willing to be followed for 10 years because they had ongoing concerns about their child’s mental health. Second, the studies enrolled children diagnosed with ADHD, a condition associated with increased risk of bipolar disorder.

Using machine learning algorithms that processed the baseline data while accounting for the skewed distribution, the investigators were able to predict which of the children in the population would go on to develop bipolar disorder. The final model offered a sensitivity of 75%, a specificity of 76%, and an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 75%.

“To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first study using machine-learning algorithms for this purpose in pediatric psychiatry,” the investigators wrote.

Integrating models into electronic medical records

In the future, this model, or one like it, could be incorporated into software that automatically analyzes electronic medical records and notifies physicians about high-risk patients, Dr. Uchida predicted.

“Not all patients would connect to intervention,” she said. “Maybe it just means that you invite them in for a visit, or you observe them a little bit more carefully. I think that’s where we are hoping that machine learning and medical practice will go.”

When asked about the potential bias posed by psychiatric evaluation, compared with something like blood work results, Dr. Uchida suggested that this subjectivity can be overcome.

“I’m not entirely bothered by that,” she said, offering a list of objective data points that could be harvested from records, such as number of referrals, medications, and hospitalizations. Narrative text in medical records could also be analyzed, she said, potentially detecting key words that are more often associated with high-risk patients.

“Risk prediction is never going to be 100% accurate,” Dr. Uchida said. “But I do think that there will be things [in electronic medical records] that could guide how worried we should be, or how quickly we should intervene.”

Opening doors to personalized care

Martin Gignac, MD, chief of psychiatry at Montreal Children’s Hospital and associate professor at McGill University, Montreal, said the present study offers further support for the existence of pediatric-onset bipolar disorder, which “remains controversial” despite “solid evidence.”

“I’m impressed that we have 10-year-long longitudinal follow-up studies that corroborate the importance of this disorder, and show strong predictors of who is at risk,” Dr. Gignac said in an interview. “Clinicians treating a pediatric population should be aware that some of those children with mental health problems might have severe mental health problems, and you have to have the appropriate tools to screen them.”

Advanced tools like the one developed by Dr. Uchida and colleagues should lead to more personalized care, he said.

“We’re going to be able to define what your individual risk is, and maybe most importantly, what you can do to prevent the development of certain disorders,” Dr. Gignac said. “Are there any risks that are dynamic in nature, and that we can act upon? Exposure to stress, for example.”

While more work is needed to bring machine learning into daily psychiatric practice, Dr. Gignac concluded on an optimistic note.

“These instruments should translate from research into clinical practice in order to make difference for the patients we care for,” he said. “This is the type of hope that I hold – that it’s going to be applicable in clinical practice, hopefully, in the near future.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with InCarda, Baylis Medical, Johnson & Johnson, and others. Dr. Gignac disclosed no relevant competing interests.

This is the first quantitative approach to predict bipolar disorder, offering sensitivity and specificity of 75% and 76%, respectively, reported lead author Mai Uchida, MD, director of the pediatric depression program at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues. With further development, the model could be used to identify at-risk children via electronic medical records, enabling earlier monitoring and intervention.

“Although longitudinal studies have found the prognosis of early-onset mood disorders to be unfavorable, research has also shown there are effective treatments and therapies that could significantly alleviate the patients’ and their families’ struggles from the diagnoses,” the investigators wrote in the Journal of Psychiatric Research. “Thus, early identification of the risks and interventions for early symptoms of pediatric mood disorders is crucial.”

To this end, Dr. Uchida and colleagues teamed up with the Gabrieli Lab at MIT, who have published extensively in the realm of neurodevelopment. They sourced data from 492 children, 6-18 years at baseline, who were involved in two longitudinal case-control family studies focused on ADHD. Inputs included psychometric scales, structured diagnostic interviews, social and cognitive functioning assessments, and sociodemographic data.

At 10-year follow-up, 10% of these children had developed bipolar disorder, a notably higher rate than the 3%-4% prevalence in the general population.

“This is a population that’s overrepresented,” Dr. Uchida said in an interview.

She offered two primary reasons for this: First, the families involved in the study were probably willing to be followed for 10 years because they had ongoing concerns about their child’s mental health. Second, the studies enrolled children diagnosed with ADHD, a condition associated with increased risk of bipolar disorder.

Using machine learning algorithms that processed the baseline data while accounting for the skewed distribution, the investigators were able to predict which of the children in the population would go on to develop bipolar disorder. The final model offered a sensitivity of 75%, a specificity of 76%, and an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 75%.

“To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first study using machine-learning algorithms for this purpose in pediatric psychiatry,” the investigators wrote.

Integrating models into electronic medical records

In the future, this model, or one like it, could be incorporated into software that automatically analyzes electronic medical records and notifies physicians about high-risk patients, Dr. Uchida predicted.

“Not all patients would connect to intervention,” she said. “Maybe it just means that you invite them in for a visit, or you observe them a little bit more carefully. I think that’s where we are hoping that machine learning and medical practice will go.”

When asked about the potential bias posed by psychiatric evaluation, compared with something like blood work results, Dr. Uchida suggested that this subjectivity can be overcome.

“I’m not entirely bothered by that,” she said, offering a list of objective data points that could be harvested from records, such as number of referrals, medications, and hospitalizations. Narrative text in medical records could also be analyzed, she said, potentially detecting key words that are more often associated with high-risk patients.

“Risk prediction is never going to be 100% accurate,” Dr. Uchida said. “But I do think that there will be things [in electronic medical records] that could guide how worried we should be, or how quickly we should intervene.”

Opening doors to personalized care

Martin Gignac, MD, chief of psychiatry at Montreal Children’s Hospital and associate professor at McGill University, Montreal, said the present study offers further support for the existence of pediatric-onset bipolar disorder, which “remains controversial” despite “solid evidence.”

“I’m impressed that we have 10-year-long longitudinal follow-up studies that corroborate the importance of this disorder, and show strong predictors of who is at risk,” Dr. Gignac said in an interview. “Clinicians treating a pediatric population should be aware that some of those children with mental health problems might have severe mental health problems, and you have to have the appropriate tools to screen them.”

Advanced tools like the one developed by Dr. Uchida and colleagues should lead to more personalized care, he said.

“We’re going to be able to define what your individual risk is, and maybe most importantly, what you can do to prevent the development of certain disorders,” Dr. Gignac said. “Are there any risks that are dynamic in nature, and that we can act upon? Exposure to stress, for example.”

While more work is needed to bring machine learning into daily psychiatric practice, Dr. Gignac concluded on an optimistic note.

“These instruments should translate from research into clinical practice in order to make difference for the patients we care for,” he said. “This is the type of hope that I hold – that it’s going to be applicable in clinical practice, hopefully, in the near future.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with InCarda, Baylis Medical, Johnson & Johnson, and others. Dr. Gignac disclosed no relevant competing interests.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRIC RESEARCH

Lamotrigine for bipolar depression?

In reading Dr. Nasrallah's August 2022 editorial (“Reversing depression: A plethora of therapeutic strategies and mechanisms,”

Dr. Nasrallah responds