User login

Preparing patients with serious mental illness for extreme HEAT

Climate change is causing intense heat waves that threaten human health across the globe.

A confluence of factors increases risk

Thermoregulatory dysfunction is thought to be intrinsic to patients with schizophrenia partly due to dysregulated dopaminergic neurotransmission.2 This is compounded by these patients’ higher burden of chronic medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, which together with psychotropic (ie, antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines) and medical medications (ie, certain antihypertensives, diuretics, treatment for urinary incontinence) further disrupt the body’s cooling strategies and increase vulnerability to heat-related illnesses.1,3 Antipsychotics commonly prescribed to patients with SMI increase hyperthermia risk largely by 2 mechanisms: central and peripheral thermal dysregulation, and anticholinergic properties (ie, olanzapine, clozapine, chlorpromazine).2,3 Other anticholinergic medications prescribed to treat extrapyramidal symptoms (ie, diphenhydramine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl), anxiety, depression, and insomnia (ie, paroxetine, trazodone, doxepin) further add insult to injury because they impair sweating, which decreases the body’s ability to eliminate heat through evaporation.2,3 Additionally, high temperature exacerbates psychiatric symptoms in patients with SMI, resulting in increased hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

How to keep patients safe

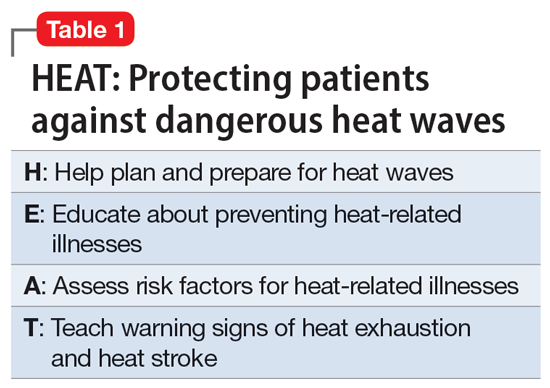

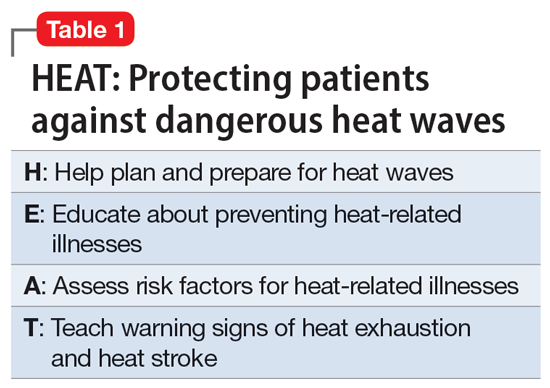

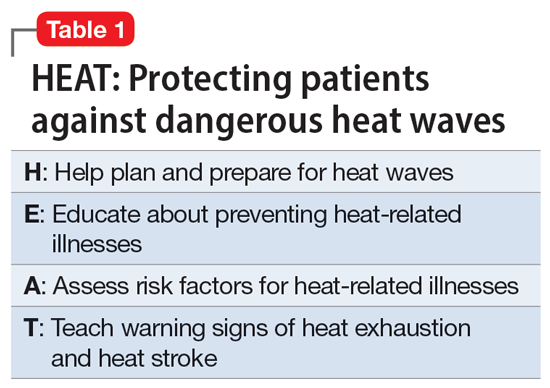

The acronym HEAT provides a framework that psychiatrists can use to highlight the importance of planning for heat waves in their institution and guiding discussions with individual patients about heat-related illnesses (Table 1).

Help the health care system where you work plan and prepare for heat waves. In-service training in mental health settings such as outpatient clinics, shelters, group homes, and residential programs can help staff identify patients at particular risk and reinforce key prevention messages.

Educate patients and their caregivers on strategies for preventing heat-related illness. Informational materials can be distributed in clinics, residential settings, and day programs. A 1-page downloadable pamphlet available at https://smiadviser.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SMI-Heat-Stroke-ver1.0-FINAL.pdf summarizes key prevention messages of staying hydrated, staying cool, and staying safe.

Assess personalized heat-related risks. Inquire about patients’ daily activities, access to air conditioning, and water intake. Minimize the use of anticholinergic medications. Identify who patients can turn to for assistance, especially for those who struggle with cognitive impairment and social isolation.

Teach patients, caregivers, and staff the signs and symptoms of heat exhaustion and heat stroke and how to respond in such situations.

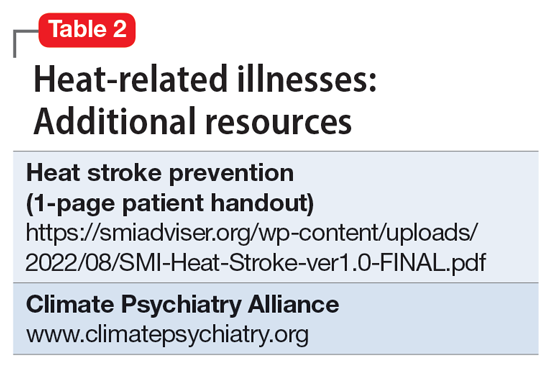

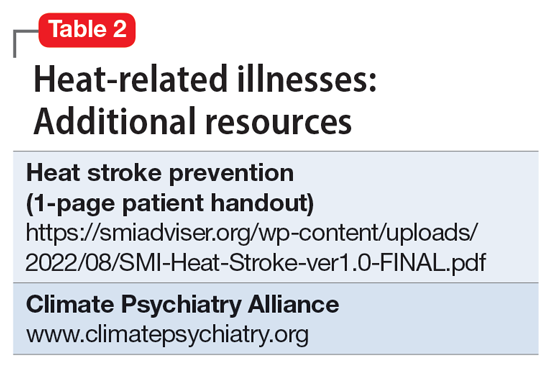

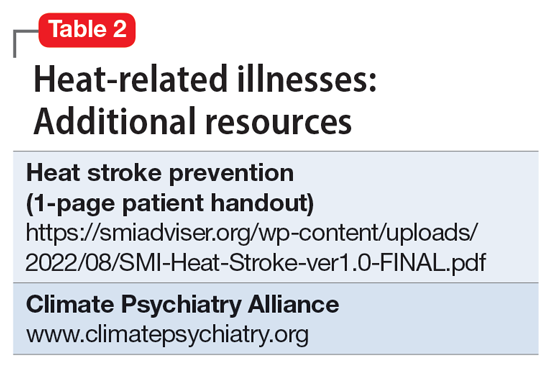

HEAT focuses psychiatric clinicians on preparing and protecting patients with SMI against dangerous heat waves. Clinicians can take a proactive leadership role in disseminating basic principles of heat-related illness prevention and heat-wave toolkits by using resources available from organizations such as the Climate Psychiatry Alliance (Table 2). They can also initiate advocacy efforts to raise awareness about the elevated risks of heat-related illnesses in this vulnerable population.

1. Schmeltz MT, Gamble JL. Risk characterization of hospitalizations for mental illness and/or behavioral disorders with concurrent heat-related illness. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186509. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186509

2. Lee CP, Chen PJ, Chang CM. Heat stroke during treatment with olanzapine, trihexyphenidyl, and trazodone in a patient with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2015;27(6):380-385.

3. Bongers KS, Salahudeen MS, Peterson GM. Drug-associated non-pyrogenic hyperthermia: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(1):9-16.

Climate change is causing intense heat waves that threaten human health across the globe.

A confluence of factors increases risk

Thermoregulatory dysfunction is thought to be intrinsic to patients with schizophrenia partly due to dysregulated dopaminergic neurotransmission.2 This is compounded by these patients’ higher burden of chronic medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, which together with psychotropic (ie, antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines) and medical medications (ie, certain antihypertensives, diuretics, treatment for urinary incontinence) further disrupt the body’s cooling strategies and increase vulnerability to heat-related illnesses.1,3 Antipsychotics commonly prescribed to patients with SMI increase hyperthermia risk largely by 2 mechanisms: central and peripheral thermal dysregulation, and anticholinergic properties (ie, olanzapine, clozapine, chlorpromazine).2,3 Other anticholinergic medications prescribed to treat extrapyramidal symptoms (ie, diphenhydramine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl), anxiety, depression, and insomnia (ie, paroxetine, trazodone, doxepin) further add insult to injury because they impair sweating, which decreases the body’s ability to eliminate heat through evaporation.2,3 Additionally, high temperature exacerbates psychiatric symptoms in patients with SMI, resulting in increased hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

How to keep patients safe

The acronym HEAT provides a framework that psychiatrists can use to highlight the importance of planning for heat waves in their institution and guiding discussions with individual patients about heat-related illnesses (Table 1).

Help the health care system where you work plan and prepare for heat waves. In-service training in mental health settings such as outpatient clinics, shelters, group homes, and residential programs can help staff identify patients at particular risk and reinforce key prevention messages.

Educate patients and their caregivers on strategies for preventing heat-related illness. Informational materials can be distributed in clinics, residential settings, and day programs. A 1-page downloadable pamphlet available at https://smiadviser.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SMI-Heat-Stroke-ver1.0-FINAL.pdf summarizes key prevention messages of staying hydrated, staying cool, and staying safe.

Assess personalized heat-related risks. Inquire about patients’ daily activities, access to air conditioning, and water intake. Minimize the use of anticholinergic medications. Identify who patients can turn to for assistance, especially for those who struggle with cognitive impairment and social isolation.

Teach patients, caregivers, and staff the signs and symptoms of heat exhaustion and heat stroke and how to respond in such situations.

HEAT focuses psychiatric clinicians on preparing and protecting patients with SMI against dangerous heat waves. Clinicians can take a proactive leadership role in disseminating basic principles of heat-related illness prevention and heat-wave toolkits by using resources available from organizations such as the Climate Psychiatry Alliance (Table 2). They can also initiate advocacy efforts to raise awareness about the elevated risks of heat-related illnesses in this vulnerable population.

Climate change is causing intense heat waves that threaten human health across the globe.

A confluence of factors increases risk

Thermoregulatory dysfunction is thought to be intrinsic to patients with schizophrenia partly due to dysregulated dopaminergic neurotransmission.2 This is compounded by these patients’ higher burden of chronic medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, which together with psychotropic (ie, antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines) and medical medications (ie, certain antihypertensives, diuretics, treatment for urinary incontinence) further disrupt the body’s cooling strategies and increase vulnerability to heat-related illnesses.1,3 Antipsychotics commonly prescribed to patients with SMI increase hyperthermia risk largely by 2 mechanisms: central and peripheral thermal dysregulation, and anticholinergic properties (ie, olanzapine, clozapine, chlorpromazine).2,3 Other anticholinergic medications prescribed to treat extrapyramidal symptoms (ie, diphenhydramine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl), anxiety, depression, and insomnia (ie, paroxetine, trazodone, doxepin) further add insult to injury because they impair sweating, which decreases the body’s ability to eliminate heat through evaporation.2,3 Additionally, high temperature exacerbates psychiatric symptoms in patients with SMI, resulting in increased hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

How to keep patients safe

The acronym HEAT provides a framework that psychiatrists can use to highlight the importance of planning for heat waves in their institution and guiding discussions with individual patients about heat-related illnesses (Table 1).

Help the health care system where you work plan and prepare for heat waves. In-service training in mental health settings such as outpatient clinics, shelters, group homes, and residential programs can help staff identify patients at particular risk and reinforce key prevention messages.

Educate patients and their caregivers on strategies for preventing heat-related illness. Informational materials can be distributed in clinics, residential settings, and day programs. A 1-page downloadable pamphlet available at https://smiadviser.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SMI-Heat-Stroke-ver1.0-FINAL.pdf summarizes key prevention messages of staying hydrated, staying cool, and staying safe.

Assess personalized heat-related risks. Inquire about patients’ daily activities, access to air conditioning, and water intake. Minimize the use of anticholinergic medications. Identify who patients can turn to for assistance, especially for those who struggle with cognitive impairment and social isolation.

Teach patients, caregivers, and staff the signs and symptoms of heat exhaustion and heat stroke and how to respond in such situations.

HEAT focuses psychiatric clinicians on preparing and protecting patients with SMI against dangerous heat waves. Clinicians can take a proactive leadership role in disseminating basic principles of heat-related illness prevention and heat-wave toolkits by using resources available from organizations such as the Climate Psychiatry Alliance (Table 2). They can also initiate advocacy efforts to raise awareness about the elevated risks of heat-related illnesses in this vulnerable population.

1. Schmeltz MT, Gamble JL. Risk characterization of hospitalizations for mental illness and/or behavioral disorders with concurrent heat-related illness. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186509. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186509

2. Lee CP, Chen PJ, Chang CM. Heat stroke during treatment with olanzapine, trihexyphenidyl, and trazodone in a patient with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2015;27(6):380-385.

3. Bongers KS, Salahudeen MS, Peterson GM. Drug-associated non-pyrogenic hyperthermia: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(1):9-16.

1. Schmeltz MT, Gamble JL. Risk characterization of hospitalizations for mental illness and/or behavioral disorders with concurrent heat-related illness. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186509. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186509

2. Lee CP, Chen PJ, Chang CM. Heat stroke during treatment with olanzapine, trihexyphenidyl, and trazodone in a patient with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2015;27(6):380-385.

3. Bongers KS, Salahudeen MS, Peterson GM. Drug-associated non-pyrogenic hyperthermia: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(1):9-16.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics during COVID-19

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are an essential tool in the treatment of patients with psychotic disorders, allowing for periods of stable drug plasma concentration and confirmed adherence.1 The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic presents unique challenges for administering LAIs and requires a thoughtful and prospective approach in order to ensure continuity of psychiatric care while minimizing the risk of infection with COVID-19. Ideally, patients should be seen in person as infrequently as clinically prudent during this public health emergency; however, LAI administration necessitates direct physical contact between patient and clinician.

Patients with serious mental illness (SMI), who comprise the majority of individuals who receive LAIs, are at heightened risk for cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities. These factors are the primary reason the life expectancy of a patient with SMI is nearly 30 years shorter than that of the general population.2-5 The risk of health care workers becoming infected or inadvertently spreading COVID-19 is heightened when working with patients in group living environments (ie, a shelter or group home), who have both increased exposure and increased risk of further transmission.6 Additional patient populations, including older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with preexisting conditions, are at heightened risk for serious complications if they were to contract COVID-19.7,8

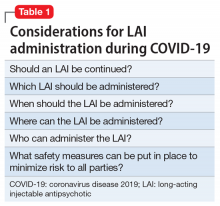

Thus, the questions of whether LAIs should be administered, and how to do so safely (both during the ongoing, acute phase of the pandemic as well as during the subsequent recovery period until the pandemic abates) need to be carefully considered. In this article, we provide concrete advice for clinicians and clinics on these topics, with the goal of maintaining patients’ psychiatric stability while protecting patients, health care workers, and the broader society from COVID-19 infection. Table 1 summarizes the questions regarding LAIs that clinicians need to address during this crisis. While we focus on outpatient care, inpatient teams should keep these considerations in mind if they are starting and discharging a patient on an LAI. More than ever, close collaboration and communication between inpatient and outpatient teams is critical.

Should an LAI be continued?

An important first step to approaching this challenge is to create a spreadsheet for all patients receiving LAIs. Focusing on a population-based approach is helpful to be systematic and ensure that no patients fall through the cracks during this public health emergency.9 Once all patients have been identified, the treatment team should review each patient to determine if continuing to administer the antipsychotic as an LAI formulation is essential, taking into account the patient’s current psychiatric status, historical medication adherence, potential severity and dangerousness of decompensation if nonadherent, and structures to support stability. For example, can a patient move in with family who can monitor medication adherence during the pandemic? Is it possible for the group home to assume medication administration? Additional consideration should be given to the living environment and health-vulnerability of the patient and the individuals living with them.

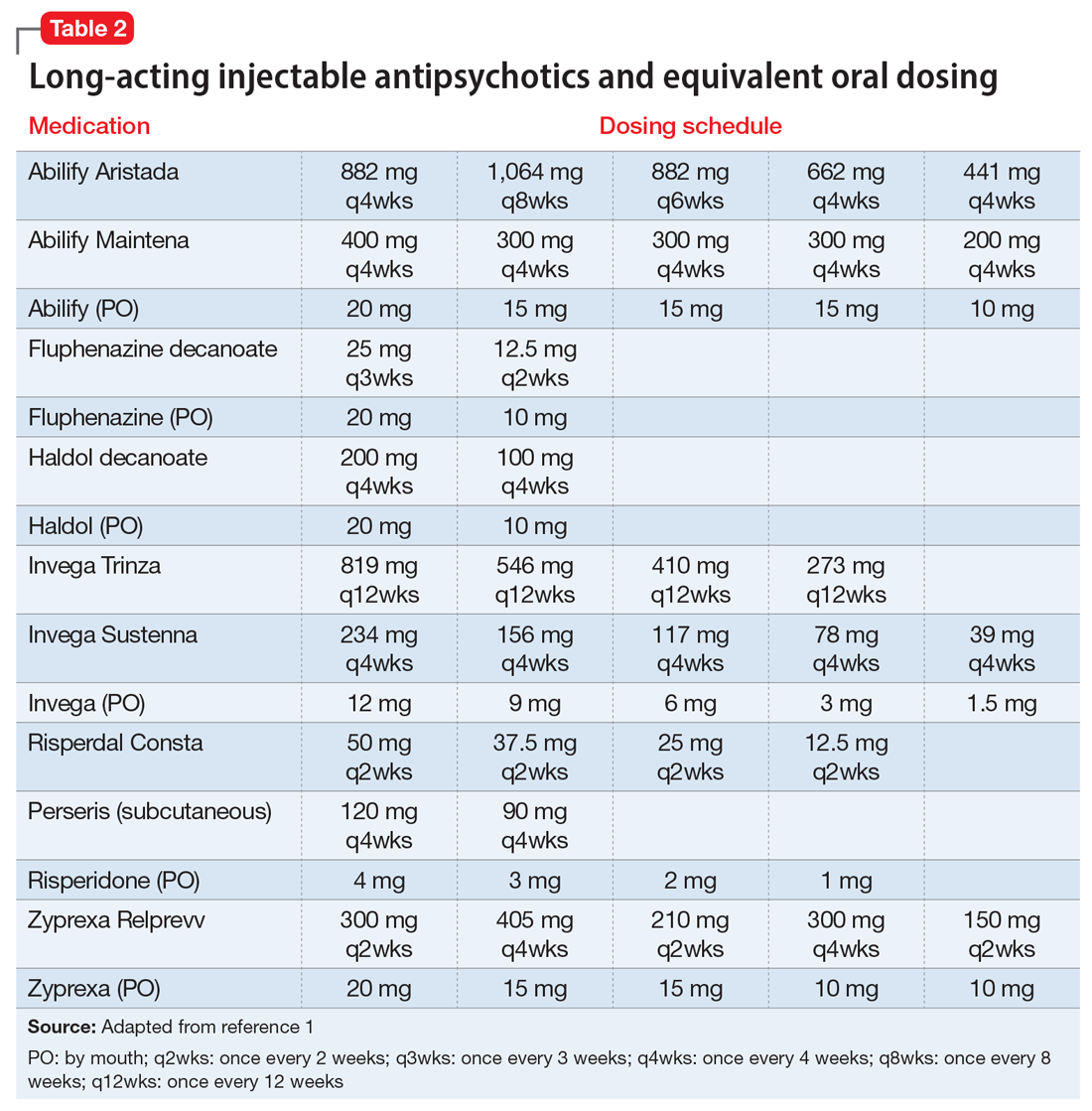

If the risk calculation does not point strongly towards a need for continuing the LAI, it may be prudent to temporarily transition the patient to the corresponding oral antipsychotic preparation. Table 2 lists all LAIs available in the United States and their approximate equivalent oral dosing. It is important to note that such transitions are not without clinical risk, to emphasize to the patient that the transition is intended as a temporary measure, and to discuss a proposed timeline for re-initiating the LAI. Also, emphasize to the patient and family that this transition does not diminish the previous reasoning for needing an LAI, but is a temporary measure taken in light of weighing the risks and benefits during a pandemic.

Which LAI should be administered?

If continuing the LAI is determined to be clinically necessary, consider switching the patient to a longer-acting preparation to maximize intervals between administrations and minimize the potential for infection. From a public health perspective, the longest clinically prudent interval between injections may be the most important consideration, provided the patient can receive a dose necessary to retain stability, and the LAI should be chosen accordingly. Deltoid injections may be able to be administered with reduced contact, or on a “drive-up” basis.10 Consider transitioning a patient who is receiving olanzapine pamoate to an alternate LAI or oral formulation, because the 3-hour observation period that is required after olanzapine pamoate administration is particularly problematic. While it may not be ideal to make medication changes during a pandemic, it is worth carefully weighing the patient’s stability and historical experience with other LAIs to determine if a safer/longer-spaced option is worth trying.11

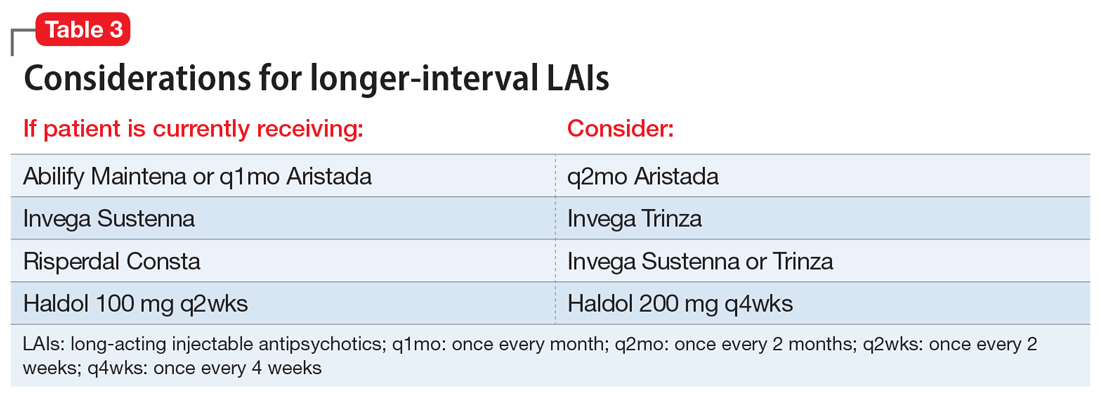

We recommend only switching among similar antipsychotics (ie, risperidone to paliperidone), or between different preparations of the same drug (ie, Abilify Maintena to Aristada), if possible, as these are the lowest risk transitions with regards to relapse. Table 3 provides examples.

Continue to: When should the LAI be administered?

When should the LAI be administered?

The pharmacokinetics of LAIs allow for some flexibility in terms of when an LAI needs to be administered. The package inserts of all second-generation LAIs include missed-dose guidelines. These guidelines provide information on how long one can wait before the next injection is due, and what additional measures must be taken when beyond that date. Delaying an injection may be prudent, and the missed dose guidelines will indicate when one must consider supplementing with oral medications. For patients who are in quarantine, it may be better to delay an injection until the patient ends their quarantine than to deliver the dose during quarantine. Administering an injection earlier also is usually safe; off-cycle visits may help minimize patient contact (ie, if the patient happens to be coming into the vicinity of the clinic, or requires phlebotomy for therapeutic drug monitoring), and assist in planning for possible resurgences. When appropriate, and after considering the risk of worsening adverse effects, administering a higher dose than the usual maintenance dose would provide a buffer if the next injection was to be delayed. Therapeutic drug monitoring can help to optimize dosing and avoid low plasma drug levels, which may be not be sufficient, particularly during this time of stress.12 To provide optimal protection against relapse, consider administering a dose that puts patients at the higher range of plasma drug levels.

Where can the LAI be administered, and who can give it?

For patients who usually travel to a clinic, consider arranging for a more local injection (ie, at the patient’s primary care clinic in their hometown, or at a local mental health center), and explore if the patient may be able to receive their injection in their home through a visiting nurse association (VNA). In many states (approximately 30 currently), clinicians at pharmacies are also able to administer patient injections. Clinics would do well to at least plan for alternate staffing models in the event of staff illness. A pool of individuals should be available to give injections; consider training additional staff members (including MDs who may have never previously administered an LAI but could be quickly instructed to do so) to administer LAIs. Theoretically, during a public health emergency, family members, particularly those who have a background in health care, could be trained to give an injection and provided education on LAI storage and post-injection monitoring. This approach would not be consistent with FDA labeling, however, and should only be considered as a last resort.

What safety measures can be put in place?

Face-to-face time for injection administration should be kept as brief as possible. Before the encounter, obtain the patient’s clinical information, ideally through telehealth or from an acceptable distance. Medication should be drawn ahead of time, and not in an enclosed space with the patient present. Strongly consider abandoning the traditional enclosed room for the injection, and instead use larger spaces, doorways, or outside, if feasible. As previously noted, some clinics and clinicians have used a drive-up approach for LAI administration, particularly for deltoid injections.10 Individuals who administer the injections should wear personal protective equipment, and the clinic should obtain an adequate supply of this equipment well in advance.

Lessons learned at our clinic

In our community mental health center clinic, planning around these questions has allowed us to provide safe and continuous psychiatric care with LAIs during this public health emergency while reducing the risk of infection. We have worked to transfer LAI administration to VNAs and transition patients to longer-lasting formulations or oral medications where appropriate, which has resulted in an approximately 50% decrease in in-person visits. Reducing the number of in-person visits does not need to result in less frequent clinical follow-up. Telepsychiatry visits can make up for lost in-person visits and have generally been well accepted.

As we are preparing for the next phase, routine medical health monitoring (eg, metabolic monitoring, monitoring for tardive dyskinesia) that has not been at the forefront of concerns should be carefully reintroduced. Challenges encountered have included difficulty in having VNA accept patients for short-term LAI visits, changes to where on the body the injection is delivered, and patients with SMI and their families being reluctant to depart from previous routines and administration schedules.

Continue to: There is great value...

There is great value in the collective lessons learned during this public health emergency (eg, the need for a flexible, population health-based approach; acceptability of combination telehealth and in-person visits) that can lead to more person-centered and accessible care for patients with SMI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank North Suffolk Mental Health Association, the Freedom Trail Clinic, and their patients.

Bottom Line

When caring for a patient with a psychotic illness during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, evaluate whether it is necessary to continue a longacting injectable antipsychotic (LAI). If yes, reconsider which LAI should be administered, when and where it should be given, and by whom. Implement safety measures to minimize the risk of COVID-19 exposure and transmission.

Related Resources

- American Association of Community Psychiatrists. Clinical Tip Series. Long acting antipsychotic medications. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1unigjmjFJkqZMbaZ_ftdj8oqog49awZs/view?usp=sharing

- SMI Adviser. What are clinical considerations for giving LAIs during the COVID-19 public health emergency? https://smiadviser.org/knowledge_post/what-are-clinical-considerations-for-giving-lais-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency

- CDC. Infection control basics. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/index.html

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole for extended- release injectable suspension • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Haloperidol • Haldol

Haloperidol injection • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine for extended-release injectable suspension • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Trinza

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone for extended- release injectable suspension • Perseris

Risperidone injection • Risperdal Consta

1. Freudenreich O. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics. In: Freudenreich O. Psychotic disorders: a practical guide. Springer; 2020:249-261.

2. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

3. Reilly S, Olier I, Planner C, et al. Inequalities in physical comorbidity: a longitudinal comparative cohort study of people with severe mental illness in the UK. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009010.

4. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212-217.

5. Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al. Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(2):183-194.

6. Baggett TP, Keyes H, Sporn N, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of a large homeless shelter in Boston. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2191-2192.

7. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343-346.

8. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985

9. Etches V, Frank J, Di Ruggiero E, et al. Measuring population health: a review of indicators. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:29-55.

10. Chepke C. Drive-up pharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):29-30.

11. Sajatovic M, Ross R, Legacy SN, et al. Initiating/maintaining long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder - expert consensus survey part 2. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1475-1492.

12. Schoretsanitis G, Kane JM, Correll CU, et al; American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Pharmakopsychiatrie TTDMTFOTAFNU. Blood levels to optimize antipsychotic treatment in clinical practice: a joint consensus statement of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology and the Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Task Force of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Neuropsychopharmakologie und Pharmakopsychiatrie. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):19cs13169. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19cs13169

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are an essential tool in the treatment of patients with psychotic disorders, allowing for periods of stable drug plasma concentration and confirmed adherence.1 The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic presents unique challenges for administering LAIs and requires a thoughtful and prospective approach in order to ensure continuity of psychiatric care while minimizing the risk of infection with COVID-19. Ideally, patients should be seen in person as infrequently as clinically prudent during this public health emergency; however, LAI administration necessitates direct physical contact between patient and clinician.

Patients with serious mental illness (SMI), who comprise the majority of individuals who receive LAIs, are at heightened risk for cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities. These factors are the primary reason the life expectancy of a patient with SMI is nearly 30 years shorter than that of the general population.2-5 The risk of health care workers becoming infected or inadvertently spreading COVID-19 is heightened when working with patients in group living environments (ie, a shelter or group home), who have both increased exposure and increased risk of further transmission.6 Additional patient populations, including older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with preexisting conditions, are at heightened risk for serious complications if they were to contract COVID-19.7,8

Thus, the questions of whether LAIs should be administered, and how to do so safely (both during the ongoing, acute phase of the pandemic as well as during the subsequent recovery period until the pandemic abates) need to be carefully considered. In this article, we provide concrete advice for clinicians and clinics on these topics, with the goal of maintaining patients’ psychiatric stability while protecting patients, health care workers, and the broader society from COVID-19 infection. Table 1 summarizes the questions regarding LAIs that clinicians need to address during this crisis. While we focus on outpatient care, inpatient teams should keep these considerations in mind if they are starting and discharging a patient on an LAI. More than ever, close collaboration and communication between inpatient and outpatient teams is critical.

Should an LAI be continued?

An important first step to approaching this challenge is to create a spreadsheet for all patients receiving LAIs. Focusing on a population-based approach is helpful to be systematic and ensure that no patients fall through the cracks during this public health emergency.9 Once all patients have been identified, the treatment team should review each patient to determine if continuing to administer the antipsychotic as an LAI formulation is essential, taking into account the patient’s current psychiatric status, historical medication adherence, potential severity and dangerousness of decompensation if nonadherent, and structures to support stability. For example, can a patient move in with family who can monitor medication adherence during the pandemic? Is it possible for the group home to assume medication administration? Additional consideration should be given to the living environment and health-vulnerability of the patient and the individuals living with them.

If the risk calculation does not point strongly towards a need for continuing the LAI, it may be prudent to temporarily transition the patient to the corresponding oral antipsychotic preparation. Table 2 lists all LAIs available in the United States and their approximate equivalent oral dosing. It is important to note that such transitions are not without clinical risk, to emphasize to the patient that the transition is intended as a temporary measure, and to discuss a proposed timeline for re-initiating the LAI. Also, emphasize to the patient and family that this transition does not diminish the previous reasoning for needing an LAI, but is a temporary measure taken in light of weighing the risks and benefits during a pandemic.

Which LAI should be administered?

If continuing the LAI is determined to be clinically necessary, consider switching the patient to a longer-acting preparation to maximize intervals between administrations and minimize the potential for infection. From a public health perspective, the longest clinically prudent interval between injections may be the most important consideration, provided the patient can receive a dose necessary to retain stability, and the LAI should be chosen accordingly. Deltoid injections may be able to be administered with reduced contact, or on a “drive-up” basis.10 Consider transitioning a patient who is receiving olanzapine pamoate to an alternate LAI or oral formulation, because the 3-hour observation period that is required after olanzapine pamoate administration is particularly problematic. While it may not be ideal to make medication changes during a pandemic, it is worth carefully weighing the patient’s stability and historical experience with other LAIs to determine if a safer/longer-spaced option is worth trying.11

We recommend only switching among similar antipsychotics (ie, risperidone to paliperidone), or between different preparations of the same drug (ie, Abilify Maintena to Aristada), if possible, as these are the lowest risk transitions with regards to relapse. Table 3 provides examples.

Continue to: When should the LAI be administered?

When should the LAI be administered?

The pharmacokinetics of LAIs allow for some flexibility in terms of when an LAI needs to be administered. The package inserts of all second-generation LAIs include missed-dose guidelines. These guidelines provide information on how long one can wait before the next injection is due, and what additional measures must be taken when beyond that date. Delaying an injection may be prudent, and the missed dose guidelines will indicate when one must consider supplementing with oral medications. For patients who are in quarantine, it may be better to delay an injection until the patient ends their quarantine than to deliver the dose during quarantine. Administering an injection earlier also is usually safe; off-cycle visits may help minimize patient contact (ie, if the patient happens to be coming into the vicinity of the clinic, or requires phlebotomy for therapeutic drug monitoring), and assist in planning for possible resurgences. When appropriate, and after considering the risk of worsening adverse effects, administering a higher dose than the usual maintenance dose would provide a buffer if the next injection was to be delayed. Therapeutic drug monitoring can help to optimize dosing and avoid low plasma drug levels, which may be not be sufficient, particularly during this time of stress.12 To provide optimal protection against relapse, consider administering a dose that puts patients at the higher range of plasma drug levels.

Where can the LAI be administered, and who can give it?

For patients who usually travel to a clinic, consider arranging for a more local injection (ie, at the patient’s primary care clinic in their hometown, or at a local mental health center), and explore if the patient may be able to receive their injection in their home through a visiting nurse association (VNA). In many states (approximately 30 currently), clinicians at pharmacies are also able to administer patient injections. Clinics would do well to at least plan for alternate staffing models in the event of staff illness. A pool of individuals should be available to give injections; consider training additional staff members (including MDs who may have never previously administered an LAI but could be quickly instructed to do so) to administer LAIs. Theoretically, during a public health emergency, family members, particularly those who have a background in health care, could be trained to give an injection and provided education on LAI storage and post-injection monitoring. This approach would not be consistent with FDA labeling, however, and should only be considered as a last resort.

What safety measures can be put in place?

Face-to-face time for injection administration should be kept as brief as possible. Before the encounter, obtain the patient’s clinical information, ideally through telehealth or from an acceptable distance. Medication should be drawn ahead of time, and not in an enclosed space with the patient present. Strongly consider abandoning the traditional enclosed room for the injection, and instead use larger spaces, doorways, or outside, if feasible. As previously noted, some clinics and clinicians have used a drive-up approach for LAI administration, particularly for deltoid injections.10 Individuals who administer the injections should wear personal protective equipment, and the clinic should obtain an adequate supply of this equipment well in advance.

Lessons learned at our clinic

In our community mental health center clinic, planning around these questions has allowed us to provide safe and continuous psychiatric care with LAIs during this public health emergency while reducing the risk of infection. We have worked to transfer LAI administration to VNAs and transition patients to longer-lasting formulations or oral medications where appropriate, which has resulted in an approximately 50% decrease in in-person visits. Reducing the number of in-person visits does not need to result in less frequent clinical follow-up. Telepsychiatry visits can make up for lost in-person visits and have generally been well accepted.

As we are preparing for the next phase, routine medical health monitoring (eg, metabolic monitoring, monitoring for tardive dyskinesia) that has not been at the forefront of concerns should be carefully reintroduced. Challenges encountered have included difficulty in having VNA accept patients for short-term LAI visits, changes to where on the body the injection is delivered, and patients with SMI and their families being reluctant to depart from previous routines and administration schedules.

Continue to: There is great value...

There is great value in the collective lessons learned during this public health emergency (eg, the need for a flexible, population health-based approach; acceptability of combination telehealth and in-person visits) that can lead to more person-centered and accessible care for patients with SMI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank North Suffolk Mental Health Association, the Freedom Trail Clinic, and their patients.

Bottom Line

When caring for a patient with a psychotic illness during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, evaluate whether it is necessary to continue a longacting injectable antipsychotic (LAI). If yes, reconsider which LAI should be administered, when and where it should be given, and by whom. Implement safety measures to minimize the risk of COVID-19 exposure and transmission.

Related Resources

- American Association of Community Psychiatrists. Clinical Tip Series. Long acting antipsychotic medications. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1unigjmjFJkqZMbaZ_ftdj8oqog49awZs/view?usp=sharing

- SMI Adviser. What are clinical considerations for giving LAIs during the COVID-19 public health emergency? https://smiadviser.org/knowledge_post/what-are-clinical-considerations-for-giving-lais-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency

- CDC. Infection control basics. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/index.html

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole for extended- release injectable suspension • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Haloperidol • Haldol

Haloperidol injection • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine for extended-release injectable suspension • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Trinza

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone for extended- release injectable suspension • Perseris

Risperidone injection • Risperdal Consta

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are an essential tool in the treatment of patients with psychotic disorders, allowing for periods of stable drug plasma concentration and confirmed adherence.1 The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic presents unique challenges for administering LAIs and requires a thoughtful and prospective approach in order to ensure continuity of psychiatric care while minimizing the risk of infection with COVID-19. Ideally, patients should be seen in person as infrequently as clinically prudent during this public health emergency; however, LAI administration necessitates direct physical contact between patient and clinician.

Patients with serious mental illness (SMI), who comprise the majority of individuals who receive LAIs, are at heightened risk for cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities. These factors are the primary reason the life expectancy of a patient with SMI is nearly 30 years shorter than that of the general population.2-5 The risk of health care workers becoming infected or inadvertently spreading COVID-19 is heightened when working with patients in group living environments (ie, a shelter or group home), who have both increased exposure and increased risk of further transmission.6 Additional patient populations, including older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with preexisting conditions, are at heightened risk for serious complications if they were to contract COVID-19.7,8

Thus, the questions of whether LAIs should be administered, and how to do so safely (both during the ongoing, acute phase of the pandemic as well as during the subsequent recovery period until the pandemic abates) need to be carefully considered. In this article, we provide concrete advice for clinicians and clinics on these topics, with the goal of maintaining patients’ psychiatric stability while protecting patients, health care workers, and the broader society from COVID-19 infection. Table 1 summarizes the questions regarding LAIs that clinicians need to address during this crisis. While we focus on outpatient care, inpatient teams should keep these considerations in mind if they are starting and discharging a patient on an LAI. More than ever, close collaboration and communication between inpatient and outpatient teams is critical.

Should an LAI be continued?

An important first step to approaching this challenge is to create a spreadsheet for all patients receiving LAIs. Focusing on a population-based approach is helpful to be systematic and ensure that no patients fall through the cracks during this public health emergency.9 Once all patients have been identified, the treatment team should review each patient to determine if continuing to administer the antipsychotic as an LAI formulation is essential, taking into account the patient’s current psychiatric status, historical medication adherence, potential severity and dangerousness of decompensation if nonadherent, and structures to support stability. For example, can a patient move in with family who can monitor medication adherence during the pandemic? Is it possible for the group home to assume medication administration? Additional consideration should be given to the living environment and health-vulnerability of the patient and the individuals living with them.

If the risk calculation does not point strongly towards a need for continuing the LAI, it may be prudent to temporarily transition the patient to the corresponding oral antipsychotic preparation. Table 2 lists all LAIs available in the United States and their approximate equivalent oral dosing. It is important to note that such transitions are not without clinical risk, to emphasize to the patient that the transition is intended as a temporary measure, and to discuss a proposed timeline for re-initiating the LAI. Also, emphasize to the patient and family that this transition does not diminish the previous reasoning for needing an LAI, but is a temporary measure taken in light of weighing the risks and benefits during a pandemic.

Which LAI should be administered?

If continuing the LAI is determined to be clinically necessary, consider switching the patient to a longer-acting preparation to maximize intervals between administrations and minimize the potential for infection. From a public health perspective, the longest clinically prudent interval between injections may be the most important consideration, provided the patient can receive a dose necessary to retain stability, and the LAI should be chosen accordingly. Deltoid injections may be able to be administered with reduced contact, or on a “drive-up” basis.10 Consider transitioning a patient who is receiving olanzapine pamoate to an alternate LAI or oral formulation, because the 3-hour observation period that is required after olanzapine pamoate administration is particularly problematic. While it may not be ideal to make medication changes during a pandemic, it is worth carefully weighing the patient’s stability and historical experience with other LAIs to determine if a safer/longer-spaced option is worth trying.11

We recommend only switching among similar antipsychotics (ie, risperidone to paliperidone), or between different preparations of the same drug (ie, Abilify Maintena to Aristada), if possible, as these are the lowest risk transitions with regards to relapse. Table 3 provides examples.

Continue to: When should the LAI be administered?

When should the LAI be administered?

The pharmacokinetics of LAIs allow for some flexibility in terms of when an LAI needs to be administered. The package inserts of all second-generation LAIs include missed-dose guidelines. These guidelines provide information on how long one can wait before the next injection is due, and what additional measures must be taken when beyond that date. Delaying an injection may be prudent, and the missed dose guidelines will indicate when one must consider supplementing with oral medications. For patients who are in quarantine, it may be better to delay an injection until the patient ends their quarantine than to deliver the dose during quarantine. Administering an injection earlier also is usually safe; off-cycle visits may help minimize patient contact (ie, if the patient happens to be coming into the vicinity of the clinic, or requires phlebotomy for therapeutic drug monitoring), and assist in planning for possible resurgences. When appropriate, and after considering the risk of worsening adverse effects, administering a higher dose than the usual maintenance dose would provide a buffer if the next injection was to be delayed. Therapeutic drug monitoring can help to optimize dosing and avoid low plasma drug levels, which may be not be sufficient, particularly during this time of stress.12 To provide optimal protection against relapse, consider administering a dose that puts patients at the higher range of plasma drug levels.

Where can the LAI be administered, and who can give it?

For patients who usually travel to a clinic, consider arranging for a more local injection (ie, at the patient’s primary care clinic in their hometown, or at a local mental health center), and explore if the patient may be able to receive their injection in their home through a visiting nurse association (VNA). In many states (approximately 30 currently), clinicians at pharmacies are also able to administer patient injections. Clinics would do well to at least plan for alternate staffing models in the event of staff illness. A pool of individuals should be available to give injections; consider training additional staff members (including MDs who may have never previously administered an LAI but could be quickly instructed to do so) to administer LAIs. Theoretically, during a public health emergency, family members, particularly those who have a background in health care, could be trained to give an injection and provided education on LAI storage and post-injection monitoring. This approach would not be consistent with FDA labeling, however, and should only be considered as a last resort.

What safety measures can be put in place?

Face-to-face time for injection administration should be kept as brief as possible. Before the encounter, obtain the patient’s clinical information, ideally through telehealth or from an acceptable distance. Medication should be drawn ahead of time, and not in an enclosed space with the patient present. Strongly consider abandoning the traditional enclosed room for the injection, and instead use larger spaces, doorways, or outside, if feasible. As previously noted, some clinics and clinicians have used a drive-up approach for LAI administration, particularly for deltoid injections.10 Individuals who administer the injections should wear personal protective equipment, and the clinic should obtain an adequate supply of this equipment well in advance.

Lessons learned at our clinic

In our community mental health center clinic, planning around these questions has allowed us to provide safe and continuous psychiatric care with LAIs during this public health emergency while reducing the risk of infection. We have worked to transfer LAI administration to VNAs and transition patients to longer-lasting formulations or oral medications where appropriate, which has resulted in an approximately 50% decrease in in-person visits. Reducing the number of in-person visits does not need to result in less frequent clinical follow-up. Telepsychiatry visits can make up for lost in-person visits and have generally been well accepted.

As we are preparing for the next phase, routine medical health monitoring (eg, metabolic monitoring, monitoring for tardive dyskinesia) that has not been at the forefront of concerns should be carefully reintroduced. Challenges encountered have included difficulty in having VNA accept patients for short-term LAI visits, changes to where on the body the injection is delivered, and patients with SMI and their families being reluctant to depart from previous routines and administration schedules.

Continue to: There is great value...

There is great value in the collective lessons learned during this public health emergency (eg, the need for a flexible, population health-based approach; acceptability of combination telehealth and in-person visits) that can lead to more person-centered and accessible care for patients with SMI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank North Suffolk Mental Health Association, the Freedom Trail Clinic, and their patients.

Bottom Line

When caring for a patient with a psychotic illness during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, evaluate whether it is necessary to continue a longacting injectable antipsychotic (LAI). If yes, reconsider which LAI should be administered, when and where it should be given, and by whom. Implement safety measures to minimize the risk of COVID-19 exposure and transmission.

Related Resources

- American Association of Community Psychiatrists. Clinical Tip Series. Long acting antipsychotic medications. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1unigjmjFJkqZMbaZ_ftdj8oqog49awZs/view?usp=sharing

- SMI Adviser. What are clinical considerations for giving LAIs during the COVID-19 public health emergency? https://smiadviser.org/knowledge_post/what-are-clinical-considerations-for-giving-lais-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency

- CDC. Infection control basics. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/index.html

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole for extended- release injectable suspension • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Haloperidol • Haldol

Haloperidol injection • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine for extended-release injectable suspension • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Trinza

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone for extended- release injectable suspension • Perseris

Risperidone injection • Risperdal Consta

1. Freudenreich O. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics. In: Freudenreich O. Psychotic disorders: a practical guide. Springer; 2020:249-261.

2. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

3. Reilly S, Olier I, Planner C, et al. Inequalities in physical comorbidity: a longitudinal comparative cohort study of people with severe mental illness in the UK. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009010.

4. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212-217.

5. Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al. Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(2):183-194.

6. Baggett TP, Keyes H, Sporn N, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of a large homeless shelter in Boston. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2191-2192.

7. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343-346.

8. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985

9. Etches V, Frank J, Di Ruggiero E, et al. Measuring population health: a review of indicators. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:29-55.

10. Chepke C. Drive-up pharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):29-30.

11. Sajatovic M, Ross R, Legacy SN, et al. Initiating/maintaining long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder - expert consensus survey part 2. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1475-1492.

12. Schoretsanitis G, Kane JM, Correll CU, et al; American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Pharmakopsychiatrie TTDMTFOTAFNU. Blood levels to optimize antipsychotic treatment in clinical practice: a joint consensus statement of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology and the Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Task Force of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Neuropsychopharmakologie und Pharmakopsychiatrie. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):19cs13169. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19cs13169

1. Freudenreich O. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics. In: Freudenreich O. Psychotic disorders: a practical guide. Springer; 2020:249-261.

2. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

3. Reilly S, Olier I, Planner C, et al. Inequalities in physical comorbidity: a longitudinal comparative cohort study of people with severe mental illness in the UK. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009010.

4. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212-217.

5. Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al. Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(2):183-194.

6. Baggett TP, Keyes H, Sporn N, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of a large homeless shelter in Boston. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2191-2192.

7. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343-346.

8. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985

9. Etches V, Frank J, Di Ruggiero E, et al. Measuring population health: a review of indicators. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:29-55.

10. Chepke C. Drive-up pharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):29-30.

11. Sajatovic M, Ross R, Legacy SN, et al. Initiating/maintaining long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder - expert consensus survey part 2. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1475-1492.

12. Schoretsanitis G, Kane JM, Correll CU, et al; American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Pharmakopsychiatrie TTDMTFOTAFNU. Blood levels to optimize antipsychotic treatment in clinical practice: a joint consensus statement of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology and the Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Task Force of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Neuropsychopharmakologie und Pharmakopsychiatrie. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):19cs13169. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19cs13169