User login

Vaginal hysterectomy with basic instrumentation

In the United States, gynecologic surgeons remove approximately one uterus every minute of the year.1 That rate translates to more than 525,000 hysterectomies annually in this country alone. Yet, despite the widespread availability of information on the benefits of a vaginal approach to hysterectomy, the great majority of these operations—close to 50%—are still performed via an open abdominal approach.2

As I pointed out last month in my “Update on Vaginal Hysterectomy,” the vaginal approach not only is more cosmetically pleasing than laparoscopic and robot-assisted hysterectomy (not to mention open abdominal surgery) but also has a lower complication rate.3

As I also noted, one reason for the low rate of vaginal hysterectomy may be the assumption, on the part of many gynecologic surgeons, that the techniques and tools they learned to use during training are still the only options available today. That assumption is wrong.

In this article, I describe the technique for vaginal hysterectomy using basic instru mentation. This article is based on a master class in vaginal hysterectomy produced by the AAGL and co-sponsored by the Am erican College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. This master class offers continuing medical education credits and is avail able at http://www.aagl.org/vaghystwebinar.

For a look at innovative tools for this procedure, see my “Update on Vaginal Hysterectomy” in the September 2015 issue of this journal at obgmanagement.com.

Vaginal hysterectomy has few contraindications

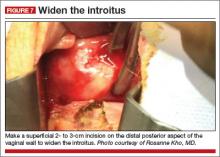

Many commonly cited contraindications to the vaginal approach are not, in fact, absolute contraindications. An open or laparoscopic approach is preferred when the patient has a known cancer, of course, and when deep infiltrating endometriosis is present at the rectovaginal septum. However, previous pelvic surgery, nulliparity, an enlarged uterus, or lack of a prior vaginal delivery need not exclude the vaginal approach. Nor does a narrow introitus necessarily mandate a laparoscopic or open abdominal approach. In fact, in this article, I describe my basic technique in a patient (a cadaver) with a very narrow pubic arch, and I offer strategies for gaining some needed mobility and avoiding complications (TABLES 1 and 2).

Next month, in the November issue of OBG Management, John B. Gebhart, MD, will describe his vaginal technique for right salpingectomy with ovarian preservation, as well as his technique for right salpingo-oophorectomy.

Proper patient positioning is key

You can simplify the operation by positioning the patient so that her buttocks are over the edge of the table fairly far—at least 1 inch beyond the edge of the table for optimal exposure and greater access. If the patient is thin, it then becomes important to pad the sacrum because, when she is positioned that far off the table, all her weight comes to rest on the sacrum. In overweight patients, this is not an issue, but for thin patients, I place a bit of egg crate or gel beneath the sacrum.

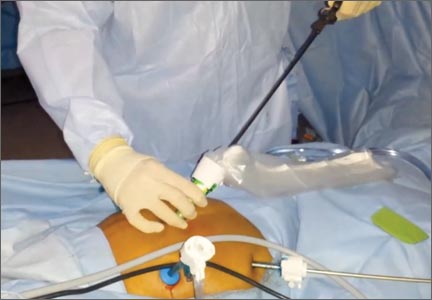

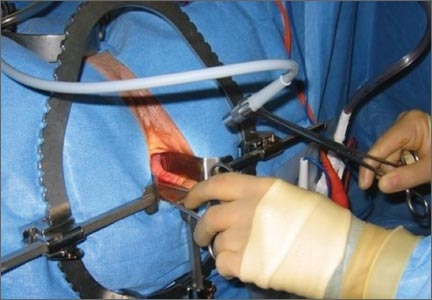

For the procedure, I prefer to place my instruments on a tray that is kept on my lap. This arrangement frees the scrub technician from having to hand tools over my shoulder—and it saves time. I use a narrow, covered Mayo stand, and I place a stepstool beneath my feet to keep my knees at right angles so that things don’t slip during the operation.

Surgical technique

Choose an appropriate retractor

In a woman with a narrow introitus, I find that a posterior weighted speculum takes up too much space. Once I place a clamp on the cervix with that speculum in place, I don’t have much room to work. However, if I substitute a small Deaver retractor, which is narrower, I gain more workspace.

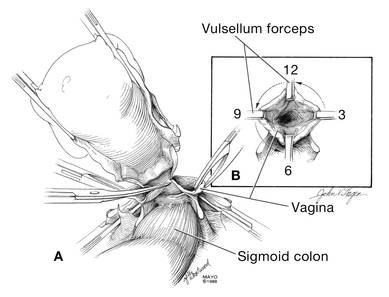

Inject the uterosacral ligaments

Grasp the cervix using a Jacobs vulsellum tenaculum. Use of a single tenaculum allows for much more movement than the use of instruments placed anteriorly and posteriorly. The Jacobs tenaculum obtains a better purchase on the tissue than a single tooth and is considerably less likely to tear through the tissue.

Before beginning the hysterectomy, locate the uterosacral ligaments and inject each one at its junction with the cervix, aspirating slightly before infiltrating the ligament with 0.25% to 0.50% bupivacaine with epinephrine, with dilute vasopressin mixed in. (I place 1 unit in 20 mL of the local solution.) Injection of this solution achieves 2 goals:

- improved intraoperative hemostasis

- postoperative pain relief.

Use a short needle with a needle extender attached to a control syringe rather than a spinal needle for greater control.

Enter the posterior peritoneal cavity

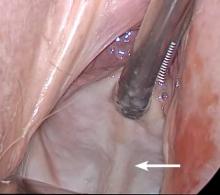

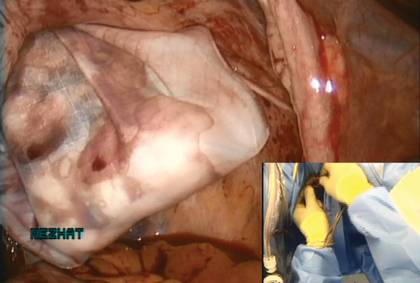

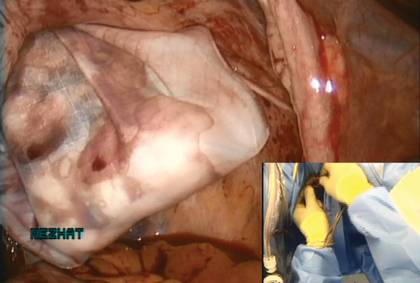

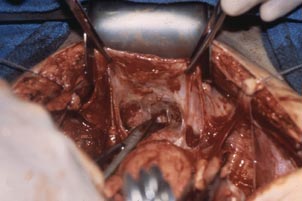

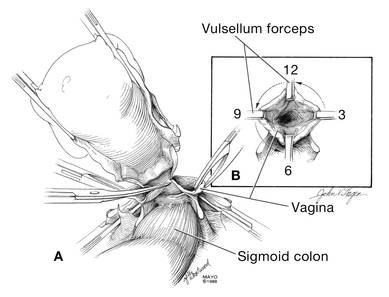

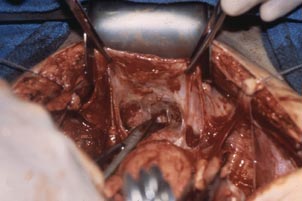

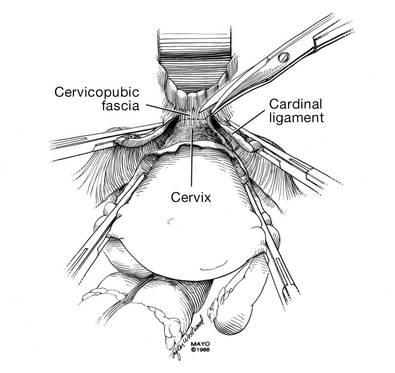

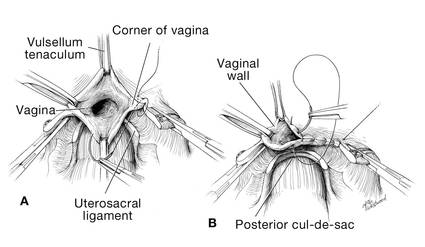

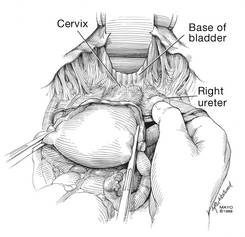

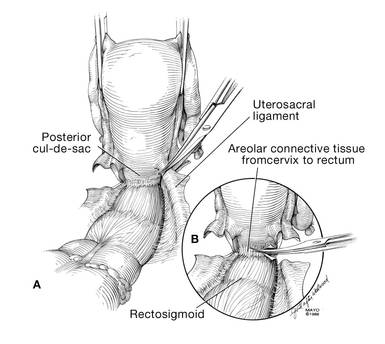

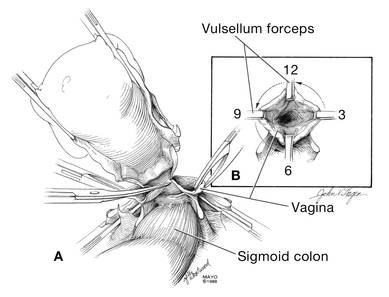

Before entering the peritoneal cavity, create a right angle with the Jacobs tenaculum and Deaver retractor in relation to the surgical field (FIGURE 1). This right angle is difficult to achieve when you are using a weighted speculum in a tight vagina. Once you have a right angle, tent the vaginal tissue in the midline (FIGURE 2).

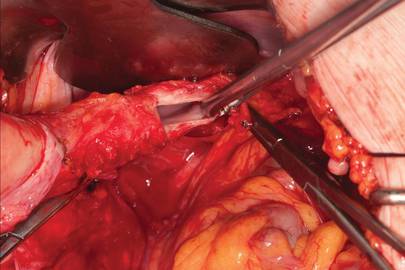

In a nulliparous patient or a woman with a tight pelvis, you may discover that the peritoneum is pulled up between the uterosacral ligaments. One common pitfall arises when the surgeon, having dissected the vaginal epithelium, continues cutting into the vaginal epithelium instead of reaching into the peritoneal cavity. Palpate the tissue to ensure that there is no bowel in the way and stay at right angles while confidently grasping the peritoneum with a toothed forceps.

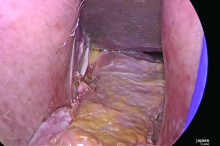

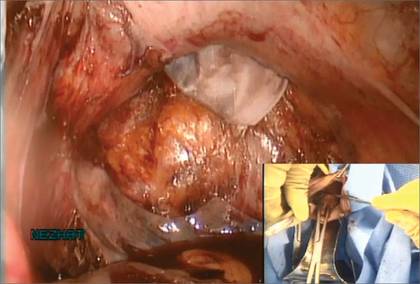

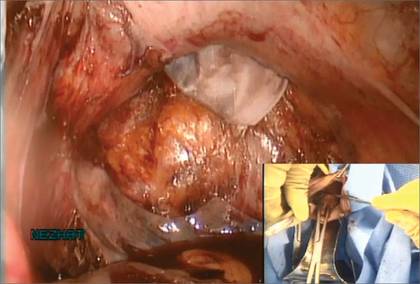

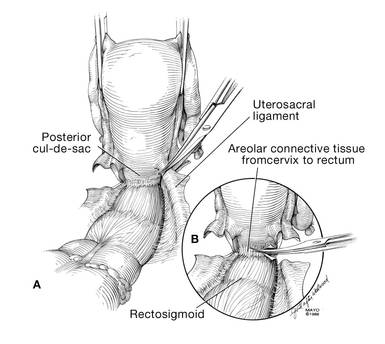

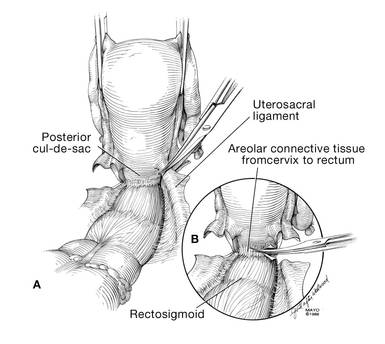

I like to use a bit of electrosurgery to incise the vaginal wall. I don’t begin at the cervix but incise more distally into the vaginal epithelium approximately 2 cm from the cervicovaginal junction. This strategy prevents dissection into the cervix and/or rectovaginal septum rather than the posterior

cul-de-sac (FIGURE 3).

Once the incision is made, it is possible to feel the posterior peritoneum. And as you tent the peritoneum, you can then very confidently extend the incision and enter the cavity posteriorly.

In a patient with significant adhesions such as this one, I feel around posteriorly to determine exactly where I am. One tactic I use is to release the tenaculum and regrasp the cervix with it. This allows for improved visualization and movement of the cervix as the procedure progresses. Depending on the case, it may be necessary to insert a sponge to hold bowel out of the way.

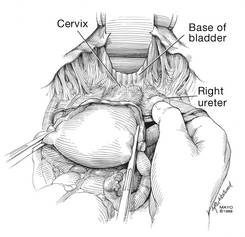

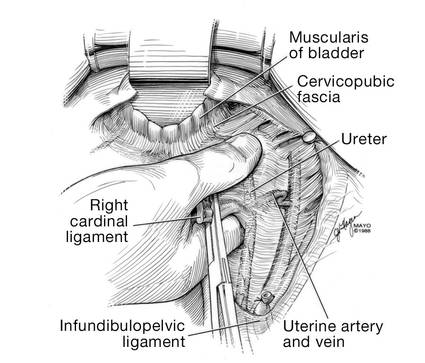

Avoid the bladder

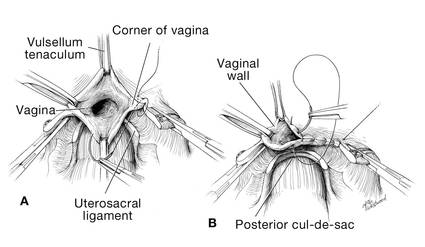

Move the Deaver retractor to the anterior position, switch the Jacobs clamp to the anterior cervix, and pull straight down. Now that you have incised the vaginal epithelium posteriorly, the length of the cervix should be apparent to you, and you can easily determine the location of the bladder reflection.

Keep in mind that, in a postmenopausal patient, there will be fewer vaginal rugae to guide you. Place the Jacobs tenaculum as close to the midline as possible so that you can confidently grab the tissue without fear of grabbing the bladder. If you tilt the Jacobs clamp, you can feel the edge of the bladder reflection. Remember that postmenopausal patients with prolapse (or, occasionally, obese patients with cervical elongation but little actual descensus) may have altered anatomy.

You can create a bit more space in which to dissect by injecting the bupivacaine/ epinephrine solution into the vaginal epithelium. This technique also ensures that the vaginal epithelial incisions won’t bleed.

Now, tilt the Jacobs tenaculum downward and push the junction of the cervix with the bladder reflection toward you so that you have a good sense of how deeply to incise.

Once you’ve made the incision, reclamp the Jacobs tenaculum so that it holds all of that tissue, and repeat the maneuver, tilting the clamp downward and pushing the junction toward you. In this way, you create traction and countertraction, sweeping the tissue out of your way.

Always use sharp dissection. When adhesions are present, surgeons often get into trouble using blunt dissection and may inadvertently enter the bladder if they use a sponge-covered digit for dissection, because adhesions can be much denser than normal tissue. In such cases, the bladder tears open rather than the adhesions being swept away.

Consider this: You don’t need to enter the peritoneal cavity anteriorly in order to continue working on the procedure. You can safely protect the bladder throughout the case, until the very end, if necessary, in patients who have undergone multiple previous surgeries or cesarean deliveries.

Rather than enter the anterior peritoneum, I dissect as much of the vaginal epithelium as possible and place a second Deaver retractor posteriorly.

I massage the uterosacral ligament for about 10 seconds to lengthen it and create more descensus, then place a Ballantine Heaney clamp on the ligament.

Next, I cut the pedicle and suture it, maintaining a clamp on the uterosacral ligament suture so that I can use it later for repair of the vaginal cuff.

I recommend a vessel-sealing device to secure the major blood supply, but I do suture the uterosacral and round ligaments for attachment to the apex at the conclusion of the hysterectomy. I suggest that you place straight clamps to hold the uterosacral ligament sutures and curved clamps on the round ligament ties to help you keep track of what you’re doing.

I generally prefer to use a smaller vessel-sealing device, such as the LigaSure Max (Covidien), because it allows me to take very small bites of tissue. It is also less expensive because it uses a disposable electrode within a reusable Heaney-type clamp.

Many people have argued that we need to teach surgeons to suture vaginally and, for that reason, should avoid vessel sealing. My response: Why wouldn’t we want to use the very best technology available? Randomized trials have demonstrated a 50% reduction in pain relief postoperatively when we use vessel sealing.4 Less foreign material is left in the pelvis, lowering the risk of infection. And it really doesn’t matter which vessel-sealing technology you use, as long as you’re familiar with the specifics of the system you choose. Another advantage: There is no need to pass needles back and forth.

Take small bites of tissue

Because this patient has a very small uterus, a small bite of tissue will get you close to where you want to be. When you take a bite with the vessel sealer, try to protect the vaginal epithelium and vulva from the steam that is emitted. The clamp itself does not heat up, but the steam that is released from the tissue is 100° C, so place a finger between the clamp and the sidewall for protection. It is preferable to burn your own finger than to burn the patient.

Because you haven’t entered the peritoneal cavity anteriorly, it is important to ensure that you don’t take too big of a bite with the vessel sealer. Rather, stay where you know you’ve done your dissection, where things are safe.

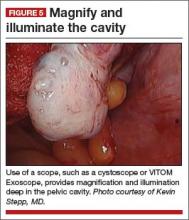

One cardinal principle of surgery is that you shouldn’t operate where you can’t feel or see. One of the common errors in vaginal surgery is that surgeons start dissecting higher than they can see. It’s easy to get into trouble when you start pushing tissue or dissecting tissue that you can’t visualize.

At this point, the anterior Deaver retractor is not essential, so I remove it. If you don’t need it, don’t use it. I try to avoid metal when I can.

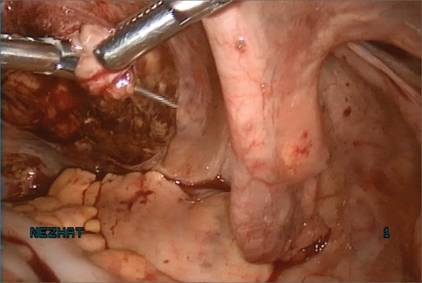

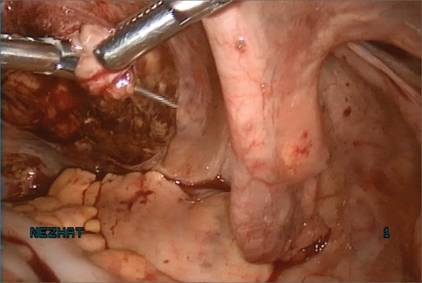

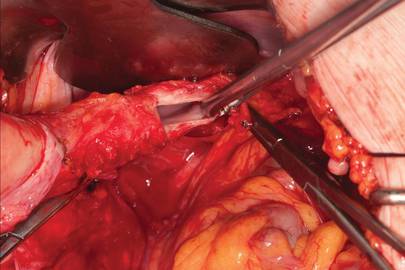

If I were using suture rather than vessel sealing, I would place a Heaney clamp on the uterosacral ligament and cut. Using a clamp-cut-tie technique, I would pull on the pedicle and cut just beyond the tip of the clamp to ensure that the suture will be secure (FIGURE 4). This approach would not be appropriate during use of a vessel sealer. In that case, you would want to cut to but not beyond the tip of the clamp.

One of the skills helpful in suturing is learning to move your elbow and wrist to achieve the proper angle. Determine where you want the suture to exit the tissue, and then angle your elbow and wrist so that the suture comes out where you want it. It’s easy to lose track of the needle tip, especially when you’re working in a limited space under the pubic symphysis, so use your shoulder, elbow, and wrist to control

suture placement.

Protect the anterior epithelium

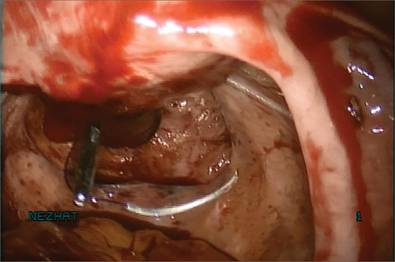

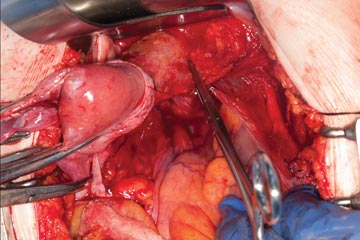

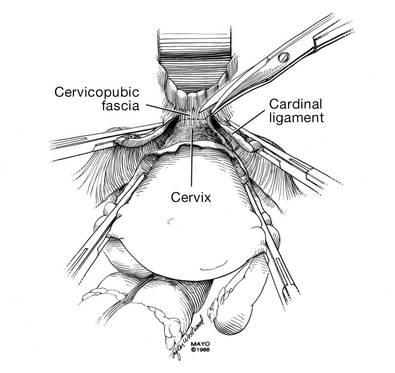

Because you have not yet entered the peritoneal cavity anteriorly, it is important to protect the anterior epithelium and bladder. Reinsert a narrow Deaver retractor anteriorly, remove the Jacobs clamp, and replace the clamp laterally so that the cervix can be pulled off to the side (FIGURE 5).

One nice thing about some vessel sealers is that the surgeon can twist them in any direction. It isn’t necessary to move your hand; you simply move the device itself.

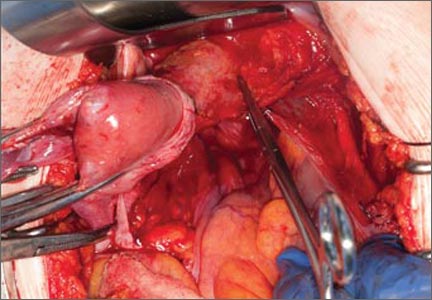

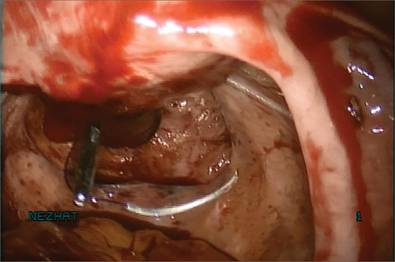

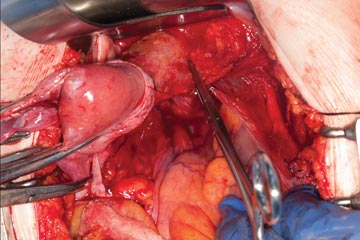

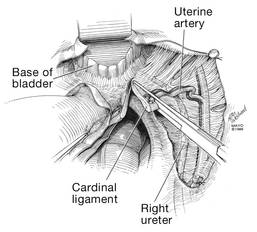

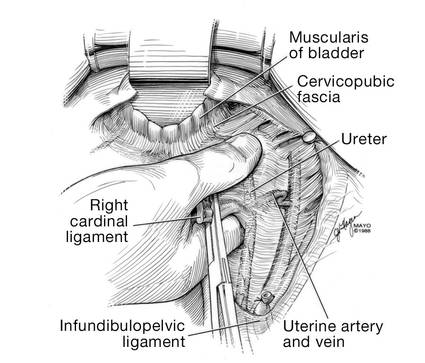

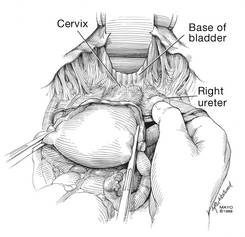

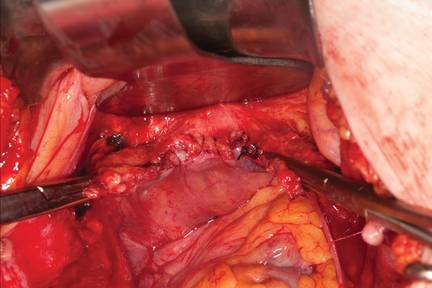

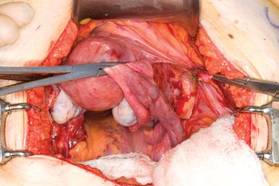

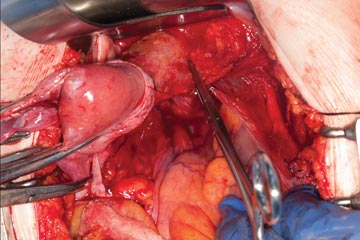

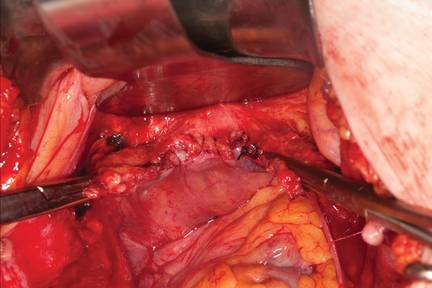

Once you have taken at least the descending branch of the uterine artery, remove the posterior retractor and pull downward on the Jacobs tenaculum. You should have reached just about to the level of the uterine fundus, with the anatomy well visualized (FIGURE 6). Next, open the anterior peritoneum.

Pay attention to the surgical field

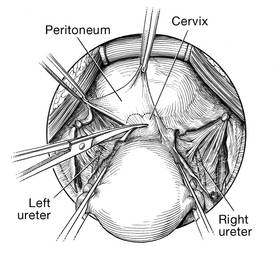

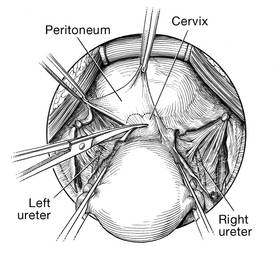

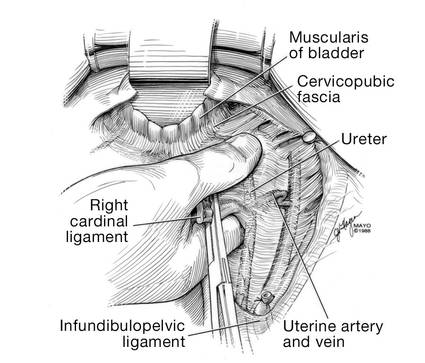

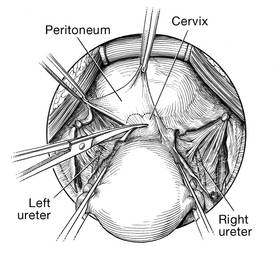

Now that you have entered the peritoneum anteriorly as well as posteriorly, identify the broad ligament, keeping in mind that the ureter is retroperitoneal, not intraperitoneal. If you were to place a clamp from the posterior leaf of the broad ligament across to the anterior leaf of the broad ligament, you would be grasping all the vessels but not the ureter. In fact, the anterior Deaver retractor is lifting both ureters up and out of the way. If you pull the cervix off to the opposite side, you create an additional couple of centimeters—a safe space for the vessel sealer

(FIGURE 7).

In placing the vessel sealer, there is no need to move out laterally, as there is no need for space to place suture. Instead, hug the uterus. At this point, the main concern is the risk of damaging any small bowel behind the uterine fundus that might be coming down into the surgical field, obscured from vision. And because there may be steam emitted at the tip of the vessel-sealing clamp, keep a finger back there to protect anything that might be in the field.

Last steps

Before taking the last bite of tissue on the right-hand side, place the round ligament in a Heaney clamp. Now that the round and utero-ovarian ligaments have been skeletonized, you can grasp the pedicle in a clamp. If the pedicle is especially thick, it may be beneficial to close the clamp, leave it on for a few seconds, and then reapply it. In that way, you obtain a better purchase.

Next, free the rest of the tissue with a vessel sealer, or cut it. I prefer to use a vessel sealer, and I again protect the adjacent tissue with my fingers anteriorly and posteriorly.

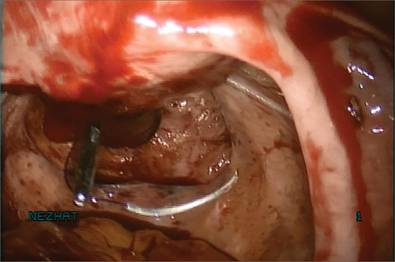

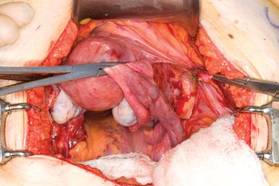

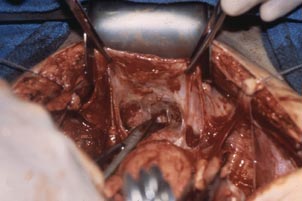

With the clamp remaining on the round ligament and utero-ovarian ligament

(FIGURE 8), which will be sutured, push the uterine tissue out of the way, back into the pelvis, to make room for suturing.

Because a postmenopausal vulva may be cut by the suture, it’s important to take pains not to abrade that tissue. Once you have finished suturing the round/utero-ovarian pedicle, leave the needle on the suture so that you can reconnect the round ligament to the anterior pubocervical ring to reconstruct the vaginal apex. For safekeeping, clamp the needle out of the way and tuck it beneath the drape.

Switching to the other side, use a Lahey clamp to flip the uterus, then clamp the pedicle and use the vessel sealer to separate it, again protecting the tissue beneath and ahead of the clamp. Sometimes, with an especially thick pedicle, the vessel sealer will signal that the tissue hasn’t been completely sealed. In that case, get another purchase of the pedicle, protect the adjacent tissue, and seal again.

Once the uterus has been removed completely, suture the utero-ovarian and round ligament on this side.

One tip to aid in the placement of suture is to move your clamped tissue in such a way as to prevent inadvertent suturing of other tissue (FIGURE 9).

An additional strategy for pain relief at this point is to infiltrate the round ligaments with local anesthetic. We know that we’re working with higher-level fibers—T10 to T12—through the round ligaments. By infiltrating them with anesthetic, you achieve denser pain relief for post- operative management.

Uterine reduction strategies facilitate vaginal removal of tissue

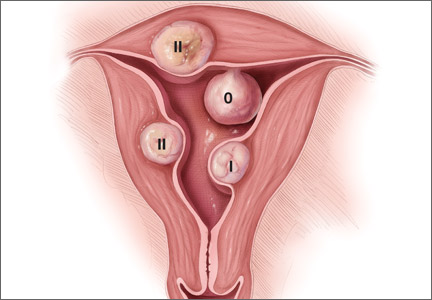

When the uterus is too large to remove intact through the vagina, there are a number of techniques for coring, wedging, and morcellating the tissue. As always, a complete knowledge of anatomy is essential, as well as an understanding that fibroids can frequently distort the uterus, twisting it to the left or right. It is important to anticipate such distortion to avoid the inadvertent destruction of anatomic landmarks or damage to the adnexae.

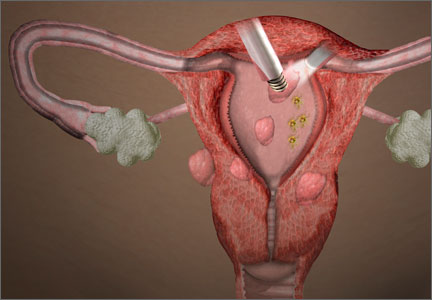

One straight-forward strategy is to debulk the uterus using a knife to core it, removing the central portion. In cases in which you need to keep the entire endometrial cavity intact, you can core the central portion of the uterus while grasping the cervix so that you can remove the endometrium intact for the pathologist (FIGURE).

For this strategy it is important to protect the vaginal sidewalls with metal. You can use another retractor to do that, pulling down on the cervix and beginning the morcellation. I generally prefer to use a short knife handle only because I want to be sure I’m not tempted to cut any higher than I can see.

For more on coring and wedging techniques, see the introductory video for the ACOG/SGS/AAGL master class on vaginal hysterectomy at http://www.aagl.org/vaghystwebinar.

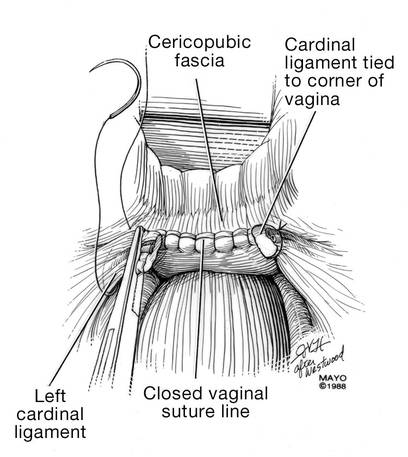

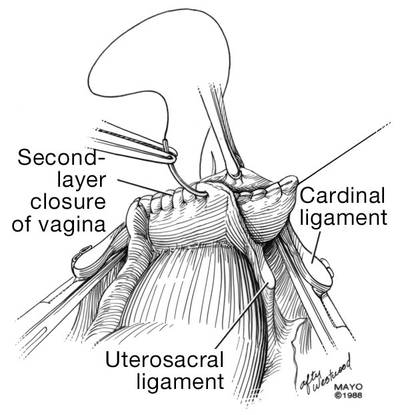

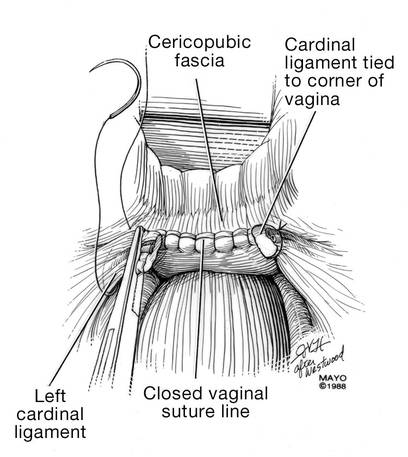

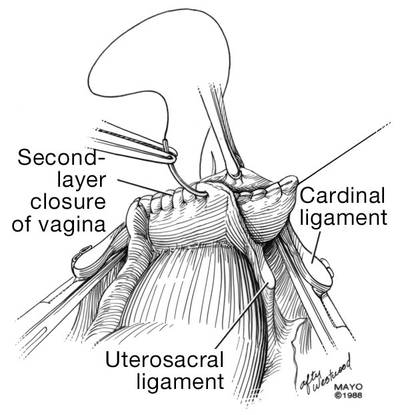

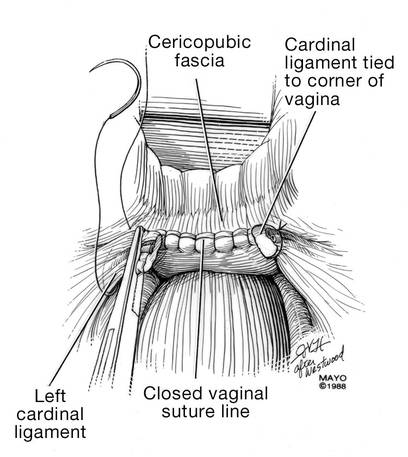

Close the vaginal cuff

The reconstruction of the vaginal cuff is a critical component of any hysterectomy. My approach is to reattach the uterosacral ligaments to the posterior cuff and the round ligaments to the anterior cuff, thereby re- creating an intact pubocervical ring. It is not necessary to include the peritoneum in the cuff closure. In fact, kinking of the ureters is more likely when the peritoneum is closed.

Attach one uterosacral ligament, then place a running, full-thickness stitch across the posterior cuff, and attach the uterosacral ligament on the opposite side. Use the needle you left attached to the round ligament to bring the right pedicle to the anterior cuff at 10 o’clock (be sure you grasp the full thickness of the vaginal epithelium without compromising the bladder). Attach the left round-ligament pedicle at the 2 o’clock position. Then close the cuff side to side down to the uterosacral ligaments. This completely reconstructs the pubocervical ring and provides excellent support at the apex.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery: Hysterectomy Options. http://www .brighamandwomens.org/Departments_and_Services/obgyn /services/mininvgynsurg/mininvoptions/hysterectomy.aspx. Published October 3, 2014. Accessed September 2, 2015.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2011 Women’s Health Stats & Facts. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2011. http://www.acog.org/~/media/NewsRoom/MediaKit.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2015.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 444: Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114(5):1156–1158.

- Silva-Filho AL, Rodrigues AM, Vale de Castro Monteiro M, et al. Randomized study of bipolar vessel sealing system versus conventional suture ligature for vaginal hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146(2):200–203.

In the United States, gynecologic surgeons remove approximately one uterus every minute of the year.1 That rate translates to more than 525,000 hysterectomies annually in this country alone. Yet, despite the widespread availability of information on the benefits of a vaginal approach to hysterectomy, the great majority of these operations—close to 50%—are still performed via an open abdominal approach.2

As I pointed out last month in my “Update on Vaginal Hysterectomy,” the vaginal approach not only is more cosmetically pleasing than laparoscopic and robot-assisted hysterectomy (not to mention open abdominal surgery) but also has a lower complication rate.3

As I also noted, one reason for the low rate of vaginal hysterectomy may be the assumption, on the part of many gynecologic surgeons, that the techniques and tools they learned to use during training are still the only options available today. That assumption is wrong.

In this article, I describe the technique for vaginal hysterectomy using basic instru mentation. This article is based on a master class in vaginal hysterectomy produced by the AAGL and co-sponsored by the Am erican College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. This master class offers continuing medical education credits and is avail able at http://www.aagl.org/vaghystwebinar.

For a look at innovative tools for this procedure, see my “Update on Vaginal Hysterectomy” in the September 2015 issue of this journal at obgmanagement.com.

Vaginal hysterectomy has few contraindications

Many commonly cited contraindications to the vaginal approach are not, in fact, absolute contraindications. An open or laparoscopic approach is preferred when the patient has a known cancer, of course, and when deep infiltrating endometriosis is present at the rectovaginal septum. However, previous pelvic surgery, nulliparity, an enlarged uterus, or lack of a prior vaginal delivery need not exclude the vaginal approach. Nor does a narrow introitus necessarily mandate a laparoscopic or open abdominal approach. In fact, in this article, I describe my basic technique in a patient (a cadaver) with a very narrow pubic arch, and I offer strategies for gaining some needed mobility and avoiding complications (TABLES 1 and 2).

Next month, in the November issue of OBG Management, John B. Gebhart, MD, will describe his vaginal technique for right salpingectomy with ovarian preservation, as well as his technique for right salpingo-oophorectomy.

Proper patient positioning is key

You can simplify the operation by positioning the patient so that her buttocks are over the edge of the table fairly far—at least 1 inch beyond the edge of the table for optimal exposure and greater access. If the patient is thin, it then becomes important to pad the sacrum because, when she is positioned that far off the table, all her weight comes to rest on the sacrum. In overweight patients, this is not an issue, but for thin patients, I place a bit of egg crate or gel beneath the sacrum.

For the procedure, I prefer to place my instruments on a tray that is kept on my lap. This arrangement frees the scrub technician from having to hand tools over my shoulder—and it saves time. I use a narrow, covered Mayo stand, and I place a stepstool beneath my feet to keep my knees at right angles so that things don’t slip during the operation.

Surgical technique

Choose an appropriate retractor

In a woman with a narrow introitus, I find that a posterior weighted speculum takes up too much space. Once I place a clamp on the cervix with that speculum in place, I don’t have much room to work. However, if I substitute a small Deaver retractor, which is narrower, I gain more workspace.

Inject the uterosacral ligaments

Grasp the cervix using a Jacobs vulsellum tenaculum. Use of a single tenaculum allows for much more movement than the use of instruments placed anteriorly and posteriorly. The Jacobs tenaculum obtains a better purchase on the tissue than a single tooth and is considerably less likely to tear through the tissue.

Before beginning the hysterectomy, locate the uterosacral ligaments and inject each one at its junction with the cervix, aspirating slightly before infiltrating the ligament with 0.25% to 0.50% bupivacaine with epinephrine, with dilute vasopressin mixed in. (I place 1 unit in 20 mL of the local solution.) Injection of this solution achieves 2 goals:

- improved intraoperative hemostasis

- postoperative pain relief.

Use a short needle with a needle extender attached to a control syringe rather than a spinal needle for greater control.

Enter the posterior peritoneal cavity

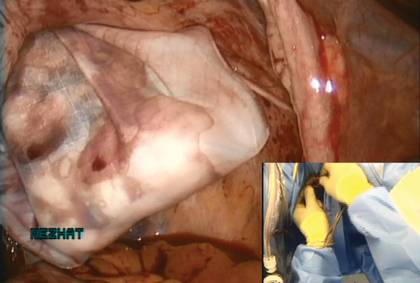

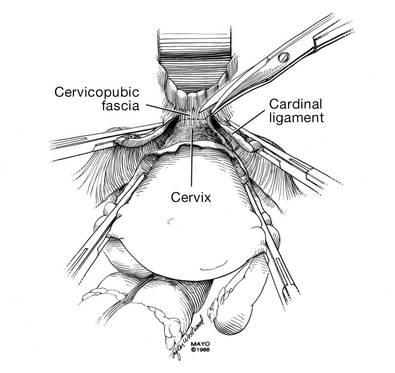

Before entering the peritoneal cavity, create a right angle with the Jacobs tenaculum and Deaver retractor in relation to the surgical field (FIGURE 1). This right angle is difficult to achieve when you are using a weighted speculum in a tight vagina. Once you have a right angle, tent the vaginal tissue in the midline (FIGURE 2).

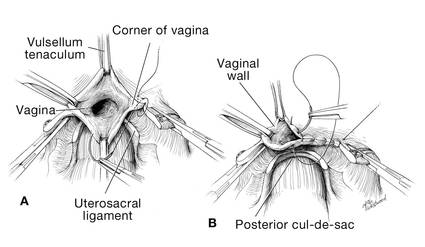

In a nulliparous patient or a woman with a tight pelvis, you may discover that the peritoneum is pulled up between the uterosacral ligaments. One common pitfall arises when the surgeon, having dissected the vaginal epithelium, continues cutting into the vaginal epithelium instead of reaching into the peritoneal cavity. Palpate the tissue to ensure that there is no bowel in the way and stay at right angles while confidently grasping the peritoneum with a toothed forceps.

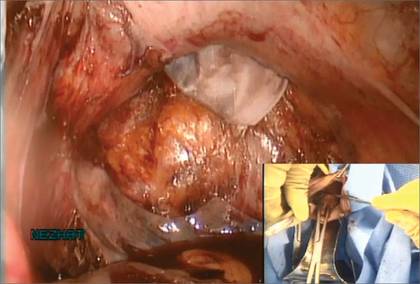

I like to use a bit of electrosurgery to incise the vaginal wall. I don’t begin at the cervix but incise more distally into the vaginal epithelium approximately 2 cm from the cervicovaginal junction. This strategy prevents dissection into the cervix and/or rectovaginal septum rather than the posterior

cul-de-sac (FIGURE 3).

Once the incision is made, it is possible to feel the posterior peritoneum. And as you tent the peritoneum, you can then very confidently extend the incision and enter the cavity posteriorly.

In a patient with significant adhesions such as this one, I feel around posteriorly to determine exactly where I am. One tactic I use is to release the tenaculum and regrasp the cervix with it. This allows for improved visualization and movement of the cervix as the procedure progresses. Depending on the case, it may be necessary to insert a sponge to hold bowel out of the way.

Avoid the bladder

Move the Deaver retractor to the anterior position, switch the Jacobs clamp to the anterior cervix, and pull straight down. Now that you have incised the vaginal epithelium posteriorly, the length of the cervix should be apparent to you, and you can easily determine the location of the bladder reflection.

Keep in mind that, in a postmenopausal patient, there will be fewer vaginal rugae to guide you. Place the Jacobs tenaculum as close to the midline as possible so that you can confidently grab the tissue without fear of grabbing the bladder. If you tilt the Jacobs clamp, you can feel the edge of the bladder reflection. Remember that postmenopausal patients with prolapse (or, occasionally, obese patients with cervical elongation but little actual descensus) may have altered anatomy.

You can create a bit more space in which to dissect by injecting the bupivacaine/ epinephrine solution into the vaginal epithelium. This technique also ensures that the vaginal epithelial incisions won’t bleed.

Now, tilt the Jacobs tenaculum downward and push the junction of the cervix with the bladder reflection toward you so that you have a good sense of how deeply to incise.

Once you’ve made the incision, reclamp the Jacobs tenaculum so that it holds all of that tissue, and repeat the maneuver, tilting the clamp downward and pushing the junction toward you. In this way, you create traction and countertraction, sweeping the tissue out of your way.

Always use sharp dissection. When adhesions are present, surgeons often get into trouble using blunt dissection and may inadvertently enter the bladder if they use a sponge-covered digit for dissection, because adhesions can be much denser than normal tissue. In such cases, the bladder tears open rather than the adhesions being swept away.

Consider this: You don’t need to enter the peritoneal cavity anteriorly in order to continue working on the procedure. You can safely protect the bladder throughout the case, until the very end, if necessary, in patients who have undergone multiple previous surgeries or cesarean deliveries.

Rather than enter the anterior peritoneum, I dissect as much of the vaginal epithelium as possible and place a second Deaver retractor posteriorly.

I massage the uterosacral ligament for about 10 seconds to lengthen it and create more descensus, then place a Ballantine Heaney clamp on the ligament.

Next, I cut the pedicle and suture it, maintaining a clamp on the uterosacral ligament suture so that I can use it later for repair of the vaginal cuff.

I recommend a vessel-sealing device to secure the major blood supply, but I do suture the uterosacral and round ligaments for attachment to the apex at the conclusion of the hysterectomy. I suggest that you place straight clamps to hold the uterosacral ligament sutures and curved clamps on the round ligament ties to help you keep track of what you’re doing.

I generally prefer to use a smaller vessel-sealing device, such as the LigaSure Max (Covidien), because it allows me to take very small bites of tissue. It is also less expensive because it uses a disposable electrode within a reusable Heaney-type clamp.

Many people have argued that we need to teach surgeons to suture vaginally and, for that reason, should avoid vessel sealing. My response: Why wouldn’t we want to use the very best technology available? Randomized trials have demonstrated a 50% reduction in pain relief postoperatively when we use vessel sealing.4 Less foreign material is left in the pelvis, lowering the risk of infection. And it really doesn’t matter which vessel-sealing technology you use, as long as you’re familiar with the specifics of the system you choose. Another advantage: There is no need to pass needles back and forth.

Take small bites of tissue

Because this patient has a very small uterus, a small bite of tissue will get you close to where you want to be. When you take a bite with the vessel sealer, try to protect the vaginal epithelium and vulva from the steam that is emitted. The clamp itself does not heat up, but the steam that is released from the tissue is 100° C, so place a finger between the clamp and the sidewall for protection. It is preferable to burn your own finger than to burn the patient.

Because you haven’t entered the peritoneal cavity anteriorly, it is important to ensure that you don’t take too big of a bite with the vessel sealer. Rather, stay where you know you’ve done your dissection, where things are safe.

One cardinal principle of surgery is that you shouldn’t operate where you can’t feel or see. One of the common errors in vaginal surgery is that surgeons start dissecting higher than they can see. It’s easy to get into trouble when you start pushing tissue or dissecting tissue that you can’t visualize.

At this point, the anterior Deaver retractor is not essential, so I remove it. If you don’t need it, don’t use it. I try to avoid metal when I can.

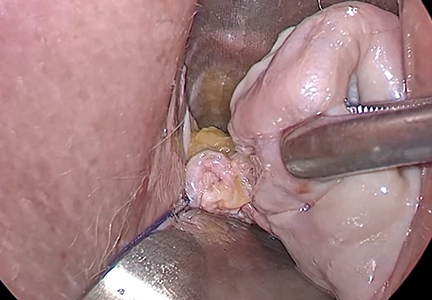

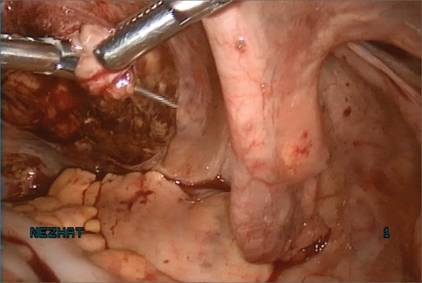

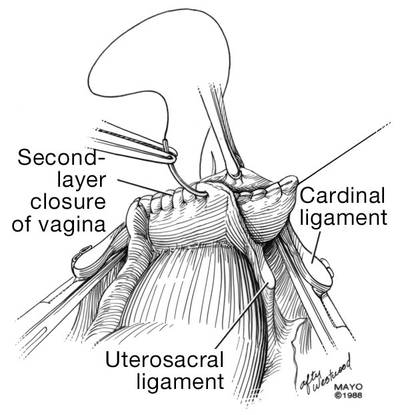

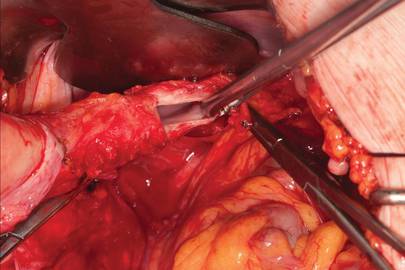

If I were using suture rather than vessel sealing, I would place a Heaney clamp on the uterosacral ligament and cut. Using a clamp-cut-tie technique, I would pull on the pedicle and cut just beyond the tip of the clamp to ensure that the suture will be secure (FIGURE 4). This approach would not be appropriate during use of a vessel sealer. In that case, you would want to cut to but not beyond the tip of the clamp.

One of the skills helpful in suturing is learning to move your elbow and wrist to achieve the proper angle. Determine where you want the suture to exit the tissue, and then angle your elbow and wrist so that the suture comes out where you want it. It’s easy to lose track of the needle tip, especially when you’re working in a limited space under the pubic symphysis, so use your shoulder, elbow, and wrist to control

suture placement.

Protect the anterior epithelium

Because you have not yet entered the peritoneal cavity anteriorly, it is important to protect the anterior epithelium and bladder. Reinsert a narrow Deaver retractor anteriorly, remove the Jacobs clamp, and replace the clamp laterally so that the cervix can be pulled off to the side (FIGURE 5).

One nice thing about some vessel sealers is that the surgeon can twist them in any direction. It isn’t necessary to move your hand; you simply move the device itself.

Once you have taken at least the descending branch of the uterine artery, remove the posterior retractor and pull downward on the Jacobs tenaculum. You should have reached just about to the level of the uterine fundus, with the anatomy well visualized (FIGURE 6). Next, open the anterior peritoneum.

Pay attention to the surgical field

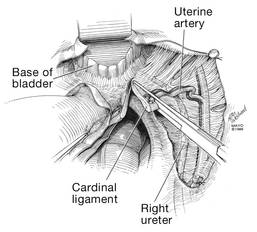

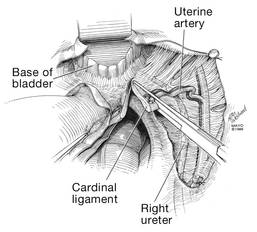

Now that you have entered the peritoneum anteriorly as well as posteriorly, identify the broad ligament, keeping in mind that the ureter is retroperitoneal, not intraperitoneal. If you were to place a clamp from the posterior leaf of the broad ligament across to the anterior leaf of the broad ligament, you would be grasping all the vessels but not the ureter. In fact, the anterior Deaver retractor is lifting both ureters up and out of the way. If you pull the cervix off to the opposite side, you create an additional couple of centimeters—a safe space for the vessel sealer

(FIGURE 7).

In placing the vessel sealer, there is no need to move out laterally, as there is no need for space to place suture. Instead, hug the uterus. At this point, the main concern is the risk of damaging any small bowel behind the uterine fundus that might be coming down into the surgical field, obscured from vision. And because there may be steam emitted at the tip of the vessel-sealing clamp, keep a finger back there to protect anything that might be in the field.

Last steps

Before taking the last bite of tissue on the right-hand side, place the round ligament in a Heaney clamp. Now that the round and utero-ovarian ligaments have been skeletonized, you can grasp the pedicle in a clamp. If the pedicle is especially thick, it may be beneficial to close the clamp, leave it on for a few seconds, and then reapply it. In that way, you obtain a better purchase.

Next, free the rest of the tissue with a vessel sealer, or cut it. I prefer to use a vessel sealer, and I again protect the adjacent tissue with my fingers anteriorly and posteriorly.

With the clamp remaining on the round ligament and utero-ovarian ligament

(FIGURE 8), which will be sutured, push the uterine tissue out of the way, back into the pelvis, to make room for suturing.

Because a postmenopausal vulva may be cut by the suture, it’s important to take pains not to abrade that tissue. Once you have finished suturing the round/utero-ovarian pedicle, leave the needle on the suture so that you can reconnect the round ligament to the anterior pubocervical ring to reconstruct the vaginal apex. For safekeeping, clamp the needle out of the way and tuck it beneath the drape.

Switching to the other side, use a Lahey clamp to flip the uterus, then clamp the pedicle and use the vessel sealer to separate it, again protecting the tissue beneath and ahead of the clamp. Sometimes, with an especially thick pedicle, the vessel sealer will signal that the tissue hasn’t been completely sealed. In that case, get another purchase of the pedicle, protect the adjacent tissue, and seal again.

Once the uterus has been removed completely, suture the utero-ovarian and round ligament on this side.

One tip to aid in the placement of suture is to move your clamped tissue in such a way as to prevent inadvertent suturing of other tissue (FIGURE 9).

An additional strategy for pain relief at this point is to infiltrate the round ligaments with local anesthetic. We know that we’re working with higher-level fibers—T10 to T12—through the round ligaments. By infiltrating them with anesthetic, you achieve denser pain relief for post- operative management.

Uterine reduction strategies facilitate vaginal removal of tissue

When the uterus is too large to remove intact through the vagina, there are a number of techniques for coring, wedging, and morcellating the tissue. As always, a complete knowledge of anatomy is essential, as well as an understanding that fibroids can frequently distort the uterus, twisting it to the left or right. It is important to anticipate such distortion to avoid the inadvertent destruction of anatomic landmarks or damage to the adnexae.

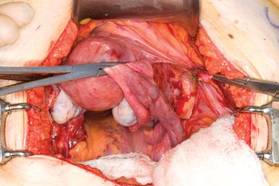

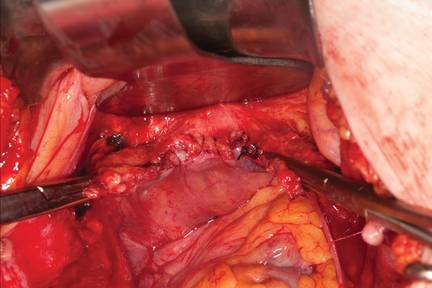

One straight-forward strategy is to debulk the uterus using a knife to core it, removing the central portion. In cases in which you need to keep the entire endometrial cavity intact, you can core the central portion of the uterus while grasping the cervix so that you can remove the endometrium intact for the pathologist (FIGURE).

For this strategy it is important to protect the vaginal sidewalls with metal. You can use another retractor to do that, pulling down on the cervix and beginning the morcellation. I generally prefer to use a short knife handle only because I want to be sure I’m not tempted to cut any higher than I can see.

For more on coring and wedging techniques, see the introductory video for the ACOG/SGS/AAGL master class on vaginal hysterectomy at http://www.aagl.org/vaghystwebinar.

Close the vaginal cuff

The reconstruction of the vaginal cuff is a critical component of any hysterectomy. My approach is to reattach the uterosacral ligaments to the posterior cuff and the round ligaments to the anterior cuff, thereby re- creating an intact pubocervical ring. It is not necessary to include the peritoneum in the cuff closure. In fact, kinking of the ureters is more likely when the peritoneum is closed.

Attach one uterosacral ligament, then place a running, full-thickness stitch across the posterior cuff, and attach the uterosacral ligament on the opposite side. Use the needle you left attached to the round ligament to bring the right pedicle to the anterior cuff at 10 o’clock (be sure you grasp the full thickness of the vaginal epithelium without compromising the bladder). Attach the left round-ligament pedicle at the 2 o’clock position. Then close the cuff side to side down to the uterosacral ligaments. This completely reconstructs the pubocervical ring and provides excellent support at the apex.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In the United States, gynecologic surgeons remove approximately one uterus every minute of the year.1 That rate translates to more than 525,000 hysterectomies annually in this country alone. Yet, despite the widespread availability of information on the benefits of a vaginal approach to hysterectomy, the great majority of these operations—close to 50%—are still performed via an open abdominal approach.2

As I pointed out last month in my “Update on Vaginal Hysterectomy,” the vaginal approach not only is more cosmetically pleasing than laparoscopic and robot-assisted hysterectomy (not to mention open abdominal surgery) but also has a lower complication rate.3

As I also noted, one reason for the low rate of vaginal hysterectomy may be the assumption, on the part of many gynecologic surgeons, that the techniques and tools they learned to use during training are still the only options available today. That assumption is wrong.

In this article, I describe the technique for vaginal hysterectomy using basic instru mentation. This article is based on a master class in vaginal hysterectomy produced by the AAGL and co-sponsored by the Am erican College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. This master class offers continuing medical education credits and is avail able at http://www.aagl.org/vaghystwebinar.

For a look at innovative tools for this procedure, see my “Update on Vaginal Hysterectomy” in the September 2015 issue of this journal at obgmanagement.com.

Vaginal hysterectomy has few contraindications

Many commonly cited contraindications to the vaginal approach are not, in fact, absolute contraindications. An open or laparoscopic approach is preferred when the patient has a known cancer, of course, and when deep infiltrating endometriosis is present at the rectovaginal septum. However, previous pelvic surgery, nulliparity, an enlarged uterus, or lack of a prior vaginal delivery need not exclude the vaginal approach. Nor does a narrow introitus necessarily mandate a laparoscopic or open abdominal approach. In fact, in this article, I describe my basic technique in a patient (a cadaver) with a very narrow pubic arch, and I offer strategies for gaining some needed mobility and avoiding complications (TABLES 1 and 2).

Next month, in the November issue of OBG Management, John B. Gebhart, MD, will describe his vaginal technique for right salpingectomy with ovarian preservation, as well as his technique for right salpingo-oophorectomy.

Proper patient positioning is key

You can simplify the operation by positioning the patient so that her buttocks are over the edge of the table fairly far—at least 1 inch beyond the edge of the table for optimal exposure and greater access. If the patient is thin, it then becomes important to pad the sacrum because, when she is positioned that far off the table, all her weight comes to rest on the sacrum. In overweight patients, this is not an issue, but for thin patients, I place a bit of egg crate or gel beneath the sacrum.

For the procedure, I prefer to place my instruments on a tray that is kept on my lap. This arrangement frees the scrub technician from having to hand tools over my shoulder—and it saves time. I use a narrow, covered Mayo stand, and I place a stepstool beneath my feet to keep my knees at right angles so that things don’t slip during the operation.

Surgical technique

Choose an appropriate retractor

In a woman with a narrow introitus, I find that a posterior weighted speculum takes up too much space. Once I place a clamp on the cervix with that speculum in place, I don’t have much room to work. However, if I substitute a small Deaver retractor, which is narrower, I gain more workspace.

Inject the uterosacral ligaments

Grasp the cervix using a Jacobs vulsellum tenaculum. Use of a single tenaculum allows for much more movement than the use of instruments placed anteriorly and posteriorly. The Jacobs tenaculum obtains a better purchase on the tissue than a single tooth and is considerably less likely to tear through the tissue.

Before beginning the hysterectomy, locate the uterosacral ligaments and inject each one at its junction with the cervix, aspirating slightly before infiltrating the ligament with 0.25% to 0.50% bupivacaine with epinephrine, with dilute vasopressin mixed in. (I place 1 unit in 20 mL of the local solution.) Injection of this solution achieves 2 goals:

- improved intraoperative hemostasis

- postoperative pain relief.

Use a short needle with a needle extender attached to a control syringe rather than a spinal needle for greater control.

Enter the posterior peritoneal cavity

Before entering the peritoneal cavity, create a right angle with the Jacobs tenaculum and Deaver retractor in relation to the surgical field (FIGURE 1). This right angle is difficult to achieve when you are using a weighted speculum in a tight vagina. Once you have a right angle, tent the vaginal tissue in the midline (FIGURE 2).

In a nulliparous patient or a woman with a tight pelvis, you may discover that the peritoneum is pulled up between the uterosacral ligaments. One common pitfall arises when the surgeon, having dissected the vaginal epithelium, continues cutting into the vaginal epithelium instead of reaching into the peritoneal cavity. Palpate the tissue to ensure that there is no bowel in the way and stay at right angles while confidently grasping the peritoneum with a toothed forceps.

I like to use a bit of electrosurgery to incise the vaginal wall. I don’t begin at the cervix but incise more distally into the vaginal epithelium approximately 2 cm from the cervicovaginal junction. This strategy prevents dissection into the cervix and/or rectovaginal septum rather than the posterior

cul-de-sac (FIGURE 3).

Once the incision is made, it is possible to feel the posterior peritoneum. And as you tent the peritoneum, you can then very confidently extend the incision and enter the cavity posteriorly.

In a patient with significant adhesions such as this one, I feel around posteriorly to determine exactly where I am. One tactic I use is to release the tenaculum and regrasp the cervix with it. This allows for improved visualization and movement of the cervix as the procedure progresses. Depending on the case, it may be necessary to insert a sponge to hold bowel out of the way.

Avoid the bladder

Move the Deaver retractor to the anterior position, switch the Jacobs clamp to the anterior cervix, and pull straight down. Now that you have incised the vaginal epithelium posteriorly, the length of the cervix should be apparent to you, and you can easily determine the location of the bladder reflection.

Keep in mind that, in a postmenopausal patient, there will be fewer vaginal rugae to guide you. Place the Jacobs tenaculum as close to the midline as possible so that you can confidently grab the tissue without fear of grabbing the bladder. If you tilt the Jacobs clamp, you can feel the edge of the bladder reflection. Remember that postmenopausal patients with prolapse (or, occasionally, obese patients with cervical elongation but little actual descensus) may have altered anatomy.

You can create a bit more space in which to dissect by injecting the bupivacaine/ epinephrine solution into the vaginal epithelium. This technique also ensures that the vaginal epithelial incisions won’t bleed.

Now, tilt the Jacobs tenaculum downward and push the junction of the cervix with the bladder reflection toward you so that you have a good sense of how deeply to incise.

Once you’ve made the incision, reclamp the Jacobs tenaculum so that it holds all of that tissue, and repeat the maneuver, tilting the clamp downward and pushing the junction toward you. In this way, you create traction and countertraction, sweeping the tissue out of your way.

Always use sharp dissection. When adhesions are present, surgeons often get into trouble using blunt dissection and may inadvertently enter the bladder if they use a sponge-covered digit for dissection, because adhesions can be much denser than normal tissue. In such cases, the bladder tears open rather than the adhesions being swept away.

Consider this: You don’t need to enter the peritoneal cavity anteriorly in order to continue working on the procedure. You can safely protect the bladder throughout the case, until the very end, if necessary, in patients who have undergone multiple previous surgeries or cesarean deliveries.

Rather than enter the anterior peritoneum, I dissect as much of the vaginal epithelium as possible and place a second Deaver retractor posteriorly.

I massage the uterosacral ligament for about 10 seconds to lengthen it and create more descensus, then place a Ballantine Heaney clamp on the ligament.

Next, I cut the pedicle and suture it, maintaining a clamp on the uterosacral ligament suture so that I can use it later for repair of the vaginal cuff.

I recommend a vessel-sealing device to secure the major blood supply, but I do suture the uterosacral and round ligaments for attachment to the apex at the conclusion of the hysterectomy. I suggest that you place straight clamps to hold the uterosacral ligament sutures and curved clamps on the round ligament ties to help you keep track of what you’re doing.

I generally prefer to use a smaller vessel-sealing device, such as the LigaSure Max (Covidien), because it allows me to take very small bites of tissue. It is also less expensive because it uses a disposable electrode within a reusable Heaney-type clamp.

Many people have argued that we need to teach surgeons to suture vaginally and, for that reason, should avoid vessel sealing. My response: Why wouldn’t we want to use the very best technology available? Randomized trials have demonstrated a 50% reduction in pain relief postoperatively when we use vessel sealing.4 Less foreign material is left in the pelvis, lowering the risk of infection. And it really doesn’t matter which vessel-sealing technology you use, as long as you’re familiar with the specifics of the system you choose. Another advantage: There is no need to pass needles back and forth.

Take small bites of tissue

Because this patient has a very small uterus, a small bite of tissue will get you close to where you want to be. When you take a bite with the vessel sealer, try to protect the vaginal epithelium and vulva from the steam that is emitted. The clamp itself does not heat up, but the steam that is released from the tissue is 100° C, so place a finger between the clamp and the sidewall for protection. It is preferable to burn your own finger than to burn the patient.

Because you haven’t entered the peritoneal cavity anteriorly, it is important to ensure that you don’t take too big of a bite with the vessel sealer. Rather, stay where you know you’ve done your dissection, where things are safe.

One cardinal principle of surgery is that you shouldn’t operate where you can’t feel or see. One of the common errors in vaginal surgery is that surgeons start dissecting higher than they can see. It’s easy to get into trouble when you start pushing tissue or dissecting tissue that you can’t visualize.

At this point, the anterior Deaver retractor is not essential, so I remove it. If you don’t need it, don’t use it. I try to avoid metal when I can.

If I were using suture rather than vessel sealing, I would place a Heaney clamp on the uterosacral ligament and cut. Using a clamp-cut-tie technique, I would pull on the pedicle and cut just beyond the tip of the clamp to ensure that the suture will be secure (FIGURE 4). This approach would not be appropriate during use of a vessel sealer. In that case, you would want to cut to but not beyond the tip of the clamp.

One of the skills helpful in suturing is learning to move your elbow and wrist to achieve the proper angle. Determine where you want the suture to exit the tissue, and then angle your elbow and wrist so that the suture comes out where you want it. It’s easy to lose track of the needle tip, especially when you’re working in a limited space under the pubic symphysis, so use your shoulder, elbow, and wrist to control

suture placement.

Protect the anterior epithelium

Because you have not yet entered the peritoneal cavity anteriorly, it is important to protect the anterior epithelium and bladder. Reinsert a narrow Deaver retractor anteriorly, remove the Jacobs clamp, and replace the clamp laterally so that the cervix can be pulled off to the side (FIGURE 5).

One nice thing about some vessel sealers is that the surgeon can twist them in any direction. It isn’t necessary to move your hand; you simply move the device itself.

Once you have taken at least the descending branch of the uterine artery, remove the posterior retractor and pull downward on the Jacobs tenaculum. You should have reached just about to the level of the uterine fundus, with the anatomy well visualized (FIGURE 6). Next, open the anterior peritoneum.

Pay attention to the surgical field

Now that you have entered the peritoneum anteriorly as well as posteriorly, identify the broad ligament, keeping in mind that the ureter is retroperitoneal, not intraperitoneal. If you were to place a clamp from the posterior leaf of the broad ligament across to the anterior leaf of the broad ligament, you would be grasping all the vessels but not the ureter. In fact, the anterior Deaver retractor is lifting both ureters up and out of the way. If you pull the cervix off to the opposite side, you create an additional couple of centimeters—a safe space for the vessel sealer

(FIGURE 7).

In placing the vessel sealer, there is no need to move out laterally, as there is no need for space to place suture. Instead, hug the uterus. At this point, the main concern is the risk of damaging any small bowel behind the uterine fundus that might be coming down into the surgical field, obscured from vision. And because there may be steam emitted at the tip of the vessel-sealing clamp, keep a finger back there to protect anything that might be in the field.

Last steps

Before taking the last bite of tissue on the right-hand side, place the round ligament in a Heaney clamp. Now that the round and utero-ovarian ligaments have been skeletonized, you can grasp the pedicle in a clamp. If the pedicle is especially thick, it may be beneficial to close the clamp, leave it on for a few seconds, and then reapply it. In that way, you obtain a better purchase.

Next, free the rest of the tissue with a vessel sealer, or cut it. I prefer to use a vessel sealer, and I again protect the adjacent tissue with my fingers anteriorly and posteriorly.

With the clamp remaining on the round ligament and utero-ovarian ligament

(FIGURE 8), which will be sutured, push the uterine tissue out of the way, back into the pelvis, to make room for suturing.

Because a postmenopausal vulva may be cut by the suture, it’s important to take pains not to abrade that tissue. Once you have finished suturing the round/utero-ovarian pedicle, leave the needle on the suture so that you can reconnect the round ligament to the anterior pubocervical ring to reconstruct the vaginal apex. For safekeeping, clamp the needle out of the way and tuck it beneath the drape.

Switching to the other side, use a Lahey clamp to flip the uterus, then clamp the pedicle and use the vessel sealer to separate it, again protecting the tissue beneath and ahead of the clamp. Sometimes, with an especially thick pedicle, the vessel sealer will signal that the tissue hasn’t been completely sealed. In that case, get another purchase of the pedicle, protect the adjacent tissue, and seal again.

Once the uterus has been removed completely, suture the utero-ovarian and round ligament on this side.

One tip to aid in the placement of suture is to move your clamped tissue in such a way as to prevent inadvertent suturing of other tissue (FIGURE 9).

An additional strategy for pain relief at this point is to infiltrate the round ligaments with local anesthetic. We know that we’re working with higher-level fibers—T10 to T12—through the round ligaments. By infiltrating them with anesthetic, you achieve denser pain relief for post- operative management.

Uterine reduction strategies facilitate vaginal removal of tissue

When the uterus is too large to remove intact through the vagina, there are a number of techniques for coring, wedging, and morcellating the tissue. As always, a complete knowledge of anatomy is essential, as well as an understanding that fibroids can frequently distort the uterus, twisting it to the left or right. It is important to anticipate such distortion to avoid the inadvertent destruction of anatomic landmarks or damage to the adnexae.

One straight-forward strategy is to debulk the uterus using a knife to core it, removing the central portion. In cases in which you need to keep the entire endometrial cavity intact, you can core the central portion of the uterus while grasping the cervix so that you can remove the endometrium intact for the pathologist (FIGURE).

For this strategy it is important to protect the vaginal sidewalls with metal. You can use another retractor to do that, pulling down on the cervix and beginning the morcellation. I generally prefer to use a short knife handle only because I want to be sure I’m not tempted to cut any higher than I can see.

For more on coring and wedging techniques, see the introductory video for the ACOG/SGS/AAGL master class on vaginal hysterectomy at http://www.aagl.org/vaghystwebinar.

Close the vaginal cuff

The reconstruction of the vaginal cuff is a critical component of any hysterectomy. My approach is to reattach the uterosacral ligaments to the posterior cuff and the round ligaments to the anterior cuff, thereby re- creating an intact pubocervical ring. It is not necessary to include the peritoneum in the cuff closure. In fact, kinking of the ureters is more likely when the peritoneum is closed.

Attach one uterosacral ligament, then place a running, full-thickness stitch across the posterior cuff, and attach the uterosacral ligament on the opposite side. Use the needle you left attached to the round ligament to bring the right pedicle to the anterior cuff at 10 o’clock (be sure you grasp the full thickness of the vaginal epithelium without compromising the bladder). Attach the left round-ligament pedicle at the 2 o’clock position. Then close the cuff side to side down to the uterosacral ligaments. This completely reconstructs the pubocervical ring and provides excellent support at the apex.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery: Hysterectomy Options. http://www .brighamandwomens.org/Departments_and_Services/obgyn /services/mininvgynsurg/mininvoptions/hysterectomy.aspx. Published October 3, 2014. Accessed September 2, 2015.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2011 Women’s Health Stats & Facts. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2011. http://www.acog.org/~/media/NewsRoom/MediaKit.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2015.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 444: Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114(5):1156–1158.

- Silva-Filho AL, Rodrigues AM, Vale de Castro Monteiro M, et al. Randomized study of bipolar vessel sealing system versus conventional suture ligature for vaginal hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146(2):200–203.

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery: Hysterectomy Options. http://www .brighamandwomens.org/Departments_and_Services/obgyn /services/mininvgynsurg/mininvoptions/hysterectomy.aspx. Published October 3, 2014. Accessed September 2, 2015.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2011 Women’s Health Stats & Facts. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2011. http://www.acog.org/~/media/NewsRoom/MediaKit.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2015.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 444: Choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 114(5):1156–1158.

- Silva-Filho AL, Rodrigues AM, Vale de Castro Monteiro M, et al. Randomized study of bipolar vessel sealing system versus conventional suture ligature for vaginal hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146(2):200–203.

In this Article

- 5 solutions to difficult vaginal access

- The need to take small bites of tissue

- Uterine reduction strategies

Local anesthesia for uterine procedures

A vaginoscopic approach to diagnostic hysteroscopy

In this video, diffuse complex endometrial hyperplasia is identified using a vaginoscopic approach with a 1.9-mm diagnostic rigid hysteroscope. The posterior fornix of the vagina is filled with saline until the cervix is elevated with the fluid and the cervical os is identified. The cervical canal is entered and gentle rotational movement and hydrodistension allows the canal to be traversed into the uterine cavity.

Video provided by Amy L. Garcia, MD

Read Dr. Garcia’s “Update on minimally invasive gynecology” (April 2015)

In this video, diffuse complex endometrial hyperplasia is identified using a vaginoscopic approach with a 1.9-mm diagnostic rigid hysteroscope. The posterior fornix of the vagina is filled with saline until the cervix is elevated with the fluid and the cervical os is identified. The cervical canal is entered and gentle rotational movement and hydrodistension allows the canal to be traversed into the uterine cavity.

Video provided by Amy L. Garcia, MD

Read Dr. Garcia’s “Update on minimally invasive gynecology” (April 2015)

In this video, diffuse complex endometrial hyperplasia is identified using a vaginoscopic approach with a 1.9-mm diagnostic rigid hysteroscope. The posterior fornix of the vagina is filled with saline until the cervix is elevated with the fluid and the cervical os is identified. The cervical canal is entered and gentle rotational movement and hydrodistension allows the canal to be traversed into the uterine cavity.

Video provided by Amy L. Garcia, MD

Read Dr. Garcia’s “Update on minimally invasive gynecology” (April 2015)

Tissue extraction at minimally invasive surgery: Where do we go from here?

The year 2014 marked a sea change in our approach to tissue extraction during minimally invasive surgery. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initiated this transformation in April, when it issued a safety warning on the use of open power morcellation.1 A flurry of statements on the practice followed from professional societies, capped, in late November, with another statement from the FDA.2–4 The new bottom line: The use of open electromechanical (“power”) morcellation is contraindicated in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women, as well as in those who are known or suspected to have a malignancy.4

Most of the concern to date has centered on the risk that an occult leiomyosarcoma could be morcellated inadvertently during uterine surgery, an event that may worsen the prognosis for the patient. To get a gynecologic oncologist’s take on the controversy, OBG Management caught up with Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, director of the Kelly Gynecologic Oncology Service at Johns Hopkins University. Dr. Fader’s perspective is unique in that she treats a relatively high number of patients who have leiomyosarcoma and other uterine cancers.

In this Q&A, we discuss the patient population at Johns Hopkins; why Dr. Fader is especially qualified to speak to the future of electromechanical morcellation in gynecologic surgery; the benefits and risks of minimally invasive surgery, including tissue extraction; her recommendations for preoperative evaluation and counseling of patients undergoing uterine surgery; and guidance on how the specialty of gynecologic surgery should proceed in the future.

OBG Management: Dr. Fader, by way of introduction, could you characterize your patient population?

Amanda Nickles Fader, MD: Like most gynecologic oncologists, I primarily treat women with cancers of the uterus, ovary, cervix, and vulva. Many of us also have the opportunity to treat a number of women each year with complex benign gynecologic conditions that require surgery. As someone who is extremely interested in rare gynecologic tumors, I also treat a relatively high volume of women diagnosed with uterine sarcoma.

Approximately 75% of the women I see in my practice have preinvasive or invasive cancer, and 25% have a benign condition, such as enlarged fibroids or advanced-stage endometriosis.

OBG Management: How many cases of uterine sarcoma do you encounter on an annual basis?

Dr. Fader: Uterine sarcomas are very rare. They represent only 2% of all uterine cancers. Put into perspective, that means that about 0.4 cases of leiomyosarcoma occur in every 100,000 US women—most commonly postmenopausal women. Leiomyosarcoma is a biologically aggressive, high-grade malignancy that often is lethal.5

Endometrial stroma sarcoma is even less common—only 0.3 cases occur in every 100,000 US women. However, this tumor type is more indolent, often diagnosed at an earlier stage, and potentially curable with surgery (with or without hormonal therapy).6

As a referral center for rare uterine tumors, the Kelly Gynecologic Oncology Service and the Sarcoma Center at Johns Hopkins see approximately 35 to 40 new cases of uterine sarcoma annually for treatment of primary disease or recurrence. An additional 15 to 20 consult cases are reviewed from outside hospitals each year by our gynecologic pathology department.

Why a minimally invasive approach is vital

OBG Management: When it comes to uterine surgery for presumed benign conditions, why is a minimally invasive approach important?

Dr. Fader: Minimally invasive surgery clearly benefits women and is one of the greatest advances of the past half-century within our field. Randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have demonstrated without question that women who undergo minimally invasive surgery for benign conditions or early-stage cancerous gynecologic conditions have superior clinical outcomes, compared with women who undergo surgery via laparotomy.7,8 These outcomes include fewer perioperative complications (including fewer cases of surgical site infection, venous thromboembolism, wound dehiscence, and hospital readmission), shorter hospital stays, less pain, faster recovery, and fewer adhesions. And when women with early-stage cancers undergo minimally invasive surgery, randomized controlled trials show, they have a stage-specific survival rate similar to that observed in women treated with laparotomy.9

Benefits and risks of tissue extraction in minimally invasive surgery

OBG Management: What are the main benefits of tissue extraction, including morcellation?

Dr. Fader: Tissue extraction is a practice that has allowed us to offer minimally invasive surgery to countless more women than we could have in the recent past. It is a technique in which a large specimen (typically a uterus or fibroid) is fragmented into smaller parts in order to remove it through a small laparoscopic incision or orifice (vagina, umbilicus). Without tissue-extraction practices, thousands of women who undergo myomectomy each year to conserve their fertility and hundreds of thousands of women who require hysterectomy potentially would have to undergo a more painful and risky surgery through a larger abdominal incision. That would not be desirable, as we know conclusively that laparotomy is associated with worse outcomes—and even an increased risk of mortality—compared with minimally invasive surgery performed by experienced surgeons.10

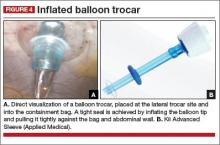

Tissue extraction can be approached in a variety of ways. It can be performed with a scalpel, with a resectoscope, or with an electromechanical morcellator. Tissue extraction can be performed within the uterine cavity, through the vagina, within the abdominal compartment, or within a containment system in any of those compartments.

OBG Management: What are the risks of tissue extraction?

Dr. Fader: The risks of tissue extraction with electromechanical morcellation include potential injury to intra-abdominal organs and vasculature and risk of dissemination of an occult (ie, undiagnosed) uterine cancer. A report by our research group also demonstrated the risks of dissemination of benign uterine tissue requiring subsequent surgery in the setting of open electromechanical morcellation.11 The risk of these events occurring in the hands of a thoughtful and experienced surgeon who conducts comprehensive preoperative patient evaluations is extremely low. However, recent evidence demonstrates that a handful of women worldwide are diagnosed with an occult uterine cancer each year during a morcellation procedure.12–14 Although it is a very rare event (given that most women undergoing hysterectomy and myomectomy procedures are of reproductive age and unlikely to have uterine cancer), this risk is a serious issue. There is an exigent need for the gynecologic surgical community to develop better approaches to tissue extraction that minimize preventable harm in women.

Needed: high-quality data on the risks of morcellation

OBG Management: How does the recent FDA statement urging caution with the use of open power morcellation factor into this equation? The most recent FDA statement noted that open power morcellation is contraindicated in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.4

Dr. Fader: The FDA’s concern is legitimate. However, the magnitude of the risk of occult uterine sarcoma in women undergoing presumed benign gynecologic surgery has been scrutinized and debated. The FDA panel quoted a risk that roughly 1 in 350 women undergoing presumed benign gynecologic surgery for fibroids will have an occult leiomyosarcoma diagnosed. However, more recent systematic reviews and a review of the prospective published literature demonstrate that the risk is more likely on the order of 1 in 1,700 to 1 in 8,333 women.15 The risk may be even lower in gynecologic surgery practices that see a high volume of hysterectomy/myomectomy cases and utilize meticulous preoperative patient selection criteria to establish a woman’s candidacy for tissue-extraction procedures.

I am concerned with how “occult sarcoma” discovered during surgery for “presumed benign gynecologic disease is being defined in the literature. There is no uniform definition being used. A cancer in this setting is only truly occult or undiagnosed if the physician was thinking about it and made every effort to rule out cancer preoperatively, and the morcellation procedure was performed in a low-risk population (but cancer was still diagnosed on final pathology in this population). However, in the majority of the morcellation studies in the literature, it is not clear that thorough preoperative evaluations occurred in patients to rule out uterine malignancy—in fact, there is a paucity of published information regarding establishing appropriate patient candidacy for morcellation procedures. So we can’t derive any conclusions regarding whether “occult” sarcomas were truly undetectable or not in the published literature.

In addition, the literature is very clear that advancing age and postmenopausal status are risk factors for uterine malignancy.16 The vast majority of uterine sarcoma cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women. Yet, in one large US population-based hysterectomy study, 20% of the morcellated cases (and the overwhelming majority of the “occult” morcellated uterine cancers) occurred in postmenopausal women!17

Further, in a more recent study by the same authors, again the risks of morcellating a uterine cancer in a population undergoing myomectomy was significantly higher in a postmenopausal population and occurred only rarely in women younger than age 40. But it should come as no surprise that a greater incidence of uterine cancer was identified in these older cohorts—cancer risk increases precipitously with age. That’s not “occult”; that’s basic cancer epidemiology.

In other words, we cannot assume from population-based administrative claims data that morcellation performed in inappropriate populations at higher risk of uterine malignancy (in which we do not know whether patients were properly screened for the procedure preoperatively or whether they had risk factors for uterine cancer but were presumably poor candidates for morcellation due to age alone) helps us define the true incidence of “occult” sarcoma or cancer in a population.

These studies are provocative, however, and do inform us that, as women get older, we are apt to see a greater incidence of uterine cancer. We cannot safely assume that a postmenopausal or elderly woman with symptomatic or enlarging fibroids has “presumed benign disease”—it is cancer until proven otherwise, and we need to be looking for it preoperatively. Therefore, we need to be particularly careful with our surgical practices in this population—ie, the basis for the FDA’s recommendation to avoid morcellation in older women. And I agree with the FDA that open electromechanical morcellation generally is contraindicated in postmenopausal women. However, we need better data from large prospective studies to inform our understanding of the true incidence of undiagnosed or “occult” uterine sarcoma in women undergoing surgery for presumed benign disease. These future studies are likely to demonstrate what we already know—that in young, well-screened, well-selected candidates for minimally invasive hysterectomy or myomectomy, the risk of occult cancer is going to be exceptionally low.

OBG Management: Which is greater—the risks or benefits of tissue extraction?

Dr. Fader: Assessment of risks and benefits in medicine has everything to do with the intervention in question as applied to an individual patient. At the end of the day, there are risks and benefits to every medical or surgical treatment offered to patients in every medical and surgical discipline. But the risk of an occult uterine sarcoma is extremely low in a woman of reproductive age who has been properly selected and comprehensively evaluated for minimally invasive surgery and tissue extraction prior to surgery. And this small—though not negligible—risk must be weighed against the much higher risk of harm that may be incurred with an open abdominal procedure, compared with minimally invasive surgery.

However, in many elderly women, the risks of tissue extraction with an electromechanical morcellator may outweigh the benefits. Even so, there are exceptions in which tissue extraction may be acceptable in postmenopausal women (ie, using alternative tissue-extraction methods in those undergoing minimally invasive supracervical hysterectomy and sacral colpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse).

Few of the data published on the risks of morcellation are of very high quality in terms of scientific rigor or methodology. The best thing we can do as a gynecologic surgical community is conduct sound quality-improvement (QI) programs, disseminate our QI results, publish our data, establish guidelines for best practices in uterine tissue extraction, and collaborate readily to increase the scholarly output on this issue so that national societies and government regulatory agencies have better-quality data to inform future policy on this issue.

A case-based approach

OBG Management: How would you approach tissue extraction in the following case?

CASE: A desire for myomectomy

A 35-year-old woman (G1P1) who delivered by cesarean has an 8-cm symptomatic intramural fibroid. She has regular heavy periods that have led to anemia (hemoglobin level = 10 mg/dL). Her medical history is negative for malignancy, pelvic radiation, or tamoxifen use, and she wants to preserve her fertility. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirms an 8-cm fibroid. Endometrial biopsy results are negative.

Dr. Fader: At Johns Hopkins, as at many other centers, we use well-defined criteria to determine whether a minimally invasive approach (and tissue extraction) might be appropriate. We also individualize treatment and surgical decision-making on a case-by-case basis. Any candidate for minimally invasive surgery and tissue extraction for uterine fibroids must undergo a thorough preoperative assessment.

Johns Hopkins preoperative assessment criteria include:

- endometrial biopsy

- imaging (often MRI)

- a detailed history and physical, with a comprehensive review of risk factors for malignancy, including family and genetic history or a personal history of malignancy, pelvic radiation, tamoxifen use, or BRCA or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) deleterious mutation carrier status, among other things.

- In addition, all cases are discussed at a peer-reviewed, preoperative conference to ensure that a thorough work-up has been conducted and to verify the patient’s candidacy for a minimally invasive procedure with tissue extraction. As the FDA recommends, we conduct an enhanced informed consent process and counsel patients being considered for tissue extraction about the risk of occult sarcoma.

Our top priority is patient safety, so until more data are available, we no longer perform open electromechanical morcellation. We perform all tissue extraction within a containment system and under institutional review board protocol. We primarily perform tissue extraction via scalpel morcellation.

OBG Management: How do the patient’s wishes factor into the decision to perform minimally invasive surgery with morcellation?

Dr. Fader: Our patients make their own decisions regarding surgical approach and procedure after undergoing extensive counseling about the risks and benefits of the proposed procedures. I certainly would offer a patient like the one described in this case the opportunity for a minimally invasive approach (if, after thorough preoperative evaluation, she were deemed to be at very low risk for uterine malignancy). In my experience, most women opt for the minimally invasive approach in this setting; however, if a patient declines minimally invasive surgery, I respect her decision.

Tissue extraction in perimenopause

CASE: A desire for myomectomy at age 48

OBG Management: How would you approach the same case if the patient were a 48-year-old perimenopausal woman?

Dr. Fader: In perimenopausal women, we are more selective about performing morcellation, given the recent FDA safety statement, and because the incidence of occult cancer starts to increase slightly in this patient cohort (although it doesn’t precipitously increase until well into the postmenopausal period).

In addition, myomectomy may have less value in a 48-year-old, given the lower likelihood of achieving successful fertility, although there are exceptions. US cancer statistics and studies on morcellation demonstrate that the vast majority of women in their 30s and 40s have an extremely low risk for sarcomas and other uterine malignancies.2

In select cases in which a woman has undergone a comprehensive preoperative work-up, has a stable-appearing fibroid(s), and is well-educated and counseled about the pros and cons of morcellation, we would consider performing a procedure with contained tissue extraction. As a general matter, however, I would be more inclined to offer a 48-year-old in this situation a uterine artery embolization or minimally invasive hysterectomy than a myomectomy procedure, especially given the recent study by Wright and colleagues demonstrating the significantly increased risks of uterine cancer at myomectomy surgery for a woman in her late 40s or early 50s.18

Preoperative assessment should be comprehensive