User login

CASE: Patient opts for myomectomy

A 41-year-old woman, G0, with symptomatic myomas wishes to preserve her reproductive organs rather than undergo hysterectomy. She chooses laparoscopic myomectomy.

Preoperative imaging with transvaginal ultrasound reveals a 4-cm posterior pedunculated myoma and a 5-cm fundal intramural myoma. Preoperative videohysteroscopy reveals external compression of the anterior intramural myoma without intracavitary extension. Both tubal ostia appear normal.

During a multipuncture technique with a 5-mm laparoscope and 5-mm accessory ports,1 the abdomen and pelvis are evaluated. The 4-cm pedunculated myoma is visualized posteriorly and to the left of midline. The 5-cm intramural myoma enlarges the contour of the uterine fundus.

How would you proceed?

With intracorporeal electromechanical “power” morcellation under scrutiny due to the potential dissemination of benign and malignant tissue, many surgeons are seeking alternatives that will allow them to continue offering minimally invasive surgical options.2–4

Intracorporeal power morcellation is used during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures, including total hysterectomy, supracervical hysterectomy, and myomectomy. Two current alternatives—laparoscopic-assisted minilaparotomy and tissue extraction through a posterior colpotomy—show promise in minimizing the risks of tissue dissemination.5–7 Regardless of the route selected for tissue extraction, the use of endoscopic specimen bags and surgical retractors may ease tissue removal and limit dissemination.

In this article, we describe contained transvaginal tissue extraction through a posterior colpotomy in the setting of laparoscopic myomectomy, describing an actual case. A video of our technique is available at obgmanagement.com.

Technique, tips, and tricks

Posterior colpotomy allows the removal of fibroids during laparoscopic myomectomy without the need to enlarge the abdominal incisions and without the use of intracorporeal power morcellation. Instead, tissue is extracted transvaginally. The incision is hidden in a natural orifice, the vagina.

Equipment consists of a:

- 5-mm laparoscope and 5-mm accessory ports

- LapSac specimen-retrieval bag (Cook Medical; various sizes available)

- AirSeal Access Port (SurgiQuest), 12 mm in diameter and 150 mm in length (FIGURE 1).

Figure 1: Equipment

The AirSeal Access Port (Top) and LapSac specimen-retrieval bag (Bottom). |

Preparatory steps Place a manipulator in the uterus and elevate it anteriorly. Position the AirSeal Access Port transvaginally, with the sharp tip below the cervix in the posterior fornix. Take care not to injure the rectum.

Confirm proper placement of the Access Port and visualize the posterior cul-de-sac laparoscopically.

Insert the 12-mm Access Port for pneumoperitoneum and the introduction and removal of suture, curved needles, and the specimen-retrieval bag.

The Access Port also provides excellent smoke evacuation and optimal visualization during the myomectomy. It is a new-concept laparoscopic port without any mechanical seal. The technology assists in maintaining pneumoperitoneum at a constant pressure despite the size of the opening.

Amputating the myomas

Choose a specimen-retrieval bag just slightly larger than the largest myoma. In this case, the larger of the two myomas is approximately 5 cm. Therefore, a 5 × 8 cm LapSac is appropriate. We roll up the LapSac and place it through the Access Port using smooth forceps, situating the bag in the abdomen prior to the start of the myomectomy, with the opening toward the uterus, so that the myomas can be collected as they are removed (FIGURE 2).

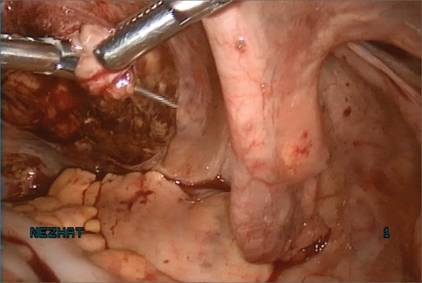

We then inject dilute vasopressin (one 20-unit ampule in 60 cc normal saline) near the base of the pedunculated myoma stalk and use monopolar electrosurgery to amputate the myoma. We place the myoma in the specimen-retrieval bag (FIGURE 3).

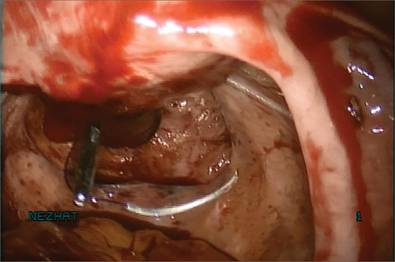

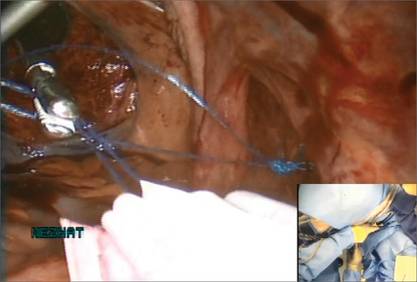

Next, we inject dilute vasopressin into the serosa overlying the intramural myoma and use electrosurgery to incise the serosa and myometrium. We enucleate the second myoma and place it in the bag. We then close the uterine incision using a combination of interrupted Vicryl and running V-Loc sutures on a curved CT-2 needle introduced through the Access Port (FIGURE 4).

Figure 2: Introduce the bag

Introduce the LapSac through the Access Port. Figure 3: Contain the specimen

| Figure 4: Close the uterine incision

In preparation for closure, insert a curved CT-2 needle and suture material through the Access Port. Figure 5: Cinch the sac

|

Tissue extraction

We place a blunt-tipped grasper transvaginally through the 12-mm Access Port to retrieve the blue polypropylene drawstring of the specimen bag (FIGURE 5). We then deactivate the Access Port and AirSeal system.

The bag containing the myomas is too large to fit through the port and the posterior colpotomy, so it is necessary to remove the Access Port from the vagina without losing the drawstrings of the specimen bag (FIGURE 6).

We vaginally exteriorize the opening of the bag (FIGURE 7), reorient the pedunculated myoma, which is oblong in shape, using forceps, and remove it without morcellation.

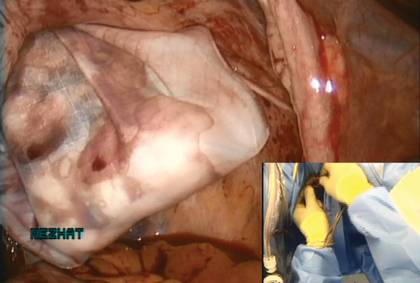

Manual morcellation will be necessary for the second, larger myoma. We perform that morcellation sharply using a scalpel within the specimen retrieval bag, taking care not to puncture the bag (FIGURE 8). When the myoma pieces are small enough, we remove them, along with the bag, through the posterior colpotomy. We then close the colpotomy laparoscopically using two interrupted 0 Vicryl sutures, and we copiously irrigate the pelvis (FIGURE 9).

Figure 6: Remove the Access Port

Prior to tissue extraction, remove the Access Port from the vagina. Figure 7: Exteriorize the bag

| Figure 8: Contain the morcellation

Manually morcellate the specimen within the bag and remove it transvaginally. Figure 9: Close the colpotomy

|

Benefits of this approach

The greatest benefit of this technique is the safe removal of specimens when performing fertility-sparing surgery. The 5-mm incisions are cosmetically inconspicuous. Moreover, the risk of port-site hernia is lower with 5-mm incisions, as opposed to extended incisions to remove specimens transabdominally.

The posterior colpotomy is associated with reduced pain and does not increase the rate of dyspareunia or infection; it also helps prevent pelvic adhesions.8–11

In 1993, we reported the results of second-look laparoscopy in 22 women who had undergone laparoscopic posterior colpotomy for tissue extraction. None had obliterative adhesions in the posterior cul-de-sac.11 This advantage is especially important in fertility-sparing surgery.

We have used this approach for specimen removal after several different procedures, including laparoscopic cystectomy and appendectomy.12,13 For laparoscopic cystectomy, once the cyst is drained, we enucleate it and place the cyst capsule into a specimen bag that has been inserted transvaginally through a posterior colpotomy.12 Laparoscopic appendectomy can be performed using a 12-mm stapler introduced via the colpotomy. We simply remove the specimen in its entirety through the posterior colpotomy.13

The bottom line: Gynecologic surgeons need to continue performing minimally invasive surgery for the benefit of patients. Moving forward and innovating to develop alternatives to intracorporeal power morcellation, when possible, should be our aim rather than falling back on surgeries through large abdominal incisions.

CASE: Resolved

At her 1-week postoperative visit, the patient’s 5-mm incisions are healing well and she has minimal pain.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. King LP, Nezhat C, Nezhat F, et al. Laparoscopic access. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, eds. Nezhat’s Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013:41–53.

2. Kho KA, Nezhat CH. Evaluating the risks of electric uterine morcellation. JAMA. 2014;311(9):905–906.

3. Kho KA, Anderson TL, Nezhat CH. Intracorporeal electromechanical tissue morcellation: a critical review and recommendations for clinical practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):787–793.

4. Kho K, Nezhat CH. Parasitic myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):611–615.

5. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Bess O, Nezhat CH, Mashiach R. Laparoscopically assisted myomectomy: a report of a new technique in 57 cases. Int J Fertil. 1994;39(1):39–44.

6. Seidman DS, Nezhat CH, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. The role of laparoscopic-assisted myomectomy (LAM). JSLS. 2001;5(4):299–303.

7. Kho KA, Shin JH, Nezhat C. Vaginal extraction of large uteri with the Alexis retractor. JMIG. 2009;16(5):616–617.

8. Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Uccella S, Bogani G, Serati M, Bolis P. Transumbilical versus transvaginal retrieval of surgical specimens at laparoscopy: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(2):112.e1–e6.

9. Ghezzi F, Raio L, Mueller MD, Gyr T, Buttarelli M, Franchi M. Vaginal extraction of pelvic masses following operative laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(12):1691–1696.

10. Guarner-Argente C, Beltrán M, Martínez-Pallí G, et al. Infection during natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery peritoneoscopy: a randomized comparative study in a survival porcine model. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(6):741–746.

11. Nezhat F, Brill AI, Nezhat CH, Nezhat C. Adhesion formation after endoscopic posterior colpotomy. J Reprod Med. 1993;38(7):534–536.

12. Nezhat CH. Laparoscopic large ovarian cystectomy and removal through a natural orifice in a 16-year-old female. Video presented at: 21st Annual Meeting of the Society of Laparoscopic Surgeons; September 5–8, 2012; Boston, Massachusetts.

13. Nezhat CH, Datta MS, DeFazio A, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Natural orifice-assisted laparoscopic appendectomy. JSLS. 2009;13(1):14–18.

CASE: Patient opts for myomectomy

A 41-year-old woman, G0, with symptomatic myomas wishes to preserve her reproductive organs rather than undergo hysterectomy. She chooses laparoscopic myomectomy.

Preoperative imaging with transvaginal ultrasound reveals a 4-cm posterior pedunculated myoma and a 5-cm fundal intramural myoma. Preoperative videohysteroscopy reveals external compression of the anterior intramural myoma without intracavitary extension. Both tubal ostia appear normal.

During a multipuncture technique with a 5-mm laparoscope and 5-mm accessory ports,1 the abdomen and pelvis are evaluated. The 4-cm pedunculated myoma is visualized posteriorly and to the left of midline. The 5-cm intramural myoma enlarges the contour of the uterine fundus.

How would you proceed?

With intracorporeal electromechanical “power” morcellation under scrutiny due to the potential dissemination of benign and malignant tissue, many surgeons are seeking alternatives that will allow them to continue offering minimally invasive surgical options.2–4

Intracorporeal power morcellation is used during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures, including total hysterectomy, supracervical hysterectomy, and myomectomy. Two current alternatives—laparoscopic-assisted minilaparotomy and tissue extraction through a posterior colpotomy—show promise in minimizing the risks of tissue dissemination.5–7 Regardless of the route selected for tissue extraction, the use of endoscopic specimen bags and surgical retractors may ease tissue removal and limit dissemination.

In this article, we describe contained transvaginal tissue extraction through a posterior colpotomy in the setting of laparoscopic myomectomy, describing an actual case. A video of our technique is available at obgmanagement.com.

Technique, tips, and tricks

Posterior colpotomy allows the removal of fibroids during laparoscopic myomectomy without the need to enlarge the abdominal incisions and without the use of intracorporeal power morcellation. Instead, tissue is extracted transvaginally. The incision is hidden in a natural orifice, the vagina.

Equipment consists of a:

- 5-mm laparoscope and 5-mm accessory ports

- LapSac specimen-retrieval bag (Cook Medical; various sizes available)

- AirSeal Access Port (SurgiQuest), 12 mm in diameter and 150 mm in length (FIGURE 1).

Figure 1: Equipment

The AirSeal Access Port (Top) and LapSac specimen-retrieval bag (Bottom). |

Preparatory steps Place a manipulator in the uterus and elevate it anteriorly. Position the AirSeal Access Port transvaginally, with the sharp tip below the cervix in the posterior fornix. Take care not to injure the rectum.

Confirm proper placement of the Access Port and visualize the posterior cul-de-sac laparoscopically.

Insert the 12-mm Access Port for pneumoperitoneum and the introduction and removal of suture, curved needles, and the specimen-retrieval bag.

The Access Port also provides excellent smoke evacuation and optimal visualization during the myomectomy. It is a new-concept laparoscopic port without any mechanical seal. The technology assists in maintaining pneumoperitoneum at a constant pressure despite the size of the opening.

Amputating the myomas

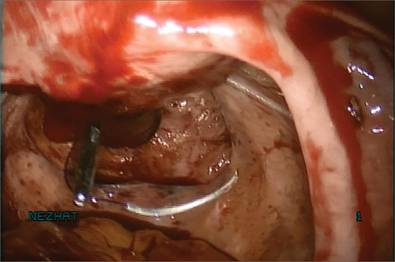

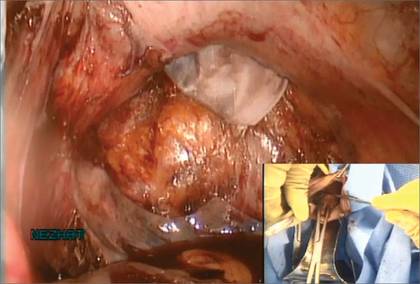

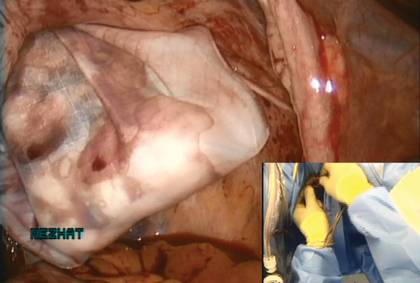

Choose a specimen-retrieval bag just slightly larger than the largest myoma. In this case, the larger of the two myomas is approximately 5 cm. Therefore, a 5 × 8 cm LapSac is appropriate. We roll up the LapSac and place it through the Access Port using smooth forceps, situating the bag in the abdomen prior to the start of the myomectomy, with the opening toward the uterus, so that the myomas can be collected as they are removed (FIGURE 2).

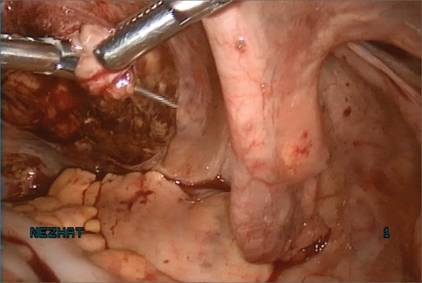

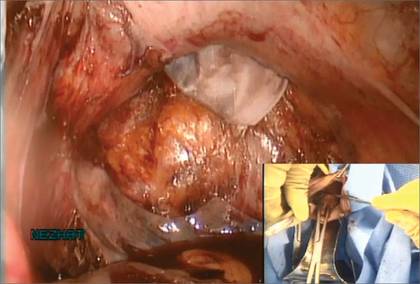

We then inject dilute vasopressin (one 20-unit ampule in 60 cc normal saline) near the base of the pedunculated myoma stalk and use monopolar electrosurgery to amputate the myoma. We place the myoma in the specimen-retrieval bag (FIGURE 3).

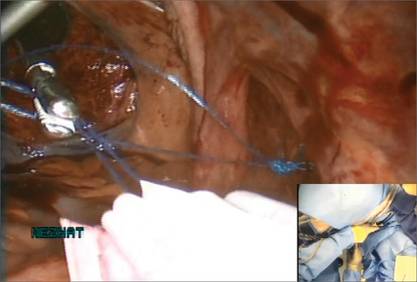

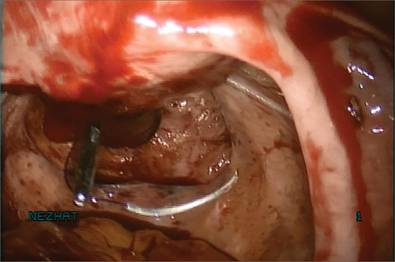

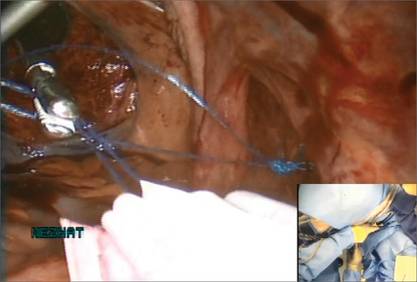

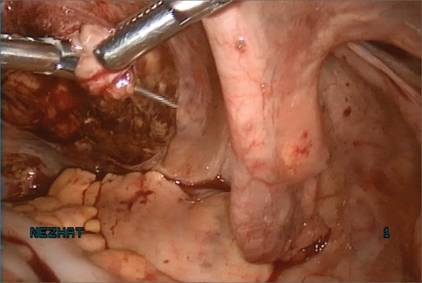

Next, we inject dilute vasopressin into the serosa overlying the intramural myoma and use electrosurgery to incise the serosa and myometrium. We enucleate the second myoma and place it in the bag. We then close the uterine incision using a combination of interrupted Vicryl and running V-Loc sutures on a curved CT-2 needle introduced through the Access Port (FIGURE 4).

Figure 2: Introduce the bag

Introduce the LapSac through the Access Port. Figure 3: Contain the specimen

| Figure 4: Close the uterine incision

In preparation for closure, insert a curved CT-2 needle and suture material through the Access Port. Figure 5: Cinch the sac

|

Tissue extraction

We place a blunt-tipped grasper transvaginally through the 12-mm Access Port to retrieve the blue polypropylene drawstring of the specimen bag (FIGURE 5). We then deactivate the Access Port and AirSeal system.

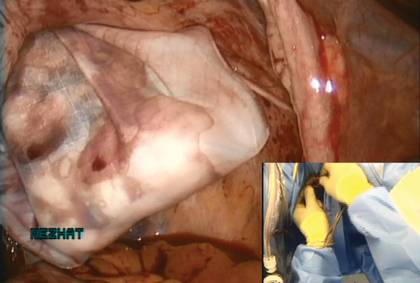

The bag containing the myomas is too large to fit through the port and the posterior colpotomy, so it is necessary to remove the Access Port from the vagina without losing the drawstrings of the specimen bag (FIGURE 6).

We vaginally exteriorize the opening of the bag (FIGURE 7), reorient the pedunculated myoma, which is oblong in shape, using forceps, and remove it without morcellation.

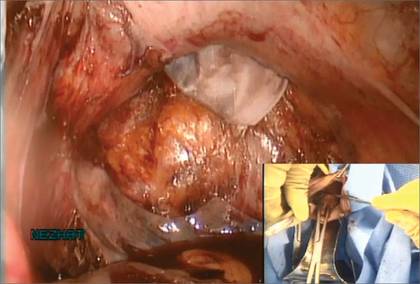

Manual morcellation will be necessary for the second, larger myoma. We perform that morcellation sharply using a scalpel within the specimen retrieval bag, taking care not to puncture the bag (FIGURE 8). When the myoma pieces are small enough, we remove them, along with the bag, through the posterior colpotomy. We then close the colpotomy laparoscopically using two interrupted 0 Vicryl sutures, and we copiously irrigate the pelvis (FIGURE 9).

Figure 6: Remove the Access Port

Prior to tissue extraction, remove the Access Port from the vagina. Figure 7: Exteriorize the bag

| Figure 8: Contain the morcellation

Manually morcellate the specimen within the bag and remove it transvaginally. Figure 9: Close the colpotomy

|

Benefits of this approach

The greatest benefit of this technique is the safe removal of specimens when performing fertility-sparing surgery. The 5-mm incisions are cosmetically inconspicuous. Moreover, the risk of port-site hernia is lower with 5-mm incisions, as opposed to extended incisions to remove specimens transabdominally.

The posterior colpotomy is associated with reduced pain and does not increase the rate of dyspareunia or infection; it also helps prevent pelvic adhesions.8–11

In 1993, we reported the results of second-look laparoscopy in 22 women who had undergone laparoscopic posterior colpotomy for tissue extraction. None had obliterative adhesions in the posterior cul-de-sac.11 This advantage is especially important in fertility-sparing surgery.

We have used this approach for specimen removal after several different procedures, including laparoscopic cystectomy and appendectomy.12,13 For laparoscopic cystectomy, once the cyst is drained, we enucleate it and place the cyst capsule into a specimen bag that has been inserted transvaginally through a posterior colpotomy.12 Laparoscopic appendectomy can be performed using a 12-mm stapler introduced via the colpotomy. We simply remove the specimen in its entirety through the posterior colpotomy.13

The bottom line: Gynecologic surgeons need to continue performing minimally invasive surgery for the benefit of patients. Moving forward and innovating to develop alternatives to intracorporeal power morcellation, when possible, should be our aim rather than falling back on surgeries through large abdominal incisions.

CASE: Resolved

At her 1-week postoperative visit, the patient’s 5-mm incisions are healing well and she has minimal pain.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE: Patient opts for myomectomy

A 41-year-old woman, G0, with symptomatic myomas wishes to preserve her reproductive organs rather than undergo hysterectomy. She chooses laparoscopic myomectomy.

Preoperative imaging with transvaginal ultrasound reveals a 4-cm posterior pedunculated myoma and a 5-cm fundal intramural myoma. Preoperative videohysteroscopy reveals external compression of the anterior intramural myoma without intracavitary extension. Both tubal ostia appear normal.

During a multipuncture technique with a 5-mm laparoscope and 5-mm accessory ports,1 the abdomen and pelvis are evaluated. The 4-cm pedunculated myoma is visualized posteriorly and to the left of midline. The 5-cm intramural myoma enlarges the contour of the uterine fundus.

How would you proceed?

With intracorporeal electromechanical “power” morcellation under scrutiny due to the potential dissemination of benign and malignant tissue, many surgeons are seeking alternatives that will allow them to continue offering minimally invasive surgical options.2–4

Intracorporeal power morcellation is used during minimally invasive gynecologic procedures, including total hysterectomy, supracervical hysterectomy, and myomectomy. Two current alternatives—laparoscopic-assisted minilaparotomy and tissue extraction through a posterior colpotomy—show promise in minimizing the risks of tissue dissemination.5–7 Regardless of the route selected for tissue extraction, the use of endoscopic specimen bags and surgical retractors may ease tissue removal and limit dissemination.

In this article, we describe contained transvaginal tissue extraction through a posterior colpotomy in the setting of laparoscopic myomectomy, describing an actual case. A video of our technique is available at obgmanagement.com.

Technique, tips, and tricks

Posterior colpotomy allows the removal of fibroids during laparoscopic myomectomy without the need to enlarge the abdominal incisions and without the use of intracorporeal power morcellation. Instead, tissue is extracted transvaginally. The incision is hidden in a natural orifice, the vagina.

Equipment consists of a:

- 5-mm laparoscope and 5-mm accessory ports

- LapSac specimen-retrieval bag (Cook Medical; various sizes available)

- AirSeal Access Port (SurgiQuest), 12 mm in diameter and 150 mm in length (FIGURE 1).

Figure 1: Equipment

The AirSeal Access Port (Top) and LapSac specimen-retrieval bag (Bottom). |

Preparatory steps Place a manipulator in the uterus and elevate it anteriorly. Position the AirSeal Access Port transvaginally, with the sharp tip below the cervix in the posterior fornix. Take care not to injure the rectum.

Confirm proper placement of the Access Port and visualize the posterior cul-de-sac laparoscopically.

Insert the 12-mm Access Port for pneumoperitoneum and the introduction and removal of suture, curved needles, and the specimen-retrieval bag.

The Access Port also provides excellent smoke evacuation and optimal visualization during the myomectomy. It is a new-concept laparoscopic port without any mechanical seal. The technology assists in maintaining pneumoperitoneum at a constant pressure despite the size of the opening.

Amputating the myomas

Choose a specimen-retrieval bag just slightly larger than the largest myoma. In this case, the larger of the two myomas is approximately 5 cm. Therefore, a 5 × 8 cm LapSac is appropriate. We roll up the LapSac and place it through the Access Port using smooth forceps, situating the bag in the abdomen prior to the start of the myomectomy, with the opening toward the uterus, so that the myomas can be collected as they are removed (FIGURE 2).

We then inject dilute vasopressin (one 20-unit ampule in 60 cc normal saline) near the base of the pedunculated myoma stalk and use monopolar electrosurgery to amputate the myoma. We place the myoma in the specimen-retrieval bag (FIGURE 3).

Next, we inject dilute vasopressin into the serosa overlying the intramural myoma and use electrosurgery to incise the serosa and myometrium. We enucleate the second myoma and place it in the bag. We then close the uterine incision using a combination of interrupted Vicryl and running V-Loc sutures on a curved CT-2 needle introduced through the Access Port (FIGURE 4).

Figure 2: Introduce the bag

Introduce the LapSac through the Access Port. Figure 3: Contain the specimen

| Figure 4: Close the uterine incision

In preparation for closure, insert a curved CT-2 needle and suture material through the Access Port. Figure 5: Cinch the sac

|

Tissue extraction

We place a blunt-tipped grasper transvaginally through the 12-mm Access Port to retrieve the blue polypropylene drawstring of the specimen bag (FIGURE 5). We then deactivate the Access Port and AirSeal system.

The bag containing the myomas is too large to fit through the port and the posterior colpotomy, so it is necessary to remove the Access Port from the vagina without losing the drawstrings of the specimen bag (FIGURE 6).

We vaginally exteriorize the opening of the bag (FIGURE 7), reorient the pedunculated myoma, which is oblong in shape, using forceps, and remove it without morcellation.

Manual morcellation will be necessary for the second, larger myoma. We perform that morcellation sharply using a scalpel within the specimen retrieval bag, taking care not to puncture the bag (FIGURE 8). When the myoma pieces are small enough, we remove them, along with the bag, through the posterior colpotomy. We then close the colpotomy laparoscopically using two interrupted 0 Vicryl sutures, and we copiously irrigate the pelvis (FIGURE 9).

Figure 6: Remove the Access Port

Prior to tissue extraction, remove the Access Port from the vagina. Figure 7: Exteriorize the bag

| Figure 8: Contain the morcellation

Manually morcellate the specimen within the bag and remove it transvaginally. Figure 9: Close the colpotomy

|

Benefits of this approach

The greatest benefit of this technique is the safe removal of specimens when performing fertility-sparing surgery. The 5-mm incisions are cosmetically inconspicuous. Moreover, the risk of port-site hernia is lower with 5-mm incisions, as opposed to extended incisions to remove specimens transabdominally.

The posterior colpotomy is associated with reduced pain and does not increase the rate of dyspareunia or infection; it also helps prevent pelvic adhesions.8–11

In 1993, we reported the results of second-look laparoscopy in 22 women who had undergone laparoscopic posterior colpotomy for tissue extraction. None had obliterative adhesions in the posterior cul-de-sac.11 This advantage is especially important in fertility-sparing surgery.

We have used this approach for specimen removal after several different procedures, including laparoscopic cystectomy and appendectomy.12,13 For laparoscopic cystectomy, once the cyst is drained, we enucleate it and place the cyst capsule into a specimen bag that has been inserted transvaginally through a posterior colpotomy.12 Laparoscopic appendectomy can be performed using a 12-mm stapler introduced via the colpotomy. We simply remove the specimen in its entirety through the posterior colpotomy.13

The bottom line: Gynecologic surgeons need to continue performing minimally invasive surgery for the benefit of patients. Moving forward and innovating to develop alternatives to intracorporeal power morcellation, when possible, should be our aim rather than falling back on surgeries through large abdominal incisions.

CASE: Resolved

At her 1-week postoperative visit, the patient’s 5-mm incisions are healing well and she has minimal pain.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. King LP, Nezhat C, Nezhat F, et al. Laparoscopic access. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, eds. Nezhat’s Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013:41–53.

2. Kho KA, Nezhat CH. Evaluating the risks of electric uterine morcellation. JAMA. 2014;311(9):905–906.

3. Kho KA, Anderson TL, Nezhat CH. Intracorporeal electromechanical tissue morcellation: a critical review and recommendations for clinical practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):787–793.

4. Kho K, Nezhat CH. Parasitic myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):611–615.

5. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Bess O, Nezhat CH, Mashiach R. Laparoscopically assisted myomectomy: a report of a new technique in 57 cases. Int J Fertil. 1994;39(1):39–44.

6. Seidman DS, Nezhat CH, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. The role of laparoscopic-assisted myomectomy (LAM). JSLS. 2001;5(4):299–303.

7. Kho KA, Shin JH, Nezhat C. Vaginal extraction of large uteri with the Alexis retractor. JMIG. 2009;16(5):616–617.

8. Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Uccella S, Bogani G, Serati M, Bolis P. Transumbilical versus transvaginal retrieval of surgical specimens at laparoscopy: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(2):112.e1–e6.

9. Ghezzi F, Raio L, Mueller MD, Gyr T, Buttarelli M, Franchi M. Vaginal extraction of pelvic masses following operative laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(12):1691–1696.

10. Guarner-Argente C, Beltrán M, Martínez-Pallí G, et al. Infection during natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery peritoneoscopy: a randomized comparative study in a survival porcine model. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(6):741–746.

11. Nezhat F, Brill AI, Nezhat CH, Nezhat C. Adhesion formation after endoscopic posterior colpotomy. J Reprod Med. 1993;38(7):534–536.

12. Nezhat CH. Laparoscopic large ovarian cystectomy and removal through a natural orifice in a 16-year-old female. Video presented at: 21st Annual Meeting of the Society of Laparoscopic Surgeons; September 5–8, 2012; Boston, Massachusetts.

13. Nezhat CH, Datta MS, DeFazio A, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Natural orifice-assisted laparoscopic appendectomy. JSLS. 2009;13(1):14–18.

1. King LP, Nezhat C, Nezhat F, et al. Laparoscopic access. In: Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat CH, eds. Nezhat’s Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopy and Hysteroscopy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013:41–53.

2. Kho KA, Nezhat CH. Evaluating the risks of electric uterine morcellation. JAMA. 2014;311(9):905–906.

3. Kho KA, Anderson TL, Nezhat CH. Intracorporeal electromechanical tissue morcellation: a critical review and recommendations for clinical practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):787–793.

4. Kho K, Nezhat CH. Parasitic myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):611–615.

5. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Bess O, Nezhat CH, Mashiach R. Laparoscopically assisted myomectomy: a report of a new technique in 57 cases. Int J Fertil. 1994;39(1):39–44.

6. Seidman DS, Nezhat CH, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. The role of laparoscopic-assisted myomectomy (LAM). JSLS. 2001;5(4):299–303.

7. Kho KA, Shin JH, Nezhat C. Vaginal extraction of large uteri with the Alexis retractor. JMIG. 2009;16(5):616–617.

8. Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Uccella S, Bogani G, Serati M, Bolis P. Transumbilical versus transvaginal retrieval of surgical specimens at laparoscopy: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(2):112.e1–e6.

9. Ghezzi F, Raio L, Mueller MD, Gyr T, Buttarelli M, Franchi M. Vaginal extraction of pelvic masses following operative laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(12):1691–1696.

10. Guarner-Argente C, Beltrán M, Martínez-Pallí G, et al. Infection during natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery peritoneoscopy: a randomized comparative study in a survival porcine model. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(6):741–746.

11. Nezhat F, Brill AI, Nezhat CH, Nezhat C. Adhesion formation after endoscopic posterior colpotomy. J Reprod Med. 1993;38(7):534–536.

12. Nezhat CH. Laparoscopic large ovarian cystectomy and removal through a natural orifice in a 16-year-old female. Video presented at: 21st Annual Meeting of the Society of Laparoscopic Surgeons; September 5–8, 2012; Boston, Massachusetts.

13. Nezhat CH, Datta MS, DeFazio A, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Natural orifice-assisted laparoscopic appendectomy. JSLS. 2009;13(1):14–18.