User login

The perimenopausal period and the benefits of progestin IUDs

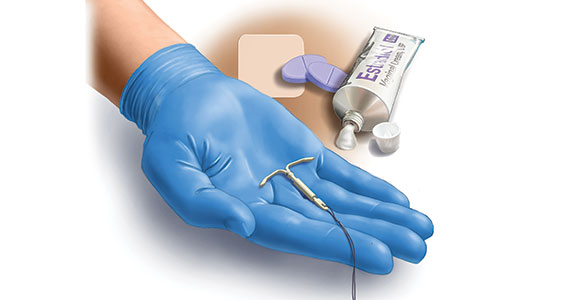

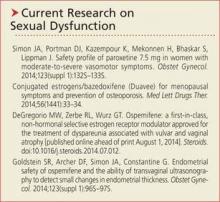

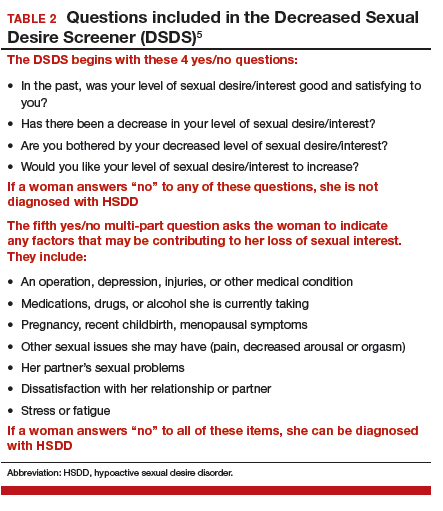

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are now used by more than 15% of US contraceptors. The majority of these IUDs release the progestin levonorgestrel, and with now longer extended use of the IUDs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA),1-3 they become even more attractive for use for contraception,control of menorrhagia or heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) during reproductive years and perimenopause, and potentially, although not FDA approved for this purpose, postmenopause for endometrial protection in estrogen users. In this roundtable discussion, we will look at some of the benefits of the IUD for contraception effectiveness and control of bleeding, as well as the potential risks if used for postmenopausal women.

Progestin IUDs and contraception

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD, NCMP: Dr. Kaunitz, what are the contraceptive benefits of progestin IUDs during perimenopause?

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, NCMP: We know fertility declines as women approach menopause. However, when pregnancy occurs in older reproductive-age women, the pregnancies are often unintended, as reflected by high rates of induced abortion in this population. In addition, the prevalence of maternal comorbidities (during pregnancy and delivery) is higher in older reproductive-age women, with the maternal mortality rate more than 5 times higher compared with that of younger women.4 Two recently published clinical trials assessed the extended use of full-size IUDs containing 52 mg of levonor-gestrel (LNG), with the brand names Mirena and Liletta.1,2 The data from these trials confirmed that both IUDs remain highly effective for up to 8 years of use, and currently, both devices are approved for up to 8 years of use. One caveat is that, in the unusual occurrence of a pregnancy being diagnosed in a woman using an IUD, we as clinicians, must be alert to the high prevalence of ectopic pregnancies in this setting.

Progestin IUDs and HMB

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Goldstein, can you comment on how well progestin IUDs work for HMB?

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, NCMP, CCD: Many women who need contraception will use these devices for suppressing HMB, and they can be quite effective, if the diagnosis truly is HMB, at reducing bleeding.5 But that efficacy in bleeding reduction may not be quite as long as the efficacy in pregnancy prevention.6 In my experience, among women using IUDs specifically for their HMB, good bleeding control may require changing the IUD at 3 to 5 years.

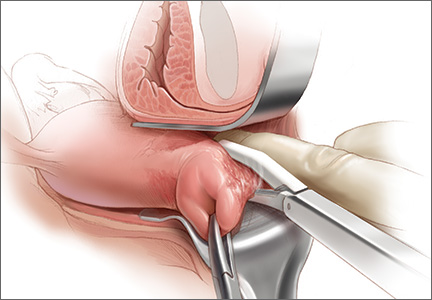

Barbara S. Levy, MD: When inserting a LNG-IUD for menorrhagia in the perimenopausal time frame, sometimes I will do a progestin withdrawal first, which will thin the endometrium and induce withdrawal bleeding because, in my experience, if you place an IUD in someone with perimenopausal bleeding, you may end up with a lot of breakthrough bleeding.

Perimenopause and hot flashes

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Kaunitz, we have learned that hot flashes often occur and become bothersome to women during perimenopause. Many women have IUDs placed during perimenopause for bleeding. Can you comment about IUD use during perimenopause and postmenopause?

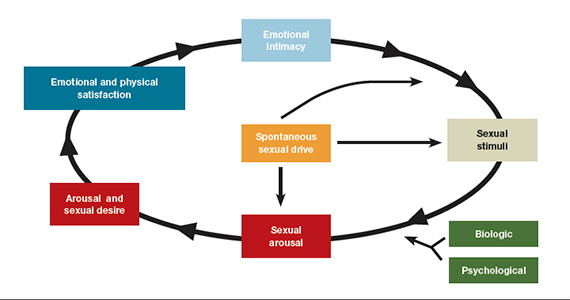

Dr. Kaunitz: In older reproductive-age women who already have a progestin-releasing IUD placed, as they get closer to menopause when vasomotor symptoms (VMS) might occur, if these symptoms are bothersome, the presence or placement of a progestin-releasing IUD can facilitate treatment of perimenopausal VMS with estrogen therapy.

Progestin IUDs cause profound endometrial suppression, reduce bleeding and often, over time, cause users to become amenorrheic.7

The Mirena package insert states, “Amenorrhea develops in about 20% of users by one year.”2 By year 3 and continuing through year 8, the prevalence of amenorrhea with the 52-mg LNG-IUD is 35% to 40%.8 From a study by Nanette Santoro, MD, and colleagues, we know that, in perimenopausal women with a progestin-releasing IUD in place, who are experiencing bothersome VMS, adding transdermal estrogen is very effective in treating and suppressing those hot flashes. In her small clinical trial, among participants with perimenopausal bothersome VMS with an IUD in place, half were randomized to use of transdermal estradiol and then compared with women who did not get the estradiol patch. There was excellent relief of perimenopausal hot flashes with the combination of the progestin IUD for endometrial suppression and transdermal estrogen to relieve hot flashes.9

Dr. Pinkerton: Which women would not be good candidates for the use of this combination?

Dr. Kaunitz: We know that, as women age, the prevalence of conditions that are contraindications to combination contraceptives (estrogen-progestin pills, patches, or rings) starts to increase. Specifically, we see more: hypertension, diabetes, and high body mass index (BMI), or obesity. We also know that migraine headaches in women older than age 35 years is another condition in which ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) would not recommend use of combination contraceptives.10,11 These older perimenopausal women may be excellent candidates for a progestin-only releasing IUD combined with use of transdermal menopausal doses of estradiol if needed for VMS.

Dr. Goldstein: I do want to add that, in those patients who don’t have these comorbidities, combination estrogen-progestin contraceptives do a very nice job of ovarian suppression and will prevent the erratic production of estradiol, which, in my experience, often results in not only irregular bleeding but also possible exacerbation of perimenopausal mood symptoms.

Dr. Kaunitz: I agree, Steve. The ideal older reproductive-age candidate for combination pills, patch, or ring would be a slender, healthy, nonsmoking woman with normal blood pressure. Such women would be a fairly small subgroup of my practice, but they can safely continue combination contraceptives right through menopause. Consistent with CDC and ACOG guidance, rather than checking gonadotropins to “determine when menopause has occurred,” (which is, in fact, not an evidence-based approach to diagnosing menopause in this setting), such women can continue the combination contraceptive right up until age 55—the likelihood that women are still going to be ovulating or at risk for pregnancy becomes vanishingly small at that age.11,12 Women in their mid-50s can either seamlessly transition to use of systemic estrogen-progestin menopausal therapy or go off hormones completely.

Continue to: The IUD and HMB...

The IUD and HMB

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Goldstein, there’s been some good literature on the best management options for women with HMB. What is the most current evidence?

Dr. Goldstein: I think that the retiring of the terms menorrhagia and metrorrhagia may have been premature because HMB implies cyclical bleeding, and this population of women with HMB will typically do quite well. Women who have what we used to call metrorrhagia or irregular bleeding, by definition, need endometrial evaluation to be sure they don’t have some sort of organic pathology. It would be a mistake for clinicians to use an LNG-IUD in patients with abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) that has not been appropriately evaluated.

If we understand that we are discussing HMB, a Cochrane Review from 202213 suggests that an LNG intrauterine system is the best first-line treatment for reducing menstrual blood loss in perimenopausal women with HMB. Antifibrinolytics appeared second best, while long-cycle progestogens came in third place. Evidence on perception of improvement in satisfaction was ranked as low certainty. That same review found that hysterectomy was the best treatment for reducing bleeding, obviously, followed by resectoscopic endometrial ablation or a nonresectoscopic global endometrial ablation.

The evidence rating was low certainty regarding the likelihood that placing an LNG-IUD in women with HMB will result in amenorrhea, and I think that’s a very important point. The expectation of patients should be reduced or a significantly reduced amount of their HMB, not necessarily amenorrhea. Certainly, minimally invasive hysterectomy will result in total amenorrhea and may have a larger increase in satisfaction, but it has its own set of other kinds of possible complications.

Dr. Kaunitz: In an industry-funded, international multicenter trial,14 women with documented HMB (hemoglobin was eluted from soiled sanitary products), with menstrual blood loss of 80 mL or more per cycle, were randomized to placement of an LNG 52-mg IUD (Mirena) or cyclical medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA)—oral progestin use.

Although menstrual blood loss declined in both groups, it declined dramatically more in women with an IUD placed, and specifically with the IUD, menstrual blood loss declined by 129 mL on average, whereas the decline in menstrual blood loss with cyclical MPA was 18 mL. This data, along with earlier European data,15 which showed similar findings in women with HMB led to the approval of the Mirena progestin IUD for a second indication to treat HMB in 2009.

I also want to point out that, in the May 2023 issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Creinin and colleagues published a similar trial in women with HMB showing, once again, that progestin IUDs (52-mg LNG-IUD, Liletta) are extremely effective in reducing HMB.16 There is crystal clear evidence from randomized trials that both 52-mg LNG-IUDs, Mirena and Liletta, are very effective in reducing HMB and, in fact, are contributing to many women who in the past would have proceeded with surgery, such as ablation or hysterectomy, to control their HMB.

Oral contraception

Dr. Pinkerton: What about using low-dose continuous oral contraceptives noncyclically for women with HMB?

Dr. Goldstein: I do that all the time. It is interesting that Dr. Kaunitz mentions his patient population. It’s why we understand that one size does not fit all. You need to see patients one at a time, and if they are good candidates for a combined estrogen-progestin contraception, whether it’s pills, patches, or rings, giving that continuously does a very nice job in reducing HMB and straightening out some of the other symptoms that these perimenopausal women will have.

IUD risks

Dr. Pinkerton: We all know about use of low-dose oral contraceptives for management of AUB, and we use them, although we worry a little bit about breast cancer risk. Dr. Levy, please comment on the risks with IUDs of expulsions and perforations. What are the downsides of IUDs?

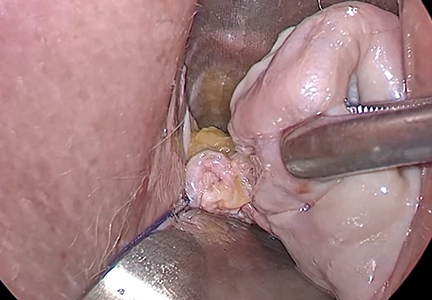

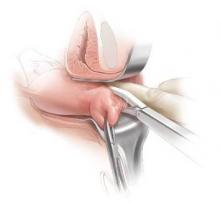

Dr. Levy: Beyond the cost, although it is a minimally invasive procedure, IUD insertion can be an invasive procedure for a patient to undergo; expulsions can occur.17 We know that a substantial percentage of perimenopausal women will have fibroids. Although many fibroids are not located in the uterine cavity, the expulsion rate with HMB for an LNG-IUD can be higher,13,16,18,19 perhaps because of local prostaglandin release with an increase in uterine contractility. There is a low incidence of perforations, but they do happen, particularly among women with scars in the uterus or who have a severely anteflexed or retroflexed uterus, and women with cervical stenosis, for example, if they have had a LEEP procedure, etc. Even though progestin IUDs are outstanding tools in our toolbox, they are invasive to some extent, and they do have the possibility of complications.

Dr. Kaunitz: As Dr. Levy points out, although placement of an IUD may be considered an invasive procedure, it is also an office-based procedure, so women can drive home or drive back to work afterwards without the disruption in their life and the potential complications associated with surgery and anesthesia.

Continue to: Concerns with malpositioning...

Concerns with malpositioning

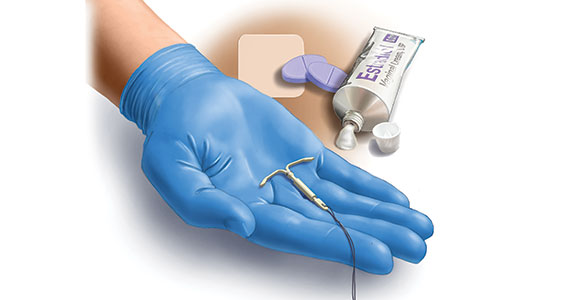

Dr. Pinkerton: After placement of an IUD, during a follow-up visit, sometimes you can’t visualize the string. The ultrasonography report may reveal, “IUD appears to be in the right place within the endometrium.” Dr. Goldstein, can you comment on how we should use ultrasound when we can’t visualize or find the IUD string, or if the patient complains of abdominal pain, lower abdominal discomfort, or irregular bleeding or spotting and we become concerned about IUD malposition?

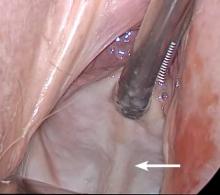

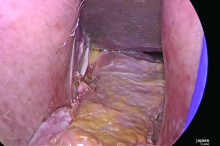

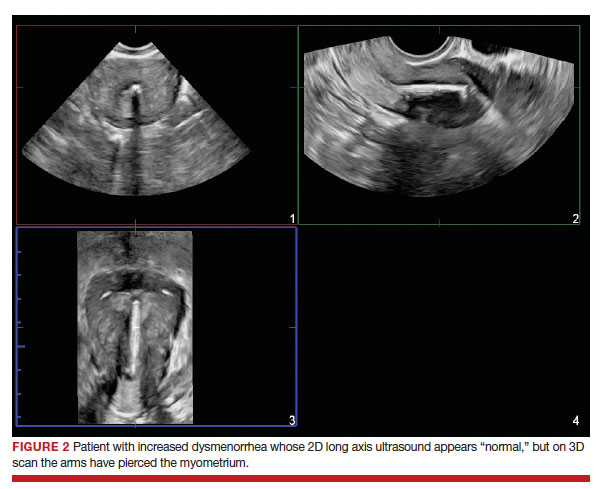

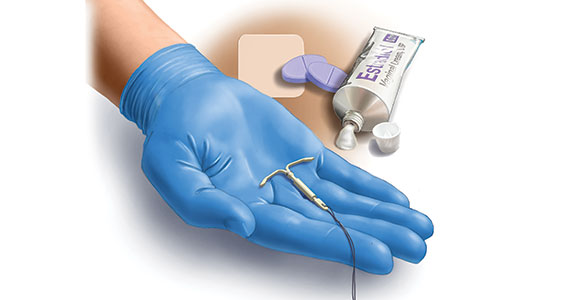

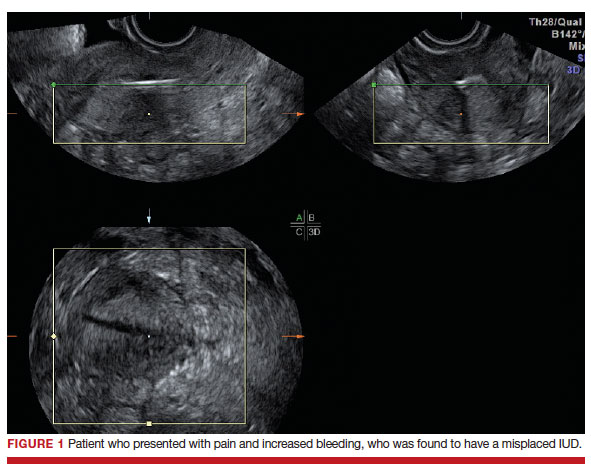

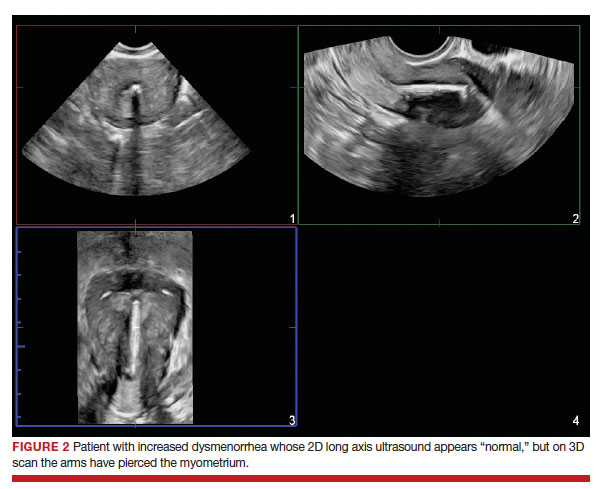

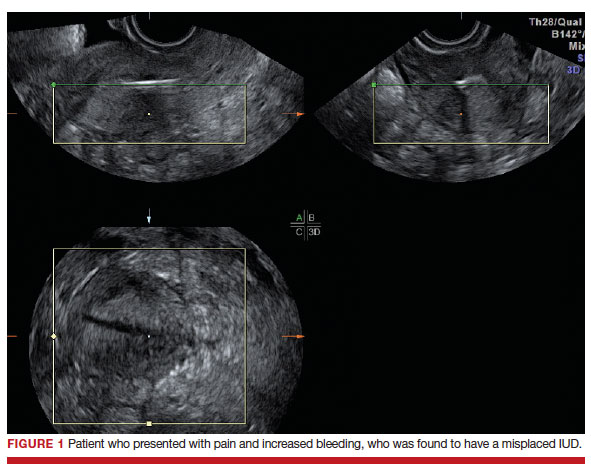

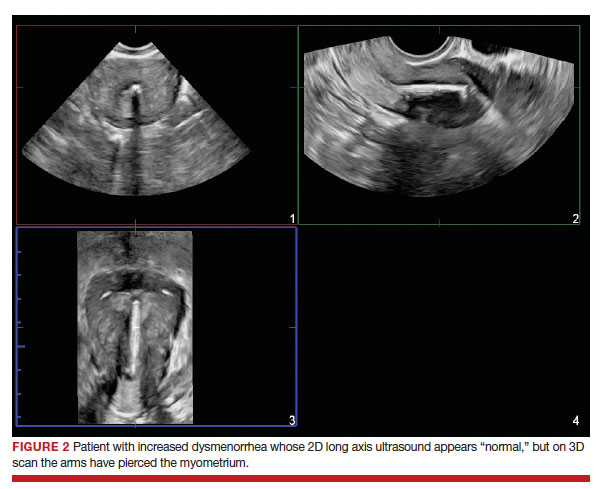

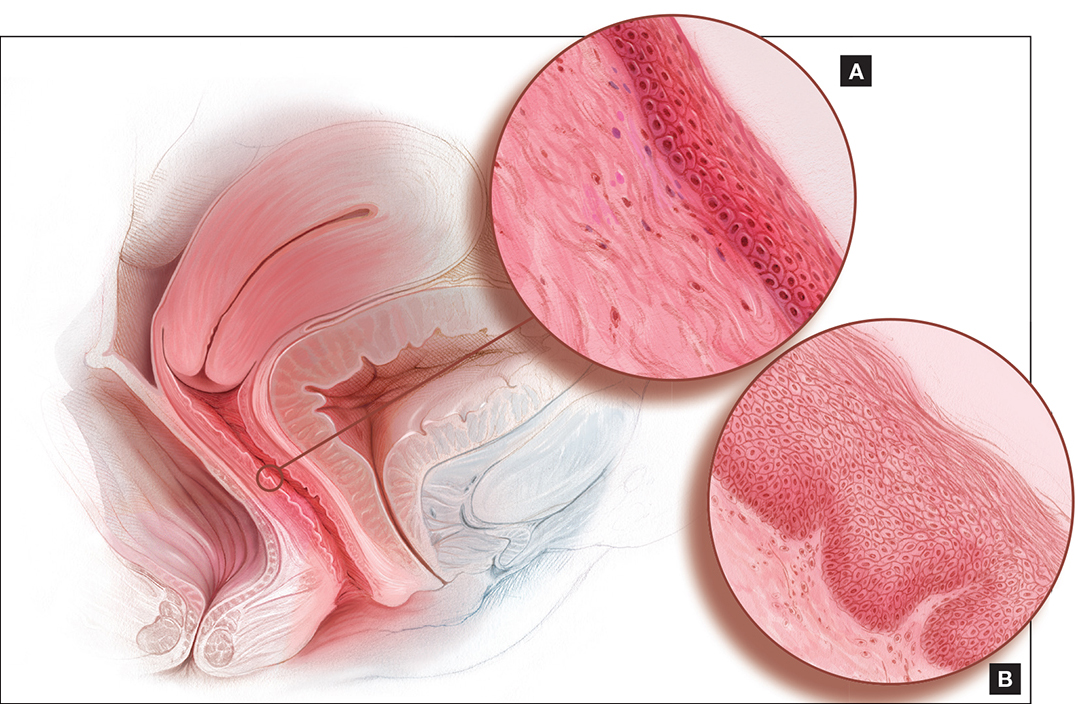

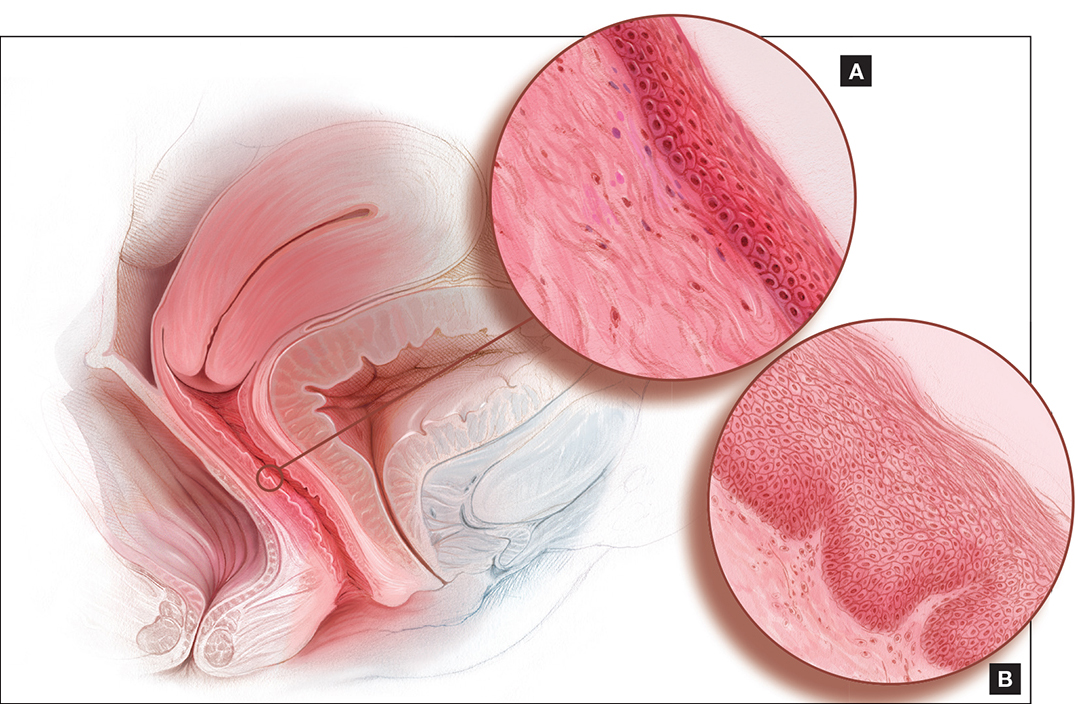

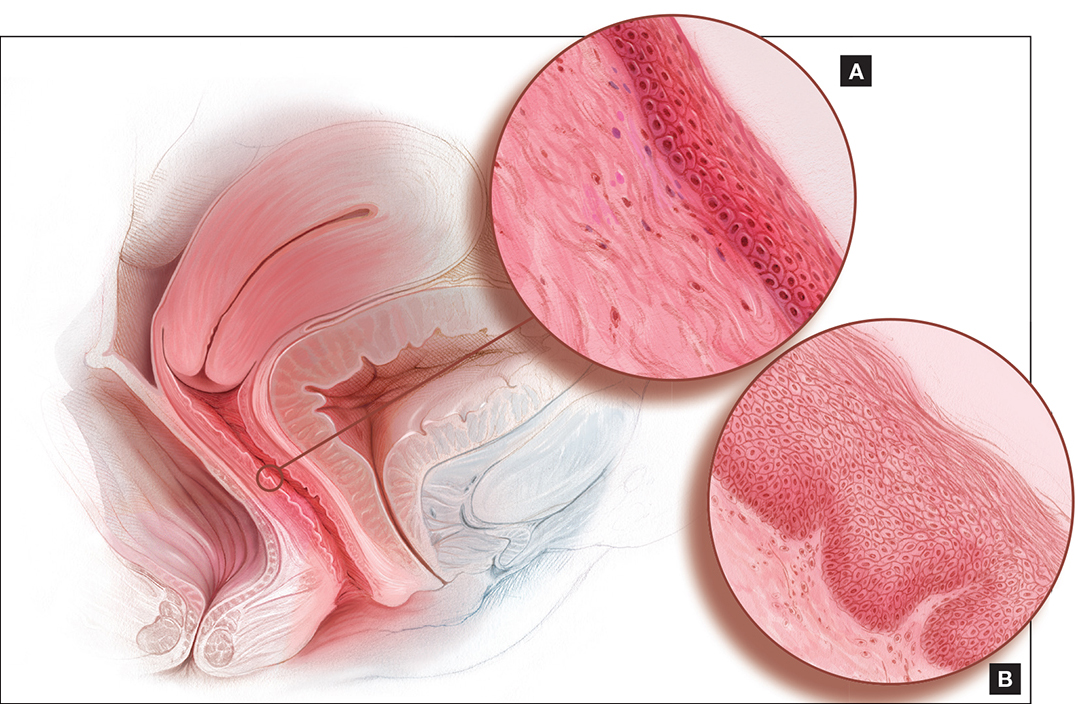

Dr. Goldstein: Ultrasound is not really required after an uncomplicated placement of an IUD or during routine management of women who have no problems who are using an IUD. In patients who present with pain or some abnormal bleeding, however, sometimes it is the IUD being malpositioned. A very interesting study by the late great Beryl Benacerraf20 showed that there was a statistically significant higher incidence of the IUD being poorly positioned when patients have pain or bleeding (FIGURE 1). It was not always apparent on 2D ultrasonography. Using a standard transvaginal ultrasound of the long access plane, the IUD may appear to be very centrally located. However, if you do a 3D coronal section, not infrequently in these patients with any pain or bleeding, one of the arms has pierced the myometrium (FIGURE 2). This can actually be a source of pain and bleeding.

It’s also very interesting when you talk about perforation. I became aware of a big to-do in the medical/legal world about the possibility of the IUD migrating through the uterine cavity.21 This just does not exist, as was already pointed out. If the IUD is really going to go anywhere, if it’s properly placed, it’s going to be expelled through an open cervix. I do believe that, if you have pierced the myometrium through uterine contractility over time, some of these IUDs could work their way through the myometrium and somehow come out of the uterus either totally or partially. I think ultrasound is invaluable in patients with pain and bleeding, but I think you need to have an ultrasound lab capable of doing a 3D coronal section.

Progestin IUDs for HT replacement: Benefits/risks

Dr. Pinkerton: Many clinicians are excited that they can use essentially estrogen alone for women who have a progestin IUD in place. What about the possible off-label use of the progestin IUD to replace oral progestogen for hormone therapy (HT)? Dr. Kaunitz, are there any studies using this for postmenopausal HT (with a reminder that the IUD is not FDA approved for this purpose)?

Dr. Kaunitz: We have data from Europe indicating that, in menopausal women using systemic estrogen, the full-size LNG 52 IUD—Mirena or Liletta—provides excellent endometrial suppression.22 Where we don’t have data is with the smaller IUDs, which would be Kyleena and Skyla, which release smaller amounts of progestin each day into the endometrial cavity.

I have a number of patients, most of them women who started use of a progestin IUD as older reproductive-age women and then started systemic estrogen for treatment of perimenopausal hot flashes and then continued the use of their IUD plus systemic estrogen in treating postmenopausal hot flashes. The IUD is very useful in this setting, but as you pointed out, Dr. Pinkerton, this does represent off-label use.

Dr. Pinkerton: I know this use does not affect plasma lipids or cardiovascular risk markers, although users seem to report that the IUD has improved their quality of life. The question comes up, what are the benefits on cancer risk for using an IUD?

Dr. Levy: It’s such a great question because, as we talk about the balance of risks and benefits for anything that we are offering to our patients, it is really important to focus on some of the benefits. For both the copper and the LNG-IUD, there is a reduction in endometrial cancer,22 as well as pretty good data with the copper IUD about a reduction in cervical cancer.23 Those data are a little bit less clear for the LNG-IUD.

Interestingly, at least one meta-analysis published in 2020 shows about a 30% reduction in ovarian cancer risk with the LNG-IUD.24 We need to focus our patients on these other benefits. They tend to focus on the risks, and, of course, the media blows up the risks, but the benefits are quite substantial beyond just reducing HMB and providing contraception.

Dr. Pinkerton: As Dr. Kaunitz said, when you use this IUD, with its primarily local uterine progestin effects, it’s more like using estrogen alone without as much systemic progestin. Recently I wrote an editorial on the benefits of estrogen alone on the risk of breast cancer, primarily based on the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) observational long-term 18-year cumulative follow-up. When estrogen alone was prescribed to women after a hysterectomy, estrogen therapy used at menopause did not increase the risk of invasive breast cancer, and was associated with decreased mortality.25 However, the nurse’s health study has suggested that longer-term use may be increased with estrogen alone.26 For women in the WHI with an intact uterus who used estrogen, oral MPA slightly increased the risk for breast cancer, and this elevated risk persisted even after discontinuation. This leads us to the question, what are the risks of breast cancer with progestin IUD use?

I recently reviewed the literature, and the answer is, it’s mixed. The FDA has put language into the package label that acknowledges a potential breast cancer risk for women who use a progestin IUD,27 and that warning states, “Women who currently have or have had breast cancer or suspect breast cancer should not use hormonal contraception because some breast cancers are hormone sensitive.” The label goes on to say, “Observational studies of the risk of breast cancer with the use of a levonorgestrel-releasing IUS don’t provide conclusive evidence of increased risk.” Thus, there is no conclusive answer as to whether there is a possible link of progestin IUDs to breast cancer.

What I tell my patients is that research is inconclusive. However, it’s unlikely for a 52-mg LNG-IUD to significantly increase a woman’s breast cancer risk, except possibly in those already at high risk from other risk factors. I tell them that breast cancer is listed in the package insert as a potential risk. I could not find any data on whether adding a low-dose estradiol patch would further increase that risk. So I counsel women about potential risk, but tell them that I don’t have any strong evidence of risk.

Continue to: Dr. Goldstein...

Dr. Goldstein: If you look in the package insert for Mirena,2 similar to Liletta, certainly the serum levels of LNG are lower than that for combination oral contraceptives. For the IUD progestins, they are not localized only to the uterus, and LNG levels range from about 150 to 200 µg/mL up to 60 months. It’s greater at 12 months, at about 180 µg/mL,at 24 months it was 192 µg/mL, and by 60 months it was 159 µg/mL. It’s important to realize that there is some systemic absorption of progestin with progestin IUDs, and it is not completely a local effect.

JoAnn, you mentioned the WHI data,25 and just to specify, it was not the estrogen-only arm, it was the conjugated equine estrogen-only arm of the WHI. I don’t think that estradiol alone increases breast cancer risk (although there are no good prospective, follow-through, 18-year study data, like the WHI), but I think readers need to understand the difference in the estrogen type.

Endometrial evaluation. My question for the panel is as follows. I agree that the use of the progestin-releasing IUD is very nice for that transition to menopause. I do believe it provides endometrial protection, but we know from other studies that, when we give continuous combined HT, about 21% to 26% of patients will experience some bleeding/staining, responding in the first 4-week cycles, and it can be as high as 9% at 1 year. If I have a patient who bleeds on continuous combined HT, I will evaluate her endometrium, usually just with a simple transvaginal ultrasound. If an IUD is in place, and the patient now begins to have some irregular bleeding, how do you evaluate her with the IUD in place?

Dr. Levy: That is a huge challenge. We know from a recent paper,28 that the endometrial thickness, while an excellent measure for Caucasian and European women, may be a poor marker for endometrial pathology in African-American women. What we thought we knew, which was, if the stripe is 4 mL or less, we can forget about it, I think in our more recent research that is not so true. So you bring up a great point, what do you do? The most reliable evaluation will be with an office hysteroscopy, where you can really look at the entire cavity and for tiny, little polyps and other things. But then we are off label because the use of hysteroscopy with an IUD in place is off label. So we are really in a conundrum.

Dr. Pinkerton: Also, if you do an endometrial biopsy, you might dislodge the IUD. If you think that you are going to take the IUD out, it may not matter if you dislodge it. I will often obtain a transvaginal ultrasound to help me figure out the next step, and maybe look at the dosing of the estrogen and progestin—but you can’t monitor an IUD with blood levels. You are in a vacuum of trying to figure out the best thing to do.

Dr. Kaunitz: One of the hats I wear here in Jacksonville is Director of GYN Ultrasound. I have a fair amount of experience doing endometrial biopsies in women with progestin IUDs in place under abdominal ultrasound guidance and keeping a close eye on the position of the IUD. In the first dozen or so such procedures I did, I was quite concerned about dislodging the IUD. It hasn’t happened yet, and it gives me some reassurance to be able to image the IUD and your endometrial suction curette inside the cavity as you are obtaining endometrial sampling. I have substantial experience now doing that, and so far, no problems. I do counsel all such women in advance that there is some chance I could dislodge their IUD.

Dr. Goldstein: In addition to dislodging the IUD, are you not concerned that, if the pathology is not global, that a blind endometrial sampling may be fraught with some error?

Dr. Kaunitz: The endometrium in women with a progestin-releasing IUD in place tends to be very well suppressed. Although one might occasionally find, for instance, a polyp in that setting, I have not run into, and I don’t expect to encounter going forward, endometrial hyperplasia or cancer in women with current use of a progestin IUD. It’s possible but unlikely.

Dr. Levy: The progestin IUD will counterbalance a type-1 endometrial cancer—an endometrial cancer related to hyperstimulation by estrogen. It will not do anything, to my knowledge, to counterbalance a type 2. I think the art of medicine is, you do the best you can with the first episode of bleeding, and if she persists in her bleeding, we have to persevere and continue to evaluate her.

Dr. Goldstein: I agree 100%.

Dr. Pinkerton: We all agree with you. That’s a really good point.

Continue to: Case examinations...

Case examinations

CASE 1 Woman with intramural fibroids

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Goldstein, you have a 48-year-old Black woman who has heavy but regular menstrual bleeding with multiple fibroids (the largest is about 4 to 5 cm, they look intramural, with some distortion of the cavity but not a submucous myoma, and the endometrial depth is 9 cm). Would you insert an IUD, and would you recommend an endometrial biopsy first?

Dr. Goldstein: I am not a huge fan of blind endometrial sampling, and I do think that we use the “biopsy” somewhat inappropriately since sampling is not a directed biopsy. This became obvious in the landmark paper by Guido et al in 1995 and was adopted by ACOG only in 2012.29 Cancers that occupy less than 50% of the endometrial surface area are often missed with such blind sampling. Thus I would not perform an endometrial biopsy first, but would rather rely on properly timed and performed transvaginal ultrasound to rule out any concurrent endometrial disease. I think a lot of patients who have HMB, not only because of their fibroids but also often just due to the surface area of their uterine cavity being increased—so essentially there is more blood volume when they bleed. However, you said that in this case the patient has regular menstrual bleeding, so I am assuming that she is still ovulatory. She may have some adenomyosis. She may have a large uterine cavity. I think she is an excellent candidate for an LNG-releasing IUD to reduce menstrual blood flow significantly. It will not necessarily give her amenorrhea, and it may give her some irregular bleeding. Then at some distant point, say in 5 or 6 months if she does have some irregular staining or bleeding, I would feel much better about the fact that nothing has developed as long as I knew that the endometrium was devoid of pathology when I started.

CASE 2 Woman with family history of breast cancer

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Levy, a 44-year-old woman has a family history of breast cancer in her mother at age 72, but she still needs contraceptionbecause of that unintended pregnancy risk in the 40s, and she wants something that is not going to increase her risk of breast cancer. What would you use, and how would you counsel her if you decided to use a progestin IUD?

Dr. Levy: The data are mixed,30-33 but whatever the risk, it is miniscule, and I would bring up the CDC Medical Eligibility Criteria.11 For a patient with a family history of breast cancer, for use of the progestin IUD, it is a 1—no contraindications. What I tend to tell my patients is, if you are worried about breast cancer, watch how much alcohol you are drinking and maintain regular exercise. There are so many preventive things that we can do to reduce risk of breast cancer when she needs contraception. If there is any increase in risk, it is so miniscule that I would very strongly recommend a progestin IUD for her.

Dr. Pinkerton: In addition, in recognizing the different densities of breast, dense breast density could lead to supplemental screening, which also could give her some reassurance that we are adequately screening for breast cancer.

CASE 3 Woman with IUD and VMS

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Kaunitz, you have a 52-year-old overweight female. She has been using a progestin IUD for 4 years, is amenorrheic, but now she is having moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms despite the IUD in place. You have talked to her about risks and benefits of HT, and she is interested in starting it. I know we talked about the studies, but I want to know what you are going to tell her. How do you counsel her about off-label use?

Dr. Kaunitz: The most important issue related to treating vasomotor symptoms in this patient is the route of systemic estrogen. Understandably, women’s biggest concern regarding the risks of systemic estrogen-progestin therapy is breast cancer. However, statistically, by far the biggest risk associated with oral estrogen-progestogen therapy, is elevated risk of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. We have seen this, with a number of studies, and the WHI made it crystal clear with risks of oral conjugated equine estrogen at the dose of 0.625 mg daily. Oral estradiol 1 mg daily is also associated with a similar elevated risk of venous thrombosis. We also know that age and BMI are both independent risk factors for thrombosis. So, for a woman in her 50s who has a BMI > 30 mg/kg2, I don’t want to further elevate her risk of thrombosis by giving her oral estrogen, whether it is estradiol or conjugated equine estrogen. This is a patient in whom I would be comfortable using transdermal (patch) estradiol, perhaps starting with a standard dose of 0.05 mg weekly or twice weekly patch, keeping in mind that 0.05 mg in the setting of transdermal estrogen refer to the daily or to the 24-hour release rate. The 1.0 mg of oral estradiol and 0.625 mg of conjugated equine estrogen refers to the mg quantity of estrogen in each tablet. This is a source of great confusion for clinicians.

If, during follow-up, the 0.05 mg estradiol patch is not sufficient to substantially reduce symptoms, we could go up, for instance, to a 0.075 mg estradiol patch. We know very clearly from a variety of observational studies, including a very large UK study,34 that in contrast with oral estrogen, transdermal estradiol is safer from the perspective of thrombosis.

Insurance coverage for IUDs

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Levy: Can you discuss IUDs and the Affordable Care Act’s requirement to cover contraceptive services?

Dr. Levy: Unfortunately, we do not know whether this benefit will continue based on a very recent finding from a judge in Texas that ruled the preventive benefits of the ACA were illegal.35 We don’t know what will happen going forward. What I will say is that, unfortunately, many insurance companies have not preserved the meaning of “cover all things,” so what we are finding is that, for example, they only have to cover one type in a class. The FDA defined 18 classes of contraceptives, and a hormonal IUD is one class, so they can decide that they are only going to cover one of the four IUDS. And then women don’t have access to the other three, some of which might be more appropriate for them than another.

The other thing very relevant to this conversation is that, if you use an ICD-10 code for menorrhagia, for HMB, it no longer lives within that ACA preventive care requirement of coverage for contraceptives, and now she is going to owe a big deductible or a copay. If you are practicing in an institution that does not allow the use of IUDs for contraception, like a Catholic institution where I used to practice, you will want to use that ICD-10 code for HMB. But if you want it offered with no out-of-pocket cost for the patient, you need to use the preventive medicine codes and the contraception code. These little nuances for us can make a huge difference for our patients.

Dr. Pinkerton: Thank you for that reminder. I want to thank our panelists, Dr. Levy, Dr. Goldstein, and Dr. Kaunitz, for providing us with such a great mix of evidence and expert opinion and also giving a benefit of their vast experience as award-winning gynecologists. Hopefully, today you have learned the benefits of the progestin IUD not only for contraception in reproductive years and perimenopause but also for treatment of HMB, and the potential benefit due to the more prolonged effectiveness of the IUDs for endometrial protection in postmenopause. This allows less progestin risk, essentially estrogen alone for postmenopausal HT. Unsolved questions remain about whether there is a risk of breast cancer with their use, but there is a clear benefit of protecting against pregnancy and endometrial cancer. ●

- Liletta [package insert]. Allergan; Irvine, California. November 2022.

- Mirena [package insert]. Bayer; Whippany, New Jersey. 2000.

- Kaunitz AM. Safe extended use of levonorgestrel 52-mg IUDs. November 11, 2022. https://www.medscape.com/ viewarticle/983680. Accessed May 8, 2023.

- Kaunitz AM. Clinical practice. Hormonal contraception in women of older reproductive age. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1262-1270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0708481.

- Tucker ME. IUD-released levonorgestrel eases heavy menstrual periods. Medscape. April 10, 2023. https://www .medscape.com/viewarticle/777406. Accessed May 2, 2023.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice; Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 450: Increasing use of contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices to reduce unintended pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1434-1438.

- Critchley HO, Wang H, Jones RL, et al. Morphological and functional features of endometrial decidualization following long-term intrauterine levonorgestrel delivery. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1218-1224. doi:10.1093/humrep/13.5.1218.

- Creinin MD, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, et al. Levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system efficacy and safety through 8 years of use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:871.e1-871.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.05.022.

- Santoro N, Teal S, Gavito C, et al. Use of a levonorgestrelcontaining intrauterine system with supplemental estrogen improves symptoms in perimenopausal women: a pilot study. Menopause. 2015;22:1301-1307. doi: 10.1097 /GME.0000000000000557.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology ACOG Practice Bulletin. The use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Number 18, July 2000. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;75:93-106. doi: 10.1016 /s0020-7292(01)00520-3.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, Berry-Bibee E, Horton LG, Zapata LB, Simmons KB, Pagano HP, Jamieson DJ, Whiteman MK. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103. doi: 10.15585 /mmwr.rr6503a1.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 206: use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions [published correction appears in: Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1288.] Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e128-e150. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000003072.

- Bofill Rodriguez M, Dias S, Jordan V, et al. Interventions for heavy menstrual bleeding; overview of Cochrane reviews and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;5:CD013180. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013180.pub2.

- Kaunitz AM, Bissonnette F, Monteiro I, et al. Levonorgestrelreleasing intrauterine system or medroxyprogesterone for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial [published correction appears in: Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:999]. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:625-632. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0b013e3181ec622b.

- Milsom I, Andersson K, Andersch B, et al. A comparison of flurbiprofen, tranexamic acid, and a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive device in the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:879883. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)90533-x.

- Creinin MD, Barnhart KT, Gawron LM, et al. Heavy menstrual bleeding treatment with a levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:971-978. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005137.

- 1Madden T. Association of age and parity with intrauterine device expulsion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014:718-726. doi:10.1097 /aog.0000000000000475.

- Kaunitz AM, Stern L, Doyle J, et al. Use of the levonorgestrelIUD in the treatment of menorrhagia: improving patient outcomes while reducing the need for surgical management. Manag Care Interface. 2007;20:47-50.

- Getahun D, Fassett MJ, Gatz J, et al. Association between menorrhagia and risk of intrauterine device-related uterine perforation and device expulsion: results from the Association of Uterine Perforation and Expulsion of Intrauterine Device study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:59.e1-59.e9.

- Benacerraf BR, Shipp TD, Bromley B. Three-dimensional ultrasound detection of abnormally located intrauterine contraceptive devices that are a source of pelvic pain and abnormal bleeding. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:110115.

- Shipp TD, Bromley B, Benacerraf BR. The width of the uterine cavity is narrower in patients with an embedded intrauterine device (IUD) compared to a normally positioned IUD. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:1453-1456.

- Depypere H, Inki P. The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial protection during estrogen replacement therapy: a clinical review. Climacteric. 2015;18:470-482.

- Minalt N, Caldwell A, Yedlicka GM, et al. Association of intrauterine device use and endometrial, cervical, and ovarian cancer: an expert review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023:S0002-9378(23)00224-7.

- Balayla J, Gil Y, Lasry A, et al. Ever-use of the intra-uterine device and the risk of ovarian cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;41:848-853. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2020.1789960.

- Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and long-term all-cause and cause-specific mortality: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2017;318:927-938. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.11217.

- Chen WY, Manson JE, Hankinson SE, et al. Unopposed estrogen therapy and the risk of invasive breast cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1027-1032. doi: 10.1001 /archinte.166.9.1027.

- Pinkerton JV, Wilson CS, Kaunitz AM. Reassuring data regarding the use of hormone therapy at menopause and risk of breast cancer. Menopause. 2022;29:1001-1004.doi:10.1097 /GME.0000000000002057.

- Romano SS, Doll KM. The impact of fibroids and histologic subtype on the performance of US clinical guidelines for the diagnosis of endometrial cancer among Black women. Ethn Dis. 2020;30:543-552. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.4.543.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318262e320.

- Backman T, Rauramo I, Jaakkola Kimmo, et al. Use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:813-817.

- Conz L, Mota BS, Bahamondes L, et al. Levonorgestrelreleasing intrauterine system and breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:970-982.

- Al Kiyumi MH, Al Battashi K, Al-Riyami HA. Levonorgestrelreleasing intrauterine system and breast cancer. Is there an association? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1749.

- Marsden J. Hormonal contraception and breast cancer, what more do we need to know? Post Reprod Health. 2017;23:116127. doi: 10.1177/2053369117715370.

- Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2019;364:k4810 doi:10.1136/bmj.k4810.

- Levitt L, Cox C, Dawson L. Q&A: implications of the ruling on the ACA’s preventive services requirement. KFF.org. https://www .kff.org/policy-watch/qa-implications-of-the-ruling-on -the-acas-preventive-services-requirement/#:~:text=On%20 March%2030%2C%202023%2C%20a,cost%2Dsharing%20 for%20their%20enrollees. Accessed May 2, 2023.

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are now used by more than 15% of US contraceptors. The majority of these IUDs release the progestin levonorgestrel, and with now longer extended use of the IUDs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA),1-3 they become even more attractive for use for contraception,control of menorrhagia or heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) during reproductive years and perimenopause, and potentially, although not FDA approved for this purpose, postmenopause for endometrial protection in estrogen users. In this roundtable discussion, we will look at some of the benefits of the IUD for contraception effectiveness and control of bleeding, as well as the potential risks if used for postmenopausal women.

Progestin IUDs and contraception

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD, NCMP: Dr. Kaunitz, what are the contraceptive benefits of progestin IUDs during perimenopause?

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, NCMP: We know fertility declines as women approach menopause. However, when pregnancy occurs in older reproductive-age women, the pregnancies are often unintended, as reflected by high rates of induced abortion in this population. In addition, the prevalence of maternal comorbidities (during pregnancy and delivery) is higher in older reproductive-age women, with the maternal mortality rate more than 5 times higher compared with that of younger women.4 Two recently published clinical trials assessed the extended use of full-size IUDs containing 52 mg of levonor-gestrel (LNG), with the brand names Mirena and Liletta.1,2 The data from these trials confirmed that both IUDs remain highly effective for up to 8 years of use, and currently, both devices are approved for up to 8 years of use. One caveat is that, in the unusual occurrence of a pregnancy being diagnosed in a woman using an IUD, we as clinicians, must be alert to the high prevalence of ectopic pregnancies in this setting.

Progestin IUDs and HMB

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Goldstein, can you comment on how well progestin IUDs work for HMB?

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, NCMP, CCD: Many women who need contraception will use these devices for suppressing HMB, and they can be quite effective, if the diagnosis truly is HMB, at reducing bleeding.5 But that efficacy in bleeding reduction may not be quite as long as the efficacy in pregnancy prevention.6 In my experience, among women using IUDs specifically for their HMB, good bleeding control may require changing the IUD at 3 to 5 years.

Barbara S. Levy, MD: When inserting a LNG-IUD for menorrhagia in the perimenopausal time frame, sometimes I will do a progestin withdrawal first, which will thin the endometrium and induce withdrawal bleeding because, in my experience, if you place an IUD in someone with perimenopausal bleeding, you may end up with a lot of breakthrough bleeding.

Perimenopause and hot flashes

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Kaunitz, we have learned that hot flashes often occur and become bothersome to women during perimenopause. Many women have IUDs placed during perimenopause for bleeding. Can you comment about IUD use during perimenopause and postmenopause?

Dr. Kaunitz: In older reproductive-age women who already have a progestin-releasing IUD placed, as they get closer to menopause when vasomotor symptoms (VMS) might occur, if these symptoms are bothersome, the presence or placement of a progestin-releasing IUD can facilitate treatment of perimenopausal VMS with estrogen therapy.

Progestin IUDs cause profound endometrial suppression, reduce bleeding and often, over time, cause users to become amenorrheic.7

The Mirena package insert states, “Amenorrhea develops in about 20% of users by one year.”2 By year 3 and continuing through year 8, the prevalence of amenorrhea with the 52-mg LNG-IUD is 35% to 40%.8 From a study by Nanette Santoro, MD, and colleagues, we know that, in perimenopausal women with a progestin-releasing IUD in place, who are experiencing bothersome VMS, adding transdermal estrogen is very effective in treating and suppressing those hot flashes. In her small clinical trial, among participants with perimenopausal bothersome VMS with an IUD in place, half were randomized to use of transdermal estradiol and then compared with women who did not get the estradiol patch. There was excellent relief of perimenopausal hot flashes with the combination of the progestin IUD for endometrial suppression and transdermal estrogen to relieve hot flashes.9

Dr. Pinkerton: Which women would not be good candidates for the use of this combination?

Dr. Kaunitz: We know that, as women age, the prevalence of conditions that are contraindications to combination contraceptives (estrogen-progestin pills, patches, or rings) starts to increase. Specifically, we see more: hypertension, diabetes, and high body mass index (BMI), or obesity. We also know that migraine headaches in women older than age 35 years is another condition in which ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) would not recommend use of combination contraceptives.10,11 These older perimenopausal women may be excellent candidates for a progestin-only releasing IUD combined with use of transdermal menopausal doses of estradiol if needed for VMS.

Dr. Goldstein: I do want to add that, in those patients who don’t have these comorbidities, combination estrogen-progestin contraceptives do a very nice job of ovarian suppression and will prevent the erratic production of estradiol, which, in my experience, often results in not only irregular bleeding but also possible exacerbation of perimenopausal mood symptoms.

Dr. Kaunitz: I agree, Steve. The ideal older reproductive-age candidate for combination pills, patch, or ring would be a slender, healthy, nonsmoking woman with normal blood pressure. Such women would be a fairly small subgroup of my practice, but they can safely continue combination contraceptives right through menopause. Consistent with CDC and ACOG guidance, rather than checking gonadotropins to “determine when menopause has occurred,” (which is, in fact, not an evidence-based approach to diagnosing menopause in this setting), such women can continue the combination contraceptive right up until age 55—the likelihood that women are still going to be ovulating or at risk for pregnancy becomes vanishingly small at that age.11,12 Women in their mid-50s can either seamlessly transition to use of systemic estrogen-progestin menopausal therapy or go off hormones completely.

Continue to: The IUD and HMB...

The IUD and HMB

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Goldstein, there’s been some good literature on the best management options for women with HMB. What is the most current evidence?

Dr. Goldstein: I think that the retiring of the terms menorrhagia and metrorrhagia may have been premature because HMB implies cyclical bleeding, and this population of women with HMB will typically do quite well. Women who have what we used to call metrorrhagia or irregular bleeding, by definition, need endometrial evaluation to be sure they don’t have some sort of organic pathology. It would be a mistake for clinicians to use an LNG-IUD in patients with abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) that has not been appropriately evaluated.

If we understand that we are discussing HMB, a Cochrane Review from 202213 suggests that an LNG intrauterine system is the best first-line treatment for reducing menstrual blood loss in perimenopausal women with HMB. Antifibrinolytics appeared second best, while long-cycle progestogens came in third place. Evidence on perception of improvement in satisfaction was ranked as low certainty. That same review found that hysterectomy was the best treatment for reducing bleeding, obviously, followed by resectoscopic endometrial ablation or a nonresectoscopic global endometrial ablation.

The evidence rating was low certainty regarding the likelihood that placing an LNG-IUD in women with HMB will result in amenorrhea, and I think that’s a very important point. The expectation of patients should be reduced or a significantly reduced amount of their HMB, not necessarily amenorrhea. Certainly, minimally invasive hysterectomy will result in total amenorrhea and may have a larger increase in satisfaction, but it has its own set of other kinds of possible complications.

Dr. Kaunitz: In an industry-funded, international multicenter trial,14 women with documented HMB (hemoglobin was eluted from soiled sanitary products), with menstrual blood loss of 80 mL or more per cycle, were randomized to placement of an LNG 52-mg IUD (Mirena) or cyclical medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA)—oral progestin use.

Although menstrual blood loss declined in both groups, it declined dramatically more in women with an IUD placed, and specifically with the IUD, menstrual blood loss declined by 129 mL on average, whereas the decline in menstrual blood loss with cyclical MPA was 18 mL. This data, along with earlier European data,15 which showed similar findings in women with HMB led to the approval of the Mirena progestin IUD for a second indication to treat HMB in 2009.

I also want to point out that, in the May 2023 issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Creinin and colleagues published a similar trial in women with HMB showing, once again, that progestin IUDs (52-mg LNG-IUD, Liletta) are extremely effective in reducing HMB.16 There is crystal clear evidence from randomized trials that both 52-mg LNG-IUDs, Mirena and Liletta, are very effective in reducing HMB and, in fact, are contributing to many women who in the past would have proceeded with surgery, such as ablation or hysterectomy, to control their HMB.

Oral contraception

Dr. Pinkerton: What about using low-dose continuous oral contraceptives noncyclically for women with HMB?

Dr. Goldstein: I do that all the time. It is interesting that Dr. Kaunitz mentions his patient population. It’s why we understand that one size does not fit all. You need to see patients one at a time, and if they are good candidates for a combined estrogen-progestin contraception, whether it’s pills, patches, or rings, giving that continuously does a very nice job in reducing HMB and straightening out some of the other symptoms that these perimenopausal women will have.

IUD risks

Dr. Pinkerton: We all know about use of low-dose oral contraceptives for management of AUB, and we use them, although we worry a little bit about breast cancer risk. Dr. Levy, please comment on the risks with IUDs of expulsions and perforations. What are the downsides of IUDs?

Dr. Levy: Beyond the cost, although it is a minimally invasive procedure, IUD insertion can be an invasive procedure for a patient to undergo; expulsions can occur.17 We know that a substantial percentage of perimenopausal women will have fibroids. Although many fibroids are not located in the uterine cavity, the expulsion rate with HMB for an LNG-IUD can be higher,13,16,18,19 perhaps because of local prostaglandin release with an increase in uterine contractility. There is a low incidence of perforations, but they do happen, particularly among women with scars in the uterus or who have a severely anteflexed or retroflexed uterus, and women with cervical stenosis, for example, if they have had a LEEP procedure, etc. Even though progestin IUDs are outstanding tools in our toolbox, they are invasive to some extent, and they do have the possibility of complications.

Dr. Kaunitz: As Dr. Levy points out, although placement of an IUD may be considered an invasive procedure, it is also an office-based procedure, so women can drive home or drive back to work afterwards without the disruption in their life and the potential complications associated with surgery and anesthesia.

Continue to: Concerns with malpositioning...

Concerns with malpositioning

Dr. Pinkerton: After placement of an IUD, during a follow-up visit, sometimes you can’t visualize the string. The ultrasonography report may reveal, “IUD appears to be in the right place within the endometrium.” Dr. Goldstein, can you comment on how we should use ultrasound when we can’t visualize or find the IUD string, or if the patient complains of abdominal pain, lower abdominal discomfort, or irregular bleeding or spotting and we become concerned about IUD malposition?

Dr. Goldstein: Ultrasound is not really required after an uncomplicated placement of an IUD or during routine management of women who have no problems who are using an IUD. In patients who present with pain or some abnormal bleeding, however, sometimes it is the IUD being malpositioned. A very interesting study by the late great Beryl Benacerraf20 showed that there was a statistically significant higher incidence of the IUD being poorly positioned when patients have pain or bleeding (FIGURE 1). It was not always apparent on 2D ultrasonography. Using a standard transvaginal ultrasound of the long access plane, the IUD may appear to be very centrally located. However, if you do a 3D coronal section, not infrequently in these patients with any pain or bleeding, one of the arms has pierced the myometrium (FIGURE 2). This can actually be a source of pain and bleeding.

It’s also very interesting when you talk about perforation. I became aware of a big to-do in the medical/legal world about the possibility of the IUD migrating through the uterine cavity.21 This just does not exist, as was already pointed out. If the IUD is really going to go anywhere, if it’s properly placed, it’s going to be expelled through an open cervix. I do believe that, if you have pierced the myometrium through uterine contractility over time, some of these IUDs could work their way through the myometrium and somehow come out of the uterus either totally or partially. I think ultrasound is invaluable in patients with pain and bleeding, but I think you need to have an ultrasound lab capable of doing a 3D coronal section.

Progestin IUDs for HT replacement: Benefits/risks

Dr. Pinkerton: Many clinicians are excited that they can use essentially estrogen alone for women who have a progestin IUD in place. What about the possible off-label use of the progestin IUD to replace oral progestogen for hormone therapy (HT)? Dr. Kaunitz, are there any studies using this for postmenopausal HT (with a reminder that the IUD is not FDA approved for this purpose)?

Dr. Kaunitz: We have data from Europe indicating that, in menopausal women using systemic estrogen, the full-size LNG 52 IUD—Mirena or Liletta—provides excellent endometrial suppression.22 Where we don’t have data is with the smaller IUDs, which would be Kyleena and Skyla, which release smaller amounts of progestin each day into the endometrial cavity.

I have a number of patients, most of them women who started use of a progestin IUD as older reproductive-age women and then started systemic estrogen for treatment of perimenopausal hot flashes and then continued the use of their IUD plus systemic estrogen in treating postmenopausal hot flashes. The IUD is very useful in this setting, but as you pointed out, Dr. Pinkerton, this does represent off-label use.

Dr. Pinkerton: I know this use does not affect plasma lipids or cardiovascular risk markers, although users seem to report that the IUD has improved their quality of life. The question comes up, what are the benefits on cancer risk for using an IUD?

Dr. Levy: It’s such a great question because, as we talk about the balance of risks and benefits for anything that we are offering to our patients, it is really important to focus on some of the benefits. For both the copper and the LNG-IUD, there is a reduction in endometrial cancer,22 as well as pretty good data with the copper IUD about a reduction in cervical cancer.23 Those data are a little bit less clear for the LNG-IUD.

Interestingly, at least one meta-analysis published in 2020 shows about a 30% reduction in ovarian cancer risk with the LNG-IUD.24 We need to focus our patients on these other benefits. They tend to focus on the risks, and, of course, the media blows up the risks, but the benefits are quite substantial beyond just reducing HMB and providing contraception.

Dr. Pinkerton: As Dr. Kaunitz said, when you use this IUD, with its primarily local uterine progestin effects, it’s more like using estrogen alone without as much systemic progestin. Recently I wrote an editorial on the benefits of estrogen alone on the risk of breast cancer, primarily based on the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) observational long-term 18-year cumulative follow-up. When estrogen alone was prescribed to women after a hysterectomy, estrogen therapy used at menopause did not increase the risk of invasive breast cancer, and was associated with decreased mortality.25 However, the nurse’s health study has suggested that longer-term use may be increased with estrogen alone.26 For women in the WHI with an intact uterus who used estrogen, oral MPA slightly increased the risk for breast cancer, and this elevated risk persisted even after discontinuation. This leads us to the question, what are the risks of breast cancer with progestin IUD use?

I recently reviewed the literature, and the answer is, it’s mixed. The FDA has put language into the package label that acknowledges a potential breast cancer risk for women who use a progestin IUD,27 and that warning states, “Women who currently have or have had breast cancer or suspect breast cancer should not use hormonal contraception because some breast cancers are hormone sensitive.” The label goes on to say, “Observational studies of the risk of breast cancer with the use of a levonorgestrel-releasing IUS don’t provide conclusive evidence of increased risk.” Thus, there is no conclusive answer as to whether there is a possible link of progestin IUDs to breast cancer.

What I tell my patients is that research is inconclusive. However, it’s unlikely for a 52-mg LNG-IUD to significantly increase a woman’s breast cancer risk, except possibly in those already at high risk from other risk factors. I tell them that breast cancer is listed in the package insert as a potential risk. I could not find any data on whether adding a low-dose estradiol patch would further increase that risk. So I counsel women about potential risk, but tell them that I don’t have any strong evidence of risk.

Continue to: Dr. Goldstein...

Dr. Goldstein: If you look in the package insert for Mirena,2 similar to Liletta, certainly the serum levels of LNG are lower than that for combination oral contraceptives. For the IUD progestins, they are not localized only to the uterus, and LNG levels range from about 150 to 200 µg/mL up to 60 months. It’s greater at 12 months, at about 180 µg/mL,at 24 months it was 192 µg/mL, and by 60 months it was 159 µg/mL. It’s important to realize that there is some systemic absorption of progestin with progestin IUDs, and it is not completely a local effect.

JoAnn, you mentioned the WHI data,25 and just to specify, it was not the estrogen-only arm, it was the conjugated equine estrogen-only arm of the WHI. I don’t think that estradiol alone increases breast cancer risk (although there are no good prospective, follow-through, 18-year study data, like the WHI), but I think readers need to understand the difference in the estrogen type.

Endometrial evaluation. My question for the panel is as follows. I agree that the use of the progestin-releasing IUD is very nice for that transition to menopause. I do believe it provides endometrial protection, but we know from other studies that, when we give continuous combined HT, about 21% to 26% of patients will experience some bleeding/staining, responding in the first 4-week cycles, and it can be as high as 9% at 1 year. If I have a patient who bleeds on continuous combined HT, I will evaluate her endometrium, usually just with a simple transvaginal ultrasound. If an IUD is in place, and the patient now begins to have some irregular bleeding, how do you evaluate her with the IUD in place?

Dr. Levy: That is a huge challenge. We know from a recent paper,28 that the endometrial thickness, while an excellent measure for Caucasian and European women, may be a poor marker for endometrial pathology in African-American women. What we thought we knew, which was, if the stripe is 4 mL or less, we can forget about it, I think in our more recent research that is not so true. So you bring up a great point, what do you do? The most reliable evaluation will be with an office hysteroscopy, where you can really look at the entire cavity and for tiny, little polyps and other things. But then we are off label because the use of hysteroscopy with an IUD in place is off label. So we are really in a conundrum.

Dr. Pinkerton: Also, if you do an endometrial biopsy, you might dislodge the IUD. If you think that you are going to take the IUD out, it may not matter if you dislodge it. I will often obtain a transvaginal ultrasound to help me figure out the next step, and maybe look at the dosing of the estrogen and progestin—but you can’t monitor an IUD with blood levels. You are in a vacuum of trying to figure out the best thing to do.

Dr. Kaunitz: One of the hats I wear here in Jacksonville is Director of GYN Ultrasound. I have a fair amount of experience doing endometrial biopsies in women with progestin IUDs in place under abdominal ultrasound guidance and keeping a close eye on the position of the IUD. In the first dozen or so such procedures I did, I was quite concerned about dislodging the IUD. It hasn’t happened yet, and it gives me some reassurance to be able to image the IUD and your endometrial suction curette inside the cavity as you are obtaining endometrial sampling. I have substantial experience now doing that, and so far, no problems. I do counsel all such women in advance that there is some chance I could dislodge their IUD.

Dr. Goldstein: In addition to dislodging the IUD, are you not concerned that, if the pathology is not global, that a blind endometrial sampling may be fraught with some error?

Dr. Kaunitz: The endometrium in women with a progestin-releasing IUD in place tends to be very well suppressed. Although one might occasionally find, for instance, a polyp in that setting, I have not run into, and I don’t expect to encounter going forward, endometrial hyperplasia or cancer in women with current use of a progestin IUD. It’s possible but unlikely.

Dr. Levy: The progestin IUD will counterbalance a type-1 endometrial cancer—an endometrial cancer related to hyperstimulation by estrogen. It will not do anything, to my knowledge, to counterbalance a type 2. I think the art of medicine is, you do the best you can with the first episode of bleeding, and if she persists in her bleeding, we have to persevere and continue to evaluate her.

Dr. Goldstein: I agree 100%.

Dr. Pinkerton: We all agree with you. That’s a really good point.

Continue to: Case examinations...

Case examinations

CASE 1 Woman with intramural fibroids

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Goldstein, you have a 48-year-old Black woman who has heavy but regular menstrual bleeding with multiple fibroids (the largest is about 4 to 5 cm, they look intramural, with some distortion of the cavity but not a submucous myoma, and the endometrial depth is 9 cm). Would you insert an IUD, and would you recommend an endometrial biopsy first?

Dr. Goldstein: I am not a huge fan of blind endometrial sampling, and I do think that we use the “biopsy” somewhat inappropriately since sampling is not a directed biopsy. This became obvious in the landmark paper by Guido et al in 1995 and was adopted by ACOG only in 2012.29 Cancers that occupy less than 50% of the endometrial surface area are often missed with such blind sampling. Thus I would not perform an endometrial biopsy first, but would rather rely on properly timed and performed transvaginal ultrasound to rule out any concurrent endometrial disease. I think a lot of patients who have HMB, not only because of their fibroids but also often just due to the surface area of their uterine cavity being increased—so essentially there is more blood volume when they bleed. However, you said that in this case the patient has regular menstrual bleeding, so I am assuming that she is still ovulatory. She may have some adenomyosis. She may have a large uterine cavity. I think she is an excellent candidate for an LNG-releasing IUD to reduce menstrual blood flow significantly. It will not necessarily give her amenorrhea, and it may give her some irregular bleeding. Then at some distant point, say in 5 or 6 months if she does have some irregular staining or bleeding, I would feel much better about the fact that nothing has developed as long as I knew that the endometrium was devoid of pathology when I started.

CASE 2 Woman with family history of breast cancer

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Levy, a 44-year-old woman has a family history of breast cancer in her mother at age 72, but she still needs contraceptionbecause of that unintended pregnancy risk in the 40s, and she wants something that is not going to increase her risk of breast cancer. What would you use, and how would you counsel her if you decided to use a progestin IUD?

Dr. Levy: The data are mixed,30-33 but whatever the risk, it is miniscule, and I would bring up the CDC Medical Eligibility Criteria.11 For a patient with a family history of breast cancer, for use of the progestin IUD, it is a 1—no contraindications. What I tend to tell my patients is, if you are worried about breast cancer, watch how much alcohol you are drinking and maintain regular exercise. There are so many preventive things that we can do to reduce risk of breast cancer when she needs contraception. If there is any increase in risk, it is so miniscule that I would very strongly recommend a progestin IUD for her.

Dr. Pinkerton: In addition, in recognizing the different densities of breast, dense breast density could lead to supplemental screening, which also could give her some reassurance that we are adequately screening for breast cancer.

CASE 3 Woman with IUD and VMS

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Kaunitz, you have a 52-year-old overweight female. She has been using a progestin IUD for 4 years, is amenorrheic, but now she is having moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms despite the IUD in place. You have talked to her about risks and benefits of HT, and she is interested in starting it. I know we talked about the studies, but I want to know what you are going to tell her. How do you counsel her about off-label use?

Dr. Kaunitz: The most important issue related to treating vasomotor symptoms in this patient is the route of systemic estrogen. Understandably, women’s biggest concern regarding the risks of systemic estrogen-progestin therapy is breast cancer. However, statistically, by far the biggest risk associated with oral estrogen-progestogen therapy, is elevated risk of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. We have seen this, with a number of studies, and the WHI made it crystal clear with risks of oral conjugated equine estrogen at the dose of 0.625 mg daily. Oral estradiol 1 mg daily is also associated with a similar elevated risk of venous thrombosis. We also know that age and BMI are both independent risk factors for thrombosis. So, for a woman in her 50s who has a BMI > 30 mg/kg2, I don’t want to further elevate her risk of thrombosis by giving her oral estrogen, whether it is estradiol or conjugated equine estrogen. This is a patient in whom I would be comfortable using transdermal (patch) estradiol, perhaps starting with a standard dose of 0.05 mg weekly or twice weekly patch, keeping in mind that 0.05 mg in the setting of transdermal estrogen refer to the daily or to the 24-hour release rate. The 1.0 mg of oral estradiol and 0.625 mg of conjugated equine estrogen refers to the mg quantity of estrogen in each tablet. This is a source of great confusion for clinicians.

If, during follow-up, the 0.05 mg estradiol patch is not sufficient to substantially reduce symptoms, we could go up, for instance, to a 0.075 mg estradiol patch. We know very clearly from a variety of observational studies, including a very large UK study,34 that in contrast with oral estrogen, transdermal estradiol is safer from the perspective of thrombosis.

Insurance coverage for IUDs

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Levy: Can you discuss IUDs and the Affordable Care Act’s requirement to cover contraceptive services?

Dr. Levy: Unfortunately, we do not know whether this benefit will continue based on a very recent finding from a judge in Texas that ruled the preventive benefits of the ACA were illegal.35 We don’t know what will happen going forward. What I will say is that, unfortunately, many insurance companies have not preserved the meaning of “cover all things,” so what we are finding is that, for example, they only have to cover one type in a class. The FDA defined 18 classes of contraceptives, and a hormonal IUD is one class, so they can decide that they are only going to cover one of the four IUDS. And then women don’t have access to the other three, some of which might be more appropriate for them than another.

The other thing very relevant to this conversation is that, if you use an ICD-10 code for menorrhagia, for HMB, it no longer lives within that ACA preventive care requirement of coverage for contraceptives, and now she is going to owe a big deductible or a copay. If you are practicing in an institution that does not allow the use of IUDs for contraception, like a Catholic institution where I used to practice, you will want to use that ICD-10 code for HMB. But if you want it offered with no out-of-pocket cost for the patient, you need to use the preventive medicine codes and the contraception code. These little nuances for us can make a huge difference for our patients.

Dr. Pinkerton: Thank you for that reminder. I want to thank our panelists, Dr. Levy, Dr. Goldstein, and Dr. Kaunitz, for providing us with such a great mix of evidence and expert opinion and also giving a benefit of their vast experience as award-winning gynecologists. Hopefully, today you have learned the benefits of the progestin IUD not only for contraception in reproductive years and perimenopause but also for treatment of HMB, and the potential benefit due to the more prolonged effectiveness of the IUDs for endometrial protection in postmenopause. This allows less progestin risk, essentially estrogen alone for postmenopausal HT. Unsolved questions remain about whether there is a risk of breast cancer with their use, but there is a clear benefit of protecting against pregnancy and endometrial cancer. ●

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are now used by more than 15% of US contraceptors. The majority of these IUDs release the progestin levonorgestrel, and with now longer extended use of the IUDs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA),1-3 they become even more attractive for use for contraception,control of menorrhagia or heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) during reproductive years and perimenopause, and potentially, although not FDA approved for this purpose, postmenopause for endometrial protection in estrogen users. In this roundtable discussion, we will look at some of the benefits of the IUD for contraception effectiveness and control of bleeding, as well as the potential risks if used for postmenopausal women.

Progestin IUDs and contraception

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD, NCMP: Dr. Kaunitz, what are the contraceptive benefits of progestin IUDs during perimenopause?

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, NCMP: We know fertility declines as women approach menopause. However, when pregnancy occurs in older reproductive-age women, the pregnancies are often unintended, as reflected by high rates of induced abortion in this population. In addition, the prevalence of maternal comorbidities (during pregnancy and delivery) is higher in older reproductive-age women, with the maternal mortality rate more than 5 times higher compared with that of younger women.4 Two recently published clinical trials assessed the extended use of full-size IUDs containing 52 mg of levonor-gestrel (LNG), with the brand names Mirena and Liletta.1,2 The data from these trials confirmed that both IUDs remain highly effective for up to 8 years of use, and currently, both devices are approved for up to 8 years of use. One caveat is that, in the unusual occurrence of a pregnancy being diagnosed in a woman using an IUD, we as clinicians, must be alert to the high prevalence of ectopic pregnancies in this setting.

Progestin IUDs and HMB

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Goldstein, can you comment on how well progestin IUDs work for HMB?

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, NCMP, CCD: Many women who need contraception will use these devices for suppressing HMB, and they can be quite effective, if the diagnosis truly is HMB, at reducing bleeding.5 But that efficacy in bleeding reduction may not be quite as long as the efficacy in pregnancy prevention.6 In my experience, among women using IUDs specifically for their HMB, good bleeding control may require changing the IUD at 3 to 5 years.

Barbara S. Levy, MD: When inserting a LNG-IUD for menorrhagia in the perimenopausal time frame, sometimes I will do a progestin withdrawal first, which will thin the endometrium and induce withdrawal bleeding because, in my experience, if you place an IUD in someone with perimenopausal bleeding, you may end up with a lot of breakthrough bleeding.

Perimenopause and hot flashes

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Kaunitz, we have learned that hot flashes often occur and become bothersome to women during perimenopause. Many women have IUDs placed during perimenopause for bleeding. Can you comment about IUD use during perimenopause and postmenopause?

Dr. Kaunitz: In older reproductive-age women who already have a progestin-releasing IUD placed, as they get closer to menopause when vasomotor symptoms (VMS) might occur, if these symptoms are bothersome, the presence or placement of a progestin-releasing IUD can facilitate treatment of perimenopausal VMS with estrogen therapy.

Progestin IUDs cause profound endometrial suppression, reduce bleeding and often, over time, cause users to become amenorrheic.7

The Mirena package insert states, “Amenorrhea develops in about 20% of users by one year.”2 By year 3 and continuing through year 8, the prevalence of amenorrhea with the 52-mg LNG-IUD is 35% to 40%.8 From a study by Nanette Santoro, MD, and colleagues, we know that, in perimenopausal women with a progestin-releasing IUD in place, who are experiencing bothersome VMS, adding transdermal estrogen is very effective in treating and suppressing those hot flashes. In her small clinical trial, among participants with perimenopausal bothersome VMS with an IUD in place, half were randomized to use of transdermal estradiol and then compared with women who did not get the estradiol patch. There was excellent relief of perimenopausal hot flashes with the combination of the progestin IUD for endometrial suppression and transdermal estrogen to relieve hot flashes.9

Dr. Pinkerton: Which women would not be good candidates for the use of this combination?

Dr. Kaunitz: We know that, as women age, the prevalence of conditions that are contraindications to combination contraceptives (estrogen-progestin pills, patches, or rings) starts to increase. Specifically, we see more: hypertension, diabetes, and high body mass index (BMI), or obesity. We also know that migraine headaches in women older than age 35 years is another condition in which ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) would not recommend use of combination contraceptives.10,11 These older perimenopausal women may be excellent candidates for a progestin-only releasing IUD combined with use of transdermal menopausal doses of estradiol if needed for VMS.

Dr. Goldstein: I do want to add that, in those patients who don’t have these comorbidities, combination estrogen-progestin contraceptives do a very nice job of ovarian suppression and will prevent the erratic production of estradiol, which, in my experience, often results in not only irregular bleeding but also possible exacerbation of perimenopausal mood symptoms.

Dr. Kaunitz: I agree, Steve. The ideal older reproductive-age candidate for combination pills, patch, or ring would be a slender, healthy, nonsmoking woman with normal blood pressure. Such women would be a fairly small subgroup of my practice, but they can safely continue combination contraceptives right through menopause. Consistent with CDC and ACOG guidance, rather than checking gonadotropins to “determine when menopause has occurred,” (which is, in fact, not an evidence-based approach to diagnosing menopause in this setting), such women can continue the combination contraceptive right up until age 55—the likelihood that women are still going to be ovulating or at risk for pregnancy becomes vanishingly small at that age.11,12 Women in their mid-50s can either seamlessly transition to use of systemic estrogen-progestin menopausal therapy or go off hormones completely.

Continue to: The IUD and HMB...

The IUD and HMB

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Goldstein, there’s been some good literature on the best management options for women with HMB. What is the most current evidence?

Dr. Goldstein: I think that the retiring of the terms menorrhagia and metrorrhagia may have been premature because HMB implies cyclical bleeding, and this population of women with HMB will typically do quite well. Women who have what we used to call metrorrhagia or irregular bleeding, by definition, need endometrial evaluation to be sure they don’t have some sort of organic pathology. It would be a mistake for clinicians to use an LNG-IUD in patients with abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) that has not been appropriately evaluated.

If we understand that we are discussing HMB, a Cochrane Review from 202213 suggests that an LNG intrauterine system is the best first-line treatment for reducing menstrual blood loss in perimenopausal women with HMB. Antifibrinolytics appeared second best, while long-cycle progestogens came in third place. Evidence on perception of improvement in satisfaction was ranked as low certainty. That same review found that hysterectomy was the best treatment for reducing bleeding, obviously, followed by resectoscopic endometrial ablation or a nonresectoscopic global endometrial ablation.

The evidence rating was low certainty regarding the likelihood that placing an LNG-IUD in women with HMB will result in amenorrhea, and I think that’s a very important point. The expectation of patients should be reduced or a significantly reduced amount of their HMB, not necessarily amenorrhea. Certainly, minimally invasive hysterectomy will result in total amenorrhea and may have a larger increase in satisfaction, but it has its own set of other kinds of possible complications.

Dr. Kaunitz: In an industry-funded, international multicenter trial,14 women with documented HMB (hemoglobin was eluted from soiled sanitary products), with menstrual blood loss of 80 mL or more per cycle, were randomized to placement of an LNG 52-mg IUD (Mirena) or cyclical medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA)—oral progestin use.

Although menstrual blood loss declined in both groups, it declined dramatically more in women with an IUD placed, and specifically with the IUD, menstrual blood loss declined by 129 mL on average, whereas the decline in menstrual blood loss with cyclical MPA was 18 mL. This data, along with earlier European data,15 which showed similar findings in women with HMB led to the approval of the Mirena progestin IUD for a second indication to treat HMB in 2009.

I also want to point out that, in the May 2023 issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Creinin and colleagues published a similar trial in women with HMB showing, once again, that progestin IUDs (52-mg LNG-IUD, Liletta) are extremely effective in reducing HMB.16 There is crystal clear evidence from randomized trials that both 52-mg LNG-IUDs, Mirena and Liletta, are very effective in reducing HMB and, in fact, are contributing to many women who in the past would have proceeded with surgery, such as ablation or hysterectomy, to control their HMB.

Oral contraception

Dr. Pinkerton: What about using low-dose continuous oral contraceptives noncyclically for women with HMB?

Dr. Goldstein: I do that all the time. It is interesting that Dr. Kaunitz mentions his patient population. It’s why we understand that one size does not fit all. You need to see patients one at a time, and if they are good candidates for a combined estrogen-progestin contraception, whether it’s pills, patches, or rings, giving that continuously does a very nice job in reducing HMB and straightening out some of the other symptoms that these perimenopausal women will have.

IUD risks